Susana looks out into the blackness from a small stage in a tiny pub called the Hat and Hare. This is it, our big night, June 7, 2010, the culmination of our yearlong effort to learn to perform magic tricks. We are here at the Magic Castle, a funky mansion with many pubs nestled in the Hollywood Hills, to try to win entry into the prestigious Academy of Magical Arts as performing magicians—only we are billing ourselves as the world’s first neuromagicians. Can we bring it off? Can we convince the panel of nine professional magicians sitting in the dark before us—including Shoot Ogawa, the most famous Asian magician in the world, and Goldfinger, aka Jack Vaughn, the Society of American Magicians Hall of Famer and perhaps the most prominent African American magician in history—that we deserve to be members of their inner circle?*

Cross Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry with an English pub and Disney’s Haunted Mansion and you’ll get the Magic Castle. The building is the Area 51 of magic and bills itself as the most exclusive club of magicians in the world. This is the sanctuary where many of the world’s greatest magicians let down their goatees, hang out, and relax. Once a month, they invite a few wannabe magicians to audition. We are trying out in a group of six people, which is larger than usual. You can’t get an audition without a current member sponsoring you, and even then only about half the candidates pass on the first go. Many more are encouraged to try out again after another one to three months of practice. The Castle sometimes provides a mentor to give weekly lessons until the candidate is up to snuff. Those who pass muster are eligible for a Gold Pin membership, which provides access to the extensive library of magical arts, lectures, and shows, plus the right to vote on academy matters.

Over the past year we had been practicing an act that we developed with the help of Magic Tony, our close friend and tutor. In recent months, as our date with destiny approached, we met in Starbucks, IHOP and other breakfast joints, wine bars, and even a large empty classroom in the psychology building at Arizona State University, where Tony is a graduate student. Tony taught us classic tricks—using cards, ropes, bits of paper, Jell-O, and gimmicks—and helped us dress them in modern garb. On stage, we wear white lab coats, with our name and the title “Neuromagician” stitched on the left breast pocket.

In our act, we demonstrate that we can make an exact replica of a person’s brain using a special Polaroid camera and a pan originally designed to hold live doves. We provide false explanations of how the technology works using rope tricks and magicians’ gimmicks. We read minds. And then, in the end, we perform surgery on the brain, which is made of Jell-O, to extract a playing card that a volunteer has been “holding in his mind” all through the act. Our patter is mostly nonsense delivered with an air of authority and, we hope, humor.

Susana clears her throat and begins, “Hello, ladies and gentlemen, and thank you for coming to tonight’s Wonder Show. As you may know, Wonder Shows were one of the ways preindustrial scientists and inventors disseminated their discoveries to the public. In the nineteenth century, photographs were prohibitively expensive, and literacy, for that matter, was not yet ubiquitous. So scientists went on the road to show the wonders of the age and the discoveries that were changing the world.”

WHAT WOMEN MAGICIANS?

![]()

Susana addressed the audience as “ladies and gentlemen” but there are very few women, at least in the United States and Europe, who make their living performing magic. We have asked many magicians why this is so. The answers we’ve received are more amusing than illuminating: Women can’t lie. Women don’t get tricks. Women can’t do math. Women can’t command respect. Girls don’t receive magic sets as birthday presents.

The lack of women in magic is self-perpetuating. Teller points out that fifty years ago there were hardly any women in comedy. Now nearly half of all comedians are women. So the larger issue at play may be the lack of cultural tradition and role models for aspiring women magicians. In Asia, for instance, female magicians are much more common. At the 2009 Magic Olympics in Beijing, Max Maven told us over tea that, historically, Asian women often performed religious rituals involving magic, and that geishas incorporated magic into their elaborate entertainment routines.

Taking his turn at center stage, Steve nonchalantly shuffles a deck of cards. “Wonder Shows are all but gone, now replaced with high-quality publications and TV documentaries,” he says. “Which is all well and good. But there is something missing on the page and on the screen that can only be fully experienced with live experiments on innocent vict—uh, that is, I mean … real people. Tonight, we will revive the Wonder Show form of scientific discourse. We will show you the wonders of our modern age, with a special emphasis on brain science.”

Steve takes a step forward and gazes into the audience. “Let’s get started by asking for a volunteer.”

Eight jurors point simultaneously to the only other person in the room: the ninth member of the committee, Scotto (otherwise known as Scott Smith, a professional magician with a day job as a quality assurance engineer at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business). He’s been our primary handler for the audition process, the one who scheduled our tryout and sent us the performance guidelines: No fire. Have fifteen minutes of performance ready. If you perform as a duo, make sure that each person does enough magic to be evaluated individually.

The key thing he hasn’t told us is what the judges are looking for. We assume they want to see skill with sleights of hand, patter, humor, originality, and timing. Only later do we learn the three main requirements that they are judging us on. We must be good enough never to embarrass the Magic Castle. We must not reveal magic secrets through poor performance. And our timing must indicate that we understand when the magic happens for the audience—that we aren’t just going through the motions.

