CHAPTER

5

POLICY FORMULATION: AGENDA SETTING

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

- define agenda setting,

- understand what opens a window of opportunity in agenda setting,

- describe how problems emerge for consideration in policymaking,

- appreciate the role of research in selecting possible solutions to problems,

- describe the role of political circumstances in agenda setting,

- understand the role of interest groups in agenda setting,

- describe the tactics used by interest groups to influence the policy agenda,

- understand the role of governors or the president in agenda setting, and

- describe and explain the evolving nature of the health policy agenda.

This chapter and the next examine in greater detail the formulation phase of the health policymaking process described and modeled in chapter 4. This chapter focuses on agenda setting. Chapter 6 focuses on the development of legislation. These chapters apply the model to health policymaking almost exclusively at the national level of government and emphasize the legislative process. However, as is true of previous chapters, much of what is said here about the process of public policymaking also applies at the state and local levels. The contexts, participants, and specific mechanisms and procedures obviously differ among the three levels, but the core process typically is similar. Remember from the discussion in chapter 4 that the formulation phase of health policymaking is made up of two distinct and sequential parts: agenda setting and legislation development (see the darkly shaded portion of exhibit 5.1). Each part involves a complex set of activities in which policymakers engage with those who seek to influence their decisions and actions, but policy formulation begins with agenda setting.

EXHIBIT 5.1 Policymaking Process: Agenda Setting in the Formulation Phase

Long Description

The details of the diagram are as follows:

The formulation phase, implementation phase, and the modification phase are connected to one another in the external environment. The formulation phase shows the agenda settings: problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances leading to a window of opportunity for the development of legislation which again leads to the agenda setting.

The implementation phase shows designing, rulemaking, operating, and evaluating are interconnected to one another. The formulation phase and the implementation phase are bridged by formal enactment of legislation.

The modification phase reads “All decisions made in the formulation and implementation phases can be revisited and modified. Most policymaking is modification of prior authoritative decisions.”

The external environment reads “Many variables, arising from outside the policymaking process, affect and are affected by the authoritative decisions made within the process. Important environmental variables include the situations and preferences of individuals, organizations, and groups, as well as biological, biomedical, cultural, demographic, ecological, economic, ethical, legal, psychological, science, social, and technological variables.”

The formulation phase, implementation phase, and modification phase reads “Policymakers in all three branches of government make policy in the form of position-appropriate, or authoritative, decisions. Their decisions differ in that the legislative branch is primarily involved in formulation, the executive branch is primarily involved in implementation, and both are involved in modification of prior decisions or policies. The judicial branch interprets and assesses the legality of decisions made within all three phases of the policymaking process.”

The window of opportunity reads “A window of opportunity opens for possible progression of issues through formulation, enactment, implementation, and modification when there is a favorable confluence of problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances.”

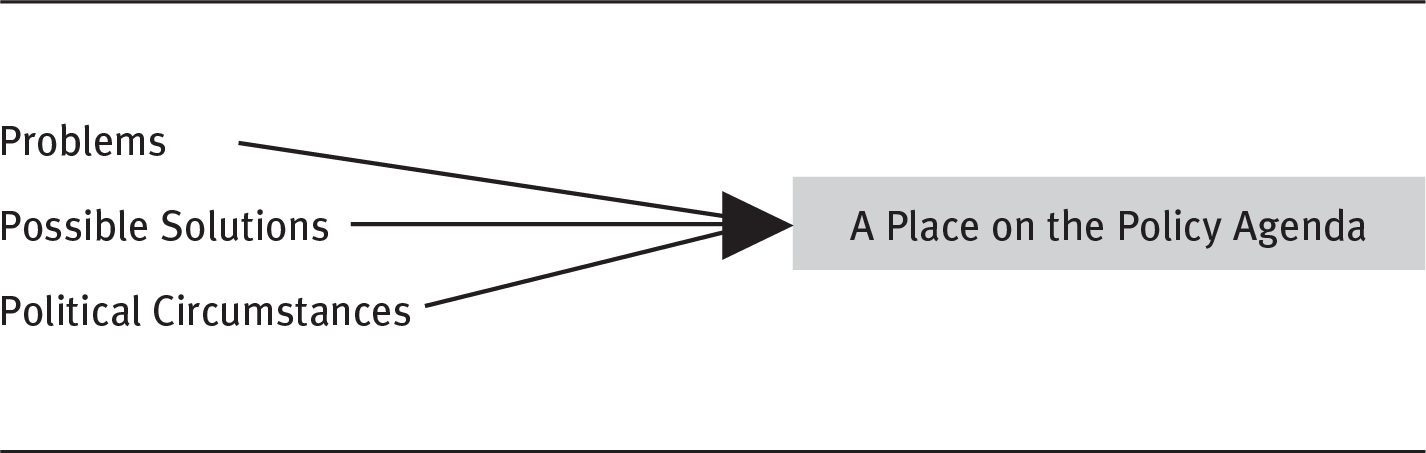

Agenda Setting

As noted in chapter 4, agenda setting is deciding what to make decisions about in the policy formulation phase of policymaking. It is a crucial initial step in the process. Kingdon (2010) describes agenda setting in public policymaking as a function of the confluence of three streams of activity: problems, possible solutions to the problems, and political circumstances. According to Kingdon’s conceptualization, when problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances flow together in a favorable alignment, a “policy window” or “window of opportunity” opens. When a policy window opens, a problem–potential solution combination that might lead to a new public law or an amendment to an existing one emerges from the set of competing problem–possible solution combinations and moves forward in the policymaking process (see exhibit 5.2).

EXHIBIT 5.2 Agenda Setting as the Confluence of Problems, Possible Solutions, and Political Circumstances

An illustration shows the problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances have a place on the policy agenda.

Current health policies in the form of public laws—such as those pertaining to environmental protection, licensure of health-related practitioners and organizations, expansion of the Medicaid program, cost containment of the Medicare program, funding for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) research or women’s health, and regulation of pharmaceuticals pricing—exist because problems or issues emerged from agenda setting and triggered changes in policy. However, the existence of these problems alone was not sufficient to trigger the development of legislation intended to address them.

The existence of health-related problems, even serious ones such as inadequate health insurance coverage for millions of people or the continuing widespread use of tobacco products, does not always lead to policies intended to solve or ameliorate them. There also must be potential solutions to the problems and the political will to enact specific legislation to implement one or more of those solutions. Agenda setting is best understood in the context of its three key variables: problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances. Policymakers and interest groups may—and often do—disagree on elements of the policymaking process. Certainly, disagreement affects the level of political will a policymaker might have regarding an issue. A member of Congress who wants to be reelected will consider carefully any involvement in a contentious debate. Likewise, an interest group could believe its best strategy may be minimizing or maximizing the scope of the problem of interest.

Problems

The breadth of problems that can initiate agenda setting is reflected in the broad range of health policies. Chapter 1 discussed how health is affected by several determinants: the physical environments in which people live and work; their behaviors and biology; social factors; and the type, quality, and timing of health services they receive.

Beyond these determinants, as shown in the external environment component of exhibit 5.1, the situations and preferences of individuals, organizations, and groups as well as biological, biomedical, cultural, demographic, ecological, economic, ethical, legal, psychological, science, social, and technological variables affect policymaking throughout the process. These inputs join with the results and consequences of the policies produced through the ongoing policymaking process to supply agenda setters continuously with a massive pool of contenders for a place on that agenda. From among the multiple contenders, certain problems find a place on the agenda while others do not.

The problems that eventually lead to the development of legislation are generally those that some policymakers broadly identify as important and urgent. (Keep in mind that this is a political process; not all policymakers are equally powerful. A senior member in the majority party of Congress can more easily get something on the policy agenda in a meaningful place than a freshman member in the minority party.) Problems that do not meet these criteria languish at the bottom of the list or never find a place on the agenda.

Price (1978), in a classic article, argues that whether a problem receives aggressive congressional intervention in the form of policymaking depends on its public salience and the degree of group conflict surrounding it. He defines a publicly salient problem or issue as one with a high actual or potential level of public interest. Conflictive problems or issues are those that stimulate intense disagreements among interest groups or those that pit the interests of groups against the larger public interest. Price contends that the incentives for legislators to intervene in problems or issues are greatest when salience is high and conflict is low. Conversely, incentives are least when salience is low and conflict is high.

