“Ogilvy wrote a book. I got the galleys.… Advertising’s already up there with lawyers as the most reviled. This is not going to help.”

ROGER STERLING MAD MEN

David Ogilvy married Rosser Reeves’ wife’s sister in 1939. By several measures the two men were similar: workaholics, strongly opinionated advertising writers, and both, in their demeanor at least, cultivated men. But while for Reeves culture ended at his typewriter keys, Ogilvy carried all his considerable personal style into his and his eponymous agency’s work. From the early-fifties onward, a stream of articulate and elegantly art-directed print campaigns issued from Ogilvy, Benson & Mather (OB&M), all assuming literacy and sophistication on the part of the reader—and usually offering the promise of yet more sophistication through the use of the product they were advertising.

Ogilvy was English, at a time when an English accent was still rare and hugely prized in New York. Ogilvy’s was a particularly well-modulated accent, and with his long, lean figure, foppish hair, and ever present pipe, he was every bit Hollywood’s idea of the perfect English gentleman, a character he exploited fully.

Ken Roman, his biographer, who worked with Ogilvy and knew him closely from 1963 until he died in 1999, says, “He dressed for his parts. He didn’t wear a business suit. Sometimes he dressed as the English country gentleman with his brogues, a tweed jacket, and lapels on his vest. Sometimes he wore a kilt, before anyone had seen one. Sometimes, at big state occasions, he put on this kind of a purple vest that looked vaguely ecclesiastical. But he never wore a normal business suit, never.”

Ogilvy’s route to fame and fortune in New York was as peripatetic as it was exotic. Born in England in 1911, he won a scholarship to study history at Christ Church College, Oxford. He left without completing his degree, having suffered some sort of block, and, as quoted by Bart Cummings in The Benevolent Dictators, “ran away from the cultured, civilized life, and changed class and tried to become a workman. I went to Paris and got a job as a chef in the great kitchen at the Hotel Majestic.” He withstood the “slave wages, fiendish pressure, and perpetual exhaustion” for a year, returned to England, and began selling Aga cookers door to door. His sales prowess brought him to the attention of his elder brother Francis’s employers at the advertising agency Mather & Crowther (M&C).

Ogilvy accepted the offer of a job as an account executive and did well, but felt he was working in his brother’s shadow. To prove his independence he asked for a transfer to M&C’s US office. He went to New York in 1938, and by the end of a year he loved it so much he didn’t think of returning to England. With no firm intention of continuing with a career in advertising, he drifted into his next job, but it turned out to be critical in the formulation of his theories and future practices. He joined George Gallup’s company and entered the new but rapidly expanding world of consumer research.

ADVERTISING RESEARCH had existed since the late nineteenth century in the form of crude testing of different versions of ads by evaluating coupon responses. Mail order shopping was dominant in a dissipated, still largely rural population, so it was easy to measure the success of an ad simply by tracking the volume of orders that followed each insertion. The offer of a free sample at the bottom of an advert for a new beauty soap wasn’t generosity on the part of the manufacturer, nor was it just about getting a trial; it elicited a coupon to be returned to the company. The coupons were coded to identify the specific advert and the publication in which it had appeared, and by analysis of the returned coupons a basic picture could be drawn of which version of the ads, running in which publications, were the most successful.

But the research was rough and ready and reactive; it could only give you a crude view afterwards, which you could then apply to your next insertion. As the development of mass production and branded products fed the growth of advertising, market research slowly grew up alongside it, developing from “How did we do?” to “Why?” to “How can we do it better?”

In an attempt to assuage the advertisers’ anxiety—best expressed by the nineteenth-century Philadelphia store owner John Wannamaker when he said, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half”—agencies racheted up their research presentations, claiming to be able to produce super-efficient advertising based on their “proprietary” research techniques.

BY THE 1930S, research had become the Holy Grail of advertising; clients, often uncertain and uncomfortable when handling and evaluating abstract “creative” ideas, were much happier pouring over the endless charts and graphs churned out by the research people, and were reassured by the rules guiding them through the alien world of advertising creativity. The copywriter’s imagination and individuality was allowed to run only to the point at which it interfered with the “proven” rules of how they should do their ads, and intuition became subordinated to research reports.

An audience measurement system was developed by Claude Hooper, specifically to cater for the explosive interest in radio as an advertising medium, and the phrase “Hooper Ratings” became the scourge of radio producers and agencies across the country. Such was the client confidence in their research that a low Hooper rating on a Monday morning could break a Saturday night radio show.

In 1931 George Gallup, then a professor of journalism at Northwestern, produced a report of his research into readers’ reactions to advertisements in magazines. He found that ads based around sex and vanity were the most popular with women, the second most popular being those based on the quality of the product. Men also ranked those as their top two, only in reverse order. But in the same survey, Gallup found that those approaches were the two least favored by advertisers, who preferred ads leading on efficiency and economy—which were the least favored by all readers.

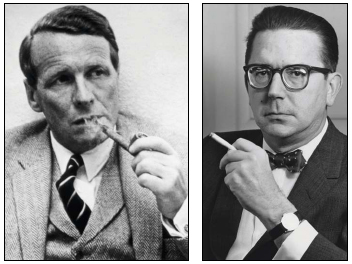

Brothers-in-law but in little else; David Ogilvy (left) and Rosser Reeves (right).

The impact of his findings attracted major attention across the advertising world and he was wooed by several of the larger agencies. He eventually joined Young & Rubicam (Y&R) to head their research department and then in 1935 set up the American Institute of Public Opinion, which later became The Gallup Organization. The main purpose was the objective measurement of what “the people” were thinking, and his first big success was the correct forecasting of the 1936 election, Roosevelt’s victory over Landon. The Literary Digest, the respected pollster of the day, had projected a Landon landslide. High on the success, Gallup’s business expanded—and it was this organization that David Ogilvy joined in 1939.

IN THE THREE YEARS he was with Gallup, Ogilvy conducted more than four hundred surveys, many of them in Hollywood, pre-testing films. Interrogating the US public on how they perceive and receive communications designed to entertain them was clearly ideal grounding for a future career in advertising. The rigor of the research and analysis also influenced the development of what became his highly disciplined and well-documented philosophy of advertising.

By the time Ogilvy returned to New York, now aged thirty-eight, he’d convinced himself he wanted to be a copywriter but felt no one would employ him as he’d never done the job formally. The only other route open to him was to start his own agency. His personal wealth amounted to $6,000 but his brother persuaded his old British agency M&C, together with another London agency, SH Benson, to invest in the venture on condition he employed an American partner—they felt a British man in New York wouldn’t have the business credibility. So in 1948 he set up Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather with Anderson Hewitt, a Chicago advertising executive who contributed $14,000. Hewitt left the company five years later, when it became Ogilvy, Benson & Mather.

Their first piece of business was Wedgwood, the china manufacturer. It’s a typical Ogilvy product, reflecting a genteel refinement. Indeed, his earliest successes were for similar “drawing room” type products. And despite their small size, they could well be described as his biggest triumphs, since they’re still amongst the most famous work his agency ever did and on which the agency was initially built.

Elegant literary copy and captivating photographs selling the historical and cultural benefits of a holiday in Britain for the British Tourist Association was an early noted campaign. Ogilvy said he was happiest working on products that interested him and they tended to be products with a touch of class, more white than blue collar. In fact, often he couldn’t help imbuing the one with the status of the other, as in an ad for Austin cars with the headline attributed to an anonymous diplomat, “I’m sending my son to Groton with the money I’ve saved driving an Austin.” In Ogilvy’s velvet-cushioned world, a cheap car was sold not on the basis of anything as sordid as thrift or value but on the promise of a posh education for the children of the diplomatic classes.

It was entirely consistent that he should describe the account executives he wanted as the backbone of his agency as “gentlemen with brains.”

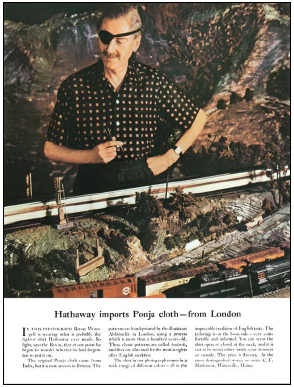

HATHAWAY WAS a medium-priced range of shirts from a small Maine clothing manufacturer with an advertising budget of just $30,000. Typically, Ogilvy decided that the shirts would be modeled on a man of some sort of distinction and they settled on a dispossessed White Russian baron turned part-time PR man, George Wrangell. He definitely had the aristocratic look but was often in poor health and, according to Cliff Field who wrote a lot of the ads over the ten-year period, “a difficult man to photograph. He had a tendency to turn blue outdoors.”

