3

Wealth Secrets of the Robber Barons

THE SUPERYACHT

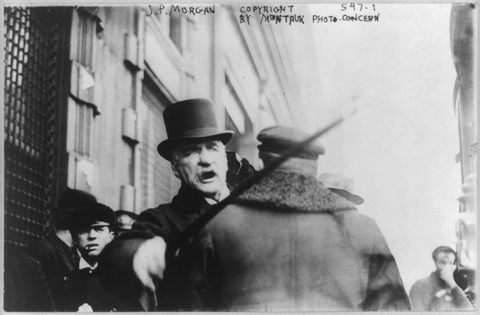

John Pierpont Morgan (hereafter Pierpont Morgan, to distinguish him from his bank, J.P. Morgan) cut a larger-than-life figure. He stood more than six feet tall, weighed over two hundred pounds, and suffered a permanent skin condition that so disfigured his nose that a Russian finance minister advised him to have it surgically corrected. England’s Queen Alexandra recommended a treatment involving electric shocks (which Morgan did try, but to no effect). Today the condition would be treated with lasers. Morgan’s portrait photographer Edward Steichen called the nose a “sick, bulbous mass in the center of his face,” and retouched the photographs. A children’s rhyme of the day included the line “Johnny Morgan’s nasal organ has a purple hue.” More charitably, a mistress said, “One forgets his nose entirely after a few minutes.” Morgan also had a walrus mustache, wore a top hat, carried a mahogany cane, and chain-smoked Cuban cigars (when he was seventy years old, his doctor demanded that he reduce consumption to twenty per day).

Pierpont Morgan became, if not a head of state, the uncrowned king of American finance. The kaiser sent a life-size bust as a gift (this was wisely misplaced in 1914). England’s King Edward VII stopped by Morgan’s London pied-à-terre for iced coffee and was reportedly impressed, although he felt the setting too cramped to display Morgan’s vast personal art collection (Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Gainsborough) to good effect. After meeting Morgan in 1905, Pope Pius X noted with regret: “What a pity I did not think of asking Mr. Morgan to give us some advice about our finances!” When, years later, Morgan’s reputation was besmirched, Joseph Stalin took it upon himself to defend the man: “We Soviet people learn a great deal from the capitalists.… Morgan, whom you characterize so unfavorably, was undoubtedly a good, capable organizer.”

Morgan’s first yacht was the Corsair. At the time of its construction in 1882, it was the largest and most advanced yacht in the United States, combining steam power with schooner rigging and a hull of iron (later models—there were two more in Morgan’s lifetime—were made of steel). It was built for speed and looked the part, with a low profile, gleaming black hull, clipper bow, and raked-back smokestacks. The main saloon had black-and-gold silk upholstery and a tiled fireplace. Within nine years, Morgan had outgrown it. He commissioned a second, larger Corsair weighing 560 tons with eight staterooms, oak paneling, and dark green upholstery. Each room had a working fireplace, sponge hooks in the bathrooms, and a nook by the bed on which to place one’s watch at night. Its length was limited to 241 feet by Morgan’s requirement that it be able to turn around in the Hudson River below his weekend home, Cragston. Outfitted with cannon, it blockaded and destroyed a Spanish fleet at Santiago Harbor during the Spanish-American War (with the help of two other American ships), although a mast was damaged by a Spanish shell. Morgan promptly commissioned another Corsair, larger still. This one had maple paneling, a library the width of the hull, a player piano, leather portfolios filled with “Corsair” stationery, silver-backed hairbrushes, pearl-handled fruit knives, gold spoons, eighty-four linen tablecloths, forty-seven finger bowls, and one cocktail shaker marked “JPM.” It also eventually saw service in the U.S. Navy, during both world wars. Meanwhile, Morgan’s London getaway had been acquired by the U.S. government and pressed into service as the U.S. embassy in Great Britain.

Pierpont Morgan was, in all respects, a big man. Rumors of his ill health caused the U.S. stock market to slump. And yet, he is in a sense an odd choice as our “wealth secret” representative of the U.S. capitalists known today as the robber barons (Morgan, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Gould, Vanderbilt). Morgan’s fortune was large: at his death, his estate was valued at roughly $80 million (about $1.9 billion today). But by the standards of the robber barons, who achieved levels of opulence hitherto unmatched in history—eclipsing even the ancient Romans—this was small potatoes. “And to think, he was not a rich man,” said Andrew Carnegie, hearing of this figure upon Morgan’s death. Carnegie’s fortune was, at its peak, $240 million (about $6.8 billion today).

And yet, in another respect, Morgan was the quintessential robber baron. He despised competition, and worked relentlessly to prevent it from happening. “Ruinous competition,” he called it, “wasteful rivalry,” or “competitive skulduggery.” Of course, most right-thinking businesspeople hate competition, as it is what prevents them from getting richer. John D. Rockefeller, the wealthiest of all the robber barons, wrote in his autobiography: “the one thing which… a business philosopher would be most careful to avoid… is the unnecessary duplication of existing industries. He would regard all money spent in increasing competition as wasted, and worse. The man who puts up a second factory when the factory in existence will supply the public demand… [is] unnecessarily introducing heartache and misery into the world.”

Truer words were never spoken, but the question is how to prevent anyone from building a second factory, when the first factory is spectacularly lucrative and indeed its owner is well on his way to becoming the wealthiest person in history. This is the question that Morgan, more than any of the other robber barons, was able to answer, and as a result a few Americans became fabulously rich. Indeed, without Morgan’s assistance, Andrew Carnegie may well have been unable to secure his fortune.

Moreover, Pierpont Morgan showed that, if one has a wealth secret, there is no need to work particularly hard. He seemed to spend about half of his life on holiday, and still made a billion dollars (in today’s money). Indeed, he lingered so long vacationing in France that the town of Aix-les-Bains named one of its streets after him.

Now that is a wealth secret I can relate to.

AMERICA RISING

A modern executive, traveling back in time to study Rockefeller’s wealth secrets at the great man’s knee, would—assuming she could avoid the usual pitfalls of entering the wrong date in her time machine or being hunted by Bruce Willis—have found commercial life in the United States of the 1800s tremendously frustrating. While the robber barons would change the face of American commerce into something our executive might recognize, before their rise, American business, and the American rich, would have seemed a different breed.

There was, to be sure, a thriving market capitalism. But America was a long way from becoming an industrial powerhouse. Most manufacturing was concentrated in the North, while the economy of the South was driven by plantations and hence slave labor (the Civil War would erupt in 1861). Unlike Roman slavery, of course, there was almost no chance of upward economic mobility for American slaves. There were railroads, but these local, point-to-point lines generally used different track sizes so that direct interconnection was impossible. Train engines and cars were routinely ferried across rivers because building bridges was too expensive. There were no motorcars, nor of course airplanes, so the rich traveled by rail (and the very rich, by private rail carriage or personal yacht). Wall Street was already the nation’s center of finance, and traders there bought and sold bonds and shares. At first, they conducted their business standing out on the street itself, but eventually moved indoors.

Our time-traveling executive would have found the monetary system particularly jarring. In the early 1800s, the federal government issued gold and silver coins, but all paper money was issued by banks, only as reliable as the bank that issued it and generally usable only in the locality surrounding the bank. There were some seven thousand different kinds of banknotes in circulation, with no centralized regulation and, naturally, rampant counterfeiting. This would change during the Civil War, when the government of the North began to issue paper currency backed by a law that required debtors to accept it. As these notes were written in green ink, they came to be known as “greenbacks,” a nickname for the U.S. dollar to this day. When the North eventually won the war, the system went national.

The development of a national paper currency was a distinct improvement. But there was little sign of progress on another horizon: hardly anyone in business was making any money. Taking time off from searching for a method to power a flux capacitor, our time traveler might have tried her hand at a little commerce, but conditions for most businesses were worse even than those described in chapter 1. Circuit City at least made a decent sum before being dragged back to earth. The same with LTCM. In the 1800s, by contrast, most businesses faced conditions approximating perfect competition, and had little leverage. As a result, individual proprietors had to work for decades just to pay themselves a living wage. U.S. industry and agriculture were dominated by what the trade unionist Samuel Gompers called “small, ruinously competitive companies.” Really, it was horrible.

