A, B. Grasshoppers (A) and Colorado potato beetles (B) are generalist defoliators. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

INSECTS THAT CHEW ON LEAVES AND NEEDLES

INSECTS IN EIGHT ORDERS (Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera, Orthoptera, Dermaptera, Phasmatodea, Blattodea) along with slugs and snails chew leaves of plants. Most are generalist defoliators, chewing foliage in patterns that are not particularly distinctive. Others create distinctive injuries as they feed, and these can be useful for identifying the insect associated with them. For example, some insects chew small holes in the interior of the leaves, a damage known as shothole or pit feeding. Angular leaf notching, confined along the edge of the leaf of specific plants, can be a very characteristic injury pattern produced by the adults of many weevils, particularly the “root weevils.” Smooth cuts along the edges of leaves are produced by other insects for production of shelters (e.g., waterlily leafcutter), to construct nest cells for rearing young (e.g., leafcutter bees), or as a base material to culture fungi on which they feed (e.g., leafcutter ants).

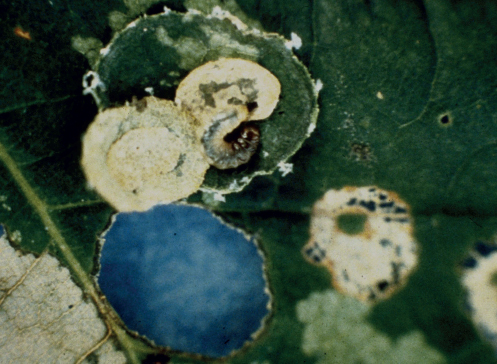

Some avoid the larger veins as they feed, producing skeletonizing injury patterns. Caterpillars of several moths may skeletonize plants, particularly in younger instars. Larvae of some leaf beetles and the Mexican bean beetle skeletonize leaves, as do the slug sawflies. Skeletonizing by adult insects is much less common, but is very characteristic of the Japanese beetle. Skeletonizing of leaves can be very fine (all veins and cross veins remain) or coarse (only the largest veins remain and both leaf surfaces are consumed). Fine skeletonizers may feed only on the upper or lower leaf surface, which can be helpful in diagnosis.

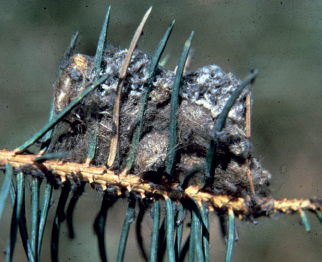

Other leaf-chewing insects may be identifiable by structures they produce to cover their bodies or shelter them at feeding sites. Some construct bags or cases of silk that may be camouflaged with plant parts or fecal pellets (bagworms and some casebearers). Others use leaves—rolled up (leafrollers), folded over (leaffolders), or several leaves tied together (leaftiers and webworms). Still others cut out pieces of leaves that are folded or tied together in such a way as to make a case that is carried around, or they may make tiny cases of silk or excrement (casemakers or casebearers). Finally, several caterpillars and sawflies produce silk to make dense centralized tents in the crotches of branches for resting and shelter (e.g., tent caterpillars) or to create extensive silken shelters that web over the foliage on which they are feeding (e.g., webworms).

C. Flea beetle adults chew small pits in leaves, producing shothole wounds. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Angular notching along the leaf edge is often produced by adult weevils. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. A smooth, semicircular cut along the leaf edge is characteristic of leafcutter bees. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Mexican bean beetle larvae avoid all the larger veins while they feed producing leaf skeletonizing symptoms. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Viburnum leaf beetles produce an irregular skeletonizing of leaves, feeding on many of the smaller veins. DAVID SHETLAR

H. A grape leaffolder, exposed from its leaf fold shelter. DAVID SHETLAR

I. Symptoms produced by a leafroller caterpillar on oak. DAVID SHETLAR

J. Several caterpillars of mimosa webworm typically feed together and construct a small shelter of webbing and leaves. DAVID SHETLAR

K. Tent caterpillars construct large silken structures in the crotches of trees and shrubs. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

Grasshoppers are some of the most familiar of all insects, and more than 550 species occur in North America. Only a small number regularly damage gardens and almost all of these are in the genus Melanoplus.1 Species particularly injurious to plants include:

— TWOSTRIPED GRASSHOPPER (Melanoplus bivittatus)

— DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER (M. differentialis)

— MIGRATORY GRASSHOPPER (M. sanguinipes)

— REDLEGGED GRASSHOPPER (M. femurrubrum)

— DEVASTATING GRASSHOPPER (M. devastator)

HOSTS Although many types of grasshoppers particularly favor grasses, others feed preferentially on broadleaf plants or a mixture of grasses and broadleafs. Although almost all garden plants can be damaged, beans, leafy vegetables, iris, and corn are among the plants more commonly injured by grasshoppers.

DAMAGE Grasshoppers damage plants by chewing. Most feeding occurs on foliage, although immature pods and fruit may also be eaten. Bark from twigs is sometimes gnawed, causing girdling wounds that can produce dieback of branches.

DISTRIBUTION Redlegged grasshopper is found throughout the U.S. and southern Canada but is most common in the upper Midwest. Migratory grasshopper has an almost equally broad range but is absent in extreme southern Texas and Florida. Twostriped grasshopper is found everywhere except the Deep South. Differential grasshopper is present throughout the U.S. except in the extreme northeast, southeast, and northwest. It is most abundant between the Rocky Mountains and Mississippi River. Devastating grasshopper is confined to the Pacific States.

APPEARANCE The largest grasshoppers in this group are the differential and twostriped grasshoppers, with some adults more than 1½ inches long. A dark herringbone pattern on the hind femur characterizes differential grasshopper, although very dark forms are also sometimes produced. Two pale yellow stripes run along the back of the thorax and wings of twostriped grasshopper. Redlegged grasshoppers range from ¾ to 1 inch long with a bright yellow underside and red tibia on the hind leg. Migratory grasshopper is also medium sized, with a blue-green or reddish hind tibia.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS As a generalized life history, Melanoplus grasshoppers spend the winter as eggs, in elongate egg pods containing 20–120 eggs inserted shallowly in soil. The eggs hatch in mid- to late spring, depending on temperature, location of the eggs, and species characteristics. Twostriped grasshopper is a very early hatching species, as some embryonic development occurs the previous season. Egg hatch of migratory grasshopper typically follows about 2–3 weeks later, and differential grasshopper eggs often hatch shortly after this. Redlegged grasshopper eggs hatch in late spring or early summer. In all four species, the period of egg hatch can extend over a considerable period if eggs are laid in scattered sites, or hatch may occur over a short period.

Development of the nymphs typically takes 5–7 weeks, during which time they pass through five or six nymphal instars. Females feed for about 2 weeks before laying eggs. Eggs are laid as pods, often containing 50 or more eggs, and several pods may be produced. Each species has preferences as to where it lays eggs, with some preferring sun-exposed sites with compacted soil. Egg pods are typically inserted into the soil, often around the crown area or roots of plants.

B. Pair of differential grasshoppers. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Migratory grasshopper. SCOTT SCHELL, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING

D. Redlegged grasshopper. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Grasshopper egg pod. DAVID L. KEITH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Clearwinged grasshopper. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Devastating grasshopper. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM.

H. Grasshopper laying eggs. COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES.

Grasshoppers can show migratory behaviors. Nymphs sometimes march considerable distances in bands during outbreaks. Adults are capable of flight and may fly for several miles, often at elevations of several hundred feet above the ground. Modest physical changes may sometimes occur in populations that become more migratory. For example, thinner body size and longer wings are produced by twostriped and migratory grasshoppers that go into the more migratory phase.

Although grasshoppers in the genus Melanoplus are usually the species involved in damage to garden plants, there are some other species that can be regionally damaging or attract attention.

CLEARWINGED GRASSHOPPER (Camnula pellucida)1 has had several historical outbreaks in the Rocky Mountain/High Plains region. It is a fairly common species, found in most of North America except the southeastern states. Adults are medium-sized and yellow to brown with mottled forewings and transparent hindwings. Grasses are favored, and the species can be a severe pest of small grains, but it occasionally damages onions, lettuce, cabbage, and peas in gardens. Clearwinged grasshopper eggs hatch quite early in the season, following a few warm days in early spring, and most eggs hatch over a brief period. During the summer, when eggs are being laid, the females alternately move from feeding sites in fields to egg-laying beds where soil conditions are favorable.

