CHAPTER

6

POLICY FORMULATION: DEVELOPMENT OF LEGISLATION

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

- describe the policy formulation phase of policymaking;

- list and describe the steps in the choreography of legislation development;

- discuss the drafting of legislative proposals, including the forms they can take;

- discuss the legislative committee and subcommittee structure of Congress;

- identify and describe the roles of the key congressional committees and subcommittees with health policy jurisdiction; and

- describe the federal and state budget legislative development processes.

As we noted in chapters 4 and 5, the formulation phase of health policymaking is made up of two distinct and sequential parts: agenda setting and legislation development. Chapter 5 focused on agenda setting; in this chapter we turn our attention to the development of legislation. Understanding the agenda setting process and the development of legislation is foundational to appreciating the policymaking process fully.

As with the discussion of agenda setting in chapter 5, this discussion of legislation development is confined almost exclusively to its occurrence at the federal level of government. However, state and local governments develop legislation using a similar approach. The problems for which legislation is developed differ at each level, but the general process framework is remarkably similar.

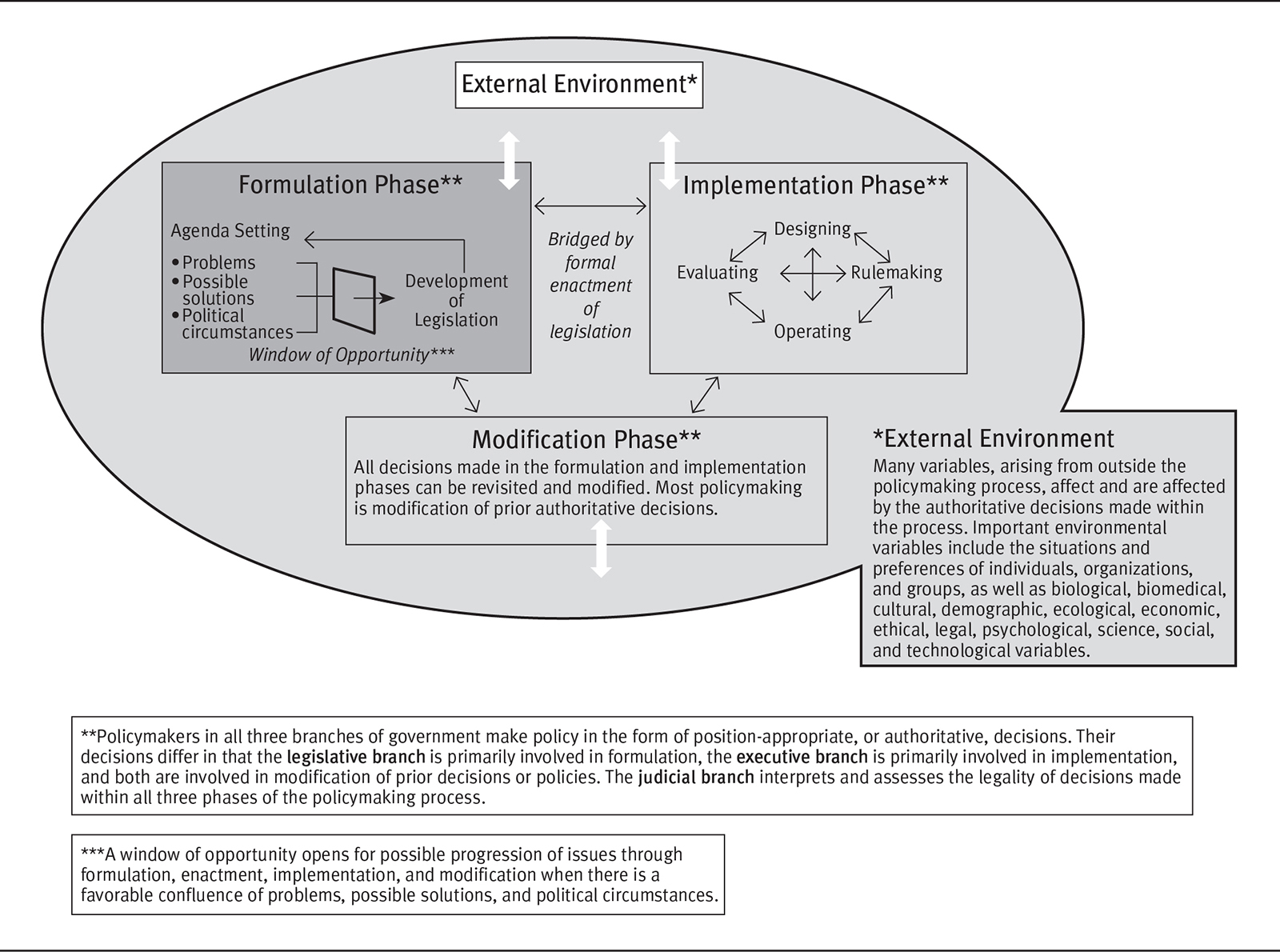

The result of the entire formulation phase of policymaking is public policy in the form of new public laws or amendments to existing laws. New health-related laws or amendments originate from the policy agenda. Recall that the health policy agenda is established through the interactions of a diverse array of problems, possible solutions to those problems, and the dynamic political circumstances that relate to the problems and to their potential solutions. Combinations of problems, potential solutions, and political circumstances that achieve priority on the policy agenda move on to the next component of the policy formulation phase: legislation development (see the darkly shaded portion of exhibit 6.1).

EXHIBIT 6.1 Policymaking Process: Development of Legislation in the Formulation Phase

Long Description

The details of the diagram are as follows:

The formulation phase, implementation phase, and the modification phase are connected to one another in the external environment. The formulation phase shows the agenda settings: problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances leading to a window of opportunity for the development of legislation which again leads to the agenda setting.

The implementation phase shows designing, rulemaking, operating, and evaluating are interconnected to one another. The formulation phase and the implementation phase are bridged by formal enactment of legislation.

The modification phase reads “All decisions made in the formulation and implementation phases can be revisited and modified. Most policymaking is modification of prior authoritative decisions.”

The external environment reads “Many variables, arising from outside the policymaking process, affect and are affected by the authoritative decisions made within the process. Important environmental variables include the situations and preferences of individuals, organizations, and groups, as well as biological, biomedical, cultural, demographic, ecological, economic, ethical, legal, psychological, science, social, and technological variables.”

The formulation phase, implementation phase, and modification phase reads “Policymakers in all three branches of government make policy in the form of position-appropriate, or authoritative, decisions. Their decisions differ in that the legislative branch is primarily involved in formulation, the executive branch is primarily involved in implementation, and both are involved in modification of prior decisions or policies. The judicial branch interprets and assesses the legality of decisions made within all three phases of the policymaking process.”

The window of opportunity reads “A window of opportunity opens for possible progression of issues through formulation, enactment, implementation, and modification when there is a favorable confluence of problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances.”

The laws and amendments to existing laws that result from the formulation phase of policymaking are tangible. They can be seen and read in a number of places (see appendix 2.2). The US Constitution prohibits the enactment of laws that are not specifically and directly made known to the people who are to be bound by them. In practice, federal laws are published immediately on enactment. Of course, it is incumbent on people who might be affected by laws to know of them and to be certain that they understand the effects of those laws. Health professionals should devote time and attention to the potential and real impact of relevant laws and amendments and be aware of the continually evolving nature of health policy.

At the federal level, enacted laws are first printed in pamphlet form called slip law. Later, laws are published in the US Statutes at Large and eventually incorporated into the US Code. The Statutes at Large, published annually, contains the laws enacted during each session of Congress. In effect, it is a compilation of all laws enacted in a particular year. The US Code is a complete compilation of all the nation’s laws. A new edition of the code is published every six years, with cumulative supplements published annually. Federal public laws can be found and reviewed at www.congress.gov.

The Choreography of Legislation Development

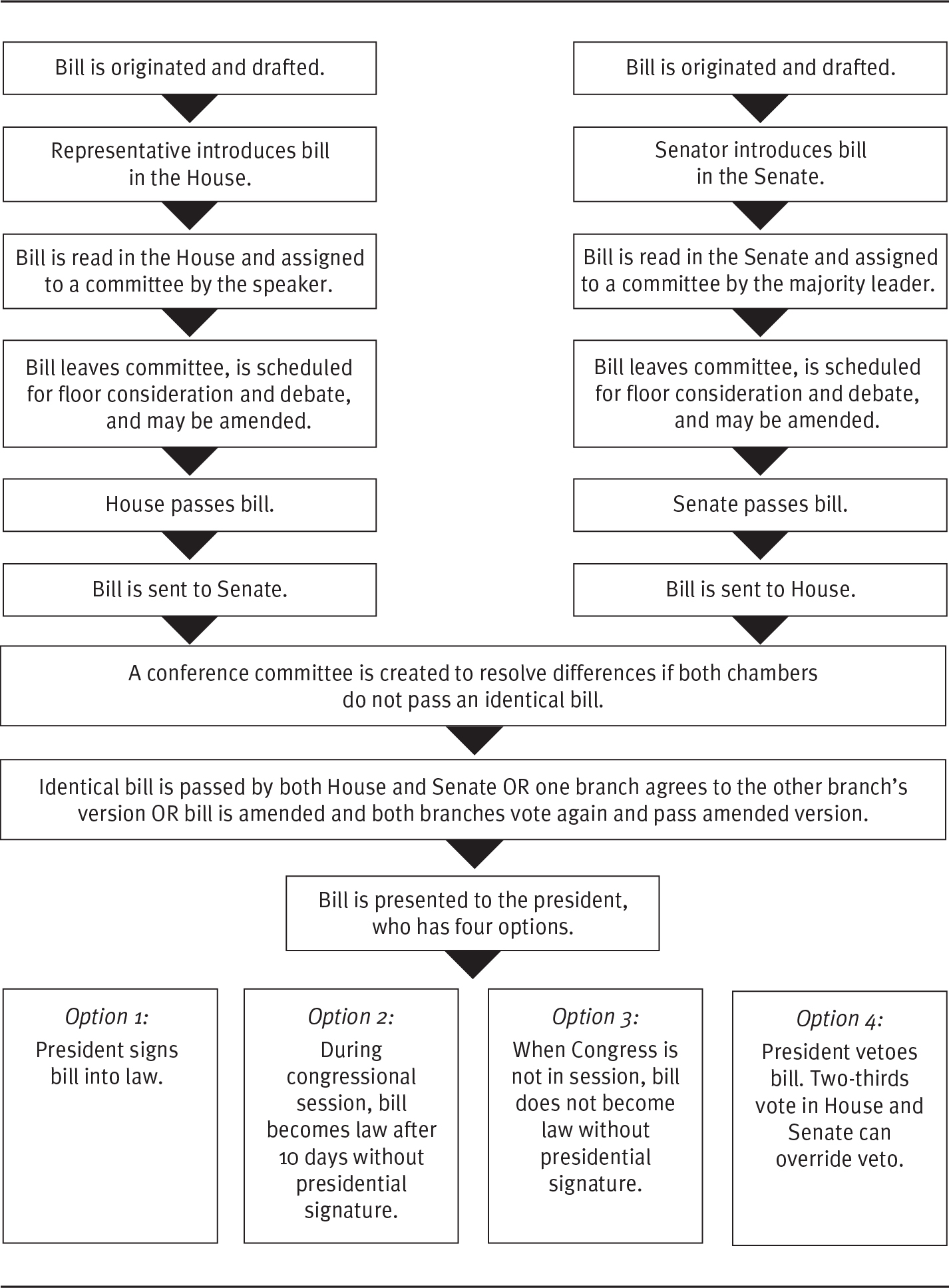

Development of legislation is the point in policy formulation at which specific legislative proposals, which are characterized in chapter 5 as hypothetical or unproved potential solutions to the problems they are intended to address, advance through a series of steps that can end in new or amended public laws. These steps, not unlike those of a complicated dance, are specified or choreographed. The steps followed at the federal level are shown schematically in exhibit 6.2. A variation of these steps was briefly introduced and described in chapter 3. Only when all of the steps are completed does a new public law or, far more typically, an amendment to a previously enacted law, result. The steps that make up the development of legislation activity provide the framework for most of the discussion in this chapter.

EXHIBIT 6.2 The Steps in Legislation Development

Long Description

The details of the flow diagram are as follows:

The flow on the left, lists the steps involved in the passage of the bill to the senate: bill is originated and drafted; Representative introduces bill in the House; Bill is read in the House and assigned to a committee by the speaker; Bill leaves committee, is scheduled for floor consideration and debate, and may be amended; house passes bill; bill is sent to senate.

The flow on the left, lists the steps involved in the passage of the bill to the house: bill is originated and drafted; Senator introduces bill in the senate; Bill is read in the senate and assigned to a committee by the majority leader; Bill leaves committee, is scheduled for floor consideration and debate, and may be amended; senate passes bill; bill is sent to house.

The bill from the house and senate follows the following steps:

A conference committee is created to resolve differences if both chambers do not pass an identical bill; identical bill is passed by both House and Senate OR one branch agrees to the other branch’s version OR bill is amended and both branches vote again and pass amended version; and bill is presented to the president, who has four options. The four options are:

- President signs bill into law.

- During congressional session, bill becomes law after 10 days without presidential signature.

- When Congress is not in session, bill does not become law without presidential signature.

- President vetoes bill. Two-thirds vote in House and Senate can override veto.

Source: Adapted from J. B. Teitelbaum and S. E. Wilensky, 2013, Essentials of Health Policy and Law, 2nd ed., Burling, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. www.jblearning.com. Reprinted with permission.

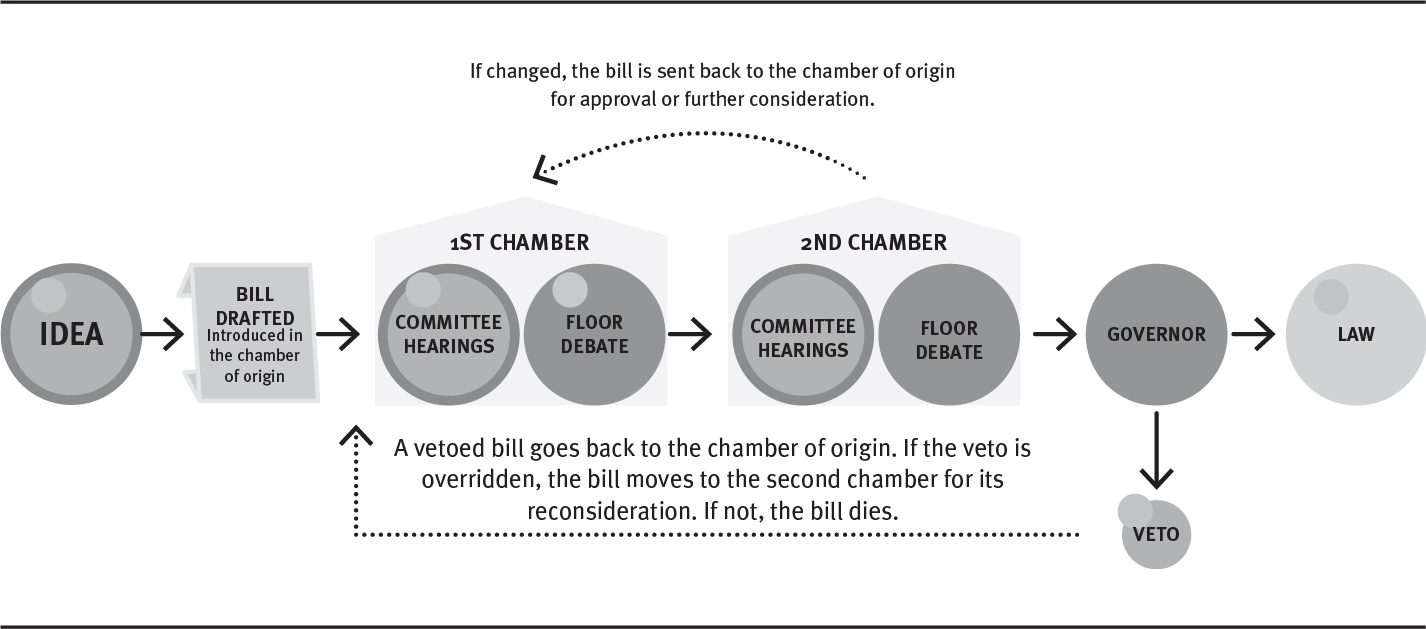

Legislation development begins with the origination of ideas for legislation and extends through the enactment of some of those ideas into law or the amendment of existing laws. The steps of this process apply equally whether the resulting legislation is a new law or an amendment. Sullivan (2007) provides an extensive description of the steps through which federal legislation is developed. Similarly, most states include descriptions of their legislative processes on their websites. For example, the Kansas Legislature publishes a PDF highlighting the process (Kansas Legislature 2019). Exhibit 6.3 illustrates the generic steps in the state legislative process.

EXHIBIT 6.3 State Legislative Process

Long Description

The flow diagram is explained as follows:

- The idea is drafted as a bill and introduced in the chamber of origin after which it passes the first chamber which has committee hearings and floor debate.

- From the first chamber the bill moves to the second chamber which also has committee hearings and floor debate.

- If the bill is changed in the second chamber, the bill is sent back to the chamber of origin for approval or further consideration.

- From the second chamber the bill moves to the Governor. The governor either approves and the bill becomes a law or the governor veto the bill.

- A vetoed bill goes back to the chamber of origin. If the veto is overridden, the bill moves to the second chamber for its reconsideration. If not, the bill dies.

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures (2020).

At the federal level, the path through which legislation is developed begins with ideas for proposed legislation or bills in the agenda-setting stage, extends through formal drafting of legislative proposals and several other steps, and culminates in the enactment of laws derived from some of the proposals. In practice, only a fraction of the legislative proposals that are formally introduced in a Congress—the two annual sessions spanning the terms of office of members of the House of Representatives—are enacted into law. For example, the 116th Congress spanned the period from January 3, 2019, to January 3, 2021. (Refer to exhibit 4.2 for details regarding the number of bills introduced and the percentage that become law.) Proposals that are not enacted by the end of the congressional session in which they were introduced die and must be reintroduced in the next Congress to be considered further.

As the bridge between policy formulation and implementation (shown in exhibit 6.1), formal enactment of proposed legislation into new or amended law represents a significant transition between these two phases of the overall public policymaking process. The focus in this chapter is on ways in which public laws are developed and enacted in the policymaking process; their implementation is discussed in chapter 7.

As we described in chapter 5, individuals, health-related organizations, and the interest groups to which they belong are instrumental in the agenda setting that precedes legislation development. They also actively participate in the development of legislation: Once a health policy problem or issue achieves an actionable place on the policy agenda and moves to the next stage of policy formulation—development of legislation—those with concerns and preferences often continue to seek to exert influence.

Individuals and health-related organizations and interest groups can participate directly in originating ideas for legislation, helping with the actual drafting of legislative proposals, and attending the hearings sponsored by legislative committees. When competing bills seek to address a problem, those with interests in the problems align themselves with favored legislative solutions and oppose those they do not favor. The following sections present a detailed discussion of the steps in legislation development at the federal level, although much of this information also applies to legislative processes in the states. The following box highlights a vivid example of this phenomenon.

The 21st Century Cures Act: A Legislative Grab Bag

In chapter 5, we discussed how the confluence of problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances can combine to create a window of opportunity for legislation to be written and enacted intended to address the problem. Sometimes these events occur when multiple issues are incorporated into a single piece of legislation; this bill may overcome the political controversy associated with the solutions for each individual problem. This technique represents not merely the confluence of problems, political circumstances, and potential solutions for one problem, but for multiple problems. Put another way, sometimes the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-255) is an example of this phenomenon, and it is yet another significant (and, at more than 900 pages, massive) piece of healthcare-related legislation. Brief summaries can be found in four of the summaries of federal legislation in appendix 1.3: “Food and Drug Safety,” “Behavioral and Developmental Health,” “System Infrastructure,” and “Access to Care.” As you can see, this bill dealt with four discrete topics. Moreover, this legislation enjoyed wide bipartisan support, passing the House 392–26 and the Senate 94–5.

The success of this legislation lies in the fact that it became a legislative grab bag. The final bill included a number of controversial ideas. Indeed, most of its elements, standing alone, would face a more difficult legislative path for either lack of salience or intensity of conflict. By incorporating multiple problems along with multiple solutions, the positive response by some policymakers to their favored issues overcame their negative reaction to one (or more) of the other problems.

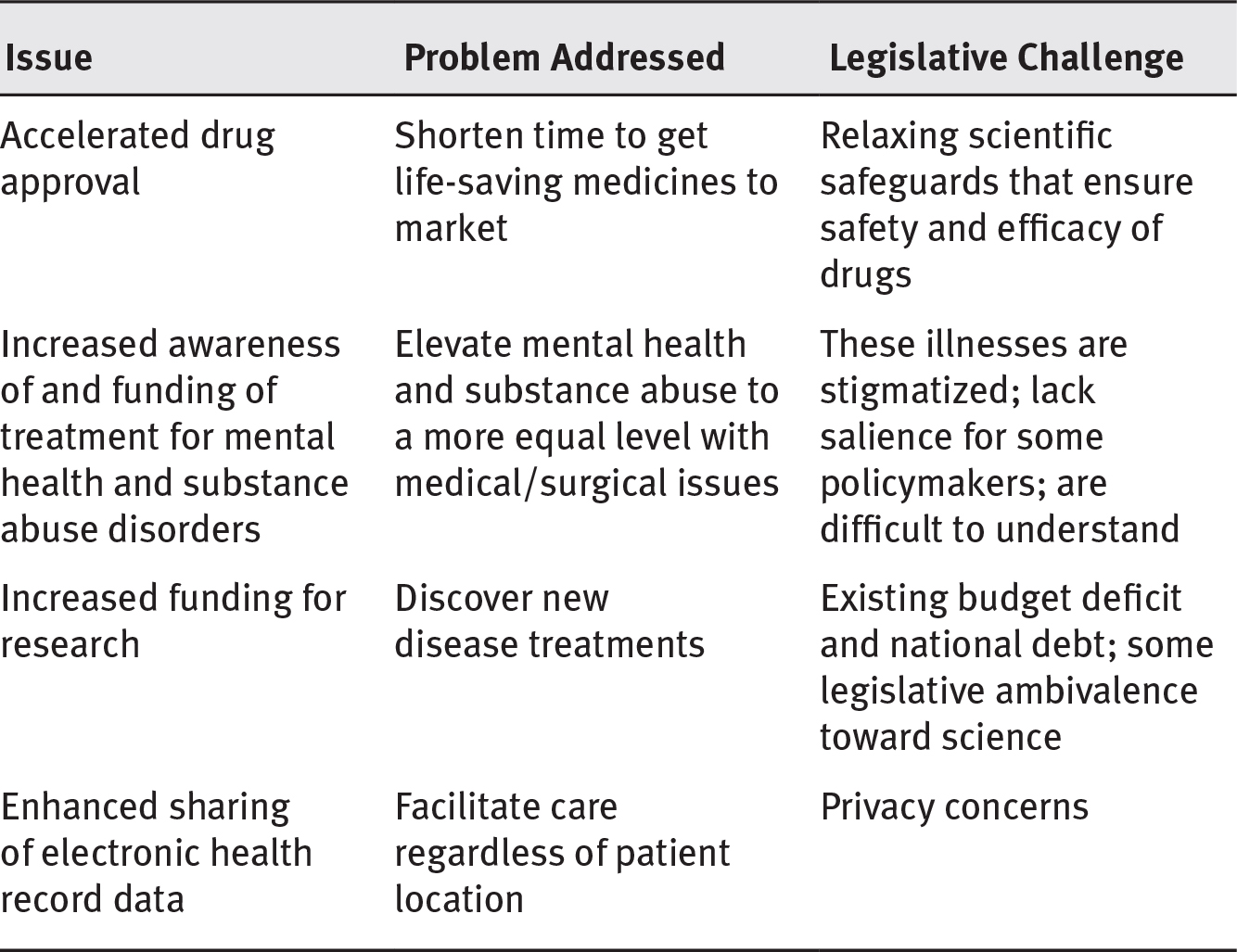

As noted in chapter 5, conflictive issues that create intense disagreements among interest groups, or those that pit the interests of groups against the larger public interest, face problematic legislative paths. Legislation with relatively low salience and high conflict is unlikely to be enacted. A brief look at a few of the factors related to certain issues included in the 21st Century Cures Act are shown in exhibit 6.4.

EXHIBIT 6.4 Selected Issues in the 21st Century Cures Act

Long Description

The table lists the issues, problems addressed, and legislative challenge and they are as follows:

- Accelerated drug approval; Shorten time to get life-saving medicines to market; and relaxing scientific safeguards that ensure safety and efficacy of drugs.

- Increased awareness of and funding of treatment for mental health and substance abuse disorders; elevate mental health and substance abuse to a more equal level with medical/surgical issues; and these illnesses are stigmatized; lack salience for some policymakers; are difficult to understand.

- Increased funding for research; discover new disease treatments; and existing budget deficit and national debt; some legislative ambivalence toward science.

- Enhanced sharing of electronic health record data; facilitate care regardless of patient location; and privacy concerns.

The initial version of the bill introduced in 2015 dealt only with the accelerated regulatory process for approval of new drugs and medical devices. On its face, this seems a reasonable thing: get efficacious drugs to the market fast so they can help patients who need them.

The flip side of this issue, however, is loosening scientific standards currently necessary for drug approval. In a phrase, this bill would allow the Food and Drug Administration to approve new drugs based on the “real-world evidence” of observation and insurance claims data, eliminating the scientific gold standard for assessing meaningful testing: the double-blind clinical trial. This modification was advocated for by the pharmaceutical industry, often referred to as big pharma, which clearly had a profit motive for its member companies as part of its underlying rationale. A substantial number of people—including members of Congress—are suspicious of big Pharma, if not downright hostile, citing ever-increasing drug prices and direct-to-consumer advertising, among other reasons. Approving this new, less rigorous standard for drug approval was and would continue to be highly controversial.

Likewise, increasing funding for National Institutes of Health (NIH) research, while not as high profile as pharmaceutical issues, certainly has its supporters among scientists in universities and medical centers. At the same time, however, those interests would be confronted by budget hawks in the legislative process (policymakers who want to hold the line on new spending). Avoiding new spending is generally an easier vote than justifying an increase. Similarly, approving new funding and enhanced organizational stature for mental health and substance abuse disorders may not be particularly controversial, but they lack salience: the issue is complicated to understand; more complicated to explain; and, in general, lacks political appeal.

The transmittal of patient information across multiple platforms may help provide care for patients regardless of location; for many, however, this capacity represents an unacceptable threat to patient privacy. Again, electronic health record portability is a complex issue that defies easy explanation, and politicians would find it politically easier to vote down reform than to explain their reasoning for supporting change.

Each of these issues alone would face a difficult path. This is not to say they could not carry the day, but it is safe to say that some would not and others would face a contentious debate. Each solution attempts to address a legitimate problem; each confronts challenging political circumstances ranging from ambivalence to overt hostility.

In 2016, however, the various advocates for these respective interests began to form alliances. Legislators in favor of a solution to one problem might find sufficient political upside in that issue to overcome their opposition to the solution in another. For example, the members of Congress likely to vote against reducing the standards necessary to win approval for a new drug are, more or less, the same members who favor increasing health-related research capacity. Thus, combining the deregulation issue with more money for the NIH produces a plausible political win for both groups because it is also highly likely that those favoring deregulation are budget hawks and vote against new funding for the NIH.

This is why they say politics makes strange bedfellows. This same concept applies to the other issues in the bill as well. Basically, it became an exercise in trading one set of political interests for another as liberals and conservatives coalesced to produce an overwhelming majority in favor of the combined legislation.

However, this legislation is not only a story about political logrolling, where the members of Congress look after each other’s pet interests. It is also about interest group behavior. In this case, as this coalition began to assemble, it did so with the help of lobbyists. More than 400 companies and organizations registered to lobby on this bill. A stunning 1,455 individual lobbyists registered on behalf of affected interest groups—nearly three lobbyists for each member of Congress (435 House members and 100 senators).

In the end, whether you see this bill as a victory for the public interest, a victory for special interest groups, or a combination of both is a matter of political perception. Regardless of one’s perspective, however, the 21st Century Cures Act is a good example of the power of interest groups to create coalitions that ultimately produce a successful result for their respective interests (Hiltzik 2016; Kaplan 2016; Lupkin 2016; Ornstein 2015).

Originating and Drafting Legislative Proposals

The development of legislation begins with the conversion of ideas, hopes, and hypotheses about how problems might be addressed through changes in policy—ideas that emerge from agenda setting—into concrete legislative proposals or bills (see exhibit 6.2). Proposed legislation can be introduced in one of four forms. Two of the forms, bills and joint resolutions, are used for making laws. The other two forms of proposed legislation, simple resolutions and concurrent resolutions, are used to handle matters of congressional administration or for expressing nonbinding policy views.

Forms of Legislative Proposals

The discussion of originating and drafting legislative proposals presented here focuses on bills because they are the most common way for legislation to emerge. Using conventions developed over time for the subject matter involved, Congress selects between two options for introducing legislative proposals: bills and joint resolutions. Although bills are much more common than joint resolutions, a good example of a routinely used joint resolution is one to continue appropriations beyond the end of a fiscal year (FY), when the regular appropriations bills for the next year have not been completed. This joint resolution is called a continuing resolution (CR) (US House of Representatives Office of the Legislative Counsel 2020a).

For a bill or a joint resolution to become law, it must pass both the House of Representatives and the Senate and be signed by the president. Even if a bill or joint resolution is passed and presented to the president, it can be vetoed. Such vetoed legislation can become law if Congress overrides the veto by a two-thirds vote. The legislation can also become law if the president takes no action for a period of ten days while Congress is in session. There is no legal difference and little practical difference between a bill and a resolution, and they are not differentiated operationally here.

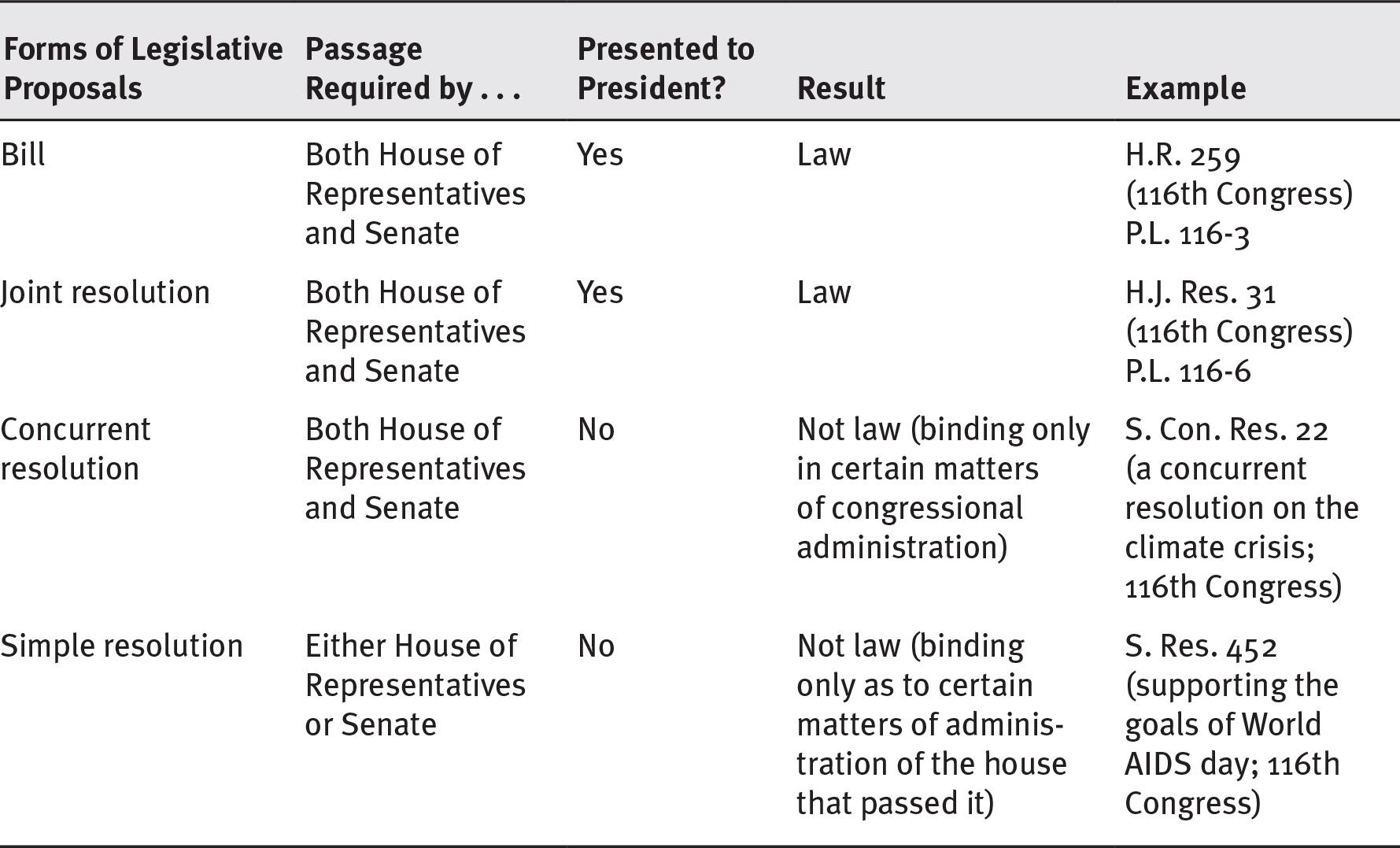

Simple resolutions (passed in either the House of Representatives or the Senate) and concurrent resolutions (passed in both the House of Representatives and the Senate) are not presented to the president because they do not become law. Exhibit 6.5 summarizes the four forms that legislative proposals can take.

EXHIBIT 6.5 Comparison of Forms of Legislative Proposals

Long Description

The details of the table are as follows:

- Bill: the passage is required by both House of Representatives and Senate; it is presented to the president and the result is law; example: H.R. 259 (116th Congress) P.L. 116-3.

- Joint resolution: the passage is required by House of Representatives and Senate; it is presented to the president and the result is law; example: H.J. Res. 31 (116th Congress) P.L. 116-6.

- Concurrent resolution: the passage is required by both House of Representatives and Senate; it is not presented to the president and the result is not law (binding only in certain matters of congressional administration); example: S. Con. Res. 22 (a concurrent resolution on the climate crisis; 116th Congress).

- Simple resolution: the passage is required by either House of Representatives or Senate; it is not presented to the president and the result is not law (binding only as to certain matters of administration of the house that passed it); example: S. Res. 452 (supporting the goals of World AIDS day; 116th Congress).

Source: Adapted from US House of Representatives Office of the Legislative Counsel (2020a).

Origins of Ideas for Public Policies

Ideas for public policies originate in many places. One source is members of the House of Representatives and the Senate. In fact, many Congress members are elected, at least in part, on the basis of the legislative ideas they expressed in their campaigns. Promises to introduce certain proposals, made specifically to the constituents whom candidates seek to represent, are core aspects of the American form of government and frequent sources of eventual legislative proposals. Once in office, legislators may become more aware of and knowledgeable about the need to amend or repeal existing laws or enact new laws as their understanding of the problems and potential solutions that face their constituents or the larger society evolves.

But legislators are not the only source of ideas for laws or amendments. Individual citizens, health-related organizations, and interest groups representing many individuals or organizations may petition the government—a right guaranteed by the First Amendment—and propose ideas for the development of policy in the form of laws or amendments. In effect, such petitions result directly from the participation of individuals, organizations, and groups in agenda setting, as described in chapter 5. Much of the nation’s policy originates in this way because certain individuals, organizations, and interest groups have considerable knowledge of the problem–potential solution combinations that affect them or their members.

Individuals, organizations, and groups also participate in the development of legislation. Interest groups tend to be especially influential in legislation development, as they are in agenda setting, because of their pooled resources. Well-staffed interest groups, for example, can draw on the services of legislative draftspersons to transform ideas and concepts into suitable legislative language.

An increasingly important source of ideas for legislative proposals is “executive communication” from members of the executive branch to members of the legislative branch. Such communications, which also play a role in agenda setting, usually take the form of a letter from a senior member of the executive branch such as a member of the president’s cabinet, the head of an independent agency, or even the president. These communications typically include comprehensive drafts of proposed bills. They are sent simultaneously to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the president of the Senate, who can insert them into the legislation development procedures at appropriate places.

The executive branch’s role as a source of policy ideas is based in the US Constitution. Although the Constitution establishes a government characterized by the separation of powers, Article II, Section 3, imposes an obligation on the president to report to Congress from time to time on the state of the union and to recommend such policies in the form of laws or amendments as the president considers necessary, useful, or expedient. Many of the executive communications to Congress follow up on ideas first aired in annual presidential State of the Union addresses to Congress.

Executive communications that pertain to proposed legislation are referred by the legislative leaders who receive them to the appropriate legislative committee or committees that have jurisdiction in the relevant areas. The chairperson of an affected committee may introduce the bill either in the form in which it was received or with whatever changes the chairperson considers necessary or desirable. Only members of Congress can actually introduce proposed legislation, no matter who originates the idea or drafts the proposal.

As a matter of comity, the congressional committees will introduce legislative requests from the executive branch even when the majority of the House or Senate and the president are not of the same political party, although there is no constitutional or statutory requirement to do so. The committee’s jurisdiction is based on the proposal’s subject matter. The committee or one of its subcommittees considers the proposed legislation to determine whether the bill should be introduced.

The most important regular executive communication is the proposed federal budget the president transmits annually to Congress (Oleszek 2014). Recently prepared budgets and related supporting documents are available from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB; www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget). While the budget process will be addressed in more detail later in this chapter, in broad terms, there are 12 subcommittees of the appropriations committees of the House and Senate. Those subcommittees use the president’s budget proposal, together with supportive testimony by officials of the various executive branch departments and agencies, individuals, organizations, and interest groups as the basis of the appropriation bills that these subcommittees draft.

Drafting Legislative Proposals

Drafting legislative proposals is an art, one requiring considerable skill, knowledge, and experience. Any member of the Senate or House of Representatives can draft bills, and these legislators’ staffs are usually instrumental in the process, often with assistance from the Office of Legislative Counsel of either the House or the Senate (nonpartisan organizations that provide the same services to members of either party, both in their respective bodies).

Office of Legislative Counsel

“The Office of the Legislative Counsel provides legislative drafting services to the committees and Members of the House of Representatives on a non-partisan, impartial, and confidential basis. Our goal is to work with committees and Members to understand their policy preferences in order to implement those preferences through clear, concise, and legally effective legislative language” (US House of Representatives Office of Legislative Counsel 2020b). Information on how the Office of the Legislative Counsel in the House of Representatives supports legislation development is available at https://legcounsel.house.gov. Information on how the Senate’s Office of the Legislative Counsel supports legislation development is available at www.senate.gov.

When bills are drafted in the executive branch, trained legislative counsels are typically involved. These counsels work in several executive branch departments, and their work includes drafting bills to be forwarded to Congress. Similarly, proposed legislation that arises in the private sector, typically from interest groups, is drafted by people with expertise in this intricate task.

No matter who drafts legislation, however, only members of Congress can officially sponsor a proposal, and the legislative sponsors are ultimately responsible for the language in their bills. Bills commonly have multiple sponsors and many cosponsors. Once ideas for solving problems through policy are drafted in legislative language, they are ready for the next step: introduction for formal consideration by Congress.

On occasion, legislation drafting is undertaken as a public–private partnership (Hacker 1997, 2010). Such legislation drafting has occurred twice in recent decades in the health policy arena. Although the health security proposal the Clinton administration drafted was formally introduced in Congress, it was not enacted into law. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), on the other hand, was formally introduced and moved through the other steps in legislation development before it was enacted into law.

Health Security Act

In the first example, in late 1993, after many months of feverish drafting by a team including some of the nation’s foremost health policy experts, President Bill Clinton presented his proposal for legislation that would fundamentally reform the American healthcare system. The document, 1,431 pages in length, outlined the drafters’ vision of the way health services should be provided and financed in the United States. The proposal was in the form of a comprehensive draft of a bill (to be called the Health Security Act) that could potentially be enacted into law.

However, the proposal faced a long and difficult path from legislation development to possible enactment. Hacker and Skocpol (1997, 315–16) noted that “President Clinton sought to enact comprehensive federal rules that would, in theory, simultaneously control medical costs and ensure universal insurance coverage. The bold Health Security initiative was meant to give everyone what they wanted, delicately balancing competing ideas and claimants, deftly maneuvering between major factions in Congress, and helping to revive the political prospects of the Democratic Party in the process.”

In the end, the Clinton health reform proposal failed to make it successfully through the remaining steps in legislation development to enactment into law (Johnson and Broder 1996; Skocpol 1996). Peterson (1997, 291) characterized the failure of this proposal as a situation in which “the bold gambit of comprehensive reform had once again succumbed to the power of antagonistic stakeholders, a public paralyzed by the fears of disrupting what it already had, and the challenge of coalition building engendered by the highly decentralized character of American government.” The other political flaw in the Clinton proposal was that, while there was stakeholder input, the legislation was drafted under a cloak of secrecy. Congress was presented with the complete plan—a plan that fundamentally reengineered the health services delivery system– that left little room for meaningful congressional input. By not engaging in the usual vetting process with professionals from agencies and members of Congress, the Clinton administration missed the opportunity to build support for the proposal early in the process (Johnson and Broder 1996).

The Affordable Care Act

The second example of developing legislation through a public–private partnership led to a more successful outcome. The ACA was enacted in 2010. (See appendix 1.1, an overview of the ACA.) There have been difficulties in implementing this law and extraordinary attempts have been made to repeal it (Jost 2014), but this legislation was successfully developed into public law, and a complex law at that.

Technically, in March 2010, the 111th Congress enacted the ACA (P.L. 111-148). The law was substantially amended by the health provisions in the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-152). Several other laws that were subsequently enacted made more targeted changes to specific ACA provisions. The ACA emerged from bills in the House of Representatives and the Senate. In the Senate, two committees—the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) and the Committee on Finance—participated in the drafting. The law was formed in an amazingly convoluted series of negotiations involving numerous members of Congress working through various committees, the administration, congressional and administration staff, external stakeholders such as the pharmaceutical and insurance industries, and the professionals who wrote the actual language of the law. Cannan (2013) wrote a thorough history of the ACA’s dynamic path through the legislation development step.

One political reality of the ACA was that the Obama administration had learned—or in the eyes of some, overlearned—the lessons of Clinton’s proposal. The Obama administration plan built on the existing system of private insurance. At the same time, however, the administration presented Congress not with any draft legislation, but with an overarching set of principles crafted through negotiations with stakeholder groups. In essence, the administration asked Congress to draft the legislation from scratch. This strategy contributed to the confusion associated with the legislative process (Altman and Shactman 2011).

The ACA had multiple goals. Among the most important were to increase access to affordable health insurance for the millions of Americans without coverage and make health insurance more affordable for those already covered. While largely relying on the existing system of commercial insurance, the act made numerous changes in the way healthcare is financed, organized, and delivered. Among its many provisions, the ACA restructured the private health insurance market, set minimum standards for health coverage, created a mandate for most US residents to obtain health insurance coverage, and provided for the establishment of state-based insurance exchanges for the purchase of private health insurance. Federal subsidies in the form of tax credits were made available to certain classes of individuals and families to reduce the cost of purchasing coverage through the exchanges. The ACA also expanded eligibility for Medicaid dramatically; amended the Medicare program in ways that were intended to reduce the growth in Medicare spending; imposed an excise tax on insurance plans found to have high premiums; and made numerous other changes to the tax code, Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and many other federal programs. Full implementation of the law involved all the major healthcare stakeholders, including the federal and state governments, as well as employers, insurers, and healthcare providers (Redhead et al. 2012).

Packed into 1,024 pages, the ACA is a product of input from many sources. For example, the individual mandate provision requiring most residents to obtain health insurance, coupled with public subsidies for many, has deep historical roots in previous health reform attempts. The conservative Heritage Foundation proposed an individual mandate as an alternative to single-payer healthcare as far back as 1989 (Avik 2012). In 2006, Massachusetts enacted health reform at the state level that included an individual mandate and an insurance exchange (Wees, Zaslavsky, and Ayanian 2013). The individual mandate, despite its deep historical roots, is also highly controversial (see the policy snapshots for parts 1 and 3).

The ACA was the product of a bitterly partisan struggle. In the wake of that struggle, the ACA has been repeatedly attacked in both legislative and judicial forums, mostly from the political right. In the Democratic presidential primaries of 2020, however, the political left increasingly advocated for “Medicare for all.” From a policymaking perspective, the underlying lesson is clear: Policy initiatives that enjoy broad-based, bipartisan support, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP, are more likely to achieve the desired result and less likely to be subject to attack, either in the legislative or judicial branches, than those enacted on the barest of partisan margins.

Introducing and Referring Proposed Legislation to Committees

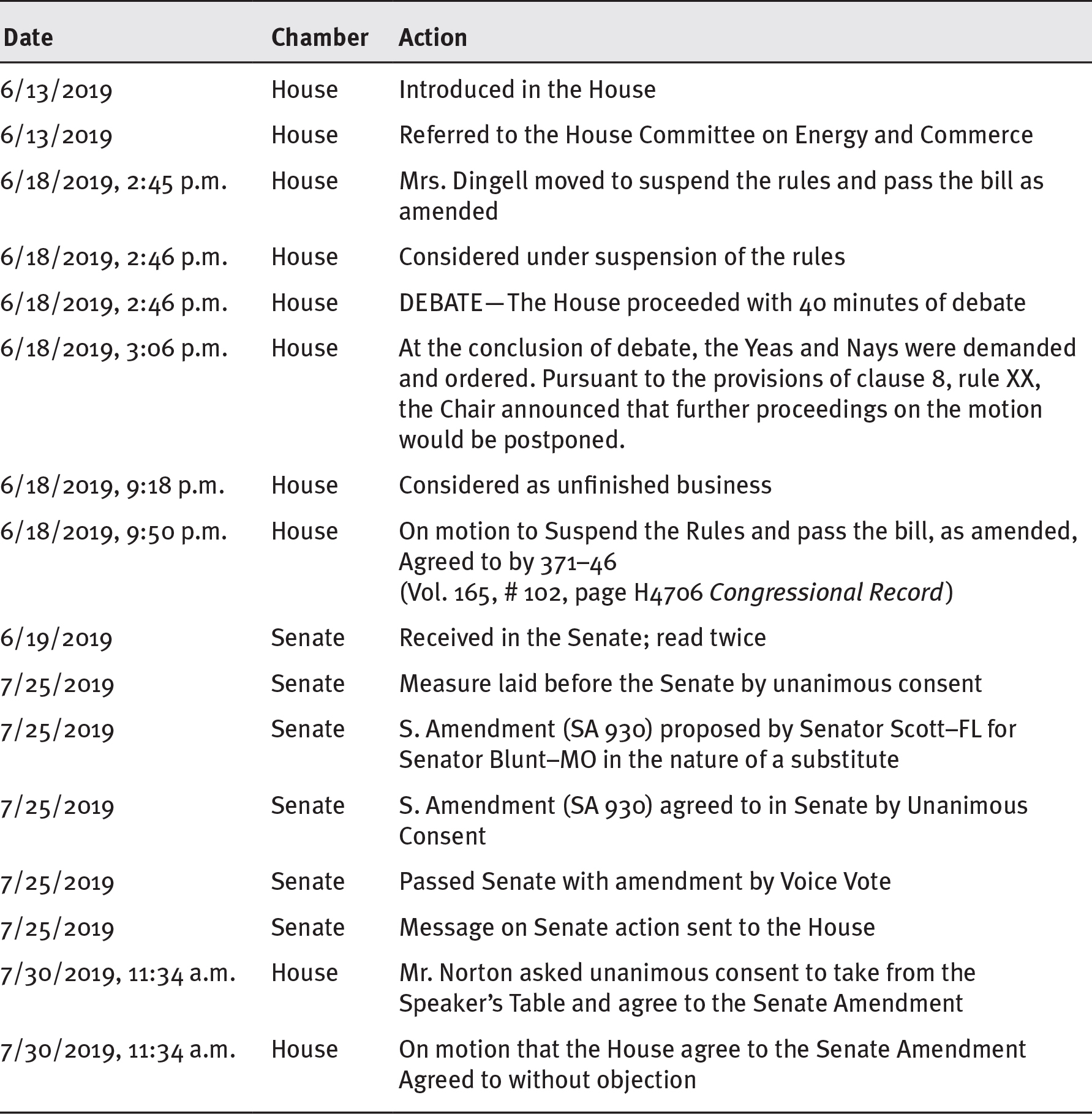

Members of the Senate and the House of Representatives who have chosen to sponsor or cosponsor legislation introduce their proposals in the form of bills (see exhibit 6.2). On occasion, identical bills are introduced in the Senate and House for simultaneous consideration. When bills are introduced in either chamber of Congress, they are assigned a sequential number (e.g., H.R. 1, H.R. 2, H.R. 3, etc.; S. 1, S. 2, S. 3, etc.) based on the order of introduction by the presiding officer and are referred to the appropriate standing committee or committees for further study and consideration. Exhibit 6.6 illustrates the path of a bill introduced in the House of Representatives through its enactment into public law.

EXHIBIT 6.6 Path to a Public Law: H.R. 3253—Sustaining Excellence in Medicaid Act of 2019

Long Description

The table lists date, chamber, and actions and they are as follows:

- June 13 2019; House; Introduced in the House.

- June 13 2019; House; Referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce.

- June 18 2019, 2:45 P.M.; House; Mrs. Dingell moved to suspend the rules and pass the bill as amended.

- June 18 2019, 2:46 p.m.; House; Considered under suspension of the rules.

- June 18 2019, 2:46 p.m.; House; Debate: The House proceeded with 40 minutes of debate.

- June 18 2019, 3:06 p.m.; House; At the conclusion of debate, the Yeas and Nays were demanded and ordered. Pursuant to the provisions of clause 8, rule XX, the Chair announced that further proceedings on the motion would be postponed.

- June 18 2019, 9:18 p.m.; House; Considered as unfinished business.

- June 18 2019, 9:50 p.m.; House; On motion to Suspend the Rules and pass the bill, as amended, Agreed to by 371–46 (Volume 165, hash 102, page H4706 Congressional Record).

- June 19 2019; Senate; Received in the Senate; read twice.

- July 25 2019; Senate; Measure laid before the Senate by unanimous consent.

- July 25 2019; Senate; S. Amendment (SA 930) proposed by Senator Scott–FL for Senator Blunt–MO in the nature of a substitute.

- July 25 2019; Senate; S. Amendment (SA 930) agreed to in Senate by Unanimous Consent.

- July 25 2019; Senate; Passed Senate with amendment by Voice Vote.

- July 25 2019; Senate; Message on Senate action sent to the House.

- July 30 2019, 11:34 a.m.; House; Mr. Norton asked unanimous consent to take from the Speaker’s Table and agree to the Senate Amendment.

- July 30 2019, 11:34 a.m.; House; On motion that the House agree to the Senate Amendment Agreed to without objection.

EXHIBIT 6.6 Path to a Public Law: H.R. 3253—Sustaining Excellence in Medicaid Act of 2019

Long Description

The table lists date, chamber, and actions and they are as follows:

- July 30 2019, 11:34 a.m.; House; Motion to reconsider laid on the table and Agreed to without objection.

- August 1 2019; House; Presented to the President.

- August 6 2019; Signed by the President.

- August 6 2019; Became Public Law No. 116-39.

Note: The path is not always as straightforward as is portrayed here. In this case, there was little or no controversy, no committee amendments, and only minor amendments in the Senate, to which the House of Representatives agreed without a conference committee. At times a bill in one house may completely replace a bill from the house of origin. For the detailed history that includes all the references to the Congressional Record as well as the summary quoted earlier, see Congress.gov (2019a).

Source: Data from Congress.gov (2019a).

The US Congress reports that

this bill alters several Medicaid programs and funding mechanisms. Specifically, the bill

- makes appropriations through FY 2024 for, and otherwise revises, the Money Follows the Person Rebalancing Demonstration Program;

- allows state Medicaid fraud control units to review complaints regarding patients who are in noninstitutional or other settings;

- temporarily extends the applicability of Medicaid eligibility criteria that protect against spousal impoverishment for recipients of home and community-based services;

- temporarily extends the Medicaid demonstration program for certified community behavioral health clinics;

- repeals the requirement, under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, that drug manufacturers include the prices of certain authorized generic drugs when determining the average manufacturer price (AMP) of brand-name drugs (also known as a “blended AMP”), and excludes manufacturers from the definition of “wholesalers” for purposes of rebate calculations; and

- increases funding available to the Medicaid Improvement Fund beginning in FY 2021 (Congress.gov 2019a).

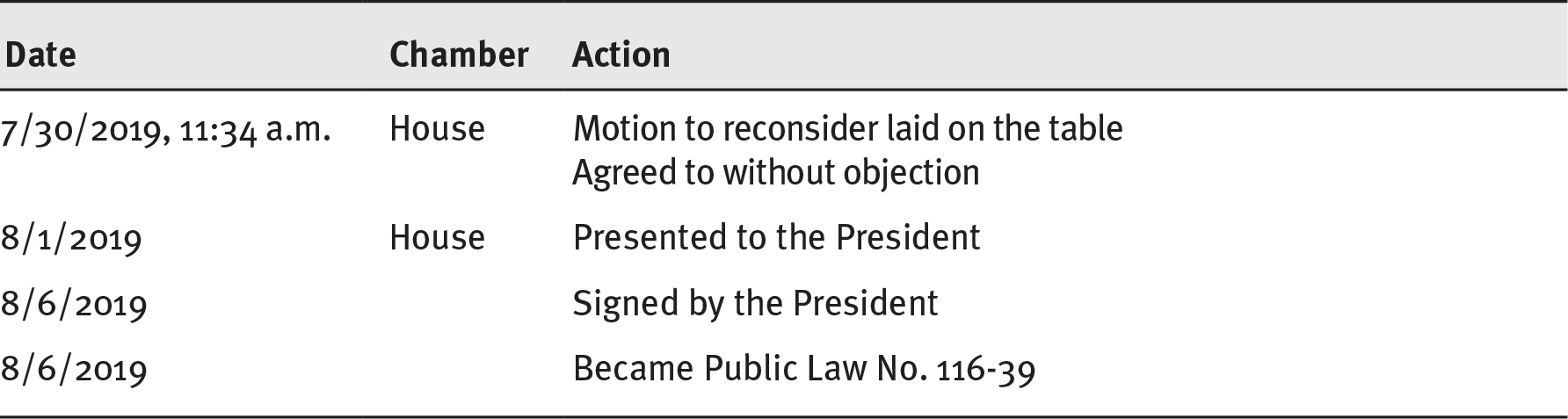

Legislative Committees and Subcommittees

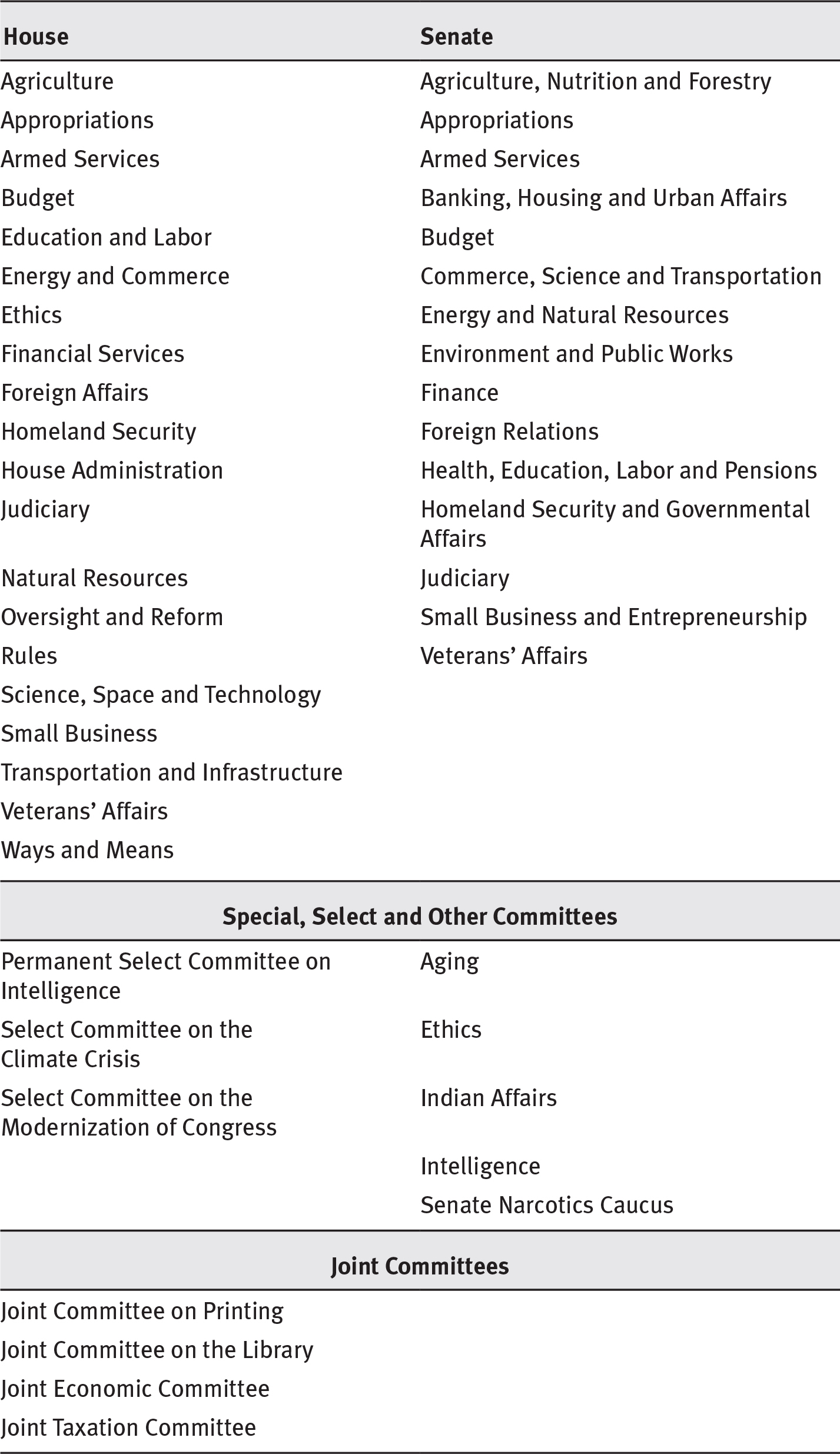

The Senate and the House of Representatives are organized into legislative committees and subcommittees. The committee structure of Congress is crucial to the development of legislation. Committee and subcommittee deliberations provide the settings for intensive and thorough consideration of legislative proposals and issues. Exhibit 6.7 shows the current legislative committee structure of the US Congress.

EXHIBIT 6.7 Congressional Committees for the 116th Congress, January 2019–January 2021

Long Description

The committees are as follows:

The legislative committees in house are: Agriculture; Appropriations; Armed Services; Budget; Education and Labor; Energy and Commerce; Ethics; Financial Services; Foreign Affairs; Homeland Security; House Administration; Judiciary; Natural Resources; Oversight and Reform; Rules; Science; Space and Technology; Small Business; Transportation and Infrastructure; Veterans’ Affairs; and Ways and Means.

The Legislative Committees in Senate are: Agriculture; Nutrition and Forestry; Appropriations; Armed Services; Banking; Housing and Urban Affairs; Budget; Commerce; Science and Transportation; Energy and Natural Resources; Environment and Public Works; Finance; Foreign Relations; Health; Education; Labor and Pensions; Homeland Security and Governmental; Affairs; Judiciary; Small Business and Entrepreneurship; and Veterans’ Affairs.

The special; select; and other committees are: Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence; Aging; Select Committee on the Climate Crisis; Ethics; Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress; Indian Affairs; Intelligence; and Senate Narcotics Caucus.

The joint committees are: Joint committee on Printing; Joint Committee on the Library; Joint Economic Committee; and Joint Taxation Committee.

Source: Congress.gov (2019b).

Each standing committee has jurisdiction over a certain area of legislation, and all bills that pertain to a particular area are referred to its committee. Information about the committees is available on their websites, which can be accessed through www.congress.gov. Committees are divided into subcommittees to facilitate work. For example, the Ways and Means Committee of the House of Representatives has six subcommittees: Health, Human Resources, Oversight, Select Revenue Measures, Social Security, and Trade.

Sometimes the content of a bill calls for assignment to more than one committee. In this case, the bill is assigned to multiple committees either jointly or, more commonly, sequentially. For example, the Clinton administration’s Health Security plan was introduced simultaneously in the House and the Senate as H.R. 3600 and S. 1757. Because of its scope and complexity, the bill was then referred jointly to ten House committees and two Senate committees for consideration and debate.

Membership on the various congressional committees is divided between the two major political parties. The proportion of members from each party is determined by the majority party, using a ratio of majority to minority members. In other words, the more there are of one party in either house, the more members from that party will serve on committees, with concomitantly fewer member of the minority party. Legislators typically seek membership on committees that have jurisdiction in their particular areas of interest and expertise. The interests of their constituencies typically influence the interests of policymakers. For example, members of the House of Representatives from agricultural districts or financial centers often prefer to join committees that deal with these areas. The same is true of senators in terms of whether they hail from primarily rural or highly urbanized states, from the industrialized Northeast, or from the more agrarian West. The seniority of committee members follows the order of their appointment to the committee.

The majority party in each chamber also controls the appointment of committee and subcommittee chairpersons. These chairpersons exert great power in the development of legislation because they determine the order and the pace in which the committees or subcommittees they lead consider legislative proposals.

Each committee has a professional staff to assist with administrative details involved in its consideration of bills. Under certain conditions, a standing committee may also appoint consultants on a temporary or intermittent basis to assist the committee in its work. By virtue of expert knowledge, the professional staff members who serve committees and subcommittees are key participants in legislation development.

Committees with Health Policy Jurisdiction

Although no congressional committee is devoted exclusively to the health policy domain, several committees and subcommittees have jurisdiction in health-related legislation development. In recent decades, health has been an especially important and prevalent domain in the federal and state policy agendas. The committees and subcommittees with jurisdiction for health matters have been busy.

At the federal level, there is some overlap in the jurisdictions of committees with health-related legislative responsibilities. Most general health bills are referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce and the Senate HELP Committee. However, any bills involving taxes and revenues must be referred to the House Committee on Ways and Means and the Senate Committee on Finance. These two committees have substantial health policy jurisdiction because so much health policy involves taxes as a source of funding. The main health policy interests of these committees are outlined here.

- Committee on Finance (www.finance.senate.gov), with its Subcommittee on Health Care. This Senate committee has jurisdiction over health programs under the Social Security Act and health programs financed by a specific tax or trust fund. This role gives the committee jurisdiction over matters related to the ACA, Medicare, and Medicaid.

- Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (www.help.senate.gov), with its Subcommittees on Children and Families, Employment and Workplace Safety, and Primary Care and Aging. This Senate committee’s jurisdiction encompasses most of the agencies, institutes, and programs of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), including the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, the Administration on Aging, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The committee also oversees public health and health insurance policy.

- Committee on Ways and Means (http://waysandmeans.house.gov), with its Subcommittee on Health. This House committee has jurisdiction over bills and matters that pertain to providing payments from any source for healthcare, health delivery systems, or health research. The jurisdiction of the Subcommittee on Health includes bills and matters related to the healthcare programs of the Social Security Act (including Titles XVIII and XIX, which are the Medicare and Medicaid programs), portions of the ACA, and tax credit and deduction provisions of the Internal Revenue Code dealing with health insurance premiums and healthcare costs.

- Committee on Energy and Commerce (http://energycommerce.house.gov) with its subcommittees, including those on Health and on Environment and the Economy. This House committee has jurisdiction over all bills and matters related to public health and quarantine; hospital construction; mental health; biomedical research and development; health information technology, privacy, and cybersecurity; public health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid) and private health insurance; medical malpractice insurance; the regulation of food and drugs; drug abuse; HHS; the Clean Air Act; and environmental protection in general, including the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Legislative Committee and Subcommittee Operations

Depending on whether the chairperson of a committee has assigned a bill to a subcommittee, either the full committee or the subcommittee can, if it chooses, hold hearings on the bill. At these public hearings, members of the executive branch, representatives of health-related organizations and interest groups, and other individuals can present their views and recommendations on the legislation under consideration. For example, from the 116th Congress, no fewer than nine bills pertaining to universal healthcare were introduced. A partial rendition includes HR 1277, the State Public Option Act; HR 1384, the Medicare for All Act; HR 2452, the Medicare for America Act; and HR 584, the Incentivizing Medicaid Expansion Act. (For a complete list see House Committee on Energy and Commerce.)

All of these bills were referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. The health subcommittee conducted a hearing on all of the proposals en masse on December 10, 2019. Appendix 2.3 provides an example of testimony at a hearing related to this issue before the House Subcommittee on Health of the Committee on Energy and Commerce.

Following such hearings, and there may be a number of them for a bill, members of committees or subcommittees mark up the bills they are considering. This term refers to going through the original bill line by line and making changes. Sometimes, when similar bills or bills addressing the same issue have been introduced, they are combined in the markup process. In cases of subcommittee involvement, when the subcommittee has completed its markup and voted to approve the bill, it reports out the bill to the full committee with jurisdiction.

When no subcommittee is involved, or when a full committee has reviewed the work of a subcommittee and voted to approve the bill, the full committee reports out the bill for a vote, this time to the floor of the Senate or House. At this point, the administration can formally weigh in with support for or opposition to a bill. This input is issued through a statement of administration policy, examples of which are available at OMB (2020b).

Administration officials also may be called on to testify to either the committee or subcommittee. If a committee votes to report a bill favorably, a member of the committee staff writes a report in the name of a committee member. This report is an extremely important document. The committee report describes the purposes and scope of the bill and the reasons the committee recommends its approval by the entire Senate or House. As an example, the report for H.R. 1014 can be read at the congressional website (www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/1014).

Committee reports are useful and informative documents in the legislative history of a public law or amendments to it. These reports are used by courts in considering matters related to particular laws that have been enacted and by executive branch departments and agencies as guidance for implementing enacted laws and amendments. They provide information regarding legislative intent for courts, attorneys, agencies, and others who may be interested in the history, purpose, and meaning of enacted legislation.

Generally, a committee report contains an analysis in which the purpose of each section of a bill is described. All changes or amendments to existing law that the bill would require are indicated in the report, and the text of laws the bill would repeal are set out. The report begins by describing and explaining committee amendments to the bill as it was originally referred to the committee. Executive communications pertaining to the bill are usually quoted in full in the report. Witness testimony is likewise either included directly or included by reference in the report.

From Committee to the President

Following approval of a bill by the full committee with jurisdiction, the bill and its report are discharged from the committee. The House or Senate receives it from the committee and places it on the legislative calendar for floor action (see exhibit 6.2).

Bills can be further amended in debate on the House or Senate floor. However, because great reliance is placed on the committee process in both chambers of Congress, amendments to bills proposed from the floor require considerable support. Indeed, in the House, a bill may not be assigned a rule that permits amendments. In the Senate, in order to avoid a filibuster, sometimes an amendment will need 60 votes to succeed.

Once a bill passes in either the House or the Senate, it is sent to the other chamber. The step of referral to a committee with jurisdiction, and perhaps then to a subcommittee, is repeated, and another round of hearings, markup, and eventual action may or may not take place. If the bill is again reported out of committee, it goes to the involved chamber’s floor for a final vote. If it is passed in the second chamber, any differences in the House and Senate versions of a bill must be resolved in conference committee. At that point, both houses must adopt identical versions of the conference committee report before the bill is sent to the White House for action by the president.

Conference Committee Actions on Proposed Legislation

To resolve differences in a bill that both chambers of Congress have passed, a conference committee (see exhibit 6.2) may be established (US Senate 2014). On occasion, the initial house will accede to the amendments from the other chamber, as occurred in our example in exhibit 6.5. Conferees are usually the ranking members of the committees that reported out the bill in each chamber. If they can resolve the differences, a conference report is written and both chambers of Congress vote on it. If the conferees cannot reach agreement, or if either chamber does not accept the report, the bill dies. However, if both chambers accept the conference report, the bill is sent to the president for action. The conference committee process is described more fully in appendix 2.4.

Presidential Action on Proposed Legislation

The president has several options regarding proposed legislation that has been approved by both the House and the Senate (see exhibit 6.2). The president can sign the bill, in which case it immediately becomes law. The president can veto the bill, in which case it must be returned to Congress along with an explanation for the rejection. A two-thirds vote in both chambers of Congress can override a presidential veto. The president’s third option is neither to veto the bill nor to sign it. In this case, the bill becomes law in ten days, but the president has made a political statement of disfavor regarding the legislation. A fourth option may apply when the president receives proposed legislation near the close of a congressional session; the bill can be pocket vetoed if the president does nothing about it until the Congress is adjourned. In this case, the bill dies.

Legislation Development for the Federal Budget

Because enactment of legislation related to the federal government’s annual budget is so crucial to the government’s performance and the well-being of the American people, special procedures have been developed to guide this process. The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 and the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 and their subsequent amendments provide Congress with the process through which it establishes target levels for revenues, expenditures, and the overall deficit for the coming FY. The budget process is designed to coordinate decisions on sources and levels of federal revenues and on the objectives and levels of federal expenditures. Such decisions affect other policy decisions, including those that pertain to health.

A distinctive feature of legislation development for the budget is the president’s role. The president is required to submit a budget request to Congress each year to initiate the process. By doing so, the president establishes the starting point and the framework for the annual process of legislation development for the federal budget. Once the president submits a budget request, the legislative process for federal budget making unfolds in distinct stages. First, Congress drafts and approves a budget resolution that provides the framework for overall federal government taxation and spending for various agencies and programs for the upcoming year. Next, the agencies and programs are authorized by way of establishment, extension, or modification. This authorization must take place before any money can be appropriated for an agency or program, which is the final stage of federal budget making.

The federal budgeting process is enormously complex. It “entails dozens of subprocesses, countless rules and procedures, the efforts of tens of thousands of staff persons in the executive and legislative branches, millions of work hours each year, and the active participation of the president and congressional leaders, as well as other members of Congress and executive officials” (Heniff, Lynch, and Tollestrup 2012, ii). Several federal agencies play especially important research and oversight roles in the budgeting process. These include the OMB, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

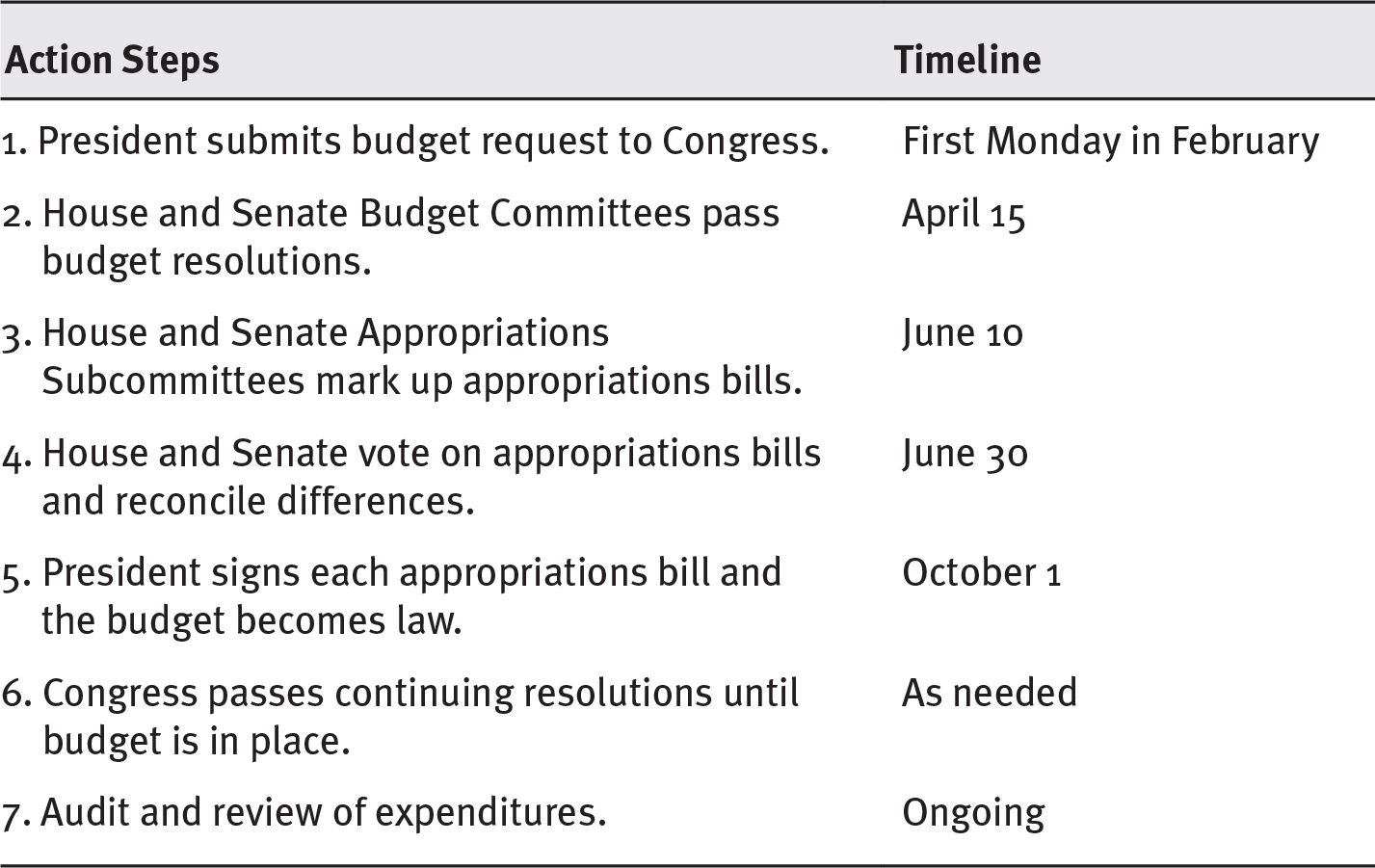

Exhibit 6.8 shows the actions and timeline through which the annual federal budget is supposed to be developed. As noted earlier, the schedule begins when the president submits a budget request to Congress. Appendix 2.5 describes these steps in greater detail.

EXHIBIT 6.8 Steps in the Federal Budget Process

Long Description

The action steps are as follows:

- President submits budget request to Congress; first Monday in February

- House and Senate Budget Committees pass budget resolutions; April 15

- House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees mark-up appropriations bills; June 10

- House and Senate vote on appropriations bills and reconcile differences; June 30

- President signs each appropriations bill and the budget becomes law; October 1

- Congress passes continuing resolutions until budget is in place; as needed

- Audit and review of expenditures; ongoing.

Source: Data from Amadeo (2019), USA.gov (2019).

President’s Budget Request

The president’s budget, officially referred to as the Budget of the United States Government (www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget), is required by law to be submitted to Congress no later than the first Monday in February (see step 1 in exhibit 6.8). The budget request by the president includes estimates of spending, revenues, borrowing, and debt. In addition, it includes policy and legislative recommendations and detailed estimates of the financial operations of federal agencies and programs. The president’s budget request plays three important roles. First, the budget request tells Congress what the president recommends for overall federal fiscal policy. Second, it lays out the president’s priorities for spending on health, defense, education, and so on. Finally, the budget request signals to Congress the spending and tax policy changes the president prefers (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 2020).

The president’s budget is only a request to Congress, which can do as it pleases. Even so, the formulation and submission of the budget request is an important tool in the president’s direction of the executive branch and of national policy. The president’s proposals often influence congressional revenue and spending decisions, though the extent of the influence varies from year to year and depends on such variables as political circumstances and the condition of the economy (Heniff, Lynch, and Tollestrup 2012).

Preparation of the president’s budget typically begins at least nine months before it is submitted to Congress. Therefore, preparation begins about 17 months before the start of the FY to which a budget pertains. The early stages of budget preparation occur in federal agencies, primarily in the OMB.

Congressional Budget Resolution

On receiving the president’s budget request, Congress begins the months-long process of reviewing the request (step 2 in exhibit 6.8). Based on the review process, which may include hearings to question administration officials, the House and Senate Budget Committees draft their budget resolutions. These resolutions go to the House and Senate floors, where they can be amended (by a majority vote). A House–Senate conference then resolves any differences, and a reconciled version is voted on in each chamber.

Because the budget resolution is a “concurrent” congressional resolution, it is not signed by the president and is not a law. The concurrent resolution is the congressional statement of spending priorities—the legislative counterbalance to the executive branch budget. Budget resolutions are supposed to be passed by April 15, but often are not. Resolutions may not be passed because of disagreements about spending levels and priorities. On occasion, no budget resolution is passed, in which case the previous year’s resolution remains in effect. Congress has failed to pass a budget resolution by the April 15 deadline on many occasions. When Congress fails to do so, the House can begin to work on most of the appropriations bills without a budget resolution after one month. The Senate can also do so if a majority of senators favors proceeding. In the early part of the twenty-first century, owing to hyperpartisanship, Congress had substantial difficulty establishing a congressional budget and passing the necessary 12 appropriations bills.

Congressional Appropriations Process

Before appropriations can be made to any agency or program, they first must be authorized. Authorization can occur through a law that establishes a program or agency and sets the terms and conditions under which it operates or by a law that specifically authorizes appropriations for that program or agency. Assuming that authorization has occurred, federal spending for agencies and programs occurs in two main forms: mandatory and discretionary. Primarily, mandatory spending, also known as direct spending, is for entitlement programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. The ACA contains some mandatory programs such as the Prevention and Public Health Fund, for example. Mandatory spending is under the jurisdiction of the legislative committees of the House and Senate. The House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee are most responsible for mandatory spending decisions. Discretionary spending decisions occur in the context of annual appropriations acts. All discretionary spending is under the jurisdiction of the appropriations committees in the House and the Senate (Tollestrup 2012).

The appropriations acts passed by Congress provide federal agencies and programs legal authority to incur obligations. These acts also grant the Treasury Department the authority to make payments for designated purposes (Heniff, Lynch, and Tollestrup 2012). Steps 3 and 4 in exhibit 6.8 constitute the federal appropriations process. Based on the guidance provided by the budget resolution, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees allocate spending levels to their 12 subcommittees, which then determine funding levels for the agencies and programs under their jurisdiction. The subcommittees include those for labor, health and human services, education, and related agencies as well as 11 others in each chamber of Congress.

As with delays in Congress failing to pass a budget resolution by the deadline, disagreements over spending levels and priorities also delay the work of the appropriations committees’ subcommittees. When some or all of the appropriations subcommittees fail to pass their spending bills, the bills can be grouped into a single appropriations bill, called an omnibus bill, and sent to the floor of the House or Senate for a vote.

President Signs Appropriations Bills

For the federal budget to become law, the president must sign each appropriations bill passed by Congress (step 5 in exhibit 6.8). Only then is the budget process complete for the year. Rarely, however, is this work completed by the September 30 deadline so that the budget can become law on October 1. When appropriations bills are stalled, the Congress must pass a CR to permit government agencies to continue with normal routines as if then-current spending levels were in effect.

At times even this small, incremental step becomes challenging to the point of dysfunction. When that occurs, the government shuts down. At times, this has been only a partial shutdown because some, but not all, of the appropriations bills have passed. Agencies implicated in the bills not passed will shut down; those whose appropriations have been enacted proceed to function under the new funding levels (step 6 in exhibit 6.8). The alternative to a CR is to shut down the nonessential activities of the federal government. Both CRs and shutdowns are problematic for the agencies and programs operating under the federal budget.

Audit and Review of Expenditures

Even when the federal budget for a given FY is completed and operating, however, the budgeting cycle continues. Review and evaluation of expenditures are continual, along with legislative oversight and targeted auditing by the GAO, an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress. Among its duties are “auditing agency operations to determine whether federal funds are being spent efficiently and effectively; investigating allegations of illegal or improper activities; and reporting on how well government programs and policies are meeting their objectives” (GAO 2020). The CBO produces “independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional Budget process” (CBO 2020). Among its products is a monthly analysis of federal spending and revenue totals for the previous month, current month, and FY to date. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) works directly for the president and has major responsibility for budget development and execution and oversight of agency and program performance (OMB 2020a).

Legislation Development for State Budgets

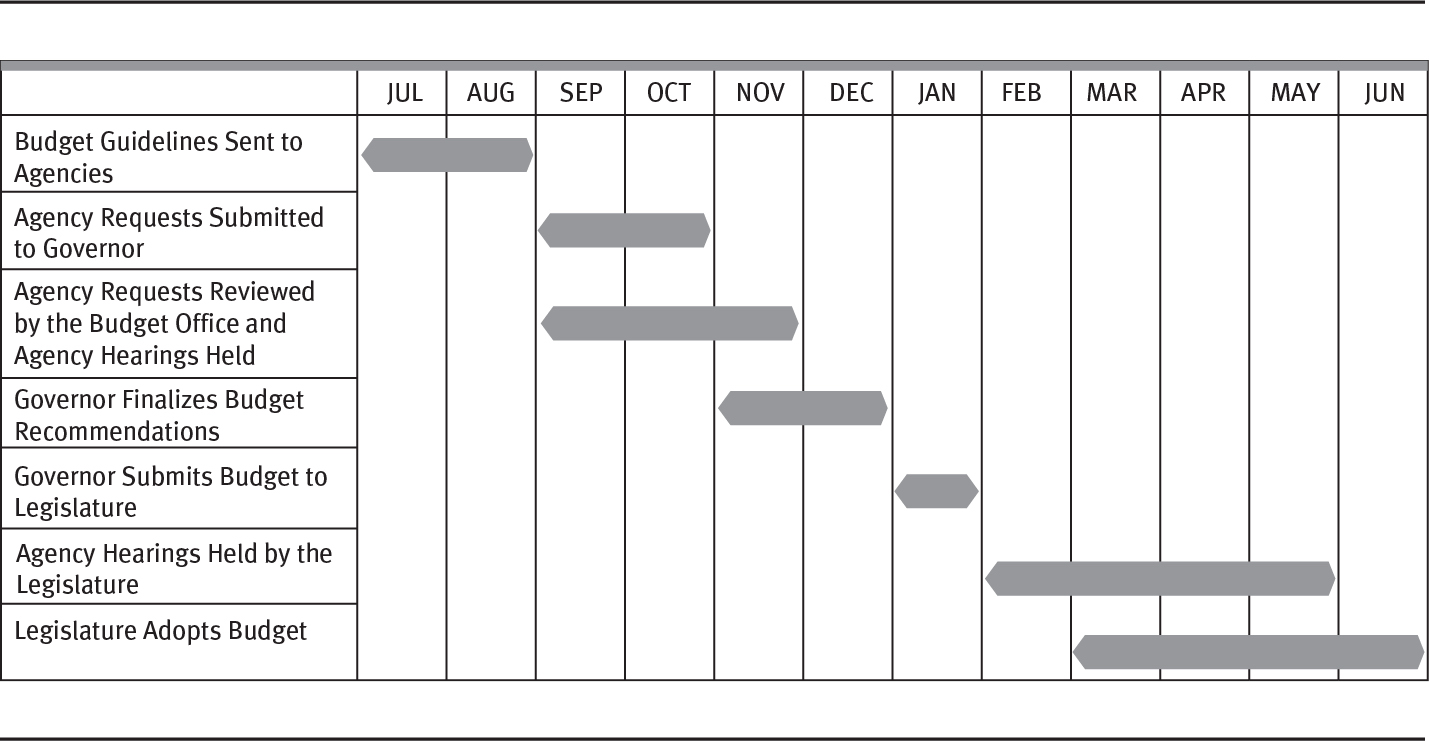

The states also develop budget legislation, although the process varies from state to state. In all states, however, the budget is among the most—if not the most—important mechanisms for establishing policy priorities. Despite the variability in state processes, some general concepts within a framework may be observed. Note the typical timeframes for different parts of the process in exhibit 6.9.

EXHIBIT 6.9 Steps in the State Budget Process

Long Description

The details of the state budget process are as follows:

- Budget Guidelines Sent to Agencies: July to August

- Agency Requests Submitted to Governor: September to October

- Agency Requests Reviewed by the Budget Office and Agency Hearings Held: September to November

- Governor Finalizes Budget Recommendations: November to December

- Governor Submits Budget to Legislature: January

- Agency Hearings Held by the Legislature: February to May

- Legislature Adopts Budget: March to June.

Source: Reprinted from National Association of State Budget Officers (2020).

Stage 1: Budget Preparation

The budget office, in most states housed in the executive branch, sends instructions to agencies outlining format and other parameters with which agencies must comply. Agencies respond with requests. The budget office will then prepare a draft budget based on the governors’ priorities. At this juncture, the governor or the budget office may hold hearings or meetings with department heads to permit them an opportunity to appeal for agency priorities.

The governor’s budget, the result of the preparation stage, is finalized (usually in January) and submitted to a joint session of the general assembly through the governor’s budget address in early February.

Note there is some variation in the calendar, in part because of what date the state has chosen as the beginning of its FY. Forty-six states use a July 1 FY; New York uses April 1; Texas uses September 1; Alabama, Michigan, and the District of Columbia all use October 1, the same date used by the federal government.

The revenue estimating process is also important. Most states have a balanced budget requirement; 39 states cannot carry forward any deficit, which is effectively a balanced budget requirement (White 2017).

Stage 2: Legislative Review and Approval

On receiving the budget, the respective house and senate committees with jurisdiction over the budget hold hearings to review agency requests for funds. Cabinet secretaries and others participate in these hearings, which provide legislators with an opportunity to review the specific programmatic, financial, and policy aspects of each agency’s programs and requests. At the same time, legislative staff members analyze the details of the proposals. These review activities provide interest groups with their greatest opportunities to influence the outcome in specific areas by interacting with the legislature. The legislature makes its decisions on the budget in the form of appropriations bills.

Unlike the federal government, the state’s chief executive in 44 states has the power of line-item veto, which means the governor can reduce or eliminate, but not increase, specific items in the budget legislation. Line-item veto power allows the governor to insist on certain items in the budget and exert additional influence over the legislative process before the budget legislation reaches the governor’s desk.

Stage 3: Budget Execution

The governor’s signing appropriations legislation signals the beginning of the execution stage of the budget cycle. Next, the budget office issues detailed spending plans and instructions. The agencies rebudget the funds appropriated in the legislation. The governor assumes responsibility for implementing the budget, although the various state agencies share this responsibility and the state’s budget office is highly involved. In 33 states, the governor has the authority to withhold funds from agencies even if the money has been appropriated by the legislature. The predominant reason for this authority and its use is a shortfall of revenue (White 2017).

For detailed information on state budget processes for all 50 states, see Budget Processes in the States at www.nasbo.org/reports-data/budget-processes-in-the-states.

Stage 4: Audit

States monitor and review agency performance and may conduct program audits or evaluations of selected programs. In addition, states have a financial postaudit. Audits may be administrative reviews or more official performance audits with published results available to other government officials and the public. Agency officials or the legislature will act on significant audit findings and recommendations.

From Formulation to Implementation

When a legislature, whether the US Congress or a state legislature, approves proposed legislation, and the chief executive, whether the president or a governor, signs it, the policymaking process crosses an important threshold. The point at which proposed legislation is formally enacted into law is the point of transition from policy formulation to policy implementation. As shown in exhibit 6.1, the formal enactment of legislation bridges the formulation and implementation phases of policymaking and triggers the implementation phase. Policy implementation is considered in the next chapter.

Summary

The policy formulation phase of policymaking involves agenda setting and the development of legislation. Agenda setting, which we discussed in chapter 5, entails the confluence of problems, possible solutions to those problems, and political circumstances that creates a window of opportunity for certain problem–possible solution combinations to progress to the development of legislation.

Legislation development, the other component of policy formulation and the central topic of this chapter, follows carefully choreographed steps that include the drafting and introduction of legislative proposals, their referral to appropriate committees and subcommittees, House and Senate floor action on proposed legislation, conference committee action when necessary, and presidential action on legislation voted on favorably by the legislature. These steps apply whether the legislation is new or, as is often the case, an amendment of prior legislation.

The tangible final products of legislation development are new public laws, amendments to existing ones, or budgets, in the case of legislation development in the budget process. At the federal level, laws are first printed in pamphlet form called slip law. Subsequently, laws are published in the Statutes at Large and then incorporated into the US Code.

Review Questions

- Discuss the link between agenda setting and the development of legislation.

- Describe the steps in legislation development.

- Discuss the various sources of ideas for legislative proposals.

- What congressional legislative committees are most important to health policy? Briefly describe their roles.

- Describe the federal budget process. Include the relationship between the federal budget and health policy in your response.

References

Altman, S., and D. Shactman. 2011. Power, Politics and Universal Health Care. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Amadeo, K. 2019. “Federal Budget Process.” Published March 13. www.thebalance.com/federal-budget-process-3305781.

Avik, R. 2012. “The Tortuous History of Conservatives and the Individual Mandate.” Forbes. Published February 7. www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2012/02/07/the-tortuous-conservative-history-of-the-individual-mandate/.

Cannan, J. 2013. “A Legislative History of the Affordable Care Act: How Legislative Procedure Shapes Legislative History.” Law Library Journal 105 (2): 131–73.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2020. “Policy Basics: Introduction to the Federal Budget Process.” Updated April 2. www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=155.

Congress.gov. 2019a. “Sustaining Excellence in Medicare Act of 2019.” Published August 6. www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3253.

———. 2019b. “Committees of the U.S. Congress.” Accessed December 31. www.congress.gov/committees.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2020. “Introduction to CBO.” Accessed January 15. www.cbo.gov/about/overview.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2020. “About GAO.” Accessed January 15. www.gao.gov/about/index.xhtml.

Hacker, J. S. 2010. “The Road to Somewhere: Why Health Reform Happened; Or Why Political Scientists Who Write About Public Policy Shouldn’t Assume They Know How to Shape It.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (3): 861–76.

———. 1997. The Road to Nowhere. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hacker, J. S., and T. Skocpol. 1997. “The New Politics of U.S. Health Policy.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 22 (2): 315–38.

Heniff, B., Jr., M. S. Lynch, and J. Tollestrup. 2012. Introduction to the Federal Budget Process. Congressional Research Service. Published December 3. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/98-721.pdf.