CHAPTER 13

WEB AND SOCIAL MEDIA

This chapter includes contributions from Crysta Anderson (IBM), Akin Arikan (IBM), Kurt Wedgwood (IBM), and Arvind Sathi (IBM).

We have devoted a relatively lengthy chapter to the governance of web and social media data because of the heightened focus in this area. Social media is re-shaping the way organizations engage their customers and nurture their relationship to brands, products, and services. Here are some figures that give an idea of the scale of the social media phenomenon:

- 770 million people worldwide have visited a social networking site.1

- 500 billion impressions about products and services are annually shared online by consumers.2

- More than 60 percent of those impressions are shared on Facebook, with 16 percent of users generating 80 percent of the messages and posts about products and services.3

- 78 percent of consumers trust peer recommendations.4

For marketers, a good portion of social media’s value lies in its ability to aggregate communities of interest and identify specific demographics, and thus enable marketers to precisely segment and engage their audience. Social media can be a catalyst to help companies achieve the following:5

- Influence and intimacy—Social media amplifies the “relationship” in customer relationship management (CRM). Consumers trust their peers. In addition, companies have the ability to aggregate and segment consumer data easily.

- Scale and speed—Social media channels enable marketers to reach more customers faster, dynamically, and with greater precision. It can take months of planning, creative development, and media purchases to launch a print ad campaign, for example, compared to the immediacy of Twitter and Facebook campaigns.

- Lower costs—Social media offers dramatically lower costs to precisely target and engage audiences across multiple channels, segments, and geographies.

The big data governance program needs to adopt the following best practices to govern the usage of web and social media data:

13.1 Consider evolving regulations and customs when establishing policies regarding the acceptable use of social media data about customers.

13.2 Set up policies regarding the acceptable use of social media data about employees and job candidates.

13.3 Leverage confidence intervals to assess the quality of social media data.

13.4 Establish policies regarding the acceptable use of cookies and other web tracking devices.

13.5 Define policies linking online and offline data, to establish a comprehensive view of the customer in a manner that does not violate privacy concerns and regulations.

13.6 Ensure the consistency of web metrics.

These sub-steps are discussed in detail in the rest of this chapter.

13.1 Consider Evolving Regulations and Customs When Establishing Policies Regarding the Acceptable Use of Social Media Data About Customers

Individuals already post a variety of information on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, blogs, and other social media. Companies are increasingly tapping into this treasure trove of information about their customers’ demographics, behaviors, and relationships. However, in most cases, companies cannot rely on settled law and practice regarding the acceptable use of social media information. The following pages give some examples of how a handful of industries are grappling with the use of social media.

Insurance

Social media is applicable to two important functions within insurance carriers:

Case Study 13.1: An insurance investigator using Facebook to validate auto claims6

A woman filed a claim with her auto insurer, saying a hit-and-run driver damaged her car. However, investigators discovered comments on her Facebook page indicating that her daughter was responsible for the accident. The policyholder was subsequently convicted of filing a fraudulent insurance claim.

- Underwriting

Moving beyond claims, should insurers be able to use social media for underwriting purposes to set rates on policies? For example, can a life insurer use the fact that an applicant’s Facebook profile indicates that she is a skydiver to increase her premiums because of her higher risk profile? Can the life insurer reduce premiums to a 50-year old who indicates on Facebook that he is an avid tennis player? In the United States, each state has a department of insurance that regulates the insurance industry within its jurisdiction. Each department of insurance plays an important role in protecting the privacy of policyholders in that state. Although U.S. states once barred insurers from using credit scores to predict the likelihood of claims, most now allow it, with California being a notable exception. In the same vein, it is possible that regulators will permit insurers to use social media to set rates, although they are largely forbidden from doing so today.7 According to a 2011 report from the research firm Celent (http://www.celent.com/reports/using-social-data-claims-and-underwriting), social data will be incorporated into core underwriting and claims processes, and will become standard inputs into risk evaluation and settlement activities, within three years. The report reviews the types of social data that would be useful for underwriting purposes: online purchases, preferences, lifestyle, operations, and habits for individuals, and descriptions of new product offerings, services, and operations for corporations.

Health Plans

Because of privacy regulations such as the United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), health plans are somewhat limited in what they can do online. Nevertheless, Case Study 13.2 shows how a health plan changed its business processes to leverage the power of social media.8

Case Study 13.2: Managing social media perceptions at a health plan

Because Tweets, Facebook updates, and YouTube videos carry weight with current and prospective members, a health plan established a dedicated team to monitor mentions of the company in social media. When a member or physician posted a complaint about the health plan on Twitter, someone at the company reviewed it and responded. Even if the person ignored the response, the objective was to introduce the company’s response into the public record. That way, everyone who saw the complaint could also see the response. However, the health plan was constrained by HIPAA privacy regulations in terms of the content of its social media comments. Therefore, the health plan moved conversations offline and onto the phone as soon as possible.

