A. Damage by codling moth. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

INSECTS AND MITES ASSOCIATED WITH FLOWERS, FRUITS, NUTS, AND SEEDS

CODLING MOTH (Cydia pomonella)1

HOSTS Primarily apple and pear. Occasionally large-fruited crabapple, apricot, quince, hawthorn, and peach. Often infests developing walnut husks.

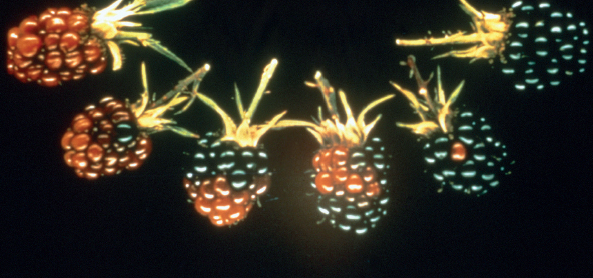

DAMAGE Larvae tunnel into the fruit of apple, pear, and crabapple. Less commonly they also damage other fruits. Codling moth is the single most important insect pest of tree fruits in North America.

DISTRIBUTION Throughout North America, common

APPEARANCE Larvae are pale tan, gray, or pink with a dark head and are found associated with the fruit. Adults are small (½ inch long) gray moths with coppery tipped forewings.

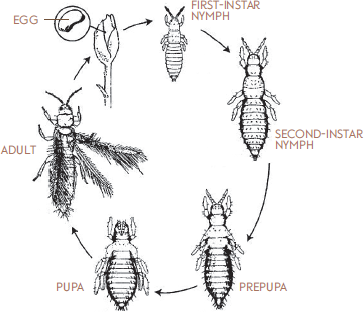

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Codling moth larvae spend the winter inside a silken cocoon attached to rough bark or other protected locations around a tree. With warm spring weather they pupate, and the adult moths later begin to emerge around blossom time. The spring appearance of this stage may occur primarily over the course of 1 or 2 weeks but can be much more prolonged if weather is cool.

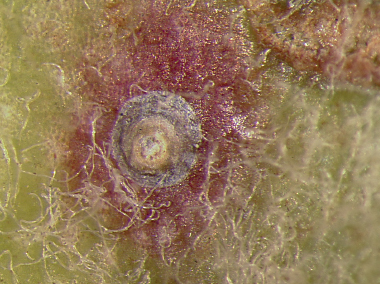

During periods when early evening temperatures are warm (above 60° F) and not windy, the moths lay small white eggs on leaves. The larvae hatching from the eggs may feed first on the leaves but then migrate to the fruit, usually entering the calyx (flower) end. They tunnel the fruit, feeding primarily on the developing seeds. After about 3–4 weeks, the larvae become full grown, leave the fruit, and crawl or drop down from the tree to spin a cocoon and pupate.

After about 2 weeks, most—but not all—of the second generation of moths emerge from the pupae. The remaining pupae stay dormant, emerging the following season. (For example, in western Colorado only about two-thirds of the larvae go on to produce a second generation, and fewer than half of their progeny go on to produce a third generation.) Summer moths lay eggs directly on the fruit, and damage by the larvae to fruit is greatest at this time. When full grown, the larvae emerge from the fruit and seek protected areas in which to pupate.

RELATED SPECIES

Larvae of the HICKORY SHUCKWORM (Cydia caryana) develop within the shuck surrounding developing nuts of pecan and hickory, and this insect is considered one of the most destructive pests of pecans in the U.S. Presently hickory shuckworm is found throughout eastern North America in association with its host, but its range has extended westward into New Mexico.

The overwintering stage is a late-instar larva in the old shucks of fallen nuts. Pupation occurs in late winter or early spring and first generation adults begin to emerge in early May. Most egg laying by this first generation will occur on hickory, if available, which produces nuts of suitable size at this time. Eggs may be laid on leaves of pecan during the first generation, but nuts are not suitable for development and few larvae survive; most of those that are successful sustain themselves feeding in and around the galls produced by pecan phylloxera (page 324). Larvae produced in the second, early summer generation feed on the interior of pecans, causing damaged nuts to drop. Moths of the third generation usually appear in August and lay eggs on maturing nuts. At this point in time, pecan shells have hardened and hickory shuckworm caterpillars tunnel through the green shucks. Feeding injuries they produce include delayed maturity and incomplete kernel development.

B. External symptoms of codling moth damage to apple. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Codling moth larva feeding in core. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Codling moth pupa. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Codling moth eggs on fruit. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

F. Adult codling moth. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Entry hole produced by codling moth larva. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

H. Hickory shuckworm larva and damage. LOUIS TEDDERS, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Adult hickory shuckworm pupa. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

J. Adult hickory shuckworm. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

FILBERTWORM (Cydia latiferreana) is associated with almost all cultivated and wild nuts grown in North America and is particularly common in oak acorns and hazelnut. Winter is spent as a full-grown larva in a cocoon on or in the vicinity of the previously infested host. Pupation occurs in spring, and adults are present over an extended period from late June into October. Eggs are usually laid on leaves, but the larvae migrate to nuts and develop in them. Larval development usually takes less than 1 month, after which the larvae exit to search for a protected site, where they spin a cocoon. One generation per year is normal, but egg laying continues over a period of several weeks.

PEA MOTH (Cydia nigricana) is primarily a pest of dried pea in the northwestern states. Occasionally it also damages green peas where large numbers of dried peas are grown nearby. The overwintering caterpillars pupate in spring, and the adults are present about the time peas flower in later spring. Eggs are laid singly near the flowers, and the caterpillar immediately bores into the developing pods. Larvae feed on the developing seeds and may injure several pods, often leaving little external evidence of infestation. When full grown they move to the soil and form a shelter in which they spend the winter. One generation per year is normal in much of the range, but two may occur in more southern areas.

ORIENTAL FRUIT MOTH (Grapholita molesta)1

HOSTS Peach, apricot, and nectarine are most seriously damaged, but plum, cherry, apple, pear, almond, and rose are other hosts.

DAMAGE Larval tunneling into twigs causes wilting terminals (“shoot strikes”), and two or three such injuries may be produced by an individual insect. Fruit is damaged as larvae feed randomly through the flesh, not consuming the seeds in the manner of codling moth. Fruit injuries also differ in that entry holes produced by Oriental fruit moth are often inconspicuous.

DISTRIBUTION An introduced species that is widespread in orchards in the eastern and southern U.S. It has spread to California and also occurs in isolated area of many western states.

APPEARANCE Adults are small grayish moths, about ⅖ inch, that fly just after sunset. Larvae are pink with a brown head, very similar in appearance to codling moth larvae.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Winter is spent as a mature larva in a cocoon on or around a previously infested tree. Adults begin to emerge about the time peach blossom buds begin to show pink, and flights from this first generation may extend for almost 2 months. Eggs are laid on newly emerged shoots, and larvae feed in twigs. A second generation occurs in late spring (California) or early summer (Michigan) and attacks both twigs and fruit. Fruit injuries also occur when larvae move from twigs that harden and become unsuitable. A third generation occurs as peaches begin to mature, and most fruit infestations occur at this time. A small fourth generation is sometimes produced in Michigan and Ohio; five generations per year are normally produced in California.

RELATED SPECIES

CHERRY FRUITWORM (Grapholita packardi) damages blueberry, tart cherry, apple, and peach throughout the northern two-thirds of the U.S. and Canada. Hawthorn and rose are other hosts. Larvae develop in fruit, and individuals may damage several small fruits before becoming mature. They then migrate to nearby canes, stubs of pruned twigs, pithy weeds, or other protected sites and burrow to produce a winter shelter. Winter is spent as full-grown larvae in cocoons, and pupation occurs in spring. Moths fly and lay eggs over a period of a month during the period when young fruits are present. One generation is produced annually.

A. Filberworm adult and pupal case. DONALD OWEN, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND FIRE PROTECTION, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Filbertworm larva and damage. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

C. Pea moth larva and damage. ART ANTONELLI, WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY

D. Oriental fruit moth larva in peach. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

E. Terminal wilting caused by Oriental fruit moth larval tunneling in peach shoot. CLEMSON UNIVERSITY–USDA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SLIDE SERIES, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Adult Oriental fruit moth. TODD M. GILLIGAN AND MARC E. EPSTEIN, USDA-APHIS ITP, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Cherry fruitworm adult. MARK DREILING, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Lesser appleworm larva and damage. P. J. CHAPMAN, NEW YORK STATE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION, BUGWOOD.ORG

LESSER APPLEWORM (Grapholita prunivora) is a minor pest of apple and also occurs on cherry and plum. Primary damage to apple occurs when larvae tunnel shallowly under the fruit skin. Twigs are also tunneled. Two generations per year are reported from Michigan to New York.

