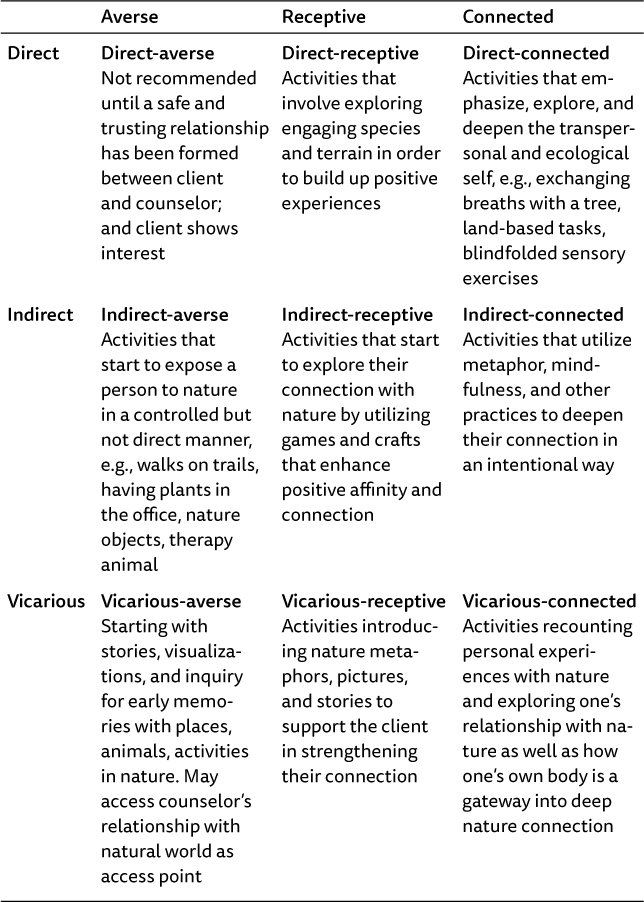

Table 1. Ecological identity and ideal clients’ modes of experiencing nature.

Formal counseling and psychotherapy traditionally takes place indoors, whether with individuals, couples, families, or groups. An office, with four walls and a closed door, provides a consistent, reliable, and contained space within which people can be comfortable knowing that their conversations and experiences will be private and they will be safe. Further, clinicians often personalize their space with comfortable furniture and inspiring messages/pictures (often of nature), and they may even have a cup of tea waiting by their client’s seat. These details enhance the client’s ease and sense that the therapeutic relationship is nurturing, attentive to their needs, and aligned with their values. Choosing to venture outside of the office walls for therapy introduces numerous novel elements into the therapeutic process requiring thoughtful consideration when determining who might benefit from this approach. As illustrated by Bob Marley’s lyrics above, the varying ways that individuals may perceive and respond to the outdoor experience (along with internal responses) need to be assessed for best practice.

As nature-based practitioners, we certainly hold biases that being in nature is more often the preferred location for our clients and ourselves. Likewise, most of the referrals we receive from the community are seeking our services specifically because of our unique approach of meeting clients outdoors. For these individuals, the four-walls approach has either failed to engage them in the past or possibly even prevented them from willingly accessing services at all. Most often, the schools, parents, or individual themselves recognize how being in relation with the natural world may be a powerful resource for their well-being. This differing perspective opens up the possibilities for novel approaches. As American philosopher David Abrams suggested in the Spell of the Sensuous, when we leave indoor built spaces, we are actually entering into more direct and unencumbered contact with nature, and thus we are in a sense moving “inside” of mother nature rather than moving to the “outside.”1 This notion flips the commonly held belief that we need to “get outside” on its head—in that case, our therapeutic approach involves helping clients go more fully “into nature.”

Despite the mounting research regarding the benefits of being in direct contact with nature, we still need to ask ourselves who thrives outside and, likewise, who may benefit more from the predictability and familiarity of an office environment. This chapter explores some important questions in order to help a practitioner in making these decisions. Further, it introduces the concept of an assessment of one’s ecological self as the foundation of our session planning, as well as an examination of the different environmental considerations for choosing the location of service.

When making the decision to head outside with clients, we often ask ourselves who will be invigorated or increasingly engaged in therapy by being in the wonders of nature versus who may need the containment and familiarity of an office setting. We have found that a combination of a client’s (1) history, motivation and interest to go outside; (2) goals for therapy; and (3) mental and physical health are the key pieces to the puzzle. We’ll explore each of these factors with examples to better illustrate how they contribute to the ecological assessment and the planning for client sessions.