An example of profound salience and equally profound conflict is the epidemic of gun violence. Both advocates of gun control measures and defenders of the gun rights hold views that are extremely intense (which is not the same as an extreme position; there are some of those in each camp as well). Gun control has a wide variety of meanings. The term can mean something as anodyne as (1) more rigorous background checks for buyers to something a bit more restrictive such as (2) denying access to semiautomatic weapons and any devices that can be used to convert them to fully automatic weapons, or even to (3) completely banning all firearms, and a host of positions in between. Proponents believe that making it harder to get guns to the public will result in a decrease of gun violence. Some opponents would accept more rigorous background checks, and some would accept restrictions on access to certain kinds of weapons. Other opponents, however, look to the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights to assert an unfettered right to bear arms, objecting to any form of firearm regulation. Each side of the debate has an extreme position—complete ban versus no regulation—and a broad spectrum of more nuanced positions. The overall picture, however, is an issue with very high conflict and mixed salience. When the issue gets thrown into the same cauldron as taxes, healthcare, national security, and all the problems that make up everyday light, consensus is elusive. A political (and policy) standoff is the result.

Conversely, the opioid addiction problem that began to surface in 2017 and 2018 is salient to public policy because of the large number of overdose deaths and the loss of productivity from those who are addicted. Controversy over the need for action is minimal; it is one of the few mental health–related initiatives on which there is broad agreement. As a result, the Congress has acted by providing grant funding to comprehensive recovery centers and facilitating access to medication-assisted treatment programs (Itkowitz 2018). Problems that lead to attempts at policy solutions find their place on the agenda along one of several paths. Some problems emerge because trends in certain variables eventually reach unacceptable levels—at least, levels unacceptable to some policymakers. Growth in the number of uninsured and cost escalation in the Medicare program are examples of trends that eventually reached levels at which policymakers felt compelled to address the underlying problems through legislation. Both problems are addressed in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Problems also can be spotlighted by their widespread applicability (e.g., the high cost of prescription medications to millions of Americans) or by their sharply focused impact on a small but powerful group whose members are directly affected (e.g., the high cost of medical education). Another example of a widespread problem that led to specific legislation was that a large number of people felt locked into their jobs because they feared that preexisting health conditions might prevent them from obtaining health insurance if they found new positions. In response to this problem, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-191) significantly enhanced the portability of health insurance coverage. Other provisions in this law guarantee availability and renewability of health insurance coverage for certain employees and individuals and an increase in the tax deduction for health insurance purchased by the self-employed.

Moreover, just because policymakers find consensus in recognition that a problem is widespread and perhaps little conflict that it should be solved, the presence of conflicts over the possible solutions generally result in inaction. That seems to be the case with regard to ever-increasing prices for prescription medications. There is general agreement that increasing prices are challenging to a growing number of Americans. However, participants experience a high degree of conflict over the possible solutions, which include permitting importation from Canada, allowing Medicare to negotiate prices directly, and legally regulating pharmaceutical prices, among others. Failure to achieve a meaningful consensus around any of these solutions means no meaningful action will take place so long as that fractured perspective continues to exist. Some problems gain their place on the agenda or strengthen their hold on a place because they are closely linked to other problems that already occupy secure places. The coronavirus pandemic of 2020 provides a good example. Congress and the executive branch were committed to finding ways to both slow the spread of the disease as well as provide financial assistance for people and businesses suffering adverse impacts from the disease. Thus, the Payroll Protection Plan emerged to help small businesses retain employees in spite of disease mitigation efforts that caused losses in business revenue. Providing such payroll assistance—and thus keeping employees covered by their employers’ health insurance—would not have been on the agenda without the crisis brought on by the pandemic.

Some problems emerge more or less simultaneously along several paths. Typically, problems that emerge this way become prominent on the policy agenda. For example, the problem of the high cost of health services for the private and public sectors has long received attention from policymakers. Though the rate of growth in health costs has slowed in the past few years, these costs remain high and problematic (Kamal, McDermott, and Cox 2019).This problem emerged along a number of mutually reinforcing paths. In part, the cost problem has been prominent because the cost trend data disturb many people. The data contribute to and reinforce a widespread acknowledgment of the problem of health costs in public poll after public poll and have attracted the attention of some of those who pay directly for health services through the provision of health insurance benefits, especially the politically powerful business community. Finally, the health cost problem as it relates to public expenditures—for the Medicare and Medicaid programs especially—has also been linked at times to the need to control the federal budget.

The variables of healthcare costs and the escalating federal budget form a combination of interacting circumstances, which is largely why this problem remains perennially prominent in the minds of many policymakers. The persistence of this problem, and many others, is also related to the difficulty of finding and pursuing potential solutions.

Possible Solutions

The second variable in agenda setting (see exhibit 5.2) is the existence of possible solutions to problems. Problems themselves—even serious, fully acknowledged ones with widespread implications such as the high cost of healthcare, poor quality, and uneven access to needed health services—do not invariably lead to remedial policies. Potential solutions must accompany them. The availability of possible solutions depends on the generation of ideas and, usually, a period of idea testing and refinement. As the following box, reprinted from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), illustrates, numerous ideas might serve as solutions to problems, either in single application or in various combinations.

Innovation Models

The [CMS] Innovation Center develops new payment and service delivery models in accordance with the requirements of Section 1115(a) of the Social Security Act. Additionally, Congress has defined—both through the ACA and previous legislation—a number of specific demonstrations to be conducted by CMS. These research and demonstration projects are exempt from the Common Rule under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(5). For additional guidance, refer to the OHRP [Office of Human Research Protections] Revised Common Rule Q&As on Exemptions.

The Innovation Center also plays a critical role in implementing the Quality Payment Program, which Congress created as part of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) to replace Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate formula to pay for physicians’ and other providers’ services. In this new program, clinicians may earn incentive payments by participating to a sufficient extent in Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). In Advanced APMs clinicians accept some risk for their patients’ quality and cost outcomes and meet other specified criteria.

The Innovation Center is working in consultation with clinicians to increase the number and variety of models available to ensure that a wide range of clinicians, including those in small practices and rural areas, have the option to participate. [Author’s note: For more details, see CMS (2019)].

Our Innovation Models are organized into seven categories.

Accountable Care

Accountable Care Organizations and similar care models are designed to incentivize health care providers to become accountable for a patient population and to invest in infrastructure and redesigned care processes that provide for coordinated care, high quality and efficient service delivery.

Episode-Based Payment Initiatives

Under these models, health care providers are held accountable for the cost and quality of care beneficiaries receive during an episode of care, which usually begins with a triggering health care event (such as a hospitalization or chemotherapy administration) and extends for a limited period of time thereafter.

Primary Care Transformation

Primary care providers are a key point of contact for patients’ health care needs. Strengthening and increasing access to primary care is critical to promoting health and reducing overall health care costs. Advanced primary care practices—also called “medical homes”—utilize a team-based approach, while emphasizing prevention, health information technology, care coordination, and shared decision making among patients and their providers.

Initiatives Focused on the Medicaid and CHIP Population

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are administered by the states but are jointly funded by the federal government and states. Initiatives in this category are administered by the participating states.

Initiatives Focused on the Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees

The Medicare and Medicaid programs were designed with distinct purposes. Individuals enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (the “dual eligibles”) account for a disproportionate share of the programs’ expenditures. A fully integrated, person-centered system of care that ensures that all their needs are met could better serve this population in a high quality, cost effective manner.

Initiatives to Accelerate the Development and Testing of New Payment and Service Delivery Models

Many innovations necessary to improve the health care system will come from local communities and health care leaders from across the entire country. By partnering with these local and regional stakeholders, CMS can help accelerate the testing of models today that may be the next breakthrough tomorrow.

Initiatives to Speed the Adoption of Best Practices

Recent studies indicate that it takes nearly 17 years on average before best practices—backed by research—are incorporated into widespread clinical practice—and even then the application of the knowledge is very uneven. The Innovation Center is partnering with a broad range of health care providers, federal agencies, professional societies and other experts and stakeholders to test new models for disseminating evidence-based best practices and significantly increasing the speed of adoption.

Source: CMS (2020).

Although varying in size and quality, alternative solutions almost always exist. An excessive number of alternatives can slow the problem’s advancement through the policymaking process as the relative merits of the competing alternatives are considered. Without at least one solution believed to have the potential to solve it, however, a problem does not advance, except perhaps in some spurious effort to create the illusion that it is being addressed.

When alternative solutions do exist, policymakers must decide whether the potential solutions are worth developing into legislative proposals. Frequently, multiple solutions to a particular problem will be considered worthy of such action, resulting in the simultaneous development of several competing legislative proposals. Competing proposals tend to make agenda setting rather chaotic, although rigorous research and analysis can sometimes provide more clarity.

Research and Analysis in Defining Problems and Assessing Alternatives

Health services research “is the science of study that determines what works, for whom, at what cost, and under what circumstances. It studies how our health system works, how to support patients and providers in choosing the right care, and how to improve health through care delivery” (AcademyHealth 2020). It has been defined more succinctly as “scientific inquiry into the ways in which health services are delivered to various constituents” (Forrest et al. 2008). Health services researchers seek to understand how people obtain access to healthcare services, the costs of the services, and the results for patients using this care. The main goals of this type of research include identifying the most effective ways to organize, manage, finance, and deliver high-quality care and services and, more recently, how to reduce medical errors and improve patient safety. Health services research, along with much biomedical research, contributes to problem identification and specification and the development of possible solutions. Thus, research can help establish the health policy agenda by clarifying problems and potential solutions. Well-conducted health services research provides policymakers with facts that might affect their decisions.