Grapholita delineana, the EURASIAN HEMP BORER, feeds primarily within the stems of hemp; however, larvae present in later generations may spin loose webs over leaves and clusters of developing seeds and damage young seeds.

1 Lepidoptera: Torticidae

TOBACCO BUDWORM (Heliothis virescens)1

HOSTS A wide range. Although solanaceous plants such as petunia, nicotiana, and tobacco are particularly favored, tobacco budworm also feeds on geranium, ageratum, chrysanthemum, snapdragon, strawflower, rose, and many other flowering plants. It is rarely a vegetable pest, unlike the corn earworm it resembles.

DAMAGE Feeding injuries are concentrated on flower buds, the caterpillars favoring the reproductive tissues. Small larvae may restrict feeding to bud tunneling; later stages may consume entire buds and chew petals. Foliage is rarely damaged, but tunneling of leaf buds may occur. Reduced flower production (“loss of color”) and ragged flowers result from tobacco budworm injuries.

DISTRIBUTION This insect is most damaging in areas of the southern U.S., as hard freezing temperatures can kill overwintering pupae. Mild winter conditions and some migration by the adult moths can allow significant infestations in more northern areas, however.

APPEARANCE Tobacco budworm is a moderate-sized insect, and caterpillars can reach 1½ inches when full grown. Color can be highly variable and is related in part to diet. Caterpillars may be nearly black to pale brown, with green and reddish forms also common. Banding may be present and prominent in darker caterpillars but indistinct in others. The presence of tiny “microspines” on some segments of the abdomen is used to separate this insect from the closely related corn earworm (tomato fruitworm/bollworm).

The adult moth is a typical “cutworm” form with a wingspan of about 1½ inches. The general color is pale green, and the forewing is marked with 4 light and slightly wavy bands. Pupae, which are found in the soil, are spindle-shaped and about ¾ inch long, typical of other cutworms.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Tobacco budworm overwinters as a pupa in an earthen cell buried a few inches beneath the soil surface. In spring, adults emerge and are active in the early evening. After mating, females glue eggs singly onto flower buds and leaves. The young caterpillars emerge and feed on flower buds and petals. They become full grown in about 3 weeks, causing extensive injury. They then drop to the soil and pupate. In northern areas two generations per season are usually produced, with the highest caterpillar populations often occurring in August and early September. Four to five generations occur in the southern states.

RELATED SPECIES

TOMATILLO FRUITWORM (Heliothis subflexa) is a closely related species, and the adults are also quite similar in appearance to H. virescens. The caterpillars specialize in Physalis spp. and can be a serious pest of tomatillo fruit. Another closely related species is H. phloxiphaga, which develops on seeds and flowers of a wide variety of host plants, including sunflower, yarrow, asters, snapdragon, and phlox.

1 Lepidoptera: Noctuidae

B. Geranium bud tunneled by tobacco budworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Eggs of tobacco budworm on geranium buds. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Tobacco budworm larva chewing on petunia petals. JOSEPH BERGER, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Tobacco budworm pupa. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Adult of tobacco budworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Tomatillo fruitworm larva and damage. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Adult of the tomatillo fruitworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. Larva of Heliothis phloxiphaga. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

CORN EARWORM/TOMATO FRUITWORM/BOLLWORM (Helicoverpa zea)1

HOSTS A wide range, including many vegetables, field crops, fruits, flowers, and weeds. Corn, tomato, pepper, cotton, sorghum, and lettuce are among the crops most seriously damaged.

DAMAGE Larvae tunnel into ear tips of sweet corn, bore into various fruiting vegetables, and feed on leaves of lettuce and other vegetables. Corn earworm is considered one of the most destructive insects in the U.S., attacking many of the most important field and vegetable crops.

DISTRIBUTION Throughout North America except extreme northern areas. Where freezing winter temperatures prevent wintering, annual migrations originating from the southern U.S. and Mexico allow corn earworm to recolonize during summer and early fall.

APPEARANCE Young larvae are pale-colored but darken as they get older. A range of colors may be present, from pale green to pink or even black. Adult moths are typical cutworm form, with light brown wings that often have a dark spot in the center.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Corn earworm is a tropical/subtropical species, and in parts of the southern U.S., development may be continuous. Winter temperatures limit survival in much of North America, and the species often dies out each year. In the northern U.S. and Canada, infestations arise from annual migrations of the adult moths from the southern U.S. and Mexico. Migration flights typically begin in June, but with favorable weather additional migrations can occur through the growing season.

Moths fly at night, feeding on nectar and laying eggs singly on suitable host plants. On sweet corn, eggs are laid on green silks; on tomato and pepper, they are usually laid on the new leaves near flowers of developing fruit. Once corn earworm has migrated into an area, damage may become somewhat cyclical, as peak numbers of eggs tend to be laid during the period around a full moon.

Eggs hatch in about 2–5 days, and the young caterpillars begin to tunnel into the plants. Corn earworm caterpillars usually feed for about 4 weeks before becoming full grown. Older larvae become highly cannibalistic, and it is fairly uncommon to find more than one in a single corn ear. When full grown, they drop from the plant, construct a small cell in the soil, and pupate. Adults emerge in 10–14 days and produce the next generation.

OTHER FRUIT-INFESTING CUTWORMS

Caterpillars of several other species of climbing cutworms are occasionally associated with trees in mid- to early spring. Most widespread is the SPECKLED GREEN FRUITWORM (Orthosia hibisci),1 which feeds on a wide range of deciduous trees and shrubs, including rose, apple, pear, cherry, peach, plum, crabapple, apricot, hawthorn, poplar, maple, oaks, willow, and white birch. The caterpillars feed primarily on foliage and normally cause little injury, but when developing buds and fruit are present, these may be chewed. These injuries can cause premature fruit drop, but when injuries are small the fruit continues to grow, becoming misshapen because of the injured area, and develops corky tissue around the old chewing wound.

Speckled green fruitworm spends the winter underground in the pupal stage. Adults are among the first moths to emerge, in March or April, and females lay eggs singly or in small groups near plant buds. The caterpillars feed on the new leaves and remain on the tree throughout their development. By early June the larvae become full grown, move to the soil and pupate. One generation is produced per year.

B. Adult corn earworm. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Corn earworm eggs. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

D. Young corn earworm larva. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Corn earworm larvae showing range of coloration. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Corn earworm larva, prepupa, and pupa. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

G. Corn earworm in tomato, a “tomato fruitworm.” DAVID SHETLAR

H. Speckled green fruitworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. Speckled green fruitworm feeding on rose bud. ROBIN ROSETTA, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

J. Speckled green fruitworm feeding on apple. DAVID SHETLAR

K. Pear injured by speckled green fruitworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

GREEN FRUITWORM (Lithophane antennata)1 is found throughout North America but is particularly abundant in the Midwest and northeastern states. It is also active early in the season, with moths emerging to lay eggs in late winter and spring when evening temperatures persist above about 50° F for a few hours. Eggs are laid singly or in small masses, and the larvae feed on opening buds, leaves, and young fruit. Other species include PYRAMIDAL FRUITWORM (Amphipyra pyramidoides),1 FOURLINED FRUITWORM (Himella intractata),1 and YELLOWSTRIPED FRUITWORM (Lithophane unimoda).1 Injury is similar, and several species may be present concurrently. Life cycles vary somewhat, with Lithophane species overwintering as adult moths and pyramidal fruitworm as eggs. Damage to buds of various flowers and developing fruit is also sometimes produced by VARIEGATED CUTWORM (Peridroma saucia).1

1 Lepidoptera: Noctuidae

PICKLEWORM (Diaphania nitidalis)1

HOSTS Summer and winter squash are most commonly damaged. Cucumber, cantaloupe, and some pumpkins are other hosts.

DAMAGE Larvae tunnel buds, blossoms, and fruit.

DISTRIBUTION Pickleworm is restricted by winter weather to parts of southern Florida and Texas; however, northward migrations occur annually into the Carolinas.

APPEARANCE Pale in early stages, pickleworm caterpillars darken with age and may be somewhat greenish or pink (turning coppery before pupation) with a dark area behind the head. Full-grown caterpillars are about ½ inch. Adults are attractive moths with about a 1-inch wingspan. The wings are generally margined with a yellowish band, and there is a prominent tuft on the hind end of the body.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Eggs are laid in small groups on buds, flowers, and new shoots. Larvae develop by feeding on the plant over a period of 2–3 weeks and then pupate in a thin cocoon tucked into folds of leaves or among crop debris. Adults usually disperse to weedy or woody areas where they spend the day and return to fields at night.

In the extreme southern U.S. where host plants are available year-round, activity may occur continuously. In Georgia and the Carolinas where hosts die out in winter and pickleworm fails to survive, 2–4 generations are typically produced per year following spring migration.

RELATED SPECIES

MELONWORM (Diaphania hyalinata)1 is closely related to pickleworm and shares an almost identical host range and distribution in North America. Despite its name, it does not damage watermelon, and cantaloupe is not a favored host. Melonworm larvae are pale yellow-green and restrict feeding almost entirely to foliage. Direct fruit damage is limited to the fruit surface and produces scarring of the rind.

B. Adult of the pyramidal fruitworm known as the copper underwing. LACY L. HYCHE, AUBURN UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Variegated cutworm feeding on tomato. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

D. Pickleworm tunneling squash fruit. GERALD HOLMES, CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY AT SAN LUIS OBISPO, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Pickleworms feeding on surface of squash fruit. GERALD HOLMES, CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY AT SAN LUIS OBISPO, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Adult pickleworm. CHAZZ HESSELEIN, ALABAMA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SYSTEM, BUGWOOD.ORG

G. Melonworm. ALTON N. SPARKS JR., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Adult melonworm. ALTON N. SPARKS JR., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

LIMABEAN POD BORER (Etiella zinckenella)1 damages various legumes in the western states; it can also be found but is less damaging in some southeastern states. Lupine, black locust, lima bean, snap bean, cow pea, and milk vetch are among the common hosts. Larvae destroy buds and blossoms and later tunnel into pods, destroying seeds and fouling pods with their excrement.

PECAN NUT CASEBEARER (Acrobasis nuxvorella)1 is found throughout areas where pecans are grown, from Florida to southern New Mexico. Adult moths are first present around late May/early June and lay eggs near the calyx of nutlets shortly after pollination. Newly hatched larvae feed first on buds and may cause flowers to abort. They later bore into the base of developing nutlets, sometimes destroying an entire cluster. Larvae feed for about 4 to 5 weeks and pupate within the nut. Adults emerge in July and lay eggs. Larvae from this second generation feed primarily on pecan shucks, causing little damage. Third-generation larvae feed little, moving to wintering shelter on twigs where they form a protective cocoon (hibernaculum).

CRANBERRY FRUITWORM (Acrobasis vaccinii)1 is an important pest of blueberry; cranberry and huckleberry are other common hosts. Eggs are laid around the blossom end of the fruit and larvae usually enter the fruit around the stem. Berries can be loosely webbed together, and conspicuous brown frass is kicked out of the fruit as the larvae feed. When full-grown, larvae move to the soil and construct a cocoon among surface debris or dug shallowly in the soil and pupate in late winter. One generation is produced annually. A related species is DESTRUCTIVE PRUNE WORM (A. tricolorella), also known as MINEOLA MOTH. It produces similar injuries to cherry and plum in most cherry-producing areas and spends winter as a partially grown larva that returns to feed on buds in midspring.

SUNFLOWER MOTH (Homoeosoma electella)1 is common in the southern and central U.S., developing in flower heads of sunflower, coneflower, zinnia, and related plants. The overwintering larvae are fairly sensitive to cold, but adults are highly migratory and flights from the south-central states may colonize areas into Canada and the northeastern states. Eggs are laid on flower heads and larvae feed on florets and then on the developing seeds, consuming or damaging numerous seeds. They also cover heads with a fine silk which, mixed with plant debris and frass, gives them an unattractive appearance. The caterpillars are quite distinctive, being purplish or reddish brown with light stripes running the length of the body.

The genus Dioryctria1 contains several species, collectively known as CONEWORMS, most commonly observed feeding on conifer cones. In the southeastern states, west to parts of Texas, SOUTHERN PINE CONEWORM (D. amatella) is common in pine seed cones. The young larvae overwinter on the bark and move to the young cones and shoots in late spring. Cankers produced by rust fungi are also commonly colonized. In the northern half of the U.S. and southern Canada, FIR CONEWORM (D. abietivorella) develops in Douglas-fir, fir, pine, and spruce. In cones it leaves a clean, pitch-free exit hole. It does considerable feeding on other parts of the plant, including buds, shoots, and even the trunk, in a manner similar to that of twig- and trunk-boring members of the genus (pages 336 and 430). Among the other species that develop predominantly in cones are SPRUCE CONEWORM (D. reniculelloides) in spruce and fir, BLISTER CONEWORM (D. clarioralis) on several southern pines, PINE CONEWORM (D. auranticella) on various pines, notably Austrian, in the Great Plains States, and WEBBING CONEWORM (D. disclusa) on various pines in eastern North America. In addition, some larvae of some Eucosma species develop within cones. Eucosma tocullionana2 is a common species associated with cones of eastern white pine.

EUROPEAN CORN BORER (Ostrinia nubilalis)3 is primarily a stem and stalk-boring species (page 358) that affects corn and a wide range of other vegetable and herbaceous ornamental plants. Fruiting structures may also be injured and the borer can be found developing within corn ears, pepper fruit, snap bean pods, and many other plants.

1 Lepidoptera: Pyralidae

2 Lepidoptera: Tortricidae

3 Lepidoptera: Crambidae

B. Larva of the pecan nut casebearer. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

C. Pecan nut caseborer damage to developing pecans. LOUIS TEDDERS, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Adult of the pecan nut casebearer. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Cranberry fruit larva and damage to blueberry. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Sunflower moth larva and damage to coneflower. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

G. Adult sunflower moths. PHIL SLODERBECK, KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Cone of Austrian pine damaged by pine coneworm. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. Webbing coneworm larva in developing cone. LARRY R. BARBER, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

J. External evidence of feeding injury by Eucosma tocullionana in white pine cone. STEVEN KATOVICH, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

K. Entry hole produced by European corn borer in pepper. RIC BESSIN, UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY

L. European corn borer in pepper fruit. RIC BESSIN, UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY

OTHER FRUIT- AND SEED-INFESTING CATERPILLARS

GRAPE BERRY MOTH (Paralobesia viteana)1 is an eastern species that develops on grape. The spring generation of larvae is most damaging as larvae web together clusters of flower buds and consume most of them. Tender shoots and newly set berries may also be eaten. Summer-generation larvae develop in the berries and may feed on 2 or 3 berries while developing. Two generations are produced annually, with winter spent as pupae.

EUROPEAN GRAPEVINE MOTH (Lobesia botrana)1 has a very wide range of plant hosts but is most often found feeding on wine grapes and flax-leaved daphne. Potentially serious damage can be done to wine grapes when the caterpillars feed on bud clusters, flowers, and fruit. In addition to these direct losses, feeding injuries to fruit also create wounds that allow infections with Botrytis fungi. The first North American detections of this insect were in California in 2009.

BANDED SUNFLOWER MOTH (Cochylis hospes)1 is common in the northern Great Plains but can be found from northern Texas east to North Carolina. Newly hatched larvae are white with a dark head, but body color changes throughout larval development and can vary from pink or yellow to purple or green at maturity. Females lay eggs in the base of flowers in late July, and larvae first feed on the florets. They later partially consume several seeds before moving to the soil and creating an overwintering cell in which they spend the winter. Pupation occurs the following June. The adult moths are straw-colored with a wingspan of about ½ inch.

Several species of LEAFROLLER MOTHS (page 128) can cause surface wounding of fruit. The wounding occurs when larvae produce a shelter of leaves that also includes buds and developing fruit. Although these larvae most often feed on leaves, incidental damage to fruit can occur that results in significant distortion of mature fruit. Among the important leafrollers that have potential to damage fruit are EYESPOTTED BUD MOTH (Spilonota ocellana),1 REDBANDED LEAFROLLER (Argyotaenia velutinana),1 OBLIQUEBANDED LEAFROLLER (Choristoneura rosaceana),1 ORANGE TORTRIX (Argyrotaenia citrana),1 BLACKHEADED FIREWORM (Rhopobota naevana),1 OMNIVOROUS LEAFTIER (Platynota stultana),1 and LIGHT BROWN APPLE MOTH (Epiphyas postvittana).1

Caterpillars of NAVEL ORANGEWORM (Amyelois transitella)2 develop in a wide range of fruits and nuts. This species is particularly damaging to fig and almond in southern California. Eggs are laid in fissures of fruit and in cracks of nuts after hulls begin to split. Larvae are cream-colored to slightly pinkish with a reddish-brown head capsule.

PEACH TWIG BORER (Anarsia lineatella)3 develops as a borer in both twigs and fruit in peach. The first-generation larvae, usually present in late April and May, tunnel terminals, producing “shoot strikes” indicated by wilting foliage. Adults from this generation emerge in late spring and subsequently lay eggs on twigs, small leaves, and developing fruit. The caterpillars may move about the plant, and fruit is attacked after the pit begins to harden. Peach twig borer is most common and important as a peach pest in the western U.S. but does occur over much of the country where peaches are produced. Almond and apricots are other hosts, but peach twig borer rarely injures their fruits.

