Definitions and Descriptions

Of the types of abnormality discussed in this book, psychosis and the psychotic disorders challenge our understanding most. They have generated a bewildering array of biological, psychological, social, sociological, and even political, research, with proportionately the least return in the way of comprehension of their nature and causes. Opinions about them are invariably wildly polarized, backed by evidence that is often unreplicated, flatly contradicted by other findings, or deliberately chosen to suit the argument. Because the topic is so unusually vast and untidy we, too, will need to be selective in the material we include here. It is therefore highly likely that we will also present a one-sided view – and the reader should be aware of that. But, given space limitations, some angle on the topic had to be chosen if we were to give a coherent account of a highly complex field. We were helped in this by the fact that one of the major issues about the psychotic disorders is precisely the one that is the central theme of the book.

In the case of psychosis, dimensionality, the possibility of an association between normal and abnormal, between personality and pathology, is much more controversial than for anything we have discussed so far. In the non-psychotic domain, debate certainly exists and opinions differ about the extent of dimensionality in clinical disorder and about other matters, such as the importance of genetic dispositions, the influence of biological – as against, say, cognitive – explanations, and so on. But the discussion there is of a different order from that surrounding psychosis. This has something to do with ‘believability’, or intuitive feel, or a sense of ‘there but for the grace of…’. Most people, however rabidly against the view that biology plays a part in mental illness (or disagreeing with other things we have said), will have some insight into the disorders we have discussed so far – a realization of some connection to their own personal experience, or possibility for experience. That is usually not so true for the psychotic disorders, which for many of us seem alien, something which only the truly mentally diseased could suffer.

Nevertheless, dimensionality in the psychotic disorders is an issue that is currently the subject of live debate in psychiatry and abnormal and clinical psychology. This gives us a ready-made framework for organizing the material here and we shall make dimensionality the central theme of the chapter. For this reason, a fairly large part of the discussion will be taken up with theoretical and clinical questions relevant to the topic, alongside examining empirical evidence that bears on it. But, first, some terminology.

Actually, much of the vocabulary we need has been mentioned at various points throughout the book. And, in any case, the kinds of clinical state we shall be discussing will, in general terms, already be fairly familiar to the reader; corresponding, that is, to what in everyday discourse we refer to as the mad, the crazy, the lunatic, or the insane. Nevertheless, it is worth briefly recapping the more technical language used in connection with these disorders, now that they are the topic of a single chapter.

‘Psychotic’ (and ‘psychosis’) we introduced right at the beginning when outlining a broad framework for the layout of the book. We noted that, although there is no single criterion for defining psychotic, there would be a general consensus that, once recognized as in need of help, a person would be said to fit that description if he or she showed certain features: loss of touch with reality and lack of insight into weird behaviours, and strange thoughts, perceptions and feelings which, on the face of it, seem outside the range of normal experience. In current usage the other major distinction that would then need to be made is between, on the one hand, the schizophrenic form of psychosis and, on the other, manic-depressive psychosis. (In the DSM and the ICD the latter has now been renamed ‘bipolar affective disorder’, but here we shall use both terms interchangeably.)

On the personality side we have also already encountered the notion of ‘psychoticism’, in at least two guises. One is in a generic sense, to articulate the idea of some kind of dimensionality connecting the normal to the abnormal in the domain of psychosis. The other is more specific, as a third dimension in Eysenck’s theory, intended to account, in combination with his other two personality dimensions, for underlying dispositions to schizophrenic and manic-depressive psychosis. Then, while discussing the personality disorders, we came across the DSM Axis II ‘Mad’ cluster, the clinical features of which have a reference point in the symptoms of Axis I psychotic illness. Lastly, also in Axis II we noted that Borderline Personality Disorder, although in a different cluster, has some connections to psychosis.

We also need to note a potential point of contact, yet also distinction, between the content of this chapter and our coverage of depression in Chapter 5. As discussed there, depression was taken to mean low moods of varying severity, symptom content, and perhaps different biologies. Some of those features might be shared with the form of depression found in bipolar affective disorder. However, the latter was left out of Chapter 5, for two reasons. First, the presence of the manic element in bipolar disorder helps to identify some potentially different aberration of mood from depression occurring on its own. Second, research on manic depression has conventionally formed part of the psychosis literature, rather than that on depression per se.

We shall discuss manic depression in more detail towards the end of the chapter, but it is convenient to summarize its distinguishing characteristics now. These are shown in Table 9.1, where we emphasize the more extreme features of the disorder.

Table 9.1 Bipolar Affective Disorder (Manic depression): main features.

| Mania |

Depression |

|

| Elated mood |

Suicidal mood |

| Overactive behaviour |

Sluggish behaviour |

| Racing thoughts and speech |

Slow thinking and reduced speech |

| (‘Flight of ideas’) |

Delusions of sin, poverty, etc. |

| Delusions of grandeur |

Hallucinations |

| Hallucinations |

|

Most of the depressive symptoms will be familiar from Chapter 5; the manic ones perhaps less so, but they do fairly obviously contrast, cognitively and emotionally, with those of depression, However, we should clear up one misconception about the ‘bipolarity’ of manic depression. Contrary to some belief, mania and depression do not correspond exactly to the ‘happiness’ and ‘sadness’ of normal mood. Thus, mania – or what is often referred to as ‘hypomania’ – is not the same as happiness. Manic individuals may become very irritable if thwarted in attempting to carry out unrealistically grandiose schemes or, if asked to do so, judge their prevailing mood as depressed (Lester & Kaplan, 1994).

Turning to schizophrenia, its diagnostic features, according to the DSM-IV, are listed in Table 9.2. The schizophrenia construct raises several issues, some to be discussed in following sections, but one general observation should be made at this point. It is evident from Table 9.2 that, under the DSM-IV, an individual could be diagnosed as ‘schizophrenic’ by meeting only two, and any two, of a range of quite different criteria. Indeed (see under ‘NOTE’ in the table) only one criterion needs to be met if the symptom happens to be of a certain, peculiar quality: what is described as of the ‘first rank’.

Table 9.2 Schizophrenia: diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV).

| Two (or more) of: |

| Delusions |

| Hallucinations |

| Disorganized speech (for example, frequent derailment or incoherence) |

| Grossly disorganized or catatonic behaviour |

| Negative symptoms, that is, affective flattening, alogia or avolition |

|

| Note: Only one criterion if symptom of 'first rank' type. |

The notion of first rank symptoms, first proposed by the German psychiatrist Kurt Schneider (1959), is an important one in helping to articulate some questions that have always puzzled, and continue to bemuse, researchers on schizophrenia. What are the ‘fundamental’ features of schizophrenia? Is there some unique feature that is sufficient to define the condition? What is it about the disorder that ultimately needs to be explained? The dilemma is illustrated in Table 9.3, which contrasts two different views on this. One is the first rank symptom position just mentioned: that certain experiences of people clinically labelled ‘schizophrenic’ are so bizarre, incomprehensible, and distant from the normal that we are surely convinced that these must be central to the disorder.

Table 9.3 Primary symptoms of schizophrenia: two perspectives.

| According to Bleuler |

| Disorder of thought process: |

| Loosening of associative thought |

| ‘Splitting’ of cognition and emotion |

| According to Schneider |

| First rank symptoms: |

| Audible thoughts and ‘third person’ hallucinations |

| Delusions of external control over emotions, thoughts, willed action |

In contrast is the view traceable to Eugen Bleuler who, some 100 years ago, coined the term ‘schizophrenia’ (Bleuler, 1911). He believed that hallucinations and delusions were what he called accessory symptoms, viz. secondary, psychological consequences of a more primary, physiological process that constituted the core of schizophrenia. A particularly important defining feature of this primary process was the loosening of associative thought which, in the subsequent terminology popularized by Schneider, could be elaborated into first rank (but, according to Bleuler, aetiologically secondary) symptoms. It is evident from Table 9.2 that current professional practice for diagnosing schizophrenia is a confused mix of these two positions; for example Criterion 3 – thought and speech derailment – represents the Bleulerian tradition. The bias, however, is clearly towards the view that first rank symptom diagnosis is preeminent. This is understandable. Reporting that aliens in outer space are responsible for the thoughts in your head certainly seems more crazy than bemusing your neighbour with your stream of consciousness style of conversation!

