Policy snapshot

ENGAGING THE FUTURE

This policy snapshot is unlike the others in parts 1, 2, and 3. Those snapshots related a story about some aspect of policy and the policymaking process. This snapshot invites you to create your own story by engaging the future—to set the path from what is to what will be.

Policy, as we have seen, is continually changing. It usually moves in small increments; once in a generation, a sea change occurs: Social Security in 1935, Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, and the Affordable Care Act in 2010. To be sure, other pieces of major legislation have been enacted between those major events. Examples include the initiation of Part D for Medicare and the 21st Century Cures Act, but none of these initiatives move the policy needle to the same degree that the three major policy transformations mentioned here. Likewise, policy ebbs and flows. For example, during one era, the arc of history is characterized by major policy initiatives in the direction of protecting individuals from the cost of care and shifting the cost to the public sector, despite increasing public expenses. At other times, policymaking will flow in the other direction, seizing on the opportunity to reduce public sector costs and shifting the burden back to the individual, despite the ensuing barrier to care for many.

The root of this confusion is uniquely American among developed countries. As a nation and as a society, we have failed to answer one basic question clearly: Is healthcare an unconditional right of every American? Or is it a commodity available only to the extent that one can afford it? The correct answer to this question is, in the best of American traditions, up to each individual. Thus, at times the policymaking process responds to societal needs by providing greater public support for access to care. And at other times, policymaking responds to that moment’s prevailing public voices and slows public support for access to healthcare. As demonstrated in the policy model used throughout this book, the fluctuation merely represents the changing tide of political, economic, social, and other factors.

Healthcare professionals, however, have chosen to dedicate their time and talents to ensuring high-quality care to as many people as they can. Indeed, as discussed below, they have an ethical obligation to extend this level of care. With that in mind, how do we propose to answer this root question: Is healthcare a commodity or a basic human right? What is your view, and why? Think about that as you read this snapshot.

As you consider that foundational question, let’s review a few facts about the US healthcare system. Chapter 1 explained that estimated healthcare expenditures for the United States in 2018 were $3.647 billion. This amounts to $11,121 per capita and represents 17.8 percent of the US gross domestic product (GDP) (CMS 2019). The average for all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is $3,992 per capita and 8.8 percent of GDP (Tikkanen 2020).

One measure of effectiveness—or ineffectiveness—of the US healthcare system is maternal mortality. For every 100,000 births in the United States, 17.4 women die. By comparison, that same statistic for Italy is 2 (Zephryn and Declercq 2020). Of additional critical importance, this tragedy is visited disproportionately on women of color: In the United States, African American women are 22 percent more likely to die from breast cancer than white women are and 71 percent more likely to die from cervical cancer. And a stunning 243 percent are more likely to die because of pregnancy and delivery than white women are (Hostetter and Klein 2018).

