Chapter 17

Saving Forests

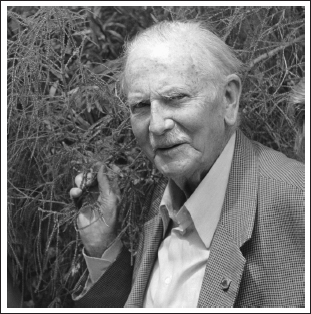

Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889–1982) was one of the earliest foresters to realize the terrible harm that was being done to the planet through deforestation. He saved and restored forests all over the world, including in many parts of Africa. It’s estimated that at least 26 trillion trees were planted during his lifetime by organizations he founded or advised. (CREDIT: BARRIE OLDFIELD)

When I arrived at Gombe in 1960, the forests, home to the chimpanzees, stretched for miles to the north, south, and east of the park (the west is bounded by Lake Tanganyika). But by the early 1990s, when I flew over Gombe and the surrounding area in a small plane, I realized with dismay that outside the tiny, thirty-square-mile park virtually all the trees had gone. Only in the really steep-sided ravines, where even the most desperate people could not farm, could I see a few small forest remnants. Chimpanzees and most other animals bigger than a mongoose had gone. Humans were struggling to survive on the overfarmed, eroded soils. It was clear that there were more people settled there than the land could support, people too poor to buy food elsewhere, cutting down the last of the forest in their desperate struggle to grow crops to feed themselves and their families.

The Gombe forest is just one among thousands worldwide that survive as fragments, cut off from other forests or fragments of forests by human activities. Nature’s bounty is depleted as a result of poverty, on the one hand, and, on the other, the unsustainable lifestyle of a growing number of the elite and the middle class. It is the consumer-driven, materialistic lifestyle, exported from the West to the developing nations, that creates the market for products from the forests and that encourages our greedy desire for more and more stuff that only too often we don’t really need. As Gandhi famously said, “Nature can supply human need, but not human greed.”

Huge areas of forest are being destroyed or degraded by the extraction of timber, minerals, and oil; by monoculture tree plantations, ranching, and farming; and by commercial developments. The list is long, and we are shocked when we hear of the number of animals and plants that become locally or totally extinct each week, the spread of the deserts, the shrinking supplies of freshwater. It strikes terror—and anger—into the hearts of all of us who care about the natural world and the future of our children. Even “protected” forests are often at risk.

In fact, it is all so grim that some people who start off fighting to save forests, or a particular piece of forest, simply become too depressed to carry on. While I can well understand the depression, we must not, must not, must not give up. Instead, we have to fight harder and support the efforts of those who are working tirelessly, from various perspectives, to save what is left.

Of course the destruction of our forests is not a new phenomenon. Since the dawn of history, people through the ages have sought wood for building cities and warships, and cut down forests to have access to the fertile forest soils for growing crops.

It is not my intent to delve deeply into these stories of past destruction but simply to point out that the onslaught of “man” against “tree” is as old as the hills. Back in 1875 that remarkable priest Père Armand David recorded what was going on in China. “From one year’s end to another,” he wrote, “one hears the hatchet and the axe cutting the most beautiful trees. The destruction of these primitive forests, of which there are only fragments in all of China, progresses with unfortunate speed. They will never be replaced. With the great trees will disappear a multitude of shrubs which cannot survive except in their shade; also all the animals small and large which need the forest in order to live and perpetuate their species.”

He went on to write, “It is unbelievable that the Creator could have placed so many diverse organisms on the Earth, each one so admirable in its sphere, so perfect in its role, only to permit man, his masterpiece, to destroy them forever.”

About the same time, the redoubtable plant hunter E. H. “Chinese” Wilson, when collecting in Japan, came upon the stump of a huge yakusugi cedar that had been felled in 1586, when it was estimated to be over three thousand years old. It is now known as Wilson’s Stump. The circumference of the stump measures some 45 feet, and it is about 4.5 feet tall. The stump is hollow and the floor space inside is 16.5 square meters (178 square feet)—quite big enough for three or more people to stand inside. It is situated on the Okabuhodo (“big trees”) Trail in Yakushima Island. Many tourists go there to marvel at the huge cedars, and one of them told me that it is very spiritual inside Wilson’s Stump. Someone has erected a little shrine in there, and there is the sound of running water.

When I read about the felled giant, I felt a surge of anger. Was not the tree, quite as much as the Homo sapiens who destroyed it, a “masterpiece of the Creator”?

Another massacre took place in the ancient redwood and Douglas fir forests along the West Coast of the United States. I had firsthand experience of the devastation that was wrought, and that is still continuing today, when Mike Fay invited me to join him and environmental activist Lindsey Holm for two days during their walk through the past range of these forests. It was truly a marathon undertaking—they told me the forests had once covered some two million acres (3,125 square miles) along America’s West Coast. Heavy logging began in 1880 after a gold rush brought countless people to the region who, when gold was not found in great quantities, turned to exploiting the forests for the rapid development of San Francisco and other cities.

