Radical innovation in stock management are components to upgrade existing systems and jumps in technology. Innovative components can be integrated into existing stocks through technologic or fashion upgrades; jumps in technology will lead to a gradual replacement of stocks and away grading of objects for reuse elsewhere, or dismantling to recover components or the recovery of molecules. The development of new molecules and technologies to recover molecules at a purity-as-new will need upfront investments in science and R&D.

9.1 The drivers of innovation in the circular industrial economy

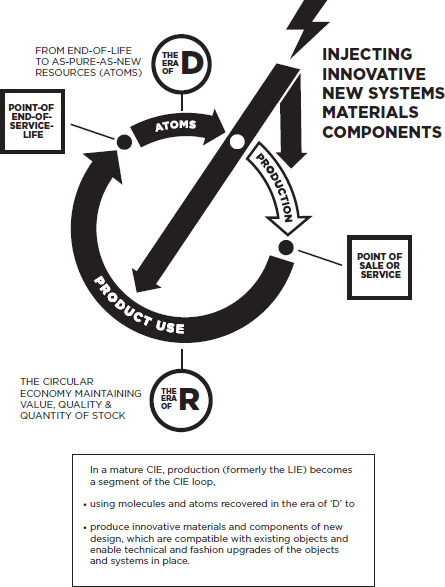

In a mature circular industrial economy (Figure 9.1), production becomes a segment of the loop of the circular industrial economy, with the task of producing innovative components and objects to upgrade and renew the stocks of objects. In construction and the electro-mechanical world, technology upgrades often involve singular components, which can be replaced by new-tech components fulfilling the same function.

Figure 9.1 Radical innovation in materials, components, systems

Radical technical innovation does often not depend upon a single scientific discipline or industrial sector. Recognising the potential of sleeping innovation will help speeding up their application in the market; this selection process is open to academia, industry, government authorities and other innovators.

If manufacturers refuse visible jumps in technology, preferring incremental innovation in order to prevent stranded capital, sudden change is programmed. Tesla versus the world car industry is a recent example of this. For the circular industrial economy, jumps in technology impact first the value and utility of the stock of objects, and are thus a hazard for actors of the era of ‘R’. Second, they lead to an avalanche of used material in the era of ‘D’. But these stock changes are foreseeable, slower and less abrupt than those hitting manufacturer flows.

A key driver of progress in the circular industrial economy has always been economics, the cost of service-life extension versus the price of similar new objects. Innovation that reduces the costs of repairs and spare parts (3D-Print) will boost the era of ‘R’. High volatility in commodity prices and the cost of labour can be drivers or obstacles for the eras of ‘R’ and ‘D’; policymakers with a vision of the future can directly influence both factors through, for example, taxation.

Science, by contrast, does not directly generate change. Global resource security became a topic after the 1973 research report on the ‘Limits to growth’ by the Club of Rome, which reached a worldwide audience but did not hit commodity prices. The concept of a circular industrial economy, which emerged a few years later (Stahel and Reday-Mulvey 1976), found no audience for some time despite the fact that it offered a solution to this perceived threat.

Innovation as a change agent is not limited to technology. Economic and financial research could also drive change, but has a high resistance to study radical changes, such as the circular industrial economy, which will question present academic wisdom. Remanufacturers know that the Return on Investment (ROI) in remanufacturing combustion engines is five times the ROI in manufacturing similar objects, but academia is hardly interested. The potential impact on the economic wellbeing of applying this knowledge to other sectors is un-researched.

Systemic innovation by industry could be a major change agent, but is slow. In 1992, reducing the resource consumption of industrialised countries by 90 per cent – a factor of ten – and analysing its implications for economy and society was proposed and analysed by the members of the Factor Ten Club. Publications on this research were successful but considered academic (Weizsäcker et al. 1995; Hawken et al. 1999).1 In 2017, 25 years after its formulation, the Factor Ten concept has been adopted by the World Business Council of Sustainable Development (WBCS 2018).

9.2 Innovation in the era of ‘R’

In the circular economy of necessity, efforts to maintain the utility of objects dominate; innovation often comes from craftsmen looking to produce new products from ‘waste’, transforming used objects into new ones, such as steel drums into kitchen ware (Papanek 1971).

The circular industrial economy in societies of abundance aims to maintain value and utility of objects, by developing cheaper ‘R’ technologies or new components allowing a technologic or fashion upgrade of objects.