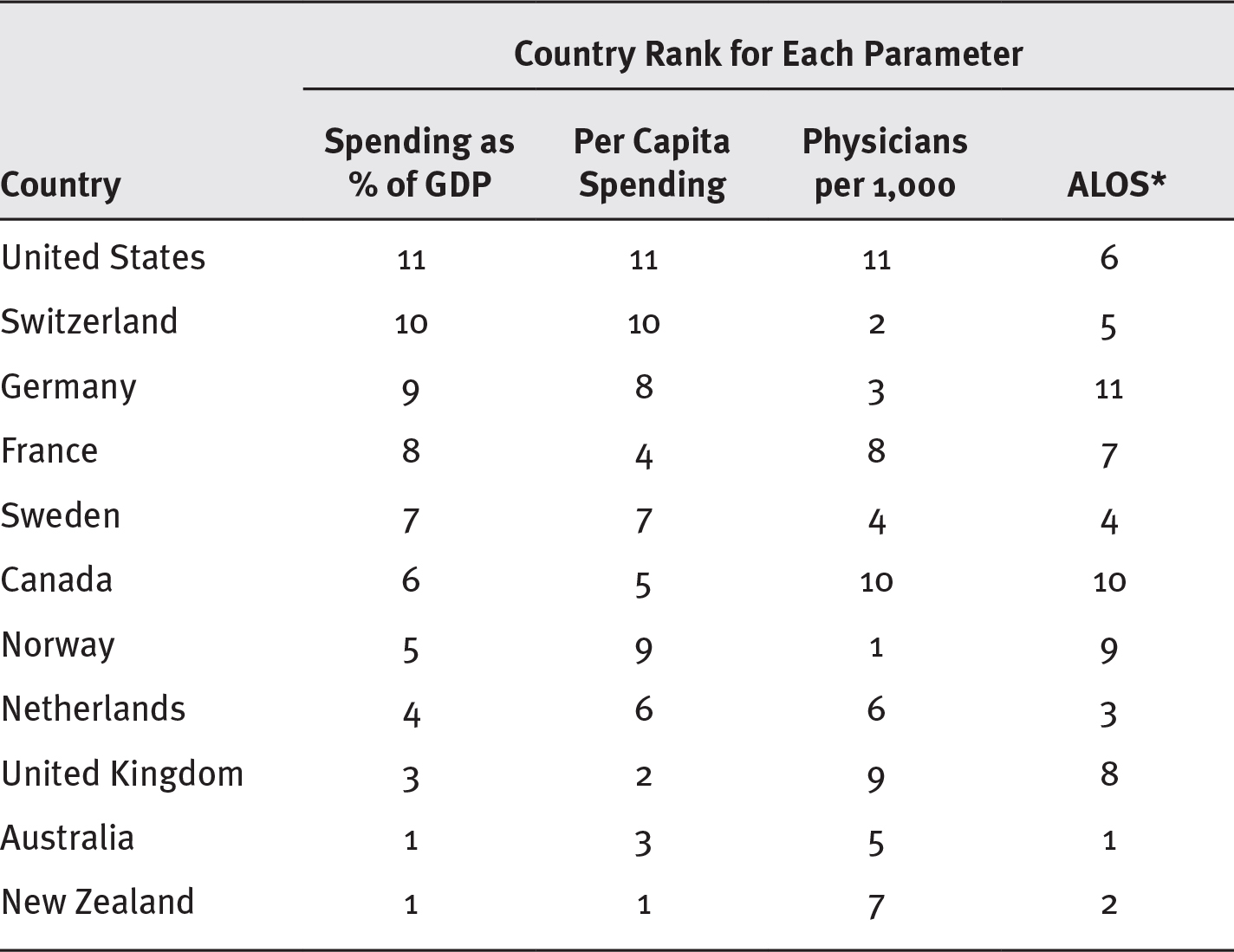

Exhibits A, B, and C present a more complete picture. The exhibits rank the United States and other selected OECD countries on several measures organized by category for presentation here. In each exhibit, the lower the value assigned, the better the performance for that indicator.

EXHIBIT A Rankings by Country for Healthcare Spending, Infrastructure, and Utilization Indicators

Long Description

The parameters show spending as percentage of GDP, per capita spending, physicians per 1,000, and average length of stay respectively for the following countries:

- United States: 11; 11; 11; 6.

- Switzerland: 10; 10; 2; 5.

- Germany: 9; 8; 3; 11.

- France: 8; 4; 8; 7.

- Sweden: 7; 7; 4; 4.

- Canada: 6; 5; 10; 10.

- Norway: 5; 9; 1; 9.

- Netherlands: 4; 6; 6; 3.

- United Kingdom: 3; 2; 9; 8.

- Australia: 1; 3; 5; 1.

- New Zealand: 1; 1; 7; 2.

Source: Adapted from Tikkanen (2020).

*ALOS, average length of stay.

