Chapter 6

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Introduction

As we have seen in the previous chapter, Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is listed in the DSM-IV as one of the Anxiety Disorders. While it is clear that patients with this disorder have some characteristics that overlap with the other disorders in this category, some have questioned the appropriateness of its inclusion, arguing instead the existence of an aetiology that is specific to OCD. Some have even suggested that anxiety is not causally implicated in the development of OCD, but rather that the disabling and distressing symptoms of the disorder give rise to the anxiousness that is typically observed in these patients.

Indeed, illustrative of the uncertainty of how to classify OCD is the fact that, different from the DSM, it is listed as a category separate from Anxiety Disorders in the ICD-10. One of the arguments for viewing OCD as a distinct disorder is the fact that it is consistently resistant to medications that are successful in treating most anxiety disorders. Other factors also distinguish the two forms of disorder. For example, OCD, unlike anxiety disorders, is characterized by deficits in the ability to inhibit irrelevant or distracting information. Its primary symptoms comprise intrusive and obsessional thoughts which are sometimes followed by repetitive, excessive, and intentional behaviours whose purpose is to neutralize the obsessions and reduce the distress they cause. Another interesting observation supporting the behavioural and biological separateness of these disorders is that nicotine dependence is highly prevalent in Generalized Anxiety Disorder and yet is very rare among OCD patients (Bejerot & Humble, 1999). Since nicotine is known to increase frontal lobe activity, it seems to exacerbate the symptoms of OCD, and is therefore an aversive behaviour for those suffering from this disorder.

Although OCD has been regarded as a unitary disorder since its introduction in the first version of DSM in 1952, its clinical features are, nevertheless, overtly heterogeneous so that any particular individual may have one – though more typically several – of a variety of symptoms which are present in varying degrees and combinations. Earlier attempts to deal with the symptom variability in OCD proposed a nosology of mutually exclusive subtypes, namely, Washers and Checkers. The more current view is that the clinical features of OCD are better described as ‘moderately correlated symptom dimensions’ – a framework which has been identified primarily through the use of factor-analytic procedures, and recognition of the great variability across patients in symptom severity (Mataix-Cols et al., 1999; Summerfeldt et al., 1999). Although studies have not completely agreed on the precise factor structure of OCD symptoms, either four or five primary dimensions seem to emerge, and are described in Table 6.1.

In a general sense, the inability to assess risk quickly and accurately is a core

Table 6.1 Symptom dimensions in OCD.

| Symmetry and ordering are the most common symptoms of OCD typically involving obsessions about exactness, and repetitive counting and repeating activities that relate mostly to concerns about security and accuracy |

| Hoarding relates to obsessions about saving, and to compulsions to collect, in excess, particular items such as old newspapers, cans of food or plastic bags of useless rubbish like old bits of paper |

| Contamination and cleaning include obsessional concerns with bodily secretions, germs and dirt, environmental contaminants, and worries about illness. This factor also includes compulsions, such as excessive handwashing, grooming, and household cleaning |

| Aggressive obsessions and checking comprise a range of fears, such as excessive worry about harming oneself or others, doing something embarrassing, acting on unwanted impulses, and obsessions of violent images. The compulsions typically involve checking door locks, stoves and other appliances; and carrying out acts which reassure that one hasn’t harmed others. In severe cases, the checking rituals can be performed for hours each day, and to such a degree that the individual is scarcely able to leave the house |

| Sexual/religious obsessions include the experience of forbidden or perverse thoughts and impulses which often concern things like incest and homosexuality, or concerns about sacrilege and blasphemy. When they occur in isolation of other symptoms, this is usually called ‘pure obsessional disorder’ |

characteristic of all forms of OCD. However, the most subjectively distressing feature of OCD, and one experienced by patients of every symptom subtype, is the pervasive and overwhelming feeling of doubt – a sensation that cannot be eliminated by common sense or reasoning. For example, a woman may engage in some repetitive and ritualized behaviour like hand washing even though she knows logically that her hands are clean and that she has not touched anything dirty or harmful. But things just do not feel right so she remains compelled to repeat the washing over and over until the uncertainty disappears, and she senses that the behaviour has achieved its purpose. Some have described this moment as the ‘just right’ phenomenon, and explain that the individual can only achieve closure on the compulsive behaviour when this feeling occurs.

