The degree of size separation depends on the percentage of agarose, but usually 1–2% (weight/volume of buffer) is appropriate

The degree of size separation depends on the percentage of agarose, but usually 1–2% (weight/volume of buffer) is appropriateStructural proteomics: analysing protein structure and function

Photometry and spectrophotometry

Radioimmunoassay, ELISA, chromatography

Flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS™)

Molecular genetics is the study of the structure and function of genes at a molecular level. This includes both the use of genetics to understand inheritance patterns, and also molecular biology to investigate why certain mutations cause particular traits or diseases.

Genomics is the application of automated oligonucleotide sequencing and computerized data retrieval and analysis to sequence an organism’s entire genetic complement.

• Of obvious interest to the Medical Sciences field is the Human Genome Project which has sequenced the entire human genome

• Readily searchable database of gene sequences, annotated with biological information (and protein function if known), are freely available

Genome-wide association studies (GWA studies or GWAS), also known as a whole genome association studies (WGA studies or WGAS), are the comparison of the genomes of individuals of the same species to identify inter-individual variations in the form of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, see p.208). These differences can then be associated with certain traits, such as diseases, when the genetic variations are statistically more frequent in individuals with the trait/disease. This technique has followed genes to be ‘associated’ with particular diseases, such as diabetes, helping to characterizing the molecular pathway of the diseases.

• One recent approach has been to combine GWAS with metabolomics, the systematic study of small-molecule metabolite levels in samples such as plasma and urine, allowing SNPs to be associated with particular changes in the metabolome (i.e. the entire set of small metabolic within a biological sample). This can suggest potential functions for uncharacterized genes (functional genomics) based on the phenotype of metabolite changes.

Electrophoresis is the separation of complex mixtures of solutes (e.g. peptides, proteins, DNA, RNA) by virtue of their electrical charge and size, with separation, usually enhanced by using a solid matrix with sieving properties.

• Agarose gel electrophoresis is commonly used to separate fragments of DNA or RNA

• The solid matrix used is agarose (a polysaccharide extracted from algae (seaweed))

The degree of size separation depends on the percentage of agarose, but usually 1–2% (weight/volume of buffer) is appropriate

The degree of size separation depends on the percentage of agarose, but usually 1–2% (weight/volume of buffer) is appropriate

• The agarose gel is submersed in a tank of the same buffer, usually a solution of Tris-acetic acid-EDTA (TAE) or Tris-boric acid-EDTA (TBE)

• Samples are loaded into wells pre-formed in the gel, with loading dye to increase the density of the solution so it stays in the wells, and to allow visualization of how far migration has progressed

• An electrical field is applied across the gel, and the samples move towards the positive electrode due to the overall negative charge of the DNA/RNA molecule—the smaller the component, the further it will travel in a given period of time

• The DNA/RNA fragments can be visualized by staining with ethidium bromide, either added to the gel or post running, which binds to DNA/RNA and fluoresces under UV light

• Fragment size can be estimated by running standards (a DNA or RNA ladder) on the gel

• Electrophoresis can also be used to separate proteins, a process known as SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or SDS-PAGE

• The solid matrix consists of linear chains (multimers of polyacrylamide) cross-linked with bis-polyacrylamide molecules, formed in reactions catalysed by ammonium persulphate and TEMED (N, N, N′, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine)

• The percentage of polyacrylamide will affect the separation (around 10% is suitable for protein up to around 100kDa), or gradient gels (e.g. 10–20%) can be used to increase the range of separation

• Sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS) is included to denature the protein and to coat it with negative charges (approximately two SDS molecules per amino acid), so that the proteins will separate purely on molecular mass

• Protein sizes can be estimated by running standards on the gel.

• Southern blot analysis involves cutting DNA with restriction enzyme(s), running the fragments on an agarose gel, transferring onto a membrane, and probing with a labelled complementary DNA probe to the gene of interest (Fig. 15.1)

• Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

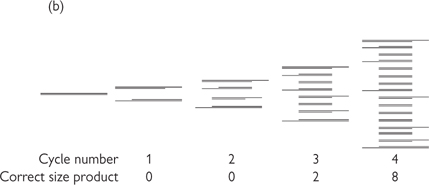

• PCR allows detection of a specific DNA by amplifying it using primers (short sequences of synthetic DNA (oligos) that bind to a specific sequence of target DNA) and thermostable DNA polymerase in a thermocycler machine (Fig. 15.2). PCR products are usually analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining ( p.897), providing a non-quantitative estimate of DNA content. There are, however, quantitative PCR methods such as real-time PCR (qPCR,

p.897), providing a non-quantitative estimate of DNA content. There are, however, quantitative PCR methods such as real-time PCR (qPCR,  p.902)

p.902)