Policymakers generally value the input of the research community sufficiently to fund much of its work through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and other agencies. AHRQ, the health services research arm of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), complements the biomedical research mission of its sister agency, NIH. AHRQ is the federal government’s focal point for research to enhance the quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness of health services and access to those services.

Readers should note, however, that political support for scientific research waxes and wanes over time. In some eras, the predominant political ideology suggests a greater degree of ambivalence toward research than at other times. At the time of the ACA’s enactment, there was a greater degree of appreciation for the potential of scientific research and accomplishment than in the decade that followed.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. In addition to these traditional research and analysis agencies, the ACA significantly improved the government’s ability to use analysis and research in guiding agenda setting. For example, the ACA created the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (the CMS Innovation Center), appropriating $10 billion for the fiscal year (FY) 2011–2019 period, along with $10 billion for each subsequent ten-year period. The purpose of the CMS Innovation Center is to test and implement innovative payment and service delivery models. These models are intended to reduce program expenditures under Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) while preserving or enhancing the quality of care furnished under these programs (Redhead 2017).

Independent Payment Advisory Board. The ACA also established and funded an Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) to make recommendations to Congress for achieving specific Medicare spending reductions if costs exceed a target growth rate. IPAB’s recommendations are to take effect unless Congress overrides them, in which case Congress would be responsible for achieving the same level of savings.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Further supporting the research and analysis basis for policymaking, the ACA established a trust fund to finance the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). The main purpose of PCORI is to support the conduct of comparative clinical effectiveness research (PCORI 2017). Appropriations to this trust fund totaled $210 million for FY 2010–2012. In FY 2013–2019, the fund received $150 million annually for a total of $1.26 billion over that ten-year period. The agency describes its funding (PCORI 2017):

The PCOR Trust Fund receives income from three funding streams: appropriations from the general fund of the Treasury, transfers from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid trust funds, and a fee assessed on private insurance and self-insured health plans (the PCOR fee).

PCORI receives 80 percent of the monies collected by the PCOR Trust Fund to support its research funding and operations. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) receives the other 20 percent of trust fund monies to support dissemination and research capacity-building efforts (the majority of HHS’s share goes to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

Research and analysis play two especially important roles in agenda setting. First, an important documentation role is played through the gathering, cataloging, and correlating of facts related to health problems and issues. For example, researchers documented the dangers of tobacco smoke; the presence of HIV; the numbers of people living with AIDS, a variety of cancers, heart disease, and other diseases; the effect of poverty on health; the number of people who lack health insurance coverage; the existence of health disparities among population segments; and the dangers imposed by exposure to various toxins in people’s physical environments. Quantification and documentation of health-related problems give the problems a better chance of finding a place on the policy agenda.

The second way research informs, and thus influences, the health policy agenda is through analyses to determine which policy solutions may work or to compare alternative solutions. Health services research provides valuable information to policymakers as they propose, consider, and prioritize alternative solutions to problems. Often taking the form of demonstration projects intended to provide a basis for determining the feasibility, efficacy, or basic workability of a possible policy intervention, research-based recommendations to policymakers can play an important role in policy agenda setting. Potential solutions that might lead to public policies—even if the policies themselves are formulated mainly on political grounds—must stand the test of plausibility. Research that supports a particular course of action or attests to its likelihood of success—or at least to the probability that the course of action will not embarrass proponents—can make a significant contribution to policymaking by helping shape the policy agenda. What research cannot do for policymakers, however, is make decisions for them. Every difficult decision regarding the health policy agenda ultimately rests with policymakers.

It should also be noted, however, that political influence can sideline research that might be useful in addressing social issues that become public health issues. In 1996, Congress adopted the Dickey Amendment as part of an omnibus appropriations bill that specified that “none of the funds made available in this title may be used, in whole or in part, to advocate or promote gun control” (US Congress 1996). The amendment became an annual tradition in the appropriations process. While no agency took a position regarding gun control, scientists erred on the side of caution, understanding that any research on gun violence might reach a conclusion that appeared to favor limiting availability of firearms. For that reason, neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) nor the NIH engaged in any research of the underlying causes of gun violence for 20 years (Rostron 2018). In response to a wave of mass shootings in 2018 and 2019, however, Congress appropriated $25 million for the NIH and CDC for gun violence research as part of an appropriations bill to avoid a government shutdown and did not include the Dickey Amendment (Stracqualursi 2019). This shift represents a policy modification arising from changed cultural circumstances. Further, it demonstrates the value of research in public health. By ending the prohibition and specifically funding this kind of research, Congress has demonstrated the value that research can have in setting the public policy agenda.

Making Decisions About Alternative Possible Solutions

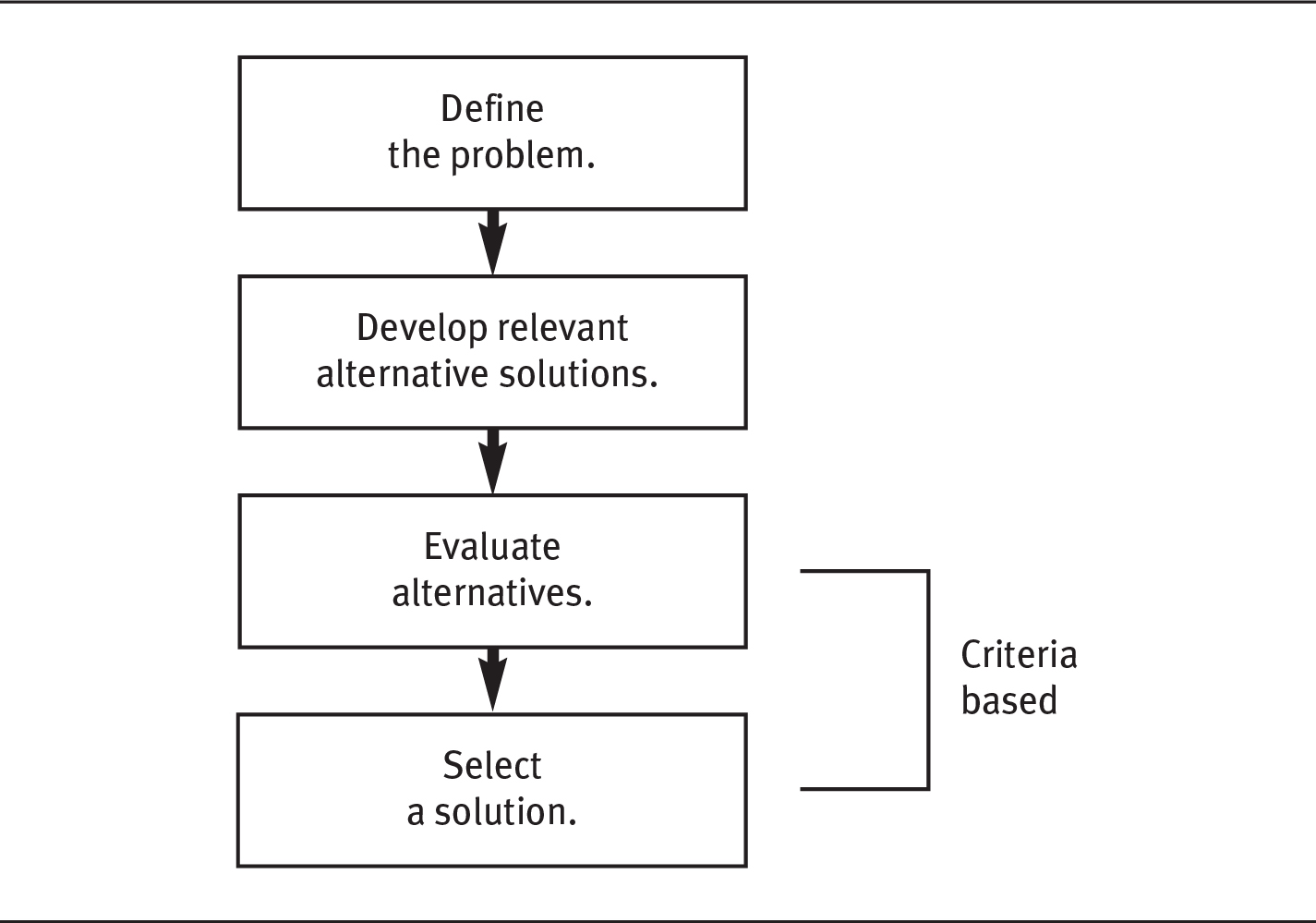

Problems that require decisions and alternative possible solutions are two prerequisites for using the classical, rational model of decision-making outlined in exhibit 5.3. This model shares the basic pattern of the organizational decision-making process typically followed in the private and public sectors.