It has been largely implicit in the diagnosis of OCD that patients are able to recognize the excessive and unreasonable nature of their obsessions and compulsions. Predicated on the reliability of this assumption, OCD has always been firmly embedded among the ‘neurotic’ not the ‘psychotic’ disorders. However, this tenet does not always mesh with clinical reality since OCD patients exhibit varying degrees of insight into the validity of their thoughts and actions. Occasionally – studies suggest in less than 10 per cent of patients with OCD – insight is lost altogether, and their cognitive features begin to resemble delusions and take on the characteristics of a frank psychotic disorder. For this reason, some have suggested that obsessions and delusions, rather than being dichotomous categories, exist at either end of a continuum of insight, with what the DSM calls ‘overvalued ideas’ somewhere in the middle (Eisen et al., 1999; Marazziti, 2001). How then do we classify OCD patients whose obsessions, at times, become delusional? Some have chosen to classify these patients as schizophrenic or simply psychotic, whereas others have introduced the term ‘schizo-obsessive subtype’ into psychiatric parlance to accommodate both aspects of the clinical profile. The DSM has also taken the middle ground by adding ‘with poor insight’ as a diagnostic qualifier for OCD patients who are partly convinced that their obsessions are reasonable. For more extreme cases of delusional OCD, the terms delusional disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified were added. It seems that a key factor distinguishing OCD with delusions from psychotic psychopathology is a clear and logical link in the former between the delusional thoughts and the rituals they prompt (O’Dwyer & Marks, 2000). Much more about delusions, in the context of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, will be discussed in Chapter 9.

Natural History of the Disorder

Although OCD represents the fourth most common psychiatric disorder, it is still frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated in most populations. Indeed, 15 years ago OCD was thought to be a very rare condition, occurring in less than 0.5 per cent of the population. Now, however, estimates from more sophisticated epidemiological studies indicate that the lifetime prevalence of OCD is at least three per cent in females and two per cent in males, of whom the latter also have, on average, an earlier age of onset (Bebbington, 1998). Gender-related differences have also been observed in the symptom profile of the disorder. Generally speaking, women display more contamination and aggressive obsessions, and more cleaning rituals, whereas symmetry, exactness, sexual obsessions, and hoarding behaviours are more common in men (Bogetto et al., 1999; Pigott, 1998). Another interesting observation is that epidemiological samples provide a strikingly different symptom profile from those of patients who were identified and assessed in treatment facilities. For instance, the former are much more likely to have obsessive thoughts without compulsive behaviours, whereas most clinical patients report both. One plausible explanation for this difference is that compulsive acts are simply more obvious than obsessions, and therefore are probably viewed as more deviant by the individual and/or by friends and family – a factor which is likely to prompt a stronger motivation, in these individuals with noticeable compulsions, to seek treatment.

During the past decade or so, we have become aware that about a third to a half of adult OCD patients actually experienced the first symptoms of their disorder during childhood, although the disorder mostly went undiagnosed at this time (Robinson, 1998). There also seems to be a rather bimodal distribution in the age of onset with the first peak occurring between the ages of 12 and14 years, and the second peak between 20 and 22 years of age. This, coupled with the fact that an earlier onset is related to a poorer prognosis – especially in men – has prompted a particular interest in the study of paediatric OCD.

Although the diagnostic criteria for children are the same as for adults, the primary differences between the two are usually seen in how the children experience the illness. They are usually more frightened by their obsessions, and they frequently involve their parents or other close family members in their elaborate rituals. For example, mothers are sometimes required to perform time-consuming activities to cleanse themselves before washing the child’s clothing. Or, others in the home are also required to carry out the checking compulsions of the child or to avoid the feared stimulus. In general, however, the degree of interference or distress caused by the symptoms may best be assessed in the context of schoolwork and peer friendships, which are often seriously compromised. Having said that, it is interesting that children with OCD do not typically exhibit the significant cognitive deficits that generally become apparent if the disorder persists and becomes chronic.

Another difference between adult and childhood cases may be seen in the presentation of the disorder. Children who show signs of OCD before the age of six years are much more likely to have compulsions than obsessions – pure obsessiveness is quite rare in these cases – and by far the most common are washing rituals, followed by checking and counting. Another interesting observation is that if the child has an affected first-degree relative there is no consistent similarity in the nature of the symptoms, suggesting that mimicry or modelling of symptoms is not a feature of the disorder (Robinson, 1998).

Until recently, there have been few long-term follow-up studies of OCD, making it difficult to provide prognostic information to patients and their families. For that reason, a recently published prospective follow-up of 144 OCD patients over a 40-year period has been particularly helpful in framing a more complete picture of the natural course of the disorder; even more so because only a small proportion of the study patients had ever received pharmacological treatment for their disorder (Skoog & Skoog, 1999). By the end of the follow-up period, about 80 per cent of the patients showed improvement in their symptoms – many within 10 years of the onset of their illness. However, only 20 per cent of the patients ever achieved full remission, 10 per cent showed no improvement, and another 10 per cent had a deteriorating course of their illness. Also discouraging was the fact that approximately 20 per cent of the patients who showed early recovery, followed by at least 20 symptom-free years, were plagued by persistent relapses.

Causal Explanations of OCD

Biological Models

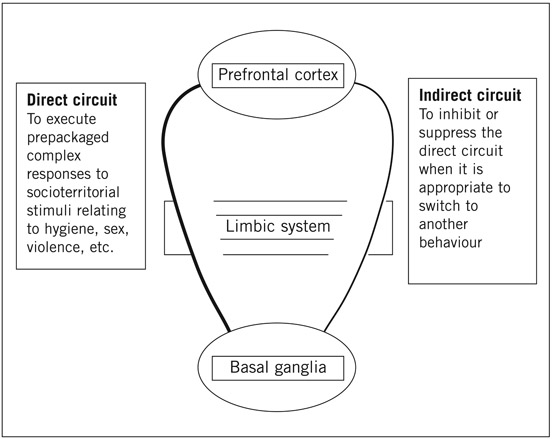

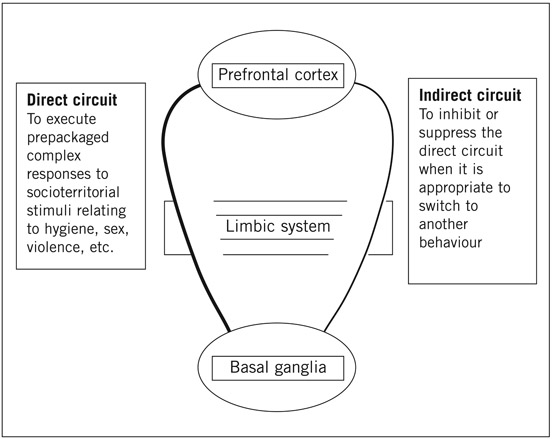

Many have attempted to explain the cause of this debilitating illness whose symptoms have been described in psychiatric writings for over a century. Although it has not always been the prevailing viewpoint, there is currently a strong belief that OCD has its genesis in brain neuropathology. And, this viewpoint has spawned the development of several biological models of the disorder, all of which predict, in one way or another, the involvement of the prefrontal cortex, the basal ganglia, and the limbic system in the generation of OCD symptoms. Although a detailed description of neuroanatomy and neurophysiology is beyond the scope of this chapter, a brief consideration of some aspects of brain circuitry and functioning will help illustrate what we understand about the complex biology of this disorder.

The prefrontal cortex has direct neural circuitry to the basal ganglia via its connections with the limbic system. It also receives signals from these subcortical nuclei, and so, in response, can alter their activity. In other words, there are functionally reciprocal frontal-subcortical circuits which pass through the limbic system. Conceptually, each of these circuits is understood as having two loops – a ‘direct’ and an ‘indirect’ pathway – the former functioning as a positive feedback loop and the latter as a negative feedback loop.

Baxter and colleagues have outlined an elegant conceptual model of OCD pathophysiology by proposing that the function of the direct circuits is to execute ‘pre-packaged’ complex responses to what they call ‘socioterritorial’

Figure 6.1 A model of OCD.

stimuli – that is, things that are highly significant to the survival of the organism, such as hygiene, sex, safety, and keeping things in order (see Saxena et al., 1998). These are responses that need to be carried out quickly in order to be adaptive, and which must operate to the exclusion of other interfering stimuli. The activation of these direct pathways tends to pin or rivet the execution of the behaviour until the attentional need to do so has passed. Part of the function of the indirect pathways is to inhibit or suppress the direct pathways when it is appropriate to switch to another behaviour – something we know that OCD patients have trouble doing. In healthy individuals, socioterritorial concerns pass through the direct pathway and are inhibited by the indirect pathway in a suitably timely manner. However, in OCD patients the excess activation of the direct pathway results in a fixation of these concerns. Because the appropriate inhibition has been too weak to turn off the signal, these concerns are experienced by the individual as repetitive and intrusive obsessions. In other words, as we can see in Figure 6.1, this model of OCD proposes a substantial imbalance in the tone or sensitivity of the direct–indirect pathway in OCD patients, which results in a response-bias towards socioterritorial stimuli; precisely the concerns which form the theme of most obsessions in OCD patients.

This popular conceptual model meshes well with neurobiological evidence from a variety of sources. For example, neuroimaging studies have consistently shown increased prefrontal activity, most frequently involving the right orbitofrontal cortex, in unmedicated individuals with OCD. Indeed, it has been said that OCD patients display behaviours that are consistent with ‘overheated’ frontal lobes. Interestingly, these areas of hyperactivity seem to normalize when patients receive effective treatment, either pharmacologically or from behavioural therapy. Since the frontal cortex plays an important role in assessing the behavioural significance of biologically significant stimuli, it seems that heightened frontal activation may relate to obsessional thinking, but not necessarily to compulsions. On the other hand, the function of the basal ganglia and the cerebellum may modulate compulsive urges since the latter stores behavioural programs like conditioned reflexes. Also certain diseases with pathology localized to the basal ganglion, such as Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s chorea, often show compulsive symptoms similar to those seen in OCD.

Other biological theories of OCD have focused more squarely on the role of neurotransmitter mechanisms. In particular, a dysfunction of brain serotonin (5-HT) has been proposed as a leading cause of OCD for several years. The so-called ‘serotonin hypothesis’ derived in large part from the clear and consistent efficacy of serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) drugs in patients with OCD, and therefore the notion that OCD must be caused by a deficiency of 5-HT transmission (see Chapter 5 for a brief discussion of SRIs). More recent research using peripheral 5-HT markers, pharmacological challenge tests, and brain imaging techniques has also kept alive a strong belief in the involvement of 5-HT in this disorder (see Baumgarten & Grozdanovic, 1998; Delgado & Moreno, 1998 for reviews).