VALLEY GRASSHOPPER (Oedaleonotus enigma)1 is found in semiarid areas of western North America, and is most commonly noted to be damaging in California. Eggs hatch in spring, often in early April in California, and they feed primarily on broadleaf plants, including shrubs. Both long-winged and short-winged (brachypterous) adult forms may be produced, with high temperatures favoring the latter.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER (Dissosteira carolina)1 is a common, large grasshopper sometimes seen hovering over areas of bare ground. The hindwings, exposed in flight, are colorfully marked with black and have a yellow border; however, the overall color of the grasshopper, and of the covering forewings, is tannish to gray brown. Carolina grasshopper feeds on a wide variety of plants but is rarely abundant enough to cause serious damage.

EASTERN LUBBER GRASSHOPPER (Romalea guttata)2 is the largest grasshopper found in North America. Heavy-bodied and reaching a length of 2 to almost 3 inches, it is a colorful insect of variable patterning, primarily black in young stages with more yellow and orange in the adults. The short, nonfunctioning wings are pinkish or reddish. Eastern lubber is found in the southeastern states, from South Carolina to east Texas. It is most abundant in slightly moist habitats where it feeds on a wide range of weedy plants, but it does occasionally invade vegetable and flower gardens. Eggs hatch in March and April. In much of the High Plains and southern Rocky Mountain region, the PLAINS LUBBER (Brachystola magna)2 is present and rivals eastern lubber in size. It feeds primarily on wild sunflower, kochia, hoary vervain, and other rangeland plants, rarely damaging cultivated plants. This species is usually green to brown and also has short wings.

1 Orthoptera: Acrididae

2 Orthoptera: Romaleidae

B. Eastern lubber grasshoppers feeding on crinum lilies. DOUG CALDWELL, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

C. Eastern lubber grasshopper. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Pair of plains lubber grasshoppers. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

FIELD CRICKETS (Gryllus spp.)1

DAMAGE Field crickets eat a wide variety of plant materials. Although rarely damaging to garden plants, they are occasionally associated with injury to seedlings of many plants, including tomatoes and beans. Field crickets are also one of the insects most commonly associated with damage to irrigation tubing. Occasionally field crickets will incidentally enter homes, where their persistent chirping may be considered annoying; chewing damage to fabrics by field cricket has also been reported.

DISTRIBUTION Field crickets are found throughout North America, with 16 species. It is difficult to distinguish most species by physical features; some often separated only by aspects of behavior, including their life cycle and the male’s song. FALL FIELD CRICKET G. pennsylvanicus)1 and SPRING FIELD CRICKET (G. veletis) tend to predominate in most of North America. SOUTHEASTERN FIELD CRICKET (G. rubens), also known as the “eastern trilling cricket,” is restricted to the southeastern states. It is physically identical to TEXAS FIELD CRICKET (G. texensis) which occurs in Texas, Oklahoma, and southern states, sometimes in spectacular swarms attracted to lights.

APPEARANCE Field crickets are predominantly black, often shiny, but may have some brown on the front wing. When fully grown they are about ¾ inch long. Males and females can be easily separated by the presence or absence of the prominent ovipositor, used by the females to lay eggs. Field crickets are also well known among the “singing” insects, producing the familiar trilling chirping noises of the night. Only the males sing, which they do by rubbing special ridged structures (file, scraper) along the edge of the wings. Different songs are used to attract mates, during courtship, and to defend territories from other males.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Field crickets are active at ground level, usually resting under sheltering debris during the day and active at night. Overwintering stages may vary; fall field cricket spends winter as eggs in soil, spring field cricket as nearly full-grown nymphs. Eggs are laid in small groups in slightly damp soil. After egg hatch, nymphs take 2–3 months to develop, during which time they molt eight or nine times. Most field crickets have a single generation per year, but the southeastern and the Texas field cricket have two.

OTHER CRICKETS AND KATYDIDS

The ROBUST GROUND CRICKETS (Allonemobius spp.)1 are a complex of six closely related species distinguishable largely by differences in song, habitat, and minor morphological features. All are varying shades of brown and can be distinguished from field crickets by having long spurs on the hind leg. They are most abundant in grassy areas, including turfgrass areas. Robust field crickets are omnivorous, feeding on dead plant material and fungi, but mostly various low-growing plants, with legumes such as clover and alfalfa preferred. The STRIPED GROUND CRICKET (A. fasciatus) has the widest range, occurring over much of eastern North America, into Canada and the Pacific Northwest. The SOUTHERN GROUND CRICKET (A. socius) is often the most common species in southern states. These crickets can be common in and around yards and fields, but they rarely damage garden plants. Most species have a one-year life cycle and overwinter in the egg stage; the southern ground cricket can have two generations.

TREE CRICKETS (Oecanthus spp.)1 are similar in length to field crickets but more slender-bodied and occur on aboveground areas of plants. Typical species are green or yellow-green; some have dark markings and black appendages. They are most commonly associated with trees and shrubs, particularly tree fruits and caneberries. All have one generation per year, with winter spent in the egg stage.

B. Female field cricket. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Male field cricket. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Field cricket, late-instar nymph. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Striped ground cricket, female. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Striped ground cricket, male. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

G. Blackhorned tree cricket, female. DAVID CAPPAERT

H. Blackhorned tree cricket, male. DAVID CAPPAERT

I. Tree cricket at egg hatch. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

J. Tree cricket oviposition wounds in twig. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Although tree crickets may feed on leaves, they do little damage. Plants are injured primarily during late summer when eggs are laid. Females insert eggs into stems and canes, which may result in rough calloused areas around the wound, increase susceptibility to stem breakage, and allow entry of canker-producing fungi into the plant. One of the common species one may find is the BLACKHORNED TREE CRICKET (O. nigricornis), easily distinguished because adults usually have black legs and dark markings on the head and pronotum. The TWOSPOTTED TREE CRICKET (Neoxabea bipunctata) is very common and is distinctive because of the tan color with two darker spots on the upper surface of the folded wings. NARROWWINGED TREE CRICKET (O. niveus) is another common species.

The SNOWY TREE CRICKET (O. fultoni)1 is a pale green species that occurs over a broad area of the northern U.S. and parts of southern Canada. It is particularly well known because it has been shown that it can be used to determine temperature, as a type of living thermometer., based on its rate of chirping, which varies reliably with temperature in a manner that has been quantified. The formula for determining temperature by chirping rate is known as Dolbear’s Law, after A. E. Dolbear, who first published on the phenomenon in 1897. The formula is T = 40 + N15, where T is temperature (in Fahrenheit) and N is the number of chirps in 15 seconds.

KATYDIDS2 are substantially larger than tree crickets and have a general resemblance to grasshoppers but have much longer antennae and thin jumping hind legs. Most are green, which allows them to blend in well with the foliage of trees and shrubs on which they feed. Both the nymphs and adults chew leaves, rarely causing noticeable injuries. Most katydids lay their flattened eggs along twigs and these can resemble a double row of fish scales.

Katydids are far more commonly heard than seen as the males make calls during evening and night to attract mates. These sounds are produced by stridulation, in a manner similar to crickets, by rubbing special structures of the forewings (the “file” and “scraper”). Perhaps best known is the song of the TRUE KATYDID (Pterophylla camellifolia),2 a loud rasping “katy-did” call. This insect is widely distributed east of the Rocky Mountains, with substantial regional variation in the types of calls it produces. Clicking calls are characteristic of the BROADWINGED KATYDID (Microcentrum rhombifolium),2 also known as the GREATER ANGLE-WING KATYDID, a species that can be found across the U.S. and in parts of southern Canada; the related LESSER ANGLE-WING KATYDID, M. retinerve, is restricted to eastern North America. BUSH KATYDIDS (Scudderia spp.),2 marked by narrower wings, produce various rattling calls. Bush katydids tend to be more commonly encountered in the southern U.S. in gardens where perennials, grasses, and shrubs are used. These have very brightly colored nymphs that draw attention.

CAMEL CRICKETS3 are wingless crickets that possess very long antennae and have a characteristically humped body in profile. Several dozen Ceuthophilus species are native to North America, with some found in very restricted environments, notably caves. Several species can be common in and around yards and gardens—and sometimes within buildings, where they are usually found in more humid areas of the structure. Camel crickets feed at night and have very omnivorous food habits, consuming fungi, dead plant matter, carrion, and dead insects. Living plants are rarely damaged.

An introduced species known as the GREENHOUSE CAMEL CRICKET (Diestrammena asynamora)3 has become widely established in much of eastern North America, and in many areas it is now the most common camel cricket found outdoors and within buildings. This species more often damages living plants and is a particular pest threat within greenhouses.

1 Orthoptera: Gryllidae

2 Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae

3 Orthoptera: Rhaphidophoridae

B. Snowy tree cricket, male. DAVID SHETLAR

C. “True” katydid. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Broadwinged katydid. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Eggs of the broadwinged katydid. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Broadwinged katydid nymph. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Bush katydid, Scudderia sp. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Greenhouse camel cricket. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

I. Camel cricket. DAVID SHETLAR

COMMON (NORTHERN) WALKINGSTICK (Diapheromera femorata)1

HOSTS Oak, black cherry, elm, basswood, and black locust are favored plants. Paper birch, aspen, dogwood, and hickory are occasional hosts.