TOMATO PINWORM (Keiferia lycopersicella)3 occurs throughout warmer areas of the southwestern states. Tomato is the primary host, although some related plants such as eggplant, potato, and some nightshade weeds also host the insect. Eggs are laid in small clusters on the leaves, and young larvae mine leaves. Later they emerge and fold leaves, feeding as general defoliators. As the larvae get older, they darken from orange-brown to nearly purplish. Older larvae may tunnel fruit, causing most damage. Fruit injuries are concentrated around the stem end, but tunneling may extend to the core. Activity and reproduction may continue year-round if conditions permit. Seven to eight generations per year are commonly produced in southern California.

A. Larva of a European grapevine moth. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

B. Banded sunflower moth larva. FRANK PEAIRS

C. Fruit surface injury produced by obliquebanded leafroller. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

D. Adult of the orange tortrix. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

E. Larva of the orange tortrix. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

F. Larva, pupa and damage to almond by navel orangeworm. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

G. Adult navel orangeworm. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

H. Omnivorous leaftier larva and injury to strawberry. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

I. Peach twig borer tunneling into peach fruit. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

J. Peach twig borer larva and injury to peach. EUGENE NELSON, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

K. Peach twig borer larva. ROBIN ROSETTA, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

L. Tomato pinworm damage to surface of tomato fruit. ALTON N. SPARKS JR., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, BUGWOOD.ORG

M. Tomato pinworm larvae exposed from leaf mine. JAMES HAYDEN, MICROLEPIDOPTERA ON SOLANACEAE, USDA APHIS ITP, BUGWOOD.ORG

ARTICHOKE PLUME MOTH (Platyptilia carduidactyla)4 is the most important insect pest of globe artichoke, but the insect is present over much of North America, where it develops in various thistles. Larvae may feed on all aboveground parts of the plant but create problems when they enter the leaves of the harvestable artichoke buds. This occurs when eggs are laid near buds and early stage larvae typically tunnel into outer leaves, progressively boring more deeply within the buds as they get older. Two generations per year are reported from Minnesota, three from California.

Adults are small yellowish-brown moths with unusual wings that are extremely narrow and held perpendicular to the body, giving them a T-shape. This appearance is typical of other members of the plume moth family (Pterophoridae), represented by some 150 species in North America, and it is the odd-looking adults that usually attract attention. Larvae feed on buds and seedpods and occasionally bore into stems of various plants, but rarely produce noticeable injury. A few species associated with cultivated plants include GERANIUM PLUME MOTH (Amblyptilia pica),4 which feeds on a wide variety of plants, occasionally damaging buds and flowers of cultivated geraniums and snapdragons; GRAPE PLUME MOTH (Geina persicelidactylus)4 which feeds on grape leaves, often feeding within a leaf fold of the terminal leaf; MORNING GLORY PLUME MOTH (Emmelina monodactyla),4 which feeds on leaves of various morning-glory family (Convolvulaceae) plants; and SNAPDRAGON PLUME MOTH (Stenoptilodes antirrhina),4 which develops in the buds, seedpods, and stems of snapdragon in California.

COTTON SQUARE BORER (Strymon melinus)5 develops on various legumes and plants in the mallow family (e.g., okra, cotton, hibiscus). Early-stage caterpillars feed on leaves, causing little injury. Older larvae may do some tunneling into pods of bean, okra, and other plants but are rarely abundant in gardens. Cotton square borer occurs throughout the U.S. and southern Canada but is abundant only in the southern U.S. The adult is an attractive butterfly known as GRAY HAIRSTREAK. Winter is spent in the chrysalis, with adults emerging in spring when host plants become available. Eggs are laid singly in plants. Young larvae feed on leaves, and older larvae concentrate more on reproductive tissues. Pupation occurs in a yellow or brown chrysalis marked with black spots. Two generations per year normally occur in the northern part of range and up to four in the south.

Larvae of the “YUCCA MOTHS” develop by feeding on the developing seeds of various Yucca spp.; however, the relationship between these insects and their host plants is mutualistic, as the adult moths are essential to the pollination of the plant. Yucca produce a sticky pollen that is collected by the yucca moths, which then actively move it to the floral stigmas, allowing pollination. At this time eggs are either inserted into the plant ovary (Tegeticula spp.)6 or laid on the pedicel or petals (Parategeticula pollenifera).6 The larvae that subsequently hatch eat a few of the seeds, but allow many to survive.

Most yucca moths are within the Tegeticula yucasella complex, which consists of 13 species, all of which develop into moderate-sized moths (wingspan typically ¾–1 inch) that are primarily white or light brown. Each is associated with only a few species of yucca, sometimes only a single species. The range of many has extended with the use of yucca in ornamental plantings, and some are presently found as far north as New England.

CITRUS PEELMINER (Marmara gulosa)7 produces meandering, serpentine-form mines under the surface of various fruits in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico It is most commonly observed on thinned-skinned citrus, but can develop in fruit of a very wide range of plants, including grape, walnut, and cotton. It can also occur as a cambium miner in twigs of oleander, willow, citrus, and other hosts.

1 Lepidoptera: Tortricidae

2 Lepidoptera: Pyralidae

3 Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae

4 Lepidoptera: Pterophoridae

5 Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae

6 Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae

7 Lepidoptera: Gracillaridae

A. External symptoms of injury by artichoke plume moth. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

B. Adult artichoke plume moth. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

C. Larva of artichoke plume moth. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IPM PROGRAM

D. Adult snapdragon plume moth. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

E. Damage to pods of snapdragon by snapdragon plume moth. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

F. Adult of the cotton square borer, the gray hairstreak. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Larva of a cotton square borer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Yucca moth. DAVID SHETLAR

I. Yucca moth feeding at flower. DAVID SHETLAR.

J. Exit holes made in yucca seed pods by emerging yucca moths. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

K. Larval tunneling of citrus rind by citrus peelminer. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

EUROPEAN APPLE SAWFLY (Hoplocampa testudinea)1 is an introduced species found from New England south to West Virginia and west to Ontario. An isolated infestation also occurs on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. This species can be a serious pest of apple fruit and also damages crabapple.

Adults become active around the time apple trees begin to bloom and are present for about 2 weeks. Females lay eggs in the blossoms, and the newly hatched larvae feed on the surface of the young apples. These wounds may cause fruit to abort, but if fruit remains, injuries develop as spiral scars on the skin. After molting, later-stage larvae tunnel into the fruit and ultimately feed about the core. A large exit hole is produced from which reddish-brown frass is continually expelled.

The larvae are pale brown with a dark head and very short appendages. They may feed on several fruits in a cluster before becoming full grown. They then drop to the ground and winter in a cocoon. Pupation occurs in spring, a few weeks before adults emerge.

RELATED SPECIES

A few native Hoplocampa species are associated with wild and cultivated cherry, including H. lacteipennis and H. cookei (CHERRY FRUIT SAWFLY). Cherry fruit sawfly is found in the Pacific Northwest, where it has also been reported to occasionally damage plum.

1 Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae

SCARAB BEETLES FOUND AT FRUIT AND FLOWERS

JAPANESE BEETLE (Popillia japonica)1 is an important insect pest in much of eastern North America and has recently become established in limited areas within some western states. Larvae are a type of white grub that chew roots of turfgrass and adults damage the flowers and foliage of a wide variety of plants growing in yards and gardens. Flower feeding by Japanese beetle is particularly common on rose and hibiscus.

FALSE JAPANESE BEETLE (Strigoderma arboricola)1 occurs widely east of the Rockies and is particularly common in the midwestern U.S. The adult is very similar in appearance to Japanese beetle but is slightly duller-colored and lacks the characteristic row of white tufts along the sides. Larvae feed on plant roots and are minor pests of potato, onion, grass, arborvitae, yew, and spruce. Adults are highly attracted to white and may cluster on white flowers during the brief period in early summer when they are active. False Japanese beetle is limited to areas of sandy soil and is known locally as “sandhill chafer” in parts of western Nebraska and eastern Colorado.

Adults of ROSE CHAFER (Macrodactylus subspinosus)1 feed on leaves and particularly blossoms of a wide variety of plants, producing skeletonizing injuries. Rose and peony are highly preferred. Various berries, peach, cherry, amur corktree, mountain-ash, grape, Virginia creeper, some birches, plum, cherry, and crabapple are other common hosts. Rose chafer contains a toxic heart poison, and birds can be poisoned by eating it.