Life Sciences

Pharmaceutical and medical device companies might want to leverage social media to better understand their customers. However, these companies operate in a highly regulated environment and need to comply with the relevant regulations. Case Study 13.3 discusses recent guidance from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding specific processes to be adopted by life sciences companies when responding to public, unsolicited requests on social media for off-label information.

Case Study 13.3: FDA regulations for life sciences companies who respond to public unsolicited requests for off-label information9

Product information posted on websites and other public electronic forums is available to a broad audience and for an indefinite period. As a result, the FDA was concerned that firms might post detailed public online responses to questions about off-label uses of their products in such a way that they are communicating unapproved or uncleared use information about FDA-regulated medical products to individuals who have not requested such information. In this circumstance, communications to people who have not requested information might promote a product for a use or condition that has not been approved by the FDA. The FDA was also concerned about the enduring nature of detailed public online responses to off-label questions because specific drug or device information might become outdated (e.g., new risk information might become available).

In light of this, the FDA made the following recommendations to life sciences companies who respond to unsolicited requests within social media for off-label information:

- If a firm chooses to respond to public unsolicited requests for off-label information, the firm should respond only when the request pertains specifically to its own named product (and is not solely about a competitor’s product). The level of specificity of the question posed in a public forum is important in determining the appropriateness of a firm responding to the unsolicited request.

Example: An individual poses the specific question “Can Drug/Device X be used for condition Y” on Twitter or in a blog (and this question is not prompted by or on behalf of the firm). It may be appropriate for the firm to respond as outlined below because the question is unsolicited and specific to the firm’s named drug or device.

Example: If an individual poses the non-specific question “What drug/device can be used for condition Y” in a public communication thread and the firm manufactures or distributes Drug/Device X, which is not FDA-approved or cleared for condition Y, the firm should not respond to the request because the question is not specific to Drug/Device X.

- A firm’s public response to public unsolicited requests for off-label information about its named product should be limited to providing the firm’s contact information and should not include any off-label information. The firm’s public response should convey that the question pertains to an unapproved or uncleared use of the product and state that individuals can contact the medical/scientific representative or medical affairs department with the specific unsolicited request to obtain more information.

- The firm’s public response should provide specific contact information for the medical or scientific personnel or department so that individuals can follow up independently with the firm to obtain specific information about the off-label use of the product through a non-public, one-on-one communication.

- After an individual has privately contacted a firm for more information regarding an off-label use of the firm’s product, the firm should provide a detailed response and maintain detailed records.

Healthcare Providers

The American Medical Association has established the following key guidelines for physicians to consider when maintaining an online presence:10

- HIPAA compliance—Physicians should be cognizant of patient privacy and confidentiality and must refrain from online postings of identifiable patient information.

- Patient-physician relationship—If they interact with patients on the Internet, physicians must maintain appropriate boundaries within the patient-physician relationship in accordance with professional ethical guidelines, just as they would in any other context.

- Separation of content—To maintain appropriate professional boundaries, physicians should consider separating personal and professional content online.

Banking

Social media is applicable to two important functions within banking:

- Credit risk—Banks are exploring the possibility of using social media data for credit risk decisions. For example, banks might use an applicant’s Tweets or Facebook page to verify his or her employment. However, banks continue to have lingering concerns about regulations that limit data collection and sharing, such as the United States Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). Notwithstanding this, the regulatory environment is less stringent for banks that leverage social media to verify credit for small businesses.11

- Collections—Collections departments use customer information from Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Monster.com to conduct “skip tracking” to get up-to-date contact information on a delinquent borrower.12 However, debt collectors need to adhere to regulations such as the United States Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), which are designed to prevent collectors from harassing debtors or infringing upon their privacy. As a result, collectors would be prohibited from creating a false profile to friend a debtor on Facebook, posting a message on a Facebook user’s wall, or Tweeting about an individual’s debt.13

Legal

A survey carried out by the British divorce website www.divorce-online.co.uk in December 2011 found that 33 percent of behavior petitions contained the word “Facebook.” Divorce lawyers are mining information on social networks to reveal cases of infidelity, hidden assets, and other “secret” aspects of a person’s life. Information gleaned from blogs, social networks, and photo-sharing sites can provide crucial evidence in legal cases. For example, a 38-year-old man hired a law firm to look into his estranged wife’s finances, because he suspected that she might have hidden sources of income. The investigators found public pictures on her Facebook profile that showed her in Aruba with friends and dining at an expensive hotel in Maui. By following her public posts on Twitter, they also learned that her family owned a successful restaurant and that she was involved in expanding the business. The investigators used these leads to discover all the wife’s assets.14