DAMAGE Nymphs and adults chew leaves. Damage is usually minor, but occasional outbreaks in forests cause significant defoliation.

DISTRIBUTION Over much of the area east of the Great Plains except the most southern states. It is most numerous around the Great Lakes.

APPEARANCE Full-grown adults reach a length of about 3 inches. They are highly variable in color and may be nearly pure green, gray, brown, or mottled.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Eggs of the common walkingstick hatch in late spring from eggs resting on soil. In forests the young nymphs usually feed first on the leaves of low-growing plants, then move to trees as they get older. Adults are present by midsummer, and the females drop their seedlike black eggs indiscriminately until frost. In southern areas of the range, these eggs usually hatch the following spring, but in the northern states and Canada they remain dormant until the second season.

RELATED SPECIES

There are 29 species of walkingsticks in North America, but most are rarely observed. TWOSTRIPED WALKINGSTICK (Anisomorpha buprestoides) is one of the larger North American species, with a body length of about 2½–3 inches, and is marked with 3 longitudinal black stripes. It is found in the Gulf States, where it feeds primarily on oak, although rose, crape myrtle, and other plants are also reported hosts. For defense it can discharge a directed squirt, over a distance of 12 inches or more, of a strong smelling fluid that can be very irritating to eyes and mucous membranes. The NORTHERN TWOSTRIPED WALKINGSTICK, A. ferruginea, is a related, smaller species with more northern range. The most common species in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains States is the PRAIRIE WALKINGSTICK (D. velii), which feeds on various prairie shrubs and grasses, notably big bluestem.

1 Phasmatodea: Heteronemiidae

A. Walkingstick. JAMES SOLOMON, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Walkingstick. DAVID CAPPAERT

C. Prairie walkingstick, mating pair. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Mating pair of Anisomorpha sp. walkingsticks. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

EUROPEAN EARWIG (Forficula auricularia)1

HOSTS European earwig is a true omnivore and feeds on a diet of insects and plant matter. Small, soft-bodied insects such as aphids and insect eggs are important protein sources; these are supplemented with soft plant matter from leaves and flower petals, especially during dry weather. European earwig can be particularly abundant on plants that also provide tight areas for daytime shelter, such as large flowers (e.g., rose, dahlia) and the ear tips of corn.

DAMAGE Adults and nymphs may feed on leaves, flower blossoms, and corn silks. Tender vegetable seedlings may be entirely consumed and soft, ripe fruits such as peaches and nectarines may be tunneled, the earwigs usually entering through the stem end. The habit of Euopean earwig to seek out tight, dark places to spend the day can make it an unwanted presence in many types of harvested fruits, vegetables, and flowers.

DISTRIBUTION As the name implies, European earwig is an introduced species. It has spread rapidly and is now found throughout almost all of North America with the exception of some southern states.

APPEARANCE Adults are approximately ¾ inch long with prominent pincers. The general color is reddish brown, often with bronze tones. Short, pale brown wing covers are present on the thorax. Males have long, bowed pinchers while those of females are fairly straight.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS European earwigs overwinter primarily as adult females. They become active on warm days in late winter, when the females dig small nests beneath rocks, within mulched areas of garden beds, or in other protected sites. A cluster of about 50 eggs is produced and then tended by the mother. After the eggs hatch, typically in late March or April, the mother continues to guard and care for the young earwigs for several weeks until they have molted and are ready to leave the nest. The young then disperse to forage on their own, becoming full grown in about 1 month. Often the mother lays a second, smaller egg mass in May or June. There is only one generation per year, but developing earwigs may be present throughout the growing season because of the double broods of overwintered females. Foraging occurs at night, with movement to dark, sheltered areas during the day. As the season progresses, the earwigs increasingly tend to aggregate in these shelter sites. Although the European earwig has wings, it very rarely, if ever, flies.

OTHER EARWIGS

RINGLEGGED EARWIG (Euborellia annulipes)2 is found primarily in warmer areas but is occasionally found throughout much of the continent. It is appears black with white bands on the legs and is wingless. Like the European earwig it has omnivorous food habits, doing some leaf chewing, but feeds primarily on other arthropods and is often an important biological control of some pest insects. Two generations are produced annually.

Three species of earwigs in the genus Doru1 occur in the southern U.S. They have wings and are marked with tan bands on the area behind the head (pronotum) and front wings. They are predators of caterpillars and other insects.

SHORE EARWIG (Labidura riparia)3 is the largest earwig found in the southern U.S. and Mexico, most commonly in coastal areas. It is also a predator but will occasionally throw up mounds of soil in gardens and low-cut turf. Adults can effectively apply a noticeable pinch with their cerci.

1 Dermaptera: Forficulidae

2 Dermaptera: Carcinophoridae

3 Dermaptera: Labiduridae

B. Female (top) and male (bottom) European earwigs. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

C. European earwig female tending eggs. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Immature European earwig. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. European earwig feeding at night. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Ringlegged earwig. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Doru sp. earwig. RUSS OTTENS, UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Shore earwig. DAVID SHETLAR

Cockroaches are primarily tropical insects, with only about 50 species present in North America, and many are introduced species. Often these introduced species have limited distribution within the region, and some are essentially restricted to living within buildings, including most of the more notorious commensal species that can be serious household pests. Notable household pest cockroaches include the GERMAN COCKROACH (Blattella germanica),1 BROWNBANDED COCKROACH (Supella longipalpa),1 AMERICAN COCKROACH (Periplaneta americana),2 SMOKYBROWN COCKROACH (Periplaneta fulginosa),2 and ORIENTAL COCKROACH (Blatta orientalis).2

Outdoors, cockroaches are usually found under fallen leaves, among woodpiles, under wood shingles, around compost piles, and in other sheltered sites during the day. They forage for food at night, and most cockroaches are omnivores that feed on a wide variety of foods, with decaying plant matter usually making up most of the diet; however, a few species do feed on living plants, particularly soft seedlings, and can be plant pests.

One cockroach that has been reported to cause serious injury to seedling plants in greenhouses is the AUSTRALIAN COCKROACH (Periplaneta australasiae). It closely resembles the American cockroach but is slightly smaller and has the edges of the thorax bordered in yellow. Also common in greenhouses and in atrium plantings can be the SURINAM COCKROACH (Pycnoscelus surinamensis),3 a type of burrowing cockroach that can easily tunnel into the soil and mulch around plants. At night they emerge and may chew on soft parts of plants.

In Hawaii the PACIFIC BEETLE COCKROACH (Diploptera punctata)3 chews on the bark of cypress and juniper, sometimes causing serious damage. MADEIRA COCKROACH (Rhyparobia maderae)3 is a pest of soft fruits (banana, grapes) in tropical areas; it has been periodically introduced on produce, but has been found only in localized areas and is not well established in North America. The GREEN BANANA COCKROACH (Panchlora nivea),3 also known as the “Cuban cockroach,” is another non-native species now well established in the Gulf States. It is a very attractive green color and not considered a pest species, limiting its feeding to dead and decaying plant matter.

A non-native cockroach that may cause more nuanced effects in gardens is the ASIAN COCKROACH (Blattella asahinai). Now well established in much of the southern/southeastern parts of the U.S., it has been shown to be an important predator of insects, notably feeding on eggs of caterpillars. This cockroach is very similar in appearance to the German cockroach, but it differs in habits by rarely entering buildings and is normally found outdoors among fallen leaves and similar debris. The Asian cockroach can also readily fly, unlike its more human-adapted relative, the German cockroach.

The cockroaches that are native to the U.S. are best represented by various WOODS COCKROACHES (Parcoblatta spp.).1 About a dozen species can be found scattered across much of the U.S., inhabiting wooded areas and feeding on decaying plant matter. Adults typically reach a length of ¾ to 1 inch. Females are a bit smaller than males, and their wings do not extend to fully cover the abdomen. Males have fully developed wings. Only rarely do they enter buildings, but males are good fliers and are often attracted to outdoor lights.

1 Blattodea: Ectobiidae

2 Blattodea: Blattidae

3 Blattodea: Blaberidae

B. German cockroach. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Oriental cockroach, various life stages. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Australian cockroach, various life stages. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Surinam cockroach. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Green banana cockroach, Panchlora nivea. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Asian cockroach, nymph. JOHNNY N. DELL, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Pennsylvania wood roach. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

I. Woods cockroach, Parcoblatta virginica. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

IMPORTED CABBAGEWORM (Pieris rapae)1

HOSTS Essentially all cultivated mustard family plants, including cabbage, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, and collards. Many cruciferous weeds are also important host plants.

DAMAGE Larvae chew foliage. Most early feeding occurs on outer leaves, but older larvae tend to feed more intensively on the newer growth and can seriously tunnel the heads of many plants.

DISTRIBUTION Common throughout North America.

APPEARANCE The caterpillars are rather sluggish, velvety green with 5 pairs of distinct prolegs. A faint yellow line runs along the back of older larvae. The adult, often known as the CABBAGE WHITE, has upper wings that are predominantly white, with a slightly dark tip of the forewing. Males have a single black spot on the forewing, whereas females have two such spots. The underside of the wings is yellowish.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS In the northern U.S. and Canada, imported cabbageworms spend winter as pupae among plant debris in the vicinity of previously infested plants. The adults are one of the first butterflies to emerge in spring. After a period of mating and egg maturation, females begin to lay their yellow, bullet-shaped eggs on leaves. The eggs are laid singly, often on the underside of the leaf as the female perches on the leaf edge, and eggs may be produced over the course of about three weeks.

Larvae hatch in 3–5 days and begin to feed on plants, often first remaining on the outer leaves. Later they tunnel into the head. Larvae are full grown in 2–3 weeks. Pupation occurs in the vicinity of the plant. Two to four generations are typically completed in much of the northern area of the range. In the southern U.S., however, breeding can be continual and as many as six to eight generations may occur.

OTHER SULFUR AND WHITE BUTTERFLIES

SOUTHERN CABBAGEWORM (Pontia protodice)1 is found primarily in the southern U.S. but may disperse northward into the Prairie Provinces. Larvae are much more brightly colored than imported cabbageworm, with black spotting and yellow striping. Feeding habits are similar to those of imported cabbageworm, but southern cabbageworm tends to feed more often on buds and flowers. The adult stage is known as the CHECKERED WHITE BUTTERFLY and possesses dark spotting on its white wings. The GREAT SOUTHERN WHITE (Ascia monuste) is a nearly pure white species that is considerably larger than the cabbage butterfly, and larvae may occasionally be found feeding on radish, cabbage, and other Brassicaceae. It is a southern species, most often found in the Gulf States, and ranges into South America. On occasion it may stray into northern areas as far north as Maryland and Colorado.

Imported cabbageworm damage to broccoli. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

ALFALFA CATERPILLAR (Colias eurytheme)1 feeds on legumes, including pea, most clovers, alfalfa, and bean. The caterpillars are dark green with a light line running along each side. Adults are orange-yellow butterflies that sometimes become abundant where alfalfa is grown. Closely related and of similar habit is CLOUDED SULFUR (C. philodice).

1 Lepidoptera: Pieridae

A. Egg of the imported cabbageworm. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Imported cabbageworm at egg hatch. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Late-instar larvae of imported cabbageworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Adult of the imported cabbageworm, the cabbage white. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Mating pair of cabbage white butterflies. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Chrysalis of imported cabbageworm. RUSS OTTENS, UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Larva of the checkered white, the southern cabbageworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Checkered white butterfly. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. Larva of the great southern white, Ascia monuste. ALTON J. SPARKS JR., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

J. Alfalfa caterpillar. JOHN CAPINERA, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

K. Recently emerged adult of the alfalfa caterpillar, next to its chrysalis. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

L. Clouded sulfur. DAVID CAPPAERT, BUGWOOD.ORG

Swallowtails include some of the largest and most striking butterflies found in North America, a welcome addition to most any garden. The caterpillar stages feed on leaves and are also of unusual and interesting appearance, with many having bright warning coloration or large eyespot markings, or are of cryptic appearance resembling bird droppings. Larvae also have the unique habit of being able to extend forked fleshy scent glands (osmeteria) from behind the head when disturbed. These glands also secrete odors that may be distasteful to potential predators.

PARSLEYWORM/BLACK SWALLOWTAIL (Papilio polyxenes)1

HOSTS Dill, parsley, and fennel are common hosts. The caterpillars may also be found on carrot, Queen Anne’s lace, celery, caraway, and other plants in the family Apiaceae. Common rue (Ruta graveolens) is also an occasional host.

DAMAGE The caterpillars develop primarily by chewing on leaves. When flowering structures are present they may clip flower heads and feed on developing seeds.

DISTRIBUTION Primarily east of the Rockies, although occasionally found in southern California and Arizona.

APPEARANCE Adults are known as black swallowtails, large butterflies with a wingspan of 2¼ to 3¼ inches. The primary coloration is shiny black, sometimes with iridescent blue, marked with yellow bands or spots along the edge of the wings.

Young caterpillars, known as parsleyworms, are mottled black and white, resembling bird droppings. Later instars dramatically transform to possess prominent banding of yellow, white, and black. When disturbed they will usually extend a yellow-orange scent gland (osmeterium) from behind the front of the head. LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Parsleyworm spends the winter as a pupa (chrysalis) attached to tree bark, rocks, the sides of buildings, or other protected locations. Adults typically emerge in late May and early June. After mating females will lay eggs over a period of several weeks, laying a series of individual eggs, usually on younger leaves or flowers of their host plants. Males establish territories they will regularly patrol, waiting for receptive females to pass and chasing away males.

Eggs hatch 4–9 days after being laid and the caterpillars feed for about 3–4 weeks, undergoing a series of color changes and patterning as they get older. When full grown, they wander away from the host plant to find a protected spot where they will transform to the pupal stage. The pupa is in the form of a greenish or grayish-brown chrysalis, the colors matching the background to which it is attached. There are typically two generations produced per year in northern areas and three in southern areas. In the early season generations, the adult butterflies emerge from the chrysalis in about two weeks following pupation. In the last generation, the insect remains dormant within the chrysalis and emerges the following year.

B. Parsleyworm with osmeteria everted. SUSAN ELLIS, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Egg of the parsleyworm/black swallowtail. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Early-instar parsleyworm larva. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Middle-instar parsleyworm larva. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Chrysalis of the parsleyworm/black swallowtail. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Parsleyworm preparing to pupate (prepupa). DAVID SHETLAR

H. Black swallowtail, female. JOHN CAPINERA

I. Black swallowtail, male. DAVID SHETLAR

The closely related ANISE SWALLOWTAIL (Papilio zelicaon) develops on fennel and some plants in the citrus family (Rutaceae). It is found primarily west of the Continental Divide, including the southwestern U.S., and its larvae are sometimes known as the CALIFORNIA ORANGEDOG. SHORT-TAILED SWALLOWTAIL (P. brevicauda) occurs in eastern Canada and occasionally damages the foliage of parsnip.

TIGER SWALLOWTAILS are large yellow and black butterflies. In western North America two common species are TWO-TAILED SWALLOWTAIL (Papilio multicaudatus), developing primarily on chokecherry and ash, and WESTERN TIGER SWALLOWTAIL (P. rutulus), associated with willow, cottonwood, and chokecherry. In eastern North America EASTERN TIGER SWALLOWTAIL (P. glaucus) develops on the foliage of various trees, including wild cherry, sweetbay, basswood, tuliptree, birch, ash, cottonwood, mountain-ash, and willow. Young tiger swallowtail caterpillars are mottled black and white and resemble bird droppings. Older caterpillars may be brown or lime green with prominent eyespots. When sufficiently disturbed, these larvae rear up and extrude their forked yellow scent glands, producing an appearance of a rearing snake.

GIANT SWALLOWTAIL (P. cresphontes) is common in much of the southwestern and southeastern U.S., commonly migrating northward. Caterpillars develop on citrus, and the conspicuous caterpillars are sometimes known as orangedogs.

Egg of a two-tailed swallowtail. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Late-instar larva, brown form, of the two-tailed swallowtail. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

1 Lepidoptera: Papilionidae

A. Eastern tiger swallowtail. HERBERT A. “JOE” E. PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Two-tailed swallowtail. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Early-instar larva of the two-tailed swallowtail. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Giant swallowtail. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Late-instar larva, green form, of the two-tailed swallowtail, everting osmeterium. JOHN CAPINERA, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

F. Orangedog, larva of the giant swallowtail. DAVID SHETLAR

Brushfooted butterflies (Nymphalidae family) are a common group of moderately large butterflies. The upper surfaces of the wings are often brightly colored, but the lower surfaces may be more camouflaged. The front pair of legs is greatly reduced. Although many brush-footed butterflies feed at flowers, others visit sap flows, fermenting fruit, and animal dung. Few species ever seriously damage plants in the caterpillar stage.

PAINTED LADY/THISTLE CATERPILLAR (Vanessa cardui)1

HOSTS A wide range of plants, with more than 100 species from several plant families reported. Common hosts include Canada thistle, other thistles, sunflower, Jerusalem artichoke, hollyhock, common mallow, and lupine.

DAMAGE Caterpillars chew foliage, sometimes causing significant defoliation.