A. Damage by apple sawfly. ERIC R. DAY, VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG

B. Mating pair of apple sawflies. KARL HILLIG

C. Apple sawfly larva. JOE OGRODNIK COURTESY OF NEW YORK AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION

D. Japanese beetle feeding rose. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. False Japanese beetle feeding on prickly poppy. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Rose chafer on rose hips. CLEMSON UNIVERSITY-USDA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SLIDE SERIES, BUGWOOD.ORG

Rose chafer is restricted to areas of the northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada where light, sandy soils are present. The larvae feed on roots of grasses and some weeds, apparently causing little injury. Adults emerge in June and live about a month. They are about ½ inch and more elongate than most scarab beetles, with gray or brown wings, a generally gray abdomen, and long orange legs. In the southwestern U.S. a related species is present, WESTERN ROSE CHAFER (M. uniformis), but it is rarely damaging.

ASIATIC GARDEN BEETLE (Maladera castanea)1 feeds on leaves and flowers of more than 100 different trees, shrubs, and flowers, including asters, dahlias, chrysanthemums, and roses. Adults are chestnut brown beetles, about  to ⅜ inch long that fly and feed at night. The Asiatic garden beetle is currently found over a broad area of the northeast, from Michigan to New England and southward to South Carolina.

to ⅜ inch long that fly and feed at night. The Asiatic garden beetle is currently found over a broad area of the northeast, from Michigan to New England and southward to South Carolina.

HOPLIA BEETLE (Hoplia callipyge),1 also known as “grapevine hoplia,” is a minor pest of certain flowers and fruits in many western states. Injury to white and light-colored roses is most commonly reported, but flowers of ceanothus, calla lily, California poppy, magnolia, lupine, and various legumes are also commonly eaten by adult beetles. Fruit clusters of grape are sometimes destroyed by this feeding, which usually occurs from mid-March through early May. Adults are about ¼ to ⅜ inch long and brownish or reddish brown with silvery scales on the back, providing a mottled appearance. Larvae feed on plant roots. One generation is produced annually. A related species in southwestern Canada that sometimes feed on flowers and small fruits is H. modesta; H. oregona has similar habits in the Pacific Northwest.

BUMBLE FLOWER BEETLE (Euphoria inda)1 is a moderately large, fuzzy scarab beetle. Adults are sometimes observed, often in small masses, at ooze from plant wounds and on fermenting fruit. Occasionally they damage flowers, including daylily, large thistles, rose, and strawflower. Larvae develop in decaying organic matter, preferring animal manures, and may be common in compost piles. Container-grown plants using fresh compost are sometimes infested by bumble flower beetle larvae, which may incidentally chew on roots. Bumble flower beetle is found throughout most of the area east of the Rocky Mountains. It overlaps in range with E. sepulcralis, which is restricted to eastern states. The COMMON FLOWER SCARAB, E. kerni, may be common at flowers in the western U.S., feeding on pollen of a variety of garden flowers.

Bumble flower beetle feeding on ripe grape. HAROLD J. LARSEN, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

Two species of very large, green June beetles in the genus Cotinus are sometimes found feeding on ripe, particularly overripe fruit. In the eastern half of the U.S., ranging into Texas and Kansas, the GREEN JUNE BEETLE (Cotinus nitida)1 is present. In areas of the southwestern states the related FIG EATER BEETLE (C. mutabilis) occurs. Larvae of both are a type of white grub that develop in decaying plant matter. Injury to turfgrass may occur as the larvae tunnel extensively through lawns, feeding little on live roots but disturbing soil and creating large surface mounds. In eastern North America, another large scarab that may be found feeding on leaves and fruit of grape is Pelidnota punctata,1 known variously as the “grapevine beetle” or “spotted pelidnota.” Larvae develop in rotting wood.

1 Coleoptera: Scarabeaidae

B. Hoplia beetle on rose flower. JACK KELLY CLARK, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM

C. Green June beetle on ripe fruit. DAVID SHETLAR

D. Euphoria kerni feeding on thistle pollen. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Bumble flower beetle in cardoon flower. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Spotted pelidnota. DAVID SHETLAR

SAP BEETLES AND OTHER FRUIT-DAMAGING BEETLES

Sap beetles (Nitidulidae family) are common around fermenting fruit, oozing wounds of plants, and areas of decaying vegetation. Most do not cause any direct injuries to fruit or vegetables but are attracted to overripe fruit and can be a nuisance. Some species may also be involved in movement of bacteria and fungi, notably spores of Ceratocystis fagacearum, the causal organism of oak wilt. Approximately 180 sap beetle species occur in North America. Most are oval to nearly rectangular in form and have distinctly clubbed antennae. Several species in the fruitworm beetle family (Byturidae) also damage fruits.

DUSKY SAP BEETLE (Carpophilus lugubris)1

HOSTS Maturing sweet corn, most overripe fruits and vegetables, and trees infected with various bacteria and fungi.

DAMAGE Unlike most sap beetles, dusky sap beetle can directly injure intact sweet corn ears. Larvae chew on the developing kernels, although there is rarely any external evidence of infestation. Dusky sap beetle has been involved in moving spores of the oak wilt pathogen to wounds of healthy trees.

DISTRIBUTION Throughout most of North America, common.

APPEARANCE Adults are about ⅛ inch and dull dark gray-brown with short wing covers, each having a light brown band at the base. Larvae are pale-colored, slightly flattened, with a brown head and a dark area on the hind segment.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Overwintered adults and pupae may be found in piles of discarded fruit, partially buried vegetable debris, or under the bark of trees with oozing wounds. Adults are active on warm days in early spring. At this time they feed and begin to lay eggs around decaying vegetation and on sap or bacterial ooze from damaged trees. Larvae can complete development in as little as 3 weeks, and pupation occurs in the soil. Two to three generations are probably produced in most years. Beetles are attracted to sweet corn shortly after pollen begins to be shed, at about the time that corn silk first begins to turn brown. Dusky sap beetle adults are present from early spring through November, with peak numbers often in late spring and midsummer.

OTHER SAP BEETLES

FOURSPOTTED SAP BEETLE (Glischrochilus quadrisignatus)1 is common in the northern U.S. and southern Canada. It is sometimes known as the “picnic beetle” because it is often attracted quickly and in nuisance numbers to ripe fruit, pickled vegetables, and fermented beverages during outdoor dining. It also commonly visits damaged or overripe fruits and vegetables in the field, and it may chew on the silk of sweet corn and readily invade cavities made by corn earworm and European corn borer. Adults are about ¼ inch and shiny black with 4 orange-red spots. G. fasciatus, another common species, resembles fourspotted sap beetle but lacks the distinctive spotting.

STRAWBERRY SAP BEETLE (Stelidota geminata)1 is a common pest of strawberry in the eastern U.S. It may aggregate in large numbers on ripening fruit, where the beetles feed and lay eggs. They can be important nuisance problems, particularly in pick-your-own operations. Adults are small (ca. ⅛ inch) mottled brown beetles. Strawberry sap beetle has a more restricted host range than many other sap beetles and is damaging only to strawberry. Two generations are typically produced annually.

1 Coleoptera: Nitidulidae

A. Dorsal and ventral views of the sap beetle Carpophilus ligneus. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

B. Sap beetles feeding on ooze from wound of honeylocust. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Dusky sap beetle adults and larvae in sweet corn. EUGENE NELSON, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

D. Dusky sap beetles massed on overripe melon. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. A “picnic beetle,” Glischrochilus quadrisignatus. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Larva of a Glischrochilus species sap beetle. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

G. Strawberry sap beetle. TOM MURRAY

H. Strawberry sap beetle larvae in strawberry. NATALIE HUMMEL, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY AGCENTER, BUGWOOD.ORG

RASPBERRY FRUITWORMS (Byturus spp.)1 are common insects associated with raspberry and loganberry throughout the northern U.S. and southern Canada. Adults of EASTERN RASPBERRY FRUITWORM (B. rubi) emerge in late April or early May, about the time leaves first emerge. They feed on the midrib of the unfolding leaves, resulting in ragged, elongate holes. They may then feed on the unopened flower buds and can destroy an entire bud cluster and further damage leaves in a skeletonizing manner. Eggs are laid on or sometimes in unopened blossom buds. The larvae then bore into the developing fruit and are distinctive in having two rows of light-colored, stiff hairs on the back. When full grown, the larvae drop from the plant and pupate in the soil. One generation is produced per year. The life history is likely similar for WESTERN RASPBERRY FRUITWORM (B. bakeri), common in western areas, and for B. unicolor, found in many areas of Canada.

Adults of the SPOTTED ASPARAGUS BEETLE (Crioceris duodecimpunctata)2 are commonly observed on ferns of asparagus. Larvae develop within asparagus seeds.

Adults of SPOTTED CUCUMBER BEETLE (Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi)2 (also known as SOUTHERN CORN ROOTWORM) feed on leaves and flowers of a wide variety of plants and occur widely across North America east of the Rockies. The overwintering stage is an adult that emerges early in the growing season, and there are subsequent multiple (often 2) generations produced annually, allowing the insect to be present throughout much of the year. In the western states it is replaced by the subspecies WESTERN SPOTTED CUCUMBER BEETLE, Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpuncta. Dahlia, peony, and hibiscus are among the flowers most commonly damaged by this insect. These insects also chew on the developing fruits and seeds of many garden plants, including green beans, tomato, eggplant, and, occasionally, some tree fruits (apricot, peach); however, cucurbit family plants—melons, pumpkins, squash, cucumbers—are particularly favored.

