4. What needs to change?

Unaffordable housing is not a problem unique to New Zealand, nor is it new – the problems have been brewing for decades. And many of the solutions listed below have been proposed for an equally long time and widely discussed.

Despite this acknowledgement of the issues, the solutions have either not been implemented or not been implemented well – here and abroad. The UK, Australia and Canada, the countries we often look to for policy direction, have all had successive property booms that have led to severely unaffordable housing. In the UK the situation is so bad that it is described as a ‘tale of disaster’ and there are repeated calls to improve housing supply, tidy up rules around lending, reform taxes on housing and improve rental conditions.1 The 101frustrations experienced in New Zealand are, clearly, mirrored in other places.

New Zealand and many of the other countries with severely unaffordable housing have also faced the challenges of slow housing supply in the past, notably in the post-war period. Back then, the government response was highly interventionist. The state, either directly or through local authorities, built a great many houses. It also created housing assistance programmes to help more people into home ownership.

Such an interventionist approach is no longer consistent with the dominant political thinking that an economy should be based on incentives, competitive forces and a well-functioning market. This is a deep-seated belief, and the ideology has become theology. The response to a housing crisis is to insist that we must just get the incentives right and the market will respond. But, even if this is the case, it will take a long time for this approach to work – as we have seen from the last two and a half decades of slow house building. We also know from history that direct intervention, by building a large supply of new housing on under developed land or by increasing social housing, would meet many needs. But such intervention would not be a lasting solution as we still need the broader market to be responsive. Otherwise, the problems we have now will simply repeat in future.

102In New Zealand, as elsewhere, the ultimate difficulty in tackling the housing market lies in finding the political consensus and the necessary persistence to push through changes that may adversely affect current property owners (including those with significant political influence), in favour of a more equitable situation for future generations (who do not yet vote and have little representation). Abraham Lincoln summed up this task in 1858 thus:

In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed.

If we are to solve New Zealand’s housing crisis, the public must be united in its understanding of the issues, the outcomes being sought, and the policies that will be needed to bring about a solution.

Without a shared vision and common purpose, fractured politics will lead us down a path that pits one generation against another. We need to have a mature conversation about what values we favour, what we plan to do and how we will stick to that plan, because the solutions will take a generation to implement. They will also be complex, because they have to increase housing affordability over time, acknowledging that home ownership is important to New Zealanders, while simultaneously 103improving rental conditions for those who choose to or are forced to rent long term.

To expect an easy and quick solution is delusional. Sadly, much of the public debate centres on one quick fix, such as banning foreign investment or limiting immigration. Equally, however, to despair of the task, to argue that it is too hard and that we can do nothing, is a road to ruin.

To expect our political leaders to do the right thing is of course ambitious. Since the 1990s, successive governments of various political leanings have presided over a long erosion of housing affordability. Courageous leadership on housing is clearly needed, but remains absent. Politicians at once want to increase house prices in order to satisfy home owners, and lower them in order to please renters wishing to buy. (The average member of Parliament owns at least two homes.2) As a result, current housing policies tend to favour home owners and rental investors. Banks are also a powerful lobby group and, as institutions that invest heavily in mortgages, their main aim is to see house prices rise. Several banking chief executives have publicly denied that there is a housing bubble at all.3 Young people, many of whom have disengaged from parliamentary democracy (in the 2014 election, just over half of non-voters were aged under forty4), lack a strong voice in political discourse and are disadvantaged 104by New Zealand’s housing policies. The interests of future generations, those not yet born or too young to vote, are arguably not represented at all. So if we are to expect leadership on housing, those New Zealanders who are engaged will have to understand the issues better and use their political power. Renters now make up more than half the country: that is a powerful constituency for change. Our aim in this book is to inform that growing desire for change with our understanding of the issues, consequences and solutions.

Since our housing problems have been caused by many different factors, accumulating over time, they cannot be fixed by a single policy change. There will not be ‘one solution to rule them all’. The first set of solutions – palliative in their nature – will be to provide better and more sustainable living conditions for Generation Rent. The second set will take the heat out of the housing market in the current cycle, by using levers to control demand: raising interest rates, reducing credit availability, creating a more responsive construction sector and perhaps restricting migration and limiting foreign buying. But these cyclical measures, though useful, will only buy us time. Throughout the cyclical ups and downs, prices have steadily trended upwards because of underlying policy errors. The real fixes, and the hard work, will be in correcting structural problems: slow land supply; expensive 105infrastructure provision and a broken model for its funding; taxes that favour housing; and policies that encourage banks to lend more for individual property investment.

Below, we offer ten ideas that could improve the housing situation – changes that we, as citizens of New Zealand, demand from our politicians. We have space here only for sketches of the policies. But these should still help the reader think through the policy options and the results they could have. Implementing these proposals in ones and twos, however, will not help. They need to be delivered as a package – only then can we begin to relieve the accumulated pressures of the broken policies of many decades.

Our policy ideas can be summarised as follows:

Palliative care

1. Fix the rental market and change attitudes towards renting and property investments

2. Build more houses

Short-term cyclical solutions

3. Use monetary and macro-prudential policy to rein in the market

4. Clarify immigration policy

5. Improve data collection to identify the impact of foreign buyers, and act on this issue if they are proven to be fuelling housing unaffordability

106 The real deal: structural solutions

6. Increase the supply of housing in high-demand areas, be open to changes, deal with Nimbys and create sustainable funding arrangements for infrastructure

7. Reduce the easy supply of money for housing by reforming banking regulation

8. Clarify the existing tax rules on property investment and have an open discussion on negative gearing and ring-fencing income from investment properties, and imputed rent

9. Improve financial markets and financial literacy to provide an alternative to investing in property

10. Improve the scale, productivity and resilience of the construction sector to make building companies more responsive to changes in economic conditions.

Solution 1: Fix the rental market

One way we can improve the quality of life for renters is by fixing rental rules. More people than ever are renting, yet New Zealand has one of the weakest tenant protection systems in the world, on a par with the UK and Australia. Fixing this will make life better both for people who have effectively been ‘forced’ into renting and for those who want to be renting. Doing so would also lessen 107the pressure on young people to buy a home, and therefore reduce some of the demand for home ownership that pushes up house prices.

The first thing that New Zealand needs is more rental properties with longer-term leases. Leases currently tend to be short term, with more than half of tenancies lasting only ten months.5 In comparison, owner-occupiers spend an average of seven years in their home. Short-term leases can make tenants feel insecure in their rental properties and, ultimately, make it difficult for them to feel at ‘home’.

In New Zealand, rental agreements can be either periodic or fixed-term agreements, with periodic the most common. With a periodic lease, a landlord can give ninety days’ notice to remove a tenant from the premises, but this can be shortened to forty-two days if the landlord sells the house or needs it for the use of a family member or an employee. Since housing in New Zealand is an investor’s market, tenants are often in rental properties from which they could be evicted at short notice because the landlord has decided that now is the right time to sell.

On the other side of the ledger, if tenants want to move out, they only have to provide twenty-one days’ notice under a periodic lease agreement. This does not leave much time for landlords to fill the vacant property.

108In addition, the New Zealand rental sector lacks leniency towards alterations and pets. These are things that are important to people and can help change a house into a ‘home’. But having pets in the house and making minor alterations, like painting a wall or changing the carpet, both generally need consent from the landlord. By contrast, in many European countries alterations are expected, much as they are in the New Zealand commercial property market. In these kinds of contracts, you are effectively renting the shell of the place and what you do with the interior is up to you. When you leave, you are usually asked to put it back the way you found it.

