A. Frass expelled from trunk by larva of the banded ash clearwing. DAVID SHETLAR

INSECTS ASSOCIATED WITH LARGE BRANCHES AND THE TRUNK OF TREES AND SHRUBS

CLEARWING BORERS

Clearwing borers (Sesiidae family) are moderate-sized, day-flying moths that have larvae that develop as borers, primarily in trees and shrubs. Appearance of the adults often mimics wasps or bees, and large areas of the forewings may lack scales, hence the name “clearwing.” Larvae are usually pale cream-colored and found in the tunnels they gouge in trunks and stems. The presence along the abdomen of 5 pairs of small prolegs, each ending in a semicircular pattern of small hooks, can differentiate clearwing borers from borer larvae that are beetles (e.g., roundheaded borers, flatheaded borers).

Several clearwing borers develop below ground, feeding within the crown area or larger roots. Often referred to as “crown borers,” these species are discussed in chapter 6, on insects associated with roots. Others develop in canes or small diameter branches.

ASH/LILAC BORER (Podosesia syringae)1

HOSTS Most ash species, particularly green and white ash, and common lilac. Privet is another reported host. Lilac/ash borer is another common name variant for this species.

DAMAGE Larvae create rough gouging wounds under the bark and may riddle wood to a depth of about 2 inches. Injuries are concentrated in the lower 12 feet of the trunk and larger branches. Gnarled swellings form at areas of repeated attack, and sucker growth often increases. On smaller diameter branches common on lilac and privet, larval injuries may girdle and kill main stems. On lilac, older stems are preferred over young stems.

DISTRIBUTION Native to North America, ash/lilac borer has extended its range to include most areas where ash and common lilac are grown.

APPEARANCE Adults are brown and black moths that superficially resemble paper wasps in both size and color. The larvae are creamy white grubs with a small dark head. Prolegs on the abdomen are highly reduced, but small hooklike crochets are present at the tip of the prolegs, which allows separation from the roundheaded borers also associated with ash (page 444).

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Ash/lilac borer spends the winter as a partially grown larva in tunnels under the bark. It resumes feeding and larval development in early spring, pupating just under a thin cover of bark. Adult emergence may begin by early April during warm springs but is usually later and may extend for several weeks with cool, overcast weather. Warm temperatures (above 60° F) and sunny conditions appear critical for adult emergence, which takes place in morning hours. Frequently the old pupal skin is only partially extruded from the emergence hole and remains attached to the tree until it weathers away. Adults are active for about 4–6 weeks after initial emergence, and females subsequently lay eggs on bark, typically near wounds or bark cracks. Eggs hatch in about 1½ weeks. Larvae tunnel into the cambium and phloem and may move an inch or more into the trunk, making irregular vertical galleries.

1 Lepidoptera: Sesiidae

B. Adult of the banded ash clearwing. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Ash/lilac borer larva exposed from under bark. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Ash/lilac borer larva in twig. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Damage produced at base of trunk by Ash/lilac borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Mating pair of Ash/lilac borers. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Pupal case of Ash/lilac borer following adult emergence from trunk. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Ash/lilac borer male responding to pheromone lure. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

OTHER CLEARWING BORERS ASSOCIATED WITH TRUNKS AND BRANCHES

BANDED ASH CLEARWING (Podosesia aureocincta) is a closely related species found in scattered areas of the eastern U.S. It is physically very similar in appearance to ash/lilac borer, differing in having two distinct bands on the abdomen. Banded ash clearwing produces similar feeding injuries but has a different life history, with adults emerging in late summer.

The LESSER PEACHTREE BORER (Synanthedon pictipes)1 is associated with Prunus spp. and can be a serious pest of stone fruit trees. It is more common on older trees and will occur as a borer in areas of the tree that are aboveground, including some of the larger scaffold limbs. (This is in contrast to PEACHTREE BORER (S. exitiosa), which concentrates injuries at the base of the trunk and roots; it is discussed in more detail in chapter 6.) Lesser peachtree borer is present east of the Rocky Mountains. The DOGWOOD BORER (S. scitula)1 is a common species east of the Great Plains but is recorded from the Pacific Northwest and Colorado. It develops under the bark of a wide range of woody trees, including dogwood, pecan, oak, plum, and apple. It is particularly damaging to maple, beech, and grafted apple, where it usually attacks the burr knot tissue that forms at the graft union. Burr knots of apple, hawthorn, and pear are also the site of injury by larvae of the APPLE BARK BORER (S. pyri). On maples the MAPLE CALLUS BORER (S. acerni) repeatedly attacks wound sites, producing an area of progressively enlarging callus tissue.

Two Synanthedon species develop in the lower trunks of various species of Viburnum, including cranberry-bush. The VIBURNUM BORER (S. viburni) is known primarily from the Midwest; the LESSER VIBURNUM BORER (S. latifera) is broadly distributed across the eastern U.S. as well as Alberta. Rhododenron and, less commonly, mountain laurel host the RHODODENDRON BORER (S. rhododendri). Conifers are hosts of other species. In the Pacific States and British Columbia the SEQUOIA PITCH MOTH (S. sequoiae) produces conspicuous pitch masses at its wound sites on the trunks of pines, particularly Monterey pine. In the eastern states similar injury to white, Scotch, and mugho pines as well as to spruce is produced by S. pini, known as the “pitch mass borer.” Pitch mass borer infestations are often mistaken for pitch flows associated with cytospora cankers produced by fungi but can be distinguished by the presence of bits of brown sawdust mixed with the pitch. Pitch mass borer larvae take 2–3 years to complete development.

Larva of the viburnum borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Mating pair of sequoia pitch moths. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

Adults of clearwing borers in the genus Paranthrene are more heavy-bodied and typically resemble large yellowjacket wasps. Larvae of the WESTERN POPLAR CLEARWING (P. robiniae) tunnel into the base of the trunk of poplars and willows and birch, producing conspicuous swellings in smaller trees. It is broadly distributed in the western states. In the southern states east of the Rockies, similar injury to poplars and willows is produced by the COTTONWOOD CLEARWING BORER (P. dollii). Oaks host three other species: P. simulans (RED OAK CLEARWING BORER), P. asilipennis (OAK CLEARWING BORER), and P. pellucida (PIN OAK CLEARWING BORER).

1 Lepidoptera: Sesiidae

B. Pair of dogwood borers. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Adult of the maple callus borer. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Damage by rhododendron borer and pupa. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Adult and pupal skins of the rhododendron borer. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Mating pair of rhododendron borers. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Larva of the western poplar clearwing. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Adult of the western poplar clearwing. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Oozing at wound site produced by oak clearwing. DAVID SHETLAR

J. Adult of an oak clearwing moth. DAVID SHETLAR

CARPENTERWORM (Prionoxystus robiniae)1

HOSTS A wide host range of hardwoods, with oak, elm, ash, and poplar most consistently damaged.

DAMAGE Larvae excavate large cavelike galleries in the sapwood and heartwood of trunks and large branches. Heavily infested trees may break in high winds, and chronically infested trees appear gnarled and misshapen. Larval feeding at the base of large trees allows entry of wood-rotting fungi and carpenter ants. Unlike most other wood borers, the larvae maintain an exterior opening through which they continually expel sawdust-like frass. Large exit holes and flaking of bark occur along damaged areas of trees.

DISTRIBUTION Generally throughout the U.S. and southern Canada.

APPEARANCE The larvae are pinkish-white caterpillars with a dark head and dark brown tubercles on the body. They are large, up to 3 inches long at maturity. Adults are large, heavy-bodied moths, somewhat resembling sphinx moths (page 68). They have grayish forewings, mottled with black.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Carpenterworms winter as larvae in the tunnels produced in infested trees. Pupation occurs in spring, and adult moths appear around May. Often the purplish pupal case remains extruded from the exit hole until it has weathered away. Eggs are laid in clusters in bark crevices or near wounds. After egg hatch the larvae bore directly into the phloem and cambium just under the bark. Early signs are small damp spots on the bark. They later extend tunnels into the sapwood and ultimately the heartwood. Typically they form a central cavity with side tunnels that may extend for several inches. Sawdust is regularly ejected and may conspicuously collect around the base of infested trees. Carpenterworm has a fairly long life cycle, ranging from 1 to 2 years in southern areas and 3 to 4 years in the north.

Carpenterworm larva. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Pupal case of a carpenterworm. DAVID SHETLAR

OTHER CARPENTERWORMS

LEOPARD MOTH (Zeuzera pyrina),1 an apparent introduction from Europe now found in the northeastern states, nearly rivals carpenterworm in size. Young larvae tunnel twigs and small branches but leave when they get too large. External evidence of tunneling is obvious, with wood chips and excrement being pushed to the outside as the larvae feed. A wide range of hardwood trees are hosts. Development requires 2 years to complete. Eggs may be laid from late spring through September.

PECAN CARPENTERWORM (Cossula magnifica)1 occurs in the southern states and appears to complete its life cycle in a single year. Pecan, oak, and hickory are hosts. As the caterpillars feed, they continually push sawdust from feeding sites. Eggs are laid in May and June. Affecting Populus species are two species, POPLAR CA RPENTE RWO R M (Acossus centerensis),1 primarily eastern, and ASPEN CARPENTERWORM (A. populi), more broadly distributed throughout North America.

1 Lepidoptera: Cossidae

B. Carpenterworm larva in tunnel. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Pecan carpenterworm in branch. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Tunnels produced by pecan carpenterworm. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Adult of the pecan carpenterworm. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Adult of Acossus populi, a carpenterworm associated with Populus. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

ZIMMERMAN PINE MOTH (Dioryctria zimmermani)1

HOSTS Pine, particularly Scotch and Austrian pines.

DAMAGE Larvae tunnel under the bark, typically at crotches of branches. Branches may break or die directly from effects of the girdling. Infestations are commonly marked by dead and dying branches, often in the upper half of the tree. External symptoms of injury are popcorn-like pitch masses at the wound site.

DISTRIBUTION Most common in midwestern and Great Lakes States but is present from eastern Colorado to New England, with additional populations now established in many areas of the Pacific States.

APPEARANCE The adults, rarely observed, are midsized moths with gray wings blended with red-brown and marked with zigzag lines. Larvae are generally dirty-white caterpillars, occasionally with some pink or green coloration. They are found under the characteristic popcorn-like masses of sap on trunks and branches.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS The insect overwinters as a very young caterpillar inside a small cocoon (hibernaculum) underneath scales of bark. In mid- to late April and May it again becomes active and tunnels into the tree. Tunneling typically occurs at preexisting wounds or at the junction of the trunk and branch. The larvae feed into July and early August, at which time large amounts of pitch are produced. Prior to pupation they gouge out large areas under the bark, leaving a thin bark flap, and pupate just underneath this. Adult moths are active primarily in late July and August. After mating, female moths lay eggs, often near wounds or previous masses of pitch. Eggs hatch in about a week and the larvae move immediately, without feeding, to protected sites on the bark, where they overwinter in the hibernaculum.

OTHER PYRALID BORERS

Dioryctria ponderosae,1 sometimes known as “pinyon pitch mass borer,” is found in the High Plains and Rocky Mountain regions of the U.S. Pinyon growing in overirrigated sites is most commonly damaged; ponderosa pine is also affected. Irregular wounds under the bark are produced, where a creamy or slightly pinkish ooze mixes with pieces of sawdust and frass. Dioryctria cambiicola is another western species associated with branch tunneling of ponderosa pine. SOUTHERN PINE CONEWORM (D. amatella) is primarily a cone-feeding species but will occasionally damage large branches and even trunks, concentrating at points of previous wounding or fungal infections. Retinia comstockiana (PITCH TWIG MOTH)2 is an eastern species that produces pitch masses in limbs and occasionally trunks of soft pines.

AMERICAN PLUM BORER (Euzophera semifuneralis)1 is a minor pest of fruit trees, occasionally damaging various nut and shade trees. It is associated mostly with stressed trees or existing wounds, including poor pruning cuts. It is found primarily throughout the eastern U.S., but is known as far west as Arizona. Most tunneling occurs in the lower 4 feet of the trunk and almost always originates near previous wounds. The larvae are grayish green to grayish purple and pupate in a silken cocoon, often under bark flaps. PRICKLY PEAR CACTUS MOTH (Cactoblastis cactorum)1 is an introduced species, native to South America, that develops in pads of various prickly pear cacti (Opuntia spp.). Full-grown larvae may exceed 1 inch and are orange-red with dark bands of dots. In addition to feeding injuries produced by the insects, decay organisms invade damaged plants, and collectively these injuries can extensively damage and often kill plants. From areas in Florida where this insect was originally discovered, it has since spread as far as Louisiana and South Carolina.

1 Lepidoptera: Pyralidae

2 Lepidoptera: Tortricidae

A. Dorsal, side and ventral views of Zimmerman pine moth larvae. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

B. Pitch mass produced by Zimmerman pine moth. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Larva of Zimmerman pine moth exposed from pitch mass. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Adult Zimmerman pine moth. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Young larva of a Zimmerman pine moth in overwintering hibernaculum. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Pinyon pitch mass borer exposed from pitch mass. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Oozing from wounds produced by pinyon pitch mass borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Pitch mass produced by pitch twig moth. DAVID SHETLAR

I. Larva of the American plum borer. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM

J. Larva of the prickly pear cactus moth. SUSAN ELLIS, USDA APHIS PPQ, BUGWOOD.ORG

K. Damage produced by prickly pear cactus moth. SUSAN ELLIS, USDA APHIS PPQ, BUGWOOD.ORG

METALLIC WOOD BORERS/FLATHEADED BORERS

The METALLIC WOOD BORERS (Buprestidae family) are elongate, slightly flattened beetles with a metallic sheen. Larvae are known as FLATHEADED BORERS because the first segment of the thorax (prothorax) is often greatly widened and flattened. Legs are absent and the larvae chew tunnels under bark or in wood. Characteristic tunnels produced by most species are zigzag and filled with tightly packed, fine sawdust excrement. Most of the nearly 700 North American species limit attacks to areas of trees and shrubs that have been injured or attacked by fungal cankers or that are in advanced decline or even recently dead. However, a considerable range exists among flatheaded borers in the degree of attack on trees, with some species capable of killing trees in fair to good health.

BRONZE BIRCH BORER (Agrilus anxius)1

HOSTS Birch; European white birch and Jacquemonti birch are particularly susceptible.

DAMAGE Larvae develop by tunneling the cambium layer, under the bark. Girdling injuries first cause limb dieback, with thinning of the crown an early symptom of infestation. Trees are frequently killed following sustained infestation. Birch grown in suboptimal sites, especially where periodic drought stress may occur, are most commonly infested.

DISTRIBUTION Throughout the range of birch in southern Canada and the northern half of the U.S. Most recently the range has extended to the Pacific Northwest.

APPEARANCE The adults are elongate, somewhat flattened beetles from ⅜ to ½ inch long. Overall coloration is olive black with coppery reflections. The elongate larvae are creamy white with the first thoracic segment enlarged and flattened in a manner typical of flathead borers.

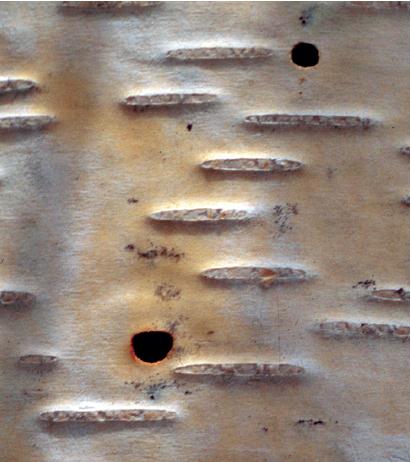

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Adults emerge in late May or early June, cutting a D-shaped opening through the bark. They feed on leaves for 1–2 weeks before eggs mature. Females lay eggs in bark crevices, around curls of bark, and in other protected sites, primarily on the unshaded sides of trunks and branches. During the initial phases of attack, most egg-laying is concentrated in the upper crown on branches less than 1 inch in diameter. Larger branches and ultimately the trunk are attacked as infestations progress. Eggs hatch in about 2 weeks, and the larvae tunnel into the cambium where they spend most of their lives, rarely moving into the xylem. Larval galleries often have a zigzag pattern and are packed with fine sawdust frass. Trees that overgrow these wounds with callous tissue may show evidence of tunneling as raised lumps or ridges, externally visible on bark. Mature larvae overwinter and pupate early in the spring. There is usually one generation per year; 2 years may be required in northern areas to complete the life cycle.