MAGIC TRICK CATEGORIES

![]()

All magic tricks follow certain central themes:

• Appearance: You produce something from nothing—a rabbit from a hat, a coin from thin air, a dove from a pan.

• Vanishing: You make something disappear—the rabbit, the coin, the dove, the Statue of Liberty, whatever.

• Transposition: You cause something to move from one place to another—as when Tamariz transports cards from a table into the jacket pocket of somebody he’s never approached.

• Restoration: You destroy an object, then bring it back to its original state—as when a magician rips up your hundred-dollar bill and then hands it back to you intact.

• Transformation: An object changes form, such as when a coin turns into a different coin or three different lengths of rope are transformed into three equal lenghts.

• Telekinesis (levitation or animation of an object): You defy gravity by making something rise into the air—such as the classic woman with the hoop run around her. Another example is Teller making a red ball hover and follow him around onstage. Or you make a spoon bend with your thoughts alone.

• Extraordinary mental or physical feats or extrasensory abilities: You catch a bullet with your teeth or you can tell what a person will choose. Johnny Thompson’s precognition trick from chapter 7 is a good example.

Poor Scotto. He is apparently destined to suffer any abuse we may issue during our performance.

Steve approaches Scotto, saying in a soft, crooning, magician-style voice, “Am I correct that we’ve never met before tonight and that you are acting of your own free will as my assistant?”

Scotto replies that he’s only spoken to Steve through e-mail correspondence as part of the audition process and that Steve has never asked him to serve as a stooge for the act about to unfold.

“Thank you. Then I’ll ask you to first choose a card as I riffle through them with my thumb. You can tell me to stop anywhere you like.”

Steve cuts the cards and extends his right hand in front of Scotto, running his thumb down the corner of the deck. The click of each card is clearly audible in the minuscule bar. Even the red velvet curtains that cover the walls can’t absorb the loud snaps.

About halfway through the deck, Scotto says “Stop.” Steve removes the cards above the stopping point and allows Scotto to take the chosen card, which is now on top of the half-deck.

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

Of course it is a force. We are setting up a complex trick in which we will magically transport a card into the middle of a brain made out of Jell-O. But first we need Scotto to pick a card identical to the one we embedded last night into the fake Jell-O brain. It is the jack of diamonds.

To force the card onto Scotto, Steve loads the jack of diamonds as the top card of the deck, then shuffles the cards without actually moving the jack. When this false shuffle is complete, Steve cuts the cards into his left hand, which puts the jack of diamonds in the middle of the deck, but he sticks his left pinky just above it so that he knows exactly where the card is. From the front of the deck, the cards look flat, but from the back there is a clear gap caused by the “pinky break.” A master wouldn’t have had to actually stick his finger into the deck. The pinky would simply hold open a small gap. But despite months of practice, it’s clear to Steve (and probably everyone in the room) that he’s no master.

With the pinky break in place, Steve runs his left thumb down the front corner of deck (“the riffle”) and waits for Scotto to say “Stop.” But no matter where Scotto chooses to stop, Steve will lift the cards from the back of the deck at the pinky break, ensuring that Scotto’s “choice” is the jack of diamonds. Steve’s misdirection involves looking into Scotto’s eyes as he lifts the cards, so as to keep Scotto’s attention away from the sleight of hand.

Learning tricks like these, we’ve been surprised to discover, is just as much about what you do with your eyes and body as it is about what you do with your hands. The trickiest part for us has been to learn to do things without attending to them—or, more precisely, while attending to something else. Pulling off these simple sleights requires about as much dexterity as you need when learning how to shuffle a deck of cards for the first time. But to learn to pay attention to irrelevant things while specifically not attending to the secret methods—all the while not looking guilty? Very difficult.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

If we learned one thing during our magic training, it is that the route to success is practice, practice, practice, and more practice. This is true of every motor skill you acquire throughout your life—learning to walk, kick a soccer ball, play the piano, hit a tennis ball, block a punch in tae kwon do, ski down a black diamond slope, or put a pinky break in a deck of cards. But now we aren’t just directing a ball to a specific point at a specific time, we are also using our own spotlight of attention to misdirect.

Human motor skills are countless and often amazing. People born without arms can dress themselves and write letters—with their toes. Contact jugglers, such as David Bowie’s character in the movie Labyrinth, can manipulate glass balls with their hands and arms to create the illusion that the balls are floating in midair.* Acrobats can do handstands on top of galloping horses. But we acquire all our motor skills in the same way.

You have in your brain swaths of tissue, called the motor cortex, that map all the movements you are able to make. Your primary motor map sends commands from your brain down to your spine and out to all your various muscles. When this map is activated, your body can move. You have other motor maps involved in planning and imagining movements, but for now let’s look at how a familiar skill develops.

