For information about unipolar depression, see my book The Natural Medicine Guide to Depression.

For information about unipolar depression, see my book The Natural Medicine Guide to Depression.

The often outrageous, flamboyant behavior associated with the manic pole of bipolar disorder has garnered both media attention and public fascination, but many people remain unaware of the painful, debilitating, and devastating aspects of the illness—on both ends of the mood spectrum

While a stressful event may trigger an episode, often the mood swings of bipolar disorder are inexplicable, bearing no apparent relation to what is happening in a person's life. Far beyond happy or sad moods, the condition is often agonizing and even life threatening. It wreaks havoc in careers, relationships, lives.

The medical and psychiatric professions classify bipolar disorder as a mental illness, and more specifically, as a mood disorder, or affective disorder. The psychiatric and medical professions regard bipolar disorder as a biological brain condition, which has a genetic basis and involves disturbed brain chemistry. Formerly known as manic-depression, it is characterized by periods of depression and mania, with wide variation in the length, frequency, severity, and fluctuation of these periods. Each episode can last days or months, and there may or may not be intervals of normal mood states between episodes. When there are such intervals, they can extend to days, months, or even many years.

Mania is characterized by an elevated, expansive, or irritable and angry mood with increased activity and energy; thought and speech that is more rapid than usual; reduced need for sleep; and grandiosity, distractibility, impulsiveness, inflated self-esteem, poor judgment, and/or recklessness, as in questionable sexual behavior and lavish spending sprees. In extreme episodes, delusions or hallucinations can occur.

Episodes of depression are characterized by persistent sadness or a feeling of flatness, pessimism, hopelessness, significantly reduced interest or pleasure, significant change in weight or appetite, insomnia or oversleeping, feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, problems thinking, concentrating, or making decisions, lethargy or restlessness and agitation, lack of energy, and/or recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. Delusions, and less often, hallucinations, can occur in depressive episodes as well as in manic.

While the name “bipolar disorder” reflects two distinct mood poles, the separation of mania and depression in this way is misleading in regard to what many people who suffer from the disorder actually experience, which is often an overlapping, mixed mood state. For this reason, Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, an authority on the disorder and a person who suffered from it from the age of 17, prefers the former name, “manic-depression,” as more accurately descriptive. “This polarization of two clinical states flies in the face of everything that we know about the cauldronous, fluctuating nature of manic-depressive illness; it ignores the question of whether mania is, ultimately, simply an extreme form of depression; and it minimizes the importance of mixed manic-and-depressive states, conditions that are common …”9

Bipolar disorder tends to run in families and usually manifests in late adolescence or early adulthood, but onset can also occur during preteen and later adult years. The peak age of onset is the mid-twenties,10 although that average may be dropping as more young children are developing the disorder (see “Children/Teens and Bipolar Disorder,” which follows). While there is no one pattern of progression in bipolar disorder, when untreated, it tends over time to escalate both in frequency and severity of episodes.

Unfortunately, only one in three people with a major mood disorder seeks help.11 Many people are not aware that they are suffering from bipolar disorder and so do not seek treatment. Even if they do, they may not get a proper diagnosis. There is no test for bipolar disorder, and diagnosis is based largely on family history and the patient's pattern of mood swings. It is not unusual for people to endure the emotional roller coaster of bipolar disorder for a decade or more (the average is eight years between onset and diagnosis12) before a particularly bad episode finally results in a diagnosis and subsequent treatment. Sadly, suicide claims many people before they get the help they need.

Bipolar disorder can be a corollary of other medical conditions such as an underactive thyroid (see chapter 2), and there is a comorbidity factor with substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder.13 Comorbidity means that two disorders exist together. In the case of substance abuse, more than 60 percent of people with bipolar disorder abuse drugs or alcohol.14 Though the motivation may be self-medication to numb the pain of depression or calm the agitation of mania, in the case of alcohol, and to increase or induce the high of mania or attempt to lift depression, in the case of stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines, the combination of bipolar disorder and substance abuse worsens the outcome of the illness. Those who abuse substances tend to have the irritable and paranoid, rather than the elated, type of mania, are more at risk for relapse, are more at risk for lithium not working for them, and experience 50 percent more hospitalizations.15 Alcohol abuse also increases the likelihood of suicide, as alcohol features in 30 percent of all suicides.16

Nearly one in five people with bipolar disorder commit suicide.17 The growing number of children with bipolar disorder may be a factor in the rising suicide rate among America's young. In 2007, the CDC reported a dramatic increase in teen suicide from 2003 to 2004 (the last year for which data are available): up 76 percent in girls aged ten to fourteen, up 32 percent in girls aged fifteen to nineteen, and up 9 percent in boys aged fifteen to nineteen.18 For youth between the ages of 15 and 24, suicide is now the third leading cause of death. For college students, it is the second leading cause.19 Note that in almost half of those with bipolar disorder, onset came before they were 21 years old. As the cycling of moods in bipolar children tends to be ultra-rapid, with several mood changes in the space of a day, you can imagine how difficult that makes life for these children.

The high incidence of suicide among people with bipolar disorder makes it important for both those with the condition and their family and friends to be aware of the warning signs of suicide. Being forewarned may enable you to prevent this tragedy from happening if the signs begin to manifest. A family history of suicide or a previous suicide attempt places one at increased risk of suicide. In addition, the warning signs of suicide are:21

If you think that you or someone you know is in danger of attempting suicide, call your doctor or a suicide hotline or get help from another qualified source. Know that there is help and, though it may be difficult to ask for it, a life may depend upon it.

The numerous variations in the manifestation of bipolar disorder are reflected in the complicated array of psychiatric labels that fall under the heading of bipolar disorder. Further, the clinical status of a given episode can be specified as mild, moderate, or severe, with or without psychotic features, chronic, with rapid cycling, with catatonic features, or with melancholic features, among other classifications.22

The following are subcategories of the bipolar psychiatric label, according to the diagnostic bible of the psychiatric profession, the DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision).23 A holistic medical approach does not use such diagnoses to determine the appropriate treatment course, focusing instead on the particular manifestations and underlying imbalances in the individual patient. Many people receive these labels, however, so it's helpful to know to what they refer.

In simple terms, Bipolar Disorder I ranges the whole spectrum from severe depression to mania or mixed mania, with an emphasis on the manic end. In DSM-IV terms, diagnosis requires that the person has had one or more manic episodes or mixed episodes (see list), and often has had one or more major depressive episodes in addition. The average age of onset in men and women alike is 20 years old for this form of bipolar disorder.24

A manic episode is defined as an abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood persisting for at least one week (less if hospitalization ensues) and accompanied by at least three (four in the case of irritability only) of the following symptoms:25

The mood alteration must also be severe enough to impair the person's functioning professionally, socially, or in relationships with others. The mania may also have psychotic features and/or require hospitalization. Paranoia may be part of the symptom picture.

A major depressive episode is defined as depressed mood or loss of interest lasting at least two weeks and accompanied by at least four of the following symptoms:26

When only major depressive episodes occur, without episodes of mania, the person is said to suffer from unipolar depression, also known as clinical depression.

For information about unipolar depression, see my book The Natural Medicine Guide to Depression.

For information about unipolar depression, see my book The Natural Medicine Guide to Depression.

Research suggests that this form of bipolar is more common than Bipolar Disorder I in general, and it appears to be more common among women. Bipolar Disorder II favors the depressive end of the mood spectrum, ranging from severe depression to hypomania (mild mania). Interestingly, men tend to experience as many or more hypomanic episodes as major depressive episodes, while for women the latter are more prevalent.27 For a diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder II, according to the DSM-IV, the person must have had one or more major depressive episodes and one or more hypomanic episodes, never had a manic episode or a mixed episode, and had the disturbance impair, or produce distress in, the person's professional, social, or other important functioning.28

Hypomania is the same as mania, except the altered mood must last at least four days (rather than a week) and does not impair professional or social functioning, require hospitalization, or have psychotic features.

Cyclothymia ranges from mild or moderate depression (dysthymia) to hypomania. According to DSM-IV criteria for the diagnosis of cyclothymic disorder, the person must have had numerous periods of both hypomanic and depressive symptoms over at least two years, with no more than two months at a time free of symptoms, and with no major depressive episode, manic episode, or mixed episode during the first two years.

A mixed episode, also called a mixed state, mixed affective state, mixed mania, or dysphoric mania, is a manifestation of bipolar disorder in which depression and mania exist together in one episode. The DSM-IV defines it as a period of at least a week during which the person fits the picture for both a manic episode and a major depressive episode, with agitation, insomnia, psychotic features, and suicidal ideation often present.29

—KAY REDFIELD JAMISON, PhD, on mixed episodes

This refers to a pattern that can occur in Bipolar I and Bipolar II. In rapid cycling, the moods are the same as defined, but they change more frequently, with four or more episodes in the space of a year, marked by a switch to the other pole or a period of nonepisodic mood (neither mania nor depression). Ultra-rapid cycling, a relatively new term, refers to switching that happens in the space of a day or even from moment to moment.

While this disorder is listed under schizophrenia in the DSM-IV, it is defined as involving a major depressive, manic, or mixed episode in combination with two or more of the characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, catatonic or grossly disorganized behavior, or negative symptoms such as flat affect, lack of speech, or lack of volition. Schizoaffective disorder presents very much like bipolar disorder with psychotic features, the difference being that delusions and hallucinations in the latter case are part of the abnormal mood, while no such relationship exists in schizoaffective disorder.31

People with bipolar disorder are frequently diagnosed with schizophrenia and vice versa. Others receive a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as was true with several of the people featured in cases in this book. The schizoaffective category highlights the confusion in attempting to distinguish between the disorders.

—PATTY DUKE, actor and author of several books on manic-depression

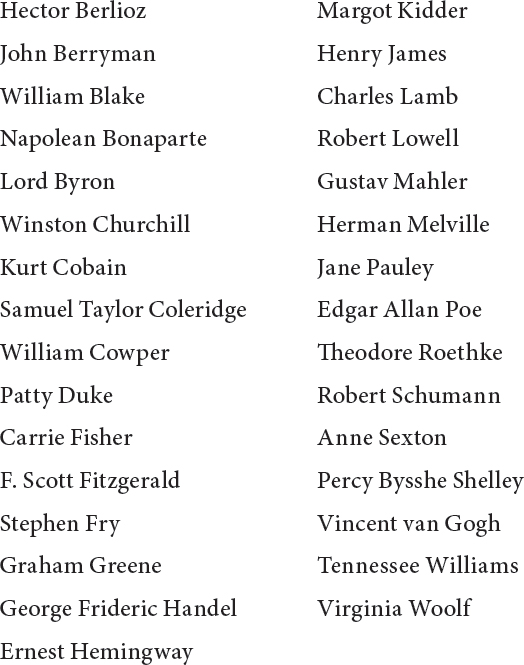

There is another side to bipolar disorder, and that is its link to creativity. Madness in general has long been paired with genius in the arts. Investigation reveals that there is some substance behind what some dismiss as a romantic notion. Many people with bipolar disorder report that their creative output increases significantly when they are hypomanic. Researchers have cited “sharpened and unusually creative thinking” and “increased productivity” as two of the criteria in the diagnosis of hypomania.33

As part of her investigation into the relationship between creativity and mood disorders, Dr. Jamison charted the works of composer Robert Schumann in relation to his bipolar episodes, and the results are significant. During the years in which he was severely depressed or attempted suicide, he produced no, or one to two, opuses. In 1840 and 1849, when he was hypomanic for the whole year, he composed 24 and 27 opuses, respectively.34

There seems to be a preponderance of the affliction in artists and writers throughout history who were known to have mood disorders of some kind. This perception is borne out by a review of studies investigating the actual percentages in comparison with the population at large. An analysis of seven studies found that the rate of manic-depression and cyclothymia among artists and writers is 10 to 20 times higher than the rate in the general population; the rate of depression is 8 to 10 times higher; and the suicide rate is as much as 18 times higher.35

It is not known why this is so. Does the artistic process promote madness, or are people suffering from mental illness temperamentally drawn to the arts? Whatever the reason for the greater incidence among the creative, it is important not to lose sight of the tragic aspect of the madness-genius equation, which can get lost in the romanticization of the artistic life. As Dr. Jamison observes, “No one is creative when paralytically depressed, psychotic, institutionalized, in restraints, or dead because of suicide.”36

The relationship between creativity and at least the milder form of mania makes treatment problematic for some people. The most common side effects that people on lithium report are “mental slowing” and “impaired concentration.”37 This is enough for some people to stop taking lithium. While avoiding the more debilitating form of mania may be an incentive for treatment compliance, hypomania may be a compelling state. As Dr. Jamison poses it, “Who would not want an illness that has among its symptoms elevated and expansive mood, inflated self-esteem, abundance of energy, less need for sleep, intensified sexuality, … sharpened and unusually creative thinking and increased productivity?”38

It may not be only the hypomanic aspect of bipolar disorder that has an effect on creativity, “but rather the flux and tensions between the different mood states,” explains psychiatrist and author Francis Mark Mondimore, MD. “Perhaps bipolar disorder stimulates creativity in part because its sufferers experience the world through the emotional prisms of its many and shifting moods … ”40

Mood disorders have plagued humankind for at least as long as recorded history, and likely from the beginning of human existence. Written accounts of mood disorders come to us from Egypt in the time of the pharaohs, 4,000 years ago.41 Writings by physicians in ancient Greece describe both melancholia (a term for depression) and mania. One in particular, Aretaeus of Cappadocia, writing in around AD 150, expressed an understanding of the interrelationship of the two, as in bipolar disorder: “In my opinion, melancholia is without any doubt the beginning and even part of the disorder called mania.”42

One way of explaining the presence of mood in the human spirit is to regard it as an evolutionary adaptation.43 A depression in mood, for example, pulls us back from engagement with life, which we may need to do at that moment to keep us safe or to give us time to gain a perspective, while mania gives us the wherewithal to act quickly. Psychiatrist and author Peter C. Whybrow, MD, suggests, “Perhaps mania and melancholia endure because they coexist with behaviors that serve a greater human purpose, attributes that have had survival value for the individual and thus, indirectly, are useful to society.”44

In ancient Greece, melancholy came to be considered an excess of black bile, one of the four “humors” of the body (blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm) believed to regulate health. According to humoral theory, as suggested by one physician, mania was the result of too much yellow bile that had turned into black bile as a consequence of too much heat.45 Black bile was considered the driving force in creativity, so melancholy gained a positive association with the creative temperament. By pointing out the many poets, artists, politicians, Greek heroes, and philosophers, including Plato and Socrates, who were of a melancholic nature, Aristotle perpetuated a positive view of the condition that continued for centuries.46

In the Middle Ages, mental illnesses came to be viewed as conditions to cure, with demonic possession or witchcraft their cause. During this period, priests delivered the exorcistic ministrations that were considered treatment.

Although the mania and depression of bipolar disorder was first described as one mental illness in 1854, by two French physicians, a full description did not appear until 1899 in a textbook by German physician Emil Kraepelin.47 He studied and documented bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses, providing the foundation for modern psychiatry, whose focus on diagnosis and classification comes from Dr. Kraepelin.48

The belief that psychological factors were the cause of mental illnesses arose from the work of Sigmund Freud and began to gain cachet in the American medical establishment in the 1920s.49 With the source of such illness firmly placed in the mind, parents (mostly mothers), early trauma, and psychological conflicts became the culprits behind manic-depression and schizophrenia. This orientation is largely responsible for the stigma that came to be attached to mental illness—that is, manic-depression is not a disease like any other, but a failing on the part of the individual or the individual's mother.

The advent of psychiatric drugs in the 1950s transformed the psychiatric field, shifting the focus of the causality of mental illness from psychological to biochemical, and turning the profession into a pharmaceutical industry. Gradually, the medical redefinition, with its focus on biology, permeated public consciousness, but the stigma attached to mental illness persists to a certain degree, although open discussion by celebrities suffering from the disorder has helped dispel some of the earlier judgments and misconceptions. Medically, the role of psychological factors in bipolar disorder is not entirely discounted, but the overwhelming emphasis in treatment is on drugs.

The current conventional medical view is that bipolar disorder is a brain disorder involving some kind of neurotransmitter malfunction. Neurotransmitters are the brain's chemical messengers that enable communication between cells. While there are many different kinds of neurotransmitters, the primary ones involved in the regulation of mood are serotonin, dopamine, epinephrine/norepinephrine, GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), and L-glutamate.

Contrary to popular belief, serotonin is not found only in the brain. In fact, only 5 percent of the body's supply is in the brain, with 95 percent distributed throughout the body and involved in many functions.50

Serotonin is distributed throughout the brain, where it is “the single largest brain system known.”51

In addition to influencing mood, serotonin is involved in regulation of sleep and pain, to name but a few of its numerous activities.

Dopamine has a role in controlling sex drive, memory retrieval, and muscles, as well as mood. One theory holds that dopamine may be operating to excess in severe mania and acute schizophrenia.52

GABA operates to stop excess nerve stimulation, thereby exerting a calming effect on the brain. Two important functions of L-glutamate involve memory and the curbing of chronic stress response and excess secretion of the adrenal “stress” hormone cortisol.

—STEPHAN SZABO, on his experience of mania

Epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and norepinephrine are hormones produced by the adrenal gland. Epinephrine is involved in the stress response and the physiology of fear and anxiety; an excess has been implicated in some anxiety disorders. Norepinephrine is similar to epinephrine and is the form of adrenaline found in the brain;54 interference with norepinephrine metabolism at certain brain sites has been linked to affective disorders.55

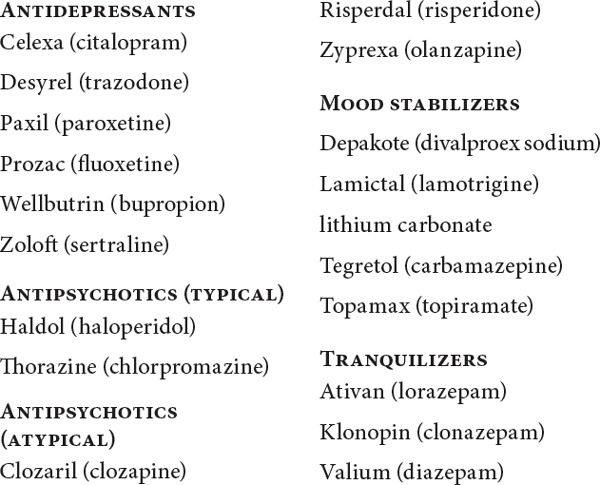

Neurotransmitters are the targets of psychiatric drugs used in the treatment of mental illness. In the case of bipolar disorder, these drugs fall into the categories of mood stabilizers (lithium and anticonvulsant drugs), antipsychotics, antidepressants, and tranquilizers. While the effects and side effects of all could be enumerated at length, the following brief discussion focuses on a few of the drugs in the first three categories typically used in bipolar disorder.

Although the application of the chemical lithium (with the addition of the compound carbonate it becomes lithium salts) in bipolar disorder was discovered in the late 1940s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not approve it for preventive use in bipolar disorder until 1974. After that, it became standard drug treatment. Lithium works by affecting neurotransmitters in some way to slow the electrical transmission of brain cells, which impedes the person's ability to feel or react.

“Lithium flattens emotions by blunting or constricting the range of feeling, resulting in varying degrees of apathy and indifference,” state Peter R. Breggin, MD, and David Cohen, PhD, authors of Your Drug May Be Your Problem. “It also slows down the thinking processes. This drug-induced mental and emotional sluggishness should be considered lithium's primary ‘therapeutic’ effect.”56

There is no doubt that since its advent, lithium has saved, and continues to save, many lives. At the same time, there are a number of reasons to consider alternatives. Lithium produces no effect in 30 percent of people with bipolar disorder, and others cannot tolerate the side effects.57 A summary of data on adverse drug effects found that 32.5 percent of patients on lithium experienced memory impairment, and 22.8 percent (in some studies the rate was almost 40 percent) experienced confusion and disorientation.58 For some patients, discontinuing lithium treatment does not lead to a restoration of full mental function; in other words, effects can be permanent. In addition, lithium can cause hypothyroidism, among other conditions. Withdrawal from the drug can trigger a manic episode.

Even a recent article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry on the use of lithium for bipolar disorder concluded: “Lithium is the only agent currently approved for the treatment of both acute episodes of mania and maintenance therapy; however, it is associated with a relatively poor response rate, high relapse rate, and less-than-optimal side effect profile.”59

Like lithium, anticonvulsants are used as mood stabilizers. Perhaps the most well known in the treatment of bipolar disorder is Depakote, which was originally used for epilepsy. It is not known how these drugs work to control mania or reduce mood swings. Known side effects of Depakote are sedation, confusion, impairment of mental function, tremors, walking problems, and even delirium.60

Antipsychotics such as Thorazine have a history of use in mental illness, including bipolar disorder. Also known as neuroleptics (the literal translation is “taking hold of the nerves”), and formerly referred to as major tranquilizers, these drugs blunt a range of brain activities and produce “apathy, indifference, emotional blandness, conformity, and submissiveness, as well as a reduction in all verbalizations, including complaints or protests,” according to Drs. Breggin and Cohen. “It is no exaggeration to call this effect a chemical lobotomy,” they state.61

The phrase “the Thorazine shuffle” came into usage in mental hospitals in the early days of Thorazine prescription, referring to the characteristic way of moving as a result of the numbing physical, mental, and emotional effects of this drug.

Although antipsychotics are ostensibly given to control delusions and hallucinations, they actually have no specific effects on either, say Drs. Breggin and Cohen, and their side effects are daunting. While so-called atypical antipsychotics, such as Zyprexa, are enjoying cachet now over Thorazine and other typical antipsychotics because their side effects are regarded as less onerous, Drs. Breggin and Cohen strongly state: “All neuroleptics produce an enormous variety of potentially severe and disabling neurological impairments at extraordinarily high rates of occurrence; they are among the most toxic agents ever administered to people.”62

Meanwhile, more and more children are being diagnosed with bipolar disorder and put on antipsychotics.

Antidepressants target serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, which are monoamines (they are derived from amino acids) colloquially known as the “feel good” neurotransmitters.63 The antidepressant drugs Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, Luvox, and Effexor are what is known as SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. They block the natural reabsorption of serotonin by brain cells, which boosts the level of available serotonin. SSRIs are relatively new arrivals on the antidepressant scene; Prozac was introduced to the market in 1987.

Earlier categories of antidepressant drugs are tricyclics and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Tricyclics such as Elavil, Adapin, and Endep inhibit serotonin reuptake, but block norepinephrine reuptake as well; thus, they are less selective than SSRIs. MAOIs such as Nardil and Parnate act by inhibiting a certain MAO enzyme that breaks down monoamines; the outcome is more available neurotransmitters.64

The theory that neurotransmitter deficiency causes depression is known as the “biogenic amine” hypothesis. While the model recognizes that imbalances in amino acids (neurotransmitter precursors) produce the deficiency, amino acid supplementation is not the conventional medical solution. “These amino acids have proven to be effective natural antidepressants,” states Michael T. Murray, ND, author of Natural Alternatives to Prozac.65 Despite this, the focus of conventional treatment is expensive pharmaceuticals. “Perhaps the main reason [the biogenic amine] model is so popular is that it is a better fit for drug therapy,” notes Dr. Murray.66

For more about amino acids, see chapters 5 and 6.

For more about amino acids, see chapters 5 and 6.

Contrary to popular belief, the newer, more expensive antidepressants—Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil—are no more effective than the older antidepressant drugs, according to a report issued by researchers for the U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.67

Despite their disturbing side effects and research showing that they do not work for a third of the people who take them, and do no better than placebos for another third,68 these drugs continue to be dispensed widely and to be regarded as the panacea for depression. This prescription flurry is extending to children now as well. With the growing number of children being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, more children are being put on antidepressants, despite the fact that Prozac and similar antidepressants are approved by the FDA only for use in patients over the age of 18.69

The adverse effects (euphemistically known as side effects) of antidepressants can range from uncomfortable to untenable, although some people who take the drugs experience no side effects. With Prozac, for example, adverse effects include nausea, headaches, anxiety and nervousness, insomnia, drowsiness, diarrhea, dry mouth, loss of appetite, sweating and tremor, and rash.70

Flattened or dulled feelings and sexual dysfunction are common effects of taking SSRIs. In addition, the anxiety and agitation induced by SSRIs can result in patients increasing their use of alcohol and other substances for calming purposes.71

More serious, there has been very little research on the long-term effects of taking SSRIs. It is known, however, that they can produce neurological disorders, and permanent brain damage is a danger.72

Of particular importance to people with bipolar disorder is the fact that antidepressants can not only trigger a manic episode, but can also accelerate the illness, plunging the person into more frequent mood changes and even rapid cycling.73

This is something that the psychiatric profession has known about since the 1950s. Both the older antidepressants and their newer relatives, the SSRIs, are linked to this phenomenon. Since more people are now taking antidepressants than ever before, this puts more people at risk. One study found that the mania or psychosis of 43 out of 533 patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital was connected to antidepressant use, and 70 percent of those patients were on Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil, or another SSRI.74

While this drug reaction does not occur in everyone with bipolar disorder, it is unknown who is at risk. Those who are aware that they have bipolar disorder can at least be forewarned that this is a possibility, but people who do not know that they have the condition and seek treatment for depression can suffer serious consequences. This is why it is so important for physicians, before prescribing antidepressants, to take full medical histories, including inquiring into a patient's past mood patterns and whether there is a history of mood disorders in the family.

In addition to the range of drugs cited, more drugs are often prescribed to counteract the side effects of the others. The result is that many people with bipolar disorder are on a kind of drug “cocktail,” a mixture of quite a few medications. Most face a lifetime of this because these drugs are not a cure, but only a means of controlling the symptoms, and often not well at that. There is no doubt that lithium and antidepressants save lives, but they do not address the underlying factors that cause or contribute to the condition, even the most fundamental factor of nutritional deficiencies that lead to an imbalance in amino acids and neurotransmitters. Investigation into these factors is rarely a feature in drug-based treatment.

Natural medicine is based on the knowledge that in order for comprehensive healing to occur, the factors causing or contributing to a disorder must be identified and addressed in each person. With this approach, it is possible for people to get off their drugs or reduce their dosages, and in so doing improve their present and future health. The next chapter explores the underlying factors that can play a role in bipolar disorder.