The Issue of Heterogeneity

It is already obvious that psychosis shows considerable clinical variability. But how do we interpret this? Are the disorders literally independent of one another and of quite different origins? Or do they represent different expressions of a single underlying cause or combination of causes? There are really two debates here. One concerns the separateness, or otherwise, of schizophrenia and manic depression; the other relates to heterogeneity within schizophrenia itself. We shall look at each of these in turn.

One Psychosis or Two?

It has become the received wisdom in psychiatry that manic depression and schizophrenia are distinct disorders, with quite different aetiologies. This view is even prevalent outside professional circles, where the two ways of going crazy are viewed very differently, even to the extent of social evaluation. Schizophrenia – indeed anything with ‘schizo’ in the label – is usually judged malign, dangerous, deteriorating, and irreversibly damaging to the person. The moods of manic depression, on the other hand, although recognized in their extreme form as signs of illness, are viewed as less permanently dysfunctional – in some quarters even as vaguely romantic, through supposed connections to things such as artistic talent and the creative process.

Yet it is important to realize that, historically, the bipolar/schizophrenia dichotomy currently in vogue in psychiatry actually represents only one of the possible perspectives on psychosis. Indeed, separating out two ‘types’, as in the current psychiatric nosology, is relatively recent, owing much to Emil Kraepelin, the great nineteenth-century classifier of mental disease (Kraepelin, 1919). It was the two forms of insanity he recognized – manic depression and dementia praecox (later renamed ‘schizophrenia’ by Bleuler) – that have became enshrined in modern diagnostic manuals. Yet, long antedating Kraepelin, there was a school of thought favouring a ‘unitary psychosis’ (or Einheitpsychose) theory. This proposed a single mental aberration which, shaped by different influences, resulted in varied expressions of madness (see Berrios, 1995).

Despite the monopoly of Kraepelinian thinking about insanity, the unitary viewpoint never died entirely. In fact, outside psychiatry, in the personality domain, it continued to have a strong influence on the way some psychologists thought about psychosis. Most obviously, it survived in Eysenck’s notion of ‘psychoticism’ as a personality dimension common to all forms of psychosis. The idea formed part of his theory from its inception; but Eysenck’s opinion on the matter was either ignored or ridiculed by psychiatrists. However, in recent years the unitary view of psychosis has enjoyed some revival among clinicians and medical researchers, and is now beginning to re-emerge as a strong contender on how we should construe schizophrenia and manic depression: as entirely separate disorders or as variations on a common theme. We shall look at the arguments and evidence for this later in the chapter, when we come to discuss bipolar disorder.

One Schizophrenia or Several?

Distinguishing schizophrenia from bipolar disorder does not solve the problem of heterogeneity in psychosis; it merely narrows the domain that we need to puzzle over. As noted when discussing the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, there is potential for considerable variability in its clinical presentation. This should not surprise us. Bleuler never intended to refer to a single syndrome. From the very beginning he talked, instead, of ‘the schizophrenias’ as a group of disorders, with different clinical features. It was mostly the awkwardness of linguistic usage that subsequently caused the term to be used in the singular, a convention which – having made the point – we shall continue to follow here.

There have been many attempts to deal descriptively with the clinical variability of schizophrenia. The traditional diagnostic approach – perpetuated in both the DSM and the ICD – has been to name subtypes, defined according to the cluster of symptoms that predominates in the patient. Types include ‘catatonic’, ‘paranoid’, and ‘hebephrenic’ (a quaint label from the very early history of psychiatry). We shall not dwell in detail on this subtyping, except to make two points. First, in both the DSM and the ICD the main subdivisions of schizophrenia are supplemented by reference to other varieties of psychosis, such as ‘delusional disorder’ and ‘brief psychotic disorder’. Even without manic depression, the heterogeneity of psychosis is well catered for in the diagnostic manuals. The second point to make about this subtyping concerns its relative lack of utility for (and use in) scientific research on schizophrenia. Where researchers have paid attention to clinical variability in their samples (which mostly they have not) they have tended to look elsewhere for subclassifications. These have taken many forms, ranging from simple, empirical dichotomies – for example paranoid versus non-paranoid – to more elaborate, statistically derived, clusters or dimensions.

Currently, the most widely quoted research classification is based on a distinction between positive and negative symptoms (Andreasen & Olsen, 1982; Crow, 1985). Positive symptom – or what is sometimes called Type I – schizophrenia is defined by the presence of active symptomatology, such as hallucinations, delusions, and florid thought disorder. Negative symptom (Type II) schizophrenia is characterized by a lack or poverty of behaviour: thought, feeling and motor activity, perhaps driven by a low motivational state. Although still very popular, this dichotomy may be faulted on a number of grounds:

- Subjective accounts of the psychotic experience suggest that it is doubtful whether ‘negative’ symptoms define a type of schizophrenia. It is more likely that positive and negative symptoms represent alternating states occurring at different times within the same individual (Bouricius, 1989).

- If it does define a ‘type’ of schizophrenia, the ‘negative’ form probably refers to the chronic end-state, without florid symptoms, into which some individuals progress after years of adaptation to the illness.

- Diagnosing schizophrenia at the first episode solely on the basis of negative symptomatology, in the absence of positive symptoms – classically the core feature of psychosis – is unconvincing. How is it distinguishable from depression?

- The meaning of ‘negative symptomatology’ is ambiguous. It could be: a way of coping with the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (for example, as social withdrawal); an effect of antipsychotic medication; or part of a manifestation of depression.

- Research suggests that a simple two-syndrome dichotomy is oversimplified. Statistical analyses now suggest that there are at least three (and possibly as many as five) dimensions in schizophrenic symptomatology (Arndt et al., 1991; Lindenmayer et al., 1994). This does include negative and positive symptom features. But, in addition, an important subdivision of the positive aspect is now recognized: one part corresponds to first rank symptoms of the kind described earlier, whereas the other has to do with disorganized, derailed thinking, more in line with Bleuler’s conception of the primary disorder in schizophrenia.

Despite these criticisms, the negative/positive distinction – or some elaboration of it – probably is along the right lines, as a rough template, easily recognizable to clinicians, of how schizophrenic symptoms can vary.

Dimensional Aspects of Schizophrenia

Appreciating that, in whatever form, there is some kind of dimensionality in schizophrenia is important because it is no longer possible fully to understand the disorder, or research being conducted on it, without paying attention to that aspect. This is true in several respects: the genetics of schizophrenia; the various models currently being formulated to explain the illness and the predisposition to it; and methodological issues that arise in trying to investigate these topics. But, compared with the other disorders, how dimensionality applies to schizophrenia has become more controversial and the special questions it raises need considering further.

Quasi- Versus Fully Dimensional Models

As noted elsewhere in the book, ‘dimensionality’ enters into disorder in two quite different ways. One is as continua of personality dispositions, for example strength of anxiety traits. The other is as variations in illness severity; for example number or severity of anxiety symptoms. The existence of the latter kind of dimensionality in schizophrenia is not particularly contentious, since the symptoms of the illness can sometimes appear in a rather muted form. It is this observation that has given rise to the idea of the schizophrenia spectrum and to connections between schizophrenia and the personality disorders. Of the latter, Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD) has received most attention, as a possible mild variant of schizophrenia. The reasons for this are obvious as can be judged from the clinical criteria for SPD, shown in Table 9.4; it can be seen that this personality disorder is defined very much in terms of dilute versions of schizophrenic symptoms.

