I believe in the power of relationships. For years I have carried in my wallet . . . a well-worn scrap of paper inscribed with Chinese characters pertaining to one’s age and phase in life. At 30, you are in your prime of life. At 50, you are said to know your destiny. At 60, you possess the wisdom of the “soft ear.”

—Ban Ki-moon, secretary-general of the UN

“Equal parts diplomat and advocate, civil servant and CEO, the Secretary-General is a symbol of United Nations ideals and a spokesman for the interests of the world’s peoples, in particular the poor and vulnerable among them.” This official UN description captures the sweeping responsibilities assigned to the world body’s chief executive officer and suggests the great challenges they bring. Choosing a new secretary-general is a major event, not only for the UN system but for its 193 member states and all the world’s peoples.

On October 13, 2006, the UN General Assembly selected a sixty-one-year-old South Korean, Ban Ki-moon, as the eighth secretary-general, to succeed Kofi Annan, whose two five-year terms had set precedents for international activism and public visibility. The new man attracted wide media attention. The secretary-general has sometimes been referred to as the world’s secular pope and carries heavy responsibilities in such vital and sensitive areas as peacemaking, human rights, and UN reform. Yet outside the diplomatic community, few had heard of Ban Ki-moon. No wonder people around the globe were asking, Who is this fellow?

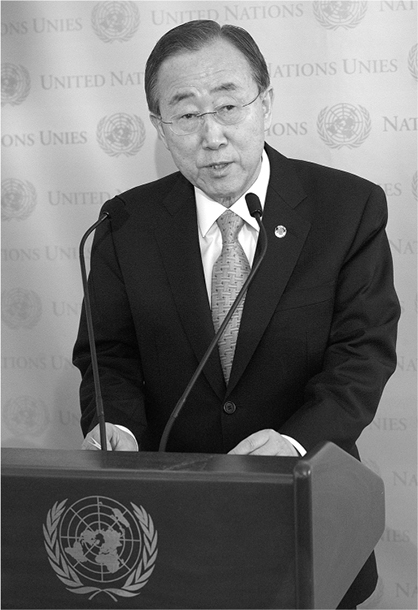

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon speaks at a press conference on the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, March 11, 2011. UN Photo / Evan Schneider.

Ban Ki-moon was born in a South Korean farming village in 1944 and grew up while his country was defending itself against aggression from the north—a war fought under US leadership with the official sanction of the UN. The young man’s life took a decisive turn in high school when he met his wife and won an essay contest sponsored by the Red Cross that led to a visit to the United States. He credits a brief meeting with President John F. Kennedy in Washington, DC, with helping him decide to pursue a career in diplomacy. Back in South Korea, Ban joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1970 and gradually moved up the career ladder, earning respect for his intense work ethic and his diplomatic skills. In 1974 he was posted to New York City as first secretary of the South Korean Permanent Observer Mission to the UN, and in 1991 he became director of the foreign ministry’s United Nations Division. Meanwhile, in 1980, he became director of Korea’s International Organizations and Treaties Bureau in Seoul. After two postings to the Korean embassy in Washington, DC, and more assignments in Korea and Austria, he became his country’s foreign minister in 2004. By then he had also earned a master’s degree in public administration at Harvard University’s prestigious Kennedy School of Government.

Ban Ki-moon declared his candidacy for secretary-general of the UN in February 2006 and launched a vigorous campaign for the position with strong support from his home government. Candidates for the top post at the UN have to work hard and strategically if they expect to win. Ban’s efforts got a huge boost when it became known that both China and the United States favored his candidacy. His chances were also aided by the unwritten agreement that the post of secretary-general should rotate among regions of the world. Accordingly, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, from Peru, served two terms (1982–91) and was followed by Boutros Boutros-Ghali, of Egypt, who served one term (1992–97), and Kofi Annan, a Ghanaian, who served two terms (1997–2006). Because Africa had contributed two consecutive secretaries-general, and Europe had produced several secretaries-general, ending with Kurt Waldheim (1972–81) of Austria, the post was expected to go next to Asia (which, in the UN system, includes the Arab states of the Middle East). Ban Ki-moon was therefore well positioned, but he faced competition from another Asian, Shashi Tharoor of India, an experienced UN staffer closely associated with Kofi Annan.

