1. Understand the Analytical Task

2. Use the “Three-Pass Approach”

The SAT Essay assesses your proficiency in reading, analysis, and writing. You are given 50 minutes to read an argumentative essay and write an analysis that demonstrates your comprehension of the essay’s primary and secondary ideas and your understanding of its use of evidence, language, reasoning, and rhetorical or literary elements to support those ideas. You must support your claims with evidence from the text and use critical reasoning to evaluate its rhetorical effectiveness.

You have 50 minutes to read the passage and write an essay in response to the prompt provided below.

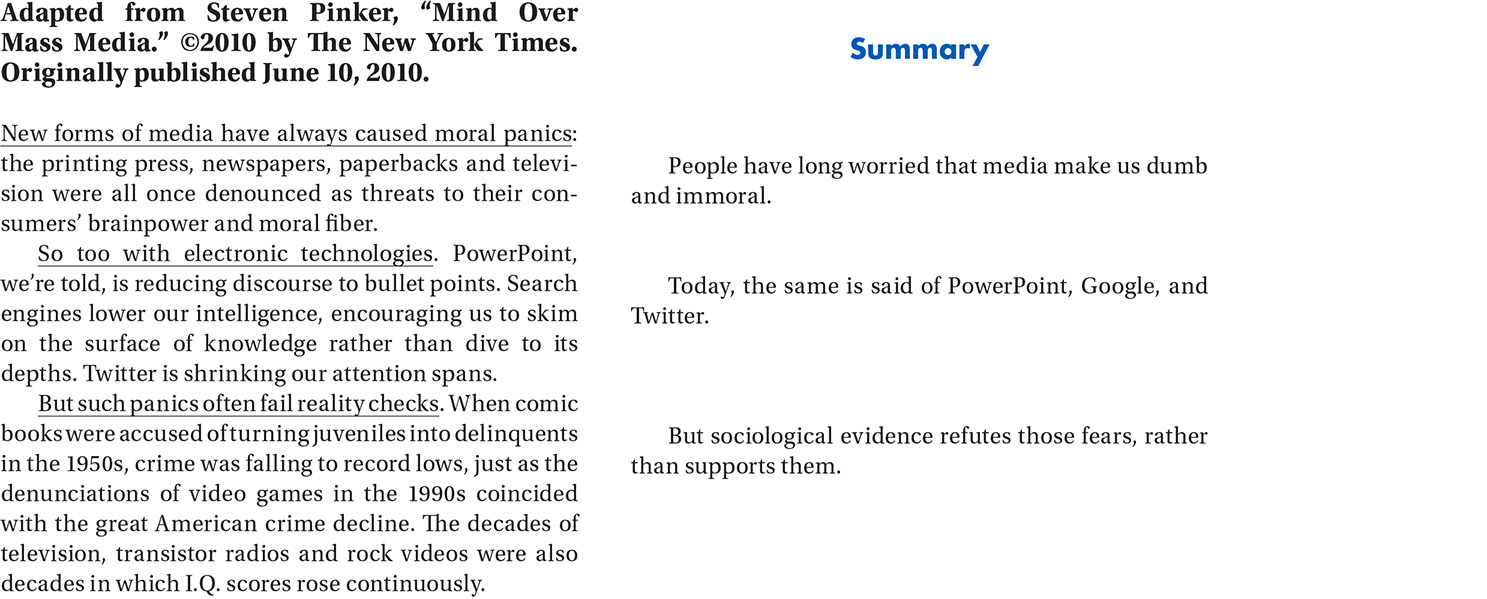

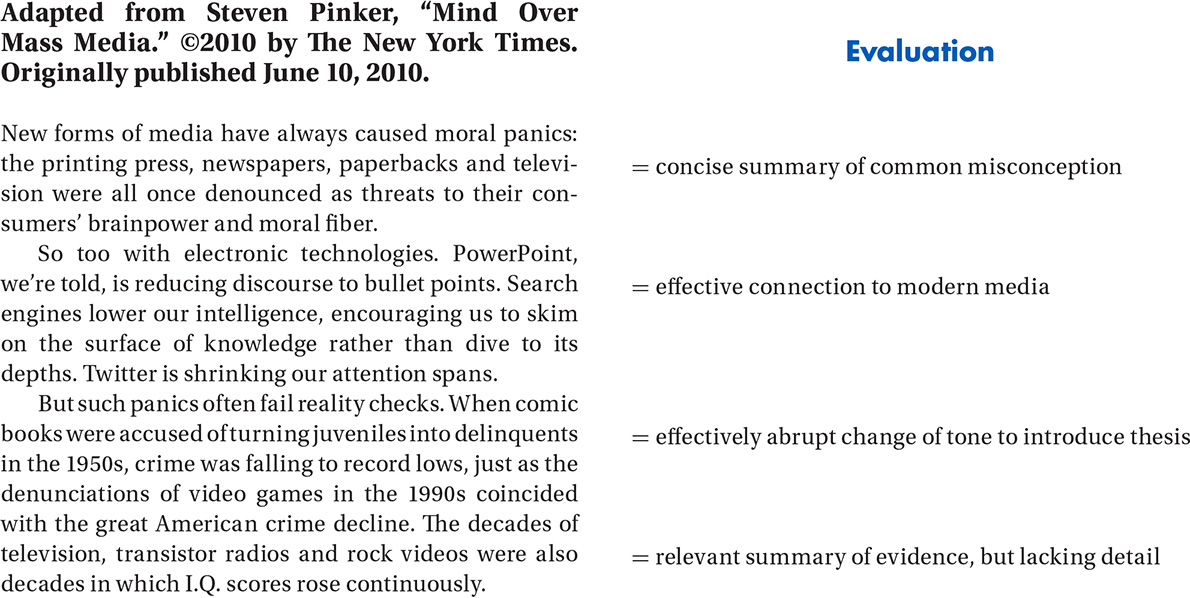

Adapted from Steven Pinker, “Mind Over Mass Media.” ©2010 by The New York Times. Originally published June 10, 2010.

New forms of media have always caused moral panics: the printing press, newspapers, paperbacks and television were all once denounced as threats to their consumers’ brainpower and moral fiber.

So too with electronic technologies. PowerPoint, we’re told, is reducing discourse to bullet points. Search engines lower our intelligence, encouraging us to skim on the surface of knowledge rather than dive to its depths. Twitter is shrinking our attention spans.

But such panics often fail reality checks. When comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s, crime was falling to record lows, just as the denunciations of video games in the 1990s coincided with the great American crime decline. The decades of television, transistor radios and rock videos were also decades in which I.Q. scores rose continuously.

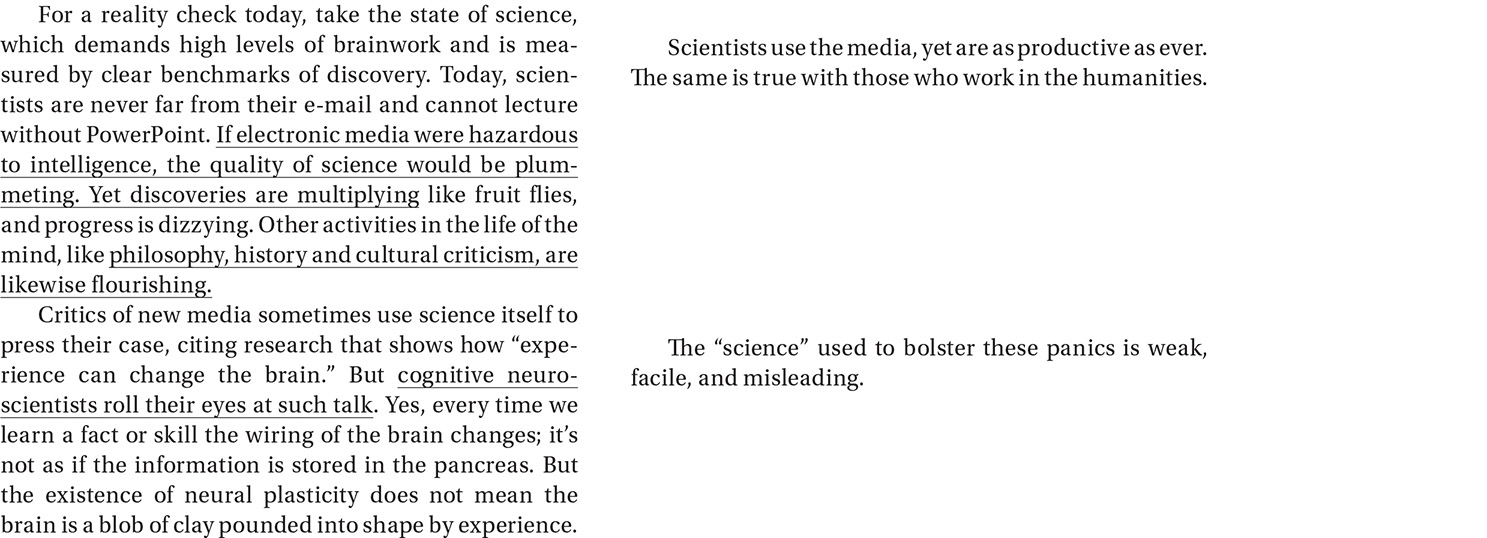

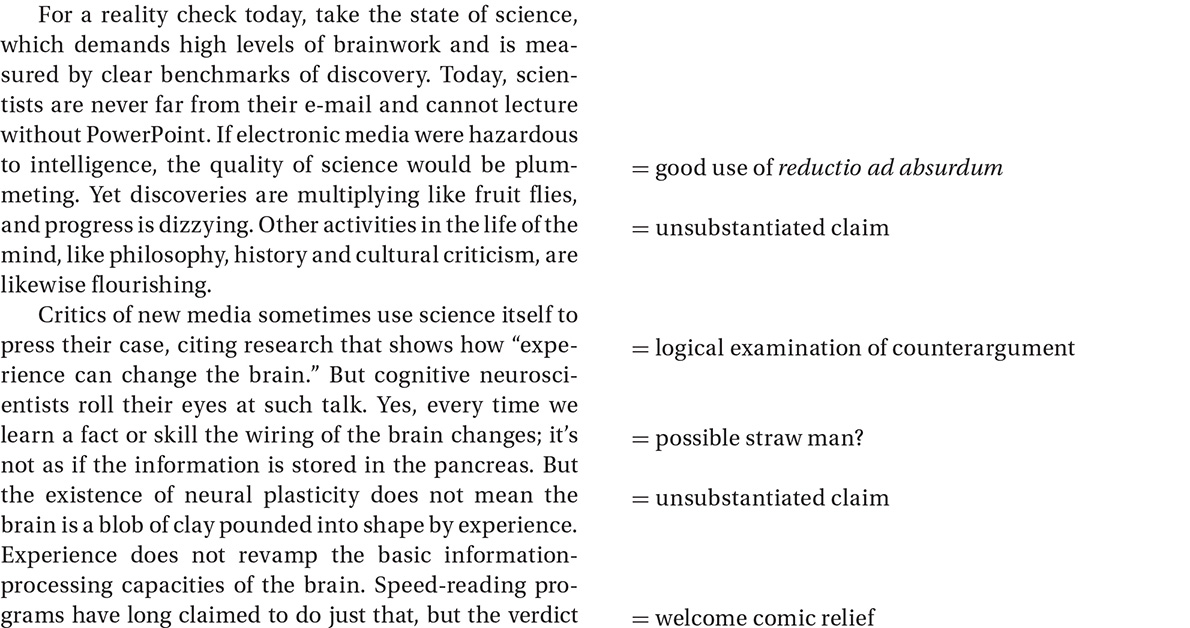

For a reality check today, take the state of science, which demands high levels of brainwork and is measured by clear benchmarks of discovery. Today, scientists are never far from their e-mail and cannot lecture without PowerPoint. If electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting. Yet discoveries are multiplying like fruit flies, and progress is dizzying. Other activities in the life of the mind, like philosophy, history and cultural criticism, are likewise flourishing.

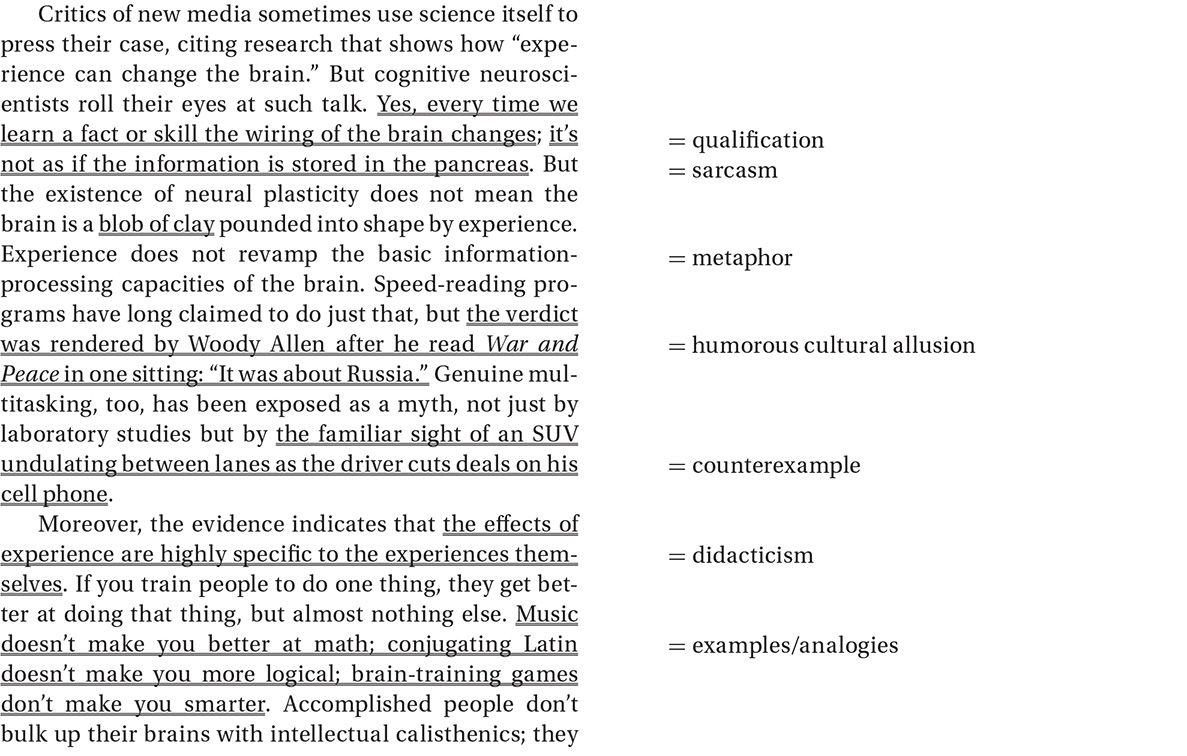

Critics of new media sometimes use science itself to press their case, citing research that shows how “experience can change the brain.” But cognitive neuroscientists roll their eyes at such talk. Yes, every time we learn a fact or skill the wiring of the brain changes; it’s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas. But the existence of neural plasticity does not mean the brain is a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience.

Experience does not revamp the basic information-processing capacities of the brain. Speed-reading programs have long claimed to do just that, but the verdict was rendered by Woody Allen after he read War and Peace in one sitting: “It was about Russia.” Genuine multitasking, too, has been exposed as a myth, not just by laboratory studies but by the familiar sight of an SUV undulating between lanes as the driver cuts deals on his cell phone.

Moreover, the evidence indicates that the effects of experience are highly specific to the experiences themselves. If you train people to do one thing, they get better at doing that thing, but almost nothing else. Music doesn’t make you better at math; conjugating Latin doesn’t make you more logical; brain-training games don’t make you smarter. Accomplished people don’t bulk up their brains with intellectual calisthenics; they immerse themselves in their fields. Novelists read lots of novels; scientists read lots of science.

The effects of consuming electronic media are also likely to be far more limited than the panic implies. Media critics write as if the brain takes on the qualities of whatever it consumes, the informational equivalent of “you are what you eat.” As with primitive peoples who believe that eating fierce animals will make them fierce, they assume that watching quick cuts in rock videos turns your mental life into quick cuts or that reading bullet points and Twitter postings turns your thoughts into bullet points and Twitter postings.

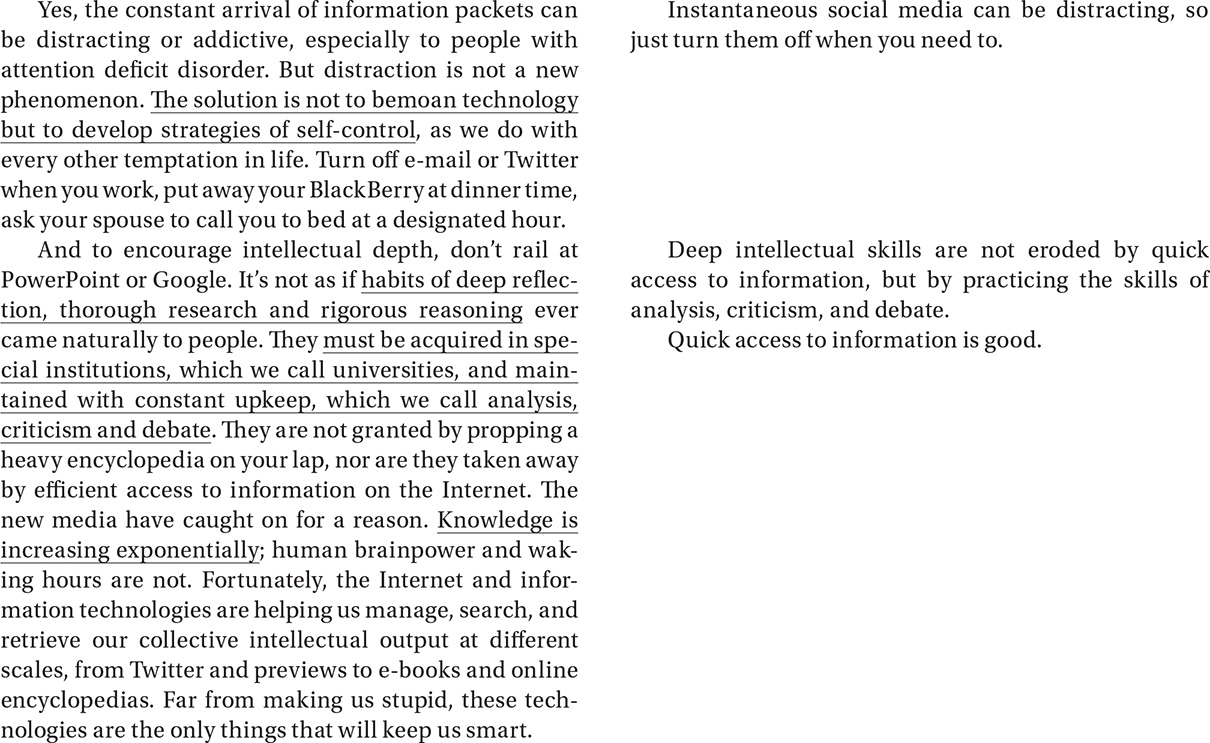

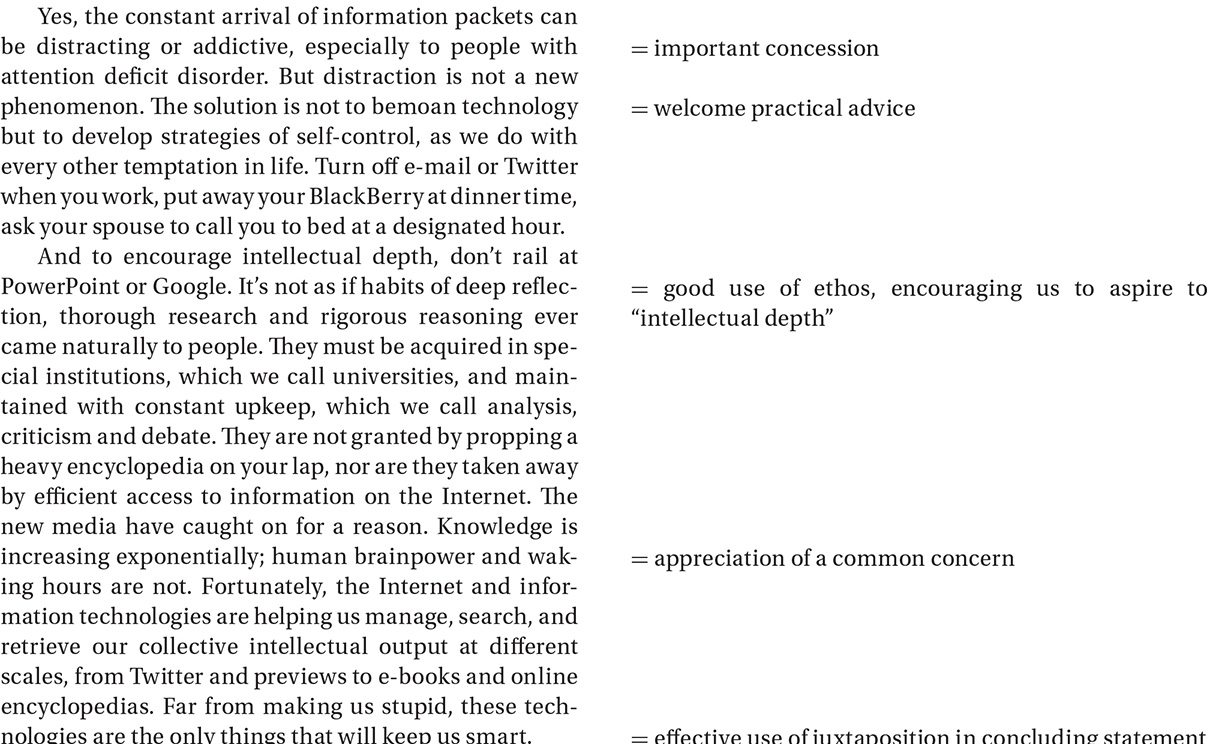

Yes, the constant arrival of information packets can be distracting or addictive, especially to people with attention deficit disorder. But distraction is not a new phenomenon. The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life. Turn off e-mail or Twitter when you work, put away your BlackBerry at dinner time, ask your spouse to call you to bed at a designated hour.

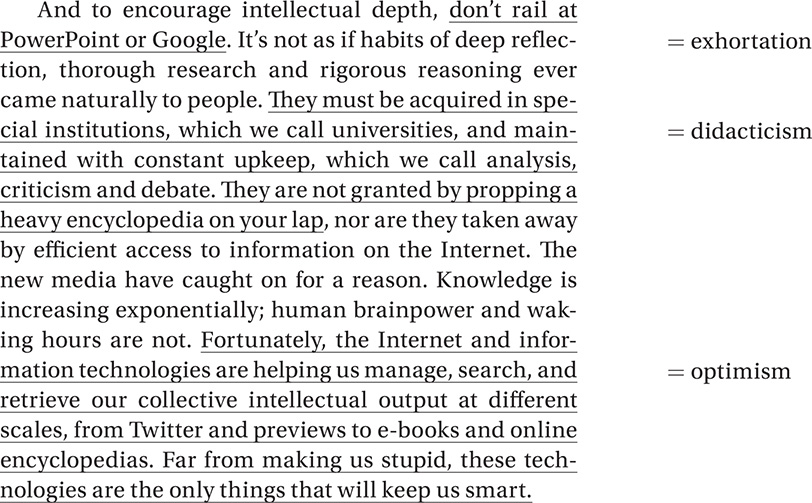

And to encourage intellectual depth, don’t rail at PowerPoint or Google. It’s not as if habits of deep reflection, thorough research and rigorous reasoning ever came naturally to people. They must be acquired in special institutions, which we call universities, and maintained with constant upkeep, which we call analysis, criticism and debate. They are not granted by propping a heavy encyclopedia on your lap, nor are they taken away by efficient access to information on the Internet.

The new media have caught on for a reason. Knowledge is increasing exponentially; human brainpower and waking hours are not. Fortunately, the Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search, and retrieve our collective intellectual output at different scales, from Twitter and previews to e-books and online encyclopedias. Far from making us stupid, these technologies are the only things that will keep us smart.

SAT Essay Scoring Rubric

Good analytical writing begins with strong analytical reading. In this first stage of the process, which should take between 15 and 20 minutes, take the “Three-Pass Approach” to analyzing the passage.

In Chapter 5, we discussed the 16 basic rhetorical and literary devices that can help you to better analyze college-level prose. Now let’s revisit them, and look at 17 more devices you should look for as you analyze argumentative essays.

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it provides a solid framework for analyzing the passage. In your second read-through, keep it simple. Just underline the sentences or phrases that use these devices, and categorize the devices in the margin.

Read the annotations in the sample analysis below and see how each underlined portion represents that particular device. Train yourself to see these devices in all of the rhetorical essays you read: newspaper op-eds, long form essays, and even your own papers.

After you’ve finished your three passes, it’s time to organize your thoughts. You need to have something interesting to write about and a coherent way to express it. This stage of the process involves constructing a thesis and outlining the entire essay.

Take your time when composing your thesis. Choose your words carefully and make sure you capture the key elements listed above. You will probably need more than one sentence to accomplish everything you need in a good thesis paragraph. Consider this first draft for our thesis:

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker looks at new forms of media. His thesis is about the reality of modern social media and the Internet. He talks about the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain.

Analyze your sentences for precision by “trimming” them as we discussed in Chapter 4, Lesson 3. Trimming reduces a sentence to its core, that is, the phrases that convey the essential ideas. When we do this with our first draft, we get “… Steven Pinker looks at new forms. … His thesis is about the reality. … He talks about the misconceptions. …” Are the verbs strong and clear? Are the objects concrete and precise? Not really. Let’s look back at our notes and use quotations from the passage to make these sentences more precise.

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker looks at examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. His thesis is about the reality of modern social media and the Internet that “such panics often fail reality checks.” He talks about effectively analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain.

Notice that this revision better specifies what Pinker is examining in his essay by more precisely articulating his thesis, even including a quotation.

Although our second draft provides more detail about Pinker’s thesis, this draft still lacks detail about his essay’s rhetorical and stylistic elements. It could be more thorough. Let’s look back at our notes and add some details about these elements.

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. His thesis, is that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, illustrative images, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims, and effectively analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain.

Note that this revision more thoroughly explains how Pinker makes his points by specifying rhetorical and stylistic devices.

An insightful essay provides a unique perspective on and evaluation of the source text. Although the SAT Essay instructions say that your response should NOT explain whether you agree with the author’s claims, the official SAT Essay scoring rubric states that a high-scoring essay must offer a thorough, well-considered evaluation of the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and/or stylistic elements, and/or features of the student’s own choosing. In other words, don’t say whether you agree with the source text, but explain how well it performs the persuasive task.

Think of it this way: a good movie or restaurant reviewer shouldn’t just say “Don’t go to that movie because I hate car chases,” or “Don’t go to that restaurant because I don’t like spicy food,” because a reader might actually like car chases or spicy food. Instead, a good reviewer describes the cinematic aspects of the movie or culinary aspects of the food to help the reader make a better decision. Similarly, your essay should give your reader enough information to decide for himself or herself whether Pinker’s essay is strong.

Our current draft is lacking some of these insights, so let’s add a few.

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. His essay provides a measure of balance to our sometimes hysterical discussions of social media and instantaneous digital information. His thesis, that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, illustrative images, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims, and effectively analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain. Although his argument could have been bolstered with more specific scientific support, his essay as a whole effectively argues for a reprieve from the hysteria about intellectual and moral decline allegedly caused by Twitter and Facebook.

Notice that this revision insightfully evaluates how effectively Pinker makes his points.

Once you’ve composed your thesis, outline the rest of your essay. Plan to write between five and seven paragraphs.

Our thesis paragraph draws the reader in by beginning to answer the question How does Steven Pinker’s Essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” establish a point of view about the effects of modern media and information technologies? by summarizing Pinker’s thesis, describing his rhetorical and stylistic techniques, and evaluating the effectiveness of his writing.

The rest of the essay should focus on supporting those points and discussing their relevance.

1. Pinker’s essay examines the “moral panics” about new media and information technologies supposedly causing cognitive and moral decline, and argues for a reprieve from the hysteria.

2. Pinker effectively uses historical examples to support his thesis.

3. Pinker uses logical analysis to refute the opposing viewpoint.

4. Pinker uses psychological research to explain how misguided our worries about new media are.

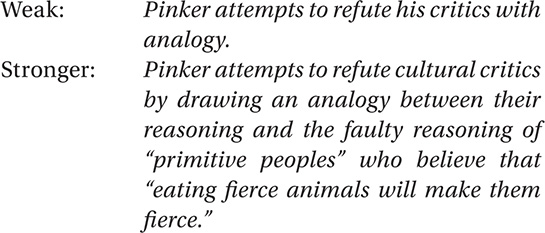

5. Pinker attempts to refute his critics with an analogy between modern critics and the thinking of ancient peoples.

6. Pinker provides constructive advice for those prone to distraction by new media.

7. Pinker concludes with a hopeful view of new media and information technologies.

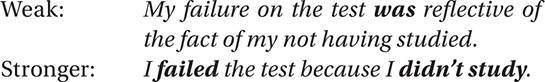

Look at a recent essay you’ve written and circle all of the verbs. Are more than one-third of your verbs to be verbs (is, are, was, were)? If so, strengthen your verbs. You cannot maintain a strong discussion if you overuse weak verbs like to be, to have, and to do.

Here are some more examples of how upgrading the lurkers can strengthen a sentence:

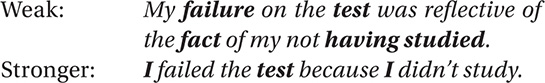

Here, we’ve upgraded the lurkers reflective (adjective) and having studied (participle). Notice that this change not only strengthens the verbs and clarifies the sentence, but also unclutters the sentence by eliminating the prepositional phrases on the test, of the fact, and of my not having studied.

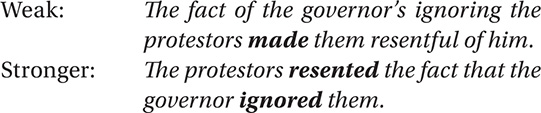

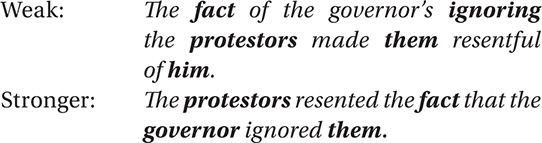

We’ve upgraded the lurkers ignoring (gerund) and resentful (adjective). Again, notice that strengthening the sentence also unclutters it of unnecessary prepositional phrases.

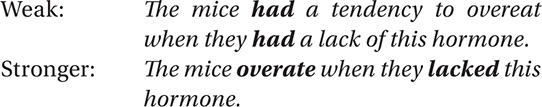

We’ve upgraded the lurkers to overeat (infinitive) and lack (noun).

The rebel army made its bold maneuver under the cloak of darkness.

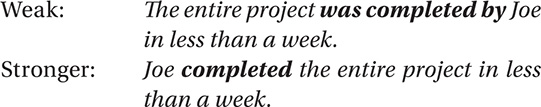

The bold maneuver was made by the rebel army under the cloak of darkness.

These two sentences say essentially the same thing, but the first sentence is in the active voice whereas the second is in the passive voice. In the active voice, the subject of the sentence is the “actor” of the verb, but in the passive voice, the subject is not the actor. (The maneuver did not make anything, so maneuver is not the actor of the verb made in the second sentence, even though it is the subject.) Notice that the second sentence is weaker for two reasons: it’s heavier (it has more words) and it’s slower (it takes more time to get to the point).

But there’s an even better reason to avoid passive voice verbs: they can make you sound deceitful. Consider this classic passive-voice sentence:

Mistakes were made.

Who made them? Thanks to the passive voice, we don’t need to say. We can avoid responsibility.

Strong writers use concrete and personal nouns, even when discussing abstract ideas. Readers identify more strongly with people and things than they do with abstractions like being and potential.

You may have noticed that strengthening our verbs in Lesson 9 also had the extra benefit of strengthening our nouns:

In the first sentence, 75% of the nouns (failure, fact, and having studied) are abstract, but in the second, the nouns and pronouns (I, test, I) are personal and concrete.

By upgrading the gerund ignoring to a verb, we reduced the number of abstract nouns in the sentence by 50%. Even better, we upgraded the subject from an abstract noun (fact) to a concrete and personal one (protestors).

Don’t merely state your ideas: explain them clearly enough so that your reader can easily follow your analysis.

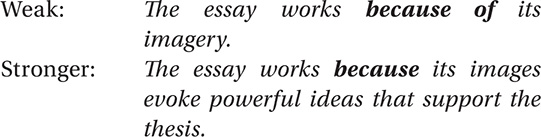

Notice that avoiding the of forces the writer to provide a clause instead of just a noun phrase and therefore give a more substantial explanation.

Consider these sentences:

Davis makes the important point that defense lawyers sometimes must represent clients whom they know are guilty, not only because these lawyers take an oath to uphold their clients’ right to an adequate defense, but also because firms cannot survive financially if they accept only the obviously innocent as clients. This troubles many who want to pursue criminal law.

What does the pronoun This in the second sentence refer to? What troubles many who want to study criminal law? Is it the fact that Davis is making this point? Is it the moral implications of lawyers representing the guilty? Is it the technical difficulty of lawyers representing the guilty? Is it the financial challenges of maintaining a viable law practice? Is it all of these? The ambiguity of this pronoun obscures the discussion and makes the reader work harder to follow it. Clarify your references so that your train of thought is easy to follow.

Davis makes the important point that defense lawyers sometimes must represent clients whom they know are guilty, not only because these lawyers take an oath to uphold their clients’ right to an adequate defense, but also because firms cannot survive financially if they accept only the obviously innocent as clients. Such moral and financial dilemmas trouble many who want to pursue criminal law.

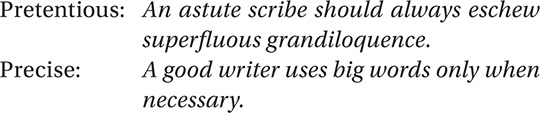

Choose precise words over pretentious ones. You won’t get extra points for using obscure words when you could use simple ones.

Consider this paragraph:

Medical interns are overworked. They are constantly asked to do a lot with very little sleep. They are chronically exhausted as a result. They can make mistakes that are dangerous and even potentially deadly.

What is so dreary about it? The sentences all have the same structure. Consider this revision:

Constantly overworked and given very little time to sleep, medical interns are chronically exhausted. These conditions can lead them to make dangerous and even deadly mistakes.

Your readers won’t appreciate your profound ideas if they are stupefied by unvarying sentences. Now consider these sentences:

Gun advocates tell us that “guns don’t kill people; people kill people.” On the surface, this statement seems obviously true. However, analysis of the assumptions and implications of this statement shows clearly that even its most ardent believers can’t possibly believe it.

Now consider this alternative:

Gun advocates tell us that “guns don’t kill people; people kill people.” On the surface, this statement seems obviously true. It’s not.

Which is better? The first provides more information, but the second provides more impact. Good writers always think about the length of their sentences. Long sentences are often necessary for articulating complex ideas, but short sentences are better for emphasizing important points. Choose wisely.

Analysis of Pinker’s “Mind Over Mass Media”

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. His essay provides a measure of balance to our sometimes hysterical discussions of social media and instantaneous digital information. His thesis, that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, illustrative images, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims and effectively analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain. Although his argument could have been bolstered with more specific scientific support, his essay as a whole effectively argues for a reprieve from the hysteria about intellectual and moral decline allegedly caused by Twitter and Facebook.

Pinker addresses common misconceptions with historical evidence: “When comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s, crime was falling to record lows, just as the denunciations of video games in the 1990s coincided with the great American crime decline.” Here, Pinker is suggesting that sociological and psychological evidence refutes claims of social decline.

Pinker effectively uses indirect proof or “reductio ad absurdum” in his third paragraph: “If electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting. Yet discoveries are multiplying like fruit flies, and progress is dizzying. Other activities in the life of the mind, like philosophy, history and cultural criticism, are likewise flourishing.” Unfortunately, Pinker does not provide substantial evidence to bolster these claims. He fails to address the common counterclaim that much of the “science” published on the Internet is flimsy, and the “cultural criticism” lazy.

Pinker then grounds his argument with reference to evidence from psychological research. To Pinker, the claim that “information can change the brain” is facile (“it’s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas”) and misleading (“the existence of neural plasticity does not mean the brain is a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience”). Rather, Pinker suggests, “the effects of experience are highly specific to the experiences themselves … Music doesn’t make you better at math; conjugating Latin doesn’t make you more logical; brain-training games don’t make you smarter.” Unfortunately, Pinker here seems to mistake assertion for argumentation. He is directly contradicting the claims of thousands of music and Latin teachers, as well as dozens of Lumosity commercials. But he is only gainsaying. Here again, we might expect some data to support his points.

Next, Pinker attempts to refute cultural critics by drawing an analogy between their reasoning and the faulty reasoning of “primitive peoples” who believe that “eating fierce animals will make them fierce.” He likens this to the thinking of modern observers who believe that “reading bullet points and Twitter postings turns your thoughts into bullet points and Twitter postings.” But of course just because one line of reasoning parallels another does not mean that both are equally incorrect. Here again, Pinker’s argument would benefit from information about the actual cognitive effects of reading Twitter feeds.

Next, Pinker provides a concession to his opponents: “Yes, the constant arrival of information packets can be distracting or addictive, especially to people with attention deficit disorder.” But here again, even in conceding a point, Pinker doesn’t quite offer the information a reader might want: How significant is this distraction or addiction, and does it have any harmful long-term effects? We don’t get this information, but we do get some welcome practical advice: “Turn off e-mail or Twitter when you work …” We get even more substantial advice in the next paragraph: to cultivate “intellectual depth” we must avail ourselves of “special institutions, which we call universities” and engage in “analysis, criticism, and debate.” But why, a reader might wonder, should we moderate our use of electronic media if it doesn’t have any real harmful effects, and indeed, as he says in his conclusion, these media “are the only things that will keep us smart?”

Finally, Pinker ends with a broader perspective and a note of hope: “the Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search, and retrieve our collective intellectual output … Far from making us stupid, these technologies are the only things that will keep us smart.” Perhaps Pinker is right, but his argument would be stronger with more substantial quantitative evidence and more direct refutation of our real concerns about how the Internet might be changing our brains.

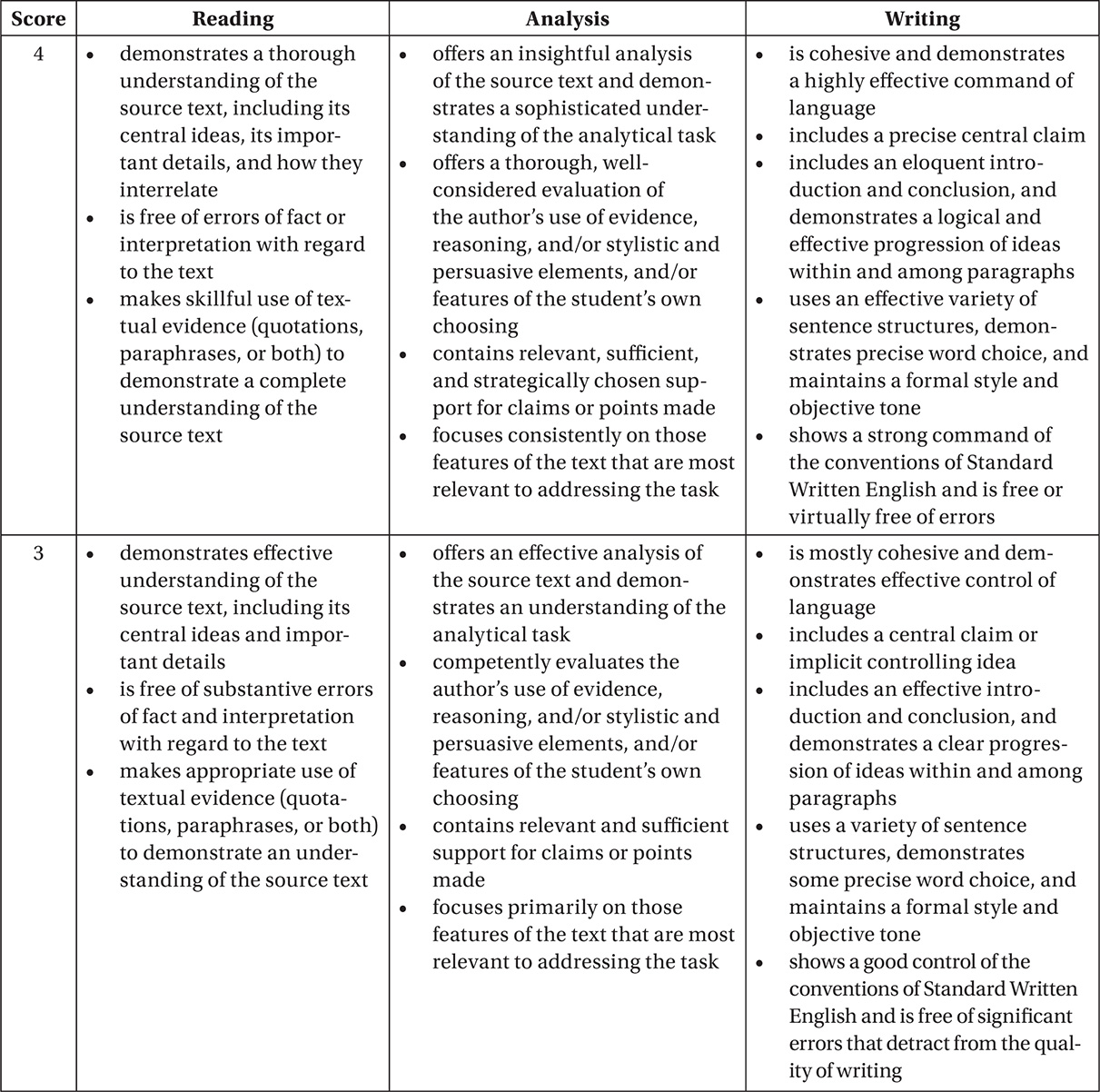

Reading—8 (both readers gave it a score of 4 out of 4)

This response demonstrates extremely thorough comprehension of Pinker’s essay through skillful use of summary, paraphrase, and direct quotations. The author summarizes Pinker’s central thesis and modes of persuasion (His thesis, that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, illustrative images, and touches of humor) and shows a clear understanding of Pinker’s supporting ideas and overall tone (He provides historical and scientific context for his claims and effectively analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain. … Pinker ends with a broader perspective and a note of hope). Each quotation is accompanied by insightful commentary that demonstrates that this author thoroughly understands Pinker’s central and secondary ideas, and even recognizes when Pinker seems occasionally to fall short of his own purpose.

Analysis—8 (both readers gave it a score of 4 out of 4)

This response provides a thoughtful and critical analysis of Pinker’s essay and demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the analytical task. The author has identified Pinker’s primary modes of expression (historical examples, logical analysis, illustrative images, and touches of humor) and has even provided a detailed examination of Pinker’s preferred logical method, reductio ad absurdum, with a discussion of several examples. Perhaps even more impressively, the author indicates where Pinker’s evidence falls short, providing critical analysis and suggesting alternatives (Unfortunately, Pinker does not provide substantial evidence to bolster these claims. He fails to address the common counterclaim that much of the “science” published on the Internet is flimsy, and the “cultural criticism” lazy. … Pinker here seems to mistake assertion for argumentation. … Here again, Pinker’s argument would benefit from information about the actual cognitive effects of reading Twitter feeds). Overall, the author’s analysis of Pinker’s essays demonstrates a thorough understanding not only of the rhetorical task that Pinker has set for himself, but also the means by which it is best accomplished.

Writing—8 (both readers gave it a score of 4 out of 4)

This response shows a masterful use of language and sentence structure to establish a clear and insightful central claim (Although his argument could have been bolstered with more specific scientific support, his essay as a whole effectively argues for a reprieve from the hysteria about intellectual and moral decline allegedly caused by Twitter and Facebook). The response maintains a consistent focus on this central claim and supports it with a well-developed and cohesive analysis of Pinker’s essay. The author demonstrates effective verb choice (effectively analyzes the misconceptions. … He likens this to the thinking of modern observers) and a strong grasp of relevant analytical terms such as reduction ad absurdum, facile, sociological and psychological evidence, counterclaim, assertion, argumentation, and gainsaying. The response is well developed, progressing from general claim to specific analysis to considered evaluation. Largely free from grammatical error, this response demonstrates strong command of language and proficiency in writing.