After decades of being the outcast stepchild of the investment world, futures trading finally has begun to catch the eye of mainstream investors. Perhaps it is the expanding need to diversify that is driving this trend. Or it could be that after the tech stock meltdown of the early 2000s or the credit crisis in the later half of the decade, futures may not look quite as risky or intimidating as they used to, at least in relation to everything else. Unlike stock in companies like Enron or Bear Stearns, commodities are physical products that people use every day. Regardless of what is happening in credit markets or corporate boardrooms, people will still drink coffee, eat wheat and fill their cars with gas. These assets will always have a value. In this day and age where anything goes in the investment world, that fact is beginning to carry a lot of weight with investors.

New volume records are being set on many contracts at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade. New products and the continued expansion of electronic exchanges continue to point to a thriving, growing industry.

Yet, despite the popularity of futures trading, the odds remain stacked against individual investors in the futures arena.

Studies confirm that about 76 percent of all futures traders end up losing money (there is no doubt that most of these are small speculators). It is no mystery why. It is amateurs against the pros in futures. No matter how hard small investors try, the pros are usually one step ahead. If you read something on your screen, they probably knew about it yesterday. If you read something in the newspaper, they probably knew about it last week. By the time you go to trade it, it’s already been priced into the market.

It is not the fact that small speculators don’t have the time, nerves, resources, capital, or knowledge to compete. It is all those facts. It is the fact that they are amateurs competing against professionals, and this is the real reason most futures traders lose money.

Lucky for you, you don’t have to be part of this group. You don’t have to go toe to toe with these heavyweights on their turf anymore. You can simply walk around the outskirts of this ongoing battle, picking up the spare change that rolls off to the side. You can sell options.

Before one can understand how to sell options on futures, one must understand futures themselves. Farmers originated the buying and selling of futures contracts as a way to offer a hedge against price changes in their crops.

It worked like this: A farmer has a crop of cotton growing in his field. He likes the current price that cotton is fetching at the market and would be very happy if he could sell his crop at this price. However, his crop will not be ready to sell for three months. By selling a cotton futures contract (or number of contracts) equal to the amount of cotton he has growing in his field, he can effectively “lock in” the current price of cotton.

How does this work? As an example, let’s say the farmer estimates that his crop will produce 50,000 pounds of cotton this year. The futures contract for cotton is for 50,000 pounds. Therefore, the farmer can sell one futures contract of cotton at today’s price for the month he expects his cotton to be ready for delivery. Now if the price of cotton falls between now and the time his cotton is ready to sell, he will make up the difference in profits on his futures contract. If the price of cotton rises, he will lose on his futures contract, but he will make up the difference on the sale of his physical cotton. It is a way for the farmer to avoid the risk of prices moving below a point at which he would be satisfied. This is called hedging, and it is still the primary purpose of the futures markets today.

Huge institutional farms and agricultural producers hedge their products in everything from cocoa to cattle to soybeans. Banks and government institutions hedge their exposure to currency fluctuations and interest rates. Worldwide brokerage houses hedge their exposure to the stock market with index futures contracts.

Hedgers also can be users of the actual products they want to protect against prices moving higher. A company such as Pillsbury, which uses thousands of tons of flour in a year, may want to protect against higher wheat prices and hedge by buying wheat futures. Financial institutions use futures to hedge in this manner as well.

Pure hedgers make no actual net profit from trading futures. It is only a tool to cut risk and manage price swings in a product that their business either produces or uses in some regard. Not only are these traders very well versed in their industry, but generally they also work for large organizations and have thousands or even millions of dollars in technical and human resources available to them to determine price directions and risk arrays of the commodities or financial instruments with which they are dealing. These traders are known as commercial traders, or commercials for short.

However, in order to hedge their risk, they have to have somebody assume that risk. Speculators fill this role. Speculators do not trade futures to manage risk or lock in prices. Usually, they are not even in the physical commodities business. They are trading the contracts purely for profit. They are willing to assume the risk of the hedgers in the hope that a price move will produce profits for them. They do not deliver the goods, nor do they take delivery. They simply buy and sell the contracts and exit before delivery comes due.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) divides speculators into two groups: large and small speculators. If a trader has a certain number of contracts in one commodity, usually 50 or 100, he is considered to be a large speculator in that particular commodity. While many individual investors easily can hold this many contracts at a time, large speculators generally are thought of as professional money managers or funds. Large investment houses or independent operators can trade commodity funds, made up of capital from many investors (similar to a mutual fund in equities). Ironically, some of these are known as hedge funds, supposedly because these funds can be somewhat of a hedge against adverse moves in the stock market. However, the purpose of these funds is to produce a profit.

Fund managers trade billions of dollars and trade many thousands of contracts in a day. They have the ability to move the market to a certain degree when they decide to enter or exit positions. Like commercial traders, most have huge amounts of resources available to them, industry contacts, and a wealth of personal or company experience to draw on.

There is one category left. This is the small speculator. Small speculators are individual investors. They are the tiny capitalists trying to enter the race between the two titans.

A futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell a specified commodity in a specified amount at a specified date. Every contract is for a specified amount of that particular commodity, currency, or financial product. Most commodities have different contract sizes depending on the unit that is used to measure it. For instance, a contract for corn is for 5,000 bushels of corn. A contract for crude oil is for 1,000 barrels of crude.

Unlike stocks, commodities trade in different contract months. Corn for delivery in July is a different contract at a different price from a contract for corn for delivery in September. As a speculator, you will want to close out your positions before these contracts come due for delivery.

Some investors new to futures express the fear that they will make some sort of mistake and that a contract for a commodity will be delivered to their door. This is simply unrealistic. There are several layers of people whose responsibility it is to make sure that this does not happen. You would be contacted by several of them (first and foremost, your broker) to inform you that it is time to exit your position, and if necessary, they probably would do so on your behalf. Even if you did intend to take delivery, there is much paperwork and arrangements to be made before this could take place.

Option traders generally do not have to worry about this.

Another difference between futures and stocks is how price moves are calculated. In a stock, you can buy 100 shares of stock, and if the price moves up $1 a share, you make $100. Since commodity contracts vary in size and units of measurement (i.e., barrels, bushels, or pounds), each commodity has a different point value.

For example, the size of a crude oil contract is 1,000 barrels. The price in the crude oil contract is quoted at a price per barrel. Price changes in crude oil move in 1-cent increments. Therefore, a 1-cent move in the price of crude oil equates to a gain or loss of $10 for every contract a trader holds (0.01 × 1,000 = $10). If a trader bought one contract for May crude oil at $98.00 per barrel, and the price increased to $98.50 per barrel, the trader would have made a $500 profit (50 × $10 = $500).

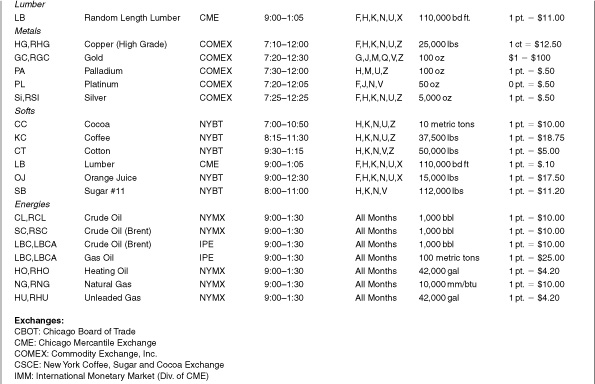

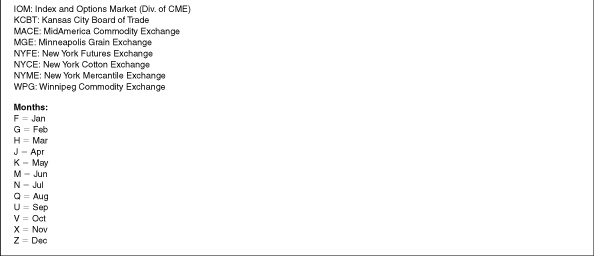

Contract sizes and point values for different commodities and futures contracts are listed in Figure 2.1.

The term margin has a completely different meaning in the futures world than it does in the world of equities. In stocks, one often can “borrow” money from the brokerage house to purchase stocks, at least a certain percentage of stock. This is known as buying on margin. The investor then has to pay interest on the money she borrowed and hope that the gain from her stock purchase is enough to pay her interest charge and commission and still show a profit. This is a way of increasing leverage.

In futures, buying or selling on margin is a built-in feature. To use the preceding example, a crude oil contract trading at $98 per barrel at a contract size of 1,000 barrels would mean that the total value of the contract is $98,000. Yet a trader can purchase (or sell) that contract for a small margin deposit, usually about 5 to 10 percent of the value of the contract. In the traditional way of buying stocks, to purchase $98,000 worth of stocks would require $98,000 worth of cash. However, to purchase $98,000 worth of crude oil, one only needs to put down the margin requirement, maybe $6,000. The exchange will front you the rest.

This is where the leverage comes from in futures contracts. A small move in the value of the unleveraged stock produces a small gain or loss. A small move in the value of the commodity can result in a large gain or loss. For instance, if you purchase 1,000 shares of stock at $98 a share, you plunk down $98,000. If the stock moves up to $102 per share, you make $4,000, or approximately 4 percent return on your investment (4,000/98,000 = .0408).

If you purchase a contract for crude oil at $98, put down your $6,000 margin requirement, and it moves up to $102, you make the same $4,000, yet your return on investment is 66.7 percent (4,000/6,000 = .667). This aspect of leverage is why futures generally are considered an aggressive investment by the mainstream investment media.

FIGURE 2.1 Futures Contract Specifications

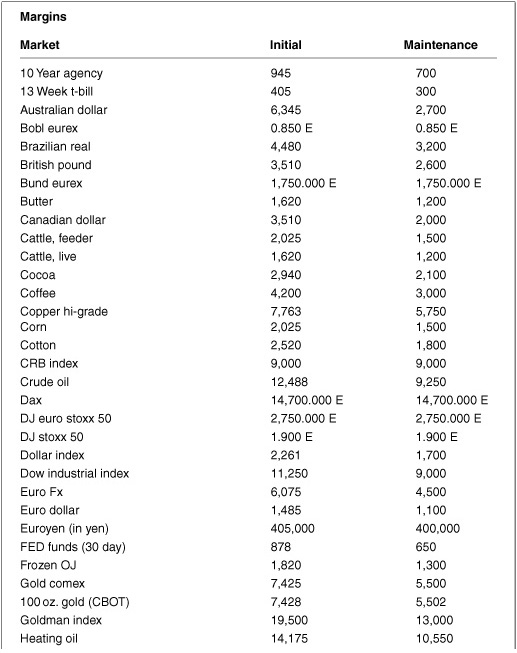

Figure 2.2 presents an example of what a margin sheet looks like. This is only a sample. Margins change all the time, and you should ask your broker for an updated margin sheet if you want to see current margins for futures contracts.

FIGURE 2.2 Sample Margin Sheet: Listing of Margin Requirements for Futures Contracts

Margin requirements for individual contracts are set by the exchanges and can be changed based on the volatility of the contract. These are called minimum exchange margins.

Individual clearing firms can add their own additional margin on top of the exchange margins and reserve the right to increase these margins without notice. Serious traders usually look for a brokerage that offers minimum exchange margins.

One reason that commodities are becoming more popular is that they offer a great amount of diversity to a portfolio. Most investors have much of their capital tied up in the stock market. If the stock market goes down, they lose money. Investors who trade individual stocks experience much frustration when they spend their time trying to pick the best-quality stocks only to lose because the market as a whole falls. They can pick the highest-quality companies on the board and still lose because of macroeconomic factors that take the whole stock market down.

Commodities, currencies, and other financial contracts are not necessarily affected by the stock market or the factors that affect its movement. In most cases they are moving completely independently of equities—sometimes perhaps even in opposite directions. For instance, talk of inflation may hurt stock prices but actually may benefit commodity prices. In addition, even if the prices of commodities are moving down, it is just as easy to go short in commodities as to go long.

Another reason that commodities are excellent diversifiers is that although, as a whole, prices can be moving in a long-term general direction, they are not as affected by the complex, as a whole, as much as stocks. In other words, Pfizer and Wal-Mart may move lower together because the whole stock market in general is down. However, the price of soybeans is fairly independent of the price of orange juice or natural gas. There are many more opportunities to diversify within the diversifier.

Nonetheless, trading commodity futures remains a losing game for most investors. For the reasons mentioned earlier, for most people it is simply too difficult to learn to manage the leverage and analytic skills, and acquire the resources necessary to be consistently successful.

So how does the average individual investor gain exposure to these potentially lucrative markets without losing his shirt? Many investors today are adopting the slogan, “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” Growth of managed funds in futures has exploded in the last five years.

Instead of trying to compete against the professionals, these investors are simply hiring a professional to trade for them. Although this does not guarantee a profit, most investors will fare much better over the long run having their funds managed professionally. Much of this will depend, of course, on the trader who is managing your money. There is more on this in the chapter on hiring brokers and money managers (see Chapter 15). The other choice, of course, is to learn to sell options.

Some investors even may want to combine these two approaches and hire a professional money manager who sells options to trade their account. This, of course, is a choice you may want to consider down the road as well.

Regardless, selling options, whether done by yourself or by your money manager, automatically relieves you of many of the burdens and pitfalls that befall not only futures traders but also traders who buy options. Selling options can put you above the crowd at a point where you don’t have to compete with the professionals in the futures pits—at least not directly. Achieving substantial returns in the futures market, consistently, can become a reality without taking outrageous risks. The next two chapters will explain how option selling works and explore some key terms and features of selling options that may make it preferable to other strategies available to you.