Some Basic Features

Personality disorders provide the most obvious link between the two halves of this book and the clearest example of the dimensionality between normal and abnormal. Personality disorders represent aberrations of behaviour which, superficially at least, seem to be continuous with features that in the normal range describe healthy individuality. In other words, they seem for the most part to be exaggerations of normal personality or temperamental variation. The directness of this association contrasts somewhat with the dimensionality found within the disorders to be discussed in later chapters. In those cases personality differences act more as underlying vulnerabilities to symptom-based illnesses and, where they play a part in aetiology, do so by interacting with other, precipitating factors. The connection to personality disposition is therefore more concealed than it appears to be in the personality disorders, where causation and natural individuality coincide to a greater degree. Later in the chapter we shall see that the picture is not quite as simple as that, but for the moment it suffices to emphasize the distinction between personality disorders and other forms of abnormality.

Although the general nature of personality disorder is fairly self-evident, classifying its various forms – and finding a consistent, scientific basis for doing so – has not always been easy for psychiatry. One reason for this is that writers have come to the question from many different points of view, ranging from the psychoanalytic to the neurological. It is therefore not surprising that finding a consensus on personality disorders has not been easy. There is then another, by no means trivial, reason why the personality disorder concept has always been problematic – one that needs to be mentioned right at the outset, because it pervades the whole topic.

The psychiatric label ‘personality disorder’ has always had negative overtones, a fact that has got seriously in the way of studying it objectively. It is not a neutral description of a person, or one that implies sympathy for others’ suffering – as would be the case, for example, of someone with a disabling anxiety neurosis. On the contrary, calling someone ‘personality disordered’ generally elicits annoyance, fear, distaste, condemnation, or other derogatory sentiments. This is partly because the label is frequently bracketed with ‘criminal’ or ‘antisocial’ and, among the general public at least, is often first encountered in a legal or semi-legal context. But that is not the complete explanation. There are other negative associations to disordered personality that do not have a criminal connotation, yet the attitude towards the person is still unfavourable. It is as though anything suggesting that behaviour is due to some inherent personality defect is simply regarded by others as a not very nice description of someone. Or perhaps we are just not very tolerant of any behaviour that sits outside normal limits, which is essentially how personality disorders are defined. Whatever the reason, alarmingly, this prejudice towards the temperamentally deviant is not confined to the so-called ‘lay’ person, as the study described below illustrates.

As recently as 1988 a paper appeared in the British Journal of Psychiatry entitled ‘Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike’ (Lewis & Appleby, 1988). In it the authors reported a study in which psychiatrists were asked to evaluate an hypothetical case history, the basic form of which was as follows:

… a 35-year-old man complains of feeling depressed and crying alone at home. He is worried about having a nervous breakdown and requesting hospital admission. He has thought of suicide by overdosing, having done that previously. At that time he saw a psychiatrist who gave a diagnosis of personality disorder. He has recently gone into debt and is concerned about how to repay the money.

In some forms of the case history the investigators varied the reference to the previous diagnosis given to the patient; in some versions it was stated as ‘depression’ and in others as ‘no diagnosis’. The evaluating clinicians were then presented with a series of statements asking which of these they would apply to the ‘patient’. Strikingly, when ‘personality disorder’ was the previous diagnosis many more negative statements were endorsed. These included:

- Manipulating.

- Unlikely to arouse sympathy.

- The drug overdose was attention seeking.

- Not a suicide risk.

- Condition not severe.

- Person not mentally ill.

- Difficult management problem.

- Would not want in clinic.

- A waste of NHS time.

There is an interesting corollary to the above study. In addition to changing the previous diagnosis, the investigators also altered other identifying features. In some permutations of the case history the person was referred to as a lawyer and in others as a woman, rather than a man. Generally, the evaluations were less negative if the patient was perceived to have the social status of a lawyer, but they were particularly negative if she was a woman! So, women who are not lawyers, with a diagnosis of personality disorder, are likely to have a hard time, even from their clinicians.

Personality Disorders in DSM-IV

Currently, the most commonly cited classification of the personality disorders is that contained in the DSM. This recognizes two different expressions of abnormality – symptom-based illness and disordered personality – which the DSM separates by distinguishing between Axis I and Axis II conditions. The personality disorders included under Axis II in DSM-IV are defined as referring to:

… an enduring pattern of inner experiences and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.

Table 4.1 shows the DSM classification of personality disorders, with a brief definition of each type. One point to note is the grouping of the disorders into three classes, clusters A, B, and C – colloquially known as the ‘Mad, the Bad and the Sad’! Two of these clusters reflect important themes in the characterization of the personality disorders. One (represented by Cluster B) is the strong dissocial, acting-out, or otherwise unlikeable, element which they undoubtedly do contain and which, as we have just seen, is often allowed to generalize to the personality disorders as a whole.

The other theme – summarized in Cluster A – is the connection that can be found to psychotic disorders. We shall touch upon this many times; at this point it needs comment because of the existence in personality theory of constructs like ‘psychoticism’, already encountered in the previous chapter. Although originated (by Eysenck) as a dimension to explain psychotic illnesses, psychoticism – in the sense in which Eysenck came to define and measure it (and as elaborated by Zuckerman) – is more often currently applied to certain

Table 4.1 The DSM Axis II personality disorders.

| Cluster A - Odd/eccentric (‘mad’) |

| Schizoid |

Distrust of others |

| Paranoid |

Detachment from social relationships |

| Schizotypal |

Cognitive disturbance & eccentricity |

| Cluster B - Dramatic/emotional (‘bad’) |

| Antisocial |

Disregard & violation of others’ rights |

| Borderline |

Interpersonal & emotional instability |

| Histrionic |

Attention seeking & extreme emotionality |

| Narcissistic |

Grandiosity & need for admiration |

| Cluster C - Anxious/fearful (‘sad’) |

| Avoidant |

Social inhibition & anxiety |

| Dependent |

Submissiveness & clinging behaviour |

| Obsessive-Compulsive |

Perfectionism & control |

| Plus: ‘Not otherwise specified’, for example, Passive-Aggressive |

forms of personality disorder. This itself raises an interesting question about a possible genuine overlap between the ‘mad’ and the ‘bad’. This is brought to our attention by the rather arbitrary nature of the DSM Axis II classification, portrayed in Table 4.1. Thus, ‘Borderline Personality Disorder’ – because of its own suspected connections to psychotic illness – could equally well belong in Cluster A. Again, we shall say more about that later.

The individual labels shown in Table 4.1 are in general chosen rather haphazardly and are not founded on any common, coherent theory of personality disorder. Where some theoretical basis for a particular label may be discerned, this tends to be different for different disorders, and is sometimes quite narrowly focused. The reason for this is that the various personality disorder ‘types’ arose from different clinical and scientific origins. Thus, some of the personality disorders are consciously anchored in one or other of the Axis I illnesses. Good examples are Schizoid and Schizotypal Personality Disorder (both in schizophrenia), and ‘Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder’ (in Axis I Obsessive Compulsive Disorder). Other Axis II disorders, however, have no reference in Axis I. Narcissistic Personality Disorder is a case in point. It derives from one of several personality constructs – mostly found in psychoanalytic theory – that are used to describe certain features of personality dynamics and personality development. But there is, as such, no symptom-based narcissistic illness.