If users had a voice and would be heard, they could become major change agent in the shift to a circular industrial economy. A 2014 survey found that 77 per cent of the citizens in the European Union would rather fix their products than buy new ones, and identified high costs and low availability of repair services as predominant barriers. Petitions in Germany, Italy and the UK asking for easily repairable and longer-lasting products were approaching 200,000 signatures in 2018.

Fleet managers in the Performance Economy have traditionally been among the key technical innovators, for economic reasons. Developing innovative low-maintenance, spare-less repair and remanufacture methods is the ultimate engineering challenge to minimise the operation and maintenance costs of a stock of objects, or to maximise profits in selling goods as a service. In the 1970s, the US Air Force developed a diffusion bonding technology to repair jet engine blades without the need for spare parts, and methods of cannibalising ‘waste’ aircraft to recover components as cheap spares.

When it started selling ‘power by the hour’, Rolls-Royce developed systems to monitor the condition and performance of engines during flight. This allowed them to pre-emptively address any maintenance issues with lower-cost ‘on-wing’ repairs which help further maximise revenues by keeping the engine in operational service. These methods prevent waste, maximise resource utilisation and provide other business benefits through aligning Rolls-Royce’s objectives to that of its customers, but the need for more highly qualified people in service activities has to be factored into any overall financial savings of such approaches.

In vintage cars, mechanical distributors needing regular adjustments can be replaced by maintenance-free electronic ones. But exploiting these opportunities is not taught in schools, it needs experienced economic actors knowledgeable both in new technologies and the existing stock of objects, which are rare.

Jumps in technology application can be forced by policymakers through pull innovation, building markets through public procurement. Based on visions of a sustainable future, the economy can be motivated to develop in a desired direction. Witness Norway’s decision to pull economic development towards a zero-carbon economy. As a consequence, a Norwegian shipping company asked industry in 2018 to submit tenders for zero-emission coastal express vessels powered by hydrogen and fuel cells. Boreal and Wärtsilä Ship Design picked up the challenge and agreed to develop hydrogen-powered ferries despite the fact that the technology does not yet exist. The ferry will be the first vessel of its kind worldwide (Ferry shipping news 2018), opening the gate to abandoning marine diesel engines in coastal shipping.

Transforming a mechanical typewriter into a Personal Computer (PC) does not make sense, but upgrading mechanical bicycles into e-bikes, by fitting wheel-integrated electric micro-motors and adding a battery, or transforming an original Jaguar E-type from the 1960s into an electric one, is feasible and doable. The converted electric E-type hit the headlines when Meghan and Prince Harry used it to drive off after their wedding.

Innovation changes markets. Economic actors of the linear industrial economy are moving into the Performance Economy when objects with long-life low-maintenance components, such as electric motors, replace maintenance-intensive combustion engines with gearboxes. As long-life low-maintenance components lead to longer-life objects, manufacturers start to seize the opportunity to sell goods as a service in order to retain market control.

In the original IT world, hardware and software could be upgraded separately: hardware items were routinely replaced by new more powerful and/or energy saving components; and software was periodically upgraded, often online, to make computer systems more resilient. New external hardware like printers and hard disks were mostly compatible with existing equipment like PCs. Owner-users could keep the PC therefore ‘as is’ for a long time as up-to-date stand-alone systems.

Ownership and control remained with the owner of the hardware and a software licence. This is still the case for isolated systems like dash-cams and portable GPS. But most connected systems in objects can no longer be repaired or upgraded by the owner or even repair experts, if the source code is retained by the manufacturer. The Internet of Things changes the linear industrial economy principle that ownership, liability and control for an object are transferred at the point of sale from the seller to the buyer. Non-technology issues such as ownership and the right to repair may move into centre stage of policymaking innovation in the era of ‘R’.

9.3 Innovation in the era of ‘D’

This is the sector of the circular industrial economy with the biggest potential for technical innovation and research. Recovering the stocks of atoms and molecules at their highest utility and value (purity) level for reuse is a necessity once the reuse and service-life-extension options of the era of ‘R’ have been exhausted.

This demands new sorting technologies and processes to separate mixed (household) waste into clean material fractions, to dismantle used objects into clean separate material fractions (into different alloys of the same metal, for example) and finally technologies to recover molecules and atoms as pure as virgin resources.

Research into reusing atoms and molecules also opens up new territories in basic sciences, such as developing reusable manufactured materials (see the example of the Cookson Group, p. 69). Questions like: ‘can CO2 emissions become a resource to produce new chemicals, and will this new carbon chemistry be able to compete with petro-chemistry?’ may find an answer through scientific research. Using Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and Carbon Capture for Utilisation (CCU) to produce hydrogen is another research topic, studied in Norway.

Recovering stocks of atoms and molecules for reuse at their highest value and purity level is the objective. But the recovered molecules will be in competition with those from virgin sources. As commodity prices have a high volatility, but investments into new technology are fixed and have a long pay-back period, the question arises how research in the era of ‘D’ can be financed.

Sorting manufactured materials is a new problem for the economy, non-existent in mining. Innovative economic actors should be in the driver seat of the era of ‘D’, governments can support these activities by creating appropriate framework conditions. The reward will be patentable solutions to recover atoms and molecules. This is a playing field open to international competition, and the winner may take it all. The opportunities include:

- De-bonding molecules, such as to de-polymerise polymers, de-alloy metal alloys, de-laminate carbon and glass fibre laminates, de-vulcanize used tyres to recover rubber and steel, de-coat objects.

Plasto, a Norwegian company producing equipment for fish farming, has started to take back end-of-service-life objects made of High-density Polyethylene (HDPE) in order to re-process the material to produce new equipment. - De-constructing high-rise buildings and major infrastructure. Spain has started to dismantle its Yecla de Yeltes dam, the largest de-construction project of its kind ever in Europe; after its ‘green change’ decision, Germany is faced with the problem of deconstructing its nuclear power stations.

In cases where no technology solutions are found for used materials, pressure will mount beginning-of-pipe, on producers of the linear industrial economy to look for alternative materials, such as self-destroying polymers, or change their business models. The circular industrial economy thus opens up a wealth of opportunities for radical innovation in business models and processes, in the eras of ‘R’ and ‘D’ as well as in basic scientific and technological innovation.

9.4 The role of policymakers in innovation

Since the 1990s, techno-economic research with environmental objectives has flourished in areas like Life-Cycle Analysis (LCA), which has a limited scope of ‘Cradle-to-Grave’ (ISO 14044:2006). Research over several service-lives, such as MIPS – Material Intensity Per unit of Service (Schmidt-Bleek 1994) – and the Factor Ten Club did not catch on at the time, possibly because the importance of the ‘units of service’ concept was difficult to understand for experts, and even more difficult to translate into policy.

Political interests to reduce end-of-pipe waste volumes guided academic research to look into the circular industrial economy, to find uses for wastes from the building or electronic industry in order to reduce overwhelming waste volumes. Research programmes such as Horizon 2020 in the EU have motivated researchers to look into ways to maintain value and utility, such as reusing building components (ongoing EU BAMB project; and research projects by ARUP Partners), rather than recovering building materials, for example as aggregate in concrete.

Policymakers with a holistic vision, such as zero-waste or a low-carbon economy, and the capability of identifying innovations in search of industrial applications, can exercise an important pull function through focused research programmes and procurement specifications. This latter has been the case for a long time for the US administration and most recently for Norway. In nation states where policies and the economy are interlinked, like the People’s Republic of China, this approach may lead to even faster results.

References

Ferry Shipping News (2018) 8 February and 17 May. www.ferryshippingnews.com/, accessed 23 January 2019.

Hawken, Paul, Lovins, Amory and Lovins, Hunter (1999) Natural capitalism. Little Brown and Company, Boston.

ISO 14044:2006 (2006). Environmental management – life cycle assessment – requirements and guidelines. International Standardisation Organisation, Geneva.

Papanek, Victor (1971) Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change,. Bantam Books, New York, NY.

Schmidt-Bleek, Friedrich (1994) Wieviel Umwelt braucht der Mensch? MIPS — Das Mass für ökologisches Wirtschaften. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel.

Stahel, Walter and Reday-Mulvey, Geneviève (1976) The potential for substituting manpower for energy. Report to the Commission of the European Communities, Brussels.

WBCS (2018) Factor 10 news. www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Circular-Economy/Factor-10/News/launching-Factor10, accessed 31 December 2018.

Weizsäcker, Ernst Ulrich von, Lovins, Amory and Lovins, Hunter (1995) Factor four. A report to the Club of Rome. Droemer Knaur, Munich.