EXHIBIT 5.3 The Rational Model of Decision-Making

A flow diagram shows a model for decision making. The decision-making process is as follows: define the problem, develop relevant alternative solutions, evaluate alternatives, and select a solution. The last two steps are criteria based.

However, differences between the two sectors in the use of this model typically arise with the introduction of the criteria used to evaluate alternative solutions.

Some of the criteria used to evaluate and compare alternative solutions in the private and public sectors are the same or similar. For example, the criteria set in both sectors usually include consideration of whether a particular solution will actually solve the problem, whether it can be implemented using available resources and technologies, its costs and benefits relative to other possible solutions, and the results of an advantage-to-disadvantage analysis of the alternatives.

In both sectors, high-level decisions have scientific or technical, political, and economic dimensions. The scientific or technical aspects can be more difficult to factor into decisions when the evidence is in dispute, as it often is (Atkins, Siegel, and Slutsky 2005; Steinberg and Luce 2005). The most pervasive difference between the criteria sets used in the two sectors, however, is in the roles political concerns and considerations play. Decisions made by public-sector policymakers must reflect greater political sensitivity to the public at large and to the preferences of relevant individuals, organizations, and interest groups. The greater political sensitivity required helps explain the importance of the third variable in agenda setting, political circumstances.

Political Circumstances

A problem that might be solved or ameliorated through policy, even in combination with a possible solution to that problem, is not sufficient to move the problem–solution combination forward in the policymaking process. A political force, or what is sometimes called political will, is also necessary.

Thus, the political circumstances surrounding each problem–potential solution form the crucial third variable in creating a window of opportunity through which problems and potential solutions move toward development of legislation. This variable is generally as important as the other two variables in this complex equation (see exhibit 5.2), and in times of crisis such as the global financial crisis that emerged in 2008, political circumstances can be by far the most significant factor in stimulating policy changes. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5) is an example of this phenomenon.

The establishment of a political thrust forceful enough to move policymakers to act on a health-related problem is often the most challenging variable in the problem’s emergence on the policy agenda and progression to legislation development. This variable can be seen clearly in the passage of the ACA in 2010. Following decades of failed attempts to reform healthcare in the United States fundamentally, why did major health reform occur in 2010? The answer to this question is complex, but it certainly involves the political circumstances surrounding the issue. As Hacker suggests (2010), the election of a Democratic president and strengthening of the Democratic majority in Congress in 2008 were essential. Further, in this particular case, President Barack Obama was resolute in his determination to pass major healthcare reform legislation early in his tenure. Hacker further points out that the political circumstances in which the ACA occurred included not only a Democratic majority in Congress but a more homogeneously liberal composition of members of Congress.

Whether the political circumstances attendant on any problem–potential solution combination are sufficient to actually open a window of opportunity depends on the competing entries on the policy agenda. The array of problems is an important variable in agenda setting. When the nation is involved in serious threats to its national security or its civil order, for example, or when a state is in the midst of a sustained recession, health policy will be treated differently. In fact, health policy, which is often a high priority for the American people, can be pushed to a secondary position at times.

The political circumstances surrounding any problem–potential solution combination include such factors as the relevant public attitudes, concerns, and opinions; the preferences and relative ability of various interest groups to influence political decisions regarding the problem or the way it is addressed; and the positions of involved key policymakers in the executive and legislative branches of government. Each of these factors can influence whether a problem is addressed through policy and the shape and scope of any policy developed to address the problem. Two factors in particular exert great influence in establishing the policy agenda. These are interest groups and the chief executive (president, governor, mayor). The role of each in agenda setting is discussed in the next two sections.

Interest Group Involvement

As we discussed in chapter 2, interest groups are ubiquitous in the policy marketplace. The agenda setting activities and legislation development in the policy formulation phase are no exception (see exhibit 5.1). Interest groups and their representatives are omnipresent throughout the policy process.

To appreciate fully the role of interest groups in setting the policy agenda, consider the role of individual Americans. In a representative form of government, such as that of the United States, individual members of society, unless they are among the elected representatives, usually do not vote directly on policies. They can, however, vote on policymakers. Thus, policymakers are interested in what individuals, especially voters, want, even when that is not easy to discern.

However, one of the great myths about democratic societies is that their members, when confronted with tough problems such as the high cost of healthcare for everyone, the lack of health insurance for many, or the existence of widespread disparities in health among segments of the society, ponder the problems carefully and express their preferences to their elected officials, who then factor these opinions into their decisions about how to address the problems through policy. Sometimes these steps take place, but even when the public expresses its opinions about an issue, the result is clouded by the fact that the American people are heterogeneous in their views. Opinions are mixed on health-related problems and their solutions. Public opinion polls can help sort out conflicting opinions, but polls are not always straightforward undertakings. In addition, individuals’ opinions on many issues are subject to change.

The public’s thinking on difficult problems that might be addressed through public policies evolves through predictable stages, beginning with awareness of the problem and ending with judgments about its solution (Yankelovich and Friedman 2010). In between, people explore the problem and alternative solutions with varying degrees of success. The journey between awareness and judgment can be more of a short, emotive process than an intellectual inquiry. The progress of individuals through these stages is related to their views on the problems and solutions. Those views are most likely a product of self-interest: for example, a pharmaceutical sales representative whose compensation is based on commissions is less likely to be supportive of legislation that would regulate the price of prescription medications than a senior citizen on a fixed income whose health requires that they take several prescriptions a day.

The diversity among members of society, and hence organizations and interest groups, and the fact that individual views on problems and potential solutions evolve over time, explain in large part the greater influence of organizations and interest groups in shaping the policy agenda. Interest groups in particular can exert extraordinary influence in policy markets, as we discussed in chapter 2.

Whether made up of individuals or organizations, interest groups are often able to present a unified position to policymakers on their preferences regarding a particular problem or its solution. A unified position is far easier for policymakers to assess and respond to than the diverse opinions and preferences of many individuals acting alone. Although individuals tend to be keenly interested in their own health and the health of those they care about, their interests in specific health policies tend to be diffuse. These diffused interests stand in contrast to the highly concentrated interests of those who earn their livelihood in the health domain or who stand to gain other benefits there. This phenomenon is not unique to health. In general, the interests of those who earn their livelihood in any industry or economic sector are more concentrated than the interests of those who merely use its outputs.

One result of the concentration of interests is the formation of organized interest groups that seek to influence the formulation, implementation, and modification of policies to some advantage for the group’s members. Because all interest groups seek policies that favor their members, their own agendas, behaviors, and preferences regarding the larger public policy agenda are often predictable.

Feldstein (2019) argues, for example, that all interest groups representing health services providers seek through legislation to increase the demand for members’ services, limit competitors, permit members to charge the highest possible prices for their services, and lower their members’ operating costs as much as possible. Likewise, an interest group representing health services consumers logically seeks policies that minimize the costs of the services to its members, ease their access to the services, increase the availability of the services, and so on. Essentially, interest groups are human nature at work.

As we noted earlier, interest groups frequently play influential roles in setting the nation’s health policy agenda, as they subsequently do in the development of legislation and the implementation and modification of health policies. These groups sometimes proactively seek to stimulate new policies that serve the interests of their members. Alternatively, they sometimes reactively seek to block policy changes that they believe do not serve their members’ best interests.

Interest Groups Are Ubiquitous in Health Policymaking

A significant feature of the policymaking process in the United States is the presence of interest groups that exist to serve the collective interests of their members. These groups analyze the policymaking process to discern policy changes that might affect their members and inform them about such changes. They also seek to influence the process to provide the group’s members with some advantage. The interests of their constituent members define the health policy interests of these groups.

Health services providers rely heavily on interest groups to influence policymaking to their advantage, as do other types of health-related organizations. Some interest groups are consumer based. Without being exhaustive, some of the important health-related interest groups are noted next.

Hospitals can join the American Hospital Association (www.aha.org), long-term care organizations can join the American Health Care Association (www.ahca.org) or the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging, now known as LeadingAge (www.leadingage.org), and health insurers and health plans can join America’s Health Insurance Plans (www.ahip.org).

Other interest groups represent individual health practitioners. Physicians can join the American Medical Association (AMA; www.ama-assn.org). African American physicians may choose to join the National Medical Association (www.nmanet.org), and female physicians may choose to join the American Medical Women’s Association (www.amwa-doc.org). In addition, physicians have the opportunity to affiliate with groups, usually termed colleges or academies, where membership is based on medical specialty. Prominent examples are the American College of Surgeons (www.facs.org) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (www.aap.org). Other personal membership groups include the American College of Healthcare Executives (www.ache.org), the American Nurses Association (www.ana.org), and the American Dental Association (www.ada.org), to name a few.

Often, in addition to national interest groups, health services provider organizations and individual practitioners can join state and local groups—usually affiliates or chapters of national groups—that also represent their interests. For example, states have state hospital associations and state medical societies. Many urban centers and densely populated areas even have groups at the regional, county, or city level.

There are numerous other health-related interest groups in addition to those whose members provide health services directly. Examples include the following:

- America’s Health Insurance Plans (www.ahip.org)

- Association of American Medical Colleges (www.aamc.org)

- Association of University Programs in Health Administration (www.aupha.org)

- Biotechnology Industry Organization (www.bio.org)

- Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association (www.bcbs.com)

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (www.phrma.org)

Like groups whose members are health services providers, these groups focus particularly on policies that affect their members directly.

Moreover, a large number of patient advocacy groups highlight the need for specific disease remedies. An unknown number of these groups may have relationships with the pharmaceutical industry—indeed, with companies that provide drugs for the specific disease highlighted by the organization. In other words, the positions taken by the group may more nearly reflect those of the financial sponsor than of the patients or their caregivers. As many as 83 percent of such organizations receive financial support from the industry, while as many as 39 percent include industry representatives on their boards. Publicly available data are limited, so observing this trend in detail is impossible (McCoy et al. 2017).

There are also interest groups that serve consumers. Reflecting the populations from which their members are drawn, groups with individual member constituencies are diverse. Some are based in part on a shared characteristic such as race, gender, age, or connection to a specific disease or condition. Examples include the following:

- Alliance for Retired Americans (www.retiredamericans.org)

- AARP (www.aarp.org)

- American Heart Association (www.heart.org)

- Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities (www.c-c-d.org)

- Families USA (www.familiesusa.org)

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP; www.naacp.org)

- National Organization for Women (NOW; www.now.org)

Interest groups such as NAACP and NOW serve the health interests of their members as part of agendas focused broadly on racial and gender equality. Although the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution guarantees equal protection under the law, American history clearly shows how difficult this equality has been to achieve. Interest groups such as NAACP and NOW have made equality their central public policy goal at the polls; in the workplace; and in education, housing, health services, and other facets of life in the United States. Income inequality in the United States is the newest of these variables.

The specific health policy interests of groups representing African Americans include adequately addressing this population segment’s unique health problems: widespread disparities in health status and access to health services, higher infant mortality, higher exposure to violence among adolescents, higher levels of substance abuse among adults, and, compared to other segments of the population, earlier deaths from cardiovascular disease and other causes. Similarly, groups representing the interests of women seek to address their unique health problems. In particular, they focus on such interests as breast cancer, childbearing, osteoporosis, domestic violence, family health, and funding for biomedical research on women’s health problems.

A growing proportion of the American population is older than 65. Older adults have specific health interests related to their stage of life; as people age, they consume relatively more healthcare services, and their healthcare needs differ from those of younger people. They also become more likely to consume long-term care services and community-based services intended to help them cope with limitations in the activities of daily living.

In addition to their health needs, older citizens have a unique health policy history and, therefore, a unique set of expectations and preferences regarding the nation’s health policy. The Medicare program, a key feature of this history, includes extensive provisions for health benefits for older citizens. Building on the specific interests of older people and their preferences to preserve and extend their healthcare benefits through public policies, organizations such as AARP and the Alliance for Retired Americans (www.retiredamericans.org) play an important role in addressing the health policy interests of their members.

Other interest groups with individual constituencies reflect member interests based primarily on specific diseases or conditions, such as the American Cancer Society (www.cancer.org) or the Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities (www.c-c-d.org). The American Heart Association, for example, has 22.5 million volunteers and supporters pursuing the organization’s mission of building healthier lives free of cardiovascular diseases and stroke. The association pursues its mission through such avenues as direct funding of research, public and professional education programs, and community programs designed to prevent heart disease. It also seeks to serve its members’ interests through influencing public policy related to heart disease.

As the American Hospital Association (2019) notes on its web page, its federal policy agenda is organized into the following categories:

- Sustain the gains in health coverage

- Protect patient access to care

- Advance health system transformation

- Enhance quality and patient safety

- Promote regulatory relief

- Strengthen the workforce

Interest Group Tactics

As influential participants in public policymaking, interest groups are integral to the process. They are especially ubiquitous in the health domain. But how do they exert their influence? Interest groups rely heavily on four tactics: lobbying, electioneering, litigation, and (especially recently) shaping public opinion so that it might in turn influence the policymaking process to the groups’ advantage (Edwards, Wattenberg, and Lineberry 2012). Each of these tactics is described in the following sections.

Lobbying

This widely used influencing tactic has deep roots in public policymaking in the United States, and it involves large sums of money. Lobbying expenditures on health issues at the federal level were nearly $568 million in 2018 (Center for Responsive Politics 2019d). In the minds of many people, lobbying conjures a negative image of backroom deals and money exchanging hands for political favors. Ideally, however, it is nothing more than communicating with public policymakers to influence their decisions to be more favorable to, or at least consistent with, the preferences of the lobbyist and the organization they represent (Andres 2009; Herrnson, Shaiko, and Wilcox 2005).

Lobbying, the word for these influencing activities, and lobbyists, the word for people who do this work, arose in reference to the place where such activities first took place. “The term is believed to have originated in British Parliament, and referred to the lobbies outside the chambers where wheeling and dealing took place. ‘Lobbyist’ was in common usage in Britain in the 1840’s. Jesse Sheidlower, editor-at-large for the Oxford English Dictionary, believes the term was used as early as 1640 in England to describe the lobbies that were open to constituents to interact with their representatives” (Shannon 2009).

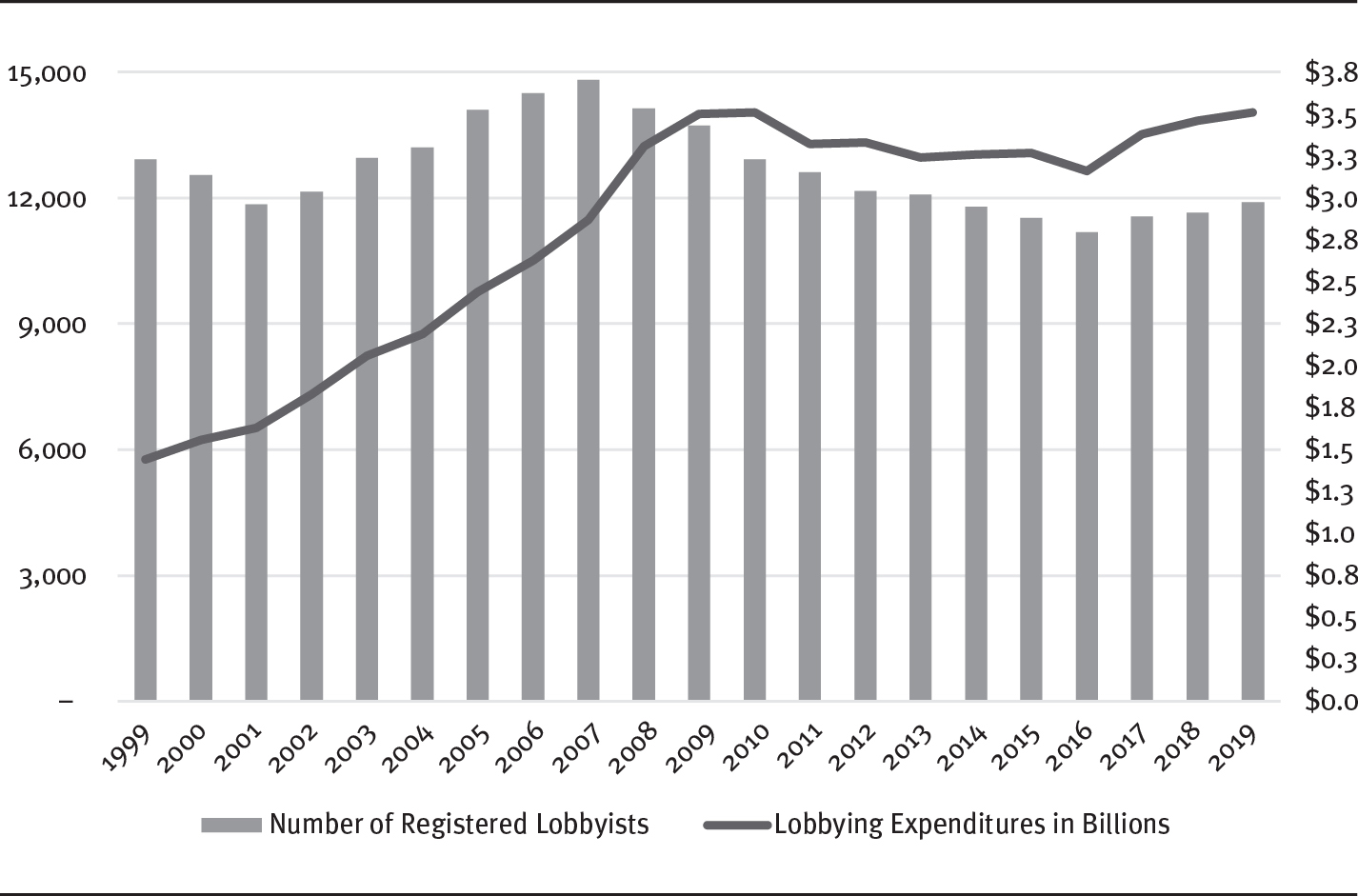

See exhibit 5.4 for a visual presentation of the number of lobbyists registered with the federal government. As you examine the graph, consider that the US House of Representatives has 435 members and the US Senate has 100. Granted, lobbyists also work with executive branch agencies, but the graph suggests that there are nearly 23 lobbyists for each member of Congress.

EXHIBIT 5.4 Number of Registered Lobbyists and Amount of Lobbying Expenditures (in billions)

Long Description

The horizontal axis ranges from 1999 to 2019 in unit increments. The vertical axis on the left ranges from 0 to 15,000 in increments of 3,000 and the vertical axis on the right range from 0.0 to 3.8 dollars in increments of 0.3. The number of registered lobbyists is as follows:

1999, 13,000; 2000, 12,500; 2001, 11,900; 2002, 12,300; 2003, 13,000; 2004, 13,500; 2005, 14,000; 2006, 14,500; 2007, 15,500; 2008, 14,000; 2009, 13,500; 2010, 13,000; 2011, 12,500; 2012, 12,500; 2013, 12,000; 2014, 11,900; 2015, 11,500; 2016, 11,000; 2017, 11,500; 2018, 11,500; and 2019, 12,000.

The lobbyists expenditures in billions are as follows: 1999, 1.4; 2000, 1.6; 2001, 1.8; 2002, 2.0; 2003, 2.1; 2004, 2.2; 2005, 2.5; 2006, 2.7; 2007, 2.8; 2008, 3.3; 2009, 3.4; 2010, 3.4; 2011, 3.3; 2012, 3.4; 2013, 3.3; 2014, 3.3; 2015, 3.3; 2016, 3.2; 2017, 3.4; 2018, 3.4; and 2019, 3.5.

All values are approximate.

Source: Adapted from Center for Responsive Politics (2019b).

The vast majority of lobbyists operate in an ethical and professional manner, effectively representing the legitimate interests of the groups they serve. However, the few who behave in a heavy-handed, even illegal manner have, to some extent, tarnished the reputations of all who do this work. Their image is further affected by the fact that their work, properly done, is essentially selfish in nature. Lobbyists seek to persuade others that the position of the interests they represent is the correct one. Lobbyists’ whole professional purpose is to persuade others to make decisions that are in the best interests of those who employ or retain them.

Opinions and results of studies on the effectiveness of lobbying are mixed at best (Bergan 2009). Some ambivalence over the role of lobbying derives from the inherent difficulty in isolating its effect from the other influencing tactics discussed later. There is no doubt that lobbying affects the policymaking process, but it seems to work best when applied to policymakers who are already committed, or at least sympathetic, to the lobbyist’s position on a public policy issue (Edwards, Wattenberg, and Lineberry 2012). Lobbyists certainly played a prominent role in the enactment of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (P.L. 108173); the ACA; and, as discussed in the next chapter, the 21st Century Cures Act, along with other health policies (Kersh 2014; Weissert and Weissert 2019). The influence lobbyists exert on policymaking is facilitated by several well-recognized sources (Godwin, Ainsworth, and Godwin 2013; Herrnson, Shaiko, and Wilcox 2005). Lobbyists can do the following:

- Be an important source of information for policymakers. Although most policymakers must be concerned with many policy issues simultaneously, most lobbyists can focus and specialize. They can become expert and can draw on the insight of other experts in the areas they represent.

- Assist policymakers with the development and execution of political strategy. Lobbyists typically are politically savvy and can provide what amounts to free consulting to the policymakers they choose to assist.

- Assist elected policymakers in their reelection efforts. (See the next section on electioneering.) This assistance can take several forms, including campaign contributions, votes, and workers for campaigns.

- Be important sources of innovative ideas for policymakers. Policymakers are judged on the quality of their ideas as well as their abilities to have those ideas translated into effective policies. For most policymakers, few gifts are as valued as a really good idea, especially when they can turn that idea into a bill that bears their name.

- Be friends with policymakers. Lobbyists are often gregarious and interesting people in their own right. They entertain, sometimes lavishly, and they are socially engaging. Many of them have social and educational backgrounds similar to those of policymakers. In fact, many lobbyists have been policymakers earlier in their careers. Friendships between lobbyists and policymakers are neither unusual nor surprising.

Not only is there an astounding number of lobbyists, but the amount of money spent by interest groups seeking to influence the process is likewise considerable (see exhibit 5.4). Again, considering that there are 535 members of Congress, $3.45 billion divided by 535 suggests that lobbyists spent about $6.5 million on each member of Congress. Keep in mind that these expenditures include efforts to shape public opinion beyond just direct communication with policymakers.

Electioneering

Electioneering, or using the resources at groups’ disposal to aid candidates for political office, is a common means through which interest groups seek to influence the policymaking process. Many groups have considerable resources to devote to this tactic. The effectiveness of electioneering in influencing the policymaking process is based on the simple fact that policymakers who are sympathetic to a group’s interests are far more likely to be influenced than are policymakers who are not sympathetic. Thus, interest groups seek to elect and keep in office policymakers whom they view as sympathetic to the interests of the group’s members.

Interest groups have, to varying degrees, a set of resources that involve electoral advantages or disadvantages for political candidates. For example, some groups—whose members are widely dispersed across congressional districts throughout the country, that can mobilize their members, and whose members have status or wealth—can affect election outcomes (Kingdon 2010).

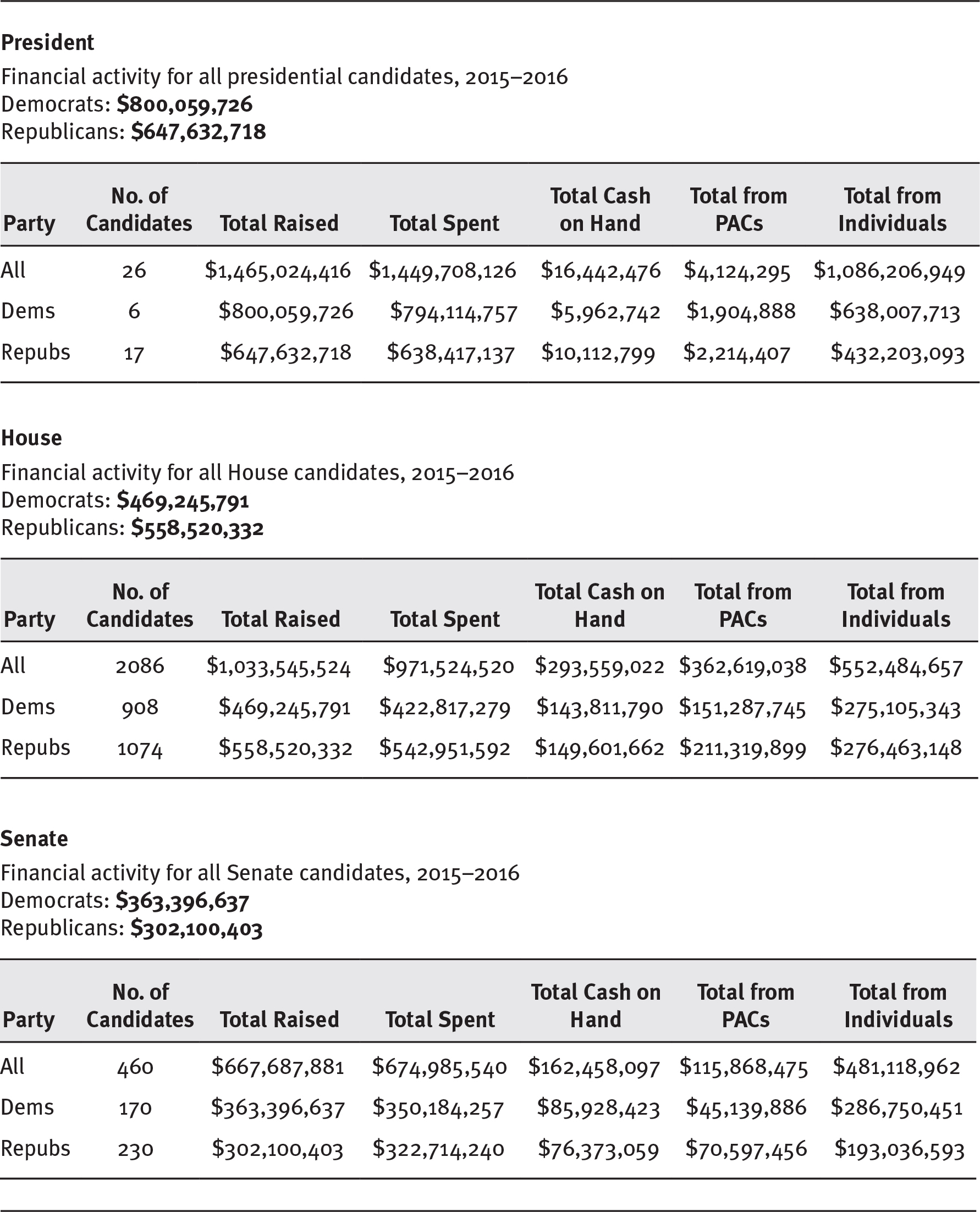

One of the most visible aspects of electioneering is the channeling of money into campaign finances. Exhibit 5.5 shows the extent of this activity in the 2016 elections. Health-related interest groups participate heavily in this form of electioneering. Appendix 2.1 describes the types of groups permitted to be involved in financing political campaigns.

EXHIBIT 5.5 Money Raised in the 2016 Election Cycle

Long Description

The tables list the party, number of candidates, total raised, total spent, total cash on hand, total from PACs, and total from individuals.

President, Financial activity for all presidential candidates, 2015 to 2016: Democrats, 800,059,726 dollars and Republicans, 647,632,718 dollars.

- All: 26, 1,465,024,416 dollars, 1,449,708,126 dollars, 16,442,476 dollars, 4,124,295 dollars, and 1,086,206,949 dollars.

- Democrats: 6, 800,059,726 dollars, 794,114,757 dollars, 5,962,742 dollars, 1,904,888 dollars, and 638,007,713 dollars.

- Republics: 17, 647,632,718 dollars, 638,417,137 dollars, 10,112,799 dollars, 2,214,407 dollars, and 432,203,093 dollars.

House, Financial activity for all House candidates, 2015 to 2016: Democrats, 469,245,791 dollars and Republicans, 558,520,332 dollars.

- All: 2086, 1,033,545,524 dollars, 971,524,520 dollars, 293,559,022 dollars, 362,619 dollars, and 552,484,657 dollars.

- Democrats: 908, 469,245,791 dollars, 422,817,279 dollars, 143,811,790 dollars, 151,287,745 dollars, and 275,105,343 dollars.

- Republics: 1074, 558,520,332 dollars, 542,951,592 dollars, 149,601,662 dollars, 211,319,899 dollars, and 276,463,148 dollars.

Senate, Financial activity for all Senate candidates, 2015 to 2016: Democrats: 363,396,637 dollars and Republicans: 302,100,403 dollars.

- All: 460, 667,687,881 dollars, 674,985,540 dollars, 162,458,097 dollars, 115,868,475 dollars, and 481,118,962 dollars.

- Democrats: 170, 363,396,637 dollars, 350,184,257 dollars, 85,928,423 dollars, 45,139,886 dollars, and 286,750,451 dollars.

- Republics: 230, 302,100,403 dollars, 322,714,240 dollars, 76,373,059 dollars, 70,597,456 dollars, and 193,036,593 dollars.

Source: Center for Responsive Politics (2019a). Reprinted with permission.

In 1975, Congress created the Federal Election Commission (FEC; www.fec.gov) to administer and enforce the Federal Election Campaign Act—the law that governs the financing of federal elections. The duties of the FEC, which is an independent regulatory agency, are to disclose campaign finance information; enforce the provisions of the law, such as the limits and prohibitions on contributions; and oversee the public funding of presidential elections.

The Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan, not-for-profit research group based in Washington, DC, is a rich source of information on the use of money in politics and its effect on elections and public policymaking. The center’s website (www.opensecrets.org) provides extensive, detailed information on the flow of money in the political process.

Although participation in campaign financing is an important source of influence for interest groups, the most influential groups are those who exert their influence through lobbying and electioneering activities. The hospital field is a notable example. The American Hospital Association is a leading campaign contributor through its political action committee. Furthermore, it has many additional resources at its disposal. As Kingdon (2010) points out, every congressional district has hospitals whose trustees are community leaders and whose managers and physicians are typically articulate and respected in their community. These spokespersons can be mobilized to support sympathetic candidates or to contact their representatives directly regarding any policy decision.

As Ornstein and Elder (1978, 74) observed decades ago, “The ability of a group to mobilize its membership strength for political action is a highly valuable resource; a small group that is politically active and cohesive can have more political impact than a large, politically apathetic, and unorganized group.” The ability to mobilize people and other resources at the grassroots level helps explain the capabilities of various groups to influence the policymaking process. The most influential health interest groups, including those representing hospitals, physicians, and nurses, have particularly strong grassroots organizations to call into play in their lobbying and electioneering tactics. While the ability to organize at the grass roots continues to be a source of enormous influence in the policymaking process, the ability of any particular organization to be active in a grassroots campaign changes, and perhaps degrades, over time. The AMA, for example, was extremely vocal in its opposition to Medicare and was effective for many years in forestalling its enactment. In recent times, however, the AMA’s ability to speak with a single voice on behalf of all physicians has diminished owing to the development of subgroups in the medical profession that develop different, perhaps more nuanced positions than can be articulated in the larger group (Girgis 2015).

Litigation

A third tactic interest groups can use to influence the policymaking process is litigation. Interest groups, acting on behalf of their members, seek to influence the policy agenda and the larger policymaking process through litigation in which they challenge existing policies, seek to stimulate new policies, or try to alter certain aspects of policy implementation. Use of the litigation tactic in state and federal courts is widespread, and interest groups increasingly employ it in their efforts to influence policymaking in the health domain. An excellent example is the policy snapshot at the beginning of part 1, in which the National Federation of Independent Business brought suit in federal court to challenge the constitutionality of the ACA. Other examples are noted in chapter 8.

Although interest groups are more likely to seek to influence legislative and executive branch decisions, they can and do pursue their policy goals in the courts. This tactic is especially attractive when interest groups believe there is a bona fide legal or constitutional question regarding the impact of legislative or executive branch action on their members. In these circumstances, groups may find the judicial branch a more fertile ground for their efforts. When interest groups turn to the courts, they are likely to use one of two strategies: test cases and amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs.

Because the judiciary engages in policymaking primarily by rendering decisions in specific cases, interest groups may attempt to ensure that cases pertaining to their interests are brought before the courts, which is known as using the test-case strategy. A particular interest group can initiate and sponsor a case, or it can participate in a case initiated by another group that is pertinent to its interests. The latter strategy involves filing amicus curiae briefs and is the easiest way for interest groups to become involved in cases. This strategy, which is used in federal and state appellate courts rather than trial courts, permits groups to get their interests before the courts even when they do not control the cases in which they participate by filing the briefs. To file a brief, a private group must obtain permission from the parties to the case or from the court. This requirement does not apply to government interests. In fact, the solicitor general of the United States is especially important in this regard, and in some situations the US Supreme Court invites the solicitor general to present an amicus brief.

Friend-of-the-court briefs are often intended not to strengthen the arguments of one of the parties but to assert to the court the filing group’s preferences as to how a case should be resolved. Amicus curiae briefs are often filed to persuade an appellate court to either grant or deny review of a lower court decision (US Department of State 2004). For example, in one case, a group of commercial insurers and health maintenance organizations in New York City challenged the state of New York’s practice of adding a surcharge to certain hospital bills to raise money to help fund health services for indigent people (Green 1995). The US Supreme Court heard this case. Because the outcome was important to their members, a number of health interest groups filed amicus briefs in an effort to influence the court’s decision. Through such written depositions, groups state their collective position on issues and describe how the decision will affect their members. This practice is widely used by interest groups in health and other domains. It has made the Supreme Court accessible to these groups, who, in expressing their views, have helped determine which cases the court will hear and how it will rule on them (Collins 2008). This practice is also frequently and effectively used by interest groups in lower courts to help shape the health policy agenda.

The use of litigation is not limited to attempts to shape the policy agenda, however. One particularly effective use of this tactic is seeking clarification from the courts on vague pieces of legislation. This practice provides opportunities for interest groups to exert enormous influence on policymaking overall by influencing the rules, regulations, and administrative practices that guide the implementation of public statutes or laws. We will say more about the role of interest groups in chapter 9 in the discussion about rulemaking as part of the overall public policymaking process. For now, recall from chapter 1 that the rules and regulations established to implement laws and programs are themselves authoritative decisions that fit the definition of public policies.

Shaping Public Opinion

Because policymakers are influenced by the electorate’s opinions, many interest groups seek to influence the policymaking process by shaping public opinion (Blendon et al. 2010; Schlesinger 2014). A good example of this influence is seen in some of the activities of the Coalition to Protect America’s Health Care. On its Facebook page, the coalition describes itself as “an organization of hospitals and national, state, regional and metropolitan hospital associations . . . united to achieve one goal: to protect high quality patient care by preserving the financial viability of America’s hospitals” (Coalition to Protect America’s Health Care 2020). It pursues this goal in part by shaping public opinion through ads supporting hospitals.

This tactic, of course, is not new. It was used extensively in the congressional debate over national health reform in the 1990s. Interest groups spent more than $50 million seeking to shape public opinion on the issues involved. For example, many thought the health insurance industry’s ubiquitous “Harry and Louise” ads were effective during the debate (Hacker 1997). These ads were not the first use of this public opinion tactic by healthcare interest groups, however.

Intense opposition in some quarters to the legislation, especially by the AMA, fueled the congressional debate over the Medicare legislation in the 1960s. The American public had rarely, if ever, been exposed to so feverish a campaign to shape opinions as it experienced in the period leading up to its enactment in 1965.

Among the many activities undertaken in that campaign to influence public opinion (and through it, policymakers), perhaps none is more entertaining in hindsight—and certainly few better represent the campaign’s tone and intensity—than one action taken by the AMA. As part of its campaign to influence public opinion on Medicare, the AMA sent every physician’s spouse a recording and advised them to host friends and neighbors and play the recording for their edification. The idea was to encourage the listeners to write letters to their representatives in Congress in opposition to the legislation. Near the end of the recording, narrated by Ronald Reagan, the following words can be heard (as quoted in Skidmore 1970, 138):

Write those letters now; call your friends and tell them to write them. If you don’t, this program, I promise you, will pass just as surely as the sun will come up tomorrow. And behind it will come other federal programs that will invade every area of freedom as we have known it in this country. Until one day . . . [we] will awake to find that we have socialism. And if you don’t do this, and I don’t do it, one of these days you and I are going to spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children what it was like in America when men were free.

Attempts to shape public opinion about government’s role in health continue today. While it is difficult to discern precisely expenditures designed to affect public opinion, observers can say with certainty that the healthcare sector continues to spend enormous sums of money to influence public policy. For the year 2019, the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry, for example, spent nearly $131 million to employ 809 lobbyists on behalf of 145 clients. Likewise, the hospital and nursing home subsectors spent more than $78 million on behalf of 350 clients using 775 lobbyists (Center for Responsive Politics 2019c).

Although the effect of the appeals to public opinion made by interest groups on policymaking is debatable, the extent and persistence of the practice suggests that interest groups believe that it does make a difference. One factor clearly mitigates the usefulness of this tactic and makes difficult its use by interest groups: the heterogeneity of the American population’s perceptions of problems and preferred solutions to them. For example, in the congressional debate over major health reform in the 1990s, the majority viewpoint at the beginning of the debate was that health reform was needed. However, at no time during the debate was a public consensus achieved on the nature of that reform. No feasible alternative for reform ever received majority support in any public opinion poll. During most of the debate, in fact, public opinion was about evenly divided among the possible reform options (Brodie and Blendon 1995). Similarly, public opinion was split during development of the ACA legislation and has continued to be split throughout its implementation (Kaiser Family Foundation 2013). The split was largely partisan in the early debate about reform in 2009, with Democrats (70 percent) supporting reform and Republicans (60 percent) opposing it (Kaiser Family Foundation 2009).

Interest Group Resources

Using lobbying, electioneering, litigation, and efforts to shape public opinion, interest groups seek to influence the policy agenda and the larger public policymaking process to the strategic advantage of their members. The degree of success they achieve depends on the resources at their disposal. In a classic book on the subject, Ornstein and Elder (1978) categorize the resources of interest groups as follows:

- Physical resources, especially money and the number of members

- Organizational resources, such as the quality of a group’s leadership, the degree of unity or cohesion among its members, and the group’s ability to mobilize its membership for political purposes

- Political resources, such as expertise in the intricacies of the public policymaking process and a reputation for influencing the process ethically and effectively

- Motivational resources, such as the strength of ideological conviction among the membership

- Intangible resources, such as the overall status or prestige of a group

An especially important physical resource is the size of a group’s membership. Large groups, especially when a group can convince policymakers that it speaks with one united voice representing the preferences of its members, can influence all phases of the policymaking process from agenda setting through modification (Kingdon 2010). Larger groups can obviously have more financial resources, but perhaps even more important, size might provide an advantage simply because the group’s membership is spread through every legislative district. However, the costs of organizing a large group can be high, especially if their interests are not concordant and focused.

The mix of physical, organizational, political, motivational, and intangible resources available to an interest group, and how effectively the group uses them, helps determine the group’s influence on the policy agenda and other aspects of the policymaking process. A particular group’s performance is also affected by its access to resources compared with groups that may be pursuing competing or conflicting policy outcomes (Edwards, Wattenberg, and Lineberry 2012; Feldstein 2019; Kingdon 2010). The policy marketplace, as we discussed in chapter 2, is a place where many people and groups promote their policy preferences.

The Influential Role of the President (or Governor or Mayor)

Chief executives—presidents, governors, or mayors—also influence the policy agenda, including the agenda for policy in the health domain. Popular chief executives can influence the policy agenda easily (Aberbach and Peterson 2006). Kingdon (2010) attributes the influence of presidents (his point also applies to other chief executives) to certain institutional resources inherent in the executive office. Morone (2014) notes that presidents can energize healthcare policy by setting the agenda and proposing solutions to problems. He also observes that bold federal health policies invariably require presidential leadership.

Political advantages available to chief executives include the ability to present a unified administration position on issues—which contrasts with the legislative branch, where opinions and views tend to be heterogeneous—and the ability to command public attention. Properly managed, the latter ability can stimulate substantial public pressure on legislators. Chief executives can even rival powerful interest groups in their ability to shape public opinion around the public policy agenda.

Chief executives can emphasize problems and preferred solutions in a number of ways, including press conferences, speeches, and addresses. Emphasizing problems and preferred solutions may be an especially potent tactic in such highly visible contexts as a president’s state of the union address or a governor’s state of the state address.

Candidates for the presidency are often specific in their campaigns on various health policy issues, sometimes even to the point of endorsing specific legislative proposals. Examples include the emphasis Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson gave to enactment of the Medicare program in their campaigns and President Bill Clinton’s highly visible commitment to fundamental health reform as a central theme of his 1992 campaign. President George W. Bush made enactment of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 a priority as he entered the campaign for his second term in 2004. In his 2008 campaign, and again in his 2012 reelection campaign, President Obama made health reform one of the highest priorities for his administration.

Another issue-raising mechanism some chief executives favor is the appointment of special commissions or task forces. President Clinton used this tactic in the 1993 appointment of the President’s Task Force on Health Care Reform (Johnson and Broder 1996), as did President Obama in the creation of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform in 2010.

Governors can also use commissions and task forces to elevate issues on the policy agenda. For example, Massachusetts made history when that state’s Gay and Lesbian Student Rights Law was signed by Governor William Weld in 1993. He established the nation’s first Governor’s Commission on Gay and Lesbian Youth, which helped lead the state legislature to enact the law. This law prohibits discrimination in public schools on the basis of sexual orientation. Gay students are guaranteed redress if they suffer name-calling, threats of violence, and unfair treatment in school. In another example, Governor Terry McAuliffe of Virginia established the Governor’s Task Force on Mental Health Services and Crisis Response in 2013 and charged it to seek and recommend solutions to improve the state’s mental health crisis services.

Governors (and certainly presidents) play key roles in shaping their parties’ platforms. When others run as members of that party, they implicitly endorse the party platform (at the least). Some candidates are more explicit than others; some may have points of emphasis in the platform that they articulate more than others. A few may overtly contradict a portion of the platform from time to time. On the whole, however, an elected chief executive holds considerable sway over the positions taken by their party, which in turn affects the attitudes of others.

Chief executives occupy a position that permits them to influence each phase of the policymaking process. In addition to their issue-raising role in agenda setting, they are well positioned to focus the legislative branch on the development of legislation and to prod legislators to continue their work on favored issues even when other demands compete for their time and attention. In addition, chief executives are central to the implementation of policies by virtue of their position atop the executive (or implementing) branch of government, as we discuss in chapter 7, and they play a crucial role in modifying previously established policies, as we discuss in chapter 9.

The Nature of the Health Policy Agenda