Table 9.4 Schizotypal Personality Disorder: diagnostic criteria.

| Ideas of reference |

| Odd beliefs or magical thinking |

| Unusual perceptual experiences |

| Odd thinking and speech (vague, circumstantial) |

| Suspiciousness |

| Inappropriate or constricted affect |

| Odd eccentric behaviour or appearance |

| Lack of close friends |

| Excessive social anxiety |

As we know, SPD is not the only representative of the ‘Mad’ cluster in the DSM Axis II; viewed more broadly, the ‘schizophrenia spectrum’ could be said to take in the other Cluster A disorders, viz. Paranoid Personality Disorder and Schizoid Personality Disorder (Maier et al., 1999). This would acknowledge both the severity implications of the spectrum, as well as its heterogeneity; reflecting schizophrenia itself. However, the main point is that the

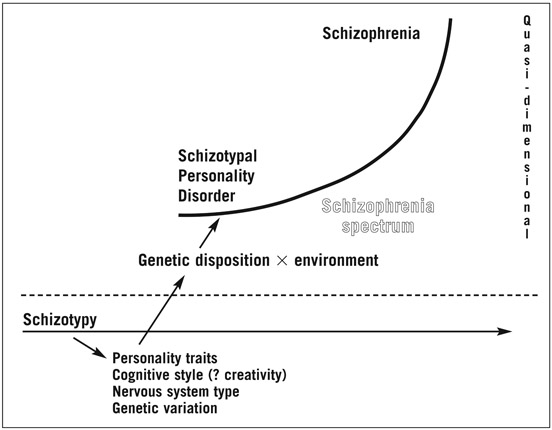

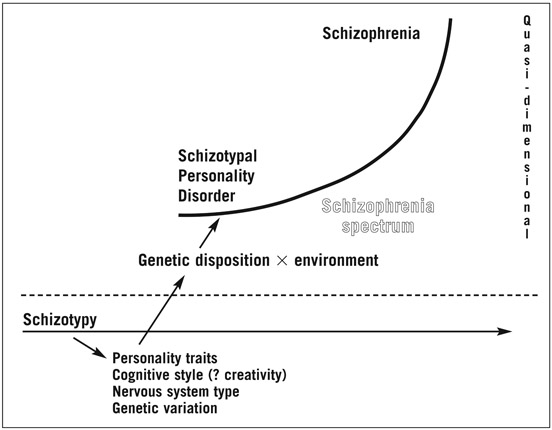

Figure 9.1 Comparison of two dimensional models of schizophrenia.

dimensionality we are looking at here refers to a continuum within the illness domain, consistent with the well-recognized medical principle that diseases frequently do present with different intensity.

An alternative, more radical, view of the dimensionality of schizophrenia would go further than that. It would argue that schizophrenia is, in principle, no different from the other illnesses discussed in this book; just as anxiety traits predispose to anxiety symptoms, so ‘schizophrenic’ personality traits predispose to schizophrenic symptoms.

Figure 9.1 illustrates the essentials of these two models – denoted, respectively, ‘quasi-dimensional’ and ‘fully dimensional’. Two points should be noted. First, according to the fully dimensional view, in moderate amount the underlying traits predisposing to schizophrenia are perfectly adaptive features of personality; in the same way that mild trait anxiety can be beneficial. It is this proposal that has created most controversy in debates about dimensionality and schizophrenia: to many critics the suggestion that there could be anything healthy in a seriously disabling condition like schizophrenia seems absurd. The second point to note about Figure 9.1 is not specific to schizophrenia. It is simply a reminder about how the two forms of dimensionality relate to each other and how the fully dimensional model is more inclusive than the quasi-dimensional model. This is naturally the case since traits at the personality level are more universal than symptoms; the latter only occur once the person has passed the threshold into illness (as depicted in Figure 9.1 moved from the bottom to the upper half of the diagram).

Irrespective of the model of dimensionality adopted, the central concept that has guided research on the topic is ‘schizotypy’. The term is owed to Rado (1953), a psychoanalyst, but the construct was later developed by Meehl and his followers (Meehl, 1962, 1990; see also Raine et al., 1995) within a genetic theory of schizophrenia. The Meehl school is very firmly grounded in a quasi-dimensional theory: schizotypy is regarded as the phenotypic expression of a genetically determined biological malfunction which, unless compensated for, will result, to varying degree, in schizophrenic illness. The fully dimensional view is more relaxed about the ‘normality’ of schizotypal traits; as noted above, these are perceived as part of natural variations in personality, an idea that obviously owes much to theories in the Eysenckian tradition.

These two contrasting formulations of dimensionality have often led to different conclusions about schizophrenia and schizotypy, and ways of studying them. To illustrate, fully dimensional theorists have made considerable use of the notion of ‘healthy schizotypy’, to denote (perhaps the majority of) individuals who are high on the dimension but who show no evidence of illness (McCreery & Claridge, 2002; see also Claridge, 1997). For quasi theorists this is an impossible idea! According to them, genuine schizotypy is always a sign (or potential sign) of schizophrenia, however mild and/or concealed. True, there are cases, it is argued, where the person’s behaviour mimics schizotypy but, in genetics jargon, these are what are called ‘phenocopies’, individuals in whom the superficially similar behaviour arises for different reasons.

These different conceptions of schizotypy have a knock-on effect on research methodology. In looking in the general population for signs of schizotypy – neurocognitive, biological, or whatever – quasi theorists always search for indicators of defect in very targeted subsets of individuals; these will be subjects who have already been strictly screened, for example by questionnaire, as falling into the schizotype category, or ‘taxon’ as it is called (Lenzenweger, 1993). Fully dimensional theorists, on the other hand, assume that schizotypal characteristics are widespread as signs of naturally occurring variation. Hence, they will use the same methods as those employed elsewhere in individual differences research, such as correlational analyses in unselected samples of subjects. As discussed later, fully dimensional theory has also tended to assume that evidence of schizotypy in healthy individuals need not necessarily show up as performance deficits. Instead, it might be found in perfectly functional behaviours.

Measurement of Schizotypy

Despite the above differences in research aim and interpretation, the descriptive measurement of schizotypy itself has been a shared endeavour, common to both schools of thought on the topic. This has resulted in the construction of a large number of self-report questionnaires for use in non-clinical populations. Scales have been devised from a number of different points of view and for different purposes: as specially developed research instruments, as scales modelled on the DSM criteria (for example, for SPD), or as derivatives of existing questionnaires (Edell, 1995; Mason et al., 1997). Of most interest to us here are the many factor analyses of these questionnaires that have been carried out, by several research groups (see Mason et al. (1997) for a summary of studies up to that date and Schizophrenia Bulletin (2000) for several later reports).

Unsurprisingly, all investigators conclude that ‘schizotypy’ is not a single construct, but consists of more than one component. Almost without exception, every study has demonstrated a minimum of two dimensions that correspond to, respectively, the positive and the negative symptoms seen in schizophrenia itself. Beyond that, however, there is some difference of opinion. Looking across all studies, the consensus is that schizotypy consists of three dimensions. However, this may reflect the number of scales included in the various analyses. One study, the most comprehensive to date – in terms of number of scales included, as well as sample size – has suggested that there may actually be four schizotypy components (Claridge et al., 1996). These are shown in Table 9.5, together with typical self-report items that help to define them: these are taken from a questionnaire – the O-LIFE – developed from the factor analysis (Mason et al., 1995).

Table 9.5 O–LIFE – typical items.

| Unusual experiences |

| Are your thoughts sometimes so strong you can almost hear them? |

| Have you ever felt you have special, almost magical powers? |

| Cognitive disorganization |

| Do you ever feel that your speech is difficult to understand because the words are all mixed up and don't make any sense? |

| No matter how hard you try to concentrate do unrelated thoughts always creep into your mind? |

| Introvertive anhedonia |

| Do you feel very close to your friends? (–) |

| Are people usually better off if they stay aloof from emotional involvements with other people? |

| Impulsive Nonconformity |

| Do you ever have the urge to break or smash things? |

| Are you usually in an average kind of mood, not too high and no too low? (–) |

The first three of the components listed in the table are virtually identical to those reported by other workers; they correspond, at the trait level, to what in the clinical sphere is now agreed to be a fair summary of schizophrenic symptomatology. The fourth factor – Impulsive Non-conformity – possibly represents some set of personality traits relating more to the affective form of psychosis. We will return to that point again when discussing manic depression.

