Psychiatry

PSYCHOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT

Theories of Learning

The concept of operant conditioning says that we may learn a variety of things based on the rewards or negative consequences of our actions. We may learn to acquire a strong drive in education because our loving parents give us hugs and new shiny toys when we bring home A’s on our report cards; giving rewards is referred to as positive reinforcement. Or, we can learn to share toys with other kids in school because, if we don’t, they call us nasty names. This is called positive punishment. This may be confusing at first (after all, what’s so positive about calling someone mean names?), so let’s break it down.

Positive: Giving something (“adding something”) to the person as a consequence. You can give something good or something bad.

Negative: Taking away something (“subtracting something”) from the person as a consequence. You can take away something good or something bad.

Reinforcement: You like what the person did and would like them to keep doing that behavior. You want to reinforce this learning and make it stronger.

Reinforcement: You like what the person did and would like them to keep doing that behavior. You want to reinforce this learning and make it stronger.

Positive reinforcement: Giving a child candy for cleaning up his toys

Positive reinforcement: Giving a child candy for cleaning up his toys

Negative reinforcement: Taking away a teen’s chores as a reward for doing well on a math test

Negative reinforcement: Taking away a teen’s chores as a reward for doing well on a math test

Punishment: You don’t like what the person did and want them to learn that it is a bad behavior.

Punishment: You don’t like what the person did and want them to learn that it is a bad behavior.

Reinforcement schedules add an additional layer of complexity to operant conditioning. Although it might sound nice and fair to reward children every time they clean up their toys (called continuous reinforcement), they’ll get too accustomed to this reward system. In the event that parents don’t give them candy once or twice, they’ll stop cleaning up the toys because they don’t think they’ll get candy anymore. Thus, this learned behavior (cleaning up) is rapidly extinguished. In contrast, reinforcement can be applied using a variable ratio in which the reward is given only at random intervals. Think of persons who have learned to enjoy gambling because it can be profitable; however, the slot machine they like to play rarely gives them money. The element of surprise and hope that they’ll get that big monetary award leads them to continue playing, even if they don’t win for a while; this response is slowly extinguished.

Another principle of learning is habituation. This refers to the observation that in some cases, repeated stimulation can eventually be “ignored.” For example, a car alarm outside may at first be overwhelmingly distracting and make it impossible to study. After a while, however, it may be possible to ignore the noise and continue studying. Sensitization is the opposite phenomenon, in which repeated stimulation leads to a stronger and stronger response. For example, a woman who has been abused by her husband might startle every time her husband raises his hand, even if it’s in a nonthreatening way.

Freudian Theory

Freud’s structural model explains people’s impulses and the actions they take. The id is the part of a person’s personality that drives what you want to do; it consists of hedonistic, impulsive urges such as seeking food and sex. In contrast, the superego is like the white angel that sits on your other shoulder, opposite the devilish id; it contains one’s morals and what you should do. The ego is the mediator between the two, the source of a person’s balance that determines the difference between right and wrong and what you want to do and what you should do.

According to Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, the ego has ways to cope with life’s stressors unconsciously. Some of these ego defenses are mature and more sophisticated, whereas others are immature and more primitive. For the USMLE, it is important to recognize examples of each of these ego defenses.

Immature Ego Defenses

Acting out: Feelings of distress are expressed in unacceptable ways, such as temper tantrums or taking drugs. Patients who act out aren’t able to channel their feelings in productive ways.

Acting out: Feelings of distress are expressed in unacceptable ways, such as temper tantrums or taking drugs. Patients who act out aren’t able to channel their feelings in productive ways.

Denial: A commonly used defense mechanism; patients pretend that something isn’t real and ignore its existence and significance. They do not want to deal with the consequences of this reality. For example, an alcoholic may deny that she or he has a problem with drinking.

Denial: A commonly used defense mechanism; patients pretend that something isn’t real and ignore its existence and significance. They do not want to deal with the consequences of this reality. For example, an alcoholic may deny that she or he has a problem with drinking.

Idealization: Unconsciously choosing to notice only the positive qualities of a person, perhaps even inflating those qualities to untrue degrees. A woman may idealize her abusive husband, believing that he is caring, generous, smart, and devoted; she ignores his negative qualities and the harm he causes her to suffer.

Idealization: Unconsciously choosing to notice only the positive qualities of a person, perhaps even inflating those qualities to untrue degrees. A woman may idealize her abusive husband, believing that he is caring, generous, smart, and devoted; she ignores his negative qualities and the harm he causes her to suffer.

Passive aggression: Another unproductive way of dealing with feelings. A patient may express their antagonistic feelings in indirect ways, such as procrastinating on tasks that they have been asked to do. A patient in conflict with the physician may repeatedly arrive late to appointments rather than directly addressing the underlying issue. This is something that is done consciously (unlike acting out): “I don’t like you, so I’m not going to do what you say.”

Passive aggression: Another unproductive way of dealing with feelings. A patient may express their antagonistic feelings in indirect ways, such as procrastinating on tasks that they have been asked to do. A patient in conflict with the physician may repeatedly arrive late to appointments rather than directly addressing the underlying issue. This is something that is done consciously (unlike acting out): “I don’t like you, so I’m not going to do what you say.”

Projection: Patients may have unpleasant feelings or impulses that they don’t like and thus cause them anxiety. To relieve this anxiety, they give these feelings to another person. A man who has racist feelings may feel guilt and discomfort about them, and so he subconsciously projects these feelings onto his neighbor and accuses his neighbor of racist behavior.

Projection: Patients may have unpleasant feelings or impulses that they don’t like and thus cause them anxiety. To relieve this anxiety, they give these feelings to another person. A man who has racist feelings may feel guilt and discomfort about them, and so he subconsciously projects these feelings onto his neighbor and accuses his neighbor of racist behavior.

Splitting: Simply put, this is the idea that everything is black or white and there are no shades of gray. For example, a woman hates or loves her acquaintances, and she believes that people are always good or always bad. Seeing people in this fashion can contribute to chaotic relationships because she may absolutely love and worship her partner when he brings her flowers once, but she may quickly flip to hating his evil guts when he forgets to call her to say good night. This immature ego defense is common in people with borderline personality disorder (see later).

Splitting: Simply put, this is the idea that everything is black or white and there are no shades of gray. For example, a woman hates or loves her acquaintances, and she believes that people are always good or always bad. Seeing people in this fashion can contribute to chaotic relationships because she may absolutely love and worship her partner when he brings her flowers once, but she may quickly flip to hating his evil guts when he forgets to call her to say good night. This immature ego defense is common in people with borderline personality disorder (see later).

Neurotic Ego Defenses

Displacement: Patients shift their undesirable feelings or impulses to a safer, less threatening person. A mother may be angry with her husband but afraid to confront him, so she yells at her young son.

Displacement: Patients shift their undesirable feelings or impulses to a safer, less threatening person. A mother may be angry with her husband but afraid to confront him, so she yells at her young son.

Dissociation: May be a reaction to a stressful or traumatic event. The patient tries to separate herself (dissociate) herself from the trauma and emotion. She may even change her personality temporarily to separate herself from the reality that she is a woman who was just attacked.

Dissociation: May be a reaction to a stressful or traumatic event. The patient tries to separate herself (dissociate) herself from the trauma and emotion. She may even change her personality temporarily to separate herself from the reality that she is a woman who was just attacked.

Identification: Unconsciously modeling one’s behaviors on someone else, although this may be good or bad. A child may grow up to be generous and warm like her mother. A teen who is physically abused by his stepfather may become physically aggressive toward his young brother.

Identification: Unconsciously modeling one’s behaviors on someone else, although this may be good or bad. A child may grow up to be generous and warm like her mother. A teen who is physically abused by his stepfather may become physically aggressive toward his young brother.