For example, there has been a number of case reports of symptom improvement when OCD patients use hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD, which are potent stimulators of brain 5-HT. Others have reported the exacerbation of symptoms after administration of 5-HT antagonist drugs. However, while 5-HT is clearly important to our understanding of the causal mechanisms in OCD, it would be greatly misleading to suggest that it tells the whole story, especially as accumulating evidence (which will be discussed later) indicates that dysregulation of other neurotransmitter systems – primarily dopamine – is implicated in OCD pathogenesis. Moreover, to give a balanced picture, we must also consider the limitations of the serotonin hypothesis. First of all, many patients are only partially responsive to SRI drugs, and nearly a third of patients do not respond at all. In addition, there is a range of other 5-HT agonists that have produced no symptom improvement at all – even a worsening of the condition in some patients. Also, studies that have used a 5-HT depletion paradigm were typically not able to show a reversal of the symptom improvement induced by SRI drugs – an effect that is seen consistently with depressive symptoms in patients with depression. Nor does 5-HT depletion have an ill effect on unmedicated, symptomatic people with OCD. One thing these particular results suggest is that whatever the role of 5-HT in the treatment of OCD, it is probably not the same as the role it plays in the treatment of depression.

On a more whimsical note, the observations of psychiatrists and poets have converged in the recent discovery of neurochemical similarities between OCD and romantic love! Perhaps this should not surprise. Certainly, writers have noted the commonalities between love and psychological disturbance for centuries, having written about falling ‘insanely’ in love or being ‘lovesick’. Even in everyday parlance we say he is ‘mad’ about her when we describe the affection of a man for a woman. Indeed, it is not difficult to see that the obsessive preoccupation with, and the overvalued ideation about, one’s love object during the early stages of romantic love are little different from the obsessions we see in OCD patients. Comparisons between OCD patients and a sample of healthy volunteers who reported having recently fallen in love, showed a statistically significant decrease in the number of 5-HT transporter proteins in the platelets of both groups compared to normal subjects (Marazziti et al., 1999). Moreover, OCD patients who had recovered from their symptoms, and the volunteers who were no longer ‘in love’ when they were retested a year later, showed levels in this 5-HT marker that were indistinguishable from normal subjects. It is interesting to see how similar changes in the 5-HT transporter map onto the abatement of psychological symptoms in the two groups studied in this experiment.

A prime difficulty with the ‘serotonin hypothesis’ – and it reflects a mode of thinking that is common in other areas of psychiatric research – is that it may be based on faulty logic. Just because drugs such as SRIs increase 5-HT activity and are effective in alleviating the signature symptoms of the disorder, it does not necessarily follow that the cause of the condition is a dysfunction or deficiency in that neurotransmitter system; any more than taking an aspirin to cure a headache implies that headaches are caused by a deficiency of acetylsalicylic acid. In fact, with the development of more and more sophisticated neuroimaging techniques, it is becoming clear that a variety of lesions in the brain (either structural or functional) could lead to the development of symptoms without there being any impairment of 5-HT neurotransmission (Delgado & Moreno, 1998).

On the basis of the imperfect response to SRI drugs alone, it is clear that 5-HT is not the only neurotransmitter involved in the pathophysiology of OCD, or at least, not all forms of OCD. Accumulating evidence suggests that excessive dopamine availability may also play a role. One line of evidence comes from an interesting animal model known as the quinpirole preparation (Szechtman et al., 1998). Rats treated chronically with this dopamine D2/D3 agonist drug, display ritual-like behaviours with a distinct similarity to the motor behaviours seen in OCD patients with checking compulsions. Since compulsive checking is probably an exaggerated form of normal checking behaviour designed for the protection and security of the organism, this model suggests that checking (and perhaps other protective behaviours) may well be a dopamine-based behaviour.

Other evidence of dopamine involvement is that haloperidol – a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist – has been useful for improving the treatment response to SRI drugs. This makes sense theoretically because stimulation of D1 receptors is known to activate preferentially the direct orbitofrontalsubcortical pathways, and stimulation of D2 receptors has been shown to decrease activity in the indirect pathways whose function is to dampen down the hard-wired behaviours under the control of the direct pathway. In other words, by blocking D2 receptors, the indirect pathway is more efficiently able to counteract the action of the direct pathway.

Cognitive Models of OCD

Some clinicians and theorists have eschewed or discredited biological interpretations of OCD, instead favouring a more cognitive approach to the understanding of this illness. The early cognitive explanations relied mostly on a classical conditioning paradigm whereby traumatic learning caused certain stimuli to evoke anxious feelings and thoughts, which were then strengthened and maintained because particular behavioural rituals seemed to provide relief from this anxiety. There is a certain intuitive appeal to this idea since many cases of OCD have their onset after a stressful life event, and stress is a common trigger of relapse. Its limitation, however, is that it does not provide an explanation for cases that do not have an obvious or apparent traumatic precursor. Consequently, more recent cognitive accounts have moved beyond a strictly behavioural approach.

Currently, the most prominent cognitive theory is one proposed by Salkovskis (1985) and developed as an expansion of Clark’s theory of depression and panic, which was discussed in some detail in Chapter 5. It starts from the premise that unwanted or intrusive thoughts are not only the precursor to, and the raw material of, obsessions, but more importantly they are part of universal and everyday cognitive experience. In other words, normal intrusive cognitions in healthy individuals are ideas, impulses, or images that interrupt one’s stream of consciousness, and are indistinguishable in terms of their content from obsessional thoughts in OCD except that they are less intense, less long-lasting, and less distressing. Also, repetitive behaviours are especially apparent in childhood and are believed to reflect a strong need for predictability and order when a child is very young. It is also believed that maturation and the drive for mastery, control, and socialization are fundamentally dependent on repetition and elaborate rules of behaviour. In the average child, most of the normal childhood rituals – many of them fear-related and observable at night-time – have subsided by the advent of puberty. However, it is important to emphasize that even though childhood compulsions are developmentally normal, the extent of these behaviours is highly correlated with anxiety. The more anxious children in all pre-adolescent age groups engage in a greater number and more intense ritualized behaviours than those who are less anxious.

In summary, the cognitive view is that obsessive-compulsive symptoms have their origins in, and are simply an extension of, normal behaviour. We might then ask what it is that turns a normal intrusive thought into an abnormal and tormenting obsession? Cognitive approaches identify two important factors in this transition: misinterpretation and psychological vulnerability; the latter increasing the likelihood that the former will occur. To be more specific, the transformation of a commonplace thought into something abnormal rests on the catastrophic way it is interpreted. For example, the individual believes that the intrusive thought is more important or threatening than it really is, or believes it has far greater personal significance than is logically warranted. A case example will help to illustrate this point.

Case Study: Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Walter, who is a 40-year-old devoutly religious man, with a highly developed sense of morality, had recurrent and obscene thoughts about the Virgin Mary. These were especially frequent when he was in church and was trying to pray. Instead of dismissing them as trivial and of no consequence, he immediately believed he was seriously sexually perverted and that his religious beliefs were flawed and insincere. Clearly, this catastrophic interpretation of his impure thoughts caused him great distress and fear. He soon stopped attending church services and began to eschew anything that contained Christian images. For instance, he used to enjoy visiting museums of art but could no longer do this because of the numerous pictorial references to Mary in the works of the old Masters.

However, theorists agree that the tendency to misinterpret or overinterpret is far more likely to occur in some individuals – like Walter – who are in possession of certain vulnerability traits. For example, there is a relationship between OCD and a particular cognitive style known as thought–action fusion. Typically, this can take two forms and describes tendencies with which we are all familiar, but which occur in an exaggerated form in some individuals. The first is the belief that having an unacceptable thought – such as imagining that the plane on which a loved one is flying is going to crash – increases the likelihood that the dreadful event will occur. The second is the belief that having a frightening or unacceptable thought is the moral equivalent of carrying out the action associated with that bad thought.

There has also been considerable interest in the use of cognitive experimental methods to examine whether information-processing abnormalities in OCD could possibly give rise to the symptoms that characterize the disorder. McNally (2000) argued that the cognitive biases that describe these abnormalities are not ‘mere epiphenomenal sequelae of the disorder, but rather constitute the pathogenic mechanisms themselves’. He also explains that although these biases may have their roots in the physiology of the brain, they cannot easily be reduced to concepts or explanations at the neurobiological level of analysis. Instead, we must rely on characterizing them functionally. Although information-processing abnormalities have been relatively understudied in OCD, when compared to their role in other disorders, there is already some evidence that certain cognitive deficiencies and derangements have been identified in this disorder.

One line of support is that individuals who develop OCD tend to have attentional biases that contribute to their recurrent obsessions. For example – and in ways similar to patients with anxiety disorders – those with OCD attend more persistently to threatening or potentially harmful stimuli. Data from various paradigms, including emotional Stroop experiments, have shown that OCD patients are more likely than healthy subjects to process obsession-relevant cues. Their attention also seems to be dysfunctional in its ability to ignore irrelevant or distracting information. This may give rise to the development of elaborate strategies to suppress the distracting thoughts. However, as Wegner’s research has pointed out (see Chapter 5 for a discussion), active attempts to suppress certain thoughts – especially negative ones – usually result in an increase in their frequency. One can see how a vicious cycle of intrusive thoughts and suppressing rituals may develop and become habitual and persistent.

Other research has focused on the role of forgetting and the possibility that obsessional thoughts may result from a selective dysfunction in this ability, as well as from a hypersensitivity to the encoding of potentially threatening stimuli. Although studies have found that OCD patients were relatively unable to forget words construed as threatening, compared to neutral or positive words, it may well be because they have an enhanced memory for threat stimuli, rather than an impairment in their ability to forget (Wilhelm et al., 1996).

With respect to those who check compulsively, several cognitive explanations have been proposed and supported by research in the area of memory. For example, OCD patients may either fail to commit certain actions to memory, or they may have a diminished ability for retrieval from memory. Another possibility is that they may have a deficit in reality monitoring – that is, the ability to distinguish the memory of carrying out the action from the intention to do so. Although most studies have found no significant decrements in the ability of OCD patients to monitor reality accurately, these patients do often report a deficit in the confidence they place in their memory.

In summary, although we have good evidence that OCD symptoms might develop, in part, because of attentional biases favouring stimuli construed as potentially harmful, we are still not entirely clear about why certain stimuli become linked to threat and why others remain neutral. Nor are we entirely clear on how the emergence of obsessions gives rise to the particular compulsions that are used to neutralize their impact. Fear conditioning and an enhanced biological preparedness to target environmental stimuli related to safety and survival, may well contribute to the explanation.

Personality Factors in OCD

Before we begin this discussion, it is important to talk about some of the methodological difficulties inherent in trying to establish causal connections between personality factors, on the one hand, and vulnerability to OCD, on the other. The first problem concerns the longevity of the disorder. As we have seen earlier, a substantial proportion of patients experience the onset of OCD in childhood or adolescence, and only a small percentage ever recover fully. Therefore, the disorder is mostly a chronic condition, and although the symptoms may alter in severity over time, for most they have a lifelong presence. A second problem is that few, if any, studies of personality and OCD are prospective in design. Instead, most of the evidence is drawn from correlational data, obtained from patients in the full-blown throes of their disorder, allowing for little more than the assessment of relationships among variables. When considering both these problems together it is easy to see why some have disputed the meaningfulness of thinking of personality traits and OCD symptoms as discrete and separable entities or phenomena (Summerfeldt et al., 1998). Instead, it is argued that the severity of OCD symptoms confounds the valid assessment of personality traits. Existing research also makes it difficult to determine whether there is a specific profile of personality characteristics which increases the risk for OCD, or whether certain personality traits render the individual vulnerable to environmental stressors, which in turn interact with personality to cause the disorder. A third possibility – what some have called the ‘scar hypothesis’ – is that the chronicity and the distressing nature of the disorder irrevocably change a person’s personality, as seen in their thoughts, their mood, and their behaviours. However, despite these methodological caveats, and irrespective of whether one focuses on the biological origins of OCD or one takes a more cognitive approach to its development, certain traits have emerged from the research with enough consistency for us to conclude that individual differences do play an important role in the development of OCD.

In the study of personality risk factors, some research information has come from case records and clinical observation, whereas other data have been obtained from self-report questionnaires and assessment interviews. Research has also approached the study of personality and OCD from two distinct perspectives. One has been to assess the comorbidity between OCD and the Axis II personality disorders, while the second has examined dimensionally constructed obsessive–compulsive personality traits in patients with OCD.

The logic guiding the former methodology is that comorbid personality disorders provide a key to uncovering underlying traits that increase risk for OCD. On the surface, this seems like a fruitful endeavour given the high comorbidity between personality disorders and OCD – estimates range between 33 per cent and 87 per cent (Bejerot et al., 1998a; 1998b). However, this approach has been criticized on a number of counts, and seems to have done little to inform us about the psychology that predisposes to OCD (see Summerfeldt et al., 1998 for a review). Nevertheless, a brief overview of the main findings from these studies is worth describing.

Although there is considerable variability in the findings from comorbidity research – indeed, all types of personality disorders have been found in these patients – the most consistently diagnosed personality disorders in OCD patients are avoidant, dependent, histrionic, schizotypal and, to a lesser degree, obsessive compulsive. In other words, the most prevalent personality disorders seem to come from Cluster C. However, as suggested earlier, we are limited in our ability to infer from these studies that specific personality traits are causally implicated in the development of OCD because of the distinct possibility that an illness as severe as OCD can foster abnormal personality traits rather than, or at least as often as, the reverse (Black & Noyes, 1997). The association of OCD with avoidant personality disorder serves as a good way to illustrate this point. As we have seen, OCD symptoms are generally severe, socially embarrassing, and time-consuming, causing sufferers to become isolated and withdrawn, and therefore to develop characteristics highly consistent with the diagnosis for avoidant personality disorder. In other words, this personality disorder may not be a primary cause of OCD, but rather a consequence of its symptomatology. Another problem of interpretation has been called ‘criterion contamination’ and applies aptly to the comorbidity between schizotypal personality disorder and OCD. For example, questionnaire items that were designed to assess schizotypal factors, such as cognitive distortion and magical thinking (for example ‘No matter how hard I try, unrelated thoughts always creep into my mind’), may be endorsed by OCD patients for reasons quite distinct from the intended meaning of the item.

The great similarity in the diagnostic labels – Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder and Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Disorder – has led many to assume that the development of OCD requires a predisposing personality disorder of the same name. Or, argued another way, that OCPD is simply a milder form of OCD. Even intuitively this seems right since those with OCPD tend to be orderly, excessively organized, overly conscientious, and perfectionistic. They are also less prone than healthier individuals to let reward or pleasure guide their behaviour. These are all features that we see in a more exaggerated way in OCD. Therefore, it is rather surprising to find less overlap between the two disorders than one might imagine. For instance, in studies of patients with OCD, the reported prevalence of OCPD has ranged from as low as 4 per cent to approximately 50 per cent, suggesting that the two disorders are rather independent mental health problems that share some overlap but are not related in most cases (see Diaferia et al., 1997).

However, before jumping to such a conclusion we should consider some factors that may artificially reduce the comorbidity of the two disorders. First, and as we have said before, OCD is such a debilitating condition that the reliable assessment of basic personality factors is extremely difficult and confounded by its clinical features. Second, if OCPD traits are not obviously present in a patient with OCD, we should not infer that these traits were unimportant in the development of OCD. We say this because at the extreme of some dimensions, a sort of ‘chaos’ ensues rather than an orderly progression of the underlying characteristic. This distinction may be made clearer by considering a physical analogy. Friction, such as that created by rubbing one stick against another, causes an increase in heat as the process continues. Eventually, a chemical reaction takes place and combustion occurs. The extreme heat becomes a spark of fire! However, the fire on its own gives no hint that it was the friction of two sticks rubbing together that gave rise to it. Similarly, there may be a qualitative difference rather than a quantitative difference in the clinical picture (such as we see in OCD) when the OCPD traits become very extreme (recall a discussion of this point in Chapter 2).

A final consideration is that the traits which describe OCPD may only be a precursor to certain types of OCD and not to others. For example, it may be that OCPD traits give rise to compulsions about symmetry and ordering, and/or to contamination and cleaning symptoms but not to the other forms of the disorder, such as compulsive hoarding. Since none of the comorbidity studies have examined OCD subtypes, instead treating the disorder as a uniform entity, this could obscure and underestimate the role of certain personality traits in the development of OCD. When we take all these possibilities into account, a more balanced view on the relationship between OCD and OCPD would be that although anancastic personality traits (or disorder) are not necessary or sufficient for the development of OCD, individuals with these traits are probably more prone to develop at least some forms of the disorder.

The dimensional approach to the study of personality and OCD does not really eliminate the methodological problems that we have already discussed. It may, however, make them easier to identify. Studies that have operated within this framework have identified a number of traits which seem to increase the likelihood of developing obsessional thinking. These include having an overdeveloped sense of responsibility, very high moral standards, and striving for moral perfection (like Walter in the case study described earlier). Indeed, early, as well as contemporary, theories of OCD have assigned perfectionism a central role in the development of this disorder, even though there is no evidence of excessive perfectionism in OCD compared to many other psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety disorders (Blatt, 1995). It seems, therefore, that perfectionism predisposes to many forms of psychopathology, but does not necessarily determine the precise form the disorder takes.

Other clinical studies have used broader dimensional constructs to assess personality, such as the self-report questionnaires developed by Cloninger (and described in detail in Chapter 3) to characterize the stereotypic patient with OCD. The data are consistent in describing a patient who tends to be high in harm avoidance and persistence, and low in reward dependence and novelty seeking – a profile that chimes well with the clinical features of this disorder.

The aetiological role of trait anxiety in OCD has fuelled much debate, and many have argued vociferously that anxiety does not have the primary predisposing role that it does in many forms of psychopathology (see Hoehn-Saric & Greenberg, 1997). There is no doubt that OCD patients have high scores on self-reported measures of anxiety, but it could be – and some physiological data support this idea – that the anxiety observed in OCD is a state characteristic consequent on the debilitating symptoms, rather than a trait which causes obsessional thoughts and compulsive behaviours. Others, however, believe that anxiety both contributes to, and exacerbates, the obsessional symptoms of OCD. For example, anxiety and the tendency to avoid harm is likely to foster a hypervigilance for threat and a bias toward the encoding of threatening stimuli which, in turn, will leave the individual in a state of persistent anxiety. Negative or depressed mood is also regarded as an important trigger to the onset of obsessive–compulsive problems because it seems to sensitize an individual’s responsiveness to intrusive thoughts. Here it is worth noting that OCD patients are highly prone to comorbid depression.

Studies of healthy men and women have also examined relationships among personality, mood, and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Wade et al., 1998). In general, these have found that non-clinical obsessions and compulsions, such as antisocial urges, cleaning, and checking, are more likely to occur in those who are anxious, perfectionistic, morally principled, and depressive – evidence that converges with what we have learned from clinical research. These non-clinical findings have an important place in aetiological research since the study paradigm removes the symptom-severity that confounds clinical research.

Although biological and cognitive models of OCD each offer important insights into the pathogenesis of this debilitating disorder, on its own neither is sufficiently comprehensive to explain the heterogeneous aetiology, the varied clinical features, and the complex pathophysiology of OCD. Instead, what is needed are explanatory models in which neurochemical, anatomical, and cognitive factors are all fully integrated.

Obsessive–Compulsive Spectrum Disorders

In recent years, there has been a growing trend to expand the boundaries of OCD classification – using the label Obsessive–Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (OCSD) – and to include a broad range of Axis I and Axis II disorders which are connected to OCD by virtue of loosely associated similarities in symptomatology, family history, neurobiology, comorbidity, clinical course, and treatment outcome. Among the plethora of syndromes included in the spectrum are those as diverse as somatoform disorders, tic disorders, epilepsy, autism, pathological gambling, borderline personality disorder, and the eating disorders (see Hollander & Wong, 1995 for a more comprehensive list). A common thread that seems to unite all these conditions is that each involves the difficulty, or the inability, to delay or inhibit repetitive behaviours. And, the principal reason investigators cohere these seemingly disparate syndromes is their collective responsiveness to the SRI drugs. However, owing to the obvious diversity among the spectrum disorders, a number of subgroups or clusters have been described within the broader category. These include the bodily appearance disorders, the impulse-control disorders, and the neurological disorders.

Whether this new classification represents a theoretical model with useful implications for improved treatment, or whether it simply obscures by overinclusion and simplification, has been disputed by those working in the field. Therefore, and in an effort to remain objective, we will try and give a balanced view of both positions in the remainder of this chapter. Eric Hollander, a leading proponent of the OCSD classification, has presented an interesting dimensional model of the spectrum disorders, proposing that they are appropriately conceptualized along a continuum of orientation to risk, with the compulsive disorders such as OCD, body dysmorphic disorder and anorexia nervosa, at the ‘risk-avoidance’ end of the continuum, and impulsive disorders such as borderline and antisocial personality disorders at the ‘risk-taking’ end. Psychologically, the two ends of the continuum are distinguished by differences in the motivation that drives the behaviours. In the case of compulsivity, the ritualized behaviours are carried out to reduce anxiety and discomfort, whereas the behaviours associated with impulsivity are seen to maximize pleasure and arousal. Hollander (1996) also described this spectrum within a conceptual biological framework, emphasizing the role of serotonergic dysfunction in all the disorders, though in different ways along the continuum – compulsivity being characterized by brain hyperfrontality and increased 5-HT sensitivity, and impulsivity by hypofrontality and low pre-synaptic 5-HT levels. Of interest, and rather puzzling however, is that some people seem to have both impulsive and compulsive features simultaneously, or at different times during the course of the same disorder.

Recent research suggests that a core feature of this risk-taking dimension is the varying ability to make good decisions, or to delay gratification, if doing so results in a better long-term outcome. The impulsive or high end of the dimension reflects a diminished capacity to do so, and the compulsive end of the spectrum displays a heightened tendency to inhibit reward. To illustrate, rats with a lesion in the core of the nucleus accumbens, a key brain area in the experience of pleasure and reward – and a topic that will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 7, on addiction – consistently chose small or poor rewards that were immediately available in preference to larger delayed rewards (Cardinal et al., 2001). Similar findings have been observed in the human condition where those with bilateral ventromedial prefrontal lesions made choices on a gambling task that gave high immediate gains, but led to high future losses (Hollander & Evers, 2001).

While there is clearly some argument for viewing OCSD as a valid diagnostic entity – and there are many who do – other investigators have made the point that the commonalities among the disorders that comprise OCSD are more superficial than real, and that the differences between, say, OCD patients and patients with antisocial personality disorder, are substantially greater than their similarities (Rasmussen, 1994; Crino, 1999). Critics also point out that these disorders vary greatly in the cognitive component of their symptoms as well as the individual’s motives for engaging in the behaviours. Questions too have been raised about the appropriateness of grouping disorders simply on the basis of similar drug treatment outcomes; in this case, good response to the SRI drugs. To illustrate this point, Rasmussen (1994) used the analogy of corticosteroids which are used to treat a variety of medical conditions that affect multiple organ systems. Yet no one, he argues, would think of linking, in a diagnostic way, all the diseases that are successfully treated with such drugs.

However, what we should really ask is whether there is anything to be gained from invoking the OCSD label, either in clinical practice or in terms of research. Moreover, and apart from the question of utility, the OCSD label itself is something of a misnomer and may serve to confuse and mislead. As Rasmussen (1994) reminds us, many of the so-called OCSDs have features that are quite unrelated, indeed almost opposite, to OCD. Furthermore, as we have seen throughout this chapter, OCD itself is a vastly heterogeneous illness or set of illnesses.

In this, and the previous two chapters, we have considered Axis I and Axis II disorders whose symptomatology has an intuitive and recognizable continuity with the personality and temperamental traits that – at least partly – give rise to them. In the next two chapters we will discuss two other disorders (addiction and the eating disorders) that display more complex, dynamic, and progressive patterns of behaviour. These are also disorders where volitional control is perhaps more salient than in other conditions, and where there seems to be a stronger aetiological role for social factors. It could also be argued that these disorders are primarily behavioural strategies – albeit maladaptive in their outcome – to cope with the psychological distress caused by the personality and other disorders described in chapters 4, 5 and 6. Therefore, one way to conceptualize the role of personality in addictive behaviours (Chapter 7) and the eating disorders (Chapter 8) is as a distal rather than proximal cause in their respective aetiologies.