Let’s say you are learning to play the piano. When you are a novice, the region of your brain that maps your fingers—yes, you have finger maps—grows in an exuberance of new connections, seeking and strengthening any connection patterns that maximize your performance. If you give up practicing, your finger maps will stop adapting and shrink back to their original size. But if you keep practicing, you will reach a new phase of long-term structural change in your maps. Many of the novel neural connections you made early on aren’t needed anymore. A consolidation occurs: the skill becomes better integrated into your maps’ basic circuitry, and the whole process becomes more efficient and automatic.

There is another level to all this, and that’s true expertise, or virtuosity. If you practice a complex motor skill day in and day out for years on end, always striving for perfection, your motor maps again increase in size. Professional pianists (and magicians!) unquestionably possess enlarged hand and finger maps. Their maps are larger than average because they are crammed full of finely honed neural wiring that gives them exquisite (and hard-earned) control of timing, force, and targeting of all ten fingers. Violinists also have enlarged hand maps—but only one. The map that controls their string-fingering hand is like the pianists’. But their bow hands, while deft and coordinated, do not become beefed up beyond normal.

Here is one more interesting fact about expertise. As you gradually master a complex skill, the “motor programs” it requires gradually migrate down from higher to lower areas in your motor circuitry. Imagine a guy who signs up for samba dance classes. Like all novices, he is terrible at first. During his first several lessons, he is processing his dance-related movement combinations up in his higher motor regions, such as the supplementary motor area. This area is important for engaging in any complex and unfamiliar motor task. The dance moves are at first very complex for him. He needs to pay attention to them constantly, and even so he often loses track.

He sticks with it, though, and after a couple of months he is getting a lot smoother. He is using his supplementary motor area much less for his dancing these days. Many of the motor command sequences he is using now have been transferred downward in the cortical hierarchy, to reside mainly in his premotor cortex. He’s become a competent dancer. He’s not Fred Astaire, but he needs to pay less attention to the basics now. He makes far fewer mistakes. He can improvise longer and longer sequences.

Finally, if he practices often for many months stretching into years, eventually his premotor cortex delegates a lot of its dance-related sequences to the primary motor cortex. Now he can be called a great samba dancer. Dance has mingled intimately with the motor primitives in his fundamental motor map. The dance has become part of his being.*

Susana experienced the gradual acquisition of expertise when she practiced the martial art tae kwon do through high school and college. She has a brown belt and was once the junior tae kwon do champion of Galicia, the region of Spain where she was raised. She found that in the sparring ring, novice martial artists baldly telegraph their intentions through eye movements and body language. The same is typically true of new magicians, who need to think about their tricks as they perform them, and therefore perform them badly.

Accomplished magicians don’t need to pay attention to their moves during a trick because the movements come as second nature, as naturally as walking or talking, leaving them free to attend somewhere else. Juan Tamariz jokingly asserts that each spectator is a “telepath.” He says that if the magician thinks, even for a brief instant, “Here’s where I do the trick,” the audience will be able to tell. Thus magicians must be able to perform their routines by rote, without needing to engage any conscious processes. If this is accomplished, the audience won’t be able to isolate the critical instant or location of the secret method behind the trick. We all do this in real life to some extent. If you have something to hide from your business partner, spouse, or a law enforcement agent, you will do best not to think about it while in their presence, lest your voice, gaze, or posture give you away.

THE FRENCH DROP OR DECEPTIVE

BIOLOGICAL MOTION

![]()

Arturo de Ascanio, the father of Spanish card magic, once said that sleight of hand must be so good that attentional misdirection is not needed, and that the misdirection must be so perfect that sleight of hand is superfluous.

We’ve talked a lot so far about how magicians misdirect your attention. But what about sleight of hand? How does a magician learn to perform flawless sleights, and are any parts of the maneuver more important than others?

Sleight of hand involves making your hand movements ambiguous so that it looks like you are doing one thing when in fact you are doing another. For example, the “French Drop” is a classic sleight in which a coin is apparently removed from one hand by the other and then moved to another position in space before revealing that the coin has disappeared. The moves take a lot of practice to perfect, but nobody has examined scientifically the critical aspects of the maneuvers, until now.

![]() SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

In this famous vanish, the magician holds a coin in one hand and moves his other hand as if to grab it. But instead of taking the coin, he drops it into the palm of the hand holding it and uses his grabbing hand to provide cover. When he moves his grabbing hand away (which you are sure holds the coin), you soon see that it is empty. In fact, the coin is hidden in the palm of his holding hand in a way that makes the hand seem empty.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

Michael Natter and Flip Phillips, researchers in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at Skidmore College, recently studied the French Drop by showing videos of both novice and expert magicians performing the trick. They split the movements into three phases: the Approach phase, in which the grabbing hand is approaching the holding hand; the Mid-Capture phase, in which the grabbing hand appears to capture the coin; and the Retreat phase, in which the grabbing hand appears to move away with the coin.