Intellectualization: When faced with a stressful or traumatic event, some patients may focus on the details in an intellectual fashion so that they do not dwell on the difficult emotions. For example, after a man’s father passes away, when asked how he is doing, he discusses the medical aspects of how his father passed away instead of discussing his emotions.

Intellectualization: When faced with a stressful or traumatic event, some patients may focus on the details in an intellectual fashion so that they do not dwell on the difficult emotions. For example, after a man’s father passes away, when asked how he is doing, he discusses the medical aspects of how his father passed away instead of discussing his emotions.

Isolation of affect: Like patients who dissociate, patients who use isolation of affect try to separate themselves from a traumatic event. A soldier may describe the death of his friend from a grenade explosion without emotion; he tries to remove his feelings from the situation. He doesn’t change his personality.

Isolation of affect: Like patients who dissociate, patients who use isolation of affect try to separate themselves from a traumatic event. A soldier may describe the death of his friend from a grenade explosion without emotion; he tries to remove his feelings from the situation. He doesn’t change his personality.

Rationalization: Also known as making excuses, rationalization is done when a person doesn’t want to confront their true motives or the reason for why something occurred. For example, a man who doesn’t want to admit he has romantic feelings for a woman may rationalize that he drove an hour out of his way to pick her up from the airport simply because that’s what any nice person would do. Or, a woman who fails an exam may rationalize that she doesn’t even care about the class, so it doesn’t matter.

Rationalization: Also known as making excuses, rationalization is done when a person doesn’t want to confront their true motives or the reason for why something occurred. For example, a man who doesn’t want to admit he has romantic feelings for a woman may rationalize that he drove an hour out of his way to pick her up from the airport simply because that’s what any nice person would do. Or, a woman who fails an exam may rationalize that she doesn’t even care about the class, so it doesn’t matter.

Reaction formation: When a patient has uncomfortable, undesirable feelings or impulses, they may deal with them by actually converting them into the opposite emotion. For example, a woman who falls in love with a close male friend but is afraid to risk initiating a romantic relationship may begin to treat him cruelly. This is done unconsciously.

Reaction formation: When a patient has uncomfortable, undesirable feelings or impulses, they may deal with them by actually converting them into the opposite emotion. For example, a woman who falls in love with a close male friend but is afraid to risk initiating a romantic relationship may begin to treat him cruelly. This is done unconsciously.

Regression: These patients deal with stress by reverting back to childlike ways, such as a woman with cancer wanting to cry and be held by her mother.

Regression: These patients deal with stress by reverting back to childlike ways, such as a woman with cancer wanting to cry and be held by her mother.

Repression: Unconsciously pushing a painful or stressful feeling or idea into the subconscious. This is different from denial, in which a patient is purposefully avoiding reality. To an outsider who tries to ask the patient about the feeling or event, it will seem like the patient had a memory lapse.

Repression: Unconsciously pushing a painful or stressful feeling or idea into the subconscious. This is different from denial, in which a patient is purposefully avoiding reality. To an outsider who tries to ask the patient about the feeling or event, it will seem like the patient had a memory lapse.

Undoing: A person who feels guilty about something may deal with it by performing actions that partially undo what they did. For example, a man has an affair with another woman and then buys his wife flowers on the way home. He is trying psychologically to cancel out one action with the other.

Undoing: A person who feels guilty about something may deal with it by performing actions that partially undo what they did. For example, a man has an affair with another woman and then buys his wife flowers on the way home. He is trying psychologically to cancel out one action with the other.

Mature Ego Defenses

Sublimation: This is a productive way of channeling an unpleasant or undesirable feeling into an acceptable action. For example, a man who has a bad temper and wants to physically hurt people who wrong him decides to become a judge so that he can punish evildoers via the law.

Sublimation: This is a productive way of channeling an unpleasant or undesirable feeling into an acceptable action. For example, a man who has a bad temper and wants to physically hurt people who wrong him decides to become a judge so that he can punish evildoers via the law.

Altruism: Giving selflessly to others to bring personal satisfaction. A man who feels terrible about hitting his ex-wife volunteers at a women’s shelter. Or, a woman whose husband recently died of cancer sets up a charity that benefits cancer research. These people are trying to resolve their own stress or anxiety by helping others.

Altruism: Giving selflessly to others to bring personal satisfaction. A man who feels terrible about hitting his ex-wife volunteers at a women’s shelter. Or, a woman whose husband recently died of cancer sets up a charity that benefits cancer research. These people are trying to resolve their own stress or anxiety by helping others.

Suppression: Consciously pushing a painful or stressful thought into the back of one’s mind with the intent of addressing it later (which makes it different from repression). For example, a woman whose husband just passed away suddenly puts her grief aside so that she can logically focus on funeral arrangements and making sure the finances are in order. She will deal with the emotions later.

Suppression: Consciously pushing a painful or stressful thought into the back of one’s mind with the intent of addressing it later (which makes it different from repression). For example, a woman whose husband just passed away suddenly puts her grief aside so that she can logically focus on funeral arrangements and making sure the finances are in order. She will deal with the emotions later.

Humor: Another mature defense, humor is just what it sounds like—breaking tension by joking about the stress of a situation. For example, a man who is nervous about his first date with a woman may make jokes to his friends that express his distress, but in a comical way.

Humor: Another mature defense, humor is just what it sounds like—breaking tension by joking about the stress of a situation. For example, a man who is nervous about his first date with a woman may make jokes to his friends that express his distress, but in a comical way.

The USMLE may ask you to recall which ego defenses are mature. They can be remembered by the mnemonic SASH: mature women wear a SASH.

Miscellaneous Concepts in Psychology

Transference is an important concept to recognize for the USMLE and for your career as a physician. It refers to a phenomenon in which a patient redirects feelings about an important person in life onto the clinician. For example, a patient may unconsciously associate his therapist with his neglectful mother. If the therapist then inadvertently glances at the clock on the wall during a session, it might rekindle surprisingly strong feelings of neglect from an otherwise benign action.

Countertransference is the opposite. The patient may remind the physician of someone significant, and this elicits feelings that change how the physician treats the patient. For example, a young patient may remind a physician of her daughter, so she may find herself encouraging the patient to do better in school or saying something critical when the patient mentions her active sex life. Because this can bias how physicians treat their patients, in mental health and other situations, countertransference is quite significant.

PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) lays out specific and technical criteria for the diagnosis of mental disorders. In general, however, you will only need to have the general picture of each disorder to answer questions correctly on the USMLE Step 1. A few exceptions will be noted.

Psychiatric Disorders of Children

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Children with this disorder are frequently described as being unable to sit still in class and often speak out of turn. They have great difficulty focusing on tasks such as homework assignments. Of note, these traits must be present in more than one setting, such as at home and at school. These children have normal intelligence. Unlike children with conduct disorder, children with ADHD do not characteristically exhibit criminal behavior. Unlike children with oppositional defiant disorder, they fail to follow through with instructions for homework assignments or interrupt conversations not because they are being defiant, but rather because they are forgetful or unable to control their energy.

Tip. These children may stare off into space and appear to ignore others who are speaking to them, so ADHD can be confused with absence seizures. A child with ADHD will have additional symptoms, as described, whereas a child with absence seizures may be described as blinking quickly during the staring spells and will not have other symptoms of ADHD.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

These children are defiant and naughty; they do not like to obey authority figures such as parents or teachers. They may get into arguments with adults and lose their temper, but they do not exhibit criminal behavior or overt acts of cruelty, like those with conduct disorder. They may be described as having normal relationships with their peers.