Once Ban and Tharoor had declared, the UN began the formal process of deciding on a winner. The procedure involves two UN bodies: the Security Council, which recommends a candidate, and the General Assembly, which ratifies the choice. The Security Council decides on the nomination at “private” meetings for which there is no public record except for brief communiqués from its president. In 2006, the fifteen members of the council held a series of straw polls that made Ban Ki-moon the favorite, with Tharoor second. Observers did note a surprisingly strong showing by Vaira Vike-Freiberga of Latvia, the only woman and the only non-Asian among the candidates, whose name was placed in two straw votes. When the final poll showed Ban Ki-moon as the nominee, the council passed his name to the General Assembly, and in the ensuing vote Ban was elected the eighth secretary-general. And five years later he was elected to a second term.

The position of the secretary-general is only briefly described in the UN Charter and has evolved over time. “In the Charter of the UN,” observed Richard Holbrooke, “the role of secretary-general is only described with a single phrase, that the UN will have a chief administrative officer. It doesn’t describe the authority of the secretary-general as the Constitution describes the powers for the president and Congress. It’s all been done, like the British constitution, by precedent and strong secretaries-general, of whom we’ve had two, Dag Hammarskjöld and Kofi Annan.”

Mark Malloch-Brown adds that the Charter “doesn’t envisage significant powers for the secretary-general in international relations.” Rather, he says, the internationally active secretaries-general have succeeded by “convincing genuinely important individuals, heads of government and so on, that they can be helpful.” Michael Sheehan, a former assistant secretary-general for peacekeeping, says that one of the secretary-general’s roles is to “tell the Security Council what it has to know, not what it wants to hear. So the Secretariat is not just a puppet on a string of the member states; it has a role, and there’s a dialogue between the Secretariat and the member states.” In this dialogue the secretary-general often deploys his status as an impartial and well-intentioned leader, lending his good offices to address international conflicts and issues. In other words, he has a bully pulpit, and he is expected to use it.

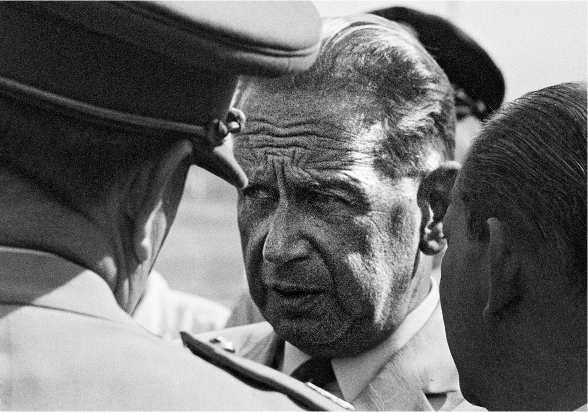

Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in Katanga, Republic of the Congo, August 14, 1960. UN Photo / HP.

The many responsibilities of the secretary-general make the post one of the most demanding imaginable. It requires intelligence and experience, certainly, but also drive, vision, and infinite tact and patience. The secretary-general must be able to communicate with the entire UN family as well as with all the nations of the world while overseeing a global array of programs and agencies. His daily activities range from attending sessions of the Security Council, General Assembly, and other UN bodies, to meetings with world leaders and government officials, to frequent travel around the globe. He greets world leaders when they arrive at the UN’s New York headquarters for the September opening of the General Assembly, and he hosts them at a special luncheon. He also chairs the UN System Chief Executives Board, routinely referred to as the CEB, which consists of the directors of all the world body’s funds, programs, and specialized agencies, who meet twice annually to coordinate their various activities throughout the UN system.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon meets with former secretary-general Kofi Annan in Geneva, March 4, 2008. UN Photo / Mark Garten.

Alongside all the specific and general duties, charges, and responsibilities, the secretary-general is responsible for overseeing the Secretariat, which is the UN’s chief executive arm. The Secretariat is headquartered in New York City, in the sleek modern building that rises dramatically beside the East River, but it also has offices in Addis Ababa, Bangkok, Beirut, Geneva, Nairobi, Rome, Santiago, and Vienna.

All told, the Secretariat has about forty-three thousand staff. In keeping with the letter and spirit of the Charter, which aimed to create an international civil service, member states agree not to exert improper influence on the Secretariat’s staff, and the staff, in turn, take an oath that they will be responsible solely to the United Nations and will not seek or take direction from any other authority. Chapter XV, Article 100, of the Charter states very clearly that “each Member of the United Nations undertakes to respect the exclusively international character of the responsibilities of the Secretary-General and the staff and not to seek to influence them in the discharge of their responsibilities.” Article 101 mandates that “the paramount consideration in the employment of the staff and in the determination of the conditions of service shall be the necessity of securing the highest standards of efficiency, competence, and integrity. Due regard shall be paid to the importance of recruiting the staff on as wide a geographical basis as possible.”