Explaining Schizophrenia

Research Problems and Strategies

Compounding the difficulty of grasping conceptually what is meant by ‘madness’ is the problem of studying it scientifically. The two are, of course, connected and there are many practical ways in which the bizarre quality of the psychotic state affects its empirical investigation. We have already mentioned the heterogeneity of schizophrenia; taken together with the similar picture found for schizotypy, this means that attempts to give a single explanation of a single disorder are almost bound to fail. And variability almost certainly extends beyond between-subject differences to within-subject variation. It can be shown that, even for simple physiological responses, such as the galvanic skin response, individual schizophrenic subjects show enormous day-to-day fluctuation (Claridge & Clark, 1982). Few, if any, studies of schizophrenic subjects bother to take more than a one-off reading of whatever it is they are interested in measuring. That, of course, is also true of research in other fields of abnormal psychology. But it might be particularly serious in the case of schizophrenia, because what causes this individual instability of function could itself be an important clue to the nature of the disorder. Certainly it was once said that the only consistent observation about measures taken from schizophrenic subjects is their variability.

Other research hazards stem from the effect of the clinical state on the measurement process itself This is particularly serious for psychological studies, for example of performance on laboratory tasks that are widely used in research on schizophrenia. What does it really tell us about schizophrenia if, throughout testing, the subject is listening to hallucinatory voices or distracted by delusional thoughts about the experimenter – or merely not looking at the computer screen on which the test stimuli are being displayed! A partial way round the problem is to study subjects whose more acute symptomatology is controlled by antipsychotic drugs, a procedure generally forced on researchers anyway since most schizophrenic subjects are on some form of medication. But this creates its own difficulties because it is never clear what is being measured: a genuine feature of the illness or the effect of the drugs being used to treat it. Which of course is a critical consideration; not just for psychological studies, but also (perhaps more so) for those of a biological nature.

To a much greater extent than for other disorders, research on schizophrenia is therefore very largely a matter of playing swings and roundabouts with methodology, balancing the ideal against what is practical. Or, alternatively, trying to step around the difficulties altogether and seeking other research strategies. It is here that studies of schizotypy come in. The reasoning behind this is quite straightforward. If, as is argued, high schizotype subjects share important features with schizophrenic subjects, then studying them, instead of people with the full-blown clinical illness, should help because it then becomes possible to study ‘schizophrenia’ without the confounding effects of acute mental disturbance or medication. Selection of highly schizotypal individuals for this purpose is either by means of the questionnaires referred to in the previous section, by equivalent interview procedures, or – in the case of clinical samples – by virtue of subjects meeting the criteria for Schizotypal Personality Disorder.

All of the above refers to the use of the ‘schizotypy strategy’ to examine possible mechanisms of psychotic disorder. But studying schizotypy has another purpose, established in its own right. This concerns the identification of features that help to put people at risk for schizophrenia. Here, the genetics of the disorder are becoming an increasing focus. It is now generally accepted that, in so far as genetic factors have a rôle to play in schizophrenia, these are likely to be complex, with many genes involved and graded effects being the order of the day. Conceptualizing the genetic architecture of schizophrenia in this way sits well with the dimensional perspective intrinsic to schizotypy which is now beginning to emerge as a ‘strong’ construct that could capture at least some of the underlying genetic disposition to schizophrenia. Thus, any objective measurements of schizotypy that are unearthed are potentially useful indicators of risk for the illness; just as – to recall our earlier analogy – blood pressure acts as a measure of risk for hypertension and, beyond that, more serious vascular disease.

Genetics and Risk for Schizophrenia

Although much of the detail is still missing, the contribution of genetic influences is one of the few factual certainties about schizophrenia. Even in the absence of the discovery of specific genes, this is clear from kinship data, as shown in Table 9.6. Notably – and a sure sign of the heritability of a trait – monozygotic twins are much more concordant for schizophrenia than dizygotic twins and the degree of risk for the illness changes in an orderly manner according to the closeness of the kinship, from first- to second-degree relatives, and so on (Gottesman, 1991).

Table 9.6 Risk for schizophrenia according to kinship (per cent).

| Monozygotic twins |

43 |

| Monozygotic twins (reared apart) |

58 |

| Dizygotic twins |

12 |

| Two Schizophrenic parents |

46 |

| One Schizophrenic parent |

6 |

| Sibling |

10 |

| Aunt |

2 |

| First cousin |

2 |

| Unrelated |

1 |

There is, however, a caveat about the observation that the concordance rate in monozygotic twins is approximately 50 per cent. It could be argued that the figure looks vaguely suspicious, given the great heterogeneity of ‘schizophrenia’. Individual studies of monozygotic concordance for schizophrenia have ranged from zero to more than 90 per cent. Is it possible that the value of 50 per cent now generally quoted is merely some average of a range of heritabilities for entirely different psychotic disorders, different variants of schizophrenia, or just illnesses of different severity? Certainly, on the last point it is known that calculated heritabilities for schizophrenia vary proportionally with judged severity among the cases sampled (Gottesman & Shields, 1982). More intriguing – and rather puzzling – is an observation about heritabilities calculated on the same sets of twins, diagnosed, on one occasion, according to first rank symptoms and, on the other, by broader criteria for schizophrenia, taking in more Bleulerian features (Farmer et al., 1987; McGuffin et al., 1987). For broad criteria the results were very much those we have quoted above – approximately 50 per cent concordance for monozygotic twins. In contrast, the heritability of first rank symptom schizophrenia turned out to be zero! This tends to suggest that, despite their convincingly ‘psychotic’ appearance, first rank symptoms do not tap directly into whatever is inherited in schizophrenia; instead, they may indeed be secondary elaborations of some more fundamental (inherited) cognitive processes, along the lines visualized by Bleuler.

One thing that is certain from the genetics data is that environmental influences must also be important in the aetiology of schizophrenia. This has been interpreted in sharply different ways. A biological school in schizophrenia research has emphasized the importance of ante- or perinatal trauma as a possible factor, interacting with genetic disposition, to trigger the illness. A body of evidence supporting this claim has come from observations that schizophrenic subjects more frequently have a history of birth complications (Verdoux et al., 1997). A recent elaboration of this idea is the ‘two-hit hypothesis’ to which we referred in Chapter 2; the notion that genetically predisposed individuals may be made even more vulnerable by exposure to physiological stressors at critical points in development and then, through later trauma, be precipitated into illness (Bayer et al., 1999).

In contrast, a social interpretation of the genetic/environmental interaction is typically to be found in the classic study by Tienari (1991). He examined the rate of schizophrenic breakdown in subjects adopted away from their biologically schizophrenic mothers. As expected, having a biological mother who was schizophrenic increased the rate of schizophrenia in the offspring, even though reared in a non-schizophrenic family. But – and this was the important finding – the schizophrenia genetics revealed itself only if the adaptive family was psychologically disturbed. Put another way, it looked as though even individuals who were strongly loaded genetically towards schizophrenia could be protected from breakdown if their rearing family was healthy.

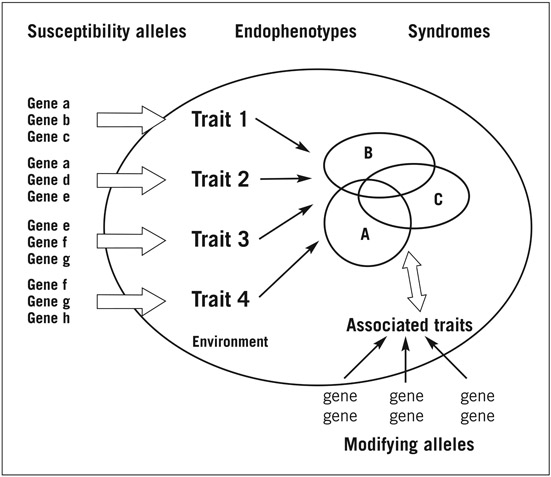

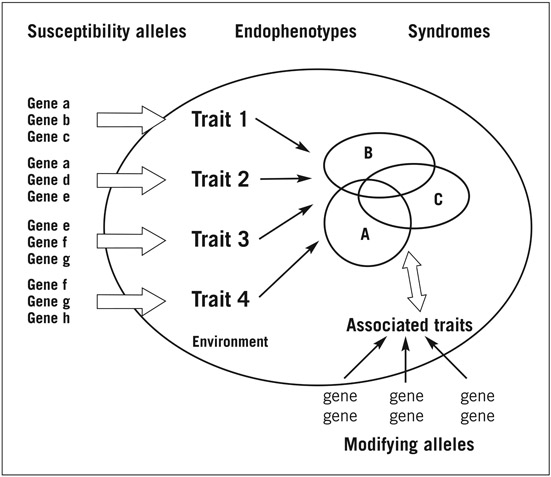

By itself neither of these formulations of the environmental influence in schizophrenia tells the whole story. For just as there are different clinical presentations, so there is almost certainly more than one route to psychotic illness. The only common factor seems to be some genetic disposition. But we could even ask about that: What does it mean? We have already seen that there are genetic influences in almost every kind of human variation, including the more familiar features of temperament and personality. Is it possible – as the fully dimensional model mentioned earlier would assume – that the network of traits contained within schizotypy/psychosis proneness is merely another example of that: personality dispositions waiting to be transformed into a variety of disorders? Certainly some thinking about the genetics of schizophrenia is moving in that direction, as Figure 9.2 illustrates.