Conduct Disorder

These children repeatedly exhibit cruel or criminal behavior such as harming animals or destroying property. They are, by definition, younger than 18 years of age. (After age 18, they are diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder.)

Tourette Syndrome

Characterized by involuntary tics, usually motor (such as blinking or lip-licking), and including at least one vocal tic (such as throat clearing, or grunting). Unlike sitcoms would have you believe, patients rarely spew out profanities uncontrollably (called coprolalia). Some children exhibit echolalia in which they repeat words. These tics may be temporarily suppressible and are often compared with the need to sneeze. Although these children do not necessarily have other symptoms of mental illness, Tourette syndrome is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (think: they can’t control their grunting, and they also can’t control their need to wash their hands).

Separation Anxiety Disorder

May manifest in elementary school-age children who are extremely afraid to leave their caregivers. They may pretend to have tummy aches to stay home and avoid leaving their parents.

Pervasive Developmental Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorders

A new diagnosis in the DSM-V, this is a spectrum of disorders characterized by markedly impaired social function. These individuals have difficulties making friends and relating to others. Their speech is also abnormal, ranging from repetition of words and phrases to complete lack of speech. (Don’t confuse this with echolalia in Tourette syndrome; children with Tourette syndrome typically have normal friendships and language capabilities, although they may be shy and embarrassed.) Children with autism also have ritualistic behavior, such as habitually lining up cars.

These are other disorders with no good medical treatment. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can help treat certain behaviors, as can atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone; these medications will be discussed later in this chapter.

Asperger Disorder

On the less severe end of the spectrum of autistic disorders. In the DSM-5, Asperger Disorder is no longer a subdiagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. However, many patients may still use this term, and it is unclear when the USMLE will make this change. These children have normal intelligence and verbal capabilities and may be successful academically. However, they have trouble with social skills and tend to fixate on particular interests, such as displaying an obsession with airplanes.

Rett Syndrome

The characteristic exam finding is a girl who wrings her hands. These girls initially develop normally, but later lose skills they had acquired, such as loss of ability to speak or crawl. (In contrast, children with autism or Asperger disorder never have normal periods of development). Unlike children with Asperger disorder, children with Rett syndrome become mentally retarded. Although this disorder is X-linked, affected males die in utero, so the only living patients with this syndrome are female. Rett syndrome is no longer a diagnosis in DSM-5, as it is a genetic disorder that is separate from autism. However, some girls with Rett syndrome may also have autism–the two entities do have an association–so the two are not mutually exclusive.

Childhood Disintegrative Disorder

Similar to Rett syndrome in that there is initially a period of normal development, but these children then lose many of their acquired skills, from language to motor skills to bowel and bladder control. This disorder is more common in boys and is not characterized by stereotyped hand wringing, unlike Rett syndrome.

Delirium Versus Dementia

These two disorders are frequently difficult to tell apart in clinical practice, although there are key points that differentiate the two.

Patients who are delirious typically have an underlying medical cause for this acute change in mental status. They may be hallucinating and are not alert and attentive to the world around them; their level of consciousness waxes and wanes – they seem out of it. Older patients are particularly prone to delirium, particularly those who have recently undergone surgery, are in a hospital (or other unfamiliar setting), or are taking anticholinergic medications. Think of an old lady who is in a hospital recovering from hip replacement surgery who was previously pleasant and able to carry on conversations normally; one day, however, she starts to drift in and out of consciousness, speak somewhat incoherently to her deceased husband, and apparently does not hear hospital staff who attempt to ask her what is wrong. Delirium is reversible if the underlying cause is treated.

Patients with dementia are also typically older, although their deficits decline gradually rather than exhibiting a waxing and waning course as in delirium. In the early stages, they are alert and will interact relatively normally with those around them, although they gradually lose their memory and may eventually forget certain words (aphasia) and the ability to use certain objects, such as turning on a faucet (apraxia). Eventually, they exhibit personality changes and may become more withdrawn or more aggressive. Think of an older man who started to forget where he put his keys 6 months ago, started to forget to pay his bills 3 months ago, and yesterday took 2 hours to get home from the grocery store because he got lost. Dementia is not reversible, with few exceptions—notably normal pressure hydrocephalus and vitamin B12 deficiency.

Specific causes of dementia and medications that help slow cognitive decline are discussed in Chapter 13.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia can manifest in many different ways and is categorized by five characteristic symptoms, two of which need to be present to diagnose the condition. Only one symptom is necessary if a pathognomonic symptom is present—presence of a bizarre delusion or auditory hallucination consisting of a running commentary, or of two voices conversing. To make the diagnosis, these symptoms have to be present for more than 6 months; if not, the appropriate diagnosis may be brief psychotic disorder (< 1 month) or schizophreniform disorder (1 to 6 months).

Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs. Think of a man who believes that the government is spying on him and cannot be convinced otherwise, despite evidence to the contrary.

Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs. Think of a man who believes that the government is spying on him and cannot be convinced otherwise, despite evidence to the contrary.

Hallucinations: Sensing something that is not actually present. Auditory hallucinations (e.g., hearing voices) are the most common in schizophrenia. If a patient is having visual hallucinations, consider delirium or other organic causes, such as LSD intoxication. Tactile hallucinations are more common in patients who are withdrawing from alcohol or are abusers of cocaine. Formications, the sensation of ants crawling on one’s skin, is the most common tactile hallucination. Olfactory hallucinations may be present in temporal lobe epilepsy.

Hallucinations: Sensing something that is not actually present. Auditory hallucinations (e.g., hearing voices) are the most common in schizophrenia. If a patient is having visual hallucinations, consider delirium or other organic causes, such as LSD intoxication. Tactile hallucinations are more common in patients who are withdrawing from alcohol or are abusers of cocaine. Formications, the sensation of ants crawling on one’s skin, is the most common tactile hallucination. Olfactory hallucinations may be present in temporal lobe epilepsy.

Disorganized speech: Characterized by loose associations (e.g., jumping from one thought to another).

Disorganized speech: Characterized by loose associations (e.g., jumping from one thought to another).

Disorganized or catatonic behavior: A person with disorganized behavior may dress oddly or inappropriately (a purple raincoat with three hats in the summer) or may neglect hygiene (brushing hair or bathing). A person with catatonic behavior is unresponsive and generally unmoving, much like a statue. However, he or she may instead have peculiar movements, such as prolonged grimacing or repeating words that others say (echolalia).

Disorganized or catatonic behavior: A person with disorganized behavior may dress oddly or inappropriately (a purple raincoat with three hats in the summer) or may neglect hygiene (brushing hair or bathing). A person with catatonic behavior is unresponsive and generally unmoving, much like a statue. However, he or she may instead have peculiar movements, such as prolonged grimacing or repeating words that others say (echolalia).

Negative symptoms: Include flat affect, lack of motivation, lack of speech, and social withdrawal. To understand why they are called negative, consider that the previous four symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior) are positive; they involve the addition of abnormal characteristics, such as hearing voices that are not truly there. Negative symptoms, in contrast, involve the absence of characteristics that normal people have (such as speech and a wide range of emotion). The distinction between positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia is clinically important because certain medications are more effective against one or the other type of symptoms.

Negative symptoms: Include flat affect, lack of motivation, lack of speech, and social withdrawal. To understand why they are called negative, consider that the previous four symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior) are positive; they involve the addition of abnormal characteristics, such as hearing voices that are not truly there. Negative symptoms, in contrast, involve the absence of characteristics that normal people have (such as speech and a wide range of emotion). The distinction between positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia is clinically important because certain medications are more effective against one or the other type of symptoms.

Interestingly, schizophrenia has a similar prevalence across many socioeconomic, cultural, and ethnic groups (≈ 1.5%). Unlike most psychological disorders, schizophrenia is evenly divided between men and women, although men tend to present earlier (in their late teens), whereas women tend to present later (in their late 20s).

Neurobiologic Mechanism

Schizophrenia is thought to result primarily from an excess of dopaminergic signaling in the mesolimbic (connecting the midbrain to the limbic system) and mesocortical (connecting the midbrain to the frontal cortex) pathways of the brain.

Treatment

The mainstay of medical treatment is with antipsychotics. Their efficacy relates to the degree at which they block dopamine signaling at D2 receptors. Some side effects of antipsychotics can be explained by dopamine blockade in other pathways of the brain.

The nigrostriatal pathway connects the substantia nigra to the striatum and is important for control of movement. In fact, patients with Parkinson’s disease have profound reductions in dopamine signaling in this pathway; thus, antipsychotics can actually cause abnormalities of movement. The nigrostriatal pathway is part of the extrapyramidal system, so called because this group of motor regulatory pathways does not pass through the pyramids of the medulla. The symptoms that antipsychotics cause are referred to as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and include acute dystonic reactions (muscle spasms, especially those of the neck [torticollis] and eyes [oculogyric crisis]), akathisia (restless legs), pseudoparkinsonism (bradykinesia, resting tremor, and other symptoms commonly seen in Parkinson’s disease), and tardive dyskinesia (involuntary movements such as tongue darting out of the corner of the mouth or lip smacking). Treatment of acute dystonic reactions is with anticholinergics, such as diphenhydramine or benztropine.

The tuberoinfundibular pathway connects the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to regulate pituitary hormone secretion. Particularly important is the control of prolactin, a hormone that can cause symptoms such as galactorrhea (milky discharge from the nipples), gynecomastia (breast enlargement), and loss of libido. Normally, dopamine signaling inhibits prolactin secretion. When dopamine signaling is blocked, as with antipsychotics, this inhibition is taken away, and hyperprolactinemia results.

Other side effects of antipsychotics relate to other receptor types that are inadvertently also blocked.

Finally, there are some side effects of antipsychotics that are not attributable to a single mechanism, as far as we know.

QT prolongation: This dangerous cardiac side effect can lead to torsades de pointes.

QT prolongation: This dangerous cardiac side effect can lead to torsades de pointes.

Seizures: Many antipsychotics lower the seizure threshold.

Seizures: Many antipsychotics lower the seizure threshold.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS): This life-threatening syndrome is characterized by fever (hyperthermia), lead pipe muscle rigidity, autonomic instability (tachycardia, sweating), tremor, leukocytosis, and elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level. It is treated by immediately stopping the offending drug and cooling the patient. As the hyperthermia associated with NMS is related to blockade of the D2 receptor in the hypothalamus and subsequent increase in the body’s temperature set point, bromocriptine (a dopamine agonist) may be used in treatment. Dantrolene inhibits calcium release through ryanodine receptor channels and can also be useful for relaxing muscles.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS): This life-threatening syndrome is characterized by fever (hyperthermia), lead pipe muscle rigidity, autonomic instability (tachycardia, sweating), tremor, leukocytosis, and elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level. It is treated by immediately stopping the offending drug and cooling the patient. As the hyperthermia associated with NMS is related to blockade of the D2 receptor in the hypothalamus and subsequent increase in the body’s temperature set point, bromocriptine (a dopamine agonist) may be used in treatment. Dantrolene inhibits calcium release through ryanodine receptor channels and can also be useful for relaxing muscles.

First-Generation (Typical) Antipsychotics

This class of medications is relatively successful at reducing positive symptoms, but they do not work well in treating negative symptoms (Table 14-1). The information given earlier about mechanism of action and side effects applies to typical antipsychotics.

Table 14-1

First-Generation (Typical) Antipsychotics (Neuroleptics)

| Medication | Potency | Special Notes |

| Chlorpromazine | Low | This low-potency drug is usually associated with sleepiness and orthostatic hypotension. With long-term use, patients may note gray-blue skin pigmentation. |

| Thioridazine | Low | Known for causing prolonged QT. It can accumulate in the eyes and cause retinitis pigmentosa, which may lead to blindness. |

| Haloperidol | High | Known in hospitals as vitamin H, haloperidol is commonly used intramuscularly when a patient becomes acutely aggressive or delirious. The incidence of EPS is high. |

| Trifluoperazine, perphenazine, fluphenazine | High | — |

Of note, the drugs that have lower potency (more drug required to achieve therapeutic levels of D2 receptor blockade) are less likely to cause EPS but are more likely to cause autonomic side effects such as drowsiness and hypotension because the higher doses cause blocking of the H1 (drowsiness) and α1 (vasodilation, hypotension) receptors described earlier. Conversely, the drugs that have higher potency are more likely to cause EPS but are less likely to cause autonomic side effects.

Think of it this way. A higher potency drug is very good at blocking D2 receptors, but D2 receptor blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway is what causes EPS. Thus, high-potency drugs are prone to causing EPS. The upside is that high potency drugs can be administered in lower doses, and therefore there is a lower chance of inadvertently blocking H1, α1, and muscarinic receptors.

Second-Generation (Atypical) Antipsychotics

Atypical antipsychotics actually block serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptor, α1, and H1 receptors in addition to D2 receptors (Table 14-2). They are somewhat less effective than typical antipsychotics at treating positive symptoms, but they treat negative symptoms well. They are less likely to cause EPS and anticholinergic side effects than their typical counterparts. However, they do cause significant H1 blockade and are thus associated with weight gain and the metabolic syndrome, which is of great concern for many patients.

Table 14-2

Second-Generation (Atypical) Antipsychotics (Neuroleptics)

| Medication | Special Notes |

| Clozapine | May cause agranulocytosis; this leukopenia can be fatal, so the CBC must be monitored. It also lowers the seizure threshold. Because of these concerns, clozapine is never considered as a first-line medication. |

| Olanzapine | Strongly associated with weight gain and insulin resistance. Think of an obese person looking very round, like the letter “O” in “olanzapine.” |

| Risperidone | Particularly associated with hyperprolactinemia |

| Aripiprazole | In addition to the listed mechanisms of action, aripiprazole is also a partial agonist at dopamine and 5-HT1A receptors. |

| Quetiapine | Makes people very sleepy. It can even be used as a sedative for patients who have trouble sleeping. Think of sleeping during “quiet time,” which sounds similar to “quetiapine.” It may also be associated with cataracts, so patients need their eyes checked regularly. |

| Ziprasidone | Known for QT prolongation; less weight gain than other atypical antipsychotics |

Unfortunately, despite medical treatment and cognitive-behavioral interventions, most patients with schizophrenia are affected for their lifetime, with many of them experiencing significant impairment; they are often unable to keep jobs or maintain relationships.

Similar Disorders

The following disorders are characterized by symptoms similar to the symptoms of schizophrenia, but there are key differences among these diagnoses. Patients with schizophrenia-like symptoms can all be described as psychotic because psychosis is a description of this constellation of symptoms but is not a formal diagnosis.

Brief psychotic disorder is similar in the type of symptoms to schizophrenia, but the time course is different. In brief psychotic disorder, the symptoms have been present for less than 1 month and are usually precipitated by a major stressor, such as being expelled from college.

Schizophreniform disorder also is like schizophrenia. Its duration is longer than a brief psychotic disorder but shorter than schizophrenia. The symptoms have been present for 1 to 6 months. Thus, it is critical that you note the time course in the question stem, because this will affect the diagnosis of a patient with psychotic symptoms.

Schizoaffective disorder is similar to schizophrenia plus mood symptoms such as depressive symptoms or manic symptoms (see later). The schizophrenic symptoms are dominant over the mood symptoms—they develop first and remit last.

Delusional disorder may be difficult to distinguish from schizophrenia. Patients with delusional disorder have delusions, as the name suggests, but they are not bizarre. Such delusions are actually plausible, but unwavering. For example, nothing you say can make the patient shake his belief that members of the CIA are following him every time he leaves his house. Contrast this with a schizophrenic, who may delude that aliens have implanted a device in his brain that controls his thoughts and actions; this delusion is bizarre and certainly not plausible. Unlike patients with schizophrenia, those with delusional disorder lack disorganized speech and behavior, are not severely impaired, and may lead otherwise normal lives, with stable jobs and relationships. You may encounter a question regarding a man with delusional disorder whose wife also begins to develop delusions; this is a shared psychotic disorder (or folie à deux). His wife has a reasonable chance of recovery if separated from him because he unwittingly induced the delusions in her.

Depression

To meet the criteria of a major depressive episode, a person must have at least five of the SIG E CAPS criteria for at least 2 weeks. Also, one of the symptoms must be depressed mood or anhedonia (loss of interest in pleasurable activities):

Interest—loss of interest in pleasurable activities (anhedonia)

Interest—loss of interest in pleasurable activities (anhedonia)

Guilt—feelings of guilt or worthlessness

Guilt—feelings of guilt or worthlessness

Energy—fatigue or loss of energy

Energy—fatigue or loss of energy

Concentration—diminished ability to concentrate or focus

Concentration—diminished ability to concentrate or focus

Appetite—increase or decrease in appetite or weight

Appetite—increase or decrease in appetite or weight

The proportion of people who experience a major depressive episode at least once in their lifetime is significant, 5% to 12% for men and 10% to 25% for women. Some patients go on to have major depressive disorder, with recurrent major depressive episodes. An example is a 58-year-old woman who typically has had a good life as a schoolteacher and wife, but a few times each year, she feels so sad that she can’t get out of bed, tells herself she’s worthless, and wonders if life is worth living anymore.

Neurobiologic Mechanism

The neurotransmitter abnormalities in depression are less clear than those in schizophrenia. It appears that patients with depression have decreased levels of serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine, and dopamine, because drugs that increase signaling in these pathways tend to improve patients’ symptoms.

Treatment

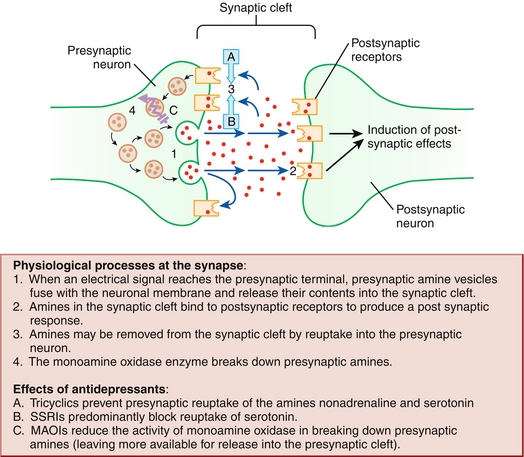

See Figure 14-1 for an explanation of the mechanism of action of the major classes of antidepressants.

Figure 14-1 Mechanism of action of the major classes of antidepressants. (From Bennett PM, Brown MJ. Clinical Pharmacology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.)

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are an older class of medications that work by blocking reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, thereby prolonging their action in the synapse. These medications are rarely used for depression now because of their dangerous tendency to prolong the QRS, QT, and PR intervals and cause cardiac arrhythmias; they are lethal in overdose. TCAs also have anticholinergic side effects, including dry mouth, constipation, and urinary retention. As noted (“Delirium”), patients may also develop altered mental status because of anticholinergic effects. One of these side effects can be exploited for another medical use; imipramine is a TCA that is still used for children who suffer from bedwetting because of its tendency to cause urinary retention. Other TCAs such as amitriptyline and nortriptyline have found a role in treating neuropathic pain, such as what might be suffered by a long-time diabetic. The doses required for these latter scenarios are much lower than what was used to treat depression.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) inhibit monoamine oxidase, an enzyme that breaks down amine neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Therefore, higher levels of these neurotransmitters are available. The MAO enzyme is located within the neuron’s cytoplasm, unlike the reuptake inhibitors that are affected by TCAs. The use of MAOIs for depression is limited by two major side effects. The first requires an understanding of tyramine, a naturally occurring compound found in foods such as wine, aged cheese, and smoked meats. Tyramine is a precursor in the biosynthesis of norepinephrine, a potent vasoconstrictor. Because MAOIs increase the availability of norepinephrine, eating tyramine-rich foods places patients at risk of hypertensive crisis. If patients are on other medications that increase the availability of serotonin, patients on MAOIs are at risk for serotonin syndrome (see later). However, it is notable that MAOIs are particularly effective for atypical depression, which is characterized by hypersomnia, hyperphagia, and leaden paralysis.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly used today because they are much safer than the previous two classes of antidepressants. As their name suggests, they inhibit the reuptake of serotonin into the presynaptic neuron, allowing for longer duration of serotonin action in the synapse. Common side effects include weight gain, gastrointestinal (GI) upset, and sexual dysfunction, which limits their use in many patients. Specific drugs that you may encounter are fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and citalopram.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are newer medications that inhibit the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. Like SSRIs, they are more widely used today because they are safer than MAOIs and TCAs in overdose. Their side effects are also similar to SSRIs; although some patients do experience decreased sexual drive and anorgasmia, some patients actually have an increased sexual drive while taking SNRIs. Interestingly, like TCAs, they can be used for neuropathic pain, possibly because they both increase norepinephrine signaling. The increase in norepinephrine levels can lead to hypertension, tachycardia, and other stimulant effects. Commonly used SNRIs include venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran, and sibutramine.

Bupropion is a unique newer antidepressant that has stimulant qualities because of its norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibition. Two benefits of bupropion are that it does not cause weight gain (it actually can cause weight loss) and it does not cause sexual dysfunction (it can actually increase libido). It is important to note that bupropion decreases the seizure threshold, so patients who are prone to seizures should not take this medication. These patients include those with epilepsy, brain tumors, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (see later), and withdrawal from alcohol or benzodiazepines. Bupropion can also be used as a smoking cessation aid.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may sound barbaric, but it is a safe and effective therapy used for depression that is refractory to antidepressant medications. It can also be used if a patient is in extreme distress and/or suicidal because it tends to work more quickly than medication, which takes weeks to have noticeable effect. After the patient is sedated and paralyzed, electricity is passed through the brain to cause a seizure. The main side effect of ECT is retrograde amnesia.

Serotonin Syndrome

Of note, TCAs, MAOIs, SSRIs, and SNRIs all increase synaptic levels of serotonin. When patients take multiple serotonergic medications, they are at risk for serotonin syndrome, a condition marked by sweating, diarrhea, fever, autonomic instability, and seizures. If the exact medications are not known, this can be confused with NMS. On Step 1, a patient with NMS will have lead pipe rigidity and elevated CPK, whereas a patient with serotonin syndrome will not.

Dysthymia

Dysthymia can be thought of as a milder form of depression that is more chronic (at least 2 years). Patients with dysthymic disorder have depressed mood for most of the time on most days, and they also may experience sleep disturbances and other depressive symptoms, but they never meet the criteria for a major depressive episode. These patients usually do not need hospitalization because they typically can care for themselves and do not attempt suicide. Think of an older man who has felt “down” for many years, doesn’t take joy in anything, and is always tired. A patient with dysthymia who does have an episode of major depression is subsequently described as having double depression.

Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar I

A woman notices that her husband has been acting strangely for the past 2 weeks. He has barely been sleeping, only an hour a night, because he says he has to get back to his “big research project.” He eagerly tells everyone within shouting distance about his exciting plan to achieve world peace and how he is going to meet with one of the President’s advisors to tell him all about it; however, it is hard to understand him because he talks so quickly and jumps from one idea to another. He has also drained their savings by buying an expensive new suit and sports car. This is a classic example of a patient with bipolar I disorder.

Patients with bipolar I disorder have had at least one manic episode (lasting at least 1 week) that includes at least three of the DIG FAST criteria:

Flight of ideas or racing thoughts

Flight of ideas or racing thoughts

Activity, Agitation, such as putting in significantly more work into projects or increase in sexual activity

Activity, Agitation, such as putting in significantly more work into projects or increase in sexual activity

Speech—pressured, rapid speech

Speech—pressured, rapid speech

Thoughtlessness— engaging in pleasurable activities with negative consequences, such as gambling or shopping sprees

Thoughtlessness— engaging in pleasurable activities with negative consequences, such as gambling or shopping sprees

Note that a patient only needs to have a manic episode to be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, although most patients also cycle through periods of major depression.

Bipolar II

These patients may have stories similar to those with bipolar I disorder, but they have never had a manic episode. Instead, they have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode. A hypomanic episode only needs to last 4 days (unlike 7 days for a manic episode) and is less severe than a manic episode; these patients have DIG FAST symptoms but are not as severely impaired. Think of a college student who has been irritable for the past few days, speaks quickly with rapidly changing topics, and has been spending all the time working on a project for a robotics class, even foregoing sleep.

Treatment for Bipolar I and Bipolar II Disorders

Lithium helps stabilize mood and decreases the risk of a manic or depressive episode. Important side effects include its antidiuretic hormone (ADH) antagonist effects on the kidney (causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus) and its action on the thyroid gland (causing hypothyroidism). A known teratogen, it is associated with Ebstein anomaly in the infant, in which the opening of the tricuspid valve is displaced downward toward the apex of the right ventricle; this makes the right atrium too large and the right ventricle too small.

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are also useful for stabilizing mood. Valproic acid is one such medication. It is teratogenic, a folate antagonist associated with spina bifida, and also increases liver function test results. Carbamazepine is another AED that also increases liver function test results and carries a risk of agranulocytosis. (Do you recall which antipsychotic is also strongly associated with agranulocytosis? Answer—Clozapine.)

Electroconvulsive therapy can also be used for patients with bipolar disorder.

Anxiety Disorders

Panic Disorder

Patients with panic disorder have panic attacks and are constantly afraid of having another embarrassing panic attack. Panic attacks are characterized by sweating, palpitations, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, numbness or tingling, feeling like one is choking, and/or feeling like one is going to die.

Of note, panic attacks occur out of the blue and do not have a clear trigger. Some patients may even have agoraphobia, in which they avoid public places; they are afraid of having a panic attack in a place where they do not feel safe, so they stay secluded at home.

Neurobiologic Mechanism

Panic disorder is associated with increased norepinephrine signaling and decreased serotonin and GABA. In brief, this makes sense because of the autonomic symptoms that patients have (increased norepinephrine) and inability to relax (decreased GABA).

Treatment

Benzodiazepines: These drugs allosterically alter GABA receptors in the brain and promote GABA binding. Given the known neurotransmitter abnormalities, it should make sense that these GABA-ergic medications should help a patient relax during a panic attack. However, these medications are habit-forming and should not be used long-term.

Benzodiazepines: These drugs allosterically alter GABA receptors in the brain and promote GABA binding. Given the known neurotransmitter abnormalities, it should make sense that these GABA-ergic medications should help a patient relax during a panic attack. However, these medications are habit-forming and should not be used long-term.

SSRIs: Useful for long-term maintenance because of the lower baseline serotonin levels in patients with panic disorder. Recall that SSRIs are also a mainstay of treatment for depression.

SSRIs: Useful for long-term maintenance because of the lower baseline serotonin levels in patients with panic disorder. Recall that SSRIs are also a mainstay of treatment for depression.

Specific and Social Phobias

The term phobia is used to describe an exaggerated or irrational fear of an object or situation. Those with a phobia are so affected by this fear that it interferes with their social life, job, or other activities of daily living. For example, I become nervous around spiders and will avoid touching them at all costs, even going so far as to request that other people get rid of spiders for me. I avoid situations in which spiders may be present, such as a hike through the forest. If a spider is present, I am unable to pay attention to my work or enjoy being with friends because I am so anxious and worried that it will crawl over and attack me. I am certainly aware that this fear is excessive but am unable to feel otherwise.

Patients with social phobia have similar anxious reactions to people in general or specific situations, such as public speaking.

The distress I experience when confronted by spiders does not qualify for a panic attack as defined earlier, but some patients may experience actual panic attacks in reaction to their phobia. Such patients are not considered to have panic disorder. Although the distinction between panic disorder and a specific or social phobia may seem hazy, the key point is that panic disorder is characterized by unprovoked panic attacks, whereas patients with a specific or social phobia have symptoms of anxiety or panic specifically when confronted by their fear.

Treatment

Unlike for panic disorder, medications are not particularly effective for specific phobias. This disorder is best treated by systematic desensitization, in which the patient is gradually exposed to their fear while using hypnosis or another technique for relaxation.

In contrast, sufferers of social phobia do benefit from paroxetine, an SSRI. Beta blockers such as propranolol are also useful for social phobia to blunt the sympathetic response that causes a person’s heart to race.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Unlike those with panic disorder or aspecific or social phobia, patients with GAD are always anxious (as the name of the disorder suggests). They worry about multiple aspects of their daily lives in such a way that it can be debilitating. They even worry about nothing in particular. They may have trouble sleeping or concentrating, and they may be irritable and tense. These symptoms are chronic and must last for at least 6 months; many patients complain of “being anxious my whole life.” GAD is common, with a lifetime prevalence of about 4%.

Neurobiologic Mechanism

There is no one neurotransmitter implicated in GAD, although it appears that there is increased norepinephrine, decreased GABA, and decreased serotonin signaling. Also, functional MRI studies link GAD to abnormal processing in the amygdala, an area of the brain that has important roles in emotions and memory.

Treatment

SSRIs and SNRIs: Recall that depression and GAD are associated with decreased levels of serotonin.

SSRIs and SNRIs: Recall that depression and GAD are associated with decreased levels of serotonin.

Buspirone: A unique medication that is a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors. It is also a D2 antagonist, but it is not clear if this contributes to its anxiolytic effects. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have potential for tolerance or dependence. Also, it is not sedating and does not interact with alcohol.

Buspirone: A unique medication that is a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors. It is also a D2 antagonist, but it is not clear if this contributes to its anxiolytic effects. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have potential for tolerance or dependence. Also, it is not sedating and does not interact with alcohol.

Benzodiazepines: May be used for the treatment of GAD. However, as is the case with panic disorder, they are not ideal for monotherapy or for prolonged periods because of the risk of tolerance and dependence. Furthermore, because benzodiazepines are GABA-ergic depressants, there is a risk of respiratory depression and death when mixed with alcohol.

Benzodiazepines: May be used for the treatment of GAD. However, as is the case with panic disorder, they are not ideal for monotherapy or for prolonged periods because of the risk of tolerance and dependence. Furthermore, because benzodiazepines are GABA-ergic depressants, there is a risk of respiratory depression and death when mixed with alcohol.

The prognosis for GAD is not as poor as for other disorders such as schizophrenia; 50% of patients will fully recover.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Obsessions are recurrent thoughts that cause distress to the patient. Unlike hallucinations (e.g., what a schizophrenic might have), a patient with OCD is aware that the distressing obsession is “all in the head.” (The fact that patients with OCD are aware of their irrational thoughts and behavior is termed ego dystonic; they are not comfortable with these obsessions.) For example, someone might be frequently haunted by the thought that they might have forgotten to turn off the stove. Another patient may feel that doing any task, from folding clothes to cutting carrots, has to be done in an exact fashion or else it will not feel “right.” Other common obsessions relate to symmetry (of an arrangement of objects) or cleanliness (and the presence of germs).

Compulsions are compensatory actions that the patient does to relieve the anxiety caused by the obsession. Patients who worry about whether the stove is on or off may go to the kitchen to check it repeatedly; this urge may be so strong that it causes them to be late for work or get out of bed when trying to sleep. Patients who have less well-defined obsessions regarding daily tasks may count in their head while chopping carrots to make sure they finish on a “safe” number. Patients may spend significant time moving and rearranging objects so that their alignment is good or may wash their hands repeatedly to the point that their skin becomes raw. Clearly, patients with OCD are very distressed by their obsessions, and the resulting compulsions interfere with the flow of their daily lives.

Stress Disorders

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD develops in some patients after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic, or potentially life-threatening, event. Such events include rape, war, and motor vehicle accidents. For at least 1 month, they experience symptoms such as the following:

Hyperarousal—this state of increased alertness and tension can lead to trouble sleeping, jumpiness, or angry outbursts.

Hyperarousal—this state of increased alertness and tension can lead to trouble sleeping, jumpiness, or angry outbursts.

Intrusive thoughts—the patient has persistent dreams or flashbacks of the event.

Intrusive thoughts—the patient has persistent dreams or flashbacks of the event.

Numbness—patients may have limited emotions and affect, and they may feel detached from the world around them.

Numbness—patients may have limited emotions and affect, and they may feel detached from the world around them.

Avoidance—patients avoid anything that reminds them of the traumatic event, such as a war veteran avoiding fireworks shows, shooting ranges, or other locations that have loud, sudden noises.

Avoidance—patients avoid anything that reminds them of the traumatic event, such as a war veteran avoiding fireworks shows, shooting ranges, or other locations that have loud, sudden noises.

Acute Stress Disorder

Patients with acute stress disorder have similar reactions to a traumatic event as those with PTSD, but symptoms of acute stress disorder last less than 1 month. It is treated similarly to PTSD.

Adjustment Disorder

Adjustment disorder involves an excessive, maladaptive reaction to a stressful life event. Unlike PTSD, the life event need not be life-threatening; it may involve moving to a new school or divorcing one’s spouse. Although most people do have some sadness or anxiety in response to such situations, those with adjustment disorder have more severe reactions. For example, a teenager may develop symptoms of depression after leaving his childhood friends and moving to a new town; he loses his appetite, feels sad all the time, and even thinks of ending his own life. However, he was a happy young man before this event, and if he were to move back to his hometown, his symptoms would disappear. This is a key difference from major depressive disorder, in which there is no clear trigger that can be removed. This particular patient developed depressive symptoms, whereas others with adjustment disorder may develop anxiety or aggression.

Of note, normal grief after the death of a loved one does not constitute an adjustment disorder.

Malingering

A malingerer fakes a disorder for secondary gain (a goal that would benefit the patient). For example, an inmate may fake psychotic symptoms to be removed from jail. Or, the disorder may be physical; a man may fake or greatly exaggerate back pain to receive opiates from a physician. These patients avoid interaction with medical personnel as much as possible (they don’t want their cover blown!), and their symptoms resolve once their secondary gain has been achieved.

Factitious Disorder

Like malingering, patients with factitious disorder consciously fake symptoms, both physical and psychological. However, they do not have a secondary goal in mind (e.g., avoiding work); their primary aim is to be a sick patient and thus get attention and sympathy from medical providers. This can be difficult to diagnose and requires a high degree of suspicion and some detective work on the part of the physician. For example, for a patient who complains of terrible stomach pain, an examiner may stand near the patient and subtly bump into the patient or the bed while talking. This should elicit a grimace in a patient with truly severe abdominal pain, but patients with a factitious disorder may not react because they do not believe they are being examined. Another commonly tested example is a patient who secretly injects insulin to purposely induce hypoglycemia. The treating physician should measure levels of C-peptide to distinguish factitious disorder from organic causes (C-peptide is produced with endogenous insulin and will be low in a factitious disorder [exogenous insulin] but high with an organic cause [endogenous insulin]). Unfortunately, factitious disorder has a poor prognosis, and there is no good treatment.

Munchausen syndrome is the term used to describe a factitious disorder that is chronic (rather than a few isolated episodes). Think of a woman who complains of awful, chronic abdominal pain who has been to numerous doctors. On two occasions, her abdominal pain has even appeared to be acute on exam, and she has actually consented to and undergone two exploratory surgeries. She visits new doctors to continue to receive care. However, imaging, lab work, and the history and physical have all failed to reveal an organic reason for her pain. (On your test, the question stem will likely tell you that all testing has been negative, and you should infer that the disorder is being faked. In reality, although, don’t be too quick to blame the patient if you are unable to find an answer, because there are certainly actual diseases that elude explanation for quite some time.)

Munchausen syndrome by proxy or factitious disorder by proxy is almost always a case of a mother faking an illness in her child. For example, a mother may take her young son to a number of physicians, saying that he has joint pains, headaches, vomiting, and a rash. She may appear to have a lot of knowledge about medicine and may even work in a health care setting. In the hospital, she is always by her son’s side and demands near-constant attention and always wants more tests or procedures. Mysteriously, when she is not present, her son doesn’t seem to have any symptoms at all. Testing doesn’t support any of her claims or point to a diagnosis. When told that there is nothing more to be done and that it is time for discharge, the patient may suddenly get worse, and the mother may demand transfer to a “better” hospital. This is a very unfortunate situation and is a form of child abuse.

Somatoform Disorders

These patients have physical symptoms that have no identifiable explanation, like malingering and factitious disorder. However, the key difference is that patients with somatoform disorders are not consciously creating symptoms for primary or secondary gain. The reason for their symptoms and health care–seeking behavior is unconscious, and they are not creating their symptoms willfully.

Somatization disorder: These patients have multiple complaints that span several organ systems. Their symptoms must include pain (e.g., leg or neck pain), sexual (e.g., discomfort with intercourse), gastrointestinal (e.g., diarrhea or bloating), and neurologic symptoms (e.g., tingling in hands and feet). This tends to be a chronic disorder and, sadly, can be debilitating. The best way for the physician to handle a patient with somatization disorder is frequently scheduled visits with the primary care provider to help the patient feel nurtured and discuss any new concerns. Medication does not help. Excessive testing should be avoided.

Somatization disorder: These patients have multiple complaints that span several organ systems. Their symptoms must include pain (e.g., leg or neck pain), sexual (e.g., discomfort with intercourse), gastrointestinal (e.g., diarrhea or bloating), and neurologic symptoms (e.g., tingling in hands and feet). This tends to be a chronic disorder and, sadly, can be debilitating. The best way for the physician to handle a patient with somatization disorder is frequently scheduled visits with the primary care provider to help the patient feel nurtured and discuss any new concerns. Medication does not help. Excessive testing should be avoided.

Mnemonic: Somatization disorder has so many symptoms (pain, sexual, gastrointestinal, neurologic).

Conversion disorder: Characterized by a psychological trigger being converted into a neurologic symptom in the absence of an organic cause. These symptoms are often transient. A classic example includes a devoted son who, in a rage, raises his arm to strike his mother. Instead of striking her, his hand becomes “paralyzed.” Other examples include paresthesias, seizures, blindness, and the sensation of a lump in the throat (called “globus hystericus”). These patients tend to be young adults. In older patients, be vigilant for organic causes such as transient ischemic attacks. Patients may display la belle indifference, a surprising lack of concern for their severe symptom. Often the symptom will resolve and never return; the prognosis is much better than for other somatoform disorders.

Conversion disorder: Characterized by a psychological trigger being converted into a neurologic symptom in the absence of an organic cause. These symptoms are often transient. A classic example includes a devoted son who, in a rage, raises his arm to strike his mother. Instead of striking her, his hand becomes “paralyzed.” Other examples include paresthesias, seizures, blindness, and the sensation of a lump in the throat (called “globus hystericus”). These patients tend to be young adults. In older patients, be vigilant for organic causes such as transient ischemic attacks. Patients may display la belle indifference, a surprising lack of concern for their severe symptom. Often the symptom will resolve and never return; the prognosis is much better than for other somatoform disorders.

Hypochondriasis: The distinguishing feature of hypochondriasis is that patients are fearful that they have a disease and repeatedly seek health care and testing to prove that they have a disease. They can actually have symptoms, but they misinterpret them; for example, a man who has bloating after meals may fear that he has some type of gastrointestinal cancer and is not reassured by multiple negative tests. This can be distinguished from somatization disorder, in which there is a fixation on a multitude of symptoms and how they feel (not an underlying disease).

Hypochondriasis: The distinguishing feature of hypochondriasis is that patients are fearful that they have a disease and repeatedly seek health care and testing to prove that they have a disease. They can actually have symptoms, but they misinterpret them; for example, a man who has bloating after meals may fear that he has some type of gastrointestinal cancer and is not reassured by multiple negative tests. This can be distinguished from somatization disorder, in which there is a fixation on a multitude of symptoms and how they feel (not an underlying disease).

Body dysmorphic disorder: These unfortunate patients are obsessed with aspects of their appearance that they believe to be flawed, despite all evidence to the contrary. For example, a man feels strongly that his muscles are small and unattractive, and he frequently lifts weights and examines himself in the mirror to critique their appearance. He repeatedly asks his friends if his muscles look small, and although he is actually very muscular and his friends tell him so, he cannot believe them and continues to feel “puny.” Another example is a woman who hates how her nose looks. She refuses to look at herself in the mirror and won’t allow her friends to take pictures of her nose. Even after having plastic surgery on her nose twice, she still thinks it is ugly, although her friends see no problem with it. SSRIs can reduce symptoms in some of these patients.

Body dysmorphic disorder: These unfortunate patients are obsessed with aspects of their appearance that they believe to be flawed, despite all evidence to the contrary. For example, a man feels strongly that his muscles are small and unattractive, and he frequently lifts weights and examines himself in the mirror to critique their appearance. He repeatedly asks his friends if his muscles look small, and although he is actually very muscular and his friends tell him so, he cannot believe them and continues to feel “puny.” Another example is a woman who hates how her nose looks. She refuses to look at herself in the mirror and won’t allow her friends to take pictures of her nose. Even after having plastic surgery on her nose twice, she still thinks it is ugly, although her friends see no problem with it. SSRIs can reduce symptoms in some of these patients.

Pain disorder: These patients are a great source of frustration for primary care physicians. Their main complaint is significantly distressing pain, with no identifiable cause. Physical exam and imaging are all normal, but patients continue to suffer from terrible back pain, for example, that affects their daily life. In obtaining a thorough history, it is clear that psychological factors such as depression or stress about a job play a big role in this pain. Pain disorder is chronic and disabling. Because the pain is not organic, analgesics are not helpful and can actually be harmful (via side effects or addiction). SSRIs and psychotherapy can help.

Pain disorder: These patients are a great source of frustration for primary care physicians. Their main complaint is significantly distressing pain, with no identifiable cause. Physical exam and imaging are all normal, but patients continue to suffer from terrible back pain, for example, that affects their daily life. In obtaining a thorough history, it is clear that psychological factors such as depression or stress about a job play a big role in this pain. Pain disorder is chronic and disabling. Because the pain is not organic, analgesics are not helpful and can actually be harmful (via side effects or addiction). SSRIs and psychotherapy can help.

Personality Disorders

Personality is something that is stable across multiple situations and affects how someone reacts to different events in their life. Patients with personality disorders have atypical or troubling aspects of their personality that cause significant distress or impair daily functioning. Personality disorders are difficult to treat and most have a chronic course.

Cluster A: Weird

This group of personality disorders contains people who are just odd. Some of these disorders have a familial association with schizophrenia (i.e., the patient has a family history of schizophrenia); they themselves do not meet criteria for schizophrenia.

Paranoid: These people just don’t trust others. They always think that others have ulterior motives for what they’re doing. In contrast to psychotic patients (who may be paranoid that the CIA has implanted a mind-controlling device in their brain), their mistrust is less bizarre. For example, a man may be preoccupied with concerns that his wife is cheating on him with his boss.

Paranoid: These people just don’t trust others. They always think that others have ulterior motives for what they’re doing. In contrast to psychotic patients (who may be paranoid that the CIA has implanted a mind-controlling device in their brain), their mistrust is less bizarre. For example, a man may be preoccupied with concerns that his wife is cheating on him with his boss.

Schizoid: Despite the name, patients with schizoid personality disorder do not share many characteristics with schizophrenics. These people are cold, withdrawn, and have little interest in friends, romance, or sex. They can be thought of simplistically as emotionless robots. Mnemonic: “Schizoid” rhymes with “android”). They do not have any delusions or hallucinations.

Schizoid: Despite the name, patients with schizoid personality disorder do not share many characteristics with schizophrenics. These people are cold, withdrawn, and have little interest in friends, romance, or sex. They can be thought of simplistically as emotionless robots. Mnemonic: “Schizoid” rhymes with “android”). They do not have any delusions or hallucinations.

Schizotypal: Again, these patients do not meet criteria for schizophrenia, but their personality is characterized by odd magical beliefs (e.g., a belief in telepathy or aliens) and eccentric clothing (e.g., a man wearing a woman’s flowered dress over cargo pants with a long cape). Like those with schizoid personality disorder, these people have difficulty with relationships, but they actually have quite a bit of anxiety about it. (Recall that schizoid patients are indifferent to relationships.)

Schizotypal: Again, these patients do not meet criteria for schizophrenia, but their personality is characterized by odd magical beliefs (e.g., a belief in telepathy or aliens) and eccentric clothing (e.g., a man wearing a woman’s flowered dress over cargo pants with a long cape). Like those with schizoid personality disorder, these people have difficulty with relationships, but they actually have quite a bit of anxiety about it. (Recall that schizoid patients are indifferent to relationships.)

Cluster B: Wild

These patients are impulsive, emotional, and dramatic. Many of them have a family history of mood disorders.

Antisocial: These are the “bad boys” and criminals. They demonstrate a persistent disregard for the rights of others. Recall the description of conduct disorder; when those patients reach the age of 18, they gain the title of antisocial personality disorder. Similarly, these patients are prone to breaking the law (e.g., stealing, assault, and even murder). They are impulsive and poor planners; they do not think about consequences of their actions for either themselves or others.

Antisocial: These are the “bad boys” and criminals. They demonstrate a persistent disregard for the rights of others. Recall the description of conduct disorder; when those patients reach the age of 18, they gain the title of antisocial personality disorder. Similarly, these patients are prone to breaking the law (e.g., stealing, assault, and even murder). They are impulsive and poor planners; they do not think about consequences of their actions for either themselves or others.