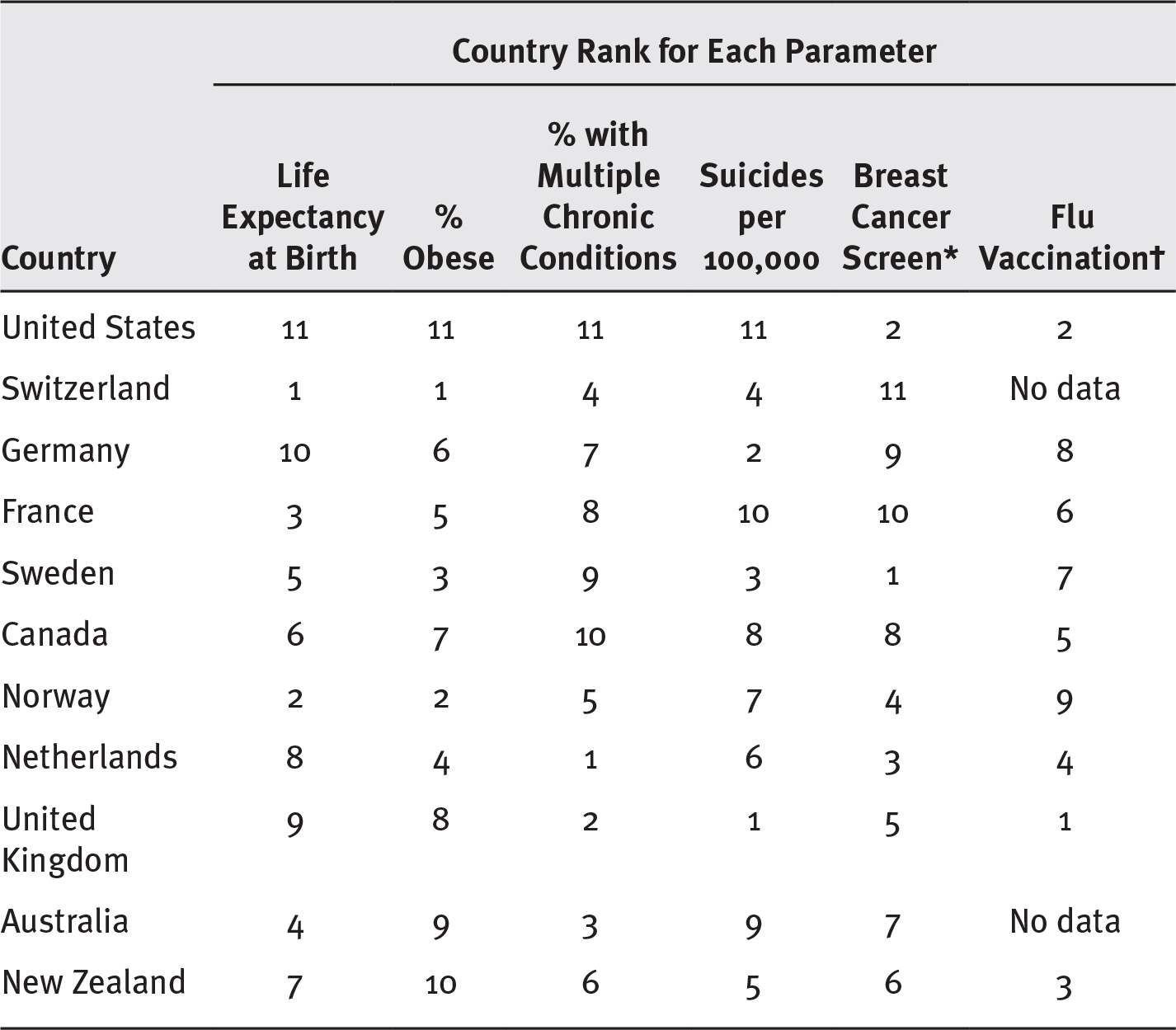

EXHIBIT B Rankings by Country for Selected Public Health Indicators

Long Description

The parameters show life expectancy at birth, percentage obese, percentage with multiple chronic conditions, suicides per 100,000, breast cancer screen, and flu vaccination, respectively for the following countries:

- United States: 11; 11; 11; 11; 2; 2.

- Switzerland: 1; 1; 4; 4; 11; no data.

- Germany: 10; 6; 7; 2; 9; 8.

- France: 3; 5; 8; 10; 10; 6.

- Sweden: 5; 3; 9; 3; 1; 7.

- Canada: 6; 7; 10; 8; 8; 5.

- Norway: 2; 2; 5; 7; 4; 9.

- Netherlands: 8; 4; 1; 6; 3; 4.

- United Kingdom: 9; 8; 2; 1; 5; 1.

- Australia: 4; 9; 3; 9; 7; no data.

- New Zealand: 7; 10; 6; 5; 6; 3.

The breast cancer screen shows the percentage of women aged 50 to 69 screened and flu vaccination shows the percentage of people older than 65 vaccinated.

Source: Adapted from Tikkanen (2020).

*Percentage of women aged 50 to 69 screened.

†Percentage of people older than 65 vaccinated.

Exhibit A compares the nations on various spending and utilization indicators. Note that the United States ranks last in the number of doctors per thousand people and last in both spending categories. In short, the United States spends more than does any other OECD country listed, but certainly not because it has too many physicians! Indeed, the United States has, in relative terms, the fewest. Nor can the high spending be attributed to hospital utilization: The country ranks in the middle for hospital utilization, as represented by average length of stay (ALOS).