Which phase is most important to the successful sleight of hand? The scientists asked naive observers to watch the videos of the individual phases of the sleight and guess which hand held the coin at the end of the video. They discovered that the Approach phase was not critical to the sleight. The subjects were unable to guess by watching Approach videos from either novice or expert magicians. The Mid-Capture phase, however, was critical. Here, subjects usually guessed the final position of the coin when novice magicians performed the trick but not when experts performed it. The same was true for the Retreat phase, though the effect was not as big as in the Mid-Capture phase.

These results suggest that skilled magicians are more proficient than amateurs in making ambiguous hand movements during the Mid-Capture portion of the trick. They are so good that the parts in your brain that perceive biological motion cannot tell the difference between a real grab and a fake grab.

![]()

Steve is talking to Scotto. “Now, there’s no need to keep that card to yourself. Show it around as we set up our first technological demonstration, our first installment of the Wonder Show. Whatever you do, Scotto, it is critical that you keep your card in mind throughout the show. Some of the technology depends on it.”

Susana hands Steve a Polaroid camera.

Steve says, “To ensure you don’t forget, we’ll take a picture of you and your card. Okay, hold your card right up next to your face, facing me. Good. Think about the card and say cheese.” Steve presses the shutter and the camera spits out a Polaroid image.

Steve turns to Scotto again and says, “This Polaroid camera has been specially modified to image your two brain hemispheres. We call it the ‘Hemi-roid.’ We can use the image to create an exact replica of your brain. Please remain seated while your Hemi-roid develops.”

The picture shows Scotto with his card held to his face. But in silhouette over his forehead a line drawing of a brain has appeared.

To make this happen, we placed a transparency of a brain over the film box, between the lens and the film, within the Polaroid camera. Thus all of the images taken with the camera have a big black line drawing of a brain superimposed. The trick here is to know how to line up the brain image with the head of the subject. Like everything else, it takes a bit of practice.

It must be said, we are a bit wooden in our acting skills. It’s one thing to get up in front of a group of peers and talk about research. We’ve done this enough that public speaking is second nature. The problem we have with our act is the script. When we speak about science, we can make up the specific wording as we go. But with the magic act, there are specific lines that must be said in a specific order and with specific inflections and emotions. Acting is a critical skill for a magician. Robert-Houdin once said, “A magician is an actor who pretends to have real powers.”

Susana approaches Scotto while Steve returns to the stage. “May I have your card?” Scotto hands it over. “The memory of your card is now engraved in your brain, and we also have a picture of the card—and your brain—so we can simply dispose of the actual physical card,” says Susana as she rips the card into little bits. “But just for further reminder, I’ll give you a little receipt to hold on to.” Susana returns a card fragment to Scotto.

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

Why rip up Scotto’s card now? Because while Susana is ripping up his card, she carries out a classic sleight in magic—the switchout. She is secretly holding the fragment from the duplicate card—the one inside the Jell-O brain—between her index and middle fingers. Once Scotto’s card is completely ripped, Susana then hands Scotto the fragment from the brain card, as if it came from the newly torn jack. Later, when we remove the jack from the brain, Scotto will find that the fragment he is holding impossibly and exactly matches the missing corner. Pure teleportation!

It took Susana several multihour lessons with Magic Tony, and two or three destroyed decks of cards, to perfect the sleight. She does it brilliantly in the audition, raising her gaze to look Scotto in the eye and misdirecting his attention at the critical time of the switch. Scotto will tell her later that he knew she must be performing a switchout when she ripped his card, but nevertheless he couldn’t detect it when it happened.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

After she rips the card, Susana returns to a little table near center stage, which supports a crystal goblet. “Remember to keep your card in mind,” says Susana, as she deposits the bits of Scotto’s card into the glass and covers it with a drape.

Steve puffs himself up and announces, “Ladies and gentlemen, Susana will now introduce the highlighted technology of our show. It’s the Digital Optical Volumizing Electronic Positron-Accessing Neuroprinter—or, for short, the DOVEPAN.”

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

This is a joke designed for an audience of magicians. A dovepan is a gimmick made of two nested pans with a large covering on top—roomy enough to hold live birds, birthday cakes, you name it. You can buy them in every magic shop. The magician displays the bottom pan, which is empty. He covers it and then waves his magic wand. The top pan drops down into the bottom pan automatically by virtue of a spring-loaded mechanism that is activated when the top and the bottom pan meet. He then removes the cover. Voilà, a dove flies out. Or a rabbit hops out. Or—you guessed it—a Jell-O brain appears. It looks like magic.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

Our dovepan rests on a small table, covered by a surgical drape, to the right of the stage. We embellished it with a huge handle and various electronic devices bulging from its top. Mad science: check.

Steve says, “The DOVEPAN will now analyze Scotto’s hemorrhoid—er, Hemi-roid—and use it to create an exact replica of his brain.”