• DNA fingerprinting is a technique used in forensic science to identify whether a sample found at a crime scene matches that from a particular individual

DNA is isolated and digested with restriction enzymes

DNA is isolated and digested with restriction enzymes

The fragments are separated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining

The fragments are separated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining

Due to the sequence variability (polymorphisms) and differences in the length of multiple repeat sequences in introns, the band pattern is unique to an individual

Due to the sequence variability (polymorphisms) and differences in the length of multiple repeat sequences in introns, the band pattern is unique to an individual

• Closely related individuals will have less polymorphisms in their genomes

• This allows a similar approach to be used for paternal testing

• A PCR-based technique can also be used with primers that hybridize with strongly conserved sequences but spanning variable number repeat regions

• Where a disease is known to be caused by a specific mutation in a gene, it is possible to use PCR to screen for carriers and even to detect mutations in cells taken from a fetus in utero

A good example of this is the most common mutation causing cystic fibrosis, the loss of three bases resulting in an amino acid deletion (ΔF508)

A good example of this is the most common mutation causing cystic fibrosis, the loss of three bases resulting in an amino acid deletion (ΔF508)

A PCR product made from primers spanning this region of the gene will be three bases shorter in cystic fibrosis than wild-type

A PCR product made from primers spanning this region of the gene will be three bases shorter in cystic fibrosis than wild-type

This difference can be seen when the PCR products are run on a suitable gel.

This difference can be seen when the PCR products are run on a suitable gel.

Fig. 15.1 Diagram of the Southern blot technique showing site fractionation of the DNA fragments by gel electrophoresis, denaturation of the double-stranded DNA to become single-stranded, and transfer to a nitrocellulose filter.

Reproduced with permission from Mueller RF, Young ID (2003). Emery’s Elements of Medical Genetics, 11th edn. Churchill Livingstone.

Fig. 15.2 Principles of PCR. (a) The three stages of the PCR cycle. (b) There is exponential amplification of the region of interest, whereas longer PCR products undergo linear amplification. Thus after several cycles the correct sized product predominates. (c) There is a linear region of amplification, followed by non-linear region as reagents are exhausted. Classical PCR is non-quantitative and usually analysed by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and visualization by ethidium bromide staining.

• Northern blotting is essentially the same in principle as Southern blotting ( p.898, Fig. 15.1), except that the starting material is isolated mRNA and the probe is usually single-stranded DNA

p.898, Fig. 15.1), except that the starting material is isolated mRNA and the probe is usually single-stranded DNA

• mRNA can be isolated as its poly(A) tail will bind to oligo-d(T) based resins

• RNA techniques involving reverse transcription

• Most other techniques involving RNA require conversion of mRNA into DNA (termed cloned or cDNA). This can be done using an oligo-d(T) primer or random hexamers and the enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT)

• Once mRNA has been converted into cDNA, it is possible to amplify specific sequences using PCR. The whole process is often called RT-PCR. This can be used to see if a particular gene is expressed in a cell type or tissue

• Classic PCR is not quantitative

• However, PCR can be used to quantify the level of mRNA expression using variations of the technique

Semi-quantitative PCR: known amounts of an engineered DNA that binds the same primers but gives a different sized product to the wild-type are added to the sample

Semi-quantitative PCR: known amounts of an engineered DNA that binds the same primers but gives a different sized product to the wild-type are added to the sample

Comparing the intensity of the reaction bands on an ethidium bromide agarose gel allows estimation of the original mRNA concentration

Comparing the intensity of the reaction bands on an ethidium bromide agarose gel allows estimation of the original mRNA concentration

Real-time PCR (qPCR or RT-qPCR when coupled to reverse transcription for RNA quantification): the products of the PCR reaction (amplicons) are detected quantitatively as they are made (i.e. in ‘real time’) during the exponential phase of amplification, rather than at the end of the reaction, This requires fluorescent detection reagents, which can be either dyes binding to double-stranded DNA (e.g. SYBR green) or additional fluorescent probes (e.g. TaqMan probes). RT-qPCR allows a very accurate estimation of the number of copies of mRNA in the starting sample1

Real-time PCR (qPCR or RT-qPCR when coupled to reverse transcription for RNA quantification): the products of the PCR reaction (amplicons) are detected quantitatively as they are made (i.e. in ‘real time’) during the exponential phase of amplification, rather than at the end of the reaction, This requires fluorescent detection reagents, which can be either dyes binding to double-stranded DNA (e.g. SYBR green) or additional fluorescent probes (e.g. TaqMan probes). RT-qPCR allows a very accurate estimation of the number of copies of mRNA in the starting sample1

• The genes expressed by a particular cell or tissue can be seen using an expressed sequence tag (EST) library

• RT-PCR is carried out to make a cDNA copy of all the genes expressed

• The resulting cDNAs are sequenced and the results deposited in a database

• This allows the genes to be identified, and the number of clones of a gene indicate its relative frequency of expression.

• A technique to detect changes in gene expression at the mRNA level in cells involves the use of DNA microarrays, also known as ‘gene chips’

• DNA microarrays have oligonucleotides representing up to the entire gene complement spotted on them in an ordered array

• cDNA is prepared (e.g. from two sets of the same cells grown under different conditions), with one set labelled with red dye (condition 1) and the other green (condition 2)

• Both cDNA samples are hybridized to the gene chip

• Scanning with lasers reveals which genes are expressed under which condition

Red spot signifies only condition 1

Red spot signifies only condition 1

Variations in between, e.g. orange, would indicate expression in condition 1 > in condition 2

Variations in between, e.g. orange, would indicate expression in condition 1 > in condition 2

• Computer analysis allows identification of genes up- and down-regulated

• Care must be used in interpreting microarray data in isolation: this technique does not provide any information as to whether changes in transcription detected are translated into functionally relevant changes in protein expression

• The RNAase protection assay (or nuclease protection assay) is used to identify the presence of and to quantify individual species of RNA in a heterogenous sample of RNA isolated from a cell

• The extracted RNA is hybridized with an antisense RNA or DNA probe complementary to the sequence(s) of interest, forming a double-stranded RNA or RNA–DNA complex

• The probe is generated by cloning a fragment of the gene of interest into a plasmid and using an RNA polymerase to synthesize an antisense RNA transcript

It is labelled by including radioactive (usually 32P) uridine 5ʹ-triphosphates in the reaction mixture

It is labelled by including radioactive (usually 32P) uridine 5ʹ-triphosphates in the reaction mixture

• After hybridization, ribonuclease enzymes that non-specifically cleave only single-stranded RNA (or S1 ribonuclease that cleaves only single-stranded DNA if a DNA probe is used) is added, which digests any free probe, ultimately to free nucleotides

• The reaction mixture is separated by electrophoresis on a polyacrylamide gel, and the presence of intact probe is seen as a distinct band on a radiograph

• This technique is very sensitive but does not reveal the size of the native RNA, as the size of the band represents the size of the probe, and not of the cellular RNA (northern blotting allows size determination,  p.902)

p.902)

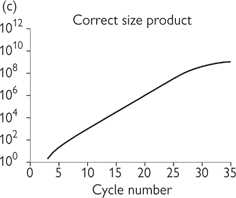

• In situ hybridization (Fig. 15.3).

• This technique can be used to localize a particular mRNA species in:

Fixed tissue, either sectioned or a whole sample (e.g. an embryo)

Fixed tissue, either sectioned or a whole sample (e.g. an embryo)

Unfixed tissue (e.g. cryosections of fresh, frozen brain tissue)

Unfixed tissue (e.g. cryosections of fresh, frozen brain tissue)

• It reveals which cells are expressing the mRNA (unlike PCR where a tissue/cell sample is homogenized)

• The tissue sections are mounted onto microscope slides

• They are then permeabilized either by detergent (e.g. Tween) or enzyme (proteinase K) treatment to allow the labelled probe access to the cellular mRNA

The probe is an antisense RNA made by in vitro transcription

The probe is an antisense RNA made by in vitro transcription

Labelling of the probe used to be either with 32P or 35S (with radiography used to detect signal). It is now nearly always non-radioactive, such as with digoxigenin, biotin or fluorescein

Labelling of the probe used to be either with 32P or 35S (with radiography used to detect signal). It is now nearly always non-radioactive, such as with digoxigenin, biotin or fluorescein

Detection of the probe is with an antibody (immunohistochemistry,

Detection of the probe is with an antibody (immunohistochemistry,  p.920) visualized either by an enzymatic colorimetric reaction or fluorescence, or by direct fluorescence of fluorescein-labelled probes

p.920) visualized either by an enzymatic colorimetric reaction or fluorescence, or by direct fluorescence of fluorescein-labelled probes

• Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is an important subtype of in situ hybridization used for chromosome mapping

• A specific fluorescently labelled DNA probe is used to identify specific chromosomes or chromosomal regions (e.g. can check the number of copies of chromosome 21 as a test for Down’s syndrome).