Just being in the forest with those giant trees, and with the stumps of so many that had been felled, was humbling. I felt I was in the presence of an ancient wisdom. Sometimes I sensed a sadness, as though the trees were dreaming of times past—when the world was young, before the white man invaded and raped their forest; at other times I sensed an anger because of all the terrible destruction. But most strongly of all I sensed a vast endurance.

Inexorably, century after century, the vandalism of the world’s forests has continued. In 2002 I attended the fiftieth-anniversary meeting of the Association Technique Internationale des Bois Tropicaux in Rome. One speaker, reviewing the history of the organization, described how, after World War II, it was clear that the European forests could not provide enough timber to rebuild the cities and towns destroyed by the years of bombing. And so, he said, the European timber companies got together and planned how they would divide up the forests of Asia, South America, and Africa so that they would all have access to the necessary resources.

I listened with mounting horror to this account of premeditated plunder—it was a terrifying new chapter in the sorry litany of rich nations stealing the natural resources from other parts of the world. An early indication of the dark side of globalization, when giant and ruthless multinational companies would gradually seize ever-greater control over governments, economies, natural resources, small businesses—and lives. Moreover, our human populations are growing everywhere, so that forests are increasingly cut down to provide fertile soil for growing crops and feeding livestock, and for space to live. So while it is true that humans have been exploiting forests for hundreds of years, the situation is now infinitely more challenging. We must strive, on the one hand, to alleviate poverty and help billions of peasants to find environmentally sustainable lifestyles, and, on the other hand, we must encourage the growing well-to-do societies to do well with less, for it is this “consumer society,” with its desire for ever more “stuff,” that gives such power to the big corporations.

And make no mistake, this is the hardest battle—fighting vested business interests, powerful and unscrupulous multinationals, and corruption.

Today, a huge threat for any tropical forest that is not fully protected is China’s voracious appetite for timber for building materials to feed her rapidly growing economy. And because of the migration of rural populations seeking new livelihoods in urban areas—said to be the greatest migration in human history (four hundred new cities need to be built!)—China is buying timber (and mineral) concessions in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Canada, wherever forests have been left standing. Western countries did exactly the same thing—but China is very much larger.

Of course, China is not alone. The Canadian government is allowing the exploitation of the tar sands in Alberta that is leading to the desecration of thousands of square miles of pristine forests. American agribusiness is persuading African governments, with false promises of the wealth it will bring, to lease (or sell) hundreds of square miles of their precious rain forests for the growing of monocrops or biofuel. And on and on.

Let me give just a few examples of the massive scale of some of the operations that are destroying our forests and that must be tackled—and somehow stopped. Or that must be conducted in a much, much more responsible and sustainable way.

The Problem with Tree Plantations for Our Paper and Timber

Countless old-growth forests have been destroyed to make way for industrial plantations, especially for growing pines, firs, acacia, eucalyptus, and teak. Plantation wood is sold for timber. It is also destined to become wood pulp for paper. This book is written on paper, and the better it sells, the more paper it will use—which is why we insisted it be printed on paper that is at least partially made from recycled products. It is a fact that the world uses an enormous amount of paper. How many pause to think where this paper comes from? Most of it started as trees that we cut down and ground into pulp. Incalculable damage to forests around the world is caused by our use of paper.

Most people assume that although using old-growth forests is clearly a bad thing, if trees are specially grown for paper, it should be okay. In some cases this is undoubtedly true, but sadly this is often not the case. A group of NGOs, including WWF and Greenpeace, along with local groups, carried out case studies in seven countries to document the negative environmental impact of industrial tree plantations for pulpwood. They found in many cases that natural forests had been destroyed and replaced with monocultures of fast-growing species that, only too often, needed large amounts of water. This had caused streams and rivers to dry up.

Despite promises by the companies involved, rural poverty had not been alleviated but had actually increased, and far fewer jobs had been created than the villagers had been led to expect. Moreover, the paper mills built to process the wood not only used a great deal of energy, they were also very polluting. (I know, from driving past a paper mill in Maine in the United States, that the smell is truly terrible: I asked a local how he could stand it and he replied, “We tolerate it because it is the smell of money!”)

In all seven countries the investigators found that the introduction of pulpwood plantations had led to protests (sometimes violent ones) from local communities. The Brazilian Landless Workers Movement—the largest land-rights movement in the world—has repeatedly targeted pulpwood plantations.

One company in particular has caused enormous environmental and social damage: Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), part of the giant Sinar Mas Group (a Chinese/Indonesian conglomerate). It has been a focus of environmental and human rights groups for years. As a result of mounting international protest, the company has just announced a very progressive forest policy that, if respected, could be equated to a “zero deforestation” pact.

The Hidden Cost of Oil

Then there are the often rapacious operations of the petrochemical companies. I learned a little bit about the situation during a visit to Ecuador a few years ago. Groups of indigenous people were uniting as they tried desperately to prevent oil companies from operating in their ancestral lands. Unless there was some miracle, I was told, their rain forests would be invaded, and many of the people would be forced to leave.