Steve approaches Scotto and says, “May I grab your Hemi-roid?” Finally we hear a few snickers from the serious (not easy to please, not easy to fool) crowd. We both think this is a good sign.

Steve holds up the photo to the jury and hands it to one member to pass around, saying, “Notice that this Hemi-roid is a true and factual representation of Scotto’s brain.” He retrieves the photo and mounts it on the dovepan. Susana says, “And now the dovepan will use the Hemi-roid to make an exact replica of Scotto’s brain!”

Susana rubs her hands, mad-scientist style. “We’ll need to add raw materials to build a brain,” she says. “A brain needs lots of fat.” Steve grabs an ice cream scoop, scrapes a large dollop of Crisco from a bucket, and flings it into the bottom portion of the dovepan. The scoop strikes the pan’s edge, ringing it like a bell.

Then Steve says “We need protein” and hands a large carton of body-building protein powder to Susana. She peels off the lid and shakes “protein” into the pan. Next Steve picks up a full sugar dispenser that he recently stole from a truck stop. Susana pours it all into the pan and declares, “Sugar!”

“And now, most important, salt,” says Steve. “Salt is critical because its ions—sodium and chloride—allow neurons to communicate over long distances.” Steve unscrews the top of a saltshaker and, with great exaggeration, pours a stream of salt into his left fist.

“The neural signals travel from this end of the neuron”—he moves his right hand along the pathway of the activity from his left hand, up his left arm, and across his chest to Susana’s waiting outstretched hand—“all the way over to the postsynaptic neuron, represented by Susana’s right hand.”

At this point, Steve suddenly begins an incredibly dorky rendition of the classic break-dancing step in which a wavelike motion begins at the end of one arm and flows through the other arm.

“This process is called ‘saltatory conduction,’ “ says Steve, as they hold hands and the wave continues through Susana’s body.

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

When Steve’s right hand travels across his body, he is actually retrieving a fake thumb tip—a rubber gimmick that looks just like a real thumb—that was used to sequester the salt inside his left fist. His right hand delivers the fake thumb tip to Susana’s waiting gloved left hand. When the undulating duet is done, Steve removes Susana’s left glove, which serves to get rid of his thumb tip. Susana is also wearing a fake thumb tip filled with more salt in her right hand, under her glove. At the end of her dance number, she removes her right glove, palms the thumb tip into her right fist, and pours her salt supply into the dovepan.

It appears as if the salt has traveled through two bodies.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

With the salt now in her right hand, Susana says, “And now, the postsynaptic neuron has been activated.” She pulls up her lab coat lapels and moonwalks over to the dovepan as Steve plays a Michael Jackson tune on his iPhone. Steve hears a few members of the jury say, “Choreography!” as if crossing one performance element from a list.

The music stops as Susana pours salt into the dovepan. She places the lid on the device, presses the three-second timer button, and says, “Now, we wait.”

![]()

As we embellished our dovepan before heading off to the Magic Castle, we realized that essentially, in magic, there are no new tricks. Nearly all the illusions you see in modern magic shows were invented in the nineteenth century or earlier by showmen in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Modern magicians have been updating and elaborating the same basic tricks ever since.

Moreover, magicians have long excelled at engineering. In the second century BC, Heron of Alexandria, a Greek-Egyptian inventor, made temple doors open and close magically during religious ceremonies. The secret mechanism was a predecessor to the steam engine. Magicians also used to be famous for inventing self-operating machines, called automata, with purely mechanical moving parts. For example, in 1739, Jacques de Vaucanson invented the digesting duck, which appeared to have the ability to eat kernels of grain, metabolize the grain, and defecate.*

“Heron’s Temple.” Heron of Alexandria invented the automatic opening of doors. The secret mechanism, called aeolipile, consisted of a vessel with two curved pipes connected to it. When the water in the vessel boiled, the steam came out of the tubes, activating a rope mechanism that opened the doors slowly and majestically. (Illustration by Victor Escandell for the Fundación “la Caixa” museum exhibit “Abracadabra, Ilusionismo y Ciencia”)

In the mid-nineteenth century, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, who is considered the father of modern magic (and the main inspiration for Ehrich Weiss, better known as Harry Houdini), used his engineering skills as a clockmaker to construct amazing mechanical contraptions that seemed to operate by magic. A device similar to two different famous Robert-Houdin automata called “Orange Trees” is featured in the 2006 movie The Illusionist. Robert-Houdin also invented the first electric house security alarm and other Rube Goldberg contraptions such as a three-tiered alarm clock system that set off alarms at different places around the house and at different times while also triggering the release of morning oats to his mare in the barn. Other renowned magicians, such as André-Jacques Garnerin and John Nevil Maskelyne, made important technological advances by inventing the parachute (Garnerin) and the first ribbonless typewriter and the coin-operated lock for vending machines and, unfortunately, pay toilets (Maskelyne).