DISTRIBUTION Painted lady is one of the most widely distributed butterflies in the world, found on almost every continent. It occurs throughout the U.S. and southern Canada as either a winter resident or seasonal migrant.

APPEARANCE The caterpillar stage, known as thistle caterpillar, is generally black with some lighter flecking and numerous fleshy dark spines. It is almost always associated with a loose silken shelter it constructs among leaves. The adult stage of the insect is known as painted lady. It is generally orange with irregular black and white spotting on the wings.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Painted lady is an annual migrant in much of North America, spending the winter in more southerly areas, including Mexico. In spring, migrations are northward; in fall, to the south. Females lay eggs singly on host plants. Caterpillars produce a shelter of loose webbing by tying leaves together. When abundant, they extensively defoliate plants, and once the food plant is destroyed, the caterpillars migrate. Pupation occurs in a silvery chrysalis, usually some distance from the food plant. Adults emerge about one week after pupation and usually disperse from the area. Several overlapping generations are produced annually, with returning southward migrations observed in late summer.

OTHER BRUSHFOOTED BUTTERFLIES

Three other Vanessa species of butterflies occur commonly over much of North America. The RED ADMIRAL (Vanessa atalanta) is the most distinctively different in appearance, with upper wings having large dark areas and edged with orange stripes and white spots. It can be found throughout the U.S. and southern Canada. Three generations are normally produced in the southern areas, two in much of its North American range, and one generation in the north, where it may not regularly survive winters. Seasonal differences in appearance, with butterflies produced during summer being larger and brighter than those produced in winter. The red admiral is most commonly observed in moist sites, such as near streams, and along edges of woodland. The larvae feed on stinging nettles (Urtica spp.) and false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica).

B. Chrysalis of the painted lady. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Painted lady, side view. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Painted lady larva in thistle. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Larva of the red admiral. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Red admiral. DAVID SHETLAR

The AMERICAN LADY (V. virginiensis) also has a wide distribution that can include much of North America, although it is most common east of the Mississippi. The range of plants used as larval foods is considerably narrower than that of the painted lady, with everlasting types of composites (e.g., pearly everlasting, sweet everlasting, plantain-leaved pussytoes) being the most common hosts. Three or four generations are produced in the southern U.S., although reproduction may be temporarily suspended during midwinter. Survival through winter in areas with freezing winters is unlikely, and the presence of American lady in these areas results from annual migrations from the south. The WEST COAST LADY (V. annabella) has the most restricted distribution, occurring only in western North America. Larvae develop on nettles and various mallows, including hollyhock.

The MONARCH (Danaus plexippus) is one of the most familiar of the North American butterflies, both large in size and brightly patterned with orange and black. The larvae develop on various milkweeds (Asclepias), are colorfully striped with white, black and yellow, and have two pairs of filaments: a pair arising from the thorax and a pair from the tip of the abdomen. Garden plants that commonly support monarch caterpillars include A. tuberosa (butterfly milkweed), A. syriaca (common milkweed), A. incarnata (swamp milkweed), and A. curassavica (tropical milkweed or bloodflower). All these plants contain compounds (cardiac glycosides) that are toxic to mammals and birds, and both the adult and larval stages store these in their body for defense.

The monarch is a migratory species that spends part of the winter in a temporarily dormant state at specific sites where they aggregate. Populations that occur in areas east of the Rocky Mountains migrate to Mexico in autumn and aggregate in forested areas in mountains east of Mexico City. Populations that develop in the Pacific States produce winter aggregations in several different sites of pine forest. Most of these western overwintering aggregation sites are in California, but some monarchs move into western Mexico. The overwintered butterflies resume activity in early spring, laying eggs on newly available host plants on which a new generation develops. Adults of these then disperse northward, where they extensively colonize much of the U.S. and southern Canada.

Also developing on milkweeds is the QUEEN (Danaus gilippus). This is a subtropical and tropical species that can breed year-round in the extreme southern areas of Texas and Florida. Elsewhere it occurs as an incidental summer migrant. The larvae are also brightly patterned but have some bluish coloration and 3 pairs of black filaments, which can distinguish them from monarch caterpillars.

Of remarkably similar appearance to the monarch is the adult of the VICEROY (Limenitis archippus). Larvae of this butterfly develop mostly on willow, and they are generally found throughout North America, particularly in moist sites that support their host plants. The caterpillars and the pupae resemble bird droppings.

A. American lady. JOHNNY N. DELL, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Larva of the American lady. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

C. Western lady. TERRY SPIVERY, USDA-FS, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Monarch. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Larva of the monarch butterfly. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Chrysalis of the monarch butterfly. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Mating pair of monarch butterflies. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Comparison of monarch (left) and viceroy (right) butterflies. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. Larva of the viceroy. HOWARD ENSIGN EVANS

J. Chrysalis of the viceroy butterfly. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

MOURNING CLOAK (Nymphalis antiopa) is a dark purple-black butterfly with a yellowish border on the wing. It is one of the few butterflies that winters in the adult stage and may be observed flying about during warm spells in midwinter. Eggs are laid in spring in masses on aspen, cottonwood, poplar, willow, birch, elm, or hackberry. Larvae, known as SPINY ELM CATERPILLARS, are generally dark colored with purple markings and feed as a group during early instars. Often entire branches are stripped by larval feeding. When full-grown the caterpillars pupate, and the adults that subsequently emerge remain in a reproductively dormant state for the rest of the year. Adults butterflies may periodically feed at flowers, at sap flows, and on rotting fruit through summer and fall, but only a single generation is produced each year.

VARIEGATED FRITILLARY (Euptoieta claudia) produces brightly colored larvae covered with fleshy spines. They feed on pansy, violet, Johnny-jump-up, wild flax, and occasionally sedum, Passiflora, alyssum, and purslane. This species can be common and damaging to gardens and is sometimes known as “pansyworm.” It is primarily a southern species, overwintering as a full-grown larva, but it frequently strays into northern states during summer.

Larva of the variegated fritillary. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

HACKBERRY BUTTERFLY (Asterocampa celtis) and TAWNY EMPEROR (A. clyton) are associated with hackberry and sugarberry throughout the range of these plants. QUESTION-MARK (Polygonia interrogationis) develops on succulent foliage of elm, basswood, and hackberry in the eastern states. Larvae of the COMMON BUCKEYE (Junonia coenia) feed on plantains, snapdragon, and toadflax. GORGONE CHECKERSPOT (Chlosyne gorgone) develops on sunflowers and Lysimachia.

Larva of the question mark butterfly. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASS III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

Larva of the hackberry butterfly. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Larvae of the Gorgone checkerspot. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

1 Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae

B. Larva of the mourning cloak, the spiny elm caterpillar. STEVEN KATOVICH, USDA-FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Variegated fritillary. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Question mark butterfly. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASS III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Adult hackberry butterfly feeding on fluids from a dead raccoon. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Larva of the common buckeye butterfly. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA-ARS, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Common buckeye butterfly. DAVID SHETLAR

H. Gorgone checkerspot. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Hornworms (Sphingidae family) are among the largest caterpillars found in North America. All are marked by having, at least in the first stages, a prominent “horn” on the hind end. More than 120 species occur on the continent, but only a very few (e.g., tobacco hornworm, tomato hornworm, catalpa sphinx) become sufficiently abundant to regularly cause damage to plants. The majority develop on shade trees and shrubs, where damage is rarely noticed.

Adults are strong-flying, heavy-bodied moths known as sphinx moths or hawk moths. The moths feed on nectar from deep-lobed flowers. Those that are active during the day are sometimes known as “hummingbird moths.”

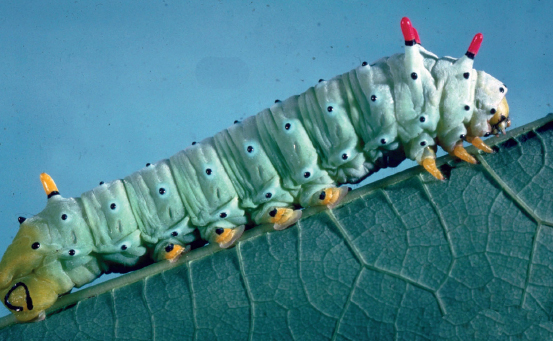

TOMATO HORNWORM/FIVESPOTTED HAWK MOTH (Manduca quinquemaculata)1

TOBACCO HORNWORM/CAROLINA SPHINX (Manduca sexta)1

HOSTS Tomato and tobacco are particularly susceptible to injury. Pepper, potato, and certain nightshade family weeds are also hosts.

DAMAGE Caterpillars chew leaves and can defoliate plants rapidly. Fruits, particularly green fruit, may also be chewed.