Another feature to note is that even the DSM in its most recent edition does not quite avoid the negative connotations of personality disorder labelling, including occasional sexist overtones. In some cases, for example Antisocial Personality Disorder, this is unavoidable: most criminals, whether personality disordered or not, actually are not very congenial. As for gender bias, this continues to be a tricky issue. On the face of it there do seem to be genuine sex differences: for example Borderline Personality Disorder is more common in women and Antisocial Personality Disorder more common in men (Becker, 1997). Of course, this could be because clinicians simply have a lower threshold for applying such diagnoses to women (or men). There is evidence that actually that is not the case, at least for the ‘female’ disorders (Funtowicz & Widiger, 1995). But there are bound to be lingering doubts about the gender neutrality of personality disorder labels, given their generally poor image.

Certainly, some of the Axis II terminology is unfortunate. It is surprising, for example, that the descriptor ‘histrionic’ – as in Histrionic Personality Disorder – was allowed into the DSM-IV. ‘Histrionic’ – together with its effective synonym ‘hysterical’ – has a long and chequered history in psychiatric nosology and theory, as well as in everyday usage (Roy, 1982). The heyday of ‘hysteria’ was the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the diagnosis was frequently and increasingly applied, mostly to women. Indeed, as the feminist writer, Elaine Showalter (1987) points out, during that time ‘hysteria’ became the prevailing icon of the ‘madness that is woman’, and a readily available label for early female protests against the prevailing social order. But the term goes back much further than that – its Greek origin in ‘the wandering womb’ gives the game away – and ‘hysteria’ has never really thrown off its gender bias. Ironically, ‘histrionic’ has a quite different etymology – it comes from the Latin for ‘actor’ – but it sounds too similar and, in any case, it has absorbed some of the meaning of ‘hysterical’, so assuming the same derogatory connotation.

A further complication with ‘hysteria’ should be mentioned. In its nineteenth-century usage hysteria came to refer, not just to hysterical personality but also to a symptomatic illness known as conversion hysteria. Here, the individual develops a complete or partial loss of some sensory or motor function, for which there is no neurological explanation. He or she becomes blind or deaf, or paralysed, or loses sensation in a limb. Sometimes the ‘conversion’ of emotional distress (for that is what it is claimed to be) takes the form of amnesia, or a fugue state in which the individual wanders off and forgets his or her identity.

Traditionally, therefore, there have been two usages of ‘hysteria’, one referring to an illness element and the other to a personality/personality disorder element. The latter, as mentioned above, finds its nearest modern equivalent in the DSM Axis II label, Histrionic Personality Disorder. As for the illness component (in Axis I), this is confusingly spread across two different categories. The very global forms of ‘conversion’ (amnesia, fugue states, etc.) are put under the heading of ‘Dissociative Disorders’. More localized conversion reactions are bundled under ‘Somatoform Disorders’, together with other syndromes in which distress is channelled into bodily symptomatology: pain reactions, body dysmorphic disorder, and hypochondriasis. This splitting of the older, larger category of conversion hysterias is unfortunate in some ways, as the global and more localized reactions probably do share some similar underlying causal mechanism, in the form of a psychophysiological dissociation from anxiety not found in other bodily expressions of emotional distress, such as pain. (Incidentally, the ICD-10, recognizing this, does keep both local and generalized dissociative reactions under one heading.)

How do the two elements in ‘hysteria’ – personality and illness – relate to each other? There is some early work, carried out within Eysenck’s theory and referred to briefly in Chapter 2, which suggests that they are not unconnected biologically, and that people prone to dissociative disorders are more likely to show ‘hysterical’, or equivalent personality traits (Claridge, 1967). This particular question has not been researched much in recent years. But it does illustrate what in general is a hotly debated general point, viz. how we are to visualize the connection between Axis I and Axis II disorders. If, that is, there is a connection: by putting the two kinds of abnormality on separate axes, the DSM half implies that there might not be.

This relationship, if it does exist, is naturally of most interest for those personality disorders that appear to have an anchor point in Axis I and there are two ways in which we might examine the question. One procedure – by now self-evident to the reader – is to look at the presence of certain personality traits in individuals with symptom-based illnesses, in order to determine whether such characteristics are necessary precursors, or accompaniments, of the condition. Alternatively, we could go about it by studying the comorbidity between the illness and a relevant Axis II disorder. These methods are to an extent complementary, but they do not necessarily give the same answer and therefore need to be distinguished. Consider an example.

Suppose we want to find out whether individuals suffering from the Axis I illness of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) are basically obsessional people. We could do this by seeing whether they score highly in obsessional traits on a questionnaire drawn from normal personality psychology. Or we could examine a group of OCD patients to see how many may also be diagnosed as having Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD). Either way we will be led to draw certain conclusions about the characteristic personality style found in OCD. But it is important to note that, of the two methods, comorbidity analysis is the blunter strategy and, taken by itself, can lead to misleading conclusions. This is because it is much more difficult for someone to meet the criteria for a clinical disorder than to achieve high scores on a personality questionnaire. So, in our OCD example, lack of comorbidity with OCPD could cause us to conclude, wrongly, that there is no association with obsessional traits. In fact, only results from personality assessments can properly address that question.

Personality Disorders and Models of the Abnormal

In Chapter 2 we spent some time explaining different meanings of ‘dimensionality’ and how these can inform our understanding of the medical model. Here, it may be helpful to reiterate some crucial points from that discussion, as a preamble to considering the possible dimensional status of the personality disorders.

It will be recalled that we distinguished two forms of dimensionality. One is the familiar trait continuity on which normal personality structure is based. It is this that describes the healthy dimensions of personality and/or temperament and, at the same time, the corresponding predispositions to clinical states. A second form of dimensionality we described is continuity within disorder itself – and here, for the moment, we are referring to symptom-based, Axis I type, conditions. Using anxiety disorder as our example, we explained that, because illnesses can occur with different degrees of severity, symptoms themselves might form a quasi-dimension or spectrum. At the lower end of this clinical continuum, mild symptoms (for example, transient phobic reactions) might merge with, and be indistinguishable from, personality trait features (for example, chronic worrying); the boundary between these two expressions of deviation from the normal then starts to look conceptually rather blurred. So what about the personality disorders? Where do they fit into the picture?

There are two possibilities. One is that the personality disorders really are simply exaggerations of normal variation; in other words, they lie at the far end of a number of genuinely continuous personality dimensions, as extreme examples of traits. The other is that they represent attenuated forms of symptom-based illnesses and just happen to look like extreme personality variation because, as we have seen in the case of our anxiety example, mild symptoms can sometimes look like traits. Either way, phenomenologically, personality disorders seem to fall somewhere between the normal range of personality variation and symptom-based illness, showing some qualities that look like traits and some that look like symptoms. Foulds, whose pioneering ideas we quoted in Chapter 2 as one of the few writers to have made a clear distinction between ‘symptoms’ and ‘traits’, realized the dilemma. He admitted that personality-disordered individuals do pose a special problem. Such people do not seem to be ‘ill’ in the ordinary sense, but, if their behaviour is on a continuum with normal, it seems almost too extreme to be comfortable with. To deal with this ambiguity Foulds (1971) coined the idea of ‘deviant traits’.

