Wilderness Camping

Making Your Way In Nature’s Domain

“The only inducements I can think of for making a ten days’ journey through a strong wilderness, solitary and alone, were a liking for adventure, intense love of nature in her wildest dress, and a strange fondness for being in deep woods by myself.”

—Nessmuk

“Nessmuk” was the pen name of George Washington Sears (1821–90), eloquent outdoorsman and author of the classic book Woodcraft. In it he described a 60-mile trek through the wilderness of central Michigan at a time “when the Indians had left and the whites had not yet got in.” For meat he shot deer, taking what he could use and “leaving the balance to the wolves, who never failed to take possession before I was out of earshot.” He drank from streams and lakes and slept each night before an open fire on a fragrant bed of fresh-cut hemlock browse.

Today the old woodsman’s inducements are still strong, but the wilderness has shrunk. (His 10-day trip is now a one-hour drive on U.S. Highway 10.) Millions converge yearly on America’s parks and national forests, hiking trails, and wilderness areas for a taste of nature in her wildest dress. Because comparatively few venture from the beaten path, there are still vast areas accessible only on foot, where backpackers can enjoy the beauty and solitude that earlier generations took for granted. Most of these are in rugged country— mountains, deserts, and arctic wastes—where survival takes skill and where nature’s balance is precarious. Today’s camper must walk more carefully than Nessmuk did.

Head for the hills. When backpacking into high altitude, it pays to take it easy and enjoy the scenery. Thinner air means less oxygen per lungful; your head gets light, your legs grow heavy, and your heart works harder—and it takes time to acclimatize. Body moisture is lost faster than at sea level, so carry plenty of water and drink it often. When camping, remember that water boils at lower temperatures (–1°F for each 500-ft. rise in elevation), so cooking takes longer.

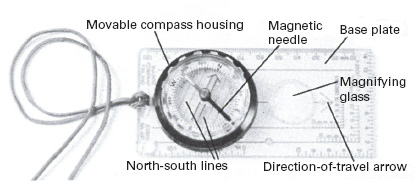

Compass and map are necessary tools for any wilderness outing.

A good campfire is a welcome treat after a long day of hiking. Fires are banned in many wilderness areas, but in places where fallen wood is plentiful and the danger of forest fire minimal, responsible campers need not forego its comforts.

The Wilderness has Many Faces: Woodland, Mountain, Desert, and Seashore

Home for the night. Tarp and stout rope are shelter for this autumn family outing—not so luxurious as a geodesic dome, perhaps, nor so weathertight as a mountain tent, but also not so heavy. Making camp early leaves daylight hours for preparing food and enjoying woodland surroundings, an important consideration when young children are along. This campsite was chosen for its level ground where sleep was comfortable and erosion minimal.

Lake water is fine for bathing or washing clothes, but always purify it before drinking (see page 418).

For Well-Dressed Hikers Fashions Never Change

Being well dressed in the wilderness has nothing to do with how you look but a great deal to do with how comfortable you are, how warm, how dry—and perhaps how alive. In general, old clothes are better than new as long as they are in good repair, and loose-fitting garments are preferable to tight ones provided they do not bunch up. Dress in layers—several lightweight shirts will insulate better than one heavy one. Layering also lets you attune your attire to the changing weather: three layers for a chilly morning, one during a warm afternoon, two for a cool evening by the campfire.

Underlayer. Avoid tight straps, elastic bands, and anything that binds or constricts; irritations intensify quickly on the trail. Cotton T-shirts prevent sunburn and protect against chafing from pack straps on hot days. Fishnet undershirts are good for all seasons—worn beneath a shirt they trap warm air, worn alone they allow ventilation. Thermal underwear and woolen long johns are warm in winter and comfortable on chilly evenings but can get steamy inside while hiking.

Basic clothing layer. Many backpackers swear by army-style fatigue trousers with large cargo pockets; any loose-fitting cotton or woolen work pants are good. The problem with western-style jeans is that, like cowboy boots, they are designed for horseback riding, not walking—the tight crotch, especially with a new pair, can restrict movement, even to the point of being painful. Avoid bulky belt loops, big buckles, and similar items around the waist—they can be instruments of torture under the waistband of a heavy pack. Bring a work shirt that is made of cotton, wool, or a moisture wicking fabric like polypropylene, depending on climate. Carry one or two woolen or fleece sweaters for extra layers of insulation when needed.

Outer layer. A lightweight (5- to 6-ounce) water-repellent nylon parka shell is a good windbreaker and fair protection from rain. A zippered neck opening allows you to let heat out and fresh air in without removing an entire layer. Down-filled shirts, vests, and jackets are unbeatable insulation as long as the down remains dry. They require the same care as filled sleeping bags (p.411). Bulky down-filled parkas are hardly needed except in near-arctic conditions (see Outdoors in Winter, p.431). A rain poncho can cover both you and your pack and can double as a tarp. To keep it from flapping in the wind, sew cloth strips on it to tie around your waist.

Sequence illustrates the principle of layering. Summer hiker at left dresses for cool comfort. As temperature drops, more layers of clothing are added. Warmth is trapped between layers.

Why wear a hat?

Tiny blood vessels on top of the head keep the brain cool by continuously giving off heat. When the sun is beating down—even if the air is cool at higher elevations—this ventilating system can be thwarted. The body compensates by cutting down the blood supply to the brain. Mental activity is slowed, and the rest of the body overheats, perhaps resulting in sunstroke. Guard against this danger by wearing a head scarf or lightweight hat.

In cold weather the body sacrifices the hands and feet for the sake of the brain. When the demand for warmth is great, blood vessels in these extremities constrict, forcing blood up into the head. Because heat continues to be lost from the top of the head, the process can escalate, possibly leading to hypothermia or frostbite (see Outdoors in Winter, p.431). When your hands and feet start to get cold, therefore, put on a wool hat to help conserve your body’s warmth.

Cotton, Wool, and Synthetic Fabrics

Clothing does not generate heat; it conserves the heat your body produces by surrounding you in dead-air space. Complications arise because the skin also expels about a quart of water a day—even more when you are active. If this moisture remains next to the skin, it drains body heat away through conduction and evaporation. Both cotton and wool absorb moisture but in different ways. Cotton fibers swell, eventually closing the spaces between them to form a solid, soggy wall; the wetter cotton becomes, the poorer the insulation it makes. Wool fibers, on the other hand, act like conduits or wicks, carrying water away from the body while preserving their own shape and texture. Even when soaking wet, wool maintains a good insulating air layer. For warmth, wear wool next to your skin. To keep cool, wear a light layer of cotton.

Synthetics, such as nylon, do not absorb moisture; they are of value as insulation only if no water collects between the fibers. Tightly woven, they may be almost impermeable, making for good protective outer wear. However, a fabric that keeps rain out also keeps water in. Though protected by a rainproof jacket, you can still find yourself and your clothing sopping wet. Materials like polypropolene or capilene help to solve this dilemma by wicking moisture away from the body.

A Good Boot Is Hard to Find

In Nessmuk’s words: “Light boots are best. Not thin, unserviceable affairs, but light as to actual weight.” The advice is still good—walking a mile means lifting each boot as many as 1,000 times, and the ounces add up. But it is hard advice to follow. A cobbler by trade, Nessmuk made his boots to his own specifications and advised others to do the same. The old woodsman never dreamed what a profusion of ready-made footwear would one day confront his readers. To single out the right pair for your feet and your purposes is no small task.

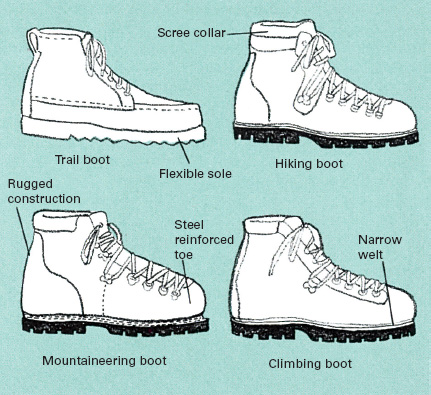

Most people tend to buy boots that are too heavy. Think about how you plan to use yours. For day hiking in summer along an established trail with fairly even terrain, 2- to 3-pound trail or work boots may be suf-ficient; they are light, their soles are flexible, and they give better support and protection than sneakers. For an assault on a major peak you need rugged mountaineering boots, solid and heavy (5 pounds is the minimum) with rigid lug soles and many layers of insulation. In between there exists a wide range of medium-weight hiking and climbing boots made for backpackers. The good ones have full-grain leather uppers, high enough and tough enough to protect and support your ankles; durable soles that can be replaced when needed; and firm internal support that prevents your arches from breaking down under the extra poundage of a full pack. To make waterproofing more effective, boots should have few seams, none of them sewn through, and the tongue should be gusseted at the sides to keep moisture out. Such niceties as interior padding and scree collars (they seal the top of the boots, making gaiters unnecessary) are matters of personal preference. Each has potential drawbacks: padded boots can become very hot on a long hike, and scree collars sometimes put strain on the Achilles tendons. Good boots do not solve every problem. Whatever boots you wear, keep your feet dry with wool socks, even in summer. If wool irritates you, wear inner socks of silk—never cotton. Two pairs of socks insulate better than one if boots are not tight.

Kinds of boots

Shoelike trail boots have flexible soles but give little support. Hiking boots are tougher and stiffer, a bit heavier. Mountaineering boots are heavy, well insulated, and very rugged. Climbing boots have rigid soles and narrow welts for support on tiny footholds; walking any distance in them can be uncomfortable.

Caring for your boots

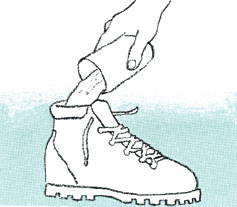

New boots are best broken in gradually by walking; for a quick job, fill boots with water and let them soak for a few minutes. Put them on wet, and walk for an hour or two so that leather will conform to your feet. To dry, stuff boots with paper and put them in a warm—not hot—place.

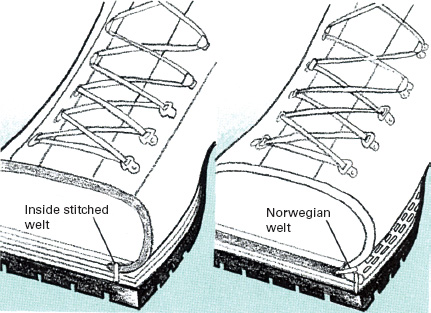

Welt of boot, where sole joins uppers, is a vulnerable area. Inside stitching is durable but must be done by hand, so it is expensive. In Norwegian welt, stitching is exposed and water can seep through; protect the welt with epoxy sealer. Bonded welts (not shown) are waterproof, but soles cannot be replaced.

How to buy a pair of boots that fit

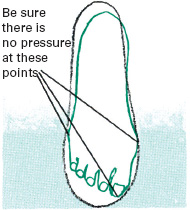

Among the many styles of hiking boots made by the dozen or so top manufacturers, there is almost sure to be a pair just right for your feet. Your second day in the wilderness is too late to discover that you failed to find them. The average shoe store does not stock a wide selection of hiking boots, so seek out shops catering to backpackers. Plan to visit several and be ready to make a pest of yourself. Try on as many boots as necessary until you find a proper fit: snug enough to prevent your feet from moving inside (which is how blisters are born) but not so tight as to constrict circulation. Try on both boots of each pair over wool hiking socks, and do not buy until you have walked around in them for 15 to 20 minutes.

