1

Why Is It So Hard to Get Rich?

THE FIRE SALE

As the Fortune 500 electronics retailer Circuit City staggered toward financial collapse, the vultures circled. Carlos Slim, a Mexican billionaire, made a lowball offer. Another Mexican billionaire, Ricardo Salinas, might have bought the ailing firm, but ran into trouble with U.S. regulators. A hedge fund was also interested, and a private equity firm. Blockbuster, in a desperate attempt to leap out of its own shrinking pond, contemplated a bid. But in the end, the winning offer to buy Circuit City came from a consortium led by Great American Group, a liquidation firm. It paid $900 million for a company that had been valued at more than $44 billion only a few years before. What Great American really wanted was the inventory. It was planning a fire sale.

Within twenty-four hours, the sale had begun. A crowd of about fifty gathered expectantly outside the Circuit City store on New York’s Upper West Side before opening hours on January 18, 2009. A security consultant who specialized in liquidation sales explained: “You have to control it before they start lining up. You also need somebody to talk to these people while they’re in line, because if there’s nobody to guide or talk to them, it becomes a mob.” (Only two months before, New York shoppers had trampled and killed a Walmart employee who was standing between them and some heavily discounted items.) “Entire Store on Sale!” and “Nothing Held Back!” proclaimed the banners above another Circuit City in midtown Manhattan, further inflaming the shoppers’ desire.

But as the mob burst through the doors and fanned out into the aisles, it was soon clear that something was wrong. Hungry packs formed and then dissipated. The nervous energy of the crowd began to ebb. Eventually, coming down from their predatory rush, bored shoppers began to talk to the assembled media. “We came prepared to throw elbows,” said one, “but there’s not much on sale.” Most items were discounted by a mere 10 percent. “As far as all this high-end stuff,” said another shopper, “you can still probably find better [deals] online.” The liquidation sale was “a scam,” complained the technology bloggers later. The CEO of Hudson Capital Partners, one member of the liquidation consortium, attempted to justify the meager discounts: “How often do you see iPods at 10 percent off?” Similarly, a Circuit City employee commented, rather unsympathetically, “We had one customer buy something only to return it 20 minutes later saying that he got ripped off and it was cheaper at Best Buy. Now while that was true, there are signs that say ‘no returns’ ALL OVER THE STORE.”

As the weeks wore on, though, the deals got better. By early March, bloggers were proclaiming the prices on software ($45 for Microsoft Office at one California store, for example) “a steal.” Sections of most stores nationwide had been emptied and closed off with yellow tape. The TVs, at 40 percent off, were vanishing quickly. At another California branch, everything was up for grabs, including furniture from offices, half-empty cans of cleaning products, and a notice board that read “Cleaning fairy fired! Please clean up after yourself” (this latter item was optimistically priced at $5). At many stores, a descent into anarchy had begun, with one manager complaining that his employees had stolen nearly $400,000 worth of items in less than a week. A reporter from the Guardian wandered into a New York Circuit City to find that a “bearded, eccentric-looking” man had taken over the public address system, yelling repeatedly: “Buy American! If you’re going to buy, buy American!” This being America, Circuit City retail employees discovered that their health insurance would be terminated within just a couple of months of the fire sale. The Guardian reporter stumbled across a laid-off worker who had been living in a homeless shelter for three months. Like any good New Yorker, his main concern was his failure to keep up appearances. “I’m a Rutgers University graduate,” he said. “This is embarrassing.”

The end finally came on March 9. By this point, the selection was limited but the discounts were extraordinary, so the buying frenzy continued. “I saw a guy with bins and bins of the first season of Desperate Housewives. I don’t know what he’s going to do with all those,” said one shopper, leaving one plundered Circuit City in suburban Los Angeles to head to another. At 1 p.m. in another California store, a manager announced that everything would be 50 percent off for twenty minutes. At 4 p.m., the liquidation company’s representative started filling shopping carts with random items, announcing “Whole cart for $1!” to anyone who would listen. Before long, nearly everything of value was gone. The following day the California employees assembled for one last time, to clean up. They watched a tape of one of the managers appearing on the television program Divorce Court. They played football in the empty store. They said their goodbyes, and left.

When most people think about wealth secrets, they probably think about some kind of business venture. The fall of Circuit City and another famous failure, the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management, illustrate why business, when practiced in the absence of wealth secrets, produces fire sales more often than fortunes.

THE NAPOLEON OF RETAIL

The company that became Circuit City was founded as Wards by Sam Wurtzel. Wurtzel was ambitious, clever, had married well, and was casting about for a new business idea after a venture with his wealthy father-in-law had failed. He was also something of a budding Napoleon of retail. When he saw territory, he longed to conquer it. And like Napoleon, he wanted to keep his empire all in the family. The name “Wards” was based on his family’s initials—the Wurtzels, made up of Alan, Ruth (his wife), David, and, of course, Sam.

On holiday in Virginia in the early 1950s, Wurtzel was having a shave at a barbershop when he overheard that the first television broadcast station in the South was about to start in Richmond. Broadcasts would last only a few hours each day, consisting of whatever took the proprietor’s fancy. No matter: up to that moment, there had been no TV signal at all anywhere in the area, so the broadcast would increase demand for television sets. Inspired, Wurtzel sold his home in New York and eventually, in 1952, opened Wards, a retail operation selling televisions in downtown Richmond.

Initially, Wurtzel and his business partners at Wards did not have much in the way of wealth secrets—which, as we shall discover, is the case for most small businesses. Other people heard about the new station and opened their own TV stores, so Wards had to make its money by hook or by crook. (Napoleon would have approved. He once said: “The surest way to remain poor is to be an honest man.”) Wards salespeople attempted to charge each customer the highest possible price for every television sold (price tags on each set were written using a code only employees could read). The company also practiced what it called “step-up selling,” luring in customers with cheap offers and then attempting to move them to more expensive items in the store (more commonly referred to as “bait and switch”). Essentially, the store survived by extracting the most money possible from any poorly informed customer who happened to wander in. To this end, the salespeople were well rewarded for every bit of margin they could eke out, and Wurtzel paid a great deal of attention to hiring the best sales force he could, including, in a departure from the customs of the time in the American South, hiring and promoting African Americans.

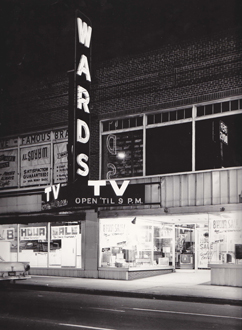

The second branch of Wards, the store that would become Circuit City. Beginning in the 1970s, its stock would outperform the U.S. market average by a factor of 18.5. (Photo from the documentary A Tale of Two Cities: The Circuit City Story, created by Tom Wulf. Used by permission.)

At first, there was nothing particularly remarkable about Wards in terms of its financial performance. It was marginally profitable, and by the end of the 1950s had four stores in Richmond but had failed in its efforts to expand further. This changed when consumer electronics sales in the United States began to take off, exploding from about $2 billion in 1960 to more than $6 billion in 1970. Wurtzel’s sales began to grow accordingly.

More than anything, Wurtzel wanted an empire. Demonstrating his shrewd negotiating skills, Wurtzel managed to hitch a ride on the discount store boom (Walmart, Kmart, and Target were all founded at this time). A deal with a members-only discount store allowed Wards to become the first electronics retailer in the country to expand outside its home city, and soon it went public. Its sales grew from $13 million in 1965 to $26 million by 1968, and that year, the company joined the American Stock Exchange. Along the way, Wurtzel made an ill-judged acquisition, a 120,000-square-foot Two Guys from Harrison discount outlet (on the basis of the name alone, he should have known it was a bad idea).

That was only the first misstep. Flush with cash from his public listing, Wurtzel began a program of conquest. He bought a Connecticut-based chain that sold hardware and housewares. He bought an audio equipment retailer based in Washington, D.C. He bought independent TV and appliance dealers across the Midwest. But like all empire builders, overstretch was his Achilles’ heel. (“The great proof of madness is the disproportion of one’s designs to one’s means,” Napoleon had warned, although he didn’t really lead by example on this point.) Soon, Wurtzel had reached too far. Indianapolis would be his Russia. The chain he wanted to buy was owned by Joe Rothbard, president of the National Appliance and Television Merchandisers and something of a pillar of the industry. Taking over Rothbard’s chain therefore had symbolic appeal. Wurtzel marched in and conquered, but, like Napoleon in Russia, after winning the battle, he didn’t have a plan for getting out. Of his acquisitions, only the audio business was reliably profitable, and the Indianapolis stores he had bought from Rothbard were soon bleeding money.

In 1969, Wards made a profit of $700,000, a margin of about 1.8 percent. That was Wurtzel’s best year. (Eight percent is the approximate average for major U.S. companies today, and in this book we will meet many individuals who have done, and are doing, much better than that.) These razor-thin margins left Wurtzel very exposed, and when the economy turned down in the early 1970s, the Wards retail empire was headed for bankruptcy. Fortunately, unlike Napoleon, Wurtzel didn’t have many enemies. But managing his empire of acquisitions was proving an overwhelming challenge in itself, and his operation was soon losing money. Even though sales of consumer electronics were still booming, Wards was stumbling.

Napoleon, in a fit of hubris, appointed his infant son king of Rome. In 1972, Sam Wurtzel installed one of his own sons, Alan, as CEO of Wards. It was a better appointment than Napoleon’s. Alan turned out to be a world-class manager. First, though, he needed to clean up his father’s mess. By 1975, despite selling off some unprofitable operations, Wurtzel junior found he had so little ready cash that the company was on the verge of going bust. But rather than declaring bankruptcy, Alan Wurtzel was able to convince the banks to back a plan for restructuring.

Alan cleaned out the deadwood (“Let the path be open to talent,” said Napoleon), and before long the company had new management, a strong strategic plan, and a changing corporate culture, but perhaps more importantly, Alan Wurtzel had stumbled across some wealth secrets—advantages that freed the company from the plague of competition, albeit only temporarily.

First, Wards joined the National Appliance and Television Merchandisers group, an industry association that enhanced the buying power of its members. In addition, the members had a tacit understanding that they would not expand into each other’s territories. As a result, Wards (according to Alan Wurtzel himself) faced little serious competition, leading to sales tripling and profits rising from 2.2 percent to an almost respectable 3.4 percent between 1978 and 1984. Wurtzel also changed the name of the company, from Wards to Circuit City—in part because he had by this point established a successful chain of stores with this name; in part because Montgomery Ward laid claim to the Wards brand in most of the United States.

Then, in the early 1980s, the U.S. government largely stopped enforcing a 1936 antitrust law that prevented retailers from using their size to extract better deals from suppliers. This meant that if there were two rivals—equivalent in efficiency, appeal to customers, skill of managers, and so on—the larger retailer would tend to make more money. This decision helped usher in the world of cloned shopping areas that we know today; it was also a bonanza for the newly renamed Circuit City.

In the wake of the antitrust decision, the Wurtzels’ unwieldy, outsized empire became a tool for levering profits out of suppliers’ pockets and into theirs. Just as Napoleon had modernized France, the Wurtzels would modernize retail, bringing grand scale and computerized management systems to a sleepy industry of small chains and mom-and-pop stores. The cozy arrangements of the National Appliance and Television Merchandisers group fell apart as members raced to expand into each other’s territories. The retail equivalent of the Holy Roman Empire was falling, and Circuit City was seizing the leftovers. The company’s sales and profitability exploded. Between 1982 and 1997, Wards’ shares outperformed the broader market by a factor of 18.5—the best performance of any Fortune 500 company in the United States.