For the public health indicators shown in exhibit B, it is shocking to note that the United States ranks last in life expectancy and in rates of obesity, multiple chronic conditions, and suicides but second in breast cancer screenings and flu vaccinations (for those over 65). Populations in other countries are, for whatever reason, less obese and less likely to have multiple chronic conditions (many of which are linked to obesity). Conversely, the US ranks worse relative to other OECD countries.

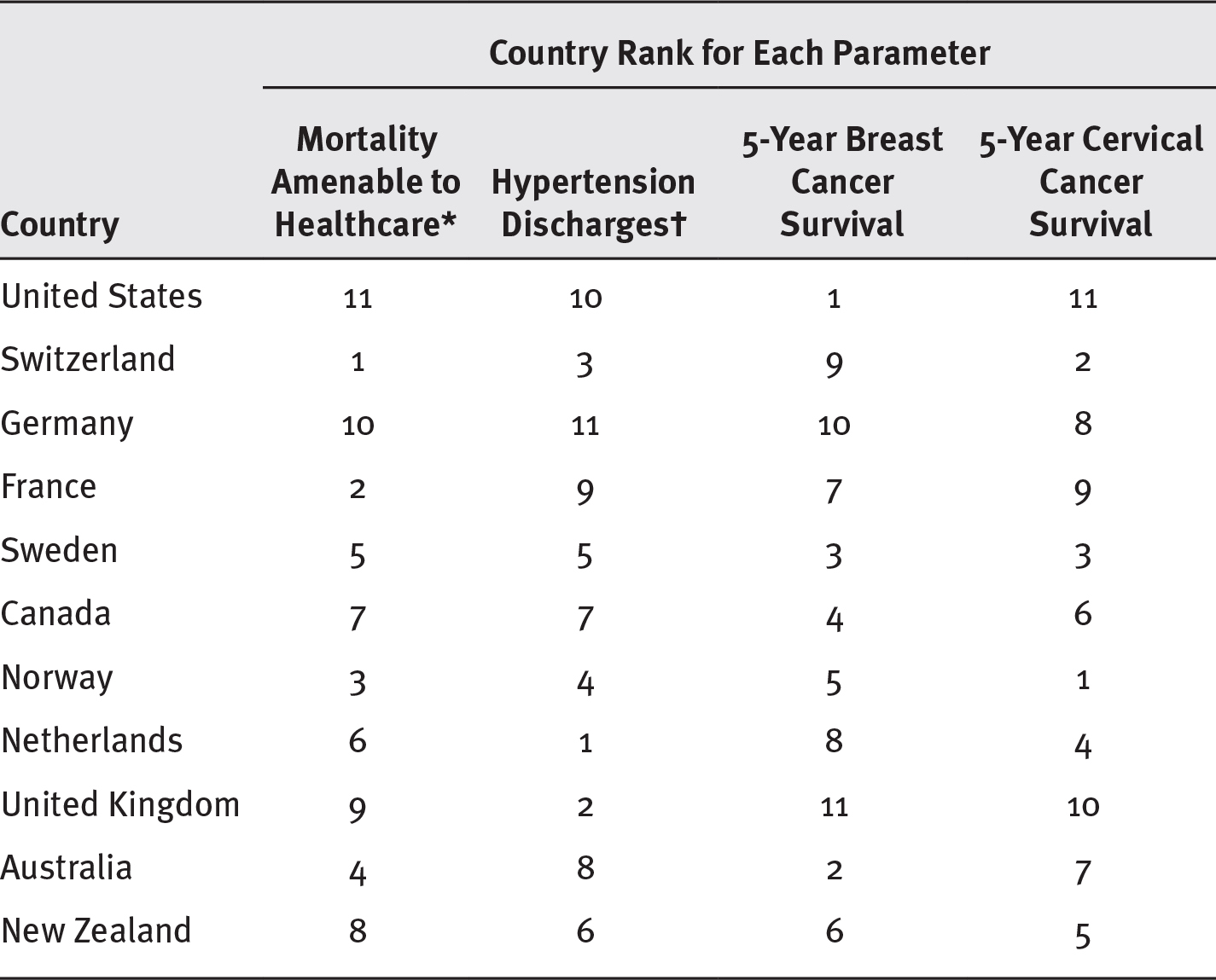

Finally, exhibit C ranks countries on certain indicators of healthcare efficacy. The US top ranking in breast cancer survival suggests that early screening is an effective tool. But unfortunately, the vast disparity in survival rates for African American women, as described earlier, shows that US efficacy for this indicator is not distributed equitably. Furthermore, the hypertension discharge statistic is plausibly related to obesity, demonstrating again the importance of nonmedical determinants of health. The data in exhibit C are, again, rankings of the OCED countries represented. And again, the United States is the last in mortality amenable to healthcare and next to last in patients discharged from the hospital with hypertension.

EXHIBIT C Ranking by Country of Selected Health System Performance Indicators

Long Description

The parameters show mortality amenable to healthcare, hypertension discharges, 5-year breast cancer survival, and 5-year cervical cancer survival, respectively for the following countries:

- United States: 11; 10; 1; 11.

- Switzerland: 1; 3; 9; 2.

- Germany: 10; 11; 10; 8.

- France: 2; 9; 7; 9.

- Sweden: 5; 5; 3; 3.

- Canada: 7; 7; 4; 6.

- Norway: 3; 4; 5; 1.

- Netherlands: 6; 1; 8; 4.

- United Kingdom: 9; 2; 11; 10.

- Australia: 4; 8; 2; 7.

- New Zealand: 8; 6; 6; 5.

The mortality amenable to healthcare shows deaths per 100,000 and hypertension discharges shows the number of discharges with hypertension per 100,000.

Source: Adapted from Tikkanen (2020).

* Deaths per 100,000.

† Number of discharges with hypertension per 100,000.

In general, the data represented in these exhibits suggest that the United States spends more than any other country by any measure and achieves poor to middling outcomes with only occasional blips of excellence. For example, exhibit A shows that the United States spends more per capita than does any other OECD nation in the study and that New Zealand spends the least per capita. This is not to say least is best, or that most is bad, per se. The results need to be commensurate with the spending. Spending must be measured against the effectiveness of the healthcare system.

In light of where the United States stands in relation to other OECD countries, consider this question: What kind of future do you want to create for yourself and your fellow inhabitants of the planet earth? Both sides of the right-versus-commodity question have ideas about how to address the issues represented by data in these exhibits.

Your evaluation of the questions that follow should not be merely a reactive or an instinctive personal opinion. You are invited to present your perspective as an ethical, professional healthcare administrator. Your professional opinion should be informed not only by your expertise but also through the lens of the ethical obligations of a professional healthcare administrator.

To place the right-versus-commodity question in an ethical framework, we may find it useful to center the question on the evolving roles of these five domains:

- Ethics and the common good

- Social insurance (Medicare)

- State governments, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

- Public health

- Technology

The Evolving Role of Ethics and the Common Good

Everyone in healthcare is a caregiver of some kind. Even in management, the obligation is to the patient and the community at large, not merely other stakeholders and other managers. In the following box is an excerpt from the American College of Healthcare Executives (ACHE) Code of Ethics.

ACHE Code of Ethics

V: The Healthcare Executive’s Responsibility to Community and Society

The healthcare executive shall:

- Work to identify and meet the healthcare needs of the community;

- Work to identify and seek opportunities to foster health promotion in the community;

- Work to support access to healthcare services for all people;

- Encourage and participate in public dialogue on healthcare policy issues, and advocate solutions that will improve health status and promote quality healthcare;

- Apply short- and long-term assessments to management decisions affecting both community and society; and

- Provide prospective patients and others with adequate and accurate information, enabling them to make enlightened decisions regarding services.

Source: ACHE (2017).

Compared with its peers around the world, the US healthcare system clearly has something amiss. Despite having the world’s most expensive healthcare system, our country has poor to middling outcomes (and the occasional exceptional outlier, such as breast cancer survival or flu vaccination). But even in the areas where the United States performs well overall, the system remains stained with disparities affecting people of color. Ethically, the question is what duty or obligation does each of us have with regard to working toward a healthier population and a more efficient and more equitable healthcare services delivery system?

As you review the excerpt in the box, note the following references: “meet . . . healthcare needs of the community,” “seek . . . to foster health promotion in the community,” and “access to healthcare services for all people.” What do those phrases mean to you? They suggest an ethical imperative for the administrative healthcare professional to continually consider the common good as a function of their daily professional lives. In fact, it should be the prism through which you view all the following questions raised in this policy snapshot.

The Evolving Role of Social Insurance

Social insurance is a system in which everyone pays into a pool of money to provide services for a defined group of people. These people are referred to as beneficiaries and are, by operation of law and the social insurance concept, entitled to the benefits available from the pool of funds. In the United States, this social insurance system is Medicare Part A, as all employers and employees pay a Medicare tax that is tied to payroll for the benefit of everyone 65 and older and people in a few other specific categories. The future of Medicare Part A, however, is in jeopardy. First, at both current and anticipated levels of spending, which exceed revenue and projected revenue, the Medicare Trust Fund will be out of money by 2026. In 2020, Medicare provided coverage for some 60 million Americans; at $731 billion in 2018, Medicare’s cost represented 15 percent of the federal budget. Second, costs are expected to continue to increase because of the aging of the population, longer life expectancy, the increased utilization of services, the intensity of the services required by patients, and general escalating costs in healthcare.1 The picture is not pretty: more people to serve and more services to provide (especially for chronic conditions), stacked against a finite set of resources (Cubanski, Neuman, and Freed 2019).

Several policy options could address the Medicare funding problem. First, the government could raise taxes incrementally to mitigate the continuing shortfall in the difference between Medicare tax revenue and its trust fund expenditures. Second, the Medicare program could impose a means test to limit the number of people covered—requiring that those in higher income brackets pay an additional sum for coverage. Third, the system could limit the scope of services. Fourth, Congress could impose greater limits on the amounts paid to providers. Fifth, Medicare could be used as leverage to bring more uninsured people into coverage through any of a variety of expansions. For example, some segments of the population could be permitted to buy coverage from Medicare, or the government could implement a single-payer system extending Medicare-like coverage to every American. These ideas reflect some of the proposals from several presidential candidates in the 2020 presidential campaign (Blumeberg et al. 2019). Perhaps the nation could try several of the proposed alternatives simultaneously.

Each of these ideas has salient good and bad points, and whether you consider an idea good or bad depends on your perspective. Limiting payments to providers has a good ring to it to those who see providers as profiteers. Providers, of course, would see it differently. And it may not be sanguine to anyone if providers start dropping out of the program for lack of appropriate reimbursement. Policy options need to be crafted carefully to create equity among the stakeholders—that is, to minimize disparities and cost while maximizing quality of care and access to it.

In the future you wish to create, what option or set of options would you choose? How would you apply the lessons in the ensuing chapters to pursue your objective? What observations would influence your answer? How many issues reflected in the preceding exhibits would be affected by your choices on Medicare? How would you use Medicare to address some of the shortcomings reflected in the exhibits?

The Evolving Role of State Governments: Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, and Beyond

As described in chapter 3, individual states are playing an increasingly important role in health policy. The ACA delegated an enormous responsibility to state governments in the form of Medicaid expansion and the operation of health insurance exchanges. These policy decisions and the waivers associated with each decision enhanced the states’ role in health policy significantly. Likewise, litigation filed by, and on behalf of, state governments by attorneys general and governors may further push this boundary.

Medicaid

In its 2020 configuration, Medicaid covers approximately 20 percent of the population. The federal government is delegating more flexibility to the states with regard to Medicaid. In 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced new policy guidance.2 It invited states to especially experiment with the work requirements in Section 1115 waivers (discussed in chapter 3) to address the “expansion” population in Medicaid created by the ACA (CMS 2018). In response, in early 2020, seven states had been approved for a waiver to impose work requirements, and ten had pending applications (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). In an effort to provide still more flexibility to the states, in January 2020, CMS issued additional policy guidance inviting states to submit 1115 waiver applications to convert their Medicaid programs into a block grant (Lynch 2020).

This invitation represents a significant shift in policy that was not authorized by any explicit legislation. The promulgation of this policy guidance is solely an implementation decision. Medicaid has historically been an open-ended entitlement that funds the cost of care for defined eligible beneficiaries, regardless of cost. The block-grant proposal gives the states more flexibility, to be sure, but in exchange, the nature of the funding would change from open-ended to a finite sum of money. Furthermore, should the state (under the terms of the policy guidance) save money by operating the program with less funding than was made available in the block grant, the state would share in the savings with the federal government (Kaiser Family Foundation 2020). Consumer groups and advocates for people with low incomes are leery. A legal challenge almost certainly awaits this initiative.

Will the states reduce access to care when costs exceed levels supported by block grants? Would this reduction be consistent with the underlying policy of Medicaid’s purpose? Should the federal government undertake other efforts to encourage states to expand Medicaid within the existing framework of the ACA? What role does social justice or addressing healthcare disparities occupy in your thinking? How could states ameliorate some of the US shortcomings reflected in the exhibits?

The Affordable Care Act

States also have substantial responsibility in managing health insurance exchanges and defining some of the benefits available through them. Along with Medicaid, these exchanges could have a dramatic impact on disparities in access to care. Likewise, through the waivers discussed earlier and in chapter 3, health insurance exchanges can meet a variety of goals related to state government costs and social programs.