We read Robert-Houdin’s 1860 autobiography—Memoirs of Robert-Houdin, Ambassador, Author, and Conjurer, Written by Himself—to learn more about this period. This guy’s life story reads like a rip-roaring Victorian novel. One of his tricks stands out as an example of how devious magicians are and how little has changed over the past century.

While visiting a prominent local sheikh at a remote desert compound, Robert-Houdin demonstrated his bullet trick. Penn & Teller have a killer bullet trick that is based on this earlier version.

In the trick, which he demonstrated to large audiences in Algiers, Robert-Houdin dared a volunteer from the audience to shoot him point-blank. Having prepared his apparatus in advance, he “caught” the bullet in his teeth.

But here, in the desert, Robert-Houdin was taken by surprise. A skeptic challenged him then and there: “I will lay out two pistols. You choose one. We will load it and I will defeat you.”

Robert-Houdin had to buy time. “I require a talisman in order to be invulnerable,” he replied. “I have left mine at Algiers. Still, I can, by remaining six hours at prayers, do without the talisman and defy your weapon. Tomorrow morning at eight o’clock, I will allow you to fire at me.”

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

The magician spent two hours that night ensuring his invulnerability. He took a bullet mold out of his pistol case. Then he took soft wax from a candle, mixed it with a little lamp black, and made a wax bullet. He hollowed it out so it would not be hard. Next he made a second ball and filled it with blood. Robert-Houdin later explained that an Irishman once taught him how to draw blood from the thumb without causing any pain.

The next morning, Robert-Houdin stood fifteen paces from the sheikh, who held the loaded pistol. The gun went off and the bullet appeared between Robert-Houdin’s teeth. Furious, the sheikh lunged for the second gun, but Robert-Houdin reached it first. “You could not injure me,” he said, “but you shall now see that my aim is more dangerous than yours. Look at that wall.” The Frenchman pulled the trigger and on a newly whitewashed wall there appeared a large splotch of blood.

Robert-Houdin had used sleight of hand to put the wax bullet into the first gun, and it broke into pieces when fired. He held a real bullet in his mouth and—voilà. With equal dexterity, he placed the blood-filled bullet in the second gun before firing it. The sheikh nearly fainted.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

THE MECHANICAL TURK

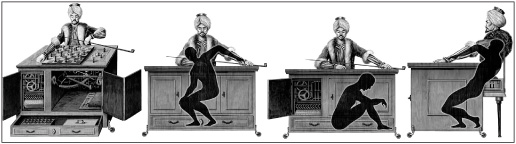

![]()

The first magical contraption to become world famous was “the Turk,” an automaton that played master-level chess, invented by the Hungarian baron Wolfgang von kempelen in 1769. Spectators were welcomed to see the calculating machinery inside its box after each show. Stories about the Turk, especially who discovered its secrets, are legion. One account states the real workings of the Turk were revealed in 1827, when two skeptical young boys from Baltimore hid and watched backstage as a man climbed out of a hidden compartment. The local newspaper broke the story that the chess-playing “automaton” was a hoax.

Perhaps we’ll never know the full truth, but Robert-Houdin’s account of its origin is as plausible as any. He writes that in 1769, a revolt broke out in a half-Russian half-Polish army regiment stationed at Riga, in what is now Latvia. The leader of the rebels was an officer named Worousky, a man of great talent and energy. Troops were sent to suppress the revolt, and in the rout both of Worousky’s thighs were shat tered by a cannonball. He threw himself into a ditch behind a hedge and at nightfall dragged himself to the adjacent house of a kindly physician named Osloff. After gangrene set in, both of Worousky’s legs were amputated.

Not long after, Wolfgang von kempelen, a celebrated Viennese inventor of mechanical devices, visited Osloff. Together they devised a plan to help Worousky, who had a bounty on his head, to escape. Worousky was a brilliant chess player, which gave von kempelen the idea for an automaton chess player. In three months, they built the device—an automaton represented as the upper body of a Turk seated behind a box the shape of a chest of drawers. In the middle of the top of the box was a chess board.

Before each game, von kempelen opened the doors to the chest so people could see various wheels, pulley, cylinders, springs, and so forth. The Turk’s robes were raised so the “body” could be inspected.

After closing the doors, von kempelen wound up one of the wheels with a key. The Turk nodded its head in salutation, placed its hand on one of the chess pieces, raised it, and deposited it on the board. The inventor said the automaton could not speak. It would signify “check” to the king by three nods and to the queen by two.

The legless Worousky was stowed away in the body of the legless Turk. As soon as the robes fell, he would enter the Turk’s upper body, passing his arms and hands into the figure and his head into the mask.

According to Robert-Houdin, the magical machine gave Worousky an escape and a livelihood. The Mechanical Turk toured Europe extensively and won nearly all of its chess matches.

“Turk automaton.” The operator could hide under the shell of the automaton. (Illustrations by Victor Escandell for the Fundación “la Caixa” museum exhibit “Abracadabra, Ilusionismo y Ciencia”)

Throughout the nineteenth century, magicians were at the forefront of technology and invention, but at some point the development of new effects essentially stopped and magicians clung to their (now) old traditions and technologies. Much of the low-hanging fruit had been plucked, and it was easier to continue to do the same old tricks. More recently, a few magicians, such as Jason Latimer, the winner of the world championship of magic (FISM) in 2003, have embraced modern technologies—lasers, holography, fiber optics, electronics, robotics—and used them to make wholly modern magic and live onstage special effects.* The basic effects on the brain are still the same (to the best of our knowledge, they haven’t developed truly new categories of magic effects yet), but they make fresh and exciting new variants on old tricks using high technology.

MAGICIANS AND SPIES, UNITE!

![]()

In 1952, the CIA asked one of the nation’s most respected magicians, John Mulholland, for help. Could the master close-up sleight-of-hand artist teach American spies a trick or two in their escalating cat-and-mouse game with Soviet spies?

The reasoning made sense. Both spies and magicians must elude detection. The CIA’s many dirty tricks—poison darts, knockout powders, drugs, poisons, tiny cameras—would be operationally useless unless field officers and agents could manipulate them. If Mulholland could deceive an audience that was studying his every move from a few feet away, it should be possible to use similar tricks for secretly administering a pill or a potion to an unsuspecting target.

Mulholland obliged by writing two illustrated spy manuals. The first describes and illustrates (with delightful drawings) numerous sleights of hand and close-up deceptions for secretly hiding, transporting, and delivering small quantities of liquids, powders, or pills. The second manual describes methods used by magicians and their assistants to secretly pass information.

The George Smileys* of the day embraced the techniques and, to read modern accounts, became adept at misdirection, change blindness, escapology, and creating cognitive illusions. As the Cold War heated up, the CIA’s field officers grew ever more inventive under Mul-holland’s guidance.

By the 1970s, however, attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro with exploding cigars and similar escapades began to embarrass the CIA. In 1973, the agency’s director, Richard Helms, ordered all copies of the classified magic manuals to be destroyed. The results of such chicanery were just too unpredictable.

For decades, rumors of the manuals’ existence circulated in intelligence circles, until parts of them were unearthed and published in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In 2007, a retired CIA officer, Robert Wallace, discovered a complete set of the lost manuals and published them, with the historian H. keith Melton, under the title The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception.

The book reveals that our spies knew about change blindness. An intelligence officer would always park his car at the curb directly in front of his house. On the day a “drop” was to be left for another agent, the officer would park his car across the street from his house. The agent would notice this and pick up the secrets, but the enemy’s surveillance team would not see anything out of the ordinary.

This ploy was successful in Moscow, home to the heart of the kGB’s surveillance operation. The American intelligence officer would adopt unvarying patterns of daily movements in and around the city. After a few months of this unchanging travel pattern, the American spy would “disappear” during his “normal” commute for a brief time—enough to accomplish a dead drop or post a letter—before reappearing at his normal destination only minutes behind schedule. The watchers, lulled by the monotony of his routine, were not alarmed.

* Smiley is the main character in John le Carré’s novel The Spy Who Came In from the Cold.

In magic, a larger action covers a smaller action as long as the larger action itself does not attract suspicions. One CIA officer took his dog out for long walks at night (the large action), which gave him numerous opportunities to secretly mark signal sites and service dead drops (the smaller actions). The surveillance teams became used to the pattern and never got suspicious.

Magicians manage “sight lines” to create illusions. Your vantage point in the audience can be used to trick your visual system, as we saw with Vernon’s Depth Illusion in chapter 2. A CIA officer discovered that when he was walking in urban areas, on routes he used frequently, the surveillance team trailing him was always a few steps behind. When he made a right-hand turn on foot, he would be in the clear—“in the gap”—for a few seconds. He used that gap to conduct his clandestine moves, out of sight.

Mulholland also gave lessons on misdirection. In the days when many people smoked cigarettes, he instructed officers to lift a flaming match to light a target’s cigarette while using the other hand to drop a pill into the target’s drink.

To make a miniature camera “disappear” after taking a secret photo, the spies borrowed a magician’s tool called a holdout—a simple piece of elastic that retracts an object up a sleeve. They hid toolkits and microfilm in buttons, coins, boot heels, and suppositories.

Houdini inspired many of the spies’ techniques, including the Identical Twin Illusion (which they called “identity transfer”), which involves disguising two people to look like the same person. One spy went a step further and dressed up in a giant Saint Bernard dog suit so that when he was “taken to the vet” (actually a safe house) he could pass on documents before returning home in the dog suit. A real 180-pound Saint Bernard also lived there.

When the timer chimes, Susana lifts the lid of our dovepan and reveals that the ingredients have been transformed into a human brain. Well, not a real brain, but as realistic as one made of Jell-O can look.*

![]()

We made a human brain out of Jell-O using a classic Halloween brain recipe.

1. Spray a small amount of cooking spray inside a plastic brain mold.*

2. Place contents of 2 large boxes gelatin mix (peach or watermelon) into a large bowl.

3. Add 2½ cups boiling water. Stir gelatin with a whisk until it is completely dissolved, about 3 minutes.

4. Stir in 1 cup cold water.

5. Add 1 can nonfat evaporated milk and stir for 2 minutes.

6. Add a few drops green food coloring (to make the brain grayish pink); stir.

7. Pour gelatin mixture into plastic brain mold.

8. Set mold in refrigerator overnight.

9. Stick card into brain once it’s solid while still in mold. The small entry point cut will be unnoticeable on the bottom of the brain.

10. Add cerebral arteries using sparkly red cake decorating frosting.

* These are available at http://www.shindigz.com/party/Gory-Brain-Mold.cfm.

Steve says, “And here we have it, ladies and gentlemen—an exact replica of Scotto’s brain!” Steve removes it from the dovepan and places it on a second small table, visible to all.

“You all must be asking yourselves, how does this incredible DOVEPAN technology work?” says Susana. “Well, it’s based on genetic manipulation, leading to rapid neural growth, directed by the model provided by Scotto’s Hemi-roid.”

At this point, we each carry out a rope trick to illustrate various aspects of how the DNA is manipulated in the dovepan so as to rapidly grow an exact replica of Scotto’s brain. The strands of rope represent strands of DNA, and our scientific explanations are nutty, but we handle the ropes okay.

We are feeling pretty good about the show. A little more than halfway through, we’ve completed the trickiest sleights in the act. The methods thus far have been standard magic fare, and we are entering the portion of the show with the cool mentalism tricks.

So it comes as a shock when one of the jurors says, “I think I’ve seen enough.”

![]()

We are now in a much larger bar upstairs at the Magic Castle, consoling ourselves with expensive Perrier-Jouet champagne. Magic Tony joins us. We tell him that we have just been summarily dismissed from our audition, halfway through. Now we know how those poor talentless saps from The Gong Show felt. But we are determined to celebrate, no matter what. We are so embarrassed that we are overtaken by the giggles, like that poor Spanish politician who had admired the firefighters’ “equipment.”

The conversation inevitably turns to what went wrong. We know we are no Penn & Teller, but we do think we achieved what we set out to do. A few minor rough spots, to be sure, but nothing horrifically bad. Did we fail to earn their trust? Were we an embarrassment to the professionalism of Magic Castle members? Did we flub our tricks?

Disappointingly, we didn’t even get to show our coolest tricks! The rest of our act is a humdinger. Here’s what we had planned.

We bring two volunteers on stage and have them play our version of a mentalism puzzle called kirigami, invented by Max Maven. It involves folding and cutting paper with letters of the alphabet to find four-letter words. The volunteers think they are free to find a variety of words, but we have set up the puzzle to force them to choose only two: “cage” and “head.”

We bring out homemade “mind-reading helmets” constructed out of spaghetti strainers adorned with flashing lights and buzzers—they look like Acme bombs purchased by Wile E. Coyote—and each push a secret remote button in our jacket pockets to make the helmets buzz as the volunteers concentrate on their words, which are being “transmitted” through the air to the dovepan.

After three seconds, Susana lifts the cover of the dovepan and what do you see? Why, it’s the confluence of the words “head” and “cage”: our technology has generated the head of the actor Nicolas Cage! (It’s amazing what you can buy on the Internet.)

Finally, Susana uncovers the goblet containing the card bits but finds that the pieces are missing. They have been replaced by brain matter—bits of Jell-O. Susana takes a taste just to be sure. Yep—definitely human brain matter.

![]()

SPOILER ALERT! THE FOLLOWING SECTION DESCRIBES MAGIC SECRETS AND THEIR BRAIN MECHANISMS!

The goblet actually consists of two halves separated by a double-sided mirror. One half contains the card shreds and the other the brain matter. Susana spins the goblet under the cover of the drape when she wants the transformation to take place.

END OF SPOILER ALERT ![]()

We express puzzlement at this unexpected event. If the card has turned into brain matter, then what happened inside the brain?! We tell Scotto that we must perform exploratory surgery on his Jell-O brain to find out.

In the brain, we find Scotto’s card with a piece missing, which, of course, exactly matches the jagged edge of the fragment he still has in his hand. Scotto literally kept his card in mind, and our devices produced a replica of his brain, memories, thoughts, and all!

If only they had let us finish! We’re sure that this finale would have impressed the judges.

Just then Tim, the head of the committee, approaches us in the bar. Yes, there were a few problems with our act—we definitely shouldn’t quit our day jobs—but there’s nothing to keep us from joining the Magic Castle as Gold Pin members.

In response to our confused expressions, he says that they cut our act short because we showed proficiency and they had four other auditions to do that night.

“Congratulations!” he said, shaking our hands.

“We made it!” we whooped, clinking our glasses.