It is difficult to overemphasize the importance of color in shaping the critical reception of Impressionism. The unusual brightness of Impressionists’ palettes and visible materiality of their colors, which frankly asserted themselves as “real paint that came from tubes or pots,” immediately drew critics’ attention.1 In this as well as other important regards, the response to Impressionism closely aligned itself with that generated by contemporary fashion, the growing chromatic variety and vibrancy of which Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet and other members of the movement gleefully explored in their paintings. Take, for instance, Monet’s Women in the Garden (1866), a painting whose similarities with the fashion plates that appeared in La Mode illustrée and other fashion magazines of the period, such as Le Monde élégant and Le Courrier des dames, is a powerful reminder of the close cultural connection between flowers, femininity, and fashion in nineteenth-century France (fig. 23).2 “It takes a singular love of one’s time to dare such a tour de force—materials cut in two by shadow and sun, well-dressed ladies in a flower garden carefully combed by the rake of a gardener,” Émile Zola observed about the painting, establishing the groundwork for what would eventually become a dominant theme in Impressionist studies.3 Indeed, as several art historians have demonstrated, building from Zola’s and others’ early critical responses to Impressionism, one of the predominant ways in which Monet and his circle asserted the beauty and significance of modern life, as well as their own significance as artists, was through the depiction of the colorful contemporary dress of their times.4

FIGURE 23

Claude Monet, Women in the Garden, ca. 1866. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

The goal of this chapter is to bring together the analysis of Impressionist color and Impressionist fashion in a way that significantly revises the interpretation of both, while providing an original reading of how these artists’ works redefined dominant understandings of realism in nineteenth-century France. More specifically, focusing on relevant art criticism and select works by Degas, Renoir, and Monet, chosen for their complementary approaches to both color and fashion, this chapter shows how Impressionism both mirrored and mediated the large-scale visual transformation of nineteenth-century color technologies, in particular those technologies derived from the art and business of chemistry discussed in chapter 1. As we have seen, this transformation was marked in the late 1850s by the introduction of new synthetic dyes, which brought more color and variety of color to material and visual culture. In addition to being incredibly varied and bright, however, these new dyes were notoriously unstable, rapidly fading and turning when exposed to sunlight, washing, and other chemical or physical agents. Hence, more than simply adding an extra element of style and distinction to everyday life, these new synthetic dyes also generated considerable anxiety about the nature of materials and appearances in modern consumer culture.

Far more than floriculture, gardening, or any other singular good, technology, or practice, the new organic chemistry of synthetic colors had an immediate and powerful impact on Impressionism. Indeed, as we now know, thanks to Anthea Callen and the expert conservators at the National Gallery in London, among others, the Impressionists used a variety of synthetic pigments in their work.5 Yet, as I hope to make clear in this chapter, the influence of color chemistry on Impressionism went far beyond just the materials the artists associated with this movement sometimes used into the very way they saw and represented the world around them. Impressionists sought to fix on canvas the bariolage of everyday life—the multiple and shifting play of colors that characterized the modern world. In their combined investigation of modern life—la mode, in particular—and the material stuff of painting, Impressionists participated in the elaboration of a chemical aesthetic, centered on a critical exploration of modern industrial colors’ variety, vividness, and inherently fugitive nature.

The artworks considered in this chapter reenacted and exposed the seductions and uncertainties offered by modern color chemistry. The color revolution of the nineteenth century, Impressionists understood, was a revolution not only in scientific and philosophical thinking about color but also in everyday aesthetics and semiotics.6 Synthetic colors, both aniline-and azo-based, found themselves in not only dyes and paints of all kinds but also inks and foodstuffs.7 Simultaneously contributing to and commenting on this bright new world, Impressionists’ paintings showed how capitalism’s chemical color palette fundamentally revised traditional ways of making meaning, in addition to ways of making money.

Impressionism was always about much more than the passive empirical recording of natural light. Yet while recent discussions of how Impressionism challenged optical realism primarily draw upon the nineteenth-century science of psycho-physics, including aspects of Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s color theory, the evidence offered in this chapter points instead to artists’ critical engagement with their immediate visual environment and the materials of their craft.8 Impressionists’ inspiration for disrupting the visual conventions of realism came less from the philosophical and scientific theories about visual perception that emerged in the early and mid-nineteenth century than from the everyday experience of seeing and, moreover, actively contributing to the emergence of a more colorful world than had ever existed before.

Responses to Impressionism’s Larger, Brighter Palette

In an 1888 article on Monet, English journalist E. M. Rashdall introduced the provocative idea that modern art’s most notable achievement lay in its treatment of color. “Present day art is so bewilderingly complex, so apparently catholic in its aims,” he wrote, “that it is a little difficult to satisfy oneself as to its real motives, its chief characteristics. But of this, at least, we may be tolerably certain, that however inferior in some respects to that of the ‘ancients’ in the matter of color, at any rate, modern art has struck out a new line and achieved successes which were unknown before.” Impressionists, he reasoned, had particular reason to be proud of their accomplishments in this area: “It doubtless had other aims besides, aims at concentration of interest and elimination of what is merely conventional; but, after all, Impressionism is chiefly remarkable as an attempt to deal frankly with color.”9

The idea that Impressionism represented the triumph of color in painting was not a new one. In the wake of the Impressionists’ second group exhibition in 1876, realist author and critic Edmond Duranty observed, “As far as coloring is concerned, they have made a discovery of real originality, the sources of which cannot be found anywhere in the past, neither in the works of the Dutch school, nor in fresco painting, with its clear tones, nor in the light tonalities of the eighteenth century.”10 Critics both favorable and unfavorable to Impressionism generally came together on this point: color, they agreed, was a central focus of the new school. “The tackling of a subject for its colors and not for the subject itself, that’s what distinguishes the Impressionists from other painters,” noted Georges Rivière in 1877, anticipating the standard Formalist interpretation of Impressionism as marking the “liberation of color” as an autonomous element in picture making and the first important step toward twentieth-century abstraction.11

By the 1980s, this interpretation of Impressionism, generally identified with the critic Clement Greenberg, largely lost its appeal among art historians, who had become more interested in investigating the social and political dimensions of art.12 Formalist narratives gradually gave way to a variety of readings of la nouvelle peinture that reasserted the significance of subject matter, from Parisian urban life and leisure to fashion. However, neither the depiction of modern subject matter nor even Impressionists’ vigorous sketch-like brushwork was a complete novelty at the time. Indeed, as art historian Richard Shiff pointed out long ago, only in terms of color could Impressionists’ paintings be considered at all radical.13 In fact, according to critics of the movement, such as Victor Cherbuliez, counterintuitive colorwork was practically all Impressionism was good for. On the Impressionist exhibition of 1876, he wrote, “People who aren’t interested in doing things the hard way have [already] found a simpler definition of Impressionism: having visited the exhibition on rue Le Peletier, they have decided that the defining characteristic is painting trees red, grass pink, and skies lilac, while chuckling inwardly . . . and asking themselves, Will they fall for it?”14

Against these charges of insanity or, worse, deliberate misrepresentation of reality, Impressionists’ early supporters set out to prove that Monet, Renoir, and the other members of their group were realists in the purest and most rigorous sense of the word. Duranty, for instance, appealed to the authority of optics—the scientific study of the behavior of light—to defend Impressionists’ use of new eye-popping colors: “Moving from one intuition to the next, they have succeeded in decomposing sunlight into its rays, into its elements and [then] reconstituting the whole through the overall harmony of the iridescences with which they cover their canvases. . . . The most learned physicist wouldn’t find anything to reproach in their analysis of light.”15 Drawing upon the prestige of Isaac Newton’s prism, Impressionists’ colors, he thereby suggested, were not made of ordinary material pigments but rather were spectral in nature. Moreover, far from being imaginary or insane, Impressionists’ bright colors were irreproachably accurate representations of reality.

By the 1880s, critics’ assessments of Impressionists’ color palette showed the growing influence of Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution and the still-budding field of psychophysiological optics. Their basic argument remained largely the same, however. The allegedly irrational colors of Impressionism, supporters insisted, were nothing of the sort. In an essay originally written in 1883 for an exhibition of Impressionist works in Berlin, poet Jules Laforgue, for instance, posited that the stylistic differences between Impressionist and Academic painting had a legitimate physiological origin. “The Impressionist eye,” he declared, “is, in short, the most advanced eye in human evolution, the one which up until now has grasped and rendered the most complicated combination of colors known.” Human sight had previously been too tactile, Laforgue explained, too focused on line and contour. In the next phase, however, vision would be redirected toward the “living atmosphere of forms, decomposed, refracted, reflected by beings and things in incessant variation. This is the primary characteristic of the Impressionist eye.”16 Impressionists were thus neither charlatans nor colorblind but rather possessed a more evolved color sense than other humans; it was only a matter of time before others saw trees, water, skies, and flesh exactly as these pioneering artists did.

