Dermatology

HISTOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The skin is divided into the dermis and the overlying epidermis. The cellular component of the dermis consists of fibroblasts, adipocytes, and macrophages. The majority of the dermis, however, is acellular connective tissue composed primarily of type 1 collagen (for strength), elastin (for flexibility), and glycosaminoglycans. The dermis is mechanically responsible for cushioning the body and is also the site of the skin’s adnexal structures, lymphatics, nerve fibers, and blood vessels. The superficial location of these blood vessels is particularly important in thermoregulation because vasodilation allows for increased heat loss to the environment.

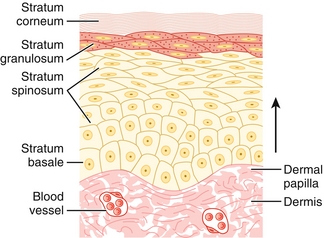

The epidermis is the most superficial layer of skin and consists primarily of keratinocytes arranged as stratified squamous epithelium. Melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells can also be found in the epidermis (see below). The deepest epidermal layer is the stratum basale, which contains keratinocyte stem cells resting on a basement membrane. These cells divide and migrate upward to populate the stratum spinosum, where keratinization begins. The cells continue to migrate superficially as they mature. After they have reached the stratum granulosum, cross-linking of keratin continues, organelles begin to disappear, and the keratinocytes produce lamellar bodies (lipid-containing secretions that form a hydrophobic membrane). In areas with thick skin, such as the palms and soles, the next layer is called the stratum lucidum (clear layer). It consists of densely packed cells that appear transparent under the microscope. Lastly, cells join the stratum corneum, where their nuclei are completely absent and keratin has formed a watertight barrier (Fig. 3-1). From superficial to deep, the skin layers are: corneum, lucidum (in thick skin), granulosum, spinosum, basale. Mnemonic: Californian ladies give superb backrubs.

Figure 3-1 Layers of the epidermis. In thick-skinned areas such as the palms and soles, the stratum lucidum separates the stratum corneum and stratum granulosum. (From Burns ER, Cave MD. Rapid Review Histology and Cell Biology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.)

The skin has two major functions: thermoregulation and protection. Thermoregulation is accomplished through vasodilation or vasoconstriction of superficial arterioles (i.e., in hot conditions, arterioles dilate and shunt blood toward the skin surface, allowing for heat loss to the environment). Eccrine glands also promote heat loss through evaporation of sweat. The barrier function of skin is not only mechanical (keratinization) and immunologic (Langerhans cells), but also chemical because ultraviolet (UV) light is converted to harmless heat using melanin.

Melanocytes

Epidermal cells that produce melanin and package them within melanosomes, which can be phagocytosed by surrounding keratinocytes. By the process of internal conversion, melanin converts mutagenic UV radiation into harmless heat. It is also responsible for the color of an individual’s skin. Those with darker skin tones, however, do not have more melanocytes; they produce melanosomes in greater number and size with greater distribution among keratinocytes. Melanocyte activation is under neurohormonal control of melanocyte-stimulating hormone, a cleavage product of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). It is not surprising, then, that the elevated ACTH in patients with Addison disease causes them to have darker skin.

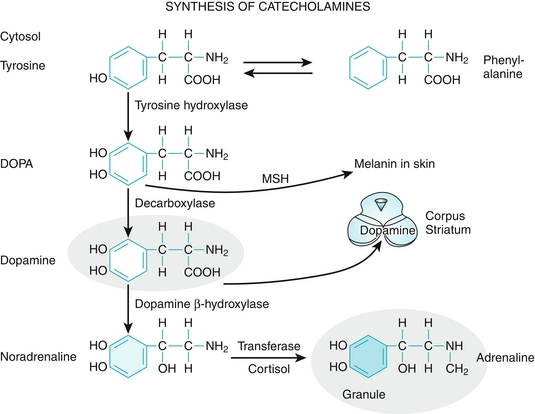

Of note, melanin is synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine. It is not just responsible for coloring the skin, but also the iris, the hair, and the substantia nigra of the brainstem (neuromelanin is a metabolite of dopamine and norepinephrine, which are also synthesized from tyrosine) (Fig. 3-2). Therefore, melanoma can arise in any of these areas.

Of note, melanin is synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine. It is not just responsible for coloring the skin, but also the iris, the hair, and the substantia nigra of the brainstem (neuromelanin is a metabolite of dopamine and norepinephrine, which are also synthesized from tyrosine) (Fig. 3-2). Therefore, melanoma can arise in any of these areas.