The author of the model, Weinberger (2002), explains it as follows:

An argument can be made that schizophrenia is not a genetic illness per se, but a varying combination of component heritable traits (and genes) that comprise susceptibility and that interact with each other, with modifying alleles, and with the environment to produce the complex clinical phenotype. (Weinberger, 2002)

Of course, this is a terribly catch-all position: it can scarcely be wrong! But it is probably the best we have and better than claims – so far largely unsubstantiated and, with the odd exception, mostly abandoned – that there is a gene for schizophrenia. Returning to Figure 9.2, it would obviously help if we knew more about possible genes involved and the functional processes for which they code. But progress there has so far been fairly limited. Admittedly, claims have been made for several gene loci, some of which do have interesting connections to other aspects of schizophrenia. An example is a proposal that

Figure 9.2 Genetic model for schizophrenia (Weinberger).

the alpha-7 nicotinic receptor gene may contribute to the risk for developing schizophrenia. It has not escaped notice that this might relate to the long known fact that schizophrenic subjects smoke a lot (Hughes et al., 1986). But in other respects such observations sit rather in isolation, describing small effects that do not in themselves account for much of the variance in schizophrenia risk.

One notable development in genetics research on schizophrenia – implicit in Figure 9.2 – has been the realization that the clinical diagnosis is a very blunt, inaccurate phenotype for exploring the heritability of psychosis. In its place, it is argued, we should substitute, and look for the genetics of, intermediate phenotypes, or endophenotypes (Gottesman, 1991). These are measures that do not, at first glance, seem to have much to do with psychotic symptomatology; they are assumed instead to tap more basic – albeit quite narrow – behaviours that look as though they might underlie the clinical state. A widely quoted example is an index of smooth pursuit eye movement (SPEM). This has been extensively investigated following observations that a proportion of schizophrenic subjects showed an abnormality in their ability to follow, effectively, a swinging pendulum. Similar irregularities have been reported in other relevant target groups, including first-degree relatives of schizophrenic subjects and schizotypal and schizoid individuals (Levy et al., 1993).

Reiterating an earlier comment – and as will be illustrated further in the following sections – studies of schizotypy are a potentially rich source for discovering endophenotypes for schizophrenia. Notably – and this is a crucial point – much of the research to date has concentrated on the positive symptom aspects of schizophrenia (and schizotypy). Yet, the negative component – corresponding to anhedonia in schizotypy – might prove to be just as important, if not more so, in contributing to schizophrenia breakdown in vulnerable individuals (Tsuang, 2002). One piece of evidence to support this comes from a follow-up study of individuals administered schizotypy scales covering both positive and negative aspects, viz. magical ideation/perceptual aberration and anhedonia. Although the base rate of subsequent psychopathology was low, the positive symptoms scales did predict a somewhat greater frequency of general psychotic experiences (Kwapil et al., 1997). However, it was the negative symptom measure (social anhedonia) that was more able to predict specifically schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the subjects (Kwapil, 1998).

These findings should not surprise us too much. As we know, positive symptoms show almost no heritability. And, as experiences, they are quite common in the healthy population: this is true both for hallucinations (Johns & van Os, 2001) and delusions (Peters, 2001). Indeed, occurring as religious or other spiritual experiences they can be quite constructive, even problem-solving for the individual (Jackson, 1997). Unless they lead to outrageous or noticeably ‘sick’ behaviour, positive symptoms are likely to pass, at worst, as eccentricity. By comparison, anhedonia – both physical and social – looks more malignant and it is easy to see how, occurring in conjunction with aberrant cognitive experiences, some of the more disabling social and emotional signs of schizophrenic illness could develop.

Experimental Psychopathology of Schizophrenia

Over the more than 100 years since it was first described almost everything imaginable has been measured in schizophrenic subjects. This ranges from head size and facial appearance (still going on) to the constituents of sweat; the latter motivated by the observation that schizophrenic subjects smell differently (only abandoned as a clue to a possible chemical explanation when the cause was understood to be a combination of living in an institution, personal neglect, and treatment with paraldehyde, an old-fashioned sedative that exudes in the perspiration!). As always, current approaches still divide roughly along medical/non-medical lines: the search for the neurology and biochemistry of disease, as against more systematic enquiries, often by psychologists or psychophysiologists, into the mechanisms and correlates of schizophrenia This distinction is becoming increasingly blurred as biology more and more influences psychology, cognitive becomes neurocognitive, and perspectives on schizophrenia that originated outside medicine, such as the dimensional view, begin to have an influence on psychiatric thinking about the illness.

In trying to pick a way through what is still nevertheless an untidy literature, we shall take as our starting point what is often referred to as the experimental psychopathology of schizophrenia. This is particularly suited to our purposes here for three reasons. First, it draws very much upon research by experimental psychologists trying to get a handle on schizophrenia. Second, from its inception the area has been a natural breeding ground for research on dimensional models. Third, because there is an encouraging degree of continuity in the development of ideas about schizophrenia, over what amounts to nearly 50 years of research on its experimental psychopathology.

To enlarge briefly on the last, historical, point the aim from the beginning was to try to find ways of studying in the laboratory what were seen to be the core psychological processes that lie behind the manifest symptoms of schizophrenia. Given the clinical features of the latter, these processes were considered to be predominantly (though not exclusively) broadly cognitive in nature; in the terminology of the time to involve some or all of the stages in information processing. Clinical observation and experimental study converged to suggest that the cognitive functioning of schizophrenic subjects could be deviant at all points – from the simplest sensory analysis of a stimulus through to its highest level of representation in language and thought (Table 9.7).

Table 9.7 Psychological processes disturbed in schizophrenia.

| Sensation and Perception |

| Auditory – sounds louder, distorted, for example music backwards |

| Visual – objects brighter, duller, larger, smaller; no perspective/constancy |

| Other – tactile, olfactory, synaesthesia |

| Attention |

‘flooded’, or over-narrowed |

| Thinking & language |

incoherent, blocked or coherent, logical, but bizarre |

| Emotion |

fluctuant: blunted or hypersensitive (‘skinlessness’) |

The common problem was what Venables (1964), one of the foremost workers in the field at the time and a psychophysiologist, designated ‘input dysfunction’ – an inability to handle information in an orderly and stable way. Venables was also one of the few researchers, then or since, to have taken account of the great heterogeneity of schizophrenia. Table 9.7 demonstrates why he felt he needed to do this. The schizophrenic’s functioning could operate at two extreme and quite opposite ways: thinking and attention could be highly focused or all over the place, emotion be lacking or personally overwhelming, and so on. Venables’s idea therefore was that the schizophrenic nervous system has problems in input dysfunction in two directions: the ‘gating in’ of stimuli and their ‘gating out’. This causes it to be either abnormally open to, or closed off from, information, a fact reflected in the individual schizophrenic subject’s clinical symptomatology.

Venables’s theory of input dysfunction continues to be the inspiration for much contemporary research on schizophrenia by experimental psychopathologists. Significantly, it has also influenced parallel work on schizotypy, in particular the search for endophenotypes that might index the risk for schizophrenia. Illustrative here are studies by Braff and colleagues (Cadenhead & Braff, 2002). They identify three measures of sensorimotor gating that seem to be especially robust indicators of the input dysfunction; robust because all show deviations not only in diagnosed schizophrenic subjects but also in biological relatives of schizophrenics, individuals with the SPD diagnosis and healthy schizotypes selected by questionnaire. We have already mentioned a version of one of these measures – eye movement deviation. The other two are as follows:

- Pre-pulse inhibition of the startle response. This is a measure of the extent to which weak prestimuli, presented at brief intervals, reduce the magnitude of the blink reflex component of the startle response. Schizophrenic subjects and related risk groups show less of this normal inhibition, so that startle is relatively greater than usual.

- P50 event-related (ERP) suppression. In this EEG measure two auditory clicks are presented sequentially to the subject, a comparison being made of the corresponding evoked amplitudes in the wave occurring at a latency of 50 msec (P50). Typically, the secondly P50 is reduced in size: again this suppression occurs to a lesser degree in schizophrenic subjects and related groups.

The emphasis on inhibition as a critical mediating process in these measures is significant. In a number of different experimental and clinical contexts it has been argued that the relative failure of some kind of inhibitory process in the nervous system might account for many of the core features of schizophrenia; not least the tendency to irregular, unstable functioning that so characterizes the disorder. Gating abnormalities, such as those just described, are one application of this inhibition theory in schizophrenia research; another, at a higher level of psychological functioning, is the use of the construct to explain performance differences on cognitive tasks.

An example is negative priming, based on the Stroop colour–word paradigm (Moritz & Mass, 1997; Williams & Beech, 1997). Here, subjects are put through the usual procedure where they are asked to ignore the word meaning and name the hue of colour words written in incongruous colours; for example blue written in red. In the negative priming format the sequential pairs in the word list are related in meaning; in such a way that the hue to be named in any given stimulus is the same as the word ignored in the previous stimulus; for example blue (ignored) written in red (named) may be followed by yellow (ignored) written in blue (named). Negative priming refers to the extent to which colour naming speed is impaired, compared with a control condition in which the stimuli in the sequence are unrelated. The method has been widely used in schizophrenia research, with performance differences observed on the task being ascribed to variations in ‘cognitive inhibition’. The argument is that response speed will depend upon the extent to which the temporarily ignored word stimulus has been actively screened out of immediate attention and, therefore, the ease with which it can be recalled for colour naming on the following trial. Having less cognitive inhibition, schizophrenic subjects and schizotypal individuals will therefore have an advantage on the task and therefore show less negative priming.

The negative priming methodology has a special significance because it is one of a very small band of experimental procedures which are able to predict better performance than control subjects in schizophrenic and related groups. This feature enables the experimenter to circumvent the worry with most cognitive tasks used in this field: that the performance difference observed (expected to show up as deficits) might be due to non-specific factors that have nothing to with schizophrenia itself.

The possibility of predicting behavioural superiority in what is mostly regarded as a defect state has important implications for how we construe schizophrenia as illness, and what view we take of its dimensionality. Here, a rough-and-ready formulation that has guided some thinking about this is the notion – drawn from cognitive psychology – that there are individual differences in the threshold at which information becomes accessible to, or allowed into, consciousness. In schizophrenia this has been interpreted as having potentially detrimental effects: schizophrenic subjects actually have difficulty in what Frith (1979) once described as ‘limiting the contents of consciousness’. This would then be seen to account for the mental ‘flooding’ often reported by schizophrenic subjects – the inability to constrain associations and the overinclusive thinking that is ultimately responsible for their delusional ideas. But the weakness of cognitive inhibition that allegedly underlies this may be detrimental only in the real-life situation. Away from that, in the limited environment of the experimental laboratory, it could be beneficial, even in the clinically schizophrenic state; hence, the better than normal performance on tasks such as negative priming. As a corollary to that, in moderate degree, as a trait characteristic of schizotypy, weaker than average cognitive inhibition might be perfectly healthy, contributing – so the argument goes – to processes such as creativity, through its involvement in divergent thinking. Here we have a good example of the inverted-U effect, whereby a functional property of the organism can have both advantageous and harmful consequences.

Brain Systems in Schizophrenia

The back–front, top–down axes Attempts to identify brain areas or functional brain circuits that might be implicated in schizophrenia have proceeded along several lines. Some work has been an immediate, quite narrowly focused, extension of the kind of research referred to in the previous section, investigating possible neurobiological correlates of the psychology and psychophysiology seen to be disturbed in schizophrenia. Sensory gating provides a good example of this. Even when originally investigating the phenomenon under his label of ‘input dysfunction’, Venables proposed that the hippocampus was a critical brain structure. Recent research on an animal model of gating in the rat has confirmed that this is likely to be the case (Bickford-Wimer et al., 1990). By use of the same EEG P50 measure of gating as that employed in humans, it was found that certain neurons in the hippocampus were mainly responsible for the decrement in response to repeated stimuli. Among the neurotransmitters implicated in this effect, the inhibitory chemical, GABA, is known to play an important role.

Other brain research has proceeded along more traditional lines. This has sometimes taken the form of a simple medical search for the cause of disease; for example, through postmortem studies and, more recently, structural and functional brain imaging. Sometimes it has been more theoretically based, using imaging to look for correlates of the neuropsychological deficits reported in schizophrenia. Such deficits range across many cognitive skills, including attention, executive function, spatial ability, motor speed, sequencing, auditory processing, and most aspects of memory (Gur & Gur, 1995).

It is probably fair to say that nothing consistent about the brain in schizophrenia has emerged from what is an enormous – and, it has been said, ‘indigestible’ – mass of data. Consistent, that is, in the sense that, although individual studies have regularly shown differences between schizophrenic and control samples, replicable effects across investigations have remained elusive. So much so that one recent review of the literature concluded that there was no reliable evidence for a gross structural or functional cerebral abnormality that could be said to characterize schizophrenia as a diagnostic category (Chua & McKenna, 1995). The only exception was lateral ventricular enlargement. But that was relatively minor and judged, if it had significance, to be more of a vulnerability factor than an immediate cause of disease. Nevertheless, the finding for ventricular enlargement is worth bearing in mind because it has frequently been quoted in the schizophrenia literature as a sign of risk for the disorder (Cannon & Marco, 1994).

The pessimistic conclusion reached in the review cited above is not quite as bad as it sounds because it fails to take account of the heterogeneity of schizophrenia and the fact that trying to find a single, common abnormality is almost certainly misplaced anyway. Is it not more likely that different neural circuitry underlies different symptom clusters? There is some support for the idea, two brain areas having been of particular interest in that regard. One is the temporolimbic system which for a long time has been thought relevant because of clinical observations that individuals with known temporal lobe pathology often shown schizophrenic-like symptoms. Neuroimaging evidence from schizophrenic subjects themselves support the connection and go even further in suggesting that it is specifically the positive symptoms that are associated with temporolimbic dysfunction (Bogerts, 1997).

Possible explanation of negative symptoms has been proposed via other neural circuitry, implicating the frontal lobes. Results here have typically led to the conclusion that schizophrenic subjects show ‘hypofrontality’, seen either as reduced activity relative to other brain regions, or as a failure of the prefrontal cortex and associated structures to be appropriately activated by cognitive tasks (Velakoulis & Pantelis, 1996). These observations from brain imaging parallel the poor performance of schizophrenic subjects when examined with conventional neuropsychological tests of frontal lobe function. Significantly, the performance deficits found on such tasks are much more marked in those schizophrenic subjects rated high in negative symptomatology (Mattson et al., 1997). One suggestion, therefore, is that the cognitive failure observed in these individuals is an indirect one, due to motivational effects, mediated through the frontolimbic circuitry involved in drive and emotion – in this case at the low end, associated with anhedonia and negative symptomatology. There is an interesting connection here to findings discussed in Chapter 5 with respect to melancholic depression.

There has been some extension of the above research into investigations along the schizophrenia spectrum, including schizotypy. One of the most intriguing studies is a recent one by Buchsbaum and colleagues. Focusing on prefrontal and temporal structure and function, these authors used magnetic image resonance (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans in a comparison of schizophrenic subjects, healthy control subjects, and individuals with the diagnosis of Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD). There were two findings of interest. First, the pattern of effects observed in the fully schizophrenic subjects was roughly similar to that reviewed above; no generalized difference in all cases for all of the brain sites monitored, but definite evidence of deficiency in frontal and temporal areas. Second, SPD subjects showed a ‘compromise’ profile, which was a mixture of that for schizophrenic subjects and that for healthy control subjects: midway between schizophrenic subjects and normal individuals for temporal function, but with little deficit in prefrontal areas. The authors concluded that there was evidence that schizophrenia and SPD do indeed lie on a continuum, and further speculated that those individuals in the personality disorder part of the spectrum have some protective factor – identified in this case as effective prefrontal functioning – which guards them against full psychotic breakdown (Buchsbaum et al., 2002).

The horizontal axis A different neurobiological perspective (literally) on schizophrenia/schizotypy is that the clue to it all lies in some feature of the lateralization of the brain (Schizophrenia Bulletin, 1999). The idea is an old one, originating in early nineteenth-century writings about mental illness as a ‘warring’ between the two halves of the brain. The proposal was given some scientific credibility by the subsequent discovery that the cerebral hemispheres are indeed specialized for different psychological functions: first that the left hemisphere is dominant for speech and language and later that the ‘silent’ right hemisphere has a special involvement in, among other things, emotion. Subsequent, sometimes fanciful, simplifying of these left–right differences – for example, the contrasting of rational, linear and irrational, intuitive modes of cognitive processing – were easy meat for theories seeking to explain the chaotic, yet sometimes creative, psychology of madness. More sober scientific studies did not confirm this neat, romantic picture But nor did they entirely undermine it and over the years laterality explanations of psychosis have proliferated, coming into and going out of fashion more often than any other theory.

As with research on the other brain axes, left–right differences have been investigated from many points of view, with the same, or equivalent, methodologies. Needless to say, an equally dyspeptic mass of data has accumulated and similar differences of opinion on interpretation offered. As theories of schizophrenia, these have traditionally divided into three types. One – that the disorder is primarily a left brain dysfunction – is based on the well-documented evidence that schizophrenic subjects perform poorly on verbal tasks, coupled to claims from neuroimaging studies that they show abnormal left hemisphere activity (Gur & Chin, 1999). A second hypothesis is that schizophrenia is actually a right hemisphere disorder (Cutting, 1990). This, it is argued, is consistent with the perceptual and attentional symptoms of schizophrenia and with certain aspects of language disturbance, for example metaphor and humour, that are mediated by the right hemisphere. In this case, some of the impaired performance seen on left hemisphere tasks would be explained as due to interference from emotional arousal ‘spilling over’ from the right side of the brain. The third class of theory is that schizophrenia is associated with some kind of disturbed interaction between the two hemispheres.

Of the three possibilities, the last, although the most open-ended and most difficult to disprove, is the one that has received most attention in recent years. The general proposition is that schizophrenia is associated with incomplete lateralization of the brain – in practical terms, reduced left hemisphere dominance for language There are several sources of evidence for this theory (Sommer et al., 2001). Two types of data are illustrative.

The first concerns the anatomy of the planum temporale, a small structure in the temporal lobe encompassing Wernicke’s language area. In the majority of people the planum temporale is larger on the left than on the right side of the brain. However, it has been reported that in schizophrenic subjects this asymmetry is less; the structure is more often of similar size in both temporal lobes (Petty et al., 1995).

A second source of evidence for reduced laterality in schizophrenia comes from studies of hand preference. Although a crude index of laterality, handedness is relatively easily measured and has therefore given rise to many studies. The results appear, on the face of it, rather variable; but recent reappraisal of the findings suggests that there is a general theme: a tendency for schizophrenic subjects to show more mixed (though, interestingly, not more left) handedness (Satz & Green, 1999). Similar findings have been reported in several studies of healthy schizotypes selected by questionnaire (Shaw et al., 2001).

As with other perspectives on the brain in schizophrenia, there is the usual problem of heterogeneity and the fact that not all cases will conform to the generalizations made on the basis of average effects. Few writers in laterality research have addressed this question. An exception is Gruzelier (2002), who has made a special point of studying and speculating about it in both schizophrenia and schizotypy. His conclusion is that schizophrenics (and schizotypes) show a disproportionate tendency to shift, due to labile arousal, towards either left or right extremes of cerebral dominance. According to him, these correspond to two syndromes (or, in normal schizotypy, behavioural profiles): ‘active’ (left dominant over right) with largely positive symptoms and ‘withdrawn’ (right dominant over left), with largely negative symptoms.

Lastly, an imaginative interpretation of laterality theory that deserves mention is Crow’s recent evolutionary model of schizophrenia (Crow, 1997). He argues simply that the genetic basis for schizophrenia is the same as the genetic basis of language. Language, he says, emerged as a single speciation event in evolution with the lateralization of the brain. Since, according to him, schizophrenia is first and foremost a language-related dysfunction the disorder then began to occur as a result of incomplete lateralization – or what he refers to as ‘hemispheric indecision’ – in the neurodevelopment of some feature of language. The theory therefore represents a new twist on a now well-rehearsed idea that schizophrenia is the price that Homo sapiens pays for the evolution of some otherwise adaptive qualities, in this case language capacity (see also Nettle, 2001).

Manic Depression

The Unitary Psychosis Issue

Earlier we introduced the notion of unitary psychosis, the idea that schizophrenia and manic depression (or bipolar affective disorder) might simply form two broad varieties of madness. Several types of evidence have been put forward in favour of the theory (Taylor, 1992). These include the following:

- Genetic considerations, currently seen as one of the strong points of research on psychosis, do not particularly support a distinction being made between bipolar and schizophrenic psychosis. For instance, there appears to be no clear tendency for each to ‘breed true’ in families.

- At the level of symptoms there is considerable overlap between the two forms of psychosis, with what has been called no ‘point of rarity’ between them; that is to say, no evidence of a bimodal distribution when the symptoms of both manic depression and schizophrenia are plotted together (Kendell & Brockington, 1980).

- Many treatments (for example, drugs) are equally useable in schizophrenia and manic depression.

- Monitoring the clinical status of individual psychotic patients over time reveals that some may shift back and forth across the two diagnoses, or show mixtures of the symptoms of each. The last point is recognized in the psychiatric glossaries, in the existence of schizoaffective psychosis, a hybrid of schizophrenic and manic depressive features.

But what about other, more objective, evidence, for the unitary view, such as laboratory-based measures that might tap some common underlying process? Here, as well, overlap between the two conditions has been observed. Indeed, one expert commentator – whose general remarks on schizophrenia are also illuminating – was quite firmly of this opinion:

Time after time research workers have compared groups of schizophrenics and normal controls and found some difference between the two which they assumed to be a clue to the aetiology of schizophrenia, only for someone else, years later, to find the same abnormality in patients with affective disorders. Of all the dozens of biological abnormalities reported in schizophrenia in the last 50 years, none has yet proved specific to that syndrome. (Kendell, 1991)

Several quite different examples – their discovery spanning some three decades – illustrate Kendell’s point:

- Overinclusiveness – the loose associative thinking classically ascribed to schizophrenia – also occurs, probably to a greater degree, in mania (Andreasen & Powers, 1974)

- Enlarged brain ventricles – which, according to the review we quoted earlier, are the only distinguishing neuropathological feature common to schizophrenia – have also been reported in affective disorder (Pearlson et al., 1984).

- Follow-up of individuals scoring highly on the positive features of schizotypy are very likely, if they develop psychotic experiences, to show mood disorder (Chapman et al., 1994).

- Aberrations in sensory gating found in schizophrenia have also been observed in bipolar patients. This has been demonstrated by use of two measures of gating: eye tracking and pre-pulse inhibition of the startle response (Tien et al., 1996; Perry et al., 2001).

None of the above proves the unitary theory, of course, and we must not lose sight of the fact that the overall clinical manifestation of manic depression is different from that of schizophrenia. But – and this is the point – it differs no more than the range of symptoms to be found in what we should remind ourselves are properly called ‘the schizophrenias’. So that might be a reason to accept the unitary theory as the default position about the psychoses, given the absence of any good evidence to the contrary. On the other hand, expanding the boundaries of one unknown to encompass another unknown could be counterproductive. For the moment therefore the choice remains one of clinical practicality, research aim, and preferred theoretical stance.

Dimensionality of Manic Depression

Irrespective of whether or not manic depression is a subvariety of a single psychosis, the same questions can be raised about its dimensionality, as with schizophrenia. Compared with the latter, however, much less work has been carried out. This is not to say that the topic has no history. Indeed, manic depression was explicitly referred to in what was one of the first attempts to link personality to psychotic disorder: that by Kretschmer (1925), who in the early part of the last century proposed a single continuum running from schizophrenia to manic depression, with normal variants of each lying in between. On the manic depression side he used the terms ‘cycloid’ and ‘cyclothymic’ to describe the subclinical and personality equivalents. It was this theory that Eysenck revamped in order to arrive at his own dimension of psychoticism, taking in both schizophrenia and manic depression.

On the psychiatric side, some of Kretschmer’s terminology has survived in the diagnostic glossaries; to be found, for example, in the DSM as cyclothymic disorder, defined by mood swings similar to, but of a lesser degree, than those found in full bipolar affective illness. This is mostly all that the DSM has to say about dimensionality in bipolar disorder. In that regard, there is an interesting contrast with schizophrenia, with its well-recognized connections to the personality disorders. The only acknowledgement of this for manic depression in the DSM is a brief reference to Borderline Personality Disorder, a point we shall return to shortly.

Outside the official psychiatric glossaries, there have been a number of attempts to arrive at classifications that take into account associations between temperament and bipolar disorder, and hence partly address the question of one being a disposition to the other. These systems have often built upon historical typologies and terminology, making use of descriptors such as cyclothymia. Or, more recently, they have involved applying the newer temperament constructs of writers such as Cloninger, whose work we came across in chapters 3 and 4.

Studies administering the Cloninger scales to patients with affective disorder have produced rather complicated findings (see Barrantes et al., 2001). This is partly due to variations in the clinical diagnosis of samples tested – whether patients were in mania, depression, or a mixed state. But some differences in pre-morbid temperament have been found, along the lines one might expect; for example greater novelty seeking in bipolar subjects. One particular study is of interest because the authors gave the Cloninger scales to both bipolar patients and patients diagnosed as Borderline Personality Disorder (Atre-Vaidya & Hussain, 1999). Their aim was to discover whether the two types of disorder are distinct or whether they lie on a continuum. These authors concluded that the former was the case, bipolar subjects differing from borderline subjects in several ways that could not be explained as one being more severe than the other.

Despite these authors’ negative findings, the theory that BPD and manic depression are related is currently a strong idea in psychiatry. At least one eminent authority on the affective disorders has come down in its favour, proposing a ‘bipolar spectrum’ that can encompass borderline personality (Akiskal, 1996). Others, reporting on clinical evidence, have confirmed the model (Deltito et al., 2001). Further investigation is needed, conducted in the style of that currently adopted in schizotypy research, to decide whether the bipolar spectrum is an affective disorder equivalent of the schizophrenia spectrum.

Conclusions

Even from our brief coverage in this chapter, it is clear that the bulk of the research on psychosis has concentrated on its schizophrenic form and any conclusions reached here will mostly apply to that. What, in fact, can we conclude? There is certainly continuing disagreement on many issues, the consensus still being on some rather general points. No one would dispute the heterogeneity of schizophrenia and few would now wish to propose that there is one factor that can account for all of its manifestations. An accepted scenario is that the condition represents a final common path for a range of psychobiological influences that produce effects which we choose to bundle together under the single heading of ‘schizophrenia’ (meaning ‘the schizophrenias’). Otherwise, much of the origin of schizophrenia remains unexplained.

An aspect that is increasingly being emphasized is the developmental trajectory of the illness (Walker & Bollini, 2002). Schizophrenia is notable in (mostly) appearing as a disorder in adolescence or early adulthood. One argument, therefore, is that some predisposing trait or set of traits (schizotypy) lies dormant until triggered into action by hormonal and other changes occurring in adolescence. The focus of these models is very much on the neurobiology and genetics of schizophrenia and schizotypy, aspects that we, too, have stressed in this chapter. However, it would be misleading to regard constructs such as schizotypy as fixedly genetic, or of interest only in a narrow biological context. It is known, for example, that even mild early trauma can increase the tendency in adulthood to superstitious belief and magical ideation – two of the hallmarks of schizotypal thinking (Lawrence et al., 1995). This might be particularly significant in the light of evidence for a history of child abuse in many schizophrenic subjects (Greenfield et al., 1994). It is probable that future research on schizotypy will need to look more closely at how the traits associated with it emerge during development; as has been done with other dimensions of personality and temperament.

No theory can satisfactorily account for the variability found across the schizophrenia spectrum; the fact that some highly schizotypal individuals show one schizophrenic profile and others a different one. Or – and this is especially intriguing – the observation that yet others (in fact, most of those evidently at high risk) do not become clinically psychotic at all. When trying to explain these variations it is usual to fall back on generalities about the influence of modifiers, such as intelligence, gender, independently mediated personality traits, age, and environmental influences, ranging from family rearing to peri-natal brain damage. It is safe to conclude that one or more of these variables will help to shape the form of the illness, or its failure to appear.

Whichever aetiological model applies, a common problem remains for the definition of schizophrenia as a disorder. Many people who never succumb to illness nevertheless experience its positive ‘symptoms’, such as hallucinations or weird beliefs. How we interpret this apparently healthy aspect of schizophrenia defines a boundary of opinion about the interpretation of its dimensionality. Is ‘schizotypy’ a varying defect state, sometimes sufficiently compensated for so that the individual for all intents and purposes passes for normal? Or is it a genuinely adaptive trait, with several possible outcomes, one of which is schizophrenic illness? And, if we do accept the idea of a healthy form, at what point, in what circumstances, or with what combination of moderating variables do we label the state ‘illness’? Since it would appear that cognitive changes of a schizophrenic kind are not in themselves sufficient to ‘cause’ schizophrenia, it may be – as the evidence begins to suggest – that there also needs to be some drastic affective change that shapes and directs the cognitions into behaviours and experiences that are sick and maladaptive. It is perhaps no coincidence that it was the ‘splitting’ of thought and emotion that was being referred to by Bleuler when labelling these unusual disorders of mental life, ‘schizophrenia’.

It might seem an act of madness in itself for some writers to attempt to extend the mix of uncertain fact and tentative theory that still surrounds schizophrenia, to include manic depression. The dilemma is that the evidence in favour of a unitary psychosis is not insubstantial; this is true both for the clinical syndromes and at the personality level. It could therefore seem quite arbitrary – and an historical accident – that the demands for a neat classification of mental illness should have dictated the separation of two apparently overlapping expressions of insanity Yet, in the absence of a clear picture of what constitutes ‘schizophrenia/schizotypy’, is it helpful to broaden the remit even further to the larger construct, ‘psychosis/psychoticism’? Some very disparate opinions about what is actually meant by ‘psychoticism’ certainly give one pause for thought, as the following illustrates.

Crow (1986) and Eysenck (1992) are two authors who, embracing the unitary psychosis theory, have both proposed a way in which schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder may be subsumed under one heading. Both have visualized a continuum of psychosis running from the normal, through manic depression, to schizophrenia, the latter being regarded as the more severe abnormality. Crow’s interpretation is in line with his evolutionary theory of brain lateralization and language specialization: the partial or complete failure of this process results, he would argue, in a spectrum of cognitive aberration that is responsible for a range of psychotic disorders, of which the most serious is schizophrenia. Eysenck’s interpretation of the same normal–clinical continuum was totally different. He argued that the underlying trait is affective and interpersonal and has to do with empathic feelings, or lack of them, towards others. According to him the psychosis continuum starts with empathy (at the healthy end), which diminishes as one goes through criminality, affective disorder, then schizoaffective disorder, to unsocialized hostility at the schizophrenic extreme.

The contrast between the Crow and Eysenck theories could not be greater, articulating the very varied ways in which different observers have tried to grasp at the essence of some very puzzling disorders. Crow and Eysenck cannot both be right if, as seems to be the case, each is wishing to argue that his account exclusively explains psychosis. Yet, between them perhaps they too have stumbled unwittingly on the two facets of psychobiology – cognition and affect – which we need to consider if we are to advance our understanding of psychosis.