1 Coleoptera: Buprestidae

B. Larva of the bronze birch borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Raised areas of bark indicating wound response by tree to bronze birch borer damage. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Tracks under bark made by developing larvae of bronze birch borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. D-shaped exit hole (lower) produced by bronze birch borer. The circular hole above was produced by a parasitic wasp that attacks bronze birch borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Birch tree in decline from bronze birch borer injuries. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

EMERALD ASH BORER (Agrilus planipennis)1

HOSTS Ash (Fraxinus). On rare occasion it has been observed to attack white fringetree (Chioanthus).

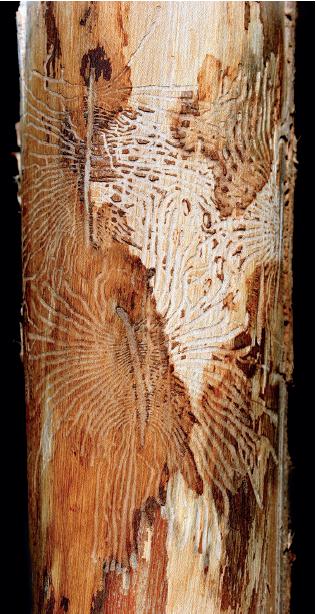

DAMAGE The larvae of emerald ash borer develop under the bark of trees, creating zigzag tunnels through the cambium. Cumulative injuries cause a progressive dieback that initially involves upper limbs but ultimately moves into the trunks. Typically trees are killed within 5 years after they are first colonized.

DISTRIBUTION The first North American detection of emerald ash borer was in 2002 in Detroit. By 2016 this insect was found in most states east of the Mississippi, two Canadian provinces, and two western states (Colorado, Texas). The rapid spread of this insect over wide areas has been largely through the human-assisted movement of infested ash firewood. Once introduced into a location, local dispersal occurs from the flight of adults during late spring and early summer.

APPEARANCE Adults are metallic green beetles, approximately ½ inch long. The larvae are flatheaded borers that make meandering tunnels through the cambium, under the bark. Adults emerge from trees through D-shaped exit holes in the bark.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Winter is spent as a larva within tunnels under the bark and pupation occurs in mid-spring. Adults can be expected to begin to emerge in late May, about the time black locust (Robinia) is in full bloom. Initially they feed on the foliage and, about 2 weeks later, after mating, females begin to lay eggs on the surface of trunks and branches. About 100 eggs may be laid on the trunk or larger limbs, usually at points of rough bark and in cracks of the bark, with most egg laying completed by early July.

Eggs hatch about 2 weeks after being laid, and the larvae bore into the plant where they feed on the sapwood. As they feed and develop the larvae extend their mines under the bark, the size of the tunnels gradually widening as the insect grows. Fine sawdust frass packs these galleries. Larval feeding continues until the larva is mature or until weather becomes too cold for development. Growth is resumed in spring when they complete their development. Normally, one generation is produced annually. Development may be slowed in more vigorous trees in early stages of infestation and in cooler areas some larvae that develop from eggs laid late in the season have been observed to require a second season to mature.

A. Emerald ash borer mating pair. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Emerald ash borer resting on leaf. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Emerald ash borer with wings opened. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Extensive larval tunneling by emerald ash borer. ERIC R. DAY, VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Emerald ash borer larva. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Emerald ash borer adult next to exit hole. DAVID SHETLAR

Approximately 25 species of Agrilus1 occur in North America. Adults are fairly small (⅓–⅝ inch) elongate beetles and a metallic bronze, green, or blue color. Larvae damage plants by making zigzag or spiraling tunnels under the bark. The life cycle is completed in a single year under normal conditions, with the nearly full-grown larva as the overwintering stage. Several limit injuries to canes or small diameter branches; these are discussed on page 348.

TWOLINED CHESTNUT BORER (Agrilus bilineatus), which develops in oak and chestnut, is particularly damaging to trees previously stressed by defoliation by gypsy moth or other causes. It is widely distributed over much of the eastern half of North America, south to Georgia. Adults emerge from trees in early June and intersperse feeding on leaves of the host and other hardwoods with egg-laying and mating. Adults are bluish black with a pale, rather indistinct stripe running the length of each wing cover. Closely related A. carapini attacks hornbeam, especially European hornbeams. GAMBEL OAK BORER (A. quercicola) occasionally moves in outbreak numbers from native stands of Gambel oak into landscape plantings of other oak species in parts of the southern Rocky Mountain region.

GOLDSPOTTED OAK BORER (Agrilus coaxalis) has recently emerged as a seriously damaging borer affecting coast live oak and California black oak. This insect is thought to be native to areas of southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico, where it was formerly a minor species of secondary pest importance. First detected in southern California in 2004, it has proved to be much more damaging to oaks in this area of recent range expansion, with effects compounded by chronic drought. Another native of Mexico that has expanded its range into Texas is the SOAPBERRY BORER (A. prionurus), which has caused heavy losses to western soapberry greater than 2 inches diameter.

HONEYLOCUST BORER (Agrilus difficilis) has become increasingly important with the extensive planting of its host, honeylocust, as a common street tree. Tunneling is usually restricted to larger branches and the trunk and almost always concentrated in areas of the tree affected by fungal cankers or wounds. It can girdle and kill recently transplanted trees. Honeylocust borer is known from New Jersey to Michigan, south to Georgia, and west to Texas and Colorado. Adults are metallic black with greenish or purplish tints. Adult beetles emerge over an extended time and have been observed from May through September.

Several other Agrilus can be common in shade trees that are in decline or damaged by wounds or fungal pathogens. Poplar, cottonwood, and aspen are hosts for BRONZE POPLAR BORER (Agrilus granulatus liragus), GRANULATE POPLAR BORER (A. g. granulatus), and WESTERN POPLAR AGRILUS (A. g. populi), found in northern, southern, and western North America, respectively. COMMON WILLOW AGRILUS (A. politus) is found in branches of maple and willow throughout North America. SINUATE PEARTREE BORER (A. sinuatus) is a European species now established in parts of the Mid-Atlantic States, where it damages pear.

1 Coleoptera: Buprestidae

B. Larva of a twolined chestnut borer. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Gambel oak borer emerging from tree trunk. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Goldspotted oak borer. MIKE LEWIS, CENTER FOR INVASIVE SPECIES RESEARCH, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Honeylocust borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Larval tunneling produced by bronze poplar borer. DAVID LEATHERMAN

G. Exit holes produced by honeylocust borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

FLATHEADED APPLETREE BORER (Chrysobothris femorata)1

HOSTS A wide range of food plants, including most deciduous fruit, forest, and shade trees and shrubs. Maple and apple are among the common hosts.

DAMAGE Larvae tunnel under the bark of trunks and larger branches, producing broad galleries tightly packed with fine sawdust frass. Areas of bark where injury has occurred often appear darkened, somewhat sunken, and may later split above the injury. On young trees, tunneling may girdle and kill the plant; tunnels are more restricted in area on established trees. Injuries are concentrated on the sunny side and most common on trees suffering sunscald, wounds, or drought stress. Areas of a graft union are particularly favored sites.

DISTRIBUTION Throughout the U.S. and southern Canada but common in the eastern and central states.

APPEARANCE Adult wood borers are dark metallic olive gray to brown, about ½ inch long. Larvae are pale yellow, legless, with an enlarged prothorax.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Winter is spent as larvae under the bark. They complete development the following spring, cut a chamber into the sapwood, and pupate. Adults may begin emerging by mid-spring, but peak activity is from late May through June. The females may be observed searching the sun-exposed sides of trunks of host trees. Eggs are laid singly in bark cracks or near existing injuries, and over the course of a month about 100 eggs may be laid. Eggs hatch within 8–16 days, and the larvae chew through the bottom of the egg and begin to tunnel into the tree. Larval development can be rapid and gallery formation extensive in low-vigor trees. Development is retarded (and tunneling more restricted) in trees of high vigor. The larvae continue to feed for several months, becoming dormant during the cold season. There is one generation per year.

RELATED SPECIES

The flatheaded appletree borer is part of a group of about 12 species in the “Chrysobothris femorata species complex”; these are very difficult to distinguish using external features, but they have differences in host range. A great many of the host records attributed to the flatheaded appletree borer could involve one or more of these other species.

PACIFIC FLATHEADED BORER (Chrysobothris mali) predominates west of the Rockies, flatheaded appletree borer to the east. Biology of the two species are similar. Pacific flatheaded borer is damaging mostly to newly planted trees and shrubs and those damaged by sunscald.

1 Coleoptera: Buprestidae

B. Larva of the flatheaded appletree borer. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Damage to sycamore produced by flatheaded appletree borer. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Tunneling of ash limb produced by flatheaded appletree borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Larvae of Pacific flatheaded borer. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

F. Exit holes produced by flatheaded appletree borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Pupa of Pacific flatheaded borer. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

H. Damage to the lower trunk caused by larval tunneling of Pacific flatheaded borer. ROBIN ROSETTA, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

I. Adult Pacific flatheaded borer. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

LONGHORNED BEETLES/ROUNDHEADED BORERS

The longhorned beetle family (Cerambycidae) includes some of the most visually striking beetles. Most are fairly large, and the most massive of all North American insects are found in this group. Color can be variable, with some species dully colored brown or gray and others brightly colored. Very long antennae, sometimes exceeding the body length, are characteristic of most species. Larvae, known as roundheaded borers, produce tunnels that are oval to round in cross section, with tunneling by some species concentrated in the sapwood, while others prefer the heartwood. Legs of roundheaded borers are highly reduced, and the body is relatively uniformly cylindrical, although slightly constricted at most segments. (Roundheaded borers are often similar in body form to clearwing moth larvae, but the moth larvae can be distinguished by short prolegs on the abdomen tipped with small hooks.) More than 900 species are known from North America, but very few seriously damage living trees. Most are associated only with nearly dead or recently killed trees and shrubs.

A few of the roundheaded borers develop in the crown area at the base of the plant and in larger roots; these species are discussed in chapter 6. A few smaller species restrict feeding to small-diameter branches or canes and are discussed in chapter 4.

LOCUST BORER (Megacyllene robiniae)1

HOSTS Black locust.

DAMAGE Larvae develop in trunks, causing deep tunneling that can riddle the plant and cause serious structural weakening.

DISTRIBUTION Expanding. Its range currently includes much of North America, excluding some Pacific States and southern Florida. Locust borer is common in black locust stands.

APPEARANCE The adult is a colorful, generally black beetle marked with yellow cross bands on the thorax and W-shaped bands on the wing covers. It is about ¾ inch in length with antennae nearly as long as the body. The larvae, about 1 inch long when fully grown, are robust, cream-colored, legless grubs with a brown head.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Adults are active in late summer and early fall, considerably later than most longhorned beetles. At this time they are commonly seen feeding on the pollen of goldenrod and other yellow flowers. Concurrently, eggs are deposited in cracks and crevices in the bark of host trees. Larvae hatch in late fall, bore into bark, and construct small hibernation cells for overwintering. They resume activity in the spring and tunnel extensively through heartwood. The larvae mature in the latter part of July. There is one generation per year.

RELATED SPECIES

Some very attractive Megacyllene species commonly develop in recently killed trees. PAINTED HICKORY BORER (M. caryae) occurs throughout the eastern U.S. and is associated with various nut trees, black locust, locust, mulberry, and ash. This beetle often emerges from firewood during winter and spring months, when it is often mistaken for the locust borer. Acacia and mesquite host MESQUITE BORER (M. antennatus) in the southwestern states. Although adults may be observed visiting flowers and emerging from firewood or recently cut lumber, they are not damaging to healthy trees.

B. External evidence of locust borer damage. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Locust borer. DAVID LEATHERMAN

D. Locust borer adults on goldenrod. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Painted hickory borer. DAVID SHETLAR

POPLAR BORER (Saperda calcarata)1

HOSTS Primarily aspen, but cottonwood and poplar are also hosts

DAMAGE Larvae develop under the bark and tunnel the sapwood, girdling trees. Early stages of attack are indicated by moist areas on the bark, often with some associated sawdust. Chronically infested trees exhibit a black varnishlike stain on the bark below points of borer attack. Stringy sawdust is pushed out of holes in the bark by the developing larvae and may pile around the base of trees. Branches and trunks may break off in high winds and trees may be invaded by wood rot. Wound sites also develop as rough growths that may split the bark.

Attacks are generally restricted to large-diameter, overmature trees. Trees most affected are in direct sunlight and generally suffering from some growing stresses (e.g., drought) related to the site.

DISTRIBUTION Poplar borer is a very widely distributed species in most of North America.

APPEARANCE Adults are generally gray beetles, about 1¼ inches long, with a central yellow stripe on the thorax and some black and yellow stippling marks on the wing covers. Larvae are large, yellowish, round-headed grubs, about 1⅜ inches long when mature and found only within their tunnels.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Adults emerge from trees beginning in May and June in southern areas; June and July in northern sites. After emerging from the tree they first feed on the leaves and young shoots of their host for about 2 weeks. The females then begin to lay eggs, which they deposit in niches they chew into the bark of the trunk.

Larvae first feed in the bark and later bore into the sapwood, where they tunnel upward, producing a gallery that may extend about 1 foot in length. Unlike most borers, throughout their period of feeding they maintain an opening to the outside, through which they push the boring dust. Pupation occurs in spring, within a chamber cut just beneath the bark. The poplar borer has an extended life cycle that normally takes two years to complete in southern areas and may be considerably longer in cooler climates.

Poplar borer adult. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

RELATED SPECIES

POPLAR-GALL SAPERDA (Saperda inornata) induces swellings on the twigs of aspen, poplar, and willow. ELM BORER (S. tridentata) develops in dead or weakened American elm, sometimes causing dieback of individual limbs. LINDEN BORER (S. vestia) is sometimes an important pest of linden, particularly little-leaf linden, in the Midwest. ALDER BORER (S. obliqua) develops in alder and birch in the northern U.S. and Canada.

Larvae of the ROUNDHEADED APPLETREE BORER (Saperda candida) develop in trees and shrubs of the rose family, including apple, pear, quince, cotoneaster, hawthorn, mountain-ash, serviceberry, and crabapple. Larvae tunnel the trunks at the base of trees and they are particularly destructive to young apple trees. Adults are present from late April through June, depending on location, and the life cycle often extends for 2 years. Roundheaded appletree borer occurs east of the Mississippi River, north of the hill areas of Georgia to Alabama.

A. Life stages and injury of poplar borer. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Poplar borer larvae. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Sawdust and ooze produced wound site of poplar borer larval injury. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Linden borer. PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES–FORESTRY, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Elm borer. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Roundheaded appletree borer. DAWN DAILEY O’BRIEN, CORNELL UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Larva of roundheaded appletree borer. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

H. Injury produced by poplar gall saperda. USDA FOREST SERVICE–NORTH CENTRAL RESEARCH STATION, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Pupa of elm borer. DAVID SHETLAR

OTHER LONGHORNED BEETLES COMMONLY FOUND IN TREES AND SHRUBS

REDHEADED ASH BORER (Neoclytus acuminatus)1 develops in ash, hackberry, several fruit trees, and other hardwoods. Most attacks occur on dying or recently killed trees, and they are common on firewood. Larval feeding can reduce the sapwood to a fine powder, and large oval-shaped holes may riddle the heartwood. Occasionally there is boring into twigs and branches. The adult beetles have a narrow brown body with a reddish head and thorax. They are about ⅝ inch long and have wing covers marked with four yellow transverse bands and long spindly legs. Redheaded ash borer is found in much of the continent east of the Rocky Mountains. BANDED ASH BORER (N. caprea) is generally similar in appearance and habits. It is marked with yellow stripes on the wing covers and slightly larger than redheaded ash borer. Biology is similar. N. muricatulus is associated with spruce and other conifers.

EUCALYPTUS LONGHORNED BORER (Phoracantha semipunctata)1 became established in California around 1984 and is now found attacking many eucalyptus species in the southern half of the state. Adults may lay eggs in small batches, and larvae originally feed just under the bark, often producing oozing sap that produces dark streaks down the trunk. Older larvae penetrate the cambium, and tunnels may ultimately extend several feet. A second, related species, P. recurva, has more recently become established in southern California and may prove more damaging. These longhorned beetles are capable of producing 2 or 3 generations annually.

ASIAN LONGHORNED BEETLE (Anoplophora glabripennis)1 has been the object of considerable attention and concern since it was discovered in the New York City and Chicago areas in the late 1990s. Maple and poplar are preferred hosts, but a wide variety of hardwood trees are potential hosts. The larvae tunnel extensively in the trunk and branches, resulting in dieback and structural weakening. The adult, sometimes known as “starry sky beetle,” is a large (1–1½ inches), coal-black beetle, often with steel-blue tones, bright white markings, and banded antennae. The species is native to Japan, Korea, and eastern China.