For no clear reason other than he had been intrigued by a picture of Lewis Douglas (the US Ambassador to Britain) wearing a patch over one eye after a fishing accident, on the morning of the shoot Ogilvy bought a handful of eyepatches. At the shoot, he asked that Wrangell be photographed with and without one of the eyepatches, and in the end he chose a version with the patch.

The first ad ran in The New Yorker on September 22, 1951. It was an instant success. The device had exactly the effect Ogilvy wanted, adding intrigue and narrative as a background to the shirts. The campaign developed, showing Wrangell engaged in all sorts of narrative-rich situations; as a painter, an orchestral conductor, a classical musician—always with the eyepatch. Soon it became a popular prop at parties and offices, and other campaigns aped it, even putting it on animals. To maintain an upmarket image the ads ran only in the smart, literary New Yorker, the magazine’s ad manager saying he’d never seen such interest in a campaign.

Never underestimate the power of an eyepatch; one example of the Hathaway campaign.

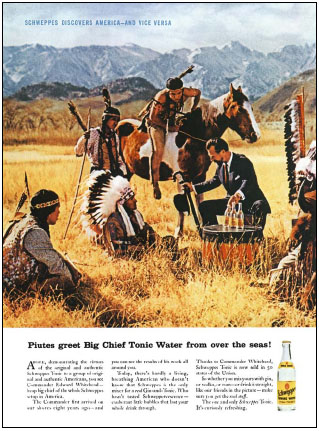

An Ogilvy campaign? Look again—these are actually four completely different campaigns for (clockwise from top left) Viyella, Hathaway, British Tourist Board, and Schweppes.

Between 1950 and 1969, Hathaway sales rose from $2 million per year to $30 million; name recognition went from under 1 percent to 40 percent in ten years; and the number of stores stocking the range rose from 450 to 2,500 between 1950 and 1962.

It worked for the agency too, pulling in enquiries from such establishment clients as P&G. So recognizable and so far down the line of OB&M history did the campaign reach that, when Ogilvy’s book Confessions of an Advertising Man came out in 1965, the publisher’s sales force wore eyepatches while selling it in to stores. As an O&M executive apparently said more than thirty years after the campaign first ran, reflecting on its influence on the agency’s fame and history, “We’ll all have eyepatches on our tombstones.”

THE NEXT MAJOR SUCCESS was the tonic water company Schweppes, a tiny piece of business that spent no more than $15,000 on their advertising. Initially, Ogilvy prepared a workmanlike campaign announcing the availability of the tonic water in the New York area, but the client wanted something more exotic. It’s unclear who first made the suggestion, but the decision was made to use Commander Edward Whitehead, a former World War II Royal Navy officer who was by that time running Schweppes in the United States.

There was no doubt that he looked the part of a British naval officer; a huge bushy beard under a large-whiskered handlebar moustache gave him a sort of camp King George V look, although what that had to do with selling tonic water is obscure. But no matter; for reasons as impenetrable as the success of the Hathaway Shirt Man, the Schweppes Tonic Man became as big a hit. For eyepatch, substitute beard.

Not that it was all plain sailing with Commander Teddy Whitehead. David Herzbrun, a creative director on the business in 1964, recalls in his book Playing with Traffic on Madison Avenue that Whitehead froze in front of the camera. When Harry Hamburg, the photographer, asked for a smile, what he got was “a ghastly rictus of death.” Hamburg muttered to Herzbrun that the only thing Englishmen of Whitehead’s class ever thought was funny was bathroom humor.

“He got Teddy arranged in the right pose, got his camera ready and called out to the Commander, ‘Say shit!’

“Whitehead said it shyly, with a rather endearing schoolboy smile.

“‘Louder,’ Harry commanded.

“‘Shit!’ roared Teddy and laughed until the tears came.

“For the next three days Harry shot as Whitehead shat; and the word never failed to produce the desired results.”

As with Hathaway, the media schedule was limited, again majoring on The New Yorker but also including Sports Illustrated. Although partly driven by the limitation of the budget, it was nevertheless courageous thinking—few advertisers back then had the faith to put all their eggs in one basket. But as Whitehead said, he and Ogilvy agreed that “what the discriminating do today, the undiscriminating will do tomorrow.”

It was, as they say, trucks through the night for Schweppes. The public lapped up the images of Commander Whitehead going about his high-octane life, stepping off jet planes, sporting ice on his beard at some chic ski resort, dining with a beautiful woman at a stylish restaurant. Sales were up from under a million bottles to 32 million per year in five years, a remarkable result since it had barely been heard of in the United States before.

OGILVY WAS, if not exactly a snob, certainly class conscious. As he rather characteristically put it, “There are very few products that do not benefit from being given a first-class ticket through life.” Maybe it was the often experienced reaction of the Englishman of that era in New York, where in the face of the brash, loud, busy new world he retreats into a caricature of his real self and becomes even more English, brittle, and refined. It is not hostility to the surroundings, but perhaps it is to preserve the independence and objectivity of the view that first so captivated him.

He was also capable of the most breathtaking vanity, happy to be quoted by Ken Roman in such conceits as “By twenty-five I was brilliant,” “I lit a candle which is still burning forty years later,” and “I love reading in the press what a great copywriter I am.” Ken also recalls one of the most inventive pieces of Ogilvy’s self-aggrandisement, a feature that appeared on the front of the OB&M in-house magazine. With a picture of himself next to one of Charlemagne to prove the physical likeness, Ogilvy proclaimed he’d finally found proof that “your Chairman” is indeed descended from this greatest of legendary medieval kings.

A genuine client with a genuine beard. Commander Whitehead of Schweppes.

At the recollection Roman smiles and says, “It was not a joke. It was serious. But we all kind of smiled, ‘that’s David being David.’ He was a man of enormous ego, but he had this self-aware humor. He didn’t take himself that seriously. He was an actor. When I started doing the research [for his biography, The King of Madison Avenue] I found over and over, the things he said about his life were almost true, but not quite. He embellished.”

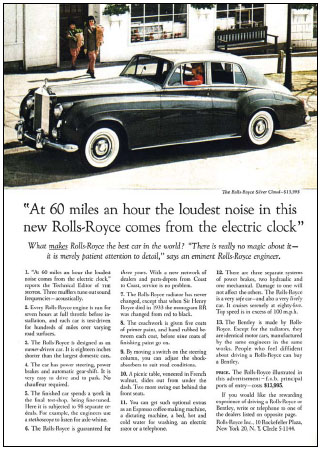

Perhaps the best line he ever wrote, certainly the one for which he was most known, was for an advertisement that created an eighteen-month waiting list of potential customers: “At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock.”

When it was pointed out that it had an unfortunate precedent, some might say beyond coincidence, in a 1933 Batten, Barton, Durstine and Osborn (BBDO) ad “The only sound one can hear in the new Pierce Arrow is the ticking of the electric clock,” his insouciant response was that he didn’t steal it from Pierce Arrow, he stole it from a British motoring magazine article. Ogilvy was a fanatically hard worker. “He had no hobbies,” says Roman. “He’d take two briefcases home every night. In Mad Men you see people leaving the office to go to bars, to go to the theater. David would leave the theater to go back to the office. I think it broke up his second marriage; he said that he was going to travel the world, do all these things but he didn’t. He just worked.”

He smoked, but a pipe only, and liked a drink—“I find if I drink two or three brandies or a good bottle of claret, I’m far better able to write”—but strongly disapproved of drunkenness. He was discreet in any personal antics, deeply attractive to women as he was.

WITH THE 1963 PUBLICATION of Confessions of an Advertising Man, Ogilvy’s fame skyrocketed. It’s an advertising manual with clearly prescribed chapter subjects but written in a jaunty, informal style, anecdote mixed with homily. Like Reeves’ Reality in Advertising, it was intended as little more than a manual for his agency and the original print run was five thousand copies. Well over a million have since been sold.

One of the most famous advertising lines of all time; Ogilvy’s Rolls-Royce advertisement.

It was a brilliant new business tool, containing chapters guaranteed to catch the eye of potential clients: How to be a Good Client, How to Build Great Campaigns, How to Write Potent Copy, How to Make Good Television Commercials, How to Make Good Campaigns for Food Products, Tourist Destinations, and Proprietary Medicines—and, typically mischievous, ending with “Should Advertising be Abolished?”

His efforts had paid off; by now, he was one of the very few advertising names known outside the business and fifteen years after he had opened it, his agency was billing $34 million and ranked twenty-eighth in New York. But although there was a residual reputation for great creative work, it was still hanging on early campaigns like Hathaway and that single Rolls-Royce advert. Increasingly, when it came to turning out campaigns, O&M was being seen as creatively near bankrupt.

Part of the problem was Ogilvy’s advertising ideology, which seemed heavy-handed and inconsistent throughout the fifties and into the sixties. He was fanatical about detailed analysis of the results of advertising research—”This is what I learned from Gallup. I’m obsessed with it”—and about prescribing how an ad should and should not be created. He developed rules for concepts, copy, and layouts with hard facts about effectiveness for any given technique, such as: “Five times as many people read headlines as body copy”; “Research shows that it is dangerous to use negatives in headlines”; “Readership falls off rapidly up to fifty words of copy but drops very little between fifty and five hundred words”; “Always use testimonials.”

Like Reeves, Ogilvy’s proclaimed approach was mechanical—take these ingredients, mix them my way and voila! Guaranteed Advertising Success.

THE REEVES/OGILVY RELATIONSHIP was complex. Says Roman, “They respected each other, they were rivals. David was his student when he came here. Rosser was a big deal, a big copywriter. David adopted him as a mentor. They used to lunch together regularly. Rosser used to say “Do you want to be admired or do you want to be successful?” And he felt there was a dichotomy there. But David brought taste and style… so they parted ways on that. They parted ways on a lot of things. When David divorced Rosser’s wife’s sister, that was a break, on a personal basis. And Rosser really brought up David’s son for many years.”

“The consumer isn’t a moron; she is your wife. You insult her intelligence if you assume that a mere slogan and a few vapid adjectives will persuade her to buy anything. She wants all the information you can give her.”

DAVID OGILVY

There were other personality differences. While Ogilvy was regularly (and rightly) praised by the press for his business ethics and integrity, the Bates agency was in constant trouble with the Federal Trade Commission concerning overclaiming and false and rigged product demonstrations, all driven by Reeves’ desire to ram home demonstrable product differences.

Yet Ogilvy never stopped proclaiming his belief in Reeves’ advertising philosophy, telling him he was “his most fervent disciple.” The whimsy of those early advertisements and the small eccentric clients on which Ogilvy had built his early creative reputation had gone. There was a good reason—he lost money on both Hathaway and Schweppes. The agency was now large and in the major league, winning the vast Shell business in 1960 to go with earlier successes from General Foods and Lever Brothers. These larger clients liked the reassurance of rules and formulae—they found the serendipitous nature of campaigns that work apparently just because the character happens to have a comedy beard, unnerving. “After that,” said Ogilvy of the Shell win, “we changed from being a creative boutique, and got to be a proper agency.”

Throughout the agency the rules were applied, and they hobbled the output of the creative department, particularly the art directors. This bothered Ogilvy little, as he didn’t have much faith in the intuitive nature of his creative staff anyway. Bart Cummings quotes him in The Benevolent Dictators: “Most of the people who do advertising campaigns are rather run-of-the-mill people. If you impose a dogma on them that is research-based, you save them from wasting so much of the clients’ money.” Cliff Field, an English creative director under Ogilvy, said he “threw up his hands at art directors.”

So it’s hardly surprising that the ads started to look repetitive—just a glance at page 39 and you can see how similar they were. Looking back in 1982, Ogilvy himself said, “For years it was difficult for us to persuade an art director to work at Ogilvy & Mather.” Yet the ads had some quiet elegance and style. As Ogilvy put it, “I have come to believe that it pays to make all your layouts project a feeling of good taste, provided that you do it unobtrusively. An ugly layout suggests an ugly product.”

Reeves was ever dismissive of Ogilvy’s more refined approach, once describing the sort of ad Ogilvy would do if he had the Anacin account as “Cecil Beaton or Truman Capote reclining on a bed in a Viyella bathrobe with a caption of ‘You’ll never know you drank that gin if you brush your teeth with Anacin.’”

Cruel—but pointed. And with that parody of Ogilvy’s cultivated approach from the man who brought you hammers pounding the inside of your head, you get a perfect illustration of a battle of ideologies that had been running within agencies since the late nineteenth century, almost from the day that copywriters started working.

It was a pendulum swinging between those who believed in the hard sell, like Reeves, and those who believed in a softer sell, like Ogilvy—between an unadorned utilitarian “reason to buy” appeal and a more emotional “image” approach. But while Ogilvy and Reeves were battling it out, the advertising world was beginning to look another way, noticing the pendulum swinging in a new dimension, to an approach that altogether transcended the old extremes.