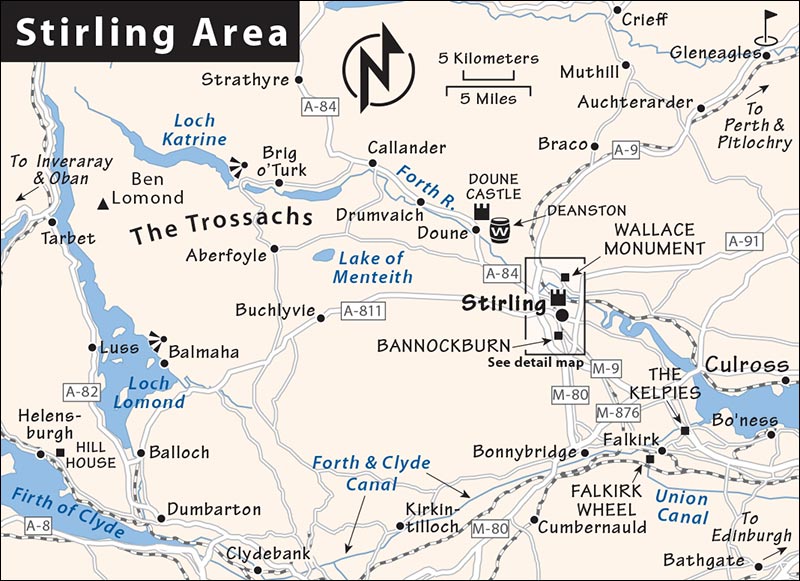

Stirling • Wallace Monument • Bannockburn • Falkirk • Culross • Doune • Loch Lomond and the Trossachs

The historic city of Stirling is the crossroads of Scotland: Equidistant from Edinburgh and Glasgow (less than an hour from both), and rising above a plain where the Lowlands meet the Highlands, it’s no surprise that Stirling has hosted many of the biggest names (and biggest battles) of Scottish history. Everyone from Mary, Queen of Scots to Bonnie Prince Charlie has passed through the gates of its stately, strategic castle.

From the cliff-capping ramparts of Stirling Castle, you can see where each of the three pivotal battles of Scotland’s 13th- and 14th-century Wars of Independence took place: the Battle of Stirling Bridge, where against all odds, the courageous William Wallace defeated the English army; the Battle of Falkirk, where Wallace was toppled by a vengeful English king; and the Battle of Bannockburn, when—in the wake of Wallace’s defeat—Robert the Bruce rallied to kick out the English once and for all (well, at least for a few generations). The Wallace Monument and Bannockburn Heritage Centre—on the outskirts of Stirling, in opposite directions—are practically pilgrimage sites for patriotic Scots.

Stirling itself is sleepy, but it’s a good home base for a variety of side-trips. In Falkirk, take a spin in a fascinating Ferris wheel for boats, and ogle the gigantic horse heads called The Kelpies. Sitting on the nearby estuary known as the Firth of Forth—on the way to Edinburgh or St. Andrews—is the gorgeously preserved time-warp village of Culross. To the north, fans of Monty Python and Outlander flock to Doune Castle. And drivers seeking a quick and easy peek at the Highlands make a loop through the Trossachs and along the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond.

You’ll likely pass near Stirling at least once as you travel through Scotland. Skim this chapter to learn about your options and select the stops that interest you. If you can’t fit it all in on a pass-through, spend the night. Just as Stirling was ideally situated for monarchs and armies of the past, it’s handy for present-day visitors: It’s much smaller, and arguably even more conveniently located, than Edinburgh or Glasgow, and it has a variety of good accommodations. You’d need a solid three days to see all the big sights within an hour’s drive of Stirling—but most people are (and should be) more selective.

Every Scot knows the city of Stirling (pop. 41,000) deep in their bones. This patriotic heart of Scotland is like Bunker Hill, Gettysburg, and the Alamo, all rolled into one. Stirling perches on a ridge overlooking Scotland’s most history-drenched plain: a flat expanse—cut through by the twisting River Forth and the meandering stream called Bannockburn—that divides the Lowlands from the Highlands. And capping that ridge is Stirling’s formidable castle, the seat of the final kings of Scotland.

From a traveler’s perspective, Stirling is a pleasant mini-Edinburgh, with a steep spine leading up to that grand castle. It’s busy with tourists by day, but sleepy at night. The town, and its castle, may lack personality—but both are striking and strategic.

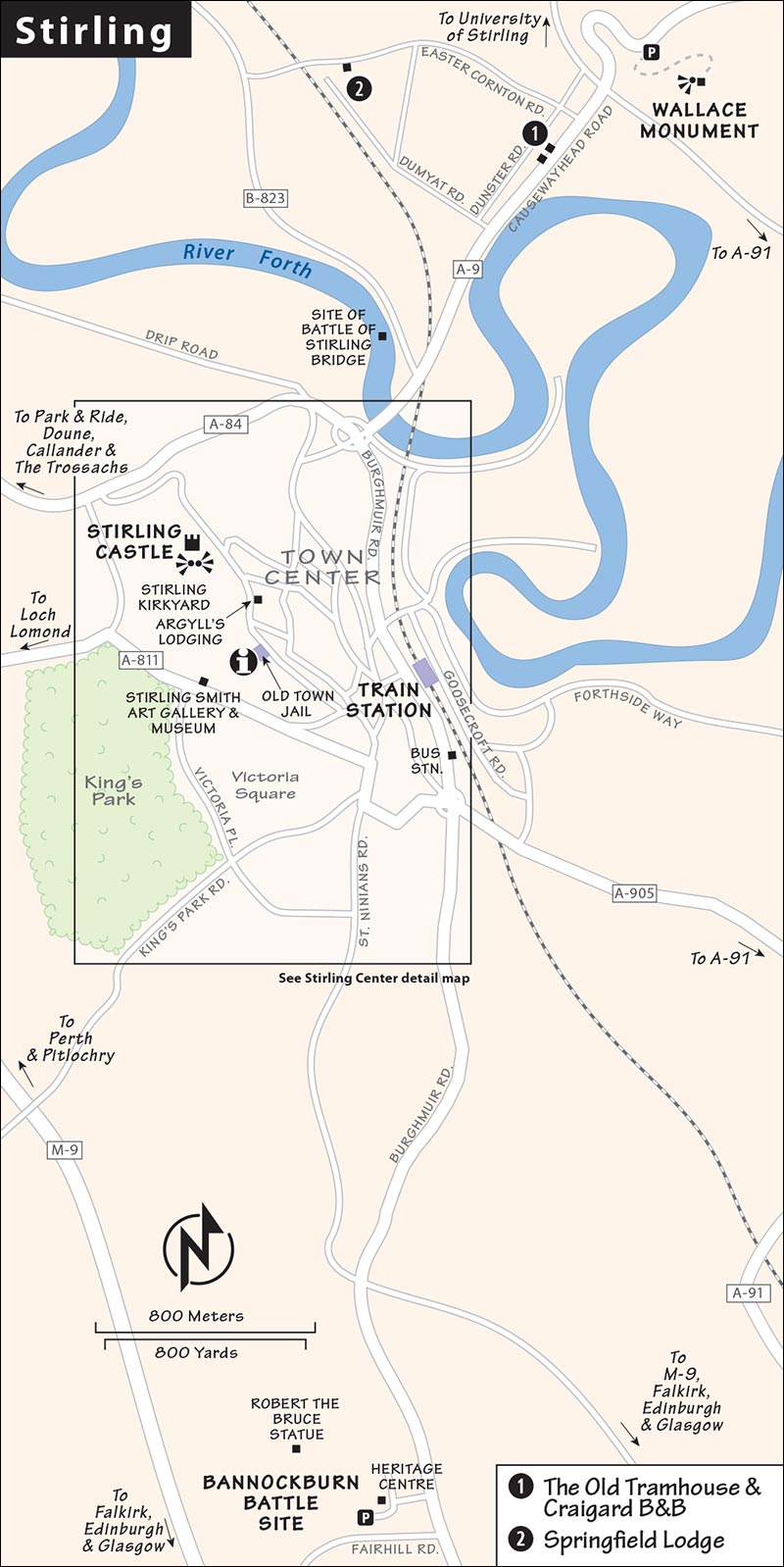

Stirling’s old town is situated along a long, narrow, steep hill. At its base are the train and bus stations and a thriving (but characterless) commercial district; at its apex is the castle. The old town feels like a steeper, shorter, less touristy, and far less characteristic version of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile.

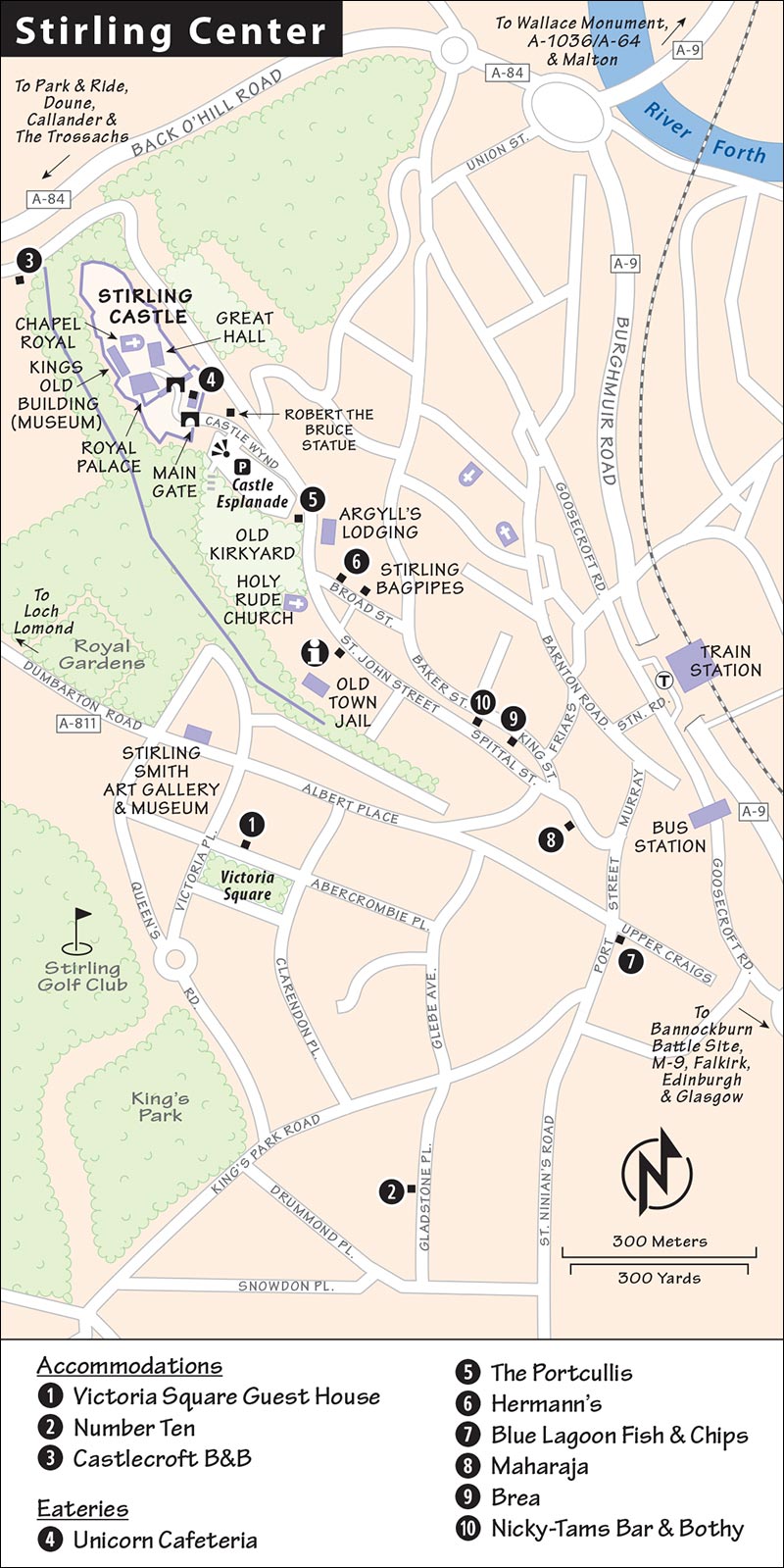

Tourist Information: The TI is a five-minute walk below the castle, just inside the gates of the Old Town Jail (daily 10:00-17:00, free Wi-Fi, St. Johns Street, tel. 01786/475-019).

Getting Around: While the sights within Stirling nestle together at the top of the town, the Wallace Monument and Bannockburn Heritage Centre are an easy bus or taxi ride, or short drive away.

“He who holds Stirling, holds Scotland.” These fateful words have been proven, more often than not, to be true. Stirling Castle’s prized position—perched on a volcanic crag overlooking a bridge over the River Forth, the primary passage between the Lowlands and the Highlands—has long been the key to Scotland. This castle was the preferred home of Scottish kings and queens in the Middle Ages; today it’s one of the most historic—and most popular—castles in Scotland. While its interiors are pretty empty and new-feeling, the castle still has plenty to offer: spectacular views over a gentle countryside, tales of the dynamic Stuart monarchs, and several exhibits that try to bring the place to life.

Cost and Hours: £15, daily April-Sept 9:30-18:00, Oct-March until 17:00, last entry 45 minutes before closing, Regimental Museum closes one hour before castle, good café, tel. 01786/450-000, www.stirlingcastle.gov.uk.

Tours: The included 40-minute guided tour helps you get your bearings—both to the castle, and to Scottish history (generally on the hour 10:00-16:00, often on the half-hour too, departs from inside the main gate near the well). Docents posted throughout can tell you more, and you can rent a £3 audioguide.

Getting There: Stirling Castle sits at the very tip of a steep old town. Drivers should follow the Stirling Castle signs uphill through town to the esplanade and park at the £4 lot just outside the castle gate. Without a car, you can hike the 20-minute uphill route from the train or bus station to the castle, or take a taxi (about £5).

Background: The first real castle was built here in the 12th century by King David I. But Stirling Castle’s glory days were in the 16th century, when it became the primary residence of the Stuart (often spelled “Stewart”) monarchs, who turned it into a showpiece of Scotland—and a symbol of one-upmanship against England.

The 16th century was a busy time for royal intrigues here: James IV married the sister of England’s King Henry VIII, thereby knitting together the royal families of Scotland (the Stuarts) and England (the Tudors). Later, James V further expanded the castle. Mary (who became the Queen of Scots) spent her early childhood at the castle before being raised in France. As queen and as a Catholic, she struggled against the rise of Protestantism in her realm. But when Mary’s son, King James VI, was crowned King James I of England, he took his royal court with him away from Stirling to London—never to return.