Despite the exponential growth, there was a problem. It was a prosaic problem—one that afflicts even the greatest of great companies: by this point, observing Circuit City’s success, competitors had entered the market. Electronics retailing was not simply for pimply-faced young men with thick glasses, a pallor brought on by too many hours spent under fluorescent lighting, and a tendency to drop words like “megahertz” into casual conversation. Because there was money in it, electronics retailing was also for slick, take-no-prisoners, hit-the-ground-running executive types.

And they—like the British Empire that warred against Napoleon—posed a real threat. If you face little competition, bad management isn’t a problem, and the banks were happy to give Alan Wurtzel a second chance in the 1970s. If you face serious competition, there’s no room for error. By 1990, many other electronics retailers—including Highland, Silo, and Best Buy—had gone public, copying Circuit City’s hard-charging, rapid-expansion model. Circuit City was still the industry leader, with twice the sales of Silo and about four times the sales of most of the others. But there was trouble on the horizon. Circuit City’s 1991 strategic plan—an internal document used by senior management and the board to agree on the company’s overall direction—focused on archnemesis Good Guys, which had, as the plan noted, “proceeded to copy us across the board.” By 1993, the strategic plan was mixing annoyance with praise (imitation is, after all, the sincerest form of flattery): “[Good Guys,] the class act among our competitors… had the temerity to enter Los Angeles, our largest, most successful, and most profitable market.”

There were bigger problems to come. The first of these was Best Buy, which initially, like Good Guys, had attempted to copy Circuit City’s model. But by the 1990s, Best Buy had improved on it. Best Buy’s store layouts were more flexible, which proved useful as new categories of consumer electronics (the laptop, the smartphone, the tablet) came into being. In addition, Best Buy’s salespeople were paid by the hour, and thus cheaper than Circuit City’s commissioned salespeople. At first, Circuit City did not worry much about this low-cost threat, because Best Buy was not profitable. But in dismissing Best Buy for its poor margins, Circuit City was ignoring the lessons of its own history. Stock market investors were willing to fund unprofitable retail operations as long as they were growing fast, in the expectation that once they achieved scale they would become profitable. By the turn of the century, Circuit City was also being pummeled by Walmart.

The company responded sensibly, if predictably: it copied Best Buy, which was by then the new industry leader, hiring away Best Buy executives to replace its own managers in four key senior roles; replacing commissioned salespeople with cheaper employees paid by the hour; and rolling out new, more flexible and pared-down store formats. A new CEO, Philip Schoonover—another former Best Buy executive—oversaw the changes. (“One must change one’s tactics every ten years if one wishes to retain one’s superiority,” said Napoleon.)

But it was too little, too late. Circuit City had fallen from its spot as the top U.S. electronics retailer to third place. In the following year, 2001, profits roughly halved, from $327 million to $155 million. In 2003, profits nosedived to $41 million, and by 2004, the company was showing a loss. It was heading for a fire sale.

As Circuit City traced a flaming arc toward bankruptcy, media pundits vented their fury on its new CEO. The Wall Street Journal’s Herb Greenberg wrote that Schoonover was a likely candidate for his annual Worst CEO of the Year award. Shortly thereafter, Bloomberg Businessweek named Schoonover one of the twelve worst managers of 2008. That year, Workforce Management gave the humiliated CEO its inaugural Stupidus Maximus Award, honoring “the most ignorant, shortsighted and dumb workforce management practice of the year.”

These criticisms were somewhat unfair to Schoonover, as I will make clear in a moment. Circuit City’s troubles were quite possibly unsolvable long before Schoonover took on the CEO role. That said, he did make one notable blunder. As a cost-saving measure, one that could easily have been conjured by a man stroking a white cat, he fired all store employees making more than $18 an hour ($36,000 per year). The accompanying press release claimed they were “paid well above the market-based salary range for their role. New associates will be hired for these positions and compensated at the current market range for the job.” For readers lacking a business school (re)education, the notion that a salary of $36,000 was indulgent did not come naturally. Especially as Schoonover’s own severance package, when it came, was $1.8 million (considerably better than being exiled to Elba).

And yet, by the time Schoonover fired the company’s highest-paid retail employees, the writing was already on the wall.

WHY NO ONE IS GREAT FOR LONG

This was, in essence, Circuit City’s problem: it had come up with some great ideas. These ideas were then copied by others, most religiously by Good Guys, but most effectively by Best Buy. And then new competitors, notably Walmart, seized on this moment of weakness to launch their own invasions. Circuit City’s problem was, in a word, competition.

The media, of course, didn’t see things this way. They blamed Schoonover. Circuit City’s fall was both unexpected and, for most observers, inexplicable. The company had ranked 151st in the Fortune 500 only five years previously. Only two years before that, it had been one of only eleven companies lauded as “good to great” in Jim Collins’s famed business book From Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t.

It is worth dwelling on this latter point for a moment, as it illustrates the inexorable power of competition to take money from the pockets of the deserving rich. Circuit City’s financial performance had been phenomenal, almost up to the moment of its collapse. Collins did not give out accolades easily; companies only made his “good to great” list if their share price had outperformed the broader stock market by at least three times. Many household-name companies, including 3M, Boeing, Coca-Cola, GE, Intel, Walmart, and Walt Disney, fell short of this standard. Collins also excluded from “greatness” any company whose performance might have been a fluke, for example any that had ridden the coattails of a booming industry. Companies that had failed to sustain their exceptional performance for at least fifteen years were also excluded. Out of 1,435 firms that appeared in the U.S. Fortune 500 lists between 1965 and 1995—already an elite group of the world’s largest companies—only eleven met Collins’s exacting performance criteria. And among this elite eleven, Circuit City was, by some measures, the best, given that—as noted above—its stock price had beaten the market by a factor of 18.5.