DISTRIBUTION Both species are found widely throughout the U.S. and southern Canada. Tobacco hornworm tends to predominate in southern areas and tomato hornworm in the north, but distributions overlap considerably.

APPEARANCE Larvae develop into large caterpillars, with five pairs of prolegs and a flexible “horn” on the last segment. Most are generally green. Seven diagonal white stripes are present along the side of the tobacco hornworm, and the horn is usually red. Tomato hornworm has a series of V-shaped white markings along the sides, and the horn is often black. Less common dark green or even black forms of tomato hornworm may be present. Adults of both are strong-flying, heavy-bodied moths. The forewings may have a span of up to 5 inches and are generally gray or grayish brown with light wavy markings.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Tomato and tobacco hornworms spend the winter months in the pupal stage, within a chamber approximately 4–6 inches deep in the soil. Adult moths emerge in mid- to late spring and may migrate long distances. Eggs resemble small pearls and are laid singly on foliage. The newly hatched caterpillars possess a horn that is nearly the same length as the body and subsequently pass through four to five additional larval instars over the course of about a month. Full-grown larvae burrow several inches into soil and create a cell in which pupation occurs.

Where these insects can successfully survive winter conditions there are typically two generations produced annually. The adults are very strong fliers and in more northern areas, incidence of tomato and tobacco hornworms from year to year may be strongly influenced by migrations of moths originating from more southerly areas.

B. Egg of a tomato hornworm. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Tomato hornworm caterpillars showing different color morphs. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Adult of the tomato hornworm. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Tomato hornworm, young larva. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Adult of the tobacco hornworm. JOHN CAPINERA, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

G. Tobacco hornworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Pupa of a tobacco hornworm. JOHN CAPINERA, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

WHITELINED SPHINX (Hyles lineata)1 is the most widely distributed sphinx moth in North America. It is particularly common throughout western North America, where it is familiar to gardeners as the most commonly encountered “hummingbird moth” and is marked with a prominent white band on the forewing. Larvae develop on a wide variety of plants, including portulaca, evening primrose, and grape. They can be highly variable in color, ranging from bright green to black. Two generations are produced annually, with overwintering occurring as a pupa in soil. Adults of GREAT ASH SPHINX (Sphinx chersis)1 are also commonly observed as day-flying hummingbird moths. Larvae of this species develop on ash, lilac, and privet.

Larvae of ACHEMON SPHINX (Eumorpha achemon)1 are unusual in that they lose the terminal horn during the last larval molt. Instead, the last-instar larva is marked by a prominent eyespot at the hind end. The caterpillars develop on Virginia creeper, grape, and related vines. Apparently there is one generation produced per year, with full-grown caterpillars most commonly observed in late August and early September. The achemon sphinx has broad distribution throughout most of the U.S. The closely related PANDORUS SPHINX (E. pandorus) has a more restricted distribution to the eastern half of North America, but similarly feeds on grape family plants. Also occurring on Virginia creeper and grape in the eastern U.S. is VIRGINIA CREEPER SPHINX (Darapsa myron).1

Full-grown caterpillar of the pandorus sphinx. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

CATALPA SPHINX (Ceratomia catalpae)1 occurs throughout most of the eastern U.S., being particularly abundant in the southern states, where it may occur from Florida through parts of Texas. It develops on all species of catalpa and is sometimes abundant enough to defoliate trees, usually in August and September. Up to four generations may be produced annually in southern parts of the range. The caterpillars, sometimes known as “catawba worms,” are highly prized as fish bait in some locations. Related species include ELM SPHINX (C. amyntor), which feeds on elm and occasionally birch, basswood, and cherry, and WAVED SPHINX (C. undulosa), which develops on ash, privet, oak, and hawthorn. WALNUT SPHINX (Amorpha juglandis) occurs on black walnut, hickory, beech, butternut, and pecan in eastern North America. It occurs over much of the Continent east of the Rocky Mountains.

Catalpa sphinx moth larva shortly after egg hatch. DAVID SHETLAR

Larva of the elm sphinx. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

B. Whitelined sphinx caterpillar, green phase. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Whitelined sphinx caterpillar, dark phase. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Larva of the achemon sphinx, brown morph. HAROLD LARSEN, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

E. Larva of the achemon sphinx, green morph. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Larva of the great ash sphinx. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Catalpa sphinx larva, light phase. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Catalpa sphinx larva, dark phase. DAVID SHETLAR

I. Adult of the achemon sphinx. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

J. Adult of the catalpa sphinx. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE

SWEETPOTATO HORNWORM (Agrius cingulata), also known as PINK-SPOTTED HAWK MOTH, is a tropical and subtropical species that feeds on sweetpotato and some related weeds. It is common in the southern U.S., occasionally straying into the Midwest.

Hornworms in the genus Hemaris are among the smallest in the family. Adults, sometimes known as “CLEARWING SPHINX” or “BUMBLE BEE CLEARWINGS” often fly during the day. They have an unusual appearance, with wings largely clear of scales and a heavy body form so they somewhat resemble a large bumble bee. Larvae develop on various shrubs, including honeysuckle, snowberry, cherry, plum, and cranberry. HUMMINGBIRD CLEARWING (H. thysbe), found primarily in eastern North America, and the broadly distributed SNOWBERRY CLEARWING (H. diffinis) are the dominant species.

Poplar and willow host many kinds of hornworms. TWINSPOTTED SPHINX (Smerinthus jamaicensis) and ONE-EYED SPHINX (S. cerisyi) are both quite common in northern areas. Twinspotted sphinx occurs primarily in the eastern half of the northern U.S. and southern Canada and one-eyed sphinx in the western half, although ranges overlap. Some of the largest sphinx moths are the BIG POPLAR SPHINX (Pachysphinx occidentalis) and the MODEST SPHINX (P. modesta), restricted to the western half of North America.

Late-instar larva of the modest sphinx, Pachysphinx modesta. DAVID LEATHERMAN

Pair of western poplar sphinx. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

1 Lepidoptera: Sphingidae

A. Adult sweetpotato hornworm. KARAN A. RAWLINS, UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Sweetpotato hornworm larvae, showing different color morphs. FOREST AND KIM STARR, STARR ENVIRONMENTAL, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Adult of the hummingbird clearwing moth. DAVID CAPPAERT

D. Larva of the hummingbird clearwing moth. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Adult of the hummingbird clearwing moth. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Snowberry sphinx. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

G. Larva of the snowberry sphinx. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

H. Adult of the twinspotted sphinx. HOWARD ENSIGN EVANS.

Several caterpillars of the prominent moth family (Notodontidae) are associated with trees and shrubs. In general form, the caterpillars somewhat resemble climbing cutworms but often have distinct markings or fleshy projections. A few species are pests of trees and shrubs, and these are usually observed feeding in groups. In response to disturbance, members of the feeding group typically arch and twitch to deter predators.

WALNUT CATERPILLAR (Datana integerrina)1

HOSTS Walnut, butternut, pecan, and hickory.

DAMAGE Larvae chew leaves, first skeletonizing and later consuming most of the leaf except for main veins.

DISTRIBUTION Much of the eastern U.S. but particularly common in the central and southcentral states.

APPEARANCE Full-grown caterpillars are about 2 inches long, dark purple to gray, with some thin white to yellow stripes along the sides of a body generally clothed in long hairs. When disturbed, a group of larvae usually arch their heads and abdomens in a defensive posture. Adults are moderate-sized brown moths with a wingspan of about 2 inches and are marked with some dark lines.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Winter is spent as a pupa, in a cell constructed in soil in the vicinity of previously infested trees. Adults emerge in mid- to late spring, and females lay eggs in masses. Upon hatching, the caterpillars feed gregariously, first skeletonizing leaves and later feeding more generally. Larvae periodically migrate from foliage to large branches and trunks, where they rest in masses and molt, often in synchrony. The full-grown caterpillars often wander considerable distances before pupating. Two generations are produced in the southern states, with adults emerging in midsummer. One generation is common in northern areas.

OTHER NOTODONTIDS/PROMINENT MOTHS ON SHADE TREES

YELLOWNECKED CATERPILLAR (Datana ministra) is a common species in the Appalachian Mountains and may occur in much of the eastern U.S. The caterpillars are marked with a bright yellow patch behind the head. Young larvae are first orange but turn black in the later instars. They have a wide host range, including many deciduous fruit, nut, and shade trees. AZALEA CATERPILLAR (D. major) is often a serious defoliator of azalea in the southeastern U.S. The caterpillars are brightly patterned, yellow and black with a red head and legs. One generation per year is typical, with peak injury in mid- to late summer.

B. Walnut caterpillar, adult. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Walnut caterpillar egg mass. HERBERT A. “JOE” PASE III, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Walnut caterpillars massed on branch. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Walnut caterpillars at egg hatch. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Yellownecked caterpillars. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Yellownecked caterpillars. DAVID SHETLAR

REDHUMPED CATERPILLAR (Schizura concinna) is probably the most commonly encountered and widespread of the prominent caterpillars in North America. Caterpillars are marked with a pronounced reddish hump behind the head, and during early development they feed gregariously, sometimes stripping individual branches. Apple and crabapple are among the common hosts, although this species develops on many woody plants. One generation is produced per year. The closely related UNICORN CATERPILLAR (S. unicornis) is an unusual brown and green caterpillar with a large fleshy projection on the first segment of the abdomen. Of very similar appearance is FALSE UNICORN CATERPILLAR (S. ipomoeae), sometimes known as “morning glory prominent.” Dark markings on the head and abdomen, absent on false unicorn caterpillar, can distinguish the larvae. Both species of unicorn caterpillars are found throughout most of North America and may feed on a wide range of deciduous trees and shrubs.

ORANGEHUMPED MAPLEWORM (Symmerista leucitys) is a northern species that develops primarily on sugar maple. The caterpillars have an orange-red head and longitudinal black, yellow, and white striping with an orange marking on the hind end. Young stages feed gregariously and skeletonize the upper leaf surface. Older caterpillars are solitary and feed along the leaf margins. REDHUMPED OAKWORM (S. canicosta) also occurs in the northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canada, where it develops primarily on white and bur oak. Basswood, sugar maple, paper birch, beech, and elm are less common hosts.

SADDLED PROMINENT (Heterocampa guttivitta) is a caterpillar of bizarre appearance. First-instar larvae have black antler-like horns behind the head that are lost at the first molt. Full-grown caterpillars are about 1½ inches long, generally green with an orange-red “saddle marking” on the middle. The species is most common in New England. VARIABLE OAKLEAF CATERPILLAR (Lochmaeus manteo) occurs over a broader area of eastern North America, from southern Ontario to northern Texas. White oak is the preferred host, but several other trees are occasionally infested. Damage is most common in the southern states, where two generations per year can occur. This caterpillar can also cause blistering of exposed skin from a formic acid mixture it can spray when disturbed.

The CALIFORNIA OAKWORM (Phryganidia californica)1 is a common caterpillar along coastal areas of California and southern Oregon and is associated with coast live oak. Caterpillars survive the winter as early-stage larvae on the underside of leaves, causing minor skeletonizing. They rapidly develop during early spring and may defoliate trees during outbreaks. They then pupate on bark of trunks, suspended from limbs or on nearby vegetation. Adults, which are tan-gray moths with a wingspan of approximately 1¼ inches, are weak fliers and subsequently lay their eggs in the near vicinity of previously infested plants. Eggs are laid as small masses on twigs or leaves during late summer and early fall. Two generations per year are normally produced; a third generation is sometimes produced if favorable conditions occur.

1 Lepidoptera: Notodontidae

A. Redhumped caterpillar. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Unicorn caterpillar. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

C. False unicorn caterpillar. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Adult of the unicorn caterpillar. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Orangehumped oakworm. USDA-FOREST SERVICE REGION 2, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Redhumped oakworm. BRUCE WATT, UNIVERSITY OF MAINE, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Saddled prominent. BRUCE WATT, UNIVERSITY OF MAINE, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Variable oakleaf caterpillar. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. California oakworm. JACK KELLY CLARK, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM

The giant silkworms (Saturniidae family) include the largest caterpillars that can be encountered, with some more than 5 inches long. All feed on leaves of trees and shrubs, and individual caterpillars consume impressive amounts toward the end of their life cycle, usually in mid- to late summer. Rarely are they abundant enough to cause significant injury; however, their presence is mostly a curiosity—or even a source of wonder—because of their large size and appearance. Furthermore, populations of several species have been in sharp decline for many years, due to several human-assisted causes.

Adults, often known as royal moths, are large moths that may have a wingspan exceeding 6 inches. Adults do not feed and thus die a few days after emergence from the cocoon. Moths are usually present in late spring or early summer.

CECROPIA MOTH (Hyalophora cecropia)1

HOSTS At least 50 species of deciduous trees and shrubs are hosts of larvae. Boxelder, sugar maple, wild cherry and plum, apple, alder, birch, dogwood, willow, lilac, ash, and viburnum are common hosts.

DAMAGE Cecropia moth caterpillars can be among the most conspicuous late-season defoliators of shrubs. Because the feeding occurs late in the season, however, it causes little, if any, plant injury.

DISTRIBUTION Primarily east of the Rockies.

APPEARANCE The larvae are large, sluggish, sea green caterpillars, from 3 to 4 inches long. They possess numerous colored knoblike tubercles—pale blue along the sides, orange on the thorax, and yellow on the abdomen. Adults are large and colorful moths with a wingspan of 5½ to 6½ inches. They have brownish gray wings with white crescent-shaped eyespots, a dark spot near the tip of each forewing, and red-bordered crossbands on the abdomen. The pupa develops in a tough cocoon attached along its entire length to a twig.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Winter is spent as a pupa in the cocoon, usually attached to a small branch. Adults emerge in late spring. They do not feed, but they mate and females lay eggs on twigs over the course of a few days before dying. The caterpillars then begin to feed on leaves and develop over a period of 2–3 months. All stages of cecropia moth caterpillars bear prominent tubercles on the body, but the caterpillars develop more intense coloration as they age. One generation is produced per year.

Cocoon of the cecropia moth. DAVID SHETLAR

OTHER GIANT SILKWORMS/ROYAL MOTHS

HICKORY HORNED DEVIL (Citheronia regalis)1 is a caterpillar of bizarre appearance that may be 5 inches long. Generally blue green, it has numerous spikes, particularly two long curving pairs on the thorax, giving it a rather dragonlike appearance. It is found in much of the eastern U.S., being more common in the southern states. Hickory, walnut, and a few other trees and shrubs may host the caterpillars. When feeding is completed, the larvae descend trees and walk about in search of soil in which to pupate. Adults are large moths with prominent orange markings and stripes known as REGAL MOTHS.

B. Late-instar cecropia moth caterpillar. JOHN GHENT, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Cecropia moth eggs. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Early-instar cecropia moth caterpillars. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Hickory horned devil, full-grown larva. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Hickory horned devil, young larva. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Regal moths, adults of the hickory horned devil. DAVID SHETLAR

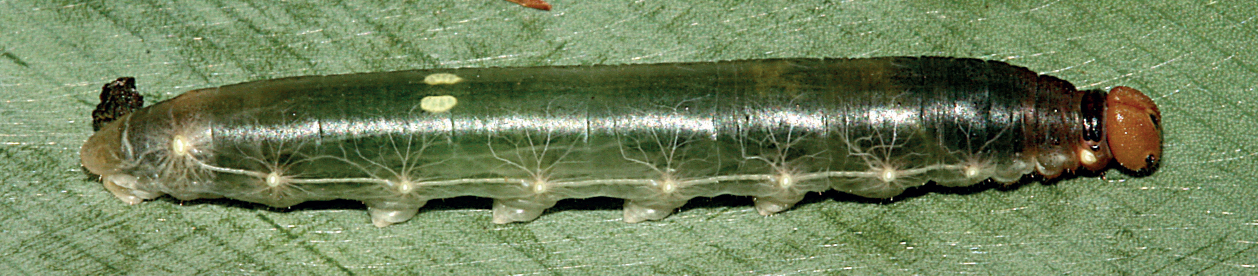

LUNA MOTH (Actias luna)1 is one of the most distinctive moths of North America, having pale green wings developed into an elongate “swallowtails” and marked with a yellow spot. Larvae are translucent pale green with a pale yellow line along the lower side and feed on a wide variety of nut, fruit, and shade trees. The species is known from parts of Texas and Nebraska eastward but has become considerably less abundant in recent decades.

Caterpillar of the luna moth. GERALD J. LENHARD, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

Larvae of POLYPHEMUS MOTH (Antheraea polyphemus)1 are stout-bodied, apple green, and only sparsely marked by spines. This species is widely distributed throughout much of North America and feeds on many deciduous trees and shrubs in late summer. Dogwood, oak, willow, maple, and birch are among the common plants on which the caterpillars develop.

Cocoon of the Polyphemus moth cut away to expose pupa. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

Caterpillars of PROMETHEA MOTH (Callosamia promethea)1 are pale bluish green and possess four prominent red-orange spikes near the head and one yellow spike near the rear. They occur in the eastern U.S. and southeastern Canada. Hosts include cherry, magnolia, tuliptree, ash, and lilac. The closely related TULIPTREE SILKMOTH (C. angulifera) develops solely on tuliptree and with a distribution in eastern North America that matches its host plant.

Promethea moth caterpillar. TOM MURRAY

IMPERIAL MOTH (Eacles imperialis)1 develops on a wide range of shade trees, including some conifers as well as deciduous trees. Most often the caterpillars are green and covered with short, light blue-green hairs. Darker morphs sometimes occur that are largely brown or even black.

B. Polyphemus moth caterpillar. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Caterpillar of the promethea moth. GERALD J. LENHARD, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Polyphemus moth. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Imperial moth caterpillar. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Imperial moth caterpillar. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

G. Imperial moth. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

PANDORA MOTH (Coloradia pandora)1 is a western species associated with pines. It has had several historical outbreaks, and the caterpillars have sometimes been used as a food source by Native Americans. The life cycle requires 2 years to complete, with partially grown larvae wintering on the tree during the first year and then moving to the soil to pupate in a cocoon following the second year.

GREENSTRIPED MAPLEWORM (Dryocampa rubicunda)1 is associated with maple throughout the eastern U.S. and is particularly common in the southern half of its range where outbreaks sometimes are recorded. Caterpillars possess a cherry red head and yellow-green body with seven dark green lines running the length. The insect is also marked with two slender, flexible horns behind the head. ORANGESTRIPED OAKWORM (Anisota senatoria)1 occurs in much of the eastern half of the U.S., excluding some of the southeastern states. It feeds on oak and occasionally causes extensive defoliation in late summer. SPINY OAKWORM (A. stigma) is marked by two prominent spines on the thorax. It ranges east from southern Ontario to parts of Texas and develops on oak and hazel.

IO MOTH (Automeris io)1 is one of the smaller giant silkworms, reaching about 3 inches when mature. The larvae possess numerous stinging hairs that produce a painful reaction on touch. Io moth caterpillars are the most widespread and commonly encountered of the caterpillars in North America that can produce painful stings.

Larvae are large, pale green caterpillars with a lateral stripe of pink and creamy white down each side, covered with clusters of branching spines. They develop on a wide range of deciduous shade trees including willow, elm, apple, maple, hickory, and sycamore and are about 3 inches long at maturity. Pupation occurs in a cocoon, and the stinging hairs of the larvae coat the cocoon. Adults have a wingspan of 2½ to 3 inches, the females with lightly patterned purplish red wings, the males smaller with yellowish wings, and both with a large circular black eyespot on the hindwings. One generation is produced in most areas, but two can occur in the more southern states.

A few species of Hemileuca1 species, sometimes known as “buck moths,” are occasional tree pests. Older larvae are generally dark and possess numerous tufts of branched spines. The spines are attached to poison glands capable of producing a painful sting, although not as painful as that of Io moth. The most common western species, NEVADA BUCK MOTH (H. nevadensis), develops on poplar and willow. EASTERN BUCK MOTH (H. maia) is an eastern species that feeds on scrub, live, blackjack, and dwarf chestnut oak. NEW ENGLAND BUCK MOTH (H. lucina) is restricted to the New England States and feeds on oak, black cherry, willow, gray birch, and blueberry. Adults of all buck moths are fairly large, fly during fall days, and have wings prominently patterned with white and black. Egg masses survive winters and the larvae feed over much of the spring and summer months.

1 Lepidoptera: Saturniidae

B. Greenstriped mapleworm adult. WILLIAM CIESLA, FOREST HEALTH MANAGEMENT INTERNATIONAL, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Greenstriped mapleworm. GERALD J. LENHARD, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD. ORG

D. Orangestriped oakworm. DAVID SHETLAR.

E. Spiny oakworm. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Io moth caterpillar. STEVEN KATOVICH, USDA-FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Adult of the Io moth. RONALD J. BILLINGS, TEXAS A&M FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Caterpillar of the eastern buck moth, Hemileuca maia. GERALD J. LENHARD, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Adult of the eastern buck moth, Hemileuca maia. GERALD J. LENHARD, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD. ORG

SLUG CATERPILLARS/FLANNEL MOTHS AND OTHER STINGING CATERPILLARS

The slug caterpillars (Limacodidae) are often bizarre in appearance and attract attention but are rarely abundant. Most larvae possess prominent spines and bright coloration and may be an unusual shape. The spines are highly irritating upon contact and can produce a painful reaction. Because of the stinging hairs, some species are locally known as “asps.”

SADDLEBACK CATERPILLAR (Sibine stimulea)1 is among the most commonly encountered species, found in much of the eastern half of the U.S. and particularly abundant in the Atlantic States. Larvae are brown with a pronounced green saddle-shaped area over the center of the body. Colorful sharp spines, connected to poison gland cells, extend from both front and back and are extremely painful. Saddleback caterpillars feed on apple, pear, cherry, corn, canna, lily, dahlia, and many other plants but are never abundant enough to cause serious plant injury. The pupa occurs in a cocoon, and the stinging hairs are retained on the surface. Adults fly in July and August in the north and year-round in the extreme south. STINGING ROSE CATERPILLAR (Parasa indetermina)1 also has tufts of stinging hairs, but the general color is reddish or orange red with striping down the center of the back. Common hosts include wild rose, redbud, oak, hickory, bayberry, wild cherry, and sycamore. Two Euclea1 species (E. delphinii, E. nanina) with stinging hairs, known as “SPINY OAK SLUGS” feed on a wide variety of trees and shrubs in eastern North America.

Caterpillars of HAG MOTH (Phobetron pithecium)1 have numerous long, curved spines along the sides and particularly enlarged areas on the third, fifth, and seventh segments. The spines are connected to poison glands, and contact with the spines produces a painful reaction. Larvae feed on many deciduous trees and shrubs, including wild rose, sassafras, alder, and spirea.

Another species with stinging hairs that is common in parts of the southern U.S. is PUSS CATERPILLAR (Megalopyge opercularis).2 Larvae are densely covered in long hairs that may be yellowish, reddish brown, or mouse gray. The young larvae typically feed in groups, skeletonizing the leaf surfaces of many deciduous trees including oak, elm, hackberry, and sycamore. Two generations are produced annually.

A related species that occurs in the southeastern U.S. is HACKBERRY LEAF SLUG (Norape ovina).2 Larvae have six small tufts of stinging hairs on each segment and feed on several woody plants, particularly redbud, red maple, and hackberry. The adult is known as the WHITE FLANNEL MOTH. A related species found in southwestern states that also has stinging hairs is MESQUITE STINGER (N. tenera).

1 Lepidoptera: Limacodidae

2 Lepidoptera: Megalopygidae

B. Stinging rose caterpillar. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Adult of the stinging rose caterpillar. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. A spiny oak slug. BRUCE WATT, UNIVERSITY OF MAINE, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Caterpillar of the hag moth. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA-ARS, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Puss caterpillar. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Hackberry leaf slugs. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

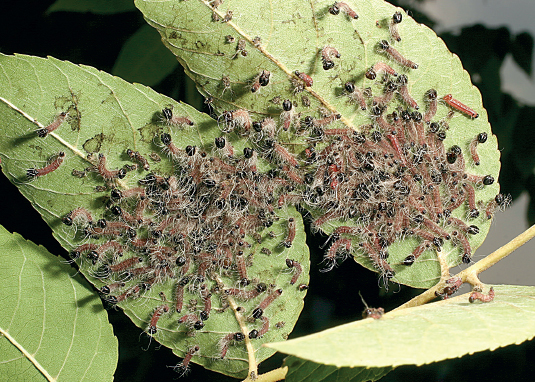

The term “tussock moth” is loosely applied to certain caterpillars, within two families, that are thickly covered with hairs and have patches of hairs clumped together in dense tufts. The hairs of many species can be very irritating to skin and eyes.

WHITEMARKED TUSSOCK MOTH (Orygia leucostigma)1

HOSTS A wide variety of trees and shrubs, including apple, basswood, elm, sycamore, maple, birch, pyracantha, live oak, mimosa, and redbud. Some conifers are occasional hosts.

DAMAGE Larvae chew leaves, occasionally causing significant defoliation.

DISTRIBUTION Generally distributed east of the Great Plains. Also known from British Columbia.

APPEARANCE Larvae are cream-colored overall with coral red heads. On four segments of the abdomen distinctive brushlike tufts of white or yellowish hairs are present, and there are pencil-like tufts of hairs at both the hind and front ends. Adult females are wingless, about ½ inch in length. Adult males are grayish brown with a wingspan of about 11/5 inches and a distinctive white spot at the base of the forewing.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Winter is spent as eggs that were laid adjacent to wherever females previously pupated. Eggs hatch in mid- to late spring, and the early-stage larvae skeletonize leaves. Later-stage larvae feed more generally and become full grown 3–4 weeks after egg hatch. They often wander a considerable distance before pupating, and the pupal stage occurs in a cocoon mixed with hairs of the larvae. A second generation is common in much of the range, with peak feeding in midsummer.

RELATED AND SIMILAR SPECIES