Asian longhorned beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

POLE BORER (Parandra brunnea),1 also known as aberrant wood borer, tunnels the heartwood of many hardwoods including willow, maple, elm, and poplar. It is usually associated with dead areas of wood but causes extensive riddling that can structurally weaken plants. As its name suggests, it is sometimes a problem in telephone poles and structural lumber. It is “aberrant” in appearance, lacking the long antennae characteristic of other longhorned beetles and possessing prominent jaws that make it appear somewhat like a predator. Pole borer is one of the very few wood borers capable of reproducing without emerging from the trunk.

B. Larva of redheaded ash borer. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Banded ash borer. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Eucalyptus borers. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM

E. Damage produced by eucalyptus borers. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Egg niche chewed into bark by Asian longhorned beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

G. First-instar larva of Asian longhorned beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

H. Larvae of Asian longhorned beetle. STEVEN KATOVICH, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. External symptoms of infestation by Asian longhorned beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

J. Pole borer showing range of size of adults. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

K. Riddling of trunk by pole borer larvae. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

L. Pole borer larva. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Species in the genus Callidium1 develop in dead, dying, and seriously stressed conifers. Larvae sculpt tunnels just under the bark and often pack them with granulate frass. Boring activity is also commonly observed as the larvae expel sawdust from wood piles. BLACKHORNED PINE BORER (C. antennatum) commonly infests dead pines and sometimes those recently transplanted in poor sites. It is common in the Rocky Mountain region, throughout the southern states, and in most of the eastern U.S. and Canada. A closely related species is BLACKHORNED JUNIPER BORER (C. texanum), which occurs in juniper. Adults of both species are shiny black or blue-black longhorned beetles.

Blackhorned pine borer. STEVEN VALLEY, OREGON DEPARTMENT WOF AGRICULTURE, BUGWOOD.ORG

PINE SAWYERS (Monochamus spp.)1 are widespread in North America, developing in recently dead and severely stressed pine, spruce, fir, and Douglas-fir. Adults are large beetles (about 1 inch long), black to brownish gray with white speckling, and have extremely long antennae one to three times the body length. Larvae bore extensively in sapwood and heartwood of dying and recently killed trees. Adults cause minor injury by feeding on needles and shoot bark. In the Midwest, pine sawyers are the primary vectors of PINE WILT NEMATODE (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus), which can produce pine wilt disease in susceptible pines; non-native pines (e.g., Scotch pine, Austrian pine) are most susceptible to this disease. The nematode is introduced into feeding wounds of twigs made by the adult and physically carried from tree to tree on the body of the beetles. This twig feeding may also cause flagging of damaged branches from girdling wounds. Common species include WHITESPOTTED SAWYER (M. scutellatus), SPOTTED PINE SAWYER (M. clamator), and SOUTHERN PINE SAWYER (M. titillator).

Larvae of CACTUS LONGHORN (Moneilema armatum)1 tunnel the pads of various cacti in the genera Opuntia and Cylindropuntia. They survive winter in a pupal cell they construct during late summer and early fall around the base of the cactus. Transformation to the pupal stage occurs in spring, and adults emerge in late spring and early summer. Adult beetles feed at night, typically eating young cactus pads or oozing sap. After mating, the females glue eggs to the cactus pad. The young larvae attempt to tunnel into the cactus, causing the plant to ooze sap at the wound. The larvae first feed in this ooze, later entering the plant. They feed throughout the summer and early fall. One generation is usually produced per year, but some of the later larvae may not emerge until the second season. Several other species of Moneilema occur in the southwestern U.S., all restricted to various cacti. M. annulatum, M. appressum, and M. semipunctatum generally resemble cactus longhorn but are somewhat smaller.

The ASH AND PRIVET BORER (Tylonotus bimaculatus)1 can develop in many hardwoods but is most damaging to ash and privet. Adults are present from May through August and lay eggs under bark scales. At egg hatch the larvae bore into the trunk and initially feed in the phloem tissues just under the bark, but they tunnel more deeply and extensively as they get older. Larger limbs of ash are usually attacked, but advanced infestations can move into the trunk. Injury to privet is typically concentrated at the base of the plant. Damage is most often associated with drought-stressed and over-aged plants, particularly in shelterbelt plantings. The ash and privet borer occurs over a wide area east of the Rockies but is most often observed in the states and provinces of the High Plains.

1 Coleoptera: Cerambycidae

B. Branch tunneling produced by larvae of blackhorned pine borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Spotted pine sawyer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Whitespotted pine sawyer. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Southern pine sawyer. NATASHA WRIGHT, COOK’S PEST CONTROL, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Larva of a pine sawyer. DAVID LEATHERMAN

G. Tunneling produced by southern pine sawyer. Smaller tunnels are produced by bark beetles. W. H. BENNETT, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Cactus longhorn. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. External evidence of larval tunneling by cactus longhorn. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

J. Ash and privet borer. DAVID SHETLAR

POPLAR AND WILLOW BORER (Cryptorhynchus lapathe)1

HOSTS Willow and, rarely, poplar

DAMAGE Larvae tunnel into the lower trunk of trees. Infested trees may become malformed because of excessive sucker growth. Young willows may have bulblike swellings from borer attack and may break easily because of borer weakening.

DISTRIBUTION An introduced species now broadly distributed throughout southern Canada and the northern U.S.

APPEARANCE Larvae are cream-colored, legless, C-shaped grubs about ¼ inch long. At points of feeding, large amounts of moist sawdust are pushed from the entry holes. The adults are chunky snout weevils, about ⅜ inch long, and rough-surfaced. They are primarily black except for the hind third of the wing covers, which are gray, somewhat resembling a bird dropping.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Poplar and willow borer spends the winter as a partially grown larva in the sapwood. In the spring, the larvae grow and continue boring, pushing large amounts of fibrous frass through exit holes. Larvae pupate under the bark, beginning in May. Adults may be present from late May through mid-July. Eggs are deposited in small slits in the bark. There is 1 generation per year.

OTHER TRUNK-BORING WEEVILS

AGAVE WEEVIL (Scyphophorus acupunctatus)1 can be a serious pest of agave and yucca in the southernwestern states and Florida. Adults make feeding punctures in young leaves. Most damage is produced by larval tunneling, which occurs primarily at the base of the flowering stalk, but it can also kill the growing point. Secondary infections with rotting organisms commonly follow agave weevil damage, sometimes causing plants to collapse and die. Agave weevil is a large (ca. ½–¾inch) black snout beetle. Larvae are creamy white, legless, and may be ¾ inch when fully grown. The life cycle can be completed in less than 2 months, and up to 4 or 5 generations may be produced annually in more southern areas. A closely related species found in southern California is YUCCA WEEVIL (S. yuccae).

PALMETTO WEEVIL (Rhynchophorus cruentatus)1 is the largest North America weevil and present in many southern states from South Carolina to Texas. Adults may exceed 1 inch in length and have highly variable coloration, ranging from completely black to nearly all red. Adults are usually observed in late spring and early summer. The larvae develop as destructive borers of cabbage palm, occasionally damaging saw palmettos and some other palms. Infestations are often lethal as the larvae extensively tunnel the trunk and may kill the growing point. Serious rots usually develop around wounded areas. Adults usually lay eggs near existing wounds. Emergence holes made by the exiting adult may be the diameter of a quarter. Multiple generations can occur, with the life cycle taking about 3 months to complete under optimal conditions.

RED PALM WEEVIL (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) is considered the most damaging insect pest of palms worldwide. Recently it has been found established in an area of southern California. Adults chew pits in the trunk, often near the base of fronds, and the larvae develop as borers within the upper trunk. Extensive tunneling is produced by the larvae that can cause the tops of plants to be killed. Canary Island date palm is one of the more susceptible species and widely grown in the area where this insect has been found.

1 Coleoptera: Curculionidae

B. Pupa and tunneling damage of poplar and willow borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Poplar and willow borer adult. DAVID LEATHERMAN

D. Agave weevil adults and larvae. STEPHEN H. BROWN, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

E. Agave weevil larva. LYLE BUSS, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

F. Tunneling of the base of agave by agave weevil larvae. STEPHEN H. BROWN, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

G. Adult yucca weevil. JENNIFER C. GIRON DUQUE, UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Palmetto weevils. DOUG CALDWELL, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

I. Palmetto weevil larvae. LYLE BUSS, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

J. Adult, larva and pupa of red palm weevil. CHRISTINA HODDLE, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA-RIVERSIDE, BUGWOOD.ORG

K. Larvae and damage by red palm weevil larva. CHRISTINA HODDLE, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA-RIVERSIDE, BUGWOOD.ORG

The horntails (Siricidae family) are large, thick-bodied wasps that develop as wood borers in recently killed and dying trees. Females are stingless but possess a prominent ovipositor used to insert eggs under bark. All horntails have a mutualistic association with wood-rotting fungi that are introduced during egg-laying and help provide food for the grublike young.

PIGEON TREMEX (Tremex columba)1

HOSTS Many hardwood trees, including maple, beech, hickory, elm, oak, apple, pear, sycamore, and hackberry. Maple and beech are preferred.

DAMAGE Larvae develop as wood borers, creating meandering tunnels that can increase susceptibility to wind breakage; however, damage is confined to dead or dying wood. Adults inject wood-rotting fungi into trees which contributes to tree declines and structural weakening.

DISTRIBUTION Throughout the U.S. and southern Canada, west to the Rockies. Isolated populations are reported from Arizona and southern California.

APPEARANCE Pigeon tremex is a large (1½–2 inches) thick-bodied wasp. Females have a spikelike, dark brown ovipositor. Males, which are smaller, lack the projection. Adults are generally brown and yellowish, with patterning varying among different races throughout the range.

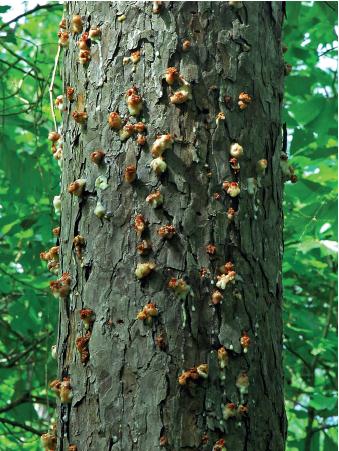

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Adults are most commonly present in late summer, searching and probing recently killed and declining trees for egg-laying sites. As they probe trees, they also introduce a white rot fungus, Cerrina (= Daedalea) unicolor, which rots and softens the wood for the developing larvae. Larvae feed for the next 8–9 months on the wood and fungi, creating tunnels that run through the heartwood. When full grown they create a pupal chamber just under the bark. The emerging adults cut through the bark, leaving a perfectly round exit hole. There is one generation per year over much of the range; the life cycle may take 2 years to complete in northern areas.

OTHER HORNTAILS

Several other horntails occur in North America that develop in conifers. Most abundant and widespread are Sirex species,1 the “sirex woodwasps.” These are blue-black wasps most often associated with pines that are in advanced decline or have recently been cut or killed. All carry white rot fungi, which the female introduces into trees through her ovipositor. Five species are native to North America, and a European species (Sirex noctilio) has recently become established in areas of the Northeast. Five species of Urocerus,1 which develop in recently killed fir and pine, also occur in North America.

Uroceras gigas. DAVID LEATHERMAN

1 Hymenoptera: Siricidae

B. Pigeon tremex male. ! DAVID SHETLAR

C. Pigeon tremex. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Larvae of pigeon tremex. WILLIAM HANTSBARGER, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

E. Circular exit holes produced by pigeon tremex. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Blue horntail, Sirex cyaneus. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Sirex noctilio female. DAVID LANCE, USDA APHIS PPQ, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Sirex noctilio male. DAVID LANCE, USDA APHIS PPQ, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Larva of Sirex noctilio. DENNIS HAUGEN, BUGWOOD.ORG

J. Sirex noctilio adult at exit hole. DAVID LANCE, USDA APHIS PPQ, BUGWOOD.ORG

Bark beetles (Scolytinae subfamily within the weevil family Curculionidae) are fairly small beetles (ca.  –¼ inch) that usually develop feeding on the cambium under the bark of trees. Adult beetles first cut distinctive galleries in which they mate and lay eggs. The legless, grublike larvae tunnel outward from these egg galleries.

–¼ inch) that usually develop feeding on the cambium under the bark of trees. Adult beetles first cut distinctive galleries in which they mate and lay eggs. The legless, grublike larvae tunnel outward from these egg galleries.

Feeding by the insects under the bark can girdle the tree, although most beetles limit attack to damaged limbs or trees that are stressed or in decline; newly transplanted trees are particularly susceptible to attack. However, many bark beetles are associated with fungi that can also produce diseases in trees. These include fungi in the genera Ophiostoma and Leptographium involved in Dutch elm disease and blue stain of conifers.

Bark beetles that limit development to small branches and twigs are discussed in chapter 4.

SHOTHOLE BORER (Scolytus rugulosus)1

HOSTS Fruit trees (particularly Prunus spp.) and a few other hardwoods such as mountain-ash, English laurel, hawthorn, and in rare cases, elm. Most infestations involve overmature, damaged, or diseased plum and cherry.

DAMAGE Shothole borer is the most common bark beetle affecting fruit trees. Larvae develop under the bark, producing typical girdling wounds that can weaken and sometimes kill the plant beyond the damaged area. Oozing gum often occurs on Prunus species where beetles enter the wood to lay eggs. When the adult beetles emerge through the bark, they chew small exit holes, the most commonly observed evidence of shothole borer activity.

DISTRIBUTION An accidentally introduced species now found in temperate areas throughout North America.

APPEARANCE Adults are small (1/10 inch) gray-black beetles.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Shothole borer spends the winter as a grublike larva under the bark or as a pupa in chambers cut into the sapwood. Adults begin to emerge and become active in late April or May but can subsequently be found throughout the growing season. After mating, the females seek out wounded or diseased trees and chew out a 1- to 2-inch-long egg gallery, generally parallel to the grain. Eggs are laid in little niches along the gallery, and larvae subsequently feed under the bark. Adults exit through the bark, leaving a characteristic exiting shothole. Two to three generations may occur, depending on climate, although these are indistinct and egg-laying may occur through much of the growing season.

RELATED SPECIES

HICKORY BARK BEETLE (Scolytus quadrispinosus)1 attacks hickory, pecan, butternut, and walnut throughout much of the eastern U.S. and southeastern Canada. It is particularly damaging in southern areas of its distribution, where it is occasionally a serious forest pest. Some defoliation and leaf wilting may be present as newly emerged adults feed on twigs and leaf petioles. Egg-laying is limited to weakened trees. There is one generation per year in northern areas and two in the south.

A. Shothole borer. NATASHA WRIGHT, COOK’S PEST CONTROL, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Shothole borer tunneling at base of twig. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

C. Exit holes produced by shothole borer. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Larval tunneling by shothole borer. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Shothole borer larva. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Egg gallery and larval tunnels produced by hickory bark beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Hickory bark beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

SMALLER EUROPEAN ELM BARK BEETLE (Scolytus multistriatus)1

HOSTS Elm.

DAMAGE This is the primary insect involved in transmission of the fungus that produces Dutch elm disease (Ophiostoma novo-ulmi). Larvae develop under the bark and can cause girdling injuries but usually restrict attacks to injured limbs or dying trees. There is little damage in the absence of the fungus.

DISTRIBUTION Most of the U.S. where elm is grown, except in some far northern areas.

APPEARANCE This beetle is generally dark and about ⅛ inch long with reddish-brown to reddish-black wing covers. Its posterior end is concave and has a small projection, or spine, typical of the genus Scolytus.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Smaller European elm bark beetles overwinter in the larval stage, in galleries under the bark. Larvae mature in the spring and pupate. Adult beetles typically emerge around mid-May, although earlier emergence may occur. Beetles emerging from trees infected with Dutch elm disease can become contaminated with spores of O. novo-ulmi.

Transmission of Dutch elm disease by beetles occurs when the beetles subsequently fly to healthy elm trees, feed at the crotches of 2- to 3-year-old twigs, and subsequently contaminate the feeding wounds with spores of the fungal pathogen. This period, known as maturation feeding, may last for several weeks, during which eggs within the female mature. Adults then seek out diseased and weakened trees and construct egg galleries that run parallel to the wood grain. The larvae develop over the course of about 2 months, and adults emerge in mid- to late summer. Adults pass through a second round of twig-feeding and egg-laying, with the subsequent larval generation overwintering.

OTHER ELM BARK BEETLES

The BANDED ELM BARK BEETLE (Scolytus shevyrewi)1 is of Asian origin, first discovered in the U.S. in 2003, and has subsequently spread widely through much of western North America. It has a very similar life history to the smaller European elm bark beetle but typically emerges a few weeks earlier. In some areas of the Rocky Mountain region this insect seems to have largely eliminated S. multistriatus by competitive displacement.

NATIVE ELM BARK BEETLE (Hylurgopinus rufipes)1 is an important vector of Dutch elm disease in areas of the upper Midwest, northeastern U.S., and adjacent areas of southern Canada where cold temperatures limit the smaller European elm bark beetle. Many spend winter as adults that construct special chambers in the lower trunk. Egg galleries run across the grain.

A. Smaller European elm bark beetle tunneling into twig. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

B. Vascular discoloration characteristic of infection with Dutch elm disease. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Galleries produced by smaller European elm bark beetle. DAVID LEATHERMAN

D. Larvae of the smaller European elm bark beetle. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

E. Banded elm bark beetles feeding on twig. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Banded elm bark beetle larvae in tunnels. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Galleries produced by banded elm bark beetle. DAVID LEATHERMAN

H. Native elm bark beetle. JAVIER MERCADO, BARK BEETLE GENERA OF THE U.S., USDA APHIS ITP, BUGWOOD.ORG

Three Hylesinus species1 may damage green and white ash. EASTERN ASH BARK BEETLE (H. aculeatus) and CRIDDLE’S BARK BEETLE (H. criddlei) are generally distributed east of the Great Plains. WESTERN ASH BARK BEETLE (H. californicus) is the most damaging species and found throughout much of the western U.S. and Prairie provinces.

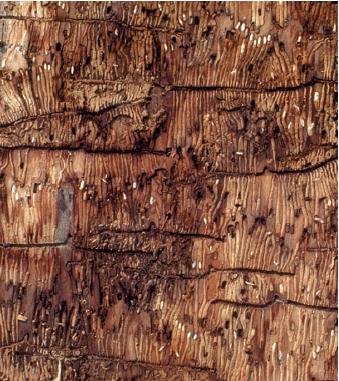

Ash bark beetles may infest almost the entire tree, from finger-diameter branches to the main trunk. Injured limbs and heavily shaded branches in the interior of the tree are most commonly attacked. Adult beetles cut egg galleries under the bark across the grain, and these typically have two arms with a central chamber. Small ventilation holes appear above the egg galleries. These injuries and subsequent tunneling by the larvae girdle branches. The tunnels are almost invariably colonized by fungi that stain the wood a rich brown color around the feeding sites.

Ash bark beetles overwinter either as late-instar larvae under the bark or as adults in niches cut into the green bark of the outer trunk and become active in early to mid-spring. The larvae feed under the bark, often extensively scoring into the sapwood. Those developing from spring eggs become full grown in late spring or early summer and pupate in the tunnels. Adults emerge from the branch and feed on green wood, causing little damage. There is evidence that a partial second generation is sometimes produced. These may not complete development and overwinter as larvae. Bark beetles that have reached the adult stage move to the trunks at the end of the season to cut hibernation chambers in which they winter.

SOUTHERN PINE BEETLE AND RELATIVES (Dendroctonus spp.)1

Bark beetles in the genus Dendroctonus can be very damaging to conifers. They are typically small (ca. % inch) cylindrical beetles, dark brown or black. Thirteen species occur in North America, with many restricted to forest settings. Most Dendroctonus bark beetles can overcome tree defenses by mass attacks that are coordinated with chemical cues known as aggregation pheromones. Girdling of the tree results from egg galleries produced by the adults and larval tunnels under the bark. Many species are also associated with transmitting fungi that produce blue stain diseases that may contribute to tree death. Trees successfully attacked by Dendroctonus bark beetles typically show a fading of needle color, progressing to a reddish-brown color. These symptoms develop within a year after beetles begin to lay eggs and are almost always followed by the death of the tree.

SOUTHERN PINE BEETLE (D. frontalis) is the most important forest insect in the southeastern U.S., with Kentucky being part of its northern range. It is most commonly found on shortleaf, loblolly, Virginia, and pitch pines and is usually restricted to trees older than 15 years but with a trunk diameter less than 6 inches. Adult beetles usually enter the trunk 6–20 feet above ground and chew curved or S-shaped egg galleries. Multiple generations are produced, and a single generation may be completed in as little as a month during favorable warm periods. Adults may be active much of the time from spring through fall.

Views of southern pine beetle adult. ERICH G. VALLERY, USDA FOREST SERVICE–SRS-4552, BUGWOOD.ORG

A. Eastern ash bark beetle, Hylesinus aculeatus. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Ash bark beetle in egg gallery. DAVID LEATHERMAN

C. Ash bark beetle galleries in branch. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Ventilation holes above egg gallery of ash bark beetles in branch. DAVID LEATHERMAN

E. Hylesinus criddlei. JAVIER MERCADO, BARK BEETLE GENERA OF THE U.S., USDA APHIS ITP, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Galleries in trunk produced by eastern ash bark beetle. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Exit holes produced by ash bark beetles. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Pitch tubes produced in response to attacks by southern pine beetle. ERICH G. VALLERY, USDA FOREST SERVICE–SRS-4552, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Galleries produced by southern pine beetle. RONALD F. BILLINGS, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

J. Exit holes produced by southern pine beetle. RONALD F. BILLINGS, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

MOUNTAIN PINE BEETLE (D. ponderosae) is the most important bark beetle of western forests, particularly concentrated in the Rocky Mountains and Black Hills. It attacks primarily ponderosa, lodgepole, and limber pine; Scotch pine is occasionally damaged. Mature trees more than 8 inches in diameter are most susceptible to attack. Mountain pine beetle has a 1-year life cycle, with adults active during early summer.

Two species of turpentine beetles are found in North America. RED TURPENTINE BEETLE (D. valens) is the most widely distributed, occurring throughout the U.S. and southern Canada, excluding the southeastern and Gulf states, where BLACK TURPENTINE BEETLE (D. tenebrans) is found. Both species have similar habits and are among the largest bark beetles, with adults being ¼–⅜ inch long. They can develop in large-diameter pines and are particularly common in trees scorched near the base by fire or injured during construction. Turpentine beetle attacks are characteristically confined to the lower few feet of the trunk. Inner-bark feeding differs from that of most Dendroctonus, with larvae feeding as a group and excavating an irregular, round-edged patch under the bark.

In mountainous areas of the western states, forest species sometimes become serious pests of landscape plants. SPRUCE BEETLE (D. rufipennis) historically has had several widespread and sustained outbreaks on Colorado blue and Engelmann spruce. Adults overwinter in small chambers cut into the base of the trunk and fly during June and early July. Larvae take almost 2 years to complete development.

IPS BEETLES

Ips beetles (Ips spp.),1 sometimes known as ENGRAVERS, develop in most pines and spruce. At least one of the approximately two dozen Ips species that occur in North America is likely to be found wherever these hosts are found.

Ips beetles are less aggressive than Dendroctonus bark beetles, usually limiting attacks to trees that are seriously stressed by root injury, drought, disease, or defoliation. Attacks are less commonly lethal to trees and may be limited to large branches or, most commonly, the tops of trees. Trees killed by Ips beetles show the uniform needle discoloration and death of Dendroctonus bark beetles. Blue stain fungi often, but not always, are introduced with Ips beetles.

Adults are of typical size for bark beetles, ⅛–¼ inch long, and reddish brown to black. Characteristic is a pronounced cavity at the rear end lined with 3–6 pairs of toothlike spines.

Ips beetles have multiple generations, and adults may be active whenever temperatures allow. Unlike many other bark beetles, Ips beetles are polygamous, with the initial tunneling by the male cutting a cavity under the bark (nuptial chamber). Attracted females subsequently produce characteristic patterns of egg galleries in the shape of Y or H. The egg galleries are free of sawdust, which is pushed out of the entrance hole by the scooped hind end of the beetles as they work. A yellowish- or reddish-brown boring dust in bark crevices or around the base of trees is indicative of ips beetle activity.

SOME IMPORTANT IPS1 BEETLES OF LANDSCAPE CONIFERS

SPECIES |

HOST |

COMMENTS |

Ips calligraphus |

Pine |

Largest Ips beetle and known as six-spined engraver. Common throughout North America |

Ips pini |

Pine |

Throughout North America and often the most common species affecting pine. Known as pine engraver |

Ips avulus |

Pine |

Smallest Ips beetle and known as small southern pine engraver. Occurs in a broad area of eastern U.S. south of Pennsylvania |

Ips confusus |

Pinyon |

Periodically kills pinyon over large areas |

Ips hunteri |

Spruce |

An important species affecting Colorado blue spruce in Colorado and the southwest Upper portions of tree are typically infested first. Known as the blue spruce engraver. |

B. Egg gallery produced by mountain pine beetle. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Galleries and associated staining produced by mountain pine beetle. WILLIAM M. CIESLA, FOREST HEALTH MANAGEMENT INTERNATIONAL, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Blue stain fungi introduced during attack by mountain pine beetle. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Dead and dying lodgepole pine during mountain pine beetle outbreak. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Red turpentine beetle. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Larval tunneling by red turpentine beetle. DAVID LEATHERMAN

H. Adult of the six-spined ips. NATASHA WRIGHT NATASHA WRIGHT, COOK’S PEST CONTROL, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Adults of the pinyon ips. WILLIAM M. CIESLA, FOREST HEALTH MANAGEMENT INTERNATIONAL, BUGWOOD.ORG

J. Galleries produced by six-spined ips. DAVID LEATHERMAN

K. Sawdust produced by ips beetle tunneling. DAVID LEATHERMAN

L. Top dieback due to infestation of spruce ips. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Ambrosia beetles develop differently from other bark beetles. All tunneling is done by the adult female, which constructs a brood chamber in the sapwood or heartwood of trunks and branches. Small niches are often carved off a central chamber in which the larvae develop. Ambrosia beetles invariably carry into the brood chamber certain fungi (often Ambrosiella spp.) with which they have a mutualistic relationship. The fungi colonize the wood, and the larvae feed on the fungi (the ambrosia); larvae do no further tunneling. Damage by the native species of ambrosia beetles in the genera Trypodendron, Xyleborus, and Xyleborinus1 is usually minimal to living plants, as injuries are typically limited to nearly dead or recently felled trees. However, some introduced species in the genera Xylosandrus, Xyleborus, and Euwallacea1 have significantly greater potential to damage trees and shrubs, particularly when associated with fungi that are pathogenic to host plants. Recent research has indicated that smaller trees in waterlogged soils are most at risk of attack by introduced ambrosia beetles. Apparently, such trees produce alcohols that are attractants for the beetles.

GRANULATE AMBROSIA BEETLE (Xylosandrus crassiusculus)1 tunnels into the sapwood and heartwood of a wide range of trees and shrubs, including various stone fruits (Prunus spp.), pecan, golden-rain tree, sweetgum, persimmon, Shumard oak, beech, Chinese elm, crape myrtle, and magnolia. Because of the site of tunneling, relatively little structural damage is done, but the activities of the beetle allow development of various canker-producing fungi. Subsequent disruption of sap flow by these fungi can seriously damage and sometimes kill plants. Furthermore, affected plants are conspicuous, as wood particles produced by tunneling may project out of the trunk and branches as small sticks, often referred to as “toothpicks.”

Granulate ambrosia beetle is dark reddish brown and about inch long. Since its original introduction into Florida, it has spread throughout much of the southeastern U.S., as far west as Texas. One generation is thought to be produced annually, but adults are present year round, being most actively flying and attacking new plants in March and early April.

BLACK STEM BORER (Xylosandrus germanus) is currently widely distributed through much of the eastern U.S., extending into parts of the Midwest and Texas. It has a wide host range of trees and shrubs, primarily broadleaf plants but also including some conifers. Tunneling causes wilting and dieback, particularly by contributing to the spread of cankers produced by Fusarium fungi. Adults emerge in March in southern areas of the range and in mid-May farther north. The females bore into sapwood, constructing a brood chamber with branching side tunnels. The fungus (Ambrosiella hartigii) is introduced and begins to grow in chambers at this time. Eggs are then laid, and larvae can develop in about 1 month. Pupation occurs in the gallery, as does mating. The males, which cannot fly, do not leave the rearing chamber, but females then disperse to produce new brood chambers. Two generations per year are normally produced.

A. Tunneling of oak by a native Xyleborus ambrosia beetle. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Xyleborus dispar. PEST AND DISEASES IMAGE LIBRARY, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Adult granulate ambrosia beetle in tunnel. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Compacted sawdust extruded from tunnel of a granulate ambrosia beetle. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Larvae and pupae of granulate ambrosia beetle. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Adult of the black stem borer. PEST AND DISEASES IMAGE LIBRARY, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Damage to wood made by tunneling of the black stem borer. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

BLACK TWIG BORER (Xylosandrus compactus) is a tiny (ca.  inch) beetle occurring in the southeastern states. It is considered among the most aggressively damaging of the ambrosia beetles and develops in the twigs of various trees and shrubs, including oak, maple, hickory, magnolia, and willow. Females construct a ½- to 1½-inch tunnel as a brood chamber in the pith or wood of succulent twigs, and numerous females may nest in larger twigs. Pathogenic fungi, including Fusarium solani, are commonly introduced during entry, and twigs usually die beyond the point of the tunneling. Larvae can develop rapidly, with a generation completed in a little more than a month.

inch) beetle occurring in the southeastern states. It is considered among the most aggressively damaging of the ambrosia beetles and develops in the twigs of various trees and shrubs, including oak, maple, hickory, magnolia, and willow. Females construct a ½- to 1½-inch tunnel as a brood chamber in the pith or wood of succulent twigs, and numerous females may nest in larger twigs. Pathogenic fungi, including Fusarium solani, are commonly introduced during entry, and twigs usually die beyond the point of the tunneling. Larvae can develop rapidly, with a generation completed in a little more than a month.

REDBAY AMBROSIA BEETLE (Xyleborus glabratus)1 is an Asian species associated with a fungus (Raffalea lauricola) that can produce very severe injury, often death, of highly susceptible hosts in North America. It has been particularly destructive to native redbay (Persea borbonia) in the southeastern states where it first became established, and there is high concern about its potential to damage avocado.

Xyleborus saxeseni, known variously as the “lesser shothole borer” and “fruit-tree pinhole borer,” is a very common insect associated with many hardwoods, including oak, walnut, peach, maple, and hackberry. Adults tunnel into the trunk and larger limbs of trees in decline or that have been recently felled and, upon entering the tree, create a tunnel directly into the sapwood, typically tunneling about an inch beneath the bark. Fine sawdust produced during the tunneling often accumulates at the entrance.

The larvae develop as a group within the brood chamber, feeding on the ambrosia fungi that grow on the tunnel walls and expanding the chamber as they develop. As the female continues to lay eggs over a period of weeks, a mixture of life stages may be present. The primary injury produced by this insect is cosmetic blemishing of wood, affecting lumber quality. In addition to the pin holes created by tunneling, the area around the tunnels is darkly stained by fungi associated with the beetles.

Anisandrus dispar,1 sometimes known as the “European shothole borer,” is a species that has long been established in North America but is at present particularly commonly encountered in the Pacific Northwest. The primary hosts are maple, ash, and oak. Recently, two Euwallacea species1 sometimes informally known as the “polyphagous shothole borer” and “Kuroshio shothole borer” have become established in parts of southern California. Both are associated with Fusarium fungi that can produce serious limb dieback in host plants and occasionally result in tree death. Highly susceptible hosts include boxelder, castor bean, avocado, English oak, California coast live oak, big leaf maple, silk tree, liquidambar, coral tree, titoki tree, California sycamore, and blue palo verde.

1 Coleoptera: Curculionidae (Scolytinae)

A. Extensive tunneling produced by redbay ambrosia beetle. JAMES JOHNSON, GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Sawdust tube produced by trunk tunneling of the redbay ambrosia beetle. ALBERT (BUD) MAYFIELD, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Adult of the fruit-tree pinhole borer. PEST AND DISEASES IMAGE LIBRARY, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Vascular staining produced by the fungus Raffalea lauricola introduced by the redbay ambrosia beetle. ALBERT (BUD) MAYFIELD, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Adult of Anisandrus dispar. KIRIN ELLIOT, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

F. Adult Anisandrus dispar with eggs. ROBIN ROSETTA, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY