Although the German connection now threatened to change all that was known about the crystal skulls, the keeper of the Parisian skull had resolutely maintained that his skull was ‘definitely Aztec’. The British Museum skull was labelled ‘probably Aztec’ and Nick Nocerino was unyielding in his opinion that his skull was at least as old as the Aztecs. Until the tests, we would not know for sure. But we were still waiting for confirmation that they would take place. In the meantime, we wanted to find out more from any archaeological evidence left by the Aztecs and to explore the mysterious ruins of Teotihuacán. Despite Eugène Boban’s dubious reputation, we wondered whether his visit to this site might turn out to have some connection with the crystal skulls he had been selling.

The Aztec civilization arose in the early thirteenth century AD around what is now Mexico City, so we decided to go there first. Mexico City today is a huge sprawling urban metropolis housing nearly 20 million people. From the air it looks like a vast ocean of concrete stretching right across a high mountain plateau, surrounded on all sides by the peaks of various volcanoes. Most of these are now extinct, but some, such as Popacatapetl, still occasionally threaten to erupt. As we arrived on the ground, however, these volcanoes became invisible, due to the thick smog that now chokes this vast sprawling city. The pollution is said to be equivalent to smoking 40 cigarettes per day and is known to shorten life expectancy by several years.

As soon as we had recovered from our jet lag we set off through the choking streets for the National Museum of Anthropology. From the outside, the low earthquake-proof concrete building looked more like a nuclear bunker than the veritable treasure chest of ancient wonders that it turned out to be. We were very fortunate that our guide around the museum was a remarkable man by the name of Professor José Salomez Sanchez, a visiting professor of archaeology from the nearby National University. José, like countless other Mexican academics, was these days forced to supplement his meagre academic income through the more lucrative trade of being a tour guide, in order to properly feed and support the two of his four children who were still living at home.

As Ceri and I wandered through the corridors of the museum and gazed in wonder at the many ancient artefacts, José built up a vibrant and dramatic picture of the ancient Aztecs and their predecessors. It seemed the Aztecs had based an entire civilization on the cult and worship of death. They were renowned for ritual human sacrifice and were also absolutely obsessed with the image of the human skull. The museum was lined to the gunnels with varied and exotic artefacts, and many of the ancient objects depicted the image of the human skull.

At its height the Aztec empire spanned a vast area of Central America from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Atlantic in the east and from the deserts of the north to the jungles of the south. It had an estimated 10 million inhabitants, but was completely destroyed by the Spanish, who arrived in 1519.

The dramatic rise and fall of the Aztec empire is a story of drama, violence, tragedy and betrayal. It tells how a small group of vagrant peasants managed to transform themselves, in less than 200 years, into one of the largest and most powerful civilizations of all the Americas. It is also the story of how a 33-year-old man, with only 600 men and 16 horses, managed to conquer a magnificent empire that was far larger than his home country of Spain. The story of the Aztecs’ meteoric rise and fall is also a testament to the power of prophecy and prediction. And, as we were to discover, one or more crystal skulls may have been involved.

The Teotihuacános, the Aztecs’ predecessors in this part of central Mexico, are often considered the original founders of Aztec culture. Their civilization is thought to have arisen before the time of Christ and reached its zenith at around the same time as the Roman Empire in Europe. But all that remains of it today is the ruined city of Teotihuacán, which lies just to the north of present-day Mexico City.

The Teotihuacános were followed by the Toltecs, who were renowned as the founders of the city of Tula, a few remnants of which still lie not far from Mexico City (see Figure 1). They were also considered the originators of much of Aztec thought and belief. Tula was mythologized by the Aztecs as a magnificent and prosperous place where painters, sculptors and carvers of precious stones worked. According to later Aztec accounts, the Toltecs were ‘truly wise’ people. They worshipped many deities, but particularly the great god of all Central American civilizations, the ‘feathered serpent’ Quetzalcoatl. He was said to have taught religious practices that emphasized light and learning, and creating harmony and balance between humankind and nature.

The Aztecs believed that Quetzalcoatl had greatly helped their ancestors’ artistic and cultural development. He was said to have constructed spectacular palaces oriented towards the four directions and to have taught people about religion, agriculture and law. He also taught mathematics and the written language, music and song, arts and crafts, and, in particular, how to work with precious metals and stones. As the early Spanish chronicler de Sahagún wrote,

‘In his time, Quetzalcoatl discovered the great riches … the genuine turquoises, and gold and silver, coral and conches … [and] the precious stones.’1

It therefore remains a distinct possibility that this great leader taught the Aztecs’ ancestors how to create and work with precious stone objects such as the crystal skulls.

It has always been unclear whether the original Quetzalcoatl was purely a god or also a real human being. He was described as ‘pale of skin and bearded’ and it is thought that there was once a great high priest called Quetzalcoatl who ran a religious cult and governed a small empire from Tula. Whether god or human, the story goes that Quetzalcoatl, representing the forces of light, struggled against the forces of darkness in Tula. These were represented by gods such as Tezcatlipoca, or ‘Smoking Mirror’, and Huitzilopochtli, the patron god of the Aztecs, who was also the god of the sun and the god of war. Human sacrifice was apparently already being practised in Central America – the Toltecs are thought to have been almost as obsessed with death and ritual human sacrifice as the Aztecs – but it was not part of Quetzalcoatl’s teachings and it was on this issue that he is said to have fallen into dispute with many of those around him. He apparently finally lost the struggle against the forces of darkness, in particular Huitzilopochtli, and was forced to flee from Tula. Legends say that he ‘buried his treasure’ and ‘sailed off across the seas to the East’ on a raft of serpents. But he promised to return once again, according to some accounts only when the practice of human sacrifice had ceased, although others said it would be in the year One Reed of the ancient calendar.

Hearing the story of Quetzalcoatl and his battle against the dark forces of Huitzilopochtli, I wondered whether a crystal skull might well have been associated with this great and wise teacher who knew about gems, precious stones and carving. Could crystal skulls have been some of the objects of beauty that this mysterious teacher had taught the people to make? Or had crystal skulls been created to represent the darker forces of Huitzilopochtli?

Some time after Quetzalcoatl had fled, at around the beginning of the thirteenth century, a group of nomads started to appear in central Mexico. First referred to as ‘the people whose face nobody knew’,2 they later became known as the mighty Aztecs. As José Salomez Sanchez explained, their real origins are now lost in myth and legend. According to some accounts they came from the legendary Chicomoztoc, or ‘the place of the seven caves’, often thought to correspond to the high mountainous region they took so long to cross en route from their original ‘womb’. This common origin, often said to be shared by people who split into seven different tribes along the way, was a place called ‘Aztlan’. This was said to be a ‘country located beyond the sea, or ‘a magnificent town or city built on an island’ that had disappeared, somewhere to the east. Many accounts say the Aztecs originally arrived from the north, but it is believed that the people who originally came from Aztlan had been on a long migration, lasting over several centuries, wandering over the plains and mountains of Mexico in search of a land to make their new home. Some versions of the migration story also say that the Aztec people came across Michoacán, ‘the land of those who possess fish’, and thus perhaps the Atlantic Ocean, before they reached their final home.3

It is said that this migration was guided by the tribal prophets, who could somehow see into the future and had told the people that they would build a great city at the place where they saw an eagle clasping a snake in its claws. In the early thirteenth century the Aztecs arrived on the vast plateau, over 7,000 feet (2,240 metres) above sea level, which still forms the Valley of Mexico. This valley is now quite arid and dry, but then held two vast lakes and was a perfect place to support a large population. Indeed, it was already well populated when the Aztecs arrived and the original inhabitants were somewhat displeased at the arrival of these newcomers. Finding the Aztecs were searching for somewhere to settle, the locals directed them towards the very edge of the lake, an area infested with poisonous snakes, which they hoped would soon finish the migrants off.

But in 1325, on a tiny island just off the coast of the lake, the Aztecs apparently saw the sign they had been looking for – an eagle sitting on a cactus plant clasping a snake in its claws. So they settled down quite happily, began eating the snakes and apparently even thanked the locals for suggesting such a wonderful place stocked with one of their own favourite foodstuffs. They built a humble temple of reeds and sticks to pay tribute to their rain god Tlaloc, the god of water and fertility, set about draining the swamps and digging irrigation channels around the island and settled to successful agriculture, particularly growing maize.

But the Aztecs also became a powerful military force. They hired themselves out as mercenaries to all the other small tribes in the area, becoming their brute-force diplomats and advisers, and ultimately usurping each of them in turn. They fast gained a reputation as a shrewd and ruthless people, using a strange combination of friendly overtones followed by attack, without apparently showing any scruples at all. In one particularly horrifying example, José Salomez explained that the Aztecs are said to have invited a neighbouring king to present his daughter to them so that they could ‘honour’ her at a feast. The king sent his daughter ahead and was then invited to join the celebrations himself. When it was time for his daughter to appear at the banquet, the king was horrified to see an Aztec warrior dancing in, wearing her freshly flayed skin.

In this way the Aztecs quickly established a huge empire. As their fortunes improved, they built two great cities of gold and stone. The one on the lake was known as Tenochtitlan and is now Mexico City, and the other, Tlatelco, somewhat to the north, is now part of the great urban sprawl. Each city was built on an interlocking system of canals and waterways and served by aqueducts supplying fresh water from the nearby mountains. At the centre of each were vast temple and palace complexes housing the new kings, nobles and holy men and serving as sites for the ultimate tribute to the Aztecs’ many gods, who demanded regular human sacrifice. At the centre of Tenochtitlan the Aztecs built their mightiest temple, now known as the Templo Mayor (Main Temple).

Under a succession of emperors and shrewd warrior-kings, the Aztecs began to view themselves as a chosen people. They rewrote history, glorifying past victories and destroying all the historical documents of the people they had conquered, so that no evidence should remain to contradict the supremacy of Aztec rule. They were also responsible for the reform of local religion, giving new prominence to the fearful god of war and the sun, Huitzilopochtli, at the expense of Quetzalcoatl.

But the period of Aztec supremacy in Mexico was to last less than a century, for the foundations of the empire were soon to be shaken by the arrival of the Spanish at the start of the sixteenth century. This had apparently been foreseen by the Aztec holy men and some members of the nobility. One of their military leaders, Nezahualpilli, who also had a reputation as a sorcerer and magician, is said to have prophesied the arrival of the ‘sons of the sun’ (the term by which the Spanish became known) in the early 1500s and to have warned the emperor, Moctezuma II, of ‘strange and marvellous things which must come about during your reign’.4 Nezahualpilli is then rumoured to have escaped death by withdrawing to a secret cave before the Spaniards arrived.5

Moctezuma II had a reputation as a scrupulous observer of religious ritual and the esoteric omens of the priestly class, and is said to have become increasingly distressed by what he saw as a number of ill omens. Around 10 years before the Spanish arrived a dazzling comet suddenly appeared in the skies. De Sahagún reported its significance to the Aztecs:

‘…an evil omen first appeared in the heavens. It was like a tongue of fire, a flame [or] the light of dawn. It seemed to rain down in small droplets, as if it were piercing the sky.’6

Following this, the sanctuary of one of the Aztec goddesses mysteriously caught fire and the water on the lake formed gigantic waves, despite the fact that there was no wind.7

It is also said that a mysterious stone ‘began to speak’ and proclaimed the fall of Moctezuma’s empire. Little is known about this stone except that it was referred to as ‘the stone of sacrifice’ and was kept in a place called Azcapotzalco. According to the early accounts of the Spaniard Diego Durán:

‘The stone … again spoke, “Go and tell Moctezuma that there is no more time… Warn him that his power and his rule are ending, that he will soon see and experience for himself the end that awaits him for having wished to be greater than the god himself who determines things.” ’8

Moctezuma himself also had a magical mirror, made from obsidian, which he used for foreseeing future events. He is said to have looked in this mirror and seen ‘armed men borne on the backs of deer’9 – presumably a reference to the Spaniards’ horses, which were at that time unknown in the Americas.

Moctezuma called his holy men and soothsayers together to interpret his fate, saying:

‘You know the future … you know everything that happens in the universe … you have access to what is locked in the heart of the mountains and at the centre of the earth … you see what is under the water, in caves and the fissures of the soil, in holes and in the gushing of fountains … I beg you to hide nothing from me, and to speak to me openly.’10

But they refused to speak. Enraged, Moctezuma threw them in prison. But when he heard that his priests were not despairing in their cages but ‘were full of joy and happiness, and they continually laughed among themselves’ he went to see them again and this time offered them their freedom if they would speak.

‘They replied that, since he was so insistent on knowing his misfortune, they would tell him what they had learned from the stars in heaven and all the sciences in their power; that he was to be the victim of so astonishing a wonder that no man had ever known a similar fate.’ 11

Some accounts say Moctezuma was so displeased with what he heard that he then left his priests and seers to starve to death.

In April 1519 the first Spanish conqueror Hernando Corrés and his small army arrived at Veracruz on the Mexican coast. The local people saw their ships sailing along the Gulf coast and reported to Moctezuma that ‘a mountain has been seen moving around on the waters of the Gulf. It is also reported that the ruthless Cortés ordered all his own boats to be burned and scuttled in the ocean to prevent his army from being tempted to try and flee. For they were outnumbered by the natives by thousands to one.12

But Cortés was a wily politician and diplomat and he managed to persuade the local Tlaxcalans and several other tribes who were already displeased by their subjugation at the hands of the Aztecs to join forces with him against the mighty Aztec empire. Unbeknown to him, however, he already had destiny on his side.

It was the year One Reed when Moctezuma heard that strangers with ‘white hands and faces and long beards’ who were ‘riding on the backs of deer’ had arrived on the coast from the east and their leader was demanding a meeting with him. Little wonder that he mistook Hernando Cortés for the great god Quetzalcoatl returning, as prophesied, to reclaim the power that was rightfully his. It was a mistake that would prove fatal not only to Moctezuma himself but also to the Aztec empire.

At first Moctezuma wasn’t sure quite what to do. Should he receive Cortés as the god of all gods or treat him as a mortal enemy? But it was said that the worshippers of Huitzilopochtli would be unable to retain their power once Quetzalcoatl himself returned to reclaim it. So Moctezuma welcomed Cortés and his army. He placed a necklace of precious stones and flowers around his neck, offered him his crown of quetzal bird feathers, and indicated to him that he would humbly offer him back the rulership of the whole empire if he so desired. Cortés and his army were escorted into the very heart of Tenochtitlan, where crowds gathered to meet and cheer them, and offered the luxurious surroundings of the imperial palace itself as their home.

The Spanish could scarcely believe what they saw. The Aztec capital was far grander than the Rome and Constantinople with which they were familiar. With a population of around 300,000 it was about five times the size of London at that time. Many of the soldiers compared it to Venice or thought they had stumbled upon some enchanted city of legend such as Atlantis. As one of Cortes’ soldiers, Bernal Díaz, wrote in his diary:

‘We were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments they tell of in the legend of Amadís, on account of the great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream.’13

There were floating gardens and extensive orderly markets abundant with gold, silver, jade and foodstuffs of every kind. The royal palace even had its own private aviary and zoo, where jaguars, pumas and crocodiles were tended by trained veterinary staff. The city was of a beauty, order and cleanliness that the Spaniards had never seen before.

But, just as the soldiers were overwhelmed by the beauty and orderliness of the city, they were equally horrified by what they saw when they reached the Templo Mayor at the very heart of the magnificent metro-polis. Here they were to find the two main pyramid sanctuaries. One was dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of water and fertility, and the other to Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war. Over 100 steps led up to the top of the pyramids. These were apparently stained black, thick with the clotted blood of ritual human sacrifice. The very air itself hung heavy with the dank stench and putrefying odour of death.

The Aztecs invited the Spanish to attend the celebrations to mark the feast of Huitzilopochtli. As the ritual dances began and the Aztecs were totally engrossed in the festivities, the Spanish seized their moment to attack. They killed the most eminent members of the Aztec nobility and are said to have massacred at least 10,000 people on that night alone. Some of the Aztecs tried to stop them, driving them from the city, but they returned with more of their local allies and, having built 13 great barges, laid siege to the city. On 13 August 1521 Tenochtitlan finally fell. Moctezuma himself was taken prisoner and killed, thousands were murdered and the streets were awash with the fresh blood of the victims of the new Spanish rule.

In the years that were to follow many of those who were not killed by the invaders died instead of pestilence and disease. For the smallpox, cholera, measles and yellow fever the Spanish brought with them were unknown in the Americas and so the locals had no immunity at all. Between war and disease the native population was decimated, falling from 10 million to little more than 2 million in less than 20 years.

Back in the museum, we gazed at scale models of the Aztec capital the Spaniards had destroyed and looked at a huge slab of stone covered in detailed carvings of people in positions that looked like the throes of death. José explained that this was a sacrificial stone of the kind positioned at the top of the Aztec pyramids for use during sacrificial ceremonies. We wanted to hear more about the Aztec practice of human sacrifice, on the assumption that crystal skulls might somehow have been involved.

José explained that the Aztecs had effectively built their whole empire on the blood of human sacrifice. The main victims were enemy soldiers who had been captured in battle and a whole military machine had been created to provide the capital with a constant supply of sacrifices. So the two driving principles of war and human sacrifice each fed off the other, causing the empire constantly to expand.

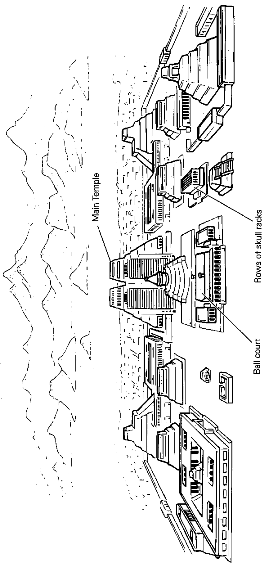

Nobody knows exactly how many victims were sacrificed by the Aztecs. The early Spanish apparently got some indication of the numbers involved by looking at Aztec skull racks, or tzompantli, some examples of which were still carefully preserved in the museum. After the sacrifice, where the heart was ripped out and held high in the air, the victims were usually decapitated. The disembodied head was skewered on a stake and hung in parallel rows along a skull rack. The racks were then prominently displayed in the heart of the city, alongside the main pyramids and the ballcourt.

Bernal Díaz tried to count the number of human skulls on display when the Spaniards first arrived and estimated there to be at least 100,000. Two of his colleagues claimed to have done an accurate count and came up with the figure of 136,000, all at varying stages of decomposition and decay.’14

We were later, however, to meet a contemporary Aztec priest’ by the name of Maestro Tlakaeletl who claimed that the stories of ancient Aztec sacrifice were greatly exaggerated. He told us that the Spanish conquerors had to portray the local people as brutal savages in order to justify their own actions, which amounted to the near total genocide of the peoples of Central America. The skull racks, he claimed, were actually part of ancient Aztec calendrical practices and the heads were those of people who had died quite naturally. The rack was apparently used somewhat like an abacus, to help record the passage of time.

Figure 3: A view of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) as it looked when the Spanish first arrived

Whatever the truth of the matter, the further details that José told us certainly seemed to show that the ancient Aztecs had a very different view of human sacrifice from the total revulsion we have today in the West.

In order to ensure a supply of captives for sacrifice, the Aztecs had carried out a whole series of ritualized battles against neighbouring states, known as ‘the War of the Flowers’. Led by ‘jaguar-knights’, who wore jaguar skins, ‘eagle-warriors’, whose helmet was an eagle-head, and others who wore simply the lower jaw of a human skull on top of their own, Aztec warriors rarely killed enemies on the battlefield, but saved them for ritual slaughter instead. Strangely, once captured, the sacrificial prisoner was no longer seen as an enemy being killed but as a messenger being sent to the gods. When a warrior took a prisoner captive he always proclaimed, ‘Here is my beloved son,’ and the prisoner ritually replied, ‘Here is my revered father.’ For to the Aztecs and many of their neighbours, it was considered a great honour to be sacrificed and the victim was invested with a great dignity bordering almost on the divine.15

Indeed, it seems that sacrifice was such an honourable way to die that it was not only reserved for enemies; the Aztecs also chose victims from within their own ranks. Most often a male child born on a certain day, with the correct astrological alignment, was selected at birth and handed over to another family to be raised until the time of sacrifice. To such a child, dying at the temple was quite simply his true and total purpose in life.

Just after puberty, a few months before the big day, the sacrificial victim would be given four beautiful young brides to live with and would be taught to play beautiful songs on a pipe. Then, when the day came, he would be dressed in richly coloured robes, with bells around his ankles and flowers around his neck. Crowds would gather in the marketplace to cheer him as he walked towards the sacrificial pyramid. As he climbed the up the pyramid he would play his sweet music, stopping to smash his clay pipe on the steps near the top. Reaching the summit he would be given a drink called dolowachi, a painkiller and sedative, as the priests assembled for the ceremony. In the words of Friar de Landa:

‘They conducted him with great display … and placed him on the sacrifice stone. Four of them took hold of his arms and legs, spreading them out…’ 16

The drink also helped the victim’s chest to relax and open up against the curvature of the sacrifice stone to ease the entry of a knife (see plate no. 13):

‘Then the executioner came, with a flint knife (or obsidian blade) in his hand, and with great skill made an incision between the ribs on the left side, below the nipple; then he plunged in his hand and like a ravenous tiger tore out the living heart.’ 17

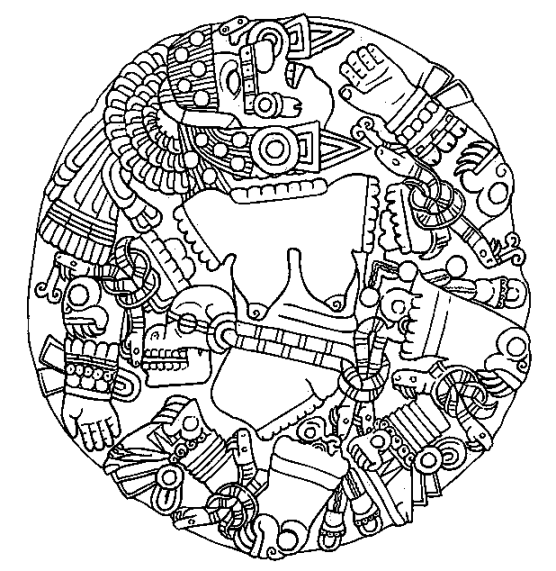

Still beating, the heart was held up to the sky in offering to the sun god Huitzilopochtli. The blood, or ‘divine water’, flowed from the body as the heart, the cuauhnochtli or ‘eagle cactus’, was put in an eagle dish and then burned. The body was thrown down the side of the pyramid, in re-enactment of the mythical struggle between Huitzilopochtli and his elder sister god Coyolxauhqui, whom he was said to have killed. The body was decapitated and the head was impaled on a skull rack (see plate no. 12). The rest of the body was then severed into parts and the flesh divided up among the nobles for ritual cannibalistic meals; they feasted on the symbolic parts of Coyolxauhqui.

We later came across a stone carving of Coyolxauhqui in the museum of the Templo Mayor. It showed the moment when she had tumbled to her death at the hands of her brother god. Coyolxauhqui’s head and limbs had been severed, and a huge skull was attached to her waist. Most archaeologists believe this skull represents the moment of her death and all that would remain of her in this everyday dimension of the ‘middleworld’. I must confess, I wondered whether it might instead have been an image of a crystal skull which she carried around her waist (see Figure 4).

Like being sacrificed at the temple, dying in battle was also an honourable death to the Aztecs. After all, many Aztec warriors died trying to capture victims for sacrifice, so a similar degree of dignity was also attached to the death of a warrior on the battlefield. One old Aztec song captures this sentiment succinctly:

There is nothing like death in war,

Nothing like the flowery death.

So precious to him who gives life.

Far off I see it.

My heart yearns for it!18

Exactly how you died was very important. As José explained, ‘It determined the way you were buried, whether in a foetal position in a clay jar, or spread out flat-eagled on the floor of someone else’s tomb.’

But, far more important than that, the Aztecs believed that how you died determined your afterlife, rather than how you lived, as in our usual Christian belief. To die as a warrior or in sacrifice, the most noble of deaths, would assure you of a place in paradise. After death, the soul of the warrior would journey to the house of the sun where, for the next four years, it would accompany the sun on its daily journey across the sky, firing arrows at the sun to drive it on in its celestial journey. After they had completed this task, warriors’ souls would be turned into butterflies and hummingbirds and they would live in peace in a garden paradise full of flowers. There they would spend their days feeding from the nectar, singing songs and telling stories about the splendours of the ever-shining sun.

Women who died during the ‘battle’ of childbirth would also make the same journey as the warriors to a sun-filled paradise. If you died by drowning or were struck by lightning then a similar fate awaited, except that it was in the watery paradise governed by the rain god Tlaloc.

However, if you experienced the natural death of an ordinary mortal, then only after death would your real battles begin. Your soul would have to undergo a long and arduous journey through the underworld, known as ‘Mictlan’, before reaching its final resting-place. Mictlan was a place of darkness, fear and trembling, filled with a sickening, putrefying stench. This Aztec version of hell was lorded over by Mictlantecuhtli the Great Lord of Death and his wife Mictlancihuatl.

In the museum we could see many statues and other, mostly pottery, artefacts showing these the two great gods of death. Mictlantecuhtli seemed to take many forms, sometimes with a proper human body, but most often his body was made up of nothing but skeletal remains. The only thing that seemed to remain consistent about this character was that his face was always shown as a fleshless human skull, usually with goggle eyes. Likewise, his wife always had a skull for a face and in many of her statues she wore a skull around her neck and was crowned with a whole garland of smaller skulls (see plates 41 and 42).

I asked José whether these gods might have had anything to do with the crystal skulls. He explained that before reaching such a conclusion we should bear in mind that the skull image was almost everywhere in Aztec art and was also associated with many other gods.

Figure 4: Stone carving of the Aztec goddess of the moon Coyolxauhqui with a skull around her waist

One of Quetzalcoad’s opponents, the black Tezcatlipoca, or ‘Smoking Mirror’, was also depicted with a skull for a head. Like Huitzilopochtli, he represented the forces of conflict and change and was believed to have had an ominous dark power. Tezcatlipoca was said to have a dark obsidian mirror in place of his left foot, a magical ‘smoking mirror’ which enabled him to witness the activities of gods and of men wherever they were. The fact that he was depicted with a skull for a head and was able to see into the other dimensions might equally imply a link between this god and crystal skulls. But, as we had already seen in the British Museum, Tezcatlipoca’s skull was usually shown covered in red and black stripes.

By now we had arrived at a huge statue over 15 feet (4 metres) tall and weighing over 10 tons (10 tonnes). This had originally been discovered at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but the Mexican authorities apparently deemed it just too frightening to look upon and promptly reburied it. Though it has also been said that the real reason for the reburial was to avoid the embarrassment of having to admit that they could not explain how the ‘primitive’ and barbaric Aztecs could have made such a thing, or that it was a political move, designed to avoid stirring up Aztec descendants’ memories of the original destruction of their culture under the Spanish.

The statue was of the original Aztec goddess known as Coatlicue, or ‘she of the serpent skirt’. Coatlicue was the mother of all the Aztec gods, the goddess of the Earth, and therefore the goddess of life and death. The statue was truly a disturbing image. The head was simply not depicted – seemingly the goddess’s face was just too horrific for mortal contemplation – and instead twin serpents indicated blood spurting from the place where it should have been. The goddess’s skirt was made of snakes, who, by shedding their skins, indicate the ongoing process of death and renewal, and she had claws to show the destructive side of her nature. Around her neck she wore a garland of severed hands and human hearts, and at her waist another fleshless skull stared out at us. Like Mictlantecuhtli, this skull had goggle eyes, apparently a sign that the goddess watched over both life and death, although again I wondered whether this image might really have been a crystal skull.

Figure 5: Massive stone statue of the Aztec goddess of creation Coatlicue with several hands, gouged out hearts and a skull around her neck and waist

What seemed so fascinating about this great statue was that, although Coatlicue was the goddess of the Earth and therefore of life, she was represented with all the paraphernalia of death. José explained that throughout Mesoamerican culture a curious duality had always been seen to exist between the forces of life and death. The goddess of the Earth had the power to create new life, but also to take it away. For it is Mother Earth that gives us life, but she also takes it away again when we die.

This was all part of the ancients’ view that both life and death are inseparable sides of the same coin, that you just cannot have one without the other. So, for the native peoples of Central America, there was no real need to be afraid of death, or to try to brush the whole subject under the carpet, as we tend to do today in the West. Death was simply a transition to another place and was usually something to look forward to.

This different attitude to life and death could even be seen in the Aztecs’ version of hell. Although most people went to the underworld, it was not some perpetual inferno, as in the Christian view. Like the original journey through the womb at the start of life, the journey through the underworld was dark and restricting, but ultimately, when you reached your final resting-place, even the underworld was not really that bad at all.

As we were gazing at the great statue of Coatlicue, mulling over life and death, José said there was something else he wanted to show us. He led us into a little side-room off the main Aztec Hall of the museum and showed us what was inside one of the cabinets. There hung a small necklace of 12 tiny skulls carved of bone, with what looked like a space for a thirteenth. This necklace was clearly labelled as having been found in Guerrero state and dated to around AD 1000 (see plate no. 40).

José led us over to another cabinet and asked us to take a close look inside. Peering through the glass, we were somewhat surprised to see two tiny crystal skulls. These skulls were only about 2” (5 cm) high and each had a vertical hole running through from top to bottom. They seemed quite roughly carved but each was beautifully transparent. One was labelled Aztec’ and the other simply ‘Mixtec’ (a neighbouring civilization the Aztecs had defeated). No further details were given.

We were amazed. I exclaimed, ‘So the crystal skulls really are Aztec after all!’

But José almost immediately explained that it wasn’t quite that straightforward. He said that nobody really knew quite what these crystal skulls represented or what they had been used for, or, for that matter, where they had really come from. He said the skulls had been labelled Aztec and Mixtec because this was all that the museum records actually said about them. The records apparently went back at least as far as the middle of the nineteenth century, but contained no precise details of exactly which archaeological dig the skulls had been found on. They might not even have come from a dig at all. None the less the museum authorities were pretty convinced that these little skulls were genuinely ancient.

José said there would be several problems, however, even in making such an assumption. Whilst it was known from the early Spanish accounts that the Aztecs and Mixtecs were experts at carving precious stones, and although these accounts did specifically mention crystal, it was a very rare material in Mexico in those days. José could not think of any examples of truly large ancient pieces of crystal ever having been found. Of course, the possibility that the large skulls really were ancient could not be ruled out, particularly given the importance of the skull image itself to the Aztecs, but the real problem with all Mesoamerican archaeology was that the early European settlers had destroyed so much of the evidence.

As soon as the Spanish had taken control of the Aztec empire they had begun the systematic destruction not only of most of its people, but also of the whole culture – all in the name of Christianity. No doubt the practice of human sacrifice fired the Spanish with the belief that they were totally justified in imposing Christianity on these ‘barbaric’ people. But the choice for the indigenous people was convert or be killed. Like the Nazis over 400 years later, the early Spanish settlers even used children to spy on their parents and report them to the new authorities if they were suspected of trying to carry on the old religious ways.19

Almost all previous books and records were seized and burned, the finest works of Mesoamerican culture reduced to ashes in a frenzy of bookburning and the destruction of ‘idols’. The soldiers were joined in these activities by the early Franciscan and Dominican monks. One friar described his activities:

‘We found great numbers of books … but as they contained nothing but superstitions and falsehoods of the devil we burned them all, which the natives took most grievously, and which gave them great pain.’ 20

Few of these now priceless manuscripts escaped destruction as the unique testimony of a whole culture was almost completely wiped from the face of the Earth. Indeed, it is a source of some irony that the main source of information we have about the ancient Aztecs today are the writings of the zealous monks and friars who needed to record the ‘pagan’ and ‘un-Christian’ rituals, ceremonies and beliefs in order to identify quite what it was they were hoping to eradicate. Others secretly preserved some record, albeit in a much reduced and impoverished form, of the culture they originally intended to obliterate completely, as they gradually became aware of the tragic loss to humanity that was unfolding before them.

None the less, nearly all of the Aztec artwork and sculpture, and even the architecture, was destroyed. Cortés ordered Tenochtitlan to be totally levelled and then built a huge cathedral, much of which still stands today, on top of the main temple in the city square. All forms of native artistic expression were smashed and burned. The friars looked upon the art and culture of the Aztecs, their painted scrolls and fine sculptures, as ‘works of the Devil, designed by the evil one to delude the Indians and to prevent them from accepting Christianity’.21 Precious metals were also hunted out, to be melted down and sent back to Spain to swell the coffers of the Spanish empire. The Aztecs were apparently appalled at the greed of the Spanish for the ‘yellow metal’. I was reminded of some of the visions Nick Nocerino had seen inside his crystal skull.

The early Spanish settler Father Burgoa described the destruction of one particular ‘idol’ that was held in a sanctuary in a place called Achiotlan:

‘The material was of marvellous value … engraved with the greatest skill…

‘The stone was so transparent that it shone from its interior with the brightness of a candle flame. It was a very old jewel, and there is no tradition extant concerning the origin of its veneration and worship.’ 22

Father Burgoa also reported that this stone was seized by the first missionary, Father Benito, who ‘had it ground up, although another Spaniard offered three thousand ducats for it, stirred the powder in water, poured it upon the earth and trod upon it’.23

It is certainly hard to imagine that crystal skulls could have survived such ravages, although, as Dr John Pohl of the University of California had already said to us, ‘The crystal skulls would have been considered so precious by the Indian people that they would have done their best not to let the Spanish get hold of them.’

Some of the relatively few objects that did remain were the monumental stone statues and carvings, such as Coatlicue, which were so large and made of such hard and enduring igneous rock that they could not be smashed, burned or otherwise destroyed. What the Spanish did with these was to bury them; many have only recently been rediscovered. But, apart from these massive stone monoliths, little remains of Aztec art.

But there was one other piece of evidence, said José, that we might be interested in and which implied that the crystal skulls might really be Aztec. We accompanied him to the nearby Museo Templo Mayor, the Museum of the Main Temple, situated in the centre of the Zócalo Square in the heart of Mexico City. The square was surrounded by colonial buildings on all sides and suggested former colonial might. I found something depressing about the grey drabness of the buildings and the relentless flow of cars that passed in front of them. On the approach to this museum, right beside the cathedral, which is now covered in scaffolding to support it as it gradually sinks lower into the soft subsoil, we could still see the original foundations of the temple, which had only recently been excavated.

As we entered the museum we were greeted by the sight of row upon row upon row of carved stone skulls, a version of the skull rack or tzompantli, but permanently preserved in stone, which had been found buried beneath the cathedral. We were also taken aback to see a rack on which real human skulls were displayed. We wondered what had created this fascination with death. Had the Aztecs lined up these skulls simply as trophies of war, as a statement of power, or were there other reasons? Certainly many believe the stone versions of the tzompantli did have something to do with the ancient calendar.

José took us on, past rows of real skull racks and various statues of ancient gods, many decorated with skulls, to another small glass cabinet. Inside were some of the few pieces of crystal definitely known to be at least as old as the Aztecs. They had been found in the 1970s during the excavation of the Templo Mayor site. As was common Aztec practice, the pyramids at this site had been built up in several layers, being added to at regular intervals as the empire expanded. Rebuilding is thought to have occurred every 52 years, in accordance with the cycles of the ancient calendar. A basalt funerary casket lay inside the innermost layer, beneath a chac-mool statue often thought to represent the great god Quetzalcoatl. This is where the crystal artefacts had been found – several crystal cylinders, thought to represent the feathered ‘tail’ of Quetzalcoatl, crystal lip-plugs, crystal ear-spools and, perhaps most interesting of all, a row of 13 small crystal beads, thought to have been worn as part of a necklace. Given their position in the innermost layer of the pyramid, these pieces of crystal dated back to at least AD 1390.

The practice had been to bury and burn important people inside such caskets, and the original inhabitant of this particular one had been incinerated completely. Only the small crystals had survived the flames of cremation. Archaeologists have been somewhat puzzled by these finds because crystal was such a rare material to the Aztecs and so was reserved only for those of the highest nobility. The most likely explanation is that these crystal artefacts were originally worn by one of the ‘watchers of the skies’, the astronomers, who were the highest strata of society. Crystal, it seems, was seen as the sacred material of the heavens and associated with the ability to see clearly, so it was reserved for the astronomer class.

Astronomers were very important for the Aztecs, who very much based their lives around the observation of the skies. Though materially they had little, ‘only stones and soft metals’, as José put it, they ‘elevated themselves to the position of the skies’ and acquired great skills in astronomy. On their original migration they had oriented themselves using the position of the polar star, as did later navigators across the Atlantic, and when they settled in Mexico they oriented all their sacred buildings to the four cardinal points of the compass. Furthermore, most of their deities were placed among the sky forces. Their daily lives and all their rituals and ceremonies were guided by the movement of the heavenly bodies.

Even the practice of human sacrifice was believed to have astrological significance. For, to the Aztecs, the sun was a mortal being. They believed it had to be fed, almost daily, if it was to continue to shine. This was why they always placed the heart of the sacrificial victim in an offering pot or receptacle, burned it and held it up to the sky. They believed that when they did this the spirit of an eagle would fly down from the sky and snatch up the spirit of the person’s heart in its claws, carrying it back up from the Earth to the heavens to feed the sun. In this way, they believed the soul of the sacrificial victim joined the sun and kept it fed.

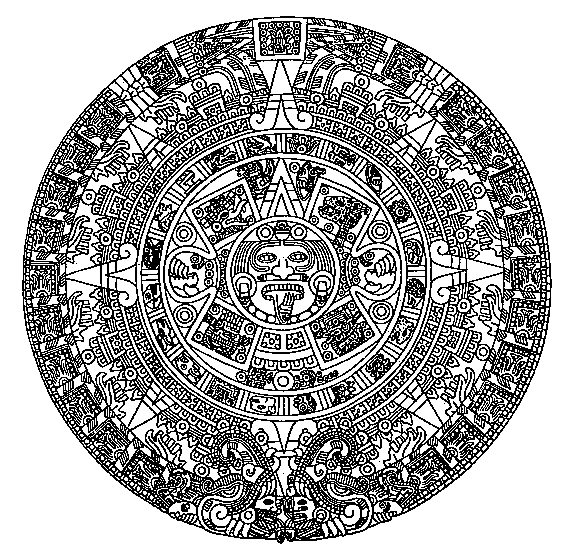

The Aztecs’ views on human sacrifice were related to their beliefs about the calendar and the end of time. José had already shown us the famous Aztec Calendar Stone, a huge circular slab unearthed in 1791 from the remains of the Main Temple. At first this was thought to be simply an ornate sacrificial stone, but in fact it held the key to the Aztecs’ beliefs about the history of the world and the end of time.

This stone showed at its centre a human face with its tongue hanging out, representing the sun god Tonatiuh demanding offerings of blood and human sacrifice. Radiating out from this were several sub-sections. Some of these sections represented the eight divisions of the day, the Aztecs’ equivalent of our hours, while others represented their months, which were each 20 days long. There were 13 months in all in each of their sacred years, or tonalamatl. One of these sections was even represented by the image of a human skull.

Figure 6: The Aztec Calendar Stone

The four outermost layers of this cyclical calendar represented the four previous ‘Suns’. These Suns related to the different eras of the Earth. For, like all Mesoamerican peoples, the Aztecs believed that the world had been created and destroyed several times before now, four times in fact. The Aztec Calendar Stone, as well as many of their other stone monuments and surviving manuscripts, showed that the Aztecs believed they lived in the age of the ‘Fifth Sun’, the age we are still in today. Each of the four previous worlds, or Suns, lasted thousands of years, but each also ended in a great cataclysm. There is some disagreement over the precise order in which each of these worlds ended, but the Calendar Stone itself, probably the most reliable guide, gives the following order:

Léon-Portilla gave a detailed account of what he heard about the end of this world: ‘Thus they perished, they were swallowed by the waters and they became fish … the water lasted 52 years and with this ended their years … the heavens collapsed upon them and … they perished’ and ‘all the mountains perished’,27 too, swallowed up by the waters that flooded the Earth. The Vaticano-Latin Codex again adds, however, that one couple survived the flood, because ‘they were protected by a tree’, in an account with remarkable similarities to the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark.

According to Léon-Portilla’s account, ‘This Fifth Sun, its sign 4-Movement, is called the Sun of Movement because it moves and follows its path.’28 But in the Aztec language, Nahuatl, the word ollin means not only ‘movement’ but also ‘earthquake’ and so Léon-Portilla’s account continues, ‘… as the elders continue to say, under this Sun there will be earthquakes and hunger, and then our end shall come.’29 As the Vaticano-Latin Codex puts it, ‘There will be a movement of the Earth and from this we shall all perish.’30 Other accounts, however, suggest that the cataclysm which will end the current and final world will be a combination of all the destructive forces of nature, the earth, the air and the water, in a final conflagration of immense heat and drought and of ‘fire from the skies’ followed by darkness and cold, with hurricane winds and torrential rain, and featuring a combination of earthquakes, volcanic activity and devastating floods. Again I was reminded of the visions Nick Nocerino had seen inside his skull, also of the information Carole Wilson had channelled from the Mitchell-Hedges skull.

According to Léon-Portilla, ‘The Aztec myth of the Five Suns explains man’s destiny and his unavoidable end.’31 This reflects the Aztecs’ belief that our world is perishable and that time consists of a chain of cycles doomed to lead to annihilation.

But the Aztecs did not appear to know exactly when the current Sun was due to end. They believed that it was already very old and was likely to end soon. But they also thought that their own actions could have an effect on how long it would last. They believed that they had a duty to try to prevent the sun from dying, and that this could be done through human beings making personal sacrifices in order to keep the sun shining and the Earth in good health. In their case this involved feeding the sun on a diet of human hearts and blood.

This is why, for the Aztecs, ritual human sacrifice was absolutely essential. They believed that at the beginning of this Fifth Sun the only way to persuade the sun to shine again had been to give it the most precious gift, the gift of life itself. And so they continued offering their own lives. It was the only way of keeping the sun alive and avoiding the great cataclysm that otherwise threatened to engulf the entire Earth.

José believed that the sacrificial practices of the Aztecs had been motivated by a corruption of the idea of sacrificing oneself for the benefit of others, putting aside the concerns of the ego in order to serve the good of all people and the divine. So, he suggested, the root of Aztec sacrificial practice was actually a central tenet of many of the world’s religions, the idea of offering yourself up to God. Evangelical Christians today speak of ‘giving your heart to Jesus’ or ‘giving your heart to God’. The Aztecs had taken this quite literally, offering their still beating hearts up to the god of the sun.

I could see that the Aztecs’ bloody rituals now seemed to make some kind of warped but still logical sense. But it was horrendous to think that they took this idea of personal sacrifice to such literal extremes.

But I was still curious to understand why the image of a skull appeared on the mysterious Aztec Calendar Stone and whether there was any evidence that crystal skulls might somehow have been involved in the practice of human sacrifice and this rathet strange set of beliefs about the end of the world. José explained that to properly understand both the image of the skull and the calendar we should really look further into the culture of the Aztecs’ predecessors, the Toltecs, the Teotihuacános and the Maya. The Aztecs were thought to have inherited much of their calendar, practices, beliefs and skull imagery from these civilizations. The calendar especially had been traced back to the ancient Mayans, who kept the most detailed records of time. But, as we had already heard, their civilization mysteriously collapsed centuries before the Aztecs arose and the ruins of their cities lay hundreds of miles further south, so we could not readily visit them from Mexico City. We could, however, visit the ruins of Tula, the Toltecs’ great city, and of Teotihuacán, where the Aztecs believed the current Sun had been born.

The following day we drove out to Tula. This ruined city, dated to over 1,000 years old, was surrounded by low-lying mountains. Little of the original architecture remained. The largest still-standing monument was a low pyramid crowned with pillars that had been intricately carved to represent standing men or gods. This was known as ‘the Temple of the Morning Star’ or ‘the Temple of the Atlantes’. Each of its pillars was carefully aligned with the heavenly bodies and this is where the Toltecs are thought to have performed a sacred ceremony every 52 years.

Every 52 years was when the ancient calendar completed a full cycle of sacred and solar years. This was a cycle of four lots of 13 years after which time the 13 months of the 260-day sacred calendar returned to their original starting position relative to the 365-days of the solar year. The end of each 52-year period was therefore a very precarious time for the Toltecs, and their Aztec descendants, as it represented one of the occasions when the current Sun was most likely to end. Accordingly, a great number of human sacrifices took place at that time. Also, every 52 years at sunset, the Aztec priests were said to have climbed to the temple on top of the ‘Hill of the Star’, thought perhaps to have been this same pyramid at Tula. There they would await either the end of the world or what was known as ‘the start of the new fires’. They would wait in trepidation until the Pleiades constellation appeared in the sky. This was a sign that the sun would continue to shine, and so they would celebrate the birth of a new cycle of time by lighting ‘the new fires’. These fires would then be passed on like an Olympic flame right across the whole empire and the original flame would be kept burning for the following 52 years.

Behind the Temple of the Atlantes was a wall, known as the coatepantli, or serpent wall, which had apparently once surrounded the whole pyramid. This wall was decorated with stone carvings of what looked like a series of snakes or serpents, but each with a human skull for a head (see plate no. 23). Each skull was shown with its jaws wide open, seemingly biting or swallowing the tail of the serpent in front.

The building still baffled archaeologists. It was clearly devoted to ‘the Atlantes’, but who they were remained a mystery, as did the reason why these wall carvings combined images of Quetzalcoatl, the original god of Mesoamerica, with the skull. Traditionally Quetzalcoatl was shown as a flying snake or rainbow-coloured feathered serpent, but this building clearly showed that there was some connection between this god, a mysterious group known as ‘the Atlantes’ and the image of the human skull. But what?

With these unanswered questions still playing in my mind, we set off for the ruins of the great city of Teotihuacán. This city was known to the Aztecs as ‘the place where the sun had been born’, or ‘the place of the men who had the road of the gods’ or ‘the place where the heavens meet the Earth’. This site, only an hour away from Mexico City, was the place Eugène Boban had visited during the time he was selling crystal skulls. For some reason I had the feeling it might contain some important clue in our search for the origin of the skulls.

Aztec legend had it that in a time of great darkness, before the current Sun, two men, Tecuciztecatl and Nanahatzin, had enabled the current Sun to shine by committing the original and ultimate sacrifice in this very city, throwing themselves off the sides of the great pyramids into the ‘sacred flame’. As a result they flew up into the heavens where they became gods themselves: the sun and the moon.

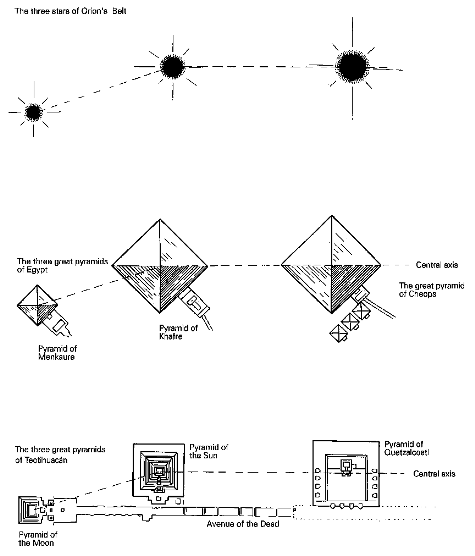

The remnants of this huge city turned out to be a most impressive archaeological site. Again surrounded by low mountains, but far larger than Tula, Teotihuacán had been built on a very grand scale. The ruins of the city covered an area of around eight square miles and at their centre lay the most massive group of pyramids I had ever seen. Teotihuacán actually features the largest group of pyramids in the whole of the Americas, with three great pyramids arranged in a row, and the similarities with the Egyptian pyramids at Giza struck me almost immediately.

At its peak the city had housed around 200,000 inhabitants and the extent of its cultural and trading influence had been enormous. Traces of its artistic and cultural style could be found even in Mayan cities such as Tikal, over 600 miles away. Like the Maya, nobody knew for sure quite who the Teotihuacános really were, where they came from or what happened to them. It was also uncertain what language they spoke and how old their great city really was. Construction of the pyramids is generally thought to have started at around the time of Christ, but many have claimed they are much older. Certainly the whole city was mysteriously abandoned over 1,000 years ago, presumably some time between AD 500 and 750.

Teotihuacán had been revered by the Aztecs, who had already found it in ruins and had named the great pyramids ‘the Pyramid of the Sun’, ‘the Pyramid of the Moon’ and ‘the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl’. They had also been responsible for naming the great central ‘Avenue of the Dead’.

We climbed up nearly 150 feet (45 metres) to the top of the Pyramid of the Moon, as this was said to afford the best view of the whole city. We stood on the spot where a temple had once been. The view was truly spectacular. The orderly lines of the city lay before us. To the south lay the Avenue of the Dead, with stone embankments and small pyramids all along its perfectly straight sides. Over 50 yards (45 metres) wide and with a surviving section over three miles (four kilometres) long, it stretched on ahead of us, disappearing into the distant haze (see plate no. 6). The purpose of this great avenue remains a mystery. Some have even suggested that it might have been some kind of ancient runway for extra-terrestrial craft, but another, perhaps more plausible, explanation is that it had once been filled with water and functioned as some form of ancient seismograph designed to measure earthquake activity. Careful measurement of ‘standing waves’ appearing across still water can indicate the strength and location of earthquakes happening elsewhere around the globe and so the avenue might at one time have been used to predict earthquakes in the immediate area.’32

The purpose of the pyramids themselves was also unknown, although they almost undoubtedly had religious and astronomical significance. To the east of the great Avenue of the Dead we could see the great towering bulk of the Pyramid of the Sun, over 700 feet (215 metres) wide at its base and over 200 feet (60 metres) high, and once also crowned with a temple. Further along the Avenue of the Dead we could also see the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl. Whilst this was now less than 100 feet (30 metres) tall, what remains is thought to have been an early unfinished version. For this smaller pyramid is still surrounded on all sides by foundations that extend to an even greater size than the neighbouring great Pyramid of the Sun.

One of the reasons why these pyramids have always puzzled archaeologists is because their size, layout and particularly their positions relative to each other almost exactly match those of the three pyramids at Giza. The base of the Pyramid of the Sun matches to within inches that of one of these pyramids.33 Furthermore, the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl and the Pyramid of the Sun are both accurately aligned with each other so that if you were to run a line between their summits it would run precisely parallel to the Avenue of the Dead, whilst the smaller Pyramid of the Moon is slightly offset to the left, at the very head of this great avenue. This layout follows almost exactly the same pattern as the Giza pyramids.

Although the Teotihuacán pyramids are somewhat lower than their Egyptian equivalents, when seen from the air the only difference between these two sets of pyramids is that the Egyptian ones are at 45° to the central axis whilst in Teotihuacán they run at right angles to it. Also at Teotihuacán the Avenue of the Dead runs exactly parallel to this central axis, whilst in Egypt there is no sign of any such great avenue. None the less, if you were to lay a plan view of the pyramids of Egypt on top of a plan view of the pyramids of Teotihuacán, each drawn to the same scale, the area of each pyramid and the summit of each pyramid would almost exactly coincide. The Pyramid of Cheops would match the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl, the Pyramid of Khafre would match the Pyramid of the Sun, and the Pyramid of Menkaure would match the Pyramid of the Moon (see Figure 8).

Quite what the significance of this, presumably sacred, layout is, nobody is totally sure. Recent studies of the Giza pyramids in Egypt have pointed out that this layout exactly matches the relative size and position of the three stars that make up Orion’s Belt and have suggested that the ancient Egyptians may have been trying to somehow reproduce the heavens on Earth. It is quite likely therefore that the layout of the three pyramids of Teotihuacán might also have some connection with the stars and possibly the constellation of Orion, which did have its own small part to play in the complex workings of the ancient Mesoamerican calendar.

Figure 7: Reconstruction of the ancient city of Toetihuacán looking down the avenue of the Dead

In another similarity with Egypt, it has recently been discovered that the Pyramid of the Sun, just like the Great Pyramid of Cheops, actually contains a secret mathematical code built into its dimensions. The mathematical relationship between the height of the pyramid and the length of the perimeter at its base actually contains the famous mathematical constant pi. (In Teotihuacán the mathematical relationship equals two times pi; in Egypt it is four times pi.) This suggests that the ancient Teotihuacános knew how to calculate the circumference of a circle, or a sphere such as the Earth, by multiplying its radius or diameter by a factor of pi. This implies that, at least 1,000 years before the Europeans, the Teotihuacános were not only aware that the Earth was round but could accurately measure its dimensions for use in precise scientific calculations.34

Indeed, it is now widely accepted that the whole layout of Teotihuacán had some deep astrological significance, as the whole city was built according to a set of incredibly accurate alignments that intimately tied the city to the movements of the planets and the stars.

The Pyramid of the Sun, for example, had probably been given this name by the Aztecs precisely because it was positioned in such a way that it functioned almost like a huge solar and astronomical clock. The eastern face of the pyramid is carefully aligned so that it receives the rays of the sun full on only at the spring and autumn equinoxes, 20 March and 22 September.35 As Graham Hancock recently pointed out in his book Fingerprints of the Gods, on these days, the passing of the sun overhead also results in the progressive obliteration of a perfectly straight shadow that runs along the lowest slope of the western façade, so that this shadow disappears only and precisely at noon. This whole process, from complete shadow to complete illumination, always takes exactly 66.6 seconds.36 It has taken precisely this length of time every year, presumably ever since the pyramid was built, and it will continue to do so for as long as the pyramid continues to stand. In this way the ancients could check the arrival of midday at the equinoxes down to the second.

But these are not the only astronomical alignments. In every direction the city was laid out in harmony with the universe as the Teotihuacános understood it, or even, as one recent study has suggested, as a precise scale model of our solar system.37 If the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl were taken as representing the position of the sun, then many of the other structures spread out along the Avenue of the Dead and beyond would actually seem to indicate the precise distance of the orbits of each of the other planets from the sun. The Pyramid of the Sun, for example is the correct distance away for the position of Saturn and the Pyramid of the Moon the right distance for Uranus. This suggests that the Teotihuacános not only knew about many of the planets we did not discover until very recently, but were also able to accurately calculate their distance from the sun.

This particular study was still controversial, but the astronomical alignment that interested us the most was now very widely accepted and also involved the image of a skull. This was a huge carved stone statue of a skull that had a strangely two-dimensional appearance. It was grim and imposing, with what looked like a slot for a nose and a wide straight mouth with its red-painted tongue hanging out. The whole skull was surrounded by a circle of what looked like a deeply carved version of the rays of the sun, again all painted red (see plate no. 17). It had often been assumed that this was simply a representation of the sun god, but, as José had already pointed out, the sun god was usually represented with a full human face.

The interesting thing was where this huge image had originally been found. It had been discovered at the bottom of the western face of the Pyramid of the Sun, in the centre, along the edge of the Avenue of the Dead, pointing to a particular spot on the western horizon. In fact the whole city had been arranged along two axes: the Avenue of the Dead, and the east–west axis marked out by the direction in which the skull and the pyramid were facing.’38

It had long been assumed that this stone skull represented only the setting of the sun and that its original location pointed towards a spot on the horizon where, on the day that the sun passed directly overhead, the sun also duly set. Given the location of Teotihuacán, the sun usually passes to the south, but in a few of the summer months it passes to the north. The days when the sun passes directly overhead are 19 May and 25 September. Indeed, it had long been believed that the Pyramid of the Sun was specifically oriented so that, as well as marking the equinoxes, it also marked these days when the sun passed directly overhead. It had long been held that on these two days the western face of the pyramid, and therefore the huge stone skull, pointed at precisely the position of the setting sun.39

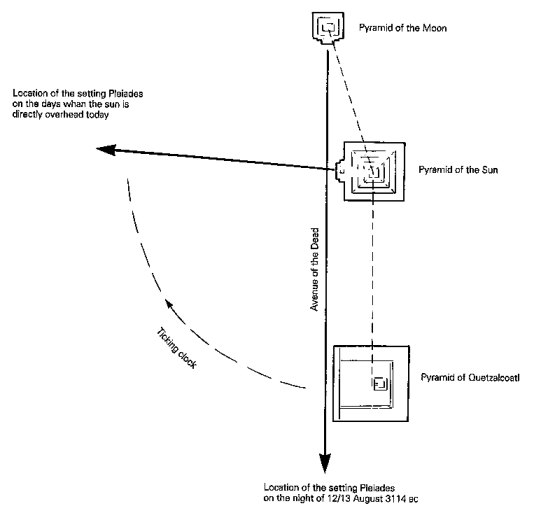

Figure 8

But this theory has recently been tested in various studies by archaeo-astronomers such as Anthony Aveni of Colgate University.40 His team observed that on the days when the sun passes directly overhead, the Pleiades make their first annual predawn appearance. They also discovered that on these two key days of the year the western face of the pyramid, and therefore this massive stone skull, was actually aligned not with the setting sun but with the precise spot where the Pleiades disappear beneath the horizon. To the ancient Teotihuacános, there was clearly some connection between the image of the skull and the Pleiades constellation.

Anthony Aveni and his team discovered that the sun does also set at this point on the horizon, but only on the night of the 12/13 August.41 Curiously enough, this is precisely the anniversary of the start of the last Great Cycle of the ancient Mesoamerican calendar, which is understood to have started on 13 August 3114 BC. To the ancients this was ‘the day the sun had been born’, so perhaps this great city dated back to that time?

Another study has suggested that the great Avenue of the Dead might have been ‘built to face the setting of the Pleiades at the time [Teotihuacán] was constructed’.42 So, as Ceri and I gazed across the site, it suddenly struck me that perhaps the whole layout of Teotihuacán was like a huge clock-face, centred around the Pyramid of the Sun. The Avenue of the Dead, like one hand of a clock, pointed at where the Pleiades would have set on the southern horizon on the 12 August 3114 BC, whilst the skull beneath the Pyramid of the Sun, like the other hand of the clock, pointed at the place on the western horizon where the Pleiades set today. It is almost as though the hand of the clock pointing to the Pleiades has gradually been ticking around towards the point on the horizon the skull had always been facing. Again, another connection between the image of the skull and the star cluster of the Pleiades had been found (see Figure 9).

I also found myself wondering whether, if the three pyramids of Teotihuacán were taken to represent the three stars of Orion’s belt, the stone skull beneath the Pyramid of the Sun had perhaps pointed to a place in the night sky where the Pleiades had at one time been located relative to the three stars of Orion.

But other discoveries had also been made at the spot where this huge stone skull had been found. As we made our way to the foot of the Pyramid of the Sun more surprises were in store. We passed by the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl beneath which some skeletons had recently been found. These were thought to have been sacrificial victims and each was adorned with a complete necklace of whole human jaws. Along the edge of the Avenue of the Dead and around the base of the Pyramid of the Sun we could see that archaeologists had recently begun to uncover a whole subterranean layer of the city that had been carefully buried. A whole labyrinth of subterranean passageways and a complete network of caves apparently surrounded the Pyramid of the Sun. But the most surprising discovery had been made in 1971.

Immediately behind the spot where the stone skull had once stood archaeologists had uncovered, quite by accident, a doorway leading right under the Pyramid of the Sun. Though we were forbidden from entering this passageway, we later learned that this ‘entrance may have been the initial siting point for the east-west alignment that was so crucial in the city plan’.43 A tunnel only seven feet (two metres) high but over 300 feet (90 metres) long leads from this entrance at the base of the western pyramid stairway right into a mysterious natural cave hidden almost directly beneath the centre of the pyramid. As we read later in National Geographic, ‘The cave, therefore, may have been the holiest of holies – the very place where Teotihuacános believed the world was born.’44

This mysterious natural cave was ‘of spacious dimensions, which had been artificially enlarged into a shape very similar to that of a four-leafed clover’.45 Each of the four large chambers of the cave was about 60 feet (18 metres) in circumference. As Mesoamerican expert Dr Karl Taube of the University of California at Riverside commented, ‘The Teotihuacános must have used the cave for something, because its walls were reshaped and in some places reroofed.’46 There was also a complex system of interlocking segments of carved rock pipes, possibly a drainage system, although there was and still is certainly no sign of any water there. Only a few small, mostly broken artefacts of engraved slate and obsidian remained, as though perhaps the cave had at some time been robbed or otherwise cleared.

I wondered whether the mysterious piped technology might have had something to do with another strange discovery found at Teotihuacán. One of the uppermost layers of the Pyramid of the Sun had originally been made from the unusual material of mica. Although this had been robbed at the beginning of the twentieth century, two huge pieces of mica, each 90 feet (27 metres) square, had been found still intact beneath the normal stone floor of ‘the Mica Temple’ situated nearby. The puzzling thing about this discovery was that these pieces of mica, put in place well over 1,000 years ago, were of a type known naturally to exist at the nearest over 2,000 miles away. The ancient Teotihuacános, it seemed, had brought this material all the way from Brazil.47 Archaeologists had been intrigued why they should do such a thing when the material was kept well hidden out of sight and so could hardly be considered decorative. Today, mica is primarily used in the electronics industry, where it has a multitude of technological applications, in capacitors or as a thermal and electronic insulator. I was immediately reminded of the incredible electronic properties of the quartz crystal from which the skulls were made.

So what had the mysterious cave under the pyramid really been used for? The well known Mexican archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma commented, ‘Its location and privacy suggest that it may have been one of the most sacred spots in the city, although we can’t yet say what happened here,’48 while according to National Geographic, the cave may have been some kind of ‘oracle or meeting place for secret cults’.49 Clearly nobody really knew for sure, but what was certain was that the entrance to this secret chamber was guarded by the image of a skull, pointing towards the Pleiades.

As we turned back to look at the site once more before leaving, I found myself casting my mind back to what José had told us in the museum. When Moctezuma began to feel a sense of foreboding about the future of the Aztec empire, he had consulted the priests, the seers who knew everything that was ‘locked in the mountains’. Given the importance of Teotihuacán to the Aztecs, could those have been the man-made mountains of the pyramids? Was this the very site where the Aztec psychics had worked? Was this the secret location where the crystal skulls had once been stored?

Figure 9: The ‘clock-face’ of Teotihuacán