1. Before lacing, push foot forward. One finger should fit behind heel.

2. Lace boots and stand. Wiggle your toes; they must not be cramped.

3. Kick a wall. Your toes should not touch the end of the boot.

4. Rock up and down; squat and bounce. Heel should not move in boot.

5. Stand on sides of feet to test for ankle support and painless flexibility.

Get a Good Night’s Sleep In Fair Weather or Foul

“I have suffered enough in close, dark, cheerless, damp tents.”

—Nessmuk

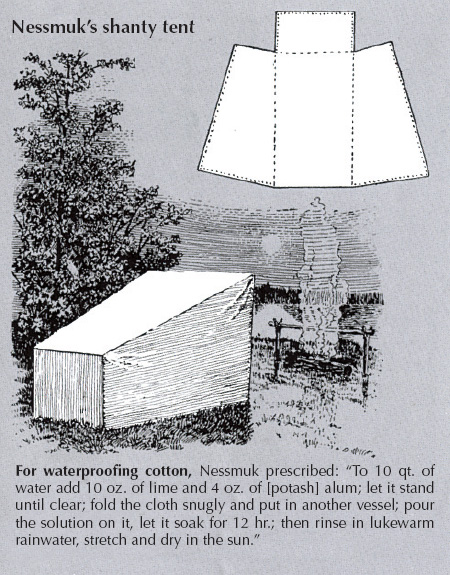

Next to a clear, starry sky, the old woodsman’s favorite shelter was an open-faced shanty made of cotton, which he waterproofed himself. It was stretched over a frame of freshly cut saplings. The front was open “to admit of a bright fire” and the roof slanted “to reflect the fire heat on the bedding below.”

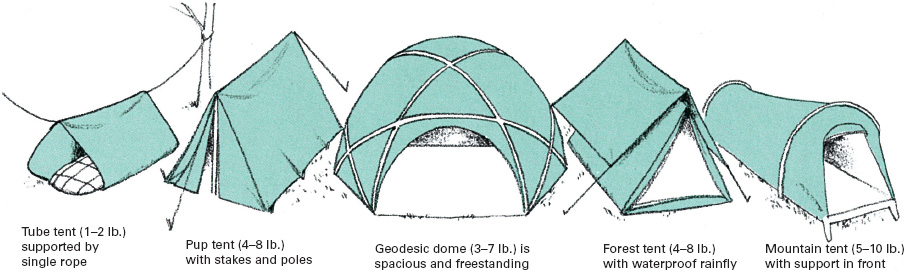

In his day, cotton and heavy canvas were the only choices for portable shelter. Today’s camper has the additional options of lightweight nylon and the somewhat heavier and costlier “breathable” resin laminates. The latter keep out rain while allowing water vapor to escape (see Cotton, Wool, and Synthetic Fabrics, p.408). You can accomplish the same end by stretching a rain-fly over your tent; this is a waterproof tarp fashioned to fit a few inches above the tent’s contours, repelling the rain while allowing water vapor to escape.

Tent designs have also progressed over the years. Campers can choose among many spacious shapes and sizes, most of them with easily erected, lightweight frames. Some are quite practical, some are worth carrying only in rigorous climates, and some are little more than pretty fantasies. Many are expensive, although you can cut costs by making your own from a prefabricated kit. Kits make the job easier than starting from scratch, but a lot of work is still involved—much of it requiring a heavy-duty sewing machine. Kits are also available for making down sleeping bags and garments.

The first question to ask in choosing a tent is: How much does it weigh? Put the answer on one side of a mental balance sheet. On the other side, consider your needs: Is it waterproof? Is it well ventilated? Is it fire re-tardant? Does it keep out insects? Is there space enough inside? How sturdy is it? Can it be put up in the dark? In a rainstorm? On a mountain slope?

Consider where you will be going and how long you plan to stay. For overnight summer bivouacs along a hiking trail, a tarp or tube tent might be all the shelter you want to carry. Even a tarp could be more than you need for a trek across the Arizona desert, where a poncho may be more valuable for shade than for rain protection. (The American desert is not the Sahara, however; sudden thunderstorms and even rainy weeks do occur.) In the damp Pacific Northwest or in the high Rockies, a warm, dry tent with a closable entrance and a rainfly is well worth its weight.

Tent Styles and the Knots to Tie Them

Two-man tent with low profile is best for warmth and wind resistance. High ridgeline makes for headroom and ventilation.

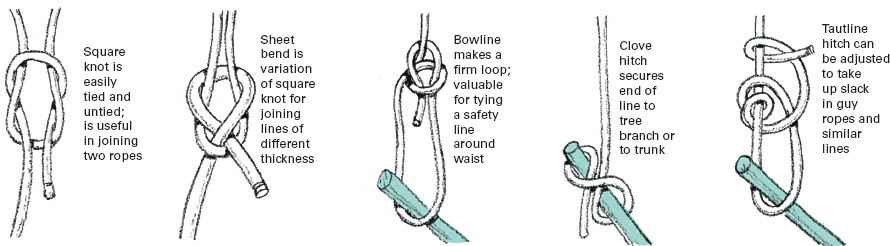

Knot tying is an important skill for erecting tents and other purposes. Practice these knots until they are automatic.

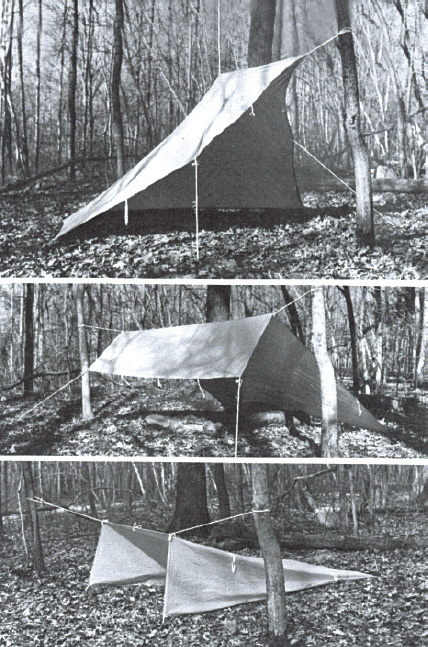

Skillful use of a tarp

Many backpackers carry only a length of 1/8-in. nylon cord and a nylon tarp (total weight about 2 lb.) equipped with a dozen or so strategically placed grommets or tie lines, from which they rig shelter for various situations. Setting up a tarp is harder than it looks; practice before depending on it for survival.

Bedding for Comfort and Warmth

Sleeping bags are graded according to the lowest temperature at which they will keep you warm. The lower the temperature, the warmer the bag and the more expensive it is likely to be. Try to purchase a bag that matches your anticipated needs—sleeping in an overstuffed bag can be almost as uncomfortable as sleeping in one that is too light. Some campers own several bags for different seasons and climates and use them singly or in combination for various weather conditions. A less expensive solution is the three-layer combination: one lightweight bag with an insert for use in colder weather and an outer shell of waterproof nylon or breathable resin laminate for foul weather use.

Most sleeping bags are filled either with down or synthetic fiber. The purpose of both is to maintain a layer of dead air between you and the outside. The thickness of this layer is called the loft: the more inches of loft, the warmer the sleeping bag. Goose down—the most expensive filling for sleeping bags—provides more loft per pound than any material known, but it packs together when wet and dries slowly. Although the synthetics do not give as much loft as down, most of them hold it better when damp. They tend to deteriorate with time—a drawback that is offset by their comparatively low initial cost.

A comfortable night’s sleep in cold weather depends on more than a good sleeping bag, however. An air mattress or, better yet, a foam pad—either closed cell or open cell—will not only cushion you but also insulate you from the cold ground. This is especially important because your body weight squashes the sleeping bag’s insulation beneath you, all but eliminating its loft. Other factors influencing nighttime comfort in cold weather are your own metabolic rate (some people are simply warmer than others), the relative humidity, the altitude, and the quality of tent you are using.

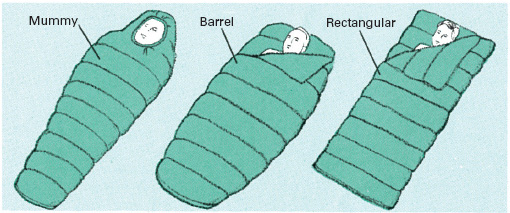

Choose bag for warmth, weight, and to suit your sleeping style. Mummy bag is warmest for its weight if you do not thrash about; heat is lost wherever elbows or knees compact filling. Rectangular bag is least efficient, but two bags can be zipped together for sharing.

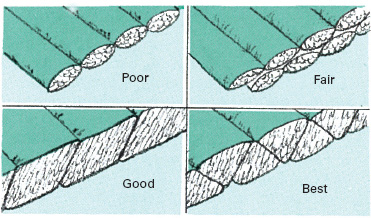

To keep filling in place, sleeping bag walls are joined to form chambers or tubes. When the stitching goes straight through, warmth is lost at each seam; for better insulation, baffles between walls are offset.

Caring for your down-filled bag and garments

Make every effort to keep your sleeping bag clean and dry. Do not roll it for storage, but push it loosely into a waterproof stuff sack. Sleep with your nose and mouth outside the bag so your moisture-laden breath does not condense inside the bag. Let the bag air dry after the trip is over, and repair all rips and holes promptly before filling is lost.

Never dryclean a sleeping bag or any other filled garment—the cleaning fluids will damage both down and synthetic fillings. Instead, wash by hand in a large tub, using warm water and mild nondetergent soap. Prescrub dirty spots, then submerge in soapy water and pump up and down. Do not wring or twist—baffles can be torn loose—and do not lift bag soaking wet. Rinse several times by draining the water, adding fresh water, and pumping some more. After the last rinse, when the water remains clear, gently press out all the water you can and gather the bag in your arms to support its weight. Spread the bag in the sun to dry (it will take several days), turning and fluffing it occasionally, or use a commercial dryer set at Low.

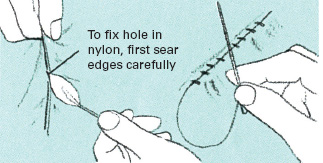

Carefully sear edges of small holes to prevent unraveling, then sew with nylon thread.

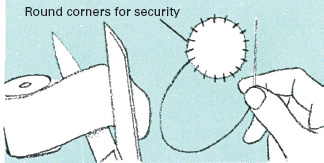

Patch large holes with pressure-sensitive rip-stop tape. Press in place and sew around edges.

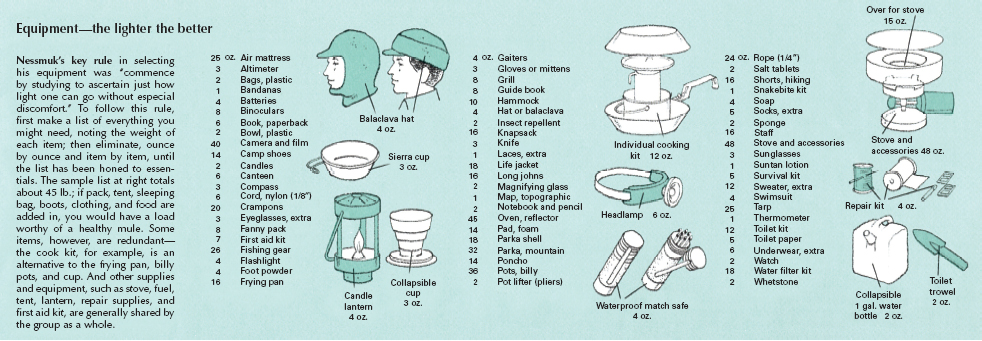

All Your Essential Gear Will Fit Into One Pack

“It may be remarked that man is a vertebrate animal and ought to respect his backbone.”

—Nessmuk

The human backbone is a remarkable but troublesome part of our anatomy. To use it for standing erect is in itself an amazing feat—but to hang weights upon it that pull it backward, or even to apply very much weight pushing straight down, is to treat it with disrespect. The best result you can look for is quick exhaustion; the worst, a disabling back problem. That is why pack frames were invented, to transfer as much weight as possible from the shoulders to the hips and to hold the rest as close as possible to the line of the spine.

A pack and frame is a personal thing. If it is to do its job properly, it must be fitted to your body as carefully as a suit of clothes. The most important dimension to consider is the length of your back from shoulder to hip. The pack’s waistband should rest comfortably on your hips and the straps must be high enough to hold the frame securely to your back without putting weight on the shoulders. Equally important and almost as personal is the method of organizing gear inside the pack. Some people are happiest with a pack that is divided into several compartments; others prefer a single large bag. In either case, the load must be well balanced with the bulk of the weight held close to the body and fairly high in the pack. Never select a pack based on how it fits when empty—the addition of a 50-pound load will change things considerably. One good way to find the right pack for yourself is to rent a few different kinds from specialty shops so you can make comparisons in the field.

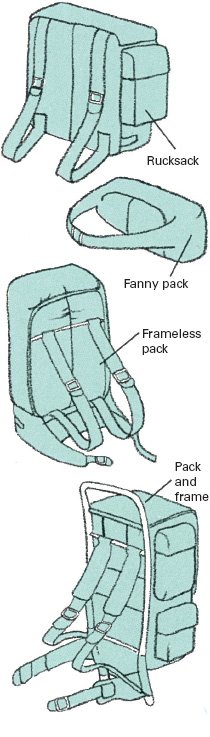

Pick the pack that suits your needs

Day packs. For a short hike or side trip with loads up to 25 lb., a rucksack strapped to the shoulders or a fanny pack strapped around the waist may be enough. Look for double stitching where straps join pack and around pack bottom.

Soft packs. Climbing and scrambling in forest and rough country is easier with frameless pack. Fewer protrusions mean less snagging on underbrush. Some soft packs have internal frames; others feature design innovations to eliminate the need for a frame altogether. Both must carry close to capacity for effective weight distribution.

External frame. Most comfortable way to carry heavy loads over long distances is in a pack attached to a rigid frame. Pack should attach to at east three points on each side. Padded straps should be firm, not spongy, be securely attached to frame, and have adjustable front buckles.

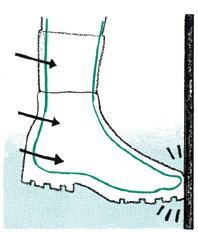

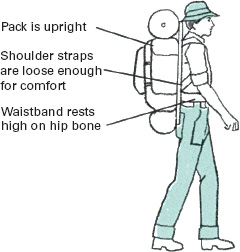

Fitting and loading for comfort

Try on pack loaded with 30 to 50 lb. Tighten waistband; it should fit snugly around top of hipbone and relieve weight from shoulders. Then adjust straps so you can slip two fingers easily between them and shoulders. Make sure all buckles are secure and that waistband can be released quickly in case of emergency.

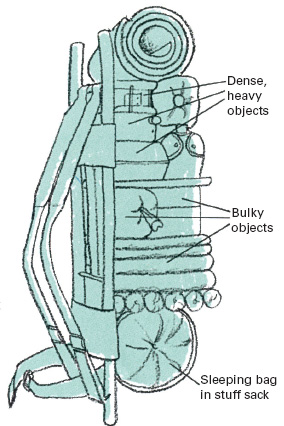

Organize your pack so everything has its place and stick to your system. Put dense, heavy objects high in the pack and close to your spine, with sharp corners padded. Make sure all weight is well balanced. One way to keep things separated is with plastic bags, making your pack a bag full of bags; coding the bags by color can help in identification. Use outer pockets for trail food, first aid kit, toilet paper, and other potentially urgent items. Lash sleeping bag in stuff sack to lower part of frame; in some soft packs waistband doubles as a stuff sack.

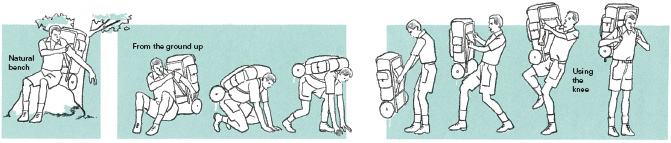

Easing the weight

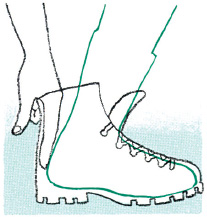

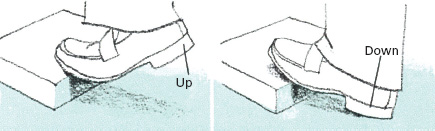

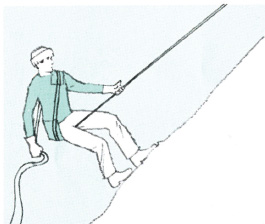

Getting a pack on and off can be more of a strain than carrying it. When taking a short break on the trail, leave your pack on; just lean back against a convenient tree or rock. When you take it off, put it down gently—lightweight frames damage easily. Two common techniques for putting on a heavy pack are shown at right. Yo u will likely develop your own style.

Hope for the Best and Prepare for the Worst

The best way to cope with an emergency is to anticipate and prevent it; the best time to do that is before you leave. Talk over every detail of the trip with your companions and reach agreements about your route, how fast to travel, what you will eat (meal by meal), what pieces of equipment are worth carrying and which are not, how early you intend to get started, how late in the day to stop. Decide on an equitable division of labor: who cooks, who cleans up, who pitches tents, who builds fires, who carries which piece of shared equipment, who knows about gathering wild food, who fishes, who is the best pathfinder, who leads on a rough trail, who has what talent or limitation that may be important later on. Discuss philosophy: Why are you going into the wilderness? For adventure? For peace and quiet? For exercise? How important is comfort? How important is schedule? If you arrive at a particularly attractive campsite, will you stay a day or two, or take a few pictures and keep moving? What happens on a rainy day? If you are not compatible, do not put your lives in each other’s hands.

Learn all you can about the area where you are going. If it is a place with which you are unfamiliar, talk to people who have been there. Read books and magazine articles about the region. Send for topographical maps and study them carefully (see Sources and resources, p.429). Use them to plan your route, selecting a place for each night’s campsite—you may not be able to stick to your plans, but they will provide a framework to keep track of your progress. Find out about the climate—average high and low temperatures, precipitation, possible extremes—and check on weather predictions, both short range and long range. Learn about the area’s plant and animal life, especially what is edible and what is dangerous during the season when you will be there. Make sure you know about local licensing and conservation laws as well as land-use regulations.

Gather together all your equipment and check it out. Set up the tent and wet it down to see if it leaks. Go over seams on packs, sleeping bags, and clothing, looking for weak spots and signs of wear. Condition and waterproof your boots. Make sure your compass is in working order.

If you or any of your companions is a minor, be sure to carry a medical permission slip, signed by a parent or guardian, giving any doctor permission to treat illness and injury. Finally, make a copy of your itinerary, including a map, and leave it with someone dependable so that if you fail to show up when and where you should, people will have some idea where to start looking.

Getting in shape

Wilderness backpacking is a demanding sport, and your life may depend on your strength and endurance. You can build endurance by running long distances with your boots on. (“Running a stadium” is popular among back-packing college students—you can see them on spring mornings racing heavy booted up and down the steep aisles of football stadiums.) A daily regimen of sit-ups, push-ups, and pull-ups strengthens the arms and upper body. Climbing a 15-foot rope wearing a full pack is another good exercise. For the torso, try the trunk-twister. Stand with feet apart, arms out, and knees straight; pivot to grasp the right ankle with the left hand; pull a little, release, stand straight, and repeat on the other side. Work up to 50 of these per day.

To stretch leg muscles, stand on edge of a thick book. Rise up on toes, then touch heels to floor. Repeat 40 to 50 times.

Getting There on Foot And Enjoying the Trip

“We do not go to the green woods and crystal waters to rough it, we go to smooth it. We get it rough enough at home.”

—Nessmuk

The key to walking long distances over rough ground with a pack on your back is maintaining a comfortable, steady body tempo (not to be confused with a steady pace; drill sergeants may march their units in cadence, uphill and down, but for them hiking is a job, not a pleasure). The best gauge you have of your body’s tempo, short of monitoring your pulse, is your breath rate. Establish a steady rhythm of deep breathing on level ground, taking three or four steps for each intake of air and three or four on each exhalation, and adjust your pace as needed to maintain the rhythm. On an uphill pull, for example, reduce the count to two steps before you get short of breath; a real climb may dictate one step per breath or less. At first you will probably have to discipline yourself to slow down (beginners tend to go uphill much too quickly). Eventually, a well-established body tempo will tend to take care of itself.

Be economical with your energy; spend it only on necessities. A springy step takes energy, so walk flat-footed, using the large thigh muscles. Energy is wasted stepping up onto a rock or log, so step over or go around such obstacles. Energy is depleted by chills or overheating; add or remove a layer of clothing before discomfort demands that you do so (often it is enough to open the top of your jacket in order for trapped air to escape). Make a rest stop every hour or so, but not for too long— getting started is hard once you have cooled off. Eat a little high-energy trail food, such as chocolate “gorp” (see Campfire Cookery, p.420), whenever you feel hungry. Prevent dehydration by sipping water often.

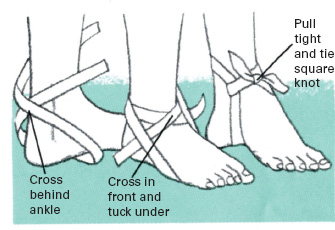

Take good care of your feet. They are your only means of transportation. Remove your boots and socks at rest stops to let your feet cool off and air out; when you have the chance to soak your feet in a cool stream or lake, take it. If you feel the beginning of a hot spot—a point of irritation—do not be heroic. Stop and cover the spot with a piece of moleskin or a bit of masking or adhesive tape before it becomes a blister. (For treatment of blisters, see First Aid in Emergencies, p.426.) When fording a stream, remove your socks and put your boots back on, lacing them tightly. Afterward, drain the boots and replace your socks; if they are wool, they will absorb the remaining moisture in your boots safely.

If you are part of a group (and two or three people is a group), gauge your pace to the slowest and the weakest. If you are the slowest, or if you develop a problem, such as blisters or a muscle pull, do not hesitate to make your needs known—better to slow the group than to be carried out. (But avoid idle complaints; everyone is enduring the same weather and being bitten by the same bugs.)

There are courtesies that backpackers observe. If you are following an established trail, stay on it; switchbacks are there to prevent erosion—do not shortcut them. If you find a shortcut developing, block it with brush. On a steep trail, descending hikers have right-of-way; clear the trail for them. Parties with pack animals always have right-of-way; move off trail on the downhill side and stand still (a horse spooked by your presence is easier to control and less likely to be injured if he shies uphill). Do not intrude on other campers unless invited, and then do not stay long. Do not accept food even if it is offered unless your need is very great.

The Fine Art of Walking

On level ground. Within the limits of comfort, long strides are more efficient than short ones. Keep heavy items high in pack and close to body so that the weight is centered over your hips.

Going uphill. Short steps minimize the struggle against gravity; so does the use of a staff or alpenstock, which also helps maintain balance. Stand straight rather than leaning forward (it will feel at first as though you are tilting backward) to keep your weight centered—and so that you can regain your balance in case of a slip before landing on your face. The best place for heavy items on a long climb is in the middle of the pack, close to your body. When climbing a very steep slope, use the mountaineer’s rest step: pause briefly and exhale with each step after placing your front foot and before transferring your weight from the rear foot.

Going downhill. Stress is on toes, soles of feet, and knees. Tighten boot laces so feet do not move inside. Take short steps with knees slightly bent to cushion impact of each step. Lean slightly forward to help keep balance in case of a slip.

Traversing hillside. Lean away from hill, not toward it, to minimize stress on ankles, knees, and spine and so that body will be thrown into an upright position in case you slip. Use of staff or alpenstock helps to equalize weight and maintain balance.

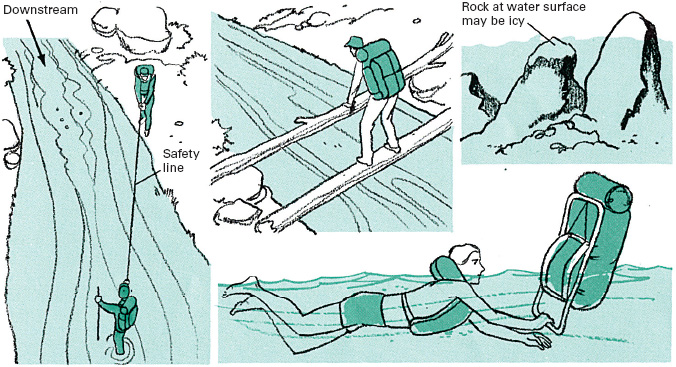

Water Crossings Are Always Risky

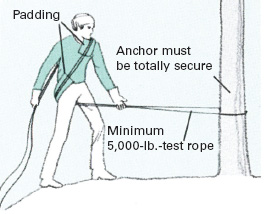

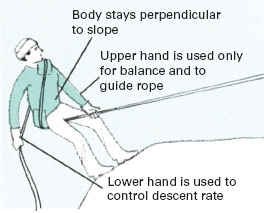

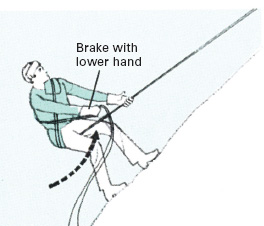

Try to keep dry by boulder hopping or using a foot log. Ford a large stream at a wide spot where water moves slowly; undo waistband so pack can be shed quickly, face upstream, and sidestep across. If stream is deep or if you must swim, use safety line secured upstream; place heavy waterproof items in bottom of pack, the remainder in a plastic bag for buoyancy. Snow-fed streams are fullest late in the day, lower and slower in the early morning.

Keeping a Weather Eye

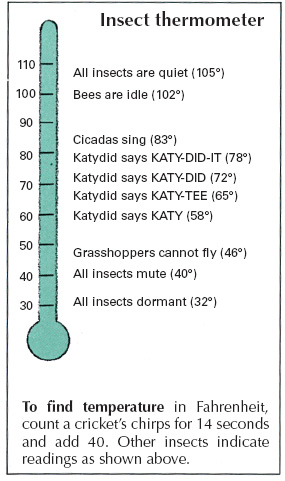

Professional weather forecasters arrive at their predictions with the assistance of such instruments as barometers, hygrometers, and thermometers, each of which measures some aspect of the ever-changing atmosphere: air pressure, humidity, and temperature, respectively. The wilderness is filled with indicators every bit as accurate, if not so nicely calibrated. Knowing how to read them is one of the skills of outdoorsmanship.

Masses of cold and warm air move across the earth from west to east at a rate of about 600 miles a day, propelled into and around pools and eddies of high and low pressure. Air blows clockwise away from the center of a high pressure area and counterclockwise toward the center of a low pressure area, where it escapes upward, cooling as it rises and leaving behind the moisture it contains. Thus a drop in air pressure (a falling barometer) generally indicates the arrival of a pocket of humid air, clouds, and, often, rain or snow, particularly when the low pressure area is at the front of an air mass. There are many signs of an approaching low pressure area: smoke hovers and turns downward; birds tend to roost; swallows and bats swoop low; ground odors arise from ditches and marshes; clouds form at low altitudes; the rising humidity makes hair limp, causes distant objects to appear closer (because the usual evaporation haze is missing), and precludes the formation of morning dew. These signs are all prominent among folklore’s favorite foul weather warnings.

Other bits of weather lore are also firmly based in fact. Take, for example, the expression “Red sky at night, sailors’ delight. Red sky at morning, sailors take warning.” (The setting sun shines through tomorrow’s air, 500 to 600 miles westward; the laws of light refraction are such that if that air is dry and cloudless, the sky will be red just after sunset. The same laws decree that a red sky before sunrise means the air that has passed to the east is clearer and drier than where you are.)

There are three basic cloud types: cirrus (wispy), stratus (layered), and cumulus (puffy). Each is produced by a specific air pattern, and each may presage a particular kind of storm. Learn to read the early steps of these developments. Fluffy white cumulus clouds, for example, are formed by warm updrafts called thermals. They are common on clear days and generally foreshadow more of the same, but they are also the stuff of which thunderstorms are made. When a thermal is intensified by the moist updraft of a low pressure area, the result is a huge, billowing thunderhead (cumulonimbus), bringing strong winds, thunder, lightning, and a downpour of rain. The telltale step in this pattern is when fair weather cumulus clouds begin to puff upward like the turrets of a castle. Such towering cumulus clouds are not always followed by thunderheads; but when they occur in the west or northwest sky, a little darker and lower than other cumulus clouds, the wise camper begins to make preparations for a sudden storm.

Cirrus clouds are made of ice crystals, formed when warm air suddenly meets cooler air (the way your breath forms vapor on a cold day). Often they signify nothing more than a high altitude wind pattern, but when they begin to form a thin, icy layer (cirrostratus)—causing the appearance of a halo around the sun or moon—it is probably the first warning of an approaching warm air front, with a long, steady siege of rain or snow.

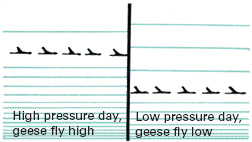

Migrating geese maintain their altitude by sensing air pressure; the more the pressure, the higher they fly. Low-flying geese mean a falling barometer, an omen of bad weather.

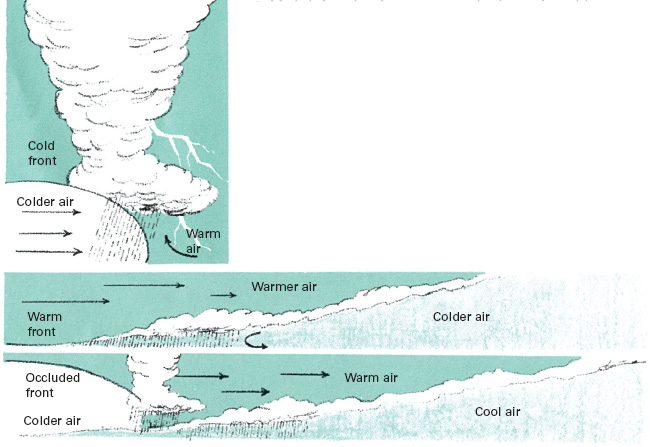

Learn to Read the Language of the Clouds

Cold air is heavier than warm, so the front of a cold air mass (left) hugs the ground as it moves eastward, pushing warm air upward like wood shavings before the blade of a chisel. Cold fronts give little warning: winds may change to easterly or northeasterly often creating a squall line (a band of high winds and short-lived thundershowers) a few minutes before their arrival. Layers of cumulus clouds (cumulostra-tus) or thunderheads may accompany the front itself. Warm fronts (below) move more slowly and give 10 to 15 hours warning. Wispy cirrus clouds accumulate and grow steadily lower, and winds often shift to easterly or southeasterly; long, steady rain from low stratus clouds presage and accompany the front itself. When a cold front overtakes a warm front, the result is called an occluded front; the sky grows dark, and heavy weather, snow, or violent winds often result.

Cumulus clouds, fed by warm updraft of cold front, develop towering form, warning of approaching thunderstorms or snow.

Cirrus clouds form wispy mares’ tails before warm front hits. Next comes cirrostratus, then “mackerel sky,” then rain.

Sound travels a mile in about five seconds; light arrives almost instantaneously. To find how many miles away a thunderstorm is, count the seconds between a lightning flash and the thunderclap that follows it, and divide by five.

With a Map and Compass You Are Never Lost

Tales abound of frontiersmen plunging into unmapped wilderness and homing in with pinpoint accuracy on some far-off cabin or clearing in the woods. Today’s camper, equipped with topographical map and compass, should have an advantage over the old-timers, yet many succeed in getting lost—some permanently. Why? For one thing, not everyone carries these vital tools at all times; for another, many do not know how to use them; and finally, there is more to finding your way than reading a map and knowing which way is north.

A topographical map, or “topo” in backpacker’s parlance, is a picture of the landscape drawn with contour lines, each of which represents a constant plane of elevation above sea level. Because the picture is a bird’s-eye view, the closer together the lines are, the steeper the slope they show, while the wider the space between lines, the more gradual the change in elevation. With practice you can learn to visualize any terrain from its depiction on a topo—at least in terms of its larger features. Then if you are in a position to see major landscape features around you, it is possible to orient the map to the real world and to find your position upon it.

Topos exist for all areas of the continental United States in several scales, or series. The most valuable of these for campers are the 7 ½-and the 15-minute series. Each map in the 7 ½-minute series covers 7 ½ minutes (1/8 degree) of longitude (about 7 miles) at a scale of 1:24,000, or about 3/8 mile to the inch. A 15-minute map covers an area four times that size at a scale of 1:62,500, or about 1 mile to the inch. Contour intervals vary from 80 feet of elevation between lines on some 15-minute maps to 10 feet on some 7 ½-minute ones. Each series has its advantages, each its pitfalls. Because 15-minute maps depict a larger area, they are easier to orient to large landscape features, and you need not carry so many of them. On the other hand, 7 ½-minute maps show details that could be vital; it is possible, for example, for a sheer 150-foot cliff not to show at all on a topo with 80-foot contour intervals. Moreover, some of the older 15-minute maps are out of date or, worse yet, inaccurate.

Camping supply stores, sporting goods stores, and some bookshops often carry topos. Or you can write to the U.S. Geological Survey Office for a free index map of any state, from which you can select the topos you need (see Sources and resources, p.429).

The Map

Terrain features take on very different appearances when viewed from different angles. Photo 1 (left above), taken from point A on the map, shows the same mountain ridge as seen in photo 2 (right above). Photo 1 also shows the spot (point B) from which photo 2 was taken. The contour interval on the map is 20 ft. Note that every fifth contour line is heavier than the others and its elevation is labeled; the exact elevations of high points are labeled as well. On a standard topo map contour lines are brown; man-made features, such as roads and buildings, are black; and forested or overgrown areas are shaded green.

The Compass

The compass needle is a small magnet that points not toward the North Pole but toward magnetic north. The difference between the two, known as the angle of declination, varies with location and changes slowly with time. (There is a line, running more or less through Savannah, Georgia, and Gary, Indiana, along which they are currently the same.) The exact angle of declination for an area is given in the legend of a topo. If your compass has a movable collar, set it to reflect this declination, and align the compass so that the needle points to N on the collar; then move the map so that its north-south axis aligns with the north-south axis of the compass. If your compass has no collar, spread the topo out flat and place the compass on it so that its north-south axis aligns with true north on the map. Then turn map and compass together until the angle between the needle and true north matches the angle of declination. Next, look for a terrain feature that you can identify on the map. Take a reading on it and draw a line on the map along this bearing. If you cannot locate your position by studying the nearby terrain, sight on another landmark. Where the two lines intersect is your position.

Orienteering compass (shown above) has inner scale for angle of declination and movable casing for direction finding. Another popular style—the sportman’s compass—has a movable inner disk with an arrow that can be used for either purpose.

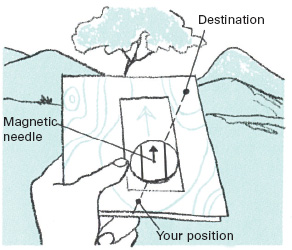

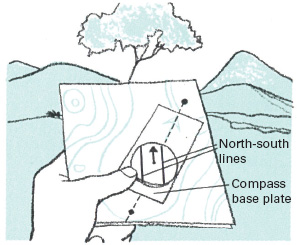

Deciding which way to go

1. Orient map and use compass to find your position on it. Draw line on map from your position to destination.

2. Place compass base plate on this line. Rotate compass housing so north-south lines match magnetic north on map.

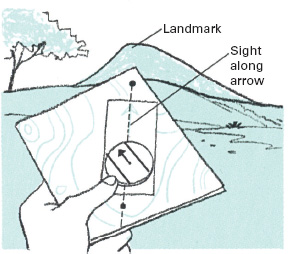

3. Hold compass and map steady, and view along direction-of-travel arrow to sight a landmark (hill in distance).

How to get there from here

Having sighted a landmark, you theoretically need only hike to it and take another reading. Or, having set your compass, you could keep the needle pointing to north on the dial and follow the direction-of-travel arrow to your destination. In fact, you can seldom do either: obstacles, ranging from bramble thickets to mountains, will probably cut off sight of your landmark; they may also obstruct progress. Some obstacles can be anticipated by studying the topo; others will be surprises. If you find you must go far out of your way, take a reading of 45 degrees and follow it, counting your paces, until you have gone far enough to clear; then take a reading of 90 degrees in the other direction and count the paces back; finally, take one more reading of 45 degrees to resume your original line of travel.

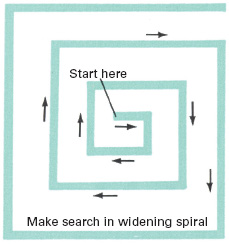

If you find yourself close to an objective—a wooded campsite, for example—but unable to locate it, make a methodical search pattern. Walk a set distance (20 paces, perhaps, depending on how far you can see) in any direction; then turn 90 degrees and walk the same distance. Turn 90 degrees again, and so forth, adding 20 paces every second turn.

Finding Yourself

The best advice about getting lost is: do not. Follow your progress on the topo and use your compass to stay oriented. Be aware of landmarks and their relation to one another; look backward from time to time to memorize the terrain from the other direction.

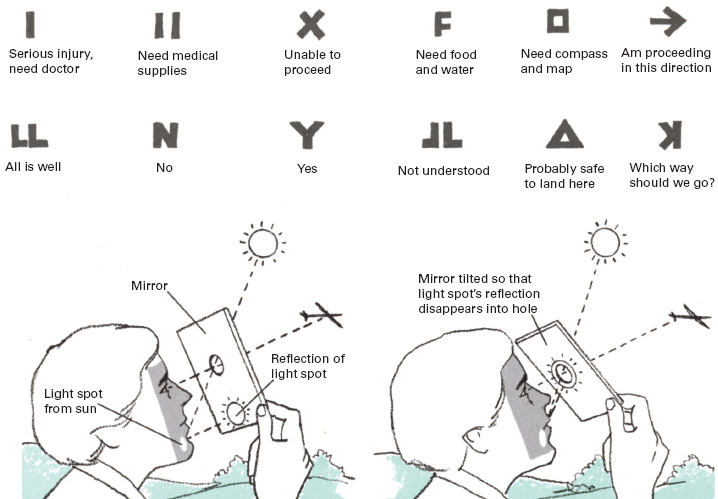

But suppose you do become disoriented? As Nessmuk observed: “It has a muddling effect on the mind, this getting lost in the woods. But if you can collect and arrange your gray brain matter and suppress all panicky feeling, it is easily got along with.” Resist the impulse to panic. Resist all impulses. Stop, relax for a while, and think. You have three choices: you can retrace your steps, stay where you are, or reorient yourself and proceed. If you have become separated from a group, stay where you are, signal your position in some way, and wait to be found. If you are alone, or if the whole group is lost with you, first orient yourself to north and south. Look for landmarks—if you can see none, seek high ground or climb a tree. Then decide whether to go back or go forward. At the very least, use the knowledge of which way is north to move in a straight line.

Orienting yourself without a compass

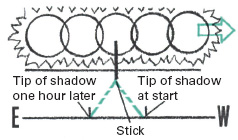

Sun or moon. Insert a short stick in the ground and mark where the tip of its shadow falls. One hour later, mark again. The line between these marks is roughly east-west; the stick is on the south side of the line.

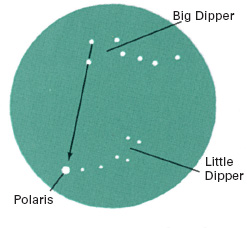

North Star. First find the Big Dipper. Trace an imaginary line between the two stars that form its front lip and extend this line five times its own length to locate Polaris—never more than one degree from true north.

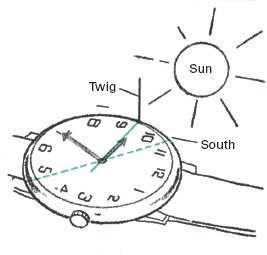

Watch. Insert twig into level ground. Place watch with hour hand pointing toward twig, aligned with its shadow. If watch is set to standard time, halfway between hour hand and 12 o’clock is south.

Midafternoon Is the Time To Pick a Campsite

“If there is a spot on Earth where trifles make up the sum of human enjoyment it is in a woodland camp.”

—Nessmuk

Nessmuk’s “trifles” were mostly examples of old-time woodcraft—pillows stuffed with hemlock browse or fire pokers and tongs fashioned from green hickory sticks— but the crux of his advice holds true for today’s campers who carry their trifles with them.

The ideal campsite is on bare and level ground well off the trail, about 100 feet from fresh water (no closer), with plenty of dry wood scattered handily about. It is sheltered from wind but not in a hollow where damp air collects. It is not in a gully or natural runoff (in case of rain), and it offers esthetic pleasures: a nice view, the fragrance of surrounding pines, the murmur of a stream, the warmth of the rising sun. It is worthwhile to search out such a spot for a long-term campsite. For an overnight bivouac you may have to be satisfied with considerably less. To hold out for the perfect campsite can lead to such joyless feats as pitching a tent in the dark on top of what you later discover to be an anthill.

The first important trifle—if it is neither raining nor threatening to start—is to spread and fluff your sleeping bag. Then get water on to boil for coffee, tea, soup, or whatever pick-me-up you fancy. Relax awhile and enjoy; change your boots for soft camp shoes if you carry them (another trifle well worth the weight). Then there is work to do—gear to unpack, shelter to set up, water to haul, dinner to cook and to clean up after, food to store, firewood to protect for morning—all before nightfall if possible. Before turning in, be sure that you have a water bottle handy as well as a flashlight, first aid kit, toilet paper, and shovel or toilet trowel.

In foul weather, shelter obviously comes first—a good reason to pack your tent on top. If yours is a floorless pup tent, erect poles, then stake the sides to the ground; if it has a built-in floor, drive stakes first. Freestanding tents need not be staked at all in calm weather or, in any case, only after they have been erected.

Purify Water Before Drinking

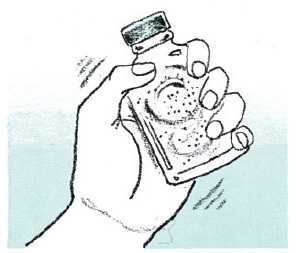

You cannot count on drinkable water from even the clearest stream. If you are not certain of the water quality in the place where you plan to hike, either bring the water you need or carry a method of purifying what you find. Halizone tablets do not always do the job, and they deteriorate with age; iodine is more dependable. An iodination kit consists of a 1-ounce clear glass bottle with a tight-fitting cap and about 5 grams of USP-grade resublimated iodine crystals (available from pharmacists). The crystals can be reused up to a thousand times. Filtration devices are also available to remove pollutants and diminish the iodine flavor of purified water.

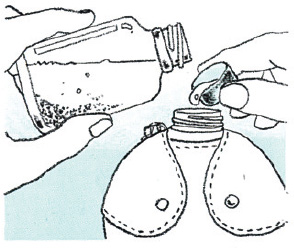

1. To kill amoeba, bacteria, viruses, and other microbiota, place about 5 grams iodine crystals in 1-oz. glass bottle and fill the bottle with water. Screw the top on tightly and shake for one minute.

2. Allow crystals to settle. Saturated solution (not crystals) is added to drinking water. The strength of the solution depends on water temperature: the colder the water, the weaker the solution.

3. If water is 75° F, add 2 tsp. solution to 1 qt. water; at 40° F add 3½ tsp. (bottle cap usually holds ½ tsp.). Let stand 15 minutes. For milder iodine taste use half as much solution; let stand 30 minutes.