Kofi Annan is credited with advancing a series of administrative reforms in the Secretariat begun by his predecessor, Boutros Boutros-Ghali (the reforms are discussed in chapter 18). Annan encouraged development of a corporate culture aimed at making results, not efforts, the test of effectiveness. Ban Ki-moon is credited with continuing the reform efforts. His deputy, Jan Eliasson, observes that while the Secretariat’s staff quality may vary by individual, “there are extremely inspiring and great minds and true internationalists . . . it’s very high quality.” He notes that to be a good member of the staff, “you have to be both very realistic about the world as it is, you can’t live in the clouds, you have to know what is the situation and be very realistic about that. But you must never forget that we are unique in serving this organization.”

Former Canadian ambassador David Malone estimates that “40 percent of the Secretariat staff are movers and shakers and carry the full burden of action. About 30 percent do no harm and do no good, and about 30 percent spend their time making trouble. Which means that the 40 percent who get work done are fairly heroic, and they exist at all levels of the system.”

How to manage this far-flung staff has become an issue as the number of member states has grown, UN activities have increased, and local and regional crises have proliferated. A later chapter will address the broad issue of UN reform, which focuses heavily on improving administrative efficiency and accountability within the UN system. Here our main point is to see how the secretary-general can discharge his duty to oversee the Secretariat’s staff and ensure that they are carrying out his policies and the expressed wishes of the Security Council, General Assembly, and other UN bodies. Clearly, the secretary-general’s oversight implies a focus on coordination to ensure that the various offices and key personnel are pulling together, not in separate directions. He does this through his Team, which consists of the deputy secretary-general, the Senior Management Group, and special personal representatives, envoys, and advisers, with occasional assistance from volunteers known as Messengers of Peace and Goodwill Ambassadors.

Until recently the secretary-general was pretty much a one-man band. Then Kofi Annan decided that he needed to delegate more of his duties as secretary-general. His solution was to persuade the General Assembly in 1997 to create a new post, deputy secretary-general.

The deputy is in effect the UN’s chief operating officer, assisting the secretary-general in the management of his staff and the Secretariat, representing the UN at conferences and official functions, and chairing the Steering Committee on Reform and Management Policy. The deputy secretary-general is also charged with “elevating the profile and leadership of the United Nations in the economic and social spheres,” areas attracting increasing UN attention and resources.

Annan named a Canadian diplomat, Louise Fréchette, to the new position in 1998. She was succeeded in 2006 by Mark Malloch-Brown of the United Kingdom, former head of the UN Development Program (UNDP). In 2007, Ban Ki-moon selected Asha-Rose Migiro, a lawyer and a former foreign minister of Tanzania to the post. Jan Eliasson became deputy secretary-general in 2012. He is a former Swedish diplomat and foreign minister and an experienced member of the UN family. Eliasson was the first UN under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs (1992–94), a post that involved him deeply in social and economic development and gave him field experience in many troubled places, such as Somalia and Sudan.

“The secretary-general asked me to help out, to alleviate his burden because he has so much on his plate,” says Eliasson, who relishes his work and routinely works long hours. “The leadership team meet every day when they are in town, they are in constant contact. On weekdays, evenings, and almost every weekend we have video conferences.” Eliasson’s special concerns are the political section, which contains peacekeeping and political issues, human rights, and development. “These are my areas. I am not operational from the point of view that I micro-manage the department, but I am overseeing it and I try to live up to the formula that I myself had the honor of formulating: that there’s no peace without development and no development without peace. Today I would say there is no lasting peace without respect for human rights and the rule of law. In other words, these areas are connected, and we need to work for them at the same time.” His special position in the UN system enables him to “bring people around the table, put the issues in the center, and see them from the political and security aspect, the developmental aspect, and the human rights and rule of law aspect. That has proven very useful for me and I hope for my colleagues.”

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at a seminar with his special representatives, personal representatives, and envoys in Mont Pèlerin, Switzerland, March 2, 2014. UN Photo / Eskinder Debebe.

The deputy secretary-general is a member of the Senior Management Group (SMG), described as “a high-level body, chaired by the Secretary-General, which brings together leaders of United Nations departments, offices, funds, and programmes.” In January 2014 the SMG had forty-one members plus the secretary-general. Skimming the membership list alphabetically by personal name, we see Valerie Amos, Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator; Jeffrey Feltman, Department of Political Affairs; Tegegnework Gettu, General Assembly Affairs and Conference Management; Angela Kane, Disarmament; Hervé Ladsous, Peacekeeping Operations; Wu Hongbo, Economic and Social Affairs; and Leila Zerrougui, Children and Armed Conflict. We could just as well have cited the Special Adviser on Africa, the Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the Special Adviser on Change Implementation, or the Secretary-General of the UN Conference on Trade and Development—and still we would not have covered the entire SMG. Even this quick scan shows, however, that these directors, managers, and senior advisers address an extraordinarily wide range of issues, covering all parts of the globe. It also shows, through the variety of personal names, that this is truly an international staff.

Like any high-powered CEO, the secretary-general has to deal with all kinds of issues, even those with which he may have little direct experience or expertise. And so the secretary-general does what you might expect: he finds people he trusts who can act as his eyes, ears, and representative for the region, issue, or conflict at hand. In January 2014, for Africa alone, Ban Ki-moon had designated some twenty-one men and women as his representatives. The number of representatives and their names change continually to accommodate the ever-changing shape of the world, but a brief list will give a flavor of the mix: in early 2014 they included the Special Representative of the Secretary-General to the African Union; the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Côte d’Ivoire and Head of UNOCI (UN Operations in Côte d’Ivoire); the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General and Mediator in the Border Dispute between Equatorial Guinea and Gabon; the Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of UNSMIL (UN Support Mission in Libya); and the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Sahel. These various appointees often have rather open-ended briefs, in keeping with the fluid nature of the situations in which they operate.

Unlike the personal representatives of the secretary-general and the members of the SMG, the UN’s Messengers of Peace have names with broad recognition. Is there anyone who hasn’t heard the name Yo-Yo Ma, even if they have never heard him play the Dvořák cello concerto or another classic musical work? Then there is human rights advocate and Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, actor George Clooney, and pop musician Stevie Wonder. The practice of appointing distinguished and famous artists, thinkers, and advocates as Messengers of Peace began in 1998 and is intended to “help focus worldwide attention on the work of the United Nations.” As volunteers, these messengers travel to venues around the world and appear in the media as representatives of the secretary-general and the UN system.

Yet another kind of representative, the Goodwill Ambassador, has become popular among the UN bodies. A Goodwill Ambassador is a notable person who advocates on behalf of a specific UN fund, program, or agency. The Goodwill Ambassadors of UNICEF, for example, include an American tennis star and an Irish-born actor. The UN Environment Program (UNEP) features a Brazilian supermodel, a French photographer and journalist, and an American actor, while the UN High Commissioner for Refugees has signed up a Chinese actress, a Turkish singer, a Kazakh singer and composer, and a British supermodel, among others.

When Ban Ki-moon became secretary-general, he was little known to the Western media, who speculated that he would probably maintain a lower public profile than his predecessor, Kofi Annan, an activist secretary-general who stretched his office to pursue an expanded vision of international diplomacy and action.

Ban Ki-moon has developed his own official style, which begins with long working days and extends to visits to every corner of the world and frequent public statements about global problems, dangers, and crises. Early in his tenure, for example, Ban went to Sudan to visit Darfur, where internal violence was rampant. “I went to listen to the candid views of its people—Sudanese officials, villagers displaced by fighting, humanitarian aid workers, the leaders of neighboring countries,” Ban reported upon his return. “I came away with a clear understanding. There can be no single solution to this crisis. Darfur is a case study in complexity. If peace is to come, it must take into account all the elements that gave rise to the conflict.” An optimist by nature, Ban declared that while “complexity makes our work more challenging and difficult . . . it is the only path to a lasting solution.”

Former US ambassador John Bolton observes that Ban takes a more measured approach than Annan, whose “ambitions were too sweeping.” Bolton sees broad agreement among observers that Ban’s “low-key style of management is widely approved by all different parts of the world.” Former US diplomat William Luers rates Ban “a better talker than orator. He likes one-on-one and conversational exchanges. He sets priorities and doesn’t try to do too much. He is an extremely hard worker and very focused on core problems.”

What are these core problems? Ban Ki-moon stated his agenda when he assumed office. It began with protecting the global climate, because otherwise we are all threatened. It asserted the human duty to intervene when nations or regions fall into chaos and destruction, and it demanded an end to nuclear proliferation, because that could lead, among other evils, to terrorist groups gaining possession of weapons of mass destruction. The agenda highlighted the need to fulfill the eight Millennium Development Goals, or MDGs (discussed in chapter 14), which are intended to raise the poorest nations to an acceptable level of social and economic development. And it included reform of the UN’s fiscal and management structure to make the organization more efficient and give it the means to address an escalating series of needs and demands from the world community.

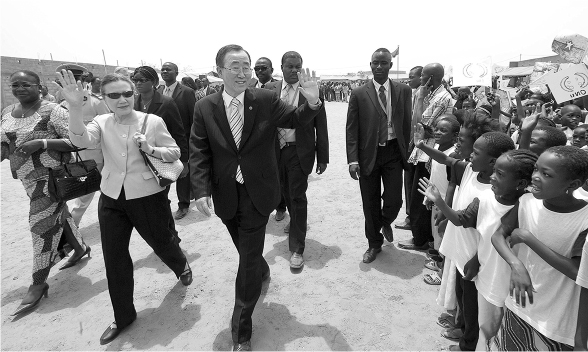

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and his wife, Yoo Soon-taek, visit a primary school in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, April 23, 2008. UN Photo / Eskinder Debebe.

At the beginning of his second term, in 2012, Ban laid out a five-year “action agenda” that restated much of his previous view and elaborated on the main points. He spoke of the need to define a post-MDG development framework that would also address issues of energy, food, clean water, and the health of the oceans and their living resources. Prevention received extended treatment, including prevention of violent conflict and human rights violations, as well as the “responsibility to protect,” often referred to as R2P, which will be discussed in chapter 11. Among the final agenda items Ban placed “supporting nations in transition,” meaning member states that seek to become more democratic, transparent, and prosperous, and “working with and for women and young people,” referring to violence against women, women’s political and social and economic participation, and improved efforts to “address the needs of the largest generation of young people the world has ever known.”

Two years later, at a news conference in December 2013, Ban restated his determination to advance the agenda, but with some surprisingly sobering words. “I am just amazed that there are still so many challenges unresolved,” he replied when asked about the lessons he had learned as secretary-general. “The number of crises now seems to be increasing [more] than during my first term. At the beginning of my first term, the situation in Darfur was the key, most serious issue.” Now, he said, there were “so many issues,” such as the civil war in Syria and murderous conflict in the Central African Republic and Mali: “You name all these issues.” The secretary-general also pointed a finger at the member states. “Another lesson is that I have seen some weakening political will. Sometimes, national interest prevails over some global problems. We first try to address all global threats, global crises. Good global initiatives and solutions will help domestic solutions, too.”

Whatever the secretary-general presents as his agenda, he must pursue it with the support, or at least without the opposition, of the UN member states, especially those that have the most international clout. Most observers assess Ban’s working relationship with the US government as correct and generally good. Stewart Patrick of the US Council on Foreign Relations argues that Ban is “pretty much in sync with US goals and he doesn’t get out ahead of them.” Richard Gowan of New York University says the United States is happy with Ban “most of the time” and views the secretary-general as “a solid, good soldier.”

Ban’s ability to work collaboratively with China and the United States has produced results. For example, he conducted difficult negotiations on climate change (then opposed by both China and the United States) and intervention in Darfur (opposed by China). He has also been willing to speak out even when his comments might seem out of sync with the interests of powerful member states. During the conflict in Syria, in 2013, Ban urged nations to refrain from supplying arms to the combatants while the Russian government was providing arms to the Assad regime and the US government and other governments were mulling a possible arms transfer to some of the rebel groups. Ban Ki-moon’s position is perhaps more nuanced than one might expect.

Ban’s agenda is his guide for his second and last term as secretary-general. Then someone else will assume the post and define the priorities and action plans. Who will that be? Speculation on a successor begins soon after the incumbent has entered the final term, and it mounts as the term nears its end. Regional factors suggest that Ban’s successor will not come from Asia or Africa, which have given us the last three secretaries-general, nor from Latin America, home of Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar (1982–91). That leaves Europe. But since Western Europe has provided several secretaries-general and Eastern Europe none, it may now be Eastern Europe’s turn. Aside from geographical factors, the other key determinant will be the preferences of a few major powers. What kind of secretary-general might the United States want? Richard Gowan doubts that Washington wants another high-profile activist like Kofi Annan, but, he notes, a lower-profile candidate might not seem exactly right either.

Only as the candidates walk on the stage will we be able to assess the field and speculate on which of them is most likely to gain US backing—and that of other key governments. The sitting US administration, when it evaluates the candidates, will have to consider not only the personal qualities and values of each but the nature of the rapidly changing world in which the secretary-general will operate.