Collins’s “great” appellation also certified that Circuit City had an exceptional corporate culture. Collins and his research team read and coded 6,000 articles and generated 2,000 pages of interview transcripts on the eleven “good to great” companies, as well as less successful peers. They identified factors that made these firms institutionally different from the others: corporate cultures that imposed discipline rather than requiring formal hierarchies, for example, and the ability to adopt necessary changes incrementally until these changes took on a momentum of their own, rather than attempting sudden transformations. Years later, Alan Wurtzel, the CEO of Circuit City at the time its performance accelerated, would write: “when I read Good to Great… I realized that these were brilliant metaphors [sic] for many of the policies my associates and I had followed in the course of building Circuit City.”

Of course, no great company, not even one with an exceptional culture and management, can avoid all of fortune’s arrows. Some are undone by disruptive changes. Kodak, for instance, famously fell victim to the replacement of film cameras with digital cameras. Blockbuster (which had contemplated a desperate bid for Circuit City) eventually collapsed as Americans stopped renting movies from stores and started renting them online. And yet, as far as anyone could see, there was no analogous external trigger for Circuit City’s troubles. While the bankruptcy took place during the global financial crisis (the Wurtzels’ Waterloo), Circuit City’s decline had begun years before, in the early 2000s. There was no obvious reason for this performance implosion. As Circuit City’s profits were collapsing between 2000 and 2004, the U.S. retail industry as a whole enjoyed a 12 percent inflation-adjusted increase in sales. Many of Circuit City’s competitors—notably Best Buy—did just fine, and are still doing fine today. It is no wonder the media blamed Schoonover.

It turned out that Circuit City was not the only one of the eleven companies profiled by Collins to collapse (the other was Fannie Mae, which appears here in chapter 7). And Collins was far from the only business-book author to have such difficulties. Take the era-defining In Search of Excellence, by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman. Only two years after that book was published, nearly a third of the forty-three companies profiled were in financial distress.

The problem isn’t that Collins, Peters, and Waterman picked the wrong companies. The problem is systemic.

Profits are an irresistible lure for competition, and competition results in the undermining of profitability. Indeed, the higher the profits a company reports, the more would-be imitators of its strategy and methods it is going to attract. These imitators will lure away a few key personnel with generous salaries, employ consultants to study the successful company’s business model intensively, and generally attempt to imitate its techniques. And soon the company is not profitable anymore. The share price will plummet. The CEO will be turfed out unceremoniously. The people he considered close friends will no longer return his calls; his archrivals from high school will toast his downfall; his waterfront property in St. Barths—the modest ten-room villa with the infinity pool—will be put up for auction.

This may come as a surprise for noneconomists, but in the world of economic theory, it is not possible to get rich. In a perfectly competitive free market, profits are zero (or close to it, as I’ll explain in a moment). That is, when firms can freely enter a market and imitate existing companies without restriction, the result is that businesses end up competing on price. This implies that they will keep undercutting each other until market prices have fallen to the point where companies are selling what they produce for the same amount it costs to produce it. If someone else enters the market, prices will fall yet further and everyone will start making losses. This situation will not last, because eventually someone will go bankrupt. Prices will then bounce back up to the cost of production again. It’s a stable equilibrium. Over the long term, nobody makes any real profit at all. This might sound ridiculous as a description of the real world, but the difficulty of finding “great” companies that stay “great” suggests there’s some truth in it.

I should note one caveat: when economists say “profit” they mean something slightly different from what the average businessperson might mean. An economist’s view of the cost of doing business takes into account all of a company’s costs, including its cost of capital (not just costs of wages, production machinery, property and so on). Hence a “profit” for an economist indicates that a company is earning returns that exceed its cost of capital. Companies need to earn some kind of return—otherwise, no one would provide the funding needed to start the company in the first place. Hence the price at which companies in perfectly competitive markets end up selling will include just enough profit to attract investors and entrepreneurs. In a country like the United States, this implies that profit margins in the low single digits are not all that surprising. Profit margins well into the double digits, by contrast, usually indicate the existence of real, economic profits—the kind of profits that would impress an economist.

It is possible to find markets that embody this vision of perfect competition in many places around the world. In New York City, for instance, just east of Citi Field (home of the New York Mets), there is an area of about ten square blocks taken up entirely by auto-parts retail stores. On the West Side, the stores are run primarily by proprietors apparently of Central Asian, South Asian, or North African origin (New Pamir Muffler, Merah Auto Glass, Aryana Collision, Sultan Auto Body). Farther to the east, owners with Latin affiliations predominate (Colombia Auto Glass, Gonzales Muffler, New Pancho Auto Glass). There are also East Asians (Ming Repair Shop) represented, as well as any number of generic names (Sunrise Used Auto Parts, Union Muffler Shop, Best Auto Plaza Mufflers and Glass). There are so many, in fact, that it is difficult to keep an accurate count. At the time I attempted it, the number reached about sixty. With this many shops offering the same or similar goods in such close proximity, competition is fierce. That is why they are all clustered there, on that single plot of land: they fully intend to pound the heck out of each other (in a commercial sense). If there is any profit to be made, it is in the skill of salespeople eking out the maximum each customer is willing to pay—not unlike the early days of Wards.

The nightmare of (perfect?) competition—more than fifty auto repair shops cluster next to one another near Citi Field in Queens, New York. (Sam Wilkin)

Of course, Circuit City, at least during the boom years, was not operating in such a world of perfect competition. Like most major retailers in the modern-day United States, it had a few wealth secrets on its side. For instance, it had a brand, protected by law (so no one else could legally open a store called Circuit City). This is an important wealth secret, as we shall discover in chapter 6. The company’s 2001 strategic plan proclaimed—rhetorically but accurately—“nothing is more important than the Circuit City brand.”

The company also had another crucial wealth secret. Once the U.S. government stopped enforcing the 1936 antitrust law that prevented retailers from using their size to extract discounts, Circuit City had scale economies on its side (that is, larger operations would be more lucrative). As we shall discover in chapter 3, under certain circumstances, scale economies can be exceptionally valuable to seekers of wealth. Circuit City’s CEO in the mid-1980s, Richard Sharp, was quick to understand the implications of this regulatory shift. He decreed that henceforth the company would focus primarily on markets where it had or could build a dominant share (defined as not less than 15 percent of TV and appliance sales, and at least a 50 percent larger share than its nearest competitor). Sharp wrote that a “strong market penetration makes us more cost-effective.… This and other efficiencies permit us to keep our prices low while investing in additional customer services. The result is even better values and deeper market penetration… [that] allow us to achieve above average profitability.” He noted that this was a virtuous cycle, which “underwrites its own reinforcement and perpetuation.”

In other words, if Circuit City was dominant in a particular market, and therefore larger than rivals, its costs would be lower than those of its rivals (because it could use its size to extract greater discounts from suppliers). If its costs were lower, it would be able to set prices lower than the competition and still make money. These lower prices would, in turn, cause customers to abandon rivals and shop at Circuit City—which would further increase the company’s market share, and thus its size, and thus its cost advantage. It was a self-reinforcing cycle that could, over time, produce a monopoly. And monopoly is, without question, the most exciting word in business.

FROM GREAT TO GONE

As an economist, I was not surprised that the Wurtzels fell on hard times. Nearly all great businesspeople suffer this fate, unless they have the kind of wealth secrets profiled in this book. Nor was I surprised when Circuit City started trying to copy Best Buy—exactly the right response, if a little unimaginative. I was, however, very surprised they went bankrupt. The company’s scale should have been almost a guarantee of profitability. The same with their brand, built up over roughly three decades (more, if one counts the Wards heritage). Perhaps not much profitability—say, a percentage point or two of “economic” profits. But there is a big difference between a little profitability and bankruptcy. For a company in Circuit City’s position to go bankrupt required something to go very, very wrong.

This surprising collapse is why business books do have something useful to say about the fall of Circuit City. That great businesses shall be dragged down to mediocrity is inevitable; that they shall fail catastrophically is not. Circuit City’s descent into bankruptcy required clever, motivated, and competent people to make some fairly extreme mistakes. Jim Collins, in his well-timed 2009 follow-up book, How the Mighty Fall, blamed issues relating to corporate culture—hubris, undisciplined expansion, denial of risks. James Marcum, the Circuit City CEO who presided over the company’s bankruptcy (after the firing of Schoonover), believed that word-of-mouth regarding poor service and the company’s inability to keep items in stock had destroyed the value of its all-important brand. Alan Wurtzel, in his book Good to Great to Gone, which detailed the rise and fall of his own company, identified many culprits, including bad management, bad luck, and strategic mistakes. Former employees interviewed for the documentary A Tale of Two Cities: The Circuit City Story blamed strategic missteps such as halting appliance sales, as well as errors of financial management—most notably an exceptionally ill-timed share buyback.

Although many factors no doubt played a role, one identified by Wurtzel seems particularly crucial. When the company was in its phase of most rapid expansion in the 1980s, Wurtzel opened stores using long-term (twenty-year) leases, because twenty-year leases did not appear as liabilities on the balance sheet (due to a technicality of accounting regulations). Initially, when Circuit City faced little direct competition, that was not a problem. But when competitors showed up, with stores in slightly better locations (often because an area’s demographics had shifted since Circuit City had built its stores), Circuit City needed to respond either by moving its stores, shutting down old stores and opening new ones, or upgrading its stores. Unfortunately, it could not get out of its long-term leases. Making the necessary changes could be accomplished only at great expense. As the company headed for trouble in the early 2000s, management faced up to this problem, and even came up with plausible plans to resolve it on numerous occasions—but always balked at the cost (one plan, which would have relocated two hundred stores and remodeled another four hundred, had a price tag of a whopping $2.1 billion). Once the company’s results had declined to the point that it was at last willing to take the plunge, it was too late. Investors (and prospective buyers) had lost confidence in the company—a company that, unlike in the 1970s, faced merciless, ravenous competitors. Circuit City was, at that point, good only for scrap.

The ultimate problem, then, is not that Alan Wurtzel was not an extraordinary leader, or that the management team of Circuit City was not extraordinarily talented. The problem is that there is a huge number of extraordinary leaders and extraordinarily talented people in the world. And worse yet, in business one does not need to be as talented as the best performers in order to rival them. One needs only to be able to understand and copy what they have done. Did Best Buy have an extraordinary corporate culture and exceptional leadership that could match that of Circuit City? Was Best Buy a “great” company? Perhaps not. But it was good enough to get the job done. If Circuit City wanted to stay ahead of Best Buy (and other copycat competitors), it needed to think of a new, market-leading strategy or innovation every year—and roll it out just as soon as its rivals had copied the last one. Or it would need to do something so extraordinary that it could not be copied.

Most rich people probably believe they are geniuses, and that their wealth comes from this kind of persistent outperformance. I admit to being skeptical, but let us for a moment take such claims at face value. Let us say that you are a genius. Or better yet, that you could gather together the greatest group of geniuses ever assembled, and go into business with them. Would you then be able to trounce all comers? Would you be able to overcome the inexorable logic of competition?

Perhaps the boldest experiment ever undertaken in this regard involved a hedge fund by the name of Long-Term Capital Management. LTCM brought individuals with an almost unmatched track record in finance together with the world’s greatest experts on the economics of financial markets. They did not have any wealth secrets—at least, not that I know of. That said, when most people think about making a lot of money, a hedge fund probably sounds like a good way to go about it. And it was, quite possibly, the largest start-up business in world history.

One might therefore have expected great things: billion-dollar fortunes, Ferraris, mansions, life-size replicas of the starship Enterprise, including a Seven of Nine blow-up doll (these were, after all, math geniuses).

And at first, things looked pretty good.

THE LARGEST START-UP IN HISTORY

Unlike Circuit City, LTCM was not “good to great”—it was just great, right from the word go. The fund was founded by John Meriwether, a successful self-made Wall Street executive from the South Side of Chicago. The fund’s core group of partners were experts in quantitative finance drawn from the team Meriwether had managed at the investment bank Salomon Brothers, including Eric Rosenfeld, a former Harvard Business School professor; William Krasker, an economist with a PhD from MIT; Lawrence Hilibrand, with two MIT PhDs; and Victor Haghani, with a master’s in finance. At Salomon, this team had been marvelously successful. They made $485 million in profits in 1990, $1.1 billion in 1991, and $1.4 billion in 1992. To put this figure in perspective, in the early 1990s, $1 billion was approximately the profit earned by the entire rest of the bank. That is, Meriwether’s team of about 100 employees earned about $1 billion; the other 6,000 people employed in Salomon Brothers’ client business earned about the same. This kind of thing could go to one’s head.

Meriwether had left Salomon Brothers following a scandal over improper trading activity (not his) and a bruising turf battle with other banking executives. As well as recruiting many of his trusted Salomon colleagues to his new venture, Meriwether convinced two academics to join the fund: Myron Scholes, of Stanford, and Robert Merton, of Harvard. Far from being just any old academics, these two men were arguably the finest minds on earth when it came to the study of financial markets. A few years after joining the fund, they would go on to share the Nobel Prize in economics.

The team’s spectacular track record, combined with the presence of the (future) Nobel laureates, made marketing easy. Meriwether’s roadshow to pitch the fund to prospective investors hooked in banks, pension funds, CEOs, McKinsey partners, university endowments, government-owned financial institutions, and more. When it was all done, LTCM opened with $1.25 billion under management, a larger pool of start-up investment than at any previous hedge fund, and perhaps the largest capital base of any start-up in history. “Never has this much academic talent been given this much money to bet with,” gushed Businessweek.

To be sure, the professors would not be directly involved in the fund’s daily trading activities. But their theories would guide the fund’s approach. In broad terms, these theories suggested that financial markets would become increasingly efficient over time, reflecting with greater and greater accuracy all available information. Prices in efficient financial markets can be thought of as statements about underlying economic realities, and thus prices even in very different markets (markets in different parts of the world, markets for different types of financial instruments) should, over time, become increasingly consistent with each other. Or so the theory predicted.

Reportedly, most of LTCM’s trading strategies involved identifying some kind of disparity in market prices and betting, heavily, that this disparity would vanish (such trading strategies are typically known as “arbitrage” or “relative value” strategies). An early target was thirty-year U.S. treasury bonds, which are issued every six months. Sometimes the bonds that have been issued most recently pay a little less interest than those issued six months before. This disparity probably exists because the most recent bonds are traded most actively—and hence have greater appeal to investors who think they might need a financial instrument they can dump quickly to raise some cash. Over time, as newer bonds come onto the market, the differential between the bonds issued six months apart should vanish. It sounds complicated, but this was perhaps the simplest trade LTCM got involved in (these were, after all, geniuses). In 1994, when LTCM got its start, the differential was wide: bonds issued in February 1993 were trading at a yield of 7.36 percent, while the more actively traded bonds from August 1994 were yielding “only” 7.24 percent.

A tenth of a percentage point of interest would be negligible to most people (would you move your savings account for that?), and yet for LTCM it was a big opportunity, because the differential was almost guaranteed to vanish over time. It was as close to a sure thing as financial markets get.

Yet actually executing a trade that would take advantage of the disparity on U.S. treasury bonds was quite a challenge, which is why the gap persisted. Arranging the necessary combination of long and short trades wasn’t hard; the problem was LTCM would make only about $16 on each $1,000 it put into the trade. Earning serious money would mean buying and selling a lot of bonds—like, say, $1 billion worth, which is just what LTCM did. Few investors had that kind of money. Even LTCM didn’t have that kind of money (or rather, it did, but if it had used it, this one trade would have tied up the firm’s entire capital).

Overcoming this problem involved executing the trade using other people’s money, and finding a way to borrow this money almost without cost. Because the gap LTCM was targeting was only about a tenth of a percentage point, even a small interest cost relating to borrowed money would have made it unprofitable. This magic trick of costless borrowing was accomplished via the careful balancing of collateral from various transactions. Thus the geniuses at LTCM were innovative in many ways. They had come up with a new approach to identifying opportunities; they had invented new mechanisms to act on these opportunities; and they had developed financial models that could assess the risk associated with the resulting billions of dollars of complex exposures and determine whether it was worth it.

Initially, LTCM was all but alone in taking on this kind of trade, with this kind of scale. Within a few months, its trades on the tenth of a percentage point differential in U.S. treasury bonds had yielded $15 million for the fund. Indeed, most of LTCM’s early trading strategies were astoundingly lucrative. In 1995, the fund earned a return of 59 percent. Investors, after paying LTCM’s rather generous management fees, received 43 percent, a fairly spectacular return. Compare this to the profitability of Circuit City (usually less than 5 percent), and one understands why, despite the high fees, investors were falling over themselves to get involved.

That year, LTCM added an additional billion dollars in funds from new investors, bringing its capital under management to $3.6 billion. And it was just getting started. In 1996, LTCM delivered returns of 57 percent, or 41 percent after fees. The partners had invested much of their own money in the fund (some even borrowed money and invested this as well). Thus, as the fund went up in value, the partners were becoming very, very rich. Some bought sports cars; others left their wives, dyed their hair, or bought mansions. LTCM’s total profits in 1996 of $2.1 billion exceeded those of McDonald’s, Merrill Lynch, Disney, Xerox, American Express, and Nike. And these corporate titans were bested by LTCM’s staff of fewer than one hundred people.

And yet, as a hedge fund, LTCM had one crucial vulnerability. That is, it could not directly execute its own transactions. To carry out its trades—buying long, selling short, making derivatives deals—it had to rely on investment banks. This was a big change from Meriwether’s days running his arbitrage group at Salomon Brothers, which could execute all of its trades internally.