Partly outside the realm of the federal government, some states have enacted a public-option insurance plan that permits people to buy health insurance coverage directly from the states. New York, Minnesota, and Washington have all enacted some form of public-option health insurance for individuals. Washington’s program, effective in 2021, allows individuals to buy into the state’s Medicaid program (Commonwealth Fund 2020). Considering these efforts, how might a public-option insurance plan improve the healthcare system?

Legal Challenges

In addition to managing Medicaid and operating health insurance exchanges under the ACA, the states’ roles will take on other, unknown dimensions as well. State attorneys general of both parties are showing an increasing appetite for challenging federal initiatives, particularly those emerging from the White House (Rayasam 2020). By mid-2020, Democratic attorneys general had filed 91 lawsuits against the Trump administration. Republican attorneys general filed 52 lawsuits against the Obama administration (Rayasam 2020). Note that at least two of those cases were ACA related: National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius, in which the lead plaintiff was initially the state of Florida, and Texas v. United States. Both these cases challenged the constitutionality of the ACA.

What role should the states play in reforming healthcare services delivery? Should they expand Medicaid? Offer a public option for individuals to purchase? Impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients? Operate a health insurance exchange, or leave it to the federal government? Could any of these policy options affect the indicators in exhibits C-2 or C-3? If states like Colorado or Nevada, or others, undertake a public option and other initiatives to improve health services delivery, is it fair to Americans in other states?

The Evolving Role of Public Health

The penumbra of public health can be incredibly broad. As described earlier in the book, its fundamental activities are assurance, assessment, and policy development. These activities can be applied to restaurant inspection, basic health screenings, and, of course, the spread of infectious disease—the last issue being something that should especially concern all of us. The fundamental activities can be applied to health disparities, to ensure that all who need healthcare do, in fact, receive it. And they can be applied even more broadly to climate change.

As hospitals and health systems move toward population-based health services, they become increasingly closer to the realm of public health. Healthcare organizations engaged in expanding the housing supply or increasing access to healthy food is an emerging concept. Should these ideas continue? Should we have clinical organizations addressing social services related to public health? As a professional healthcare administrator, how much should you do to apply the principles of public health to the healthcare system in addressing broader issues such as disparities in care or climate change? What impact, particularly on the indicators in exhibit B, would such initiatives have?

What would it take to improve life expectancy? What health determinants would affect that measure? It is no secret that obesity, suicides, and chronic conditions are related to this issue. What others? The crisis with substance use disorder? Gun violence? How could the overall health system be changed to improve these indicators?

The Evolving Role of Technology

Technology means many things. One may instantly conjure up images of computers, handheld devices, and servers, for example. Other people may picture MRIs or ultrasound devices. Certainly, these impressions are correct. The management and dispersal of health-related data is an enormous public policy issue, as discussed in chapter 7. The widespread access of individual health information facilitates clinical integration and improved delivery of care for an increasingly mobile society. The converse side of the issue, protecting patient privacy, is equally important, however.

Telehealth is another emerging technology that affects the delivery of care. Telehealth includes such practices as monitoring patients’ data remotely while they are at home and specialty consults for patients by phone or video. Further, this technology has been used in intensive care units (ICUs). Telemetry transmits the data, which are accompanied by a real-time video, so that the specialists can remotely monitor the ICU patients. The staff in the ICU can then respond to the patients’ needs according to the recommendations or instructions of the specialists using the monitors.

But technology means more than the hardware and software associated with data management and diagnostic and therapeutic devices. It also extends to pharmaceutical applications and human genetics research and treatment.

Gene therapy is emerging as a form of treatment for many human diseases and conditions. Bioengineered blood vessels are a reality; can other body parts be far behind? Pharmaceutical manufacturers have created a new form of drug called biologics, medical products derived or partly derived from biological sources. How will these advances be applied? Can programs such as Medicaid and Medicare work to extend these forms of technology to all who need them? How can these developments be used to improve the nation’s rankings in either exhibit B or exhibit C?

The transmission of data is critical to a health system’s ability to integrate care for its patients. What ramifications does the electronic sharing of data from system to system across the nation have? How does the transmission of personal health information or keeping it in a data warehouse affect the indicators in any of the exhibits presented here? What advances are most likely to have a salubrious impact on those indicators? Can modern therapies be available to patients through Medicare and Medicaid?

Conclusion

Healthcare managers have both an ethical obligation to improve the lives of individuals involved in their organization and a larger ethical obligation to the community and society. The ACHE Code of Ethics, part of which was presented in a sidebar in this snapshot, exemplifies the standards to which all healthcare leaders should aspire.

Policy modification and health professionals’ competencies to bring about change are the topics of part 4. Now that you see the condensed data on the equity and efficacy of the healthcare system, what will you do to address the profession’s ethical obligations? The overriding question is, How will you use the tools of modifying policy (chapter 9) and policy competence (chapter 10) to create the future?

The comparisons made at the beginning of this policy snapshot rely on national data that few of us will ever be able to influence directly as policymakers. The sources of those indicators remain beyond the reach of all but a handful of elites (see chapter 2) in the policymaking system. Healthcare has been something of a local endeavor historically. Note how often the term community arises in the ACHE ethics excerpt and in a wide variety of other healthcare-related settings and conversations. The ubiquity of this term suggests that each of us can have an impact at the local and, perhaps, state level. In that spirit, look at the health indicators and outcomes for your state and county (County Health Rankings 2020). As you read part 4, ask yourself where you can find your opportunity to make changes using the tools and competencies discussed there.

Notes

- Life expectancy in the United States had continually increased until 2014, when it plateaued and then declined in 2017 because of “deaths of despair,” deaths from drug (opioid) overdose, alcohol abuse, and suicide (Woolf and Shoomaker 2019).

- Policy guidance, unlike rulemaking, offers no public comment period when it is issued. There are, however, 30-day comment periods at both the federal and the state levels for any 1115 waiver application (CHLPI 2020).

References

American College of Healthcare Executives (ACHE). 2017. “Code of Ethics.” Amended November 13. www.ache.org/-/media/ache/ethics/code_of_ethics_web.pdf.

Blumeberg, L. J., J. Holahan, M. Beuttigens, A. Gangopadhyaya, B. Garrett, A. Shartzer, M. Simpson, R. Wang, M. M. Farveault, and D. Arnos. 2019. “Comparing Health Insurance Reform Options: From Building on the ACA to Single Payer.” Commonwealth Fund. Published October 16. https://doi.org/10.26099/b4g6-9c54.

Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI). 2020. “Health Care in Motion: Administration Releases a ‘Block’-Headed Invitation to Dismantle Medicaid.” Published January 31. www.chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/HCIM_1_31_20.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2019. “National Health Expenditure Data: Projected.” Accessed February 5, 2020. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationaHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.xhtml.

———. 2018. “CMS Announces New Policy Guidance for States to Test Community Engagement for Able-Bodied Adults.” Published January 11. www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-new-policy-guidance-states-test-community-engagement-able-bodied-adults.

Commonwealth Fund. 2020. “States with Public Coverage Options for Individual Market Consumers.” Published January 15. www.commonwealthfund.org/chart/2020/states-public-coverage-options-individual-market-consumers.

County Health Rankings. 2020. “State Reports.” University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, School of Medicine and Public Health. Accessed June 8. www.countyhealthrankings.org.

Cubanski, J., T. Neuman, and M. Freed. 2019. “The Facts on Medicare Spending and Financing.” Kaiser Family Foundation. Published August 2. www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/the-facts-on-medicare-spending-and-financing.

Hostetter, M., and S. Klein. 2018. “Reducing Racial Disparities in Health Care by Confronting Racism.” Commonwealth Fund. Published September 27. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. “Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State.” Published May 29. www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state.

Lynch, C. 2020. “Letter to State Medicaid Director.” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services. Published January 30. www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/Federal-Policy-Guidance/Downloads/smd20001.pdf.

Rayasam, R. 2020. “Five AGs Who May Drown a Democratic White House.” Politico. Published January 25. www.politico.com/news/2020/01/25/5-republican-attorneys-general-who-may-drown-a-democratic-white-house-099374.

Tikkanen, R. 2020. “Multinational Comparisons of Health Systems Data, 2019.” Commonwealth Fund. Published January 30. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/other-publication/2020/jan/multinational-comparisons-health-systems-data-2019.

Woolf, S., and H. Schoomaker. 2019. “Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959–2017.” Journal of the American Medical Association 322 (20): 1996–2016.

Zephryn, L., and E. Declercq. 2020. “To the Point: Measuring Maternal Mortality.” Commonwealth Fund. Published February 6. www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/measuring-maternal-mortality.