13.2 Set Up Policies Regarding the Acceptable Use of Social Media Data About Employees and Job Candidates

According to a June 2009 CareerBuilder survey (http://www.careerbuilder.com/ Article/CB-1337-Getting-Hired-More-Employers-Screening-Candidates-via-Social- Networking-Sites/), 45 percent of employers reported that they use social networking sites to screen potential employees. In the survey, 18 percent of employers said they found content on social networking sites that encouraged them to hire the candidate. Examples of favorable content included a profile that provided a good feel for the candidate’s personality and fit within the organization. On the other hand, 35 percent of employers reported they have found content on social networking sites that caused them not to hire the candidate. Examples of such unfavorable content included provocative or inappropriate photographs or information, alcohol or drug use, and bad-mouthing previous employers, co-workers, and clients.

The legal framework governing the use of social media is in a constant state of flux, as described in Case Study 13.4.

Case Study 13.4: Employers asking for Facebook accounts and passwords

In 2011, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) pursued a complaint by a corrections officer in the State of Maryland. The individual was returning from a leave of absence, and his employer asked him to provide his Facebook account and password as a condition of returning to work. The corrections department explained that they wanted to review his friends and postings, to ensure that he was not involved in any illegal activity, including gang affiliations. In response to protests, the department asked candidates to log into their Facebook accounts in the presence of their employer.

In March 2012, Facebook released a statement condemning employers for asking job candidates for their Facebook passwords. United States Senators Charles Schumer from New York and Richard Blumenthal from Connecticut asked the Department of Justice and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to investigate whether such practices violate privacy laws.

In April 2012, the state of Maryland passed a bill prohibiting employees from having to provide access to their social media content.

Employers have to grapple with conflicting regulations and duties. On the one hand, regulations in many jurisdictions prohibit employers from using information such as a candidate’s age, marital status, religion, race, and sexual orientation. Social media such as LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook are rich sources of such information. If an employer prescreens a prospective employee by consulting their LinkedIn profile, Tweets, or Facebook page, it becomes problematic to prove later on that they did not use this information to discriminate against a prospective employee. In Case Study 13.4, the corrections department could conceivably have made use of an employee’s private information to discriminate against him.

On the other hand, employers also have a duty to use all the information at their disposal to ensure that they are hiring the right employees for the job. The corrections department argued that they wanted to verify the background of their employees and prospective candidates. If the department hired a person who later turned out to have gang affiliations, it might turn out to be a public relations and legal nightmare, especially if his actions resulted in injury to inmates or other officers.

In the United States, several federal and state laws as well as other regulations could ostensibly be construed to prohibit this practice. Here are a few of these laws and regulations:15

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act forbids employers from discriminating against prospective employees based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

- The United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has further specified within this Act that employers must not discriminate against prospective employees having family responsibilities such as caring for a child, parent, or disabled family member.

- The Age Discrimination in Employment Act forbids an employer from discriminating against a job applicant who is 40 years or older.

- The Pregnancy Discrimination Act forbids employers from discriminating against prospective employees because of pregnancy.

- The Americans with Disabilities Act forbids an employer from discriminating against a prospective employee who is disabled or who is associated with others having disabilities.

- The Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act forbids employers from discriminating based on genetic test results or collecting this information.

- Facebook’s Statement of Rights and Responsibilities prohibits users from sharing their passwords or letting anyone else access their account.

As of the publication of this book, the states of Minnesota, Illinois, Washington, Massachusetts, and New Jersey are moving towards similar legislation as Maryland.16 Several international jurisdictions are also making similar moves. For example, the German government drafted legislation in late 2010 to prohibit employers from screening the Facebook profiles of job candidates. Although Canada does not yet have specific legislation targeted at social media, it does have tough privacy laws and privacy commissioners at the federal and provincial levels. In December 2011, the Office of the Information and Privacy Commission of the Canadian province of Alberta issued guidelines for social media background checks. The guidelines required organizations not to use social media to perform background checks, if doing so would result in non-compliance with the Alberta Personal Information Protection Act and the Alberta Human Rights Act.

Legislation, regulation, and case law governing the use of social media about employees and job candidates varies by country, state, and province and is continually evolving. Employers need to work with legal counsel to draft specific policies tailored to their unique situations.

13.3 Leverage Confidence Intervals to Assess the Quality of Social Media Data

Organizations that want to leverage social media need to address the following issues regarding data quality:

- “We would like to do reputation analysis based on Twitter feeds, however, we have some concerns.”

