The study of algebra requires that you know the specific names of numbers. In this chapter, you learn about the various sets of numbers that make up the real numbers.

Natural Numbers, Whole Numbers, and Integers

The natural numbers (or counting numbers) are the numbers in the set

N = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, …}

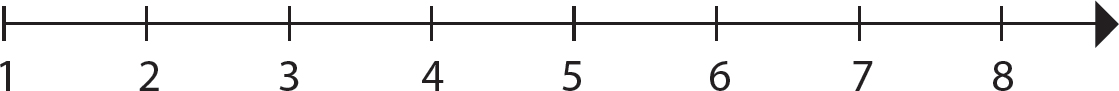

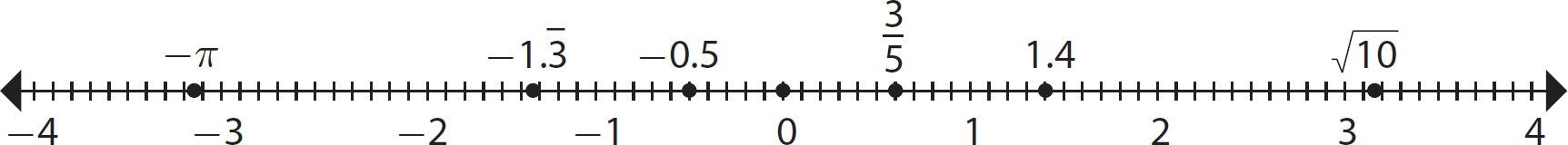

You can represent the natural numbers as equally spaced points on a number line, increasing endlessly in the direction of the arrow, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Natural numbers

The sum of any two natural numbers is also a natural number. For example, 3 + 5 = 8. Similarly, the product of any two natural numbers is also a natural number. For example, 2 × 5 = 10. However, if you subtract or divide two natural numbers, your result is not always a natural number. For instance, 8 − 5 = 3 is a natural number, but 5 − 8 is not.

Likewise, 8 ÷ 4 = 2 is a natural number, but 8 ÷ 3 is not.

When you include the number 0 with the set of natural numbers, you have the set of whole numbers:

W = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, …}

If you add or multiply any two whole numbers, your result is always a whole number, but if you subtract or divide two whole numbers, you are not guaranteed to get a whole number as the answer.

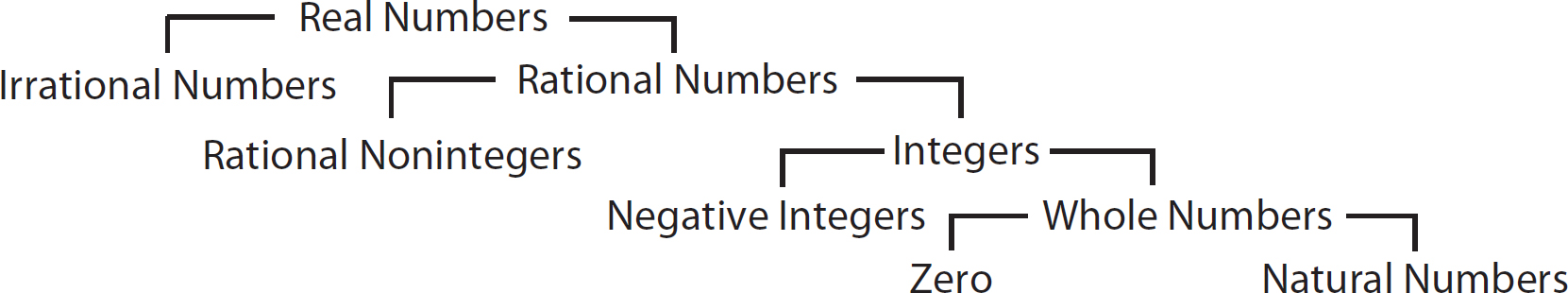

Like the natural numbers, you can represent the whole numbers as equally spaced points on a number line, increasing endlessly in the direction of the arrow, as shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Whole numbers

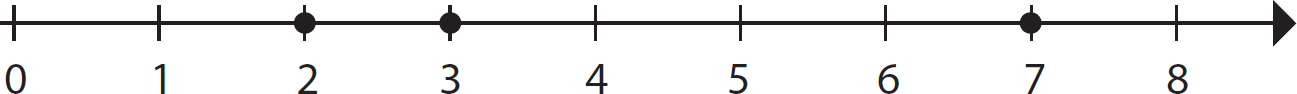

The graph of a number is the point on the number line that corresponds to the number, and the number is the coordinate of the point. You graph a set of numbers by marking a large dot at each point corresponding to one of the numbers. The graph of the numbers 2, 3, and 7 is shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Graph of 2, 3, and 7

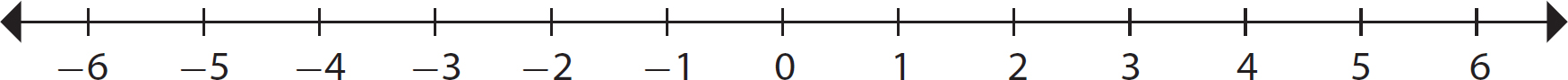

On the number line shown in Figure 1.4, the point 1 unit to the left of 0 corresponds to the number −1 (read “negative one”), the point 2 units to the left of 0 corresponds to the number −2, the point 3 units to the left of 0 corresponds to the number −3, and so on. The number −1 is the opposite of 1, −2 is the opposite of 2, −3 is the opposite of 3, and so on. The number 0 is its own opposite.

A number and its opposite are exactly the same distance from 0. For instance, 3 and −3 are opposites, and each is 3 units from 0.

Figure 1.4 Whole numbers and their opposites

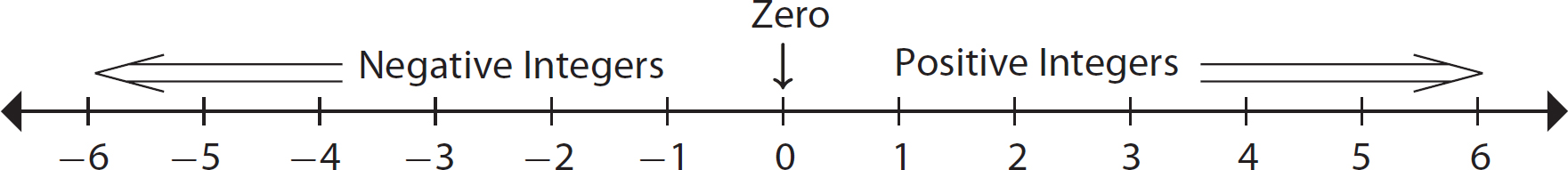

The set consisting of the whole numbers and their opposites is the set of integers (usually denoted Z):

Z = {…, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, …}

The integers are either positive (1, 2, 3, …), negative (…, −3, −2, −1), or 0.

Positive numbers are located to the right of 0 on the number line, and negative numbers are to the left of 0, as shown in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5 Integers

Problem Find the opposite of the given number.

a. 8

b. −4

Solution

a. 8

Step 1. 8 is 8 units to the right of 0. The opposite of 8 is 8 units to the left of 0.

Step 2. The number that is 8 units to the left of 0 is −8. Therefore, −8 is the opposite of 8.

b. −4

Step 1. −4 is 4 units to the left of 0. The opposite of −4 is 4 units to the right of 0.

Step 2. The number that is 4 units to the right of 0 is 4. Therefore, 4 is the opposite of −4.

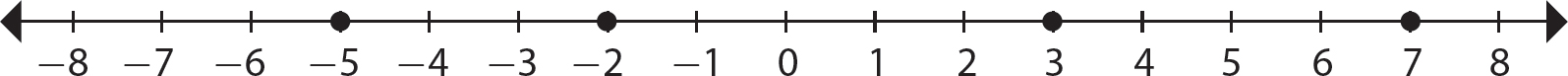

Problem Graph the integers −5, −2, 3, and 7.

Solution

Step 1. Draw a number line.

Step 2. Mark a large dot at each of the points corresponding to −5, −2, 3, and 7.

Rational, Irrational, and Real Numbers

You can add, subtract, or multiply any two integers, and your result will always be an integer, but the quotient of two integers is not always an integer. For instance, 6 ÷ 2 = 3 is an integer, but 1 ÷ 4 =  is not an integer. The number

is not an integer. The number  is an example of a rational number.

is an example of a rational number.

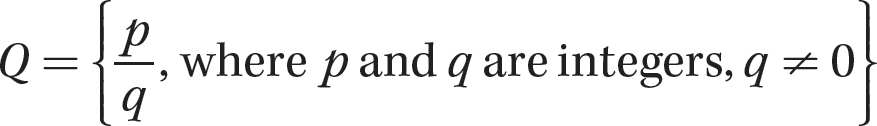

A rational number is a number that can be expressed as a quotient of an integer divided by an integer other than 0. That is, the set of rational numbers (usually denoted Q) is

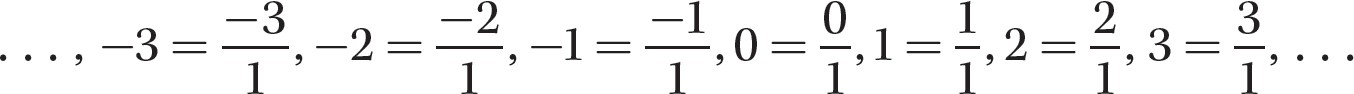

The rational numbers include positive and negative fractions, decimals, and percents. All of the natural numbers, whole numbers, and integers are rational numbers as well because each number n contained in one of these sets can be written as  , as shown here.

, as shown here.

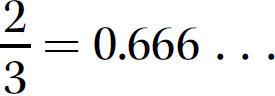

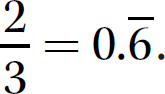

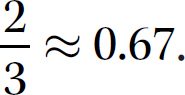

The decimal representations of rational numbers terminate or repeat. For instance,  = 0.25 is a rational number whose decimal representation terminates, and

= 0.25 is a rational number whose decimal representation terminates, and  is a rational number whose decimal representation repeats. You can show a repeating decimal by placing a line over the block of digits that repeats, like this:

is a rational number whose decimal representation repeats. You can show a repeating decimal by placing a line over the block of digits that repeats, like this:  . You also might find it convenient to round the repeating decimal to a certain number of decimal places. For instance, rounded to two decimal places,

. You also might find it convenient to round the repeating decimal to a certain number of decimal places. For instance, rounded to two decimal places,  .

.

The irrational numbers are numbers whose decimal representations neither terminate nor repeat. An irrational number cannot be expressed as the quotient of two integers. For instance, the positive number that multiplies by itself to give 2 is an irrational number called the positive square root of 2. You use the square root symbol ( ) to show the positive square root of 2 like this:

) to show the positive square root of 2 like this:  . Every positive number has two square roots: a positive square root and a negative square root. The other square root of 2 is

. Every positive number has two square roots: a positive square root and a negative square root. The other square root of 2 is  . It also is an irrational number. (See Chapter 3 for an additional discussion of square roots.)

. It also is an irrational number. (See Chapter 3 for an additional discussion of square roots.)

You cannot express  as the ratio of two integers, nor can you express it precisely in decimal form. Its decimal equivalent continues on and on without a pattern of any kind, so no matter how far you go with decimal places, you can only approximate

as the ratio of two integers, nor can you express it precisely in decimal form. Its decimal equivalent continues on and on without a pattern of any kind, so no matter how far you go with decimal places, you can only approximate  . For instance, rounded to three decimal places,

. For instance, rounded to three decimal places,  ≈ 1.414.

≈ 1.414.

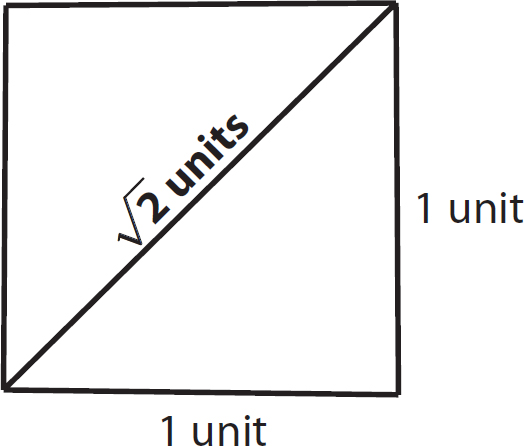

Do not be misled, however. Even though you cannot determine an exact value for  , it is a number that occurs frequently in the real world. For instance, designers and builders encounter

, it is a number that occurs frequently in the real world. For instance, designers and builders encounter  as the length of the diagonal of a square that has sides with length of 1 unit, as shown in Figure 1.6.

as the length of the diagonal of a square that has sides with length of 1 unit, as shown in Figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6 Diagonal of unit square

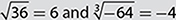

There are infinitely many other roots—square roots, cube roots, fourth roots, and so on—that are irrational. Some examples are  ,

,  , and

, and  (see Chapter 3 for a discussion of roots).

(see Chapter 3 for a discussion of roots).

Two eminently important irrational numbers are π and e. The number π is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, and the number e is used extensively in calculus. Most scientific and graphing calculators have π and e keys. To nine decimal place accuracy, π ≈ 3.141592654 and e ≈ 2.718281828.

The real numbers, R, are all the rational and irrational numbers put together. They are all the numbers on the number line (see Figure 1.7). Every point on the number line corresponds to a real number, and every real number corresponds to a point on the number line.

Figure 1.7 Real number line

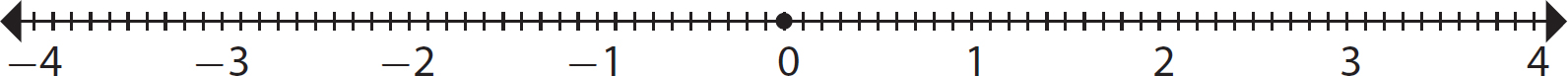

The relationship among the various sets of numbers included in the real numbers is shown in Figure 1.8.

Figure 1.8 Real numbers

Problem Categorize the given number according to its membership in the natural numbers, whole numbers, integers, rational numbers, irrational numbers, or real numbers. (State all that apply.)

a. 0

b. 0.75

c. −25

d.

e.

f.

Solution

Step 1. Recall the characteristics of the various sets of numbers that make up the real numbers.

a. 0

Step 2. Categorize 0 according to its membership in the various sets.

0 is a whole number, an integer, a rational number, and a real number.

b. 0.75

Step 2. Categorize 0.75 according to its membership in the various sets.

0.75 is a rational number and a real number.

c. −25

Step 2. Categorize −25 according to its membership in the various sets.

−25 is an integer, a rational number, and a real number.

d.

Step 2. Categorize  according to its membership in the various sets.

according to its membership in the various sets.

= 6, which is a natural number, a whole number, an integer, a rational number, and a real number.

= 6, which is a natural number, a whole number, an integer, a rational number, and a real number.

e.

Step 2. Categorize  according to its membership in the various sets.

according to its membership in the various sets.

is an irrational number and a real number.

is an irrational number and a real number.

f.

Step. Categorize  according to its membership in the various sets.

according to its membership in the various sets.

is a rational number and a real number.

is a rational number and a real number.

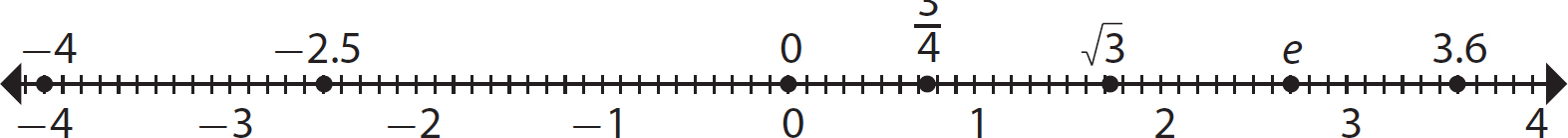

Problem Graph the real numbers −4, −2.5, 0,  ,

,  , e, and 3.6.

, e, and 3.6.

Solution

Step 1. Draw a number line.

Step 2. Mark a large dot at each of the points corresponding to −4, −2.5, 0,  ,

,  , e, and 3.6. (Use

, e, and 3.6. (Use  ≈ 1.73 and e ≈ 2.72.)

≈ 1.73 and e ≈ 2.72.)

Properties of the Real Numbers

For much of algebra, you work with the set of real numbers along with the binary operations of addition and multiplication. A binary operation is one that you do on only two numbers at a time. Addition is indicated by the + sign. You can indicate multiplication a number of ways: For any two real numbers a and b, you can show a times b as a · b, ab, a(b), (a)b, or (a)(b).

The set of real numbers has the following 11 field properties for all real numbers a, b, and c under the operations of addition and multiplication.

1. Closure Property of Addition. (a + b) is a real number. This property guarantees that the sum of any two real numbers is always a real number.

Examples

2. Closure Property of Multiplication. (a · b) is a real number. This property guarantees that the product of any two real numbers is always a real number.

Examples

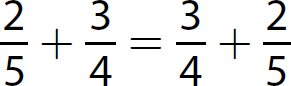

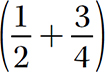

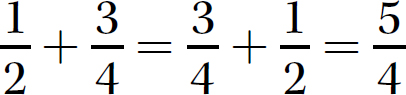

3. Commutative Property of Addition. a + b = b + a. This property allows you to reverse the order of the numbers when you add, without changing the sum.

Examples

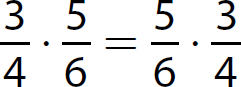

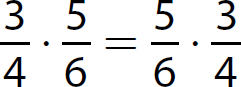

4. Commutative Property of Multiplication. a ⋅ b = b ⋅ a. This property allows you to reverse the order of the numbers when you multiply, without changing the product.

Examples

5. Associative Property of Addition. (a + b) + c = a + (b + c). This property says that when you have three numbers to add together, the final sum will be the same regardless of the way you group the numbers (two at a time) to perform the addition.

Example

Suppose you want to compute 6 + 3 + 7. In the order given, you have two ways to group the numbers for addition:

(6 + 3) + 7 = 9 + 7 = 16 or 6 + (3 + 7) = 6 + 10 = 16

Either way, 16 is the final sum.

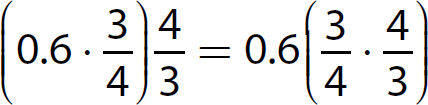

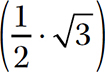

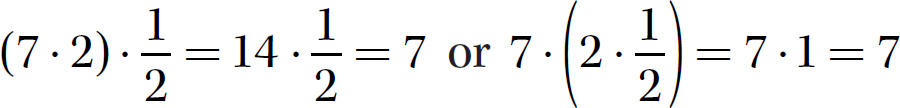

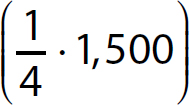

5. Associative Property of Multiplication. (ab)c = a(bc). This property says that when you have three numbers to multiply together, the final product will be the same regardless of the way you group the numbers (two at a time) to perform the multiplication.

Example

Suppose you want to compute  . In the order given, you have two ways to group the numbers for multiplication:

. In the order given, you have two ways to group the numbers for multiplication:

Either way, 7 is the final product.

7. Additive Identity Property. There exists a real number 0, called the additive identity, such that a + 0 = a and 0 + a = a. This property guarantees that you have a real number, namely, 0, for which its sum with any real number is the number itself.

Examples

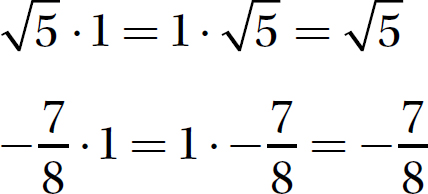

8. Multiplicative Identity Property. There exists a real number 1, called the multiplicative identity, such that a ⋅ 1 = a and 1 ⋅ a = a. This property guarantees that you have a real number, namely, 1, for which its product with any real number is the number itself.

Examples

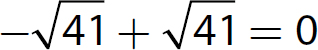

9. Additive Inverse Property. For every real number a, there is a real number called its additive inverse, denoted −a, such that a + −a = 0 and −a + a = 0. This property guarantees that every real number has an additive inverse (its opposite) that is a real number whose sum with the number is 0.

Examples

6 + −6 = −6 + 6 = 0

7.43 + −7.43 = −7.43 + 7.43 = 0

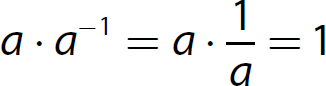

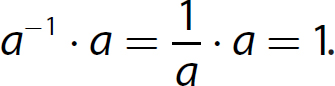

10. Multiplicative Inverse Property. For every nonzero real number a, there is a real number called its multiplicative inverse, denoted a−1 or  , such that

, such that  and

and  . This property guarantees that every real number, except zero, has a multiplicative inverse (its reciprocal) whose product with the number is 1.

. This property guarantees that every real number, except zero, has a multiplicative inverse (its reciprocal) whose product with the number is 1.

Examples

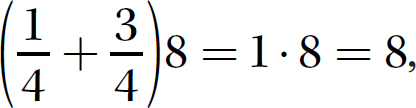

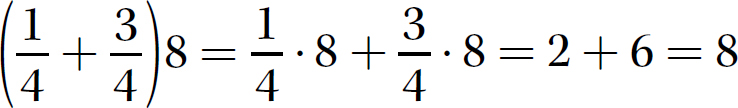

11. Distributive Property. a(b + c) = a · b + a · c and (b + c) a = b · a + c · a. This property says that when you have a number times a sum (or a sum times a number), you can either add first and then multiply, or multiply first and then add. Either way, the final answer is the same.

Examples

3(10 + 5) can be computed two ways:

add first and then multiply to obtain 3(10 + 5) = 3 ⋅ 15 = 45, or

multiply first and then add to obtain 3(10 + 5) = 3 ⋅ 10 + 3 ⋅ 5 = 30 + 15 = 45

Either way, the answer is 45.

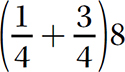

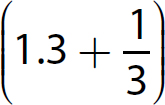

can be computed two ways:

can be computed two ways:

add first and then multiply to obtain  , or multiply first

, or multiply first

and then add to obtain

Either way, the answer is 8.

Problem State the field property that is illustrated in each of the following.

a. 0 + 1.25 = 1.25

b. (π +  ) ∈ real numbers

) ∈ real numbers

c.

Solution

Step 1. Recall the 11 field properties: closure property of addition, closure property of multiplication, commutative property of addition, commutative property of multiplication, associative property of addition, associative property of multiplication, additive identity property, multiplicative identity property, additive inverse property, multiplicative inverse property, and distributive property.

a. 0 + 1.25 = 1.25

Step 2. Identify the property illustrated.

Additive identity property

b. (π +  ) ∈ real numbers

) ∈ real numbers

Step 2. Identify the property illustrated.

Closure property of addition

c.

Step 2. Identify the property illustrated.

Commutative property of multiplication

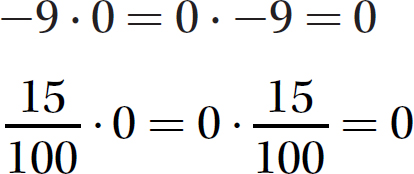

Besides the field properties, you should keep in mind that the number 0 has the following unique characteristic.

12. Zero Factor Property. If a real number is multiplied by 0, the product is 0 (i.e., a ⋅ 0 = 0 ⋅ a = 0); and if the product of two numbers is 0, then at least one of the numbers is 0.

Examples

Exercise 1

For 1–10, list all the sets in the real number system to which the given number belongs. (State all that apply.)

1. 10

4. −π

5. −1,000

9. 1

For 11–20, state the property of the real numbers that is illustrated.

11.  ∈ real number

∈ real number

14.  is a real number

is a real number

15. 43 + (7 + 25) = (43 + 7) + 25

16. 60(10 + 3) = 600 + 180 = 780

18. −999 · 0 = 0

20. (90.75)(1) = 90.75

because division by 0 is undefined, so

because division by 0 is undefined, so  has no meaning, no matter what number you put in the place of p.

has no meaning, no matter what number you put in the place of p. are rational numbers.

are rational numbers. of negative numbers are not real numbers.

of negative numbers are not real numbers. for π, π does not equal either of these numbers. The numbers 3.14 and

for π, π does not equal either of these numbers. The numbers 3.14 and