This was a vulnerability because when LTCM asked investment banks to carry out its trades, it was, in effect, telling them what it was doing. This was risky because, in addition to their client businesses, investment banks had trading arms (like Meriwether’s group at Salomon Brothers). There was nothing to stop the banks’ trading arms from then copying LTCM’s underlying strategies. Hence every trade LTCM executed was, in a sense, a deal with the devil.

Indeed, LTCM faced similar threats from all sides. One eager investor during Meriwether’s initial roadshow was PaineWebber. As a fund management company, PaineWebber was, in a sense, a competitor to LTCM. One objective of its $100 million investment in LTCM was to gain access to new trading ideas. A number of the fund’s other investors probably had the same plan. Needless to say, Meriwether kept his letters to investors, in which he described the fund’s strategy and performance, as abstract as possible.

Overall, LTCM attempted to share as little information as was legally permissible. To this end, the fund parceled out its trades piecemeal among several banks. Where a complex set of balancing trades were required, it would approach a different bank to carry out each part, hoping to maintain the bankers’ ignorance of its overall strategy. Most junk bond trades went to Goldman Sachs; most government bond trades went to J.P. Morgan; most mortgage trades went to Lehman Brothers; and Merrill Lynch got a lot of work in derivatives. “Larry [Hilibrand] would never talk about the strategy. He would just tell you what he wanted to do,” recalled Kevin Dunleavy, a Merrill Lynch salesman. The banks, of course, objected, complaining about LTCM’s lack of “transparency.” But they typically went along. In part, it was good business; and in part, they were probably capable of deducing much of what was happening anyway. If LTCM was tying up $1 billion in a single trade, it stood to reason there was an offsetting trade somewhere.

One junior trader, interviewed after the collapse, recalled being perpetually worried that if the press found out about any of his trades, he would lose his job. Even LTCM’s own employees were, as much as possible, kept in the dark—just in case one might be poached by a rival. Some Connecticut-based employees of the fund resorted to calling their London counterparts in an effort to discover what the firm was actually doing. There was even a social separation. Traders were reportedly never invited to partners’ homes and were also excluded from most of the meetings where key decisions were made. Some later complained that partners refused to engage the trading staff even in polite conversation.

But even this rather extreme effort at secrecy was not enough. LTCM was making so much money that it was going to attract the best of the best as competitors—the kind of people who were not intimidated by little things like Nobel Prizes. The elite investment banks quickly jumped on the bandwagon. Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse First Boston started their own arbitrage units. By the late 1990s, nearly every investment bank on Wall Street had an arbitrage desk. LTCM’s success also inspired more direct imitators. Hedge funds using arbitrage strategies (usually referred to as “relative value” strategies) were, by the end of the 1990s, being set up “every week” according to one analyst following the sector. Indeed, by this point, hedge funds using relative value strategies reportedly accounted for about a quarter of the trading volume on the London stock market.

By 1997, this competition had started to bite. LTCM’s returns were plummeting. The fund earned “only” 25 percent that year—17 percent after fees. Not bad compared with most businesses, but less than half of what the fund had been making. The partners simply couldn’t find the kinds of opportunities they wanted. As competitors piled into arbitrage trades, the price disparities that LTCM thrived on vanished quickly. By the end of the year, LTCM had decided to return about half of the money that outside investors had put in, whether the investors wanted it or not. “Everyone else was catching up to us,” said LTCM partner Rosenfeld. “We’d go to put on a trade, but when we started to nibble, the opportunity would vanish.” The fund handed back $2.7 billion it couldn’t use.

FROM GOOD TO AVERAGE

Perhaps Meriwether’s team of math geniuses and Nobel laureates were, in the early days, doing something so clever that no one else could even understand what they had done. But if so, it didn’t last. There are, as we’ve already observed, a lot of clever people in the world, and until someone finds a way to get rid of them, competition will remain a problem even for geniuses.

That LTCM was able to stay ahead of its competitors as long as it did owes a great deal to two relatively unique aspects of the hedge fund business. The first is leverage—the ability to use other people’s money to amplify one’s bets. Indeed, LTCM’s combined bets, totaling some $2 trillion, were not far shy of a hundred times the amount of money actually in the fund. Unlike regulated financial institutions such as banks, the main constraint on the use of leverage is a fund’s ability to convince others to extend credit at a reasonable price. But LTCM, in part due to its sterling reputation, was able to leverage itself to the hilt.

As a hedge fund, LTCM also enjoyed another advantage that is relatively unique to the hedge fund sector: secrecy. The big investors that are allowed to get involved with hedge funds are presumed to be sophisticated enough to look out for themselves. Hence hedge funds are required to report very little of what they do. As a result, Meriwether was wholly within his rights in keeping his investors in the dark about what he was doing with their money. Most companies have extensive reporting obligations—especially to their investors, but also to the government and, increasingly, to society at large. This applies to publicly traded corporations, of course, as well as to mutual funds, and is an obvious obstacle to secrecy. It was much easier for LTCM to keep secrets, at least for a time.

The combination of leverage and secrecy makes it possible, even without wealth secrets, to make real money in hedge funds. Secrecy implies the possibility of retaining a unique advantage, at least for a little while; and leverage means you can make (or lose) huge amounts of money quickly, so in that little while you can become a billionaire. Some of LTCM’s partners were, at their peak, worth about half a billion dollars. And four of the hundred richest people on earth—George Soros, Ray Dalio, John Paulson, and James Simons—are hedge fund executives. Of course, four out of one hundred is not all that many; the far more lucrative question of where the other ninety-six fortunes come from is something I’ll explore in later chapters. But still, starting a hedge fund is not a bad way to make a fortune.

Indeed, that was probably how the story should have ended: with some modest fortunes, followed by a slow ride into the sunset as the credits rolled. The most likely scenario was that LTCM’s performance, after its spectacular early years, would drift gently back to earth. Fans of Daniel Kahneman will recognize this phenomenon as “regression to the mean.” The mean performance of the hedge fund sector is approximately equivalent to the broader market return (according to many academic studies). In 1998, the Dow Jones Industrial Average returned about 16 percent. In 1997, LTCM’s returns had been roughly that amount. In 1998, one might have expected more of the same.

But LTCM’s performance did not regress to the mean. Instead, the fund’s value fell catastrophically. Indeed, it lost so much money that it threatened to cause a global financial collapse.

The proximate cause of LTCM’s demise was financial market turbulence triggered by Russia’s 1998 debt default. In August 1998 alone, LTCM lost 45 percent of its value. On one particularly bad day, August 21, it hemorrhaged nearly half a billion dollars. And LTCM had used so much of other people’s money to make its bets that, when these bets went sour, it was a realistic prospect that one or more Wall Street investment banks (which had, in effect, extended LTCM the credit it used) might collapse. Fortunately for them, the U.S. Federal Reserve stepped in to broker a rescue deal. Wall Street’s investment banks agreed to take over LTCM and jointly manage its unwinding. There would be a fire sale here too—but not of LTCM’s physical assets. Rather, the banks would arrange the sale of LTCM’s investments and derivatives contracts. By 1998, LTCM had some 60,000 swaps positions on its trading books, so it was one of the messier fire sales in history.

I should emphasize that LTCM’s investors, including its founding partners Meriwether, Rosenfeld, and Hilibrand, as well as the Nobel laureates, were not rescued. Their vast fortunes were largely wiped out. The U.S. Federal Reserve, when it stepped in to broker a deal, was not trying to rescue LTCM; it was trying to rescue the investment banks (which was very interesting, and the basis for a wealth secret, as we shall discover in chapter 4).

Why did LTCM implode so spectacularly? One explanation for the fund’s collapse involved the efforts of the partners to continue to produce extraordinary returns in the face of rising competition. With their favorite trades no longer profitable once the investment banks knew about them, LTCM was forced to seek out price disparities in ever more esoteric markets. For instance, it reportedly plunged so heavily into the tiny market for commercial mortgage-backed securities that it caused the size of the market to double. At that scale, LTCM’s trades were driving market prices, not responding to them. The fund also began to make some bets where theory could not help them. One such bet involved the share prices of companies that were contemplating a merger. These prices can be expected to converge if the merger goes forward, which has nothing to do with market efficiency. “This [type of] trade was by far the most controversial in our partnership,” said Rosenfeld. “A lot of people felt we shouldn’t be in the risk arb[itrage] business because it’s so information sensitive and we weren’t trying to trade in an information-sensitive way.” Because the fund’s bets were so large—as noted above, constituting some $2 trillion in theoretical exposure to loss—a few unwise trades such as this might have been enough to lose everything LTCM had and more.

These kinds of explanations are, however, a little unsatisfying. For one thing, although its exposure was huge, most of LTCM’s trades were balanced against each other, so that the fund was—or at least should have been—exposed only to a very few, carefully selected types of risk. Moreover, it wasn’t a few unwise trades that went wrong. In the fall of 1998, just about every trade LTCM had on seemed to go against them.

The LTCM partners offered their own explanation for what happened. They contended that other financial institutions—possibly the investment banks that had carried out LTCM’s trades—knew where the fund had bet heavily, and thus where LTCM, once it got into trouble, could be forced to sell assets at an exceptionally low price. According to this explanation, the investment banks (or perhaps other hedge funds) were trying to force a fire sale. “It was as if there was someone out there with our exact portfolio,” said Victor Haghani, an LTCM partner, “only it was three times as large as ours, and they were liquidating all at once.” Meriwether agreed: “The few things we had on that the markets didn’t know about came back quickly,” he said. “It was the trades the markets knew we had on that caused us trouble.” This explanation should also be taken with a grain of salt. The banks were by this point overseeing the salvage of LTCM, so if they had been squeezing the math whizzes, they would have been shooting themselves in the foot. However, LTCM’s implosion was indeed spectacular—so spectacular that such conspiracy theories are not entirely implausible.

The next time around, the result would be more in line with expectations. Meriwether gathered together a few of his LTCM colleagues and started another hedge fund. After losing 44 percent of its value between September 2007 and February 2009, it was quietly closed down. That is the harsh reality of life in the absence of wealth secrets. One enters with a team of geniuses, two Nobel laureates, and not one but several revolutionary ideas. And within a few years, one quietly exits stage left, having earned next to nothing and seeded an entire sector of copycats.

WINNING THE WEALTH SECRET WAY

There are things that make companies (like Circuit City) great, and people (like LTCM’s partners) great. And then there are things that make companies and people very, very rich. These aren’t really the same thing, so it’s time now to turn to the latter.

I have already alluded to a few wealth secrets, albeit modest ones. Circuit City found itself in the possession of a wealth secret—its scale—once the U.S. government stopped enforcing antitrust law in retail. And so the company built cheerful, identical red buildings with plug-shaped entrance halls all across America, crushing its mom-and-pop competition in the process. But only temporarily. Once its approach was copied by other companies—which also went public and used the funds to build thousands of identical shops in cheerful primary colors—it was no longer a source of profitability. A better wealth secret was Circuit City’s brand, which was, and remains, uncopyable (a discount online retailer bought the rights to the brand in the fire sale). But even this wasn’t enough to save the company from its own strategic mistakes.

Similarly, Long-Term Capital Management had wealth secrets of a sort. Its brilliance—or good luck, if you are a cynic—enabled it to do something that others found it hard to replicate. Together with the secrecy and leverage that are the privileges of the hedge fund sector, this brilliance (or luck) was a foundation for temporary, but extraordinary, success. But it wasn’t really a wealth secret, and once it was copied, the fund’s ingenious strategies became a vulnerability.

True wealth secrets have far more staying power than LTCM’s great ideas or Circuit City’s scale. While they are fundamentally sustainable, exploiting them to their full potential may well require genius—I leave that for you to judge, after reading the character studies that follow. The next chapter takes us back to ancient Rome and, appropriately enough, the story of a man who for a long time was believed to have been the richest person who had ever lived.