During the Jacobite rebellions of the 18th century, the British military took over the castle—bulking it up and destroying its delicate beauty. Even after the Scottish threat had subsided, it remained a British garrison, home base of the Argyll and Sutherland regiments. (You’ll notice the castle still flies the Union Jack of the United Kingdom.) Today, while Stirling Castle is fully restored and gleaming, it feels new and fairly empty—with almost no historic artifacts.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourBegin on the esplanade, just outside the castle entrance, with its grand views.

The Esplanade: The castle’s esplanade, a military parade ground in the 19th century, is a tour-bus parking lot today. As you survey this site, remember that Stirling Castle bore witness to some of the most important moments in Scottish history. To the right as you face the castle, King Robert the Bruce looks toward the plain called Bannockburn, where he defeated the English army in 1314. Squint off to the horizon on Robert’s left to spot the pointy stone monument capping the hill called Abbey Craig. This is the Wallace Monument, marking the spot where the Scottish warrior William Wallace surveyed the battlefield before his victory in the Battle of Stirling Bridge (1297).

These great Scots helped usher in several centuries of home rule. In 1315, Robert the Bruce’s daughter married into an on-the-rise noble clan called the Stuarts, who had distinguished themselves fighting at Bannockburn. When their son Robert became King Robert II of Scotland in 1371, he kicked off the Stuart dynasty. Over the next few generations, their headquarters—Stirling Castle—flourished. The fortified grand entry showed all who approached that James IV (r. 1488-1513) was a great ruler with a powerful castle.

• Head through the first gate into Guardroom Square, where you can buy your ticket, check tour times, and consider renting the audioguide. Then continue up through the inner gate.

Gardens and Battlements: Once through the gate, follow the passage to the left into a delightful grassy courtyard called the Queen Anne Garden. This was the royal family’s playground in the 1600s. Imagine doing a little lawn bowling with the queen here.

In the casemates lining the garden is the Castle Exhibition. Its “Come Face to Face with 1,000 Years of History” exhibit provides an entertaining and worthwhile introduction to the castle. You’ll meet each of the people who left their mark here, from the first Stuart kings to William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. The video leaves you thinking that re-enactors of Jacobite struggles are even more spirited than our Civil War re-enactors.

Leave the garden the way you came and make a sharp U-turn up the ramp to the top of the battlements. From up here, this castle’s strategic position is evident: Defenders had a 360-degree view of enemy armies approaching from miles away. These battlements were built in 1710, long after the castle’s Stuart glory days, in response to the early Jacobite rebellions (from the Latin word for “James”). By this time, the successes of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce were a distant memory; and through the 1707 Act of Union, Scotland had become welded to England. Bonnie Prince Charlie—descendant of those original Stuart “King Jameses” who built this castle—later staged a series of uprisings to try to reclaim the throne of Great Britain for the Stuart line, frightening England enough for it to further fortify the castle. And sure enough, Bonnie Prince Charlie found himself—ironically—laying siege to the fortress that his own ancestors had built: Facing the main gate (with its two round towers below the UK flag), notice the pockmarks from Jacobite cannonballs in 1746.

• Now head back down to the ramp and pass through that main gate, into the...

Outer Close: As you enter this courtyard, straight ahead is James IV’s yellow Great Hall. To the left is his son James V’s royal palace, lined with finely carved Renaissance statues. In 1540, King James V, inspired by French Renaissance châteaux he’d seen, had the castle covered with about 200 statues and busts to “proclaim the peace, prosperity, and justice of his reign” and to validate his rule. Imagine the impression all these classical gods and goddesses made on visitors. The message: James’ rule was a Golden Age for Scotland.

The guided tours of the castle depart from just to your right, near the well. Beyond that is the Grand Battery, with its cannons and rampart views and, underneath that, the Great Kitchens. We’ll see both at the end of this tour.

• Hike up the ramp between James V’s palace and the Great Hall (under the crenellated sky bridge connecting them). You’ll emerge into the...

Inner Close: Standing at the center of Stirling Castle, you’re surrounded by Scottish history. This courtyard was the core of the 12th-century castle. From here, additional buildings were added—each by a different monarch. Facing downhill, you’ll see the Great Hall. To the left is the Chapel Royal—where Mary, Queen of Scots was crowned in 1543. Opposite that, to the right, is the royal palace (containing the Royal Apartments)—notice the “I5” monogram above the windows (for the king who built it: James, or Iacobus in Latin, V). Upstairs in this same palace is the Stirling Heads Gallery. And behind you is the Regimental Museum.

• We’ll visit each of these in turn. First, at the far-left end of the gallery with the coffee stand, step into...

The Great Hall: This is the largest secular space in medieval Scotland. Dating from 1503, this was a grand setting for the great banquets of Scotland’s Renaissance kings. One such party, to which all the crowned heads of Europe were invited, reportedly went on for three full days. This was also where kings and queens would hold court, earning it the nickname “the parliament.” The impressive hammerbeam roof is a modern reconstruction, modeled on the early 16th-century roof at Edinburgh Castle. It’s made of 400 local oak trees, joined by wooden pegs. If you flipped it over, it would float.

• At the far end of the hall, climb a few stairs and walk across the sky bridge into James V’s palace. Here you can explore...

The Royal Apartments: Six ground-floor apartments are colorfully done up as they might have looked in the mid-16th century, when James V and his queen, Mary of Guise, lived here. Costumed performers play the role of palace attendants, happy to chat with you about medieval life. You’ll begin in the King’s Inner Hall, where he received guests. Notice the 60 carved and colorfully painted oak medallions on the ceiling. The medallions are carved with the faces of Scottish and European royalty. These are copies, painstakingly reconstructed after expert research. You’ll soon see the originals up close (and upstairs) in the Stirling Heads Gallery.

Continue (left of the fireplace) into the other rooms (each with actors in costumes who love to interact): the King’s Bedchamber, with a four-poster bed supporting a less-than-luxurious rope mattress; and then the Queen’s Bedchamber, the Inner Hall, and the Outer Hall, offering a more vivid example of what these rich spaces would have looked like.

• From the queen’s apartments, you’ll exit into the top corner of the Inner Close. Directly to your left, up the stairs, is the...

Stirling Heads Gallery: This is, for me, the castle’s highlight—a chance to see the originals of the elaborately carved and painted portrait medallions that decorated the ceiling of the king’s presence chamber. Each one is thoughtfully displayed and lovingly explained. Don’t miss the video at the end of the hall.

• If you were to leave this gallery through the intended exit, you’d wind up back down in the Queen Anne Garden. Instead, backtrack and exit the way you came in to return to the Inner Close, and visit the two remaining sights.

The Chapel Royal: One of the first Protestant churches built in Scotland, the Chapel Royal was constructed in 1594 by James VI for the baptism of his first son, Prince Henry. The faint painted frieze high up survives from Charles I’s coronation visit to Scotland in 1633. Clearly the holiness of the chapel ended in the 1800s when the army moved in.

Regimental Museum: At the top of the Inner Close, in the King’s Old Building, is the excellent Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders Museum. Another highlight of the castle, it’s barely mentioned in castle promotional material because it’s run by a different organization. With lots of tartans, tassels, and swords, it shows how the fighting spirit of Scotland was absorbed by Britain. The two regiments, established in the 1790s to defend Britain in the Napoleonic age and combined in the 1880s, have served with distinction in British military campaigns for more than two centuries. Their pride shows here in the building that has served as their headquarters since 1881. The “In the Trenches” exhibit is a powerful look at World War I, with accounts from the battlefield. Up the spiral stairs, the exhibit continues through World War II and conflicts in the Middle East to the present day.

• When you’re ready to move on, consider the following scenic route back to the castle exit.

Rampart Walk to the Kitchen: The skinny lane between church and museum leads to the secluded Douglas Garden at the rock’s highest point. Belly up to the ramparts for a commanding view, including the Wallace Monument. From here you can walk the ramparts downhill to the Grand Battery, with its cannon rampart back at the Outer Close. The Outer Close was the service zone, with a well and the kitchen (below the cannon rampart). The great banquets of James VI didn’t happen all by themselves, as you’ll appreciate when you explore the fine medieval kitchen exhibit (where mannequin cooks oversee medieval recipes); to find it, head down the ramp and look for the Great Kitchens sign.

• Your castle visit ends here, but your castle ticket includes Argyll’s Lodging, a fortified noble mansion. Or, for a scenic route down into town, consider a detour through an old churchyard cemetery (both described next).

Stirling has a particularly evocative old cemetery in the kirkyard (churchyard) just below the castle. For a soulful stroll, sneak down the stairs where the castle meets the esplanade parking lot (near the statue of the Scotsman fighting in the South African War). From here, you can wander through the tombstones—Celtic crosses, Victorian statues, and faded headstones—from centuries gone by. The rocky crag in the middle of the graveyard is a fine viewpoint. Work your way over to the Church of the Holy Rude (well worth a visit), where you can re-enter the town. From here, Argyll’s Lodging and the castle parking lot are just to the left, and the Old Town Jail (also housing the TI) is just to the right.

Just below the castle esplanade is this 17th-century nobleman’s fortified mansion. European aristocrats wanted to live near power—making this location, where the Earl of Argyll’s family resided for about a century, prime real estate. You’ll get oriented with a historical display on the first floor, then see the kitchens, dining room, drawing room, and bedchambers. Pick up the descriptions in each room, or ask the docents if you have any questions. Argyll’s Lodging is less sterile than the castle and worth a few minutes.

Cost and Hours: Included in castle ticket, daily 12:45-17:30.

David Kinnaird, a local actor/historian, gives history walks by day and haunted walks by night in Stirling. Each walk meets at the TI (inside the gates of the Old Town Jail), lasts 75 minutes, and cost £4 for readers of this book (tel. 01592/874-449, www.stirlingghostwalk.com). Just show up and pay him directly. David’s historic walks (May-Sept Fri-Sun at 12:00, 14:00, and 16:00) tell the story of Stirling as you wander through town. His “Happy Hangman” haunted walks through the old kirkyard cemetery involve more storytelling (July-Aug Tue-Sat at 20:30, Sept-June Fri-Sat at 20:00).

Stirling’s jail was built during the Victorian Age, when the purpose of imprisonment was shifting from punishment to rehabilitation. While there’s little to see today, theatrical 30-minute tours entertain families with a light and funny walk through one section of the jail. You’ll end at the top of the tower for a Q&A with a commanding view of the surrounding countryside.

Cost and Hours: £6.50, July-Sept only, tours every 30 minutes daily 10:15-17:15, St. John Street, www.destinationstirling.com.

This fun little shop, just a block below the castle on Broad Street, is worth a visit for those curious about bagpipes. Owner Alan refurbishes old bagpipes here, but also makes new ones from scratch, in a workshop on the premises. The pleasantly cluttered shop, which is a bit of a neighborhood hangout, is littered with bagpipe components—chanters, drones, bags, covers, and cords. If he’s not too busy, Alan can answer your questions. He’ll explain how the most expensive parts of the bagpipe are the “sticks”—the chanter and drones, carved from blackwood—while the bag and cover are cheap. A serious set costs £700...beginners should instead consider a £40 starter kit that includes a practice chanter (like a recorder) with a book of sheet music and a CD. Alan hopes to open a wee museum next door to show off his collection of historic bagpipes.

Cost and Hours: Free, Mon-Sat 10:00-18:00, closed Sun, 8 Broad Street, tel. 01786/448-886, www.stirlingbagpipes.com.

Nearby: On the wide street in front of the shop, look for Stirling’s mercat cross (“market cross”). A standard feature of any medieval Scottish market town, this was the place where townsfolk would gather for the market, and where royal proclamations were read and executions took place. Today the commercial metabolism of this once-thriving street is at a low ebb. Locals joke that every 100 years, the shopping bustle moves one block farther down the road. These days, it’s squeezed into the modern shopping mall between the old town and the river.

Tucked at the edge of the grid-planned, Victorian Age neighborhood just below the castle, this endearing and eclectic museum is a hodgepodge of artifacts from Stirling’s past: art gallery (where you can meet historical figures with connections to this proud little town), pewter collection, local history exhibits, a steam-powered carriage, the mutton bone shard removed in the world’s first documented tracheotomy (1853), and a 19th-century executioner’s cloak and ax. The museum’s prized piece is what they claim is the world’s oldest surviving soccer ball—a 16th-century stitched-up pig’s bladder that restorers found stuck in the rafters of Stirling Castle. The building is surrounded by a garden filled with public art.

Cost and Hours: Free, Tue-Sat 10:30-17:00, Sun from 14:00, closed Mon, Dumbarton Road, tel. 01786/471-917.

These places are all in large, spacious homes with easy parking.

When Stirling expanded beyond its old walls during the Victorian Age, a modern, grid-planned town sprouted just to the south. Today, this posh-feeling area holds a few B&Bs that are within a (long) walk of Stirling’s old town and castle.

$$$ Victoria Square Guest House has 10 plush rooms in a beautiful location facing a big, grassy park. While the prices are high, it’s neat as a pin, and Kari and Phil keep things running smoothly. It’s about a 10-minute walk to the lower part of town, or 20 minutes up to the castle (no kids under 12, minifridges, 12 Victoria Square, tel. 01786/473-920, www.victoriasquareguesthouse.com, info@vsgh.co.uk).

$ Number Ten rents three nice, traditional rooms in a Scottish-feeling home with tartan carpets blanketing the halls and a lovely garden out back (no kids under 5, 10 Gladstone Place, tel. 01786/472-681, www.cameron-10.co.uk, cameron-10@tinyonline.co.uk, Carol and Donald Cameron).

$$ Castlecroft B&B is well cared for by Laura, who keeps everything immaculate, bakes her own bread, and welcomes guests with tea/coffee and shortbread upon arrival. Just under the castle and overlooking a field with “hairy coos,” it’s a 10-minute walk down a path to the town center. Two of the five rooms come with their own patios, and anyone can make use of the living room and deck (Ballengeich Road, tel. 01786/474-933, www.castlecroft-uk.co.uk, castlecroft@gmail.com).

A number of B&Bs offering slightly lower prices line Causewayhead Road, a busy thoroughfare that connects Stirling to the Wallace Monument. From here, it’s a long walk into town (or the Wallace Monument), but the location is handy for drivers (each place has free parking). While this modern residential area lacks charm, it’s convenient.

$$ The Old Tramhouse is the frilliest of the bunch, with five rooms elegantly decorated with a delicate charm (family room, 42 Causewayhead Road, tel. 01786/449-774, mobile 0759-054-0604, www.theoldtramhouse.com, enquiries@theoldtramhouse.com, Alison Cowie). They also have an apartment for up to five people.

$ Craigard B&B has three small, modern, tidy, and proper rooms that offer good value and a shared breakfast table (40 Causewayhead Road, tel. 01786/460-540, mobile 0784-040-1551, www.craigardstirling.co.uk, craigard@hotmail.co.uk, Liz).

$ Springfield Lodge sits at the back end of the residential zone that lines up along Causewayhead Road. It’s across the street from farm fields, giving it a countryside feeling. The four neat rooms fill a spacious modern house (no kids under 6, Easter Cornton Road, tel. 01786/474-332, mobile 0795-469-2412, www.springfieldlodgebandb.co.uk, springfieldlodgebandb@gmail.com, Kim and Kevin).

Stirling isn’t a place to go looking for high cuisine; eateries here tend to be barely satisfying but functional. All of these are open daily unless otherwise noted.

(See “Stirling Center” map, here.)

$$ Unicorn Cafeteria, tucked under the casemates inside the castle, is a decent place for lunch if touring the grounds (same hours as castle).

$$ The Portcullis, just below the castle esplanade, is a pub that aches with history, from its dark, wood-grained bar area to its stony courtyard. The food, like the setting, is old-school. If the restaurant is full, you can also eat at the bar (01786/472-290, 12:00-15:00 & 17:30-20:30).

$$$$ Hermann’s, a block below the castle esplanade, is more dressy, spacious, and homey with a sunny conservatory out back. It serves a mix of Scottish and Austrian food—perfect when you’ve got a hankering for haggis, but your travel partner wants Wiener schnitzel (lunch and dinner, top of Broad Street, tel. 01786/450-632, www.hermanns-restaurant.co.uk).

(See “Stirling Center” map, here.)

Dumbarton Road, at the bottom of town, has a line of cheap eateries (Indian, Asian, cheap buffets) including Blue Lagoon Fish & Chips (11:00-23:00, at Port Street). Among a group of chain pubs and ethnic eateries (Thai and Italian), these three are within about a block of Stirling’s clock tower near King Street in the old town center:

$$ Maharaja is popular for its “authentic Indian cuisine” served in a dressy dining room (39 King Street, tel. 01786/470-728).

$$$ Brea, which means “love” in Gaelic, has a nice Scottish theme, from the menu to the decor to the pop music playing. It’s unpretentious and popular for its modern and tasty dishes. Consider treating first courses like tapas and eating family-style (12:00-21:00, closed for lunch Mon, 5 Baker Street, tel. 01786/446-277).

$$ Nicky-Tams Bar and Bothy is a fun little hangout with an Irish-pub ambience, providing a great place to chat up a local and enjoy some good, basic pub grub. They serve meals from 12:00 to 20:00, then make way for drinking and, often, live music (29 Baker Street, tel. 01786/472-194).

From Stirling by Train to: Edinburgh (2/hour, 1 hour), Glasgow (3/hour, 45 minutes), Pitlochry (5/day direct, 1 hour, more with transfer in Perth), Inverness (6/day direct, 3 hours, more with transfer in Perth). Train info: Tel. 0345-748-4950, www.nationalrail.co.uk.

By Bus to: Glasgow (hourly on #M8, 45 minutes), Edinburgh (every 2 hours on #909, 1 hour). Citylink: tel. 0871-266-3333, www.citylink.co.uk.

The Wallace Monument and the Bannockburn Heritage Centre are just outside of town. Sights within side-trip distance include The Kelpies horse-head sculptures, the Falkirk Wheel boat “elevator,” the stuck-in-time village of Culross, Doune Castle, and the Trossachs National Park.

Commemorating the Scottish hero better known to Americans as “Braveheart,” this sandstone tower—built during a wave of Scottish nationalism in the mid-19th century—marks the Abbey Craig hill on the outskirts of Stirling. This is where, in 1297, William Wallace gathered forces and secured his victory against England’s King Edward I at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. The victory was a huge boost to the Scottish cause, but England came back to beat the Scots the next year. (For more on Wallace, see here.)

Cost and Hours: £10, daily July-Aug 9:30-18:00, April-June and Sept-Oct until 17:00, Nov-March 10:30-16:00, last entry 45 minutes before closing, café at visitors center, tel. 01786/472-140, www.nationalwallacemonument.com. The £1 audioguide basically repeats the posted information.

Getting There: The monument is two miles northeast of Stirling on the A-9, signposted from the city center. Frequent public buses go from the Stirling bus station to the roundabout below the monument (15-minute ride). From there, it’s about a 15-minute hike up to the visitors center, then an additional hike up to the monument. Taxis cost about £8 one-way. From the visitors center parking lot, you’ll need to hike (a steep 10 minutes) or hop on the shuttle bus up the hill to the monument itself (free, departs every 10 minutes).

Visiting the Monument: Buy your ticket either at the visitors center below or the monument above. Then hike or ride the shuttle bus up to the monument’s base. Gazing up, think about how this fanciful 19th-century structure, like so many around Europe in that age, was created and designed to evoke (and romanticize) earlier architectural styles—in this case, medieval Scottish castles. The crown-shaped top—reminiscent of St. Giles’ on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh—and the dynamic sculpture of William Wallace are patriotic to the max.

Climb the tight, stone spiral staircases a total of 246 steps, stopping at each of the three levels to see museum displays. The first level, the Hall of Arms, tells the story of William Wallace and the Battle of Stirling Bridge. Second is the Hall of Heroes, adorned with busts of great Scots—suggesting the debt this nation owes to Wallace. In the middle of the room, ogle Wallace’s five-foot-long broadsword. But it’s not all just hero worship: A thoughtful video presentation on the first level considers the role of Wallace in both Scottish and English history, and raises the point that one person’s freedom fighter is another person’s terrorist. The third level’s exhibits are about the monument itself: why and how it was built.

Finally, you reach the top with stunning views over Stirling, its castle, the winding River Forth, and Stirling Bridge—a 500-year-old stone version that replaced the original wooden one. Looking out from the same vantage point as Wallace, imagine how the famous battle played out. But if you find yourself picturing Braveheart—with berserker Scots, their faces painted blue, running across a field to take on the English cavalry—you have the wrong idea. While that portrayal was cinematically powerful, in reality the battle took place on a bridge in a narrow valley (see sidebar).

Just south of Stirling is the Bannockburn Heritage Centre, commemorating what many Scots view as their nation’s most significant military victory over the invading English: the Battle of Bannockburn, won by a Scottish army led by Robert the Bruce against England’s King Edward II in 1314. The battle memorial is free and always open. The Heritage Centre “Battle Game” is an interactive techy experience, with 3-D screens and a re-creation that basically reduces the battle to a video game.

Cost and Hours: Memorial-free, always open, Heritage Centre and “Battle Game”-£11.50, daily 10:00-17:30, Nov-Feb until 17:00, café, tel. 0844/493-2139, www.battleofbannockburn.com. If interested in the 3D experience, call or visit the website to book a time.

Getting There: Bannockburn is two miles south of Stirling on the A-872, off the M-80/M-9. For nondrivers, it’s an easy bus ride from the Stirling bus station (8/hour, 15 minutes).

Background: In simple terms, Robert the Bruce—who was first and foremost a politician—found himself out of political options after years of failed diplomatic attempts to make peace with the strong-arming English. William Wallace’s execution left a vacuum in military leadership, and eventually Robert stepped in, waging a successful guerrilla campaign that came to a head as young Edward’s army marched to Stirling. Although the Scots were greatly outnumbered, their strategy and use of terrain at Bannockburn—with its impossibly twisty stream presenting a natural barrier for the invading army—allowed them to soundly beat the English and drive Edward out of Scotland...for the time being. (For more about Robert the Bruce, see here.)

Visiting the Heritage Centre: There are no historic artifacts here. First, you’ll spend 30 minutes learning about the emerging battle from the perspective of both sides, and getting familiar with the characters and weaponry. Then, when your time arrives, you enter the “battle room,” huddling with a dozen or so others (divided into two sides—English and Scots) around a large, interactive 3D map of the battleground. On screen, the “Battle Master” leads the group, but you get to call the shots as the battle unfolds.

Monument and Statue of Robert the Bruce: Leaving the center, hike out into the field behind, where you can see a monument to those lost in the fight. Nearby, on a plinth, stands an equestrian statue of Robert the Bruce.

Two engaging landmarks sit just outside the town of Falkirk, 12 miles south of Stirling. Taken together, The Kelpies and the Falkirk Wheel offer a welcome change of pace from Scottish countryside kitsch. These flank Falkirk’s otherwise unexciting town center, about a 5-mile, 20-minute drive apart. Driving between the two is a riddle of roundabouts. Think of it as fun: Carefully follow the brown signs and you’ll eventually get there. (Ask for a flier illustrating directions between them at either site.)

Unveiled in 2014 and standing over a hundred feet tall, these two giant steel horse heads have quickly become a symbol of this town and region. They may seem whimsical, but they’re rooted in a mix of mythology and real history: Kelpies are magical, waterborne, shape-shifting sprites of Scottish lore, who often took the form of a horse. And historically, horses—the ancestors of today’s Budweiser Clydesdales—were used as beasts of burden to power Scotland’s industrial output. These statues stand over old canals where hardworking horses towed heavily laden barges. But if you prefer, you can just forget all that and ogle the dramatic, energy-charged statues (particularly thrilling to Denver Broncos fans) that make for an entertaining photo op. A café nearby sells drinks and light meals, and a free visitors center shows how the heads were built. A 30-minute guided tour through the inside of one of the great beasts shows how they’re supported by a sleek steel skeleton: 300 tons of steel apiece, sitting upon a foundation of 1,200 tons of steel-reinforced concrete, and gleaming with 990 steel panels.

Cost and Hours: Always open and free to view (£3 to park); visitors center open daily 9:30-17:00. Tours-£7.50, daily at the bottom of every hour 10:30-16:30, fewer tours Oct-March, tel. 01324/506-850, www.thehelix.co.uk.

Getting There: The Kelpies are in a park called The Helix, just off the M-9 motorway—you’ll spot them looming high over the motorway as if inviting you to exit. For a closer look, exit the M-9 for the A-905 (Falkirk/Grangemouth), then follow Falkirk/A-904 and brown Helix Park & Kelpies signs.

At the opposite end of Falkirk stands this remarkable modern incarnation of Scottish technical know-how. You can watch the beautiful, slow-motion contraption as it spins—like a nautical Ferris wheel—to efficiently shuttle ships between two canals separated by 80 vertical feet.

Cost and Hours: Wheel is free to view, visitors center open daily 10:00-17:30, park open until 20:00, shorter hours Nov-mid-March; cruises run about hourly and cost £13, call or go online to check schedule and book your seat, tel. 0870-050-0208, www.thefalkirkwheel.co.uk.

Getting There: Exit the M-876 motorway for A-883/Falkirk/Denny, then follow brown Falkirk Wheel signs. Parking is free and a short walk from the wheel.

Background: Scotland was a big player in the Industrial Revolution, thanks partly to its network of shipping canals (including the famous Caledonian Canal—see here). Using dozens of locks to lift barges up across Scotland’s hilly spine, these canals were effective...but slow.

The 115-foot-tall Falkirk Wheel, opened in 2002, is a modern take on this classic engineering challenge: linking the Forth and Clyde Canal below with the aqueduct of the Union Canal, 80 feet above. Rather than using rising and lowering water through several locks, the wheel simply picks boats up and—ever so slowly—takes them where they need to go, like a giant waterborne elevator. In the 1930s, it took half a day to ascend or descend through 11 locks; now it takes only five minutes.

The Falkirk Wheel is the critical connection in the Millennium Link project, an ambitious £78 million initiative to restore the long-neglected Forth and Clyde and Union canals connecting Edinburgh and Glasgow. Today this 70-mile-long aquatic connection between Scotland’s leading cities is a leisurely traffic jam of pleasure craft, and canalside communities have been rejuvenated.

Visiting the Wheel: Twice an hour, the wheel springs (silently) to life: Gates rise up to seal off each of the water-filled gondolas, and then the entire structure slowly rotates a half-turn to swap the positions of the lower and upper boats—each of which stays comfortably upright. The towering structure is not only functional, but beautiful: The wheel’s elegantly sweeping shape—with graceful cogs and pointed tips that slice into the water as they spin. It’s strangely exciting to witness this.

The visitors center has a cafeteria (with a fine view of the wheel) and a shop, but no information about the wheel. The Falkirk TI is just steps away. The park around the canal is cluttered with trampolines, laser tag, and other family amusements.

Riding the Wheel: Each hour, a barge takes 96 people (listening to a recorded narration explaining everything) into the Falkirk Wheel for the slow and graceful ride. Once at the top, the barge cruises a bit of the canal. The slow-motion experience lasts 50 minutes.

This time warp of a village, sitting across the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh (about a 30-minute drive from Stirling), is a perfectly preserved artifact from the 17th and 18th centuries. If you’re looking to let your pulse slow, stroll through a steep and sleepy village, and tour a creaky old manor house, Culross is your place. Filmmakers often use Culross to evoke Scottish villages of yore (you’ve seen it in everything from Captain America: The First Avenger to Outlander). While not worth a long detour, it’s a workable stop for drivers connecting Edinburgh to either the Stirling area or St. Andrews (free parking lots flank the town center—an easy, 5-minute waterfront stroll away).

The story of Culross (which locals pronounce KOO-russ) is the story of Sir George Bruce, who, in the late 16th century, figured out a way to build coal mines beneath the waters of the Firth of Forth. The hardworking town flourished, Bruce built a fine mansion, and the town was granted coveted “royal burgh” status by the king. But several decades later, with Bruce’s death and the flooding of the mines, the town’s fortunes tumbled—halting its development and trapping it as if in amber for centuries. Rescued and rehabilitated by the National Trust for Scotland, today the entire village feels like one big open-air folk museum.

The main sightseeing attraction here is the misnamed Culross “Palace,” the big-but-creaky, half-timbered home of George Bruce (£10.50, daily 11:00-17:00 in summer, Sat-Mon only in off-season, closed Nov-March, tel. 01383/880-359, www.nts.org.uk/culross). Buy your ticket at the office under the Town Hall’s clock tower, pick up the included audioguide, then head a few doors down to the ochre-colored palace. Following a 10-minute orientation film, you’ll walk through several creaky floors to see how a small town’s big shots lived four centuries ago. Docents in each room are happy to answer questions. You’ll see the great hall, the “principal stranger’s bedchamber” (guest room for VIPs), George Bruce’s bedroom and stone strong room (where he stored precious—and flammable—financial documents), and the highlight, the painted chamber. The wood slats of its barrel-arched ceiling are painted with whimsical scenes illustrating Scottish virtues and pitfalls. You can also poke around the densely planted, lovingly tended garden out back.

A 45-minute guided town walk takes place for a small fee (3/day, check palace website for schedule).

The only other real sight, a steep hike up the cobbled lanes to the top of town, is the partially ruined abbey. While there are far more evocative ruins in Scotland, it’s fun to poke into the stony, mysterious-feeling interior of this church. But the stroll up the town’s cobbled streets past pastel houses, with their carefully tended flower boxes, is even better than the church itself.

The village of Doune (pronounced “doon”) is just a 15-minute drive north of Stirling. While there’s not much to see in town, on its outskirts is a pair of attractions: a castle and a distillery. In the village of Doune itself, notice the town seal: a pair of crossed pistols. Aside from its castle and whisky, the town is known for its historic pistol factory. Locals speculate that the first shot of the American Revolution was fired with a Doune pistol.

Getting There: Bus #59 runs from Stirling to Doune and the distillery (just outside Doune). Drivers head to Doune, then follow castle signs on pretty back roads from there.

Doune Castle is worth considering for its pop-culture connections: Most recently, Doune stands in for Castle Leoch in the TV series Outlander. But well before that, parts of Monty Python and the Holy Grail were filmed here. And, while the castle may underwhelm Outlander fans (only some exterior scenes were shot here), Python fans—and anyone who appreciates British comedy—will be tickled by the included audioguide, narrated by Python troupe member Terry Jones (featuring sound clips from the film). The audioguide also has a few stops featuring Sam Heughan of Outlander. (If you’re not into Python or Outlander, Scotland has better castles to visit.)

Cost and Hours: £6, daily April-Sept 9:30-17:30, Oct-March 10:00-16:00, tel. 01786/841-742.

Visiting the Castle: Buy your ticket and pick up the 45-minute audioguide, which explains that the castle’s most important resident was not Claire Randall or the Knights Who Say Ni, but Robert Stewart, the Duke of Albany (1340-1420)—a man so influential he was called the “uncrowned king of Scotland.” You’ll see the cellars, ogle the empty-feeling courtyard, then scramble through the two tall towers and the great hall that connects them. The castle rooms are almost entirely empty, but they’re brought to life by the audioguide. You’ll walk into the kitchen’s ox-sized fireplace to peer up the gigantic chimney, and visit the guest room’s privy to peer down the medieval toilet. You’ll finish your visit at the top of the main tower, with 360-degree views that allow you to fart in just about anyone’s general direction.

This big, attractive red-brick industrial complex (formerly a cotton mill) sits facing the river just outside of Doune. While Deanston has long been respected for its fruity, slightly spicy Highland single-malt whisky, the 2012 movie The Angels’ Share, filmed partly at this distillery, helped put it on the map for tourists. The complex boasts a slick visitors center that’s open for tours. On the 50-minute visit, you’ll see the equipment used to make the whisky and enjoy a sample. (For more on whisky and the distillation process, see here.) A bit more corporate-feeling than some of my favorite Scottish distilleries, Deanston has the advantage of being handy to Stirling.

Cost and Hours: £9 or £12 depending on number of tastings, tours depart at the top of each hour daily 10:00-16:00 (last tour), best to call ahead to reserve, tel. 01786/843-010, www.deanstonmalt.com.

Within about an hour’s drive of half the population of Scotland is the country’s most popular national park. Though it’s a single park, it takes its name from two separate areas: The famous lake called Loch Lomond and, just to the east, the Trossachs—a hilly terrain that pleases hikers and joyriders. The Highland Boundary Fault—the geologic line separating the flat Lowlands from the rugged Highlands—runs right through the middle of this area, and in several places you can actually see the terrain in transition.

To be honest, the charms of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs are subtle. Scottish scenery crescendos dramatically as you head north (at Glencoe, the Cairngorms, and the Isle of Skye, for starters). But this area’s proximity to Stirling and Glasgow—and its many entertaining connections to Scottish history, literature, and folk culture—make it worth knowing about. For those on a quick visit to Scotland’s Central Belt, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs offer a glimpse of “the Highlands in miniature.”

Twenty-four miles long and speckled with islands, Loch Lomond is Great Britain’s biggest lake by surface area, and second in volume only to Loch Ness. Thanks largely to its easy proximity to Glasgow (about 15 miles away), this scenic lake is a favorite retreat for Scots as well as foreign tourists. The southernmost of the Munros, Ben Lomond (3,196 feet), looms over the eastern bank.

Loch Lomond’s biggest claim to fame is its role in a beloved folk song: “Ye’ll take the high road, and I’ll take the low road, and I’ll be in Scotland afore ye... For me and my true love will never meet again, on the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Lomond.” As you’ll now be humming that all day (you’re welcome), here’s one interpretation of the song’s poignant meaning: Celtic culture believes that fairies return the souls of the deceased to their homeland through the soil. After the disastrous Scottish loss at the Battle of Culloden, Jacobite ringleaders were arrested and taken for trial in faraway London. In some cases, accused pairs were given a choice: One of you will die, and the other will live. The song is a bittersweet reassurance, sung from the condemned to the survivor, that the soon-to-be-deceased will take the spiritual “low road” back to his Scottish homeland—where his soul will be reunited with the living, who will return on the physical “high road” (over land).

Visiting Loch Lomond: There’s not much to see, aside from some lochside scenery. You can get a fair dose simply driving by. People traveling from Glasgow toward Oban (or other points north) will get a good look at the loch’s west bank as they follow the A-82 north (see “Glasgow to Oban Drive” on here).

To see the east bank of the lake, it’s an easy detour from the Trossachs loop described next, or from Glasgow. Take the A-811 west from Stirling, or the A-809 north from Glasgow, to the village of Drymen (DRIM-men). From here, carry on westward (along the B-837) to Balmaha. In this wide spot in the road, you’ll find a visitors center with free geology and wildlife exhibits and advice about various hikes in the region. One easy and popular option is the ascent to Craigie Fort viewpoint (1 mile, 45 minutes round-trip), offering views over the southern part of the lake. For a more ambitious hike, you can follow part of the West Highland Way up to Conic Hill (2.5 miles, 3 hours round-trip).

The hills-and-lochs terrain of the Trossachs, just northwest of Stirling (and due north of Glasgow), is a gently scenic, tourist-clogged corner of Highlands beauty. While the views here pale in comparison to more scenic areas farther north, this well-trod route is packed with interesting footnotes in Scottish history—from Rob Roy to Sir Walter Scott to the Beatles. The Trossachs makes for an easy, pretty spin close to Glasgow or Stirling, but can also be used as a slow-but-scenic connection to points in northern and eastern Scotland (see the options at the end of this drive). I’ve lightly narrated this loop in a clockwise order, coming from Stirling. But you can go in either direction, and begin or end wherever you like. I’ve focused on real history rather than silly legends...but sometimes the myths are hard to resist.

Self-Guided Driving Tour: From Stirling, head west on the A-84, then turn off to the left onto the A-873 (marked for Thornhill; watch for brown Trossachs signs). Carry on through Thornhill and then, in the village of Blairhoyle, turn left onto the A-81.

Self-Guided Driving Tour: From Stirling, head west on the A-84, then turn off to the left onto the A-873 (marked for Thornhill; watch for brown Trossachs signs). Carry on through Thornhill and then, in the village of Blairhoyle, turn left onto the A-81.

Soon you’ll pass the Lake of Menteith. Many Scots are quick to point out that this is the only “lake” (as opposed to “loch”) in all of Scotland, and have cooked up an explanation: Its namesake, Sir John Menteith, was a Scot who betrayed William Wallace, leading to his arrest and execution. To punish the traitor, “loch” became “lake.” But, like most trumped-up Trossachs legends, this is bogus: The “lake” is likely derived from the Lowland Scots word laich—meaning simply “low place.”

Continue along the A-81, then bear right onto the A-821 to Aberfoyle. Approaching the town, notice the landscape heaving up just beyond it—you can actually see where the Highland Boundary Fault marks the start of the Highlands. The town itself is attractive, if something of a tour bus hell—with more parking lot than town. But it’s a convenient place to take a break and grab picnic supplies. At the corner of the parking lot, the Scottish Wool Centre is a tacky tourist mall with a few free attractions out front that are worth a peek: sheep, noisy goats, birds of prey, and a fun little sheepdog demonstration, in which the clever dogs herd geese on a virtual “tour of Scotland.” Across the parking lot, the TI has free Wi-Fi and a small exhibit touting Aberfoyle’s literary connections: Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake was inspired by nearby Loch Katrine (which we’ll reach soon). This was also the home of Robert Kirk, who (in 1691) wrote The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns, and Fairies, which remains the definitive compendium of Scottish superstition. Soon after, Kirk died mysteriously in a forest glen supposedly inhabited by fairies. (Locals love to share stories, theories, and superstitions about Kirk.)

Leaving Aberfoyle, carry on north along the A-821, following a twisty road called the Duke’s Pass. This was built by the Duke of Montrose (the villain of the Rob Roy story) to access his mountain estates and to levy tolls. You’ll wind your way up into a thickly forested hillscape; watch on the right for the turnoff for the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park visitors center. Here you can get maps and hiking advice, and peruse good exhibits on local geology and wildlife—including live cameras showing osprey nests. They share a parking lot with Go Ape, a popular zip-line and high-ropes course (best to book ahead, full course takes 2-3 hours, www.goape.co.uk).

As you crest the Duke’s Pass, you’ll get a small taste of the Highland moor terrain. For a good look at this landscape (and a parking lot with a handy viewpoint), pull off on the right at the start of the Three Lochs Forest Drive. You’re surrounded by heather—the scrubby plant (with vibrant purple flowers in the late summer) that blankets much of the Highlands. The oldest pines around you are mostly Scotch (or “Scots”) pines; more recently, these have been replaced by faster-growing pines that are better for harvesting. Meanwhile, the deciduous trees (with red berries or white flowers, depending on the season) are rowan trees, also called “mountain ash.” Superstitious Highlanders believe that rowans keep witches away and prevent fairies from switching out babies for changelings. If you’re bothered by the distant sight of wind farms from this viewpoint, you can commiserate with Donald Trump—before he became president he lobbied the Scottish government to outlaw these structures within sight of his Scottish golf courses.

Back on the main road, you’ll start working your way downhill. On your right are glimpses of Loch Drunkie. Just ignore tour guides who tell you this was named for the practice of chugging and dumping illegal homebrew whisky here when the police showed up.

Farther down, you’ll pass briefly along the banks of Loch Achray. Across the lake is the former Trossachs Hotel, which has hosted everyone from Queen Victoria to the Beatles. In the Fab Four’s landmark 1964 tour around the UK, they’d do big shows in cities, then retreat to countryside getaways like this one.

At the end of Loch Achray, turn off on the left for Loch Katrine. Park in the big pay lot and stretch your legs. While this corner of the loch is nothing special, the scenery opens up if you follow its shore. You have several options: You can walk along the easy, paved lochside trail; you can pay for a boat trip (www.lochkatrine.com); or you can rent a bike (but be warned that the 14-mile path to the end of the lake gets increasingly hillier—consider taking a bike on the boat one way, and pedaling back; www.katrinewheelz.co.uk). Loch Katrine has various claims to fame. Sir Walter Scott’s epic poem The Lady of the Lake was set here, and extols the beauties of this corner of the Trossachs. Sir Walter Scott is also the name of the steamship that does sightseeing cruises around the loch; while steamships like this were once a common sight on Scottish lochs, this is the last one still in operation. At the boat dock, big displays explain how Loch Katrine was the home of Rob Roy (see sidebar). Loch Katrine is also a primary water supply for Glasgow. In 1885, engineers harnessed the power of gravity to pipe the clean mountain waters into the big city. (Glaswegians of the time—accustomed to extremely polluted well water—were unimpressed. As one joke goes, a Glaswegian poured his first glass of water, eyed it suspiciously, and said, “It’s got nae color, nae taste—nae good!”) And finally, the US president’s theme song also has a connection to this unassuming Scottish loch: “Hail to the Chief” came from a musical based on Scott’s Lady of the Lake. In 1815, it was played to commemorate George Washington and to celebrate the end of the War of 1812, and the tradition stuck.

When you’re done at Loch Katrine, return to the main A-821 and head toward Callander. You’ll go along the other bank of Loch Achray (and get a closer look at the former Trossachs Hotel—now a timeshare). Then you’ll pass through Brig O’Turk (Gaelic for “Bridge of the Wild Boar”) and drive along Loch Venachar before reaching a junction with the A-84. It’s time to make your decision: Head north for more scenery and access to Loch Tay (Crannog Centre, Kenmore), Pitlochry, and other sights. Or head south for a speedy return to Stirling, by way of Callander and Doune Castle. Both options are outlined next.

To the North: If you head north on the A-84, you’ll pass another pretty loch (Lubnaig), and soon after, you’ll see the turnoff for Balquhidder. Fans of Rob Roy—or anyone named MacGregor—may want to take the two-mile detour (on single-track roads) to Balquhidder’s humble stone church. In the kirkyard, look for the grave of the famous MacGregor clan chieftain. Rob Roy lived most of his life in these hills overlooking Loch Voil (visible in the distance). Back on the main A-84, carry on north (in Lochearnhead, it becomes the A-85); eventually you’ll reach the junction with the A-827. From here, you can stick with the main A-85 all the way to Oban. Or you can turn right onto the A-827 (toward Killin) to reach the dramatic Falls of Dochart, which tumble through a tiny village, and then follow the north bank of Loch Tay to Kenmore and the Crannog Centre; farther along the A-827, you’ll rejoin the main A-9 highway, which heads north to Pitlochry and several other attractions on the way up to Inverness. (For details on all of these sights, see the Eastern Scotland chapter.) Turning south on the A-9 zips you back toward Perth, then Stirling.

To the South: To complete our loop more directly, head south on the A-84. Just after you make the turn, watch on the left for the Wool Center, with a pair of hairy coos (shaggy Highland cattle) around back who love to pose for photos. Soon after, you’ll pass through Callander, which feels like a very slightly less touristy version of Aberfoyle. Carrying on through town on the A-84, you’ll pass through the village of Doune, where you can stop off for a tour of Doune Castle and/or the Deanston Distillery (both described earlier in this chapter). Stirling is just down the road.