The decision to take the counseling practice outside lies in the basic interest of the client—just like any other specific modality, such as art or somatic therapies. Most often, families who seek out our services have been drawn to us, or referred to us, because they have expressed an interest in the nature-based approach. Therefore, the provision of nature-based therapy is a response to that request, rather than a case of counselors suggesting to clients that meeting outdoors is a good idea.

Often a referral to our services has been made by school counselors or psychologists who know the needs of the client and suggest that being outside will help them to better engage in therapy. Parents often express that their children are happiest outdoors, thrive when they are in nature or being highly active, and struggle to focus indoors—a pretty obvious example of an ideal client and not far off the truth for many children at school. The parents have a clear sense that their children or youth would be more motivated to engage with a counselor when simultaneously engaged in activity and exploration in nature. If parents are unsure about the best approach, then we often suggest they ask the client whether they would prefer the initial meeting to occur in an office or outside.

We have also found that the motivation for seeking alternative counseling options often comes from past negative experiences with office-based services. Some examples are cases where children have shut down in therapy due to their discomfort (e.g., refusing to speak), have been unable to build a positive therapeutic relationship with the clinician, or felt that they were being put on the spot and refused to return. There are many children or youth who have difficulty making direct eye contact, to whom such intense connection feels unsafe, and for these kids, the chance to slowly build relationship while walking side by side, playing, or co-examining a wild mushroom or a slug can greatly enhance their sense of safety and ability to open up. We have found that taking these clients outdoors and introducing them to a completely different version of “therapy” can help break down barriers and build bridges. Specifically, the alternative context helps to “disguise” the counseling and turn down the volume on common misconceptions that helpers are challenged with, such as “the client as broken and needs to be fixed,” “therapist as expert,” or “therapist as the center of the process.” Counteracting these misconceptions helps reduce the stigma associated with visiting a counselor. Chapter 7 will further describe the benefits of the outdoor approach and discuss how we confront dominant narratives and stigma, and bolster alternate stories with our clients and nature as co-therapist.

An illustrative example of the positive impact of taking therapy outdoors was Justin, age 10, who had previously been through numerous forms of interventions, including individual and intensive family therapy and psychiatric assessments. He still had an unclear diagnosis of the problem. This boy was really struggling to succeed in school and relate with peers, and he had frequent meltdowns with his family, which made it difficult for them to function normally. When psychologists or psychiatrists interviewed him, his common response was to hide under chairs or inside his shirt, refusing to answer questions. Justin’s parents were desperate and worn down when they reached out for our services. After the family stated his love of animals, we agreed that a good first meeting location would be a local therapeutic farm, which was both private and contained. As Justin stepped out of the car and caught sight of the llama grazing in the field, he was immediately at ease and eager to explore the farm with his parents. He engaged directly with the therapist (Katy), asking and answering questions, and connected with the animal friends who inspired him—including cats, chickens, and even worms. At the end of the first session (just sixty minutes), Justin’s parents said this was the most they had ever witnessed him engage and open up in counseling; the sense of relief on their faces was palpable. Justin was more than eager to book another session at the farm, and over the course of therapy he was willing to explore concepts of self-regulation, boundaries, and his emotional world.

It is usually clear when someone is motivated to be outside, and we have found following their lead to be most effective. However, it is important to take their therapeutic goals into consideration. For example, if a family is needing intensive crisis support, such as developing a safety plan for their child’s extreme behaviors, being in an environment with fewer distractions may be beneficial. Likewise, if a youth who is experiencing intense social anxiety or isolating depression needs a high degree of privacy to talk about personal struggles, meeting in a quiet and controlled environment may be a better choice. Finally, if a client is experiencing psychosis, or is working on resolving relational trauma, and if taking the therapy very slowly and somatically is important, then again an office environment may be preferred, at least at first, for the containment it provides. We’ll cover the issue of client confidentiality and other ethical concerns related to protecting clients while working to maximize results through nature-based therapy in chapter 11.

It is also important to be flexible with shifting between indoor and outdoor locations as goals and needs change. Having an indoor office space available to your practice means that you can be responsive to those needs. For example, sometimes holding sessions indoors at the beginning of the counseling relationship allows for an orientation to what outdoor therapy will involve. This would be appropriate for a client who is interested but quite nervous about meeting outdoors and needs to build more safety and gather information first. Some counselors may want to initially meet with just the parents in the office for information sharing, understanding family and historical trauma, and goal setting. This introductory session also serves to orient them to what to expect in nature-based therapy, as they may be less comfortable with being outside with the play and experiential approach than the kids are themselves. It is also advantageous to have an office space available for other specific reasons throughout the course of therapy, such as case planning, parent check-ins, specific psycho-education activities involving paper and pen, or providing comfort when choosing to avoid inclement weather.

We have found that, for the majority of our clients, sessions are greatly enhanced by being outdoors. The therapeutic goals that benefit from the experiential, dynamic, flexible, numinous, inspiring, and varied qualities of wild and natural spaces are numerous. Common goals that clients seek out nature-based therapy for include improving self-esteem, self-regulation, social skills, emotional awareness, anger management, family relationships, and skills to manage anxiety and depression. Many families who choose this approach struggle with grief and loss, social isolation, school avoidance, screen addiction, ADHD labels, and the general feeling that their children do not belong, or fit into the mold required of them relative to societal expectations. Their goal is to find an approach that can help their children’s inner light shine through while enabling the child to function safely in the home, school, and community.

Throughout our years in practice, a diverse group of people have accessed our services with a range of physical and mental health needs. Following the client’s lead has been the most reliable way to assess when to head outside. We have found that there are many ways to adapt to people’s physical and mental health needs. Power To Be Adventure Therapy Society, a non-profit organization operating in Victoria, BC, has been demonstrating through their innovative programs for the past twenty years how no physical or mental health need poses too significant a barrier to overcome. For example, their programs have taken people with significant mobility issues to summits of mountains in a Trailrider (i.e., a wheelchair with one durable off-road wheel and grab bars front and back that allow for a team to drive/lift/steer the device over difficult terrain). Youth can rise to the challenge of helping a friend access that beautiful view from the mountaintop or travel together in a tandem ocean kayak with outriggers to stabilize them. The organization has spent two decades facilitating nature-based trips for almost anyone and has found ways to celebrate diversity, difference, and ability. We have taken from their inspiring approach a similar attitude and strongly believe that, with enough planning and preparation, natural spaces can be found that meet the needs of most clients. However, discerning what are real barriers that must be addressed versus self-limiting beliefs is a challenging task that requires collaboration and a detailed assessment.

Physical health concerns and adaptations: activities and locations based on physical capacity are one of the primary considerations we need to assess. Clients, be they children, youth, or families, must be able to access and safely travel in the environments we choose. Knowledge of medical conditions, physical fitness, and ability to self-motivate and stick to activities when they become difficult is important. Some youth, for example, have plenty of fitness and motivation for more challenging pursuits such as hiking steeper hills or moving through wilder terrain off-trail. The opposite is also possible: a child spending far too much time indoors, gaming and not participating in physical activities, may in fact have quite poor fitness, low motivation, and little to no staying power if the activity becomes difficult. Building a picture of client capacity has to be a conscious and documented process. As the therapist gains insight, activities can be altered to meet the client’s needs, session aims, and overall effect of nature-based therapy. An example is the basic use of progressions. A client may enjoy being at the beach. Early sessions may have started with a beach near the youth’s home. If a therapist and client agree to engage in more challenging activities, a different location, duration, and intensity of activity can be designed as needed. We are fortunate to have access to marine trails used for multi-day backpacking in our region. Some sections can become ideal places to intensify a beach session; the experience of wilder nature, the physicality of the trip, and potentially the intensity of the affective experience can all be adjusted.

Mental health considerations and adaptations: Client assessments and intake information gained through conversations with school counselors, parents, and others may educate us on previous mental health concerns that we need to plan for. Knowing about previous psychosis, a tendency to run/take off, self-harming, hallucinations, extreme anxiety (to the degree where they won’t leave the house), extreme aggression, etc. all require appropriate adaptations. As a general rule, those situations would indicate initial office-based sessions and probably family involvement. Then, through our ecological assessment and ongoing client care and communication, we would take the progressive steps toward nature-based therapy if the client was ready and interested.

An activity inspired by the work of deep ecologist, systems thinker, and Buddhist scholar Joanna Macy2 involves going swimming in a lake on a clear starry night. The idea is that, as you swim, the lake water absorbs your body while it also reflects the night sky, resulting in the boundary between your skin-encapsulated self and that of the larger cosmos starting to meld. The perception is that you no longer can sense where your body ends and the water begins. This activity is intended to provide an experience of what Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss3 describes as the ecological self: a self that is not restricted by one’s physical and mental processes but instead connected and inextricably linked to all of life. This idea of the self being larger than one’s own physical body and individual mind, and connected to all living beings, has been articulated by numerous worldviews and philosophies—more recently in the West, through the fields of systems theory and ecology, which focus on the study of the relationships between organisms rather than the organisms in isolation.4 As practicing nature-based therapists, we have found that assessing the degree to which someone describes experiencing an ecological self can assist in determining whether nature-based therapy is a fit and what activities may be most impactful.

If we are doing an intake for a child or youth client, then often this initial assessment takes place through the parents’ perspective. They usually have a strong sense of how comfortable their children are in the outdoors and whether spending time outside is a resource or a stress for them. This perspective will often influence the decision to conduct initial sessions in the outdoors or in the office. With younger children, we commonly arrange them outside, as it is within that context that parents believe their child will best engage. For example, a mother of a 11-year-old boy recently said that when she told him they were meeting a counselor, he responded with anger, but then when she added they were meeting at a familiar local park, he responded, “Well, OK then, that’s fine!”—his resistance to the idea of counseling was immediately disarmed. We often find that with older youth it is appropriate to initially meet in the office, and then we can assess their ecological identity and preferences together. An ecological identity is the manner and depth in which one connects to and engages with the natural environment.

To our knowledge, there is no formal standardized questionnaire with clinical validity measuring ecological identity. Instead, the utilization of a clinical interview to inquire into both present and early-childhood experiences and relationship with nature is most effective in providing a useful picture. This approach is not new. In fact, we have been using a series of questions influenced by Howard Clinebell’s pioneering ecopscyhology book, Ecotherapy.5 Clinebell used a series of questions to help understand client’s ecological biography, what he called one’s ecological story. More recently we have seen iterations of this approach in the work of counselors in both academic and practitioner materials. Some questions we often ask include

• What’s your favorite way to connect with nature?

• What were your favorite places to visit in nature as a child, youth, and adult?

• Where do you currently enjoy going in nature?

• How do you feel when you are in nature?

• What activities do you enjoy doing in the outdoors?

• What natural places and beings do you feel most connected with?

• How do you show your love and care for nature?

• (When appropriate) What pains you the most about the current environmental predicament?

The answers to these questions provide the practitioner with a sense of how much nature-connection the person feels, their history of time spent in nature, and levels of motivation to be in nature. We have found that the process of discussing both these early and current experiences can be a powerful intervention in its own right, opening doors to the transpersonal realm of a client’s life and sense of meaning.

Being present and fully aware of the wonders of the natural world is a particular state of being that is not always accessible. Similar to a muscle, being open and receptive requires practice in order to strengthen that state of being. Clients may have had experiences in nature that were frightening (e.g., being lost, alone, having aggressive or intimidating encounters with predators, fire, displacement, natural disasters). Perhaps they had experiences where they were uncomfortable due to environmental conditions and never felt a sense of safety and openness to the magnificence of the natural world. For many people, their social and cultural milieu may simply have not exposed them to quiet and undistracted time spent in wild spaces, such as growing up in inner cities where even outdoor play was limited by concerns for child safety. The thought of spending time outdoors without a particular activity or purpose may simply sound uninteresting, boring, or even uncomfortable or irrelevant to the client. It is our position that if people can move from an adverse or survival mode regarding their relationship to nature into a state of safety and connection, that over time their ecological self will emerge and grow stronger. The more present and connected they feel, the more receptive they will be to receiving the gifts of their relationship with the more than human natural world.

In doing ecological assessments, it can be helpful to understand a person’s current relationship with nature in three distinct ways: averse, receptive, and connected. Keeping these relationship stances in mind can guide the types of activities and locations decided on with the client. These distinctions build on the work of Canadian ecopsychologist, conservationist, and environmental educator John Scull.6 While now retired as a practicing psychologist, he still leads nature-connection walks for the Canadian Mental Health Association in the picturesque Cowichan Valley where Nevin lives. Scull described assessing clients with nature connection questions and divided them into three categories: (1) those with pre-existing negative feelings about nature (i.e., averse or phobic), (2) those with pre-existing positive feelings about nature (i.e., connected), and (3) those who had attended his nature-based sessions (which we are calling receptive). These simple designations provide a starting point for engaging clients in nature-based therapy. Scull has found that conducting the ecological assessment can be a therapeutic experience itself. He has shared case examples where clients’ engagement with the memories of earlier nature-based experiences have led to positive lifestyle and behavioral changes outside of therapy. It is our optimism in this reality—that healing can begin by even imagining or remembering positive experiences of contact with nature—that supports our encouragement for others to engage in this ecological assessment process.

These clients, with either very limited or negative experiences in nature, are concerned for their safety and feel out of place when in natural environments. They do not see the natural world as offering them anything meaningful and have no desire to change that stance. These clients may have encountered traumatic incidents that have established “wild nature” as a very negative association with their nervous system (e.g., war veterans whose trauma occurred outdoors, which may be a trigger, or in the case of sexual assault that occurred in a forest). It cannot be understated that respecting and honoring a client’s survival response is critical so that we “do no harm” in assuming what is best for the client. If we find ourselves with a nature-averse client, then an office setting is most suitable, and we would aim to understand more about their historical, cultural, and familial experiences that have led to this adverse relationship. Using our ecopsychological lens, we may discover very simple and slow ways to introduce vicarious contact with nature (described below) within the office, with the intention of uncovering new helpful resources for the client.

These clients have a neutral or positive stance toward nature. They have had limited experiences developing their relationship with the natural world but are open to exploring their connection. They may see the natural world as separate from themselves and focus on its practical uses, rather than being in relationship with or part of it. Receptive clients actually have the most potential for us to offer experiences and meaningful help. They may remain neutral about connecting with nature, or could move toward connection, and we take care to prevent negative experiences in nature that could shift them toward averse.

These clients have already developed strong connections with the natural world and recognize their own embeddedness and inextricability with nature. Connected clients may have family influences that have brought them closer to nature. They may have lived in close access to nature and already have established pastimes they love in the outdoors (e.g., nature walks, fishing, bird watching, or nature photography), which they can continue and enrich through deeper explorations.

Having an understanding of a person’s ecological identity can be useful when deciding on locations and activities being offered to explore. As Bob Marley suggested above, the rain falls on us all, but we need to recognize that not everyone will experience it the same. Meeting people where they are at is a crucial component of developing a trusting therapeutic relationship with clients. For a person with an averse stance toward nature, the counselor can utilize their own relationship with nature to serve as a vehicle for generating interest, and supporting the counseling process. In this case, the person may have an aversion or disinterest in direct physical contact with nature, so going outdoors may not be appropriate, especially to start. Stories about nature, pictures, plants, animals, windows with a view, and even the client’s own body and breath may be the focus while in an office environment. These activities can create a bridge for clients to safely start connecting to nature and provide a catalyst to head out of the office. A favorite tool we always have in our office space is a beautiful basket filled with fascinating and varied nature objects that clients can touch, hold, and draw upon for metaphor, self-expression, and comfort.

For a receptive person, nature can now be brought into the session, but rather than working overtly with the client’s relationship with nature, the practitioner lets the experience speak for itself (e.g., hiking or walking in the forest, sitting around a fire, noticing interesting plants and animals). The rationale is that the client is still discovering their connection with nature and that the best way to begin this process is to offer positive direct nature experiences that spark curiosity and motivation to continue exploring. Finally, when working with people who are already nature connected, the counselor may choose to center the client’s relationship with nature in sessions and provide opportunities to directly draw on, explore, and enhance this relationship. With all three client types (i.e., averse, receptive, connected), building relationships is the central aim: between client and nature, client and therapist, and therapist and nature. It is this triad of relationships, of equanimity in the process, that allows for nature to fully express its role as co-therapist.

Across all three of these situations, practitioners are also holding their own ecological identity at the forefront of their work. Their own nature connection, practices, and personal sense of connection are vital components of effective nature-based therapy. This inextricable connection between humans and the more-than-human world operates in the background, no matter where clients may be in their journey. Thus, we feel that all therapeutic work, whether it occurs in the office or outside, has the potential to be considered nature-based. How it looks depends on the clients’ goals and motivations, relationship with nature, sense of ecological identity, and particular environmental considerations, which we turn to next.

Stephen Kellert contributed immensely to our understanding of the vital importance for connection between humans and the natural world. In particular, he helped to elucidate the biophilia theory with Edward Wilson,7 which purports that humans have an innate drive and need to connect with nature that extends beyond our reliance on nature for our physical sustenance to include a “human craving for aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive, and even spiritual meaning and satisfaction.”8 Kellert’s in-depth research on the intersections between nature and children and youth explored how three different kinds of contact with nature, (1) direct, (2) indirect, and (3) vicarious (or symbolic), may impact developmental processes.

Direct contact is described as interactions with unmanaged natural environments that are self-maintaining and regenerative, requiring minimal or no human intervention to exist, yet that are still vulnerable to impacts by human activity. Examples include forests, wetlands, meadows, and savannah ecosystems, and a defining feature is that contact with these places often involve spontaneous and unpredictable interactions with flora and fauna. Kellert suggested that local parks, and even a backyard, could provide direct contact experiences when elements of the space are ecologically diverse or with enough diversity and a sense of coherence (i.e., the place seems to fit together naturally).

Indirect experiences of nature still involve actual physical contact but in environments that are highly reliant on human management and intervention: “Indirect experience of nature tends to be highly structured, organized, and planned; it may occur in settings such as zoos, botanical gardens, nature centers, museums, and parks.”9 These indirect experiences may include pets, plants, and other more-than-human natural elements that have been brought into human-managed environments.

Finally, vicarious or symbolic experiences of nature are those that do “not involve contact with actual living organisms or environments but, rather, with the image, representation, or metaphorical expression of nature.”10 Vicarious experience can be clearly evident or, at times, “highly stylized and obscure.”11 Examples include stories, photographs, nature guides, personal memories, artwork, and digital representations. In a child’s life, the role of teddy bears, other animals, and storybooks and movies full of animated and talking animals provide great examples of vicarious experiences with nature. While anthropomorphized, the characters presented to children are very accessible to their mind and perceptions of the world. Play therapists have long known the value of, and utilized, animal toys and figurines and nature objects to represent real-life characters and situations. As a parent, I (Nevin) learned early with my own children that harder conversations of a personal nature were facilitated more easily through their friends, Cavani the bear and Winter the snow lion. Our engagement by the vicarious means includes found objects from nature, as mentioned above, as well as nature-based stories and poetry, pictures, or film.

After thoroughly examining the research on how different types of contact with nature impact a child’s cognitive, affective, and evaluative development, Kellert concluded that “direct, often spontaneous contact with nature appears to constitute an irreplaceable core for healthy childhood growth and development.”12 Further, he commented on how the increasingly common lack of such contact may be considered an “extinction of experience” and how we are still not clear whether the corresponding increase in indirect and vicarious experiences of nature provides enough compensatory influence to offset this reality; “indirect or vicarious contact rarely offers the same degree of opportunity for experiencing challenge, adaptation, immersion, creativity, discovery, problem solving, or critical thinking as that afforded by direct encounters in the natural world.”13 Considering these points regarding the significance of direct experiences in nature, it is even more important that barriers are reduced or removed for children, youth, and their families to receiving such direct experiences. However, despite the potential benefits, not everyone is open and receptive to these wilder environments and experiences. We have found that combining knowledge of our clients’ ecological identity with Kellert’s three modes of experiencing nature can be helpful in meeting clients’ needs and supporting the growth of positive relationships with nature. Table 1 provides a baseline decision tree we use for matching our clients with nature relative to their ecological assessment.

The choice to take therapy outdoors depends on many factors, yet, as we have articulated, our bias is that much more can be gained than lost by heading outside where direct contact can occur. With that said, matching the specific environment with client needs is critical to the process. Some additional factors to consider beyond ecological identity and type of contact include level of privacy, type of terrain, proximity to natural spaces, and weather. As mentioned earlier, we live and work in a moderately sized coastal Canadian city with easy access to diverse nearby nature and wilderness settings. This affords us a variety of trails, peaks, forests, parks, lakes, beaches, and fields to choose from for our sessions. Clients can travel to these environments within minutes from their homes, schools, and work. Because clients are not required to travel to one specific office location, which may be inconvenient for them, and instead meet in a natural space near their own community, nature-based counseling can actually become more accessible to families than office-based services. Further, visiting nearby nature increases the chances that clients will continue to visit that park, trail, beach, etc. on their own time. Remote wilderness camps and programs, by contrast, do not share this beneficial outcome, in that the clients and families may never be able to revisit them. So, how does the counselor decide where to meet with clients?

We have found that most clients prefer to have their first few outdoor sessions in familiar environments, thereby increasing their comfort. For most people, finding locations for indirect experiences is preferred, including a park near their neighborhood, a favorite beach, or trail. However, an obvious ethical factor to consider in nature-based counseling is the limitations on privacy that are afforded by public outdoor spaces. Therefore, it is essential to discuss with clients beforehand regarding how to handle encounters with other people. For example, will the conversation continue or be paused if others approach? What will happen if either of you encounter someone you know? How do the clients want to respond if they do run into someone familiar who asks about what we are doing? How do the clients feel about encounters with dogs and their owners, and what if a dog comes up to visit?

By previously addressing these possible situations, the clinician is both acquiring consent and reducing potentially awkward moments. Having a plan will allow both (or all, if a family) to be prepared and have a smooth response that does not interfere with the therapeutic relationship or process. Answers to these questions can also help to guide the selection for a suitable location. If someone is afraid of dogs, then the counselor would want to offer locations where dogs are not permitted or are only allowed on leash. If the client is very concerned about privacy, is worried about running into friends, or does not want to be seen or possibly heard, then choosing a nature setting that is further from their own neighborhood, is more remote, or is on a private property would be preferable.

In one illustrative example, an 8-year-old girl and her family were seeking nature-based counseling and chose to meet at a large nature park (with many trails and fields), about fifteen minutes from their home, that was also popular with dog walkers and runners. After the initial greetings and interactive activities, the young girl said that she felt uncomfortable and that the venue was too public for her. She was quite private about her struggles and was already resistant to the idea of “having to see a counselor” in the first place. Even though other park visitors could not hear the family’s discussions, the presence of people and dogs coming and going was too much for her to feel safe. Future plans to meet were thus adjusted to more private spaces, including her own large backyard and a private farm that the counselor had permission to use. This case story demonstrates the importance of continually assessing the context and client’s consent—as the family had initially chosen the location together, but the child was able to be clear with her needs only after actually experiencing the setting firsthand.

If a family is comfortable being around others in a public space, however, then a familiar local park can be chosen; children generally prefer this because they develop a sense of connection and belonging in these spaces. Many younger children actually tend to be less aware of the presence of others and less self-conscious about being seen acting silly, showing emotions, or playing games. Another telling example involved a 10-year-old boy (and his parents) who chose to regularly meet in an oak woodland that was walkable from his school. While this park was commonly visited by neighborhood people, his familiarity with it and his love for its landscape, plants, and creatures were the motivating factors for his choice to meet there. He was not concerned about running into others and did not feel private about the fact that he met with a counselor—thus he could be fully present with the process within this public domain.

Ideally the nature-based counselor is familiar with the nearby nature locations they choose to take clients and can identify the quieter parts of the park to ensure privacy and confidentiality for most of the session. The initial greeting and check-ins may occur close to the main parking lot before traveling together to the preferred areas for exploration. Because nature often affords wide-open spaces with only birds and squirrels listening, therapeutic conversations may actually be more confidential than in an office space that has various clients coming and going in waiting rooms (and sometimes requires noise machines to create privacy). Further, we have found that nearby nature environments offer different experiences than a remote wilderness setting. Wilderness settings are certainly more conducive to privacy, unplanned encounters with animals, and the aesthetic experience of larger natural landscapes. However, based on the fact that wilderness is often harder to access, and farther away from urban centers, we do believe there is a strong case to be made for choosing nearby nature, so long as there are still opportunities for interaction with varied and unmanicured landscapes.

As previously discussed, one of the benefits of nature-based therapy for children and youth is the enhanced motivation and engagement in the counseling process. The idea of getting a midday break from school to go run in the woods, or finishing off a long day of sitting in school with a visit to the beach, can be more appealing than the idea of an office appointment with a counselor. Ideally, at the end of the first session, the child/youth should be feeling excited about the process and ask when will they be meeting next. This sense of engagement helps to form the basis of the therapeutic relationship from which change can occur. Thus, matching the terrain of the location to the interests and developmental needs of the child/youth is an important factor to consider. A mismatch in terrain selection may result in disinterest, lack of safety, or an obstacle to the therapeutic alliance.

A wilderness setting often provides a higher level of biodiversity, which is associated with a stronger beneficial effect from contact with nature, a greater chance of encountering exciting or interesting flora and fauna (e.g., birds of prey, great climbing trees, animals to track, and an abundance of easily identifiable wild edibles), and an enhanced sense of adventure when on a trail less traveled. Teenagers, for example, tend to desire and express higher risk-seeking behaviors; their need to be challenged and to find self-efficacy may be better met by a more challenging environment (e.g., more isolated, denser forest, steeper terrain). The objective risks associated with wilderness environments also need to be taken into account (e.g., farther away from medical attention, higher chance of encountering wildlife, greater risk of getting lost if clients get separated). Wilderness environments often are more difficult to access both with the time required to travel there and the availability of public transit. Taking all these points into account, we have found that most of our clients’ goals can be accomplished by working in a nearby nature environment. We also tend to stay focused on activities that do not require any specialized training or equipment. That said, to build fires, we teach clients safe knife handling and fire management skills, so these are no longer specialized and can become a regular activity when appropriate.

If it is possible to find accessible areas that offer safe scrambling opportunities (i.e., steep hiking terrain to gain a ridge or height of land), for example, that might be enough to pique the interest of a youth who is seeking adventure and exploring his boundaries/limits. Not all of the client’s goals may be achievable in one particular location, and visiting a few others over time may be needed. For example, a session may begin in a local park with lots of open space and familiarity. After meeting a few times and building trust, sessions could shift to an environment with more pockets of forest where the practitioner and client can gain an enhanced sense of wildness. Additionally, a session may take place on a private property where fires or natural shelter building is allowed and where the client will have the chance to participate in collaboratively or self-designed activities with the assurance that only invited family and wilderness creatures will be present.

Legendary Rastafarian musician Bob Marley’s words can be thought of in two ways: literal or metaphorical. We have explored the metaphorical understanding above in that we don’t know how our clients will perceive nature and the activities we facilitate, hence the need for the ecological assessment. We should also take Bob Marley’s words literally as rain happens, as does snow, wind, cold and hot temperatures, barometric pressure changes, etc. Regardless of how connected clients believe they are with nature, how they really respond to environmental conditions may also require a level of assessment. We need to remain mindful of our own familiarity and comfort/discomfort with adverse weather and environmental conditions and observe our clients’ responses. Not all will react in the same way. Although the rain can be seen as a metaphor for life’s troubles, some feel it more than others, and can potentially be triggered negatively by it, while those more able to acclimatize and demonstrate the self-care necessary for the conditions barely notice it at all.

While building relationships with our clients, we also gain increased awareness to their preferences and responses to different weather and environmental conditions. Just being a wee bit creative, one can imagine the possible metaphorical interpretations of these situations. Wind may represent instability or change; hot and cold temperatures can be challenges to self-care; winter’s early darkness can inspire bringing the family together around the fire for light and comfort. There is very little empirical research to support the role of weather and environmental conditions in therapy. However, if you read broadly across the nature writers and poets, across cultures, religions, and spirituality, you can find plenty of references to human-weather relationships. A clear example from my (Nevin) past includes the mood and tension in groups of adolescent males on wilderness expeditions when the barometric pressure drops preceding a storm. The observations, year after year, were that groups became more agitated and surly as the weather deteriorated. If you think of the properties of an oncoming storm—gloominess, darkness, instability, etc.—the group often appears to manifest these qualities, and you as counselor need to prepare activities and interventions to meet and work with the changing group and environmental climate. (This brings new meaning to climate change.) Not to generalize, nor lay any claims herein, we simply suggest therapists working outdoors need to stay present to weather and the environmental conditions when traveling with clients.

From a very simple perspective, checking the weather forecast will indicate how to prepare for a session and where to go relative to the report. If the weather looks particularly bad, we may call parents ahead of time to get a sense of how the child/parents are feeling about being out in the elements, so that we can make a decision collectively and be prepared. We have often found that clients are still up for the challenge, even when we might not have expected it. It is quite incredible how miserable it can feel to drive in the pouring rain, even for us, and then how fresh and nourishing that same rain can appear when heard and felt from beneath the canopy of giant Douglas-fir and western redcedar. It is pertinent to acknowledge that we do live in the most temperate climate in Canada. Being a nature-based therapist in Nebraska, California, or Newfoundland, will look quite different, coming with their own challenges, especially in winter. We mostly have to contend with strong rain and wind, not snowstorms and freezing temperatures, although, when there has been snow and ice, we don’t avoid the outdoors—our clients (both in individual and group settings) have been particularly excited to engage with the elements, whether building ice formations, throwing snowballs, or sliding penguin-style down a hill. Snow can actually provide many new opportunities for play and exploration, along with the unique beauty it brings to a landscape. Inclement weather such as high winds and rainstorms can also provide avenues for experiences of self-care, thriving outdoors, and, metaphorically, in dealing with life challenges and formidable forces (when appropriate). The fact that our counseling sessions with children and youth outdoors still tend to conform to the sixty-to-90-minute length means that, as long as everyone is dressed appropriately, it can be pretty manageable to maintain warmth and comfort regardless of the weather. Bringing a warm thermos of tea along with you never hurts either. See appendix B for a suggested clothing and equipment/materials list.