But are we not splitting unnecessary hairs here? Does it really matter which of the above two dimensional explanations of personality disorders is correct? It does in the sense that it will influence where we look for underlying causes. If personality disorders are mild illnesses, it is by studying the aetiology of Axis I conditions that we will gain an understanding of corresponding Axis II equivalents. On the other hand, if they represent extremes of normal function then we need to study the determinants of healthy personality and then extrapolate from that into the abnormal domain. These are two different research strategies: one, the former, is more medically based, the other more personality based.

In practice, neither alternative is likely to prove universally true for all forms of personality disorder. As noted above, if we follow the DSM, in some instances there is no Axis I illness of which the personality disorder could be a mild form: we cited Narcissistic Personality Disorder as an example. But in other instances we quoted, for example Schizotypal Personality Disorder, there is; indeed, in that case there is an ongoing very vigorous, sometimes bitter, debate about which form of dimensionality applies to that particular form of personality disorder (see Chapter 9).

For any given personality disorder even the same behaviours occurring in different individuals will also differ in the way in which they can be explained. In one individual the disordered personality might be just a gross exaggeration of some otherwise healthy temperamental trait. In another person – or on closer medical examination – the same behaviour could prove to be due to clearly demonstrable brain pathology. Cases in point are the disinhibited behaviour that can follow damage to the frontal lobes and the impulsive anger sometimes associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. Here, it is no coincidence that the same brain systems are likely to be implicated in the ‘natural’ variant as in the ‘neurological’ form. Indeed, evidence collected on the latter is often used in support of theories about the biology of temperaments and, by extrapolation, their deviant forms.

Approaches to the Explanation of Personality Disorders

There have been many attempts to characterize and explain disorders of the personality, from very disparate points of view. Here we shall mention just some of them, mostly those that draw upon or connect to the ideas we have already presented. Even so, finding an orderly way of presenting the material is not easy, but the, albeit arbitrary, arrangement to be adopted is probably as useful as any. When reading through subsequent sections it may be helpful to bear in mind the following themes that run through the literature on personality disorders and around which we have loosely organized our discussion of them.

First, there are those – mostly North American – researchers who take the DSM Axis II classification at its face value and attempt in some way to go beyond it. They do so either by trying to refine the description of the personality disorders listed in the DSM and/or by offering an explanation of them. Then, there are writers who have concentrated more on a single form of personality disorder, sometimes using the DSM nomenclature and sometimes not; instead – either for theoretical or historical reasons – they have stepped outside Axis II to use another label. Lastly, some observations on the topic have come, not directly from the clinical end, but made by personality theorists extrapolating from their ideas about normal individuality. Cutting across these various approaches, explanations have differed widely, from the biological to the cognitive and taking in genetic, as well as more environmental, perspectives.

Five-Factor Theory and Axis II

A prominent part of the current literature on personality and personality disorders (as portrayed in the DSM) concerns the application of the Five-factor theory outlined in the previous chapter. Indeed, the contribution of Five-factor theorists to abnormal psychology has mostly been confined to that group of disorders. This fact has been recognized by the authors of the DSM-IV, who go as far as to cite the work as an example of attempts to identify fundamental dimensions of personality that could account for the Axis II conditions. They do so in a short section devoted to the issue raised earlier, of whether the personality disorders are best viewed as dimensional with normal personality or dimensional with Axis I illnesses. They rather sit on a conservative fence in the matter, merely saying that dimensional models are ‘under investigation’.

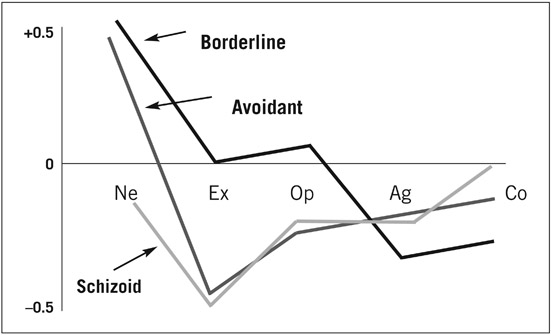

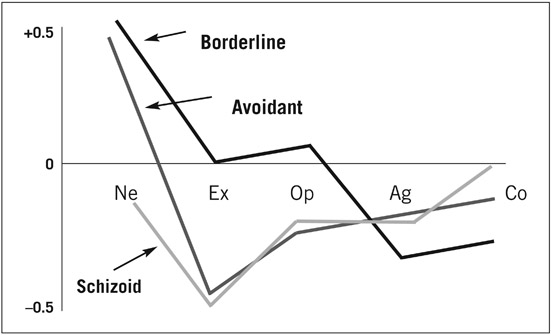

A variety of approaches have been taken to the topic. Some research has used factor analysis to see how accurately the dimensions in Five-factor theory map onto clinical features of the Axis II disorders, assessed independently by another set of scales. The authors of one such study concluded that there was very good correspondence between the two systems (Schroeder et al., 1992). Although such findings are statistically convincing, they seem less satisfying when one examines the Axis II disorders individually, in terms of the profiles they show across the dimensions of Five-factor theory. Figure 4.1 summarizes the findings for three representative personality disorders – Schizoid, Borderline, and Avoidant – belonging, respectively, to clusters A, B, and C in the DSM-IV (Widiger & Costa, 1994).

It is clear from the diagram that some differences are to be observed between the three personality disorders shown there. Particularly interesting is the rather low Neuroticism of the Schizoid group. This is an exception to the usually very high Neuroticism found in clinical conditions of almost any kind, including the other two personality disorders shown in the figure. But it does fit in with the absence of emotional responsiveness found in schizoid individuals who tend, overtly at least, to seem rather unfeeling. In other respects, however, it has to be said that profiles of this kind tell us little that we do not already know. For example, it is not too surprising that both schizoid and avoidant forms of personality disorder are found in highly introverted personalities. Or that people with Borderline Personality Disorder are low on Agreeableness; we saw earlier that some individuals with extreme personality traits are occasionally not very nice.

At least it may be said that Five-factor research establishes some validity for

Figure 4.1 Five-factor profiles for three personality disorders. (Ne = Neuroticism; Ex = Extraversion; Op = Openness; Ag = Agreeableness; Co = Conscienciousness.)

the Axis II classification of personality disorders, by pointing to understandable differences on major personality dimensions that have been established independently of the DSM. Unfortunately, as noted in Chapter 3, Five-factor theory is weak on the ‘causal’ side of things, not having a well-worked out account of the underlying determinants, for example biology, of its dimensions. Mostly, the question of aetiology is referred to in discussions about the possible genetic influences on the Five-factor dimensions. This is fine in its own way but it offers nothing unique that other approaches are not also addressing.

Also, research on healthy subjects of the heritability of normal personality traits (whether or not Five-factor theory inspired) is only one strategy for trying to unravel the complex genetics of personality disorders. Other methods involve direct study of personality disordered individuals, or trying to extrapolate from what is known about the genetics of related Axis I disorders. Taking all this information into account, the findings to date are rather mixed (Nigg & Goldsmith, 1994). Some Axis II disorders – mostly in Cluster A – do seem to have strong heritability. The evidence for others, including – surprisingly perhaps – Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Disorder, is more equivocal.

Some of the ambiguity here stems partly from weaknesses in the definition and delineation of the personality disorders themselves. Because of the high comorbidity between certain Axis II diagnoses, it is unlikely that very specific genetic effects will be found for some disorders; that is, effects that cannot be assigned to some common set of personality traits, or temperament dimension. An example is Histrionic Personality Disorder which overlaps considerably with Borderline Personality Disorder and which might share with it a strongly inherited element of, say, impulsivity.

Cloninger Revisited

Like the Five-factor theorists, Cloninger has also proposed a comprehensive account of normal personality. And, in the clinical sphere, he too has applied his ideas especially to personality disorders. However, compared with Five-factor theory, Cloninger’s account is altogether more searching, in two respects. First, it makes the important distinction between temperament and character, each being broken down into several dimensions, which it is claimed interact to produce differences in healthy and unhealthy personality structure and functioning. Second, Cloninger offers a well-defined, albeit speculative, biological (including genetic) explanation for the temperamental differences, along lines that chime with other mainstream personality theories of a similar type.

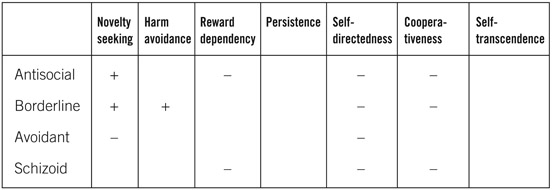

Applying his theory to Axis II, Cloninger argues that the basic tendencies towards the various personality disorders lie in differences among the four, substantially inherited, temperament dimensions: novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependency, and persistence. The expression of these dispositions can be, and usually is, healthy; but where the temperamental traits are extreme, or circumstances conspire to distort them, a personality disorder will result. This outcome is seen to depend on the three character dispositions of self-directedness, co-operativeness, and self-transcendence (Svrakic et al., 1993).

Cloninger established profiles for all of the Axis II personality disorders by use of his Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (Cloninger et al., 1994). Four examples are illustrated in Table 4.1: the three shown earlier in Figure 4.1 – Avoidant, Borderline, and Schizoid – to which we have added, for interest, Antisocial Personality Disorder (Table 4.2). Three points are worth noting.

The first concerns scores on Cloninger’s three character dimensions. All four of the disorders shown in Table 4.2 are virtually identical on these factors and

Table 4.2 Profiles for four personality disorders (Cloninger).

fairly equally deviant on two of them: self-directedness and co-operativeness. Indeed, looking at Cloninger’s full set of profiles it is evident that all of the Axis II disorders are very similar on the character dimensions. What this signifies is that people with personality disorders tend, in general, to be rather unco-operative and to lack self-directedness or, as Cloninger himself puts it: ‘…have difficulty accepting responsibility, setting meaningful goals, resourcefully meeting challenges, accepting limitations, and disciplining their habits to be congruent with their goals and values’. This combination of traits probably helps to explain why most people with personality disorders are not very well-liked.

The second point to note about Table 4.2 concerns the variation on the temperament dimensions. It is evident that antisocials are very high in ‘novelty seeking’, as befits their impulsive behaviour and constant seeking of positive reinforcers. In contrast, avoidants are very low in this, but especially high in ‘harm avoidance’, consistent with their high anxiety. One other interesting feature is the profile of schizoid subjects, whose main temperamental feature is low ‘reward dependency’; appropriately, they find little satisfaction in social stimulation. Taken together with the unusually low Neuroticism found in the Five-factor profile, this suggests that schizoid individuals are, as always thought, a bit odd – they do not even conform to the norms of disordered personality!

The conclusion from Cloninger’s work, then, is that the factors determining which personality disorder an individual shows are almost entirely temperamental in nature, owing to differences in basic biological drives or tendencies of the kind outlined in the previous chapter. To the extent that these characteristics are inherited it may therefore be said that the deviant behaviours normally descriptive of personality disorder are under some genetic control. But, if we follow Cloninger, the actual expression of these dispositions will be shaped by what he refers to as his character dimensions. These, according to his analysis, are flawed in a very similar way and to a similar degree, across different disorders.

The Work of Millon

A writer whom we have not mentioned before but one who has made a major contribution to the literature on personality disorders is Millon (Millon & Davis, 2000). In the context of this book Millon is unusual for two reasons. First, his ideas about normal personality have been very much driven by his attempts to account for its disorders rather than vice versa. And, second, his theorizing has been rather outside the mainstream thinking that we are mostly drawing upon here. Despite the fact that Millon’s work has not had great impact in general personality psychology, it has had considerable influence on clinicians in the field of personality disorders. Among other things, Millon is the originator of a widely used psychometric procedure for assessing personality disorder features in clinical and community samples: the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-III) (Millon et al., 1996).

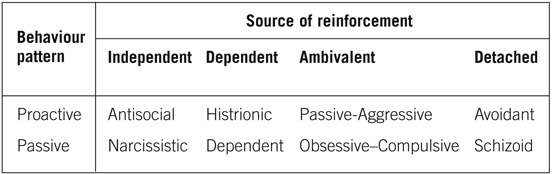

Millon’s stance on the relationship between normal and abnormal personality consists of what he calls a ‘biosocial learning approach’. In its very basic form this extrapolates from a classification of normal personality patterns to dysfunctional forms that constitute the Axis II disorders. The essential features of the theory are shown in Table 4.3. According to Millon normal personality differences are accounted for, or reflected in, two influences: an individual’s preferred source of reinforcement, and an instrumental behaviour pattern in relation to that. Thus, individuals may be proactive or passive in their behaviour and find satisfying reinforcement in one of four ways: independent, dependent, ambivalent, and detached from others. This matrix gives rise to a series of personality patterns which, in their abnormal form, are seen in the various Axis II disorders (see Table 4.3).

Table 4.3 Personality disorders: Millon’s theory.

One further feature of Millon’s analysis to be noted is that it proposes a continuum of severity within the personality disorders. Thus, apart from Schizoid, the Cluster A conditions – Borderline, Schizotypal, and Paranoid – are perceived to be more severe expressions of the same normal personality patterns responsible for milder forms. Although Millon provides no experimental evidence for his theory – his ideas are largely based on clinical observation – the implied dimensionality between personality disorders and psychotic illness does chime with a theme in this topic already mentioned several times, and to which we shall return.

Beck’s Cognitive Approach

Beck is most celebrated for his writings on depression. Less well-known are his clinical speculations about personality disorders (Beck et al., 1990). As with depression, Beck concentrates on the cognitive approach, inspired by an interest in applying cognitive behaviour therapy to Axis II disorders. His view of the latter is that they represent deviant personality patterns defined by abnormalities in three areas of function: cognition, emotion, and motivation.

The resulting mental schemata to which these abnormalities give rise differ across the various disorders and may be observed clinically in four ways:

- The view of the self.

- The view of others.

- The predominant belief system.

- The main strategy for dealing with the world.

Table 4.4 summarizes how, according to Beck, the main Axis II disorders differ in these four respects. The features shown are fairly self-evident when compared with the DSM and other clinical descriptions of the personality disorders. But they do help to supplement these and are meant to provide a focus for therapeutic efforts to bring about change in clients with personality disorders.

Table 4.4 Cognitive biases in personality disorders (Beck).

| Paranoid |

Motives are suspect; be on guard; do not trust |

| Schizoid |

Others are unrewarding, relationships undesirable |

| Antisocial |

Entitled to break rules; others are wimps |

| Histrionic |

People are there to serve and admire me |

| Narcissistic |

I am special and deserve special rules |

| Avoidant-dependent |

If people know the real me they will reject me; need people to survive and be happy |

| Obsessive-compulsive |

I know what is best; details are crucial |

In his discussion of personality disorders Beck raises the inevitable question of where dysfunctional belief systems of the kind shown in Table 4.4 come from. Unfortunately, he fails to address the issue beyond vague statements about ‘nature–nurture interaction’ and individuals being predisposed ‘by nature’ to overreact in childhood to certain negative life events that could lead to the distorted cognitions and behaviours associated with the various personality disorders. Beyond this, no attempt is made to specify, for example, particular biological tendencies or mechanisms that could account for the different disorders. Nevertheless, his insightful descriptions of these could provide a useful starting-point, at the clinical end, for trying to integrate psychological and biological approaches to the personality disorders.

Particular Personality Disorders

The disorders we have introduced in this chapter differ in importance from one another in several respects: their status as significant stand-alone forms of abnormal behaviour; their relatedness to symptom-based illnesses; and the extent to which studying them may contribute to our understanding of psychological disorders in general. Some have received comparatively little attention. Histrionic Personality Disorder is a case in point. Most of what is known about Histrionic Personality Disorder comes from its overlap with other disorders in the same Axis II cluster or via its historical association with hysteria and hysterical personality. A rather different example is Narcissistic Personality Disorder. A great deal is still written about narcissism, but most research on it is not very empirical; this, coupled with a lack of connection to any specific Axis I illness, leaves it rather stranded from mainstream theory in psychiatry and abnormal psychology. In contrast, four personality disorders stand out as being sufficiently different from the remainder to have become the focus for more substantial research and the collecting point for some important ideas in the field.

Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) is unusual in showing relatively low comorbidity with other Axis II disorders. Its relationship, or not, to Axis I Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) also raises interesting questions. How far do OCD and OCPD share common underlying personality traits? If not, is this because OCD is itself a heterogeneous condition? What light can the study of OCPD, including its genetics, throw on this matter?

Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD) – and its associated personality dimensions – have an even more strategic role in shaping our understanding of Axis I illnesses, notably schizophrenia, but others as well. The research effort there has been considerable and is one of the best examples of the convergence of ideas stemming from studies of normal personality, personality disorder, and symptom-based illness.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) is important, not least because it sits at the traditional centre of the personality disorder construct, representing that part – the dislikeable criminal element – with which most people associate the label. Unfortunate though that is, by being generalized to personality disorders as a whole, it is obviously highly relevant to the understanding of APD itself. APD has inspired a considerable amount of research, although, as explained below, much of the definitive research has been carried out under a different label.

Fourth, Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is, in a sense, the archetype of ‘disordered personality’, encompassing most of the defining features of the latter. These include chaotic personality dynamics, a probable association to psychotic illness, unlikeability, and yet, despite these things, a recognizable dimensionality with normal behaviour. The term ‘borderline’ also has a fascinating history, appearing in several guises in psychiatry. For that reason it has attracted a wide range of explanations from very different research perspectives.

In the rest of this chapter we shall consider only two of the personality disorders just mentioned: APD and BPD. The other two – OCPD and SPD – are best considered in the chapters devoted to the corresponding Axis I disorders: OCD in Chapter 6 and schizophrenia in Chapter 9, respectively.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (Psychopathy)

Antisocial behaviour stems from many causes, both individual and situational, both biological and cultural. People transgress the moral or written rules for all sorts of reasons. At the more trivial end of the spectrum a momentary impulsive need may tempt a perfectly average citizen to steal his neighbour’s pen, and most of the population drives some of the time some miles per hour above the speed limit. As for more serious law-breaking, much of this can be traced to poverty, social deprivation, unemployment, poor education, or merely living in a criminal subculture: if theft or violence is the everyday norm, unsurprisingly, people learn to steal and hit each other.

However, here we are more concerned with the personality and clinical features which – over and above those other causes – contribute to some kinds of antisocial behaviour; in other words, characteristics that can supposedly be found in people who are regarded as inherently antisocial individuals. In the current DSM Axis II terminology this cluster of traits is labelled Antisocial Personality Disorder. However, for the purpose of our discussion here, we shall abandon the DSM and the APD construct, in favour of ‘psychopathy’ and ‘psychopathic personality’. The reason for doing this is that the most systematic research has been done, and the most coherent set of ideas has been developed, around the concept of ‘psychopathy’, rather than APD. Yet, having said that, we also need to define our terms even more precisely.

The label ‘psychopath’ itself has suffered greatly in the hands of psychiatrists and psychologists, who over the years have defined and re-defined and subcategorized it in various ways. The main division that we need to be concerned about here is the distinction between primary and secondary psychopathy. As the name implies, the latter refers to antisocial behaviours that are consequent upon or can be accounted for by some other event or feature of the individual. This could include subcultural factors, immediate or remote life events or, on the personal front, associated mental illness that triggers or potentiates the antisocial act. In contrast, primary psychopathy refers to the idea that there are some individuals whose criminality, or other antisocial behaviour, can be very largely explained by their personality or temperamental make-up.

Cleckley’s clinical description The best clinically based accounts of the psychopathic personality are to be found in Cleckley’s classic book, The Mask of Sanity (Cleckley, 1976). In some of the most colourful prose in the psychiatric literature, and with detailed case histories, Cleckley paints a composite picture of the psychopath which, for those who have come face to face with such individuals, will be instantly recognizable. He (most, although not all, psychopaths are male) is the sort of egocentric person who, whilst sometimes superficially charming and plausible, is devious, unreliable and insincere; who lacks guilt, shame and empathy for others; who constantly seeks to relieve boredom; and whose poor judgement is coupled with a chronic failure to learn from experience. It is difficult to do justice to the richness of Cleckley’s characterizations, but the following extract captures some of the quality of his text and of the psychopathic individuals he is describing:

In a world where tedium demands that the situation be enlivened by pranks that bring censure, nagging, nights in the local jail, and irritating duns about unpaid bills, it can well be imagined that the psychopath finds causes for vexation and impulses towards reprisal. Few, if any, of the scruples that in the ordinary man might oppose and control such impulses seem to influence him. Unable to realize what it meant to his wife when he was discovered in the cellar in flagrante delicto with the cook, he is likely to be put out considerably by her reactions to this … His father, from the patient’s point of view, lacks humor and does not understand things. The old man could easily take a different attitude about having had to make good those last three little old cheques written by the son. Nor is there any sense in raising so much hell because he took that dilapidated old Chevrolet for this trip to Memphis. What if he did forget to tell the old man he was going to take it? It wouldn’t hurt him to go to the office on the bus for a few days. How was he (the patient) to know the fellows were going to clean him out at stud or that the bitch of a waitress at the Frolic Spot would get so nasty about money? What else could he do but sell the antiquated buggy? If the old man weren’t so parsimonious he’d want to get a new car anyway! (Cleckley, 1976; 390)

Cleckley’s insight into the psychology of the psychopath led him to several interesting conclusions. For one thing Cleckley was not very convinced by the idea that the primary psychopath’s behaviour could be traced, in any significant degree, to experiences within the family. He noted that a very large percentage of the psychopaths he saw came from backgrounds that appeared conducive to happy development and good adjustment. And, by the same token, where early incidents could be identified that might have explained the later antisocial behaviour, similar experiences could frequently be demonstrated in the backgrounds of many perfectly happy, successful adults. Cleckley’s preference was for a constitutional explanation, a strong argument in favour being the ‘black sheep’ phenomenon, viz. the sharp contrast in behaviour that could be observed between the psychopath and the other healthy, adjusted members of his family.

Second, addressing the cognitive functioning of psychopaths, Cleckley noticed that a lack of intelligence, in the ordinary sense, did not appear to be the problem; on the contrary, many of the patients he saw were quite bright. The difficulty was more subtle. It consisted, he said, of some flaw in semantic processing whereby elaboration of the meaning, especially the emotional meaning, of words is poorly developed. As Cleckley put it, the psychopath:

… cannot be taught awareness of significance which he fails to feel. He can learn to use the ordinary words and, if he is very clever, even extraordinarily vivid and eloquent words which signify these matters to other people. He will also learn to reproduce appropriately all the pantomime of feeling; but, as Sherrington said of the decerebrate animal, the feeling itself does not come to pass. (Cleckley, 1976; 374)

The same point was made elsewhere in the now famous description of the psychopath as someone who ‘… knows the words, but not the music’ (Johns & Quay, 1962).

A third, fascinating, insight by Cleckley concerned the manifestation of psychopathic traits in everyday life, outside a criminal or overtly antisocial context. He devotes several sections of his book to ‘The psychopath as businessman … as man of the world … as gentleman … and as scientist, physician – and psychiatrist’. The dimensional message is plain and should not surprise us. Like other personality characteristics that have the potential for disorder, given the opportunity those found in the psychopath can and do lead to success, often in high places!

The work of Hare Cleckley’s writings provided the inspiration for a long, systematic programme of studying the primary psychopath by Hare and colleagues (Hare, 1986, 1993; Cooke et al., 1998). This work has had two strands of research, developed partly in parallel.

Table 4.5 Psychopathy checklist (Hare).

| Factor 1: Personal & emotional traits |

| Glibness/superficial charm |

| Grandiose sense of self-worth |

| Pathological lying |

| Manipulative/conning |

| Lack of remorse or guilt |

| Lack of empathy |

| Shallow affect |

| Factor 2: Lifestyle |

| Need for stimulation |

| Parasitic lifestyle |

| Early behavioural problems |

| Lack of realistic goals |

| Impulsive behaviour |

| Poor probation or parole risk |

The first involved the construction of an instrument for measuring psychopathic features, largely based on Cleckley’s description. This – in its current form the Revised Psychopathy Checklist (PCL-R) – is listed in Table 4.5. A point to note about the checklist is that factor analysis revealed two different types of item (Hare et al., 1990). One concerns psychopathic personality traits; the other lifestyle habits. Although the two factors are highly correlated, Hare considers it desirable to retain the distinction between them because, according to him, they relate differently to other variables. Most important to note here is that the Axis II diagnosis of APD correlates only with the second, lifestyle, factor, showing no relationship to the personality traits measured by Factor I. Hare is probably right, therefore, to suggest that one needs to take both aspects into account, in order to assess psychopathy properly.

The other strand in Hare’s research programme has been experimental studies of criminals, examining various theories of psychopathic behaviour. The standard methodology has been to compare primary psychopaths, selected by one or other version of the Hare checklist, with non-psychopathic criminals. The research has spanned several decades. Consequently, a wide range of experimental paradigms has been tested over the years, from behavioural to neurocognitive (see Table 4.6). When evaluating these different explanations it is important to note that all of them, including the early ones, have a place in accounting for some facet of psychopathic behaviour.

Table 4.6 Primary psychopathy: possible explanations (Hare).

| Physiological arousal |

| Arousal deficiency |

| Low anxiety |

| Poor anticipation of punishment |

| Sensory modulation |

| Efficient sensory gating |

| ‘Tuning out’ of threat |

| Neurocognitive functioning |

| Weak lateralization for language |

| Failure to connect to affective significance of language |

The earliest formulations made use of the idea that psychopaths apparently fail to avoid punishment when tested in an aversive conditioning situation. This seemed to be related to the fact that psychopaths have a steep temporal gradient of fear arousal. That is to say, they do not readily anticipate the onset of an impending punishment; as measured in the laboratory by their autonomic (skin conductance) response to an expected electric shock. A middle phase of Hare’s research shifted to a more ‘cognitive’ explanation, when it was noticed that, contrary to prediction, primary psychopaths showed an unusual pattern of physiological response to stress. Although in general physiologically rather unresponsive, their heart rates tended, paradoxically, to go up when stressed. Hare argued, in line with some current thinking about the interpretation of such effects, that psychopaths have an efficient attentional gating mechanism when under threat. In other words, when faced with something that is potentially disturbing, their brains are quick to react with: ‘I don’t like the look of that; I’ll just ignore it, not think about it’. This ‘dissociation’ from stress – which is indeed known to cause the heart rate to go up – might also explain why psychopaths do not learn from experiences that involve punishment. Most of the time they are not even paying attention.

Hare’s later explanations of psychopathy have been more thoroughly neurocognitive and picked up on the ’know the words but not the music’ theme referred to earlier. In one study, testing this idea, EEG responses to emotional and non-emotional words were measured in primary psychopaths and non-psychopathic criminals. It was predicted that because psychopaths would make inefficient use of the affective information contained in some of the words, there would be less difference in their EEG reactions to the two kind of stimuli, compared with control subjects. This proved to be the case (Williamson et al., 1991). Then, in their most recent study of this same emotional processing deficit, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to study the brain activity of psychopaths whilst performing an affective memory task. It was found that, compared with control subjects, psychopaths showed reduced activity in the limbic structures (amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus) presumed necessary for the processing of emotional stimuli (Kiehl et al., 2001).

The work of Blair Research that follows almost directly from that by Hare and his colleagues is the recent elaboration of the neurocognitive perspective on primary psychopathy by Blair. Blair’s theory attempts to provide a neurological explanation of two related aspects of the psychopath’s behaviour: his deficiency in emotional processing (empathy) and his poor control over aggression (Blair, 1995).

The core idea in Blair’s thinking is the notion of a Violence Inhibition Mechanism (VIM). This draws upon the work of ethologists and the suggestion that social animals possess mechanisms that suppress attack responses in the presence of cues of submission from their foe; for example an aggressive dog ceases to fight if its opponent bares its throat. Blair’s proposal is that a similar mechanism exists in the human, but is absent or functions poorly in the primary psychopath. Blair reports two kinds of experiment – both conducted with adult psychopaths selected on the basis of the Hare checklist – which he claims support his theory:

- It was argued that if psychopaths have a weak VIM, they should be abnormal in their processing of others’ emotions. This was tested by asking psychopaths (and non-psychopathic control subjects) to attribute emotions to characters in stories displaying various positive or negative affects. It was found that, in response to ‘guilt stories’, psychopaths were significantly less likely to state guilt as the dominant theme; the emotion tended, instead, to be happiness or indifference (Blair et al., 1995).

- Along the same lines, it was predicted that psychopaths should show a reduced physiological reaction to signs of, specifically, distress in others. This was tested by comparing psychopaths and nonpsychopaths in their skin conductance responses to slides illustrating scenes eliciting different emotional cues. Although not differing for threatening and neutral stimuli, psychopaths showed significant reduced response to cues of distress (Blair et al., 1997)

In other experiments, similar effects, using the same methodology, were found in children selected for psychopathic tendencies on the basis of another of the Hare screening procedures (Blair, 1999).

Blair’s conclusions from these studies are that a frail VIM could be an inherent biological feature of the antisocial individual, influencing moral development from an early age. Further speculating on the possible neurology of this mechanism, he proposes that the amygdala might play a central role, given its known function in emotion, especially the processing of facial affect. Once more, therefore, some deficiency in limbic system functioning seems to emerge as a crucial feature of the biology of those forms of antisocial behaviour where the deviation may be ascribed to personality differences.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

The ‘borderline’ construct The history of BPD is as confused as those suffering from the disorder itself. The first point to note is that ‘borderline’ (and the terminology surrounding it) is almost exclusively of American origin, stemming from certain trends of thought in mid-twentieth century North American psychiatry. ‘Borderline’ emerged there partly as a way of articulating the dimensionality of psychotic disorders, in particular schizophrenia. Not, we should add, dimensionality in precisely the way we are presenting that idea here; rather, more to reflect the very broad, socio-psychological view of schizophrenia that prevailed in the USA through the 1950s and 1960s. During that period clinical labels were in use which expressed this borderline view, such as ‘latent schizophrenia’, ‘pseudoneurotic schizophrenia’, and indeed ‘borderline schizophrenia’.

An important influence there – stronger than in the European psychiatry of the time – was psychoanalysis and, in some usages of the term, ‘borderline’ was occasionally defined therapeutically. Borderline patients came to be seen as individuals who, although not manifestly psychotic, were too ill to respond well to conventional forms of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Furthermore, in some writings, discussion of ‘borderline’ became detached from formal issues about connections to psychosis. There was, instead, a shift towards trying to characterize the clinical features and underlying dynamics of this peculiar, pervasively chaotic psychological disorder. It was this trend in the study of ‘borderline’ that brought the topic more into the personality disorders domain; running by this time in parallel with debates elsewhere about the dimensionality of psychosis and the schizophrenia spectrum (Claridge, 1995).

‘Borderline’ in the DSM It was not until the 1980s – with the first major revision of the DSM – that a degree of order was brought into the clinical and diagnostic confusion surrounding the ‘borderline’ construct. With only minor revisions in subsequent editions, DSM-III recognized two usages of ‘borderline’, now enshrined in Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD) and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). Although the two forms show considerable overlap, this dichotomy kept separate the dual themes in the history of the construct: the personality disorder aspect and the connection to psychosis. One rather artificial consequence of this division, as noted earlier, is that SPD and BPD are assigned to different Axis II clusters.

Table 4.7 summarizes the current criteria for BPD, as defined in the DSM-IV. The notable features, which help us to understand the difficulties – in more than one sense – of the disorder, are to be found in the characteristic combination of outrageous behaviours, erratic social interactions, and unregulated emotion which cause the sufferer to veer constantly out of control, yet mostly, and remarkably, not quite enough to break down into frank psychosis. All of this adds up to a picture of chronic derangement neatly captured in one classic description of borderline patients: that they are ‘stable in their instability’!

Table 4.7 Borderline Personality Disorder - the DSM criteria.

| Frantic efforts to avoid abandonment |

| Unstable and intense interpersonal relationships |

| Unstable self-image |

| Impulsivity (in, for example, sex, spending, substance abuse) |

| Suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviour |

| Marked reactivity and instability of mood |

| Chronic feelings of emptiness |

| Inappropriate intense anger |

| Dissociative symptoms |

Before considering attempts to explain BPD, it is worth drawing attention to some prevailing themes in the literature on the disorder, especially to compare it with its twin disorder, SPD. As we shall see in Chapter 9, the latter has been the subject of considerable experimental research. This has not been so of BPD where, until quite recently, the focus for research has been somewhat different. Perhaps reflecting the way the BPD form of ‘borderline’ evolved, the emphasis has tended to be on more clinical concerns. Two topics in particular have been of interest.

The first is the comorbidity of BPD with other psychological disorders, especially those to which borderline traits and borderline personality dynamics might be expected to make an individual susceptible. Obvious candidates here are depression, drug abuse, and eating disorders of the bulimic type. Although personality disorders in general are frequently comorbid with these Axis I illnesses, the association is especially strong for BPD (Oldham et al., 1995; Hudziak, et al., 1996).

A second focus in BPD research has been on the role of sexual abuse in its aetiology. This has been extensively studied and there is indeed evidence that sexual abuse can make a significant contribution to the aetiology of the disorder (Zanarini et al., 1997). Having said that, to place sole emphasis on sexual abuse is too limiting. Sexual abuse almost always occurs in the context of more general neglect, which in any case is common in most forms of psychological disorder, both Axis II and Axis I (Wexler et al., 1997). As with every other disorder, the actual outcome for the individual will result from an interaction between the traumatic experience and those personality and temperamental traits that influence how he or she reacts to it. One writer who has been prominent in trying to bring these various sources together for BPD is Paris (1994).

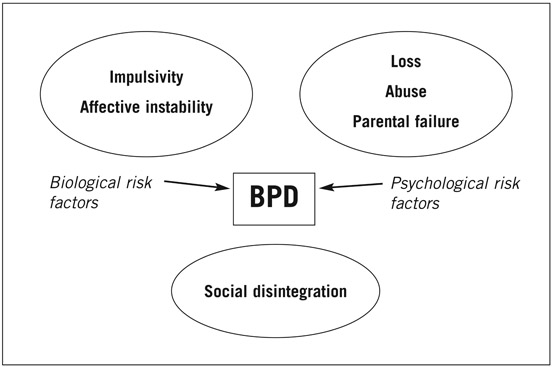

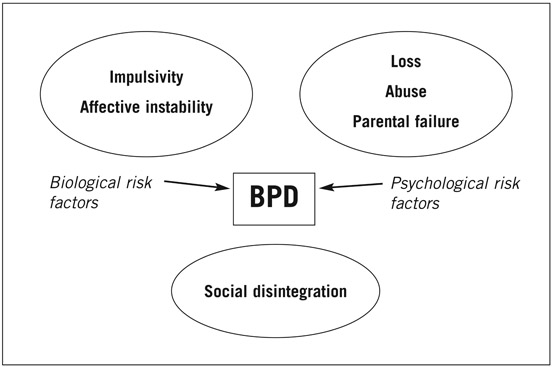

Paris’ biopsychosocial model of BPD The reader should be wary of multi-stemmed adjectives, such as ‘biopsychosocial’ (and its several variants), since they generally serve to gloss over a failure to understand the constituent parts or the interactions between them. However, Paris’ model for BPD is an exception. At the very least, it provides a useful framework for visualizing how the different influences on BPD might work together to produce the disorder. It is also a good illustration of how, as a matter of general principle, psychological disorders mostly come about.

The model is reproduced in Figure 4.2. At the biological level, Paris identifies two features which it is generally agreed are major risk factors for BPD, viz. impulsivity and instability of mood. He argues – again from some existing evidence – that certain, otherwise healthy, temperamental traits may be precursors for these risk factors.

Referring to the EAS typology described in the previous chapter, Paris suggests that potential borderlines are likely to be high in sociability, activity,

Figure 4.2 Paris’s amplification model of Borderline Personality Disorder.

and emotionality. Normally, he notes, such people will be engaging, socially active, if slightly demanding, people who like doing things on the spur of the moment. But, he goes on:

In the presence of psychological risk factors, such as trauma, loss, and parental failure, these characteristics could become amplified. Emotional reactions could become labile and dysphoric. If activity were used inappropriately to cope with dyphoria, it could become impulsive acting out. Substances, sexual activity, or chaotic interpersonal relationships could be used to damp down dysphoria. Dysphoria and impulsive action would reinforce each other, and a feedback loop would develop. The pattern would begin to resemble BPD. (Paris, 1994; 95)

A significant point here is Paris’ use of the notion of amplification, introduced in Chapter 2, the idea that stress will exaggerate pre-existing traits into a pathological form. This provides a useful way of envisaging the interface between predisposition and environment, and the way they interact along a developmental trajectory. Paris makes two other important points arising from his model.

The first concerns the role of what in Figure 4.2 Paris calls ‘psychological risk factors’. Here, he notes that the psychological stressors that amplify predisposing traits into clinical risk may not be all that specific. Notwithstanding the fact that childhood abuse, as we have mentioned, does seem to be quite frequent in BPD, a range of traumatic events could act along several pathways towards a final common outcome of disorder.

Paris’ second point harks back to an observation in the previous chapter, that individuals to some extent create their own environments; or, in the language of genetics, that much of the early environmental influence on personality is of the within-family variety, unique to the individual. Paris takes up this theme in commenting that the abnormal traits thought to predispose to BPD might elicit negative responses from parents. Thus, very impulsive, affectively labile children might be seen as ‘difficult’ and therefore be more likely to face parental rejection and abuse. A further layer to this interaction could come from the presence of psychopathology in parents themselves, acting in a synergistic fashion to enhance the child’s clinical risk for later disorder. Illustrating this effect is a retrospective study of the psychiatric status of the parents of borderline patients during the formative years of their children. Evidence was found that the parents of future borderline individuals showed a high incidence of several psychiatric conditions, especially depression and anxiety, but also substance abuse and even psychotic disorder. Not surprisingly, personality disorder was also common in the parents (Shachnow et al., 1997).

Susceptibility to BPD In the model of BPD just described, Paris quite rightly draws attention to the interacting contribution of many factors, to both susceptibility and clinical presentation. In this he emphasizes the crucial importance of the underlying personality as a probably necessary precursor in most cases. He notes, for example, that given the same psychological and social stresses, individuals of different temperament would react differently, leading to a different personality disorder:

‘An introverted child, in contrast, when faced with loss, trauma, or neglect, will withdraw … Amplify this process still further and the behaviours will begin to correspond to the criteria for personality disorders of the dependent and avoidant types.’

So, what more can we say about the nature and determinants of the inherent traits that help to steer the individual towards BPD, rather than some other personality disorder? On the genetics front, the evidence is actually rather mixed when the BPD diagnosis has been used as the phenotype for investigation (Nigg & Goldsmith, 1994). But there is some support for a familial connection; the fact that it is not stronger might be yet another example of the bluntness of this methodology as a research strategy. A more convincing database to draw upon is that on normal temperament, reviewed in the previous chapter; there we saw that genetic influences can play a major rôle in some traits that might be significant precursors of BPD. Although the evidence on impulsivity – strongly backed by Paris – seems ambiguous, rough equivalents, such as Cloninger’s novelty seeking, fare better. Borderline individuals certainly score highly on that dimension, as we can see by looking back at Table 4.2 (page 70). Curiously, however, borderline individuals also rated highly on harm avoidance, which seems to be the opposite of novelty seeking. In this important respect they differed from antisocial individuals, with whom they are frequently compared.

This dual weighting of BPD on two temperament dimensions that are normally regarded as incompatible – harm avoidance and novelty seeking – could merely reflect the heterogeneity of the diagnostic category. Or, it could be a genuine sign of the contradictory – literally ambivalent – emotional style of borderline individuals. This would connect to another theme in the borderline literature: the close similarity between Borderline Personality Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Diagnostically, PTSD is a different condition, classified in the DSM among the anxiety disorders on Axis I. But it has been argued that, where trauma plays a part in the aetiology of BPD, there may be an element of anxiety in common with PTSD. One proposal, pursuing the neurochemistry of this idea, is that both disorders share noradrenergically mediated hypersensitivity to stimulation – trauma induced, but in PTSD also partly due to pre-existing temperamental disposition. Borderline individuals differ, it is suggested, in their serotonin-mediated impulsivity which causes them to deal with their dysphoria by indulging in aggressive, self-damaging or otherwise risky acts (Figueroa & Silk, 1997). (c.f. here the recent evidence quoted earlier (page 57) on the possible genetics of Novelty seeking and Harm avoidance.)

Experimental research, for example neuropsychological, that might help to illuminate some of these issues, and help to define the borderline personality more precisely, is still in its relative infancy, There is, however, one small group of studies worth noting, examining emotional processing in borderline personality, a behaviour clearly of considerable relevance to the understanding of the disorder. (Interest in the same topic in relation to primary psychopathy is no coincidence, given the suggestion that BPD represents its female equivalent.)

The studies in question mostly use a similar methodology. This consists of measuring the accuracy and/or speed with which subjects recognize emotions in pictures of faces presented to them; here, particular interest is paid to negative emotions, especially anger, which is so prominent in BPD. Almost all the studies report that borderline personalities differ from control subjects on this task, in some cases not just for anger but for negative emotions as a whole. But, interestingly, the direction of difference observed varies across experiments. In some cases borderline individuals have been found to be less responsive in processing emotional information (Herperz et al., 1999); in other cases the opposite has been shown to be true (Wagner & Linehan, 1999).

The contradiction in these studies might be partly explained by differences in sampling or task demands – or a combination of both. There is an interesting parallel here with observations on anxiety (Williams et al., 1997). We know that anxious individuals are abnormally sensitive to signals of threat. But whether this shows up as a faster, or a slower response to fearful stimuli depends on the nature of the task. If the test requires an orientation to the stimulus the reaction is faster, but if the natural response is avoidance, or screening out of the stimulus, the opposite occurs.

Another possible reason for the conflicting findings on BPD is that the experimental paradigm was simply not capable of capturing the subtleties of borderline pathology. In another, more clinically focused, study several facets of affect regulation were examined. There, borderline individuals showed what amounted to a mixture of hypersensitivity and ineffectualness. Compared with non-borderline subjects, they had lower levels of emotional awareness and were poor at both recognizing facial expression and dealing with mixed valence feelings; but they showed much more intense responses to negative emotions (Levine et al., 1997).