SHOPPING STREETS AND NEIGHBORHOODS

Map: B&Bs & Restaurants South of the City Center

ROUTE TIPS FOR DRIVERS HEADING SOUTH

Edinburgh is the historical, cultural, and political capital of Scotland. For nearly a thousand years, Scotland’s kings, parliaments, writers, thinkers, and bankers have called Edinburgh home. Today, it remains Scotland’s most sophisticated city.

Edinburgh (ED’n-burah—only tourists pronounce it like “Pittsburgh”) is Scotland’s showpiece and one of Europe’s most entertaining cities. It’s a place of stunning vistas—nestled among craggy bluffs and studded with a prickly skyline of spires, towers, domes, and steeples. Proud statues of famous Scots dot the urban landscape. The buildings are a harmonious yellow-gray, all built from the same local sandstone.

Culturally, Edinburgh has always been the place where Lowland culture (urban and English) met Highland style (rustic and Gaelic). Tourists will find no end of traditional Scottish clichés: whisky tastings, kilt shops, bagpipe-playing buskers, and gimmicky tours featuring Scotland’s bloody history and ghost stories.

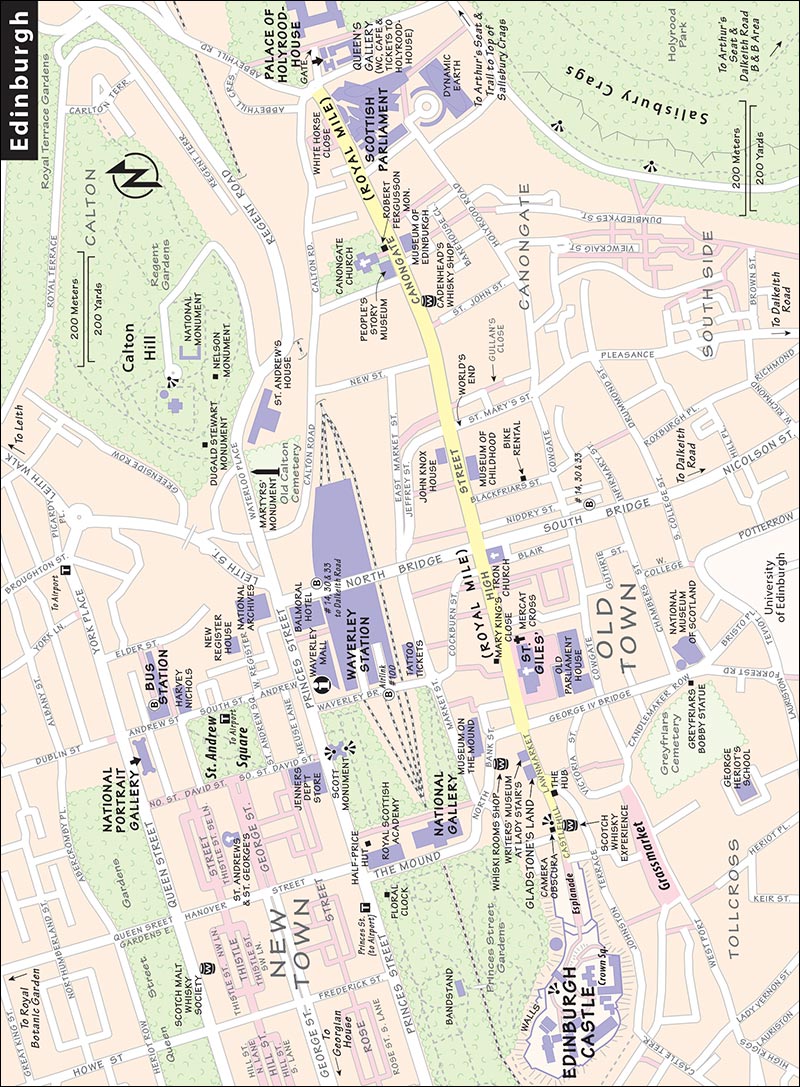

Edinburgh is two cities in one. The Old Town stretches along the Royal Mile, from the grand castle on top to the palace on the bottom. Along this colorful labyrinth of cobbled streets and narrow lanes, medieval skyscrapers stand shoulder to shoulder, hiding peaceful courtyards.

A few hundred yards north of the Old Town lies the New Town. It’s a magnificent planned neighborhood (from the 1700s). Here, you’ll enjoy upscale shops, broad boulevards, straight streets, square squares, circular circuses, and Georgian mansions decked out in Greek-style columns and statues.

Today’s Edinburgh is big in banking, scientific research, and scholarship at its four universities. Since 1999, when Scotland regained a measure of self-rule, Edinburgh reassumed its place as home of the Scottish Parliament. The city hums with life. Students and professionals pack the pubs and art galleries. It’s especially lively in August, when the Edinburgh Festival takes over the town. Historic, monumental, fun, and well organized, Edinburgh is a tourist’s delight.

While the major sights can be seen in a day, I’d give Edinburgh two days and three nights.

Day 1: Tour the castle, then consider catching a city bus tour for a one-hour loop (departing from a block below the castle at the Hub/Tolbooth Church; you could munch a sandwich from the top deck if you’re into multitasking). Back near the castle, take my self-guided Royal Mile walk, stopping in at shops and museums that interest you (Gladstone’s Land is tops but you can only visit it by booking a tour). At the bottom of the Mile, consider visiting the Scottish Parliament, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, or both. If the weather’s good, you could hike back to your B&B along the Salisbury Crags.

Day 2: Visit the National Museum of Scotland. After lunch (several great choices nearby, on Forrest Road), stroll through the Princes Street Gardens and the Scottish National Gallery. Then follow my self-guided walk through the New Town, visiting the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and the Georgian House—or squeeze in a quick tour of the good ship Britannia (check last entry time before you head out).

Evenings: Options include various “haunted Edinburgh” walks, literary pub crawls, or live music in pubs. Sadly, full-blown traditional folk performances are just about extinct, surviving only in excruciatingly schmaltzy variety shows put on for tour-bus groups. Perhaps the most authentic evening out is just settling down in a pub to sample the whisky and local beers while meeting the locals...and attempting to understand them through their thick Scottish accents (see “Nightlife in Edinburgh,” here).

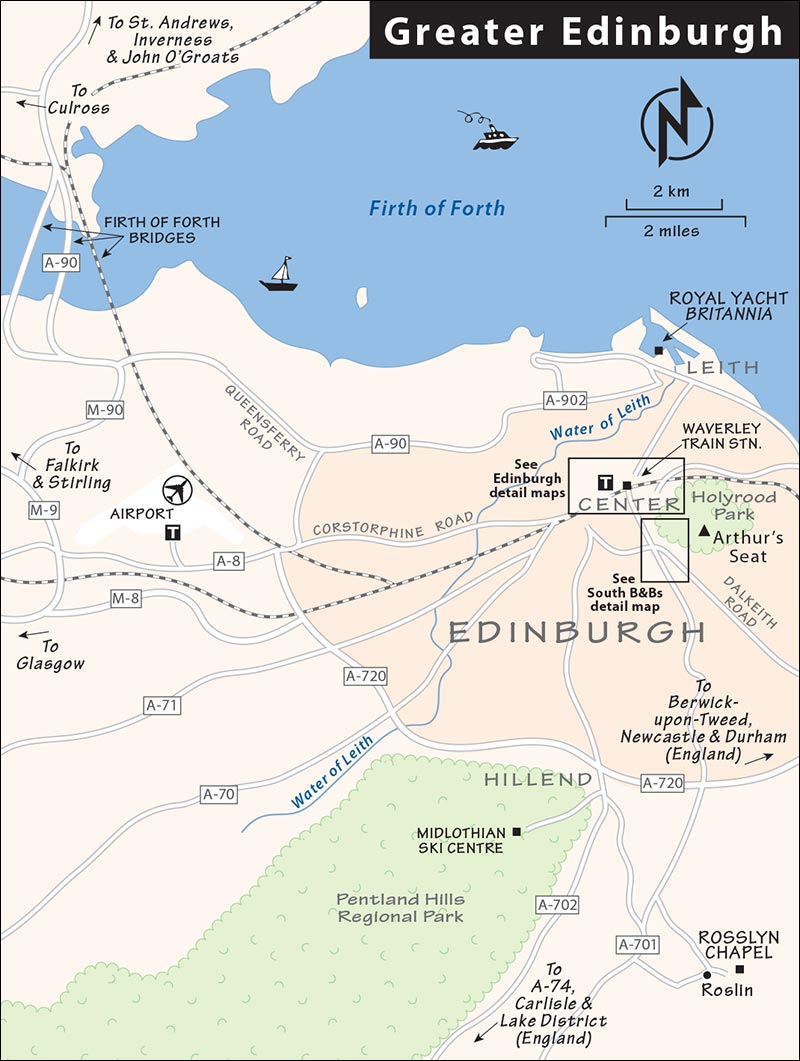

With 490,000 people (835,000 in the metro area), Edinburgh is Scotland’s second-biggest city (after Glasgow). But the tourist’s Edinburgh is compact: Old Town, New Town, and the B&B area south of the city center.

Edinburgh’s Old Town stretches across a ridgeline slung between two bluffs. From west to east, this “Royal Mile” runs from the Castle Rock—which is visible from anywhere—to the base of the 822-foot extinct volcano called Arthur’s Seat. For visitors, this east-west axis is the center of the action. Just south of the Royal Mile are the university and the National Museum of Scotland; farther to the south is a handy B&B neighborhood that lines up along Dalkeith Road and Mayfield Gardens. North of the Royal Mile ridge is the New Town, a neighborhood of grid-planned streets and elegant Georgian buildings.

In the center of it all—in a drained lake bed between the Old and New Towns—sit the Princes Street Gardens park and Waverley Bridge, where you’ll find the Waverley train station, TI, Waverley Mall, bus info office (starting point for most city bus tours), Scottish National Gallery, and a covered dance-and-music pavilion.

The crowded TI is as central as can be, on the rooftop of the Waverley Mall and Waverley train station (Mon-Sat 9:00-17:00, Sun from 10:00, June daily until 18:00, July-Aug daily until 19:00; tel. 0131-473-3868, www.visitscotland.com). While the staff is helpful, be warned that much of their information is skewed by tourism payola (and booking seats on bus tours seems to be a big priority). There’s also a TI at the airport (tel. 0131-344-3120).

For more information than what’s included in the TI’s free map, buy the excellent Collins Discovering Edinburgh map (which comes with opinionated commentary and locates almost every major sight). If you’re interested in evening music, ask for the comprehensive entertainment listing, The List. Also consider buying Historic Scotland’s Explorer Pass, which can save you some money if you visit the castles at both Edinburgh and Stirling, or are also visiting the Orkney Islands (for details, see here).

By Train: Arriving by train at Waverley Station puts you in the city center and below the TI. Taxis line up outside, on Market Street or Waverley Bridge. For the TI or bus stop, follow signs for Princes Street and ride up several escalators. From here, the TI is to your left, and the city bus stop is two blocks to your right (for bus directions from here to my recommended B&Bs, see “Sleeping in Edinburgh,” later).

By Bus: Scottish Citylink, Megabus, and National Express buses use the bus station (with luggage lockers) in the New Town, two blocks north of the train station on St. Andrew Square.

By Car: If you’re arriving from the north, rather than drive through downtown Edinburgh to my recommended B&Bs, circle the city on the A-720 City Bypass road. Approaching Edinburgh on the M-9, take the M-8 (direction: Glasgow) and quickly get onto the A-720 City Bypass (direction: Edinburgh South). After four miles, you’ll hit a roundabout. Ignore signs directing you into Edinburgh North and stay on the A-720 for 10 more miles to the next and last roundabout, named Sheriffhall. Exit the roundabout at the first left (A-7 Edinburgh). From here it’s four miles to the B&B neighborhood. After a while, the A-7 becomes Dalkeith Road (you’ll pass the Royal Infirmary hospital complex). If you see the huge Royal Commonwealth Pool, you’ve gone a couple of blocks too far (avoid this by referring to the map on here).

If you’re driving in on the A-68 from the south, first follow signs for Edinburgh South & West (A-720), then exit at A-7(N)/Edinburgh and follow the directions above.

By Plane: Edinburgh’s airport is eight miles and a 25-minute taxi ride from downtown. For information, see “Edinburgh Connections,” at the end of this chapter.

Sunday Activities: Many Royal Mile sights close on Sunday (except in Aug), but other major sights and shops are open. Sunday is a good day to catch a guided walking tour along the Royal Mile or a city bus tour (buses go faster in light traffic). The slopes of Arthur’s Seat are lively with hikers and picnickers on weekends.

Festivals: August is a crowded, popular month to visit Edinburgh thanks to the multiple festivals hosted here, including the official Edinburgh International Festival, the Fringe Festival, and the Military Tattoo. Book ahead for hotels, events, and restaurant dinners if you’ll be visiting in August, and expect to pay significantly more for your room. Many museums and shops have extended hours in August. For more festival details, see here.

Baggage Storage: At the train station, you’ll find pricey, high-security luggage storage near platform 2 (daily 7:00-23:00). There are also lockers at the bus station on St. Andrew Square, just two blocks north of the train station.

Laundry: The Ace Cleaning Centre launderette is located near my recommended B&Bs south of town. You can pay for full-service laundry (drop off in the morning for same-day service) or stay and do it yourself. For a small extra fee, they’ll collect your laundry from your B&B and drop it off the next day (Mon-Fri 8:00-20:00, Sat 9:00-17:00, Sun 10:00-16:00, along bus route to city center at 13 South Clerk Street, opposite Queens Hall, tel. 0131/667-0549).

Bike Rental and Tours: The laid-back crew at Cycle Scotland happily recommends good bike routes with your rental (prices starting at £20/3 hours or £30/day, electric bikes available for extra fee, daily 10:00-18:00, may close for a couple of months in winter, just off Royal Mile at 29 Blackfriars Street, tel. 0131/556-5560, mobile 07796-886-899, www.cyclescotland.co.uk, Peter). They also run guided three-hour bike tours daily at 11:00 that start on the Royal Mile and ride through Holyrood Park, Arthur’s Seat, Duddingston Village, Doctor Neil’s (Secret) Garden, and along the Innocent railway path (£45/person, extra fee for e-bike, book ahead).

Car Rental: These places have offices both in the town center and at the airport: Avis (24 East London Street, tel. 0844-544-6059, airport tel. 0844-544-6004), Europcar (Waverley Station, near platform 2, tel. 0871-384-3453, airport tel. 0871-384-3406), Hertz (10 Picardy Place, tel. 0843-309-3026, airport tel. 0843-309-3025), and Budget (24 East London Street, tel. 0844-544-9064, airport tel. 0844-544-4605). Some downtown offices close or have reduced hours on Sunday, but the airport locations tend to be open daily. If you plan to rent a car, pick it up on your way out of Edinburgh—you won’t need it in town.

Dress for the Weather: Weather blows in and out—bring your sweater and be prepared for rain.

Many of Edinburgh’s sights are within walking distance of one another, but buses come in handy—especially if you’re staying at a B&B south of the city center. Double-decker buses come with fine views upstairs. It’s easy once you get the hang of it: Buses come by frequently (screens at bus stops show wait times) and have free, fast Wi-Fi on board. The only hassle is that you must pay with exact change (£1.60/ride, £4/all-day pass). As you board, tell your driver where you’re going (or just say “single ticket”) and drop your change into the box. Ping the bell as you near your stop. You can pick up a route map at the TI or at the transit office at the Old Town end of Waverley Bridge (tel. 0131/555-6363, www.lothianbuses.com). Edinburgh’s single tram line (also £1.60/ride) is designed more for locals than tourists; it’s most useful for reaching the airport (see “Edinburgh Connections” at the end of this chapter).

The 1,300 taxis cruising Edinburgh’s streets are easy to flag down (ride between downtown and the B&B neighborhood costs about £7; rates go up after 18:00 and on weekends). They can turn on a dime, so hail them in either direction. Uber also works well here.

Walking tours are an Edinburgh specialty; you’ll see groups trailing entertaining guides all over town. Below I’ve listed good all-purpose walks; for literary pub crawls and ghost tours, see “Nightlife in Edinburgh” on here.

Edinburgh Tour Guides offers a good historical walk (without all the ghosts and goblins). Their Royal Mile tour is a gentle two-hour downhill stroll from the castle to the palace (£16.50; daily at 9:30 and 19:00; meet outside Gladstone’s Land, near the top of the Royal Mile—see map on here, must reserve ahead, mobile 0785-888-0072, www.edinburghtourguides.com, info@edinburghtourguides.com).

Mercat Tours offers a 1.5-hour “Secrets of the Royal Mile” walk that’s more entertaining than intellectual (£13; £30 includes optional, 45-minute guided Edinburgh Castle visit; daily at 10:00 and 13:00, leaves from Mercat Cross on the Royal Mile, tel. 0131/225-5445, www.mercattours.com). The guides, who enjoy making a short story long, ignore the big sights and take you behind the scenes with piles of barely historical gossip, bully-pulpit Scottish pride, and fun but forgettable trivia. They also offer other tours, such as ghost walks, tours of 18th-century underground vaults on the southern slope of the Royal Mile, and Outlander sights (see their website for a rundown).

Sandemans New Edinburgh runs “free” tours multiple times a day; you won’t pay upfront, but the guide will expect a tip (check schedule online, 3 hours, meet in front of Starbucks by Tron Kirk on High Street, www.neweuropetours.eu).

The Voluntary Guides Association offers free two-hour walks, but only during the Edinburgh Festival. You don’t need a reservation—just show up (check website for times, generally depart from City Chambers across from St. Giles’ Cathedral on the Royal Mile, www.edinburghfestivalguides.org). You can also hire their guides (for a small fee) for private tours outside of festival time.

The following guides charge similar prices and offer half-day and full-day tours: Jean Blair (a delightful teacher and guide, £190/day without car, £430/day with car, mobile 0798-957-0287, www.travelthroughscotland.com, scotguide7@gmail.com); Sergio La Spina (an Argentinean who adopted Edinburgh as his hometown more than 20 years ago, £250/day, tel. 0131/664-1731, mobile 0797-330-6579, www.vivaescocia.com, sergiolaspina@aol.com); Ken Hanley (who wears his kilt as if pants don’t exist, £130/half-day, £250/day, extra charge if he uses his car—seats up to six, tel. 0131/666-1944, mobile 0771-034-2044, www.small-world-tours.co.uk, kennethhanley@me.com); and Liz Everett (walking tours only—no car; £165/half-day, £230/day, mobile 07821-683-837, liz.everett@live.co.uk).

The following one-hour hop-on, hop-off bus tour routes, all run by the same company, circle the town center, stopping at the major sights. Edinburgh Tour (green buses) focuses on the city center, with live guides. City Sightseeing (red buses, focuses on Old Town) has recorded commentary, as does the Majestic Tour (blue-and-yellow buses, includes a stop at the Britannia and Royal Botanic Garden). You can pay for just one tour (£15/24 hours), but most people pay a few pounds more for a ticket covering all buses (£20; buses run April-Oct roughly 9:00-19:00, shorter hours off-season; every 10-15 minutes, buy tickets on board, tel. 0131/220-0770, www.edinburghtour.com). On sunny days the buses go topless, but come with increased traffic noise and exhaust fumes. For £52, the Royal Edinburgh Ticket covers two days of unlimited travel on all three buses, as well as admission (and line-skipping privileges) at Edinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, and Britannia (www.royaledinburghticket.co.uk).

The 3 Bridges Tour combines a hop-on, hop-off bus to South Queensferry with a boat tour on the Firth of Forth (£20, 3 hours total).

Andy Steves (Rick’s son) runs Weekend Student Adventures (WSA Europe), offering 3-day and 10-day budget travel packages across Europe including accommodations, skip-the-line sightseeing, and unique local experiences. Locally guided and DIY options are available for student and budget travelers in 13 of Europe’s most popular cities, including Edinburgh (guided trips from €199, see www.wsaeurope.com for details). Check out Andy’s tips, resources, and podcast at www.andysteves.com.

Many companies run a variety of day trips to regional sights, as well as multiday and themed itineraries. (Several of the local guides listed earlier have cars, too.)

The most popular tour is the all-day Highlands trip. The standard Highlands tour gives those with limited time a chance to experience the wonders of Scotland’s wild and legend-soaked Highlands in a single long day (about £50, roughly 8:00-20:00). Itineraries vary but you’ll generally visit/pass through the Trossachs, Rannoch Moor, Glencoe, Fort William, Fort Augustus on Loch Ness (some tours offer an optional boat ride), and Pitlochry. To save time, look for a tour that gives you a short glimpse of Loch Ness rather than driving its entire length or doing a boat trip. (Once you’ve seen a little of it, you’ve seen it all.)

Larger outfits, typically using bigger buses, include Timberbush Highland Tours (tel. 0131/226-6066, www.timberbushtours.com), Gray Line (tel. 0131/555-5558, www.graylinescotland.com), Highland Experience (tel. 0131/226-1414, www.highlandexperience.com), Highland Explorer (tel. 0131/558-3738, www.highlandexplorertours.com), and Scotline (tel. 0131/557-0162, www.scotlinetours.co.uk). Other companies pride themselves on keeping group sizes small, with 16-seat minibuses; these include Rabbie’s (tel. 0131/212-5005, www.rabbies.com) and Heart of Scotland Tours: The Wee Red Bus (10 percent Rick Steves discount on full-price day tours—mention when booking, does not apply to overnight tours or senior/student rates, occasionally canceled off-season if too few sign up—leave a contact number, tel. 0131/228-2888, www.heartofscotlandtours.co.uk, run by Nick Roche).

For young backpackers, Haggis Adventures runs day tours plus overnight trips of up to 10 days (tel. 0131/557-9393, www.haggisadventures.com).

At Discreet Scotland, Matthew Wight and his partners specialize in tours of greater Edinburgh and Scotland in spacious SUVs—good for families (£360/2 people, 8 hours, mobile 0798-941-6990, www.discreetscotland.com).

I’ve outlined two walks in Edinburgh: along the Royal Mile, and through the New Town. Many of the sights we’ll pass on these walks are described in more detail later, under “Sights in Edinburgh.”

4 Bank/High Streets Intersection

10 Scottish Parliament Building

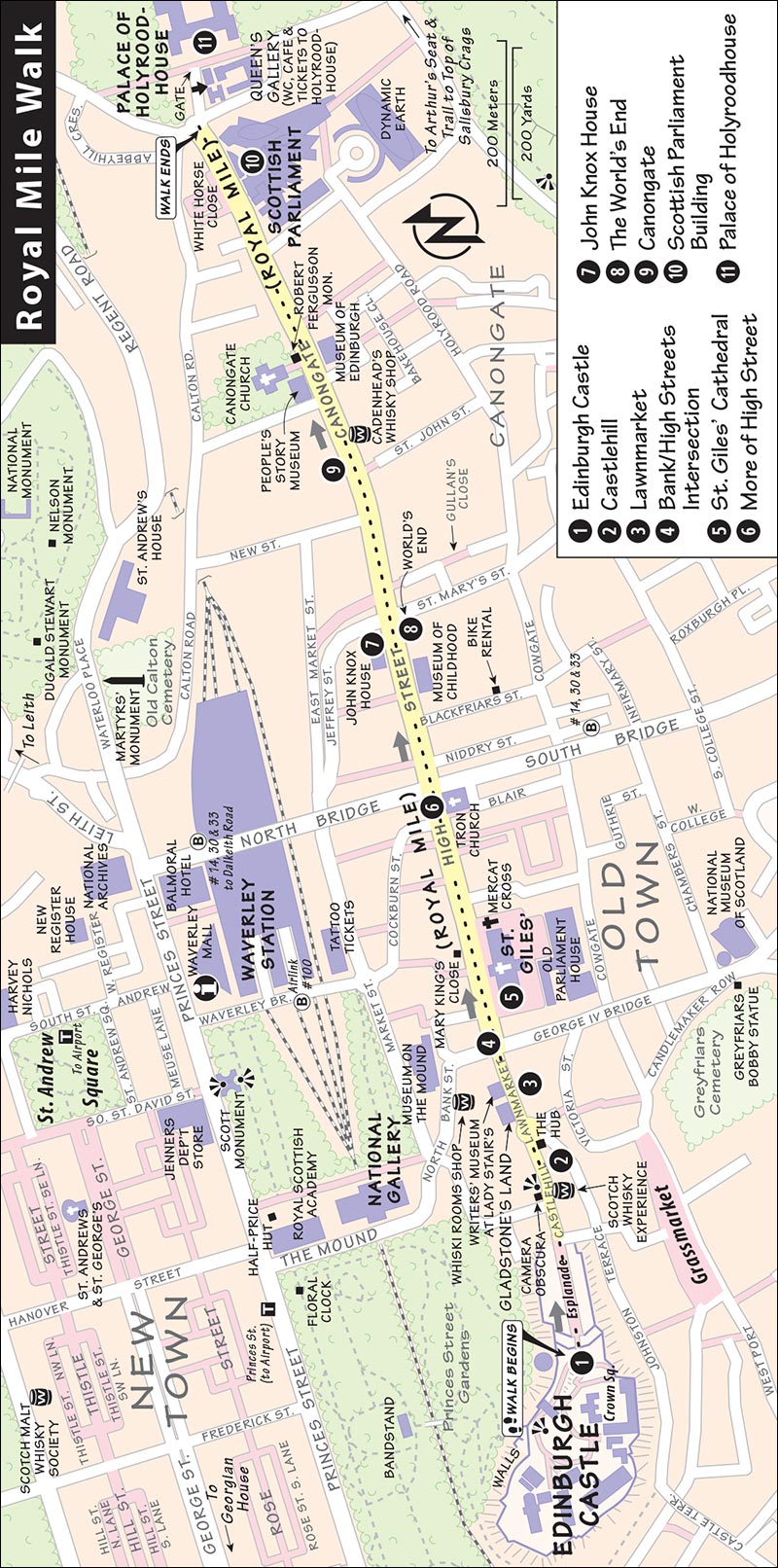

(See “Royal Mile Walk” map, here.)

The Royal Mile is one of Europe’s most interesting historic walks—it’s worth ▲▲▲. The following self-guided stroll is also available as a  downloadable Rick Steves audio tour; see here.

downloadable Rick Steves audio tour; see here.

Start at Edinburgh Castle at the top and amble down to the Palace of Holyroodhouse. Along the way, the street changes names—Castlehill, Lawnmarket, High Street, and Canongate—but it’s a straight, downhill shot totaling just over one mile. And nearly every step is packed with shops, cafés, and lanes leading to tiny squares.

The city of Edinburgh was born on the easily defended rock at the top, where the castle stands today. Celtic tribes (and maybe the Romans) once occupied this site. As the town grew, it spilled downhill along the sloping ridge that became the Royal Mile. Because this strip of land is so narrow, there was no place to build but up. So in medieval times, it was densely packed with multistory “tenements”—large edifices under one roof that housed a number of tenants.

As you walk, you’ll be tracing the growth of the city—its birth atop Castle Hill, its Old Town heyday in the 1600s, its expansion in the 1700s into the Georgian New Town (leaving the old quarter an overcrowded, disease-ridden Victorian slum), and on to the 21st century at the modern Scottish parliament building (2004).

In parts, the Royal Mile feels like one long Scottish shopping mall, selling all manner of kitschy souvenirs (known locally as “tartan tat”), shortbread, and whisky. But the streets are also packed with history, and if you push past the postcard racks into one of the many side alleys, you can still find a few surviving rough edges of the old city. Despite the drizzle, be sure to look up—spires, carvings, and towering Gothic “skyscrapers” give this city its unique urban identity.

This walk covers the Royal Mile’s landmarks, but skips the many museums and indoor attractions along the way. These and other sights are described in walking order under “Sights in Edinburgh” on here. You can stay focused on the walk (which takes about 1.5 hours, without entering sights), then return later to visit the various indoor attractions; or review the sight descriptions beforehand and pop into those that interest you as you pass them.

• We’ll start at the Castle Esplanade, the big parking lot at the entrance to...

Edinburgh was born on the bluff—a big rock—where the castle now stands. Since before recorded history, people have lived on this strategic, easily defended perch.

The castle is an imposing symbol of Scottish independence. Flanking the entryway are statues of the fierce warriors who battled English invaders, William Wallace (on the right) and Robert the Bruce (left). Between them is the Scottish motto, Nemo me impune lacessit—roughly, “No one messes with me and gets away with it.” (For a self-guided tour of Edinburgh Castle, see here.)

The esplanade—built as a military parade ground (1816)—is now the site of the annual Military Tattoo. This spectacular massing of regimental bands fills the square nightly for most of August. Fans watch from temporary bleacher seats to see kilt-wearing bagpipers marching against the spectacular backdrop of the castle. TV crews broadcast the spectacle to all corners of the globe.

When the bleachers aren’t up, there are fine views in both directions from the esplanade. Facing north, you’ll see the body of water called the Firth of Forth, and Fife beyond that. (The Firth of Forth is the estuary where the River Forth flows into the North Sea.) Still facing north, find the lacy spire of the Scott Monument and two Neoclassical buildings housing art galleries. Beyond them, the stately buildings of Edinburgh’s New Town rise. (For a self-guided walk of the New Town, see here.) Panning to the right, find the Nelson Monument and some faux Greek ruins atop Calton Hill (see here).

The city’s many bluffs, crags, and ridges were built up by volcanoes, then carved down by glaciers—a city formed in “fire and ice,” as the locals say. So, during the Ice Age, as a river of glaciers swept in from the west (behind today’s castle), it ran into the super-hard volcanic basalt of Castle Rock and flowed around it, cutting valleys on either side and leaving a tail that became the Royal Mile you’re about to walk.

At the bottom of the esplanade, where the square hits the road, look left to find a plaque on the wall above the tiny witches’ well (now a planter). This memorializes 300 women who were accused of witchcraft and burned here. Below was the Nor’ Loch, the swampy lake where those accused of witchcraft (mostly women) were tested: Bound up, they were dropped into the lake. If they sank and drowned, they were innocent. If they floated, they were guilty, and were burned here in front of the castle, providing the city folk a nice afternoon out. The plaque shows two witches: one good and one bad. Tickle the serpent’s snout to sympathize with the witches. (I just made that up.)

• Start walking down the Royal Mile. The first block is a street called...

You’re immediately in the tourist hubbub. The big tank-like building on your left was the Old Town’s reservoir. You’ll see the wellheads it served all along this walk. While it once held 1.5 million gallons of water, today it’s filled with the touristy Tartan Weaving Mill and Exhibition. While it’s interesting to see the mill at work, you’ll have to twist your way down through several floors of tartanry and Chinese-produced Scottish kitsch to reach it at the bottom level.

The black-and-white tower ahead on the left has entertained visitors since the 1850s with its camera obscura, a darkened room where a mirror and a series of lenses capture live images of the city surroundings outside. (Giggle at the funny mirrors as you walk fatly by.) Across the street, filling the old Castlehill Primary School, is a gimmicky-if-intoxicating whisky-sampling exhibit called the Scotch Whisky Experience (a.k.a. “Malt Disney”). Both of these are described later, under “Sights in Edinburgh.”

• Just ahead, in front of the church with the tall, lacy spire, is the old market square known as...

During the Royal Mile’s heyday, in the 1600s, this intersection was bigger and served as a market for fabric (especially “lawn,” a linen-like cloth). The market would fill this space with hustle, bustle, and lots of commerce. The round white hump in the middle of the roundabout is all that remains of the official weighing beam called the Butter Tron—where all goods sold were weighed for honesty and tax purposes.

Towering above Lawnmarket, with the tallest spire in the city, is the former Tolbooth Church. This impressive Neo-Gothic structure (1844) is now home to the Hub, Edinburgh’s festival-ticket and information center. The world-famous Edinburgh Festival fills the month of August with cultural action. The various festivals feature classical music, traditional and fringe theater (especially comedy), art, books, and more. Drop inside the building to get festival info (see also here). This is a handy stop for its WC, café, and free Wi-Fi.

In the 1600s, this—along with the next stretch, called High Street—was the city’s main street. At that time, Edinburgh was bursting with breweries, printing presses, and banks. Tens of thousands of citizens were squeezed into the narrow confines of the Old Town. Here on this ridge, they built tenements (multiple-unit residences) similar to the more recent ones you see today. These tenements, rising 10 stories and more, were some of the tallest domestic buildings in Europe. The living arrangements shocked class-conscious English visitors to Edinburgh because the tenements were occupied by rich and poor alike—usually the poor in the cellars and attics, and the rich in the middle floors.

• Continue a half-block down the Mile.

Gladstone’s Land (at #477b, on the left), a surviving original tenement, was acquired by a wealthy merchant in 1617. Stand in front of the building and look up at this centuries-old skyscraper. This design was standard for its time: a shop or shops on the ground floor, with columns and an arcade, and residences on the floors above. Because window glass was expensive, the lower halves of window openings were made of cheaper wood, which swung out like shutters for ventilation—and were convenient for tossing out garbage. (Gladstone’s Land can be seen by tour only and is closed Nov-March—consider dropping in and booking ahead for a spot. For details, see listing on here.) Out front, you may also see trainers with live birds of prey. While this is mostly just a fun way to show off for tourists (and raise donations for the Just Falconry center), docents explain the connection: The building’s owner was named Thomas Gledstanes—and gled is the Scots word for “hawk.”

Branching off the spine of the Royal Mile are a number of narrow alleyways that go by various local names. A “wynd” (rhymes with “kind”) is a narrow, winding lane. A “pend” is an arched gateway. “Gate” is from an Old Norse word for street. And a “close” is a tiny alley between two buildings (originally with a door that “closed” at night). A “close” usually leads to a “court,” or courtyard.

To explore one of these alleyways, head into Lady Stair’s Close (on the left, 10 steps downhill from Gladstone’s Land). This alley pops out in a small courtyard, where you’ll find the Writers’ Museum (described on here). It’s well worth a visit for fans of Scotland’s holy trinity of writers (Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Louis Stevenson), but it’s also a free glimpse of what a typical home might have looked like in the 1600s. Burns actually lived for a while in this neighborhood, in 1786, when he first arrived in Edinburgh.

Opposite Gladstone’s Land (at #322), another close leads to Riddle’s Court. Wander through here and imagine Edinburgh in the 17th and 18th centuries, when tourists came here to marvel at its skyscrapers. Some 40,000 people were jammed into the few blocks between here and the World’s End pub (which we’ll reach soon). Visualize the labyrinthine maze of the old city, with people scurrying through these back alleyways, buying and selling, and popping into taverns.

No city in Europe was as densely populated—or perhaps as filthy. Without modern hygiene, it was a living hell of smoke, stench, and noise, with the constant threat of fire, collapse, and disease. The dirt streets were soiled with sewage from bedpans emptied out windows. By the 1700s, the Old Town was rife with poverty and cholera outbreaks. The smoky home fires rising from tenements and the infamous smell (or “reek” in Scottish) that wafted across the city gave it a nickname that sticks today: “Auld Reekie.”

• Return to the Royal Mile and continue down it a few steps to take in some sights at the...

A number of sights cluster here, where Lawnmarket changes its name to High Street and intersects with Bank Street and George IV Bridge.

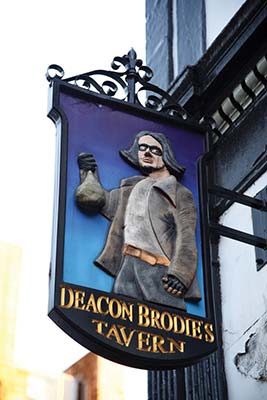

Begin with Deacon Brodie’s Tavern. Read the “Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” story of this pub’s notorious namesake on the wall facing Bank Street. Then, to see his spooky split personality, check out both sides of the hanging signpost. Brodie—a pillar of the community by day but a burglar by night—epitomizes the divided personality of 1700s Edinburgh. It was a rich, productive city—home to great philosophers and scientists, who actively contributed to the Enlightenment. Meanwhile, the Old Town was riddled with crime and squalor. The city was scandalized when a respected surgeon—driven by a passion for medical research and needing corpses—was accused of colluding with two lowlifes, named Burke and Hare, to acquire freshly murdered corpses for dissection. (In the next century, in the late 1800s, novelist Robert Louis Stevenson would capture the dichotomy of Edinburgh’s rich-poor society in his Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.)

In the late 1700s, Edinburgh’s upper class moved out of the Old Town into a planned community called the New Town (a quarter-mile north of here). Eventually, most tenements were torn down and replaced with newer Victorian buildings. You’ll see some at this intersection.

Look left down Bank Street to the green-domed Bank of Scotland. This was the headquarters of the bank, which had practiced modern capitalist financing since 1695. The building now houses the Museum on the Mound, a free exhibit on banking history (see here), and is also the Scottish headquarters for Lloyds Banking Group—which swallowed up the Bank of Scotland after the financial crisis of 2008.

If you detour left down Bank Street toward the bank, you’ll find the recommended Whiski Rooms Shop. If you head in the opposite direction, down George IV Bridge, you’ll reach the excellent National Museum of Scotland, the famous Greyfriars Bobby statue, restaurant-lined Forrest Road, and photogenic Victoria Street, which leads to the pub-lined Grassmarket square (all described later in this chapter).

Otherwise, continue along the Royal Mile. As you walk, be careful crossing the streets along the Mile. Edinburgh drivers—especially cabbies—have a reputation for being impatient with jaywalking tourists. Notice and heed the pedestrian crossing signals, which don’t always turn at the same time as the car signals.

Across the street from Deacon Brodie’s Tavern is a seated green statue of hometown boy David Hume (1711-1776)—one of the most influential thinkers not only of Scotland, but in all of Western philosophy. The atheistic Hume was one of the towering figures of the Scottish Enlightenment of the mid-1700s. Thinkers and scientists were using the experimental method to challenge and investigate everything, including religion. Hume questioned cause and effect in thought puzzles such as this: We can see that when one billiard ball strikes another, the second one moves, but how do we know the collision “caused” the movement? Notice his shiny toe: People on their way to trial (in the high court just behind the statue) or students on their way to exams (in the nearby university) rub it for good luck.

Follow David Hume’s gaze to the opposite corner, where a brass H in the pavement marks the site of the last public execution in Edinburgh in 1864. Deacon Brodie himself would have been hung about here (in 1788, on a gallows whose design he had helped to improve—smart guy).

• From the brass H, continue down the Royal Mile, pausing just before the church square at a stone wellhead with the pyramid cap.

All along the Royal Mile, wellheads like this (from 1835) provided townsfolk with water in the days before buildings had plumbing. This neighborhood well was served by the reservoir up at the castle. Imagine long lines of people in need of water standing here, gossiping and sharing the news. Eventually buildings were retrofitted with water pipes—the ones you see running along building exteriors.

• Ahead of you (past the Victorian statue of some duke), embedded in the pavement near the street, is a big heart.

The Heart of Midlothian marks the spot of the city’s 15th-century municipal building and jail. In times past, in a nearby open space, criminals were hanged, traitors were decapitated, and witches were burned. Citizens hated the rough justice doled out here. Locals still spit on the heart in the pavement. Go ahead...do as the locals do—land one right in the heart of the heart. By the way, Edinburgh has two soccer teams—Heart of Midlothian (known as “Hearts”) and Hibernian (“Hibs”). If you’re a Hibs fan, spit again.

• Make your way to the entrance of the church.

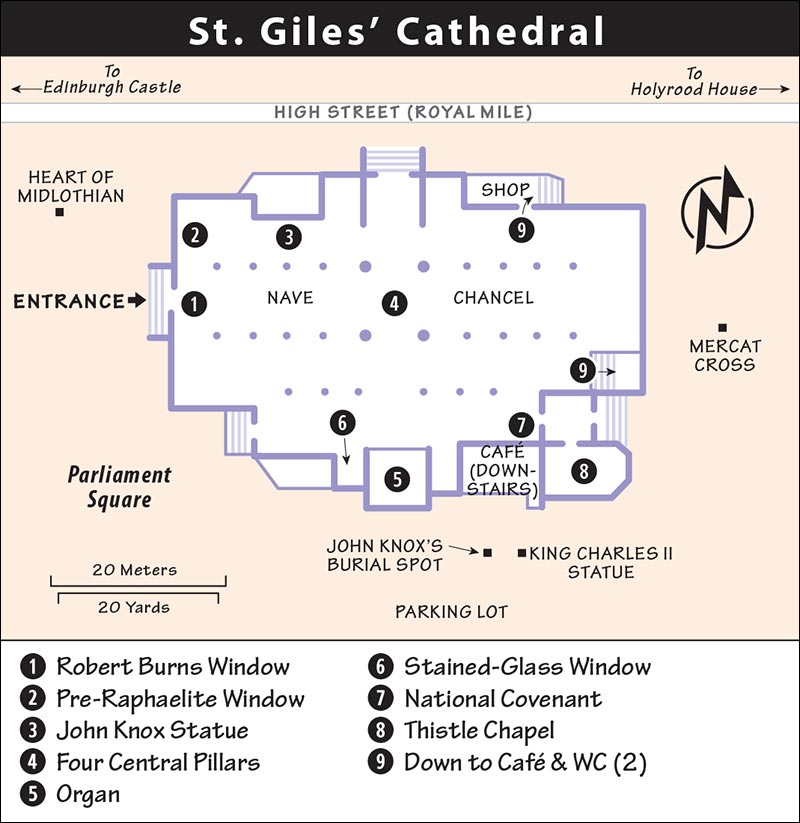

This is the flagship of the Church of Scotland (Scotland’s largest denomination)—called the “Mother Church of Presbyterianism.” The interior serves as a kind of Scottish Westminster Abbey, filled with monuments, statues, plaques, and stained-glass windows dedicated to great Scots and moments in history.

A church has stood on this spot since 854, though this structure is an architectural hodgepodge, dating mostly from the 15th through 19th century. In the 16th century, St. Giles’ was a kind of national stage on which the drama of the Reformation was played out. The reformer John Knox (1514-1572) was the preacher here. His fiery sermons helped turn once-Catholic Edinburgh into a bastion of Protestantism. During the Scottish Reformation, St. Giles’ was transformed from a Catholic cathedral to a Presbyterian church. The spacious interior is well worth a visit, and described in my self-guided tour on here.

• Facing the church entrance, curl around its right side, into a parking lot.

The grand building across the parking lot from St. Giles’ is the Old Parliament House. Since the 13th century, the king had ruled a rubber-stamp parliament of nobles and bishops. But the Protestant Reformation promoted democracy, and the parliament gained real power. From the early 1600s until 1707, this building evolved to become the seat of a true parliament of elected officials. That came to an end in 1707, when Scotland signed an Act of Union, joining what’s known today as the United Kingdom and giving up their right to self-rule. (More on that later in the walk.) If you’re curious to peek inside, head through the door at #11 (free, described on here).

The great reformer John Knox is buried—with appropriate austerity—under parking lot spot #23. The statue among the cars shows King Charles II riding to a toga party back in 1685.

•Continue on through the parking lot, around the back end of the church.

Every Scottish burgh (town licensed by the king to trade) had three standard features: a “tolbooth” (basically a Town Hall, with a courthouse, meeting room, and jail); a “tron” (official weighing scale); and a “mercat” (or market) cross. The mercat cross standing just behind St. Giles’ Cathedral has a slender column decorated with a unicorn holding a flag with the cross of St. Andrew. Royal proclamations have been read at this mercat cross since the 14th century. In 1952, a town crier heralded the news that Britain had a new queen—three days after the actual event (traditionally the time it took for a horse to speed here from London). Today, Mercat Cross is the meeting point for many of Edinburgh’s walking tours—both historic and ghostly.

• Circle around to the street side of the church.

The statue to Adam Smith honors the Edinburgh author of the pioneering Wealth of Nations (1776), in which he laid out the economics of free-market capitalism. Smith theorized that an “invisible hand” wisely guides the unregulated free market. Stand in front of Smith and imagine the intellectual energy of Edinburgh in the mid-1700s, when it was Europe’s most enlightened city. Adam Smith was right in the center of it. He and David Hume were good friends. James Boswell, the famed biographer of Samuel Johnson, took classes from Smith. James Watt, inventor of the steam engine, was another proud Scotsman of the age. With great intellectuals like these, Edinburgh helped create the modern world. The poet Robert Burns, geologist James Hutton (who’s considered the father of modern geology), and the publishers of the first Encyclopedia Britannica all lived in Edinburgh. Steeped in the inquisitive mindset of the Enlightenment, they applied cool rationality and a secular approach to their respective fields.

• Head on down the Royal Mile.

A few steps downhill, at #188 (on the right), is the Police Information Center. This place provides a pleasant police presence (say that three times) and a little local law-and-order history to boot. Ask the officer on duty about the impact of modern technology and budget austerity on police work today. Seriously—drop in and discuss whatever law-and-order issue piques your curiosity.

Continuing down this stretch of the Royal Mile, which is traffic-free most of the day (notice the bollards that raise and lower for permitted traffic), you’ll see the Fringe Festival office (at #180), street musicians, and another wellhead (with horse “sippies,” dating from 1675).

Notice those three red boxes. In the 20th century, people used these to make telephone calls to each other. (Imagine that!) These cast-iron booths are produced for all of Britain here in Scotland. As phone booths are decommissioned, some are finding new use as tiny shops, ATMs, and even showing up in residential neighborhoods as nostalgic garden decorations.

At the next intersection, on the left, is Cockburn Street (pronounced “COE-burn”). This was cut through High Street’s dense wall of medieval skyscrapers in the 1860s to give easy access to the Georgian New Town and the train station. Notice how the sliced buildings were thoughtfully capped with facades that fit the aesthetic look of the Royal Mile. In the Middle Ages, only tiny lanes (like Fleshmarket Close just uphill from Cockburn Street) interrupted the long line of Royal Mile buildings. These days, Cockburn Street has a reputation for its eclectic independent shops and string of trendy bars and eateries.

• When you reach the Tron Church (17th century, currently housing shops), you’re at the intersection of North and South Bridge streets. These major streets lead left to Waverley Station and right to the Dalkeith Road B&Bs. Several handy bus lines run along here.

This is the halfway point of this walk. Stand on the corner diagonally across from the church. Look up to the top of the Royal Mile at the Hub and its 240-foot spire. Notwithstanding its turret and 16th-century charm, the Radisson Blu Hotel just across the street is entirely new construction (1990), built to fit in. The city is protecting its historic look. The Inn on the Mile next door was once a fancy bank with a lavish interior. As modern banks are moving away from city centers, sumptuous buildings like these are being converted into ornate pubs and restaurants.

In the next block downhill are three characteristic pubs, side by side, that offer free traditional Scottish and folk music in the evenings. Notice the chimneys. Tenement buildings shared stairways and entries, but held individual apartments, each with its own chimney. Take a look back at the spire of St. Giles’ Cathedral—inspired by the Scottish crown and the thistle, Scotland’s national flower.

• Go down High Street another block, passing near the Museum of Childhood (on the right, at #42, and worth a stop; see here) and a fragrant fudge shop a few doors down, where you can sample various flavors (tempting you to buy a slab).

Directly across the street, just below another wellhead, is the...

Remember that Knox was a towering figure in Edinburgh’s history, converting Scotland to a Calvinist style of Protestantism. His religious bent was “Presbyterianism,” in which parishes are governed by elected officials rather than appointed bishops. This more democratic brand of Christianity also spurred Scotland toward political democracy. If you’re interested in Knox or the Reformation, this sight is worth a visit (see here). Full disclosure: It’s not certain that Knox ever actually lived here. Attached to the Knox House is the Scottish Storytelling Centre, where locals with the gift of gab perform regularly; check the posted schedule.

• A few steps farther down High Street, at the intersection with St. Mary’s and Jeffrey streets, you’ll reach...

For centuries, a wall stood here, marking the end of the burgh of Edinburgh. For residents within the protective walls of the city, this must have felt like the “world’s end,” indeed. The area beyond was called Canongate, a monastic community associated with Holyrood Abbey. At the intersection, find the brass bricks in the street that trace the gate (demolished in 1764). Look to the right down St. Mary’s Street about 200 yards to see a surviving bit of that old wall, known as the Flodden Wall. In the 1513 Battle of Flodden, the Scottish king James IV made the disastrous decision to invade northern England. James and 10,000 of his Scotsmen were killed. Fearing a brutal English counterattack, Edinburgh scrambled to reinforce its broken-down city wall. To the left, down Jeffrey Street, you’ll see Scotland’s top tattoo parlor, and a supplier for a different kind of tattoo (the Scottish Regimental Store).

• Continue down the Royal Mile—leaving old Edinburgh—as High Street changes names to...

About 10 steps down Canongate, look left down Cranston Street (past the train tracks) to a good view of the Calton Cemetery up on Calton Hill. The obelisk, called Martyrs’ Monument, remembers a group of 18th-century patriots exiled by London to Australia for their reform politics. The round building to the left is the grave of philosopher David Hume. And the big, turreted building to the right was the jail master’s house. Today, the main reason to go up Calton Hill is for the fine views (described on here).

The giant, blocky building that dominates the lower slope of the hill is St. Andrew’s House, headquarters of the Scottish Government—including the office of the first minister of Scotland. According to locals, the building has also been an important base for MI6, Britain’s version of the CIA. Wait a minute—isn’t James Bond Scottish? Hmmm...

• A couple hundred yards farther along the Royal Mile (on the right at #172) you reach Cadenhead’s, a serious place to learn about and buy whisky (see here). About 30 yards farther along, you’ll pass two worthwhile and free museums, the People’s Story Museum (on the left, in the old tollhouse at #163) and the Museum of Edinburgh (on the right, at #142; for more on both, see here). But our next stop is the church just across from the Museum of Edinburgh.

The 1688 Canongate Kirk (Church)—located not far from the royal residence of Holyroodhouse—is where Queen Elizabeth II and her family worship whenever they’re in town. (So don’t sit in the front pew, marked with her crown.) The gilded emblem at the top of the roof, high above the door, has the antlers of a stag from the royal estate of Balmoral (see here). The Queen’s granddaughter married here in 2011.

The church is open only when volunteers have signed up to welcome visitors (and closed in winter). Chat them up and borrow the description of the place. Then step inside the lofty blue and red interior, renovated with royal money; the church is filled with light and the flags of various Scottish regiments. In the narthex, peruse the photos of royal family events here, and find the list of priests and ministers of this parish—it goes back to 1143 (with a clear break with the Reformation in 1561).

Outside, turn right as you leave the church and walk up into the graveyard. The large, gated grave (abutting the back of the People’s Story Museum) is the affectionately tended tomb of Adam Smith, the father of capitalism. (Throw him a penny or two.)

Just outside the churchyard, the statue on the sidewalk is of the poet Robert Fergusson. One of the first to write verse in the Scots language, he so inspired Robert Burns that Burns paid for Fergusson’s tombstone in the Canongate churchyard and composed his epitaph.

Now look across the street at the gabled house next to the Museum of Edinburgh. Scan the facade to see shells put there in the 17th century to defend against the evil power of witches yet to be drowned.

• Walk about 300 yards farther along. In the distance you can see the Palace of Holyroodhouse (the end of this walk) and soon, on the right, you’ll come to the modern Scottish parliament building.

Just opposite the parliament building is White Horse Close (on the left, in the white arcade). Step into this 17th-century courtyard. It was from here that the Edinburgh stagecoach left for London. Eight days later, the horse-drawn carriage would pull into its destination: Scotland Yard. Note that bus #35 leaves in two directions from here—downhill for the Royal Yacht Britannia, and uphill along the Royal Mile (as far as South Bridge) and on to the National Museum of Scotland.

• Now walk up around the corner to the flagpoles (flying the flags of Europe, Britain, and Scotland) in front of the...

Finally, after centuries of history, we reach the 21st century. And finally, after three centuries of London rule, Scotland has a parliament building...in Scotland. When Scotland united with England in 1707, its parliament was dissolved. But in 1999, the Scottish parliament was reestablished, and in 2004, it moved into this striking new home. Notice how the eco-friendly building, by the Catalan architect Enric Miralles, mixes wild angles, lots of light, bold windows, oak, and native stone into a startling complex. (People from Catalunya—another would-be breakaway nation—have an affinity for Scotland.) From the front of the parliament building, look in the distance at the rocky Salisbury Crags, with people hiking the traverse up to the dramatic next summit called Arthur’s Seat. Now look at the building in relation to the craggy cliffs. The architect envisioned the building as if it were rising right from the base of Arthur’s Seat, almost bursting from the rock.

Since it celebrates Scottish democracy, the architecture is not a statement of authority. There are no statues of old heroes. There’s not even a grand entry. You feel like you’re entering an office park. Given its neighborhood, the media often calls the Scottish Parliament “Holyrood” for short (similar to calling the US Congress “Capitol Hill”). For details on touring the building and seeing parliament in action, see here.

• Across the street is the Queen’s Gallery, where she shares part of her amazing personal art collection in excellent revolving exhibits (see here). Finally, walk to the end of the road (Abbey Strand), and step up to the impressive wrought-iron gate of the Queen’s palace. Look up at the stag with its holy cross, or “holy rood,” on its forehead, and peer into the palace grounds. (The ticket office and palace entryway, a fine café, and a handy WC are just through the arch on the right.)

Since the 16th century, this palace has marked the end of the Royal Mile. An abbey—part of a 12th-century Augustinian monastery—originally stood in its place. While most of that old building is gone, you can see the surviving nave behind the palace on the left. According to one legend, it was named “holy rood” for a piece of the cross, brought here as a relic by Queen (and later Saint) Margaret. (Another version of the story is that King David I, Margaret’s son, saw the image of a cross upon a stag’s head while hunting here and took it as a sign that he should build an abbey on the site.) Because Scotland’s royalty preferred living at Holyroodhouse to the blustery castle on the rock, the palace grew over time. If the Queen’s not visiting, the palace welcomes visitors (see here for details).

• Your walk—from the castle to the palace, with so much Scottish history packed in between—is complete. And, if your appetite is whetted for more, don’t worry; you’ve just scratched the surface. Enjoy the rest of Edinburgh.

(See “Bonnie Wee New Town Walk” map, here.)

Many visitors, mesmerized by the Royal Mile, never venture to the New Town. And that’s a shame. With some of the city’s finest Georgian architecture (from its 18th-century boom period), the New Town has a completely different character than the Old Town. This self-guided walk—worth ▲▲—gives you a quick orientation in about one hour.

• Begin on Waverley Bridge, spanning the gully between the Old and New towns; to get there from the Royal Mile, just head down the curved Cockburn Street near the Tron Church (or cut down any of the “close” lanes opposite St. Giles’ Cathedral). Stand on the bridge overlooking the train tracks, facing the castle.

View from Waverley Bridge: From this vantage point, you can enjoy fine views of medieval Edinburgh, with its 10-story-plus “skyscrapers.” It’s easy to imagine how miserably crowded this area was, prompting the expansion of the city during the Georgian period. Pick out landmarks along the Royal Mile, most notably the open-work steeple of St. Giles’.

A big lake called the Nor’ Loch once was to the north (nor’) of the Old Town; now it’s a valley between Edinburgh’s two towns. The lake was drained around 1800 as part of the expansion. Before that, the lake was the town’s water reservoir...and its sewer. Much has been written about the town’s infamous stink (a.k.a. the “flowers of Edinburgh”). The town’s nickname, “Auld Reekie,” referred to both the smoke of its industry and the stench of its squalor.

The long-gone loch was also a handy place for drowning witches. With their thumbs tied to their ankles, they’d be lashed to dunking stools. Those who survived the ordeal were considered “aided by the devil” and burned as witches. If they died, they were innocent and given a good Christian burial. Edinburgh was Europe’s witch-burning mecca—any perceived “sign,” including a small birthmark, could condemn you. Scotland burned more witches per capita than any other country—17,000 souls between 1479 and 1722.

Visually trace the train tracks as they disappear into a tunnel below the Scottish National Gallery (with lesser-known paintings by great European artists; you can visit it during this walk—see here). The two fine Neoclassical buildings of the National Gallery date from the 1840s and sit upon a mound that’s called, well, The Mound. When the New Town was built, tons of rubble from the excavations were piled here (1781-1830), forming a dirt bridge that connected the new development with the Old Town to allay merchant concerns about being cut off from the future heart of the city.

Turning 180 degrees (and facing the ramps down into the train station), notice the huge, turreted building with the clock tower. The Balmoral was one of the city’s two grand hotels during its glory days (its opposite bookend, the Waldorf Astoria Edinburgh, sits at the far end of the former lakebed—near the end of this walk). Aristocrats arriving by train could use a hidden entrance to go from the platform directly up to their plush digs. (Today The Balmoral is known mostly as the place where J. K. Rowling completed the final Harry Potter book.)

• Now walk across the bridge toward the New Town. Before the corner, enter the gated gardens on the left, and head toward the big, pointy monument. You’re at the edge of...

1 Princes Street Gardens: This grassy park, filling the former lakebed, offers a wonderful escape from the bustle of the city. Once the private domain of the wealthy, it was opened to the public around 1870—not as a democratic gesture, but in hopes of increasing sales at the Princes Street department stores. Join the office workers for a picnic lunch break.

• Take a seat on the bench indicated by the Livingstone (Dr. Livingstone, I presume?) statue. (The Victorian explorer is well equipped with a guidebook, but is hardly packing light—his lion skin doesn’t even fit in his rucksack carry-on.)

Look up at the towering...

2 Scott Monument: Built in the early 1840s, this elaborate Neo-Gothic monument honors the great author Sir Walter Scott, one of Edinburgh’s many illustrious sons. When Scott died in 1832, it was said that “Scotland never owed so much to one man.” Scott almost singlehandedly created the Scotland we know. Just as the country was in danger of being assimilated into England, Scott celebrated traditional songs, legends, myths, architecture, and kilts, thereby reviving the Highland culture and cementing a national identity. And, as the father of the Romantic historical novel, he contributed to Western literature in general. The 200-foot monument shelters a marble statue of Scott and his favorite pet, Maida, a deerhound who was one of 30 canines this dog lover owned during his lifetime. They’re surrounded by busts of 16 great Scottish poets and 64 characters from his books. Climbing the tight, stony spiral staircase of 287 steps earns you a peek at a tiny museum midway, a fine city view at the top, and intimate encounters going up and down (£5, daily 10:00-19:00, Oct-March until 16:00, tel. 0131/529-4068). For more on Scott, see here.

• Exit the gate near Livingstone and head across busy Princes Street to the venerable...

3 Jenners Department Store: As you wait for the light to change (and wait...and wait...), notice how statues of women support the building—just as real women support the business. The arrival of new fashions here was such a big deal in the old days that they’d announce it by flying flags on the Nelson Monument atop Calton Hill.

Step inside and head upstairs into the grand, skylit atrium. The central space—filled with a towering tree at Christmas—is classic Industrial Age architecture. The Queen’s coat of arms high on the wall indicates she shops here.

• From the atrium, turn right and exit onto South St. David Street. Turn left and follow this street uphill one block up to...

4 St. Andrew Square: This green space is dedicated to the patron saint of Scotland. In the early 19th century, there were no shops around here—just fine residences; this was a private garden for the fancy people living here. Now open to the public, the square is a popular lunch hangout for workers. The Melville Monument honors a powermonger member of parliament who, for four decades (around 1800), was nicknamed the “uncrowned king of Scotland.”

One block up from the top of the park is the excellent Scottish National Portrait Gallery, which introduces you to all of the biggest names in Scottish history (described later, under “Sights in Edinburgh”).

• Follow the Melville Monument’s gaze straight ahead out of the park. Cross the street and stand at the top of...

5 George Street: This is the main drag of Edinburgh’s grid-planned New Town. Laid out in 1776, when King George III was busy putting down a revolution in a troublesome overseas colony, the New Town was a model of urban planning in its day. The architectural style is “Georgian”—British for “Neoclassical.” And the street plan came with an unambiguous message: to celebrate the union of Scotland with England into the United Kingdom. (This was particularly important, since Scotland was just two decades removed from the failed Jacobite uprising of Bonnie Prince Charlie.)

St. Andrew Square (patron saint of Scotland) and Charlotte Square (George III’s queen) bookend the New Town, with its three main streets named for the royal family of the time (George, Queen, and Princes). Thistle and Rose streets—which we’ll see near the end of this walk—are named for the national flowers of Scotland and England.

The plan for the New Town was the masterstroke of the 23-year-old urban designer James Craig. George Street—20 feet wider than the others (so a four-horse carriage could make a U-turn)—was the main drag. Running down the high spine of the area, it afforded grand, unobstructed views (thanks to the parks on either side) of the River Forth in one direction and the Old Town in the other. As you stroll down the street, you’ll notice that Craig’s grid is a series of axes designed to connect monuments new and old; later architects made certain to continue this harmony. For example, notice that the Scott Monument lines up perfectly with this first intersection.

• Halfway down the first block of George Street, on the right, is...

6 St. Andrew’s and St. George’s Church: Designed as part of the New Town plan in the 1780s, the church is a product of the Scottish Enlightenment. It has an elliptical plan (the first in Britain) so that all can focus on the pulpit. If it’s open, step inside. A fine leaflet tells the story of the church, and a handy cafeteria downstairs serves cheap and cheery lunches.

Directly across the street from the church is another temple, this one devoted to money. This former bank building (now housing the recommended restaurant 7 The Dome) has a pediment filled with figures demonstrating various ways to make money, which they do with all the nobility of classical gods. Consider scurrying across the street and ducking inside to view the stunning domed atrium.

Continue down George Street to the intersection with a 8 statue commemorating the visit by King George IV. Notice the particularly fine axis formed by this cross-street: The National Gallery lines up perfectly with the Royal Mile’s skyscrapers and the former Tolbooth Church, creating a Gotham City collage.

• By now you’ve gotten your New Town bearings. Feel free to stop this walk here: If you were to turn left and head down Hanover Street, in a block you’d run into the Scottish National Gallery; the street behind it curves back up to the Royal Mile.

But to see more of the New Town—including the Georgian House, offering an insightful look inside one of these fine 18th-century homes—stick with me for a few more long blocks, zigzagging through side streets to see the various personalities that inhabit this rigid grid.

Turn right on Hanover Street; after just one (short) block, cross over and go down...

9 Thistle Street: Of the many streets in the New Town, this has perhaps the most vivid Scottish character. And that’s fitting, as it’s named after Scotland’s national flower. At the beginning and end of the street, also notice that Craig’s street plan included tranquil cul-de-sacs within the larger blocks. Thistle Street seems sleepy, but holds characteristic boutiques and good restaurants (see “Eating in Edinburgh,” later). Halfway down the street on the left, Howie Nicholsby’s shop, 21st Century Kilt, updates traditional Scottish menswear.

You’ll pop out at Frederick Street. Turning left, you’ll see a 10 statue of William Pitt, prime minister under King George III. (Pitt’s father gave his name to the American city of Pittsburgh—which Scots pronounce as “Pitts-burrah”...I assume.)

• For an interesting contrast, we’ll continue down another side street. Pass the statue of Pitt (heading toward Edinburgh Castle), and turn right onto...

11 Rose Street: As a rose is to a thistle, and as England is to Scotland, so is brash, boisterous Rose Street to sedate, thoughtful Thistle Street. This stretch of Rose Street feels more commercialized, jammed with chain stores; the second block is packed with pubs and restaurants. As you walk, keep an eye out for the cobbled Tudor rose embedded in the brick sidewalk. When you cross the aptly named Castle Street, linger over the grand views to Edinburgh Castle. It’s almost as if they planned it this way...just for the views.

• Popping out at the far end of Rose Street, across the street and to your right is...

12 Charlotte Square: The building of the New Town started cheap with St. Andrew Square, but finished well with this stately space. In 1791, the Edinburgh town council asked the prestigious Scottish architect Robert Adam to pump up the design for Charlotte Square. The council hoped that Adam’s plan would answer criticism that the New Town buildings lacked innovation or ambition—and they got what they wanted. Adam’s design, which raised the standard of New Town architecture to “international class,” created Edinburgh’s finest Georgian square.

• Along the right side of Charlotte Square, at #7 (just left of the pointy pediment), you can visit the 13 Georgian House, which gives you a great peek behind all of these harmonious Neoclassical facades (see here).

When you’re done touring the house, you can head back through the New Town grid, perhaps taking some different streets than the way you came. Or, for a restful return to our starting point, consider this...

Return Through Princes Street Gardens: From Charlotte Square, drop down to busy Princes Street (noticing the red building to the right—the grand Waldorf Astoria Hotel and twin sister of The Balmoral at the start of our walk). But rather than walking along the busy bus-and-tram-lined shopping drag, head into Princes Street Gardens (cross Princes Street and enter the gate on the left). With the castle looming overhead, you’ll pass a playground, a fanciful Victorian fountain, more monuments to great Scots, war memorials, and a bandstand (which hosts Scottish country dancing—see here—as well as occasional big-name acts). Finally you’ll reach a staircase up to the Scottish National Gallery; notice the oldest floral clock in the world on your left as you climb up.

• Our walk is over. From here, you can tour the gallery; head up Bank Street just behind it to reach the Royal Mile; hop on a bus along Princes Street to your next stop (or B&B); or continue through another stretch of the Princes Street Gardens to the Scott Monument and our starting point.

SIGHTS ON AND NEAR THE ROYAL MILE

Writers’ Museum at Lady Stair’s House

▲▲Scottish Parliament Building

SIGHTS SOUTH OF THE ROYAL MILE

▲▲▲National Museum of Scotland

Greyfriars Bobby Statue and Greyfriars Cemetery

▲▲Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

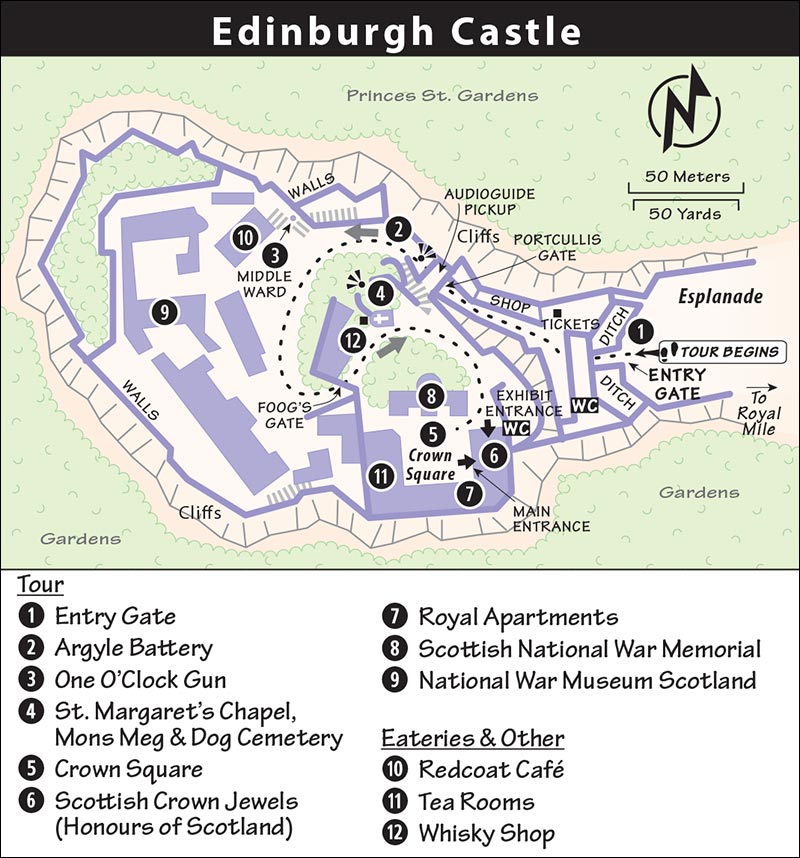

(See “Edinburgh Castle” map, here.)

The fortified birthplace of the city 1,300 years ago, this imposing symbol of Edinburgh sits proudly on a rock high above you. The home of Scotland’s kings and queens for centuries, the castle has witnessed royal births, medieval pageantry, and bloody sieges. Today it’s a complex of various buildings, the oldest dating from the 12th century, linked by cobbled roads that survive from its more recent use as a military garrison. The castle—with expansive views, plenty of history, and the stunning crown jewels of Scotland—is a fascinating and multifaceted sight that deserves several hours of your time.

Cost and Hours: £17, daily 9:30-18:00, Oct-March until 17:00, last entry one hour before closing, tel. 0131/225-9846, www.edinburghcastle.gov.uk.

Avoiding Lines: The castle is usually less crowded after 14:00 or so; if planning a morning visit, the earlier the better. To avoid ticket lines (worst in Aug), book online and print your ticket at home. You can also pick up your prebooked ticket at machines just inside the entrance or at the visitor information desk a few steps uphill on the right. You can also skip the ticket line with a Historic Scotland Explorer Pass (see here for details).

Getting There: Simply walk up the Royal Mile (if arriving by bus from the B&B area south of the city, get off at South Bridge and huff up the Mile for about 15 minutes). Taxis get you closer, dropping you a block below the esplanade at the Hub/Tolbooth Church.

Tours: Thirty-minute introductory guided tours are free with admission (2-4/hour, depart from Argyle Battery, see clock for next departure; fewer off-season). The informative audioguide provides four hours of descriptions, including the National War Museum Scotland (£3 if you purchase with your ticket; £3.50 if you rent it once inside, pick up inside Portcullis Gate).

Eating: You have two choices within the castle. The $ Redcoat Café—just past the Argyle Battery—is a big, bright, efficient cafeteria with great views. The $$ Tea Rooms in Crown Square serves sit-down meals and afternoon tea. A whisky shop, with tastings, is just through Foog’s Gate.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourFrom the 1 entry gate, start winding your way uphill toward the main sights—the crown jewels and the Royal Palace—located near the summit. Since the castle was protected on three sides by sheer cliffs, the main defense had to be here at the entrance. During the castle’s heyday in the 1500s, a 100-foot tower loomed overhead, facing the city.

• Passing through the portcullis gate, you reach the...

2 Argyle (Six-Gun) Battery, with View: These front-loading, cast-iron cannons are from the Napoleonic era (c. 1800), when the castle was still a force to be reckoned with.

From here, look north across the valley to the grid of the New Town. The valley sits where the Nor’ Loch once was; this lake was drained and filled in when the New Town was built in the late 1700s, its swamps replaced with gardens. Later the land provided sites for the Greek-temple-esque Scottish National Gallery and Waverley Station. Looking farther north, you can make out the port town of Leith with its high-rises and cranes, the Firth of Forth, the island of Inchkeith, and—in the far, far distance (to the east)—the cone-like mountain of North Berwick Law, a former volcano.

Now look down. The sheer north precipice looks impregnable. But on the night of March 14, 1314, 30 armed men silently scaled this rock face. They were loyal to Robert the Bruce and determined to recapture the castle, which had fallen into English hands. They caught the English by surprise, took the castle, and—three months later—Bruce defeated the English at the Battle of Bannockburn.

• A little farther along, near the café, is the...

3 One O’Clock Gun: Crowds gather for the 13:00 gun blast, a tradition that gives ships in the bay something to set their navigational devices by. Before the gun, sailors set their clocks with help from the Nelson Monument—that’s the tall pillar in the distance on Calton Hill. The monument has a “time ball” affixed to the cross on top, which drops precisely at the top of the hour. But on foggy days, ships couldn’t see the ball, so the cannon shot was instituted instead (1861). The tradition stuck, every day at 13:00. (Locals joke that the frugal Scots don’t fire it at high noon, as that would cost 11 extra rounds a day.)

• Continue uphill, winding to the left and passing through Foog’s Gate. At the very top of the hill, on your left, is...

4 St. Margaret’s Chapel: This tiny stone chapel is Edinburgh’s oldest building (around 1120) and sits atop its highest point (440 feet). It represents the birth of the city.

In 1057, Malcolm III murdered King Macbeth (of Shakespeare fame) and assumed the Scottish throne. Later, he married Princess Margaret, and the family settled atop this hill. Their marriage united Malcolm’s Highland Scots with Margaret’s Lowland Anglo-Saxons—the cultural mix that would define Edinburgh.

Step inside the tiny, unadorned church—a testament to Margaret’s reputed piety. The style is Romanesque. The nave is wonderfully simple, with classic Norman zigzags decorating the round arch that separates the tiny nave from the sacristy. You’ll see a facsimile of St. Margaret’s 11th-century gospel book. The small (modern) stained-glass windows feature St. Margaret herself, St. Columba, and St. Ninian (who brought Christianity to Scotland in A.D. 397), St. Andrew (Scotland’s patron saint), and William Wallace (the defender of Scotland). These days, the place is popular for weddings. (As it seats only 20, it’s particularly popular with brides’ parents.)

Margaret died at the castle in 1093, and her son King David I built this chapel in her honor (she was sainted in 1250). David expanded the castle and also founded Holyrood Abbey, across town. These two structures were soon linked by a Royal Mile of buildings, and Edinburgh was born.

Mons Meg, in front of the church, is a huge and once-upon-a-time frightening 15th-century siege cannon that fired 330-pound stones nearly two miles. Imagine. It was a gift from Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, to his great-niece’s husband King James II of Scotland.

Nearby, belly up to the banister and look down to find the Dog Cemetery, a tiny patch of grass with a sweet little line of doggie tombstones, marking the graves of soldiers’ faithful canines in arms.

• Continue on, curving downhill into...

5 Crown Square: This courtyard is the center of today’s Royal Castle complex. Get oriented. You’re surrounded by the crown jewels, the Royal Palace (with its Great Hall), and the Scottish National War Memorial.

The castle has evolved over the centuries, and Crown Square is relatively “new.” After the time of Malcolm and Margaret, the castle was greatly expanded by David II (1324-1371), complete with tall towers, a Great Hall, dungeon, cellars, and so on. This served as the grand royal residence for two centuries. Then, in 1571-1573, the Protestant citizens of Edinburgh laid siege to the castle and its Catholic/monarchist holdouts, eventually blasting it to smithereens. (You can tour the paltry remains of the medieval castle in nearby David’s Tower.) The palace was rebuilt nearby—around what is today’s Crown Square.

• We’ll tour the buildings around Crown Square. First up: the crown jewels. Look for two entrances. The one on Crown Square, only open in peak season, deposits you straight into the room with the crown jewels but usually comes with a line. The other entry, around the side (near the WCs), takes you—often at a shuffle—through the interesting, Disney-esque “Honours of Scotland” exhibition, which tells the story of the crown jewels and how they survived the harrowing centuries, but lacks any actual artifacts.

6 Scottish Crown Jewels (Honours of Scotland): For centuries, Scotland’s monarchs were crowned in elaborate rituals involving three wondrous objects: a jewel-studded crown, scepter, and sword. These objects—along with the ceremonial Stone of Scone (pronounced “skoon”)—are known as the “Honours of Scotland.” Scotland’s crown jewels may not be as impressive as England’s, but they’re treasured by locals as a symbol of Scottish nationalism. They’re also older than England’s; while Oliver Cromwell destroyed England’s jewels, the Scots managed to hide theirs.

History of the Jewels: The Honours of Scotland exhibit that leads up to the Crown Room traces the evolution of the jewels, the ceremony, and the often-turbulent journey of this precious regalia. Here’s the SparkNotes version:

In 1306, Robert the Bruce was crowned with a “circlet of gold” in a ceremony at Scone—a town 40 miles north of Edinburgh, which Scotland’s earliest kings had claimed as their capital. Around 1500, King James IV added two new items to the coronation ceremony—a scepter (a gift from the pope) and a huge sword (a gift from another pope). In 1540, James V had the original crown augmented by an Edinburgh goldsmith, giving it the imperial-crown shape it has today.

These Honours were used to crown every monarch: nine-month-old Mary, Queen of Scots (she cried); her one-year-old son James VI (future king of England); and Charles I and II. But the days of divine-right rulers were numbered.

In 1649, the parliament had Charles I (king of both England and Scotland) beheaded. Soon Cromwell’s rabid English antiroyalists were marching on Edinburgh. Quick! Legend says two women scooped up the crown and sword, hid them in their skirts and belongings, and buried them in a church far to the northeast until the coast was clear.

When the monarchy was restored, the regalia were used to crown Scotland’s last king, Charles II (1660). Then, in 1707, the Treaty of Union with England ended Scotland’s independence. The Honours came out for a ceremony to bless the treaty, and were then locked away in a strongbox in the castle. There they lay for over a century, until Sir Walter Scott—the writer and great champion of Scottish tradition—forced a detailed search of the castle in 1818. The box was found...and there the Honours were, perfectly preserved. Within a few years, they were put on display, as they have been ever since.

The crown’s most recent official appearance was in 1999, when it was taken across town to the grand opening of the reinstated parliament, marking a new chapter in the Scottish nation. As it represents the monarchy, the crown is present whenever a new session of parliament opens. (And if Scotland ever secedes, you can be sure that crown will be in the front row.)

The Honours: Finally, you enter the Crown Room to see the regalia itself. The four-foot steel sword was made in Italy under orders of Pope Julius II (the man who also commissioned Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and St. Peter’s Basilica). The scepter is made of silver, covered with gold, and topped with a rock crystal and a pearl. The gem- and pearl-encrusted crown has an imperial arch topped with a cross. Legend says the band of gold in the center is the original crown that once adorned the head of Robert the Bruce.

The Stone of Scone (a.k.a. the “Stone of Destiny”) sits plain and strong next to the jewels. It’s a rough-hewn gray slab of sandstone, about 26 by 17 by 10 inches. As far back as the ninth century, Scotland’s kings were crowned atop this stone, when it stood at the medieval capital of Scone. But in 1296, the invading army of Edward I of England carried the stone off to Westminster Abbey. For the next seven centuries, English (and subsequently British) kings and queens were crowned sitting on a coronation chair with the Stone of Scone tucked in a compartment underneath.

In 1950, four Scottish students broke into Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day and smuggled the stone back to Scotland in an act of foolhardy patriotism. But what could they do with it? After three months, they abandoned the stone, draped in Scotland’s national flag. It was returned to Westminster Abbey, where (in 1953) Queen Elizabeth II was crowned atop it. In 1996, in recognition of increased Scottish autonomy, Elizabeth agreed to let the stone go home, on one condition: that it be returned to Westminster Abbey for all British coronations. One day, the next monarch of the United Kingdom—Prince Charles is first in line—will sit atop it, re-enacting a coronation ritual that dates back a thousand years.

• Exit the crown jewel display, heading down the stairs. But just before exiting into the courtyard, turn left through a door that leads into the...

7 Royal Apartments: Scottish royalty lived in the Royal Palace only when safety or protocol required it (they preferred the Palace of Holyroodhouse at the bottom of the Royal Mile). Here you can see several historic but unimpressive rooms. The first one, labeled Queen Mary’s Chamber, is where Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587), gave birth to James VI of Scotland, who later became King James I of England. Nearby Laich Hall (Lower Hall) was the dining room of the royal family.

The Great Hall (through a separate entrance on Crown Square) was built by James IV to host the castle’s official banquets and meetings. It’s still used for such purposes today. Most of the interior—its fireplace, carved walls, pikes, and armor—is Victorian. But the well-constructed wood ceiling is original. This hammer-beam roof (constructed like the hull of a ship) is self-supporting. The complex system of braces and arches distributes the weight of the roof outward to the walls, so there’s no need for supporting pillars or long cross beams. Before leaving, look for the big iron-barred peephole above the fireplace, on the right. This allowed the king to spy on his subjects while they partied.

• Across the Crown Square courtyard is the...

8 Scottish National War Memorial: This commemorates the 149,000 Scottish soldiers lost in World War I, the 58,000 who died in World War II, and the nearly 800 (and counting) lost in British battles since. This is a somber spot (stow your camera and phone). Paid for by public donations, each bay is dedicated to a particular Scottish regiment. The main shrine, featuring a green Italian-marble memorial that contains the original WWI rolls of honor, sits on an exposed chunk of the castle rock. Above you, the archangel Michael is busy slaying a dragon. The bronze frieze accurately shows the attire of various wings of Scotland’s military. The stained glass starts with Cain and Abel on the left, and finishes with a celebration of peace on the right. To appreciate how important this place is, consider that Scottish soldiers died at twice the rate of other British soldiers in World War I.

• Our final stop is worth the five-minute walk to get there. Backtrack to the café (and One O’Clock Gun), then head downhill to the War Museum. The statue in the courtyard in front of the museum is Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig—the Scotsman who commanded the British Army through the WWI trench warfare of the Battle of the Somme and in Flanders Fields.

9 National War Museum Scotland: This thoughtful museum covers four centuries of Scottish military history. Instead of the usual musty, dusty displays of endless armor, there’s a compelling mix of videos, uniforms, weapons, medals, mementos, and eloquent excerpts from soldiers’ letters.

Here you’ll learn the story of how the fierce and courageous Scottish warrior changed from being a symbol of resistance against Britain to being a champion of that same empire. Along the way, these military men received many decorations for valor and did more than their share of dying in battle. But even when fighting alongside—rather than against—England, Scottish regiments still promoted their romantic, kilted-warrior image.