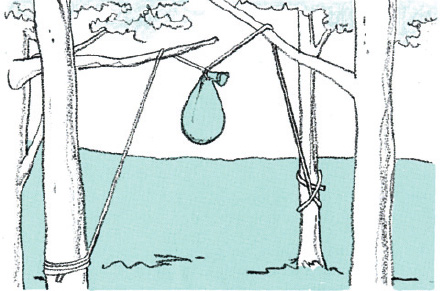

Protecting food from animals

Food attracts animals from chipmunks to bears. Do not keep it in your pack or in the tent overnight. Store food bags in one large plastic bag suspended from a tree limb or crossbar. In parks and along trails, where bears are consummate thieves, use two ropes as shown; bags must be at least 15 ft. high and 6 ft. from tree. Black bears usually flee loud noises—bang pots and pans, and yell. If they do not go away, do not argue further. Grizzlies are less timid; keep still. If they charge, lie down and play dead.

Sanitation and cleanliness

If toilet facilities exist, use them. They mean that the area is used by too many people for any other solution. If not, dig a hole 6 to 8 inches deep (not below topsoil, however), use it, burn the used toilet paper and drop it in. Cover your leavings with a little soil. Before abandoning the campsite, fill in the hole with the soil you took out and tread it down firmly. If you are part of a group, designate one person to choose and prepare the latrine site—it is as important as any other aspect of camp life. Its distance from camp must be a compromise between convenience and common sense. Do not dig it on rocky ground and never within 100 feet of any watercourse—even a dry bed. Do not pick a place that might otherwise make a good campsite for someone else.

Do not carry detergents into the wilderness. Wash dishes, clothes, and yourself with soap. (Actually, cleanliness is generally overdone by neophyte campers—in Nessmuk’s words: “Don’t fool with soap and towels where insects are plenty.”) In any case, do not use soap directly in a lake, stream, or other water source. Nor should used wash water be dumped into such a place. Carry water to your campsite, heat it over the fire or stove, then take it farther away from the source before you use it. Dig a sump hole (following the same rules as digging a latrine) in which to dump it.

Making and Managing a Fire

If you are camping in a heavily used area or in a place where trees are scarce, use a portable stove for cooking. But in a lowland forest where deadwood is plentiful and campers are few, there is no good reason to deny yourself the pleasures of a cooking fire.

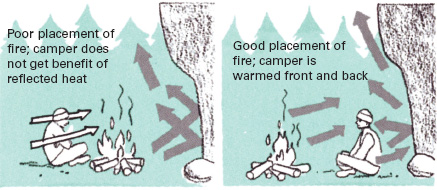

Gather the wood you need while it is still daylight; foraging is difficult in the dark. Collect fallen wood only. A standing tree, no matter how dead it looks, is not fair game. Locate your fire on bare ground (preferably sand, rock, or gravel)—never on forest duff, humus, grass, or peat, all of which could smolder for days before bursting into flame; and never next to a tree, log, boulder, or rock face. (The tree can be killed, the log may be ignited, and the rocks will be defaced by scorch marks for decades or longer.) Clear a circle about 10 feet across of all burnable debris and in the center construct the simplest fireplace that will serve your needs, either by arranging flat rocks or by digging a shallow hole. If another camper has left behind a fireplace, do not build a new one.

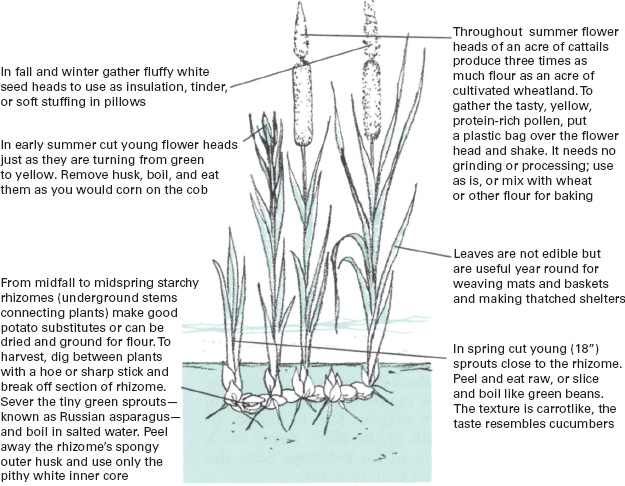

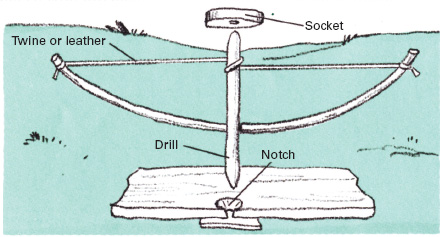

The fire itself has three components: tinder, kindling, and fuel. Tinder is any such easily ignited material as paper or the dry tops of some plants (goldenrod, cattail, milkweed, Queen Anne’s lace). The bark of a dead birch or aspen and pitch gathered from bends and knots of pine trees will burn even when wet. The best kindling is small twigs, especially from evergreens, willows, and poplar; its purpose is to generate enough heat to ignite the fuel. In case of difficulty whittle shavings from any dry stick. In wet weather you can use the heartwood of dead logs, litter from inside a hollow tree, pine cones, and abandoned bird or squirrel nests. For fuel the best cooking coals come from hardwood sticks 1 to 2 inches thick. The wood of conifers, pine in particular, ignites quickly and burns brightly because of the pitch it con-tains—another wet weather stratagem—but it burns out fast, imparts an unpleasant flavor to broiled meat, and throws off dangerous sparks.

When you are done with a fire, put it out thoroughly and completely. Douse the ashes with water, stir them around, and douse them some more. Before you move on, dismantle the fireplace. Put the rocks back where you got them, scorched side down, and scatter the dead ashes far and wide; if you dug a hole, fill it in with the dirt you took out. Distribute leftover bits of food for small creatures to dispose of. Any other trash that cannot be reduced to ashes, carry away with you.

Keeping Food Cool

Picnic coolers and thermos jugs are far too weighty for backpacking, so fresh meat and other perishables are out of the question as regular provisions on a long hike. For the first day or two, however, or for a weekend jaunt, you can improvise a lightweight cooler from three plastic bags and a towel or cotton cloth. Fill one bag with ice and seal it tightly. Place it, along with your perishable goods (a steak, perhaps, or a pound of hamburger), in a second bag; seal it and wrap it in the cloth. Then seal the whole package in yet another plastic bag and place it in the bottom of your pack. At the end of your first day on the trail—a time when morale is often in need of a boost—you will have fresh meat to enjoy and a bag full of cool water. (If you start with frozen meat and do not open the sealed bags, this makeshift thermos should keep the meat fresh for two days on the trail.)

To keep foodstuffs cool overnight, seal them in a waterproof bag along with a rock for weight, and immerse it in a stream or lake; attach a safety line with which to retrieve it. If you are not near a body of water, make an evaporative cooler: put perishables in a light-colored cloth bag and hang it in a shady, breezy place. Keep it damp; evaporation will cool the contents.

Stoves, Fires, and Fireplaces

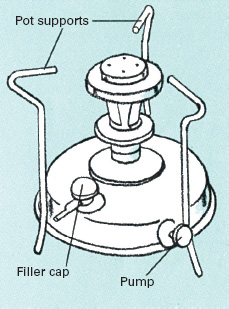

Most cookstoves are fueled by butane or white gas. Butane cartridges are safe and convenient but inefficient in very cold weather. White gas gives more heat per ounce, but it is volatile. Accessories include fuel container, funnel, and eyedropper for priming.

Tepee pattern concentrates flame at the high point and consumes fuel quickly; use it to ignite kindling, to boil water, to heat a reflector oven, and to dry damp wood. Arrange kindling over tinder, leaving plenty of space for air circulation. Light tinder from upwind side. When kindling has begun to burn well, add sticks for fuel until fire is the desired size.

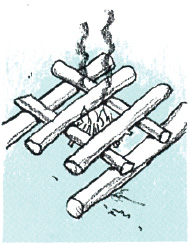

Log cabin pattern burns more evenly; use it to make a bed of coals. Place two large sticks parallel for a base. Between them arrange kindling over tinder in tepee fashion, then place kindling across base. Put several larger sticks across these and continue to build crisscrossed layers, leaving enough space between sticks for air to circulate freely.

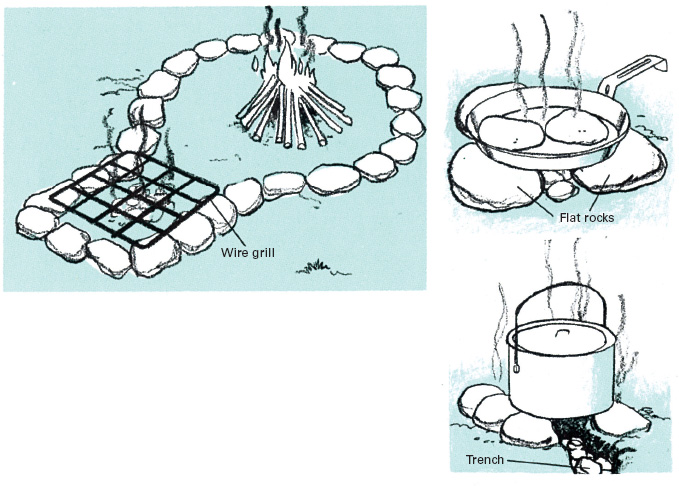

Keyhole fireplace is ideal for base camp or long-term campsite where much cooking will be done. Use flat rocks to enclose cooking slot, making it just large enough to be spanned by wire grill if you have one, narrow enough for pots and pans to rest across if you do not. Wood is reduced to coals in round area, giving light and warmth in the process; for cooking, rake the coals into slot. For overnight bivouac, fireplace can be made from three flat rocks or by digging a narrow trench. Heap soil from trench in one spot so you can replace it before breaking camp and moving on.

The Joy of Cooking Over an Open Fire

The biggest difference between cooking over a campfire and on a stove is that you can adjust a stove’s burner at will, but you must use a fire when the fire itself is ready. The usual beginner’s mistake is to immolate a meal by trying to cook over too hot a blaze. Reflector ovens need an open flame, but frying, broiling, stewing, or baking in closed containers calls for a bed of glowing coals. Water boils faster over an open fire, but rigging tripods, trapezes, dingle sticks, or other improvised devices for suspending a pot is a risky business—the odds are good that the whole contraption will collapse about the time the water gets hot. Compromise by putting a pot of water on to boil as soon as you have raked the cooking slot of your keyhole (see p.419) full of coals, while tongues of flame still lick upward. Use your largest pot—there are plenty of uses for hot water. Save any hot water that is left over from making coffee, tea, soup, or your preferred end-of-the-trail revivifier. If you need the pot for preparing the meal, pour the water into another container. Then after you have cooked your meal, use this water to rinse out the pot. Then rake a few fresh coals into the cooking slot, and while you eat, let some more water boil for cleaning up.

One-pot cookery is mostly a matter of stew, soup, pasta, and rice-based dishes, with protein provided by cheese, sausage, jerky, and various dried meats. Too often the result is nourishing but dull. This need not be so—a little imagination in packing provisions and a little more at the cookfire can turn even a steady diet of macaroni and cheese into a series of varied repasts. Add tomato crystals, garlic, oregano, and foraged burdock leaf stems for a zesty Italian dinner; the addition of margarine, dried milk, powdered eggs, dried mushrooms, wild onions, and watercress produces a flavor-some casserole with French overtones.

Gorp. In backpacker’s parlance, “gorp” is a catch-all word for several high-energy trail foods that you can carry in your pocket. You can buy packaged gorp of various descriptions or you can make your own—everyone seems to have his own recipe, most of which are based on chocolate, nuts, and raisins. Start with a block of sweet or semisweet chocolate; melt it down in a double boiler and throw in handfuls of peanuts, raisins, chopped walnuts, dried fruit, berries—whatever pleases you. Let it cool and break it into pieces.

Food to Carry Into the Wilderness

Three basic questions to ask in deciding what food to carry: How much does it weigh? How much energy will it provide? What is its nutritional value?

Food energy is measured in calories. Most healthy people burn about 4,000 calories a day on the trail; if you pack 2 lb. of food for each day, it must deliver an average of 125 calories per ounce to replace this expenditure. Only dry foods and oils are so rich.

About 10 percent of the food energy should be in the form of protein (P) to rebuild body tissue, and at least 20 percent should be fat (F) for long-lasting energy. Carbohydrate energy (C) is readily available but short-lived; that which is not quickly used is stored as body fat—a problem for sedentary dieters but of no concern to a hardworking backpacker. In the listing at right, each food’s major nutrients are given according to the order in which they predominate; minor nutrients (less than 25 percent) appear in parentheses. Seasonings and spices have little or no food value, but do not ignore them; flavorful food can be a great morale booster.

Most camping supply stores stock a variety of freeze-dried meals in foil packets. They are lightweight, nutritious, and easy to prepare but quite expensive.

| Provisions | Calories per ounce |

Major nutrients |

|---|---|---|

| Bacon | 177 | F |

| Beans, (navy, dried) | 97 | C(P) |

| Beef (chipped) | 58 | P |

| Bouillon cubes | 34 | P |

| Cheese (Cheddar) | 113 | FP |

| Chocolate | 147 | CF |

| Coconut (dried) | 188 | FC |

| Cornmeal | 103 | C |

| Drink mix | 168 | C |

| Eggs (powdered) | 168 | PF |

| Flour (soy) | 120 | PC(F) |

| Flour (wheat) | 100 | C(P) |

| Fruit (dried) | 100 | C |

| Gelatin (dry) | 95 | P |

| Honey | 86 | C |

| Jerky | 102 | PF |

| Macaroni | 105 | C(P) |

| Margarine | 204 | F |

| Meat bars | 171 | FP |

| Milk (dried whole) | 142 | CFP |

| Milk (soy) | 122 | PC(F) |

| Oatmeal | 111 | C(P) |

| Oil (cooking) | 250 | F |

| Peanuts (roasted) | 166 | FP(C) |

| Peas (dried) | 99 | C(P) |

| Pork (salt) | 213 | F |

| Potatoes (dehydrated) | 103 | C |

| Prunes (dried, pitted) | 73 | C |

| Pudding mix | 102 | C |

| Raisins | 82 | C |

| Rice (brown) | 102 | C(P) |

| Sausage | 110 | F(P) |

| Soup (dehydrated) | 105 | CP |

| Sugar | 109 | C |

| Sunflower seeds | 159 | FP(C) |

| Tomato crystals | 86 | C(P) |

| Walnuts | 159 | F(C)(P) |

| Wheat germ | 103 | CP(F) |

Breakfast

You may make do with toast and coffee at home, but a day of packing a load in the wilderness should start with a hearty, well-balanced meal. The old standby, bacon and eggs, provides fat and protein. Stewed fruit and foraged berries are for vitamins, quick carbohydrate energy, and a taste of sweetness. Oatmeal or other hot cereal, biscuits, and pancakes provide additional carbohydrates and help keep your digestive system functioning smoothly. Coffee or tea serve as psychological and physiological pick-me-ups to get you started.

For buckwheat pancakes for two mix:

1 cup buckwheat flour

½ cup wheat flour

½ cup cornmeal

½ cup wheat germ

½ cup whole dry milk

2 tbsp. powdered egg

2 tsp. baking powder

1 tsp. salt

For convenience, premix the ingredients at home and pack in a labeled plastic bag. Add 2 tbsp. of oil and 2 to 3 cups cool water; then beat to a thin batter. Cook in a hot, oiled pan.

Cooking with foil

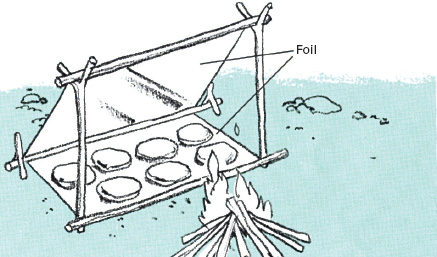

Aluminum foil has many uses. Bake a potato, yam, or wild root by wrapping it in foil and burying it among hot coals for half an hour. Turn a wire grill into a griddle with a sheet of foil turned up around the edges. Line a leaky pot with foil, or with the help of a few short sticks improvise a reflector oven. (For use of oven, see Baking Bannock Bread, p.422.)

Spark Your Diet With a Free Feast of Wild Greens

To pack a head of lettuce into the wilderness is ineffi-cient and unnecessary. Not only is there an abundance of edible wild greenery, but much of it is tastier and more nutritious than its cultivated counterparts. You need not become a field botanist to recognize such commonplace delicacies as dandelions, chickweed, and clover, but the more you know the wider your choice will be. And be sure to carry a clearly illustrated plant iden-tification guide, since some plants are poisonous.

Among the raw greens that are savory in salads or refreshing to munch on the trail are the young leaves of chicory, mint, mustard, orach, purslane, rock cress, several kinds of sedum (especially Sedum rosea, known as roseroot for the odor of its thick root), sheep sorrel, shepherd’s purse, spring beauty, watercress, wild lettuce, and any of the several plants known as scurvy grass because of their high vitamin C content. Each has its own special flavor and texture. The older leaves of many of these plants are equally appetizing when cooked and served like spinach. Some—such as shepherd’s purse, chicory, and mustard—become tough and bitter with age; to correct this fault, boil the leaves until tender, drain, and boil again in fresh water. Other plants whose leaves need this double cooking include burdock, jewel-weed, marsh marigold, milkweed, and pokeweed. Cook the leaves of the remaining plants mentioned above— as well as those of coltsfoot, dock, plantain, and the wild spinach known as lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album)—just once, quickly, in a little boiling water.

Dandelions grow almost everywhere. The tender young leaves and unopened buds, delicious raw or steamed, are among the richest sources of vitamins A and C. Older leaves, boiled twice to remove bitterness, taste like Swiss chard but are somewhat more flavorful. To make a delicate tea, drop only the petals from 10 flowers into a cup of boiling water; let them steep until the tea’s flavor pleases you.

Clover is protein-rich but difficult to digest raw. Indians dipped its leaves and flowers in salted water to prevent flatulence; boiling is a surer way. To make a tasty clover dish for four, melt 4 tbsp. margarine or butter in a frying pan; stir in 6 cups clover greens and flowers; add ½ cup water; cover and cook until wilted, stirring occasionally. For a chewy texture include sweetish clover roots as well.

Common chickweed is found in moist meadows, fields, and woods throughout North America. Its small, sharp-pointed leaves, rich in iron and vitamin C, stay fresh and green beneath winter snow. These leaves and the tender tips of the plant’s long, sprawling stems are year-round food sources. They may be eaten raw or steamed—do not overcook or the delicate flavor may vanish completely.

Wild onions —including leeks, chives, and garlic (shown here)—can be prepared and eaten in all the same ways as their civilized cousins-. Flavor and potency vary tremendously; sample a small amount before deciding whether to use a plant as food or for seasoning. Caution: Eat nothing that looks like a wild onion but does not smell like one–it could be either of two very poisonous plants, death camas or fly poison.

Roots, Shoots, Stems, and Fruits

In spring the tender young shoots of calamus, catbrier, evening primrose, and wild asparagus are good cooked or raw—as are rose hips and the juicy berries of the wintergreen, left on the plants from the season before. Milkweed shoots can double for asparagus; the fat flower buds of summer make a broccolilike dish; young seed pods can serve the same culinary purposes as okra. Summer and fall offer a vast array of fresh fruits, nuts, and berries to fill out a meal or munch on the trail.

The only totally inedible part of the burdock is the familiar brown burr that sticks to your clothes, although most of the rest is enclosed in a bitter husk. Peel and cook first-year roots (those without flower stalks) as you would parsnips. Peel the rhubarblike leaf stalks in spring and eat them like celery, raw or stewed; unlike rhubarb, the leaves can also be eaten without fear of poison. In summer the white inner pith of the thick flower stalk makes an excellent replacement for potatoes. Slice the stalk crossways and bake, fry, boil, or roast.

Other potato substitutes include the peppery roots of the evening primrose, turnip-flavored groundnuts, the tiny chestnutlike tubers of spring beauty, and the giant wild potato (actually a wild yam), whose tuber may weigh 20 pounds or more. The starchy roots of such aquatic plants as arrowhead, bulrush, and water lilies are best gathered during the colder months, although Indians harvested them with their toes in summer by wading among the plants and collecting the firm young tubers that bobbed to the surface.

Salsify roots taste surprisingly like oysters. For a landlubber’s oyster stew, scrub and scrape several tender first-year roots and slice them crosswise into ¼-in. pieces. Barely cover with milk or soy milk; add salt and seasoning; cover and stew until tender.

Tea and coffee substitutes

Fresh wintergreen leaves steeped in boiling water make a fragrant tea. Strangely, however, black birch twigs are richer in wintergreen oil than wintergreen is; pour hot (not boiling) water over about a quart of them broken into 1-inch lengths, let steep until cool, then strain and reheat. The leaves of all members of the mint family, including catnip (you can recognize them all by their square stems), can be brewed fresh for an invigorating tea; just pour boiling water over them and let steep until the flavor pleases you. Brew coltsfoot leaves the same way. Leaves of Labrador tea, New Jersey tea, and two evergreen hollies—cassina and inkberry—must be dried before a fire or in a reflector oven before they are crumbled and brewed like tea. (The hollies are among the few North American plants that contain caffeine.)

For a caffeineless coffee, roast the roots of chicory, chufa, dandelions, or salsify over a low fire; grind and brew. Sunflower seeds can be used too, as can the fruits of cleavers, picked and roasted in early to midsummer.

Foraging for Flour And Emergency Rations

It takes time and energy to prepare flour from any wild source except cattail pollen. If you are in no rush, it is time well spent, both for the unusual flavors of foraged flour and to save packing pounds of processed flour. Easiest to prepare is flour made from the tubers of such plants as arrowhead and chufa. For immediate use, crush them and put the pulp in a container of cold water. Seal it and shake vigorously, then filter out the fibrous waste and allow the starchy residue to settle. Pour off the water, add more cold water, and repeat the process. Continue until the water no longer feels slimy. You can drain and use the flour as is (allowing for the water it contains) or dry and grind it for future use.

To make a flavorful meal—and simultaneously obtain cooking oil—from walnuts, butternuts, hickory nuts, or others, smash them with a rock and boil slowly, shell and all. A mixture of meats and oil will rise to the top; skim it off and filter or pick out the meats. Dry the meats before a fire and grind them to the consistency of corn-meal. (For nut butter, crush the meats into the oil.)

To grind flour from seeds is a hard job even with a mortar and pestle. Doing it between two rocks leads one to marvel that primitive peoples ever got around to baking at all. The result, however, is the closest wild approximation to conventional flour, in texture if not taste. For a hint of wild flavor, grind just a handful of bulrush, dock, or lamb’s quarters seeds, and mix with wheat flour. First thresh the seeds to remove them from their husks; then winnow to get rid of the chaff. Threshing methods vary. Some seeds, such as green amaranth, require nothing more than rubbing them briskly between your hands. Others, including purslane and shepherd’s purse, must be treated more roughly, up to and including beating them with sticks and treading them underfoot. In order to winnow the threshed seeds, pour them back and forth between two containers and let the breeze carry off the chaff.

To grind flour from seeds, nuts, or roots, look near running water for a large, nonporous rock that has been hollowed out to the shape of a bowl. For a pestle choose a smooth, round stone that fits your hand comfortably.

Using the Fruit of the Bountiful Oak

The plentiful acorn was a dietary staple of several native American cultures. To shuck acorns for use, crack the thin shells lengthwise (pliers facilitate the job), then squeeze the tips to pop the meat out whole. To leach out the bitter tannin, boil the meats for about two hours, changing the water whenever it turns yellowish; then dry and pound into fine meal. Or you can dry and pound the meats first, place the meal in a porous cloth bag, and pour boiling water through it. Use as you would cornmeal, or mix into any flour for a nutty flavor.

Bannock Bread

Nothing is more welcome at a fireside meal than fresh bread. Happily, baking it is one of the easiest jobs of campfire cookery. Start with the following ingredients:

Mix the ingredients gently with enough water (about ¾ cup) to form a firm dough. Mold quickly and with as little handling as possible into a loaf 1 in. thick. Dust the loaf with flour, then cook it by any of the three following methods.

Covered pot. Place loaf in pan. Put a few stones in bottom of large pot and set loaf on stones. Cover pot and place on hot coals; heap more coals onto lid. Bake 30 minutes or until done. Test by inserting a twig; if dough adheres, bake longer.

Frying pan. Place loaf in prewarmed, greased pan. Hold over fire until crust forms on bottom; then flip and brown the other side. Place over coolest part of cooking slot and turn loaf from time to time until done.

Reflector oven. Put loaf on foil sheet and set on base or shelf of oven; place oven about 8 in. from fire. Maintain steady flame for 20 to 30 minutes, turning loaf occasionally until it is brown all around and done inside.

Easy Acorn Cakes

Combine ingredients and beat to stiff batter. Let stand one hour; then heat 3 tbsp. cooking oil in frying pan. Drop batter into pan to form cakes about 3 in. across. Reduce heat (or put pan at edge of cooking slot), and brown cakes slowly on both sides. Eat hot or cold. Acorn cakes will keep for days.

The cornucopious cattail

There is an old saying that you can use every part of a pig but the squeal. Cattails are even less wasteful—they have no squeal. All four native American cattail species are edible, and all were regularly used by Indians and early settlers as year-round sources of food and fiber. They are easily recognized by their tall, stiff flower stalks, which arise among clusters of sword-shaped leaves. The flowers at the tops of these stalks form two sausagelike sections—pollen-bearing male flowers above and seed-producing female flowers below. Cattails grow in marshes and in the shallows of lakes, rivers, and estuaries throughout the country.

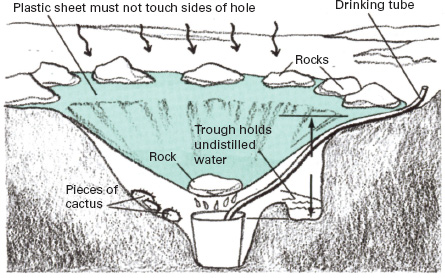

In Case of Need

Cactus. All fruits and fleshy parts of all cacti are edible; some are quite tasty. The best part is the fruit, or tuna, that grows from between the pads of prickly pears (Opuntia). Slice off ends, open husk lengthwise, and scoop out pulp. Protect your hands from the spines while working. To eat pads themselves, first burn off spines, then slice through husk; pulpy core is good raw or cooked. Get water from cactus with the aid of a solar still (p.424).

Thistle. This common biennial is a fine source of food from spring through fall. In its first year the plant forms a rosette of tender but spiny leaves; trim the spines and eat the leaves raw or steamed. During the second year a purple flower appears on the plants atop a spiny stem that tastes rather like an artichoke; peel, slice, and boil it. The root is more nutritious than tasty; eat it raw or cooked. First-year roots are best.

All parts of chicory are edible. The young leaves can be eaten as a salad or boiled. The roots can be cooked like a vegetable or used as a coffee substitute when roasted until dark brown and then pulverized. Look for chicory in fields, weedy lots, or along roads.

Poplar. The inner bark of poplars—including trembling aspens of the Rocky Mountains and cot-tonwoods of the South and Midwest—kept many a frontiersman alive for weeks at a time. It can be eaten fresh, brewed into tea, cut into strips and cooked like noodles, or dried and ground into flour. All are nourishing, as is the inner bark of the willow, a close relative. Pines, birch, and juniper also have edible inner bark.

Sources of Meat When Survival Is in Doubt

The meat of all healthy birds, insects, and mammals is edible. So is that of most reptiles and amphibians. The fat and protein they contain could mean the difference between life and death for one who is lost or stranded in the wilderness for a long time. If you are proficient in the use of a throwing stick, bolo, sling, spear, or bow and arrow, you will probably have little trouble improvising your weapon from natural materials and hunting with it. If not, it is too late to start practicing—you will do better to spend your energy gathering insects and grubs, fishing, or trapping reptiles, birds, and small game.

Grasshoppers, locusts, katydids, crickets, and cicadas are all excellent protein sources and good fish bait. It is easiest to catch them in early morning, while they are still sluggish from the nighttime chill. Like all insects they must be cooked before they are eaten to rid them of parasites. Pull off the wings, legs, and head and roast or steam the bodies. To gather a meal of ants, sink a steep-walled container, such as a cup or jar, into the top of an anthill so its rim is level with the surface of the mound, then use a stick to stir up the den. Hundreds of ants will fall into the container. Grubs and caterpillars are also rich food sources, but avoid caterpillars bearing hair or fuzz—many are poisonous.

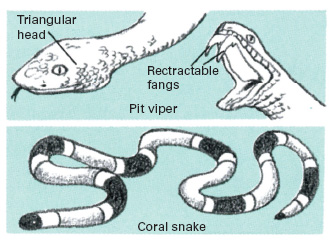

Lizards are hard to catch, and few are meaty enough to be worth the effort. Snakes, however, are almost all meat and are easily clubbed or caught with a long stick. Cut off the head; skin and eviscerate the body. Cook by roasting or boiling—the flavor is not unlike catfish. Poisonous snakes are as edible as any other (the poison is all in their heads), but unless you are an experienced snake hunter the danger can be greater than the reward. Frogs are easily caught with a long, sharp stick (notch a barb onto the end) or even with your bare hands, particularly if you hunt at night using a headlamp or flashlight. (Note, however, that light-hunting is illegal except in case of a real emergency.) Skin the frogs before cooking them. Avoid toads; their irritating skin secretions can easily spread into the meat.

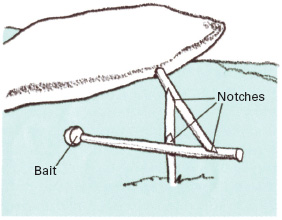

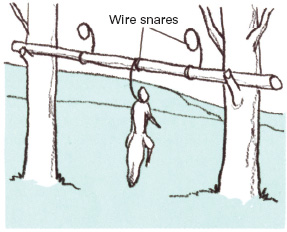

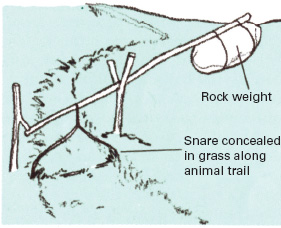

It is also illegal to hunt with snares or traps except in emergencies. You may be able to club such slow-moving animals as porcupines, opossums, or groundhogs, but if your life hangs in the balance it is permissible to set traps. The simplest of these are deadfalls, in which a flat rock, large enough to kill a small animal, is supported by a baited trigger mechanism made from sticks. Snares made from wire or cord can be set for rabbits, squirrels, or other small game along paths that they normally follow in the course of their day-to-day lives. (For the finest source of protein, see Fishing, pp.436–441.)

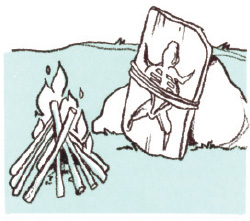

To cook small game, such as rabbits or squirrels, first skin and eviscerate animal. Spread the carcass flat on a large rock or piece of hardwood, lash it in place with wire or green vines, and prop it up before an open fire. Another method is to pack the carcass in clay and bury it in hot coals to bake for an hour or so.

Traps and snares

Figure-4 deadfall is a good trap for such foragers as ground squirrels and other large rodents. Use a flat rock or log heavy enough to kill prey. Be sure bait is securely attached to trigger.

Squirrels are adventuresome. Rig up wire noose snares firmly along pole and place between two trees where you have seen squirrels at play. Always remove traps when you no longer need them.

Rabbits tend to follow the same route daily. Rig a lift snare along their customary path. Fashion a noose from wire, cord, green vines, or twine made by twisting tough fiber of thistle stems or milkweed.

How to Survive The Unexpected

“Nature is stern, hard, immovable, and terrible in unrelenting cruelty [but] she has in store food, fuel, and shelter which the skillful, self-reliant woodsman can wring from her savage hand with ax and rifle.”

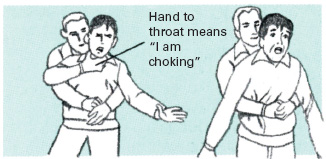

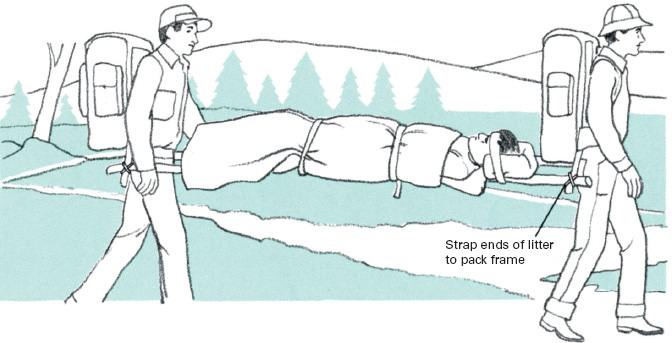

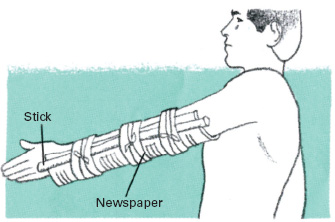

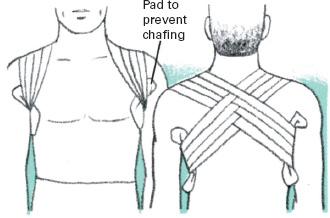

—Nessmuk