Western spotted cucumber beetle feeding on bean pod. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

A number of other closely related insects are also commonly associated with fruit and flowers of cucurbits, including STRIPED CUCUMBER BEETLE (Acalymma vittatum),2 WESTERN STRIPED CUCUMBER BEETLE (A. trivittatum), CHECKERED MELON BEETLE (Paranapiacaba tricincta),2 and WESTERN CORN ROOTWORM (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera).2 With the exception of the last, the larval stages of all of these also develop on the roots of cucurbits. Those larvae that do develop on cucurbits (“rindworms”) will sometimes move into the rind of fruit lying on the ground (“rindworms”), producing tunnels that scar and, often more importantly, wounds that allow entrance of decay pathogens. Larvae of the western corn rootworm develop solely on roots of corn, and the adults that emerge in early summer often concentrate feeding on green corn silk. However, they also favor feeding on blossoms and pollen of cucurbits and may be seen in co-occurrence with “cucumber beetles” in squash blossoms.

Striped cucumber beetle feeding on cosmos flower. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

1 Coleoptera: Byturidae

2 Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae

B. Larva of a raspberry fruitworm feeding in cap of ripe raspberry. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

C. Spotted asparagus beetle. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Spotted asparagus beetle larva feeding on asparagus fruit. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Spotted cucumber beetles, and one western corn rootworm, in squash blossom. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

F. Spotted cucumber beetle feeding on flower. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Corn silk clipped by western corn rootworm. DAVID KEITH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

H. Fruit scarring by striped cucumber beetle adults. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

I. Striped cucumber beetle larva on surface of melon fruit contacting soil. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

J. Checkered melon beetles feeding on sunflower pollen. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

K. Checkered melon beetle and striped cucumber beetles on surface of ripe melon. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

POLLEN-FEEDING BEETLES COMMON AT FLOWERS

Many types of beetles feed on pollen in the adult stage and may be conspicuous at flowers. In late summer and early fall, SOLDIER BEETLES (Chauliognthus spp.)1 are often commonly observed on flowers, particularly yellow-flowered plants such as goldenrod and rabbitbrush. These are moderately large beetles (ca. ½–¾ inch), predominantly yellow or orange and black, with soft forewings. Large numbers may be seen on particularly favored plants, with many—often most—coupled (male on top). Eggs are laid in masses in the soil, and the larvae develop as predators of insects that occur in or on soil. Common species in eastern North America include C. marginatus (MARGINED LEATHERWING) and C. pensylvanica (GOLDENROD LEATHERWING); C. scutellaris and C. basalis (COLORADO SOLDIER BEETLE) are common species in the High Plains States. Several other genera of soldier beetles also occur in North America that are predators in the adult stage, but the Chauliognathus species limit feeding to pollen.

Many BLISTER BEETLES2 also feed on pollen and nectar but may feed on flower petals, particularly of legumes. Most often observed are various black or gray Epicauta spp., including the ubiquitous BLACK BLISTER BEETLE (E. pensylvanica), a very common species east of the Rocky Mountains present on flowers in late summer. Other genera common on flowers include Pyrota spp., often brightly marked with yellow and black, Lytta spp., often with some metallic sheen, and Nemognatha spp., usually pale orange and with elongated mouthparts that allow them to extract nectar from flowers. Larvae of blister beetles develop variously either on eggs of grasshoppers or on bee larvae within nests of ground-nesting bees.

TUMBLING FLOWER BEETLES3 are small (ca. ⅛–¼ inch), wedge-shaped beetles with a distinctive “pintail.” They can make small, twisting jumps when disturbed, producing a tumbling that may allow them to escape predators. Most tumbling flower beetles observed in flowers are in the genera Mordella or Mordellistena, which are either predominantly dark gray or black and brown, respectively. Larval habits of the tumbling flower beetles are poorly known, but the family includes species that develop in decayed wood, as fungivores or predators, or in the pith of plants. In addition to flowers, where they feed on pollen, the adult beetles often collect on dead trees and fallen logs.

The ANTLIKE FLOWER BEETLES4 are small (ca.  –⅛ inch) beetles that rarely attract attention except when noticed within flowers. It is a large family of beetles, with more than 230 North American species, but those most commonly found in flowers are in the genera Anthicus, Ischyropalpus, and Notoxus; the last are distinguishable by a hornlike projection of the thorax that extends over the head. Larvae feed on decaying plant matter.

–⅛ inch) beetles that rarely attract attention except when noticed within flowers. It is a large family of beetles, with more than 230 North American species, but those most commonly found in flowers are in the genera Anthicus, Ischyropalpus, and Notoxus; the last are distinguishable by a hornlike projection of the thorax that extends over the head. Larvae feed on decaying plant matter.

Many kinds of SOFT-WINGED FLOWER BEETLES5 are common at flowers. Most conspicuous are Collops spp., which are about ¼ inch long, brightly patterned, with wing covers that do not completely cover the end of the abdomen. Collops adults do feed on pollen but are primarily predaceous on many small insects that may visit flowers. Other common genera of soft-winged flower beetles found on flowers are less distinctively marked and smaller, including those in the genera Trichochrous and Listrus, which are dark gray or mottled gray. Larvae of most soft-winged flower beetles are thought to be predators that live in the soil.

B. Mating pairs of the soldier beetle, Chauliognathus pensylvanica. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. Black blister beetle feeding on pollen. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Blister beetles, Nemognatha species. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Tumbling flower beetles. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. An antlike flower beetle. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Soft-winged flower beetles, Listrus species. DAVID SHETLAR

G. A soft-winged flower beetle, Collops quadriguttatus. DAVID SHETLAR.

SPOTTED FLOWER BUPRESTIDS (Acmaeodera spp.)6 are metallic wood borers that feed on pollen and are normally seen resting on flowers. Approximately 150 species occur in North America, most in the southwestern states. Most have some light-colored spotting and are slightly hairy. Larvae develop as borers within plants, but none are considered pest species.

Some longhorned beetles7 also visit flowers, particularly daisies, sunflowers, and other composites. Batyle suturalis and B. ignicollis are two species common over a broad area of central North America. Other “flower longhorns” commonly seen at flowers occur in the genera Typocerus, Leptura, and Crossidius. Although all of these develop as borers of plants in the larval stage, none are damaging to cultivated plants. However, some longhorned beetles that are pollen feeders are important as wood borers, notably the LOCUST BORER (Megacyllene robiniae)7 (page 440), commonly observed on goldenrod and other yellow-flowered plants in late summer.

1 Coleoptera: Cantharidae

2 Coleoptera: Meloidae

3 Coleoptera: Mordellidae

4 Coleoptera: Anthicidae

5 Coleoptera: Melyridae

6 Coleoptera: Buprestidae

7 Coleoptera: Cerambycidae

FRUIT, FLOWER, AND SEED WEEVILS

Adult weevils, or snout beetles, possess an elongated “snout,” at the end of which are chewing mouthparts. These are usually used to chew into plants, and larval stages of many species develop inside seeds, fruits, and flower buds. Weevils present in yards and gardens include representatives of three weevil families: Curculionidae (snout and bark beetles), Attelabidae (leaf-rolling weevils), and Brentidae (straightnosed weevils).

Many of the weevils that develop on seeds or fruit are known as curculios, a reference to the family name. Other weevils develop as borers of stems (page 362) or as root feeders (page 472), and a few develop on foliage (page 196) or as leafminers (page 216). The bark beetles (pages 350 and 452) are now also classified as a type of weevil.

PLUM CURCULIO (Conotrachelus nenuphar)1

HOSTS Plum, apple, and apricot are most seriously damaged, but peach, nectarine, quince, cherry, pear, hawthorn, wild plum, and native crabapple are also hosts.

DAMAGE Feeding and egg-laying wounds by adults produce scarring and distortion of developing fruit, often inducing premature fruit drop. This feeding is often characterized as a D-shaped scar on mature fruit. Wounds may provide entry for brown rot fungus. Larvae tunnel fruit of plum, peach, and apricot.

DISTRIBUTION Generally distributed over the eastern and midwestern states and eastern Canada. Localized infestations occur in parts of Utah, the Pacific Northwest, eastern Texas, and Oklahoma.

APPEARANCE Adults are generally gray to black snout beetles, about ¼ inch, with light gray and brown mottling. The wing covers are rough with 2 prominent humps and 2 smaller ones. Larvae, found in fruit, are legless, creamy white grubs with a dark head; they are about ⅜ inch when full size.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Adult weevils winter under covering debris in the vicinity of previously infested trees. They begin to move to trees when average spring temperatures exceed 55–60° F for 3–4 days, and migration continues for a month or more. When small fruits become available, females chew a small pit and insert eggs. They then make a crescent-shaped cut below the egg pocket, leaving a small flap of dead skin on the surface of the fruit.

B. The flower longhorn Batyle suturalis. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

C. The flower longhorn Typocerus velutinus. JONATHAN YUSCHOCK.

D. Feeding scars produced by plum curculio. DAVID SHETLAR

E. Plum curculio larva in sour cherry. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

F. Plum curculio adult. DAVID SHETLAR

Eggs hatch in about 1 week, and larvae feed in the fruit for about 3 weeks. In some fruit, such as apple, larvae survive poorly, apparently crushed by growing tissues. Larvae that develop successfully cut their way out and drop to the soil. They dig and produce a small earthen cell where they pupate. Adults emerge in 4–6 weeks. In most of its range, plum curculio has only one generation per year, and adults feed on maturing apples before moving to hibernation sites. Two generations are reported in Oklahoma and Texas.

ROSE CURCULIO (Merhynchites bicolor)2

WESTERN ROSE CURCULIO (Merhynchites wickhami)2

HOSTS Rose, particularly wild rose.

DAMAGE Rose curculio damages roses by making feeding punctures in flower buds, resulting in ragged flowers. During periods when buds are not common, feeding occurs on the tips of shoots, killing or distorting the shoots. A “bent neck” condition of rose, similar to that which rose midge may produce (page 582), can be caused by rose curculio feeding wounds that puncture developing stems.

DISTRIBUTION The rose curculio is the dominant species east of the High Plains, but it can be found in areas of western North America. The western rose curculio is usually the dominant species found in the Pacific States and east to Colorado and Alberta.

APPEARANCE Adults are about ⅕ inch with a pronounced dark-colored “beak,” which is longer on the males. In most areas the wing covers, thorax, and head are reddish and the remainder of the body black. In many western states, however, this species may have metallic green or blue-green coloration.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS Adults become active in late spring and lay eggs in developing flowers. The larval (grub) stage feeds on the reproductive parts of the flower. Blossoms on the plant, including those clipped off by a gardener, are suitable for the insect to develop. When full grown, the grubs fall to the soil and form an underground cell, pupating the following spring. There is one generation per year.

Wound produced in rose bud by rose curculio. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

OTHER SEED-, FRUIT-, AND FLOWER-DAMAGING WEEVILS

PLUM GOUGER (Coccotorus scutellaris)1 makes numerous feeding punctures on the surface of maturing plums, many of which result in a flow of clear ooze at the feeding site. Eggs are laid in some of the punctures, and the larvae develop in the pit. Adults spend the winter in the pit, and removal of infested fruit at the end of the season can help with control.

Oozing from feeding wound by plum gouger. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

APPLE CURCULIO (Anthonomus quadrigibbus)1 is found in the midwestern and eastern U.S. and eastern Canada. Damage to apple is infrequent, resulting mostly from feeding punctures that heal as sunken areas on the fruit. Larvae cannot develop in growing apple fruit, only in early-season dropped fruit. Development most commonly occurs in other hosts, notably amelanchier, hawthorn, and wild crabapple.

CHERRY CURCULIO (Anthonomus consors)1 is a minor pest of sour cherry and chokecherry in the Rocky Mountain region. Adults chew small holes in the base of flowers and cause abortion of developing fruit. The skin of older fruit is pitted by this injury. Eggs are inserted into fruit, and larvae tunnel the fruit, ultimately feeding on the pit. One generation is produced per year.

B. Rose curculio chewing into bud. JIM KALISCH, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

C. Flower petal injuries produced by rose curculio. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Bent terminal of rose resulting from rose curculio feeding wound. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Plum gouger. DAVID LEATHERMAN

F. Apple curculio. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Cherry curculio. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

H. Larva of cherry curculio in cherry pit. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

In the eastern states, STRAWBERRY BUD WEEVIL (Anthonomus signatus),1 also known as “strawberry clipper,” can damage strawberry, blackberry, and related caneberries. Adults emerge in spring as temperatures rise above 60° F and initially feed on buds of strawberry and redbud. Some later move to blackberry, raspberry, and dewberry as buds begin to swell on these plants. Small holes are chewed in the buds and an egg inserted. The female then cuts the stem just below the bud, which often drops from the plant. Each female lays about 20–30 eggs, mostly in April and early May. The summer-generation adults appear in early summer and feed on pollen before moving to winter shelters. Strawberry bud weevil is a small (ca.  inch) reddish-brown weevil.

inch) reddish-brown weevil.

PEPPER WEEVIL (Anthonomous eugenii)1 is a tropical species that occurs in parts of southern Texas, south Georgia, and Florida. Larvae tunnel the center of pepper fruit and feed on the seed mass. Adults are black weevils, about ⅛ inch, with a sparse covering of tan to gray hairs. Breeding may be continuous throughout the year, with fruit of nightshade an alternate host.

GRAPE CURCULIO (Craponius inaequalis)1 develops in the berries of grape grown in the southeastern states. Adults emerge in mid-June in Georgia and first feed on foliage, producing zigzag chewing wounds on leaves and petioles. They also puncture fruit to feed and lay eggs.

SUNFLOWER HEADCLIPPING WEEVIL (Haplorhynchites aeneus)2 clips the heads of developing sunflowers, coneflowers, and rudbeckia. The adults are shiny black to red-brown weevils, about ⅓ inch, and may first be observed on or very near developing flower heads in early July; females begin laying eggs a few weeks later. In the process of egg laying, females make a series of punctures in the stalk at the base of the flower head. This puncturing causes the stalk to break at the wound site and the head to hang from the stalk and wilt. Eggs are laid in the flower head and the grublike larvae develop while feeding on pollen and decaying tissues of the flower. In autumn they drop to the ground and burrow into the soil, where winter is spent. Pupation occurs in late spring of the following year. One generation is produced per year.

In the northern Great Plains, two species of small weevils develop in the seeds of sunflower: RED SUNFLOWER SEED WEEVIL (Smicronyx fulvus)1 and GRAY SUNFLOWER SEED WEEVIL (S. sordidus). Adults of red sunflower weevil move to the plants and feed first on the bracts of the developing head, then on pollen. When young seeds start to form, the weevils lay eggs inside them, and the grubs consume much of the seed interior while developing. In late summer they drop to the ground and dig a small soil cell, where they spend the winter in diapause. Pupation occurs the following year. Gray sunflower seed weevil is less damaging, as it lays fewer eggs and lays them earlier, beginning in the early to mid-bud stages.

COWPEA CURCULIO (Chalcodermus aeneus)1 develops within the seeds of several wild and cultivated plants, mostly legumes, but is particularly common in cowpea (Vigna spp.). Females chew into pods, lay an egg, and the grublike larvae then consume the developing seeds. Two generations are normally produced per year, and the overwintering stage is an adult. This insect is most abundant in the southeastern states but occurs north to New Jersey and into Kansas and Oklahoma.

A. Adult pepper weevil. ESTEBAN RODRÍGUEZ-LEYVA, POSGRADO EN FITOSANIDAD, COLEGIO DE POSTGRADUADOS, MONTECILLO, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM

B. Pepper weevil larva and damage. ESTEBAN RODRÍGUEZ-LEYVA, POSGRADO EN FITOSANIDAD, COLEGIO DE POSTGRADUADOS, MONTECILLO, COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA STATEWIDE IPM PROGRAM

C. Grape curculio. NATASHA WRIGHT, COOK’S PEST CONTROL, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Sunflower headclipping weevil. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Damage produced by sunflower headclipping weevil. DAVID SHETLAR

F. Sunflower headclipping weevil making puncture wound in stem of sunflower. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

G. Larva of sunflower headclipping weevil in sunflower head. DAVID SHETLAR

H. Larva of the red sunflower seed weevil. FRANK PEAIRS, COLROADO STATE UNIVERSITY

I. Gray sunflower seed weevil. FRANK PEAIRS, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

J. Red sunflower seed weevil. FRANK PEAIRS, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

K. Cowpea curculio. CLEMSON UNIVERSITY–USDA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SLIDE SERIES, BUGWOOD.ORG

L. Seeds damaged by cowpea curculio. GERALD HOLMES, CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY AT SAN LUIS OBISPO, BUGWOOD.ORG

About 30 species of ACORN or NUT WEEVILS (Curculio spp.)1 develop in the seeds of oak and various nut trees. Adults are usually brown, about ¼ inch with a prominent snout, particularly on the female. The legless grubs develop in the nuts and are a favored food of squirrels. The most important species is PECAN WEEVIL (C. caryae), often the most serious pest of pecan grown in the southeastern U.S. Hickory is also a common host. Adults are active primarily from early August through September. Adults feeding on young nuts can cause abortion and shedding of damaged nuts.

