23

Socialist and communist scholars

Introduction

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, working-class activism changed in nature and increased in scale along with the rise of the Labour Movement, institutionalised workers’ and women’s education, the professionalisation of politics and the impact of the 1905 and 1917 Russian revolutions. Two contributory factors in the gradual opening of the academic profession to women, and to men who would previously have been excluded, were the opening of new universities, and the abolition in the 19th century of requirements that fellows of Oxbridge colleges should be ordained and members of the Anglican Church. This chapter excavates the classical interests of three groups committed to the cause of the working class, most of whom we have discussed at greater length elsewhere:1 the women amongst the socialists and labour organisers of the late 19th century who founded the Independent Labour Party, the classical scholars active in the first decades of the Communist Party of Great Britain and two classically trained communists, Christopher Caudwell and Jack Lindsay, who used the medium of scholarship to further the working class’ cause in the 1930s and (in Lindsay’s case) beyond.

Early labour classicists

Three intellectual streams converged in the late Victorian labour and socialist movements, two of which were indigenous and the third (Marxism) to an extent developed in London, where Marx and Engels worked from 1849. The oldest was the Utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, which emphasised the creation of conditions in which a maximum number of citizens could flourish. Blended with the anti-metaphysical, empirical historical methods developed in France by Auguste Comte, this produced the socialist Positivism of, for example, Edward Spencer Beesley (1831–1915). A classical graduate of Wadham College, Oxford, Beesley was appointed Professor of Latin at University Hall (an organisation attached to UCL) and Bedford College for Women. It was almost certainly at Beesley’s suggestion that the African American campaigner for the abolition of slavery in the USA, Sarah Parker Remond (Figure 23.1), studied Latin at Bedford in the early 1860s.2 Beesley was also a friend of Karl Marx. But he did not adopt dialectical materialism, his book Catiline, Clodius, and Tiberius (1878) being a paradigm of Positivist thought. He chaired the First International (1864), which had led to the formation of the International Working Men’s Association (IWA), and attended meetings of the Democratic Federation in 1881, but soon returned to the Liberal Party, standing for Parliament as a Liberal candidate.

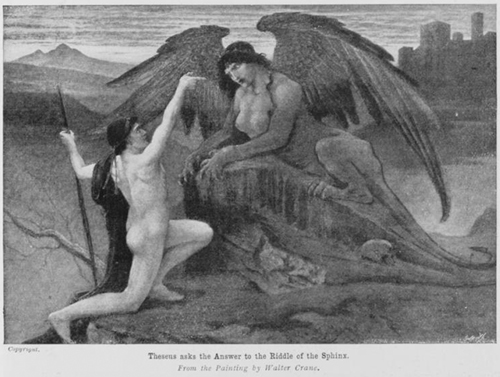

The second indigenous tradition was the spiritual conservatism and moral individualism of Thomas Carlyle. As we have seen previously, this found articulation in the extraordinary prose of Past and Present, where the classical myth of Midas crystallises the relations of production under capitalism, and the Sphinx’s riddle is recast as the problem of class struggle which exploded at Peterloo.3 Carlyle’s questioning proletarian-Sphinx was portrayed by Walter Crane in his (untraced) 1887 oil painting ‘The Riddle of the Sphinx’, for which a compositional study mercifully survives.4 (Figure 23.2) Crane submitted the painting to the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition in 1887, but withdrew it soon afterwards. He believed that its overtly socialist content had upset the organiser, Sir Coutts Lindsay, who had concealed it behind a pillar.5

The answer to the Sphinx’s question was to be articulated rather differently by each of the various Labour and Socialist organisations which soon emerged: the early members of the Independent Labour Party (founded 1893), the Fabians (1884) and the Labour Party (1900) to which the ILP affiliated in 1906, along with charitable and philanthropic organisations, such as the Salvation Army, that were adamantly against revolutionary change.6 The Fabian Society was founded in response to the work in London of New Yorker Dr. Thomas Davidson, a classical scholar and author of Aristotle and Ancient Educational Ideals and The Parthenon Frieze.7 Some members of the utopian group ‘The Fellowship of the New Life’, which gathered around Davidson, split from it and established the Fabian Society. It was named after Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, the Roman general honoured as ‘Delayer’ (Cunctator) after his strategy, recorded in Livy XXII, of gradually wearing down Hannibal’s army rather than confronting it in pitched battle. The title page of the Fabians’ first pamphlet declared,

The name was suggested by Frank Podmore (biographer of Robert Owen) who had studied Classics at Pembroke College, Oxford, and explained it at the society’s first meeting ‘in allusions to the victorious policy of Fabius Cunctator’.9

The early members of the Fabian Society included Beatrice and Sidney Webb, who were to play crucial roles in the Co-operative movement, Trade Unionism and the London School of Economics. They were both suspicious of the upper-class tradition of university education in Classics:10 Sidney was a hairdresser’s son who left school at 15, and Beatrice, although middle-class, like the ardent socialist and secularist Annie Besant, did not study at university. Sidney nevertheless studied ancient civilisation—in translation—assiduously, publishing an unusual sociological interpretation of Roman history which praised the submission of individuals to the collective good even under the worst emperors.11 In the ILP and the Labour Party, on the other hand, there emerged the striking new phenomenon of radical women activists—lower-middle- or working-class—proud of their patrician university qualifications in Greek and Latin.

Women classicists and the ILP

One of the 15 members elected to the ILP’s first National Administrative Council was former Classics teacher Katharine St. John Conway (on marriage, Glasier). Glasier wrote continuously for the socialist press, including the Manchester Sunday Chronicle, the Clarion, and Woman Worker,12 and became Editor of the ILP’s newspaper, Labour Leader, in 1916. She collaborated with her husband, whom she met in 1892, John Bruce Glasier (Keir Hardie’s associate, born illegitimate and forced to work as a child shepherd in south Ayrshire). A vicar’s daughter, she had been classically educated at the new Girls’ Public Day School Company school at Hackney Downs.13 At Newnham College, Cambridge, she scandalised tutors by striking up a romance with a postman she taught on the University’s Extension scheme.14 She then became Classics mistress at Redland High School for Girls in Bristol and mixed with the local Fabians (through whom she met the Webbs) and Christian Socialists. Under her tutelage, the schoolgirls’ results improved dramatically: she successfully prepared 11 girls for Latin matriculation within 18 months of her arrival.15

Glasier inspired Enid Stacy, whose father was an artist friend of William Morris and Eleanor Marx. After excelling in her senior Cambridge examination at the age of 16, Stacy won a scholarship to University College, Bristol, from which, in 1890, she passed the exams for a London BA in Arts (open to women since 1878).16 She took a tutoring position at the same school as Glasier, joined the Gasworkers and General Labourers’ Union in 1889 and supported the Bristol cotton workers’ strike of 1890, becoming Secretary of the Association for the Promotion of Trade Unionism among Women. This strike also changed the life of her mentor Glasier, who joined the Bristol Socialist Party.17 They both resigned from Redlands during the Redcliff Street strike of 1892 to work full-time for the cause, speaking on the ‘Clarion Van’ and in dozens of provincial halls.

Glasier suffered serious poverty after bearing two children.18 Yet she never forgot that she was a trained classicist. One of her most impressive pamphlets is The Cry of the Children, exposing the need for radical reform of the education system, abolition of child labour and state support for all children and mothers. It was published by the Labour Press in Manchester in 1895. She argues from a long historical perspective which adds both intellectual authority and—because she can show that attitudes have differed across cultures—the sense that the current predicament of children is a problem that can be solved. She discusses Sparta, Plato’s Republic and ancient chattel slavery. Like most members of the ILP, Katharine was opposed to the British treatment of the Boers in the Boer War: amongst the lectures she gave on the circuit in Lancashire and Yorkshire was one entitled ‘Roman imperialism and our own’. She was influenced by her close friend Edward Carpenter, also a founding member of the ILP. She cites his important Civilization: its Cause and Cure (1889) in her own visionary tract The Religion of Socialism, in which a white-haired old man, a fusion of Socrates, Aesop and the Christian god, converts her to socialism.19 But the influence went two ways. After a traditional education including Classics at Brighton College, Carpenter had studied mathematics at Cambridge and lectured on astronomy for the University Extension Movement. But he became fascinated by the ancient Greeks, especially Plato and Sappho, as authors who helped him to think cross-culturally about homoerotic relationships. He probably discussed with Glasier the ancient sources on same-sex relationships gathered in his much-reprinted Iolaus: An Anthology of Friendship (1902). This father of British socialist-gay activism also translated both Apuleius and the Iliad in 1900.

Glasier discussed literature and culture with her husband, who remained sceptical of the value of university education, believing that academic professionals always try to appoint right-wingers to top posts; they prefer ‘an uninformed political reactionary because … they want to set up as stiff a political guard as they can for the protection of their class privileges’.20 But he instrumentalised information about the ancient world. One source was his friend William Morris, whom he regarded as a quasi-spiritual leader, invited regularly to lecture in Glasgow and visited in his Hammersmith home, Kelmscott House.21 Morris, despite his disingenuous claim ‘I loathe all classic literature’,22 ‘devoted several of the most fruitful years of his poetic life to the retelling of the stories’ found in ancient texts,23 even if he gave The Life and Death of Jason a medieval colouring. But it was to his wife that Glasier owed his interest in ancient Greek oratory and Platonic aesthetics, and his belief that the ten great thinkers of the world included Aeschylus and Socrates, as well as Shakespeare, Milton and Shelley.24

The other great classically trained woman lecturer in the early ILP, Mary Bridges Adams, emerged through election to a non-parliamentary body, the School Board for London (LSB).25 It had been created as one of many school boards by the Elementary Education Act 1870, which for the first time provided for the education of all children in England and Wales. Crucially, in the LSB women were allowed to vote and stand for election.26 Adams was elected to the Greenwich district seat in 1894, her campaign supported by many other women including Enid Stacy.27 An outstanding biography by Jane Martin has clarified Adams’ achievements. Her parents were Welsh and working-class. Her father was an engine fitter. She studied towards an external degree at the University of London, and matriculated from the College of Science in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In January 1882 she enrolled at Bedford College to study History, Maths, English and French as well as Latin and Greek. In the summer she passed the Intermediate London BA examinations, in the second division but with Distinctions in Maths and in Greek.28

Her academic prowess stood Adams in good stead, being cited by the gas workers who supported her election to the LSB in 1897,29 and impressing men in the top echelons of the socialist intelligentsia, who supported and bankrolled her cultural initiatives in the radical Woolwich of the 1890s. She persuaded many eminent speakers to lecture, wrote in the socialist-feminist magazine Shafts (see above p. 385) appealing for financial help for the labouring classes, and in 1899 organised an exhibition of loaned pictures called ‘Art for the Workers’ in Woolwich Polytechnic, opened by Walter Crane himself.

When widowed in 1900, Adams became a full-time propagandist for socialism. From 1903 she worked as a political secretary for Lady Warwick, whom she recruited for the Socialist Democratic Federation. She believed that working-class adults needed a specific curriculum which would educate them politically. She therefore objected to the classical and liberal educational philosophy which underlay the foundation of both Ruskin College in Oxford (1899) and the Workers’ Educational Association, under the aegis of Albert Mansbridge, in 1903 (see above pp. 195–8). Adams was convinced that there was no alternative but for all the universities—Oxford and Cambridge included—to pass into state ownership and come under popular control. The endowed seats of learning, she argued, were ‘the rightful inheritance of the people’.30

Adams was at the centre of the conflict between the WEA ‘liberals’ and the rebellious Marxist socialists who formed the revolutionary Plebs League and Central Labour College in Earl’s Court, London. Adams immediately responded by opening an equivalent establishment for women nearby, the Women’s College and Socialist Education Centre in Bebel House, into which she moved as Principal.31 Along with the working-class Manchester novelist Ethel Carnie, she taught women workers literacy and numeracy and, through the Bebel House Rebel Pen Club, how to write propaganda.32

Glasier and Adams must have been delighted by the election of Mary Agnes Hamilton, a Newnham classicist, as Labour MP for Blackburn in 1929. Hamilton was employed in 1913 as a correspondent on women’s suffrage and reform of the poor law at The Economist, earning extra money from writing high-end ‘popular’ books about ancient Greece and Rome for OUP’s Clarendon Press. Her Greek Legends (1912) is a well-written prose retelling of the Hesiodic Theogony and the stories of Theseus, Thebes, Perseus, Heracles, the Argonauts, Meleager, Bellerophon and the Trojan War. Her accessible history of the ancient world (1913) covers the entire history of the Greeks and Romans from Hissarlik (supposed site of Troy) to Julius Caesar. In the 1920s she wrote, for a general audience, Ancient Rome: the Lives of Great Men (1922) and a new book about Greece (1926). Being an acknowledged expert in the history of the classical world lent authority to her biographies of Abraham Lincoln, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Carlyle and Ramsay MacDonald, as well as a lucid textbook The Principles of Socialism, published ‘with notes for lecturers and class leaders’ as the second in the ILP’s series of study courses.

Classical scholars in the CPGB

The third intellectual strand in British socialism was the thought of Marx and Engels that underlays revolutionary Communism; Marx had himself been a more than competent classicist, whose ideas drew to an extent, hitherto inadequately acknowledged, on the Chartist Bronterre O’Brien’s detailed study of ancient slavery.33 The Communist Party of Great Britain was founded in 1920. Inspired by the Russian revolution, the four major Marxist political groups which combined to form it were the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), the Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers’ Socialist Federation (WSF).34 Although the CPGB never became a mass party like its equivalents in France or Italy, it exerted an influence out of proportion to its size, partly because there were always links between its members and those of the mainstream Labour Party. At the time of the General Strike in 1926, the CPGB had about 10,000 members. Its first MP, William Gallacher, was elected by the miners of West Fife in Scotland in 1931. Although by 1936 the leaders were divided over support for Joseph Stalin and reports of his purges, the situation in Spain to an extent diverted the membership’s attention. British Communists were crucial in the creation of the International Brigades which went to fight for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

While the Fascists gained power in both Germany and Italy, the membership of the CPGB steadily increased. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, and Churchill announced that Britons and Russians were now close allies, party membership soared to 56,000. At the end of the war, two communists were elected to parliament in the General Election. This was the historic moment at which the CPGB enjoyed its greatest popularity.

During the party’s first two and a half decades, it was joined by many leading intellectuals. Christopher Hill has argued that English Literature was their dominant original interest.35 But the British Marxist intellectual tradition was founded just as much on literature in Latin and Greek: Eric Hobsbawm regards the Classicists as ‘the most flourishing group’ amongst the CPGB intellectuals.36 The earliest of the classical scholars who were members of the CPGB was Benjamin Farrington. He graduated in Classics from University College, Cork, and then moved to Trinity College, Dublin, to take another degree in Middle English. As Atkinson has pointed out, Farrington would have been in Dublin in 1914, when the new Provost of TCD, the renowned historian of ancient Greece J.P. Mahaffy, banned a meeting of the Trinity College Gaelic Society because one of the speakers was to be an opponent of recruitment, Patrick Pearse.37 Mahaffy later wrote that he had loathed Farrington; there was no love lost between the high-handed Provost and his left-leaning undergraduate.38

Farrington’s political views were shaped by the plight of the working class in Ireland, which came to a head in the Dublin ‘lock-out’ of 1913, a traumatic industrial dispute between factory owners and thousands of slum-dwelling Dubliners fighting for the right to form trade unions. Farrington was affected by the speeches of James Connolly, a Scottish Marxist of Irish descent. His radicalism received an academic focus when, in 1915–1917, including the period of the 1916 Easter Rising, he was reading for his Master’s degree in English from University College, completing his thesis in 1917 on Shelley’s translation from the Greek.39 After lecturing in Classics at Queen’s University, Belfast, he moved to the University of Cape Town in South Africa, where he studied the racist and nationalist legacies of European imperialism at first hand. In four articles he wrote for the Afrikaans newspaper De Burger between 15th and 24th September 1920, he tried to foster Afrikaner support for Sinn Féin and the Republican wing of the new Dublin-based national government.40

But Farrington’s interest in Marxism, opposition to racism and an increasing distrust of both the Boer cause and the de Valera administration in Ireland, soon led him to give up active participation in politics. He preferred working on what Marxists call ‘the intellectual plane’ to rewrite the world, including the ancient world, from a materialist and labour-focussed perspective. He was promoted to the Chair of Latin in 1929, but left Cape Town in 1935 as the first steps towards institutionalised Apartheid were taken. He worked at the University of Bristol for a year before becoming Professor at University College, Swansea, in the heart of the Welsh industrial and mining region, where he remained for 21 years.

Farrington achieved a high profile in the UK and Ireland, his major academic contribution being to the history and philosophy of ancient science, expressed in a series of pioneering if controversial books. The Civilization of Greece and Rome (1938) was an important attempt to make ancient history available to working people beyond the Academy. Farrington’s lively, lucid materialist analyses of the relationship between the ancient economy and ideas were often derided by mainstream classical scholars, but they were (and still are) widely read by the more open-minded among them. His commitment to Communist ideals, born in the chaos leading up to the Easter Uprising, was lifelong. He taught on socialist summer schools and to working men’s educational societies. His pamphlet The Challenge of Socialism resulted from a series of lectures he delivered at weekend schools in Dublin in August 1946.41 In England, some of the younger members of the CPGB in the 1930s only later went on to become prominent academic classicists. Frank William Walbank (1909–2008) was born in Bingley, West Yorkshire. He received his classical education at Bradford Grammar School and Peterhouse, Cambridge, and from 1951 to 1977 was Rathbone Professor of Ancient History and Classical Archaeology at the University of Liverpool. His name is inseparable from that of Polybius, on whose Histories he wrote the definitive commentary, published in three volumes in 1957, 1967 and 1979. He became increasingly sympathetic to the cause of the working class in the 1920s; along with his politically active wife he joined the CPGB in 1934. Yet the implicit Marxist element in his views of history and historiography has never been properly investigated.42 The Marxism is more explicit in the case of Geoffrey de Ste. Croix (1910–2000). He had been trained in Classics at Clifton College, a fee-paying private school in Bristol, but left school at 16 and did not go straight to university, training instead as a lawyer. During the 1930s he practised in London and was a member of the CPGB and the Labour Party; unlike Walbank, he was one of many who left in 1939 after the Nazi–Soviet pact. It was not until he was released from the RAF in which he had served during the war, that he entered London University to study Classics; he then pursued a brilliant academic career, took up a position at New College, Oxford, in 1963, and wrote his two ‘classics’ of Ancient History from a Marxist analytical perspective, The Origins of the Peloponnesian War (1972) and The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World (1981). His two youthful periods of exposure to classical education therefore preceded and followed his period of intense exposure to Marxist ideas as a lawyer and CPGB member in the 1930s.

Robert Browning (not related to the famous poet), born in 1914, was de Ste. Croix’s junior by four years. Although he never achieved the same fame (or notoriety), his books were and still are widely read, usually by scholars who have no idea that he was a lifelong idealistic Communist Party member. Brought up in Glasgow during the terrible poverty on Clydeside in the 1920s and 1930s, he studied Humanities at Glasgow University, and may have joined the CPGB at that time. He was certainly a member soon after he arrived at Balliol College, Oxford in 1935. There he won almost every available prize and scholarship for his performances in Latin and Greek, even as he immersed himself in CPGB activities and Marxist theories of history. He spent most of his working life at London University, first at UCL until 1965 and thereafter until 1981 as Professor of Classics and Ancient History at Birkbeck College. He was still lecturing at the CPGB headquarters on Marxism and History in the mid-1980s, when Edith Hall attended.

The fifth 1930s CPGB classicist was George Derwent Thomson (1903–1987), who studied Classics at King’s College, Cambridge but then moved to the National University of Ireland (Galway), where he was swiftly promoted to the professorship. In western Ireland in the 1920s he became radicalised by contact with the Gaelic-speaking population, newly liberated from British imperialism. He learned to speak their ancient language, translating works by Plato (1929), Aeschylus (1933) and Euripides into it (1932). His first scholarly commentary, published in 1932, was on the favourite ancient play of radicals since the 18th century, the Aeschylean Prometheus Bound. By the time he moved back to a lectureship at King’s College, Cambridge, in 1934, he was an ardent socialist, and he joined the CPGB in 1936, when he also accepted the chair of Greek at Birmingham University. An industrial city with a large automobile industry, Birmingham offered him many opportunities to teach working-class men as well as full-time university students.43

Thomson was intellectually restless and enjoyed controversy. By the early 1950s he had come into conflict with the leadership and ideological programme of the CPGB. He became increasingly interested in China and Maoism. In the intervening period, from 1936 onwards, he produced a stream of publications which were informally blacklisted at Oxford, but widely read outside the Classics establishment in Britain, and indeed were on the syllabus of many departments of Anthropology and Sociology as well as the reading lists circulated by workers’ educational organisations. In 1938 he published his impressive two-volume commentary on Aeschylus’ Oresteia, which still needs to be consulted by any scholar working on that text. But the work of classical scholarship with which he will always be primarily associated was his 1941 Aeschylus & Athens, a Marxist anthropological study of early Greek tragedy, published by the press most closely associated with the CPGB, Lawrence & Wishart. In 1949 he followed this with The Prehistoric Aegean, and in 1954 with The First Philosophers, making a ‘trilogy’ of Marxist interpretations of ancient Greek civilisation from the Bronze Age to Periclean Athens. Generally derided in British, classical circles, Aeschylus and Athens nevertheless became well-known internationally, being translated into Czech, Modern Greek, Polish, Russian, Hungarian and German.

Erudite activists

Besides the Communist Classics dons, there was a substantial group of CPGB intellectuals who did not operate within the ‘Ivory Tower’ but in the public world of letters. In the 1920s and 1930s they were often associated in the public imagination with ‘fellow-traveller’ poets and authors such as Siegfried Sassoon (see above p. 467), W.H. Auden, Louis MacNeice and Naomi Mitchison. Sassoon’s socialist activism has often been overlooked.44 Auden’s politics are clear enough from the beggars, the ‘lurcher-loving collier, black as night’ and the lonely Roman soldier on Hadrian’s Wall in ‘Twelve Songs’, composed in the 1930s.45 MacNeice, the public-school-educated Anglo-Irish lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham between 1930 and 1936, ironically pondered the relationship between the ancient languages and social privilege in his autobiographical poem Autumn Journal (1938):

Naomi Mitchison (1897–1999), a convinced Socialist and in 1935 a Labour candidate for parliament, had studied Classics at the Dragon School in Oxford, and even performed in a production of Aristophanes’ Frogs as a teenager;47 her first two novels were experimental works of historical fiction responding to the carnage of World War I, set respectively during Caesar’s campaign against the Gauls (The Conquered, 1923) and Athens during the Peloponnesian War (Cloud Cuckoo Land, 1925). Her masterpiece is The Corn King and the Spring Queen (1931), set in Hellenistic times on the northern coast of the Black Sea in a half-Hellenised barbarian community. It is written under the influence of radical feminism, Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris and Frazerian ritualism.48

None of these famous authors took out membership of the CPGB, despite sympathy with its aims, but other literary figures did. Christopher Caudwell (1907–1937) was an energetic party activist, poet and the author of a work of literary theory influential in British left-wing circles, Illusion and Reality, published after his death in the Spanish Civil War in 1937. His real name was Christopher St John Sprigg, and he was a member of the educated Roman Catholic middle class. At 15 he was forced to leave his Benedictine school, where he had learned both Greek and Latin; he soon became radicalised when his father lost his job as literary editor of the Daily Express newspaper, joining the CPGB in London.49

There is a debt to Classics in Caudwell’s poetry. He translated Greek epigrams. His finest poem, ‘Classic Encounter’, laments recent war fatalities. The ‘I’ voice meets the Athenians who had died miserably in Syracuse in 413 bc (described in tragic detail in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War book VII) after the military debacle that concluded Athens’ disastrous invasion of Sicily. The speaker mistakes them for those fallen in the Gallipoli campaign of 1915–1916, when combined British and Anzac fatalities alone are estimated at 76,000. The poem thus draws a parallel between the victims of warmongering generals in the Mediterranean at distances of more than two millennia.50 ‘Heil Baldwin!’ (1936), a satire on the Anglo–German Naval Agreement of 1935, is framed as a pastiche of the Aeneid, opening ‘Arms and the man I sing’.51

Yet Caudwell’s poetry, like the classical foundations of his major work on aesthetics and society, has largely been ignored. Chapter 2 of Illusion and Reality, ‘The Death of Mythology’, is essentially a study of Aristotle’s Poetics. Caudwell’s fundamental thesis is inspired by the argument between Plato and Aristotle on the relationship between the empirically discernible world (reality) and the worlds conjured up in art (mimesis). Caudwell writes that ‘Aristotle’s theory of mimesis, as our analysis will show, so far from being superficial, is fundamental for an understanding of the function and method of art’.52 He is here linking Aristotle’s theory that all art was fundamentally mimetic of reality with his theory that tragic art’s aim is the production of a socially beneficial function by somehow addressing the painful emotions aroused in tragedy. His teleological model of the evolution of genres resembles Aristotle’s teleological description of the development of tragedy and comedy in the Poetics. But other things have impressed Caudwell about Aristotle: he analyses literature as a social product—a body of cultural data to be analysed for what it can tell us in its own right, rather than as an expression of the individual writer’s subjectivity.53 There were other influences on Caudwell, besides Marx and Engels, including I.A. Richards and Nikolai Bukharin. But Aristotle’s Poetics shaped both the form taken by the questions Caudwell asked and his answers.

Caudwell worked in isolation from other CPGB literary figures. His posthumous reputation was established by Professor George Thomson. But several other party members saw the maintenance of a debate on the role of the arts in society as a collective enterprise. The Left Review, first published in October 1936, was a response to the rise of fascism in Europe and a platform for the development of Marxist literary criticism and socialist literature and art. One of the founding editors was the writer and activist, Edgell Rickword, also instrumental in the formation of the Left Book Club and the British Section of the Writers’ International. Before its final issue (May 1938) the Left Review was the mouthpiece of the British Left and attracted impressive contributors’ reviews of literature, poems, short stories and songs on communist themes, some even for mass declamation. Satiric cartoons and jocular advertisement campaigns served to lighten the tone. The democratisation of culture was an important goal, and therefore one of the key preoccupations of the early contributors was the British education system and the role of the classical education within it.

Cecil Day-Lewis (1904–1972), poet laureate in the 1960s and now known mainly by his accessible translations of Virgil, was a regular contributor to the Left Review and a CPGB member from early 1936.54 He wrote—in an article entitled ‘An Expensive Education’—that just as capitalism in its earlier phases was a progressive force … necessary for the higher development of the means of production, so was the classical education … necessary for the development of the human mind.55

Now, he explained, both forces had become reactionary, and the teaching of the Latin language, in particular,

Not to be outdone, the poet Randal Swingler (1909–1967), editor of the Daily Worker (1939–1941), regular contributor to the LR and a CPGB member since 1934, claimed that ‘the present state of classical education is the most efficient method designed for arresting the development of the individual mind’. He argued that ‘to boys whose minds have been hammered out on the anvil of grammar’ a knowledge of classical literature is nothing more than a knowledge of texts, and that culture, by extension, became a thing divorced of life, the ‘possession’ of a gentleman and no longer a ‘function, or rather the condition of a function’ of man.57 Swingler had been expensively and classically educated at Winchester and then New College, Oxford.

The traditional British method of classical education, which had indeed often functioned to exclude the lower classes from accessing middle-class careers and institutional power,58 had always been considered, by some in the British Labour movement, an enemy of socialism. Attempts made by writers to engage with the material of classical culture in ways that bypassed the socially corrosive landscape of the classical education were welcomed. One of the most prolific of the writers associated with the Left Review was Jack Lindsay (Figure 23.3), the Australian-born classicist awarded a znak pocheta (badge of honour) by the Soviet government in 1968. He wrote a biography of Mark Antony, about which the scholar George Thomson effused:

Thomson called the Late Roman Republic ‘an excellent field for Marxist research’ and explained that the great merit of Lindsay’s book was that he ‘exposes the real nature of the forces that brought about the fall of the Republic’.59

Lindsay, the son of the famous Australian artist Norman Lindsay (1879–1969), was born in Melbourne in 1900, brought up from the age of 5 in Sydney, and won scholarships to Brisbane Grammar School and the newly founded University of Queensland. There he studied Classics under the Scottish Professor John Lundie Michie, developing the skills in translation he would exploit for the rest of his life. Michie was the son of an Aberdeenshire blacksmith and a celebrated beneficiary of the north-eastern Scottish educational system discussed in Chapter 11.60 After university, Lindsay continued to write and translate poetry, while eking out a living as a Workers’ Educational Association of Australia lecturer. He arrived in London in 1926, the year of the General Strike. He met left-leaning middle-class literary men, including Rickword, Douglas Garman and Alec Brown.61

His relationship with Rickword (1898–1982) was intellectually intense. Rickword had studied Classics amongst other subjects at Colchester Royal Grammar School, before fighting on the Western Front briefly in 1918. He later commented on his experience of the war, in Literature and Society (1940), ‘It was not the suffering and slaughter in themselves that were unbearable, it was the absence of any conviction that they were necessary, that they were leading to a better organisation of society’.62 In his poem, ‘Fatigue’, the fetishisation of ancient Greek culture represents the lost dreams of obsolete ruling classes resisting human progress towards a better world.63 His political views intensified when he could not live on his disability benefit after losing an eye, and he was an ardent supporter of the General Strike. He became convinced that Marxist theory was the best way to understand the world during a conversation with Lindsay about Aristophanes and Athens, and in 1934 he joined the CPGB. Rickword gave up poetry, and worked for Lawrence and Wishart. He subsequently edited a prominent left-wing review called Our Time, and was convinced that classicism was not good for poetry, criticising the Imagists thus: ‘All that Grecian business, a Greece that never had been’.64

A colleague of both Rickword and Lindsay, Douglas Garman won a scholarship in Classics to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, spent the 1920s between London and Paris, and was in Leningrad in 1926. With Rickword, he edited and wrote for a journal, The Calendar of Modern Letters, which briefly appeared from March 1925 as a monthly literary review. A committed activist, Garman was Education Organiser of the CPGB from 1934 until at least 1950, and remained a member until he died in 1969. Lindsay, meanwhile, did not become a convinced socialist until around New Year 1936, after the editor of his book Rome For Sale (1934) added a preface in which he compared the Catilinarian revolt with Fascism and the start of the Spanish Civil War.65 He then embarked on a lifelong and somewhat gruelling struggle with Marxism and the increasingly dogmatic postwar Communist Party.

In the mid-1930s Lindsay’s writing changed ideological gear. There is a Marxist line running through his book for a broad popular audience The Romans (1935), part of the ‘How-and-Why Series’, edited by Gerald Bullett. Lindsay explicitly did not ‘seek to tell the story of her [Rome’s] wars and all the romance of her long adventurous career’, but instead preferred, ‘to unravel some of the main qualities that made a small Italian hill-town the most important factor in the building of modern Europe’.66 In a chapter entitled The End of Farmer-Aristocracy he writes,

The New Zealand-born classicist Ronald Syme reviewed The Romans from Trinity College, Oxford. Aside from a couple of points of detail, the review is entirely positive:

Subscribing to the Daily Worker and plunging into the politics he had previously avoided, Lindsay realised that his old London friends, Rickword, Garman and Brown were following the same path, and that ‘in Left Review there was a rallying-point of the movement’.69 Lindsay’s first piece for the Left Review was a seven-page declamatory poem called ‘Who are the English?’70 It was reprinted, circulated as a pamphlet71 and performed by the recently formed Unity Theatre, the dramatic limb of the CPGB. Rickword asked him to write a similar poem on the Spanish Civil War, which produced the famous song ‘On Guard for Spain’. This poem was quickly developed into a text designed for mass declamation all over England by socialist theatre groups.72

In his autobiography, Lindsay explains that if he were asked to summarise what his work since 1933 was about, he would answer: ‘The Alienating Process (in Marx’s sense) and the struggle against it’.73 Such words from the mouth of a committed Marxist are no surprise, but it is notable that his own ‘struggle against it’ took a predominantly classical form. He published 11 historical novels based in the Greco-Roman world, the majority in late Republican Rome. One, To Arms (1938), was aimed at young people and set in ancient Gaul. He produced seven book-length translations from Greek and Roman literature, mainly poetry; some were anthologies, including the accessible and cheaply printed collections Ribaldry of Rome and its twin Ribaldry of Greece (1961). Amongst his historical non-fiction are his biography of Mark Antony (1936), The Romans were Here (1956), Our Roman Heritage (1967) about Roman Britain and Leisure and Pleasure in Roman Egypt (1965). Song of a Falling World (1948), probably his most well-received contribution to scholarship, is a Marxist history of the declining Roman Empire based on discussion of the period’s poetry.

Lindsay produced around 160 books in his lifetime.74 His classical output, in terms of books of which he was principal author, amounts to over 40 titles between 1925 and 1974. From the beginning of his writing career he expressed little interest in ancient authors who had, through the 19th and earlier 20th centuries, gained the ‘classical’ stamp of academic authority (especially Virgil and Cicero). He preferred to work with what he regarded as ancient ‘popular literature’ and especially that written by those he considered outsiders. He is now occasionally acknowledged as having usefully popularised the ancient novel, mime and everyday social world of the Oxyrhynchus papyri.75 He was drawn to the poetry and prose of the spoken word, not the ‘deadening side of the tradition’, which he considered to have been fetishised by traditional ‘academic criticism’.76

His favourite classical authors included the demotic and obscene Herodas (whom he first translated in 1930), Petronius (whose Satyricon and poems he translated in 1927), Apuleius (whose Golden Ass he translated first in 1932), Longus (whose Daphnis and Chloe he translated in 1948), and Aristophanes (whose Lysistrata and Ecclesiazusae he translated in 1925 and 1929 respectively). He was especially fond of Theocritus, whose poetry he first translated in 1929 and saw (as he said in an article advocating mass declamation as a political instrument) as being beautifully alive ‘because it is tissued in a poetry derived in large part from popular Mimes’.77 His lifelong passion, however, was for the poetry of Catullus, which produced not only two different full translations of his works, the first as an exclusive fine press edition in 1929, and then in 1948 as an affordable commercial edition,78 but also his first trilogy of historical fiction, i.e. Rome for Sale (1934), Caesar is Dead (1934), Last Days of Cleopatra (1935c); also Despoiling Venus (1935), which is a narrative delivered in the first-person voice of Caelius Rufus, and finally Brief Light (1939), a fictionally embellished biographical account of Catullus.

Lindsay’s Marxism gave him an ideological bedrock from which he could spring into the ancient world and an intellectual method of socio-economic analysis into which he could pour his substantial literary experience and his powerful imagination. The new angle on the ancient world that the hopeful, creative Marxism of the 1930s offered simultaneously repelled the traditional Ivory Tower classicists from his work, and attracted other Marxist intellectuals, like Browning and Thomson, who could see how such pioneering work could re-energise the traditional ‘stultifying’ realm of Classics. Lindsay’s skill as a translator of Greek brought him right to the foot of the Ivory Towers, if never through the door, when he contributed translations to The Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation (1938), edited by T. F. Higham and C.M. Bowra, which accompanied The Oxford Book of Greek Verse (1930). The neglect of Lindsay in mainstream cultural history offers one of the most spectacular examples of the absence of people’s Classics from our histories of the discipline.

Two factors have contributed to this occlusion. First, the traditional suspicion of linguistic classical education on the British Left. This was best articulated by Will Crooks, son of a ship’s stoker from Poplar, East London, and close friend of Ben Tillett,79 who became only the fourth ever Labour MP in 1901 (Figure 23.4). He famously asked the Conservative Prime Minister 1902–1905, Arthur Balfour, to refrain from speaking in Latin in parliament.80 The other factor is the continuing discomfort, both inside and beyond the Ivory Tower, with excavating the history of British communism. There remains much work to be done investigating the instrumental presence of classical ideas and texts across the different political constituencies that made up the British Labour and Socialist movements, especially via the intellectual work at the heart of the CPGB. One way of continuing this project would be to investigate Andy Croft’s fascinating collection of novels featuring CPGB members, written by card-carriers including Upward, Brown and Lindsay, many fellow travellers and also some writers more hostile to the cause.81 It is fascinating to learn from Croft, for example, that in the first draft of Lady Chatterley’s Lover by the classically educated Nottinghamshire miner’s son D.H. Lawrence, Oliver Mellors the gamekeeper was secretary to his local cell of the Communist Party in Sheffield.