Langerhans Cells

Dendritic antigen-presenting cells that populate the dermis and epidermis (essentially the macrophage of the skin). After they have taken up antigen, they become active and migrate to lymph nodes, where they can interact with T and B cells. In this way, they act as a link between innate immunity and adaptive immunity. Of note, Langerhans cells in the mucosa of the vagina and foreskin are thought to be the initial target of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Merkel Cells

Sensory neuroendocrine cells found in the stratum basale of the epidermis that communicate with large, myelinated sensory afferents. They are responsible for fine touch (see Chapter 13).

Adnexal Structures

Eccrine Glands

Sweat glands that cover the majority of the human body and participate in thermoregulation by secreting hypotonic NaCl for evaporation. They are stimulated by cholinergic fibers in the sympathetic nervous system.

Of note, anticholinergic medications and toxins such as atropine inhibit cholinergic stimulation of eccrine sweat glands and produce vasodilation of peripheral vessels, leaving the patient dry as a bone and red as a beet (see toxicology section of Chapter 7).

Of note, anticholinergic medications and toxins such as atropine inhibit cholinergic stimulation of eccrine sweat glands and produce vasodilation of peripheral vessels, leaving the patient dry as a bone and red as a beet (see toxicology section of Chapter 7).

Apocrine Glands

Sweat glands that are found only in the axillae, genitoanal region, and areolae. They are activated at puberty and produce a viscous, protein-rich fluid that takes on its characteristic odor when metabolized by local bacteria. These are vestigial remnants of the mammalian sexual scent gland and serve no apparent function.

Pilosebaceous Unit

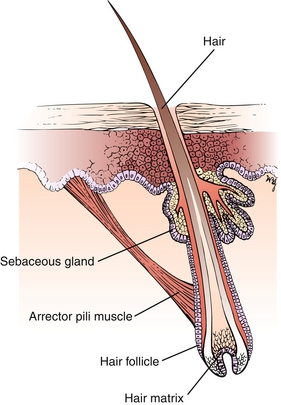

The hair fiber is composed of keratin that grows directly from the hair matrix (Fig. 3-3). The arrector pili muscle is responsible for piloerection (“goose bumps,” a vestigial response to cold). The sebaceous glands produce sebum, which oils the skin and hair, preventing them from drying. Furthermore, sebum is somewhat toxic to bacteria. Sebaceous glands are activated during puberty and are responsible for acne vulgaris.

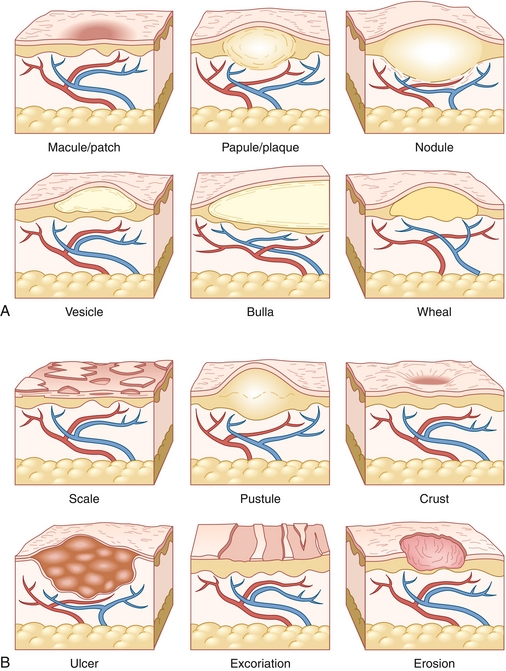

Describing Lesions

A standard terminology has been defined to verbally express dermatologic findings. These can be divided into primary lesions (Table 3-1 and Fig. 3-4A) and secondary lesions (Table 3-2 and Fig. 3-4B). Secondary lesions derive from primary lesions and are caused by trauma, evolution, or other modification of the primary lesion. Table 3-3 explains common histologic terms that describe dermatologic lesions.