Females lay small packets of 2–4 eggs inside the developing nut, and the larvae subsequently consume much of the nut meat over the next month. When feeding is completed, they drop to the ground and dig a small cell in the soil, where they remain for 1 or 2 years before pupating. During winter a mixture of adults and larvae may be found.

Other economically important species include LARGE CHESTNUT WEEVIL (Curculio caryatrypes) and SMALL CHESTNUT WEEVIL (C. sayi), both associated with chestnut, HAZELNUT WEEVIL (C. obtusus), and FILBERT WEEVIL (C. occidentis). HICKORY NUT CURCULIO (Conotrachelus hicoriae)1 is common in acorns and hickory nuts. Nuts of black walnut grown east of the Great Plains are infested by BLACK WALNUT CURCULIO (C. retentus). Wounds produced by adults that chew into the developing nuts in spring are a common cause of June drop. Larvae feed on the developing seeds.

The cones of many species of pines growing in western North America may be consumed by larvae of the WESTERN PINE CONE WEEVIL, Conophthorus ponderosae.1 In late spring or early summer, the adults tunnel into the base of second-year cones, excavating the center of the cone where they then lay eggs. The larvae feed on the developing seeds.

Adult of a western pine cone weevil. JAVIER MERCADO, USDA APHIS ITP, BUGWOOD.ORG

HOLLYHOCK WEEVIL (Rhopalapion longirostre)3 feeds on the seeds, buds, and leaves of hollyhock. Small feeding punctures in emerging leaves and petals give the plant a ragged appearance. The larvae consume the seeds of the plant. Hollyhock weevils spend the winter in the adult stage, either in protected areas around hollyhock or in seeds. They move to hollyhock plants in late spring and feed by chewing small holes in the buds of the plants. During this time the weevils are commonly observed mating, the female being identifiable by an extremely long “beak.” As flower buds form in June, the females chew deep pits in the buds and lay eggs. The grub stage of the insect feeds on the developing embryo of the seed. After feeding is completed, it pupates in the seed. Adults usually emerge in August and September, but some remain in the seeds, emerging the following spring. There is one generation per year.

Hollyhock weevil larva developing within seed. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

1 Coleoptera: Curculionidae

2 Coleoptera: Attelabidae

3 Coleoptera: Brentidae

B. Acorn weevil chewing into acorn. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Acorn weevil larva. STEVEN KATOVICH, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

D. Pair of pecan weevils. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

E. Pecan weevil damage and larva. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

F. Chestnut weevil. DAVID SHETLAR

G. Larva of a western pine cone weevil. CANADIAN FOREST SERVICE, CANADIAN FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

H. Cone damaged by western pine cone weevil. USDA FOREST SERVICE-OGDEN, USDA FOREST SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

I. Pair of hollyhock weevils. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

The fruit flies (Tephritidae family) are a large group of flies that develop in fruits, stems, and leaves of plants. Adults have wings patterned with dark markings. Of the 290-odd North American species, only a few are seriously damaging to garden plants. Other flies that infest fruit include the gall flies (Cecidomyiidae) and the vinegar, or small fruit flies (Drosophilidae). The latter are particularly common on overripe fruit and occasionally are household pests.

APPLE MAGGOT (Rhagoletis pomonella)1

HOSTS Apple, pear, and large crabapples primarily. Late-season plum and cherry are infrequently infested, although some strains exist that prefer these hosts. Hawthorn is an important wild host in some western states.

DAMAGE Most damage results when the young maggots tunnel fruit, producing meandering brown trails that hasten rot. Egg-laying by the adults involves small puncture wounds (often called “stings”) to the fruit surface that cause dimple-like distortions.

DISTRIBUTION Primarily in apple-growing areas east of the Great Plains but has become established throughout much of North America, including isolated areas of the Pacific and Rocky Mountain states.

APPEARANCE Adults are picture-winged flies that have distinct black patterning on the wings. They are about ⅕ inch, generally black with a white spot on the back and a brown head. Larvae are cream-colored, legless maggots associated with the fruit. Pupae are pale yellowish brown, smooth, and somewhat seedlike.

LIFE HISTORY AND HABITS During winter, apple maggot is in the pupal stage, buried shallowly in soil near previously infested trees. Adults emerge in early summer, and females first feed for about 2 weeks on honeydew and other fluids in the vicinity of fruit trees. They then move to apple and begin to lay eggs, which they insert singly under the skin of the fruit. Peak egg-laying tends to occur in mid- to late July. Eggs hatch within a week. Larvae feed in the fruit for 3–4 weeks before dropping to the soil to pupate. One generation is produced per year, with the pupae remaining dormant until the following season.

RELATED FRUIT-INFESTING FLIES

CHERRY FRUIT FLY (Rhagoletis cingulata),1 also known as CHERRY MAGGOT, is an important pest of cherry in the north-central and northeastern U.S. and adjacent areas of southern Canada. Initial damage occurs when the adult female “stings” the cherry fruit with her ovipositor, producing small puncture wounds. Eggs are often laid in the punctures, and the immature maggots chew through the flesh of the fruit. Infested berries are misshapen, undersized, and mature prematurely.

Cherry fruit flies spend winter in the pupal stage around the base of previously infested trees. In late May, the flies begin to emerge and feed on fluids, including oozing sap from wounds made by puncturing fruit with their ovipositors. They feed for about 10 days before beginning to lay eggs. Females insert eggs under the skin of fruit for a period of 3 or 4 weeks. The immature maggots feed on the fruit, particularly the area around the pit. They become full grown in 2–3 weeks and drop to the ground to pupate. In most areas there is one generation per year.

BLACK CHERRY FRUIT FLY (R. fausta) has a similar life history and often occurs with cherry fruit fly in orchards. Pin cherry is the common wild host. WESTERN CHERRY FRUIT FLY (R. indifferens) is found in most of the western states and British Columbia where it develops on sweet, tart, and some wild-type cherries. Adults are present from June to August, most abundant often about the time of harvest.

B. Adult apple maggot. DAVID SHETLAR

C. Surface oviposition wound punctures made by adult apple maggot adults. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

D. Apple maggot larva in plum. WHITNEY CRANSHAW

E. Adult cherry maggot. TOM MURRAY

F. Mating pair of western cherry fruit flies. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

G. Western cherry fruit fly larva in cherry fruit. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

H. Western cherry fruit fly eggs laid under surface of cherry fruit. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

I. Western cherry fruit fly pupae. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

J. Western cherry fruit fly. KEN GRAY COLLECTION, OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

WALNUT HUSK FLY (R. completa) is native to the south-central U.S. but has become widespread throughout western North America. The maggots tunnel the flesh of walnut husks, which stains the nuts and reduces value. Uncommonly this species also develops in late-ripening varieties of peach.

BLUEBERRY MAGGOT (R. mendax) is distributed throughout the eastern U.S. and Canada. Larvae develop in blueberry and huckleberry. This species is mostly a pest of commercial blueberry. In the southeastern U.S., adults emerge in late May and persist until late July, when their native host, deerberry, is fruiting. Females lay eggs singly in fruits, and larvae take about a month to develop. The pupae subsequently overwinter, sometimes for a second year before adults are produced.

Blueberry maggot larvae and damage. JERRY A. PAYNE, USDA AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE, BUGWOOD.ORG

Adults of CURRANT FRUIT FLY (Euphantra canadensis)1 are generally yellowish with bright green eyes. Larvae develop in red and white currants and gooseberries. Eggs are inserted into the developing berries, and a red spot often develops at these oviposition wound sites. The larvae develop in the fruit, tunneling around the seeds, and become full grown about the time the fruit ripens. They then drop to the ground, dig into the soil, and pupate, the form in which they subsequently overwinter.

PEPPER MAGGOT (Zonosemata electa)1 is found in much of eastern North America and is native species thought to have originally been associated with horse nettle (Solanum carolinense). Cultivated peppers are damaged by adults when inserting eggs into the fruit surface, producing small dimpled wounds. More serious damage is caused by the larvae thatfeed on the flesh of the fruit core, producing brownish areas. Although widespread and fairly common, this species is rarely abundant and injuries are often overlooked. Only one generation is produced, and winter is spent as a pupa in the soil. Eggplant, tomatillo, and some wild nightshade weeds also host pepper maggot.

Pepper maggot larvae and damage. JUDE BOUCHER, UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT

Feeding at the base of florets and minor damage to seeds are commonly produced by SUNFLOWER SEED MAGGOT (Neotephritis finalis).1 Many other aster family plants may also be infested by sunflower seed maggot. Tunneling into the receptacle at the base of the florets may occur with Gymnocarena diffusa,1 which often pupates at the base of the head.