- “Will the Twitter data truly reflect the population?”

- “Are disgruntled people more likely to use Twitter?”

- “Do younger people use Twitter more often?”

- “Are affluent people more likely to use Twitter?”

- “We would like to combine social media data with our internal data. We have developed an information governance program to cleanse our internal data. How do we deal with social media data that might not be as reliable as our internal data?”

- “We are dealing with sparse data for social media.”

- We have seen reports that the Twitter handle reveals the user’s name with only 50 to 60 percent accuracy.

- We might have an idea about the person’s gender, but we cannot be sure.”

From a big data governance perspective, organizations need to use confidence levels to assess data quality. Organizations can also leverage natural language processing to discern key attributes of the user. Consider the Tweet, “My wife is thinking of buying a bike.” There is a high likelihood that the person is male, married, and likes bikes. If the person also Tweets, “Today is my birthday,” then we should be able to use the combination of date and Twitter handle to match to an existing customer identifier. Of course, it is still possible that the system will match a Twitter handle with three customer records. In that case, the organization needs to determine if there is any harm in sending an offer to all three customers.

Organizations also need to consider other aspects of social media data quality. A recent article17 recounted that Facebook knows an incredible amount about millions of people—what they like, what they want, who their friends are, and where they live. However, the article talks about intermediaries who sell Facebook “likes.” These likes are based on bundles of Facebook credentials where people are paid a small amount each time they like a company. In other cases, software robots create fake accounts that generate fake likes. Of course, Facebook is taking steps to address these issues, using a combination of automated and manual hunters to root out bad data. (Chapter 9, on data quality, reviews confidence intervals in more detail.)

13.4 Establish Policies Regarding the Acceptable Use of Cookies and Other Web Tracking Devices

We begin this section with a primer on cookies.18 A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser cookie, is usually a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a web browser while the user is browsing the website. When the user browses the same website in the future, the data stored in the cookie can be retrieved to notify the website of the user’s previous activity.

Cookies have a number of different purposes:

- Session management—Cookies were first introduced to implement shopping cart functionality, so users could store items they wanted to purchase as they navigated throughout a website. Allowing users to log into a website is a frequent use of cookies. Typically, the web server will first send a cookie containing a unique session identifier. Users then submit their credentials, and the web application authenticates the session and allows the user access to services. This way, cookies can be used to capture data related to the user during navigation, possibly across multiple visits.

- Personalization—Cookies can be used to remember information about an individual who has visited a website, in order to show relevant content in the future.

- Web analytics—Web analytics cookies (sometimes called tracking cookies) can be used to measure the effectiveness of web and digital marketing initiatives, as well as to track the browsing behaviors of Internet users. For example, if a user requests a page from the site, but the request contains no cookie, the server assumes that this is the first page visited by the user. The server then creates a random string (a unique but anonymous identifier of the user) and sends it as a cookie back to the browser, together with the requested page. From this point on, the browser will automatically send the cookie to the web server every time it requests a new page from the site. The web server then sends the page as usual, but also stores the URL of the requested page, the date and time of the request, and the cookie in a log file.

Originally, web analytics tools processed these log files to report which pages users had visited, and in what sequence, during one or more visits to the site. In the past decade, web analytics tools have instead switched to collecting data with JavaScript-based page tags that send information to the analytics server. Still, the role of cookies for analytics has not changed.

There are also a number of distinct types of cookies and other web tracking devices, including these:

- Session cookie—This cookie lasts only for the duration that a user is on a website. The web browser usually deletes session cookies when it quits.

- Persistent or tracking cookie—This cookie outlasts user sessions. This cookie can be used to anonymously identify a returning visitor to a website (or to be precise, the device being used for browsing) as the same unique visitor that had visited during previous sessions. A persistent cookie can also be used to record additional information, such as the referring web page from which the user initially came to a website.

- First-party cookie—This cookie is set with the same domain (or its subdomain) as shown in the address bar of the web browser.

- Third-party cookie—This cookie is set with a different domain than the one shown on the address bar of the web browser. For example, a user visits www. example1.com, which carries banner ads from ad.foxytracking.com. The user’s computer receives a first-party cookie from www.example1.com. In addition, a third-party cookie from ad.foxytracking.com is automatically placed on the user’s computer when the browser requests the banner ad.

When the user later visits www.example2.com, another third-party cookie may be set with the domain ad.foxytracking.com, if there are banner ads from that domain on the web page. Eventually, both of these cookies will be sent to the advertiser, who can build up a browsing history of the user across all the websites where the advertiser has a footprint.

- Flash cookie—Also known as a local shared object, this cookie includes pieces of data that are placed on a user’s computer by websites that use Adobe Flash. Unlike traditional browser cookies, Flash cookies are relatively unknown to web users, and they are not controlled through the cookie privacy controls in a browser. That means that even if a user thinks they have cleared their computer of tracking objects, they most likely have not. Websites can use Flash cookies to reinstate traditional cookies that have been deleted by a user. Therefore, even if a user gets rid of a tracking cookie, the website can reassign that cookie’s unique ID to a new cookie using the data inside the Flash cookie.19

- Web beacons—A web beacon is an object embedded in a web page or email that is usually invisible to the user, but allows checking that a user has viewed the page or email. Alternative names are web bug, tracking bug, tag, and page tag. Common names for web beacons implemented through an embedded image include tracking pixel, pixel tag, 1x1 gif, and clear gif.20

- Browser fingerprinting—This technique uniquely identifies computers and other personal devices based on a specific combination of characteristics such as system fonts, software, and installed plug-ins that are typically made available by a consumer’s browser to any website visited.21

The focal point for much of the debate about web tracking in recent years is online behavioral advertising—the practice of collecting information about consumers’ online interests in order to deliver targeted advertising to them. This system of advertising revolves around ad networks that can track individual consumers—or at least their devices—across different websites using third-party cookies. When organized according to unique identifiers, this data can provide a potentially wide-ranging view of individual use of the Internet. These individual behavioral profiles allow advertisers to target ads based on inferences about individual interests, as revealed by Internet use. Targeted ads are generally more valuable and efficient than purely contextual ads and provide revenue that supports an array of free online content and services. However, many consumers and privacy advocates are concerned that tracking and the associated advertising practices invade their expectations of privacy.22

Despite these major privacy concerns, consumer knowledge of cookies and other web tracking technologies is very limited. The United Kingdom Department for Culture, Media and Sport commissioned consulting firm PwC to conduct research into the potential impact of cookie regulation.23 The firm conducted an online survey of over 1,000 individuals in February 2011. Despite the report acknowledging that the most intensive Internet users were overrepresented in the sample, the results illustrated that significant percentages of these more “Internet savvy” consumers had a limited understanding of cookies:

- 41 percent of those surveyed were unaware of any of the different types of cookies such as first-party, third-party, and Flash. Only 50 percent were aware of first-party cookies.

- Only 13 percent of respondents indicated that they fully understood how cookies work, 37 percent had heard of Internet cookies but did not understand how they work, and two percent had not heard of Internet cookies before participating in the survey.

- 37 percent said they did not know how to manage cookies on their computers. The survey tested respondents’ knowledge of cookies, asking them to confirm if a number of statements about cookies were correct or not. Out of the 16 statements, the majority of respondents answered only one correctly.

We discuss the regulatory environment in the Europe and the United States in the remainder of this section. (Of course, the regulations are quite confusing and in a constant state of flux. Companies are well advised to consult with legal counsel.) Case Study 13.5 deals with the regulatory environment that governs the use of cookies in the European Union and the United Kingdom. These regulations also apply to other tracking mechanisms such as Flash cookies, web beacons, and clear gifs.

Case Study 13.5: The regulatory environment that governs the use of cookies in the European Union and the United Kingdom24

The United Kingdom Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations 2003 cover the use of cookies and similar technologies for storing information, and accessing information stored, on a user’s equipment such as a computer or mobile device. These regulations implemented European Directive 2002/58/ EC, which deals with the protection of privacy in the electronic communications sector.

In 2009, Directive 2009/136/EC amended this directive by requiring consent for storage or access to information stored on a subscriber’s or user’s terminal equipment—in other words, a requirement to obtain consent for cookies and similar technologies. Governments in Europe had until May 2011 to implement these changes into their own laws. Article 5(3) of Directive 2009/136/EC states the following:

Member States shall ensure that the storing of information, or the gaining of access to information already stored, in the terminal equipment of a subscriber or user is only allowed on condition that the subscriber or user concerned has given his or her consent, having been provided with clear and comprehensive information, in accordance with Directive 95/46/EC, inter alia about the purposes of the processing.

The Directive also provided for certain exceptions, as follows:

This shall not prevent any technical storage or access for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network, or as strictly necessary in order for the provider of an information society service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user to provide the service.

The UK’s Information Commissioner has provided some examples of how its regulations will affect certain scenarios. These are described in Table 13.1

| Table 13.1: Guidance from the UK’s Information Commissioner on the Anticipated Impact of Cookie Regulations |

| Activities Likely to Fall Within the Cookie Consent Exception |

Activities Unlikely to Fall Within the Cookie Consent Exception |

| A cookie used to remember the goods a user wishes to buy when he or she proceeds to the checkout or adds goods to a shopping basket |

Cookies used for analytical purposes, such as to count the number of unique visits to a website |

| Certain cookies providing security for an activity that the user has requested, such as online banking |

First- and third-party advertising cookies |

| Cookies to ensure that web pages load quickly and effectively by distributing the workload across numerous computers |

Cookies used to recognize a user when he or she returns to a website so that the a tailored greeting can be sent |

There continues to be vigorous debate about what constitutes “consent”: explicit consent (opt-in) or implied consent (opt-out). The Information Commissioner’s Office amended the regulations just hours before they were to go into effect to introduce the concept of “implied consent.”25 Here is the text of their advice:

Much of the debate around the so-called “consent for cookies” rule has focused on the nature of the consent required for compliance. Implied consent has always been a reasonable proposition in the context of data protection law and privacy regulation and it remains so in the context of storage of information or access to information using cookies and similar devices. While explicit consent might allow for regulatory certainty and might be the most appropriate way to comply in some circumstances this does not mean that implied consent cannot be compliant. Website operators need to remember that where their activities result in the collection of sensitive personal data such as information about an identifiable individual’s health then data protection law might require them to obtain explicit consent.

As of the publication of this book, several websites in the United Kingdom, such as http://www.bbc.co.uk/

and http://www.bt.com/, now allow users to modify the privacy settings for the cookies.

We now turn to the regulatory environment in the United States. Case Study 13.6 highlights the results of a Wall Street Journal investigative report regarding the bypassing of privacy settings on Apple’s Safari web browser by Google.

Case Study 13.6: Google bypassing privacy settings on Apple’s Safari web browser

In a recent investigative report,26 The Wall Street Journal found that Google and other advertising companies had been bypassing the privacy settings of millions of people who were using the Apple® Safari web browser on their iPhone devices® and computers. These companies were tracking the web browsing habits of people who had intended for that kind of monitoring to be blocked.

Although Safari was designed to block third-party cookies by default, the companies created invisible forms that tricked web browsers into letting them set first-party cookies. Google disabled its code after being contacted by The Wall Street Journal.

Compared to Europe, the regulatory environment in the United States has been considerably more lenient with respect to web privacy. However, every new highly publicized security breach is followed by renewed calls from regulators for specific legislation that governs the use of online personal data.

To ward off potentially restrictive legislation, industry groups have tried to introduce self-regulatory principles and guidelines. For example, the American Association of Advertising Agencies, the Association of National Advertisers, the Council of Better Business Bureaus, the Direct Marketing Association, and the Interactive Advertising Bureau jointly introduced self-regulatory principles for online behavioral advertising in July 2009 (http://www.iab.net/media/file/ven-principles-07-01-09.pdf). These principles are reviewed in detail in Case Study 13.7, as an example of the types of issues that organizations need to address as part of their big data governance programs.

Case Study 13.7: Self-regulatory principles for online behavioral advertising

Definition

Online behavioral advertising is the collection of web viewing data from a particular computer or device, with the objective of delivering targeted advertising based on the preferences or interests inferred from this data.

Scope

- The principles do not apply to a website’s collection of viewing behavior solely for its own uses (e.g., web analytics to measure site performance and to view customer browsing behavior).

- The principles also distinguish between online behavioral advertising and online contextual advertising. Online behavioral advertising is covered by the principles, while online contextual advertising is not. Contextual advertising is based on the content of a web page, a search query, or a user’s contemporaneous behavior on the website. An example of contextual advertising is Google serving up an ad for self-published books when I was reading an email in Gmail from my publisher that discussed the proposal for this book.

Principles

- Education calls for entities to participate in efforts to educate consumers and businesses about online behavioral advertising.

- 2.Transparency requires the deployment of multiple mechanisms for clearly disclosing and informing consumers about the data collection and use practices associated with online behavioral advertising.

- Consumer control enables users to choose whether data is collected and used or transferred to a non-affiliate for such purposes.

- Data security provides reasonable security for, and limited retention of, data collected and used for online behavioral advertising purposes.

- Material changes requires organizations to obtain user consent before applying any changes to policy regarding online behavioral advertising data collection and use.

- Sensitive data recognizes that certain data collected and used for online behavioral advertising merits different treatment. The principle applies heightened protection for children’s data by applying the protective measures set forth in the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. Similarly, this principle requires consent for the collection of financial account numbers, Social Security numbers, pharmaceutical prescriptions, or medical records about a specific individual for online behavioral advertising purposes.

- Accountability calls upon entities representing the wide range of actors in the online behavioral advertising ecosystem to develop and implement policies and programs to further adherence to these principles.

Because self-regulations lack teeth, Congress has introduced several bills that might further proscribe how organizations manage consumer data. The FTC has also committed to an effective “Do Not Track” mechanism based on support from web browser vendors, advertisers, and the industry that will empower users to control whether their data is captured or tracked.

So what does all of this mean for organizations and their own websites? In the United States, companies need to display a privacy policy on their websites that is viewable by visitors. Websites generally do not need to offer opt-out, and companies can choose to use cookies in any way they deem fit, as long as it is properly disclosed. Of course, this might change in the future based on proposals from the White House and the FTC.

Europe, on the other hand, is headed for an optin approach for website cookies. The UK amended their regulations at the last minute to allow for implied consent, as long as the website provides very clear disclosures. Although the cookie law is in effect in the UK, it appears that site owners do not need to implement opt-in for cookies, at least for the moment.

Regulations in this area are in a constant state of flux around the world, and organizations need to work closely with legal counsel.

13.5 Define Policies to Link Online and Offline Data in a Way That Does Not Violate Privacy Concerns and Regulations

Case Study 13.8 describes the big data governance policies involved in the web commerce process at a software company.

Case Study 13.8: Web commerce at a software company

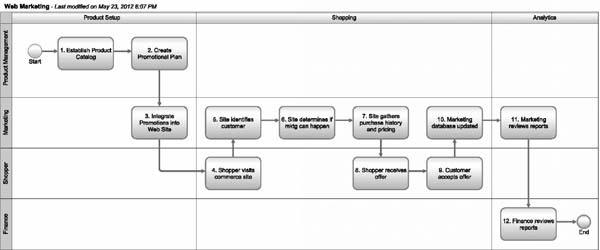

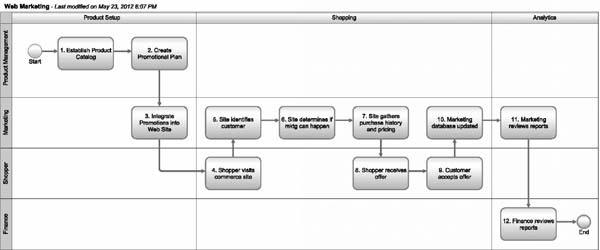

Figure 13.1: A simple process for a software company looking to use offline and online data

Figure 13.1 describes a simple process for a software company that was looking to use offline and online data to tailor offers to shoppers on its website.

There are a number of actors in the web commerce process at this company:

- Product management establishes the product catalog and creates the promotional plan, in consultation with marketing.

- Marketing manages the website, maintains the customer database, runs marketing programs of many kinds, and reviews performance reports.

- Shoppers visits the website to get information or to shop for merchandise. Shoppers can have different profiles:

- Employees of business-to-business (B2B) customers

- Business-to-consumer (B2C) customers

- Finance reviews performance reports.

The software company had to establish a number of big data governance policies relating to the web site. A mapping of the key activities and big data governance policies is described in Table 13.2.

Table 13.2: Big Data Governance Policies for the Commerce Website of a Software

Company |

| No. |

Activity |

Big Data Governance Policies |

| 1. |

Management establishes a product catalog. |

Product management develops a product catalog with the appropriate hierarchies and master data attributes. |

| 5. |

The site identifies a customer. |

The website identifies the shopper, first anonymously based on a web analytics cookie, and later based on a login when provided. |

| 6. |

The site determines if marketing can happen. |

Returning B2B customers have typically already established an online profile. Shoppers from B2B customers use this profile to optin to promotional offers when they visit the website. The website conducts a lookup in the customer database using relevant information such as the login and determines if the shopper has opted-in for marketing offers. Customer data stewards are responsible for the integrity of this data. The website honors any requests to opt-out of marketing offers. This step is not applicable to B2C shoppers. |

| 8. |

The shopper receives an offer. |

The website uses predictive models to suggest products and pricing to the shopper. The predictive models use inputs such as the following:Customer demographics if the shopper provided a login and a record already existed in the databaseCustomer firmographics that determine the characteristics of a company that lead to higher acceptance rates for offersThe visitor’s Internet domain address, especially if it belongs to a competitorExisting products owned by the shopperPrevious browsing history by the shopperPrice elasticityProduct affinities based on what the shopper already ownsContract pricing, in the case of B2B customersThese models depend on high-quality master data about customers, products, and pricing. |

| 10. |

The marketing database is updated. |

The shopper interaction history is updated to support future visits to the website and to capture offers that were not accepted. |

| 11. |

Marketing reviews reports. |

Marketing reviews reports on web traffic, shopper navigation, conversion rates, A/B testing, and basket analysis. Marketing needs consistent business definitions for terms such as “unique visitor,” “conversion event,” and “purchase event.” |

| 12. |

Finance reviews reports. |

Finance reviews reports on sales and margin. Finance needs consistent business definitions for terms such as “net sales.” Finance also needs data lineage from the reports to the data warehouse and source systems. |

The process outlined in Table 13.2 is also typical of advanced marketing efforts at B2C companies that run retargeting, retention marketing, and customer service programs. Marketing’s goal with these programs is to create a win-win scenario, where customers and prospects are presented with tailored messaged that they will hopefully find more relevant. In return, marketing efforts are likely to be more successful. In general, when companies merge web cookie-based analytics data with PII pertaining to their website visitors, the privacy policy on the website needs to include the appropriate disclosures.

13.6 Ensure the Consistency of Web Metrics

Customers might have multiple interactions with an organization’s properties across different websites, emails, and other marketing campaigns. As a result, organizations have vast quantities of online data, including browsing behaviors, searches, and responses to marketing campaigns. This data includes the following:27

- Key performance indicators that measure site performance against top-level business goals (e.g. sales, lead registrations, advertising revenue, customer selfservice success)

- Transaction metrics (e.g., sales, items per order, average order value)

- Conversion metrics (e.g., conversion rate, shopping cart sessions, shopping cart conversion rate, shopping cart abandonment rate)

- Session traffic (e.g., average session length, bounce rate where the visitor only viewed one page before leaving the site, page views per session, product views per session)

- Lifetime value metrics (e.g. repeat visitors, RFM—Recency, Frequency, and Monetary—data, 2x buyers, 3x-5x buyers)

- Mobile device metrics (e.g., mobile percentage of sales, mobile percentage of site traffic, mobile bounce rate, Android traffic, iPhone traffic, iPad® traffic)

- Social media referral metrics (e.g., social media percentage of sales, social media percentage of traffic, Facebook referral traffic, Twitter referral traffic, Pinterest referral traffic)

Big data governance programs often struggle with reconciling absolute numbers between web sites that use inconsistent methodologies. Here are some reasons for the inconsistencies:28

- Inconsistent terminology in the online world

Two websites might measure sessions differently. One site might measure a user’s interaction with more than 30 minutes of inactivity between clicks as multiple sessions, whereas another site might have a different time threshold before sessions are cut off.

- Inconsistent terminology in the offline world

Web analytics data often needs to be married with offline data. However, this can be challenging if terms such as “high value customer,” “prospect,” and tenured customer” are defined inconsistently.

- Page tags not loaded due to errors

A page tag is a piece of code in a web page that points to a library that executes some other code. Page tags have a number of functions, such as capturing the fact that a user visited a page. Most web pages have multiple, sometimes dozens, of page tags. Inconsistencies are introduced when not all the page tags are loaded before the user moves to another page.

- Tracking techniques

One website might use log files for its web analytics data collection, while another might use page tags. Alternatively, one website might use first-party cookies, while another might use third-party cookies. In either case, numbers measured will vary widely as each of these data-collection approaches has different blind spots.

- Analytic tool differences

It is commonly accepted that no two web analytic tools will produce precisely the same metrics based on the same underlying dataset. Inconsistencies arise from many sources “under the hood,” such as how each tool groups clicks into sessions. One tool might consider a session as having ended when a visitor leaves the website to do a search and then returns to the site, while another might consider that the same session.

The big data governance team needs to ensure that users understand the definitions, methodologies, and shortcomings of all web analytics information. Case Study 13.9 provides an example of clickstream data governance at a website that provides information services.

Case Study 13.9: Clickstream data governance at a web information services provider

A small web-based information services provider grappled with the governance of its clickstream data. Although the company was small, its website was highly trafficked. The company’s web properties generated about 2.5 terabytes of clickstream data each month, which was growing by 50 percent per year.

The team grappled with changes to page tags on a regular basis. In one instance, 25 page tags executed on a single page, an especially high number because the company’s revenue model was advertising supported. When they added a new ad network, they dropped two tags and added three tags, which meant that they now had 26 tags on a given page. However, the rollout was inconsistent. For example, some pages were accidentally left off the update, which led to inconsistent outcomes. In another instance, the teams stopped using a page but reused page identifiers, leading to analytics reports comparing apples to oranges for the same page identifier. The business intelligence team also grappled with lack of ownership for key business terms. After much negotiation, the marketing team assumed ownership over metrics.

Summary

Social media and web data have tremendous value in terms of improving the overall engagement with customers. However, organizations need to exercise the appropriate governance with respect to issues such as privacy, data quality, and metadata to get the most benefit from this valuable information.