Table 3-1

| Name | Description | Example |

| Macule | Flat lesion < 0.5 cm | Ephelides (freckles) |

| Patch | Flat lesion > 0.5 cm | Vitiligo Melasma |

| Papule | Raised lesion < 0.5 cm | Acne vulgaris Rosacea |

| Plaque | Raised lesion > 0.5 cm | Psoriasis |

| Vesicle | Fluid-filled blister < 0.5 cm | Herpes simplex |

| Bulla | Fluid-filled blister > 0.5 cm | Bullous pemphigoid Pemphigus vulgaris |

| Pustule | Pus-filled lesion | Acne vulgaris Rosacea |

| Nodule | Firm or indurated lesion usually located in the dermis or subcutaneous fat. May or may not be raised | Erythema nodosum |

| Wheal | Dermal edema leading to a raised, erythematous, pruritic lesion lasting < 24 hr | Urticaria (hives) |

Table 3-2

| Name | Description | Example |

| Excoriation | Trauma to skin caused by scratching. Characterized by linear breaks in the epidermis | Scabies |

| Lichenification | Thick, rough area with accentuated skin lines; usually the result of repeated trauma or scratching | Eczema |

| Crust | Dried collection of serum, blood, pus, epithelial cells, and/or bacteria | Impetigo (honey-colored crust) |

| Scale | Fragment of stratum corneum (keratin) atop or peeling from the rest of the epidermis. Often secondary to rapid epidermal turnover | Psoriasis (silvery scale) |

| Erosion | Incomplete loss of epidermis causing shallow, moist, and well-circumscribed lesion | Pemphigus vulgaris (secondary to ruptured bullae) |

| Ulceration | Complete loss of epidermis with or without destruction of subcutaneous tissue and fat | Basal cell carcinoma (may have central ulceration) |

Table 3-3

| Name | Description | Example |

| Hyperkeratosis | Thickening of the stratum corneum | Callus |

| Parakeratosis | Thickening of the stratum corneum with persistence of nuclei (normally absent at this layer) | Psoriasis |

| Acanthosis | Thickening of stratum spinosum | Acanthosis nigricans |

| Acantholysis | Separation of keratinocytes due to loss of intercellular cohesion | Pemphigus vulgaris |

PATHOLOGY

Common Dermatologic Conditions

Acne Vulgaris

The formation of a comedone occurs in a four-step process:

1. Hyperproduction of sebum within a sebaceous gland.

2. Formation of a plug blocking the pilosebaceous unit.

3. Inflammatory reaction to Propionibacterium acnes; an anaerobic bacterium, and a component of skin flora.

4. Follicular wall rupture and spread of perifollicular inflammation.

Sebum’s exposure to air causes oxygenation of sebum and an open comedone (blackhead). Persistent occlusion leads to accumulation of sebum and a closed comedone (whitehead). Treatment often begins with topical retinoids and/or topical antibiotics, including benzoyl peroxide. Oral doxycycline or tetracycline may be used for moderate acne. Isotretinoin (Accutane) is reserved for nodulocystic acne.

Rosacea

Clinically and on Step 1, your job often will be to distinguish this condition from acne vulgaris. Like acne, rosacea may cause red papules and pustules on the face; however, the age group is generally an easy clue for rosacea because it is more likely to occur de novo in patients older than 30 years (Fig. 3-5). Distinguishing features also include telangiectasias (which blanch), rhinophyma (a bulbous erythematous nose), and a lack of comedones. A trigger is often associated with the condition; such triggers include extreme temperatures or winds, strenuous exercise, severe sunburn, and certain foods such as alcohol, caffeinated beverages, and spicy foods. Usual treatment is with topical antibiotics such as metronidazole or oral antibiotics such as the tetracyclines. In a patient older than 30 years with new-onset papules and pustules with strong environmental triggers, think rosacea before acne vulgaris. The etiology of rosacea is unclear, but it is thought to be from a pathologic interaction between the innate immune system and skin microbes.

Lichen Planus

Inflammatory lesions of the skin of unknown etiology but sometimes associated with hepatitis C infection. This condition is remembered and recognized by the 4 Ps mnemonic: purple, polygonal, pruritic papules (Fig. 3-6). Treatment usually involves high-potency topical steroids. It may be associated with Wickham’s striae (whitish lines visible in the papules) and the Koebner phenomenon (new lesions that appear along lines of trauma; usually in linear patterns after scratching).

Pityriasis Rosea

Thought to be secondary to a virus, this dermatologic condition may begin with a virus-like prodrome and a herald patch—a raised oval, pink patch with central clearing (Fig. 3-7). It appears on the trunk and may be confused with tinea corporis. The herald patch is followed 7 to 14 days later by multiple lesions similar in appearance but smaller. They form on the back and follow skin cleavage lines in a “Christmas tree” pattern. No treatment is necessary because the condition is usually self-limited.

Keloid

Firm, shiny nodule of scar tissue (type 1 collagen) as a result of granulation tissue (type 3 collagen) overgrowing the boundaries of a wound. Keloids overgrow the boundaries of the initial injury, unlike hypertrophic scars, which are raised scars that respect wound margins. Keloids are common in African American individuals.

