One _____________________________________________________________

Wedge Issues in Presidential Campaigns

AT THE 2004 Democratic National Convention in Boston, Massachusetts, the topic of stem cell research received top billing in a prime-time speech by the son of former president Ronald Reagan.

A few of you may be surprised to see someone with my last name showing up to speak at a Democratic convention. Let me assure you, I am not here to make a political speech. … I am here tonight to talk about the issue of research into what may be the greatest medical breakthrough in our or in any lifetime: the use of embryonic stem cells.1

Network news coverage of the nominating conventions reached an all-time low in 2004, dropping from twenty-six hours of coverage in 1976 to a measly three hours in 2004, so Ronald Prescott Reagan’s speech appeared during an especially coveted and carefully scripted time slot. With the United States embroiled in a controversial war in the Middle East and the economy faltering, why would the Democrats prioritize a “nonpolitical” speech about stem cell research?

The answer points to the heart of contemporary electoral contests. Democrats emphasized their support of stem cell research during the convention and later in stump speeches and campaign mail because they believed the issue offered them an advantage among Independents and Republicans who disagreed with President Bush’s policy limiting it. Democratic pollster Peter Hart explained that the issue of stem cell research had the potential to “attract support from disease sufferers and families who otherwise agree with Bush on public policy but feel ‘alienated’ by his decision to restrict federal funding for embryonic stem cell research.”2 Republican pollster Robert Moran offered a similar assessment, “This is not an issue you can run and hide from. … If this is going to negatively impact President Bush, it will likely be in places like the Philadelphia suburbs, where you have moderate swing-voting economic conservatives.”3 Ron Reagan’s highly touted speech was an appeal not to core Democratic supporters, but to otherwise Republican voters. In other words, the Democrats were using stem cell research as a wedge issue to divide the traditional coalition of Republican supporters.

Turning the clock back four years, we find then-candidate George W. Bush using stem cell research as part of a parallel strategy in the 2000 presidential campaign. Most people do not remember that this was even an issue in that campaign, as it was not mentioned in the nominating speeches of either candidate, was not covered in their television advertising or raised in the presidential debates, and the candidates’ positions were not available on their campaign Web sites. In fact, a CNN/USA Today poll at the time found that 56 percent of respondents “didn’t know enough to say” when asked their opinion on the issue. Yet in the midst of the 2000 presidential campaign, Bush sent a letter to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in which he underscored his position that “taxpayer funds should not underwrite research that involves the destruction of live human embryos.”

The Bush campaign was trying to make inroads into the Catholic vote, a traditionally Democratic constituency that often disagreed with the national party on moral issues. Opposition to abortion and stem cell research offered Bush common ground with religious voters of different denominations and across party affiliations. So, again, the issue of stem cell research was raised not to throw “red meat” to the partisan faithful, but as a wedge issue aimed at pulling away voters from the opposition camp. Because stem cell research was a relatively obscure scientific question in 2000, Bush was able to narrowly target a campaign promise on the issue without much concern that the position would carry electoral risk with the broader electorate. But in staking a position on the issue, Bush created a strategic opportunity for Democrats to use stem cell research as a wedge issue in the 2004 campaign.

Stem cell research is just one of a long list of divisive issues—abortion, gay marriage, minimum wage, school vouchers, immigration, and so on—that have become standard playbook fare in contemporary presidential campaigns. The prominence of these controversial issues challenges the conventional wisdom in political science that rational candidates should run to the center on public policy matters and avoid controversial issues at all costs in their efforts to be elected to office. What explains candidates’ willingness to campaign on these divisive issues?

In this book, we offer three key arguments that help to answer this question: First, some of the most persuadable voters in the electorate—those voters most likely to be responsive to campaign information—are partisans who disagree with their party on a policy issue they care about, like the aforementioned pro-life Democrats or pro–stem cell research Republicans. Second, candidates have a chance to attract (or at least disaffect) these persuadable voters by emphasizing the issues that are the source of internal conflict. Third, advances in information and communication technologies have encouraged the use of wedge issues by making it easier to identify who should be targeted and with what campaign messages. In the 2004 campaign, both candidates used direct mail, telephone calls, email, and personal canvassing to target different policy messages to persuadable voters on the particular wedge issues for which they were expected to be receptive.

Our theory of the persuadable voter challenges three widespread myths about contemporary American politics. First, there is a popular perception that recent presidential candidates have campaigned on divisive issues as a way to fire up their core partisan base. Political pundits and journalists commonly argued that Bush’s attention to abortion, gay marriage, and stem cell research in the 2004 campaign was an appeal to his extremist core supporters: “Instead of edging toward the middle, Bush ran hard to the right. Instead of trying to reassure uncertain moderates, he worked hard to stoke the passions of those who needed no convincing.”4 Academic works have similarly concluded that candidates will be willing to take extreme positions on controversial issues to pander to their partisan base—either because they need to win party primaries or to obtain the campaign contributions and other resources necessary to run for office.5 In contrast, we argue that divisive issues are often used to appeal to persuadable voters, often from the opposing partisan camp.

Looking back in history, there are clear examples of such wedge campaign strategies—most notably, the efforts of Republican candidates Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan to appeal to southern conservative Democrats. Indeed, political scientist E. E. Schattchneider long ago argued that the effort of all political struggles “is to exploit cracks in the opposition while attempting to consolidate one’s own side.”6 Yet such wedge strategies might seem obsolete if the electorate has polarized along partisan and ideological lines, as is generally thought to be the case today. The second myth we take on in this book is the widespread view that the polarization we observe in Washington has led to or has followed similar polarization in the electorate. The reality is that in a complex and pluralistic society, political parties are inherently coalitions of diverse individuals. The choice of only two major parties ensures that some partisans will be incongruent on some issues, thereby creating policy cleavages within the party coalitions. We argue that these cross-pressures between partisan loyalties and policy preferences have clear implications for the behavior of both voters and candidates in the campaign.

Cross-pressured partisans are willing to reassess their expected support for their party’s nominee if they come to believe that an issue about which they disagree with their party is at stake in the election. These voters might find the salience of a conflicting issue increased by real-world events or personal experiences, but a political campaign can also activate a policy disagreement by highlighting the candidates’ differences on the issue and calling attention to one’s own party’s failings and the opposition’s virtues on the issue.

Finally, the third myth that we challenge in our analysis is the enduring conventional wisdom that persuadable voters are the least admirable segment of the electorate—poorly informed and lacking in policy attitudes. The prevailing perception about the persuadable segment of the electorate is that “its level of information is low, its sense of political involvement is slight, its level of political participation is not high.”7 It is thought that these muddled voters make up their minds on the basis of nonpolicy considerations, like candidate personality, charisma, and the “guy you’d wanna drink a beer with” criteria. In contrast, our theory suggests that policy issues are often central to how persuadable voters make up their minds. To be clear, this book is not a polemical account of an American populace composed of ideal citizens highly engaged and fully informed across all policy domains. Rather, we argue simply that for those voters who find themselves at odds with their party nominee it is the campaign that often helps to determine whether partisan loyalties or issue preferences are given greater weight in their vote decision.

A Broad View: The Reciprocal Campaign

In this book, we explore the interactions between voters and candidates during contemporary presidential campaigns. We argue that there is a reciprocal relationship between candidates’ campaign strategies and voter decision making. Voter behavior cannot be fully understood without taking into account campaign information, and the behavior of candidates rests fundamentally on perceptions about what the voters care about and how they make up their minds in a campaign. Thus, our analysis is broadly motivated by two interrelated research questions: Who in the electorate can be persuaded by campaign information? What strategies do candidates use to appeal to these persuadable voters?

In answering the former question, we argue that campaign information can influence voter decision making when the factors underlying an individual’s vote decision are in conflict. The most persuadable voters in the electorate are those individuals with a foot in each candidate’s camp. A Pew Survey conducted late in the 2004 campaign, for instance, found that 76 percent of likely voters who had not yet made up their minds said they agreed with Republican George Bush on some important issues and with Democrat John Kerry on other issues.8 This group of persuadable voters includes some political Independents who are closer to the Republican candidate on some issues and the Democratic candidate on other issues, but it is primarily composed of partisans who disagree with their party on a personally important policy issue. These are the “but otherwise” Democrats and Republicans, as in the voter who is “pro-life, but otherwise Democratic” or “opposed to the Iraq War, but otherwise Republican.” These cross-pressured voters have a more difficult time deciding between the candidates, so they turn to campaign information to help decide between the competing considerations.

As highlighted by our stem cell research example, our expectations about individual-level voter behavior provide a framework for understanding candidates’ campaign strategies. As V. O. Key long ago recognized, “perceptions of the behavior of the electorate … condition, if they do not fix, the types of appeals politicians employ as they seek popular support.”9 Identifying who is persuadable and who is not helps to explain why candidates behave the way they do. The key implication of our arguments for campaign strategy is that candidates have an incentive to emphasize wedge issues to appeal to the persuadable voters in the electorate if they cannot win the election with their partisan base alone. Strategic candidates will exploit the tensions that make campaigns matter. By emphasizing the issues that are the source of internal conflict, candidates can potentially shape the vote decision of these persuadable voters.

Although candidates have always had reason to look for wedge issues to highlight during their campaigns, the contemporary information environment has made it easier to identify potential wedge issues and to target issue messages to narrow segments of the population. With a wealth of information about individual voters, candidates are increasingly able to microtarget personalized appeals on the specific issues for which each voter disagrees with the other candidate. This fragmentation of the candidates’ campaign communications leads to dog-whistle politics—targeting a message so that it can be heard only by those it is intended to reach, like the high-pitched dog whistle that can be heard by dogs but is not audible to the human ear.10 By narrowly communicating issue messages, candidates reduce the risk of alienating other voters, thereby broadening the range of issues on the campaign agenda. For instance, our analysis finds that the candidates in the 2004 presidential election staked positions on more than seventy-five different policy issues in their direct-mail communications. Thus, new information and communication technologies have changed not only how candidates communicate with voters, but also who they communicate with and what they are willing to say.

In building a theory of campaigns that attempts to explain both voter and candidate behavior, we will inevitably oversimplify the political world, make sweeping and controvertible assumptions, and gloss over the many important nuances of both candidate and voter behavior. On the candidate side, for instance, we focus on the incentives in place for candidates to microtarget wedge campaign messages, but we must recognize that candidates still devote most of their campaign efforts to “macrotargeting” on the broad issues of the day. Moreover, a candidate’s campaign strategy plans are rarely perfectly implemented. Even the best-laid plans can be derailed by a scandal or a powerful opposition attack once the campaign hits full swing.

On the voter side, we do not challenge the enduring view that the mass public generally has limited political information and incoherent ideological worldviews. But just because voters do not have constrained ideologies does not necessarily mean that they do not hold policy preferences. As Phil Converse himself wrote in his classic piece assailing the ideological capabilities of the public, “A realistic picture of political belief systems in the mass public … is not one that omits issues and policy demands completely nor one that presumes widespread ideological coherence; it is rather one that captures with some fidelity the fragmentation, narrowness, and diversity of these demands.”11 Although there are undoubtedly some ill-informed voters who “respond in random fashion to the winds of the campaign,” the heart of our argument is that some voters are persuadable not because of the absence of political preferences, but rather because of the complexity of those preferences.12 The voters’ individual patterns of political preferences (reinforcing or conflicting) shape how voters respond to political information, as well as how candidates attempt to win them over.

In exploring campaign effects and candidate strategy, we build on a diverse body of research in political psychology, political communication, voting behavior, and candidate position taking. And we evaluate our expectations about the dynamics of presidential campaigns using a wide variety of different data sources and methodological approaches—cross-sectional, longitudinal, and panel surveys, a survey experiment, a data collection of direct mail from the 2004 presidential election, historical and archival research about campaign strategy, content analysis of party platforms and campaign speeches, and personal interviews with campaign practitioners. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses; we hope our pluralistic approach offers a more comprehensive and compelling examination of campaign effects and candidate strategy. Sections of our story will span American political history, but the bulk of our empirical analysis is focused on the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections. In today’s political environment, in which election outcomes are determined by razor-thin margins and the balance of power in Washington is evenly divided, it is increasingly important to understand the nature and influence of presidential campaigns. Our perspective is that campaigns play an intermediary role between the governed and the governors, a role that fundamentally hinges on information about both the candidates and the voters. Candidates develop their issue agendas and campaign strategies on the basis of information about the voting public. The voters, in turn, select a preferred presidential candidate using information learned during the campaign. Although the translation of information between candidates and voters is neither flawless nor complete, it is the key mechanism by which elections are thought to serve a democratic function.

Contributions to Campaign Effects Research

There is perhaps no wider gulf in thinking than that between academics and political practitioners on the question of “do campaigns matter?” Campaign professionals tend to view election outcomes as singularly determined by the campaign itself, while political scholars often treat election outcomes as a foregone conclusion. Since the earliest voting behavior research, the prevailing academic perspective has been that presidential campaigns are “sound and fury signifying nothing”; it is possible to predict how people will vote and who will win the election long before the campaign even begins.13 A virtual renaissance of recent research has since offered compelling evidence that campaigns can and do shape voter behavior and election outcomes, and to that growing literature we offer a number of unique contributions.14

First, we examine not whether campaigns matter, but rather, for whom and under what conditions campaigns influence voter decision making. We identify the persuadable voters on the basis of durable attitudes and beliefs, and we show how previous definitions of swing voters that use group characteristics (e.g., Catholics or suburban women) or past or intended behavior (e.g., the “undecideds” in response to a poll) provide an incomplete picture of who is responsive to the campaign and why. Our perspective recognizes that a campaign will have little influence on some in the electorate, but for others the campaign provides critical information for selecting between two candidates, neither of whom is a perfect match to their preferences. Traditional analyses of aggregate state or national vote totals mask this variation in individual-level campaign effects.15

At the same time, in a competitive electoral environment, even this small set of persuadable voters can be decisive. The number of partisan defectors in the electorate was large enough to make the difference between the winner and loser in ten of the last fourteen presidential elections.16 In the 2004 presidential election, our analysis estimates that roughly 25 percent of the voting public were persuadable partisans (another 9 percent were persuadable Independents), clearly sufficient numbers of voters to swing victory to either candidate. Of course, not all of these voters were persuaded to vote against their party’s nominee. But our analysis estimates a campaign effect of some 2.8 million partisans switching their expected vote choice in the sixteen key battleground states of the 2004 presidential campaign. Bush’s margin of victory over Kerry in those states was just 200,000 votes.

Second, our analysis suggests that the particular issues emphasized during a presidential campaign shape who votes how and why. Much of the recent research on campaign effects has evaluated the influence of campaign volume—the number of television ads or candidate visits, the amount of media coverage, or the intensity of campaign efforts.17 Much less is known about the nature and influence of campaign content. Is it consequential, for instance, not only that Bush ran more ads than Kerry in Ohio in 2004, but also that those ads focused primarily on issues of national security? Scholars have often concluded that campaign dynamics are predictable from one campaign to the next, implying that the specific content of the campaign is largely inconsequential.18 Most prominently, it is thought that campaigns largely serve to activate and reinforce partisan attachments, bringing home any wayward partisans by Election Day. Political scientist James Campbell sums up this perspective: “Campaigns remind Democrats why they are Democrats rather than Republicans and remind Republicans why they are Republicans rather than Democrats.”19 In contrast, our analysis demonstrates that campaigns often serve to pull persuadable partisans away from their party’s nominee. And depending on the nature of campaign dialogue, conflicting predispositions might rest peacefully unnoticed in one election but be the basis for defecting in the next.

Finally, our analysis examines the impact of the campaign not only on final vote choice, but also on the process by which voters make up their mind. Classic political science research offers extensive theories about the correlates of the final vote decision, but we know much less about any dynamics in the process by which voters come to that decision. As Thomas Holbrook observes, “A political campaign must be understood to be a process that generates a product, the election outcome, and like any other process, one cannot expect to understand the process by analyzing only the product.”20 Even if we are able to accurately predict an individual’s final vote choice with long-term demographic and political characteristics, knowing if it was a bumpy ride to reach that decision helps us to evaluate the persuasiveness of campaign communication. There is a noteworthy difference between the partisan who remains a committed loyalist through the entire campaign and the one who switches back and forth between candidates or remains undecided until “coming home” on Election Day. Focusing on the dynamics of the presidential campaign, we find that persuadable partisans exposed to campaign dialogue are not only more likely to defect on Election Day, they are also more likely to change their mind over the course of the campaign and in response to campaign events. With the amount and type of movement we identify, it is clear why candidates and campaign strategists go to such lengths to reach persuadable voters.

Contributions to Campaign Strategy Research

Knowing who is responsive to campaign messages helps us understand the actions of candidates in presidential campaigns. Our view of campaign responsiveness suggests that presidential candidates should emphasize wedge issues in order to appeal to persuadable voters in the electorate. It is risky for a candidate to make a policy promise in a campaign—it might alienate voters who disagree and it can constrain position taking and policy making down the line—so candidates will avoid taking positions on issues when possible. Research has documented, for instance, that congressional candidates are less likely to talk about issues if they are in a less intense or uncompetitive campaign.21 Yet, presidential contests are always competitive. Candidates must win over persuadable voters—a candidate’s partisan base is simply not sufficient to win the White House. In 2004, for instance, self-identified Republicans composed just 35 percent of the voting public, and self-identified Democrats made up 32 percent.22 In an electoral context in which the parties are evenly divided, it is Politics 101—to beat the other candidate, you must get not only the votes of your own supporters but also a few from the other side (in the concluding chapter, we consider contexts outside U.S. presidential elections). In contrast to previous expectations that candidates will appeal to the moderate median voter with centrist policy promises, we argue that candidates try to build a winning coalition between their base supporters and subsets of the persuadable voters by activating persuadable voters on the issues on which they disagree with the other candidate. As Sam Popkin observes, “Politicians and parties do not introduce [government policy] programs to … build a consensus on what is good for America, despite pious claims to the contrary. They defend or promote obligations to renew and build constituencies, or to split the opposition.”23

It should perhaps not be surprising that presidential candidates develop their issue agendas with an eye on persuadable voters. After all, strategic candidates target all their resources—political and financial—for the greatest electoral impact. Candidates target their policy promises to the pivotal voters, just as they target their campaign spending to the pivotal states. In the 2004 presidential contest, thirty-three states received no television advertising dollars from the presidential campaigns or the national parties, while battleground states received more than $8 million, and Florida alone received $36 million.24 Candidates similarly design their policy agendas to get the biggest bang for the buck. As one consultant explained, “once we have identified how to win … [and] our voters have been defined, the campaign’s resources—money, time, effort, and most of all, message—are directed only to those voters. No effort is directed anywhere or at anyone else” (italics in original).25 More narrowly still, the campaign agendas of presidential candidates are focused on the policy preferences of persuadable voters in the most competitive states. As a 1976 campaign strategy memo for President Ford bluntly explained, “Because of our electoral college system, ‘swing voters’ in target states which we believe can be won, are the only ‘swing voters’ we should focus on. It does no good to capture 100% of the ‘swing vote’ in a state which goes to our opponent because of his overwhelming initial advantage.”26

Because taking a stand on a wedge issue runs the risk of losing voters, a candidate’s use of a wedge strategy fundamentally depends on having information about the wants and desires of the persuadable voters in the electorate. The more uncertain the candidate is about the preferences of the voters, the more ambiguous campaign appeals are likely to be. Likewise, the broader the audience to whom candidates are communicating, the more moderate the issue message. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, candidates have had more information about the electorate than ever before. By combining computerized voter registration lists—which contain a voter’s name, address, and in most states, party registration and vote history—with information from census data, consumer databases, and political polls, candidates are better able to predict whether an individual citizen will turn out and who he or she might support. Candidates can then narrowly target the issue messages most likely to resonate with the individual. In talking about the importance of information for campaign strategy, one campaign consultant explained, “I think politics has always been driven by data; it’s just that the data on the electorate was never very accurate. The reason traditional politics has been about class or race politics is because individual policy preferences could only be meaningfully categorized by class or race. Now I can differentiate between nine gradations of nose-pickers.”27 Candidates use information about the voters to target policy appeals in email, direct mail, phone calls, and so on in an effort to prime different individuals to vote on the basis of different issues. Recent research has recognized that candidates will emphasize those issues that offer them a strategic advantage, but our theoretical expectations account for variations in candidates’ policy agendas by identifying who in the electorate confers the strategic advantage and why.

In 2004, for instance, the Republican Party identified thirty different target groups—like “traditional-marriage Democrats,” “education Independents,” and “tax-cut conservative Republicans”—each of which was told that their particular issue priorities were at stake in the election.28 In their book, One Party Country, political journalists Tom Hamburger and Peter Wallsten outline the efforts of the Bush campaign to “slice away pieces” of the traditional Democratic coalition with custom-tailored messages sent to business-oriented Asians, church-going black suburbanites, second-generation Indian Americans, Orthodox Jews, and other “once-Democratic swingers.”29 One pro-Bush direct-mail piece in our analysis features a Jewish Democratic woman saying, “I remember 9/11 as if it happened yesterday. … Like most Democrats, I disagree with President Bush on a lot of issues, but he was right to act quickly and decisively after we were attacked. … I’ve always been a pro-choice Democrat, but party loyalties have no meaning when it comes to my family’s safety.”

George Bush is by no means the only presidential candidate to use wedge issues to target persuadable voters. In 1996 President Bill Clinton’s campaign “went through the average woman’s day and said, we’re going to appeal to her at every step of that day,” using policies like education to “drive a wedge between the GOP and suburban families.”30 Pollster Mark Penn explained the process by which the campaign developed Clinton’s issue agenda. Using extensive polling data, “we figured out who those [swing] voters were, everything from their sports, vacations, and lifestyles,” and then divided them into nine different groups—like “balanced-budget swing voters” or “young social conservatives.”31 Finally, they were polled about a variety of different policy proposals to see how much more likely they would be to support Clinton if he offered each proposal, allowing Clinton to then emphasize the policies with the greatest appeal among these critical swing voters.

Democratic Implications of Changing Candidate Strategies

Changes in presidential campaign strategies and tactics made possible by a hyperinformation environment have broader implications for American democracy. In the campaign, the efficiency of candidate targeting strategies has heightened political inequality by improving the ability of candidates to ignore large portions of the public—nonvoters, those committed to the opposition, and those living in uncompetitive states. Critically, the preferences of these individuals are not unknown; they are deliberately ignored. Candidates consider it a waste of effort to reach out to individuals with a low expected probability of voting for them.

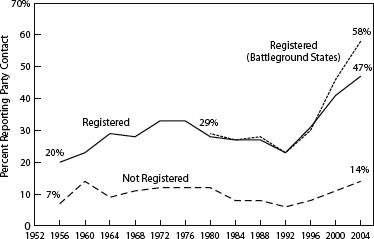

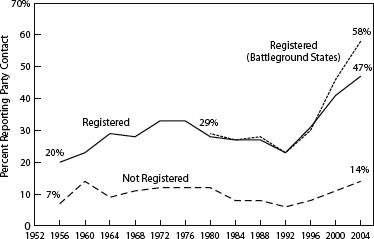

We can easily see this change in campaign strategy over time by looking at trends in self-reported campaign contact in the 1952–2004 American National Election Study (NES) cumulative file. Displayed in figure 1.1 are the percentages of respondents, by voter-registration status, reporting they were contacted by one of the political parties. By the late 1990s, corresponding with the computerization of voter registration files, the gap in party contact between those registered to vote and those not registered dramatically increased. In 2004 just 14 percent of those not registered to vote were contacted by either of the political parties, compared to 47 percent of those registered to vote, and 58 percent of registered voters in battleground states.32

Figure 1.1: Campaign Contact by Voter Registration, 1952–2004

Note: Figure illustrates increasing gap in party contact since the early 1990s. Data source is the American National Election Study cumulative file.

The fragmentation of campaign dialogue also has potential implications beyond the electoral contest itself. Elections have always been a blunt instrument for expressing the policy preferences of the public, but the multiplicity of campaign messages makes it even more difficult to evaluate whether elected representatives are following the will of the people. Microtargeting enables candidates to focus attention on the issues that will help them win, irrespective of whether they are of concern to the broader electorate. In the months leading up to the 2004 Democratic National Convention, for instance, the monthly Gallup Poll open-ended question asking about the most important problem facing the nation never once registered stem cell research in its top twenty issues.33 It is also hard to imagine that snowmobiling policy topped the public’s list of political concerns in 2006, but in the Michigan governor’s race, Republicans microtargeted working-class snow-mobilers with the message that the Democratic candidate’s environmental views stood in the way of better snowmobiling opportunities.34 Will political dialogue be consumed by “superficial politics” instead of addressing the critical issues of concern to the general public? How does a winning candidate interpret the policy directive of the electorate if different individuals intended their vote to send different policy messages? Can politicians claim a policy mandate if citizens are voting on the basis of different policy promises?

We return to these questions in the conclusion of this book, but raise them here to point out the potential ramifications of a microtargeting strategy taken to the extreme. To be sure, in many cases we are making predictions for the future rather than identifying today’s empirical reality. Microtargeting strategies continue to evolve in fits and starts as political operatives figure out issues of file management, data relevance, and analytic methods. But it is also clear that, in today’s hyperinformation environment, microtargeting is not going away. Democratic consultant Hal Malchow explains “Microtargeting is still in the early phases in politics. … It will become bigger as the campaigns start to understand it better and the data become more relevant. Then it will really reshape politics.”35 While campaign strategists and political consultants focus attention on trying to evaluate whether microtargeted appeals have some influence on the voters, in this book we consider how this campaign tactic has changed the incentives and behaviors of the candidates.

At least in the case of government policy on stem cell research, the electoral process has not yet brought stem cell policy more closely in step with current public opinion on the issue. In July 2006 Bush issued the first veto of his administration to reject the Republican Congress’s effort to expand federal funding of embryonic stem cell research, even as polls found that 68 percent of Americans support such a policy and 58 percent disapproved of his veto.36

Overview of Chapters

We cover a lot of ground in this book: voter decision making, candidate strategy, and the campaign spectacle that connects the two. We lean on a number of different theoretical perspectives, including work on information processing, attitudinal ambivalence, political persuasion, campaign strategy, and campaign effects. And we evaluate our expectations about the dynamics of presidential campaigns using a wide variety of different data sources—sample surveys, a survey experiment, a data collection of presidential direct mail, historical and archival data, and personal interviews. With this multimethod approach and broad theoretical perspective, we hope to provide a better understanding of who is responsive in presidential campaigns, why they are responsive, and how candidates attempt to sway them.

In the next chapter, we develop our theoretical arguments about how campaigns influence persuadable voters as well as how the information environment shapes the incentives that candidates face when they develop campaign strategy. We compare our expectations about campaign effects and candidate behavior with the conventional academic and popular wisdom. We argue there is an interactive flow of information and influence between candidates and voters in presidential campaigns, and cross-pressured partisans are often in the center of this reciprocal relationship.

Before turning to our analysis of campaign persuasion and candidate strategy in later chapters, we focus in chapter 3 on the fundamental issues of data, definition, and measurement. We begin the chapter with a thorough discussion of the challenges of measuring cross-pressures and an overview of the data sources used in the analysis throughout the book. We then evaluate the key assumption underlying our theoretical expectations—that there are indeed persuadable partisans in the contemporary American electorate. This chapter provides a careful examination of the contemporary policy fractures between and within the American political parties, offering a new perspective on the so-called culture wars and the surrounding debate over the degree of partisan and ideological polarization in the mass public.

Chapter 4 presents our key empirical tests of campaign persuasion by examining the way in which cross-pressures interact with the campaign environment to shape voter decision making. More broadly, this chapter addresses the question: when and how campaigns shape voter behavior. We evaluate the responsiveness of persuadable voters to campaign information in both the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections using multiple tests across multiple data sources, including a cross-sectional survey, a panel survey, and a survey experiment. This comprehensive analysis provides compelling evidence that campaigns can have measurable effects on voter decision making and these effects often serve to activate issues at the expense of partisan loyalties.

In the next two chapters, we shift our focus to more carefully consider the implications of our story for candidate strategy. In chapter 5, we offer a more detailed evaluation of our expectations about the link between voter preferences, candidate position taking, and campaign effects with an in-depth analysis of the Republican “southern strategy.” We examine the origins of this wedge-issue campaign strategy and trace its evolution and influence as it changed from an emphasis on racial wedge issues, like civil rights and busing in the late 1960s and early 1970s, to a focus on moral wedge issues, such as gay marriage and stem cell research by the turn of the century. This chapter offers an in-depth qualitative and archival analysis of candidate strategy that highlights the long-standing incentive for candidates to use wedge issues and then turns to a quantitative analysis of voter behavior to evaluate the impact of candidate strategy on voter decision making.

In chapter 6, we examine candidates’ strategies in the 2004 presidential election, focusing on the link between the information environment and candidates’ incentive to microtarget a wide range of wedge issues. Looking at the volume, content, and targeting of direct-mail and television advertising in the 2004 presidential election, we test whether candidates were primarily using controversial wedge issues in an effort to mobilize their base partisan supporters or as a tactic for influencing persuadable voters. Finally, we consider the implications of these campaign strategies for political representation and inequality.

In the final chapter, we discuss the limits of our investigations and the extent to which our theory might generalize beyond American presidential elections. We conclude with a discussion of the potentially troublesome implications of our findings for electoral accountability and democratic governance.

1 Full transcript of the speech was published by the New York Times, 27 July 2004, A1.

2 Ceci Connolly, “Kerry Takes on Issue of Embryo Research; Campaign Broadens Challenge to Include President’s Commitment to Science,” Washington Post, 8 August 2004, A5.

3 Ibid., “Stem Cell Proponents Enter Campaign Fray,” Washington Post, 26 July 2004, A11.

4 Hamburger and Wallsten, One Party Country, 138.

5 For a review of the literature see Fiorina, “Whatever Happened to the Median Voter.”

6 Schattschneider, The Semisovereign People, 67.

7 Key, The Responsible Electorate, 92.

8 “Swing Voters Slow to Decide, Still Cross-pressured,” Pew Research Center Survey Report, 27 October 2004.

9 Key, The Responsible Electorate, 7.

10 The classic example comes from the 2001 Australian federal election campaign in which Prime Minister John Howard infamously said, “We don’t want those sorts of people here,” referring to asylum seekers coming to the country on unauthorized boats.

11 Converse, “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics,” 247.

12 Key, The Responsible Electorate, 8.

13 Campbell et al., The American Voter; Fair, Predicting Presidential Elections and Other Things.

14 Most prominently, Johnston et al., The 2000 Presidential Election and the Foundations of Party Politics; Holbrook, Do Campaigns Matter?; Shaw, The Race to 270.

15 For instance, Shaw, “The Effect of TV Ads and Candidate Appearances on Statewide Presidential Votes.”

16 This estimate does not include Independents who “lean” toward one party or another. The number of ‘leaning’ and ‘pure’ Independents alone has exceeded the winners’ margin of victory in every election between 1952 and 2004, except 1964. Data source is the American National Election Study cumulative file.

17 For instance, Shaw, The Race to 270.

18 Gelman and King, “Why Are American Presidential Election Campaign Polls So Variable When Votes Are So Predictable?”

19 Campbell, “Presidential Election Campaigns and Partisanship,” 13.

20 Holbrook, Do Campaigns Matter?, 153.

21 Kahn and Kenney, The Spectacle of U.S. Senate Campaigns.

22 Including leaners increases the percentages to 46 percent Republicans and 48 percent Democrats. Data source is the 2004 National Election Study.

23 Popkin, “Public Opinion and Collective Obligations,” 2.

24 Estimates computed from data generously provided by Daron Shaw.

25 Political consultant Joel Bradshaw, “Who Will Vote for You and Why: Designing Campaign Strategy and Message,” 39.

26 Campaign Strategy Plan (drafted by White House aide Michael Raoul-Duval), August 1976; folder “Presidential Campaign—Campaign Strategy Program (1)-(3),” box 1, Dorothy E. Downton Files, Gerald R. Ford Library.

27 As quoted in Howard, New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen, 229.

28 Interview of Sara Taylor conducted by Sunshine Hillygus on 21 November 2005. The segments were calculated by state, and varied somewhat in number and content across states, depending on the type and quality of data available.

29 Hamburger and Wallsten, One Party Country, 140.

30 Rich Lowry, “Wedge Shots,” The National Review, 1 September 1997. 49 (16): 22–23.

31 Sosnik et al., Applebee’s America, 22.

32 Competitive states defined by a winning margin of 5 percentage points or less in the previous election.

33 Survey by Gallup Organization, January–October, 2004. Retrieved 22 November 2006 from the iPOLL Databank, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut.

34 Tom Hamburger and Peter Wallsten, “GOP Mines Data for Every Tiny Bloc,” Los Angeles Times, 24 September 2006, A1.

35 Telephone interview with Hal Malchow conducted by Sunshine Hillygus on 16 April 2007.

36 Survey by USA Today and Gallup Organization, 21–23 July 2006. Survey by NBC News, Wall Street Journal and Hart and McInturff Research Companies, 21–24 July 2006. Both retrieved 19 December 2006 from the iPOLL Databank, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut.