14

Underdog professors

Introduction

Until the Butler Education Act 1944, although it was most unusual for individuals born into low-income families to acquire sufficient education in the ancient languages for them to rise within the academic profession, it was not entirely unknown. It required extraordinary autodidactic efforts, like those of Joseph Wright, who eventually became Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford University. It also usually required financial support, which only happened if a working-class boy’s academic talent was spotted by an ambitious parent with the confidence to pursue middle-class contacts, a benevolent parish priest or a teacher at a Charity or Dame School, Dissenting teacher, or paternalistic wealthy local patrons on the lookout for prodigies amongst the impoverished families eking out a living on or near their estates. Their education was sometimes procured via scholarships at one of the old Charity or Bluecoat Schools; rich sponsors, especially Nonconformists, sometimes subsidised study at university.

A few working-class men became competent classicists before brilliant careers in, for example, academic philosophy. Henry Jones (1852–1922) was a village shoemaker’s son from Denbighshire who rose through scholarships at Bangor Training College for Teachers and Glasgow University to hold chairs in philosophy at the universities of Bangor, St. Andrews and Glasgow and received a knighthood. Ever proud of his lowly roots and his Welshness, Jones was early inspired by the authors of ancient Greece and Rome. This is apparent above all in his Essays on Literature and Education (1924), a brilliant set of essays on popular authors in the English language and on the purpose of education. Scott’s storytelling is compared to Homer’s, Shakespeare’s morality to Sophocles’, the Brownings’ debt to their education in Greek and Latin and to Euripides’ erudition and Aeschylus is stressed.1 When it came to revelling in the richness of ancient literature, Jones was a classicist to the core. He opened his 1905 address to the subscribers of the Stirling and Glasgow Public Libraries, ‘The Library as a Maker of Character’, with an inspirational quotation from Benjamin Jowett’s translation of the opening sequence of Plato’s Phaedrus, when Socrates goes for a country walk with Phaedrus after meeting the young man with a book under his arm (230d): ‘I am a lover of knowledge’, said the ancient sage,

Welsh men destined to become Methodist preachers were also often trained rigorously in Greek, as we have seen above in the case of Lewis Edwards and his son Thomas (pp. 179–82). But a tiny handful of working-class men made their academic mark specifically on Classics or Comparative Philology. The obstacles which lay in the path of bookish youths from a humble background were considerable, and there were large variations in their attitudes in later life to other members of the social class from which they had emerged, escaped or had even betrayed, depending on their personal perspective. This chapter looks in detail at five such figures—three of whom were associated with the University of Edinburgh—in the 18th and 19th centuries, but there is undoubtedly far more work to be done in this area, especially on academics of the 20th century. By that time, careers in Classics were occasionally achieved even by women who were originally working-class, such as Kathleen Freeman at the University College Cardiff.3

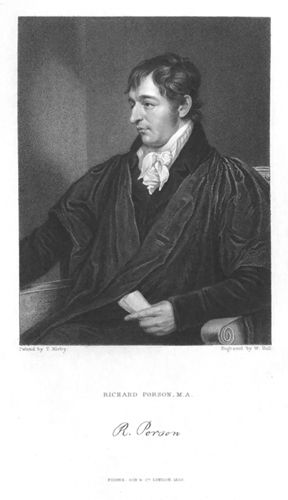

Richard Porson

The most arresting example is Richard Porson (1759–1808), a weaver’s son from rural Norfolk (Figure 14.1). His mother, a cobbler’s daughter, was clever and literate and ensured he attended the village school regularly, followed at the age of nine by the Free School in the village of Happisborough. A local nobleman, impressed by the boy’s classical prowess, paid for his education to be continued at Eton.4 Porson did not enjoy the school, later saying that the only thing he remembered with pleasure was rat-hunting on winter evenings.5 He seems also, however, to have performed enthusiastically in musical burlesques there; he could recall them word-for-word in later life, and used to sing raucous Vauxhall songs in elegant society, incurring opprobrium thereby.6

Several other patrons financed Porson’s studies at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was elected a Fellow; at some point during this earliest part of his career, he took a position as private tutor to a gentleman’s son on the Isle of Wight, but was sacked ‘having been found drunk in a ditch or a turnip field.’7 In 1792, when it was decided that fellowships were no longer open to laymen, Porson declined to take holy orders and so lost his stipend. Unwillingness to take orders in fact took courage, since no great piety was required of the academic clergy at that time, and there was small chance of earning an adequate living outside schools or universities.8 Porson was proud, principled and politically radical, supporting the French Revolution in its early days, advocating parliamentary reform, attending the House of Commons debates in 1792 on the Birmingham riots9 and adamantly opposing Pitt’s government.10 Porson’s reputation consequently suffered at the hands of conservative critics such as De Quincey, who alleged incorrectly that Porson read no poetry at all ‘unless it were either political or obscene’.11

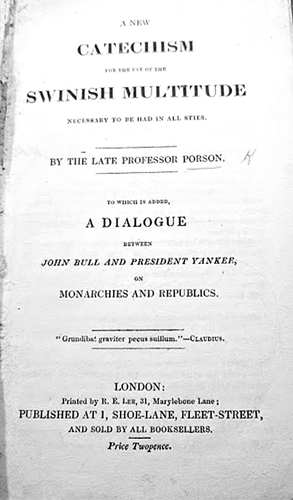

This working-class prodigy was responsible for what have been dismissed as ‘ephemeral productions’, but were, rather, clever uses of classical material to make political points.12 In 1792 Porson published a satirical attack, later republished by Richard Carlile (on whom see Chapter 13, pp. 278–83), A New Catechism for the Use of the Swinish Multitude, Necessary to be Had in all Sties, (Figure 14.2) on Burke’s Reflections on the French revolution. Burke had claimed that learning had been ‘trodden down under the hoofs of the swinish multitude’: Porson’s swine portray their suffering under the Hog Drivers. It is a witty piece. Any doubt that its target is Burke disappears with the second question, ‘Did God make you a hog?’, to which the prescribed answer is ‘No; God made me man in his own image; the Right Honourable SUBLIME AND BEAUTIFUL made me a swine’.13 To the question whether the resolutions made by the ruling class hog-drivers can be read by the hogs, the answer is no, because scarcely one in 20 hogs can read. The questioner says, ‘They are written in Hog Latin, but that I took for granted you could understand’, to which the hogs retort (remarkably, given that the author is a Classics Professor), ‘Shameful aspersion on the hogs! The most inarticulate grunting of our tribe is sense and harmony compared to such jargon.’14 But all is not lost, because the questioner notices that the pigs’ spokesman talks sense, and asks ‘whence had you your information?’ The answer is ‘From a learned pig’, of which there are ‘many; and the number daily increases.’15 Porson is aware of the democrats’ emphasis on working-class self-education. ‘The allegory is obvious enough, and so are the Jacobinical sentiments’.16

Porson also wrote some ‘Imitations of Horace’ in The Morning Chronicle in 1794. One published on 12th August was an imitation of Odes 1.14, which he turned into an attack on Pitt, a ‘cub that knows not stem from stern’.17 The third, on 13th September, on Ode 1.34, uses Horace’s problem that he had fought for the Republicans to comment on the contemporary clampdown on freedom of the press.18 Porson prefaces his Hymn of a New-Made Peer to his Creator, savaging Pitt’s additions to the peerage, with a quote from Athenaeus.19 He became embroiled in the trial of William Frend, Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge, who was accused of attacking the established church; in three raucous, uncompromising letters signed ‘Mythologus’, entitled ‘Orgies of Bacchus’, Porson defended the principle of freedom of speech on religious and political matters, through ‘a learned though flippant account of the career of the god Bacchus, and the spread of his worship, written in terms that are clearly meant to suggest Christianity and its founder’.20 He also undermined the credibility of the chief prosecutor in the Vice-Chancellor’s court, Dr. Kipling, by wittily exposing Kipling’s ropey grasp of Latin in a Latin poem and epistle published in The Morning Chronicle.21 Porson was effectively using his own excellence at Classics to defend illegal political views against the mediocre scholarship of a defender of the establishment. No wonder that Porson’s early biographers were so shocked by these texts that they assumed he was mentally unstable when he wrote them, advised that they be left unread, and even attempted to disguise one objectionable portion by translating it into Latin.22 The ultra-conservative Denys Page ignored them completely in his 1959 lecture, on the bicentennial of Porson’s birth, to the International Congress of Classical Studies.23

From 1792 onwards, Porson was supported by an annuity raised from friends’ subscriptions. He is remembered for Porson’s Law, applied to Greek tragic metrics, alongside the Porson Greek typeface based on his own handwriting, as well as his acclaimed textual work on Greek drama. Yet his lack of social niceties, foul mouth and capacity for alcohol were notorious. He regularly passed out in company and fell asleep under the table.24 His antics shocked even Lord Byron who, in a letter of 1818, likened his behaviour to that of Silenus: ‘Of all the disgusting brutes, sulky, abusive, and intolerable, Porson was the most bestial’; when he thought people were ignorant, he insulted them ‘with the most vulgar terms of reprobation’. Byron elaborates this unlovely picture: ‘He used to recite, or rather vomit, pages of all languages, and could hiccup Greek like a helot’.25 Since Byron did not usually object to drunkenness, the language here—‘vulgar’ and ‘helot’—implies snobbery based on social class. Porson probably had what we would now call a photographic memory, which was a source of misery to him as ‘he could never forget anything, even that he wished not to remember’.26 Such memories no doubt included those of his own lowly upbringing. His dislocation from his class roots may have contributed to his alcoholism, which killed him in 1808.

One witness, T.S. Hughes, remembers an encounter with Porson at Cambridge in 1807 in which Porson’s conversation throws some more sympathetic light on the way his boorish conduct might have been born out of vestigial loyalty to the class into which he was born. Stories of the generosity or democratic fervour of ancient heroes out of Plutarch regularly reduced him to tears.27 He told Hughes that he had become a misanthrope from an excess of sensibility, which his sympathetic defence of the poor pigs in his Catechism would support. One day a ‘girl of the town’ came into his chambers ‘by mistake’. She ‘showed so much cleverness and ability in a long conversation with him, that he declared she might with proper cultivation have become another Aspasia’.28 He remained thoroughly indifferent to money and unimpressed by social status.29

Upwardly mobile Edinburgh professors

Porson once wrote a fractious letter complaining about the criticisms of his edition of Hecuba (1797) published in a review by a more contented working-class Greek prodigy, Andrew Dalzel (1742–1806).30 Dalzel was a carpenter’s son who rose to be a leading Edinburgh intellectual. He was born on the Newliston estate in Linlithgowshire; his father died when he was still small, but his talent for languages was spotted at parochial school.31 Thence he progressed, helped by a friendly local Laird, to Edinburgh University. By 1779 he had succeeded to the Chair of Greek, which he held for over 30 years (Figure 14.3). In 1785 he received the additional appointment of University Librarian. Dalzel turned Greek Studies at the University around; it had dwindled to almost nothing under his predecessor. He soon had over a hundred students enrolled. He was proud of the standards of learning they achieved, contrasting them with those at Oxford and Cambridge, where ‘dissipation, idleness, drinking, and gambling’ predominated. ‘The English Universities are huge masses of magnificence and form, but ill-calculated to promote the cause of science or of liberal inquiry.’32

Dalzel’s Analecta Graeca Minora was used across Britain, in schools as well as universities, reprinted for decades and made his name popular throughout the world of Classics.33 His lectures on the ancient Greeks were published after his death by his son John.34 In the manuscript which was transcribed, Dalzel wrote trenchantly that the category ‘the vulgar’ was class-blind: it included ‘not only the artisan and the peasant, but also such of the opulent as have made no use of the advantages of education’.35At Edinburgh University, where he studied Classics from the age of 12, Walter Scott recalls incurring the irritation of Dalzel by an essay placing Homer behind Ariosto in poetic merit.36 But when it came to poetry in the English language, Dalzel abhorred the ignorance of many classically educated men; in his lectures he attempted to give his students ‘a faint view of the beauties of English authors’.37

When Robert Burns arrived in Edinburgh, Dalzel wrote enthusiastically, ‘We have got a poet in town just now, whom everybody is taking notice of—a ploughman from Ayrshire—a man of unquestionable genius.’38 He praises many English-language works, including the Epigoniad of William Wilkie (see pp. 335–6), in which he says there are some ‘sublime’ passages, such as the death of Hercules in Book VII. Dalzel quoted more than a hundred lines from the Epigoniad in the final lecture of his series on epic.39 A strength of the lectures is Dalzel’s interest in what would now be called ‘Classical Reception’; he repeatedly refers to the impact that the ancient Greeks had on previous generations of moderns—Thomas More’s Utopia, Harrington’s Oceania and Milton, whose love for the Greeks meant that he ‘suffered himself to be transported, too far indeed, with a passion for popular government’.40

For Dalzel, unlike Porson, was no critic of the British ruling class. He was friends with Edmund Burke, and much admired him.41 He was dismayed that there were radicals, whom he calls ‘violent politicians’, in the Edinburgh Royal Society who had voted against allowing Burke membership.42 His letters suggest that the Edinburgh sedition trials (on which see pp. 275–7) passed him by altogether. His meticulously detailed History of the University of Edinburgh is almost eerily apolitical in its recitation of the names of staff and introduction of courses during the revolutions of the 17th century.43 He even concluded his lecture course on ancient constitutional history with a eulogy of the British constitution, which avoided, he said, the vices of extreme monarchy, aristocracy and democracy alike.44 But he wholeheartedly believed, and stressed in the first lecture that young men heard in his course on ancient Greece, that the point of a classical education was to learn

Dalzel was an inspirational teacher, even getting his students to perform an English-language version of Theocritus’ Idyll on the Women of Syracuse in class.46 He was also exceptionally hardworking, teaching two two-hour classes daily. The first inculcated the Greek language through engagement with Lucian, Homer, Xenophon, Anacreon and the New Testament. The second class, which was itself divided into groups depending on level of linguistic attainment, focussed on Thucydides, Herodotus and Demosthenes, supplemented by more Homer, some tragedy and Theocritus. Dalzel also gave two lectures a week on ‘the history, government, manners, the poetry and eloquence’ of the ancient Greeks.

His student Lord Henry Cockburn recalled him as

But the tenor of Dalzel’s aesthetic views emerges from his censorious dismissal of the comedies of Aristophanes at the end of his lecture on comedy:

But the prim and conservative Dalzel remained sympathetic to the class into which he was born. Nobody was surprised when he hired as his assistant a poverty-stricken youth from Berwickshire, working as a gardener. In 1806, George Dunbar (1774–1851) succeeded Dalzel in the chair, a post which he was to hold for nearly half a century, but he remained fascinated by plants and was an enthusiastic member of the Caledonian Horticultural Society. Dunbar could never have entered the university without the kind financial support of a neighbouring landowner and, after graduation, he only survived as a classicist by working as tutor in the family of Lord Provost Fettes. Dunbar was retiring, and avoided public life and politics, but he was also hardworking and productive. His admirable A Concise General History of the Early Grecian States (1824) consists of 112 fluently written pages covering literature and philosophy, as well as history.49 Its surprises include high praise of Aristotelian ethics (which were then out of fashion) and the hope that more people would study them.50 He could be describing his own career when applauding the Athenian democracy, which ‘possessed this advantage above all others, that it gave free access to every man, however mean his birth or moderate his fortune, to rise by the force of his talents to the highest situation in the state’.51 He also published an impressive set of exercises in Greek syntax and idioms which he perfected by practising them out on his own students and publishing revised editions according to his direct pedagogical experience.52 He believed passionately that study of Greek helped in the appreciation of literature in any language; like his predecessor and mentor Dalzel, he used poetry in English extensively in his teaching.53

Both Dalzel and Dunbar must have been keenly aware of Alexander Murray (1775–1813), the sickly son of an impoverished Galloway shepherd, whose childhood was spent in a room adjacent to the four moorland cattle which constituted his father’s ‘entire wealth’,54 yet who became Professor of Oriental Languages at their university. It was quickly apparent that Murray wasn’t to follow in his father’s footsteps; his eyesight was so poor that he couldn’t see the flock he was charged to herd.55 (Figure 14.4) After just a few months of formal schooling in rural Galloway, Murray embarked on his astounding programme of self-education in the late 1780s before his precocity was spotted by his parish Minister, and local patrons clubbed together to support his formal education at school; he responded by translating some lectures by German scholars on Roman authors, which he failed to get published, but in the course of visiting publishers in Dumfries in 1794, he received friendly advice from Robert Burns.56 His tuition at Edinburgh University, which he attended from the age of 18, was paid for by the institution in consideration of his outstanding performance in the entrance examination. especially his command of Homer, Horace, the Hebrew psalms and French.57 Lord Cockburn remembered him as a fellow-student, ‘a little shivering creature, gentle, studious, timid, and reserved’.58 By this time he already knew French, Latin, Hebrew, Greek and German, and had somehow picked up a smattering of Arabic, Abyssinian, Welsh and Anglo-Saxon. He was regarded as having an ‘almost miraculous or supernatural genius for languages’.59 After graduation, he entered the Church of Scotland and served in the parish of Urr.

As a youth he had written poetry, including ‘a fictious and satirical narrative of the life of Homer’, whom he ‘represented as a beggar’ and a ‘Battle of the Flies’, imitating Homer’s Battle of the Frogs and Mice.60 He read prolifically, including L’Estrange’s Josephus, Plutarch’s Lives and Robert Burns.61 Murray supported himself in his teens and as an undergraduate by teaching children of isolated communities, like his own, ‘the three Rs’ as a tutor, and teaching himself Hebrew, Greek, Latin and French.62 He borrowed and bought (when cheap enough) whatever books he could lay his hands on. He received, for example, from a farmer in Glentrool, a copy of Plutarch‘s Lives and a bilingual edition (Greek and Latin) of Homer’s Iliad from a lead miner at Palnure. He purchased a stout Latin Dictionary (1s 6d) from an old man in Minnigaff, and was gifted a Hebrew lexicon by a distant cousin.63

In his autobiographical writing, Murray reflected on a time when his 12-year-old self got hold of a copy of Thomas Salmon’s Geographical and Historical Grammar. This book contained the Lord’s Prayer in several languages. He recalled how much he had enjoyed and benefited from poring over those translations as a boy.64 It is perhaps no wonder, considering the odd conglomeration of obscure and arcane texts at his disposal, that on growing up Murray should fix his attention on the acquisition and comparison of languages. By the end of his life it is reported that he knew most (if not all) of the European languages, ancient, modern and numerous Oriental languages. His reputation became international. Despite his liberal views on religious tolerance and universal education,65 when it came to class politics, like Dalzel, he was regarded by the conservative establishment as unimpeachably apolitical. In 1810 he was asked by the Marquis Wellesley, then Foreign Secretary, to translate a letter from the Ras of Abyssinia to the Prince Regent. On this account Wellesley’s successor, Castlereagh himself, wrote a letter recommending that Murray be appointed to the Chair of Oriental Languages at Edinburgh in 1812.66

In the same year, Murray completed work on his magnum opus, History of the European Languages: Researches into the Affinities of the Teutonic, Greek, Celtic, Slavonic, and Indian Nations. He finished the book one year before his early death, and four years before the German philologist Franz Bopp (regarded as the founding father of Indo-European Studies) published his influential comparative grammar.67 As early as 1808, Murray had provocatively written that ‘Greek and Latin are only dialects of a language much more simple, regular, and ancient which forms the basis of almost all the tongues of Europe and … of Sanskrit itself’.68 But Murray’s book did not see print before 1823, and so his pioneering contribution to Comparative Linguistics has been somewhat overlooked. But the scale of the two 19th-century monuments erected to his memory, one near his birthplace on the A712 between Newton Stewart and New Galloway, and the other in Edinburgh’s Greyfriars Churchyard, reveals the respect that his outstanding intellectual gifts had won.69

Joseph Wright

The most prodigious British working-class classically trained scholar born in the 19th century was indisputably Joseph Wright. Born in Idle, Bradford, in 1855 to desperately poor parents, he spent some of his childhood in a Clayton workhouse. When his father, a weaver and iron quarryman, left his mother, Joseph started work as a donkey driver at the age of six at Woodend quarry, Windhill, near his home in Thackley. His job entailed leading a donkey-cart to and from the smithy for maintenance, from 7 a.m. until 5 p.m. When seven he started work indoors as a ‘doffer’ in the spinning department of Sir Titus Salt’s mill at Saltaire, although he was under the legal age. Doffing means replacing full bobbins on the machines with empty ones, for which he was paid 3s. 6d. a week. He attended the factory school half-time, but had to leave it early all the time to make a full-time living, since his feckless father died leaving Joseph, his brothers and mother in dire straits. At the age of 13, unable to read or write, he moved to Stephen Wildman’s mill at Bingley, where he was eventually promoted to wool-sorter, earning between £1 and 30s. a week (Figure 14.5). It was there, in 1870, that he determined to learn to read so he could follow the accounts of the Franco-Prussian war in the newspaper.70

He began with Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and the Bible, and attended a night school for working lads run by John Murgatroyd, a Wesleyan schoolmaster. He also bought the fortnightly Cassell’s Popular Educator and started teaching himself languages: French, German and Latin from Cassell’s Latin Grammar.71 He attended lectures at the Mechanics Institute in Bradford and ran evening classes, charging local youths just 2d. a week. He saved £40 and spent it on a trip to Germany, where, after walking from Antwerp to Heidelberg University, he studied German and Maths for 11 weeks, until his money ran out.

On return he gave up mill work altogether, became a full-time teacher, taught himself Greek (which he found inspirational) and in 1882 passed the intermediate exam towards the London BA degree. Feeling intellectually equipped, he returned to Heidelberg, where Professor Hermann Osthoff encouraged him to specialise in philology. To finance his studies, he taught Maths until he achieved his PhD degree three years later. He had gone from illiteracy to a doctorate in 15 years by dogged effort. His thesis was entitled ‘The qualitative and quantitative changes in the Indo-Germanic vowel system in Greek’. He then moved to the University of Leipzig, and worked for a Heidelberg publisher, overseeing the production of 30 scholarly books. The pioneering philologist Karl Brugmann then asked him to make an English translation of his Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der indo-germanischen Sprachen, and it was published in 1888.

By bypassing the problem that he had no qualifications from Oxford and Cambridge, and coming back from Germany with a reputation for brilliance and association with the most cutting-edge philological methods, he was welcomed to the British academic community by Max Müller, the German who had held the Oxford Chair of Comparative Philology between 1868 and 1875. Wright made the leap into an academic post when, with Müller’s support, he was appointed lecturer to the Association for the Higher Education of Women in 1888, teaching German, Historical Greek Grammar, Historical Latin Grammar and Greek Dialects at Oxford University. But his background and fascination with the speech of the north of England led him to specialise at this point in Germanic and Old English dialects, and he also lectured in German at the Taylor Institution. In 1901 Wright, the ragged boy from the Yorkshire quarry, was appointed Professor of Comparative Philology.

His great achievement was the six-volume English Dialect Dictionary, which preserves thousands of now-obsolete usages, and The English Dialect Grammar (1905). He was awarded Honorary Membership of the Royal Flemish Academy, the Utrecht Society, the Royal Society of Letters of Lund and the Modern Language Association of America. He continued to criticise Oxford University for the mediocrity of its research in comparison with the efforts expended on teaching privileged undergraduates. He told the Asquith commission on Oxford and Cambridge (1919–1922) that ‘far too many of the administrative affairs of the University are in the hands of men whose minds have lost their elasticity’.72

According to his wife Elizabeth Mary Wright’s biography, Wright insisted

His work ethic and instinct for self-betterment came from his mother Sarah Ann, a committed lifelong Primitive Methodist, who, when shown the grand buildings of All Souls College at Oxford, retorted, ‘Ee, but it ’ould mak a grand Co-op!’74 As a young woman from a much more privileged background whom he met when she was studying at Lady Margaret Hall, his wife also recalled a rare occasion on which he had rebuked her. She had facetiously complained that doing philology, and consulting big dictionaries, required excessive ‘manual labour.’ Wright quietly pointed out that ‘manual labour’ meant physical work, for example with a wheelbarrow.75 In adulthood he was always regarded as a prodigy and the subject of countless newspaper articles called ‘From donkey-boy to Professor’ or ‘Mill-boy’s rise to fame’.76 But the really

Wright’s meteoric rise is the exception that proves the rule. He was the Jude who did not remain obscure. He would never have risen from the workhouse and mill to the top branch of the academic tree without intelligence and moral qualities. But equally necessary were the availability of tuition at the Wesleyan night school and the Mechanics Institute, encouragement and patronage when it mattered, and the serendipity that a German scholar unrestricted by British academics’ preconceptions about the proper cursus honorum for a professional scholar happened to hold the Oxford Comparative Philology chair at the right time.

All five ‘underdog classicists’ studied in this chapter enjoyed luck as well as good contacts. In the case of only one of them—Porson—did his class position at birth take him far left of the centre of the political spectrum. But all except Murray, who was silent on the topic, retained pride in their humble origins and were not afraid to say so. This is impressive, if only because it was not until the mid-20th century that university education in Classics was to become even a remote possibility for a wider cross-section of the population.