Independent cinema feels right at home in Austin. Born of a revolution, Texas resisted the union of its Lone Star state with the rest of America for almost a decade, and even then and ever since its capital city of Austin has symbolised resistance to exploitation by the incursive forces that surround it. Americans come from all over the world they say, but Texans come from Texas. Its capital city was named after Stephen F. Austin, a cautious and peaceful sort who led the colonisation of the region by settlers. Fortunes from steers, cotton and oil sponsored the construction of the Texas State Capitol, the University of Texas at Austin and the damming of the Colorado River to make the downtown Lady Bird Lake that blooms as much as any symbolic oasis should. Urban legend has it that the city’s slacker community was formed when rednecks and hippies hybridised over marijuana at a concert by fellow Austinite Willie Nelson, the leader of the ‘outlaw’ country movement of the 1970s. Today left-leaning Austin is a blue dot in a red state, still peopled with folk whose slacking is a charming distraction from the city’s modernity, although lately the area has challenged San Francisco’s Silicon Valley for high-tech industries that are largely manned by those who came to Austin to drop out but could not stand the pressure of doing nothing. Locating Linklater in Austin is vital, for his films not only emerged from the slacker culture of the mid-1980s but enunciate its undermining of the ideologies of late capitalist materialism via their form, content, style and themes. In this, Linklater applied the techniques associated with representations of alienation in post-war European cinema to a specifically regional concept of American cinema that was also informed by existentialist and Marxist undercurrents. Consequently, his films associated slacker culture with the deliberate wider critical project of communal estrangement from political and national hegemonies and reterritorialised a part of America that would find common identity and cause in the development of independent cinema.

The notion of independence in American cinema had existed since the mid-1910s as an industrial demarcation of films made by small production companies unrelated to the major studios. It also described films by such illustrious figures as Samuel Goldwyn and David O. Selznick, who produced films independently but negotiated their distribution with the majors. Subsequently, poverty row studios of the 1930s and 1940s such as Monogram and First National produced low-budget westerns and thrillers, while exploitation companies such as James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff’s American International Pictures (AIP) began producing B-films for double-bills in the 1950s. In 1970 Roger Corman, who had directed a notable series of adaptations of the work of Edgar Allan Poe for AIP, established New World Pictures as a small, independent production and distribution studio whose films paid attention to marginalised, rebellious, adolescent characters and were an influence on Linklater. By the 1980s, however, the term independent ‘started to signify films that ventured into themes largely untouched by Hollywood, that assimilated the influence of the experimental and art traditions, and that voiced minority perspectives’ (Suárez 2007: 40). Even so, from

Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) to

Slumdog Millionaire (Danny Boyle, 2009) the majors have always been willing to distribute independently produced films, reasoning that potential profit makes a good choice of ‘indie’ a safe investment because the risk is limited to its distribution.

1 The major studios are also keen to poach aesthetics, themes and filmmakers from the independent sector as exemplified by Geoff King’s apt description of

Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000) as ‘a $50 million Dogme movie’ (2009: 158). The independent sector also provides market research on the changing tastes and demographics of its audience, which has been revealed as high-spending, ‘educated adults who [are] interested in film as an aesthetic object’ (Suárez 2007: 46) and whose idea of creativity is sympathetic to theories of auteurism. In the 2000s the term ‘independent’ shifted to describe what King identifies as:

Indiewood, an area in which Hollywood and the independent sector merge or overlap. […] From one perspective [films produced in this area] offer an attractive blend of creativity and commerce, a source of some of the more innovative and interesting work produced in close proximity to the commercial mainstream. From another, this is an area of duplicity and compromise, in which the ‘true’ heritage of the independent sector is sold out, betrayed and/or co-opted into an offshoot of Hollywood. (2009: 1)

Mike Atkinson concludes that ‘any consideration of the indie climate in the U.S. must begin with this identity crisis’ (2007: 18) that is perhaps exemplified in the manner by which the populist brand of independent cinema has become a non-threatening badge of quirkiness that

Juno (Jason Reitman, 2007), for example, uses to make palatable a parable of anti-abortionist conservatism. Even an oddly-shaped movement such as Mumblecore, whose digitised disciples or ‘Slackavetes’ of Linklater and Cassavetes have churned out no-budget variations on

Before Sunrise using digital cameras, twenty-something amateur casts and improvisation, has failed to offer much of an update on the cinematic declarations of its prophets.

2However, back in the 1970s, films made by enthusiastic amateurs from far-flung places like Texas were not called independent but regional cinema. Their independence was not an ethical, financial or creative choice but a consequence of localism. Regional cinema could be identified as such for its authentic locations, characters, themes and

mise-en-scène, its home-based cast and crew, its accent and languages as well as its mostly localised financing, modest ambitions and particularly regional sensibilities, themes and characters. Regional filmmakers lacked the critical support of a

Cahiers du cinéma, a

cinémathèque or anything like access to distribution, but they did have the lightweight cameras and sound recording equipment that had enabled the French New Wave. For example, fifteen years before Linklater’s

Slacker was erroneously acclaimed as a new breed of film from Nowheresville, another Austinite named Eagle Pennell had marshalled talented amateurs to make films featuring ordinary folk whose culture was absent from what passed for Texas in Hollywood. Film such as

Giant (George Stevens, 1956) and countless westerns offered grand vistas and remembered the Alamo; but only

Hud (Martin Ritt, 1963) and

The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971), which were both adapted from novels by Texan Larry McMurtry, had come anywhere near to genuine street level tensions and smalltown mores.

3 The borderland novels of Cormac McCarthy had not yet impacted,

4 nor had contemporary Tex-Mex film dramas such as

Lone Star (John Sayles, 1996),

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (Tommy Lee Jones, 2005) and the adaptation of McCarthy’s

No Country for Old Men (Ethan & Joel Coen, 2007). But forget the Alamo, it was the resolutely un-mythical, working-class Austinite, red of neck and blue of collar, that was the subject of Eagle Pennell’s

A Hell of a Note (1977),

The Whole Shootin’ Match (1978) and

Last Night at the Alamo (1983). These warm but downcast features reveal a people so rooted in a time and place that a collective identity is discernible in the gait of the films themselves. Long, loose takes of bullshitting urban cowboys are imbued with ‘a kind of deeply pessimistic Southern fundamentalist Protestant view of humanity’ (Odintz 2009: 19). But there is humour here too. All the opportunistic failures, bar-room

braggadocio, defeatist advances on weary females and everyday chores of Pennell’s characters reveal them as a generation lost between the tenant farmers of the 1950s and the untethered Wooderson (Matthew McConaughey) of Linklater’s

Dazed and Confused. If he had been able to free himself from the alcoholism that blighted his working relationships and killed him in 2002, Pennell might have served as a trailblazer for Linklater instead of the brief flare and fade that still made for an influential legend.

As Pennell discovered, there was only a ragged circuit of film festivals in the 1970s. Instead, films like his were predestined for limited runs in sympathetic local cinemas that occasionally inspired word of mouth. In turn this encouraged filmmakers to apply and submit to festivals, where critics might be open to seeing regional films as genuine American cinema. Hollywood’s contemporaneous attempts to attract audiences by employing independent filmmakers had resulted in what Robin Wood called ‘the incoherent narrative’ of 1970s cinema, in which ‘the drive towards the ordering of experience [was] visibly defeated’ (1986: 47). Yet genuine empirical disorder was the natural subject of regional cinema like Pennell’s, which reflected smalltown life as it was, made up as it went along. Whether by lack of training, disdain for formulaic narrative, a piecemeal production schedule or simply an unhurried experimentation with filmmaking that did not broker any realistic possibility of ever reaching an audience, the regional cinema of mavericks such as Pennell flirted with Modernism in responding to its own criteria and limitations. This was not the obscure, experimental cinema of Stan Brakhage (

Dog Star Man, 1961–64), though it was no less unconventional; nor was it the militantly Queer, underground cinema of Kenneth Anger (

Lucifer Rising, 1972), although its cultural identity was no less specific. Pennell lacked the work ethic of John Cassavetes, whose performance of independent auteurism contributed to the purist, romantic tenet of opposition to Hollywood, but like Cassavetes and Linklater he was one of the few who quit talking about something and did it. His collaborative cohort of Austinite cast and crew made

The Whole Shootin’ Match for about $20,000 and watched it at the Dobie, Austin’s off-campus movie theatre on Guadalupe Street. Thereafter, popular response prompted a screening at the USA Film Festival in Dallas in April 1978 and a new festival held in Salt Lake City in Utah in September of that year, where it featured in the sidebar Regional Cinema: The New Bright Hope alongside the New York-based

Girlfriends (Claudia Weill, 1978) and

Martin (George A. Romero, 1977) from Pittsburgh. The suggestion was that the regionalism of these films was alternative and inseparable from their meaning. Robert Redford’s viewing of

The Whole Shootin’ Match in the Utah festival so inspired him to want to nurture ‘strays like this’ (Cullum 2009: 23) that he moved the festival to Park City and changed its name to one of association with his Sundance Institute, whose precise aim was to encourage new breeds of regional filmmaking. This objective would be realised when the Pennell-inspired

Slacker was nominated for the Sundance Grand Jury Prize for Dramatic Film in 1991.

Before Sundance, regional filmmaking in America was not a movement or a revolution but a homemade adventure that meant its parochialism was sometimes the punchline for a rare audience from elsewhere. Only occasionally might a regional filmmaker such as Austinite Tobe Hooper manage to transcend the stereotypes of Texans by turning them on their leather-faced heads in

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), whose associate producer (Kim Henkel), sound technician (Wayne Bell), and assistant cameraman (Lou Perryman) had each learnt their skills as part of Pennell’s crew. Yet Hooper’s success was not just generic; it was also a terrifying response to what most audiences, festivals and critics disdained about rural America and, as such, was a particularly subversive example of regional cinema. Other regional filmmakers who escaped the fate of obscurity were mostly urbanites by comparison: Baltimore had John Waters (

Desperate Living, 1977), New York had John Sayles (

The Return of the Secaucus Seven, 1980) and Los Angeles had Alan Rudolph (

Welcome to LA, 1976), while New York was sufficiently multi-cultural as to foster films featuring the streetwise but lost souls of John Cassavetes, the immigrants and nomads of Jim Jarmusch and the black working class of Charles Burnett. The catch-all title of ‘independent’ cinema did such regional filmmakers a disservice by dislocating them from their cultural specificity and grouping them in opposition to one place called Hollywood instead. As Marsha Kinder explains, the notion of regional cinema may be situated within a local and global interface but it is also an ideological construct and a ‘relativistic concept’ that is fluid and problematic because ‘like a linguistic shifter, “regional” means “marginal” in relation to some kind of geographic center or dominant cultural practice, and in the case of cinema, that frequently means Hollywood’ (1993: 388).

The eternally problematic term ‘independent’ has endured, however, while the notion of regional cinema has not. Competing ideas of independence in American cinema by Emanuel Levy (1999), King (2005, 2009), Yannis Tzioumakis (2006) and John Berra (2008) amongst others have each wrestled with the criteria. Tzioumakis sees:

American independent cinema as a discourse that expands and contracts when socially authorised institutions (filmmakers, industry practitioners, trade publications, academics, film critics, and so on) contribute towards its definition at different periods in the history of American cinema. (2006: 11)

King is more practical and empirical in demanding an industrial location, formal and aesthetic strategies based upon ‘a highly stylised minimalism that draws attention to itself as a formal-artistic device’ (2005: 82) and a relationship to a ‘broader social, cultural, political or ideological landscape’ (2005: 2). His correlated observation that ‘independent’ cinema stakes ‘a claim to the status of something more closely approximating the reality of the lives of most people’ (2005: 67) suits regional cinema too. Nevertheless, the term ‘regional’ still fails to resonate in America, unlike in Europe, where provincial television broadcasters have played a vital role in the funding and dissemination of their respective regional cinemas. In the absence of any similar, coherent funding, the independent spirit that may be identified in some American filmmakers of the 1970s and onwards was arguably coincidental. Their financing was haphazard, being mostly a particularistic collage of savings, loans, inheritances, local government and federal grants, public service broadcasting and, more recently, maxed-out credit cards. It was not until the success of Steven Soderbergh’s

sex, lies and videotape (1989) at the Sundance and Cannes film festivals in 1989 that ‘the existence of significant available institutional support’ (Tzioumakis 2006: 254) and the potential commercial and critical viability of independent cinema outside America became apparent. This new awareness of funds and markets for a small-scale, intimate, character-based American cinema led to ‘questions of aesthetics [assuming] an increasingly prominent position in the discourse of American independent cinema’ (Tzioumakis 2006: 266). In turn, this contributed to a criteria for the discrimination of ‘indies’ from studio films, which included marketable similarities to the kind of European cinema that based itself on expression of thought and the negotiation of identities as opposed to a more mainstream deployment of physical expression in the negotiation of obstacles. Linked to this was the increasingly auteurist approach of many critics and a cine-literate audience, who identified the supposed autonomy of filmmakers like Soderbergh as a riposte to the perception of a blockbuster mentality and its concomitant ‘dumbing down’ of audiences by the major studios. Soderbergh, who appears as himself (albeit rotoscoped) in Linklater’s

Waking Life, was briefly acclaimed alongside Jarmusch (see Suárez 2007) and Sayles (see Bould 2009) as the inheritor of Cassavetes’s noble cause (see Charity 2001), but even in Robin Hood mode or Kafkaesque conflict with the major studios most American filmmakers were unable to conquer the geographical impracticality of adopting any collective identity that was much more than a media construct to which they occasionally re-subscribed at festivals.

Linklater’s

Slacker evoked an altogether different collective identity, one that rejected competition. Somewhat ironically therefore, the film was itself initially rejected by Sundance because of festival director Alberto García’s demurral, as well as the festivals of Telluride and Toronto. It was, however, shown as a work-in-progress at the Independent Feature Film Market in New York in October 1989, where it inspired a $35,000 advance from the Cologne-based WDR (Pierson 1996: 185). WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk/West German Broadcasting) was one of the German networks that pioneered the film and television synergy later adopted by the UK’s Channel Four and the deal was possibly due to some vestiges of empathy with the ethos of slacking that resonates in modern German cinema. This is evident from Wim Wenders’ road movies

Alice in den Städten (

Alice in the Cities, 1974),

Falsche Bewegung (

Wrong Move, 1975) and

Im Lauf der Zeit (

Kings of the Road, 1976) to the recent

Die fetten Jahre sind vorbei (

The Edukators, 2004) directed by Hans Weingartner, who was production assistant on Linklater’s

Before Sunrise in which he also appears in a blue shirt chatting at a table in the café scene.

5 However, the virginal notion of ‘independent’ cinema that is attached to

Slacker does not survive in the career of Linklater, who has always drifted in response to the sort of collaboration that he could count on in Austin or could negotiate with the major studios. Following Pierre Bourdieu, Berra claims that ‘independence’ is only valid in terms of ‘the field of restricted production, an artistically heightened, if economically subservient, means of artistic expression’ (2008: 71). Yet, although valid, this rather ignores the complex negotiations between production and distribution throughout Linklater’s career that dooms any attempt to determine the degree of his independence to inexactitude.

The Hollywood studios have a reach that makes global distribution as easy as ‘pushing at an open door’ (Cooke 2007: 4), whereas a regional filmmaker will struggle to get picked for a festival. Between these extremes Linklater’s career has demonstrated that the production and distribution sectors are rarely cleanly aligned and that a wide range of strategies are possible, if not always successful. For example, his first full-length feature

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books was made for $3,000 from savings and not distributed, whereas

Slacker was made for $23,000 with loans and small grants and reached audiences via its successful resubmission to Sundance and a specialist independent distributor. However, the same strategy proved problematic with

Me and Orson Welles, which was made with a large grant from the Isle of Man Media Development Fund (MDF) and a co-production deal between several companies including Linklater’s own Detour Filmproduction. It may have charmed audiences at the 2008 Toronto International Film Festival but hesitant distributors meant that its release was delayed a full year outside Canada (Anon. 2008).

Dazed and Confused was different: a production deal with Universal that turned sour when the nonplussed studio dumped its distribution on its own subsidiary Gramercy, which had been formed that same year to distribute PolyGram pictures in the USA and Canada.

6 Learning from this, Linklater made

Before Sunrise and

SubUrbia as part of a ‘hands-off’ deal with Castle Rock Entertainment, which had been established as an independent production company in 1987 by filmmaker Rob Reiner amongst others, but with the financial backing of Columbia Pictures and Nelson Entertainment. Its independence lasted as long as Columbia could afford to let its losses accrue and in 1994 Castle Rock was bought by Warner Brothers Entertainment, which assumed domestic distribution rights while Universal handled the foreign.

7 Like

Slacker, Before Sunrise screened at Sundance, but with major distributor Columbia already attached.

In contrast,

The Newton Boys was a Twentieth Century Fox production that bombed despite wide distribution. In 2001, a slyer Fox placed

Waking Life, which it co-produced with the Independent Film Channel (IFC), with its own Fox Searchlight Pictures, which had been formed to handle films with difficult or challenging subject matter such as this. Another tack taken was that for Linklater’s

Tape, which resulted from a collective whose semi-acronym InDigEnt made a badge of verifiable poverty out of the more prosaic Independent Digital Entertainment.

Tape’s distribution was fragmentary with the IFC again stepping in alongside Lions Gate, Metrodome and Palace. At the other extreme,

The School of Rock was made for Paramount Pictures with most international distribution going to United International Pictures (UIP), whereas

Bad News Bears was green-lit on the profits from

The School of Rock and always locked in to a safe pre-production distribution deal with Paramount and UIP. By 2003 Warner Brothers had taken over worldwide distribution of films produced under the Castle Rock label and done so as either Warner Brothers (domestic) or Warner Brothers International (foreign) or Warner Independent Pictures (oxymoronic). Nevertheless, what was left of Castle Rock as a tiny production unit in Time Warner Incorporated (the third largest media and entertainment conglomeration in the world) still managed to ensure for Linklater a modicum of independence for the tiny $10 million budget production of

Before Sunset in 2004 and also collaborated with a dozen or more producers and executive producers for

Bernie in 2010, which emulated Linklater’s mixing and matching of independent financing for

Fast Food Nation from BBC Films, Han Way and Participant Productions. Distribution of

Fast Food Nation was even more of a collage, with rights going to Fox Searchlight Pictures in the USA, Focus Films in Hong Kong, Tartan in the UK and a wide variety of bidding and favourited domestic distributors in other countries. Finally, muddying the mix even further was

A Scanner Darkly, which was a co-production between Section Eight Productions and Warner Brothers under the aegis of Warner Independent Pictures that, like Fox Searchlight Pictures, was formed to distribute domestic and foreign films that did not fit easily alongside

Harry Potter and the major’s other main attractions.

8 The involvement of Section Eight Productions, meanwhile, brings this obstacle race full circle with Linklater once again making use of Steven Soderbergh’s tail wind. Founded in 2000 by Soderbergh and George Clooney in order to gain some semblance of independence for the films that mostly they themselves wished to make, Section Eight Productions operated on a ‘one for us, one for the studio’ production and distribution balancing act with Warner Brothers.

9All things considered, purists might well argue that the only truly independent American film is one that is never seen outside of the filmmaker’s immediate family, close friends and festivals; in which case (at least until its inclusion as an extra feature on the Criterion Collection DVD of

Slacker) the only film of Linklater’s that qualifies is

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books. Yet, despite the huge hillside sign, Hollywood should not be seen as a sovereign state or centralised government within the USA but as a collusion of competing international conglomerates that market the brand name Hollywood as the product of a specific, perpetually sun-blessed place, unchanged since the heyday of the moguls. Moreover, ‘the majority of the major studios themselves only have limited ties to the Hollywood area of Los Angeles’ (Cooke 2007: 6), which reveals Hollywood as an illusory opponent for supporters of ‘independent’ cinema. In truth, this idea of ‘Hollywood’ (which therefore warrants inverted commas too) is more globalised than globalising. Its generic formulas may seem as easily transferable to international markets as the gimmick of the latest game show, but it is actually ‘Hollywood’ that has been formed and flavoured by such global demands for its product that multiplexes worldwide have become pantheons of its pastiche. Since the decline of the western (perhaps the only true American genre), ‘Hollywood’ films have been gaily unmasking themselves as faceless investments in universality with recent colours being Bollywood, Marvel and Manga. Nevertheless, as Paul Cooke observes, the extant perception of a division between ‘Hollywood’ and the rest of the world is ‘generally seen in terms of a cultural hierarchy, with Hollywood producing expensive, populist “low culture”, while the rest of the world offers spectators lower-budget, more demanding “high cultural” fare aimed at a discerning “art house” audience’ (2007: 3). He also observes that ‘it is by Hollywood’s standards that we define what we mean by mainstream film-making’ (2007: 5) and that, consequently, what is left is defined as ‘independent’ American cinema too. Berra notes a somewhat idealist response from audiences in the 1970s and 1980s that took independence to mean ‘both a mode of production and a mode of thinking relating to the financing, filming, distribution and cultural appreciation of modern film’ (2008: 9). Since then, however, he argues that:

The stranglehold which the Hollywood studios have over the film business has contributed to the ‘commercialization’ of American ‘independent’ cinema, the gradual erosion of its values, the restraint of its cultural impulse, and the labelling of a ‘movement’ that has become an invaluable aspect of Hollywood’s industry of mass production. (2008: 13)

Finally, Emanuel Levy diagnoses a highly selective mode of reception for ‘independent’ cinema by audiences in the 1990s that are ‘so eager to accept the existence of a form of “alternative” media, that [they] will largely ignore the corporate origins of such films’ (2001: 202). ‘Hollywood’, ‘independent’, ‘low culture’, ‘art house’, ‘commercialization’, ‘movement’, ‘alternative’: is anyone else fed up with all these inverted commas? At least, by definition, you know exactly where you are with regional cinema.

The success on tiny budgets of Sayles’

The Return of the Secaucus Seven (1980; $60,000), Spike Lee’s

She’s Gotta Have It (1986: $22,700), Linklater’s

Slacker (1991: $23,000), Nick Gómez’s

Laws of Gravity (1992: $32,000), Gregg Araki’s

The Living End (1992: $22,700) and Rose Troche’s

Go Fish (1994; approximately $15,000) was because each captured and communicated a realism that resulted from their innate regionalism and consequent social authenticity. They connected with empathetic audiences whose own realities had not (at least not yet) been deemed worthy of colonisation by the major studios. Although the distribution of these films was limited, their influence and reputation has endured by means of word of mouth, academic and critical interest, cult status, intertextuality, special edition DVDs from enterprising distributors and, most importantly, a connection with new generations able to empathise with the groups and individuals that these films portray. They may have had limited production resources and little hope of wide distribution, but each filmmaker shared what Linklater identified and empathised with in the films of Eagle Pennell: ‘He was kind of a folk artist who liked doing things in his own backyard. […] Here’s a guy who saw something unique about what was right in front of him’ (2009: 15). Analysis of the negotiation of independence in the career of Linklater must accept that definitions of the term are in constant flux, thereby obscuring a complete portrait of the filmmaker. Yet, despite the connotations of parochialism that mean Linklater himself ‘doesn’t like to be labelled a regional filmmaker’ (Pierson 1996: 185), the regionalism of his enterprise remains steadfast and hereditary.

Following the screening of Pennell’s The Whole Shootin’ Match at the 1980 Telluride Film Festival, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times described it as:

One of the best examples of a new regional American cinema (I call it the Wood-Burning Cinema) that’s been creating itself in the last few years. It was financed and made totally in Texas by Texans. […] It won’t turn up in neighbourhood theatres and may never be on TV, but it creates characters that are such ornery, dreaming, hopeless and precious failures that you can’t help sort of loving them. (1980)

The Whole Shootin’ Match never did play any neighbourhoods beyond Austin and was thought lost until 2009 when Watchmaker Films released a special edition DVD of a copy found in its co-writer’s shed. Then, the thirty years of mythicisation based on nostalgia, Ebert’s review and academic interest was found to be well-deserved, while the film’s intertextual relationship with

Slacker and

Dazed and Confused offered flavoursome corroborative evidence of a tradition of regional cinema in Austin. There had been other home-based Texan filmmakers besides Pennell and Hooper, such as David Schmoeller, who directed

Tourist Trap (1979), another notable horror film with a ‘special thanks to’ credit for Albert Band, who directed the western

She Came to the Valley (1979 aka

Texas in Flames), and Douglas Holloway, associate producer of

The Whole Shootin’ Match, who made the stoner-comedy

Fast Money (1980) with Pennell as his cinematographer. Direct links to Linklater also duly appear with Wayne Bell, composer on

Last Night at the Alamo and sound recordist on

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Whole Shootin’ Match and

Fast Money, who worked as sound editor on

Before Sunrise, SubUrbia, Waking Life, Before Sunset and

A Scanner Darkly. The collaborative nature of regional filmmaking clearly depends upon this versatility of local enthusiasts and is a tradition that the cinema of Linklater maintains. On the list of collaborators with whom he has frequently worked are found numerous actors (especially Austinite Ethan Hawke) as well as Kim Krizan (actress in

Slacker, Dazed and Confused and

Waking Life and co-writer of

Before Sunrise) and Tommy Pallotta who played Looking for Missing Friend in

Slacker and produced

Waking Life and

A Scanner Darkly. In addition, there are long-time collaborators cinematographer Lee Daniel and editor Sandra Adair, as well as Anne Walker McBay, who cast

Slacker and went on to produce most of Linklater’s films, as well as

Infamous (Douglas McGrath, 2006) and the

Before-like In Search of a Midnight Kiss (Alex Holdridge, 2007). They are joined by John Frick, who was production designer on

Dazed and Confused and art director of

The Newton Boys and the television series

Friday Night Lights (2006–) that is filmed in Austin. Dig a little deeper and one finds Texan Catherine Hardwicke, writer-director of

Thirteen (2003) and director of

Twilight (2008), working as production designer and second unit director on

SubUrbia and production designer on

The Newton Boys. In addition, Linklater often returns favours to fellow Austinite filmmakers with fun cameos such as the tour bus driver in Mike Judge’s

Beavis and Butthead Do America (1996), Cool Spy in Robert Rodríguez’s

Spy Kids (2001), Crony 2 in Ethan Hawke’s

Chelsea Walls (2001) and the self-deprecating John Wayne Enthusiast in Hawke’s adaptation of his own novel,

The Hottest State (2006). In this and in a far greater sense, Linklater’s endeavours have been crucial to the emergence of a film-literate community in Austin and the establishment of a robust industry.

Perhaps surprisingly, Linklater was not born in Austin but in Houston on 30 July 1960. The son of an insurance agent and a speech pathologist, his parents divorced when he was seven years old and he moved with his mother to Huntsville, Texas, seven miles south-east of Houston, where he would spend weekends with his father. He studied English and played baseball at the Sam Houston State University, but admits, ‘I was just drifting [.] I was just taking classes that interested me. At some point I realised I was probably never going to graduate’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 5). In his sophomore year in 1982 he took acting classes, wrote several one-act plays and read French and Russian literature on film. Dropping out at the end of that year, he took a job as an oil rigger in the Gulf of Mexico, which enabled him to save $18,000 and read all he could about film. He spent much of his shore leave at repertory cinemas in Houston and spent his savings on a Super-8 camera and editing equipment before moving to Austin in 1984:

It was a very specific decision based on, ‘Where can I live cheap, watch a lot of movies and be around cool people?’ I’d had my eyes on Austin since high school. There were lots of cute girls around and Austin’s always had this tolerant, hippy vibe. What made it tolerant for me, unlike Dallas, Houston and some of the bigger cities, was the fact that I knew all my friends were artists, painters, writers, musicians. No one asked you, ‘What do you do for money?’ The rest of the world is, ‘Are you in school? Are you going to get your Masters? Your MBA?’ It was all about your economic interests, but here it was just about your artistic desires. And that’s the world I chose, a more nurturing environment, where no one judged you if you didn’t have a job.

10

Thereafter, Linklater’s adopted slacker lifestyle led to the making of short films (or ‘film attempts’ as he calls them): ‘I took the pressure off by admitting that it wasn’t going to be meaningful in any way other than as a technical exercise’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 9). The supportive environment of Austin had already fostered a regional group of Super-8 enthusiasts led by Austin Jernigan and Ray Farmer, calling themselves the Heart of Texas Filmmakers, who gathered at Esther’s Pool on Sixth Street. Vaguely in the style of groups such as Maya Deren’s Creative Film Foundation (est. 1955) and Jonas Mekas’s Filmmakers’ Cooperative (est. 1962), the Heart of Texas Filmmakers revived the Ritz as a cinema but their group was all but extinct as a creative entity when Linklater met Lee Daniel at its last meeting (Daniel 2000). Desperate to see films when the campus cinema stopped providing, they began an experimental film series at the off-campus Dobie cinema in the autumn of 1985 with crucial support from the cinema manager and Louis Black, editor of

The Austin Chronicle, who granted free advertising space to their endeavour. Linklater and Daniel called themselves the Austin Film Society (AFS) and went on to run screenings at nightclubs, galleries, local community colleges and concerts by the band Texas Instruments. In a laid-back music town, Linklater and Daniel were the film guys.

Meanwhile, Linklater put together his ‘film attempts’ at his flat-turned-editing room in the West Campus area of the city. His seven-minute Woodshock (1985) was an impressionistic record of a music festival staged in Austin’s Waterloo Park, during which fourteen bands had played to an audience of skinheads, goths, proto-grunge adolescents and fearless frats whose kegs, bongs and joints were shared quite freely. Shot on Super-8 and with a Nagra tape recorder, Woodshock looks and sounds rough, but there is a wry intelligence at work in its delusional aspiration of referencing the Woodstock festival, which means it plays like a pocket-sized satire of Michael Wadleigh’s documentary Woodstock (1970). Imitating that film’s pastoral psychedelia, Linklater lets the sun flare directly into the lens, adds a distortionately loud soundtrack of birdsong, and employs woozy dissolves between revellers and waterfalls. There is much toking, chugging and mugging to camera as Linklater captures quick sketches of an event that will be recreated in the Moon Tower party scene of the 1986-set Dazed and Confused. Austinite Daniel Johnston, the songwriter and musician whose music and bipolarity was the subject of the documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston (Jeff Feuerzeig, 2006) also makes an appearance handing out tapes of his music as was his habit. Stepping into Linklater’s view he exhorts the filmmaker to ask him a question. ‘Where do you work?’ is Linklater’s inapposite gambit. ‘I work at McDonalds,’ Johnston grins holding up a cassette tape: ‘And this is my new album “Hi, How Are You?”.’ Far from self-promotion, his gesture is symbolic of a mid-1980s Austin where songwriters would hand out tapes, bands would gig in public parks and filmmakers would stage public screenings. Only the passerby caught in the film’s open ending expects some greater purpose from Linklater’s filming: ‘All right, what are you gonna use this for?’

For? In the spring of 1987 Linklater and Daniel were giving little thought to anything grander than how to cover the costs of renting and watching films: ‘If there was a director I liked and wanted to see more films by, we’d do a retrospective’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 12). They renovated a room above Captain Quackenbush’s Intergalactic Café on Guadalupe Street and installed a screening facility that provided a venue for film shows, debates and filmmakers to cultivate ‘that idler dropout mentality’ (Lowenstein 2009: 14). Quackenbush’s (which no longer exists but would serve as location for the Pixel vision sequence in

Slacker) was also the hub of the Austin Media Arts organisation established by Denise Montgomery, who would appear in

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books and play Having a Breakthrough Day in

Slacker. Her additional work as sound recordist on

Slacker and as assistant art director on

Dazed and Confused provides yet another example of the non-competitive, collective, creative energy of the poets, playwrights, novelists, performance artists, musicians, songwriters and filmmakers who came together in Austin. Linklater was a garage-filmmaker whose

Woodshock, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books and

Slacker were so pro-Austin that they were only coincidentally anti-Hollywood.

The AFS showed its commitment to amateurism by screening the films of Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Jon Jost and James Benning in influential sessions dedicated to the avant-garde that looked to Europe but also proclaimed and celebrated the existence of such a thing in America. There was also Psychedelic Cinema, hailed on the home-made flyers as ‘a mind-bending retinal circus!’ to patrons who needed little encouragement to go interactive. The Russian Avant-Garde, Beat Cinema (‘Two Bucks!’) and Gay and Lesbian Experimental Film all performed well, as did late shows of cult favourites such as

Carmen Jones (Otto Preminger, 1954),

Porcile (

Pigpen, Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1969),

Caged Heat (Jonathan Demme, 1974) and

Ai no korîda (

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima, 1976). The two dollar entry fee was sufficient to fund a double-bill of films by Luis Buñuel entitled The Subversive in the Studio and pair Vincente Minnelli’s

Two Weeks in Another Town (1962) with

The Clock (1945), an obvious influence on

Before Sunrise in which Corporal Joe Allen (Robert Walker) meets Alice (Judy Garland) while on leave in New York and they spend the day together, walking and talking, seeing the sights and falling in love. As the AFS developed there were also triple bills of films by Dreyer, Godard, Sam Fuller and Robert Aldrich, septuple bills by Bresson, octuple bills by Yasujiro Ozu, and a decuple bill by Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The society tried to scandalise with a screening of Pasolini’s

Saló o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (

Saló or the 120 Days of Sodom, 1975) and even manufactured flyers on the occasion of its return that heralded, ‘a call to all Republicans and Christians and members of the White Race and PTA affiliates and Citizens Against Pornography to unite against these forces. Infidels and blasphemes are plotting the return of

Saló,’ followed by the venue, time and price of admission.

11Although playful, such provocation does allude to the divisive legacy of Watergate (1972–74), the Vietnam War (1950–73), and the period of isolationist Republicanism led by the two tenures of President Reagan (1980–88) as well as the corporate-minded foreign policy of President George Bush Senior (1988–92). However, as an Oblique Strategy card in

Slacker states: ‘Withdrawal in disgust is not the same thing as apathy.’

12 Instead, those who participated in this collective withdrawal in Austin claimed reflection, imagination and creativity as the aims of a plethora of non-profit endeavours that facilitated and signified an internal exile from Reaganomics, the rather less oblique strategy of a government intent on economic deregulation, the reduction of government spending, isolationist economic policies and a concurrent interventionism in countries not far south of Austin in Central America. Their communal disgust with the political system found special inspiration in the city’s links to the Civil Rights legislation of the late 1960s that had been passed by Austinite President Lyndon Johnson. In contrast, the consequent decline in white Southern American support for the Democrat Party had also contributed to the political ambitions of the West Texas-based Bush family, whose George Junior, says Linklater, ‘wasn’t the artistic slacker but the money-grubbing slacker, the hedonistic kind, into beer and coke, and then this desperate “Born Again”. […] Where he’s from is not Austin, it’s an oil-rich town with a Rolls Royce dealership’ (in Peary 2004). The isolationism of the slacker community (even within Austin) is easily romanticised but the collective alienation that was a microcosm of the isolation fostered by Reaganomics nurtured an identity that was defiantly liberal in its expression.

The slacker boom in mid-1980s Austin and Linklater’s role in it may be usefully compared to that of the contemporary cultural movement known as

La Movida in Madrid from which the filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar emerged. Spain was barely ten years on from a Fascist dictatorship when

La Movida offered a platform for previously forbidden lifestyles, sexualities and cathartic artistic expression. This made of Madrid a melting pot that Almodóvar captured and communicated in his own extravagant ‘film attempts’ such as

Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón (

Pepi, Luci, Bom and Other Girls Like Mom, 1980) and

Laberinto de pasiones (

Labyrinth of Passion, 1982) that embodied the reckless and imaginative spirit of a collective that had much in common with slackers. Almodóvar’s films were never explicitly political but they were so rooted in a specific time and place that their own temporalised regionalism created an enduring aesthetic and association of the city with the writer-director. Almodóvar’s Madrid invoked the sometimes desperate wish of its nocturnal inhabitants to make up for lost time by having a good one. His films insisted on gaudy fashions and gender-bent affectations as the strident performance of Postmodern identity in a country that had just escaped totalitarianism. Linklater’s Austin, meanwhile, was a flat canvas of wide avenues for slackers whose possession of its sidewalks was cat-like in a pose of indifference best captured in the walking and talking of

Slacker: ‘Who’s ever written a great work about the immense effort required in order not to create?’ What Madrid and Austin shared was a sense of potential found in the inconsistencies of life beyond a work routine or a familiar family structure, one that contrasted with the uncertainty towards change of the country and state that they respectively capitalised. In contrast, the New German Cinema that lasted until the mid-1980s had been a structured reaction against creative stagnation that had ambitious objectives for an industrially viable, internationally profitable cinema of artistic excellence that sought funding and synergies with television companies instead. The films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Wim Wenders were also markedly divergent from the identification with a place that defines Linklater and Almodóvar because they expressed a contrary estrangement from post-war Germany. Their protagonists were rootless rather than communitarian. Yet, although their influence on American cinema is clearest in those who are at odds with their surroundings in the films of Jim Jarmusch (whose collaborations with Wenders’ long-time cinematographer Robby Müller effectively transposed the bleak aesthetics of displacement and dislocation to contemporary America), theirs was also the approach that Linklater tried in

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, his first full length ‘film attempt’ in which the filmmaker becomes a nomadic subject before returning to the adopted homeland of Austin.

Although It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books is a film by a college drop-out and self-taught filmmaker, its aphoristic title does not exclusively favour experience over education, but it does suggest the two should be combined. Shot on a Super-8 camera with a ten-second timer, it was, says Linklater, ‘sort of designed around its limitations’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 16) and thus has an unmixed, omnidirectional soundtrack that communicates the mindset of travel from all sides and initiates the hypothesis of a Cubist aesthetic in Linklater’s films. This minimalist film consists mostly of long and medium shots lasting several minutes of Linklater (who would set the camera’s timer before entering the frame) as he travels by Amtrak from Austin to Montana, San Francisco and Houston and back by car to Austin. ‘What I had in mind was these long, elegant camera moves [;] this I saw as flowing,’ he recalls (ibid.). There are no jump cuts here as the film is less concerned with departures and arrivals than it is with the in-between times and spaces and the minutiae of being alone but not lonely. Linklater snacks, naps and interacts with a variety of coin-operated machines. He reads, shoots hoops, tunes radios and televisions and meets up with old friends and girlfriends, family and like-minded travellers who help each other at the no-money level. But any dramatic interaction with these people is so frustratingly distant that it negates intimacy and suggests flawed human communication. The assemblage of long takes and long shots suggests an endless series of CCTV cameras has tracked Linklater on his travels. Yet the film’s objectivity is dismissed by the knowledge that Linklater must have topped and tailed the shots to create this eighty-five minute feature. Somewhere there is a reel of offcuts showing Linklater repeatedly racing back to the camera at the end of every shot to save film, time and money.

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books prefigures

Waking Life in its individualised search for transcendence promised by the experience of travel, which Linklater aspires to convert into a metaphysical journey that will cure some existential malaise. However, its assemblage resembles a collage of memory fragments of an uneventful journey rather than an incident-filled voyage of discovery. The sequence in San Francisco suggests a revision of that in Chris Marker’s

Sans soleil (

Sunless, 1983), a visual essay composed of a collage by association of film and memory in which Marker (who unlike Linklater remains behind the camera) retraces the wanderings of John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson (James Stewart) in the Bay Area in

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958). Certain narrative Macguffins do betray the collage, however, such as the shot in which Linklater fires a rifle out of his apartment window and, much later, the brief insert of a man crawling painfully across a parking space that not only connects with the earlier shot but alludes to Charles Whitman, a student at the University of Texas at Austin, who shot ten people from the University’s administration building on 1 August 1966, an event remembered with local pride by Old Anarchist (Louis Mackey) in

Slacker. Although

Elephant (Gus Van Sant, 2003) would employ a similar aesthetic in its recreation of the Columbine High School massacre, Linklater’s own brief embodiment of the assassin figure suggests a disturbing potential for violence within the spirit of rebellion associated with slacking.

For all the film’s impassive objectification of Linklater’s own athletic figure, the on-camera filmmaker remains a cipher for the manifesto of experience. This is not an autobiographical work in which Linklater considers, moulds, fixes and presents himself as knowable, but an auto-ethnographical work instead, somewhat in the manner of Chantal Ackerman and the Modernist Structural Realist cinema of the 1970s, in which the self is presented as a performance that is objectified and acknowledged as such. The staging of subjectivity is not even attempted by Linklater, who, as protagonist and filmmaker, cannot be in two places at once, so leaves the actual filming to the apparatus. Thus Linklater confronts the voyeurism of his own self by making it merely the content of a film whose subject is determined by the financial and logistic limitations of the project: one person, one camera. The film therefore meditates upon the indigent materiality of its own production and opposes what is culturally deemed to be private and mundane in order to imitate with railway carriages the interior journey of a filmmaker who never really leaves Texas. The fact that this is an internal journey as much as a geographical trip is underlined in the sequence where Linklater hikes to the top of a mountain in Montana and deliberately fails to shoot and show the view. Correlatively, the long takes do not promise or comply with the predestination of those of Bresson but allow for an unpredictable interior journey of a filmmaker whose experience of America does not tally with the one advertised in the brochure for Reaganomics. Its trajectory of simple redirections may be hardly more considered than that of a pinball interacting with a flipper, but the film does accrue and exude a poetic sense of realism in being of its own time and movement.

Despite shots of railway tracks converging on an infinite number of allusions to westerns,

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books is more sympathetic to the hobos who hopped freight trains during America’s Great Depression. Like them, Linklater’s onscreen character is seemingly in exile from his own country, alienated from its social pressures and estranged from its political system. Instead, identity is found in optimistic nomadism by way of meetings with like-minded folks such as the girl he meets and leaves sleeping in the train station (a prototype of

Before Sunrise’s Céline). His forebears are literary, for Jack Kerouac, Jack London, Eugene O’Neill and John Steinbeck are all Linklater’s illustrious ancestors, and their influence on his cinema is seen not only here but in the hobo played by David Martínez in

Waking Life, who jumps from a train to explain how ‘things have been tough lately for dreamers’. This voyage through the backyards and bars, parking lots, waiting rooms and railway sidings of America is one of anonymous places that correspond to Gilles Deleuze’s consideration of the concept of

l’espace quelconque (any space whatsoever) that he attributes without reference to Pascal Augé (Deleuze 2005a: 112). The ‘any space whatsoever’ is a mundane place of transit, where the depersonalisation and isolation of individuals occurs, but also one that is surrounded by an out-of-field indeterminacy that holds the potential for unique and singular experiences. Deleuze writes: ‘It is a space of virtual conjunction, grasped as pure locus of the possible’ (2005a: 113). Linklater (in line with Deleuze) thus situates himself in the cinematic cloze test of filmmakers such as Michelangelo Antonioni and Monte Hellman, who each used such settings to place the identities of their protagonists in flux and/or crisis in their existential road movies,

Zabriskie Point (1970) and

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) respectively. Yet the virtue of any space whatsoever is that the traveller can potentially choose to go in any direction whichever. For Deleuze, this choice ‘is identical to the power of the spirit, to the perpetually renewed spiritual decision’ (2005a: 120). Thus, in the early cinema of Linklater we can begin to identify techniques associated with representations of alienation in post-war European cinema and their application to a regional concept of American cinema that is also informed by the existentialist and Marxist undercurrents of slacking. Because films such as

Woodshock, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books and

Slacker associate slacker culture with a wider alienation brought on by ‘withdrawing in disgust’ from political and national institutions, Linklater’s filmed round trip effectively points to the reterritorialisation of a part of America called Austin.

Furthermore, in personally embodying this concept of reterritorialisation by reflective exploration in It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, Linklater also appears to be imitating the Situationist International ploy of the psycho-geographical dérive (drift) in his attempt to leave Austin and investigate what truth lies behind the pre-packaged concept of Reaganite America. His quest connects with the definition of psycho-geography made by French Marxist theorist, filmmaker and founder of the Situationist International Guy Debord, which combined subjective and objective knowledge of the self and one’s surroundings. Although predominantly urban and potentially anarchist in its strategy, Debord’s ‘Theory of the Dérive’ (first published in 1956) was a guide and incitement to losing oneself gainfully in spaces thought to be under the control of a system:

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. (2006: 50)

This strategy has clear parallels with

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, which embodies the paradox of losing oneself in order to gain knowledge of one’s potential, for ‘the

dérive includes both this letting-go and its necessary contradiction: the domination of psycho-geographical variations by the knowledge and calculation of their possibilities’ (Debord 2006: 50). The

dérive is a training course, an initiation rite and an exercise in reconnaissance that prescribes wandering as an adjunct to revolutionary theory or, to put it another way, insists that it is impossible to learn to plow by merely reading books. Despite Debord’s advice that ‘the interventions of chance are poorer’ (ibid.) on predestined train journeys and wandering in open country,

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books still exudes a spontaneity that ‘is the freedom to travel aimlessly, to simply exist in the world without daily responsibilities, [which is what] Linklater’s characters treasure most [and]

Plow is his most direct embrace of this freedom’ (Schwartz 2004). The

dérive proposes the inhabiting of spaces that are revealed as junctions of potential narratives and thus inevitable crossroads in a labyrinth of paths less travelled. This is the structural conceit that also underpins

Slacker, SubUrbia, Before Sunrise, Waking Life (in which Debord actually appears as Mr Debord, played by Hymie Samuelson),

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor and

Before Sunset in which space and time are wrested from stagnant notions, irrelevant hierarchies and redundant systems and reclaimed for imaginative, restorative and romantic endeavour. The America that Linklater wanders resembles that of

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984) and

Stranger than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984), but the onscreen Linklater is already Jesse Wallace (Ethan Hawke) before meeting Céline (Julie Delpy) in

Before Sunrise, staying still with his head against the window while watching the landscape move as if his train is a static, long, thin cinema with widescreen windows akin to the fairground ride in Max Ophüls’ Vienna-set

Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948). Ultimately, however, this is a return journey to Austin, where Linklater was reunited with the ten hours of exposed Super-8 film that he had mailed home in stages.

The playful-constructive dérive complete, Linklater proceeded to reassemble the objective terrain of his film in accordance with both the logical sequence of its occurrence and his understanding of the social awareness that he had at least pretended to experience. Following Emile Durkheim:

[This] does not consist in a simple science of observation which describes these things without accounting for them. It can and must be explanatory. It must investigate the conditions which cause variations in the political territory of different peoples, the nature and aspect of their borders, and the unequal density of the population. (2003: 78)

Seeking to reconstruct this experience, Linklater transferred the film to video and edited at Austin’s ACTV studios two nights a week for a year. Knowledge gained and explained was certainly limited by the solitude of the whole venture, however, and it is apt to see It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books as a prequel to Slacker, whose preparation would now occupy Linklater. As Debord had indicated:

One can dérive alone, but all indications are that the most fruitful numerical arrangement consists of several small groups of two or three people who have reached the same level of awareness, since cross-checking these different groups’ impressions makes it possible to arrive at more objective conclusions. (2006: 50)

This notion of a cinematic game of tag between the various participants of various

dérives was ideal for representing the drifting nature of fellow Austinite slackers. Even Debord’s warning that ‘it is impossible for there to be more than ten or twelve people without the

dérive fragmenting into several simultaneous

dérives’ (ibid.) became a template for the cinematic drift in the more appropriately urban space of Austin, which thereby represented an alternative state of mind to that of the government and electoral majority of the country that enclosed it. As Debord warned: ‘The practice of such subdivision is in fact of great interest, but the difficulties it entails have so far prevented it from being organized on a sufficient scale’ (ibid.). This was the challenge met by

Slacker.

Linklater filmed Slacker as ‘sort of a group art project’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 26) in the sweltering heat of July and August 1989, when the greatest obstruction to its production was the subscription to its ethos of its participants, many of whom could not be bothered to show up for Anne Walker McBay’s casting session. Linklater’s ambition was for a non-judgemental film made of all the unheralded individual activities, neighbourhood anecdotes, spontaneous street theatre and community art projects that made up the tolerant community of Austinites of which he was part. However, his vision was actually quite narrow, empirical and contained within a few blocks around Guadalupe Street. As he admits: ‘Slacker’s unique, because it’s not just Austin, it’s West Campus, so it’s kind of the university. So it made it a little less diverse-looking than Austin really is.’ He also claims to have imagined the film as a single shot: if It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books was about disconnection, this was quite the opposite. Practicalities of filmmaking spoiled the single shot idea, but the ambition remained:

The biggest visual idea was probably that I wanted very little editing, long takes, and the same lens. With the people changing constantly, I wanted it to seem real, like an unending flow. […] I had this kind of flowing, real thing going on in my head. (in Lowenstein 2009: 27)

Through local interest in

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, the dissemination of a rough outline of sequences known as The Roadmap and a letter of support from Monte Hellman, who had liked

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books,

13 Linklater scored a grant of $2,000 from the Southwest Alternate Media Project, a Houston-based organisation that fostered independent productions. This he added to all that had been saved and would be borrowed, including the same amount of money from his mother as she had spent on his sister’s wedding, gained on the promise that he would never get married (Pierson 1996: 191). The total notional budget of $77,340 was slashed by borrowing equipment worth $11,700 and deferring wages totalling $40,550 for cast and crew so that everyone worked for free. With $10,820 for post-production (including three release prints for $2,500), the final cost would be around $23,000, which still allowed for the use of a crane and a Steadicam as well as a sound mix that added non-diegetic effects such as the typewriter ‘splashing’ into a dry river-bed and an ‘offscreen’ car crash. As Linklater recalls:

I was going for a certain naturalism. It wasn’t planned. I really wanted to be like Robert Bresson with a really highly structural, highly mannered style. That’s how I thought about cinema. But when I started doing it it was something else entirely. I wanted it to have that eloquent documentary feel, but if you really look at it, there’s cranes, Steadicam, a lot of dolly shots; it’s very technically ambitious for a no-budget film.

Nevertheless, money-saving short-cuts that opposed bought-in solutions with creative, personal ingenuity were plenty, including the recreation by two obliging friends of a sex scene from Ai no korîda that is glimpsed on the monitor of Video Backpacker (Kalman Spelletich). But some limitations were frustrating, with neither the Super-8 nor the 16mm lens wide enough to shoot any group conversation, thereby dooming Linklater to alternate set-ups and the obligation to cut into scenes. Uncertain how to end a film that should by nature be interminable, Linklater thought of concluding ironically with Peggy Lee’s ‘Is That All There Is?’ but its expense prompted the substitution of ‘Strangers Die Everyday’ by the Butthole Surfers, whose drummer Teresa Taylor plays Madonna Pap Smear Pusher, a prescient conflation of pornography with celebrity culture.

In addition to the ideological factors that inspired the gambit of filmmaking, the possibility of actually making a film on such a small budget was due to the technological advances of the 1980s that enabled filmmakers to focus on the details of the everyday. In addition, this attention paid to the everyday meant that ideas of what was local and regional (to Austin, for example) were important at a time when America’s foreign policy and globalisation were both driven by the alienating forces of capitalism. The regional cinema of Pennell, Linklater and others may also be understood in terms of what Hamid Naficy calls ‘the interstitial mode of production’ (2001: 40) of accented filmmakers for whom the idea of local, regional and home is especially important.

Slacker’s collage of video, 16mm, Super-8 and Pixel vision (shot on a Fisher Price toy camera bought for $99 from Toys R Us) made collaborative multi-tasking the film’s form, content and meaning with Linklater leading the way as the first character on screen. Should Have Stayed at Bus Station (Linklater) arrives in Austin, catches a cab and regales the driver with a stream-of-consciousness monologue that turns the tables on most cab rides.

Slacker thus begins like a direct and immediate sequel to

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books that offers the fresh contrast of community in a single place with the lack of same previously experienced around the country. Struck by an evolving notion of parallel and alternate realities inspired by

The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) and inspired by the possibilities revealed in daydreams, Linklater elucidates upon a variety of other yellow brick roads his life could have taken or may be taking – ‘This one time I had lunch with Tolstoy, another time I was a roadie for Frank Zappa’ – before regretting his own lack of faith in oneiric potential by not having stayed at the bus station. Although the film’s specific and limited time-frame conforms to Linklater’s view that ‘time is a valuable, unreplenishable commodity steadily slipping away,’ (Linklater 2004),

Slacker insists that ‘daydreaming is the place where all the new situations, narratives and acts originate’ (ibid.). Dropped off to meander in Austin, it appears that Linklater might repeat the adventure of

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, but the camera, which is now subjective, loses interest in him when it comes across a hit-and-run victim and the imminent arrest of the victim’s son. And when the cops have gone the camera picks on a bystander and follows him to another passerby until encountering another re-acquaintance, and so on, thereby illustrating the parallel realities lived by characters in Austin whose common link is idleness followed by various degrees of happiness, sadness and madness.

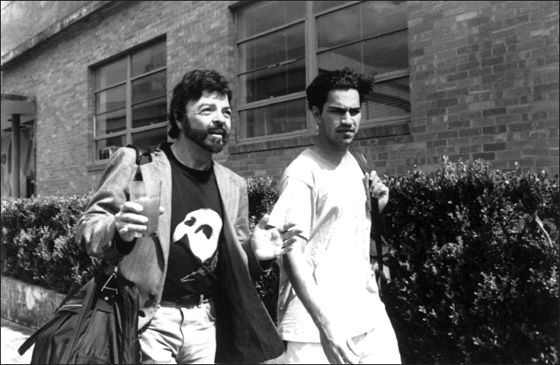

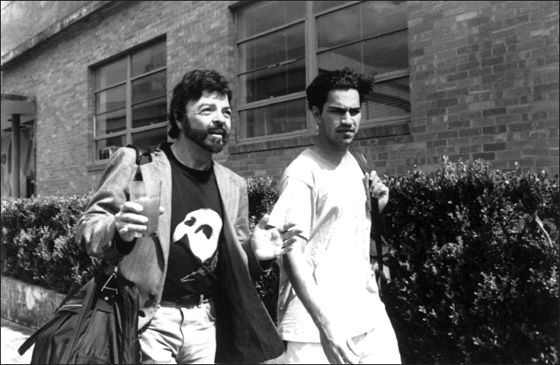

Walking and talking in Slacker

The protagonist of this dérive is not Linklater or any other character but the camera itself, which drifts from one person to the next, lending its subjectivity to the spectator who is thereby empowered to daydream around Austin. As a satire of digressive pilgrimage, Slacker may be appreciated as Linklater’s palimpsest of Luis Buñuel’s La Voie lactée (The Milky Way, 1969), although Linklater’s most direct reference to the Surrealist agitator is in the oft-quoted refrain of Hitchhiker Awaiting ‘True Call’ (Charles Gunning) – ‘I may live badly, but at least I don’t have to work to do it! – that originates with Don Lope (Fernando Rey) in Buñuel’s Tristana (1970):

I say to hell with the work you have to do to earn a living! That kind of work does us no honour; all it does is fill up the bellies of the pigs who exploit us. But the work you do because you like to do it, because you’ve heard the call, you’ve got a vocation – that’s ennobling! We should all be able to work like that. Look at me, Saturno – I don’t work. And I don’t care if they hang me, I won’t work! Yet I’m alive! I may live badly, but at least I don’t have to work to do it!

The effect of this idle pilgrimage or

dérive can change with successive viewings, with tedium, envy, beguilement, depression and exhilaration all possible cognitive affective responses to

Slacker by new and repeating spectators. This apparent affective incoherence is explained by Old Man Recording Thoughts (Joseph Jones), who appears late in the film to proclaim ‘the more the pain grows, the more this instinct for life somehow asserts itself. The necessary beauty in life is in giving yourself to it completely. Only later will it clarify itself and become coherent.’ Thus diagnosed, this movement from person to person through the day and night in Austin is revealed as an urban

dérive that Linklater has himself defined as ‘a nomad education of movement that features a changing curriculum of [one’s] own making, based on the passion and pursuit of the moment’ (Linklater 2004). This

dérive is the reterritorialisation of a time and place that effectively occupies the capital city of Texas, home-state of the recently elected President George Bush senior while he is away working in Washington. It therefore positions

Slacker as a guerrilla film of sly tactics and great political resonance.

Slacker is the film of a region whose inhabitants are in a kind of hibernation throughout three successive Republican presidencies. Moreover, its sense of lucid dreaming is conveyed in long takes that correspond to Deleuze’s concept of time-images, whose form, content, subversive meaning and political resonance was a determining factor in the cinema that emerged in Europe after World War II (Deleuze 2005a; 2005b). The time-image, which evades objective criteria, is usually a long take that stalls the narrative, dislocating the protagonists and the audience in time, whose passing is made perceptible. Consequently, existential angst and a longing for metaphysical transcendence become the locus of an image whose meaning is heightened by, and inseparable from, its prolongation. A time-image makes time visible in the way protagonists and audience are subject to the sense of its duration; but it also embodies time’s dimension as indefinable, thereby compounding limitations of language and making verbal description impossible. Instead, it forces the audience to scrabble for meaning by ‘thinking’ in terms of the image. Linklater relocates the time-image’s technique and aesthetic of dislocation and alienation from post-war Europe to Austin in the early 1990s and uses it to explore the mindset of an isolated, regional community whose liberal, left-wing, existentialist philosophy and lifestyle is at odds with the electorate and its thrice-elected Republican government. The inhabitants/protagonists of

Slacker have gotten along by rejecting society and its social hierarchy before it rejected them. They now inhabit and maintain a communal identity that is celebrated in a passed-along polyphony resembling Bakhtin’s carnival of street-level interaction, in which all characters are unfinalised and truth is found in a multitude of carrying voices. For Bakhtin, then, ‘in the whole of the world and of the people there is no room for fear. For fear can only enter a part that has been separated from the whole’ (1984a: 256). Just as the voices and gestures of this slacker folk culture express an alternative to what Linklater calls ‘democratic ineptitude’ (Linklater 2004), so their freedom to think is gained, explored, observed and shared in the time-images that make up the carnival of their everyday

dérive.

The most famous literary

dérive (even before it was identified as such) is that of Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s

Ulysses, first published in its entirety in 1922, which chronicles his drift through Dublin on the most ordinary day possible, 16 June 1904. The novel is divided into eighteen overlapping episodes that play with form and resemble Linklater’s parallel and alternate realities. Description, monologue, lists, punctuation-free stream of consciousness, Q&A and a play take their turn like the passers-by in

Slacker, making of

Ulysses an experimental prose full of such rich characterisations, absurdist allusions and details of Dublin that it is one of the most highly regarded of all Modernist novels. Joyce signals that Bloom’s

dérive is based upon a similar subscription to the creativity of daydreaming: ‘His eyelids sank quietly often as he walked in happy warmth’ (1993: 55). Bloom, like Linklater’s camera, is guided by an unpredictable instinct: ‘Grafton Street gay with housed awnings lured his senses’ (1993: 160). For Joyce, as for Linklater, this wandering in the streets entails an immersion in an otherwise unknowable culture: ‘He walked along the curbstone. Stream of life’ (1993: 148). Like

Slacker, Ulysses may appear chaotic but a sense of burgeoning revolution is expressed in such intense and prolonged descriptions (literary long takes) of the commonplace and the working class from all angles that the Cubist element of Modernism is also evoked in ‘the cracked looking glass of a servant being the symbol of Irish art’ (1993: 16). In Cubist style, Joyce’s text is ‘an epic “body” with episodes comprising somatically interrelated and interconnected arts, organs and hours’ (Johnson 1993: xxxii). Like

Ulysses, Slacker begins with a matricide that is soon shrugged off for fear that its melodramatic qualities will swamp the

dérive with plot. Joyce’s novel is also referenced explicitly in

Slacker when Jilted Boyfriend (Kevin Whitley) is advised to rid himself of an ex-girlfriend’s belongings in order to get over obsessing about her as a perfect, pure and unrepeatable romance. Guy Who Tosses Typewriter (Steven Anderson) recites a passage from

Ulysses that comments on the wrongheaded idealism of infatuated lovers while also making explicit the affined structural conceit of

Slacker’s catalogue of Austinites:

To reflect that each one who enters imagines himself to be the first to enter whereas he is always the last term of a preceding series even if the first term of a succeeding one, each imagining himself to be the first, last, only and alone whereas, he is neither first nor last nor only nor alone in a series originating in and repeated to infinity. (Joyce 1993: 683)

‘It all makes sense if you’d just read from this passage here.’ Filming Guy Who Tosses Typewriter (Steven Anderson) as he reads from James Joyce’s Ulysses in Slacker

Furthermore, this union of the dérive and Ulysses will also be felt in Before Sunrise, whose time-frame for wandering Vienna is pointedly Bloomsday (16 June) and in Before Sunset, where the dérive begins in the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris which first published Joyce’s novel in 1922.

Like slacking, the dérive is a means of empowerment, a therapeutic technique and a strategy of urban occupation. The drifter/slacker does not evade duties and responsibilities out of laziness but out of dedication to more spiritual aims. As Coupland states in Generation X: ‘We live small lives on the periphery; we are marginalized and there’s a great deal in which we choose not to participate’ (1996: 14). Yet, as Robert Louis Stevenson asserts in his 1876 essay An Apology for Idlers: ‘Idleness so called, which does not consist in doing nothing, but in doing a great deal not recognized in the dogmatic formularies of the ruling class, has as good a right to state its position as industry itself’ (2009: 1). Even so, self-indulgence, sloth and arrogance is exhibited by several of the characters in Slacker (as well as by Joyce’s Leopold Bloom), which also reflects Coupland’s warning that ‘we’re not built for free time as a species. We think we are but we aren’t’ (1996: 29). Nevertheless, Slacker is ultimately an optimistic film in which street-level interaction between humans is still mostly enjoyed in a world before mobile phones and social networking websites transformed interpersonal communication. The fact that Slacker ends with a montage that recalls A Hard Day’s Night (Richard Lester, 1964) constitutes a naive return to the optimism of the 1960s or at least a nostalgic recreation of same. It also signals a key theme in Linklater’s films, namely that when allowed the time to express themselves freely, most people find a spiritual quality within themselves that suggests a potential for transcendence.

Much like the way grungy garage bands liberated rock music from branding and power ballads,

Slacker demonstrated that the means of production that had once inspired the French New Wave were once more at hand for filmmakers like Linklater and Kevin Smith, who was so enticed by

Slacker’s iconic poster image of Madonna Pap Smear Pusher that he travelled the fifty miles from New Jersey to the Angelika multiplex in Manhattan on his twenty-first birthday in August 1991 to have his imagination ‘kick-started [by] a glimpse into the free-associative world of ideas instead of plot, people instead of characters, and Nowheresville, Texas instead of the usual California or New York settings most movies elected to feature’ (2008). This solipsistic Nowheresville was an instant metaphor of creative freedom for Smith, who would make

Clerks in 1994, although as he admits, ‘the fact that “Nowheresville” was really Austin speaks volumes on how culturally bereft I was at that time’ (ibid.).

Slacker’s dérive thus revealed an alternative and parallel present for America as it was lived in Austin with its collaborative community, tolerant mood and creative behaviour. Although Philip Kemp asserts, ‘there’s little sense of serious deprivation, nor any suggestion that these marginal characters are the victims of callous economic policy’ (2006: 130), the inhabitants of

Slacker claimed a history based upon distrust of their political leaders and the system that empowered them. And even if that history was almost exclusively white and straight in a city with a massive Hispanic population, black districts and a proud and highly visible gay community too, the culture of this collective was no less entitled to its cinematic expression in the new regional cinema of the so-called independents than that of San Francisco’s Chinese in

Chan is Missing (Wayne Wang, 1982), the Manhattan socialites of

Metropolitan (Whit Stillman, 1990) or the lesbian community of

Go Fish. Despite the colonising of America by firstly what Joyce called ‘the sweepings of every country’ (1993: 230) and later by big-name franchises and the uniforming of its citizens in logos,

Slacker/Austin was a complementary example of an extant pioneer spirit. At a time when ‘75 per cent of young males 18 to 24 years old [were] still living at home, the largest proportion since the Great Depression’ (Gross and Scott 1990),

Slacker was a metaphor for independence and a clear indication to would-be filmmakers like Smith that regional American cinema could even settle in places like New Jersey. Like Coupland’s novel

Generation X and Nirvana’s album

Nevermind, Linklater’s film indicated that expressions of independent thought could coalesce to form ‘a sad, evocative perfume built of many stray smells’ (Coupland 1996: 154). Most pointedly, although

Slacker, like

Nevermind and

Generation X, described a period maligned by what Coupland defined as ‘Historical Underdosing: To live in a period of time when nothing seems to happen’ (1996: 9), it demonstrated that even this was not a hindrance once the vibrant inner life of imagination and reflection was liberated from ‘low pay, low prestige, low benefits, low future’ (Coupland 1996: 5).

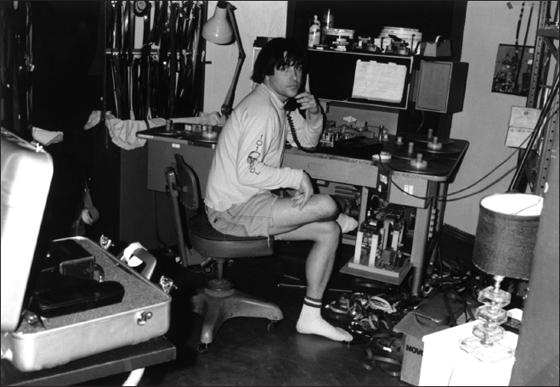

Richard Linklater editing Slacker