13

Seditious classicists

Introduction

When Thomas Hobbes published Leviathan two years after the execution of Charles I, and three decades before ‘Classics’ began to emerge as the curriculum of choice for those who wanted to distinguish themselves from the working classes, he argued that reading Greek and Roman authors should be banned by any self-respecting monarch. Hobbes had studied the Athenian democracy in depth when he translated Thucydides (1628), and now argued that ancient political writings by authors such as Aristotle and Cicero foment revolution under the slogan of liberty, instilling in people a habit ‘of favouring uproars, lawlessly controlling the actions of their sovereigns, and then controlling those controllers’.1 He would have been little surprised at the inspiring role played by classical civilisation, especially Athenian democratic and Roman republican history, in efforts to emancipate the British working class.

This chapter looks at the different ways in which diverse British radicals—republican revolutionaries, advocates of constitutional reform, agitators for universal suffrage, workplace organisers and freethinkers—used or were motivated by the ancient Greeks and Romans between the American and French revolutions and the collapse of the Chartist movement. The first group is the democrats of the 1790s; ‘democrats’ was their own term of self-description. The label ‘Jacobin’, meaning one sub-category of French revolutionaries, was used indiscriminately by British conservatives to indict anybody critical of the establishment and to erase the considerable differences between different radicals’ objectives and beliefs.2 The second group is the late Georgian reformers whose militancy began at the end of the Napoleonic Wars and most of whom were imprisoned by the increasingly Draconian measures taken after Peterloo in 1819 to control the press and limit radical activities. The third is the Chartists whose activities reached a climax with the agitation of the 1830s to 1850s.

Late 18th-century democrats: Paine, Gerrald, Thelwall

The most influential British revolutionary of the 18th century was Tom Paine—soldier, stay-maker, excise officer, engineer, writer—who was born in Britain the year that censorship was imposed on British theatres (1737). He died in New York, impoverished, the year that Abraham Lincoln was born (1809). When working as a journalist in the United States, Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense (1776), arguing for the superiority of representational government over monarchy, was instrumental in persuading colonists to fight against rule from England. His Rights of Man (1791–1792), which defended the French revolution against Edmund Burke’s criticisms, was an ‘early working-class best-seller’ and inspired all the radicals to be discussed in this chapter.3 But he was arrested in France for opposing the mass use of the death penalty, and wrote his critique of organised Christianity, The Age of Reason (published in three parts in 1794, 1795 and 1802), while detained in prison in Luxembourg. Paine has usually been held to be a kneejerk opponent of the study of antiquity, but this is incorrect.4 He wrote that the majority of non-biblical ‘ancient books are works of genius; of which kind are those ascribed to Homer, to Plato, to Aristotle, to Demosthenes, to Cicero, &c.’ In fact, the works are so important that the name of the author does not particularly matter.5 The thought of Aristotle, Socrates and Plato is indispensable, insists Paine, although saying that it is vital to remember that these men were not aristocrats: they are famous on merit.6

Paine was educated at Thetford School in Norfolk. Because his Quaker father distrusted the pagan and popish associations of the ancient languages, Tom learned neither. But he also knew that real competence in ancient Greek, at least, was acquired by far fewer members of the ruling class than liked to admit it. In a jibe at British parliamentarians’ ignorance of the balance of trade, Paine said that Charles (later Earl) Grey, who was proud of his declamatory skills honed by a classical education at Eton and Cambridge, ‘may as well talk Greek to them, as make motions about the state of the nation’.7 Paine believed that learning Latin and Greek was too time-consuming to be useful in the education of most people, since there was so much other information they needed to absorb merely to make a living and function as citizens:

After all, the valuable information to be found in ancient authors could now be read in the mother tongue:

But knowing enough about etymology to ask what a word originally meant in Greek was advantageous: when considering the word blasphemy, used to accuse freethinking critics of doctrinaire Christianity, he recommends consulting ‘any etymological dictionary of Greek’.10

Paine’s irreverence towards classical antiquity scandalised some of his contemporaries and has ever since been misunderstood by scholars who only read his most famous writings. He pokes fun at the British parliament’s hackneyed allusions, in references to the outbreak of the American war, to Julius Caesar having passed the Rubicon.11 Paine saw Classics as inherently atavistic. He thought that it prevented living generations from conceiving a better future, and thinking how it might be achieved. He was puzzled that the civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome, in comparison with all other periods of history, were so lauded and emulated. He considered that this attitude prevented his contemporaries from seeing what they had themselves achieved: ‘I have no notion’, he affirmed, ‘of yielding the palm of the United States to any Grecians or Romans that were ever born’; great progress had been made already, and in pouring praise on

He also thought that excessive respect for the ancient aesthetic sensibility was daft: for Paine, the only things more beautiful than the Wearmouth iron bridge he had designed were women.13

But he was convinced that a grasp of human history, including the markedly political history and developed secular ethics of ancient Greece and Rome, were essential to modern democrats’ understanding of the past. This enabled them to apprehend the extent of their own potential agency. In a dialogue modelled on Lucian, he resurrects the ghost of General Richard Montgomery to remind the reader of Plutarch’s heroes:

‘The Grecians and Romans were strongly possessed of the spirit of liberty but not the principle, for at the time that they were determined not to be slaves themselves, they employed their power to enslave the rest of mankind’.15 Another encounter showing the influence of both Lucian and Swift with a dead general, Alexander the Great, which Paine wrote under the pseudonym ‘Esop’, satirises the powerful as pathetic parasites on society; in Hades, Alexander exhibits ‘a most contemptible figure of the downfall of tyrant greatness’.16

Comparing ancient civilisations with the contemporary world could be beneficial in thinking through their different attitudes to war and empire:

Ancient conquerors who enjoy praise caused damage:

Like Confucius and Jesus, the Greek philosophers needed to be read, because they recommended benevolent moral systems.19

Paine never said that learning about the ancient world was anything but constructive. He thought that ancient Greeks and Romans provided useful comparands, provided that they were not held up as examples to emulate or invested with any special status or authority. They were just another set of humans, albeit very interesting ones, in another set of socio-economic circumstances. Paine was informed about ancient history and philosophy. In Rights of Man he quotes the rousing statement of Archimedes (whom, as an engineer, he much admired), saying that it can equally be applied to Reason and Liberty: if we had ‘a place to stand upon, we might raise the world’.20 He appreciated Solon’s recommendation that ‘the least injury done to the meanest individual was considered as an insult to the whole Constitution’.21 In his rhetoric against colonialism and tyranny, Paine’s love of ancient literature provides him with images: what else was the status of colonial America to its British masters than Hector, cruelly tied to ‘the chariot-wheels of Achilles’?22 He recommends that comparison with antiquity was a fundamentally useful endeavour. He suggested that any revolutionary new republic should institute ‘a society for enquiring into the ancient state of the world and the state of ancient history, so far as history is connected with systems of religion ancient and modern’.23

While Paine was in France, the London Corresponding Society, the largest radical organisation in Britain, was under attack. Joseph Gerrald, a West Indian of Irish descent, was one of two members, together with the secretary of the Society of the Friends of the People, arrested in Edinburgh in 1792 on a charge of Sedition. When Gerrald appeared in court in March 1794, he refused to answer the charges but advocated political reform, while dressed ‘in French revolutionary style, with unpowdered hair, hanging loosely behind—his neck bare’ in imitation of ancient Roman republicans.24 He was sentenced to 14 years’ transportation to Australia, where he met a tragic and premature death.25 Shortly before he was deported, he wrote to thank Gilbert Wakefield, the most radical Greek scholar of the day, for his unwavering support during the trial, quoting the ancient Greek proverb ‘ὀψὲ θεῶν ἀλέουσι μύλοι, ἀλέουσι δὲ λεπτά’, meaning that the tyrants in power may not see their punishment coming, but that it will come in time.26 In the same year, the assistant counsel for the defence, Felix Vaughan, defended Thomas Hardy, secretary of the London Corresponding Society, against the charge of treason. Twenty years earlier, Gerrald had performed the part of Oedipus in a Greek-language production at Stanmore School, ‘with an unfaltering eloquence and moving pathos that excited general admiration’.27

For Gerrald and Vaughan were both classicists, former pupils of the charismatic headmaster, Dr. Samuel Parr, dubbed ‘the Whig Dr Johnson’, during his time at Stanmore School; they had followed him there when Parr’s sympathy with John Wilkes’ campaign to get the rotten boroughs abolished and the franchise extended cost him the headmastership of Harrow.28 Parr’s sympathy for the victims of repressive policies remained unwavering, and he had danced round the ‘Tree of Liberty’ following the fall of the Bastille. For British radicals, the French revolution was initially a beacon heralding democratic reform, lower taxes, lower food prices and the humbling of an arrogant ruling class.29 But Parr, like Paine, stopped short of endorsing what he saw as ‘the cruel execution of the unhappy prince’ in France.30 He had urged caution on the wayward Gerrald (whom he had reluctantly expelled from Stanmore for some ‘extreme’ indiscretion).31 But that Gerrald remained a favourite to the end is demonstrated by Parr’s efforts on his behalf, the financial support he offered him personally (which Gerrald failed to receive),32 and finally by his commitment to the education of Gerrald’s son following his father’s death. Godwin was so affected by his friend Gerrald’s fate after having visited him in prison that he rewrote the ending of his own Oedipal novel Caleb Williams (1794), because its pessimistic ending was too close to Gerrald’s own end.33

The man responsible for popularising Godwin’s ideas about human benevolence, and the capacity of reason to remake society, was orator, elocutionist, political writer and poet, John Thelwall (see above pp. 23–4). Thelwall was himself tried and acquitted on a charge of high treason in late 1794. Like Paine, he had left school in his early teens. But Thelwall did not become a public radical until his late 20s. The son of a London silk-merchant, he was apprenticed to a tailor, but unsuccessfully, since he was a dreamy youth and constantly reading. Then he was articled to an attorney in the Inner Temple, but became radicalised when required to serve writs on desperately poor people.34 ‘Lawyers’, he later said, had ‘spread more moral devastation through the world than the Goths and Vandals, who overthrew the Roman Empire’.35 He became Literary Editor of the Biographical and Imperial Magazine and joined the London Corresponding Society. It took determined self-education (including in Latin), practising oratory at debating societies, the French revolution, a hatred for Edmund Burke and being befriended by John Horne Tooke, who stood trial alongside him, to turn Thelwall into a man perceived as a menace to the establishment.36 He was over 30 when he emerged in the mid-1790s as the chief, strategist and orator of the LCS.37