New Zealand’s tenancy laws may have been suitable when they were first made, when renters were mainly young people who did not require as much security of tenure. Today, however, it is increasingly common for older people and families with children to rent. Families with children need longer term security for schooling purposes, while older people need stability because they are less mobile and it is harder for them to move their belongings physically. Young people without children may also value longer term security.

As well as tenure length, we have to look at the quality of rental housing. Just like owner-occupied housing, much rental housing is of poor quality. However, the rental housing stock also tends to be 109older than the owner-occupied stock.6 New Zealand Herald columnist Lee Suckling’s experience is all too common:

At every viewing you’ll be one of at least 20 people. You’ll wait patiently outside, eyeing up the competition, then will line up like sheep, shoes off, ready to file in five-at-a-time. The reality is never as good as what TradeMe presents … If you’re looking in a city-fringe suburb, you will be met with grottiness. Auckland landlords, you seriously need to have your houses professionally cleaned. Last time we checked, $500 a week didn’t buy us mould.7

While some landlords are experienced, many are amateurs. Few are large-scale landlords or institutions managing many properties. In contrast, in countries such as Germany, there are many institutions involved in managing property, which lifts the overall quality of property management. Many landlords in New Zealand are in the business solely for the capital gains, and maintenance of properties is therefore beyond their experience and their interest.

For landlord-tenant relationships to succeed, there need to be rules clearly defining what is required from both parties when it comes to the operational, day-to-day aspects of renting. This includes the expectations of both parties – for example, what state the rental property should 110be in, how quickly and what type of repairs should be done, or what state the tenant should leave the property in when they vacate it.

What landlords want

Landlords invest in property to get returns on their investment, both from capital gains and from rental yields. For many landlords, rental property is a business investment and a major source of retirement savings.

Many landlords prefer long-term tenancies because these provide a guaranteed income from rent. Landlords lose out when properties are vacant between tenancies because they still have to cover costs such as the mortgage, maintenance, insurance and rates, but they are getting no income to pay for these. Periodic tenancies contain the risk that a tenant may leave suddenly and the landlord will have to find another one very quickly. As noted above, tenants only have to give twenty-one days’ notice that they intend to leave.

At the same time, landlords would like to spend less time managing tenants. Some landlords struggle with tracing tenants to recover rent left unpaid after their departure from a property.8 Landlords also say it is difficult to judge the character of a tenant, and they cannot access information they would like to have, such as whether a potential tenant has paid their rent on time in previous properties.9 There 111also needs to be adequate protection of landlords’ property. International evidence suggests that homes depreciate by 1.5 per cent more per year if they are inhabited by renters rather than by owners (who work harder to take care of their most important asset).10

A balance needs to be found to meet the needs of both tenants and landlords, to make room for more households with security of tenure. While short-term leases are still necessary and appropriate for some members of the public, there needs to be greater availability of long-term leases. Among the many benefits for both landlords and tenants of long-term tenancies is the fact that tenants get to feel settled in their house. Landlords also get secure income and tenants who treat their property with care because they feel like the property is their home. With a lower turnover of tenants, there is also less damage to the property, because furniture is not moved in and out so often.11

Germany and Switzerland set a good example for rental markets

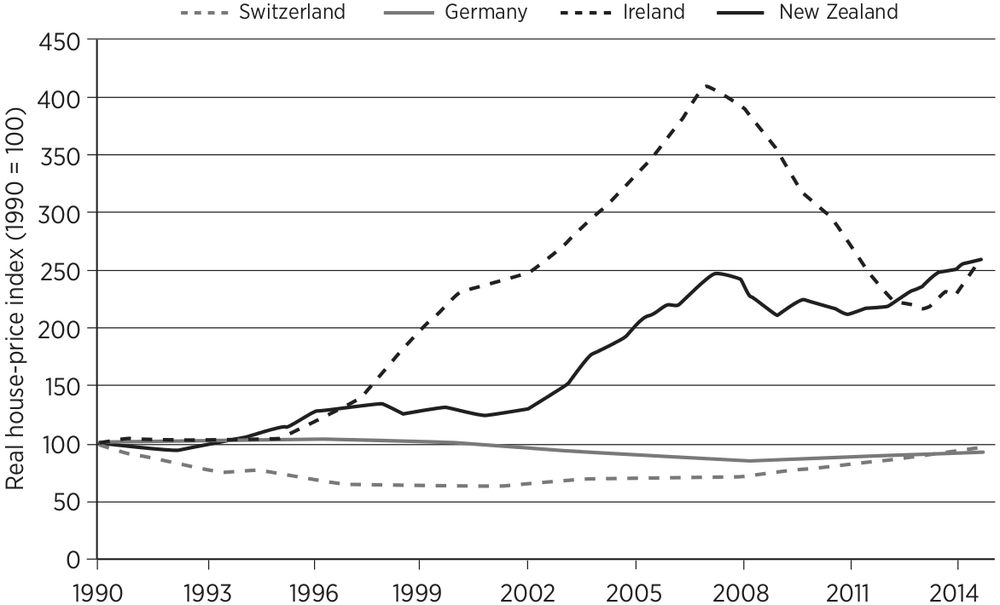

New Zealand can learn from Germany and Switzerland when it comes to levelling the playing field between renting and owning. As shown in Figure 4.1, house prices in those two countries have not increased as they have in New Zealand or Ireland – rather, they have only just kept pace 112with the cost of living. Houses in Germany and Switzerland are a hedge against inflation but not a speculative wealth generator.

Figure 4.1 Real house prices in selected countries

Note: Figure 4.1 shows the evolution of house prices in New Zealand, Ireland, Germany and Switzerland, with the effect of inflation or general prices removed. The prices are shown indexed to 1990. This way we can see the cumulative increase in real house prices since 1990 in each country. New Zealand and Ireland have both had massive housing booms, although these were different in nature. In Germany and Switzerland, where home owning is relatively unusual, and there are other significant differences in regulations and culture, real house prices have been broadly stable.

Source: From dataset described in Adrienne Mack and Enrique Martínez-García, ‘A Cross-Country Quarterly Database of Real House Prices: A Methodological Note’, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper No. 99, December 2011 (revised June 2014), www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/institute/wpapers/2011/0099.pdf (accessed 19 May 2015).

In Germany most people rent: at 57 per cent, the country’s rental rate is the second highest in Europe (with 90 per cent renting in Berlin).12 There 113are several reasons why this rate is so high. On the supply side, there is a good stock of high-quality rental accommodation that is of no lesser quality than owner-occupied housing. Rental properties are provided by both amateur landlords and institutions, with the former owning 60 per cent of rented housing units.13 Amateur landlords can vary in experience, but having institutions in the mix at least means there are some very experienced managers of residential properties able to fix major issues.

In New Zealand, most amateur investors are motivated by capital gains, rather than the income from rents. Around 41 per cent of landlords in New Zealand are accidental landlords who do not even know what features tenants may be looking for.14 They differ from professional landlords and institutional investors, who buy future rental income and hold on to properties for a long period – and are more focused on tenants’ needs.

On the demand side, renting in Germany is socially acceptable and not seen as inferior to owning a house. Germany has a strong history of renting dating back to its nineteenth-century period of industrialisation. At that time, large stocks of rental houses were built for industry workers, located close to their workplaces so they could minimise their commute between home and work. Even after losing housing stock during the 114Second World War, the Government prioritised rental properties in its rebuild.

Another reason for Germany’s high proportion of renters is that access to finance to buy a home is not as easy as it is in New Zealand. German banks have stringent lending requirements.15 For mortgage lending, either a 20 per cent deposit or substantial collateral is normally required. The banks also need firm proof of earnings from a multi-year period.16

Strong tenancy laws in Germany

Germany has tenancy agreements that give tenants greater protection in comparison to New Zealand. German laws are more favourable to tenants and make it easier for single people and families alike to settle into a rental property for the longer term, without the fear of being kicked out at short notice.

The most common type of agreement in Germany is a tenancy of an unlimited length. Landlords must give between three and nine months’ notice to evict a tenant, and can only do so with good reason. The amount of notice needed increases the longer the tenant has lived in the property. Three months is the minimum for someone who has lived in the property for less than five years; six months is required for a tenancy of five to eight years; and nine months’ notice is needed for those who have lived in the property more than eight years.

115Landlords must also have a very good reason to evict a tenant – for example, if they need the premises for their own or their family’s use, or if the lease contract prevents them from making fully economical use of the premises. If a landlord is going to suffer severe financial difficulties, for instance when a building is damaged beyond repair and needs to be torn down, an eviction would be accepted. In contrast, a desire to obtain a higher rent for the property or a simple decision to sell it do not constitute good reasons for eviction.17 German laws do not enable property speculation in the same way as New Zealand laws, which, as discussed above, allow landlords to evict tenants quickly if they want to sell. German rental investors must abide by stringent rules and cannot remove tenants quickly in order to take advantage of higher house prices. It is for these reasons that German house prices have barely kept pace with general prices since 1990.

German laws on alterations and pets are also much more relaxed. Pets are allowed and minor alterations are permitted and considered normal. When renting in Germany, tenants are essentially paying for the shell of the building; even light fittings are not necessarily provided. People moving into a German flat generally find that the interior walls have been freshly painted in white by the previous tenants, so as to give them a blank 116canvas, and generally they themselves must repaint in white when it is their turn to vacate the flat.

Long-term tenancies need strong laws on rent increases to provide security to tenants. For this reason, rent increases are restricted in Germany. If a landlord tries to increase rents by more than 20 per cent over three years, he or she will be fined.

In Switzerland, meanwhile, the majority of households live in rented apartments or houses. In 2010, the home-ownership rate was just 37 per cent. Unlike in Germany, renting is often not by choice; more commonly it is due to house prices being very high relative to household income and wealth. This is in part because supply is constrained by Switzerland’s topography.18

As a result, housing conditions in Switzerland favour renters. Owner-occupied dwellings are heavily taxed, making owning less attractive. Renting is supported by the government: in some cantons (districts), rent payments can be partially deducted from income for the purposes of income taxes, and a small percentage of renters benefit from subsidies. In terms of the quality of the property, rental and owner-occupied housing rates about the same.

Swiss laws also contain strong protections for renters. Leases are either indefinite or periodic. Landlords must give between three and six months’ notice and have good grounds for evicting a tenant. 117Terminations of a lease are possible if the landlord has a serious motive and does not violate good faith. For example, evictions in ‘revenge’ for a complaint made by a tenant would not be allowed.19 If the landlord is simply looking to exercise their right over the property or is claiming changed family circumstances, the eviction can be contested by the tenant.20 Pet ownership is common and so are alterations. People wanting to make alterations, however, generally ask the landlord first, because they may be asked to restore the property to its original state when they leave.

Lessons for New Zealand

New Zealand’s typically short-term leases for rental properties, combined with other conditions discriminating against renters, do not make renting an adequate alternative to home ownership. And changing this situation will not be easy. People are often affected by ‘status quo bias’, a fancy name for inertia, which causes them to accept the status quo or default option, even if they do not actually have a strong preference for it.21 We see this whenever we are presented with options for car features or cell phone settings, for instance – most people will simply go with whatever is the standard or default option.

This implies that one of the best ways to move towards more long-term leases would be to change 118the default option. This technique is already used in KiwiSaver, for example, where people are automatically enrolled in an investment scheme and have to actively opt out if they do not want to be in one. The technique is known in policy circles as ‘nudging’, because it encourages people towards a certain option that policy-makers have decided is desirable, but still allows them the freedom to choose other options if they really want to.

When it comes to tenancy laws, the government could change its template tenancy agreement to include a standard tenancy term of three years (for example). If a landlord or tenant wanted a different length of term, they would have to actively choose to deviate from the template. If introduced in this way, longer tenancies would probably become gradually accepted, and the average length of tenancies would increase over time. But it would preserve the current flexibility and the ability for tenants and landlords to sign short-term agreements if that is what suits them.

New Zealand also needs to reconsider its laws regarding notice periods for tenants and the reasons for eviction. The notice period of forty-two days simply provides too little security for tenants who want to settle in a particular area, raise a family or make their house a proper home. It should be made longer, following the lead of the German or Swiss model. Similarly, the law should 119be changed so that the standard tenancy agreement allows tenants to make alterations such as painting walls, hanging up pictures or changing the carpet. However, the law should also stipulate that, when leaving a property, tenants must return it to its original state unless their changes are accepted by the landlord. In combination, these changes would give tenants much greater ‘ownership’ of the property, despite not having equity in it, while preserving the landlord’s ultimate control of the asset.

Changing attitudes towards renting and investment property

Renting in New Zealand is often viewed as an inferior and short-term option, something done during student days before one can buy a home. Renters are sometimes stigmatised, having to deal with disbelief that they are ‘still renting’ and the widespread view that they are financially insecure or even wasteful. The majority of New Zealanders now live in rental properties. Renting is not a minority issue anymore. Yet people with vested interests in property, such as property organisations and banks, continue to reiterate the superiority of home ownership.

We have to remove the stigma from renting and make it a valid option for any household, as it is in Germany and Switzerland. Doing so requires us 120to confront our cultural belief that home owning is implicitly a requirement of ‘growing up’ and ‘making it’. The reality is that no matter what is done to improve housing affordability, the situation will not change overnight, and increasingly large numbers of people in the 30–50 age bracket are going to rent. We should be making it easier for families to be renters, and part of that involves thinking and talking about renting in a positive way, so that they no longer feel stigmatised.

Another benefit of de-stigmatising renting is that it would encourage more top-flight property managers into the rental property market. As noted above, Germany has a large number of institutions supplying rental housing, as well as private landlords. If more people were willing to rent long term, more of these types of companies would enter our market.

One of the prevailing myths about renters is that they must be financially insecure because they do not have investment in the form of a house. This belief stems from the fact that investing in housing is the main means of accruing savings in New Zealand. If you are not either a home owner or on the way to being one, in many people’s eyes you are not saving for retirement. The solution here is to reduce the dependence on housing as a form of investment. That will require changing the favourable tax treatment of housing and increasing 121the attractiveness of other investment options, ideas for which are set out below. It will also involve improving financial literacy.

Another strongly held myth about renting is that when a person rents, they are ‘throwing their money away’ or paying someone else’s mortgage. This is simply untrue. Because house prices have risen so much in Auckland, rents are barely equal to the usual outgoings of rates, insurance, and maintenance – let alone mortgage payments. These combined costs amount on average to almost twice as much as the costs of renting. If a renter saves the difference between what mortgage payments would be and what they pay in rent, they are clearly saving, and can invest the difference in other areas.

Solution 2: Build more houses

The history of the past century includes periods of significant population growth that led to equally significant housing pressures. One very good example is the post-Second World War period, which had been preceded by a long period of under-building and was suddenly faced with sharply increased demand due to population growth. The solution at that time was simple: the government got involved and built on a large scale.

To repeat such an exercise today would court controversy, as discussed at the start of this chapter. In our current economic thinking, the 122orthodoxy is that we should do no more than have the right regulations in place for markets and the economy to function smoothly. To explicitly ask the government to step in and build houses and related infrastructure flies in the face of current thinking. Yet the situation is dire. New Zealand house prices are among the highest in the world relative to our incomes. Prices are clearly signalling that, one way or another, demand exceeds supply. In theory, this increase in prices should have led to an increase in supply, thus bringing prices down again. But neither of these two things have eventuated – housing construction is slow, and prices are becoming increasingly and severely unaffordable. This is because of the structural policy failures we discussed earlier in this book and for which we propose some solutions later in this chapter.

Because the market is not responding as theory suggests it should, there is a role for government-initiated house building. This is of course a highly complex issue, and the merits of government building schemes aimed at the general market – such as the Labour Party’s KiwiBuild plan to construct 100,000 new ‘affordable’ homes – are hotly debated. We do not have space here to get into the full complexities of this debate. But we can single out what we think are a couple of specific – and more limited – initiatives that are worth pursuing.

123First, a large-scale central government programme to increase social housing stock (which has a significant waiting list and faces severe mismatches between the types and locations of houses available and what people actually need) may relieve some pressure on the private rental market and increase total housing supply. (Social housing was discussed in Chapter 3.)

Second, local government could also reassess the best use of its land holdings. For example, Auckland Council owns the land for thirteen golf courses. Could some of them be repurposed into well-designed, medium-density, mixed-use housing developments? And might not the returns (both economic and social) from these developments be greater than those from the golf courses? Local government may also need to evaluate which of its designated ‘heritage’ sites truly merit their protection and which ones can be built over. Buildings that can still be used should not be torn down, but not every functional building is worth retaining solely for aesthetic reasons.22 As this book was being finalised the government announced plans to examine all Crown-owned land in Auckland for possible housing development, including parcels of land owned by tertiary institutions, health boards and the Department of Conservation.

A direct intervention in the form of government 124investment in new housing would not solve the fundamental issues that have led to a long-term decline in affordability. But a large injection of new homes that addresses other priorities such as providing social housing, and repurposes poorly used council-owned land, would help relieve the pressure while the slow work of fixing the fundamentals takes place.

Solution 3: Use monetary and macro-prudential policy

It is possible to manage demand by changing interest rates or other conditions that affect the price or the quantity of debt. Such measures are there to manage the cycle, not resolve the underlying pressures. Still, they can help to even out the highs and lows.

The Reserve Bank has traditionally addressed these highs and lows through the medium of the Official Cash Rate (OCR), the rate at which it lends to commercial banks. Raising the OCR makes it more expensive for banks to borrow from the Reserve Bank, and they increase the cost of lending (including floating mortgage rates) accordingly. This reduces the demand for mortgage borrowing – but also for everything else. After all, the Reserve Bank is mandated to manage the overall economy, by targeting general inflation, not house prices per se. So when house prices are rising sharply, 125but other parts of the economy are growing only moderately and other prices are not rising much, the Reserve Bank does not want to raise interest rates and punish the entire economy – this would be the proverbial cutting off your nose to spite your face. Consequently, the bank is hamstrung in its ability to contain house prices. We see this now, in mid-2015, when the buoyant housing market means the Reserve Bank is unable to lower interest rates despite low inflation and high exchange rates – things that would otherwise trigger an interest rate cut. In other words, the Auckland housing market has been holding the rest of New Zealand to ransom.

Fortunately, the Reserve Bank, like other central banks around the world, is looking at adding other measures to its ‘toolkit’ to manage specific parts of the economic cycle. These are technically known as ‘macro-prudential tools’ – essentially, they pull the ‘prudential’ levers that manage risk in the financial system, and thus reduce risks within the wider economy.

The Reserve Bank has already flirted with one measure, restricting the amount of high-leverage lending by banks through the loan-to-value (LVR) limits for first-time buyers. But this has not stymied the rapid increases in house prices. In fact, this is unsurprising, since much of the buying in the housing market is done by people who already have 126a stake in it – investors with many properties or people trading up or down. While the idea of LVRs is a good one, the execution is difficult, in part because these interventions have to be finely honed to be effective. As discussed earlier, information from market insiders suggests the LVR restrictions have restricted buyers in the regions but have been ineffective in Auckland – the very market that they were meant to dampen. The LVR restrictions are also effectively at odds with the Government’s home loan grants and KiwiSaver grants to first-home buyers. Under these schemes, households meeting a certain income threshold can apply to get assistance, which may get them ‘over the line’ in terms of the deposit restrictions.

In May 2015, the Reserve Bank took a further step to tackle the housing market by restricting lending to investors. Effective from October 2015, investors must have at least a 30 per cent deposit if they are to buy in the Auckland Council area. At the same time the Reserve Bank relaxed restrictions for other parts of New Zealand. It also introduced a definition of an investor as someone who doesn’t live in the house they are borrowing the money to buy. This contrasts with the definition in our tax regulations, where an investor is someone who intends to benefit from capital gains. The Reserve Bank’s policy, which was not yet implemented at the time of writing, is certainly novel. We don’t 127typically have different rules for different parts of New Zealand, in part because fragmenting policy across a small population of only 4.5 million people generally entails more costs than benefits. But the Reserve Bank is cornered. It can’t use its traditional methods because they simply are not working.

Looking further ahead, the Reserve Bank has a range of other tools it could use, including imposing loan-to-income ratios and debt-servicing ratios, asking banks to hold more capital against all lending, and asking banks to treat housing investors differently by holding more capital against their loans specifically. These policies are untested, but they may be worth trying in order to take the edge off the sharp peaks and troughs in the cycle.

Ultimately, however, it is not the Reserve Bank’s policies on managing the cycle that have caused the sustained increases in house prices relative to income. They are the result of structural policy failures. The Reserve Bank can only buy time for other political and policy-making entities to deal with those issues.

Solution 4: Clarify immigration policy

While the bulk of housing demand over time comes from natural population growth and changes in family composition, volatility in housing demand often comes from net migration. (These issues were discussed in detail in Chapter 2.) When net 128migration suddenly increases, it can add to housing demand, which cannot be met at short notice as it takes time to release land, get consents and build houses.

But we also need to ensure we understand clearly those policies to pursue, and who to stop entering the country and how to stop them. The surge in net migration in 2014 and early 2015 is a very good case in point. The acceleration in net migration has been driven by, in descending order of importance, fewer people leaving New Zealand for Australia, more New Zealanders coming back from Australia, more people arriving on work visas (usually to fill skill vacancies), and more students.

If we are to use immigration policies to reduce net migration, presumably we will focus on those segments where numbers are rising the most. Since we cannot deny New Zealanders entry or force them to leave for Australia, this has to mean reducing the numbers of foreign workers and students coming into the country. But do we really want to place limitations on workers coming in to fill skill vacancies (including construction sector workers for the Canterbury rebuild) that cannot be met domestically? Do we want to reduce the number of overseas students, who are an increasingly important revenue source for our cash-strapped tertiary education sector? Clearly there are no simple answers here.

129We must also make sure that migrants do not unfairly cop the flak for house-price increases. A surge in net migration increases the demand for housing and therefore raises prices. But the growth in house prices tends to be temporary and cyclical. As the supply of new housing catches up with demand, these cyclical increases should dissipate. The accumulated and seemingly inexorable increases in New Zealand house prices suggest that it is not cyclical factors like net migration that are driving up prices over long periods of time.

In general, New Zealand has a long history of migration and societal change, and we are rightly accepting of and adaptable to changes in the country’s ethnic and cultural make-up. But we do lack a clearly articulated population strategy and, consequently, a clearly articulated immigration policy. Economist Paul Collier, in his book Exodus, argues that we need to talk openly about immigration.23 Not through the lenses of envy and racism, but in the context of a reasoned and deliberate discussion on why we want immigration, how many people we want and what kind of people we want. Having a clearly articulated population strategy, whatever that may be, would create a common base for all of us to work from. We also need good systems not just to bring people to New Zealand, but also to help them integrate into society and contribute to the economy.130

Solution 5: Identify the impact of foreign buyers

Any discussion of house prices, in Auckland at least, ends with someone pointing the finger at ‘cashed-up’ foreign buyers who are supposedly driving up house prices and leaving ordinary Kiwi buyers unable to compete. But experimental data on property title transactions suggest that much of the turnover in the housing market is driven by investors and movers, not first home buyers or new entrants to the New Zealand market. As we saw in Chapter 2, foreign purchases are not a large part of the total: the best estimates are that they comprised at most 9 per cent of all Auckland houses sold in 2015.24 This is similar to Australia, where 5–10 per cent of house sales by value are to foreigners.25 From the data available currently, it does not seem to be foreign buyers who are driving up house prices, but rather Kiwis driving up house prices by bidding against each other.

However, we have no comprehensive or reliable data on the influence of foreign buying in the New Zealand property market. Experimental data from CoreLogic are useful, but they lack the legitimacy of official, cross-checked and legally enforceable data. New Zealand needs to set up a system for gathering reliable data on foreign buying, to enable a fully transparent discussion on this issue.

As part of this system, we would like first to see 131additional information in the property title, so that any property buyer would have to record their IRD number, tax residency status and whether the house is being bought to live in or as an investment. Recording the IRD number and residency status would mean that we would know who is buying the houses – residents or non-residents. The requirement to register intent would also give the IRD the necessary data to levy tax on the rental income (if rented), identify misreporting of intent if a property was subsequently rented out but had not been declared as an investment, and gather tax on the sale of the house (if it was held for investment purposes). The IRD has already been cracking down on landlords and property flippers who have avoided paying tax, collecting a quarter of a billion dollars over the five years to 2015.26 But its job is made difficult because it operates with very little official information and has to rely on partial data to identify these tax evaders.

Second, we would require that transactions be settled using funds from a New Zealand bank account. This would mean any foreign funds entering the country would be subject to rigorous checks to guard against money laundering. There are concerns internationally (including in Australia) that residential property markets are being used to launder money.27 Given that banks must observe strict globally mandated rules against 132money laundering, the risk that money could be laundered through residential property would be significantly reduced if buyers were required to have a local bank account.

Third, all this information would be available publicly, so that the current concerns over foreign buyers can either be refuted with facts or understood and dealt with should they turn out to be well-founded. As this book was being finalised the government announced policies that aim to implement these policy suggestions by October 2015.28 The policies, which are still to be consulted on, propose that non-residents and New Zealanders buying and selling any property other than their main home be required to provide a New Zealand IRD number; and require non-residents buying or selling any property to have a New Zealand bank account and a New Zealand IRD number. Depending on how these proposals are implemented and their final form, they meet many of the policy suggestions we have outlined above.

Solution 6: Increase the supply of housing in high-demand areas

When it comes to high demand for housing, a number of places in New Zealand are suffering, but Auckland – as the largest and most rapidly growing city – is undoubtedly the worst off. Auckland is the powerhouse city of New Zealand because it has a 133‘thick’ market of job opportunities, and because scale matters: businesses benefit from having more accounting firms, advertising agencies and so on to help with their operations. But the city also has special geographic constraints, being squeezed into the space between two harbours. That makes it difficult to build efficient transport links through the city, and makes land close to the city centre doubly scarce.

This is not just a problem for Aucklanders, however. The way the city functions also affects the rest of the country, since other regions interact with its economy and are heavily dependent on its success for their own growth. Stifled growth in Auckland therefore has damaging knock-on effects on the rest of the economy. So getting its housing market fixed is a national issue. (And any lessons learned in doing so will be useful to other centres grappling with affordability issues.)

Clearly, a key step is to build more houses. There are various estimates around the scale of the housing shortage in Auckland; there is no clear science in these estimates and most rely on very sensitive assumptions. But as an illustration, the Salvation Army argues that there is a shortage of around 10,000 homes as of early 2015.29 At any rate, action to increase house building is underway. The Auckland Unitary Plan, though hampered by Nimbyism (as discussed further below), still allows 134for significantly greater land usage than at present. Meanwhile the Auckland Housing Accord, signed by the local council and central government, aims to supply 39,000 homes and sections over a three-year period to 2016.

But where should the majority of new housing go? The debate pits those who favour expansion of the city limits against those who argue for more housing to be built within the existing limits, a policy known either as intensification or densification. But the truth is that neither approach will work by itself: we need to do both.

The draft Auckland Unitary Plan, published in 2013, contained extensive options for both greenfield developments and densification through infilling and raising the permitted heights for buildings within existing city limits. However, these proposals were significantly scaled back during the community consultation phase, as discussed earlier. Land supply expansions were reduced due to Nimbyism, meaning that greenfield development is not as responsive to demand as it could be. Higher housing limits within the city were also rejected. The Unitary Plan process shows that good intentions can be difficult to implement in practice because the political economy favours incumbents. Constraints suit current home owners while restricting the choices of would-be purchasers grappling with unaffordability.135

Dealing with Nimbyism

While it is easy to point the finger at Nimbys, their behaviour is entirely rational. Property owners will quite naturally vigorously defend their property rights. Changes that will adversely affect them, for example by crowding their quiet street with lots of additional houses, are always going to be unpopular. In theory, of course, such developments are fine: when we talk about increased density and height in the abstract, most residents would agree that fitting more people into areas that are close to work and existing infrastructure is a reasonable goal. Where this breaks down is when that density is introduced in people’s own street or neighbourhood. Nimbyism can also lead to more extreme cases of Note (‘Not over there either’), in which people see increased risks of development in their neighbourhood if it occurs in neighbourhoods close by. The following excerpt from a 2014 opinion piece by the Auckland Council’s chief economist at the time, Geoff Cooper, makes this point neatly:

Auckland land use is heavily biased towards the ‘quarter acre section’ through rigid regulations. This creates a push for urban sprawl. The city’s rules prevent the supply of housing people want in the areas they want to live in – close to the city, with good transport and other amenities […]

[P]olitical economy plays a defining role in Auckland’s urban policy. Housing choice was cut back significantly following community consultation. Improving housing affordability and creating greater housing choice require radically new models of planning. Reduced regulations could be exchanged for greater local amenity, improved levels of service, financial compensation or some combination.30

What these ‘new models’ might be will require careful thought. There are no clear examples, but they could work in the same way as the process of compulsory acquisition, where government acts but compensates affected landowners. This is a difficult area of work, and one that needs serious effort. But it is a necessary component of a new toolkit for land use policy.

The case for higher density in Auckland

Cities seeking to build more houses must make a choice between higher density around transport links, building out beyond existing city limits, or a combination of the two approaches. In Auckland, there is a good case for focussing more on higher density. While there is value in expanding the urban boundary, it needs to be balanced against the negative impacts doing so would have on traffic congestion and the significant investments that would have to be made in transport and other 137infrastructure. Larger cities often struggle with congestion when they expand too much. This especially affects low socio-economic groups, who tend to live a long way from the city centre and need an affordable way to commute to work. The longer they are forced to travel, the more costly this will be for them. It is even harder when poorer households work outside of city centres (but not in the suburb where they live), as their commute will almost certainly have weaker transport links and they may have to catch several buses or trains to get to work. These very high transport costs can put an unmanageable burden on their household finances or indeed push them into debt – typically at high rates of interest.

The commute may also negatively affect their quality of life. As discussed above, the global standard is that no commute should be more than one hour. Yet the Auckland City Mission’s 2014 ‘100 Families’ report detailed how one woman ‘has to walk 10 kilometres to the nearest train station just to get to work, returning home the same way each day, leaving her only an hour to spend with her family every night’.

Some of these problems could be ameliorated by more affordable transport options. Outer-lying suburbs in cities such as London and New York have formed around transport links, enabling people to live far out because the underground 138or subway trains are efficient and affordable. In Philadelphia, good rail connections have helped convert weekend houses into permanent dwellings lived in during the week. Auckland does not yet have good transport links, and those it does have are already overwhelmed by a relatively small population (in comparison with other global cities). This pushes the case for a greater emphasis on densification, rather than expanding into more greenfields.

Densification has to be part of the answer. In Auckland, density doesn’t have to lead to massive high-rise towers as in, say, Hong Kong, just modest increases of one or two additional storeys across a large area. Higher-density building close to or in the city centre and transport nodes would allow more lower-income households and younger workers to reduce their commuting times and take advantage of amenities. Having a variety of options for people with different lifestyles frees up housing for others. There are also major benefits to the environment by reducing the carbon created by commuting. However, densification does not always sit well with politics. As discussed above, strong-willed communities with vested interests can bring high-density plans to a halt, even if they are better for Auckland longer term.

How can we get around this? Well, the government’s job is not to tell people how to live but to 139allow people to choose the life they want. This means, however, that people need to pay for the wider costs of their chosen lifestyle.31 Most people only think about personal costs and benefits. For example, when driving, they think about the cost of maintaining their car and about petrol costs, but they don’t think about the impact of their car ownership on others – that it contributes to congestion during rush hour, or creates emissions that add to the long-term costs of addressing climate change.32 Opponents of densification might change their mind if they were presented with the true costs that would be created by expansion – and told that they would have to pay their share of those costs through a big rates increase.

Conversely, we could look at ways of rewarding people living in areas where higher-density building will take place. Higher-density housing could be accompanied by increased amenities such as improved transport and more public parks, for instance. Or if neighbours are likely to lose light thanks to higher buildings going up around them, they should be compensated for it, with the cost of that payment generated by a levy paid by the builders.33 (Valuing these amenities, however, is extremely difficult; international examples do exist, but no system yet devised is perfect.)

We should also try to minimise the trade-offs that people have to make. The idea of housing 140trade-offs is illustrated by this quote from a Hong Kong resident interviewed for an international LSE Cities report:

Figure 4.2 Increase in housing supply versus demand, by size, per year (between 2006 and 2013 Censuses)

Note: While 67 per cent of the increase in demand is for one- and two-bedroom houses, only 12 per cent of the supply is in that sector; 73 per cent of the new supply is in large homes (four or more bedrooms).

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand, 2006 and 2013 Censuses.

You cannot have your cake and eat it … if you live in Tai Po [in the New Territories], there are more trees and plants, but it takes you longer to travel to Kowloon. You’ve got to make a choice: either a better environment or a more convenient place.34

To avoid people having to make this trade-off, we must ensure that higher-density housing comes with more attractions like attentive landscaping, parks and convenient transport links.

141Support for densification could be increased by explaining its benefits more clearly. Densification can come with a broader range of council amenities you can ‘sell’ to local communities, such as shared cultural spaces, vegetable gardens and retail centres. Some people may disagree with higher-density housing because they think it will affect their view or their neighbourhood, but in fact it could be argued that densification will allow their children to have a better quality of life through better access to home ownership and a more vibrant economy. More apartments will provide them with more options early in their careers.

Densification could thus also alleviate the stress experienced by many parents and grandparents today who are concerned about where their children and grandchildren will live. When twelve sections recently went up for sale in the outer Auckland suburb of Beachlands, on a first-come, first-served basis, there was a queue of people lining up to buy them – some of whom resorted to sleeping in cars overnight to ensure they got one of the sections. First in the queue was a grandfather hoping to secure a section for his grandson. He told the New Zealand Herald: ‘The housing situation is ridiculous right now … and this is what I’m prepared to do.’35142

Provide different types of housing

Housing affordability will improve when there are enough homes, and the types of homes available provide a range of options to suit different types of households at different stages of their lives and with different budgets – whether they are looking to rent or own. Right now, this is not happening. There aren’t enough higher-density options being built that cater to those looking for a one- to two-bedroom home. Most property developers focus on three- to four-bedroom, stand-alone houses. This tends to be most profitable for them because building higher density is more expensive (or not permitted), mainly due to government regulations. As a result, nearly three-quarters of the new supply in recent years has been in homes with four or more bedrooms, even though much of the growth in the population comes from singles and couples (as shown in Figure 4.2).

More housing variety is important for other reasons. Young people may enjoy living in apartments in the city to take advantage of greater amenities and lower transport costs. A larger household may prefer to be in the suburbs, as they are quieter and closer to schools and parks. Catering to these varying needs, by providing houses of varying prices and sizes, will be beneficial to us all. For example, building a home for a high-income household will ultimately free up 143their current home for a middle- or low-income family.36

Financing infrastructure

Land-use planning and other policy changes are extraordinarily important. But they are only one part of the puzzle. Another key part is having viably funded infrastructure such as good transport links, sewerage and water provision, and telecommunications (in particular broadband internet).

Local authorities rely on rates funding, spread across all ratepayers, for much of their spending. To fund the required infrastructure for newly developed land, they also charge development contributions and other levies to the developer. These add to the immediate cost of the new section, even though the benefits of new infrastructure will be enjoyed over many decades and by generations to come. These funding mechanisms do not align with the long-term benefits.

Other funding options used overseas could be worth copying. In Houston, Texas, Municipal Utility Districts (MUDs) are like mini-jurisdictions. They have taxing authority in their locality, and can issue debt, build and maintain infrastructure like roads and water mains, and provide services like rubbish collection.37 This means that developers can create a MUD and finance the infrastructure by 144issuing bonds, which are then paid out of local taxes over a set period of time – but only by the residents of the new jurisdiction. The city authority bears no risk for the development, but controls the quality of the infrastructure and has the right to annex the MUD and acquire all its assets and debts. While the results are not always beautiful (Houston is not the most attractive city), the affordable housing it creates can bring a significant competitive advantage. Houston has a strong economy and was Forbes’s Fastest Growing City in 2015.38 But despite booming growth in both the population and the economy, the median house price in Houston was just shy of US$180,000 in 2013 and the typical household earned around US$59,000.39 Houses prices are just three years of household incomes, compared to over eight years in Auckland. The main difference in Houston is that when population grew, so did house building.

The lesson, in short, is that having a responsive market that supplies a variety of housing choices is important for a growing city. Rigid rules, expensive land and uncoordinated infrastructure funding and provisioning mean that new supply does not effectively meet the needs of anyone.

Getting better at building on bare land

Concerns are often raised that developers are sitting on land and hoping to make a capital gain when it 145appreciates, rather than building on it. Developers, for their part, bemoan the many government processes and the long list of permits needed to go from inception to construction. In a recent report, the New Zealand Productivity Commission found that it typically took five years to take land that was outside of a zoned area through all the different steps to having a finished lot to build a house on.40

The Productivity Commission did not present evidence that land was being held onto for too long, but that regulatory processes were clogging up the system. They noted that ‘the slow pace at which land for housing is planned, zoned and released contributes to the high price of sections and thereby house prices’. Consequently they recommended that councils ‘review regulatory processes with the aim of providing simplified, speedier and less costly consenting processes and formalities’.

This view finds some support from recent reports on the building consents process, which is the remit of local councils. Looking specifically at the Auckland Council, the Auditor-General found that:

Building Control is technically meeting its statutory deadline of processing most applications within 20 working days, but this does not take into consideration the time that applications go ‘on hold’. When total elapsed time is taken into consideration, 80 per cent of applications are processed within 40 working days.

The fact that 70 per cent of applications lodged go on hold pending further information suggests that there is a large gap between what Building Control expects and what customers believe is expected of them.41

Local Government New Zealand, a body representing local councils, has highlighted the need to align three different pieces of legislation that impact on land supply: the Local Government Act, the Resource Management Act and the Land Transport Management Act. The regulatory complexity created by these acts means that it is conceptually and practically difficult to supply land quickly and easily. Until policy can be better aligned and streamlined, land supply will remain slow.

None of this, however, completely rules out the possibility that land banking is taking place in addition to the slowness of regulatory processes. Further work needs to be done to identify whether land banking, for profit motives, is slowing supply. If land banking is taking place, there are international examples of what could be done – for instance by taxing land (including vacant land) more heavily than structures. Dublin is contemplating introducing greater taxes on vacant land, which is currently untaxed, to increase the holding cost of bare land and encourage the land owner to develop it or put it to another use (as a public space for example).42 When taxes are much higher for land than structures, there is an incentive to make sure 147there are lots of income earning structures on that land to pay for the tax and maximise profits. The US city of Pittsburgh increased the tax burden on land to five times that on structures in 1979/80, encouraging building activity and avoiding having to increase other tax rates, which might have impeded growth elsewhere.43

Solution 7: Reduce the easy supply of money for housing

New Zealand’s financial standards have loosened so much in recent decades that households applying for mortgages can secure far more funding than they could previously. Banks have traditionally lent mortgages on the following terms:

- 20 per cent minimum deposit

- Twenty to thirty years to pay back the mortgage

- Floating or fixed interest rates for up to five years

- Mortgage payments at no more than one-third of income

Under the traditional model, a person with a $100,000 annual income could buy a house worth $470,000 with a $376,000 mortgage. But now, online bank calculators suggest that the same $100,000 could be used to buy a house worth $690,000 with a $621,000 mortgage.

148This massive loosening of financial standards, and the associated rise in household debt relative to income, have happened over a long period of time and have coincided with house prices rising disproportionately relative to incomes. This suggests that increased household indebtedness has at least partly contributed to the increasing price of homes.

Restricting credit availability or increasing the cost of borrowing could reduce pressure. But a more fundamental reworking of the banking sector is needed. As discussed above, international rules allow banks to hold relatively little capital against their housing loans, creating a strong bias towards residential mortgage lending. This increases the proportion of a bank’s lending tied up in mortgages and its levels of leverage. So there needs to be a fundamental rethink of banking regulation, starting with reconsidering the risk weights on housing so as to remove the bias towards mortgages, and against lending for business and entrepreneurial activity.

Solution 8: Clarify existing tax rules on property investment

New Zealand already has taxes that apply to investment property, but their application is unclear and inconsistent. A capital gains tax of a kind exists on paper in our current tax law, which 149states that if a property is bought with the intent to benefit from capital gains, then it is liable for tax when sold.

In reality, intent is not well defined and enforcement by the tax authorities is limited. We need clarification from the courts on what actually defines ‘intent’. One way to simplify this issue would be to create a ‘bright-line’ test for what qualifies as an investment property and therefore attracts taxes on its capital gains. This test would be set using clearly defined rules or standards, and could use figures such as the rental yield on the property and how many years it was held to determine whether it was bought with an investment intent.

An even better solution would be to ensure that intent was declared upfront at the time of purchase, along with the purchaser’s tax details (as we have suggested should be done for foreign purchases). This would give the tax authorities the necessary information to monitor purchases, cross-check declared intent against actual use, and subsequently tax transactions where necessary. With these changes in place, there would be no need for the introduction of a broader capital gains tax, such as has been proposed by some political parties.

The government’s recent proposals are a small step in the right direction. According to the initial information provided about these changes, any 150investment property sold within two years of purchase (except the family home, transferred by bequest or for family reasons) will be liable for taxation, effective October 2015.44 This stipulation complements the existing tax rules. The Reserve Bank has also defined an investor as the owner of a property that he or she does not live in, providing long-overdue clarification of this term. However the IRD still needs a better test for what constitutes ‘intent’ to apply to those who hold on to property for longer than two years.

Another tax issue needing urgent attention is the practice of negative gearing, which overwhelmingly benefits the rich.45 Negative gearing is a practice in which an investor borrows lots of money against their rental investment, which lifts their mortgage payments to a level at which their outgoings exceed their rental income. This creates a tax loss, which they offset against their other income, thus reducing their tax bill. This practice is most lucrative for those on high incomes, who get a bigger tax benefit because the income they have ‘removed’ from the system would have been taxed at the top marginal tax rate. While we do not have figures for New Zealand, we know that in Australia nearly half of the benefits of negative gearing go to the top 10 per cent of income earners.

There are of course legitimate reasons to count the costs of running a business, such as renting 151out property, for taxable income purposes. But we propose that instead of the current system, the returns from an investment property should be quarantined or ring-fenced, so that they can be offset only against the same investment. So if an investment property makes a loss one year, this is carried forward until the property does make a profit, or is offset against the capital gain (if the property was bought with an intent to benefit from capital gains) when the property is sold. This would ensure that residential investment properties stand on their own merits – as either genuinely profitable or unprofitable exercises – rather than hiding behind a tax shield.

If the discussion on property taxes in New Zealand were truly open, we would also broach the subject of imputed rent. Imputed rent, as discussed above, is essentially the rent a home owner would have paid if they had rented their house rather than bought it. In some countries, the implicit rent that the home owner pays to his or herself is taxed. The OECD recommends that its member countries tax imputed rent to equalise the tax incentive to own versus rent.46 But while imputed rent is taxed in Iceland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Switzerland, it has been deeply unpopular in other countries such as the UK, where it was abolished in 1963. It is also difficult to administer, as the tax authorities need to establish what the 152rent should be, a task requiring regular review and updating, although some countries have instead opted for an inflation index to adjust the rent figures each year. While we do not think an imputed rent tax is palatable or likely, a discussion on the issue, as a part of wider tax reforms, would help educate the public about the way the tax system is biased towards the relatively affluent home-owning class, while the poorer renting class miss out.

Solution 9: Provide an alternative to investing in property

When a person cannot invest in a home that they own, more needs to be done to provide other forms of investment. The majority of household wealth is in the home: around 55 per cent of household assets are held in housing. Another way to look at this is that for every $1 of financial savings, there is $1.20 in houses. For baby boomers in particular, housing has been a successful investment and an effective way for them to accumulate wealth. As discussed in Chapter 2, investors currently account for over 40 per cent of all house sales. (Of the rest, nearly a third are people moving, about 20 per cent are first-home buyers, and the remainder cannot be easily identified, but probably include people new to the market, including foreign buyers.) Investors are hoarding more and more properties and chasing more and more capital gains, even though the rental 153returns are meagre in hot markets like Auckland.47

This focus on housing presents real dangers: if an individual invests solely in housing, their assets are not diversified, and in the event of a housing market downturn they could be badly burnt. Yet investing in other avenues, such as the stock market, tends to be rare, and the country has a relatively small financial savings industry. This is in part because financial literacy and awareness of other forms of investment are not strong. It is also difficult to get into these other forms of investment. As discussed above, New Zealand has a ‘thin’ market of listed stocks relative to other countries, which means that an individual’s ability to build a portfolio of stocks diversified by types of company is limited. New Zealand does not have a big enough economy to support the many different types of companies that are available in global financial markets. Overseas stocks, meanwhile, are difficult to access unless you have a financial broker.

In addition, when it comes to tax, stocks are not on an even keel with owning a property – returns from stocks are taxed but owning a home (other than for investment purposes) is not taxable. This last point matters a lot, because the return in thirty years’ time from $100,000 invested either in equities or in a $500,000 house with a $400,000 mortgage would be about the same except for the incidence of tax and leverage. (Not 154only is most housing not taxed, but it also allows people to borrow more easily than non-house owners, as discussed above.) This means that there is an explicit financial incentive to buy houses. Not only does the bias towards housing create risks for individuals, it also slows financial growth by diverting funds that could be used to invest in businesses and thus grow the economy and provide more income and jobs.

One way to address the tendency to over-invest in housing is to improve financial literacy. Property has been the culturally approved way to invest in New Zealand, but it is not always a good buy. This argument could be made first of all to people thinking of purchasing a house, so that they are forced to work through the numbers to see if it is affordable. They should consider whether they can build enough of a deposit and have sufficient weekly earnings to afford a mortgage on the terms currently being offered. They should also take into account other costs such as maintenance, insurance and rates, and whether interest rates are likely to go up or down.

But at the moment, many people lack the ability or the confidence to do this. This needs to be addressed by teaching financial concepts at an early age in primary and intermediate schools. A better understanding of savings, investment options in housing and alternatives, and responsible use of 155debt would enhance people’s financial security and encourage a calculated approach to saving and investing, as opposed to the current emotion- and culture-driven approach.

But financial literacy on its own is not enough. The markets and products that people might invest in need to be well-regulated and investors protected from wrongdoing. Many New Zealand investors have had bad experiences in the stock market and with finance companies. The 1980s stock market crash led many to shy away from stocks, and finance company wrongdoings during the mid-2000s put the general public off investing in them. These events highlighted need for individual investors to ensure they have diversified portfolios (a portfolio of ten investments of different types is less risky than a portfolio of one investment in, say, a finance company), but also the need for secure markets that are well-regulated, monitored and enforced. Tighter regulation, and greater resourcing of enforcement agencies such as the Financial Markets Authority, may be needed to improve the attractiveness of these alternative investment options.

Solution 10: Improve construction sector productivity

Construction costs have risen relative to incomes over time, contributing – albeit in a relatively small way – to the higher cost of housing.

156The construction sector has many cost components, among them house builders, subcontractors, and building materials. In a recent investigation, the Commerce Commission did not find anti-competitive behaviour or price-gouging in the building-materials sector, although in a separate report the Productivity Commission found some materials were more expensive in New Zealand than Australia. House builders do not make greater profits – relative to their assets and sales – than other sectors of the economy, suggesting that they are not ripping off their customers with high prices.

However, there are some signs that prices are increased by a fragmented construction services sector – that is, a large number of sole-trader plumbers, electricians, and so on – which is also facing significant skill shortages. In addition, houses in New Zealand tend to be bespoke, rather than mass-produced (better known as pre-fabricated houses) as they are in many other countries. Small building operators also lack the scale to invest in efficiency measures that would reduce costs.48

Encouraging the adoption of better management systems in the industry and better informed consumers would help create a virtuous cycle of improvement. Bringing in large-scale projects with long-term certainty (say, 100 years’ worth of land supply with a clear articulation of timing and secure funding) would likely have an even bigger 157impact in encouraging local firms to upscale up and use the kind of technologies employed in larger markets, including much greater use of pre-fabrication. Pre-fabrication, which provides as much as 70 per cent of all new houses in countries such as Sweden, offers the chance to build houses more cheaply through standardisation and greater control over the building process. It also reduces waste and environmental impacts.49 In addition, it would entice large overseas players, who deliver developments at lower costs elsewhere, to set up shop in New Zealand.

The wrong answers: There are a lot of bad ideas out there

As can be seen from the solutions listed above, there are many things that will need to change for housing affordability and rental standards to improve. But the above solutions can and would work. In contrast, many of the solutions portrayed in the public arena as being a ‘quick fix’ are unlikely to deliver – at least until other elements change too.

Subsidies for first home buyers

Changing the rules around KiwiSaver schemes is a popular, but misguided, policy choice to deal with the lack of housing affordability for first home buyers. These rule changes allow people to take money out of their KiwiSaver schemes – within certain 158limits –and put it towards their house purchase. This can be extremely helpful for those who cannot afford a deposit. However, it is only a temporary fix, and will not improve the overall outlook for future generations – or lower house prices.

In fact, it may have strong negative effects. By increasing the amount of money chasing the same number of houses, it may, through the logic of supply and demand, end by pushing house prices up even further. Following the most recent initiative to make it easier to use KiwiSaver funds for home buying, more than 2,000 first home buyers snapped up housing subsidies of up to $20,000 in less than a month. But in the same period, the subsidies have been eclipsed by surging house prices.50 Similar effects have been seen overseas. The UK recently introduced a Help-to-Buy scheme, where the government lends money to home-buyers so that they only need a 5 per cent deposit. With no accompanying improvements in housing supply, however, this has simply stimulated demand and pushed prices up even further.51 Such schemes can also encourage people to take on more debt than is possible for them to pay off – and end up spending what should be their retirement fund.

Encouraging people to ‘save’ more