Fishing

Freshwater Angling Means Catching Fish With Hook and Line

Fish are notoriously brainless creatures against whom anglers have been matching wits with varying degrees of success for ages. Three distinct skills are involved in winning this contest: attracting the fish to take the bait, setting the hook, and landing the fish.

Though blessed with little intelligence, all fish are experts at recognizing two things: food and danger. The longer a fish has lived, the more expertise it is likely to possess. They are seldom fooled by things that move unnaturally in the water, although they may strike at lures that in no other way resemble anything that ever lived. Whether you are using live bait or lures fashioned from wood, cloth, feathers, metal, plastic, rubber, or hair, study what the fish are feeding on and try to match it. If this does not work, try something else; fish are creatures of habit, but their dietary habits often change without notice.

Setting the hook takes a delicate touch, particularly if you are using artificial lures. Most fish taste-test a bit of food before swallowing it. You must sense the moment when your quarry has taken the bait firmly in its mouth, then give a slight jerk on the line—too soon and you will snatch the bait away, too late and the fish may become suspicious and reject it.

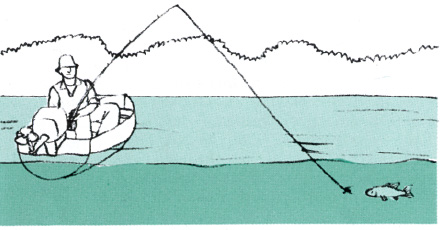

Finally comes the part of the contest that most fishermen consider the height of the sport—playing the fish. Usually this is just a matter of reeling in a small or medium-sized fish, but when you hook a big one the fight can last for quite a while. The trick is to maintain enough tension on the line so the fish cannot throw the hook but not to exert so much stress that the line will part or the fish’s flesh will be torn.

“Waiting for a Bite” by Winslow Homer. The fisherman’s cardinal virtue—patience—is more important than fancy equipment.

Angling With Live Bait

The novice fisherman’s first mistake often comes in baiting the hook—fearful of losing the bait, he impales it so securely that it cannot move and dies quickly. Whatever bait you are using, insert the hook carefully, so as to do the least damage and to allow free movement in the water. Do not bother to conceal the point of the hook; the fish has no idea what it is.

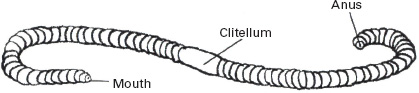

Earthworms are so successful at attracting fish that they have earned the common name angleworms. Pass the hook once through the clitellum, the tough collar near the head, and let the worm sink naturally to the bottom. When fishing for bass, lake trout, and other large fish, night crawlers are better than plain worms. Stalk these largest members of the earthworm family at night with a flashlight. If you find a night crawler half in and half out of its hole, hold it down with a finger, and with the other hand pull gently where it emerges from the ground. The worm will contract and pull back; wait until it relaxes, then pull again. Two or three such maneuvers should win the whole worm.

Nymphs are the underwater larval stage of many insects. They are a large part of the diet of rainbow and brook trout. Dobsenfly nymphs, known as hellgrammites, are a favorite of bass; they are about 2 inches long and are armed with sharp little pincers. Collect nymphs with a fine-mesh net from the shallows of lakes or gravelly areas of fast-moving streams. Hook them through the wide part of the body just behind the head.

Earthworms, including night crawlers, are the commonest bait.

Grasshoppers and crickets are good late summer bait. Insert the hook under the mouth of either insect and pass it beneath the hard ventral plate so that it emerges just in front of the large rear legs.

Minnows, frogs, and crayfish are the preferred food of most large lake fish. Hook a minnow through the lips and let it swim, pulling it toward you from time to time in a series of short, darting motions. Hook a frog through both lips or through the tough skin at the base of the back. Crayfish are best hooked through the tail.

Fishing Through the Ice

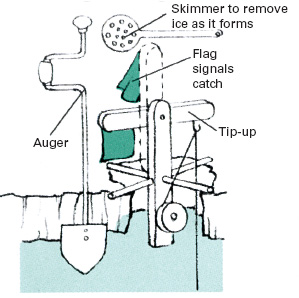

Tip-up’s balanced crossarm signals a bite. Most fish feed in schools, so several holes may be struck at once.