Like Gerrald, Thelwall even looked like a Roman republican. At the time of the French revolution, some rebels threw away their wigs and powder and some cropped their hair close to their heads. During the scandal surrounding the sensational trial, both supporters and enemies of the alleged traitors produced popular songs and broadsides. One poem sympathetic to Thelwall commented on his appearance: ‘Each Brutus, each Cato, were none of them fops/But all to a man wore republican crops’.38 A new tax on hair powder introduced in 1795 meant that natural hair colour meant a man was either poor or sympathetic to the poor; informers even used the unpowdered hairstyle of a friend of Thelwall called Tom Poole, a Somerset tanner, as evidence of his revolutionary views.39

The infamous trials of the early 1790s prompted, in 1795, more Draconian new legislation against sedition and treason in both written and spoken form. This forbade the airing of political complaints in front of groups of more than 50 persons. In response, Thelwall took to the Classics, which he read in translation (for this, like Keats, he was derided by his reviewers) but in depth and extensively.40 In The Rights of Nature against the Usurpations of Establishments (1796), directed against Burke, he imagines the aristocracy and its henchmen as tyrannical figures of Jupiter, brandishing thunderbolts to scare the British people, and as pouring forth toxic prose ‘crowned with Corinthian capitals’ and ‘hung with antique trophies of renown’, which must nevertheless perish: ‘They are Augean stables that must be cleansed’.41 He describes the deleterious effects of the 411 bce coup at Athens and how principled democrats and Socrates sought to maintain the spirit of liberty.42 He likens Burke’s historiography of constitutions to the fanciful notions of Polybius (then a historian held in low regard).43 He cites Dionysius of Halicarnassus, praising the original Roman Republic both for being founded by ‘throngs of emigrants and refugees’ and for choosing their governors by universal suffrage’.44 He uses Tacitus and the helots of Sparta when discussing the horrors undergone by slaves in the West Indies.45

He went on a tour to lecture on Roman History, especially ‘the abuses of monarchy and aristocracy in ancient Rome. This hoisted the banner of civic virtue once again while avoiding overt sedition’,46 although he sometimes used a direct comparison, for example between Burke and Appius Claudius, both ardent advocates of the rights of the aristocracy.47 More often, the parallel was implied: he said that it was always the infighting between men at the top of the social tree, like Augustus and Mark Antony, which inflicted war on the rest of humanity.48

The censorship of public speech was stringent: ‘Locke, Sydney, and Harrington are put to silence, and Barlow, Paine and Callendar it may be almost High Treason to consult’, let alone discuss publicly. But ‘Socrates and Plato, Tully and Demosthenes, may be eloquent in the same cause’.49 Thelwall gave about 20 such lectures, before, in 1796, editing the 17th-century Republican Walter Moyle’s Essay on the Constitution and Government of the Roman State, giving it the new and provocative title Democracy Vindicated (even though Moyle had been no democrat); Thelwall billed himself on the title page as a ‘Lecturer in Classical History’.50 His next series of lectures offered a far more radical view of the Roman Republic than had Moyle; they were idealistic and utopian in tone. The strength of the ancient Greek republics was that every single man participated in both labour and profit.51 But all known societies—the polished Athenian, the austere Spartan, the voluptuous Roman and the Germanic barbarian—have divided their people into classes, to toil and fight.52

Thelwall took these lectures round the provinces, but his opponents ensured that he was received with hostility by crowds persuaded that he was an enemy of the people. At Yarmouth, his copies of Plutarch’s Lives and Dionysius of Halicarnassus’s Roman Antiquities were seized, torn to pieces or carried off as trophies.53 He retired from politics in 1798, to re-emerge as a successful teacher of elocution later. He had saved enough money by 1818 to buy a journal, the Champion, which called (by then rather moderately) for parliamentary reform, but his political influence was effectively over before the beginning of the 19th century.

Thelwall was also a writer of poetry and prose narrative, three volumes of which were published as The Peripatetic in 1793, and more subsequently. In his later life, his radicalism was expressed on the level of sexualised poetry (his second marriage was to a teenager thirty-five years his junior) rather than of democratic agitation. Unpublished verses discovered by Judith Thompson in a manuscript of Thelwall’s poetry in Derby Local Studies Library included not only steamy imitations of love poetry by Ovid, Anacreon and Catullus, but ‘A Subject for Euripides’ (‘a transparently-oedipal, blank-verse gothic narrative about an older woman who miraculously keeps her youthful looks long past her prime’),54 and ‘Sappho’, in which Thelwall deploys the female poet as a cross-dressed avatar of his younger self.55

Before and after Peterloo: Carlile, Hibbert, Wedderburn

After 1797 there was little discussion of parliamentary reform in the House of Commons, nor open public disorder, for more than a decade. It was in 1816, when the end of the Napoleonic Wars coincided with anti-government riots about food prices in Ely and Littleport, and at Spa Fields, Islington, that class conflict rose to the top of the national agenda. William Cobbett reported that numbers attending mass reform meetings multiplied at this time from 500 to 30,000.56 March of the following year saw Richard Carlile, ‘one of the most important British working-class reformers of the nineteenth century’,57 give up his attempt to earn a precarious living as a journeyman tin-plater and begin his journalistic career. His first articles were written under the pseudonym ‘Plebeian’ for Sherwin’s Weekly Political Register.

Carlile was born in Devon in 1790 to a father who worked as a shoemaker and a soldier, and a mother who kept a small shop. He acquired a rudimentary education at a charity free school until he was 12, but in his early teens, when working for a local chemist, he read classical literature in translation and Paine’s writings; he also taught himself Latin.58 He switched to tin-plating, which he thought would be more remunerative, but at 21 and desperate for work, he moved with his young wife to London, where they lived in dire poverty. There were four reasons why he turned into a full-time radical in 1817: (1) the suppression of rebellious stockingers and day labourers in Derbyshire; (2) the politically motivated trials (and popular acquittals) of Thomas J. Wooler and the Spencean Dr. James Watson; (3) Carlile’s reading of Constantin Volney’s Les Ruines ou Méditations sur les Révolutions des Empires (1791), available in English since 1792 (and which also profoundly affected Shelley, especially in Queen Mab);59 and (4), the examples of Robert Owen, Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, Cobbett’s Political Register and Robert Wedderburn, whom we shall meet again later in this section.60

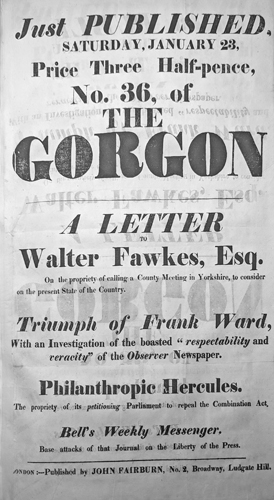

After four months’ imprisonment in 1817, Carlile ran a bookshop crammed with political and deist pamphlets and tried one revolutionary newspaper, The Gracchus. It was followed by The Gorgon, which was briefly an important organ of early trade unionism, the title chosen with an ironic reference to the way that the conservative press had often disparaged radicals by comparing them with the snake-haired villainess of mythology.61 This newspaper advertised meetings of ‘The Philanthropic Hercules’, the loose federation of workers’ unions formed in 1818 (see further pp. 446 and 467).62 (Figure 13.1) On May 30th 1818, it ran an article on the abuse of charitable bequests which were supposed to fund schools, but were commandeered as personal profit by parish clergy and municipal corporations. In much of England ‘there are erected what are termed Free Grammar Schools, for the instruction of poor children in Latin and Greek, gratis’. These were set up for praiseworthy motives. But they are neglected, teach few, and

But Carlile himself knew the power of displaying a command of Latin, conducting an extensive discussion, including a five-line quotation in Latin, of Horace’s Satires I, when defending Cobbett against criticisms.64

Carlile most outraged the authorities by illegally republishing works by Paine,65 but he was at his most creative with classical material in The Medusa, the successor to The Gorgon, just before and after Peterloo in 1819. On 24th July, The Medusa prints a comparison of constitutional models dependent on Aristotle’s Politics, which introduces the Resolutions passed at the meeting of the Radical Friends of Reform at Smithfield on 21st July. Then a parodic poem on 31st July teems with classical references. But on 16th August 1819, mounted yeomanry charged into a crowd of tens of thousands at St. Peter’s Field, Manchester, who had amassed to hear Henry Hunt and other radicals address them. Eighteen people died of sabre wounds or trampling and crushing injuries. Carlile was present. His first response in The Medusa, on 21st August, is a pseudo-Lucianic ‘Dialogue in the Shades’ between Paine and Pitt. But the idea of the classical underworld suggested a more adventurous trope. In order to report on the aftermath of the Peterloo ‘murders’, he uses the form of imaginary letters sent to Medusa by her sister Gorgons, using their authentic names Euryale and Stheno. They have access to both the murdered in the underworld and the courts where the events of that day were being processed judicially. The first letter, from Euryale to Medusa, was printed in the issue of 15th September:

On 26th September (279), the third Gorgon sister, Stheno, writes ‘from the Styx’ to Medusa as well: ‘As soon as the late inhuman massacre became known to us here, we held a conclave for the purpose of advising those oppressed slaves in Britain’. She is outraged that the murderers are not to be prosecuted. Lamia (a notoriously bloodthirsty monster) has been advising that they should be assassinated. Stheno has dissuaded Lamia, but recommends instead, ‘Let them meet, let them unite, let them ARM, and demand redress and justice, and a restitution of those rights which have been so long unjustly withheld from them’. Stheno’s rallying cry is a response to the exoneration by the Prince Regent of the magistrates involved. He had thanked them via the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth. Robert Wedderburn had openly called for the abolition of the monarchy,66 and Carlile wrote (in his own voice, not a Gorgon’s), ‘Unless the Prince calls his ministers to account and relieved his people, he would surely be deposed and make them all REPUBLICANS, despite all adherence to ancient and established institutions’.67 There was a genuine danger of armed unrest, with rebellions in West Yorkshire and Lancashire in the autumn of 1819.

On 13th October (279–80), Euryale writes again to Medusa. She attended the Coroner’s Inquest and was appalled at the peremptory treatment of the murders, before hastening to the Prince’s bizarre palace at Brighton, the scene of debauchery. She describes the sleeping Prince, with his ‘bloated features’, in insulting terms. She encountered hanging over him the shade of Brutus, ‘the illustrious patriot of the Ancients’, who in a ‘prophetic frenzy’ recited a malediction, praying that the Prince die a terrifying death. A week later, Stheno, from the Styx, protests against the current crackdown on freethinking of any kind (18th October, 294). Confused by establishment figures calling the violence of Peterloo dictated by ‘the Word of God’, she had sent to the upper world for a copy, but the message went to the wrong country, and the Koran arrived instead of the Christian Bible. When she did get the ‘Word of God’ as read in England, she found it so full of ‘murders, incests, &c.’ that she was shocked. On 13th November (310–11) Euryale writes to Medusa of her concern that the British reformers are splitting into factions; she reiterates that armed force may be necessary (she cites the examples of the two Roman Brutuses and Wat Tyler). She concludes by saying that she hopes to be able to update her sister on the ‘Mission of Brutus’ shortly.

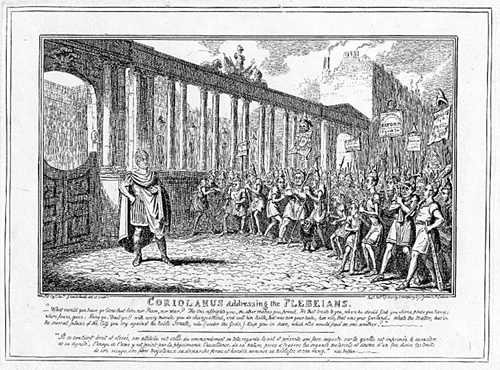

This confrontation between George IV (he became King in January 1820) and newspapers like The Medusa was ridiculed by caricature artist George Cruikshank in ‘Coriolanus Addressing the Plebeians’ (29th February 1820) (Figure 13.2). Cruikshank likens it to the face-off between the legendary early Roman statesman Caius Marcius Coriolanus, known to his readers from Plutarch via Shakespeare, and the plebeian class at Rome. Three of the Cato Street conspirators, who in February 1820 had planned to kill the Prime Minister and his cabinet, are arranged under the banner ‘Blood and Thunder’: Thomas Preston, Dr. James Watson and Arthur Thistlewood. Beside them are Carlile and Cobbett, who is holding Tom Paine’s bones. Among the more moderate reformers lining up are the satirist William Hone and the creator of the caricature, Cruikshank himself. They sport the red cap of the Roman freedman.

Carlile’s Gorgons fulfil several subversive functions. By appropriating the Classics-laden rhetoric of the ruling class, he draws attention to cultural apartheid while undermining it. As a critic of Christianity, the mythical personae allow him to sidestep the pious bombast which the government was using against the radicals. By using the speech-within-a-speech form (Brutus quoted by Euryale) for expressing the desire for the Regent to die a horrible death, Carlile might have thought he could have defended himself personally against a charge of sedition. As immortals, the Gorgon sisters not only have long memories of the history of revolts against tyrants, but Stheno, at least, can move instantaneously between places to witness an inquest in Manchester and the (heavily guarded) bedchamber of the Regent. But the letters are also funny, and Carlile knew as well as anyone that collective laughter in the face of oppression can be politically effective.

Unsurprisingly, by the time the November issues came out, Carlile had already been convicted of blasphemy and seditious libel in one of the 75 prosecutions for those crimes brought in England in 1819 alone.68 He was fined and incarcerated in Dorchester until 1825. He continued publishing the Republican from prison, but the Medusa ceased. The Prince Regent, who had once asked of a man, ‘Is he a gentleman? Has he any Greek?’69 was not assassinated, and the moment of greatest threat to the established order passed. After the Cato Street conspirators were hanged and beheaded or deported, new repressive legislation (‘The Six Acts’) meant that all British radicals found themselves in gaol. Carlile’s wife Mary-Anne loyally moved into Dorset Prison with him, and in 1823 they had a daughter whom they named Hypatia after the ancient pagan intellectual. She died in infancy.70

The imprisoned Carlile acquired a large ‘republican and infidel’ following. His keenest supporters, in London, Salford, Stalybridge and Glasgow, founded ‘zetetic’ societies (from the ancient Greek verb zētein, to seek out or enquire after), which investigated the truth of existence by scientific and non-Christian methods.71 The emphasis of his work fell increasingly on free thought once he began collaborating ‘as Infidel missionary’ with the Reverend Robert Taylor, an anti-clerical mystic who had been imprisoned for blasphemy after lecturing in London pubs on the immorality of the Church of England. Carlile promoted Taylor’s published works, written in prison,72 notably his Syntagma (1828) and Diegesis (1829). These argued that all religions were similar, based on solar and astral myths and sacrificed heroes, and that honorific titles such as ‘Christ’ and ‘Lord’ were merely the equivalents of epithets applied to Bacchus, Apollo, Adonis and Jupiter.73

In 1830, Carlile founded the Rotunda in Blackfriars Road, to nurture revolutionary sentiment against the ‘aristocratical or clerical despotism, corruption and ignorance of the whole country’.74 It became the recognised centre of London working-class radicalism, featuring spectacular ‘infidel’ dramas, in which Taylor showed that the gospels rewrote primordial Mithraic and Bacchic mysteries.75 Carlile and Taylor were re-imprisoned, but the work at the Rotunda was continued by their Bolton-born disciple and sex equality activist, Eliza Sharples, who became Carlile’s common-law wife. She led the mysteries in the persona of Isis, dressed in flowing gowns, with white thorn and laurel leaves underfoot.76

Carlile’s intellectual mentor, on the other hand, was Julian Hibbert, whose death in 1834 shattered him. Hibbert was one of the most mysterious radicals on the post-Peterloo scenes, not least because, although highly educated and privately wealthy, he was tightly embedded within the working-class political community from which Carlile became distanced as his theological interests deepened.77 In 1828 Hibbert published an edition of Plutarch’s On Superstition, with other material including Theophrastus’ character portrait of the ‘Superstitious Man’, which was adopted and much used by less erudite freethinkers. Hibbert humorously states that he regards ‘no book so amusing as the Old Testament’ and closes his preface ‘by consigning all “Greek Scholars” to the special care of Beelzebub’.78 He attaches dazzlingly erudite polemics on how religion is used to sedate what Burke called ‘the swinish multitude’, on all the individuals falsely accused of impiety from Xenophanes, Socrates and Aristotle via Julian the Apostate to the 19th century, and the many definitions of the word ‘god’.79 But Hibbert was active in radical politics as well. He was treasurer to the Victim Fund run by the agitators for the freedom of the unstamped press; the Chartist William Lovett recalled:

Hibbert personally funded several of the legal defences of the radicals imprisoned after Peterloo, and had almost certainly furnished the arguments from Plutarch used by Robert Wedderburn, the mixed-race son of a Scottish planter in Jamaica by his African slave woman, when tried for blasphemy in May 1820.81 (Figure 13.3)

A Unitarian preacher, and follower of Thomas Spence, Wedderburn had described Jesus Christ as a ‘republican’ and ‘reformer’ and compared him with Henry Hunt. Hunt was himself at the time in prison following Peterloo. A transcript of Wedderburn’s trial including his speech, with learned notes, was simultaneously published. It is an uncompromising defence of freedom in discussion of scripture: ‘Tyrannical and intolerant laws may exist and be enforced in times of darkness and ignorance, but they will be of little effect when once the human mind is emancipated from the trammels of superstition’.82

The publication was edited by George Cannon, under the pseudonym Erasmus Perkins: a middle-class, educated radical, Cannon later became a notorious pornographer. With advice from Hibbert, he almost certainly wrote some of Wedderburn’s plea—Wedderburn says that he had been unable to write it because his work as a tailor had wrecked his eyesight, and a court clerk read it out. Footnotes enhance the publication’s air of erudition and authority. Amongst quotations from the Christian Fathers, and references to Roman myth, there is a discussion of the derivation of the two ancient Greek roots of the Greek word blaspheme (which Paine had also discussed; see above, p. 273), and a long note on the Delphic oracle. Plutarch is cited for arguing that it is better to deny the existence of a Supreme Being than to ‘entertain degrading and dishonourable notions of him’.83 Wedderburn’s court appearance persuaded the jury to recommend ‘mercy’, resulting in a sentence of ‘only’ two years in Dorchester gaol.

Chartists: O’Brien, Jones, Cooper

Four years before Hibbert’s untimely death, a fiery young Irishman named James ‘Bronterre’ O’Brien arrived in London. He was to play a key role in the first national working-class movement of Chartism. He was not only one of the greatest Chartist speakers, but perhaps the one most trusted by working people. The People’s Charter demanded universal male suffrage, secret ballots, annual parliaments, pay for MPs and abolition of property qualifications to stand for election and equal electoral districts.84 Bronterre, as he was known, probably on account of his thunderous oratory, was a middle-class man from County Longford. He had passed the TCD Classics exams with flying colours and, as an undergraduate, won prizes in both Classics and science.85 Although he went to London to further his studies of law, he was already radicalised, becoming the editor of The Poor Man’s Guardian in 1832 and campaigning for a free press.86 In 1840 he was convicted of making a seditious speech in Manchester and spent 18 months in Lancaster Prison.

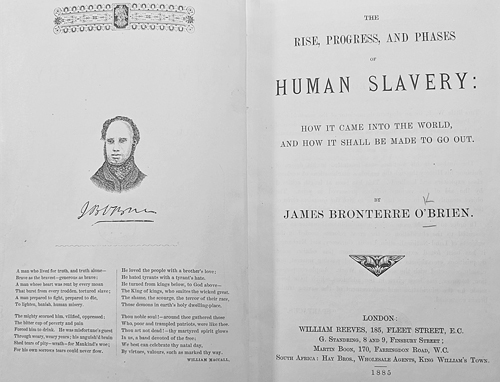

It was not until 1849 that he began publishing the 21 journal articles that became The Rise, Progress and Phases of Human Slavery,87 an unjustifiably neglected book in which he brings his expert knowledge of Classics to bear on contemporary politics and economics (Figure 13.4). He argues that ancient slavery was in some circumstances ways less bad, because ‘direct and avowed’, than the condition of the Victorian working class, ‘hypocritically masked under legal forms’, which he defines as unjust agrarian, monetary and fiscal laws.88 O’Brien’s work remains important if only because Karl Marx, who arrived in London in 1849, told Engels he was ‘an irrepressible Chartist at any price’;89 Marx’s own theories were certainly influenced by O’Brien’s theorisation of exchange in relation to the equivalence of ancient slaves and the 19th-century proletariat, the value of labour, the concept of hidden bondage, and the workings of ideology which maintain class divisions.90

Bronterre’s commitment to the working class never lessened. Even after the waning of Chartism, he opened the Eclectic Institute in Denmark Street, Soho, London, which served a useful purpose in the early stages of the Adult Education Movement, earning him the soubriquet ‘Schoolmaster O’Brien’ on account of his services to the self-education of working men.91 An unrepentant admirer of the French revolution, in 1857 he acknowledged his own frustration in his Miltonic ‘An elegy on the death of Robespierre’, in which a group of workmen, after the parliamentary revolt of 9th Thermidor 1794, address the shade of Robespierre on how other ‘godlike benefactors of our race’ have been spurned and die miserably: Aristides, Socrates, and numerous Roman republicans.92

The other classicist Chartist well known to Marx was Ernest Jones, whom Engels regarded as the only educated Englishman in politics ‘entirely on our side’.93 Born in Berlin in 1819, the son of an army major and the daughter of a major Kent landowner, Jones received his excellent classical education at a prestigious school in Hannover and moved to London at 19. He came into a fortune through his marriage; it was going bankrupt in 1844 and his own precipitation into poverty that turned him into a passionate Chartist. His first collection of poetry, Chartist Songs, published in 1846, was popular amongst the working class.94 He was arrested for seditious behaviour and unlawful assembly, enduring two years’ imprisonment; in 1850 he said to a crowd in Manchester, ‘I went into your prison a Chartist, but … have come out of it a Republican’.95 After his release, Jones assisted on George Harney’s socialist newspaper Red Republican. His long poem The New World, discussed below pp. 407, puts his classicist’s grasp of ancient history to extended use. But his lectures often used arresting classical images, too: ‘Everyone knows that Capital … is the offspring of Labour, and yet that Labour is the servant of Capital; nay! that the latter, reversing the legend of old Saturn, has been destroying its Creator’.96 When arguing against private education, he stated that

Chartists from poorer backgrounds, aware of earlier radical uses of the ancient world, enjoyed rousing quotations from antiquity. When William Lovett and James Watson drew up their Declaration of the National Union of the Working Classes in 1831, one of the epigraphs was ‘That Commonwealth is best ordered when the citizens are neither too rich nor too poor—THALES’.98 Chartists often struggled to teach themselves the classical languages. Joseph Barker, born in Bramley, Leeds in 1806, was the son of a handloom weaver and at the age of 9 forced to go to work himself. But he would prop up books by his jenny gallows to read while he worked as a spinner, and at 16 started teaching himself Latin and Greek. He became a Chartist activist later.99 Gilbert Collins was a Chartist bank clerk who taught himself Greek but could not afford the books from which to learn Arabic. The famous Chartist poet Thomas Cooper recalls that during the years 1836–1838, when he was working as a journalist in Lincoln, the two became friends partly because they ‘had an equally strong attachment to the study of languages. Collins had learned Latin at school, and had taught himself Greek, and had translated for himself the entire Iliad and Odyssey. Of the Greek Testament, he had a more perfect knowledge than any one I ever knew’.100 The pair decided to teach themselves Arabic. Another local friend, George Boole (a shoemaker’s son who had learned Latin from a kindly local bookseller and went on to become the first Professor of Mathematics at Queen’s College, Cork, later University College Cork) discovered their plan. He laughed at them, pointing out that they would need to acquire Richardson’s Arabic dictionary,101 which was quite out of their reach, costing at least 12 to 15 pounds.102 Mortified, the pair ‘felt ashamed of our thoughtlessness, and laid the project aside’.103

But Latin and Greek were more accessible through cheap second-hand textbooks. Although, as we shall see in Chapter 20, he had little formal education, Thomas Cooper, the self-styled Chartist Rhymer, had taught himself almost as much Classics as O’Brien or Jones. This is most apparent from his epic poem The Purgatory of Suicides, written in the early 1840s in Stafford Gaol, where he was imprisoned as a Chartist after being convicted of sedition.104 The Purgatory of Suicides impressed not only its Chartist readership but Carlyle, Benjamin Disraeli and Kingsley.105 The first six stanzas of The Purgatory of Suicides are, he says, a poetical embodiment of a speech he delivered in 1842 to the colliers on strike in the Staffordshire Potteries, as a result of which he was arrested for arson and violence.106

In book I, he is imprisoned and dreams of a voyage of death and meeting the souls of suicides; there is a sort of constitutional debate which draws on Herodotus Book III and Cicero’s Dream of Scipio. Some of the ancient dead involved share characteristics with Chartists. They include Oedipus (who solved the riddle), the patriotic Athenian heroes Aegeus, Salaminian Ajax, Codrus, and the tragic national heroines Dido, Cleopatra, and Boadicea; others are less admirable (Nero and Appius).107 In book IV, there is a dialogue between Sappho and Lucretius and an assembly of suicidal poets summoned by Lucan. Vicinus thinks that Cooper was indulging in shameless self-promotion by displaying his classical knowledge,108 while Sanders suggests that the poem can ‘be read as an attempt to democratize “elite” knowledge … The fact that Cooper provides explanatory footnotes for a number of his protagonists increases the education value of the poem’.109 But they overlook Cooper’s creative dialogue between ancient India and Greece. The voice of India, in the mouth of the sage Calanus, transcends time and space, in a manner reminiscent of the choruses of Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound and Hellas, to prophesy global liberation and universal suffrage.

Calanus is found in several ancient sources for Alexander the Great’s activities in India, including Plutarch’s Life of Alexander and Arrian’s Anabasis 7.1.5–3.6. He was frequently praised by ancient philosophers and Christians including Ambrose for his self-control and bravery in the face of self-death.110 In an essay entitled ‘Every Good Man is Free’, the Alexandrian Jewish scholar Philo (c. 20 bce to 50 ce) had cited Calanus as an outstanding example of the true freedom enjoyed by every good man. Philo records that when Alexander tried to coerce him into leaving India and travelling with him, Calanus pointed that he would become a useless specimen of ‘barbarian wisdom’ for the Macedonian to display to the Greek world if he allowed himself to be forced to do anything against his will (Philo, 9.14.92–6). Cooper puts the idea of Calanus as a spokesman for true spiritual freedom to innovative political use.

Calanus is introduced in book II in order to provide a climax for a list of various Greek sages. Calanus tells the Greeks Empedocles and Cleombrotus of his utopian vision of the future—a spiritual allegory for the Chartists’ vision of a levelled and democratic society:

He says that the strong will end up seeking to break bread for weeping orphans, and

That an ancient Indian sage should be selected to lecture ancient Greeks on the topics of feeding the destitute as well as enfranchising and educating the wide world’s ‘helots’ reveals Cooper’s intuition that British commercial interests in India were linked to the predicament of the working classes internationally. Cooper—an outstanding working-class intellectual—has read his ancient Greek sources on Alexander and Calanus significantly ‘against the grain’.

The lowliness of Cooper’s origins makes remarkable the detail of his knowledge of ancient history, as well as the topical appropriation to which he subjects that knowledge. Cooper was not only committed to universal male suffrage and agitation on behalf of the poor, but on an international level he was opposed to imperialism: one of his most inflammatory speeches, delivered at Hanley in the Potteries in August 1842, begins with a catalogue of ‘conquerors, from Sesostris to Alexander, from Caesar to Napoleon, who had become famous in history for shedding the blood of millions’. He described ‘how the conquerors of America had nearly exterminated the native races’. He excoriated ‘British wrongdoing in Ireland’.113 For the working-class activist Cooper, then, the ancient Brahmins of India, as filtered through ancient historiography and biography, represented a mystical fount of ancient knowledge of the post-imperial international utopia to be ushered in by the Charter. Cooper made Calanus, an ancient Indian, lecture an ancient Greek/Macedonian conqueror on social justice. Cooper had, of course, never been anywhere near India, however clear his understanding of the link between the class system in Britain and the oppression of indigenous peoples in her colonies.114

Cooper also lectured to working-class audiences at the City Chartist Hall in London, in which he popularised ‘the magnificent themes of the Athenian democracy’, and in late 1848 he spoke on the transition from ‘legendary’ to ‘historical’ Greece at the Hall of Science in City Road.115 He uses ancient sources and is also familiar with the first volume of George Grote’s History of Greece, which appeared in 1846. He was not the only Chartist routinely to use Athens and Rome as comparands on the lecture circuit. John Collins defended the Greek and Roman republics at a meeting of the Leeds Reform Association, because it was advocating household suffrage rather than universal male suffrage and the rest of the Charter’s demands.116 In Wales, Henry Vincent drew a dark picture of the invariable fall of proud empires which oppressed their poor, such as Rome, and his Monmouthshire audiences applauded loudly when he described the final victory of the northern barbarians who dashed ‘the haughty usurper’ down. Athens provided an even better example, because he could speak at length on her achievements, and St. Paul’s visit, as well as describing how she became ‘degraded’ when she lost her love of liberty.117

Conclusion

The democrats of the 1790s, especially Tom Paine and John Thelwall, were immersed in and inspired by ancient philosophy and history read in translation. The radicals around the time of Peterloo, for whom free thought on religion was inseparable from agitation for social, political and economic reform, used Classics in diverse and creative ways to enliven their journalism, inform arguments at the trials, and explore religious questions that took them far beyond the limits of orthodox Anglican theology. Three of the most important Chartist intellectuals—Ernest Jones, Bronterre O’Brien and Thomas Cooper—were expert classicists, whether trained at distinguished educational institutions or self-taught, and whether this took expression in oratory, poetry or analysis of ancient slavery.

It took decades for the Chartists’ demands to be met. Some urban working-class men were enfranchised by the Representation of the People Act 1867, but it was not until 1918 that universal male suffrage was finally achieved. With some exceptions, when working-class activism took off again in earnest in the last quarter of the 19th century, classical education was beginning to lose some of its social prestige, and most of the leaders of the labour movement were less concerned than the Georgian democrats and Chartists had been to acquire ancient languages or recruit the ancient Greeks and Romans to their cause. For some of those fascinating exceptions, see Chapter 23.