It was in the context of these early debates about the realistic and, moreover, scientific nature of Impressionism that critics first began making reference to Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s color theories. Writing in the Gazette des beaux-arts in 1883, Alfred de Lostalot highlighted, for instance, how Monet, whom he considered a prime representative of the new Impressionist school, “puts into practice the laws of contrasts, complementary colors, and irradiation.”17 De Lostalot insisted, however, on dissociating these theories from their most recent and best-known advocate, Chevreul. In de Lostalot’s view, the laws of contrast and complementary colors were already well understood by the Old Masters, including artists such as Veronese and Rubens, “who had penetrated [these secrets of nature] and put them into practice long before science moved to regulate them.”18

Writing a few years later, Rashdall reinforced this idea but again refrained from citing Chevreul by name. “The theory underlying Claude Monet’s practice,” he wrote, “is in the main the old and simple one, that color owes its brightness to force of contrast, rather than to its inherent qualities; that primary colors look brightest when they are brought into contrast with their complementary color, the brightness of red being greatest when next green, of yellow hen next purple, and so on.”19 Thus, like de Lostalot before him, Rashdall insisted that Monet’s color schemes depended on tried and tested artistic principles as opposed to recent scientific discoveries.

In avoiding citing Chevreul by name, Rashdall may have wanted to distance Monet from the younger and more radical generation of artists, including Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who had recently exhibited with the Impressionists and whose noted enthusiasm for scientific theories had attracted harsh criticism. Monet, in fact, had turned down the invitation to send works to the last group exhibition of the Impressionists, where Neo-Impressionists were cautiously welcomed to show their works. Monet was by now a well-established artist, whose contemporary fame and fortune, Rashdall insisted, were rightly deserved. Monet’s work, the journalist observed, “is quite free from the senseless mannerisms and conventionalities which paralyze the work of many Impressionists and pointellists [sic], whose pictures present often merely the interest due to an exemplification of certain properties of colors—works in which individuality has been swallowed up in formulae.”20

By the interwar period, critics and art historians were less hesitant to claim that a direct line of influence existed between the Impressionists’ bold experiments with color and the famed French chemists’ ideas. Writing in the late 1930s, Pierre Francastel was probably the first to bring the connection back to the critical fore. Drawing upon Duranty’s famous 1876 essay, he maintained that Impressionists quickly became dissatisfied with casually recording the appearance of colors in nature and began executing their paintings with contemporary scientific theories in mind, including, most notably, those of Chevreul: “Then, it was all about the direct investigation of light variations in connection to form conducted in plein air—that was still Renoir’s attitude in 1878—henceforth it was all about the physical analysis of light in and of itself, independently of form. The goal, like the processes, is different: it is no longer an investigation conducted on site, but the application of a doctrine; no longer trial and error, but science.”21 Moreover, the abrupt nature of this change makes it difficult, Francastel wrote, “not to consider as cause-effect relationship the sudden evolution of art around 1875 and the revelation of these modern theories.”22

Subsequent art historians, writing after Francastel, have generally been more cautious in their pronouncements, pointing out, for instance, how Impressionist artists must have been only vaguely familiar with Chevreul’s original text or, alternatively, specifically ignored its teachings on painting. For indeed, as Georges Roque insists, Chevreul provided decorative (or industrial) and fine artists with two very different sets of instructions. In particular, while Chevreul, as we have seen, clearly favored the juxtaposition of highly contrasting colors in textile design, interior decoration, gardening, and other nonimitative arts of ornamentation, he specifically discouraged their use in painting for fear that contrast effects would undermine the image’s realism.23 “To imitate the model faithfully, we must copy it differently from what we see it [to be],” Chevreul instructed.24 In practical terms, this means that faced, for example, with the task of painting poppies in a green grassy meadow, the artist wishing to follow the chemist’s advice would try to compensate for the illusion of heightened contrast created by the landscape by selecting paint colors closer together on the color wheel. The gulf between Chevreul’s advice to painters and Impressionist paintings is readily apparent; far from mitigating contrast effects, their paintings—from Monet’s Poppies at Argenteuil (1873) to Degas’s endless series of ballerinas—generally accentuate them (figs. 24 and 25).25

FIGURE 24

Claude Monet, Poppies at Argenteuil, 1873. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Still, despite these and other important differences between Chevreul’s and the Impressionists’ approaches to color, not to mention that none of the key figures associated with the group ever explicitly stated that they were familiar with the chemist’s theories, art historians have been slow to accept the idea that Impressionists’ audacious color combinations were unrelated to the scientific theories of France’s premier nineteenth-century authority on the subject. Roque hypothesized that the disparity between Chevreul’s advice to painters and the Impressionists’ uninhibited juxtaposition of complementary colors might be attributable to the fact that the artists paid less attention to the detail of the chemist’s text than its illustrations, which were published in a separate atlas.26 But it is also possible to take a broader view of the question. As Francastel himself pointed out in a much later publication, “It is not the physical fact of nature, as it were, that explains the development of Chevreul’s theory and Impressionism. Rather, it is the simultaneous recognition by artists and scientists of the importance of phenomena that were always perceptible but were to be discovered only by men who possessed a certain similar need and mental structures.”27 What was it, then, that at that particular moment in history attuned both scientists such as Chevreul and the Impressionists to the inherent variety and instability of color—the way its appearance changed according to the intensity of light or the color of the surface next to it?

FIGURE 25

Edgar Degas, Entrance of the Masked Dancers, ca. 1879. Pastel on gray wove paper. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass.

As we have seen, the research that led Chevreul to formulate the law of the simultaneous contrast of color was originally motivated by the particular problem of the vividness and permanence of dyes used at the Manufacture des Gobelins and the challenge of precisely identifying the ever-increasing number of colors produced by the national workshop and the private textile industry. From William Henry Perkin’s mauve to aniline black, this concern with vividness, variety, and the permanence of colors only became more pronounced with the introduction of synthetic dyes, emboldening in the process artists’ growing interest in color in all circumstances and facets of life. Indeed, too often overlooked in studies analyzing the influence of Chevreul’s color theory on late nineteenth-century French painting, the art and business of color chemistry played a central role in shaping Impressionists’ new ways of seeing and handling color.

Bright, Varied, Evanescent: Impressionism’s Chemical Aesthetic

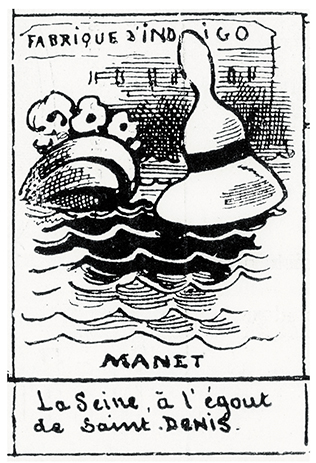

Comparisons between Impressionism and chemistry came mostly from the movement’s detractors. For example, Degas’s experimentation with diverse techniques—from oil painting and pastel to peinture à l’essence and aquatint—was described by one critic as an obsession with “chemistry,” as if instead of mastering his art, Degas sought to seduce clients with something tentative, cooked up in a makeshift studio laboratory.28 Meanwhile, Impressionists’ blues elicited comparisons to laundresses’ tubs, in particular the practice of laundry bluing, and to industrial waste dumped into the Seine by dye factories. In fact, the principal dye factory in Saint-Denis, the Fabrique de matières colorantes, A. Poirrier, later the Société anonyme des matières colorantes et produits chimiques de Saint Denis, was not a producer of indigo, as Hadol’s cartoon in figure 26 suggests, but rather one of the country’s earliest and probably largest manufacturers of aniline dyes. Lastly, the language of chemistry penetrated critics’ assessments of Impressionism, perhaps unwittingly, when they wrote about Impressionism as an art of “synthesis” rather than “analysis” or demanded that their works show greater “solidity,” a term commonly used to describe dyes’ ability to keep their colors, also known as fastness.29

FIGURE 26

Hadol, “Le salon comique,” L’Éclipse, May 30, 1875. Wood engraving. Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Detail.

But what exactly were the connections between the new nineteenth-century chemistry of dyeing and bleaching and Impressionist art? Or, to put it somewhat differently, how much of Degas’s “chemistry” translated into his depictions of materials used in fashion, including fabrics and laundry, which were also in the process of being radically transformed through industrial applications of color chemistry? Many of the paint pigments used by artists originated as by-products of the larger, more profitable dye industries.30 This was true not only of early aniline colors but also of madder, indigo, and even Prussian blue, which were used in the making of both paint pigments and dyes for several decades if not centuries. In other words, the crossover between dye and paint colors long predates the advent of aniline dyes.31

Much has been written about the influence of these brighter synthetic pigments—chromium yellow, artificial ultramarine, and emerald green, to name a few—on the development of Impressionism. “The works of the group’s main figures draw on a fairly consistent color range that is biased heavily toward the new materials, and it is these that tend to contribute the most striking effects in Impressionism’s radiant repertoire,” notes Philip Ball, for instance.32 But only some of the pigments featured in these accounts were actually the products of the new branch of organic synthetic chemistry that gave rise to aniline dyes and revolutionized the fashion industry. The brilliant red color featured in many of Renoir’s later paintings was generally produced from alizarin crimson, that is, a synthetic version of the natural dyestuff madder.33 In fact, discovered in 1868, synthetic alizarin was the first aniline dye that chemists purposefully developed to serve as an exact chemical replica of an already existing natural dyestuff. However, most of the other “synthetic” pigments employed by Impressionists and their contemporaries had no relation to aniline or later synthetic dyes that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Like cobalt blue, cadmium yellow, and viridian, the vast majority of them are inorganic pigments. Here, synthetic signals that these pigments are not found anywhere in nature but rather are wholly artificial products purposefully created by chemical reactions. Known in French as vert émeraude, viridian, for instance, bears absolutely no chemical relation to emeralds.

That both Impressionist and Academic painters employed synthetic colors undermines the idea of a direct causal connection between the use of certain pigments and a certain style of painting.34 Indeed, in the case of Degas, Renoir, Monet, and many of their friends, it was not so much the actual chemical composition of their materials—a combination of age-old natural pigments and newer synthetic ones, derived from both inorganic and organic sources—as their radically new way of handling color that suggested a familiarity with the new visual practices and understandings stemming from color chemistry. We have already seen how the introduction of the first aniline-based synthetic dyes in the late 1850s played a large part in the failure of Chevreul’s efforts to supply manufacturers with a universal system for the precise identification and classification of colors. Testifying to the sense of excitement and mystery that surrounded the development and commercialization of synthetic dyes, Alain Radau commented in La Revue des deux mondes in 1874, “Today the transition from natural to artificial colors is close to being a fait accompli, since it has been established that chemists can draw from the same barrel of tar all the colors of the richest palette, like a magician pours from the same bottle, according to your fancy, all the beverages you please to request.”35 Indeed, to many members of the general public, the process by which dark, viscous coal tar was transformed into brilliant colors must have seemed almost magical, akin to the inexhaustible-bottle trick performed by magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, which Radau was explicitly referencing, or the esoteric practices of early modern alchemists.36

Radau was not alone in drawing a connection between chemists’ transformation of otherwise useless coal tar into a variety of vibrant, valuable colors and alchemists’ fabled transmutation of base metals into gold. Popular-science writer Gaston Tissandier explained in his 1869 book titled simply La Houille (Coal tar), “How many alchemists in the Middle Ages sacrificed their long lives to sleepless nights and tiresome labors to transform lead and tin into gold and silver. . . . They ignored that, without looking for too long or too far, science would one day find everywhere the true philosopher’s stone; they were far from imagining that a simple piece of coal tar would be an inexhaustible source of riches.”37 In reality, the parallels between alchemy and the new branch of synthetic organic chemistry responsible for the explosion of aniline dyes were only superficial. As Tissandier himself acknowledged, the alchemy he described in his book was a distinctly modern one—one that, coupled with new, more reliable energy sources and the mechanization of manufacturing, generated profits unimaginable prior to industrialization.

Even among chemists, the variety of new colors successfully derived from aniline made a powerful impression. “The abundance, the variety of combinations is such that we do not know whether to be more amazed by their multiplicity or by the imagination required to name them. Indeed, it is by the thousands that dyers create, every season, new colors for their sample cards,” noted Paul Schützenberger in response to what he had seen at the 1878 Universal Exposition.38 Reporting from the 1889 Universal Exposition, Jules Persoz indeed confirmed, “Every day sees the emergence of newly created substances.”39

Accordingly, instead of trying to allure shoppers with one or two especially trendy colors with the help of attractive illustrations and seductive copy, retailers typically listed long inventories of shades, reinforcing the symbolic value of chromatic variety within modern consumer culture. Divided into nuances de villes and nuances claires, the list of fifty-two silk colors that appeared in the summer 1875 catalogue of the Grands Magasins du Louvre sent a clear message to women leafing through the publication: department stores can offer you more than smaller retailers do, and more is better (table 1). Displays inside the stores reinforced this message through the dazzling assortments of styles and patterns.

TABLE 1

Grands Magasins du Louvre catalogue, summer 1875, CC268, Catalogues commerciaux (CC), Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

| Nuances de ville | Nuances claires |

| Mordoré | Bleu azur |

| Marron | Bleu ciel |

| Loutre | Violette |

| Vigogne | Lilas |

| Beige | Gris perle |

| Chêne | Rose thé |

| Alouette | Rose vif |

| Havane | Cerise |

| Gris feutre | Ponceau |

| Gris sarde | Cardinal |

| Gris cendre | Turquoise |

| Gris russe | Chair |

| Mexico | Écru |

| Myrte | Vert Nil |

| Acier | Paille |

| Paon | Jonquille |

| Marine | Bouton d’or |

| Grenat | Crème |

| Bordeaux | Vert Suez |

| Solitaire | Fleur de pêche |

| Améthyste | Sphinx |

| Scabieuse | Ophélia |

| Airain | Sureau |

| Pain brûlé | Maïs |

| Bleu anglais | Blanc vif |

| Pervenche | Blanc mat |

For all the excitement generated by the variety and vivacity of women’s fashion, new synthetic dyes also garnered a large amount of negative publicity. In addition to possible ordering and inventory headaches, described by Edmond Bourdain in his Manuel du commerce des tissus (1885), dyes’ tendency to fade or turn caused many experts to withhold or qualify any endorsement, while others, adopting a more casual attitude, accepted the ephemerality of colors as a natural condition of modern consumer culture.40 Somewhere between these two positions, Chevreul was one of the first chemists to systematically test the solidity of dyes. His 1860 article “Notes sur les étoffes de soie teintes avec la fuchsine, et réflexions sur le commerce des étoffes des couleurs,” published only a year after Renard frères et Franc began manufacturing the new aniline-based dye, was the first of many interventions on the subject. “No other dyestuff is, to my knowledge, comparable to fuchsin in terms of its brilliance, intensity, and purity of color,” Chevreul wrote, echoing manufacturers’ enthusiastic statements about the new product.41 His praise for fuchsin mostly ended there, however, for as he quickly pointed out, the dye’s beauty was matched perhaps only by its evanescence. “If fuchsin has a rose’s brilliance,” he noted, “it [also] shares its fragility.”42 His tests, he insisted, left absolutely no doubt on this matter: “Four hours under the sun suffice for silk dyed with this substance to become appreciably dull, turn wine-colored, and then become reddish brown.”43

Aniline dyes, Chevreul warned, were completely unsuitable for wall coverings, upholstery, men’s fashion, and other textile goods intended for long-term use. He was greatly concerned, for example, that less conscientious furniture manufacturers would tarnish the country’s reputation for tastefully designed high-quality products by substituting traditional, more tested dyes for these newer ones. Women’s fashion, another French specialty, was an entirely different matter according to Chevreul. Rapidly changing trends in women’s fashion meant that dyes needed to last only a short time, he explained. And, in this case, French manufacturers could, and indeed should, produce flashy fabrics expected to last no more than a year or two. “That we use violet and purple silks dyed with this substance for ribbons, dresses, and other clothing items is absolutely natural,” he wrote, “but to introduce its use in the ornamentation of princely apartments is an irreparable mistake.”44

Chevreul was not alone in his worries. In the following decades, complaints about synthetic dyes’ lack of solidity multiplied, forming an anxious choir of voices that decried the untested nature and mutability of colors. At the Great London Exposition of 1862, official reporters already made clear note of aniline dyes’ lack of permanence. Hoping that chemists would soon find a solution to this problem, Charles Decaux observed, “This improvement would undoubtedly be more useful than [the dyes’] very discovery.”45 Five years later, at the Universal Exposition in Paris, reporters noted, “Considering the history of dyestuffs in general, it is reasonable to hope that this solidity problem will not take long to disappear, thanks to the combined efforts of science and industry.”46

Still, there was something extremely fitting about the fact that women’s fashion, known for its evanescence, depended on colors that were equally impermanent. As Radau remarked, the fugitive nature of these new synthetic colors was closely connected to the impermanence of modernity itself: “It’s a sign of the times that, in general, the buyer looks more for cheaply obtained brilliance than solidity; these fugitive colors, beautiful and quickly wilted like flowers that disappear after spring, respond to the public’s taste.”47 Indeed, despite Chevreul’s warnings, the Lyon Chamber of Commerce stressed that by producing brighter—if more fugitive—dyes, manufacturers were only answering consumers’ demands, as “consumers very often looked for brilliance over solidity in textiles for fashion and even textiles for furniture.”48

This same dynamic that centered on colors’ novelty, variety, and variations, including variations resulting from fading or turning of hues, also operated in the artworks of Degas, Renoir, and Monet. The three artists displayed a pronounced interest in fashion in all its forms of use and care, from dresses worthy of appearing in fashion magazines to piles of discarded garments provocatively inserted into paintings to remind viewers that they were looking at nude female models and not timeless mythological characters. Degas and Renoir paid particular attention to the creation and maintenance of garments and accessories; milliners and laundresses, caring for shirts and petticoats, appeared frequently in their paintings. In the context of a growing scholarly literature linking Impressionist painting and modern consumer culture, fashion especially, these paintings help us remember the old Marxist adage that behind every act of consumption lies an act of production.

That said, Degas, Renoir, and Monet could not have differed more in their ideas about art and, ultimately, in their responses to the challenges posed by chemists’ creation of a bright new world. While Degas was, as suggested earlier, a resourceful chemist, Renoir rejected the association, preferring to take nature and, eventually, early modern masters as his main points of reference. Contrary to Degas, therefore, who became more and more innovative in his later years from both formal and technical standpoints, Renoir anchored himself in preindustrial artistic traditions. Indeed, the rejection of modern technology, chemistry in particular, was one of the principal methods by which Renoir sought to establish himself as a serious artist. As such, in his paintings and his statements about art, Renoir echoed many common upper-class anxieties about chemistry’s role in creating an artificial, more vulgar society, in which appearances were seldom reliable.

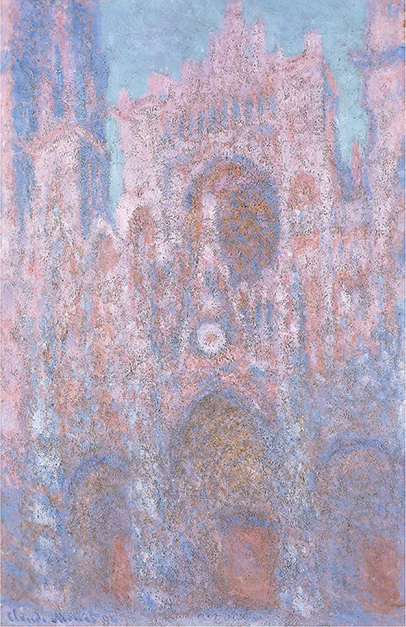

Monet’s engagement with fashion and modern color chemistry, more generally, is much harder to ascertain, not least because he produced far fewer figure paintings than his two longtime associates, Degas and Renoir. Only Alfred Sisley was as devoted a landscape painter. Treated by art historians as prime examples of Impressionism’s concern with bright outdoor light and evanescent atmospheric effects, if not Impressionism tout court, many of Monet’s paintings have at first glance at least relatively little to say about fashion. And, indeed, landscapes’ quickly changing appearances and the challenge of precisely capturing fleeting light and weather effects are the central themes of his letters and occasional public statements about his work. Thus, according to Monet’s own analysis, color existed first and foremost as the product of direct visual encounters with the motif at a specific moment, under specific light and weather conditions.

Yet, aside perhaps from Sisley, whose father was at one time director of a textile and artificial-flower manufacturing business, Monet is the Impressionist whose ties to the dye industry were the most immediate.49 Based in the textile-producing region of Rouen, Monet’s brother, Léon Monet, was a sales representative for the Swiss company Geigy, a major producer of artificial dyes.50 Monet, however, remained virtually silent about the multiple iconographic, formal, and chemical intersections between Impressionism and the vibrant colors of modern consumer culture that were his brother’s specialty. Indeed, unlike Degas, who embraced the artificial hues of popular commercial culture, and Renoir, who demonized them, Monet conspicuously steered clear of the subject altogether. The artist’s obsessive focus on sunlight and other atmospheric phenomena functioned, I believe, as a largely unconscious redirection of the stylistic and semiotic challenges posed by modern color. The three artists that concern me here developed, in short, highly personalized responses to the color revolution, which they represented and reshaped through their choice of subject matter, technique, and the final pictorial qualities of their artworks.

As noted earlier, this engagement with color chemistry was more than a matter of artists sometimes using pigments derived from aniline or the dye industry more generally. In fact, as Anthea Callen points out, Impressionists generally steered clear of larger, more commercial paint suppliers, such as Lefranc et cie: “Concerned about the permanence of their paintings, and having individual requirements regarding both colors, and paint consistency, the Impressionists avoided the uncertainties then associated with mass-produced paints. They chose instead to rely on personal recommendation and service, and colors freshly ground by hand.”51 In other words, Impressionists’ chemical aesthetic was mostly evidenced not in their choice of materials, but in their choice of subject matter, techniques, the formal characteristics of their artworks, and the way they wrote and spoke about them. Foregrounding color over line to an unprecedented degree, both formally and thematically, these innovations fundamentally tested the integrity of the visual sign, establishing in the process a broader and far more plastic definition of realism.

At the very beginning of their careers as artists, in the 1860s and early 1870s, Degas, Renoir, and Monet frequently depicted women in fashionable garments often dyed in vivid hues (figs. 27 and 28). In Renoir’s The Couple (ca. 1868), more than the emotional ties that unite the betrothed, it is the woman’s garish striped attire that immediately attracts viewers’ attention. Similarly, Monet’s first important success at the Salon, a painting titled Camille, or The Woman in a Green Dress, exhibited in 1866, showed the model’s richly colored dress to its best advantage (fig. 29). After seeing the painting, art critic Théodore Duret predicted that the young artist from Le Havre would soon enjoy “something like the career pursued by M. Carolus-Duran,” who was then building his reputation as a high-class portrait painter with a special talent for the depiction of richly colored silks, velvets, and other luxurious fabrics.52 Meanwhile, Degas was also attracting attention at the Salon with his portraits of women dressed in colorful garb. However, contrary to the positive buzz generated by Monet’s Camille, Degas’s Madame Camus (fig. 30), exhibited at the 1870 Salon, earned the artist practically nothing but censure. The painting, Edmond Duranty remarked, would “make the most wonderful frontispiece for Chevreul’s color treaty, that is all, to show how we vary tones, half-tones, quarter-and tenths of tones.”53 Keeping in mind the intended purpose of Chevreul’s color wheels, Duranty’s interpretation securely linked the painting to contemporary discourses on dyes, textiles, and chromatic variety; Degas would never again exhibit at the Salon.54

FIGURE 27

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Couple, ca. 1868. Oil on canvas. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum—Fondation Corboud, Cologne.

FIGURE 28

Edgar Degas, Portrait of Mme Edmondo de Morbilli, née Thérèse De Gas, 1869. Pastel on cardboard. Private collection.

FIGURE 29

Claude Monet, Camille, or The Woman in a Green Dress, 1866. Oil on canvas. Kunsthalle, Bremen.

FIGURE 30

Edgar Degas, Madame Camus, 1869–70. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

As Marie Simon highlights, one of the paradoxes of Impressionists’ avant-garde status resting on their depiction of contemporary fashions is that big-name painters who remained within the Academic mainstream, such as Carolus-Duran, James Tissot, and Alfred Stevens, also excelled in this department.55 Indeed, the most recent exhibition addressing the subject, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity (Musée d’Orsay, September 25, 2012–January 20, 2013; Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 26–May 27, 2013; Art Institute of Chicago, June 26–September 29, 2013), prominently featured several works by the members of “Maison Carolus-Duran,” as novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans dismissively referred to them, suggesting that the painters were more closely related to textile merchants or perhaps fashion designers à la Charles Worth than they were to bona fide artists.56 Eliding the important stylistic and sociological differences that separated this informal group of artists from the Impressionists, Gloria Groom, head curator of Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, challenged the age-old distinction between avant-garde and Academic art, insisting that “these artists represent not opposite camps but rather two sides of modernity connected by an interest in contemporary fashion.”57 And yet, important differences did undeniably separate the two groups and the artworks they produced. While Carolus-Duran, Stevens, Tissot, and their like, working in the tradition of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, accentuated the surface spectacle of fashionable color, Degas, Renoir, and Monet directed viewers’ attention to the sensory and semiotic novelties of the color revolution. They departed from the “couturiers-artists” who exhibited at the Salon not only in their collective polemical insistence that genre scenes, chronicling contemporary fashions, were just as worthy of artistic consideration as historical and mythological subjects, but also, perhaps even primarily, in their critical exploration of color’s role in shaping new modes of visual expression and signification. The end result was profoundly destabilizing, as indicated by early critics’ intensely hostile reactions to Impressionism. But there was also something historically apposite and deeply culturally resonant about these artworks: the bold coloring of Degas’s, Renoir’s, and Monet’s paintings was at one and the same time what most challenged the works’ legibility as art and most directly connected them to French men and women’s everyday visual experiences.

In focusing on the unusual brightness of Impressionists’ palettes, critics closely mirrored tastemakers’ complaints that women’s fashion had become overloaded and garish following the introduction of synthetic dyes.58 Like chemists responsible for this dramatic transformation of the dye, textile, and fashion industries, Degas and Renoir were credited with the “invention” of new colors. Impressed by what Huysmans called Degas’s “neologisms of color,” artists asked where the artist purchased his pastels and whether there was any secret to how he obtained his brilliant tones.59 Similarly, painter Albert André noted in his tribute to his mentor, Renoir, “He discovered reds and blues never seen before him.”60

Related to the notion that Impressionists had discovered, or invented, new colors was the hotly debated phenomenon of color trends in painting. In Impressions sur la peinture, originally published in 1886, Stevens highlighted, for instance, how artists frequently adopted a new hue simply because it was popular, only to move on to something newer and more eye-catching a few years later: “In France, fashion takes precedence over everything; even in painting, there are colors that are fashionable.”61 The popularity of certain colors, he observed, had nothing to do with subject matter or even a color’s inherent beauty—artists, too, were victims of fashion. Writing a few years later, artist Jehan Georges Vibert made a similar point: “Supplied with cheap rubbish made for hobbyists and no longer having to concern himself with materials, the modern artist surrenders himself to every one of his fantasies. He paints willy-nilly, without thinking of tomorrow, having no other preoccupation than to follow fashion—because fashion [too] is involved! Certain exquisite tonalities are absolute musts, akin to the way one must have agate-like flesh, marble-like transparencies, muted mattnesses [matités sourdes], crepuscular shadows, etc. We undersupply; there isn’t enough; journalists ask for it!”62

Originally published in 1891, but based on research Vibert conducted decades earlier, La Science de la peinture aimed to educate artists about the composition and durability of paints. In the book, Vibert castigated his fellow painters for their readiness to jump on the newest chromatic trend pedaled by color merchants in Montmartre with little consideration for the longevity of their works and their legacies as artists: “Today the painters . . . no longer deigning to preoccupy themselves with the material aspects of art, abandon the task of preparing their canvases and colors to [pigment] grinders that come down from the mountains in hordes . . . let’s not say which mountains to avoid offending someone!”63 As a result of this loss of technical knowledge, Vibert suggested, the quality of paints and other artists’ materials had declined significantly, to the point that it was no longer uncommon for artists to witness firsthand the deterioration of their works.

Avant-garde artists were not the only ones targeted by Vibert’s criticisms; Academic artists were just as likely to use poor-quality materials.64 Still, because of the startling novelty of Impressionists’ color palettes and techniques, as well as, perhaps, the thematic importance of fashion in their oeuvre, some writers singled them out for special reprimand. The term indigomania, for example, which critics used to describe Impressionists’ seemingly irrational passion for blues and violets, not only carried with it certain psychological and medical implications—Huysmans originally described Impressionists’ indigomania as a bizarre form of color blindness brought on by mental illness—but also referenced the culture of intense, short-lived fads. Coined at the turn of the fourteenth century, the term mania originally had the same meaning as madness or insanity. By the nineteenth century, this definition had mostly receded into the background, however; instead of literal madness, the French manie typically referred to the collective—largely metaphorical—madness of modern life. Commonly used as a suffix, as in daguerréotypomanie, statuomanie, affichomanie, and décalcomanie, the word called attention to intense, generally irrational, collective passions. It is hardly surprising, then, that critics alluded to fashion and its evanescent color trends when discussing Impressionists’ color choices. Indigomania was not so much a physiological phenomenon as a social and economic one born of modern consumer culture.

Armand Silvestre introduced the idea that the Impressionists were responsible for the new-found popularity of bright colors among artists, probably before there was any real evidence of Degas, Renoir, Monet, and their friends influencing others’ color choices. In his review of the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876, Silvestre noted, for instance, “[The Impressionist school] developed plein-air painting to a level unknown until then; she made fashionable a range of singularly light and charming colors; she looked for new connections.”65 For Silvestre, this was all very positive. Yet the notion that the Impressionists were responsible for starting a new trend in art could also be used against them. First and foremost associated with the feminized, overtly commercialized world of fashion, color trends lay outside the realm of art proper. Like Huysmans’s pointed references to the “Maison Carolus-Duran,” talk of Impressionist color as a “mere” fashion had the potential to undermine the seriousness of the group’s artistic enterprise.

Rather than challenge this negative view of Impressionists’ turn toward bright colors, statements by artists oftentimes involuntarily reinforced it. “I’ve finally discovered the true color of the atmosphere. It’s violet. Plein-air is violet. . . . In three years from now, everyone will be painting violet!” Manet told his friends, after adopting the Impressionists’ lighter, brighter palette in the 1870s.66 Significantly, in this and other statements made by Manet on the subject, the reasons for coming over to the Impressionists’ side remain obscure, suggesting that the artist cared little about the scientific arguments advanced by Duret, Laforgue, and others in defense of Impressionists’ unconventional use of the color. “One year one paints violet and people scream, and the following year every one paints a great deal more violet,” Manet remarked on a different occasion.67 Endlessly repeated and multiplied, scientific justifications aimed at convincing the public of Impressionists’ strong commitment to optical realism did not cohere with the rest of what people said and wrote about the paintings, not to mention the public’s experience of them. In the end, the overwhelming victory of blue and violet in Impressionist art seems to have had preciously little rhyme or reason to it. De Lostalot remarked, for example, about paintings by Monet on show at the Durand-Ruel gallery in 1883, “Those who like this color will be satisfied: Mr. Monet has created for them an exquisite symphony in violet.”68 Was the public’s reaction to Monet’s paintings dictated solely by personal color preference? Why and to whom did it matter, then, if the violet was the negative after-image effect of yellow sunlight or the result of Monet’s reputed ability to perceive ultraviolet rays, as de Lostalot observed elsewhere in the review?

Degas’s, Renoir’s, and Monet’s treatments of color were never aimed at achieving the perfect trompe l’oeil effect. Indeed, as a movement, Impressionism was as much, if not more, about critically analyzing the experience of looking than it was about capturing the surface appearance of reality at a given moment.69 More precisely, in their obsessive observation of color, both as it appeared in fabrics and in nature, Impressionists closely paralleled the intensely visual scientific practices of chemists, captured in a variety of contemporaneous sources. Scientific reports announcing the invention of a new dye often included lengthy descriptions of chromatic metamorphoses involved in the production process. A report in the Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des sciences, for example, explained how, in the process of creating a bright pink dye, a chemist witnessed a myriad of transformations. His black aniline dye turned first green and then blue, then red-violet to yellow, and, finally, light gray to fluorescent pink.70 Described in detail in the article, these chromatic metamorphoses indicated real and significant changes in the chemical composition of the solution. Chemists thus learned to identify, compare, and evaluate the meaning of the subtlest variations in hue. Vision, color vision in particular, played a central role in the production and dissemination of nineteenth-century scientific chemical knowledge.71

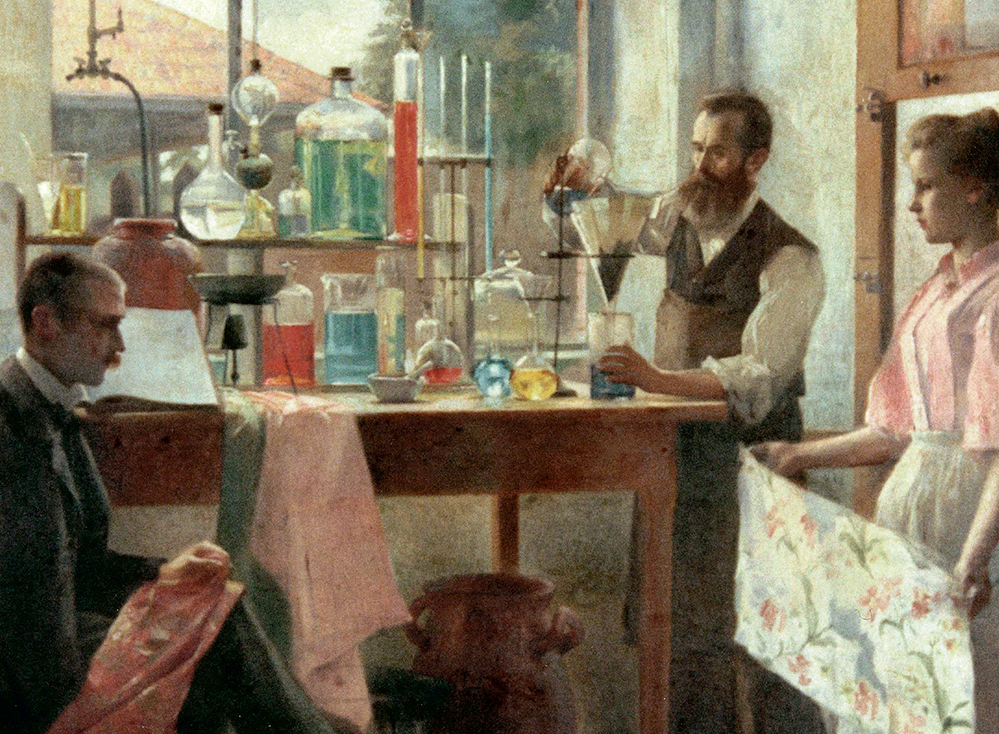

Executed in 1898–99, Marie-Augustin Zwiller’s L’Industrie en Alsace: Le Laboratoire, confirms the central role of vision in industrial chemistry (fig. 31). A collection of beakers, tubes, and bottles filled with chemical substances in an assortment of colors occupies the center of the painting. The window, translucent colors of the liquids, and chemical glassware contribute to the airy beauty of the scene. An industrial chemist standing to the immediate right of the table pours a bright blue liquid into a filter. Neatly organized, bathed in light, and open to the outdoors, this is not the dark, secret laboratory associated with the quintessentially nineteenth-century figure of the mad scientist. Illustrating the connection between small-scale chemical experiments and the continued productiveness of the Alsatian textile industry, the painting’s middle ground features a second male figure examining a finished piece of fabric, presented to him by an attractive female assistant.72 Her pink blouse subtly identifies her as a potential consumer of the goods produced by the firm. Yet Zwiller does not give any hint of women’s own color expertise; the female figure’s gaze is obediently directed toward her employer’s face instead of toward the dyes and textiles whose colors she will later be called to assess in the marketplace.

FIGURE 31

Marie-Augustin Zwiller, L’Industrie en Alsace: Le Laboratoire, 1898–99. Location unknown.

In the end, it is probably in their way of looking at color, as a subtly variegated collection of temporary visual experiences, that Degas, Renoir, Monet, and other Impressionists most closely aligned themselves with Chevreul and, more generally, color chemistry. “An essential dimension of chemistry is visual perception, of a lovely color or, much more important, of a change in color, in the aspect of a given preparation,” writes philosopher of chemistry Pierre Laszlo.73 Impressionists’ paintings intersected with color chemistry not only through their depiction of up-to-the-minute women’s fashion and artists’ materials but also in the way the paintings registered the modern experience of looking at color. Degas, Renoir, and Monet shared chemists’ intentional, almost obsessive, attention to color, in particular its multiple varieties and variations in modern material and visual culture.

Chemistry and Craft: The Cases of Degas and Renoir

Degas’s way of looking at color is well documented in his sketchbooks.74 In certain instances, as in the sketch pictured in figure 32, completed in preparation for Miss Lala au Cirque Fernando (1879), Degas noted on the drawing itself the color of certain elements of the scene. The image is divided into multiple static surfaces of color: the underside of the arch is labeled “garnet-colored”; and the semicircular surface below the vaulted molding, “plain blue green.” In addition to this shorthand, employed by other Academically trained artists, Degas recorded his chromatic impressions in brief, matter-of-fact statements and longer narrative passages. “I will never forget the pearly gray of the trees and the dark and powerful green,” he wrote in another sketchbook, highlighting, by opposition, the intrinsically immaterial and fleeting nature of chromatic impressions.75 Indeed, large sections of the artist’s sketchbooks were reserved for the purpose of committing to memory that which by its very nature resisted easy transcription into paint, pastel, and watercolor, much less translation into language.

FIGURE 32

Edgar Degas, Sketch of the Cirque Fernando, in Sketchbook no. 23, n.d. Drawing. Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Degas described women’s garments with the same degree of attention. “White muslin dress with bow [sic] on the shoulders and large belt dark lilac” is how he described the attire of a certain Mademoiselle de Borderieux in Sketchbook no. 1.76 Elsewhere in the same sketchbook, Degas provided more contextual detail, noting the place and time of the scene. But, here too, his focus remained fixed on women’s fashion: “Carriage coming back from the woods at 6 o’clock. On the pont de la Concorde, 2 women. A hat made of gray straw. Like sloe, with a light blue feather. The other straw hat, burnt and golden café au lait with a gray feather.”77 As suggested by these and other color notes in the sketchbooks, Degas was also attentive to the colors of the natural environment. He seems, however, to have drawn little distinction between the colors of natural elements and artificial commodities, such as dresses, ribbons, and hats. The two were, in any case, recorded similarly in his sketchbooks.

Degas claimed to value drawing above all else and allegedly would have stuck to black and white “if the world had not clamored for more and yet more of those vivid pastels.”78 Reinforcing the long-standing opposition between line and color, art historians have traditionally interpreted these types of declarations by Degas as evidence of his divergence from the other Impressionists, something already noted by critics at the time. Speaking of Degas, Zola observed, “He is first and foremost a draftsman, at one and the same time meticulous and original, who has produced very remarkable series of laundresses, dancers, women washing themselves, whose movements he has drawn with elegant truthfulness.”79 Indeed, when compared to the broadly painted landscapes of Monet and the soft-edged figures of Renoir, it is hardly surprising that Degas’s paintings and pastels struck critics as belonging to an entirely different school. Moreover, Degas never subscribed to the plein air mode of Impressionism personified by Monet. “[Degas] was out of sympathy with the blond scheme of the luminists and Cézanne’s struggle to force color to express formal values left him cold,” Ambroise Vollard noted.80

However, as Degas’s drawings and hastily written notes—sometimes mere color names floating in the blank space of the page—confirm, the artist was, in fact, very interested in color. Many of the subjects he explored—from the ballet, with its brightly colored costumes, to the racetrack, where jockeys’ circus-colored uniforms contrast sharply against the brown and green background—offered strategic opportunities to explore color’s modes of appeal and signification. Degas’s closely cropped Jockeys (ca. 1882) is as bright and colorful as anything produced by Renoir, Monet, or any other Impressionist at the time (fig. 33). Georges Rivière reflected, “He willingly admitted that color was secondary in art. [But] I believe that we shouldn’t attach more importance than necessary to this opinion, often articulated by Degas; after all, it was mostly formulated to annoy certain artists, notably Manet and Renoir . . . we shouldn’t forget that he admired Delacroix.”81 Indeed, Degas seems to have taken profound pleasure in misdirecting, if not provoking, his acquaintances. “White and black are sufficient to create a masterpiece,” Degas told all who would listen.82 And yet, as Rivière emphasized, these statements came from a “passionate researcher of color-engraving processes” who produced some of the most brilliant pastels ever seen.83

FIGURE 33

Edgar Degas, The Jockeys, ca. 1882. Oil on canvas. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

Huysmans, in any case, remained unfazed by Degas’s statements, aimed at reinforcing the long-standing supremacy of drawing over color. Considering the works he exhibited at the fifth Impressionist exhibition in 1880, the novelist declared, “No painter since Delacroix . . . has understood like Mr. Degas the marriage and adultery of colors; no one currently has as precise and generous a [style of] drawing, as delicate a chromatic touch [fleur de coloris]; no one has translated into a different art the exquisiteness that the Goncourt brothers put into their prose; no one has fixed in the same way, simultaneously deliberate and personal, the most ephemeral of sensations, the most fugitive of subtleties and nuances.”84 Degas’s paintings and pastels, not to mention his wax sculpture of a fourteen-year-old ballerina, exhibited on the same occasion, told a very different story about the artist’s relationship to color and, more broadly, Impressionism’s relationship to realism.

Degas’s desire to “fix” the colors of the scenes he observed, using sometimes only pencil and paper, gains particular relevance in the context of other information in the sketchbooks, namely projects and recipes detailing different materials and technical processes, including the relatively uncommon intaglio printing process known as aquatint. Indeed, as Theodore Reff has convincingly demonstrated, there was in Degas “something of an amateur scientist and inventor,” motivated in part “by the technical as an end in itself.”85 In aquatint as well as photography, in which we know Degas took great interest in the 1890s, fixing plays a particularly important role. Achieved through chemical means in a manner similar, both materially and metaphorically, to the fixing of dyes on fabrics, fixing is what establishes the tone of the print or photograph. From his letters, we know that Degas developed his photographs himself and that the merchant who usually provided him with photographic materials also sold artists’ colors.86 Finally, it is also telling that Degas described the process of creating a picture as a “series of operations,” an expression more commonly associated with the work done in laboratories than artists’ studios.87

Degas’s colorism involved a large measure of experimentation, but it was far from haphazard. Starting with his mostly specious claim that he would have happily restricted himself to black and white “if the world had not clamored for more and yet more of those vivid pastels,” we see how color was intimately linked in Degas’s mind to consumer desire. The art market, he hinted, was not in the end so different from ordinary retail shops, selling women’s garments and fashionable household items. Indeed, the visual appeal of department stores, centered on the multiplication of patterns, textures, and colors, seems to have struck a particular chord with Degas, who reputedly told the publisher of Zola’s classic department store novel, Au Bonheur des dames (1883), that the book would have been better illustrated with fabric samples, such as those that often appeared in catalogues.88 One of the most important aspects of Zola’s novel, Degas thus suggested, was not the romantic twists and turns of the protagonist’s story but rather the atmosphere of chromatic variety and material abundance skillfully re-created by the author.

Moreover, in his letters, Degas ironically referred to his artworks as “mes articles”—articles of trade—suggesting a parallel between colorful works of art and the variegated goods for sale in department stores. Executed over thirty years, Degas’s paintings and pastels of ballerinas, whose titles specifically draw attention to variations in color—Danseuses jaunes (1874–76), Danseuses basculant (Danseuses vertes) (ca. 1880), Danseuses, vertes et roses (1890), Danseuses bleues (ca. 1890), Trois Danseuses en jupes saumon (1904–5), and so on—create the impression of a well-stocked fabrics department. Indeed, as Degas himself confessed about his ballerina works, “My chief interest in dancers lies in rendering movement and painting pretty clothes.”89

When juxtaposed with his depictions of ballerinas and brightly clad women from the social elite, Degas’s representation of laundresses—more than a reinterpretation of a classic subject treated by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Camille Corot, and Honoré Daumier—can easily be read as a reflection on the variety and evanescence of color in modern visual and material culture. As art historians have noted, significant differences exist between Degas’s depictions of laundresses, ironers included, and contemporaneous representations by artists and photographers, which typically emphasized laundresses’ sexual appeal.90 Indeed, like shopgirls, waitresses, and public entertainers of all kinds, laundresses belonged to that category of nineteenth-century women whose profession, involving independent movement through the city and frequent interactions with members of the opposite sex, made them immediately suspect to members of the bourgeoisie. Degas’s paintings, however, generally eschew the stereotype.

Executed in or around 1869, the artist’s first important work depicting a laundress is remarkably chaste compared to contemporary popular representations (fig. 34). The neckline of her blouse, for example, does not reveal any part of her shoulders, despite the suffocating heat and steam of the shop, which led so many other laundresses to disrobe, to the apparent delight of casual and not-so-casual passersby. Like the majority of Degas’s twenty-seven works on the theme of laundry, not including images in sketchbooks, the painting depicts, more specifically, an ironer, who at the time typically enjoyed a slightly better social and economic position than simple washerwomen.91 Degas, however, made little distinction between them in the artworks, and both types are equally important for understanding the relationship between Impressionism and the new interpretation of color that emerged following the introduction of synthetic dyes.

FIGURE 34

Edgar Degas, Woman Ironing, ca. 1869. Oil on canvas. Neue Pinakothek, Berlin.

The majority of Degas’s drawings and paintings in this extended series were completed between the mid-1870s and the mid-1880s, when Impressionism was at its height. At the second Impressionist exhibition, held in 1876, Degas showed five works depicting laundresses. Among these was the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s A Woman Ironing (1873), which features a laundress against strong backlighting (fig. 35). Described in the catalogue for the show as a “silhouette,” the painting supplies only the most general information about the laundress’s appearance. Notably, the artist makes no effort to render her skin or hair in a sexually appealing way. Instead, the laundress’s dark tones cut a sharp outline against the hanging laundry in the background, placing the entire emphasis on the shape and position of her body. Indeed, as Edmond de Goncourt chronicled in a journal entry, Degas took a deep interest in ironers’ unique choreography of movements: “Degas puts before our eyes laundresses, [and more] laundresses, all the while speaking their language and explaining to us the technicalities of the downward pressing and circular strokes of the iron, etc. etc.”92 Pointing to de Goncourt’s testimony, among other sources, scholarly studies considering A Woman Ironing (1873) and the artist’s other early paintings of laundresses have generally identified drawing and the rendering of movement as his primary focus.

FIGURE 35

Edgar Degas, A Woman Ironing, 1873. Oil on canvas. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As time went on, however, the detail and coloring of Degas’s depictions of laundresses became more varied and precise. He began a larger version of this same painting in 1876 (fig. 36). Completed eleven years later, in 1887, the painting, like the earlier one, shows a laundress expertly wielding a hot iron before a curtain of hanging laundry. Compared to the earlier painting, though, the scene is much more clearly rendered. Sunlight softly illuminates the laundress’s chin and brow. The polkadot pattern of her blouse adds to the realism of the scene, whose simplified forms, painted in muted tones, might otherwise have produced a static, decorative effect.

FIGURE 36

Edgar Degas, Woman Ironing, begun ca. 1876, completed ca. 1887. Oil on canvas. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Moreover, contrary to most nineteenth-century paintings of laundry and laundresses, the later work clearly features a variety of colored garments. As such, it provides a much more accurate depiction of the use, care, and circulation of clothing. For, indeed, while owners of garments made of expensive silks or woolens took the greatest precautions to avoid washing them and, if washing could not be avoided, generally sent their items to high-end dégraisseurs-teinturiers, most everyday garments, whatever their color, fell under the care of ordinary laundresses. The bulk of their business consisted of whitening whites. However, as Zola documented in his research notes for his 1870s novel L’Assommoir, set in the world of Parisian laundresses, colored items of clothing were not unusual; “sort, color, and white” was laundresses’ first order of business, the author remarked.93

Degas’s detailed knowledge of ironers’ tools and movements struck Edmond de Goncourt as unusual and, probably, a little absurd. But the critic and writer did not wholly dislike the artist’s paintings of laundresses, which he praised as “the most charming pretext for blonde and tender colors.” De Goncourt was here describing Degas’s earlier paintings, whose “skin-pinks” and “laundry-whites” also greatly appealed to him.94 But the statement also applies to the 1876–87 painting; the translucent muted tones of the laundry are among its most striking features. How many more washes would the garments be able to withstand before they faded to white? The question is not as trivial as it might seem. For it is important to remember that washing and sunlight both had an extremely harmful effect on synthetic dye colors. Writing in 1883, Charles Decaux’s statements on the subject clearly indicate the modesty of chemistry’s progress in this area to that point: “The colors fixed onto fabric should resist as much as possible the atmospheric effects of daylight and the sun, air, water, and occasional washings.”95 More than simply muted or tender, the colors of the garments and the painting, more generally, appear fragile, and washed out.

Between 1884 and 1886, Degas worked on his best-known painting of laundresses, Women Ironing, now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay (fig. 37). As in the 1876–87 painting, the colors are relatively muted, despite the absence of any clearly discernible source of light. Pink from the blouse of the ironer on the right appears to have migrated onto her coworker’s yellow scarf and right arm. The aprons they both wear are messes of blue, pink, and gray specks. Certainly, dyeing and painting are significantly different from one another: dyes are soluble and form a chemical bond with the fabric, while paint pigments are generally insoluble and, combined with a binder, are applied to the surface of a panel or canvas. The coarse, unprepared canvas of Degas’s 1884–86 work, however, which is clearly visible through the thin layers of paint, heightens the textile quality of the painting. Thinly applied, the paint does not cover the entire surface of the canvas, as if to further emphasize the fragility of the bond linking the colored medium to its support.

FIGURE 37

Edgar Degas, Women Ironing, ca. 1884–86. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

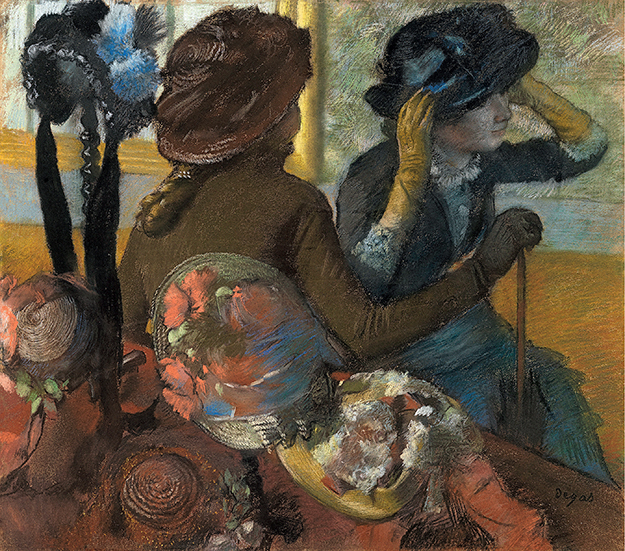

Along with washerwomen and ironers, milliners are another recurring subject in Degas’s work. Like artificial-flower makers, whose products played a central role in hat making, milliners enjoyed a relatively privileged position in the Parisian working-class hierarchy. Contrary to laundresses’ work, millinery was a highly skilled trade in the nineteenth century, requiring a good eye for colors and shapes as well as great technical ability. As Eunice Lipton notes, “Because hats were considered the crowning touch to a carefully arranged ensemble, milliners often perceived themselves as artists.”96

Executed over three decades, Degas’s paintings have generally been considered in the context of the sexual economy of nineteenth-century Paris, in particular the practice of clandestine prostitution. More recently, Ruth Iskin has interpreted Degas’s paintings of milliners as nuanced commentaries on Parisian consumer culture; the artist’s interpretation of gender and class plays an especially important role in her analysis.97 As I want to emphasize here, however, the detailed analysis of the paintings’ formal characteristics, color in particular, does not eliminate the possibility of a thoroughly historical understanding of Parisian consumer culture attentive to gender and other important economic and social issues. For there is, in the end, no such thing as a purely formal interpretation of color.

As the palette of women’s fashion gradually darkened during the fin de siècle, the artificial flowers, feathers, and ribbons that decorated women’s hats became one of the last refuges for the bright, unstable, and patently artificial colors popular during the Second Empire and first years of the Third Republic. The “magnificent bouquet of pink roses at the Exhibition” had in the matter of “a few weeks under diffuse light lost the dazzling beauty of its color and turned a livid hue,” Decaux observed.98 Industry experts were not the only ones to note the rapid deterioration of artificial flowers’ bright colors. In his Le Mécanisme de la vie moderne, historian Georges d’Avenel pointed out that during their transport from Paris and London, blue bindweeds and morning glories often turned green en route: “Even a worker afflicted with bad breath, or who routinely ate garlic, would have a negative influence on the color of the finery and garlands that she must manipulate.”99

Degas’s central preoccupation with women’s hats as a vehicle for the bright, varied, and evanescent hues of modern consumer culture is evident not only in the artworks’ palettes but also in the artist’s choice of materials, technique, and compositional strategies. In many of Degas’s artworks, namely Little Milliners (1882) and At the Milliner’s (1882), hats are situated front and center (figs. 38 and 39). In the latter, the artist uses a high viewpoint, amplifying the voyeuristic quality of the work. But whatever curiosity viewers might have entertained toward these women, perhaps sexual in nature, is undercut by the violent sectioning and concealment of their bodies by hats, stands, and tables. In the end, there is little doubt as to where the viewer is meant to focus his or her attention.

FIGURE 38

Edgar Degas, Little Milliners, 1882. Pastel on paper. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo. Purchase: acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor, F79-34.

FIGURE 39

Edgar Degas, At the Milliner’s, 1882. Pastel on paper. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

The Millinery Shop (1879–86) and The Milliners (ca. 1882–1905) stand out as the only two representations of millinery shops executed by Degas in oil on canvas (figs. 40 and 41). Carefully organized onto stands, the elegant hats in The Millinery Shop form a modern still life, expressly composed to elicit consumer appetites. By representing several models of hats, Degas highlighted the originality and variety inherent in milliners’ work, as opposed to its more repetitive and standardized aspects. Even the most prestigious high-end milliner produced several replicas of the same hat. In Degas’s painting, by contrast, the similarities between the hat with the yellow ribbon, perched on a stand, and the one with blue ribbon, resting on the table, draw attention to the importance of chromatic variety in nineteenth-century consumer culture.

FIGURE 40

Edgar Degas, The Millinery Shop, 1879–86. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago, Ill.

FIGURE 41

Edgar Degas, The Milliners, ca. 1882–before 1905. Oil on canvas. Getty Art Institute, Los Angeles, Calif. Courtesy of the Getty Art Institute, Los Angeles, Calif.

Yet, contrary to the dye and fashion industries, which encouraged consumers to appreciate the most subtle chromatic variations—insisting that differences between tabac-turc and painbrûlé, vert-paon and vert-olive, gris-acier and gristourterelle, martin-pêcheur and eau-de-mer, and so on were significant and meaningful—Degas privileged basic color types to get his message across. It is easy to imagine shoppers referring to the hats by their dominant color: the red hat at the top left of the canvas, the green one to the right, the blue one on the table, the yellow one to the left. Degas adopts the same approach in The Milliners (ca. 1882–1905), where the rainbow of ribbons in bright primary and secondary colors is clearly the most salient feature. Like a simplified color wheel, a rainbow, or, indeed, a painter’s palette, this assemblage of colors did not merely exemplify but also concretely thematized the modern experience of color.

Art historians have frequently drawn attention to the ambiguous social identity of the central figure of The Millinery Shop. Usual markers of social class, such as dress, posture, and facial features, they explain, do not add up in the expected manner, making it difficult to determine with absolute certainty whether the seated figure is a milliner or a bourgeois woman shopping.100

Degas’s treatment of color, I suggest, imparts a similar sort of uncertainty to material objects in the painting, from the milliner’s (or shopper’s) dress to the straw-colored hat that seems to hover over her head. The red exceeds the lightly traced outline of the capote, spilling onto the blue wall behind it. Meanwhile, this same bonnet’s long red ties seem to bleed into the table, suggesting something of the fragility and still-mysterious nature of synthetic dyes. The wide green ties of the straw-colored hat, adorned with white and pink artificial flowers, are strangely devoid of definition. Subtle modulations in the saturation and hue of the green ribbon resist easy reading as folds or shadows, imparting a cheap flatness to the accessory prominently featured at the center of the painting.

Composed almost entirely of powdered pigment, pastel produces especially bright colors, and it is fitting that Degas completed the bulk of his millinery works using this medium. When several of his pastels were shown in 1886 at the last Impressionist exhibition, including At the Milliner’s (1882) (fig. 42), art critic Félix Fénéon observed, “His color has an artificial and personal mastery: he has shown this in the turbulent color-schemes of jockeys and in the splendor of theatre decor: now he demonstrates in muted, seemingly hidden effects, for which the pretext is a shock of ginger hair, the violet folds of wet linen, the pink of a lost cloak, the acrobatic iridescence around the edge of a bowl.”101 Indeed, starting in the 1880s, Degas became increasingly innovative in his use of materials and technique. He often combined pastel with other media, such as gouache and watercolor, and achieved extremely unexpected color effects through layering. It is not surprising that, as Degas’s style evolved to become simultaneously more technically innovative and brashly colorful, he would revisit the theme of the milliner. In the 1905–10 pastel At the Millinery Shop, he clearly evokes the instability of color—that of the feathers and artificial flowers—with his multiple visible hatch marks (fig. 43).

FIGURE 42

Edgar Degas, At the Milliner’s, 1882. Pastel on pale gray wove paper, laid down on silk bolting. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, N.Y.

FIGURE 43

Edgar Degas, At the Millinery Shop, ca. 1905–10. Pastel. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.