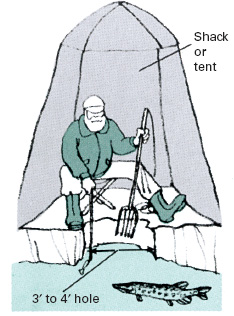

Spearfishing for pike takes patience. Use decoy minnow to lure fish. Inside a dark tent you can see into water.

When ice forms, large fish move to the bottom. They continue to feed, but for the most part they eat what comes to them rather than hunting for food—an exception is the northern pike, which often prowls the shallows in search of prey. Use an ice auger or spud (a heavy long-handled chisel) to make a hole in the ice about a foot across. Test the depth with a weighted line, then bait a hook with a minnow, meat, or lure. Use monofilament line to drop the bait to within a foot or so of the bottom. You can fish one hole with a short rod and bobber, but for best results make several holes and rig each with a tip-up device. Waiting is more bearable in a plywood shed or tent equipped with a small stove. (For tips on ice safety, see Outdoors in the Winter, p.435.)

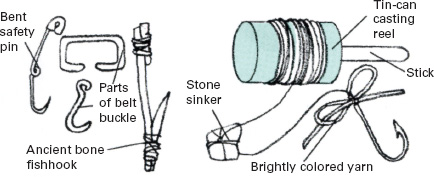

Improvising equipment

Emergency hooks can be made from pieces of bone, as the Indians did, or from safety pins or belt buckles. Lures can be fashioned from feathers, fur, yarn, and bits of foil.

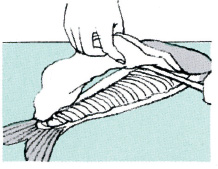

Dressing and Cooking Your Catch

A fish should be dressed for cooking as soon as possible after it is caught. Kill it with a sharp blow behind the head; then wash it in cold, salted water (about 1 tablespoon of salt per quart). Scrape off the scales with a sharp knife or scaler, working from the tail forward. To whole-dress, slit the fish’s belly lengthwise and remove the entrails. To pan-dress for frying, continue by cutting out the pelvic fins (beneath and behind the head). Cut through the backbone and down behind the pectoral fins (behind the gills) to remove the head. Cut along each side of the dorsal (back) fin and jerk it out by the roots, pulling toward the head. Rinse the dressed fish in cold, salted water. Skin catfish and eels before dressing. Slice around the neck behind the pectoral fins, secure the head on a nail or with a piece of cord, and use pliers to peel the skin whole, like turning a glove inside out.

To broil a fish over a fire, whole-dress it (no scaling is necessary) and season the cavity with salt, pepper, and herbs. Spit the fish on a green stick or metal rod and suspend it over hot coals.

To fry a fish, first pan-dress or fillet it. For a crunchy outer crust, dip the fish in milk, then in beaten eggs, and roll it in bread or cracker crumbs. Heat fat or oil in a frying pan to just short of smoking (salt pork makes an excellent frying medium), and drop in the fish. Turn when the batter becomes brown. A simpler method is to drop unbreaded fish chunks into hot fat, frying them as briefly as possible.

To poach a large fish, place it whole-dressed in a baking dish. Add chopped, sautéed carrots, onions, and tomatoes. Dissolve a bouillon cube in enough hot water to barely cover the fish. Cover and bake at 350°F. For a similar result at a campfire, wrap the fish in waxed paper, then in several sheets of well-soaked newspaper. Bury the bundle in hot coals for about 20 minutes.

Planking a fish

This favorite northwoods method of cooking whitefish works for any slightly oily fish. Make a plank by splitting a piece of hardwood that is as long as the fish and about twice as wide. Smooth its surface. While you are scaling the fish, let the plank heat near the fire.

Dress the fish by splitting it down the back so the belly skin is whole. Tack it or tie it flesh side up on the hot plank, and prop the plank up before the fire. Baste with butter, oil, or bacon grease; add salt, pepper, and herbs to taste. Turn the board occasionally to ensure even cooking.

How to fillet a fish

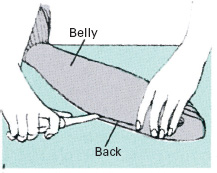

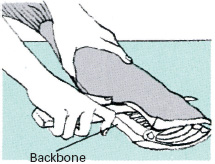

1. To fillet a large fish, first whole-dress it. Then use a razor-sharp knife to make a cut along the backbone from head to tail. Next, remove the head, cutting behind the gills.

2. Hold the knife flat. Starting at the head end, slice along the upper edge of the backbone to the tail, running the blade over the ribs.

3. Lift the boneless fillet whole from the tail end; use the knife to free any ribs that are not completely separated. Turn the fish, and fillet the other side.

4. To skin a fillet, lay it flat with the skin side down. About ½ in. from tail end, cut through the flesh to the skin; then flatten the knife and slide it forward along the skin.

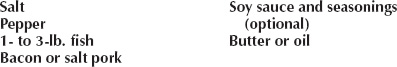

Baking a fish in hot coals

This is a simple way to cook a fish in a campfire without dirtying a pot or a pan. Whole-dress the fish; no scaling is necessary. The head may be cut off or left on.

Rub salt and pepper in the cavity (along with other seasonings if you wish). Wrap a slice of half-cooked bacon around fish, or use salt pork. For an extra tang, sprinkle on a few drops of soy sauce. Place the fish on heavy-duty aluminum foil, and put a little butter or cooking oil on top. Wrap tightly and bury in hot coals. Check after four minutes to see if it is done.

Going After Fish With Artificial Lures

You can hunt fish—rather than wait for them to seize your bait—by fly casting, trolling, or surf casting. The art of fly casting is a difficult technique to master. It calls for a long, flexible rod and a very light line, both of which allow even a small fish to put up a battle that it has a fairly good chance of winning.

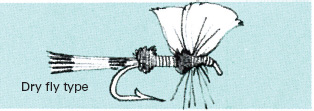

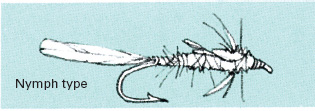

Dry flies float on the water; wet flies sink beneath the surface. Both are made from bits of feather, fur, twine, and tinsel wrapped around a hook. Dry flies simulate an insect on the water’s surface. Some wet flies are meant to imitate drowned insects; others mimic nymphs or shrimp; and some, called streamers or bucktails, look like minnows in the water.

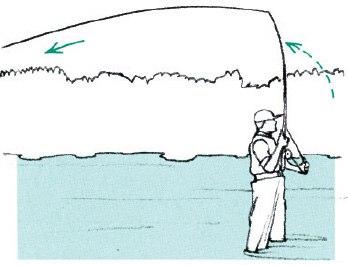

The secret of casting a dry fly is to drop it so gently on the water that nothing disturbs the surface except the fly’s bristly hackles, which look to a fish like an insect’s feet rippling the mirror that is his sky. If there is a current, cast the fly upstream and let it ride the water down while you keep the line out of the water. In a lake with no current, let the wind move the fly a little, then pull it back and cast again. A fish may leap from the water to take the lure, or the lure may disappear in a slight splash. In either case, the hook must be set quickly, before the fish has a chance to realize that he has only a mouthful of feathers rather than an insect.

Cast a wet fly across the current or slightly downstream, and let it run in the water until it reaches the end of the line; then retrieve it and cast again. Before you retrieve a bucktail or streamer, let it “swim” minnowlike against the current for a while.

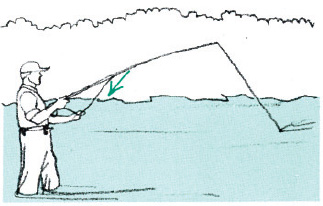

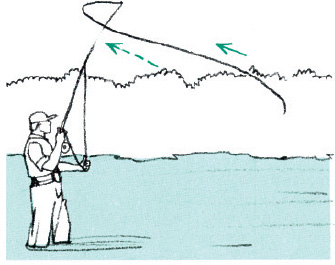

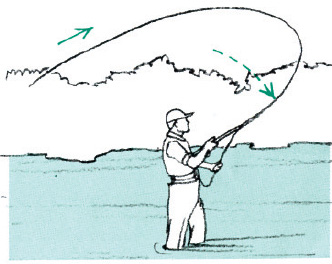

Fly Casting Is All in the Wrist

1. Before casting, take back a few feet of line with your hand. To add line, take it from reel.

2. Bring the rod to vertical with your wrist. Hold extra line in your other hand.

3. Flick the rod forward just as the line is extended straight out behind you.

4. Release slack line as the spring of the rod sends the lure to settle gently on the water.

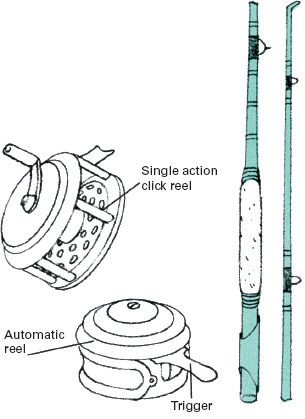

Fly rod and reel Fly rods are generally 6 to 9 ft. long and made of light, flexible split bamboo or fiberglass. Reel can be hand operated or spring driven for automatic take-up.

Four types of flies

Fan-wing royal coachman is an adaptation of a fly first tied in the 1830s by Tom Bosworth, coachman to Britain’s royal family.

Damselfly is made of reddish-brown fox fur and feathers of English grouse to simulate nymph stage of real insect.

Professor was first tied around 1800 by Professor John Wilson, of Edinburgh University, using a buttercup for the yellow body.

Golden darter simulates a minnow in the water. A bucktail is a streamer with wings of anima hair instead of feathers.

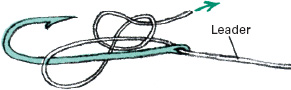

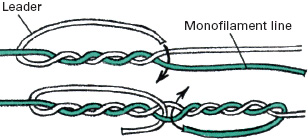

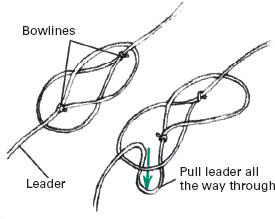

Attaching a transparent leader

Use turtle knot to tie 3- to 5-ft. nylon leader to fly. Half-hitch at the end of the line prevents the knot from working loose.

Tie blood knot as shown or twist lines together, then pass ends through center. Finish knot by pulling ends tight.

Fish may be frightened by the vibrations of a boat’s motor. It is usually best to use the motor to reach your fishing spot, then proceed by paddling or rowing. If you are alone, the best alternative may be to drift and cast your lure.

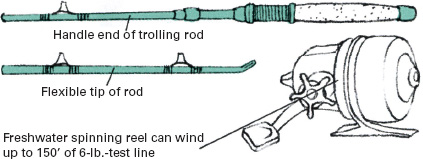

Trolling rod and reel

Medium-weight spinning rod 5 to 7 ft. long is best for most trolling. For muskies and other big fish, use long, sturdy rod with flexible tip. Adjustable drag setting on reels allows you to vary the amount of pull needed to take out line.

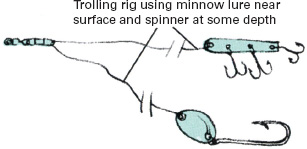

Trolling for the Big Ones

Trolling means dragging a lure through water to simulate a minnow or other tasty morsel. It is generally done from a boat, either by pulling the lure behind or by casting from a stationary boat and reeling the lure in. When fishing strange waters, it is a good idea to pull the lure behind you through some likely places until you find out where the fish are, then drop anchor and cast. Because trolling is the way to go after big fish, such as musky and lake trout, which lurk in deep water, it calls for a heavy-duty line, a strong reel, and a stout rod.

Lures range from highly realistic plastic reproductions of living creatures to bizarre shapes and forms that resemble abstract sculptures to which feathers and beads have been added as decorations. Some ride beneath the water and some skim the surface. Some are designed to zigzag from side to side like darting fish. Others bob up and down like frogs or aquatic animals. Still others, known as wobblers, have a lurching action that suggests tipsy or injured fish. The simplest lures are shiny oblong bits of metal, known as spoons because of their concave shape. Spoons are wobblers that attract fish by reflecting light in all directions as they spin and gyrate; they can be used alone, in conjunction with another lure, or even with live bait.

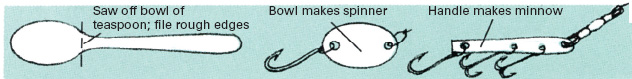

How to make two spoon lures from a real spoon

You can turn a teaspoon into a spinner by breaking off the handle and wiring a swivel onto the spoon. Use it to enhance another lure, or wire a hook on and use it alone. The handle becomes a minnow when you wire a swivel to one end; add a hook to one end and double hooks to the bottom.

To attach leader to line, tie a bowline in each (see Wilderness Camping, p.410) and engage loops.

Surf Casting From the Ocean Shore

Surf casting is a way to go after ocean fish without using a boat. It involves the use of a heavy rod, a large spinning reel, and a long, strong line to reach fish hundreds of feet out. The technique varies, depending on whether you are using live bait or artificial lures. With live bait a heavy sinker is attached to the line to hold it to the bottom; you throw the sinker and bait as far as you can and then wait for a fish to accept the offering. Artificial lures are used in the same way as in trolling. Cast as far out as you can, then reel in slowly and steadily to keep the lure moving like a small fish swimming in the water. The lures are larger than freshwater lures, and spoons and spinners are almost always attached.

The best times for surf casting are during the first two hours of an incoming tide and the last two of an ebbing tide. When either condition coincides with a full moon, the situation is ideal; small fish are drawn closer to the shore, and they are followed by the large, hungry predators that are your prey.

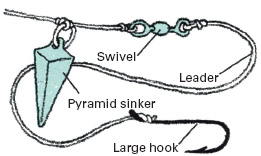

Surf-casting rig for live bait

Attach a heavy pyramid sinker about 3 in. from the end of the line. Use a swivel to attach a 12-in. leader of wire or leather with a large single or double hook at the end. For bait use shrimps, crabs, or other bottom dwellers that are common in the area where you fish. Insert hooks carefully to allow the freest possible motion.

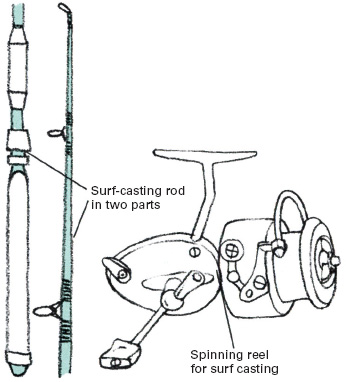

Rod and reel for surf casting

Surfcasting rods are heavy, 8 to 12 ft. long, and made of fiberglass or split bamboo. Heavy-duty spinning reel with adjustable drag should be able to wind 400 to 500 ft. of 18- to 22-lb.-test monofilament line.

A Gallery of Favorite Fish And Water Creatures

Wherever water flows, a human being has no excuse for starving to death. At least some of the fish and aquatic animals listed on these pages are to be found in almost any permanent body of water in the country. The trick is to know which fish are likely to inhabit the waters where you are and to find the best way to go after them. In mountain streams trout are the best bet. In slow-moving rivers of the Midwest and South catfish are the surest food source. In northern lakes pikes and lake trout are the sportsman’s favorite, but sunfish, crappies, and perch are easiest to catch. Along the seashore wait for low tide and gather a feast of shellfish.

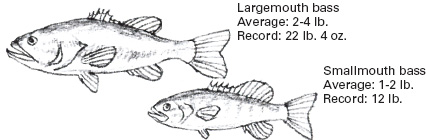

Bass. Largemouth bass frequent lakes with heavy vegetation and the backwaters of slow-moving rivers. They eat almost anything that moves; try various live bait, lures, and flies. Cast near weeds, lily pads, and stands of cattail early and late in the day; troll in deep water in midday heat.

Smallmouths are prevalent in cold, clear lakes and cool, rocky streams. They are also omnivorous but prefer smaller prey. Flycast with wet or dry flies, troll with lures and spoons, or use live bait. Both types of bass strike quickly and fight to the end. The meat is flavorful broiled, baked, grilled, or fried.

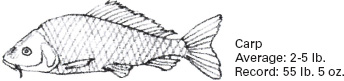

Carp. This slow-moving bottom feeder thrives in many polluted waters where other fish cannot survive. Still-fish or troll with earthworms, pieces of meat, or doughballs. Carp may mouth and drop a piece of food several times before finally accepting it, so wait to set the hook until the bite is firm. Skin a freshly caught carp with a sharp, razor-thin blade by shaving off both the scales and skin from the tail forward. Fry, bake, broil, or—in the case of a very large fish—poach your catch.

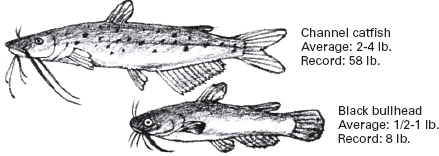

Catfish. These bottom-feeding scavengers detect food with their long whiskers. One or more of the many catfish and bullhead species exist in nearly every body of water in the country. Troll or still-fish for them, using a stout pole and live bait or a piece of dead meat. They have also been known to bite on blobs of dough, cheese, chewing gum, and laundry soap. Skin before cooking; bake, grill, panfry (dredge in flour or cornmeal), or cut into 1-in. cubes and make chowder or gumbo.

Crappie. Look for crappies near weedy shallows of streams and ponds in the Midwest, South, and East. They travel in schools, so where you catch one there will be more. Use live bait; or cast dry flies, nymphs, and small streamers. They may also strike small spoons and spinners. The delicate meat is best panfried.

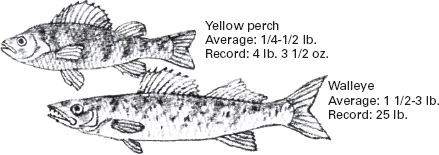

Perch. Schools of yellow perch swarm in lakes, ponds, and rivers in all but the warmest states. Still-fish for them with live bait, or cast wet flies and small streamers. Pan-dress and fry in butter.

The walleye, often called a walleyed pike, is the largest of the perches. Walleyes school in cold lakes and rivers. In warm weather, troll deeply during the day with live minnows or lures; in the evening, cast large streamers, lures, or live minnows into shallower, weedy waters. In winter both walleyes and yellow perch are popular with ice fishermen.

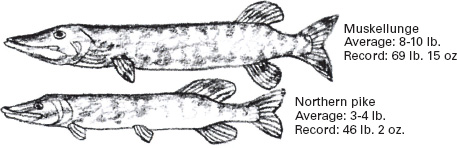

Pike. Northerns and muskies are solitary predators that attack their prey with a swift lunge from the side and run a short distance with it before they turn it in their mouths to swallow it. Wait to set the hook until this first run is over.

Muskies dwell in the deep waters of cold northern lakes. Use a strong rod, 25-lb.-test line, and wire leader (because of their sharp teeth), and cast for them with large lures or live bait. The meat is dry and bony but flavorful; marinate it in a mixture of oil, lemon juice, and salt before cooking.

Northerns lurk among weeds and reeds in clear, cold lakes. Cast or troll with lures or live bait, such as frogs or large minnows. Bake, fillet and fry, or poach the meat.

Salmon. These ocean fish return to freshwater rivers to spawn. Atlantic salmon enter rivers mostly in spring or fall; Pacific species, such as the coho and chinook, during late summer and fall. Cast for Atlantic salmon with wet or dry flies. For Pacific salmon troll deeply with lures or live bait. Landlocked salmon are Atlantics that never go to sea; they do not reach the same size as the ones that do. (For instruction in curing and smoking your own salmon, see Preserving Meat and Fish, p.226).

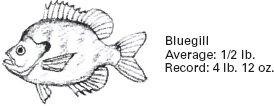

Sunfish. Bluegills, green sunfish, longears, pumpkinseeds, red-ears, and rock bass are among the many popular kinds of sunnies. They are found in the warm shallows of ponds and lakes everywhere, living on worms, insects, and nymphs. Still-fish for them with live bait, especially small earthworms; or cast small wet or dry flies. Broil them whole over a fire; or pan-dress, dust with cornmeal or flour, and deep fry in fat or oil.

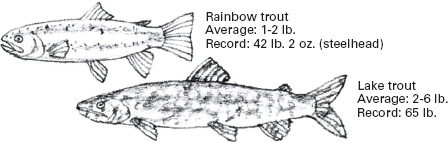

Trout. Brook trout, cutthroats, goldens, and rainbows inhabit fast-moving streams and clear lakes, living largely on insects, nymphs, and small minnows. They are the dedicated fly caster’s favorite opponents, often taking the lure with a spectacular leap and always putting up a momentous fight. The meat is sweet and tender, whether broiled whole, planked, or panfried.

Lake trouts are the giants among trout. They live in the deep waters of large northern lakes—the bigger the lake, the larger the trout— always seeking a water temperature of 40°F to 45°F. In summer troll for them at a depth of 50 ft. or more; in spring and fall they may be near the surface; in winter they are caught through the ice at various depths. Use large bait fish or lures sparked with spoons. The meat is rich in flavor. Fillet for frying, or whole-dress and bake or poach.

Shellfish for Good Eating

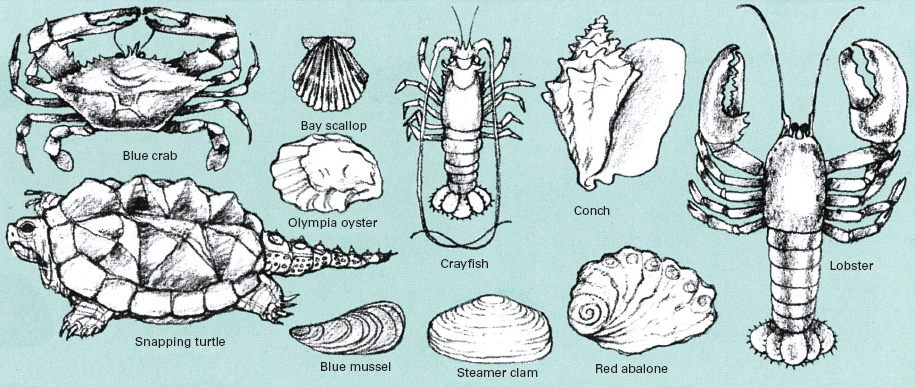

Some of the most prized gastronomic delicacies are shellfish found in shallow waters and along the shores of oceans, lakes, and streams. Many can be eaten raw; others should be cooked, both for digestibility and to bring out the flavor. Before you forage for any clams, oysters, or other shellfish, however, check local ordinances; the taking of many of these creatures is regulated by law. The easiest cooking method is simply to bring a pot of water to a boil and throw the shellfish in. A lobster will be done in about 10 minutes; crabs take about 20 minutes. Streams and lake shores are the home of the crayfish, or crawdad. Set traps for these small cousins of the lobster or, if you are quick, catch them by hand. Cook them as you would lobster; they will be done within five minutes. Of the many freshwater turtles found in lakes, ponds, and slow-moving rivers, the most flavorful are the snapping turtles. Kill them by turning them on their backs and chopping off their heads, or poke a sharp stick in through the openings of the shell. Cook them in their shells over a bed of coals; or open them up, take out the meat, and make a soup; or you can also simmer them in a pan with onions and carrots.

You can often find clams, mussels, abalone, and scallops clinging to rocks at low tide. Or explore tidal flats for these creatures as well as for conches and crabs.

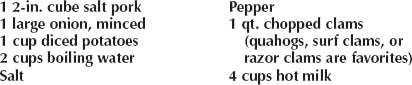

To make traditional creamy New England clam chowder, use the following recipe:

Sauté salt pork in a deep pan until crisp. Add minced onion and cook until brown. Remove pork and set aside. Add potatoes, boiling water, salt, and pepper to taste; simmer about 20 minutes—until potatoes are done but firm. Add chopped clams, salt pork, and hot milk; simmer about three minutes. Pour melted butter over the top. Makes six servings.

Many kinds of shellfish and turtles are delicious to eat. The shells of abalone and conch also make beautiful decorations.

Some common shellfish and where to find them

All healthy shellfish are edible if they are taken alive and consumed quickly before spoilage begins. There is danger, however, in taking shellfish from polluted waters or waters affected by microorganisms responsible for the “red tide.”

Abalones. Large univalve (single-shell) mollusks cling to rocks in Pacific coastal waters. Pry off with tire iron or large chisel.

Clams. Bivalve (double-shell) mollusks burrow in sand. Many types are edible, including the quahog, razor clam, soft-shell (steamers), and geoduck (a Pacific Coast species that reaches 12 lb.). Look for tiny holes in sand and dig at once on seaward side; or use rake or bare feet to locate clams in shallow water.

Conches. Large spiral univalves of southern waters; catch by diving in shallow salt water or by exploring tidal flats.

Crabs. Crustaceans found in all coastal waters. Blue crabs are favorite, especially in the soft-shell stage when the shell is being shed. Catch in traps or nets, or tie a piece of rotting meat to a line and drop it to the bottom from a pier at high tide.

Crayfish. Crustaceans found in fresh and brackish waters, hiding beneath rocks and logs. Trap them, or catch by hand.

Lobsters. Spiny crustaceans caught in deep Atlantic coastal waters with the aid of traps called lobster pots.

Mussels. Bivalves that cling to rocks, jetties, and even fallen trees in fresh and salt water. Gather them at low tide.

Oysters. Rough-shelled bivalves inhabit coastal waters. Becoming scarce due to pollution but worth looking for at low tide.

Scallops. Small saltwater bivalves with distinctive “scalloped” shells. Gather them like clams at low tide in bays.

Turtles. Shelled reptiles that live in fresh and salt water as well as on land. Freshwater snapping turtles are tasty but dangerous; catch them by grasping the shell behind the head.

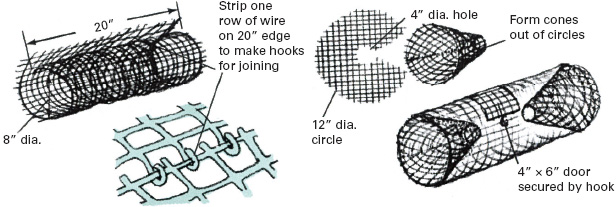

A trap for crayfish

Trap crayfish in a cylinder of ½-in. wire mesh with two conical entrances. For bait use dead fish or even a can of fish-flavored cat food punctured at both ends. When the trap is ready weight it with rocks, and set it out overnight in a stream or lake. Attach a buoy to the trap or tie it to shore to aid in retrieval.

Sources and resources

Books

Bettell, Charlie. The Art of Lure Fishing. North Pomfret, Vt.: Trafalgar Square, 1995.

Evanoff, Vlad. Freshwater Fisherman’s Bible. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1991.

Fox, Charles K. The Book of Lures. Richmond: Freshet Press, 1975.

Jorgensen, Poul. Poul Jorgensen’s Book of Fly Tying: A Guide to Flies for All Game Fish. Boulder, Colo.: Johnson Books, 1988.

Kugach, Gene. Fishing Basics: The Complete Illustrated Guide. Mechanics-burg, Pa.: Stackpole, 1993.

Leiser, Eric. The Book of Fly Patterns. New York: Knopf, 1987.