If you’re ready to jump in and make paper, using items you already have in your kitchen, tin can papermaking is for you! Simply rescue a few tin cans, plastic bottles, and other containers from the trash, pull out a blender, and you’ve got what you need to start making your own recycled paper. Also covered in this chapter is a super-easy way to make paper with a pour mold. All you need are curiosity and a willingness to experiment. You’ll have a stack of handmade paper in no time!

The first sheet of paper was likely made with a pour hand mold. In this method of papermaking, a mold is placed in a vat of water and pulp is poured into the mold only, not into the vat. Another way to make paper is by using the dip method, which involves dipping a mold into a vat that contains pulp. The dip method was the only method used by European and American papermakers of the past and is considered the more traditional way to make paper.

For home papermaking, I’ve found the pour method to be the better way to go. The pour mold generally has higher deckle walls than a dip mold and can move easily from one type or color of sheet to another. A pour mold requires less preparation and cleanup than a dip mold and can make sheets not practical for a dip mold. Consequently, this method tends to be more versatile. I believe that anyone capable of lifting a pour mold out of water and holding it level while water drains will make a near-perfect sheet the first time he or she tries, regardless of age, handicap, intellectual level, or aptitude for “art.” For these reasons, the primary focus of this book is the pour method. However, since many readers may already be using the dip method, I’ve included information for that method as well.

In a traditional dip mold, the top deckle is only about ¾″ high, to allow pulp to more easily flow into the mold from the vat. The bottom support screen has a finer mesh, which serves as the papermaking screen. For my dip hand molds, I use the same support screen and papermaking screen as is used for the pour hand mold.

The procedure is basically the same as for pour hand molds (see page 52), but here are a couple of extra tips. After assembling your mold and preparing your pulp, here are the next steps:

Select a vat large enough to accommodate the dip hand mold and your hands on each side. Pour prepared pulp into the vat until it is deep enough for the hand mold to be dipped totally beneath the pulp’s surface. Actually, deeper is better.

Select a vat large enough to accommodate the dip hand mold and your hands on each side. Pour prepared pulp into the vat until it is deep enough for the hand mold to be dipped totally beneath the pulp’s surface. Actually, deeper is better.

Grasp both sides of the hand mold and dip it into the pulp vertically. Turn the hand mold slowly to a horizontal position against the vat’s bottom, then lift it up and out of the pulp.

Grasp both sides of the hand mold and dip it into the pulp vertically. Turn the hand mold slowly to a horizontal position against the vat’s bottom, then lift it up and out of the pulp.

Remove the deckle from the screen. Couch the sheet off the screen, press it, and let it dry. Repeat. Note the thickness of each sheet. When the sheets get too thin, add more pulp to the vat. With very small vats, this can be after every two or three sheets.

Remove the deckle from the screen. Couch the sheet off the screen, press it, and let it dry. Repeat. Note the thickness of each sheet. When the sheets get too thin, add more pulp to the vat. With very small vats, this can be after every two or three sheets.

Using modern materials, I designed a simplified dip hand mold that uses the same papermaking and support screens as the pour hand mold.

This technique, a variation on the pour method, is the simplest and cheapest way to start making your own paper at home. The basic supplies for tin can papermaking are pretty much the same as for regular handmade paper, with just a couple of modifications. The paper you make will be round, unless you experiment with other shaped containers to put on top of your screen. What can you do with round paper? You might be surprised by the variety of projects you’ll find in chapter 8.

As listed on page 25, you’ll need a blender, drain pan, sponge, paper towels, a pressing board, and a clothes iron. The rest of what you will need:

Mold and deckle options. Select two containers: one large one for the bottom to catch the water runoff, and one of equal size or smaller for the top. These can be tin cans, juice containers, milk jugs, or handmade molds (see page 80). The top container will serve as the deckle and should have both ends cut out. Whatever its size and shape, that’s what your paper will be.

Papermaking screen. A nonmetal piece of fine-mesh window screen, available inexpensively at hardware stores, makes a good papermaking screen. You’ll need at least two 6" squares, or larger if your top container is larger. Window screen is right on the edge of being too coarse for papermaking, but most of the time it will work. Later, you might want to experiment with other “sieves,” such as stiff pellon or coarse cloth.

Support screen. The support screen can have larger holes and needs to be quite rigid, since your papermaking screen will rest on top of it. Plastic needlework canvas works well and is available in craft and fabric stores. Hardware cloth, made from metal, is available at hardware stores. It comes in a variety of mesh sizes, and any of them will work fine. After cutting it to size, wrap duct tape around any sharp edges before using, so no one gets cut. A 6" square support screen is a good size for most food and beverage cans. Larger sizes are necessary for larger diameter cans.

Containers. A measuring cup will help you control the amount of water you use, and you’ll need a couple of containers (such as tall plastic cups) for dividing up and pouring the pulp into the mold.

Tip

Any time you use a tin can for your mold, make sure to tape any sharp edges to prevent injury. For techniques that may involve reaching into the mold to manipulate the pulp, it’s best to find a shorter can.

Step 1. Set a tin can, with one end cut out and facing up, into a drain pan. Over the open end, place a support screen, followed by a papermaking screen.

Step 2. Place a canister with both ends cut out over the window screen. If the cans are of the same size, match their rims. (The can on top can be smaller, but not larger, than the bottom can.) Presto! You have set up a “pour” hand mold with which you can make handmade paper.

Step 3. For a 4″ to 5″ diameter top can, pick a 7″ square of waste or used paper, or smaller pieces of several papers that add up to a 7″ square. Tear the paper into small pieces and put them in a blender. Add about 1½ cups water. Put on the lid and run the blender for 20 to 30 seconds.

Step 4. Pour half the blender’s contents into each of two containers and add ½ cup water to each container.

Step 5. With a container in each hand, dump the contents of both containers at the same time into the top can. Pour from opposite sides so that streams from both containers hit each other. Let all water drain into the bottom can.

The two-handed pour will likely distribute the fibers more evenly on the screen, giving you a nicer sheet. One-handed pouring can sometimes cause fibers to swirl around the outside edge of the can and make a donut sheet with a thin spot or hole in the middle. But you can give it a try: Simply pour the pulp into one container instead of two and add a cup of water. Hold the top can down with one hand and pour with the other.

How much paper do you put in the blender? A general guideline is to put in a little more waste paper than it takes to cover the top can’s opening. This will give you a handmade sheet about as thick as the waste paper you put in. The more waste paper you put in, the thicker the new sheet. The less waste paper you put in, the thinner the new sheet. (For more precise information, see Recycling Formulas for Pulp on page 48.)

Step 6. Raise the top can straight up and off the screen. Lift both screens (with your new sheet of paper on it) and remove the tin can base. Place the screens back into the drain pan or onto a flat surface that is not harmed by water (such as a tabletop with several layers of cloth or a piece of plastic). Place another 6″ square piece of window screen over the new sheet.

Step 7. Take a dry sponge and press it down on top of the window screen and new sheet. Squeeze water from the sponge. Continue pressing and squeezing until the entire sheet has been covered and the sponge removes little, or no more, water.

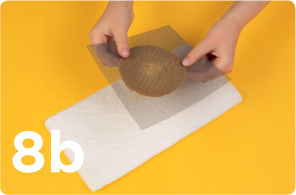

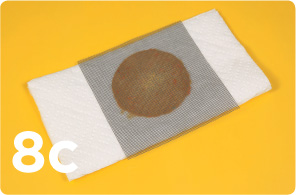

Step 8. Carefully, starting at any corner, peel off the top window screen. Lay down three folded paper towels on top of each other. When folded, the towels must be wider than the new sheet. If not, get bigger towels, or don’t fold them. Pick up the screen with the new sheet on it, and turn it over onto the towels so the new sheet is on the top towel.

Step 9. Apply the sponge as in step 7, this time pushing down with as much force as possible. Apply pressure over the entire new sheet. This is so the new sheet will stay with the towels when the screen is peeled off. Starting slowly at a corner, peel off the window screen, leaving the new sheet on the towels. If the sheet rises with the screen, apply the sponge again with all the force you can. If the sheet still rises with the screen, carefully peel a corner of the new sheet from the screen and separate them with care. At the end of this step, the new sheet should be on top of the paper towels.

Step 10. Fold 3 more paper towels. Place them on top of the new sheet. Take a flat piece of wood, or other flat item, and press down hard on top of the dry towels.

Step 11. Remove the top wet towels and replace them with dry ones. Repeat pressing, replacing wet towels with dry ones until little water is removed with the dry towels. When the new sheet has become strong enough, lift if off the wet towels beneath it. Replace the wet towels with dry ones. The idea is to get as much water out of the new sheet as possible. Note: Do not throw wet towels away. Lay them out to dry and reuse them in future papermaking.

Step 12. Put the new sheet on an ironing board or other dry, clean surface that will not be harmed by heat. Turn a clothes iron to its top heat setting and iron the new sheet dry. Move the iron slowly but steadily, so all parts of the sheet dry at about the same rate. Note: Placing a thin cloth over the sheet for ironing is wise. It protects the iron’s surface from possible heat-sticky additives that might have been in the recycled paper.

When the sheet is dry, you can shout, wave your arms, sing the national anthem, call neighbors over, and e-mail reporters and photographers from local newspaper, radio, and TV stations. You are an artist and an environmentalist!

This book advocates placing a thin cloth between the wet paper sheet and the iron. You can try drying sheets by placing a hot iron directly onto the wet sheet, but it’s risky. Fiber(s) might stick to the iron, and in two more strokes, the sheet surface can be seriously disrupted. If you don’t use a cloth, add to the sheet’s safety by using a Teflon-coated iron. Of course, even Teflon can’t protect against materials melting in the sheet, especially if you’ve added bits of plastic or other sensitive elements.

Before I get into more advanced methods, let’s talk about pulp. In chapter 2, I talked about where to find pulp and generally how to use it. Now it’s time for a few more specifics. For instance, how do you know how much recycled paper and water to put in the blender?

The answer comes from a basic rationale. Fibers are hydrophilic. In water, they swell like a sponge, requiring more room than when dry. There must be enough water to provide room for fiber swelling and fiber movement away from each other. Enough water must be put in the blender to provide that kind of room (see Recycling Formulas for Pulp, at right). The more new pulp or wastepaper put in, the more water is required. One advantage to the pour method is that you can be more precise about the amount of pulp to use, knowing that all of what you prepare will go into the sheet you are making. With the dip method, it’s more difficult to know just how much pulp you are capturing in the mold.

Pour Molds

For a 5½″ × 8½″ mold, recycle ¾ of an 8½″ × 11″ paper sheet with 2 to 2½ cups water.

For a 5½″ × 8½″ mold, recycle ¾ of an 8½″ × 11″ paper sheet with 2 to 2½ cups water.

For an 8½″ × 11″ mold, recycle 1¼ to 1½ sheets of 8½″ × 11″ paper in 3 to 3½ cups water.

For an 8½″ × 11″ mold, recycle 1¼ to 1½ sheets of 8½″ × 11″ paper in 3 to 3½ cups water.

For other sizes, follow the general rule of tearing up a piece of paper that is a bit larger than the measurements of the pour mold’s deckle. Smaller pieces of paper that together equal sizes listed above can be torn up instead of single pieces.

For other sizes, follow the general rule of tearing up a piece of paper that is a bit larger than the measurements of the pour mold’s deckle. Smaller pieces of paper that together equal sizes listed above can be torn up instead of single pieces.

Dip Molds

Pulp preparation aims at a pulp thickness in the vat, not at a size of sheet to be made. For a pulp consistency that will make sheets about as thick as stationery, business letters, or book pages, use the following formula.

Tear up an 8½″ × 11″ sheet and add 4 cups water. Run the blender. Pour the recycled pulp into a vat. Repeat until there are 4″ or more of pulp in the vat.

Tear up an 8½″ × 11″ sheet and add 4 cups water. Run the blender. Pour the recycled pulp into a vat. Repeat until there are 4″ or more of pulp in the vat.

Dip 2 or 3 sheets and then add pulp to the vat according to the following ratio: Add 3 cups water for every 8½″ × 11″ sheet. Run the blender. Add the pulp to the vat.

Dip 2 or 3 sheets and then add pulp to the vat according to the following ratio: Add 3 cups water for every 8½″ × 11″ sheet. Run the blender. Add the pulp to the vat.

For new pulp, follow the directions provided with the pulp. If no directions are provided, experiment. Estimate the amount of pulp needed. Add plenty of water, run the blender, and form a sheet. Here are some pointers:

For a pour mold: If the sheet is too thick, take part of the pulp off the screen. Lower the mold in the water again. Disperse the remaining pulp in the deckle and form a new sheet. Repeat the removal or addition of pulp process until you have the right thickness. The amount of pulp removed or added will indicate how much dry pulp is the right starting amount.

For a dip mold: If the formed sheet is too thick, either add water to the vat or remove pulp with a strainer. Dip a new sheet. Continue this process until the vat’s pulp consistency is right.

The sheet thickness can be controlled by varying the ratio of fiber to water in the pulp slurry. With pour molds, thickness can be controlled easily and precisely. With dip molds, it’s a bit tricky.

For a pour mold: When recycling, the following provides precise control. Tear and blend a piece of paper that is the same length and width as the deckle. The new sheet made from that pulp will be of the same thickness as the paper recycled. This provides a reference point. To make a new sheet twice as thick, recycle twice the paper, adjusting the amount of water added in the blender. For a sheet half as thick, recycle half as much paper.

When starting with new pulp, preciseness is not as easy. As stated previously, you can guess at how much dry pulp to blend, see what thickness results, and work from that as a reference point. Or, with an appropriate scale, you can weigh out an estimated amount of dry pulp, disperse it in a blender, see what thickness results from that amount, and work mathematically from that as a reference point.

For a dip mold: With dip molds, you must alter the thickness of the slurry in the vat to change the thickness of paper. Adding pulp will make the next sheets thicker. Adding water or removing pulp with a strainer will make the next sheets thinner.

The thickness fact to remember with the dip mold is that each time you make a sheet of paper, you remove pulp from the vat. The fiber stays out, but the water runs back in. Therefore, the slurry in the vat is thinner, and the following sheet will be thinner, unless you replace the amount of fiber taken out.

Turbulence in the deckle of a pour hand mold is important to the uniformity of the final sheet. Wiggle your fingers in the slurry or stir with a spoon to disperse the pulp evenly. Don’t be shy. It also helps to keep a pour mold low in the vat’s water. For dip molds, agitate the pulp before each dip.

A pour hand mold can be built to any size desired. The dimensions suggested here will produce a hand mold for handmade sheets approximately 5½″ × 8½″.

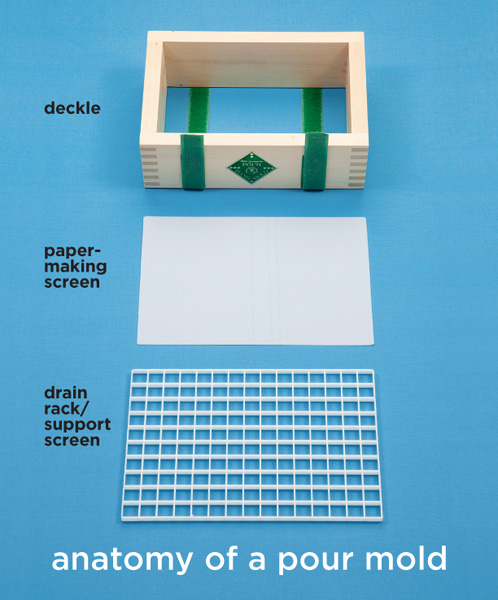

The pour mold that I designed (shown at right) uses a plastic grid (egg crate) for the support screen instead of a wooden frame topped with hardware cloth. A papermaking screen is placed between the deckle (top frame) and the support screen.

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 3″ × 10″

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 3″ × 10″

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 3″ × 5½″

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 3″ × 5½″

1¼″ finishing nails and a hammer (or a pneumatic stapler, if available)

1¼″ finishing nails and a hammer (or a pneumatic stapler, if available)

Heavy-duty staples and a staple gun

Heavy-duty staples and a staple gun

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 1″ × 10″

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 1″ × 10″

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 1″ × 5½″

Two pieces of finished wood, 1″ × 1″ × 5½″

Hardware cloth 5½″ × 10″

Hardware cloth 5½″ × 10″

One screen, 5½″ × 10″ (commercial papermaking screen or nonmetal window screen)

One screen, 5½″ × 10″ (commercial papermaking screen or nonmetal window screen)

Approximately 1 yard of nonadhesive Velcro, 1″ wide

Approximately 1 yard of nonadhesive Velcro, 1″ wide

The finished, assembled mold includes the deckle (top frame with straps), the support screen (frame with screen at the bottom), and a papermaking screen (sandwiched between the two).

1. Form the deckle by nailing the 1″ × 3″ × 10″ wood pieces to the 1″ × 3″ × 5½″ pieces as shown, to create a rectangular frame.

2. Form the screen support (or mold) by nailing the 1″ × 1″ × 10″ wood pieces to the 1″ × 1″ × 5½″ pieces as shown, to create a rectangular frame. Cover the frame with hardware cloth, and secure it with staples (using either a hammer or staple gun).

3. Place the papermaking screen on top of the screen support and then place the deckle on top of the screen.

4. You’ll need to secure the screen support tightly against the deckle for sheet formation, but be able to loosen it to remove the screen support and new sheet after sheet formation. The most efficient way to do this is to add Velcro straps:

With the support screen in place, measure down the side of the deckle, around the bottom, and up the other side. Cut two strips of the loop side of the Velcro to this length.

With the support screen in place, measure down the side of the deckle, around the bottom, and up the other side. Cut two strips of the loop side of the Velcro to this length.

Staple one end of each strap to one side of the deckle as shown, about 2″ from either edge.

Staple one end of each strap to one side of the deckle as shown, about 2″ from either edge.

On the opposite side of the deckle, place two 2¼″ strips of the hook side of the Velcro in the same locations.

On the opposite side of the deckle, place two 2¼″ strips of the hook side of the Velcro in the same locations.

Wrap the looped strip around the deckle, papermaking screen, and support screen, and press the ends onto the 2¼″ hook strips.

Wrap the looped strip around the deckle, papermaking screen, and support screen, and press the ends onto the 2¼″ hook strips.

The basic steps for making paper are essentially the same no matter what technique you use. Since I am recommending the pour method as the easiest to use, the directions are shown using the style of pour hand mold I developed (see page 50).

In addition to the hand mold, you will need a cover screen: a piece of nonmetallic window screen a bit bigger than the sheet you’re making. You will also need the supplies listed below (explained in more detail on page 25). If you are using a dip mold, see page 41 for more information.

Blender

Blender

Vat

Vat

Drain pan

Drain pan

Sponge

Sponge

Couch sheets

Couch sheets

Press bar

Press bar

Iron

Iron

Step 1. Gather your supplies and prepare the pulp (see page 48).

Step 2. To assemble the hand mold, place the deckle upside down on a flat surface. Lay the papermaking screen on the deckle, then the screen support. Pull the Velcro straps tightly around the grid and press them against the Velcro strips on the opposite side.

Step 3. Turn the hand mold right side up and lower it at a slanted angle into the water in a vat (tub or dishpan). The water must be deep enough to fill the deckle about halfway. Pour pulp into the deckle. By wiggling your fingers or stirring with a plastic spoon, spread the pulp evenly in the water within the deckle.

Step 4. Lift the hand mold out of the water. Hold it level and let all the water drain.

The “papermaker’s shake” was once part of a journeyman hand–papermaker’s skill. It was vital for certain qualities and characteristics of professional sheets. In general, it entailed shaking the hand mold forward and backward and from side-to-side after it had been lifted from the vat and while the pulp drained. The shake can be done with either pour or dip molds.

Step 5. Set the hand mold down in a drain pan. Loosen the straps. Lift the deckle up and off of the screen and screen support. If the screen lifts with the deckle, separate the two with your fingernail or a knife blade.

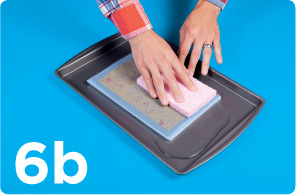

Step 6. Set the deckle aside and carefully put the cover screen over the new sheet resting on the screen support. Press a sponge firmly down on the cover screen. Wring the sponge. Press again. Continue until the sponge removes no more water.

Step 7. Lift a corner of the cover screen carefully and peel it off slowly. If the sheet comes up with the screen, try the other corners. Once the screen is removed, pick up the papermaking screen with the new sheet on it. Turn the screen over, placing the new sheet on a couch sheet. The new sheet will be between the screen and couch sheet.

Step 8. Press a sponge firmly all over the screen’s surface. Wring the sponge and press again. Repeat until the sponge removes hardly any water. To remove the screen, place one hand on the middle and the other hand at a corner. Slowly lift the corner and peel off the screen, sliding one hand back as the other lifts. If the sheet comes up with the screen, press down hard on each corner and try lifting at each.

Step 9. Put a dry couch sheet over the new sheet. With a press bar, press down hard over the entire surface of the couch sheet until the couch sheet has absorbed as much water as it can.

Step 10. Take off the top couch sheet and then carefully lift one corner of the new sheet. If the sheet is too weak to lift up, repeat step 9 with a dry couch sheet. When a corner can be lifted, you’ll be able to peel it off the couch sheet.

Step 11. Place the new sheet on an ironing board or on a cloth-covered flat surface. Place a thin cloth over the sheet and iron the sheet dry with an iron turned up to maximum heat (no steam).

Heat drying delivers paper immediately, but generally causes the paper to curl and cockle. Drying without heat is better for some paper qualities and delivers a better-looking sheet. For best quality, dry your paper slowly, under pressure. Curing occurs, as well as drying, during time under pressure. The longer the paper is under pressure, the more some qualities will be enhanced. Here’s what you do:

Complete step 10 (see page 55) and place the paper between two dry couch sheets.

Complete step 10 (see page 55) and place the paper between two dry couch sheets.

Use a press if you have one (see Building a Paper Press, page 34), or place the sheet (between couch sheets) between two boards and stack weight (for instance, books or cement blocks) on the top board.

Use a press if you have one (see Building a Paper Press, page 34), or place the sheet (between couch sheets) between two boards and stack weight (for instance, books or cement blocks) on the top board.

Wait 20 minutes and exchange the wet couch sheets for dry ones.

Wait 20 minutes and exchange the wet couch sheets for dry ones.

Wait 2 hours and change couch sheets again. Leave the paper under pressure for 5 or 6 hours more, or better yet, overnight.

Wait 2 hours and change couch sheets again. Leave the paper under pressure for 5 or 6 hours more, or better yet, overnight.

Check paper for dryness. If it’s not too thick, the paper should be dry. If not dry, keep exchanging couch sheets until it is.

Check paper for dryness. If it’s not too thick, the paper should be dry. If not dry, keep exchanging couch sheets until it is.

Instead of stacking weights on top of the boards, you can use two strong clamps to keep the paper under pressure.

Q: Can I make paper out of lint from my dryer?

A: Ah, my favorite question not to answer! Paper is cellulose fibers naturally bonded. If your lint is synthetic, the fibers won’t bond. They might hang together by friction due to their length. Even if enough of the lint fibers are natural, wet lint is horribly hard to disperse in the vat or in the deckle of a hand mold to form a new sheet. But with a high enough percentage of cellulose fiber and patience to get reasonable dispersion, a hint of lint can impart character to a sheet.

Q: I left pulp in water for a couple of days and it got smelly. Can I still use it?

A: Normally, wet pulp will not become smelly in a day, but it can spoil and smell if left for a couple days in warm weather. When pulp that smells is made into new dry sheets, the paper will normally not smell.

Q: What should I do with leftover pulp?

A: You can drain the pulp and store it in an airtight container in your refrigerator. When you’re ready to use it, add water and reprocess in a blender. Another option is to drain the pulp and pack it into a casting mold. Let it dry, and you will have a paper casting (see chapter 7). Never dump leftover pulp down sink drains, as it may cause plumbing problems.

Q: Does using an iron to dry paper hurt the paper?

A: Subtly, yes, but sometimes we are willing to accept the subtle harm to have our paper immediately. Visible harm occurs if you iron in a manner that chars surface fibers, such as leaving the iron too long in one spot or making thick paper that requires too much heat to dry. If it bothers you to iron right on the sheet, you can use a thin cloth over the fibers before applying the iron.

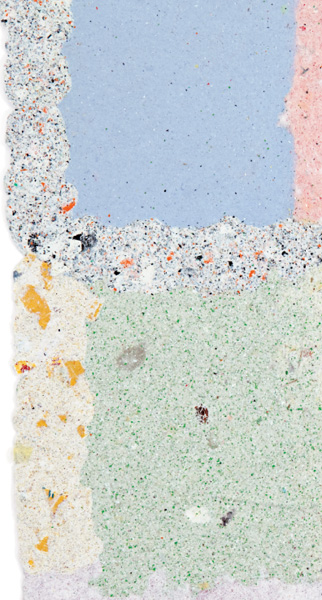

Q: How can I make a ″pure” sheet of paper that isn’t drab or speckled from ink?

A: Select sections of paper to recycle that have no printing on them. Unprinted margins are the main place to look, but other significant sources of unprinted paper are available. Envelopes and colorful retail store bags deliver large areas of unprinted surface, with subtle to spectacular colors.

Q: I’m getting a thin spot in my paper. What can I do?

A: This usually occurs with professional papermaking screens, which are very finely woven. Consequently, fibers can get stuck easily in the tiny openings. Stuck fibers will cause more to get stuck. Soon a sizeable spot in your screen is plugged. This prevents water from going through those openings. Where water doesn’t go, fibers don’t go, resulting in a thin spot, or even a hole, in your sheet.

To avoid this problem, rinse your screen in clear water after every sheet. Watch your screen for ″plugs” and loosen them with water pressure from your sink spray. Apply a stiff brush as the water is running. Dishwasher detergent might help.

Another measure might help: When a thin spot appears in a newly formed sheet, remove pulp in that area of the screen. Scratch the screen surface with a thumbnail or wire brush. Refloat the pulp and form the sheet again. Often, the thin spot does not reoccur.

Q: The papermaking screen is leaving a pattern on my paper. Is there a way to avoid it?

A: Anything touching the wet surface of a newly formed sheet will leave its impression. This is very noticeable with papermaking or cover screens that are as coarse as window screen. If you don’t like this effect, try using a thin cloth for a cover screen instead of window screen. I use cut-up cotton bed sheets, but handkerchiefs, cotton dish towels, or lightweight interfacing from the fabric store also work. The cloth’s surface (texture, weave, pattern) will be placed on that one side of the sheet. You can also try removing the window screen as soon as possible and after removing as little water as possible. Place a cloth on that surface as well, and keep it on throughout pressing and drying. If enough water remained in the sheet, this procedure may entirely remove the window screen marks. If drying with heat (by ironing), make sure that the cloth can take the heat. This means no synthetics.

Q: I burned out two blenders this year. Is that normal?

A: You are almost surely putting too much paper in the blender and not enough water. When the mixture in the blender is too thick, the motor can’t get the blender blades through it. Put in less paper and more water so the blender starts up and runs easily.

A good rule of thumb is not to exceed the equivalent of an 8½″ × 11″ sheet of copy paper in the blender. Use 3 to 4 cups of water. Adjust measurements when recycling thicker paper. Loaded properly, blenders can last for years.

What if you want to make a sheet larger than a standard mold-and-deckle size? It will take a bit of patience, but it can be done. Here’s one way to go about it, and you might think up others!

1. Find a smooth hard surface larger than the sheet you are planning. The surface might be a waterproof tabletop, acrylic or laminate sheets, a repurposed window or patio glass door (think safety), or any similar surface you can imagine.

2. Spray it with a release agent (see page 128). Form a sheet with your hand mold. Remove the screen and sheet. Turn them upside down and deposit the wet sheet on the hard surface. The screen will be on top. Press a sponge on the screen to remove some, but not all, water. This will ″couch” the sheet off the screen onto the surface.

3. Remove the screen. Make a second sheet and couch it onto the hard surface the same way as the first, but slightly overlap the edges of the first and second sheets. Because water is present, the sheets will bond where they are overlapped.

4. Continue this process with as many sheets as necessary to reach the desired sheet size. To smooth overlaps, spray a bit of water on them (not much, just a bit). Tap the overlapped areas with a toothbrush. Mobility of fibers due to being wetted and the action of toothbrush bristles will tend to resurface the sheet where tapped.

5. Put some window screen over the sheet, a section at a time or the entire surface at once, and remove water with a sponge. Press by putting couch sheets or toweling over the sheet and pressing with a large board all at once, or a section at a time with a smaller press board.

6. Press again, as in step 5, using as much pressure as possible. If you have pressed reasonably hard, the sheet can be left on the surface to air dry.

Usually, but not always, the sheet will retain contact with the surface until dry, providing a beautiful evenly dried sheet. Sometimes, contact is too firm and getting the sheet to release is difficult; sometimes, contact will not last and the sheet will release and dry unevenly, creating cockle and curl. In the latter case, use a spray mister to evenly dampen the sheet and press between two boards for several hours.

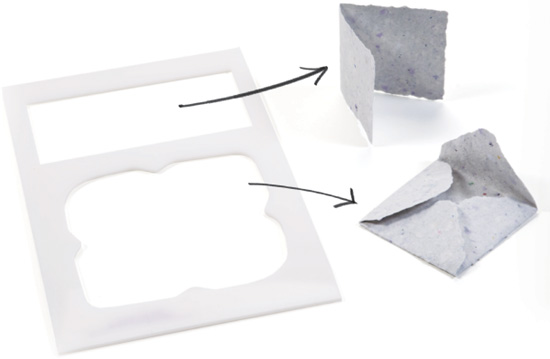

Placed on top of the papermaking screen, a deckle determines the shape and size of the sheet. Usually this shape matches the outer size and shape of the mold beneath it. If a piece of flat material with an image cut out of it is placed on top of the screen but under the deckle, the sheet formed will be the size and shape of the cut-out area. You can buy ready-made templates from papermaking suppliers, or make your own from food board, foam core, wood, plastic, or even metal (see Handmade Molds and Templates, pages 80–81).

Each paper sheet made with this template produces a folded card and envelope to fit. The plastic version is available online, or trace the template on page 201 onto foam board and cut your own.