Contact Dermatitis

A delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction in which antigen absorption recruits previously sensitized T cells to initiate local inflammation. Lesions are well-circumscribed, erythematous plaques that may have vesicles or bullae over the area of exposure (Fig. 3-8). Common allergens include poison ivy, rubber, and nickel. Nickel can be found in jewelry and buttons, and the distribution of rash matches the area of contact. Treatment involves avoidance of the culprit allergen and topical steroids applied to any affected area. Systemic steroids may be needed in severe cases. After an exposure, contact dermatitis often takes days to develop. Consider a type 1 immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated reaction if development of rash (often urticaria) immediately follows an exposure (e.g., latex).

Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema)

Known as “the itch that rashes” because symptoms begin as itching that erupts into an erythematous, scaling lesion (Fig. 3-9). Vesicles may be present early, and lichenification occurs if the area is aggressively scratched. In adults, the distribution is in flexural areas (antecubital and popliteal fossae) and on the hands. The face and body may be affected in children. The etiology involves an overlap between genetics, environment, and the immune system. The terms atopic march and atopic triad describe the other hypersensitivity comorbidities that patients may later develop: eczema → asthma → allergic rhinitis. Treatment of eczema involves protecting the skin from excessive drying, avoiding irritants, and applying topical steroids and moisturizers (emollients).

Urticaria (Hives)

Pruritic wheals caused by mast cell degranulation spilling histamines and other inflammatory mediators into the surrounding tissue. Acute urticaria (< 6 weeks) is often secondary to an environmental allergy, whereas chronic urticaria is thought to be an autoimmune condition. Initial treatment is with second-generation H1-antagonists (antihistamines).

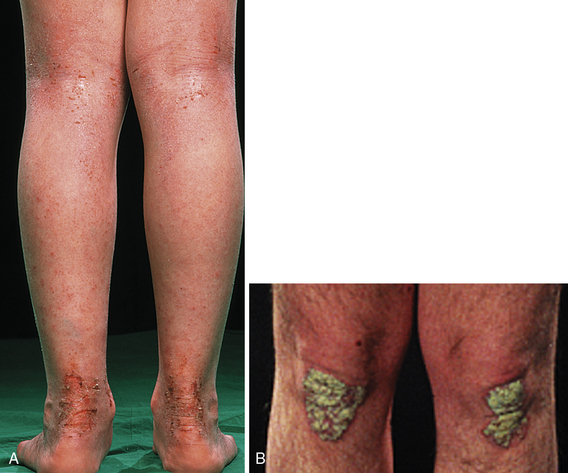

Psoriasis

This disorder is caused by an interaction between the environment and genetics (HLA-B27) that causes a local inflammatory reaction and hastens the growth cycle of the epidermis, leading to thickened skin from keratinocyte accumulation at affected sites. Histology reveals hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Clinically, psoriasis presents as red papules with silvery scales that coalesce into well-defined plaques, often on extensor surfaces (elbows and knees) (Fig. 3-10). Lesions may develop on sites of previous trauma (Koebner phenomenon). Peeling of the scale will reveal pinpoint bleeding (Auspitz sign). Psoriasis can also affect nail beds (pitting) and joints (psoriatic arthritis). Treatment of skin lesions involves topical steroids. Systemic steroids should be avoided because initial improvement is often followed by a rebound phenomenon upon tapering. Severe psoriasis may necessitate stronger agents such as methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors. The rash of psoriasis is usually improved with sunlight exposure.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X)

Abnormal proliferation of histiocytes. On the skin this condition presents as red papules on the scalp or trunk that may display crusting or scaling. Painful osteolytic bone lesions of the skull are also characteristic. Lung nodules may also occur accompanied by cough. Skin biopsy will reveal Langerhans cells, which are very large (about four times larger than a lymphocyte). Although this is a confusing disease that may affect many organ systems, on Step 1 the key diagnostic feature is often the presence of Birbeck granules on electron microscopy—tennis racket–shaped organelles within the cell (Fig. 3-11).

Figure 3-11 Arrow pointing to Birbeck granule seen on electron microscopy of a Langerhans cell. (From Goljan EF. Rapid Review Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. Courtesy of William Meek, Professor and Vice Chairman of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Oklahoma State University, Center for Health Sciences, Tulsa, OK.)

Autoimmune Diseases

Pemphigus Vulgaris

A severe autoimmune bullous condition caused by IgG antibodies within the epidermis that attack desmosomes and lead to a loss of adhesion between keratinocytes (acantholysis). The clinical result is the formation of painful, superficial, flaccid, intraepidermal bullae. These bullae may expand on gentle stroking normal-appearing adjacent skin (Nikolsky sign) and may rupture, leading to erosions (Fig. 3-12). Unlike with bullous pemphigoid (see later), there is frequently mucous membrane involvement (on examinations, oral involvement of disease is the most common clue that this represents pemphigus vulgaris and not bullous pemphigoid). Immunofluorescence reveals IgG deposits between keratinocytes. Treatment includes use of systemic steroids and supportive measures to maintain homeostasis (often treated like severe burn patients).

Bullous Pemphigoid (BP)

A less severe autoimmune condition in which antibodies attack hemidesmosomes, which connect epidermal basal cells to the basement membrane. Binding of complement leads to destruction of the basement membrane, separation of the dermoepidermal junction, and the formation of subepidermal blisters. Clinically this creates the appearance of tense bullae and subsequent erosions at the site of ruptured bullae (Fig. 3-13). BP typically presents in older adults, and unlike with pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membranes are rarely involved, and Nikolsky sign is negative. The etiology of this condition is unknown, although it may be triggered by initiation of culprit medications. BP is relatively mild compared with other bullous diseases and often responds to topical steroids alone. Mnemonic: antibodies in bullous pemphigoid line up “bulow” (below) the basement membrane and bullous pemphigoid is “bulow” pemphigus vulgaris in severity).

Conditions of Pigmentation

Vitiligo

Autoimmune condition in which antibodies destroy melanocytes within the epidermis. The subsequent absence of melanin leads to depigmentation in flat, well-circumscribed macules or patches. This condition may occur in any race but is more noticeable in dark-skinned individuals. Depigmented areas fluoresce under a Wood lamp (ultraviolet light), which can help detect depigmentation in light-skinned individuals. Vitiligo should not be confused with tinea versicolor, which causes hypopigmentation, not depigmentation. Key feature: absent melanocytes.

Albinism

Autosomal recessive inability to convert tyrosine into melanin (usually due to nonfunctional tyrosinase enzyme). Patients have pale skin, white hair, and blue eyes. The risk for skin cancer is extremely high in these individuals. Key feature: decreased melanin.

Solar Lentigo

Also known as lentigo senilis and “old-age spots.” These benign lesions are areas of increased pigmentation, often seen in older patients who have had years of UV-light exposure. Key feature: increased melanocytes.

Melasma

Estrogen and progesterone stimulate melanocytes during pregnancy or oral contraceptive use to increase production of melanin. Hyperproduction of melanin causes formation of hyperpigmented macules and patches on sun-exposed areas. Also known as the “mask of pregnancy,” this condition is only of cosmetic concern. Key feature: increased melanin.

Neoplasms, Dysplasias, and Malignancies

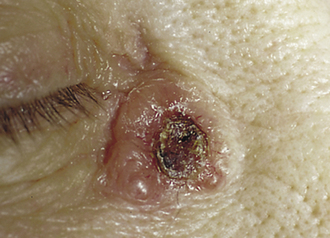

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

The most common human malignancy. As the name implies, BCCs develop in the stratum basale, often as a result of UV-induced DNA damage. Patients present with lesions on sun-exposed areas that are characteristically pearly nodules with rolled edges (Fig. 3-14). Central ulceration and overlying telangiectasias also may be present. Diagnosis can be confirmed with biopsy, which reveals nests of basal cells demonstrating peripheral palisading. BCCs are treated with excision. The prognosis is extremely good because these cancers do not metastasize. They are locally invasive, however.

Actinic Keratosis (AK)

Precancerous, dysplastic lesion characterized by excessive keratin buildup forming crusty, scaly, rough, papules. They tend to occur in sun-exposed areas and may progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Diagnosis is based on physical exam, although lesions suspicious for SCC should be biopsied. AKs are usually treated with cryotherapy or topical 5-fluorouracil.

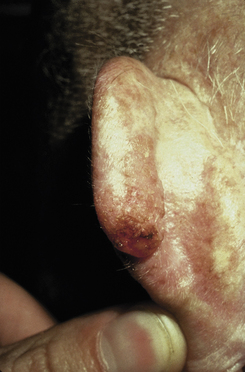

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

Patients present with scaling plaques in sun-exposed areas (Fig. 3-15). Histology reveals keratin pearls. Lesions are locally invasive, and unlike BCCs can occasionally metastasize. Risk factors include sun exposure, immunosuppression, arsenic exposure, and chronic draining sinus tracts (e.g., from osteomyelitis). SCCs also have a tendency to grow on areas of scarring; an aggressive, ulcerative SCC that grows in an area of previous scarring or trauma is called a Marjolin ulcer. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a specific term for SCC in situ on the glans penis, usually secondary to infection with high-risk human papillomavirus serotypes 16 and 18. This subtype of SCC tends to present as a velvety-smooth, red plaque.

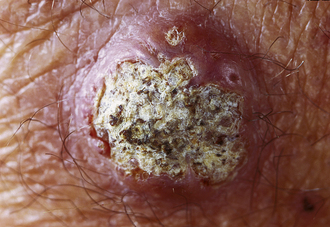

Keratoacanthoma

Controversially considered a subtype of SCC; this lesion is rapidly growing and forms a dome with keratin scales and debris atop it (Fig. 3-16).The lesion often grows so large so quickly that it outstrips its blood supply, necroses, and resolves with some scarring.

Melanoma

A malignant tumor of melanocytes recognized clinically by the ABCDEs: asymmetry, borders (irregular), color (variance), diameter (> 6 mm), and evolution (growing, changing color, becoming pruritic). Melanomas are most likely to metastasize if they enter a vertical phase of growth; therefore, depth of invasion is correlated with mortality. Their precursor lesion is the dysplastic nevus, which may display some of the above features and should be biopsied. This cancer has a positive S-100 tumor marker, which is consistent with melanocytes’ derivation from neural crest cells.

Seborrheic Keratosis (SK)

Classically a warty, stuck-on appearing lesion formed by a benign proliferation of keratinocytes. Plugs of keratin are visualized on histology, although these lesions need not be biopsied. Of note, the sign of Leser-Trélat refers to a paraneoplastic phenomenon with an eruptive presentation of multiple SKs, indicating an underlying malignancy (especially gastric adenocarcinoma).

Strawberry Hemangioma

Benign vascular tumor that appears in the neonatal period and slowly involutes during childhood. No treatment is required unless it ulcerates or is near vital structures like the eye (Fig. 3-17).

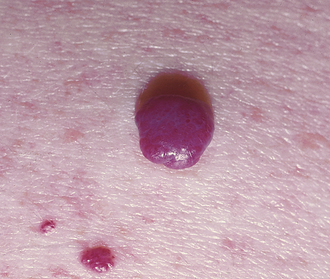

Cherry Hemangioma

A benign proliferation of capillaries. They are more common with age and require no treatment; however, they will not involute on their own (Fig. 3-18).

Skin Infections and Infestations

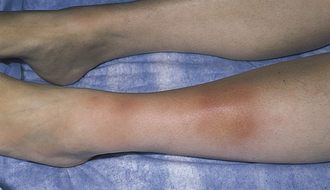

Cellulitis

Infection of deep dermal and subcutaneous tissue often caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes. Infection is often from direct penetration of bacteria into the skin. Cellulitis presents as a streaky, painful, warm, erythematous, edematous lesion with or without fever. Because the infection is deep, the margins of the infection are typically not well defined (which separates this from erysipelas, a more superficial infection with more well-defined borders). Treatment is with antibiotics.

Erysipelas

Similar to cellulitis, although infection is of the superficial dermis and lymphatics as opposed to deeper involvement. Erysipelas more commonly occurs in children and those with impaired lymphatic drainage. S. pyogenes is the most common pathogen. The lesion is well circumscribed with raised borders (Fig. 3-19B).

Impetigo

S. aureus or S. pyogenes infection of the face, which begins as vesicles and pustules that later rupture, producing the characteristic honey-colored crust (Fig. 3-19A). Bullous impetigo is similar, but the initial lesions are flaccid bullae filled with transparent yellow fluid. Of note, if the causative organism is S. pyogenes, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) is a potential complication, but not acute rheumatic fever (which only appears after S. pyogenes pharyngitis). PSGN cannot be prevented with antibiotics, so treatment only affects the skin condition and does not prevent complications.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS)

A severe and generalized form of bullous impetigo. S. aureus skin infection produces exfoliative exotoxin, a protease that acts on desmoglein at the stratum granulosum to produce tense intraepidermal bullae followed by flaky, nonscarring desquamation. This condition occurs predominantly in neonates and is often accompanied by fever. Note that the desmoglein of desmosomes is the target in both SSSS and pemphigus vulgaris.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

“Flesh-eating,” rapidly progressive infection of subcutaneous tissue including fat and fascia that spreads along fascial planes. The cause may be either polymicrobial or monomicrobial. S. pyogenes is the most likely single organism. Necrotizing fasciitis often spreads from a site of local trauma or surgery. Clinically, it is similar to cellulitis but is characterized by extreme pain, fever, induration (hardening of skin), and skip lesions (noncontinuous islands of infected tissue). Sepsis is common. Treatment involves intravenous antibiotics and surgical débridement. Gas gangrene is a similar condition caused by infection with Clostridium perfringens. In this infection, crepitus (crackling sensation on palpation) may also result from CH4 and CO2 production by the pathogen.

Dermatophytes

Superficial fungal infections of the skin or nails in which the fungus survives by metabolizing keratin. These infections are caused by Epidermophyton, Microsporum, and Trichophyton species. Infections are named for their location on the body (e.g., tinea capitis on the head, tinea pedis on the foot, tinea corporis on the body, and tinea cruris on the groin). Tinea corporis presents as a raised, erythematous, oval “ring worm.” KOH prep can be confirmatory by demonstrating the presence of hyphae. Treatment is with topical antifungals. Topical steroids should be avoided because they can exacerbate the infection.

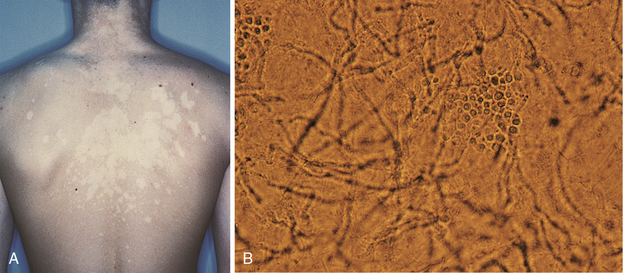

Tinea Versicolor

Superficial fungal infection with Malassezia globosa or Malassezia furfur that causes hypopigmented or hyperpigmented macules and patches with possible associated scaling (Fig. 3-20A). Lesions generally occur on the trunk and arms. KOH prep reveals a spaghetti and meatballs appearance of the hyphae and yeast, respectively (Fig. 3-20B).

Figure 3-20 A, Hypopigmented patches of tinea versicolor. B, Tinea versicolor KOH prep revealing “spaghetti and meatball” appearance of the hyphae and yeast. (A, from Swartz MH. Textbook of Physical Diagnosis. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. B, from Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.)

Scabies

A superficial infection with the parasite Sarcoptes scabiei, which burrows into the skin to live and reproduce. The mite is spread through person-to-person contact. The most profound feature of scabies is severe pruritus caused by a delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction to the mites, their eggs, and their feces. The rash usually consists of erythematous papules with secondary excoriations; however, the burrow is pathognomonic and appears as a thin raised line along the skin (Fig. 3-21B). Crusted (formally Norwegian) scabies is a severe infestation that is associated with immunosuppression (e.g., from AIDS). Mineral oil prep may be confirmatory by direct visualization of the mites or eggs. Topical permethrin is the initial treatment of choice.

Figure 3-21 Scabies. A, Burrow pathognomonic of Sarcoptes scabiei. B, Erythematous papules with excoriations in an immunocompromised patient with severe crusted scabies. (A, from Fitzpatrick JE, Morelli JG. Dermatology Secrets in Color. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2000. Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD. B, from Swartz MH. Textbook of Physical Diagnosis. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.)

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

White “hairy” patch found on the side of the tongue caused by opportunistic infection of Epstein-Barr virus. The presence of leukoplakia should be concerning for HIV. This lesion can be distinguished from thrush/oral candidiasis (caused by Candida albicans) because leukoplakia cannot be scraped off easily and tends to occur on the sides of the tongue. Oral candidiasis can occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals. Esophageal candidiasis, on the other hand, is highly concerning for immunosuppression and is considered an AIDS-defining illness.

Leukoplakia

White patch on the tongue or oral mucosa secondary to squamous hyperplasia. Like oral hairy leukoplakia, this lesion will not scrape off. It is considered precancerous because some cases may progress to squamous cell carcinoma. It is highly associated with tobacco use (especially smokeless tobacco). Treatment is with cessation of any carcinogenic habits and/or surgical removal.

Dermatologic Manifestations of Internal Disease

Erythema Nodosum

Inflammatory condition of subcutaneous fat (panniculitis) resulting in tender erythematous nodules, often over the shins (Fig. 3-22). Associated especially with streptococcal infection, drugs, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and fungal infections.

Erythema Multiforme

Multiple target-shaped lesions with “multiform” primary lesions (macules, papules, vesicles) (Fig. 3-23). Commonly a hypersensitivity reaction to drugs leading to IgM deposition in the skin, but erythema multiforme may also be secondary to infection or malignancy.

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Erythema multiforme, but with more extensive and systemic symptoms, including mucous membrane involvement, fevers, diffuse erosions, and crusting. Lesions must cover < 10% of the body surface area. It is associated with a high mortality rate.

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

A more severe form of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with lesions covering > 30% of the body surface area. These conditions overlap when 10% to 30% of the body surface is involved.

Erythema Marginatum

Nonpruritic, erythematous, transient, ringed lesions of the trunk. This rash is one of the major criteria for rheumatic fever.

Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Expanding bull’s eye–shaped erythematous plaque at site of Ixodes tick bite and pathognomonic of early, localized Lyme disease (Fig. 3-24). Caused by localized infection with Borrelia burgdorferi (not hypersensitivity). Multiple lesions indicate the spirochete has spread hematogenously. Treatment is with doxycycline.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis

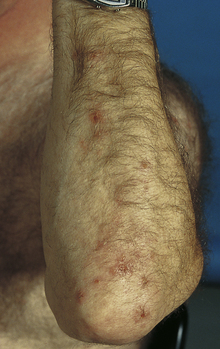

Pruritic vesicles and papules on an erythematous base (herpetiform), especially over extensor surfaces (elbows and knees). Caused by dermal IgA deposits in association with celiac disease. This condition is responsive to a gluten-free diet. (Fig. 3-25)

Acanthosis Nigricans

Velvety hyperpigmentation of skin overlying body folds associated with elevated insulin levels, which alter dermatologic growth factors (Fig. 3-26). Elevated insulin is most commonly a result of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Other endocrine disorders, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, may also be causative.

Stasis Dermatitis

Brawny discoloration of dependent areas (feet and ankles) due to hemosiderin deposits from extravasation of erythrocytes as a result of venous hypertension (Fig. 3-27). Pedal edema is often present. The venous hypertension may simply be due to venous valve dysfunction, but heart failure may also be the underlying cause.

PHARMACOLOGY

Retinoids

Vitamin A–related compounds that act as steroid hormones to alter gene transcription. These compounds bind nuclear retinoic acid receptors, which then activate promoter regions of DNA, leading to transcription of retinoid-sensitive genes. In the treatment of acne, the result is a decrease in size and sebum output of sebaceous glands. Topical retinoids are often used for the initial management of acne. Systemic isotretinoin, however, is reserved for nodulocystic acne owing to its severe side-effect profile, including hepatotoxicity and teratogenicity (causes embryologic and fetal malformations).

Permethrin

Antiparasitic agent used in the treatment of scabies and head lice (Pediculosis capitis). In arthropods, permethrin acts as a neurotoxin by prolonging sodium channel activation, thereby causing paralysis and death. It is poorly absorbed and easily inactivated in humans.

Topical Antifungals

Azoles: Inhibit an enzyme (14α-demethylase) responsible for formation of ergosterol (component of fungal membrane). Common agents for treatment of dermatophytes and tinea versicolor include clotrimazole (Lotrimin), miconazole, and ketoconazole.

Azoles: Inhibit an enzyme (14α-demethylase) responsible for formation of ergosterol (component of fungal membrane). Common agents for treatment of dermatophytes and tinea versicolor include clotrimazole (Lotrimin), miconazole, and ketoconazole.

Terbinafine (Lamisil): Inhibits a different enzyme (squalene epoxidase) responsible for formation of ergosterol. Topically, terbinafine is a first-line agent for dermatophytes. It can also be used orally in the treatment of onychomycosis (fungal nail infection).

Terbinafine (Lamisil): Inhibits a different enzyme (squalene epoxidase) responsible for formation of ergosterol. Topically, terbinafine is a first-line agent for dermatophytes. It can also be used orally in the treatment of onychomycosis (fungal nail infection).

Topical Steroids

Inhibit local inflammatory reaction by interfering with the production of inflammatory cytokines by phospholipase A2. They are used in the treatment of lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, pemphigus vulgaris, and bullous pemphigoid, among others. Common topical steroids include hydrocortisone, triamcinolone, and clobetasol.

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)

Topical and systemic chemotherapeutic agent. 5-FU is a thymine (pyrimidine) analogue that irreversibly inhibits thymidylate synthase, thus preventing DNA synthesis (see Chapter 11 for details). Used topically, it is one of the first-line therapies for actinic keratoses (cryotherapy is also a first-line treatment). 5-FU causes a local inflammatory response on the skin that may require interruption of treatment. Intravenously, it is used in the treatment of solid malignancies such as breast and colon cancer.