Indeed, the only large businesses to speak of were in infrastructure. As late as 1884, when the Dow Jones company first began to print its stock market average, nearly all of the stocks in the index were railroads. The few others were telegraph and steamship companies, and there was not much else worth including beyond that. In 1899, the ten largest railroads each had a market value of more than $100 million (about $2.9 billion today), but outside the rail sector even the biggest companies were comparative minnows. Indeed there were few industrial companies valued at more than $10 million. Manufacturing was apparently the wrong sector in which to hunt for wealth secrets.

That said, Britain had undergone its industrial revolution, and the United States was following, initially by stealing British technologies—most notably spinning and power loom designs, which spurred the growth of textile mills. By the mid-1800s, this young country was leading the world in some areas of innovation. In particular, it excelled at inventions that enabled the replacement of skilled manual labor with unskilled workers, which was politically difficult in Europe, with its long tradition of guilds.

Our time traveler, hoping to escape the plague of competition, would have been drawn to such developments. The patent laws that encouraged these innovations protected business inventors from imitation, so patent owners fared far better than most small proprietors of the day. Yet their earnings never matched those of the robber barons. The greatest of the inventors, Thomas Edison, created not only the first reliable electric lightbulb but also the telephone, record player, and motion picture projector—registering 1,093 patents, an average of one every two weeks, over a forty-year period. He did very well for himself, but never quite made the rich list, probably in part because he did not seem to care about money.

However, many of the companies that would later come to dominate the U.S. economy acquired patents from men such as Edison, and used them as tools to fend off competition. Indeed, some scholars have argued that these patent laws enabled the concentration of U.S. industry that took place during the last two decades of the 1800s. (And in recent years, patents have evolved into a crucial wealth secret, as we shall discover in chapter 6.)

But our executive from the future would be dismayed to find that, in the early 1800s, most rich individuals were not inventors or industrialists, but landowners (and, in the South, slaveholders). How dull! Fortunately, in a country whose borders were rapidly expanding at the expense of Native Americans, there was also a great deal of money to be made in the acquisition of “new” land. America’s first president, George Washington, owned sixty-five thousand acres in thirty-seven different locations, and was thus at the time very likely the country’s richest man (it seems appropriate that America’s first political leader should also have been a master of wealth secrets). Even in bustling 1800s New York, elite society would have seemed, to a businessperson who had become unstuck in time, astonishingly feudal in character. The city’s richest families—the Morrises, Bayards, Livingstons, Van Rensselaers, Beekmans—were landed gentry, owning large estates along the Hudson River that were worked by tenant farmers. (After 1862, the situation became rather more democratic, as the U.S. government distributed over a billion acres of “public” land—not to mention the associated oil and mineral rights—via the Homestead Act.)

America’s early economic elite were not only estate owners; they also, in many cases, enjoyed government-granted monopolies (again, not so very different from the feudal Europe they had left behind). This system was partly a holdover from colonial times. But as far as wealth secrets went, it was probably the most exciting thing going, and our executive would have been very intrigued. In the early 1600s, for example, the English crown had awarded Sir Ferdinando Gorges a monopoly over fishing rights in New England, although protests from the colonists prevented it from being enforced. Efforts to enforce a monopoly covering the processing of salt, for the son of the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, were more successful. In the early 1800s, the patriarch of the Livingston family (one of New York’s semifeudal elites) obtained, via acquisition, a monopoly over all steamboat traffic in New York that was enshrined in state law. This was fabulously lucrative: in 1818, his profits from operating steamboats were $61,861 ($1.2 million today) on revenues of $153,694 ($2.9 million)—a 40 percent profit margin. This was on par with investing in LTCM, but without the market risk. The achievement was perhaps matched only by that of the Stevens family, who obtained a monopoly over rail travel in the state of New Jersey in the 1830s. In this instance, however, there was at least the pretense that this monopoly was something more than a gift to the well-connected Stevenses. The rail monopoly was held not by the Stevens family, but by a corporation—the Camden & Amboy Railroad—that had publicly traded shares. And the purpose of the monopoly was, in theory, to incentivize the development of desperately needed infrastructure (the monopoly rights attracted investors by all but guaranteeing a substantial financial reward). That said, the legislation was unambiguous in its generosity, establishing that “it shall not be lawful… to construct any other railroad or railroads in this State, without the consent of said companies”—the “said companies” being the Camden & Amboy.

The reason for this pretense was that the political climate in the United States was becoming increasingly hostile to the idea of government-awarded monopolies. In 1776, the laws of the newly independent state of Connecticut railed theatrically against “monopolizers, the great pest of society, who prefer their own private gain to the interest and safety of the country, and which if not prevented threaten the ruin and destruction of the state.” The laws of Massachusetts included an “Act to Prevent Monopoly and Oppression.”

Despite the rising hostility toward monopolies, there were a few individuals who soldiered on, using political connections and government-awarded monopolies to make their fortunes. Those who succeeded in these efforts have since come to be known as “political entrepreneurs.” Like the patent holders, their fortunes would not really compare to those achieved by the robber barons. But one or two political entrepreneurs achieved a fame that persists in the modern day.

One example is Leland Stanford, founder of California’s Stanford University. The young United States was eager to promote the development of infrastructure to connect the country’s fast-expanding territory. To encourage the construction of transport networks crossing state lines, the federal government offered subsidies and land. For instance, hoping to foster the creation of a transcontinental railroad, Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act, which offered railroad builders ten square miles of land—and loans—for each mile of track they constructed. The two groups that took up the offer were the Union Pacific, building west from Nebraska, and the Central Pacific, building east from California, and both had bribed Congress extensively to obtain the legislation (one railroad director had traveled east with some $100,000 in railroad stock to distribute to congressmen). The law’s passage set off a desperate and famous race between the two groups. In a sense, the legislation achieved its objective. Never was there a more eager attempt to lay track miles, since whoever laid the greatest number would obtain the most land and the most loans.

In another sense, the legislation was a disaster. The railroads were, in effect, incentivized to take circuitous routes to increase the track miles laid and to use the cheapest materials possible (even after the lines were “completed,” rebuilding them properly would take years). The railroad builders, flush with government support, also had a limited incentive to focus on financial stability. At the time, conflicts of interest were common, and the officers of the railroads created their own supply companies and bought materials from these companies at vastly inflated prices. For instance, six officers of the Union Pacific railroad created the Wyoming Coal and Mining Company, mined coal for between $1.10 and $2.00 per ton, and then had their railroad buy the coal at $6.00 per ton. Leland Stanford, leader of the Central Pacific Consortium, managed to win election to the governorship of California on the basis of his railroad and staunch anti-immigrant platform (his brother helped by handing out gold coins to voters). Stanford then set about obtaining an additional $15 million in loans from the California legislature, after which both consortia returned to Congress to demand yet more land.

When all was said and done, the two railroads had received forty-four million acres in free land and $61 million in loans from the U.S. government, and yet both were almost bankrupt. “I never saw so much needless waste in building railroads,” admitted Union Pacific’s chief engineer. This inefficiency made a number of individuals very wealthy, but perhaps the most farsighted was Leland Stanford. Eventually, the Union Pacific collapsed into scandal and was placed under close U.S. government supervision, but Stanford was able to turn his Central Pacific railroad around. The financial records of the railroad were “accidentally” lost, thus avoiding political complications, and Stanford used his control over California politics to prevent any competing railroads from entering the state. He was thus able to dominate rail traffic in California until 1900. It may not have been as good as a politically awarded monopoly, but it was close.

So there were some wealth secrets to be found, but mostly in landholding, slaveholding, or exploiting political connections. The latter were perhaps the most interesting, but rising antimonopoly sentiment was beginning to pose an obstacle to such methods. Worse yet, some of the government-awarded monopolies were about to come undone. This was, initially, a wealth secrets catastrophe. Our time-traveling executive, if she had not already been kidnapped by the Morlocks or shot by a hunter in the Michigan woods, might have given up in despair. But ultimately, these changes would set the stage for the rise of the robber barons.

THE EMANCIPATION OF COMMERCE

The wealth secrets catastrophe was, ironically enough, triggered by a struggle among the most conventional of early American elites—a slaveholder and a monopolist. On the one side was the Livingston family, with its steamboat monopoly in New York; on the other was Thomas Gibbons, owner of a large slave plantation in Georgia, who decided he would like to operate steamboats in New York as well. It was a war by proxy. Fighting for the Livingston side was Aaron Ogden, a governor of New Jersey and holder of a license from the Livingston family to operate a steamboat himself, running from Elizabethtown, New Jersey, to New York City. Fighting for the Gibbons side was Cornelius Vanderbilt, a physically immense, uneducated boat captain. The dispute itself was largely an accident. A minor business disagreement between Ogden and Gibbons had escalated into a matter of honor, and the aristocratic plantation owner Gibbons showed up at Ogden’s door, whip in hand, demanding a duel. Ogden had no intention of dueling and escaped by a back window. He also charged Gibbons with trespassing. Denied satisfaction, Gibbons decided he would try to bankrupt Ogden’s steamboat line—a style of combat more appropriate to the emerging postfeudal age. But it was still something that was just not done. Secure on their estates and in their monopoly privileges, America’s semifeudal elites had no love of competition. As a member of the aristocratic Stevens family wrote plaintively: “Gibbons runs an elegant steamboat for half-price… purposely to ruin Ogden.… Ogden has lowered his price and now Gibbons says he will go for nothing… did you ever hear of such malice?”

Since Ogden and the Livingstons held a legal monopoly, bankrupting the line would be no easy task. Fortunately, in Cornelius Vanderbilt, Gibbons had found a brave, willing, and sometimes violent champion. Over the course of his long career, Vanderbilt would reportedly beat into unconsciousness an army officer; a steamboat passenger who had sat in his seat; an unfortunate person named Hugh McLaughlin (the fact of the beating is recorded in a lawsuit, although not the circumstances); and a professional boxer who was running for political office (although this last tale may be apocryphal). In addition to relishing a fight, Vanderbilt was a superb captain. In his early days at the helm he would almost single-handedly rescue, through feats of deft piloting, a British vessel that had run aground; a U.S. vessel that had become trapped in ice; and a small steam ferry that was drifting out to sea in a storm.

Gibbons provided Vanderbilt with a steamboat to start a service that would compete (illegally) with Ogden’s ferry. Vanderbilt would vary the piers and timing of his boat’s arrival so that the New York authorities who showed up to arrest him for violating the monopoly were unable to catch him (presumably the annoyance to passengers was compensated for by lower prices). An attempt to seize Vanderbilt on the open water failed when he hid himself in a secret compartment on his vessel. To add insult to injury, Vanderbilt would often race directly beside Ogden’s vessel. One passenger wrote that “it was quite an interesting sight to see such vast machines, in all their majesty, flying as it were, their decks covered with well-dressed people, face-to-face, so near to each other as to be able to converse.” In 1821, the Ogden steamboat rammed Vanderbilt’s vessel, but Vanderbilt’s skillful sailing apparently enabled him to avoid serious damage.

In the meantime, Gibbons began a legal attack on the Livingston-Ogden monopoly as well. He lost at first, but appealed his case, challenging the monopoly’s validity all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1821, Vanderbilt, having at last been caught by the New York police while running his illegal steamboat service, added a case and appeal of his own. In 1824, the Supreme Court ruled on the case of Gibbons v. Ogden. It was the first-ever ruling regarding the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause, which gave the federal government sole authority to regulate commerce that crossed state lines. The Supreme Court ruled that attempts by the state of New York to enforce the Livingston-Ogden monopoly ran counter to the Constitution, because the route crossed state lines. According to the Constitution, only the federal government had such authority. Hence Gibson and Vanderbilt would be free to operate their line and compete as they wished.

This ruling opened a floodgate through which competition came surging. The surge reached far beyond the Hudson River, swamping many a political entrepreneur. Monopolies that lay entirely within a state—the Camden & Amboy Railroad of New Jersey, for instance—could continue to be upheld. But for interstate commerce, monopolies were abolished. Fares for steamboat travel on the Hudson immediately plummeted to less than half the monopoly rate. The number of steamboats registered in New York increased from six to forty-three in a single year. The impacts were felt nationwide. By the following year, steamboat traffic on the faraway Ohio River had doubled; the year after that, it had quadrupled. Legal historian Charles Warren called the court’s decision “the emancipation proclamation of American commerce.” A biographer of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall claimed that the decision, by encouraging interstate transport and business, “has done more to unite the American people into an indivisible nation than any other force in our history, excepting only war.” A newspaper of the time, the Evening Post, was even more extravagant in its praise, calling the decision “one of the most powerful efforts of the human mind that has ever been displayed from the bench in any court.”

The ruling helped to unleash productivity and progress. From 1830 on, U.S. economic growth rates rose from the 3 percent average rates of the 1820s to between 5 and 6 percent per year on average (in inflation-adjusted terms) and remained there, with a few interruptions, until nearly the end of the century. In 1830, at the time of the ruling, average U.S. income was two-thirds the level of U.K. income. By 1860, Americans were, on average, as rich as the British. While the American Civil War (1861–1865) caused great loss of life, the forty years that followed it would witness the most rapid sustained economic growth achieved by any country in history, and probably not surpassed until the post–World War II rise of Japan. Between 1870 and 1900, the U.S. population rose from 40 million to 76 million while economic output increased by three times and per capita income doubled.

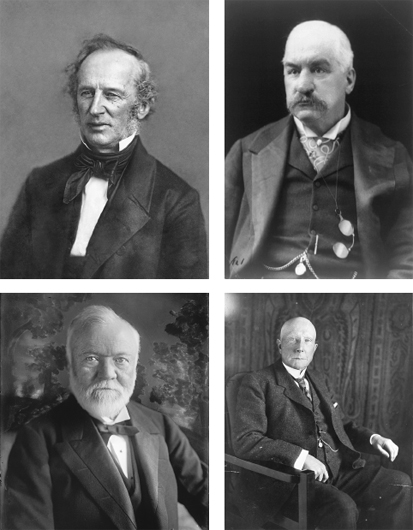

The robber barons (clockwise, from top left): Cornelius Vanderbilt; Pierpont Morgan (the famous nose has been retouched); Andrew Carnegie; John D. Rockefeller. (Vanderbilt: “Cornelius Vanderbilt Daguerreotype2,” restored by Michel Vuijlsteke. Original image Mathew B. Brady / Library of Congress. Licensed under public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Morgan: Library of Congress. Carnegie: Library of Congress. Rockefeller: Harris & Ewing / Library of Congress.)

Onto this stage of cutthroat interstate competition and rising prosperity would stride the robber barons, and they would transform the U.S. economy. The boat captain Cornelius Vanderbilt, though initially only a pawn in the Gibbons v. Ogden battle, would pave the way. Pierpont Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Jay Gould would follow, launching their careers during the Civil War and after. Their efforts would produce industrial giants towering over the small-business landscape of the time: Standard Oil, International Harvester, U.S. Steel, General Electric, J.P. Morgan, and American Telecom and Telegraph, among others. Many of these famous corporate names continue to thrive today. The robber barons would build monuments to their wealth that a century later would continue to define the tourist map of New York City: Carnegie Hall, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the first board meetings were held in Pierpont Morgan’s home), the Museum of Modern Art (developed by Rockefeller’s wife), Rockefeller Center (developed by Rockefeller’s son), and the Museum of Natural History (Pierpont Morgan was one of the founders), among others. Innovation flourished in this competitive economy, and by the 1890s a well-off American home might include electric lighting, an electric stove, an electric washing machine, and an electric doorbell. But the robber barons would bring this era of cutthroat competition to a close, while in the process making themselves spectacularly wealthy.

PIERPONT’S RETIREMENT

In contrast to the political entrepreneurs, the robber barons did not rely on politically awarded monopolies or subsidies to make their money. Nor were they particularly interested in innovation (“Pioneering don’t pay,” Andrew Carnegie famously said, after an attempt to use a new process for manufacturing steel rails went badly awry). They discovered a new wealth secret—one for a postfeudal age—and their fortunes would greatly eclipse those of political entrepreneurs like Stanford.

While the robber barons would end their lives luxuriating in gilded bathtubs and using large-denomination bills to wipe their bottoms just because they could (OK, I made that last bit up), most were not born rich. Vanderbilt lacked even a basic education. “You will reccolect the Bellona must be halled up weather you have hir 12 feet longer or no,” he once wrote to Gibbons, pleading for an extension to his boat and demonstrating a creative approach to spelling and grammar. Jay Gould began his life in poverty, abandoned at age thirteen by his father with only his clothing and fifty cents (about fifteen dollars today) to make his start in the world. John D. Rockefeller’s father was well-off enough to extend loans to his son at several crucial points, but was at the same time a con man who maintained a second family during long absences from the Rockefeller home. Andrew Carnegie’s father, a Scottish weaver, had prospered initially but had fallen on hard times during Carnegie’s early childhood.

Pierpont Morgan was the exception, as his father had established a thriving banking business. In 1837 young Pierpont was sent abroad to Göttingen University in Germany to study, noting proudly that he furnished his student rooms in “royal splendor and Eastern magnificence.” After his younger brother died, Morgan became heir apparent for the family’s London-based bank. His first memorable commercial venture, however, came when he took a starter job at another bank and boldly but somewhat randomly bought a boatload of Brazilian coffee that had arrived in New Orleans without a buyer (Morgan happened to be visiting the city at the time). He flipped it for a quick profit, but this terrified his superiors, who had given him no authorization to buy anything. Morgan was clearly better suited to being his own boss, and at the age of twenty-four he and a cousin set up a banking partnership in New York. In 1861, Morgan took part in another controversial deal, financing a scheme to buy guns from a U.S. government warehouse at $12.50 each, upgrade them slightly, and then resell them to a U.S. general in the field at $22 apiece. Because the Civil War had by then broken out and the U.S. Army was desperate for weapons, this looked a lot like war profiteering. For one reason or another, Morgan pulled out of the deal early, but not before making a commission of more than 25 percent.

Morgan soon found himself involved in another questionable wartime venture. As noted previously, during the war, the North had issued the first public paper currency, the so-called greenback. This was a new phenomenon (and the survival of the issuing government was by no means assured), so no one knew quite how far to trust these paper notes. Hence the exchange rate between greenbacks and gold fluctuated depending on the progress of the war (there was always a chance that the only thing of value in the northern treasury would turn out to be its gold holdings). Pierpont Morgan and a colleague stealthily accumulated gold worth over $2 million, financing further accumulation by borrowing against their initial hoardings. They then shipped $1.15 million in gold to London and announced publicly that they had done so. This created a temporary shortage, driving gold prices up. Morgan earned $66,000 ($1.8 million today). It was something of a speculative gamble, and it enraged his father. It also was seen by critics as an unpatriotic attempt to profit from the northern government’s wartime monetary troubles.

Morgan at this time suffered a personal tragedy. He had married Amelia Sturges, nicknamed “Memie,” in 1861. His father disapproved, in part due to Amelia’s obvious ill health, but conceded that romance was blossoming: “she of all others possesses those qualities of heart and mind best calculated to make his life happy.” Shortly after the wedding, Amelia was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and she died within six months. Morgan’s father, upon learning the news, mixed sympathy with the need to reestablish that father knows best: “I have, as you know, taken a gloomy view of our dear Memie’s case, but was wholly unprepared for the sudden termination of it,” he wrote. Four years later, Pierpont Morgan married Frances Louisa Tracy (nicknamed “Fanny”), this time with his father’s approval. She was perhaps a more sensible choice, both in terms of her health and family background. But she did not like either travel or city life, two things that Morgan adored.

This personal turmoil notwithstanding, and despite embarking on two long honeymoons in a five-year period, Pierpont Morgan’s income had by the mid-1860s risen to about $60,000 per year ($885,000 today). Respectable, although still far from robber baron territory. Vanderbilt, who had an earlier start, had reached an annual income of $680,728 ($10 million) by 1863. Still, as the son of a rich man, Morgan was already very well-off. In 1871, at the age of thirty-three, he decided to retire, but was talked out of it by his business partners. He chose instead to leave the banking partnership with his cousin and found a new company, Drexel, Morgan, based out of New York and Philadelphia.

Exhausted by these labors, he then set off on holiday for fifteen months, traveling to Rome and Vienna, and sailing up the Nile.

THE BANKRUPTCY PROBLEM

Any feeling of well-being and relaxation Morgan may have gained from his holiday travels evaporated upon his return—all thanks to the railroads. Railroads, as noted, were America’s largest commercial enterprises at the time. Investment bankers like Morgan, who made a living by arranging large-scale financing, could not stay away. There was, however, a serious problem: railroads went bankrupt with great frequency.

The economics of infrastructure could be blamed for these insolvencies. Not only railroads but also steamboat lines operated with very high fixed costs (costs of buying train engines, cars, or steamboats). By contrast, variable costs (the cost of seating an additional passenger on a train or boat that was already going to run) were very low. This meant that a steamboat or railway that was trying to lure a passenger away from a rival would benefit from winning the additional passenger even if that passenger paid next to nothing. Hence rival steamboats or railroads would, when in competition, reduce their prices almost to zero. (When competing against Ogden, Vanderbilt would sometimes charge nothing, hoping to make money via onboard drinks sales, like an early Ryanair.)

Most types of businesses would not do this. A hamburger shop that reduced its prices to next to nothing would lose more money the more hamburgers it sold—so it would stop selling so many hamburgers. In the transport business, however, by cramming more passengers onto a steamboat that was already going to sail, or a train that was already going to run, the owners would make more money, even if these passengers were paying only for drinks. This was great for passengers, but bad for the steamboat lines. Because of the high fixed costs associated with buying steamboats in the first place, steamboat companies tended to have a lot of debt. The situation was even more extreme for railroads, which not only had to buy the engines but also the track. Given their high debt burdens, if steamboat lines or railroads charged too little for too long, they would be unable to meet their interest payments and thus go bankrupt. The result of such competitive dynamics was that, unlike hamburger stands, it was very difficult for either railroads or steamboat lines to divide a market. Eventually, all competitors on a particular route except one would usually go bankrupt. It was a winner-takes-all struggle. (And it’s the same reason why airlines tend to bankrupt themselves with such frequency in the modern day.)

People like Vanderbilt thrived on such contests. For them, the reward was worth the risk. Once they had bankrupted their competitors, they would enjoy a monopoly—at least, as long as another steamboat or railroad did not enter the market. And, while they were enjoying this monopoly, they could charge exorbitant fees. Potential competitors might be attracted by the resulting profits but would think twice before entering: not only would they face a long period of low earnings while the two steamboat companies battled it out, but there was a risk that the new entrant would be the one to go bankrupt. Hence a steamboat owner could reap a fair amount of profit—real profit, economic profit—without worrying about competition.

Within a year after the Gibbons v. Ogden ruling, Vanderbilt had bankrupted Aaron Ogden—the former New Jersey governor and U.S. senator—sending him to debtor’s prison (briefly, until his political connections got him out). Vanderbilt then moved from steamboats into railroads, where he once again attempted to bankrupt all comers or—better yet—threaten competitors with bankruptcy and then acquire them at knockdown prices. By the end of the 1860s, Vanderbilt had by such means gained control of all the railway lines leading into New York City. This monopoly on New York rail traffic was fabulously lucrative and by 1870 was paying the largest dividend of any company in U.S. history. Vanderbilt built the Grand Central Depot, the forerunner to today’s Grand Central Station, located at Forty-Second Street in Manhattan (because that was as far south as noisy, polluting steam trains were allowed to travel). He then linked his two New York lines together, via the Spuyten Duyvil railroad, adding more flexibility to his network. The New York & Hudson Railroad soon stretched to over 740 miles, with another 300 miles of network branches. A New York Times article compared Vanderbilt to the German barons who had extracted tolls from traffic on the Rhine—a comparison that gave rise to the term “robber baron.”

But if Vanderbilt was worried about the criticism, he didn’t show it. To blow off steam, he would race his horse-drawn wagon against all comers down the streets of New York, sometimes accidentally running down pedestrians. At the age of sixty-nine, he crashed into his rival during one of these races and was thrown from the wagon, landing on his head. From such a trivial accident he recovered quickly. By this time, to the public, Cornelius Vanderbilt was known simply as “the Commodore.” His rapidly expanding rail network was so lucrative that, according to some estimates, he was by that point the richest American who had ever lived. The press of the day estimated his fortune at between $85 million ($2 billion today) and $150 million ($3.4 billion). But these were only guesses, as Vanderbilt, seeking to retain an edge over market manipulators, tended to keep his books in his head, and hid his holdings under other names.

Regardless of exactly how much Vanderbilt was worth, the winner-takes-all contests in the railroad business were clearly delightful for the victors. Vanderbilt was one of these winners. Jay Gould, another railway tycoon, was another. The problem, from Pierpont Morgan’s perspective, was that there were also losers. One of them was a political entrepreneur, Jay Cooke, who had enjoyed a lock on the financing of U.S. government debt. In 1873, Cooke used his vast fortune to diversify into railroads. Here his political connections were of less value, and he miscalculated badly, eventually bankrupting not only his railroads but himself. This bankruptcy touched off a financial panic, and by 1876 one half of the country’s railroads were insolvent.

Pierpont Morgan observed this growing financial turmoil with dismay. To drastically oversimplify a complex business, the incentives of a banker who finances steamships or railroads are very different from the incentives of the owners of those businesses. Vanderbilt might have been willing to risk everything on winner-takes-all contests, knowing that if he won, the profits would more than justify the risks. A banker, by contrast, makes loans or underwrites bonds. No matter how well a borrower does, the value of the loan never rises. The same amount is always paid back. Hence the banker does not want winner-take-all contests. Instead, a banker wants all the competitors to stay in business and to reliably pay back their loans. “The kind of Bonds which I want to be connected with are those which can be recommended without a shadow of doubt, and without the least subsequent anxiety, as to payment of interest, as it matures,” wrote Pierpont Morgan.

With the nation’s railroads lurching into bankruptcy, Pierpont Morgan again considered retiring—who needed such aggravation?—but consoled himself by taking his family on holiday to Europe for the summer of 1876. He also began to devise a scheme to control railroad competition, a scheme that had first begun to bear fruit in the early 1870s. Drawn into a contest between Vanderbilt and the rising tycoon Jay Gould, Morgan came to Vanderbilt’s aid with a huge financing package. He then took payment in power, becoming a board member of the newly merged railroad.

This maneuver gave Morgan significant control. As a board member, Morgan could oversee the actions of management and stand up for the bankers’ interests. Because Morgan was also the main agent arranging financing for the railroad, his influence was significant. “Your roads belong to my clients [the bondholders],” Morgan once lectured a recalcitrant railroad president who did not wish to follow orders. And what Morgan wanted was for railroads to avoid competing with each other, and thus to reliably pay their debts. When, in the early 1870s, the directors of the Chicago & Alton Railroad wanted to add an extension to Kansas City, Morgan objected strongly: “we have had for several years past a fever for building and extending competitive lines, and nearly every company that has undertaken it has suffered accordingly,” he explained. Nothing good ever comes of competition, he admonished. At least, not from the banker’s perspective.

When Cornelius Vanderbilt died, Morgan attempted to broker an alliance between the railroad tycoon Jay Gould and Vanderbilt’s son. In 1880, Morgan’s bank underwrote the public offering for Vanderbilt’s railway, the New York Central. In the process, Morgan put himself on the railroad’s board of directors. He also brokered a meeting between the heads of the railroads competing with the New York Central “with a view of making permanent running arrangements” to divide up traffic (this was not at the time illegal). It did not work. Jay Gould, who preferred winner-takes-all contests, quickly went back to competing. But it was a start.

In 1884, Morgan’s father attempted to broker a truce between the two largest railroads in the United States, the Pennsylvania and the New York Central (the latter then run by Vanderbilt’s son). Morgan senior implored the two networks to give up their “absurd struggle for preeminence” but was unsuccessful. In 1885, Pierpont Morgan would succeed where his father had failed. He invited the heads of the railroads onto his yacht and sailed up and down the Hudson while negotiations continued—the implicit threat being, presumably, that they would continue to sail, imprisoned in luxury, until a deal was reached. The head of the New York Central was singing from Morgan’s hymn sheet: we need a “community of interest” to avoid “ruinous” competition, he urged. Still, it was not until 7 p.m., when the yacht finally docked at the Jersey City pier, that a deal was agreed upon to divide the market and avoid competing on shipping rates. There was nothing illegal about such cartel agreements at the time, and some of the press of the day celebrated the agreement. “To railroads, least of all, would our people like to see applied the principle of the survival of the fittest,” wrote the Commercial and Financial Chronicle (championing the banker’s doctrine of the survival of everyone).

Shortly thereafter, Morgan rescued the bankrupt Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. Rearranging the company’s financing, he created a “voting trust” that would represent the interests of the shareholders and oversee the actions of managers. This arrangement gave Morgan even greater control than serving on the board, and would become a key mechanism for him to exert his influence over the companies he financed. Morgan used his new powers to replace the management and oversee the restoration of the financial health of the railroad.

With these deals, Pierpont Morgan was on his way to becoming a rich man and climbing out of his father’s shadow. He bought his first yacht, the Corsair Mark I, in 1880. But as far as preventing the nasty business of competition goes, Morgan had only just begun. Perhaps to celebrate his early victories, he vacationed in Europe, visiting Rome with his father. He left his wife, who had had enough of traveling, at home.

SIZE MATTERS

The freeing up of competition occasioned by the Gibbons v. Ogden ruling meant that politically awarded monopolies were becoming increasingly scarce. But the rise of the railroad tycoons hinted at a new possibility. By 1887, this possibility had been given a name: a “natural monopoly.” The political economist who coined the phrase in a lecture to the inaugural meeting of the American Economic Association did not go into much detail, applying the term to businesses with average costs that declined as the business grew. But soon, the term was being used to explain why one company, Western Union, had come to dominate the U.S. telegraph business nationwide. Both Vanderbilt and Gould were involved with Western Union’s rise to dominance, and had made a good deal of money in the process. Only about 3 percent of the U.S. population were telegraph users at the time, so it was not that lucrative (most of Vanderbilt’s money came from the railroad business). But Western Union’s natural monopoly made for some excellent profitability. The day when someone might achieve a similar feat of nationwide dominance with the railroads did not appear that far off. Under men like Vanderbilt and Gould, the railroads were rapidly consolidating into interlinked networks that controlled large geographic regions of the country. Indeed, by the late 1890s, the national network would be dominated by six major systems.

Having a natural monopoly was not quite so good as having a legislated monopoly. As with the operator of a steamboat line, one still had to worry about potential competition. (Indeed, some economists prefer not to use the word “monopoly” to describe such businesses, because they still face competitive pressure. For more on this debate, see this volume’s endnotes.) I have said, for instance, that Vanderbilt enjoyed a “monopoly” on New York rail traffic. But if he squeezed New Yorkers too hard, or ran his business inefficiently, someone else might build a new rail line into the city. Of course, given the risks of competing with Vanderbilt, the railroad could comfortably earn a lot of profit before there was any likelihood of that happening.

And thus these new natural monopolies, even if they faced competitive pressure, were attractive business propositions. Indeed, these natural monopolies were in some ways more attractive than legislated monopolies, because the Gibbons v. Ogden ruling did not apply. There might be some limit to the prices that could be charged. But, crucially, there was no limit to the scale. It was theoretically possible to grow a natural monopoly business that would dominate an industry across the entire United States. And indeed, after Western Union achieved this very feat, it was no longer just theory.

The problem was, this wasn’t easy. Businesses like Western Union, the railroads, and later the telephone networks enjoyed a wealth secret advantage now known as “network effects,” as we shall discover in chapter 6. Most businesses in most industries didn’t have such advantages.

The advantage most of the robber barons had to work with was a more general principle known as “economies of scale.” Turning scale economies into a wealth secret required some ingenuity. But first, the basics: a business is said to enjoy economies of scale if average costs fall as size increases—in other words, if the business’s activities become more cost-effective when larger quantities of labor or capital are employed. For instance, while some extremely high-end automobiles are even today made by small teams of people, such handcrafted supercars are only bought by people for whom money is no object. It is much cheaper to manufacture automobiles using assembly lines involving hundreds of workers (or, more recently, hundreds of robots) performing specialized, repetitive tasks.

Economies of scale mean that even if a car manufacturing business is obviously profitable, it is still hard to copy, because one needs a lot of labor and capital to do it efficiently. This fact limits the number of competitors that will enter the automobile market, enabling some profitability for those in the market (the profits on offer must be large enough to justify a substantial up-front investment by new entrants). If the economies of scale are extreme, the number of competitors could be very small and profits potentially very large. For instance, there are only two jumbo jet manufacturers in the world (Airbus and Boeing) because building a jumbo jet requires a tremendous mobilization of people, equipment, and technology. For a third player to get involved, the profits of these two companies would have to be extraordinarily high. The new entrant would enter with the intention of bankrupting one of them, and would need to factor in not only the huge costs of establishing a manufacturing operation on the necessary scale, but also a long period of low profits necessary to drive one player into bankruptcy, and furthermore the very real risk that Boeing or Airbus would in response raise their game and the new entrant would be the one bankrupted. Hence Boeing and Airbus can earn a decent return, or make a lot of commercial mistakes, without worrying about attracting competition.

But jumbo jets are unusually large and complex items. For most industries, economies of scale are not really a wealth secret of a magnitude that would interest us. Even in the automobile industry, the profits of U.S. auto manufacturers have been eroded to the point that the industry frequently requires government bailouts. The troubles of the auto sector stem partly from the fact that economies of scale are generally offset by “diseconomies” of scale. Larger firms tend to be more complex, more bureaucratic, and more difficult to manage efficiently (a case in point being railroads like the Union Pacific, the business affairs of which were so complex that managers were able to steal money from right under the noses of investors). Hence turning economies of scale into wealth secrets was no simple task, especially in a large national market such as the United States. This was doubly true in the 1800s, because management, accountancy, and other crucial business control techniques were still in their infancy. Diseconomies of scale in most industries probably set in fairly quickly. As a result, anyone who wanted to turn their business into a natural monopoly in the 1800s was probably going to have to find a way to change the fundamental economics of that industry.

The man who without question was most successful in doing so was John D. Rockefeller.

ROCKEFELLER RIDES THE RAILS

John D. Rockefeller’s early family life defied conventional norms of morality. Rockefeller’s father, a con man generally known as “Big Bill,” made his living selling fake medicine. Big Bill was tall, handsome, a superb marksman, a natural athlete, and a capable ventriloquist. He also spent several years posing as a deaf-mute, communicating via a small slate and chalk, apparently because he felt it made his sales pitch more credible. Big Bill seduced Eliza Davison, a pious farmer’s daughter from Richford, in western New York. He married her, but failed to rid himself of his girlfriend, Nancy Brown. Big Bill lived with the two women in a small homestead near Richford. Officially, Nancy was the housekeeper. Big Bill had four children, two by each woman, in the space of two years. One of these children was John D. Rockefeller.

His was a schizophrenic childhood. On the one hand, Rockefeller seemed in awe of his father. “I come of a strong family, men of unusual strength, a family of giants,” he would later say. Yet Big Bill would vanish unexpectedly from the home, for weeks at a time, leaving his family to survive on only a line of credit from the local grocer. When he returned, he would appear in fine clothes, riding a new horse, sometimes driving a new carriage, sometimes with diamonds on his shirtfront. He would pay off the grocer theatrically, drawing large-denomination bills from a thick wad. “He made a practice of never carrying less than $1,000 [about $32,000 today], and he kept it in his pocket,” Rockefeller remembered. Big Bill was then the life of the party, frolicking with his young sons, until he vanished again, throwing his family back into uncertainty, dependent on the generosity of the grocer. Young John D. Rockefeller, as the eldest son, was forced to shoulder adult responsibilities from an early age. He also began to take on his mother’s piety.

When Rockefeller was a child, the family (sans Nancy) moved to Moravia, a few miles away. Big Bill used money from his sales of fake medicine (there were also rumors of horse theft) to start a lumber business. This period of near respectability ended when Big Bill was accused of raping his new housekeeper, a woman by the name of Anne Vanderbeak. For some reason, the case never went to trial. But as a result of the scandal, the family moved again, this time to Owego, on the Pennsylvania border. Big Bill soon wanted to move farther away. He chose the Cleveland area, where he deposited his family with some of his relatives, paying his sister $300 annually (about $10,000 today) to board his wife and children. He then began a secret second life, marrying a seventeen-year-old Canadian girl and settling with her in Nichols, New York. About three to four times a year, he would reappear unexpectedly in Cleveland, still the charmer, usually brandishing money. Thanks to these irregular infusions of cash, John D. Rockefeller was able to attend good high schools (which were scarce in rural America at that time) and even had visions of attending college. In the end, though, he was forced to drop out suddenly, and never finished high school. The historian Ron Chernow speculates that Big Bill, stretched thin by the expense of maintaining a second family, had arbitrarily cut his son off.

Young Rockefeller frequently declared to his school friends that he would one day be rich. Friends from New York and Ohio recall him vowing to attain a net worth of $100,000 (more than $3 million today), although Rockefeller, in later years, would deny having said any such thing. Perhaps this youthful desire reflected a wish to emulate his father’s charismatic habit of carelessly revealing a roll of large-denomination bills. Or perhaps he was traumatized by the uncertainty of not knowing whether the next grocery bill would be paid. Quite possibly both. In any event, cast out of high school, Rockefeller engaged in a now-legendary job hunt, visiting every potential employer in Cleveland to ask for work as a bookkeeper. When this failed, he started at the top of the list and began again, making applications in person from early morning until late afternoon, six days a week for six consecutive weeks. Big Bill suggested that if the job hunt didn’t work out, John D. could come back home. Rockefeller later said he felt a “cold chill” at hearing these words. He was finally hired as a bookkeeper at a trading company on September 26—a day he continued to celebrate as “Job Day” for the rest of his life. He was sixteen years old.

Through this position Rockefeller came into contact with the first large sum of money he had ever seen in his life, a banknote for $4,000 (about $111,000 today). He reported opening the office safe and gazing open-mouthed at the bill several times over the course of the day. But this love of money was perhaps the only thing he had in common with his father. Young Rockefeller was hardworking and disciplined, arriving at the office at 6:30 a.m. and rarely leaving before 10:00 p.m. (although he took a break for dinner). From his modest salary as a bookkeeper, he gave to charity, at first 5 percent and then 10 percent of his wages. With his father absent, Rockefeller had been raised mainly by his mother, a strict disciplinarian and a pious Baptist. He took to the faith and was from his early days in Cleveland an active member of the church there. He soon became a trustee of the church, a Sunday school teacher, and an unpaid clerk, attending Friday evening prayer meetings and services twice on Sunday.

And yet it was his father who proved crucial to young Rockefeller’s start in business. As a sort of a going-away present, Big Bill, before absconding to live with his younger family, built his Cleveland family a house. He charged John D. Rockefeller with overseeing the construction. When Rockefeller mentioned that he needed $1,000 to start up a trading company with his friend, Big Bill gave it to him. With less than three years of experience in the working world, Rockefeller became his own boss.

Soon the trading company launched a side venture in oil refining that would come to define Rockefeller’s career. Oil refining was a booming sector. The lamps of the day were powered by whale oil. This was an improvement on the Roman olive oil lamp, but prohibitively expensive for all but the rich. Whales generally did not wish to become lamp fuel, so catching them was costly. When large deposits of petroleum were found in Pennsylvania—and, unlike the whales, made no effort to swim away—this discovery offered a potential source of cheap lighting for the masses. But first, the oil needed to be refined into kerosene.

It was a rough-and-tumble, unregulated business. Traveling to the Oil Region of Pennsylvania to secure supplies for his refinery, Rockefeller found that oil barrels were carted from the drills to the railroads by teamsters in wagons. The unpaved, rutted road over which they traveled was covered in a black muck of spilled oil barrels. The roadside was dotted with the corpses of horses that had died on the job, their hair and hides eaten away by petrochemicals. The situation on the rivers was perhaps even worse. “Lots of oil was lost by the capsizing of barges and smashing of barrels in the confusion and crush of the rafts,” Rockefeller later explained. Indeed, there was so much oil in the water that in 1863, the Allegheny River caught fire. At the refineries, things were not much better. If you have seen a modern refinery, you may have noted that each tank is surrounded by an earthen bank to catch spilled oil. At the time, this safety feature had not been developed, and a fire in one oil tank would quickly spread to others, developing into an uncontrolled blaze. Refinery fires became so common that these operations were banned from inside the Cleveland city limits. Eventually, desperate oil producers began posting signs that read “Smokers will be shot.” Meanwhile, gasoline, at the time a useless by-product of crude oil, was burned or simply dumped on the ground. “The ground was saturated with it, and the constant effort to get rid of it,” said Rockefeller.

One reason refining was such a slipshod affair was that it was lucrative, and thus drew in new refiners by the droves. “In came the tinkers and the tailors and the boys who followed the plow, all eager for this large profit,” said Rockefeller. Many of these rookie refiners possessed little more than a single trough, a tank, a still to boil the oil, and barrels to put it in. Some of these operations handled no more than five barrels a day. Demand for kerosene was so great at first that even such inefficient small producers could make some money. But soon so many small refineries had piled into the business—not only in Cleveland but also in New York, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia—that competition was fierce. Rockefeller needed to stand out. After he added another business partner, Henry M. Flagler, who brought to the venture a loan of $100,000, he was beginning to make progress. He was gaining a size advantage over rivals.

Whether or not Rockefeller initially understood that larger operations would be more efficient, his mind-set was ideally suited to the exploitation of cost advantages. His discipline and his fascination with money were evident in his relentless focus on cost control. Rockefeller famously managed, to his obvious satisfaction, to reduce by a single drop the amount of solder used in sealing kerosene cans. He constantly double-checked the work of his accountants, once discovering that 750 barrel stoppers had been lost, for which he demanded an explanation. He devised schemes for using the waste products of the refining process. And on one occasion, when he heard that a buyer had secured a delivery of oil at below market price, he “bounded from his chair with a shout of joy, hugged me, threw up his hat, acted so like a madman that I have never forgotten it,” recalled one acquaintance.

The problem was, Rockefeller was far from the only go-getter in the oil business. Many of his competitors were, like him, adding scale. With larger operations, they began to refine the business of refining, making improvements such as mechanization, better production processes and still designs, and the use of acids and other chemicals to improve the final product. Rockefeller needed an edge—and he found it not in technological advancement but in innovative contractual arrangements. Rockefeller—or perhaps his business partner, Flagler—came up with the idea of making volume-shipping agreements with the railroads. For instance, Rockefeller signed an agreement with a Vanderbilt railroad that gave his refinery a 30 percent discount in exchange for a guarantee to ship at least sixty tank-car loads of oil each day. Another agreement, this time with Jay Gould’s Erie railway, offered rate concessions in return for volume guarantees and was sealed with an exchange of stock. Such deals would be illegal today—and indeed caused an outcry when eventually made public—but were wholly permissible at the time. These deals “leveraged” Rockefeller’s existing size advantages, giving his refinery an advantage in shipping costs to augment its lower production costs. By this point, he clearly understood that bigger was better. “The larger the volume the better the opportunities for the economies,” Rockefeller explained, “and consequently the better the opportunities for giving the public a cheaper product without… the dreadful competition of the late ’60s ruining the business.”

The agreement with the Vanderbilt railroad, involving the promise of sixty tank cars loaded with oil each day, proved to be a breakthrough. Because Rockefeller’s refinery did not have the capacity to fill sixty tank cars with oil each day, he was evidently agreeing to coordinate shipments from other refineries. This arrangement was a huge advantage for the railroads, which could then dispatch trains composed solely of oil tankers, rather than a mix of cars for a mix of cargoes. Working with Rockefeller, the railroads were thus able to reduce their active fleet of railcars from 1,800 to 600. The associated cost savings probably more than justified the discount they gave Rockefeller’s refinery. Perhaps even more importantly, this innovative deal probably got the railroads thinking, What if Rockefeller could guarantee even larger shipments of oil? Wouldn’t that be even better for us?

It’s unclear who first came up with this idea. The answer is quite literally lost to history: the Rockefeller Foundation has made Rockefeller’s personal papers available to historians, but one year is missing: 1872. That was the year Rockefeller succeeded in changing the economics of the oil refining industry. The mechanism by which Rockefeller rose to dominance was, on the face of it, straightforward: he suddenly acquired twenty-one of the twenty-six oil refineries in Cleveland, gaining a near monopoly on oil refining in the region and control of one-quarter of the refining capacity of the entire United States (some historians say twenty-two of twenty-six, but that is really the only disputed point). The question is how he accomplished it.

Rockefeller had reorganized his business as Standard Oil Company in 1870, and it was one of the first joint-stock corporations outside the railroad sector. The great advantage of such a corporate structure, for Rockefeller, was that it enabled acquisitions at a low upfront cost. To be specific, Rockefeller could buy small, inefficient refiners by offering them stock in Standard Oil as compensation.

“Well,” you might think, “that doesn’t sound so hard—he achieved monopoly by acquisition.” But in point of fact, this strategy almost never works (if it did, there would be many more monopolies). The reason it almost never works is that once one company is obviously on the path toward industry dominance, the owners of other companies in the industry will tend to turn down acquisition offers because they expect the removal of competition to result in higher prices, which will benefit every firm in the industry that remains standing. So they will try to hang on, even operating at a loss, in the expectation that better times are to come. (This kind of behavior deeply annoyed Rockefeller: “oftentimes the most difficult competition comes, not from the strong, intelligent, the conservative competitor, but from the man who is holding on by the eyelids and is ignorant of his costs, and anyway he’s got to keep running or bust!”) In sum, unless a company can actually bankrupt its rivals (like the steamboats and railroads Vanderbilt owned), these rivals, especially the last of the rivals, are unlikely to sell out.

So the question was, how had Rockefeller managed to make these acquisitions happen? In “natural monopoly” businesses, weaker competitors that are headed for bankruptcy will sometimes sell out to the industry leader. But oil refining was not obviously a “natural monopoly” type of business. Rockefeller needed a way to change this. He did so with a scheme that came to be known as the South Improvement Company: essentially, a cartel. Yet unlike most cartels of the day, which revolved around gentlemen’s agreements not to compete (like the railroad agreement brokered by Pierpont Morgan on his yacht), this cartel would include a number of innovations. One was that all the cartel members would invest in a holding company, called the South Improvement Company, which would in turn invest in all of the members, thus giving all participants a financial incentive to uphold the agreement. Second, the cartel would not only involve three railroads (the Pennsylvania, the New York Central, and the Erie) that among them controlled all rail traffic in Cleveland, but also several oil refiners, of which Standard Oil would be the largest. Third, the railroad members of the cartel would raise their shipping rates—which is, of course, the point of any cartel. But at the same time, the oil refinery members of the cartel would receive rebates. Hence, while their shipping rates might go up, their cost advantage over rival refineries would increase (the rebates were as much as 50 percent in some cases).

But the most extraordinary element of the cartel agreement was the following: oil refiners that were not cartel members, and shipped oil over the railroads, would also be assigned rebates. But these rebates would go, oddly, to the cartel members. This agreement would transform the economics of oil refining. For nonmember refineries, economies of scale would be erased: the more oil they shipped, the more rebates they would hand to their competitors. It was a murderously anticompetitive arrangement.

The advantage to the railroads was that Standard Oil agreed to act as an “evener.” Railroad cartel deals often broke down because one member, eager to get business, would secretly reduce its prices below what the cartel had agreed. Standard Oil would police such behavior, by allocating its shipments among the railroads so that the Pennsylvania Railroad would get 45 percent of all the oil shipped from Cleveland, and the Erie and New York Central would get 27.5 percent each. If one railroad lowered its prices and raised its share, Standard Oil would reallocate its shipments to the other railroads to make up the difference. Hence none of the railroad members of the cartel would have any incentive to cheat. For this to work, of course, Standard Oil had to be by far the largest refiner in Cleveland, which is why the railroads were willing to go along with the anticompetitive rebate scheme.

Oddly, however, the South Improvement Company deal never went into effect. It was not illegal, and yet when the deal was made public, the backlash was tremendous. Oil producers responded with an embargo, knowing that it would be bad news for them if one company came to dominate oil refining. Lobbying by the intended victims in the refining sector was also overwhelming, and the Pennsylvania legislature soon revoked the South Improvement Company’s charter. The proposed cartel was never put into practice.

So how did Rockefeller achieve his buyout of nearly all the refineries in Cleveland? Apparently, by using the prospect of the deal to threaten these companies with bankruptcy. The brilliance of the South Improvement Company deal was that, had it come into force, any small refineries that held out in the face of Standard Oil’s rising dominance would not have expected to see their profits rise in the future. Instead, they would have expected to see their shipping costs surge and their rebates go to pay Standard Oil. Rather than resisting acquisition, they would therefore rush to be acquired before they were bankrupted. One Cleveland refinery owner later testified that “after having had an interview… with Mr. Watson, who was president of a company called ‘The South Improvement Company,’” he came to believe that “no arrangement whatever could be effected… that would enable [his] firm to compete with the Standard Oil Company.” Another refiner, John Alexander, recalled “a pressure brought to bear upon my mind, and upon almost all citizens of Cleveland engaged in the oil business, to the effect that unless we went into the South Improvement Company we were virtually killed as refiners; that if we did not sell out should be crushed out.”

Credence is given to such tales by the fact that all of Rockefeller’s acquisitions happened during a crucial three-month period: the three months between the creation of the South Improvement Company and the revoking of its charter—in other words, during that brief period when the refineries knew of the deal and still believed that it was going to go into effect. An owner of the second-largest refinery in Cleveland “stated positively that… [he] never considered selling out to the Standard before the SIC [South Improvement Company] was formed,” a journalist later reported. Indeed, in one extraordinary forty-eight-hour period, Rockefeller managed to acquire six refineries, several of which were apparently purchased at large discounts. The Cleveland owner quoted above claimed he had sold a refinery worth $100,000 for only $45,000 as a result of his certainty that he would be unable to compete. Many other refineries were sold for a quarter of their original construction cost—essentially, what the plants might have been worth at a bankruptcy auction. These were, for Rockefeller, fire sale prices.

There were, nonetheless, a few brave attempts at profiteering: once word got out that Standard Oil was buying everything in Cleveland, some refineries were started up purely in an effort to be acquired. To put a stop to such tactics, Rockefeller required the owners of refineries he was buying to sign agreements never to reenter the refining industry. Today, such anticompetition contracts would also be illegal, but there was nothing criminal about it at the time.

While there is a great deal of circumstantial evidence that the South Improvement Company deal was the driver of Rockefeller’s success, Rockefeller himself would, as long as he lived, vigorously deny these charges. When he was in his late seventies, the journalist William Inglis conducted an extended interview with the great man over the course of three years. In all those hours of interviewing, which produced some 1,700 pages of transcripts, Rockefeller lost his composure only twice. The first was in reference to his father. The second was in reference to the events of 1872, and accusations of coercion using the South Improvement Company. “That is absolutely false!” Rockefeller exclaimed, jumping from his chair. He stood over Inglis, his face flushed with anger, his fists clenched. “That statement is an absolute lie!” One could imagine that the rage was provoked by righteous indignation. Or by accusations that were close to the mark.

What happened after the rollup of Cleveland refineries was no less astonishing. Rockefeller consolidated his new holdings into six large, state-of-the-art refineries with scale production advantages (in the process shutting down many of the operations he had acquired, as their small size made them irredeemably inefficient). He then went on a nationwide buying spree. Some other refineries slated to be invited into the cartel had also made acquisitions—a company in Pittsburgh, for instance, had snapped up more than half of that city’s refining capacity. None, however, had moved so far in those three crucial months as Rockefeller had, and he was clearly the industry leader. By 1874, only two years after the South Improvement Company scheme was dismantled, Standard Oil had merged with the dominant refiners in New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. Rockefeller thus controlled 40 percent of U.S. refining capacity. He then, in each of these cities, repeated the tactics of Cleveland by buying the small refineries.

How he achieved this is something of a mystery, as no hard evidence has ever been produced of any other scheme along the lines of the South Improvement Company. Yet modern academics have uncovered evidence for a sort of “South Improvement Lite.” The railroads were charging Standard Oil much less than any of its competitors (enough to make the difference between profit and loss in the refining sector), possibly in exchange for a tacit agreement by Standard Oil not to pit the railroads against one another. Indeed, in a court case from the late 1870s, a vice president from the Pennsylvania Railroad testified that Standard Oil was by this point serving as an “evener” for a national railroad cartel. He stated that the agreed shares of oil shipping were 52 percent for the Pennsylvania, about 20 percent for both the New York Central and the Erie, and 9 percent for the Baltimore and Ohio, all enforced by Standard Oil. Did Standard Oil obtain rebates in exchange for this service? No one knows, although a comparison of published railroad shipping rates with Standard Oil’s (significantly lower) transport costs suggests something unusual was going on. By 1877, Rockefeller controlled 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining industry, and had for all intents and purposes a “natural” monopoly position and the profits that went with it. Between 1883 and 1896, average earnings at Standard Oil were a healthy 14.9 percent; from 1900 to 1906, earnings jumped to an impressive 24.5 percent.

If Rockefeller felt any moral qualms about his wealth secret, which turned oil refining into a natural monopoly business via the clever use of cartels, he did not show them. “The Standard was an angel of mercy” for these other refineries, he said, “reaching down from the sky, saying, ‘get into the Ark. Put in your old junk.’” While the language was grandiose, it was not delusional. Those Cleveland refiners who accepted Standard Oil shares when they sold out to Rockefeller were indeed made very rich, as the company of which they had thus become part owners went on to reap monopoly profits. They put their refineries into the Ark, as it were, and it bore them to financial security (although Rockefeller neglected to mention that he was the source of the Flood).

Rockefeller continued: “Our efforts [were] most heroic, well meant—and I would almost say, reverently, Godlike—to pull this broken-down industry out of the Slough of Despond.” As to why this process should have made one man unbelievably rich, Rockefeller considered that he had performed a great service to the nation by bringing an end to competition. Competition, in his view, had done no one any good. “It was the battle of the new idea of cooperation against competition, and perhaps in no department of business was there a greater necessity for this cooperation than in the oil business,” he said.

Rockefeller remained throughout his life, as you may by now have surmised, a devout Baptist. He conducted his home life accordingly, generally staying in at night with his family, avoiding the theater because it was proscribed by his religion. He perhaps remembered some tricks of his father’s, entertaining his children by balancing plates on the tip of his nose. His children became accomplished musicians, entertaining their parents by forming a household quartet.

The charitable giving of Rockefeller’s early years in business expanded exponentially. He donated the funds that turned the University of Chicago into a world-class institution, founded Rockefeller University, and created the Rockefeller Foundation. He also constructed a family estate in upstate New York that the American playwright George S. Kaufman memorably described as “what God would have done if He’d had the money.” And Rockefeller, perhaps more than any other robber baron, founded a dynasty. Eminent Rockefellers remained part of the U.S. political scene until the retirement of Senator Jay Rockefeller in 2013.