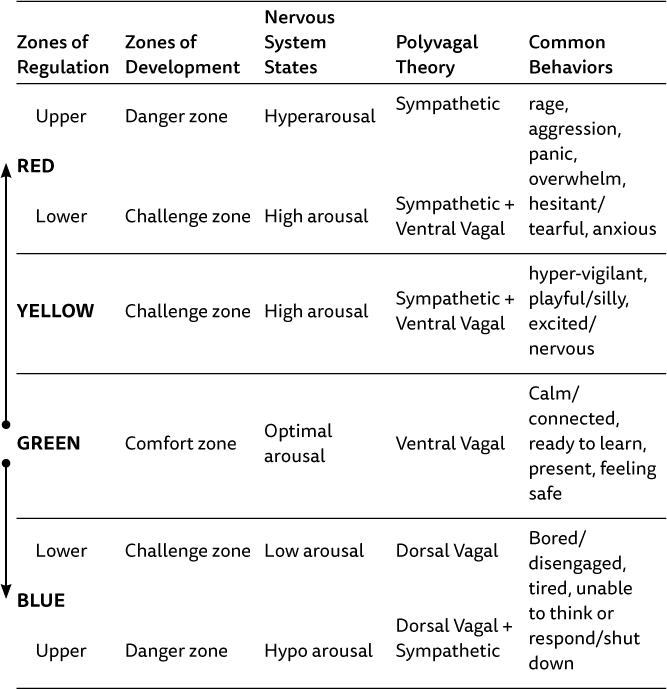

Figure 1. Porges’s polyvagal description of the autonomic nervous system

As outlined in preceding chapters, a growing body of knowledge and literature now articulates numerous positive benefits for people as a result of spending increased time in contact with nature. Physiological and psychological changes are experienced in nature and explain restored attention and decreased stress. For a practitioner of nature-based therapies, the questions of why such an approach may work and what underlying change mechanisms contribute to healing are still hard to explain. So, we ask, what else can we lay claim to as beneficial to a counselor and client relationship? Play and experiential learning are central to much of our work, and we are coming to recognize the clinical values inherent in our activities that have been practiced but not understood with any level of sophistication in the past. We can admit that experiential learning activities and play often elicit significant shifts in group and family dynamics and assist in the counseling process, yet until recently we hardly understood why. In this chapter, we lean on research and practice insights from somatic psychotherapy and advancements from neurobiology and regulation theory. Specifically, we are indebted to those who have helped translate the complex neuroscience involved in healing trauma into concrete practice applications. The task at hand is to explore the clinical application of play in nature-based therapy as it relates to self- and co-regulation, highlighting the skills and abilities needed to attend to and transform embodied information for the child, youth, or family.

We are mammals. We have mammalian nervous systems, and nature is the ideal mammalian environment. We argue that if you understand the mammalian nervous system, you too will agree that nature is the preferred place for therapy with children, youth, and families. We have found that increased knowledge of nervous system functioning provides a rich theoretical explanation of the complex connections between play, regulation, and relationships. This chapter shares how applying this knowledge in nature-based therapy provides creative and life-affirming ways to enrich your practice and improve potential client outcomes. Application of some of these concepts requires a development of skills associated with client assessment and a level of comfort in facilitating play and experiential activities. As a counselor, you may already have the capacity to design and lead sessions according to an intervention plan, based on assessment, and within your scope of practice and skills. Activities and examples of practice given here may be new to the reader yet are grounded in the same structure and processes outlined throughout the book. Utilizing novel environments and engaging in activities with unknown outcomes may be outside your comfort zone or intimidating to practice, but we encourage you to explore these approaches.

Advances in interpersonal neurobiology have brought forth a more coherent understanding of how to process difficult affective experiences, as well as the critical role interpersonal relationships have on healthy brain development and a felt sense of safety.1 The polyvagal theory, as described by Porges,2 has been particularly helpful in our clinical nature-based practice. This theory informs the differing ways clients’ cognitive processes and physical bodies are responding to the present moment, as well as what they carry forward from the past, thus influencing how they respond to stressors in the environment. Polyvagal theory also provides a rich explanation of how socially engaged play can produce transformative learning experiences.

Porges has helped to elucidate how the human autonomic nervous system impacts affect regulation and perceptions of safety, highly beneficial knowledge for therapists. According to Porges, “Evolution provides an organizing principle to identify neural circuits that promoted social behavior, and two classes of defensive strategies, mobilization associated with fighting or fleeing and immobilization associated with hiding or feigning death.”3 In more simplistic terms, the autonomic nervous system has two branches: sympathetic (S, fight/flight) and parasympathetic (P, rest/digest). However, the vagus nerve, which makes up the primary component of the parasympathetic branch, itself has two distinct components, hence the “poly” in polyvagal being dorsal vagal (DV) and ventral vagal (VV).

The VV, which has evolved more recently, is a fast-acting, highly myelinated neural web found only in mammals. It extends from the brain to the top of the diaphragm, innervating organs such as the esophagus, larynx, and lungs, communicates with facial muscles, and influences heart regulation. When the VV is activated, you can see the facial muscles engaged in authentic smiles, eyes brightening, and rhythmic relaxed breathing. It is turned on in moments of social connection, and subsequently dampens the fight/flight branch of the nervous system (i.e., aids with regulation) by slowing the heartbeat and lowering blood pressure. Porges explains that “when the ventral vagus and the associated social engagement system are optimally functioning, the autonomic nervous system supports health, growth and restoration.”4 Thus, within the counseling process, it is our aim to work with the VV nerve, the social connection system, as a pathway to aid co-regulation so clients can access and maintain regulated states during our sessions. The second component, the dorsal vagal (DV), is an evolutionarily older, unmyelinated, slower, and less nuanced component of the nervous system. It is responsible for states of deep immobilization (e.g., deep sleep, relaxation, rejuvenation), and the neural web of the DV terminates in the pelvic area and viscera/gut. When activated, it is responsible for rest and digest and is also involved in freeze responses to perceptions of life threat.

An individual can experience these neural circuits operating on their own (i.e., sympathetic arousal, VV or DV). However, Porges goes on to explain that these distinct neural circuits can also become fused together in response to contextual demands. For example, if a person is experiencing terror, and their efforts to defend themselves are ineffective (the person is unable to run away or fight), then their sympathetic branch can become paired with their DV system, and the result is a low or hypo-aroused state, with an underlayer of fear (i.e., freeze). This is the state occurring in animals when they play dead or freeze in response to threat from a predator; in humans it is often experienced as dissociation (where one’s body and mind disconnect to protect from the experience of pain).

The sympathetic arousal system can also become paired with the VV system (excitement plus connection), as is often the case when people are engaged in playful activities with others (e.g., playing tag, hiding games, team initiatives). This state of play is an activation of hyperarousal in response to a sense of adventure and risk but within the presence of social connection and safety. It is within this powerful form of play that the therapist has the ability to foster healing states of the nervous system. We have found that this task is much harder to elicit with children inside the confines of an office, and hence another reason to practice in nature. Further discussion on applying this concept appears later in the chapter.

A more nuanced understanding of the different states of the nervous system can allow practitioners to better attune to clients’ needs by becoming proficient at reading both their own and their clients’ presenting neural states. In doing so, practitioners can assist clients to (1) increase their awareness of their own somatic experience, (2) co-regulate intense affective states with the support of nature, and (3) promote healthy development by expanding their “window of tolerance.”5 This process is referred to as a two-person psychology by interpersonal neurobiologist Allan Schore, who specializes in right-brain to right-brain affect communication and regulation.6

Providing children, youth, and families with education regarding their nervous systems has been a powerful tool for us in helping them better understand their bodies’ stress responses. The process of tuning in and noticing what is happening in the body can help alleviate the intensity of an experience, promote self-compassion, and facilitate conscious actions to shift neural states. Even children as young as 6 have been taught this model and can benefit greatly from understanding how their nervous system responds to stress in their environment. This provides the children with a meta-awareness of bodily sensations and how those sensations overwhelm when they sense a lack of internal or external safety. Often tuning into one’s own embodied experience is a challenging and novel task for both children and adults alike. We have found that, by first tuning into the “outer landscape” (i.e., natural surroundings) and building rich sensory awareness of the smells, textures, colors, and animate shapes in the natural environment, we can assist clients to build the foundational skills necessary to observe their internal environment (i.e., thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations). Speaking to the importance of teaching people to tune into their senses, Kaya Lyons, Australian pediatric occupational therapist (OT) and director of Active OT for Kids, explains how “sensory pathways are faster neural pathways compared with cognitive pathways as they have direct branches to the emotional areas of the brain. Activating these sensory pathways in a calm and organized manner helps to strengthen pathways which are organizing to the body and linked to positive emotions.”7 She also offers insights from her field of OT, which recognizes that prior to thoughts and feelings are the internal senses of the body. She explains that, in addition to the commonly known five senses (sight, touch, taste, hearing, and smell), there are three internal senses: proprioception (sensations related to muscles and joints), vestibular (sensations related to balance and orientation in space), and introception (sensations related to our internal organs). Lyons claims that by “activating and organizing both external and internal senses it is possible to achieve true integration,”8 something we have experienced both personally and professionally in our work with clients. Chapter 7 describes how we teach sensory awareness skills in nature, including suggestions for games and activities.

We have developed an accessible and effective method for teaching polyvagal theory by layering these neural states over the zones of development model found in many experiential education and outdoor therapy frameworks. The model also supports the zones of regulation system, a popular framework for fostering self-regulation often taught in the school system.9 We teach this framework with children, youth, and families by laying ropes on the ground in large concentric circles, as depicted in Figure 2. These can contract and expand as needed to illustrate and explain changes in the zones depending on how one responds. For example, spending time in the challenge zone allows the comfort zone to expand, whereas spending time in the danger zone has an opposite effect.

The comfort zone (innermost ring) can represent a VV neural state. People in this zone are experiencing a sense of relative safety and comfort, and little activation is occurring. Bodily sensations often include warmth, lightness, ease, relaxation, and expansiveness. The face is relaxed and neutral in color, and smiling is common. A person in this state is calm, focused, and present with the task at hand. In the zones of regulation model, this represents the green zone, which indicates a state of readiness to learn and ability to process information.10 Examples of common activities that place kids in the comfort zone include listening to music, playing with toys, reading books in bed, being with friends, playing on the beach, exploring outside, and other favorite activities that they find easy and pleasant. It is important to note that what lies within the comfort zone is different for each person and therefore highlights the importance of being attuned to individual responses in order to move toward achieving deeper understanding. This zone is also restorative, representing situations and activities that are resources the child can turn to when under duress. A person is considered to have a regulated nervous system in this state.

In the challenge zone, sometimes called the growth/groan zone, the sympathetic neural circuit is activated. The person is experiencing a heightened state of physical activation and is considered hyper-aroused. The body is getting prepared for fight or flight in order to address the threat or challenging task. Adrenaline and cortisol pumping through the body are felt through physical sensations, often including energy or tension down the arms and legs, constriction in the chest, sweating, accelerated heart rate, and sometimes tingling in the extremeties. Breathing may be shallow and rapid; the eyes may seem like they are darting around; and the pupils may dilate (i.e., hypervigilance). These sensations are often interpreted as anxiety, nervousness, frustration, silliness, or excitement (the yellow zone, according to the zones of regulation).11 Some examples of challenge zone experiences might include writing a test, speaking in front of the class, or even getting ready for school in the morning. (Many parents can attest to the increase of stress in the home when trying to get children out the door for school.) Many physical skills and sports (biking, skiing, swimming, etc.) will pass through a period of time in the challenge zone before being considered in one’s comfort zone. Very few kids hop on a two-wheeled bike for the first time and take off without any period of nervousness or uncertainty. This state is actually an essential element in high-performance activities (e.g., musical performance, racing, team sports, rock climbing, mountain biking) as it can both energize the body and focus one’s mental state on a specific goal.

Importantly, in the challenge zone, the person is able to concurrently maintain a VV state of social connection, which keeps the sympathetic arousal of fear within manageable levels. The child may feel uncomfortable and uncertain in this state but is still able to tolerate the discomfort and ride it out toward achieving a goal. A child who is attempting to cross a log on their own has to be able to tolerate the fear of falling when the parent lets go and gives them a chance to maintain their own balance. The more that the child stands on their own feet, the less wobbly they feel, allowing for their nervous system to down regulate. After making it across, they feel success, and with repeated successes, walking across that particular log will be in their comfort zone. If they were to take those skills to a new and perhaps higher and narrower log, the familiar feelings of nervousness and excitement would likely return, and the child is back in their challenge zone, a state of potential learning and growth.

It is important to teach kids and families that if we are not willing to tolerate those sensations of nervousness, and choose instead to avoid the physical and mental discomfort completely, then we get stuck in our limited comfort zone, and it does not expand to include new experiences and skills. Such is often the case when anxiety is in charge and the child manages worry by avoiding any activities which cause uncertainty or discomfort.12 As we demonstrate these concepts visually by shrinking and expanding the comfort zone rope, we can show that, for a person who rarely leaves their comfort zone and avoids venturing into the challenge zone, their comfort zone circle will shrink over time. For some kids with high levels of anxiety, this shrinking can ultimately result in school refusal and unwillingness to leave the house. On the other hand, if they are willing to tolerate being uncertain or uncomfortable and do not shy away from new challenges, then their comfort zone will expand and grow to include many new skills, opportunities, and friendships. These kids are willing to take risks, knowing that learning from mistakes leads to growth. Many believe that the tendency toward over-protective parenting in our current culture is a contributing factor to the high levels of anxiety and depression in children and youth in North America. The desire to constantly protect our children from potential failure and injury (i.e., from challenge zone experiences) actually prevents them from discovering their own limits, skills, and strengths—and fosters fear and uncertainty rather than resilience. These situations can become feedback loops where kids are looking to their parents for signs of safety or threat and responding accordingly. If a parent’s verbal and non-verbal communication to a child is one of confidence and safety, this sends strong messages that moving forward with the task is possible. However, if a parent is unsure and anxious themselves, this can reinforce the child’s fears and lead to reassurance and avoidance patterns being strengthened.13

Finally, in the danger or panic zone, the sympathetic arousal system is engaged, hyper-aroused, without the soothing effect of a sustained VV state. This can look like rage, overwhelm, explosiveness, fear, panic, and lack of self-control (i.e., the red zone in the zones of regulation). Bodily sensations may include difficulty breathing, rapid heartbeat, pupil dilation, sweating, redness in the face, tense muscles, stomach ache, tunnel vision, and lack of bodily control (e.g., hitting, kicking, biting, spitting-fight/flight response). In this state of strong sympathetic arousal without any VV activation, the individual has in a sense “flipped their lid” as Daniel Seigel explains,14 which means they no longer can access their prefrontal cortex, and their ability to think rationally is compromised by a process of “amygdala hijacking.”15 Only once able to calm themselves down through a process of either self- or co-regulation are they able to engage in self-reflection. This process explains why kids often feel “out of control” when angry, and why we all tend to say things we don’t mean or do things we later regret. Most families who contact us for counseling support are doing so because a child or the family system as a whole is experiencing the danger zone all too often in their daily lives.

Further, if attempts are not effective to alleviate the stressor (the individual cannot fight or run away), then the sympathetic system may become paired with the DV and the drive for self-protection may immobilize them. Bodily sensations may include a numbness throughout the body or a sense of a void, stillness, and heaviness (pupil constriction, pale skin, holding their breath). The face may look devoid of affect; muscles around the eyes and mouth may have a flaccid tone; and a collapsed body posture includes the head hung low and shoulders slouched. They would now be considered in a hypo-aroused state (i.e., blue zone in the zones of regulation). This freeze state, or shutdown, can be seen in kids who are refusing to participate, will not talk, or might literally be curled up in a ball refusing to engage. This state can be triggered in situations of perceived high risk, such as a when a child freezes in fear when trying to navigate a steep section of a trail or on a climbing wall, or if they had a negative social interaction and are responding to emotions of shame. Importantly, there is a significant difference between being in a low state of arousal, where a child is seeking to up regulate to reach an optimal state, versus being in a state of shutdown. In a low state, the child is often seeking increased sensory input; in a state of shutdown, their sensory system has reached a level of capacity, and as way to cope, they close down their sensory system and are not receptive. Being aware of these different hypo-aroused states is important as they are in fact distinct neural states. In Table 2 we share our thinking on how zones of regulation, zones of development, polyvagal states and associated behaviors relate to one another.

In our use of adventure activities with groups, we introduce the zones of learning model to clients in order to emphasize that they can expect to enter the challenge zone during the program. We do want them to experience a meaningful level of challenge which can entail moments of discomfort, but we do not want them to be in the danger zone. We are constantly monitoring clients’ behavioral and emotional responses to track for signs of the danger zone, and we encourage them to notice when they may be entering that state. This is achieved by not only discussing the different states but also encouraging them to connect with their internal landscape and how their bodily sensations and emotions are responding depending on what zone they are in. This approach fosters an atmosphere of self-monitoring and personal “challenge by choice,” allowing each individual to identify and ultimately determine which zone they are experiencing for any particular activity.

Table 2. Zones of regulation, zones of development, polyvagal theory, and associated behaviors. (Adapted from the work of Stanley, Kuypers, Vygotsky, and Porges.)

One effective way to demonstrate individual differences in response to various experiences is to have a group (or family) become a living model by moving their bodies between concentric circles of rope lying on the ground that represent the zones. We call out experiences or activities and invite them to imagine what their sensory and emotional responses might be. With this felt bodily information, they can now physically locate themselves within the zones, either standing centrally in a zone or at the edges between zones. We usually start by asking about less vulnerable activities (e.g., riding a bike, swimming, kayaking, reading, cleaning your room) and then move to more internal topics (e.g., asking for help, speaking in front of the class, getting ready for school, meeting a new friend, family conflict). As the family or group moves in and out of the circles, they get the chance to learn and express themselves in a nonthreatening and nonverbal way and to observe how others have experienced the comfort, challenge, and danger zones in their lives, further normalizing their own experiences.

This activity helps participants to learn more about one another and helps the facilitator to learn about the needs and skills of the group. It helps the group see commonalities and break down barriers for connection. In families, this provides a springboard for open conversation about challenging topics. It can also be a great way for kids to start sharing their areas of difficulty in life, giving them the chance to be okay with all zones and develop resources to regulate between zones. Interestingly, most of our clients will stand inside the comfort zone when asked about playing outside in nature, which is one of the reasons we work with them in the nature-based context: it acts as a resource for maintaining connection within the therapeutic relationships. We also recognize, from a sensory perspective, nature is calming to the nervous system because it rarely overstimulates individuals as its sensory input is well balanced.

Enlisting the help of the parents to suggest activities that they know are challenging for the child can be a powerful experience. Sometimes families are surprised by what is shared, and a child also gets to learn something new about their parents. For example, one mother showed that swimming is challenging for her, but the child never knew and assumed his mother was comfortable in the pool. Now the child sees that his mother tolerates being in the challenge zone in order to do something that is fun for the child. In another instance, where a child was receiving family therapy for anxiety, a parent shared that being within a large group of people is in their challenge zone—a situation that is also an anxiety-producing experience for the child. Parent and child then had a chance for shared conversation about this worry, and it normalized the child’s struggle. So often parents keep their own personal vulnerabilities hidden from their children in an effort to protect them from adult problems, in effect alienating them in that shared experience of challenge and discomfort. Developing a common language for emotional and nervous system regulation can help families to navigate mental health issues as a team and to respond to stress with greater empathy and compassion. When a parent models persistence to their children, and can say “Hey, this was challenging for me; I was nervous, but I stuck with it anyways, and this is how I benefited,” this offers a very powerful message toward relating to discomfort as something that can be overcome versus always avoided. It also creates opportune moments to describe some resources that helped to manage the discomfort (e.g., I stopped, took a deep breath, and felt my feet on the ground, and then thought of a plan).

For people to move from their comfort zone into their challenge zone most effectively, the support and scaffolding of a caring other must be present.16 Thus, the social engagement system must be activated alongside the sympathetic system, so they can maintain their ability and receptiveness to learning in their proximal zone of development. If a practitioner is able to first notice their own state, then notice their clients’ neural states and assist them to attune to their own embodied experience, this enhanced mindfulness can lead to the possibility for more conscious choices regarding emotional states and the potential for effective change. Further, it can allow for an understanding of why their body is reacting in a certain way. This can help to facilitate self-compassion and understanding because behavioral responses make sense when put in the context of the particular neural state being activated.

Increased awareness of internal states is often not sufficient to allow for the soothing and management of intense affective experiences. Especially if there has been a history of traumatic experiences, the ability to self-regulate and prevent sliding into the danger zone is extremely challenging. Sensorimotor psychotherapy pioneer Pat Odgen and colleagues17 refer to the window of tolerance as the extent to which a person can manage difficult affect without shifting into a DV/sympathetic shutdown or hyper-aroused panic state. For a person with regulation challenges, this window would be very small, thus their challenge zone separating comfort from danger is narrow (see Table 2). Self-regulation may not be possible, but co-regulation certainly can be. Co-regulation “involves the mutual regulation of physiological states between individuals.”18 This attunement is the first task of a mother (or other attachment figure) to an infant as she responds to her baby’s cries and meets her baby’s needs for soothing/food/sleep. Thus, following an understanding of the different neural states, helping to shift someone from the danger zone back to challenge or comfort zone can be possible.

If an individual is feeling agitated, experiencing an increased heart rate and racing thoughts, they can be reminded that this is their nervous system in the challenge zone. The social connection involved in naming and discussing this state can help to engage the VV circuit, keeping the hyperarousal at a manageable level. One example of how we do this involves orienting to the physical environment, much the same way a deer orients to its environment when it leaves a forested area and enters an open field. The deer will evaluate signs of safety, risk, and life threat to determine whether it should proceed from the edge. Scanning the environment can be a soothing experience, especially when one is invited to notice aspects they find beautiful, as it helps to send internal messages of safety to their nervous system. According to Porges, “Our cognitive evaluations of risk in the environment, including identifying potentially dangerous relationships, play a secondary role to our visceral reactions to people and places.”19 Thus, the step often missed is bringing awareness to the three internal senses, mentioned above, as security comes from feeling safe in the external environment and within our internal ability to cope in our environment.20 This felt experience of safety is what is key to the co-regulation process.

An 9-year-old girl was being seen for anxiety that was affecting her behavior in school; some activating factors included getting sick during travel (e.g., in cars, boats, planes). Since car rides heightened her anxiety, she would often arrive to counseling in a hyper-aroused state. Her dysregulation was visible both in her words that expressed distress and in her body through repetitive movements in an attempt to self-soothe. She obviously was not in a state to be able to process any cognitive learning about coping skills at that time. (Attempting CBT interventions would be fruitless.) Fortunately, we met regularly in a beautiful public park with natural features including the ocean, creek, meadow, and trees all around. Thus, we learned to start sessions by walking to a grassy meadow by a pond nearby and lying down on a blanket (with her mom or dad present). The counselor started experimenting with playing the game I Spy, focusing first on colors then moving to textures (e.g., I spy something soft, spikey). Counselor, parent, and child would take turns asking questions, and the child could not help but become engaged in the game of guessing the right answer. Soon enough this girl would be happily playing I Spy, her nervous system returned to a VV state, and she was able to verbally express awareness of a shift in her internal sensations. By bringing attention to the senses in a natural setting, we were able to override the panic response and re-engage her prefrontal cortex in the process of therapy. This shift allowed us to move toward more insight-based conversations and work on skill building to manage her anxiety.

How can a person assist another to expand their window of tolerance is a central question for helping professionals. One of the most effective methods we utilize is nature-based play. The engagement possible by being in a nature setting, health and development benefits associated with play in general, and the co-regulating effect of incorporating play into sessions all contribute to positive therapeutic and health outcomes.

As described above, play is the neural state of sympathetic arousal plus social engagement. It is important to note that play in the neurological sense does not include any solitary activities (such as video games, iPad apps, or even interacting independently with toys). Instead, play involves activation of the sympathetic nervous system (i.e., the game elicits excitement, laughter, curiosity, and focus) combined with maintained social connection, which serves to keep a person in a regulated state. Further, play includes movements and gestures similar to fight/flight behaviors that are followed by face-to-face interactions. This is evident in the play behavior of almost all mammals.21

Many children and youth who seek counseling and participate in our programs struggle to maintain social connection during play. Either they are disinterested and refuse to engage, or they become hyper-aroused and the play quickly shifts to aggression, fighting, and “having to win” or, subsequently, a feeling of defeat, collapse, and giving up if they are perceiving themselves as “losing.” In both circumstances, they are not able to maintain a VV connection to help regulate their sympathetic arousal. Often these clients are described as having self-regulation challenges, along with a number of other common diagnoses such as ODD, attachment disruptions, ADHD, anxiety, autism spectrum. Sharon Stanley describes the neurobiology of play:

During play, the ventral vagal circuit of social connection helps people stay in contact with each other yet explore the edges of fear through small doses of sympathetic arousal. If the arousal of the ventral vagal circuit of social engagement trumps the arousal of the sympathetic circuit, play is successful and participants can enjoy a bond of social engagement. If the ventral vagal arousal is lost for either participant, play can feel like bullying, harassment, or even the terror of life threat. When a child perceives his or her life is threatened in this kind of play, the neural state of “immobilization with fear” can take over and the child can collapse into patterns of blame, shame, helplessness, and powerlessness.22

Being in natural settings affords people a rich environment for both unstructured and structured play that can be tailored to their unique circumstances and promote the maintenance of a VV connection. By drawing on children’s passions, such as hiding, seeking, sneaking, and exploring, we have found success in offering simple activities to engage our clients in play-based activities in nature. Because these are facilitated by an attuned helper, the child or youth is able to be supported to maintain social connection in situations that otherwise would have led to dysregulated states. Further, we can offer games of varying difficulty, depending on the goals to be achieved. If we are hoping to build a child’s confidence, then awarding points for successfully navigating challenging terrain is an effective approach. The child can earn points for climbing obstacles and finding elements in the natural environment (scavenger hunt). The VV connection is maintained through coaching and reflecting back the youth’s experience as they work through the challenges. If the goal is to help the child cultivate an inner stillness, then we include hiding games where being really quiet and camouflaged is required to succeed. We find that disguising mindfulness in nature through a game that demands stillness and observation for success is an effective approach to promote these skills in kids who would normally resist prescribed quiet time. Finally, if we are wanting to assist with the tolerance of discomfort, we may introduce a challenging game such as having to sneak quietly to retrieve an object without being heard. The child will have to work through their initial frustration that the game is not easy and navigate how to accomplish the task. Again, having face-to-face support, along with empathic connection and clear directions regarding the rhythm, pauses, and pace of the game and interaction, are key aspects in ensuring that the child is able to adequately process and maintain a prosocial stance and regulated neural state.

A 14-year-old boy was struggling with strained family relations and had difficulty sustaining peer relationships. He had a long history of refusing to work with mental health professionals; those who did have a chance to assist him described the work as extremely challenging as he was so reluctant to engage. He was willing to work with me (Dave) because my outdoor approach sounded engaging and fun. He liked the idea of exploring the forests, making fires, and doing other adventure activities, such as using a knife to carve. We decided to meet in a nearby nature setting that was forested and on private land, which allowed us access to fire making and privacy. Early in our work, I noticed he was hard to read due to minimal affect and limited facial expressions. Further, he was reluctant to engage verbally, often claiming that he didn’t trust people or like to share or interact with those he did not know well.

An activity he did enjoy immensely was playing tricks on people, such as scaring them or rough-housing in a way that often made them feel uncomfortable. Early on in our time together, a boundary was compromised with me that made it clear why these sorts of games were getting him into trouble. A game he really enjoyed playing with me was called jousting, in which we made eye contact and attempted to touch the other person with a branch (i.e., a safer version of a jousting lance). The game could be enhanced by having to balance on a log. Once a limb is touched, it is no longer a body part available to be used, and if the core of the body is touched, or you lose all four limbs, the game is over. What was immediately apparent was how quickly the game could turn from fun to discomfort for me and how my perception of him changed from a sense of safety to threat. I observed him becoming more agitated and using increasing amounts of force, despite my clear signs of unease. On one of our first occasions, he took a hard swipe at me and hit my face, causing me to cover my face and protect myself. I told him that I no longer wanted to play as I didn’t feel safe and that we needed to take a break.

After this incident, we discussed his experience of wrestling with friends. He described how very few people are willing to do this with him and that the one time someone agreed, the “play” ended up in both of them getting upset and fighting. This particular client was struggling to understand why I was not enjoying myself during the game. Further, he was unable to maintain a VV connection and keep himself regulated. His interest in this game did provide an opportunity for us to build his skills at distinguishing activities that were playful (i.e., where we maintained social engagement) and others that were perceived as threatening. Further, I was able to draw on my own relationship with him, and the trust we had built, to express how I was experiencing the “play” as unpleasant, and to help him make connections with other situations in his life where people withdraw, despite his interest in maintaining friendship. A common thought he had shared with me is that he doesn’t know why no one wants to be around him. Through the course of a number of sessions, with an agreement that I would continue playing only if I was feeling safe, we were able to continue exploring this game and provide a neural experience for him where he was able to expand his ability to maintain positive face-to-face interactions without shifting into a deregulated state. Finally, we were able to have these discussions and reparative experiences because he felt a sense of safety and interest in the different natural environment we were meeting in and he remained engaged in the nature-based activities that were being offered.

We have been asked before whether the games we offer need to be facilitated outside, and if not, what’s the role of nature. Our answer is that because we are embedded and inextricably linked with nature and occupy animal bodies, engaging in practices that awaken and align with our mammalian nervous system will have the most profound impact. So, yes, some of our activities and counseling interventions can occur in the safe and predictable walls of an indoor space. However, if we are interested in moving beyond the establishment of comfort zones, then the wild or nearby nature spaces are exactly where we want to be. As the mounting evidence from environmental psychology suggests, our human co-evolution with natural spaces has had a profound impact on the humans we are today. We prefer and are designed to be in green environments more so than built ones.23 As mentioned above, the sensory input in a natural environment is often calming to the nervous system, unlike the overstimulating input in highly manufactured environments. Thus, interventions that take place outdoors are enhanced and are able to come alive, much in the same way we see our young clients come alive when they chase each other in the forest or come across a deer skeleton on the ground. Interacting with the natural world, particularly through play involving seeking, sneaking, hiding, chasing, and exploring, gets people into their animal bodies and senses, allowing for experiences of vitality that are harder to come by in other settings.

Nature is filled with an abundance of flora and fauna that help engage people in the present moment and embodied exploration. These bring out curiosity in people and motivate a further connection with nature; some species are more rare, or have prominent characteristics; some display intriguing behaviors. Telling examples are trees that are perfect for climbing, eagles nesting or flying overhead, banana slugs crossing a trail, or the deer that are feeding and traveling through local parks and forests. Encounters with beings that can be climbed, tended, and taken in awe or wonder provide a powerful means to engage in the present moment and begin the process of acquainting them to their own nature, their own animal bodies, and specifically their mammalian nervous system.24 Ultimately, this helps to link sensory experiences with emotions and thoughts and movement toward body-mind integration.

An important consideration when working from a somatic perspective with children, youth, and families, is that there may be a history of trauma (shock or developmental) that can create significant changes in nervous system functioning and responses to stressors. Somatic experience trainers Kathy Kain and Stephen Terrell,25 experts in the physiology and treatment of developmental trauma, wrote an integrative guide to understanding and supporting circumstances where people may appear to be regulating but in fact are struggling with survival responses from past trauma. Ensuring that the context of a person’s life is taken into consideration is vital, as is equipping oneself with the appropriate training to manage responses to trauma when working with vulnerable populations in the outdoors and from a somatic perspective.

This chapter has provided a basic understanding of the mammalian nervous system and how consideration for different neural states (in both ourselves and our clients) can inform and enhance nature-based practices. These ideas are further explored in the subsequent chapters.