POSSIBLE CORRELATIONS BETWEEN the origin and dispersal histories of the major language families and the geographical expansions of major archaeological traditions today underpin an important field of interdisciplinary research, recently enlivened by the development of new techniques for tracing the genetic ancestry of human populations. The origins of this research field lie in early observations of relationships between widely separated languages, for example, those made by Johann Reinhold Forster when he sailed through the Pacific on Cook’s second voyage in 1772–1775. Forster compared forty-six lexical items across five separate Polynesian languages (Tahitian, Tongan, Maori, Easter Island, and Marquesan) and suggested, with remarkable percipience, that “all descended from the same original stem” (Thomas et al. 1996:185). He compared his Polynesian vocabularies with those of other languages in Melanesia, the Philippines, and the Americas, an exercise which led him to believe that Polynesian ancestry lay in the general direction of the Philippines. His statement that all the Polynesian dialects “preserve several words of a more antient language, which was more universal, and was gradually divided into many languages, now remarkably different” (Thomas et al. 1996:190) surely places him as one of the philosophical founders of the modern discipline of comparative linguistics. A contemporary of Forster, Sir William Jones, suggested in 1786 that Greek, Sanskrit, Latin, Gothic, Celtic, and Old Persian had so many noncoincidental affinities that “no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists” (Pachori 1993:175). Forster and Jones were essentially correct in principle, and Forster had the remarkable privilege of witnessing many of the peoples of the Pacific at the first point of European contact.

Comparative philological exercises similar to those undertaken by Forster and Jones continued throughout the nineteenth century, as for instance when Horatio Hale (1846) used both traditions and linguistics to reconstruct a history of migrations into the Pacific, especially those of the Polynesians. But it was only during the early twentieth century that American scholars such as Edward Sapir (1916) began to provide a systematic theoretical underpinning to such exercises, in this case by debating the relationships between comparative linguistics and ethnology for reconstructing the histories of Native American societies. Archaeology played little role in these early formulations, which were essentially comparative and based on trait distributions and theories of diffusion. Perhaps the first meaningful attempt to compare data from archaeology with that from comparative linguistics occurred with Gordon Childe’s The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins (1926), written at a time when British anthropology in general, unlike its contemporary in North America, had little interest in recovering the histories of preliterate societies. Hence the Sapir and Childe approaches never coalesced, and subsequent misuse of the Aryan concept persuaded Childe to abandon his search for the origins of peoples as defined by language.

Since the 1960s the search for consensus between the results of the three major disciplines (linguistics, archaeology, biological anthropology) has begun anew, particularly in regions with strong linguistic and genetic research traditions (Renfrew and Boyle 2000; Kirch and Green 2001; Bellwood 2001; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Bellwood 2004a). Modern developments in the computerized recording and comparison of large amounts of linguistic data, in understanding major economic and demographic transitions in human prehistory (e.g., the origins and spread of agriculture), and in understanding human population genetic ancestry via the analysis of nonrecombining portions of the genome (mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome), have allowed renewed progress toward a certain level of agreement on some issues. However, certainty in reconstructions of such magnitude, which after all involve the cultural and linguistic ancestries of many millions of people in the modern world, will always be elusive, and sometimes divisive. One reason for this is that human biological, linguistic, and archaeological variations have developed through time, and across space, by rather different mechanisms. Chromosomes, and the genes that lie along them, recombine in new and unique patterns with every new generation, but the elemental particles of languages and social systems do not. Thus sometimes we find people who are different in biological appearance speaking closely related languages. Intermarriage between populations of different origin can proceed in situations where a single language, rather than a mixture of two or more, continues to dominate the linguistic outcome (as in the modern United Kingdom or United States, for instance). But this does not mean that coevolution between genetic, linguistic, and archaeological systems is always absolutely impossible, and it must also be stated that social conditions in the modern United Kingdom and United States are not necessarily good role models for reconstructing prehistoric social landscapes. A major responsibility of the prehistorian is not to prejudge from a few modern comparative situations (at least not without analyzing them in their own right to estimate their relevance for the debate in question), but to establish when such correlations do or do not occur, and then to ask why.

The study of linguistic classification is twofold: (a) It attempts to identify which languages are demonstrably continuations of a common earlier form, and (b) it attempts to separate that evidence for common origin from the more recent developments within the individual languages as well as the results of language contact. In these tasks, the discipline of historical linguistics has achieved a number of remarkable successes.

—P. A. Michalove, S. Georg, and

A. Manaster Ramer (1998:452)

Each language has two possible kinds of similarities to other languages—genetic similarities, which are shared inheritances from a common protolanguage; and areal similarities, which are due to borrowing from geographical neighbors.

—R. M. W.Dixon (1997:15)

There are essentially two levels of language history which are of relevance for archaeological interpretation. First, and not discussed in detail here, we have the individual language, ethnolinguistic group, or historical community and its origins and ancestry in past time. In situations where plentiful written records exist, as with many Indo-European, Semitic, and Sinitic languages, fairly firm conclusions about recent periods of ethnolinguistic history can be drawn by linguists, epigraphers, and historians. Archaeology can often add to these conclusions, especially for historical periods. Yet because of the elusiveness of ethnicity in the archaeological record, it can be a very difficult task to trace the deep and prehistoric identity of ethnolinguistic or historical populations such as Celts (Megaw and Megaw 1999), Anglo-Saxons, Greeks, or Etruscans. More certainty can sometimes be gained if one is dealing with a relatively isolated and circumscribed region such as the Nile Valley in Egypt, but even there, many modern scholars are very cautious about pushing back any archaeolinguistic correlations into the periods before writing. The Pacific Ocean contains islands where one can assume there has been no substantial population replacement since first settlement by the ancestors of the current inhabitants, especially in Polynesia. But in all such situations, isolated or not, the populations and languages concerned are merely minor elements (generally single languages or subgroups) which form parts of much greater linguistic entities at the family or phylum level. It is at this second level of broader entities, involving whole language families and not just individual languages or subgroups, with foundation expansions set deeply in the small-scale sociocultural mosaics of prehistory, that archaeology most often and usefully interacts with linguistics. This chapter is concerned with this broader level.

So, bearing in mind the insight of Forster more than two hundred years ago, we need to commence with a consideration of the concept of the language family, as a genetically constituted and evolving entity which has had

1. a history of genesis within a homeland area,

2. a progressive dispersal to its current boundaries, and

3. subsequent diversification into separate languages (sometimes numbering in the hundreds or thousands) via internal processes of linguistic change and external processes of interaction.

Today, the methodology of comparative linguistic reconstruction is precise. Like the methodology of cladistics as applied in biological classification (see Collard et al., chapter 13), its main goal is to identify shared innovations which can identify language subgroups. As an example of what linguists mean by shared innovations, Robert Blust (1977; Tryon 1995) defines the Malayo-Polynesian languages apart from the Formosan ones within the Austronesian family because the former have undergone a series of developments not found in Formosan. These include the innovation of a new pronoun form (*-mu shifts from second person plural to second person singular), two new verbal prefixes, *pa(-) and *ma(-), and a merger of *t and *ts to *t. These innovations occurred at around the time of initial Malayo-Polynesian dispersal, presumably in the northern Philippines, and are today found very widely in the descendant Malayo-Polynesian subgroups in Island Southeast Asia and Oceania. Reconstructions different from that of Blust for the Austronesian family tree can be derived from lexicostatistical analyses (Dyen 1965), but Blust has successfully countered these in favor of his preferred shared innovation methodology (Blust 1995, 2000).

The subgroups so recognized comprise languages which have shared a common ancestry apart from other languages with which they are more distantly related. Languages which comprise a subgroup share descent from a common “protolanguage,” this having been in many cases a chain of related dialects or even a set of related languages. (What linguists define as a protolanguage could have been a phenomenon distributed across a wide area rather than a single language [Dyen 1975; Dixon 1997:98].) The proto-languages of subgroups within a family can sometimes be organized into a family tree of successive linguistic differentiations (not always via sharp bifurcations, unlike real tree branches), and for some families it is possible to postulate a relative chronological order of subgroup formation. As an example of this, many linguists believe that the separation between the Anatolian languages (including Hittite) and the rest of Indo-European represents the first identifiable differentiation in the history of the Indo-European family. Likewise, the separation between the Formosan languages of Taiwan and the Malayo-Polynesian languages of the rest of the Austronesian family represents the first identifiable differentiation within Austronesian. In these two cases, these smaller regions within the whole—Anatolia and Taiwan—are likely to have contained the protolanguages which lie at the bases of these two large families (Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Austronesian respectively), and in this regard they can be legitimately regarded as the immediate homelands from which commenced the dispersal of languages ancestral to the extant or historically recorded distribution (Dolgopolsky 1993; Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1995; Renfrew 1999; Blust 1995).

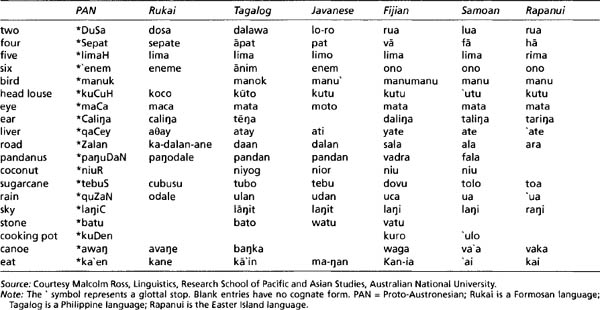

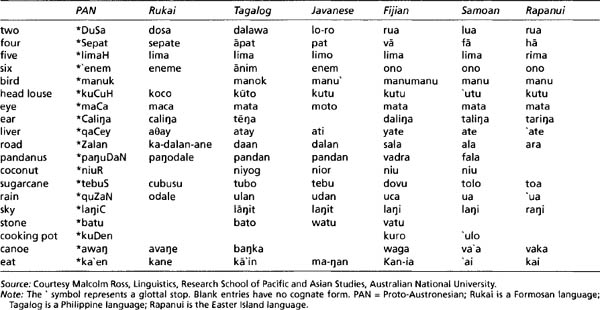

Table 14.1. Some Widespread Austronesian Cognates

The vocabularies of reconstructed protolanguages (e.g., Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Austronesian, Proto-Malayo-Polynesian) can sometimes provide remarkable details on the locations and lifestyles of ancient ancestral communities, with many hundreds of ancestral terms and their associated meanings reconstructible in some instances: see, for example, Kirch and Green (2001) for the remarkably rich case of Proto-Polynesian, and Ross et al. (1998) for Proto-Oceanic.

There is also a linguistic technique known as glottochronology, which attempts to date protolanguages by comparing recorded languages in terms of their percentages of shared cognate (commonly inherited) vocabulary, applying a rate of change calculated from the known histories of Latin and the Romance languages (Gudschinsky 1964). But the rate of change varies with sociolinguistic situation, often a complete unknown in prehistoric situations. Glottochronology can only be used for recent millennia and for those languages which have not undergone intense borrowing from languages in other unrelated families. It is not a guaranteed route to chronological accuracy (for debate on this issue, see Renfrew et al. 2000).

The other major source of linguistic variation, apart from modification through descent, is that termed by linguists “borrowing” or “contact-induced change.”1 This operates between different languages, and often between languages in completely unrelated families. Borrowing, if identified at the protolanguage level, can be as much an indicator of the geographical homeland of a language family or subgroup as can genetic relationship. For instance, the early stages of Indo-European and Semitic are believed by some Russian linguists to have been in contact, with consequent linguistic borrowing, a circumstance which obviously reinforces an Indo-European homeland in Anatolia—close to the region occupied by Semitic languages—as opposed to the Pontic steppes of the Ukraine and southern Russia (Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1995). Borrowing can thus reflect important contact events in language history.

Language families are remarkable phenomena. The largest ones tie together hundreds, sometimes thousands, of languages and communities spread right across continents and oceans.2 They extend far beyond individual community awareness—how many speakers of English (excluding linguists!) would be aware that their language shares a common origin with Bengali and Kurdish, or have the faintest idea why? They also extend far beyond the reaches of history—related languages ancestral to both English and Bengali were spoken in northwestern Europe and northern India long before any western European or Indian history was written. If we dissect a major language family, we often find a sharing of related forms in lexicon, grammar, and phonology so widespread that only a concept of common origin, of descent from a homeland ancestral linguistic entity, can explain it. For instance, the widespread Austronesian lexical cognates (forms acquired by descent from a common ancestor) listed in table 14.1 are so numerous that we cannot attribute them solely to borrowing between languages which once had entirely different forms. They exist because all the languages listed have inherited these forms as a result of their common ancestry.

Common ancestry—or phylogenetic relationship to use the terminology of science—is a powerful concept. Language families, like animal species, cannot form through the convergence of languages originally unrelated into a single genetic taxon within which all units share a common ancestry. Speakers of unrelated languages have sometimes been forced to live together in colonial situations of long-distance population translocation, and so obliged to create hybrid pidgin languages. Some pidgin languages have taken on major roles today, for example, Tok Pisin, the major lingua franca of Papua New Guinea (Kulick 1992). But examples of such developments in linguistics are rare, unlikely to have been of major significance in the prestate periods of human prehistory, and thus hardly convincing as explanations for the genesis of whole families of related languages spread over enormous distributions of territory (Bakker 2001). Languages can also borrow from each other, hence the existence of both areal and genetic research fields within historical linguistics, but again such languages do not “fuse,” as any study of such processes in regions as diverse as the Indian subcontinent, Melanesia, Amazonia, and Mesoamerica will indicate. Put simply, most languages can be placed easily in separate language families, rather than left in some undefined space between them as genetically opaque hybrids. Once languages begin to separate they usually continue to do so, and convergence is not convincing as a major player in language family origins.3

Since convergence cannot explain a language family, what can? The answer is expansion from a homeland region, such that a “foundation layer of language” (probably in the form of phylogenetically related dialects), which has spread in some way from a source region, gives rise to differentiating daughter languages. In reality, the number of sociohistorical situations in which daughter-language differentiation can occur is immense. Communities can stay in contact or split irrevocably; they can form differential relationships with other unrelated peoples; some groups can even abandon their original languages and adopt others (language shift), as if to make the task of historical reconstruction even more difficult. But the fundamental observation that the ancestral languages in a family have somehow spread outward from a source region is one of the most significant which can be made in any quest for human cultural origins.

The next question is perhaps obvious. How do languages spread over such large distances? What cultural driving forces lay behind the spreads, forces of sufficient strength that these families often came to dominate completely the language maps of vast regions of the world? Did they spread because people who already spoke them moved into new territory? If this is so, we must explain the reason for their colonizing success, and also what drove them out of their homeland or attracted them to their new utopia. On the other hand, have languages spread because other people have adopted them, by language shift? In this case we must ask why people would wish to abandon their original native language, and often many attached cultural norms, in favor of an outsider target language. Factors such as multilingualism, intermarriage, trade, war, conquest empires, and nowadays literacy can often contribute to situations of language shift, but they are not of unvarying validity and, on the scale under consideration here, they have been generally no more than local factors.

At the level of the major language families, it is necessary to reiterate several important points. Some families are extremely widespread, containing hundreds, even thousands of languages (Austronesian and Niger-Congo both have more than 1,000 languages). They are ancient, with origins and foundation dispersals normally located in time bands long before any of the major historical empires. We cannot explain them by processes such as imperial conquest or the spread of literacy. We probably have to think of them spreading through small communities of hunters or early farmers with no overarching political unity. Hence they did not spread because of the conscious intention of any particular polity; indeed their vast extent would rule out completely any such concept at the time levels concerned. Not even Alexander the Great was able to spread Greek to anywhere like the full limits of the Indo-European language family to which Greek belongs. The Romans likewise succeeded no better with Latin, and Genghis Khan succeeded hardly at all with Mongolian. The Arabs succeeded not at all in Southeast Asia, where the world’s largest Muslim country—Indonesia—is today located. True, English and Spanish have been more successful in their spreads since A.D. 1500, but this was because of massive levels of seaborne colonization of new territories with thin indigenous populations (Crosby 1986). In regions such as India and Malaysia, with dense populations in strong political groupings which resisted European colonization, English was not able to force all other languages out of existence, and certainly has not done so today. Spanish did not simply erase all the Indian languages of what is now Latin America—many millions of Central and South American Indians still speak their native languages, just as do Australian Aborigines living away from regions of European domination. The current spread of English as a lingua franca is not a process which is likely to have any parallel in prestate prehistory, simply because it demands literacy, a vast web of modern communication, and not least the cultural heritage of a former world empire of an extent inconceivable for any prehistoric (or at least pre–Iron Age) archaeological situation.

Careful consideration of such situations can leave no doubt that all the recent and historically recorded languages which have undergone great extension of range—for example, Arabic (in the Middle East and North Africa only), English, Spanish, Thai, Chinese—have done so because of initial settlement away from the homeland regions by native speakers (as supported, for instance, by Driver 1972:6; Diebold 1987:27; Coleman 1988:452; although others have favored the idea of language spread without population movement, for instance, Thurston 1987; Nichols 1997). Of course, indigenous local populations have also adopted these languages to varying degrees; hence modern speakers of English obviously do not all have a precise genetic ancestry in Anglo-Saxon England and modern speakers of Arabic are not all directly descended from seventh-century Arabians. But all this “reticulation” (or interaction; see Bellwood 1996) is a little beside the point, which in this instance concerns the reasons for the foundation spreads of languages as whole-population vernaculars. Native speakers of the ancestral languages concerned, and the material cultures and subsistence economies which underpinned their societies, were the drivers of the process.

It may be protested that the ancestral languages within the major language families could have taken several millennia to reach their ultimate prehistoric boundaries. We know, indeed, that they did in the cases of Austronesian and Indo-European, both of which (as described later) continued to spread for periods of several thousand years prior to any historical documentation. But this does not alter the fact that in many cases including these two, the outer boundaries were reached deep in prehistoric time. Similar demographic and economic processes drove these expansions, even if periods of standstill allowed the generation of new forms of diversity, such that populations which ultimately reached the geographical boundaries might have been quite different, in biological appearance at least, from the original homeland populations. Such has obviously been the case if we examine anthro-poscopic variation across ethnolinguistic populations such as the pre-Columbian Indo-Europeans (e.g., French and Bengalis) and the Austronesians (e.g., Filipinos and Solomon Islanders).

So what is the relevance of all these linguistic observations for archaeology? Languages have speakers, and it is those speakers who create the material culture which forms the archaeological record. If we are going to consider the records of comparative linguistics and archaeology with the intention of recovering data on human prehistory, we need to consider if the evolution of patterns within the worldwide distributions of language families and archaeological assemblages could have been correlated. The comparative process becomes even more complicated if we introduce the third major source of data—human genetic ancestry. Did race, language, and culture ever coevolve within the course of human prehistory? If they did, then the task of understanding human prehistory could, in both theoretical and practical terms, become more manageable.

This issue of coevolution was one of the great questions of anthropology throughout the twentieth century. Today, most archaeologists would perhaps agree with Sapir (1916:10) when he stated, “It is customary to insist on the mutual independence of racial, cultural and linguistic factors.” The misuse of racial and cultural information in the recent past has certainly made this an acceptable and noncontroversial stance. But in my view, any correlations would have been situational (contingent on specific histories) and not always negative. In some historical situations they would have been strong, in others perhaps absent altogether. To understand this, we need to think of prehistoric time in terms of a series of successive and often quite different situations, rather than as an undifferentiated palimpsest or simply a reflection of observed situations in the ethnographic present. In particular, we can perhaps expect reasonable levels of social and linguistic coherence during situations of population movement, especially through landscapes with no prior inhabitants.4 This is important since, as discussed above, episodes of such migration in some form are required to explain the origins and spreads of most of the major language families.

So at those points in time when active language spread was under way, especially in situations of prestate “tribal” social and political organization, we have good reason to accept that there would have been fairly strong correlations between spreading human biological populations and their languages and cultures. For any given language family there were probably several such periods of active spread in its history; we do not need to assume that a single population and biotype dominated the whole process. It is more likely that periods of spread were separated by periods of relative stasis, when population mixing gave rise to new cultural and biological formulations which, in turn, expanded further each time the spread processes began anew. Explanations of this type, in which populations spread, pause, and reformulate, then spread again, are essential if we are to explain the existences of huge language families such as Indo-European and Austronesian, within which there is no absolute biological or sociopolitical homogeneity. These issues are discussed from examples further below, after presenting the nature of the linguistic record and its legitimate (noncircular) intersections with archaeology.

Correlation of the archaeological and linguistic records is not always a simple matter because the two classes of data are conceptually quite discrete. However, correlations can be made when language family distributions correspond with the distributions of delineated archaeological complexes, particularly when the material culture and environmental vocabulary reconstructed at the protolanguage level for a given family correspond with material culture and its environmental correlates as derived from the archaeological record. Many reconstructed protolanguages, for instance, have vocabularies which cover crucial categories such as agriculture, domestic animals, pottery, and metallurgy, these all being identifiable in the archaeological record. The correlations become more positive if these new material and economic complexes enter the archaeological record relatively abruptly, as they do over those vast temperate and tropical regions of the world where ancient hunter-gatherer economies were replaced by Neolithic/Formative farming.

Figure 14.1. The major language families of the Old World. After Ruhlen 1987.

Because languages change constantly through time, and because relationships between languages become ever fainter as we go back in time, most linguists assume that language family histories apply only to the past 8,000 to 10,000 years. At a greater timescale we enter the arena of macrofamilies, such as Nostratic and Amerind, concepts which claim genetic relatedness between otherwise discrete language families and which cause rather vituperous debate among linguists because of their very ambiguity and elusiveness, and also because of the differing procedures involved in their recognition (Renfrew and Nettle 1999). Most well-defined language families correspond to relatively recent phases in the archaeological record, especially since the beginnings of agriculture in temperate and tropical regions. Some language isolates, such as Basque in Iberia, are sometimes suggested to have evolved in situ since preagricultural and even Pleistocene times, but in most cases such conclusions depend on distributional factors rather than direct evidence of time depth. No coherent reconstructible relationships within Pleistocene language families, which must once have existed, can be expected to have survived the passage of so much time.

Figure 14.2. The agricultural homelands of the world, with approximate dates of origin and directions of spread of the agricultural systems concerned.

Today major studies revolve around the origins and dispersal histories of large-scale language families such as Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Austronesian, Niger-Congo, Pama-Nyungan, and Uto-Aztecan (figure 14.1). Most of these language families are associated now with agriculturalist populations and probably have been for most of their histories, but the Pama-Nyungan languages of Australia were spoken entirely by hunters and gatherers. Some major families had both farmers and hunter-gatherers among their speakers. In such cases, especially where the hunter-gatherers form minorities in terms of numbers of societies (as in Austronesian, Niger-Congo, and Uto-Aztecan), it becomes necessary to consider whether the economic ancestry of the nonfarmers has always been nonagricultural, or whether they have altered their subsistence in adverse environments from an agricultural foundation economy into a foraging one. Likewise, for language families such as Algonquian and Uralic in which hunter-gatherers occupied much vaster regions than farmers, we need to ask the converse question—did farming spread among some ethnolinguistic populations originally consisting entirely of foragers?

The reasons why the foundation spreads of language families occurred will obviously be numerous and not always amenable to recovery. Spread of native speakers of the foundation dialects is, as noted above, an essential element. One can think of many possible reasons why a particular population should wish to expand into a new territory. Archaeologists, with their comparative knowledge of human history and anthropology, are well placed to suggest such reasons. Languages do not drive their own expansions across large territories; human populations do, and populations of course react to those perturbations of environment, economy, and sociopolitical maneuvering which determine so much of the archaeological record. For instance, many archaeologists and linguists today recognize that many of the larger language families of temperate and tropical latitudes could owe their initial creation to population dispersal as a result of demographic growth following on from the development of agriculture (Renfrew 1996; Bellwood 1994, 2001, 2004a, 2005; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Diamond and Bellwood 2003). If this is so, then the homelands of these particular families can be expected to overlap with the regions of early agriculture, as indeed seems to be the case for the Middle East, Central Africa, China, and Mesoamerica. Figures 14.2 and 14.3 illustrate these correlations. Similar explanations based on demography, albeit without the factor of agriculture, are also required to explain those language families associated totally with hunting and gathering populations, such as Athabaskan and Eskimo-Aleut, both with well-recorded prehistories of spread (Fortescue 1998).

Figure 14.3. Language families of the Old World and their suggested patterns of expansion (base map after Ruhlen 1987; arrows as also published in Diamond and Bellwood 2003:fig. 2). Key: 1: Bantu; 3a to 3c: Austroasiatic, Tai, and Sino-Tibetan respectively; 6: Trans New Guinea; 7: Japanese; 8: Austronesian; 9: Dravidian; 10: Afroasiatic; 11: Indo-European; A: Turkic; B: Nilo-Saharan.

For the remainder of this chapter I examine the prehistories of two of the best-studied language families in the world—Indo-European and Austronesian.5 Both reflect quite strong evidence for correlation between archaeology and linguistics.

The Indo-European (IE) language family is one of the largest in the world, already stretching across Europe into central Asia in pre-Columbian times. There has been little total agreement on any final tree structure for its twelve or so component subgroups (Ruhlen 1987; Dyen et al. 1992; Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1995). Several linguists have noted that the IE family tree is notably “rake-like,” with many independent branches having separated at an early stage from a common ancestral form (Nichols 1998:221), a situation which could reflect a widespread and fairly rapid dispersal of foundation languages into Europe and Asia. However, Warnow (1997), supported by Renfrew (1999), has recently provided subgrouping information in support of a more complex and tree-like picture, with an early spread of Proto-Indo-European from an Anatolian homeland into the Balkans and central Europe, and eastward into central Asia. Anatolian, Italic, Celtic, and Tocharian were perhaps derived from this initial spread. Subsequent episodes of language interaction and movement, especially with the Germanic, Romance, Slavic, and Indo-Iranian subgroups, have overlain and masked much of the earlier spread history. A similar subgrouping hypothesis, with Anatolian, Tocharian, and Greek forming the earliest differentiations within the IE family, in these cases with calculated time depths of separation between 6000 and 7500 B.C., has recently been published by Gray and Atkinson (2003).

To explain early Indo-European dispersal, many archaeologists have favored a process of “elite dominance” whereby incoming pastoralists imposed language shift on compliant native (non-IE) Neolithic farming populations across much of Europe. Such explanations are often associated with a homeland in the steppes north of the Black Sea, followed by a spread into Europe by Late Neolithic and Bronze Age pastoral peoples with domesticated horses and wheeled transport (Mallory 1989; Anthony 1995). According to the archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, these people, with their Indo-European warlike religious traditions and patrilineal bias in social life, undertook their migrations into Europe from the Pontic steppes between 4500 and 2500 B.C., dominating and absorbing the older, more matrilineal, and goddess-worshiping non-IE Neolithic societies in the process—a now celebrated interpretation which has been influential in some feminist literature (Gimbutas 1985, 1991).

This view of Bronze Age conquest and language replacement for Indo-European in Europe dispersal faces two problems. Recent realization of the significance of the extinct Anatolian languages (including Hittite) has led to a greater emphasis on the possibility of an Anatolian homeland for IE, located south of the Black Sea (Dolgopolsky 1993; Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1995). In addition, the Bronze Age conquest hypothesis leaves unanswered the question of how incoming elites could ever have caused language changes over such vast regions among such a mosaic of independent and warring Bronze Age chiefdoms.6 Even though Europe continued to harbor many peripheral non-IE languages into Classical times (Zvelebil 1988; Sverdrup and Guardans 1999), the extent of IE spread in European prehistory was immense, extending across central Europe to Britain and Ireland (not to mention the spreads into central Asia and the Indian subcontinent!). The Gimbutas hypothesis has thus been challenged by the archaeologist Colin Renfrew (1987), who opts instead for an association of early IE with early Neolithic farming dispersal into Europe from Turkey, a view developed independently by Krantz (1986) and now also accepted in part by Mallory (1997), a former proponent of a Pontic steppes homeland.

This explanation locates IE dispersal along a major archaeological unconformity which extends over most of temperate Europe between about 6500 and 3500 B.C., and which also extends eastward into northern India between 3000 and 2000 B.C. It also provides a demographic mechanism whereby farmers assimilated much thinner populations of hunter-gatherers. But the process was not all one way, with total domination by in-migrating farmers. As originally modeled from genetic and archaeological data by Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza (1973, 1984), such dispersal (termed by them “demic diffusion”) would have involved continual mixing between the farmers and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, who would in the early days always have occupied far more of the landscape than the valley-oriented farmers. Hence there should exist a slightly blurred genetic signal for initial Neolithic dispersal from Anatolia into Europe, since by the time Neolithic farmers reached the British Isles we might well expect them to have acquired a substantial component of local Mesolithic genetic heritage, as the mtDNA and Y chromosome data in fact suggest (Sykes 1999; Richards et al. 2000; Renfrew and Boyle 2000). The farming spread across Europe from southeast to northwest also took almost 3,000 years, ample time for considerable interaction with and incorporation of Mesolithic populations, who undoubtedly did not disappear overnight. Because of this, archaeologists today do not see the Neolithicization of Europe as resulting in a total replacement of population, but instead favor scenarios which allow for considerable adoption of agriculture by Mesolithic populations in some regions, especially Iberia and the Baltic–Scandinavian regions (Zvelebil 1998; Renfrew 2000; Richards 2003).

If we stand back and look at the current debate over IE origins and early dispersals, we can learn several lessons. Extreme positions favoring either total farmer domination or universal adoption of agriculture by Mesolithic populations obviously do not work. Neither do explanations based on elite dominance. The linguistic evidence is also somewhat malleable. It is difficult to differentiate absolutely between the evidence for a Pontic steppe as opposed to an Anatolian homeland, and it is also difficult to pinpoint the exact nature of Proto-Indo-European society—was it strongly patrilineal and pastoralist with horses, carts (Anthony 1995), bronze weapons, and a warlike disposition? Or was it basically a Neolithic agro-pastoralist society (Dolgopolsky 1993; Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1995) located about 2,000 years earlier in time? The linguistic evidence is not absolutely clear on any of these issues—dates are not firm and neither are the precise significances of many cultural cognates or early borrowings, although that PIE society was agropastoralist as opposed to purely hunting-gathering is not in doubt. Also, the archaeological record is not clear in its interpretations with respect to Neolithic population spread versus Mesolithic adoption of agriculture. The early European Neolithic cultures are sometimes widespread and homogeneous, as in the Balkans and much of central Europe, where they support a farmer-spread hypothesis. Conversely, they are also sometimes very regionalized, as in many parts of western and northern Europe, where they support a piecemeal Mesolithic adoption-of-agriculture hypothesis. Material culture cannot arbitrate these issues with finality.

Perhaps the best conclusion here is a comparative one. The interdisciplinary hypothesis which links Neolithic spread with that of IE languages out of Anatolia makes much more sense of the data from the viewpoints of both archaeology and linguistics, at least in my opinion, than does that of a Bronze Age spread from the Ukraine or central Asia. This is because, for the Anatolia-Neolithic hypothesis, both disciplines can provide mechanisms relating to farmer demographic increase and vernacular language expansion, via a significant component of native speakers movement into new territories, which can be regarded as credible in terms of comparative data from historical sources. The Ukraine Bronze Age hypothesis lacks a significant pan-European horizon of rapid change in the archaeological record and it also requires language change across a vast area via historically unparalleled processes of elite dominance. A third hypothesis, that the IE languages dispersed initially in the Paleolithic as a result of migration into deglaciated lands (Adams and Otte 1999) works not at all because, as noted, Proto-IE has a substantial agro-pastoralist vocabulary reflecting an economy which is unlikely to have existed during the Late Pleistocene. Neither does this account explain how IE spread into those vast territories which were never glaciated. Beyond this we perhaps cannot go; archaeolinguistic reconstruction is not an activity amenable to absolute proof.

Moving on beyond IE to the language families which are its close neighbors, the farming/language dispersal hypothesis (Renfrew 1991, 1996; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Bellwood 2004a) would see the protolanguages for Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Sumerian, Elamite, and possibly Turkic as located in the wheat, barley, cattle, and caprine zone in the Middle East, with initial outward dispersals into Europe and central Asia occurring after the establishment of mixed cereal growing and stock raising in the period between 7500 and 6500 B.C. (late Pre-Pottery Neolithic). During this time, the archaeological record tells us unambiguously that Neolithic population densities were increasing in an overall sense quite rapidly, despite periodic environmental setbacks and short-term population retractions.

This broader perspective brings up the question of yet earlier language macrofamilies, long-range and fairly limited reconstructions which make some linguists rather hot under the collar as linguistic methodology is pushed to, and sometimes beyond, the accepted limits (Dixon 1997:36–44; Campbell 1999). Perhaps archaeologists need to consider if it is pure coincidence that the language families stated to belong to the “Nostratic” macrofamily—IE, Afroasiatic, Kartvelian, Uralic, Altaic, (Elamo-)Dravidian—should also come closest to a shared center of gravity in the Middle East, a region of early agro-pastoralism. Could they therefore share some faint traces of an archaic inherited residue from a period of common regional ancestry? Likewise, we can also ask if the language families of eastern Asia (Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Tai, and Hmong-Mien) could all have begun their dispersals from the region of rice and millet cultivation in China, focused in the middle and lower Yellow and Yangzi valleys, between 5000 and 2000 B.C.—with Austronesians eventually colonizing the greater part of the Pacific (Bellwood 1994, 2000; Blust 1995; Peiros 1998; Reid 1996). Furthermore, but without reference to agriculture, we can ask if the “Amerind” macrofamily of Greenberg (1987), a bête noire of many Americanist linguists, might reflect the existence of a foundation spread of Paleoindians with limited linguistic diversity from Siberia through the Americas starting about 13,500 years ago? These are regions of extreme touchiness for linguists and archaeologists alike. We must tread carefully and avoid circular reasoning, but the implications of these issues, however vague and insoluble they might appear in reality, are nevertheless immense.

The Austronesian family comprises about 1,000 languages spread more than halfway round the world from Madagascar to Easter Island (Blust 1984–1985, 1995; Bellwood 1991; Pawley and Ross 1993). There are today approximately 300 million Austronesian speakers, mostly in Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia. Individual languages may have from a few hundred indigenous speakers (like many in western Oceania), to upward of 60 million (Javanese). The Austronesians themselves are mostly of a southern Mongoloid (East Asian) phenotype, but many Melanesian populations also speak Austronesian languages, as do Agta (Negritos) in the Philippines. Traditional cultures varied enormously, from Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic states to forest hunting and gathering bands (Glover and Bellwood 2004). Yet by the logic described above, the Austronesian entity is not merely a result of haphazard and nonhistorical patterning in time and space; there is a solid core of shared phylogenetic history, despite vast geographic spread and the occasional impingement and even assimilation of other, unrelated ethnic communities.

At a deep chronological level, Austronesian is claimed by some linguists to be related to other East Asian language families such as Austroasiatic, a large family which includes Khmer and Vietnamese (Reid 1984–1985; Blust 1996), Tai-Kadai (Benedict 1975), and Chinese (Sagart 1994). Blust (1996) supports the concept of an Austric superfamily, which includes the Tai, Austroasiatic, and Austronesian languages, and which originated in upper Burma about 7000 B.C. At this time depth there can be little certainty about linguistic relationships, but the faint observations of shared ancestry between these families, of a degree likely to suggest either genetic relatedness or early borrowing (or both), are extremely significant. As it happens, my own view (Bellwood 1994, 1997, 2004b), as well as that of Higham (1996), favors a region of shared origin for these families focused more on the middle and lower Yangzi basin of China, for which we have an archaeological record of early rice agriculture equivalent in its intensity to that for wheat and barley agriculture in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Levant. Furthermore, the East and Southeast Asian Neolithic cultures, with their related cord-marked, incised, and painted or slipped pottery forms, domesticated pigs, dogs, and poultry, polished stone adzes, spindle whorls, bark cloth beaters, stone and shell ornaments, and—last but not least—their cultivation of rice, all form circles of decreasing age away from a central Chinese heartland, as do the Neolithic cultures of western Eurasia around the heartland of the Levant. In both instances we can find an initial demographic driving force for expansion, backed by the essential supports of chronology and directionality.

Austronesian languages per se have never existed on the Chinese mainland, since the family itself only crystallized into independent visibility following the breakup of its protolanguage. That process almost certainly occurred in Taiwan, the island which contains the greatest number of primary branches within the family—nine out of the ten—according to Blust (1995, 1999). The tenth subgroup is Malayo-Polynesian, the subgroup which includes all the extra-Formosan languages. Linguistic reconstructions of the material culture of Proto-Austronesian, an entity which probably correlated with the establishment of rice-growing Neolithic populations on Taiwan soon after 4000 B.C., indicate the presence of domestic dogs, pigs, and chickens, use of the loom and the canoe, and a range of crops and useful plants including pandanus, bamboo, rattan, rice (with a large vocabulary for different aspects of rice culture), sugarcane, foxtail millet, taro, and Alocasia (a large aroid) (Blust 1995; Zorc 1994; Pawley and Ross 1993, 1995).7 Tropical crops were rare or absent in Proto-Austronesian times, since Taiwan lies mainly beyond the Tropic of Cancer, but warmth-loving plants such as yams, breadfruit, bananas, coconut, and sago had made an appearance in the crop repertoire by the time of the breakup of Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, probably somewhere in the northern Philippines. These crops are all native to Island Southeast Asia and western Melanesia. In general, Austronesians seem not to have borrowed much economic vocabulary from preexisting peoples, the only clear example being a word for taro perhaps borrowed in western Melanesia from Papuan language sources (Ross 1996). Once they sailed beyond the Solomons into the empty Pacific the initial Austronesian founders entered uninhabited territory, so the question of borrowing from substrate languages no longer existed.

The archaeological record pertinent for all this is quite detailed for Taiwan, the northern Philippines, and parts of eastern Indonesia (Bellwood 1997, 2004b), where Neolithic cultures progress ever southward and eastward through time, finally entering the western Pacific in the form of the Lapita culture of Melanesia and western Polynesia between 1300 and 800 B.C. (Kirch 2000). By this time rice had disappeared as a major crop in the wet equatorial climates of eastern Indonesia, where it also does not flourish today owing to a number of climatic factors. Founder Austronesian farming populations had by 1000 B.C. already undergone about 2,500 years of movement, adaptation, and intermixing with prior populations, the latter activity having recently come into prominence with respect to the mtDNA and Y chromosomes of Polynesians. Some of the major Polynesian lineages in both genomes are now believed to have originated in Island Southeast Asia rather than in Taiwan or China, attesting to some degree of incorporation of native populations into the spread process (Richards et al. 1998). However, neither the linguistics nor the archaeology provide much evidence for substantial cultural incorporation, so hypotheses for Polynesian origins must be handled with care and a great deal of multidisciplinary knowledge.

There is an additional archaeology and language correlation for the Austronesian spread in the Philippines and eastern Indonesia. Both the linguistic subgroups with their reconstructed protolanguage vocabularies of terms and meanings, and the archaeological record for eastern Island Southeast Asia and western Oceania, suggest a rapid expansion of both languages and cultures through far-flung coastal areas during the mid second millennium B.C. In linguistic terms, this would have led to a situation whereby the descendant languages would have been related to each other as a series of rake-like rather than tree-like subgroups. As already discussed, tree formations require the passing of considerable time and the production of considerable numbers of subgroup-defining innovations, as shown so graphically for Proto-Polynesian (Pawley 1996; Kirch and Green 2001). Rake-like patterns have few subgroup-defining innovations, and extremely widespread protolanguages can be very closely related, as shown for the major Malayo-Polynesian subgroups in Island Southeast Asia by Blust (1993–1994) and Pawley (1999).

The archaeological record for the speed of the Austronesian spread is based on numerous dated sites and assemblages, including, for example, a major archaeological project in the Batanes Islands in the northern Philippines that has succeeded in linking eastern Taiwan, Batanes, and the Philippines into a zone of north-to-south colonization and interaction from about 2000 B.C. onward (Bellwood et al. 2003; Bellwood and Dizon 2005). This zone corresponds extremely well with the reconstructed linguistic time and space coordinates for Proto-Malayo-Polynesian. The Austronesian dispersal from the northern Philippines to Samoa, a distance of 8,000 kilometers, appears to have required just over one millennium, between about 2000 and 800 B.C. on present evidence. Pawley (1999) indeed points comparatively to the very recent settlement of New Zealand, where the Maori settlement of the coastlines about A.D. 1250 appears—as observed archaeologically—to have been instantaneous. Austronesians in dispersal mode sometimes moved very rapidly.

On the other hand, we must not be fooled into thinking that the whole Austronesian expansion was a rapid process, even if certain stages of dispersal occurred with astonishing rapidity. Clearly, populations expanding over such vast areas of both sea and land faced long-term problems connected with adverse climates, hostile native populations (many numerous and well-equipped, e.g., on the Southeast Asian mainland and in New Guinea), unsuitable technology in need of improvement (hence the invention or adoption of the sail and outrigger, and eventually the double canoe), disease, bad luck, and many other factors which a good historical imagination will no doubt expose to view. Exact reasons are not essential to know at this juncture, but the overall chronology is important. From the period of Proto-Austronesian in Taiwan, at about 3000 B.C., to the settlement of New Zealand in about A.D. 1250, we have a passage of more than 4,000 years. The New Guinea mainland was not intensively settled by Austronesians until about 2,000 years ago (Ross 1988), and the Austronesian settlements of regions such as southern Vietnam, the Malay Peninsula, and Madagascar occurred well within the Southeast Asian Iron Age, between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500 (Blust 1994; Adelaar 1995). So the expansion of a language family on the scale of Austronesian was by no means a simple event. Nor was it trivial in its ultimate human outcomes.

Although the vast majority of linguists accept the above general reconstruction of Austronesian prehistory, there are dissenting voices among certain archaeologists who work in the western Pacific, and among a few geneticists (Terrell et al. 2001; Richards et al. 1998; Oppenheimer and Richards 2001). These scholars favor an Austronesian homeland in eastern Indonesia or western Melanesia, rather than the homeland in southern China and Taiwan favored here. Sometimes these differences reflect differential access to relevant data. But mostly they reflect deep-seated differences in research orientation. Scholars who develop their hypotheses from widespread patterns, such as the total Austronesian language family as discussed above, will always develop explanations for those patterns vastly different from scholars who work from localized data sets, such as an individual subgroup of languages or a site cluster in archaeology. That is the significance of scale (Bellwood 1996, 1997).

This field of archaeolinguistic research is not one in which we can expect absolute proof for suggested correlations, particularly when dealing with prehistoric societies. But firm hypotheses are always worthy of the research effort. The goals of archaeolinguistic research are laudable ones since they help us to interpret and understand fundamental developments and transitions in human prehistory.

This being the case, I finish this chapter with some short concluding observations about the practice of archaeolinguistics in general, and about the circumstances of language family origin and dispersal. If there are to be useful comparisons made between the archaeological and linguistic records, then it is necessary to focus on a number of key areas of potential correlation. Three of these have been discussed on several occasions above:

• Is there agreement between the geographical extent of a particular stage of language dispersal and a particular archaeological complex?

• Is there agreement between the material culture and economy recovered by archaeology with that reconstructed for a relevant protolanguage? This question is especially important at the foundation protolanguage stage for any major language family.

• Do the space and time dispersal trajectories as revealed by the archaeological record (via cultural trait distributions, absolute dates) agree with the phylogenetic subgrouping structure of the target language family?

If there is agreement on these correlations, then the archaeological and linguistic records can be mutually supportive.

That archaeology and linguistics can reach balanced and fully bidisciplinary conclusions is amply demonstrated by the recent study of Kirch and Green (2001) on the reconstruction of the social and material correlates of Proto-Polynesian society. Admittedly, Polynesia offers a classic laboratory-like—and unusual—situation, with bounded island societies which still descend today in unbroken lines of descent from the first founders, high degrees of language cognacy and archaeological assemblage relatedness, and a general absence of heavy borrowing from non-Austronesian sources. The archaeolinguistic prehistory of most of the rest the world is far more difficult to reconstruct than that of Polynesia, but research strategies that can be seen to work for this area must surely be given a chance to work elsewhere, even among the furious population maelstroms which have occupied some of the continents.

Finally, turning to issues of language family origin and dispersal, it has been demonstrated that the foundation layers of the major language families simply could not have spread from origins to distant prehistoric boundaries without some component of population movement involving native speakers, no matter how much reformulation of populations and cultures we allow via interaction and standstills along the way. However, no expanding population in prehistory could ever have exterminated completely, with no genetic carryover, a preexisting population, whether the situation consisted of farmers expanding among foragers, or farmers expanding among other farmers. This does not imply that interactions between incoming populations and residents were always peaceful; the archaeological and ethnographic records for aggressive behavior are extensive and do not pertain only to state-level societies (Keeley 1996; LeBlanc 2003).

Taking these factors into account, I have recently discussed agriculturalist language family origins and dispersals (Bellwood 2001, 2004a, 2005) with respect to four spatio-temporal zones, these being (1) homeland/starburst zones from which language families and agricultural economies spread outward; (2) spread zones of rapid flow of agricultural populations and languages with little resistance from prior populations; (3) friction zones where indigenous substrate phenomena feature strongly, either because of economic marginality or the demographic strength of prior populations; and finally (4) the “beyond” zones where the descendants of onetime farming populations flowed over the edge into environments unsuitable for agriculture (e.g., southern New Zealand, interior Borneo, the American Great Basin). These zonal concepts, while designed to deal with agriculturalist expansion, can be applied to the origin and dispersal history of any language family since the basic social and demographic requirements for language spread still hold.

1. For sociolinguistic discussions of what happens when languages come into contact, see Dixon and Aikhenvald 2001; Muhlhausler 1986; Ross 1997; Thomason and Kaufman 1988.

2. The language families discussed in this chapter are generally well-behaved and agreed by most linguists to have a clear-cut and noncontroversial existence. Language relationships are traceable, subgroups are definable, and spatio-temporal evolutionary scenarios can be constructed, even if linguists disagree on the finer details. But some language families do not behave so well, and disputes over them can grow heated. A good example concerns the Pama-Nyungan languages of the greater part of Australia: are they a true “genetic” language family with a recent history of spread, or do they merely reflect long-term interaction without major interruption since Australia was first settled in the Late Pleistocene? These issues are discussed in McConvell and Evans 1996; Dixon 1997.

3. As stated by Hines (1998:284), “I can see no reason to resist the notion that in the vast periods of prehistory, and over the vast geographical ranges of the world–s major language phyla, dispersal, isolation (in my view the critical factor) and divergence were dominant trends.”

4. This is an issue too complex to argue in detail here, but it seems inherently likely that any population actively engaged in expansion, as in recent situations in Australia and the Americas, will stress social ties with co-migrants as well as the sharing of language and history. This does not mean a total unwillingness to interact with native populations; neither does it mean that native populations will never assimilate or contribute positively to the new social order. Indeed, in prehistoric situations one might expect a great deal of fruitful interaction, rather than the high levels of exclusivity recorded in many nineteenth-century colonial societies.

5. It is not possible here to discuss every language family in the world. Research discussing families not discussed here, combining in many cases both archaeological and linguistic information, can be accessed via Bellwood 2004; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Diamond 1997; Ehret and Posnansky 1984; Ehret 1998; Hill 2001; McConvell and Evans 1997; Nettle 1999; Blench and Spriggs 1997–1999.

6. Clearly, some lingua francas and national languages have spread rapidly within modern states as a result of educational policy, literacy, mass media, and sociolinguistic status. But these national languages do not normally replace all native vernaculars, except in situations of strong domination and assimilation. Language loyalty is a significant factor in sociolinguistics (Errington 1998; Heath and Laprade 1982; Schooling 1990; Smalley 1994), and strong, functioning societies with continuing indigenous traditions do not easily abandon their languages. My own view, with Coleman (1988), and Nettle (1999), is that elite dominance as a process for language spread in prehistory can have been no more successful than it was for the Normans, the Greek colonies, the Romans, or the Mongols—not very successful at all.

7. Sails and outriggers are uncertain reconstructions for Proto-Austronesian. Taiwan has suffered extensive language extinction as a result of mass immigration of Chinese settlers since the seventeenth century, and knowledge of its Austronesian languages is correspondingly reduced.

Adams, Jonathan, and Marcel Otte. 1999. Did Indo-European languages spread before farming? Current Anthropology 40: 73–77.

Adelaar, K. Alexander. 1995. Borneo as a crossroads for comparative Austronesian linguistics. In Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, and Darrell Tryon, eds., The Austronesians, 75–95. Canberra: Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Ammerman, Albert, and L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza. 1973. A population model for the diffusion of early farming in Europe. In Colin Renfrew, ed., The explanation of culture change, 343–357. London: Duckworth.

———. 1984. The Neolithic transition and the genetics of populations in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Anthony, David. 1995. Horse, wagon, and chariot: Indo-European languages and archaeology. Antiquity 69: 554–564.

Bakker, Peter. 2001. Rapid language change: Creolization, intertwining, convergence. In Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask, eds., Time depth in historical linguistics 2: 109–140. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Bellwood, Peter. 1991. The Austronesian dispersal and the origin of languages. Scientific American 265(1): 88–93.

———. 1994. An archaeologist’s view of language macrofamily relationships. Oceanic Linguistics 33: 391–406.

———. 1996. Phylogeny and reticulation in prehistory. Antiquity 70: 881–890.

———. 1997. Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian archipelago. Rev. ed. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

———. 2000. The time depth of major language families: an archaeologist’s perspective. In Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask, eds., Time depth in historical linguistics 1: 109–140. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

———. 2001. Early agriculturalist population diasporas? Farming, languages, and genes. Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 181–207.

———. 2004a. First farmers: The origins of agricultural societies. Oxford: Blackwell.

———. 2004b. The origins and dispersals of agricultural communities in Southeast Asia. In Ian Glover and Peter Bellwood, eds., Southeast Asia: From prehistory to history, 21–40. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

———. 2005. First Farmers. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bellwood, Peter, and Eusebio Dizon. 2005. The Batanes Archaeological Project and the “Out of Taiwan” hypothesis for Austronesian dispersal. Journal of Austronesian Studies 1: 1–32.

Bellwood, Peter, and Colin Renfrew (eds.). 2003. Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Bellwood, Peter, Janelle Stevenson, Atholl Anderson, and Eusebio Dizon. 2003. Archaeological and palaeoenvironmental research in Batanes and Ilocos Norte Provinces, Northern Philippines. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 23: 141–162.

Benedict, Paul. 1975. Austro-Thai language and culture. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

Black, Ronald, William Gillies, and Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh, eds. Celtic connections: Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Celtic Studies. Vol. 1, Language, literature, history, culture. East Linton: Tuckwell.

Blench, Roger, and Matthew Spriggs (eds.). 1997–1999. Archaeology and language 1–4. London: Routledge.

Blust, Robert. 1977. The Proto-Austronesian pronouns and Austronesian subgrouping: A preliminary report. Working Papers in Linguistics 9, no. 2. Honolulu: Department of Linguistics, University of Hawai’i.

———. 1984–1985. The Austronesian homeland: A linguistic perspective. Asian Perspectives 26: 45–67.

———. 1993. Central and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian. Oceanic Linguistics 32: 241–293.

———. 1994. The Austronesian settlement of mainland Southeast Asia. In K. L. Adams and T. Hendak, eds., Papers from the 2nd Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistic Society, 25–83. Tempe: Arizona State University: Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

———. 1995. The prehistory of the Austronesian-speaking peoples. Journal of World Prehistory 9: 453–510.

———. 1996. Beyond the Austronesian homeland: The Austric hypothesis and its implications for archaeology. In Ward H. Goodenough, ed., Prehistoric settlement of the Pacific, 117–40. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

———. 1999. Subgrouping, circularity, and extinction: Some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics. In Elizabeth Zeitoun and Paul Jen-kuei Li, eds., Selected papers from the 8th International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, 31–94. Taipei: Symposium Series of the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica.

———. 2000. Why lexicostatistics doesn’t work. In Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask, eds., Time depth in historical linguistics, 2: 311–332. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Campbell, Lyle. 1999. Nostratic and linguistic palaeontology in methodological perspective. In Colin Renfrew and Daniel Nettle, eds., Nostratic: Examining a linguistic macrofamily, 179–230. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Childe, V. Gordon. 1926. The Aryans. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner.

Coleman, R. 1988. Comment on “Archaeology and Language” by Colin Renfrew. Current Anthropology 29: 437–468.

Crosby, Alfred. 1986. Ecological imperialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diamond, Jared. 1997. Guns, germs, and steel. London: Jonathan Cape.

Diamond, Jared, and Peter Bellwood. 2003. Farmers and their languages: The first expansions. Science 300: 597–603.

Diebold, A. R. 1987. Linguistic ways to prehistory. In Susan Nacev Skomal and Edgar C. Polomé, eds., Proto Indo-European: The archaeology of a linguistic problem, 19–71. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1997. The rise and fall of languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W., and A. Aikhenvald (eds.). In press. Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance: Problems in comparative linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dolgopolsky, Aharon. 1993. More about the Indo-European homeland problem. Mediterranean Language Review 6: 230–248.

Driver, H. E. 1972. Indians of North America. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dyen, Isidore. 1965. A lexicostatistical classification of the Austronesian languages. International Journal of American Linguistics Memoir 19. Baltimore, MD: Waverly Press.

———. 1975. Linguistic subgrouping and lexicostatistics. The Hague: Mouton.

———. 1995. The internal and external classification of the Formosan languages. In P. J.-K. Li, D.-A. Ho, Y.-K. Huang, C.-W. Tsang, and C.-Y. Tseng, eds., Austronesian studies relating to Taiwan, 455–520. Symposium Series 3. Taipei: Academia Sinica, Institute of History and Philology.

Ehret, Christopher. 1998. An African classical age. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Ehret, Christopher, and Merrick Posnansky (eds.). 1982. The archaeological and linguistic reconstruction of African history. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Errington, Joseph. 1998. Shifting languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fortescue, Michael. 1998. Language relations across Bering Strait. London: Cassell.

Gamkrelidze, Thomas V., and Vjaceslav V. Ivanov. 1995. Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Gimbutas, Marija. 1985. The primary and secondary homeland of the Indo-Europeans. Journal of Indo-European Studies 13: 185–202.

———. 1991. Civilization of the goddess. San Francisco: HarperCollins.

Glover, Ian, and Peter Bellwood (eds.). 2004. Southeast Asia: From prehistory to history. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Gray, Russell, and Quentin Atkinson. 2003. Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426: 435–439.

Greenberg, Joseph. 1987. Language in the Americas. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gudschinsky, Sarah. 1964. The ABCs of lexicostatistics (glottochronology). In Dell H. Hymes, ed., Language in culture and society, 612–623. New York: Harper & Row.

Hale, Horatio. 1846. United States Exploring Expedition 1838–42: Ethnography and philology. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard.

Heath, S., and R. Laprade. 1982. Castilian colonization and indigenous languages: The cases of Quechua and Aymara. In Robert L. Cooper, ed., Language spread, 118–147. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Higham, Charles. 1996. Archaeology and linguistics in Southeast Asia. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 14: 110–118.

Hill, Jane. 2001. Proto-Uto-Aztecan: A community of cultivators in central Mexico? American Anthropologist 103: 913–934.

Hines, John. 1998. Archaeology and language in a historical context: The creation of English. In Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, eds., Archaeology and language, 2: 283–294. London: Routledge.

Keeley, Lawrence. 1996. War before civilization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kirch, Patrick Vinton. 2000. On the road of the winds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kirch, Patrick Vinton, and Roger Green. 2001. Hawaiki: Ancestral Polynesia: An essay in historical anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krantz, Grover. 1986. The geographical development of European languages. New York: Peter Lang.

Kulick, Don. 1992. Language shift and cultural reproduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LeBlanc, Steven. 2003. Constant battles. New York: St. Martin’s.

Mallory, James. 1989. In search of the Indo-Europeans. London: Thames & Hudson.

———. 1997. The homelands of the Indo-Europeans. In Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, eds., Archaeology and language 1: 93–121. London: Routledge.

McConvell, Patrick, and Nicholas Evans (eds.). 1996. Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Megaw, Ruth, and Vincent Megaw. 1999. Celtic connections past and present. In R. Black, ed., Celtic connections, 20–81.

Michalove, P. A., S. Georg, and A. Manaster Ramer. 1998. Current issues in linguistic taxonomy. Annual Review of Anthropology 27: 451–472.

Nettle, Daniel. 1999. Linguistic diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nichols, Johanna. 1997. Modeling ancient population structures and movements in linguistics. Annual Review of Anthropology 26: 359–384.

———. 1998. The Eurasian spread zone and the Indo-European dispersal. In Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, eds., Archaeology and language 2: 220–266. London: Routledge.

Oppenheimer, Stephen, and Martin Richards. 2001. Fast trains, slow boats, and the ancestry of the Polynesian islanders. Science Progress 84: 157–181.

Pachori, Satya S. 1993. Sir William Jones: A reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pawley, Andrew. 1996. On the Polynesian subgroup as a problem for Irwin’s continuous settlement hypothesis. In J. M. Davidson, G. Irwin, F. Leach, A. Pawley, and D. Brown, eds., Oceanic culture history, 387–410. Special publication. Dunedin: New Zealand Journal of Archaeology.

———. 1999. Chasing rainbows: Implications of the rapid dispersal of Austronesian languages. In Elizabeth Zeitoun and Paul Jen-kuei Li, eds., Selected papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, 95–138. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica.

Pawley, Andrew, and Malcolm Ross. 1993. Austronesian historical linguistics and culture history. Annual Review of Anthropology 22: 425–459.

———. 1995. The prehistory of the Oceanic languages. In Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, and Darrell Tryon, eds., The Austronesians, 39–74. Canberra: Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Peiros, Ilya. 1998. Comparative linguistics in Southeast Asia. Series C-142. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Reid, L. 1984–1985. Benedict’s Austro-Tai hypothesis: An evaluation. Asian Perspectives 26: 19–34.

———. 1996. The current state of linguistic research on the relatedness of the language families of East and Southeast Asia. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 15: 87–92.

Renfrew, Colin. 1987. Archaeology and language. London: Jonathan Cape.

———. 1991. Before Babel: Speculations on the origins of linguistic diversity. Cambridge Archaeology Journal 1: 3–23.

———. 1996. Language families and the spread of farming. In D. Harris, ed., The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia, 70–92. London: UCL Press.

———. 1999. Time depth, convergence theory, and innovation in Proto-Indo-European. Journal of Indo-European Studies 27: 257–293.

———. 2000. At the edge of knowability. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 10: 7–34.

Renfrew, Colin, and Katie Boyle (eds.). 2000. Archaeogenetics. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Renfrew, Colin, April McMahon, and Larry Trask (eds.). 2000. Time depth in historical linguistics. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Renfrew, Colin, and Daniel Nettle (eds.). 1999. Nostratic: Examining a linguistic macrofamily. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Richards, Martin. 2003. The Neolithic invasion of Europe. Annual Review of Anthropology 32: 135–162.

Richards, M., V. Macaulay, E. Hickey, E. Vega, B. Sykes et al. 2000. Tracing European founder lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool. American Journal of Human Genetics 67: 1251–1276.

Richards, M., S. Oppenheimer, and B. Sykes. MtDNA suggests Polynesian origins in eastern Indonesia. American Journal of Human Genetics 63: 1234–1236.

Ross, Malcolm D. 1988. Proto Oceanic and the Austronesian languages of Melanesia. Series C-98. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

———. 1996. Reconstructing food plant terms and associated terminologies in Proto Oceanic. In John Lynch and Fa’afo Pat, eds., Oceanic studies: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Oceanic Linguistics, 163–221. Series C-133. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

———. 1997. Social networks and kinds of speech community event. In Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, eds., Archaeology and language 1: 209–262. London: Routledge.

Ross, Malcolm D., Andrew Pawley, and Meredith Osmond. 1998. The lexicon of Proto Oceanic. Vol. 1, Material culture. Series C-152. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Ruhlen, Merritt. 1987. A guide to the world’s languages. Vol. 1. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sagart, Laurent. 1994. Proto-Austronesian and Old Chinese evidence for Sino-Austronesian. Oceanic Linguistics 33: 271–308.

Sapir, Edward. 1916. Time perspective in aboriginal American culture. Anthropological Series 13. Canada, Department of Mines, Geological Survey Memoir 90. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau.

Schooling, Stephen J. 1990. Language maintenance in New Caledonia. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics/University of Texas-Arlington.

Smalley, William A. 1994. Linguistic diversity and national unity: Language ecology in Thailand. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sverdrup H., and R. Guardans. 1999. Compiling words from extinct non-Indo-European languages in Europe. In V. Shevoroshkin and P. Sidwell, eds., Historical linguistics and lexicostatistics, 201–257. AHL Studies in the Science and History of Language 3. Melbourne.

Sykes, Brian. 1999. The molecular genetics of European ancestry. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B354: 131–140.

Terrell, John, Kevin Kelly, and Paul Rainbird. 2001. Foregone conclusions? In search of “Papuans” and “Austronesians.” Current Anthropology 42: 97–124.

Thomas, Nicholas, Harriet Guest, and Michael Dettelbach (eds.). 1996. Observations made during a voyage round the world, by Johann Reinhold Forster. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Thomason, Sarah, and Terrence Kaufman. 1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Thurston, William. 1987. Processes of change in the languages of north-western New Britain. Series B-99. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Tryon, Darrell. 1995. Proto-Austronesian and the major Austronesian subgroups. In Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, and Darrell Tryon, eds., The Austronesians, 117–138. Canberra: Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Warnow, T. 1997. Mathematical approaches to comparative linguistics, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94: 6585–6590.