I met with several tribal leaders of the Achuar and Shuar people, and they told me of past persecution and present fears for their future. I was so upset and moved by their story, I agreed to join them for a press conference, during which we made a passionate plea to protect the forest and its indigenous people. But the hold of the petrochemical companies over the government was strong—and the explorations and destruction began anyway.

Our thirst for oil in the developed world is leading to untold destruction in the developing countries. Everyone knows what this has meant for the Middle East, the US Gulf, and Alaska—these things are always discussed on TV. But few people think about the devastation that is ongoing in Africa—except, perhaps, for Shell’s operations in Nigeria, which have received a great deal of coverage.

In the early 1990s I flew in a small plane over parts of the Republic of the Congo (Congo-Brazzaville), Gabon, and Angola. We flew quite low over the rain forest canopy and I was shown some of the concessions made by the governments of those countries to different petroleum companies, including Shell, BP, and Elf. I was horrified by the devastation that had been inflicted on the environment: the straight paths that had been slashed through the green virgin forest for seismic-drilling operations, and in one place a huge treeless clearing that had been hacked out of the forest where the workers of one of the companies were based. It showed a complete lack of respect for the integrity of the forest and its people.

Those of us who know what is going on are deeply concerned that oil deposits have been discovered in the so-far-unspoiled Albertine Rift area of Uganda, where JGI is working to protect chimpanzees and their forests.

Nor should we forget the monstrous threat created by the runaway desire to grow more and more crops for biofuel. Too many people believe biofuel is the answer to our energy needs. I just wish there was more TV coverage of the vast areas of African forest that have been destroyed in order to grow monoculture crops to be transformed into energy so that Ms. X can drive her car to the supermarket every time she forgets a packet of potato crisps rather than walk or take a bus, or every time Mr. Y wants a new, fast gas-guzzling car to impress his new girlfriend.

More and more Africans are protesting, at the local level, as they begin to understand how their land is being stolen for profit—and sometimes demonstrations can pay off. When President Museveni of Uganda approved the clear-cutting of a forest block for conversion to sugarcane for biofuel, he was forced to cancel the deal when the citizens of Kampala took to the streets to protest. It was a protected forest and, they argued, it was protected for the good of the people of Uganda.

Forests and Food

I’ve already talked about the shocking impact of industrial farming on forested areas around the world. Here let me just mention the consequences of the desire of more and more people to eat more and more meat. Millions of acres of forest in many parts of the world are destroyed each year just to provide grazing or to grow corn for feeding cattle or other livestock. More than 60 percent of deforested land in the Brazilian Amazon ends up as cattle pasture.

I have seen this devastation with my own eyes in parts of Africa and Central America. It is just one more example of short-term thinking, illustrating the unscrupulous dealings of those who see the chance of making a quick buck. Not only will undisturbed forests continue to provide medicines and food for generations to come but, as we shall discuss, they also play a vital role in regulating global climate.

Another threat to many forest ecosystems is the commercial hunting of wild animals for food, known as the bushmeat trade. In a number of forests in the Congo Basin this trade has boomed, in part due to the presence of logging companies, since even if the loggers strictly follow the prescribed code of conduct, they nevertheless make roads deep into the heart of the forest.

Hunters follow the roads, often riding on the logging trucks, camp at the end of the road, and shoot everything edible. This slaughter, so different from the subsistence hunting that has been a way of life for forest people for centuries, is unsustainable. Truckloads of smoked meat from elephants, apes, monkeys, antelopes, pigs—and in fact any creature that can be sold in the markets or sent overseas—are being taken out of the forests.

And when the balance of an ecosystem is upset like this, things begin to go wrong. We are just beginning to understand the ways that all life-forms are interdependent. In Africa and Southeast Asia, for example, seeds are primarily dispersed by the great apes as well as by many other mammals and birds. Not long ago it was discovered that there are fewer seedlings growing in forests where there’s a lot of hunting and killing of animals, especially in forests where the number of primates has dropped significantly.

In other words, we must respect and protect the intricate mix of animal and plant species in order to preserve a natural forest’s health and long-term survival. So even if a timber company practices “sustainable” logging—taking out only trees above a certain size and then moving on to a new concession, leaving the area to regenerate over the next twenty or more years—if animals are being slaughtered indiscriminately, the forest will become increasingly unhealthy.

Illegal Logging

Toward the end of the 1990s I spent a few days visiting Birute Galdikas in the forests of Tanjung Puting National Park in Indonesia. We followed a river that wound through the trees, and from our small boat I saw a wild orangutan for the first time, and an old male proboscis monkey looking down at me over that long bulbous nose that makes this species one of the most extraordinary of all the monkeys. It is a wonderful rain forest—an area of great biodiversity. But everywhere I heard stories of the illegal logging that was going on—even within the park. In fact, the river that we followed to reach the orangutan camp was sometimes all but impassable because of the sheer volume of illegally logged tree trunks that were being floated out of the park. And now the forests of Indonesia have also been harmed by raging fires, often lit to clear huge areas for palm oil plantations—which are all too often used for biofuel. Because of all this, the orangutans are being driven to extinction.

Warriors Fighting for the Forests

I remember hearing, in the early 1970s, about a group of women in India who were desperate to save the forest, on which they depended for their livelihood, from being cut down. So they went and joined hands around some of the trees. I was inspired by the story, and though I didn’t know much about it, I talked about these women during some of the lectures I was giving while teaching at Stanford University.

Since then I’ve learned more about this—including the fact that there are many different versions of how it began! However, it seems that one of the leaders of the movement suggested that when their local forest was due to be felled by the forestry department, the villagers should hug the trees. One woman, Bachni Devi, heeded his advice and she persuaded about twenty others, mostly women, to join hands around the tree trunks. The plan worked, the foresters gave up, and the trees were saved. News of that first protest spread throughout the region, and soon there were hundreds of decentralized and locally autonomous initiatives, led mostly by village women, embracing trees in defiance of the foresters.

Thus was the Chipko movement founded. Chipko is a Hindi word meaning “hug or embrace,” and its philosophy is rooted in satyagraha, the form of nonviolent protest policy practiced by M. K. Gandhi during his successful campaign to force the British to leave India.

One of the key figures in the fight to save the forests was Sunderlal Bahuguna, for it was his personal appeal to Mrs. Indira Gandhi, then prime minister, that led to a major victory—the 1980 green-felling ban. This prohibited all cutting down of trees for fifteen years throughout the Kumaon Himalayas in Uttar Pradesh. And then, to ensure that this ban would be well understood, he undertook an extraordinary five-thousand-kilometer (over three thousand miles) walk across the Himalayas, spreading the message to all the villages he passed through. Eventually the Chipko movement spread throughout India and led to a ban on clear-cutting also in the Western Ghats and the Vindhyas. What a triumph.

There is something about ancient trees that rouses deep passions in those who care. And this is fortunate, because some of these people then dedicate their lives to protecting the forests and the humans and other animals who live in them. They are many, but some stand out because of their passion, their courage—and their persistence.

Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889–1982) was, without doubt, one of the greatest advocates for the protection and restoration of forests ever. His love for trees began when he was a small child growing up near a pine-and-beech forest in Hampshire—I described the special childhood relationship he developed with a beech tree in chapter 3. After serving in World War I he became a forester, and for the rest of his life worked to help protect forests around the globe, starting in Kenya and then working in Tanzania and Ghana. He also helped reforestation efforts in all the countries bordering the Sahara. And he extended his efforts to parts of the Middle East, Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand. It is estimated that during his lifetime at least twenty-six trillion trees were planted by organizations he started or advised and assisted. He himself planted his last tree—in Canada—when he was ninety-two years old, just days before his death. The NGO he started, the International Tree Foundation, has programs in many countries around the world. An amazing man with an amazing life.

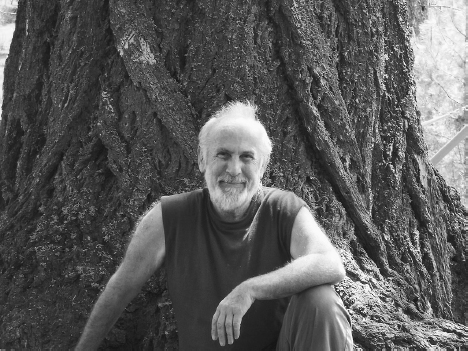

John Seed, a real warrior of the forest, fights in a different way. He became one of the first Westerners to take direct action against the timber industry, starting in his native Australia but subsequently initiating and assisting campaigns in many other parts of the world. He is one of the more inspirational and successful people on the forest-conservation scene—as a result of his interventions, hundreds of thousands of square miles of rain forest have been protected around the world. In June 2011, I was lucky enough to spend a few hours with this amazing man. We walked along the tamed beach of a Sydney marina, then climbed just up off the path and sat on the grass under a tree overlooking the water. And talked. I could have listened to his stories for days. Tales of his hippie youth, when he first began his tireless efforts to save the rain forests of the world, tales of the many extraordinary experiences that have enriched his life—and ours—since.

His hair is gray now, but he radiates peaceful vitality and quiet strength. During his years working for the trees he has clearly absorbed something of their stoic endurance.

John began life as a sculptor in metal, taking steel from metal stamping machines and transforming it into a “spiritual cornucopia of organic shapes.” In his old hippie days he moved into a commune, thinking he would organize meditation retreats and grow organic food. Then one day a timber company moved in and started logging the rain forest next door. The chainsaws were so loud, he told me, that he couldn’t meditate anymore—and that spurred him to take action.

Forest warrior John Seed is one of the first Westerners to take direct action against the timber industry. He has saved huge areas of rain forest in many parts of the world. (CREDIT: TRISH ROBERTSON)

In 1979 John joined one of the first groups of idealistic Westerners determined to actually do something to try to prevent the destruction of a forest. They followed Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, putting themselves in the path of bulldozers that were approaching to fell trees, or actually climbing into the trees themselves. Tactics very familiar today—though at that time nothing like this had ever been done to protect a forest.

The loggers still managed to cut down some trees, but were nonetheless hindered in many ways, and police were sent in to arrest the protesters. First they had to get them out of the trees. TV crews followed both sides, and there was growing sympathy for the activists among the general public. When the Australian premier finally called for a suspension of logging, it was a pivotal moment for the environmental movement in both Australia and the world. Known as the Terania Creek Campaign, it achieved international prominence.

For the next two years there were further successful direct actions on behalf of the subtropical rain forests of New South Wales. Then John turned his attention to the temperate rain forests of Tasmania—it was easy to get the attention of the media at that time, and newspapers ran photos of people chaining themselves to bulldozers or climbing up the trees that were in their path. But gradually the public lost interest in these images—or, as John puts it, “society developed antibodies” against such actions. Which meant that when the protesters were delaying the building of a road in the far north of Queensland that would give loggers access to the pristine tropical forests at Cape Tribulation, the media was no longer interested. John remembers “calling a newspaper and being told ‘ring us back when there’s some blood.’ ”

Still, they managed to stop the road building until the rainy season prevented further work. And then, in John’s words:

“The following year, while waiting for the road builders to arrive, we found a place where there was only a narrow space between the mountainside and the ocean, and here we dug holes in the ground and when the bulldozers arrived, people buried themselves up to the neck in the path of the machinery so that they had either to be dug up or crushed, there was no way to get around them.

“At first the police used shovels to try and dig people out but eventually called in a backhoe. Pictures of these huge metal buckets digging inches from protestors’ faces, when they could not even protect their heads from flying rocks, gave us the image that we needed—a nonviolent equivalent of ‘blood’—and it was these images at the top of the news around the country that finally put the issue into the national spotlight and led to the protection of hundreds of thousands of hectares of tropical rain forests as World Heritage national parks.”

Thanks to John’s tireless efforts, large areas of forest have been protected also in Papua New Guinea, Ecuador, and India. When he started the Rainforest Information Centre in Australia in 1981, it was the first organization in the world to declare rain forest protection as its primary mission. The US Rainforest Action Network was the second such organization, and he has started many similar organizations in different parts of the world since. He has worked to provide sustainable development projects for indigenous forest dwellers tied to the protection of their forests.

Knowing how desperately important it is to reach the minds and hearts of as many people as possible, John began to take his “road show” from country to country, showing the films he has worked on, making CDs of his songs, and giving talks. He is now deeply involved in helping people to understand the importance of climate change. In my mind he is one of the greatest heroes alive today. His efforts have saved hundreds of thousands of hectares of forest.

At about the same time as John began his work in Australia, another defender of trees was tackling the shocking deforestation in Kenya. Professor Wangari Muta Maathai—what an extraordinary woman: dynamic, inspirational, and enormously courageous. She was born in a small village in Kenya, got a scholarship to study in the United States, and was the first woman from East Africa to get a PhD. She became involved with environmental and women’s issues on her return to Kenya, and in the mid-1970s, which is when I first met her in Kenya, she planted her first tree nursery. This led to her famous Green Belt Movement to combat deforestation, the water crisis, desertification, and rural hunger.

She began traveling around the country and encouraging rural women to plant indigenous trees from seeds they collected in the forest. She gave workshops on the importance of protecting and restoring watersheds and riverbanks. She found funds to give the women a very tiny stipend for each seedling that was planted out, and even managed to give a little money to husbands or sons who could read and keep accurate accounts. In effect she was using tree planting as a means for improving livelihoods and self-determination for women, one of her main issues.

In 1998 the government tried to take over an area of public forestland, which they planned to give to their supporters to develop. Wangari was outraged. She organized a group of supporters to go there and plant trees. When she arrived with a few members of parliament and some media, she found the area closely guarded by a group of men, who attacked them. Wangari, several dignitaries, and members of the media were injured. Fortunately Wangari’s supporters filmed the event, and the TV coverage triggered international outrage. Eventually the international investors, mostly from the United Kingdom and the United States, pulled out, leaving Wangari and her supporters the victors.

Wangari Muta Maathai (1940–2011), founder of the famous Green Belt Movement. Despite being beaten and arrested for her efforts to combat deforestation in Kenya, she never gave up. Eventually her movement led to the planting of hundreds of thousands of trees around urban areas in many parts of Africa. (CREDIT: JEFF HOROWITZ)

Wangari’s programs became ever more successful, and eventually, with funding from UNEP (the United Nations Environment Programme), she was able to establish the Green Belt Movement throughout Africa. People came to Nairobi from fifteen different countries to find out how they could start similar initiatives. Thus was the Pan African Green Belt Network born.

Wangari never gave up—not when the government closed down some of her programs, nor when, at least twice, she was beaten and arrested. It only made her more determined. For her work she received countless invitations to speak at international conferences, where she and I often met. And she was given many prizes and awards, culminating in the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004. During her lifetime thirty to forty million trees were planted in Kenya alone. The forests lost a true defender in 2011 when she died from cancer.

Just recently I met another outstanding defender of the forest, Chief Almir of the Surui people, who dared to stand up to illegal loggers in Brazil. As a result there is a price on his head. He is back in Brazil now, but for a while he left the country and had to carry on his fight from outside, speaking movingly and eloquently at international conferences.

It is the same in India—the renowned environmental activist Vandana Shiva wrote, “Every forest area has become a war zone. Every tribal is defined a ‘Maoist’ by a militarised corporate state appropriating the land and natural resources of the tribals. And every defender of the rights of the forest and forest dwellers is being treated as a criminal.”

Mike Fay, like Sunderlal Bahuguna in India, decided to raise awareness by walking. As a result of his walk across Congo and Gabon, which I mentioned in chapter 4, some wonderful forests have received protection. He and Nick Nichols met with President Omar Bongo of Gabon and talked to him about the magic of the forest world in his country. They showed him film and slides taken by Nick, and Mike told me that President Bongo had been moved to tears—and, more importantly, was moved to create thirteen new national parks in the rich, unlogged forests of his country. He even withdrew some concessions already committed to logging companies.

And after my visit to the pristine forests of the Goualougo Triangle, Mike and I were able to meet with President Denis Sassou-Nguesso of the Republic of the Congo to seek protection for the “Last Eden.” Our mission was successful, and as a result those trees that so inspired me have a chance to remain standing, perhaps for hundreds of years to come.

Of course, much money is needed to create an infrastructure that will enable these parks to be properly protected. And there is always the danger that another president might overturn the legislation. It is the same everywhere: even when forests are protected by law, economic interests often take precedence over conservation interests—in many of America’s great national parks, for example, mining and petroleum companies have been permitted to carry out their destructive operations.

My friend and National Geographic explorer Mike Fay has raised awareness and helped protect forests by undertaking marathon treks through the world’s most precious and endangered forests. Here Mike is crossing the Goualougo swamps with Pygmy guides in 1999. The photographer, Michael (Nick) Nichols, told me that Mike confiscated the shotgun days before from a poaching camp but the men in the team were so proud of the weapon that they refused to destroy it until they finally grew tired of carrying it. (CREDIT: COURTESY MICHAEL NICHOLS, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY)

Fortunately, there are a growing number of people in governments and NGOs around the globe working on introducing new legislation to better protect our forests and the indigenous people living in them. On several occasions I have lobbied on Capitol Hill and written letters in support of Save America’s Forests.

Best Forestry Practices

There is no doubt that it is desperately important to fight for the protection of old-growth forests. And it would be wonderful if we could save them all. But as, in the short term, this will not happen, it is necessary that we also push hard for the best forestry practices within the timber companies themselves. Many foresters I have met care deeply about sustainable logging and are as shocked by clear-cutting as we are. Sometimes this is only to ensure the continuation of their own industry, but a great many have a true respect for the forest itself. Unfortunately the extraction of timber today involves huge sums of money and there are many opportunities for corrupt politicians to make tidy sums on the side.

About fifteen years ago I organized a private meeting with the heads of several of the biggest European timber companies to discuss, among other things, their “code of conduct.” This specifies that a given section of forest can be logged only every twenty or thirty years, and then only trees of a certain size may be felled, with a strict limit on how many can be removed from a given area. They told me of one problem they were facing: government officials in Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo) would not allow the loggers to follow the code—they demanded that smaller trees be felled, and closer together, so that there would be more timber and more money. (One good outcome of that meeting was that these big companies agreed to add rules relating to the protection of endangered species to their “code.”)

Sustainable logging is one thing—but is it possible both to protect the soul of a forest and also to extract timber? One forest in British Columbia has been logged for some forty years and still retains much of the essence of a wild forest. Aptly named “Wildwood,” it was managed by an inspirational forester, Merve Wilkinson, until his death in 2011. As a young man he had borrowed money to buy the land in order to save it from developers. He had refused to construct paved roads, and felled trees were often dragged out by horses to the little mill that he had constructed on his land.

I was thrilled to meet Merve when I was visiting British Columbia about ten years ago. We walked through the forest on the dirt trails, and he explained that he knew all the bigger trees individually and never felled one until it was just past its prime. He used only natural methods to control tree diseases, he told me. “And,” he said, “there are more species of mammals and birds today than there were when I first started.”

He had never felled the ancient trees in his forest, and they still stood, reaching way up into the sky, the guardians. That was why, I believe, Wildwood, although it had been logged for years, retained that sense of timelessness that is, for me, one of the most important attributes of a forest.

Merve’s modest logging operations made quite enough money for his unassuming way of life, and for years he provided many people with jobs. And he passed his knowledge on—forestry students came from all over the world to learn about his successful and sustainable methods. Except students from the nearby university, for whom Wildwood was forbidden territory—the university received a good deal of funding from the timber industry and forbade their students to attend Merve’s workshops.

It is difficult to imagine that the timber industry as a whole, in today’s cutthroat world, would adopt Merve’s way of doing things, but as more and more forests are maintained on private land, it becomes an attractive possibility.

Even a petroleum company can work in a forest in an environmentally sustainable way. In the early 1990s I had extensive dealings with Conoco—when it was still a subsidiary of DuPont. Back then my friend Max Pitcher was vice president for exploration at Conoco—meaning he was in charge of finding new places to exploit. Max flew me in a small plane over the forest to show me how different companies worked. We flew over the whole of the Conoco concession near Pointe-Noire in Congo-Brazzaville, and Max explained that seismic exploration does not have to be conducted in straight lines.

He showed me a grove of trees, sacred to the local people, that had been directly in the path of the Conoco exploration team. They had gone around and not through the grove. But the seismic lines were not visible—the Conoco teams, back then, walked through the forest and had equipment dropped from helicopters so that bulldozers were not necessary. If they needed to make a temporary road, Max told me, they used roll-out “carpets” of logs so that the soil would be less impacted, and they removed the carpet afterward and even had botanists to study the vegetation before disturbing the soil and to replant it afterward.

Of course, if a commercially viable oil deposit had been found, a proper road would have been constructed. We spent a lot of time discussing how an oil well could serve to protect all the forest in the area around it and provide benefits to the people. Conoco did not find a commercially useful oil deposit, so we could never put our plan into action. But they did leave a team and some equipment behind when they left to build our Tchimpounga Sanctuary for the infant chimpanzees we were caring for who had been orphaned by the bushmeat trade.

We Need Our Forests

One tool that can be helpful to those fighting to save the forests is the fact that we really do need our forests. They provide us with clean water, protect the watershed, and prevent erosion. They also provide food and medicinal plants, and support a very wide range of different animals and plant species, thus protecting biodiversity. Moreover, forests are often referred to as the “lungs of the world,” as they take in CO2 from the air around them and release oxygen. The CO2 is stored not only in the leaves of the trees but also in forest soils, especially peat soils.

All of these benefits are referred to, in conservation and development circles, as “services” provided by the forests. This means, of course, “services to the ecosystem,” but people tend to think of this as services to people, and this always angers me—forests are not there to “serve” us. Rather we need to be wise enough to understand how they work and gratefully accept the benefits they offer. However, in this greedy, materialistic world it is useful to be able to point out that it makes more economic sense to protect rather than to destroy the trees—in other words, to assign a monetary value to living trees, particularly those in an intact forest.

My first intimation that this was possible was during one of my visits to Costa Rica, when I learned about the Payment for Environmental Services, a program launched by the farsighted government in 1979. Under this scheme, payments were made to owners of forests and forest plantations in recognition of the valuable role played by these forests in maintaining clean air and pure water in the country.

In 2005 the British government commissioned the most comprehensive review ever carried out of the economics of climate change. I happened to be at the conference in Paris when the principal investigator, Sir Nicholas Stern, presented the conclusions of the countless scientists and economists involved. And I still remember how thrilled I was to hear him saying that the cheapest and most efficient way of slowing down global warming was to save and restore our forests.

For a very long time I had been trying to think of a way to convince governments and villagers that it was in their best interests to preserve their forests. Ecotourism, while it would provide long-term economic benefits and was an exciting prospect for villagers, could not hope to provide the kind of money that governments received in return for handing out forest concessions for logging and for mining, oil, and gas operations. But if the developed countries, in an effort to compensate for their ever-increasing levels of greenhouse-gas emissions, would agree to put monies into the protection of “carbon sinks,” as forests have been described, this might be the answer.

By this time scientists around the world were working on ways to be able to estimate, quite precisely, the amount of CO2 sequestered in different kinds of forests and forest soils. From the start it was clear that tropical forests, along with the great boreal forests of the Northern Hemisphere—known as taiga in northernmost parts—play the most important role in this respect. The boreal covers most of inland Canada and Alaska, most of Sweden, Russia, inland Norway, and northern Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Japan. These vast and wonderful forests store huge amounts of carbon, especially in their rich peat soils—more, it is estimated, than that which is stored in the remaining tropical and temperate forests combined, and second only to that stored in the oceans of the world.

Like the tropical forests, the boreal forests are increasingly being logged, and this is obviously having a big effect on the production of greenhouse gases. The most recent estimates suggest that deforestation and forest degradation account for about 10 percent of global CO2 emissions—about the same as the transport sector.

Thus it really was important to create financial incentives for governments and villagers to preserve the remaining forests and restore trees to cleared or degraded land. Lengthy deliberations in many countries resulted in a UN program—Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, or REDD—to compensate governments of the forested nations that protected their forests. Initially, this concept was flawed, since it was almost impossible to monitor its effectiveness. A government, or village leadership, could accept money to protect their forest but continue to cut down the trees undetected. Nonetheless, gradually new technology was making it possible, in cooperation with DigitalGlobe, Google Earth, and Esri, to monitor the situation from space using satellite imagery.

Another criticism of REDD was that it showed a lack of concern for the welfare of villagers: if they were suddenly deprived of their livelihood—not allowed to cut down trees for charcoal or make new clearings to grow food for their families, for example—they would suffer. Moreover, tree plantations might be introduced, and although these might sequester CO2, they lead to loss of biodiversity.

So a new version of this program, spearheaded by the Norwegian government with support from Germany, Finland, and the United Kingdom, was created—REDD+. This improved version emphasized that in addition to conserving the forest per se in order to sequester CO2, it was also important to alleviate poverty, engage local communities in forest management, and conserve biodiversity. I was immediately enthusiastic, for our JGI TACARE program, which has been so successful, was based on exactly this kind of holistic vision.

Tanzania was one of a few countries selected for piloting REDD+ programs—and JGI was successful in acquiring a grant from the Norwegian government to work on one of these programs. Already we had funding from USAID for our TACARE program, initially to work in the degraded land around Gombe and subsequently to expand south into the Gombe-Masito-Ugalla Ecosystem. And now this new grant has enabled us to work with villagers to determine how we can best protect still-intact forests.

It is very exciting, for not only does it enable us to help the villagers living around the forests to have better lives, but it also helps us protect the chimpanzees that live there, as well as their habitat. The total area covered by our various projects is 4,633 square miles of protected forest and degraded forestland, where villagers had previously been not only farming but also practicing various harmful activities, such as making charcoal and harvesting honey by smoking out the bees, causing many forest fires. The forests are home to approximately 1,100 chimpanzees.

JGI is working in a total of fifty-two villages (which involves around 350,000 people). In each village we have trained forest monitors, selected by the village governments to patrol their forests. With the aid of new Android smartphones and tablets and an app called Open Data Kit, the monitors can accurately and instantaneously record the coordinates, descriptions, and pictures of forest fires, any tree felled illegally, or houses being built in protected areas. The important thing is that these forest monitors have been empowered—it is they who have selected what should be recorded, based on their indigenous know-how. They have chosen twenty-two different types of human activity that they believe can be threatening to the forest. And there are signs of thirty species of animals that they monitor.

Of course they note every time they see or hear a chimpanzee, or see a chimpanzee nest. This information, collected in areas near settlements, nicely complements the survey data that are collected in more remote forests by JGI and other scientists. It is in this way that we know that there are more chimpanzees outside than within protected forest areas—vital information for us as we devise plans, along with the villagers, to protect these endangered apes.

All this information is collected in a standardized way and is sent immediately to Google Cloud Storage, from where JGI and partners can download it for analysis, and to a live map on the web that is automatically updated and can easily be accessed by average citizens. The program is changing lives. The forest monitors are very proud of their work, and it increases their standing in the village. They are helping to make accurate maps of village land, recording the sacred sites, including sacred trees. And they are providing invaluable information, not only for science but to help the village leaders. JGI has a similar community-based monitoring program in Uganda and is in the process of designing a similar, scaled-up initiative with partners in the eastern part of the DRC.

If such initiatives can be developed around the world, especially where there are forests rich in biodiversity, then indeed we can have hope for the future. Hope that we can slow down climate change while the global community works out new ways to live in harmony with nature. Hope that our children’s children will know and marvel at the amazing diversity of life in the forests of the world.

Spiritual Value of Forests

Let us never forget that forests are beautiful in their own right. They have, for me, a spiritual value that makes them the most enchanted places on earth.

I want to share something that was one of my inspirational stories for my book Reason for Hope. It happened when I was walking along a trail through a glorious old-growth forest on the slopes of Mount Hood in Oregon. Suddenly, from the trail, I saw an amazing tree. It had been in a forest fire—about a hundred years ago, apparently—and only some forty feet of the trunk remained. I walked over to it and found it was completely hollow. I entered through an opening, almost like a small door, into a chapel pointed at the top.

The remaining outer shell of the tree, straight and tapering as the spire of a church, directed my eyes up and up, through the surrounding green of the forest, to the sky high above. I stood there, awed and humbled, and sent up a prayer for the survival of the remaining forests of the world.

I was with Chitcus, my Native American “spirit brother,” and a small group of Roots & Shoots children. I wanted to share my experience, and as the tree only held six people at a time, we held several ceremonies, during each of which I stood inside the tree with four children at a time. We faced one another, holding hands, and gazed upward to pray for the forests while Chitcus knelt in the middle and chanted an Indian blessing and made smoke from the sacred kishwoof root, which seemed to carry our prayers up and up and up and out into the blue playground of the clouds.

It was an extraordinarily moving and significant experience, and now, when things seem particularly grim, I relive that sacred memory and somehow find the strength to go on.