Fig. 15.3 Expression of the amino acid transporter gene, path, in a late-stage whole-mount Drosophila melanogaster embryo (dorsal view), analysed by in situ hybridization. Path is expressed ubiquitously, but at higher levels in specific tissues (as highlighted here in the midgut, brain, and sensory nervous system).

Image courtesy of Deborah Goberdhan, Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford.

The sequencing of the human genome by the year 2000 was a major scientific achievement and has provided a huge amount of invaluable information. We now know approximately how many functional genes there are in the human genome (about 25 000), their location, and, in some cases, their function. However, this knowledge now needs to be integrated with knowledge about the proteins which these genes produce, how these proteins interact, and how their expression varies in different types of cells and in disease.

This has led to a need for techniques that can identify and quantitate proteins in cellular samples—the science of proteomics. The number and scope of these techniques is increasing all the time. The following includes a short description of the most popular current techniques—protein extraction and mass spectrometry.

To analyse the proteins in a sample, they must first be extracted from the cells within which they are contained.

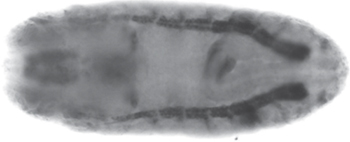

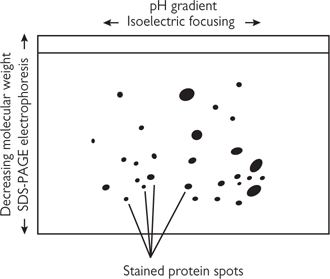

This is a simple and popular technique for separating a mixture of proteins into its constituents:

• The protein extract is mixed with a non-charged detergent, β-mercaptoethanol and urea to solubilize, denature, and disassociate all the proteins

• The resulting mixture is put in a tube of polyacrylamide gel (PAGE) with a gradient of pH across it, and an electric current is applied

• Each protein migrates to its isoelectric point, where the pH of the surrounding gel is such that the protein has no overall positive or negative charge and so does not move

• This can produce resolution into about 50 protein bands

• The tube of gel is soaked in a solution containing the detergent SDS, which is highly negatively charged and so masks the native charge of a protein, making the overall charge now proportional to molecular weight

• The tube of gel is attached to a slab of polyacrylamide gel and an electric current is applied across the gel in a direction at 90° to the isoelectric focusing

• The proteins now migrate according to molecular weight

• This can produce resolution into more than 1000 proteins

• Proteins may be visualized by stains (such as Coomassie or silver) or by autoradiography (if the proteins have been radioactively labelled in vivo)

• A sample will typically produce thousands of individual spots and it would be difficult to identify any difference in pattern between samples by simple inspection. Images of these gels are scanned into a computer system which then compares gels from two different samples and identifies those spots which are different in the two

• In this way, for example, the differences between proteins in normal tissue and a cancer arising from that tissue could be identified.

When these differential spots have been located, the specific proteins within these spots need to be identified. This is usually done by cutting the spot out of the gel and subjecting it to a further analytical step such as mass spectrometry (Fig. 15.4).

Fig. 15.4 Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

A protein has a typical precise mass (if allowance for processes such as glycosylation is made), but it is possible that more than one protein has the same mass (or the same mass within the resolution of the measuring system). However, if a protein is cleaved using a specific enzyme, such as trypsin, then the resultant peptide fragments will have a specific range of molecular weights that can be used to precisely identify the whole protein by mass spectrometry—a peptide ‘fingerprint’.

The rather lengthily named ‘matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight spectrometry’ (MALDI-TOF) is the most common method:

• The enzyme-digested peptide mix is dried onto a slide (ceramic or metal)

• A laser heats the mixture causing formation of an ionized gas

• The ionized particles are accelerated in an electric field towards a detector

• The time taken for a peptide to reach the detector is a function of its mass and charge

• The data from the detector is matched with information on protein databases to give definitive identification of the protein (a task requiring considerable computing resources).

Recently, liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has become the method of choice for proteomic analysis. Furthermore, other ‘-omic’ specialties have evolved:

• metabolomics: attempts to measure all metabolites

• lipidomics: attempts to measure all lipids (sub-discipline of metabolomics).

Whilst measurement of every one of a particular species in a sample is unrealistic, these techniques are gaining prominence for establishing molecular ‘fingerprints’ in complex disease states.

Mass spectrometry is a mainstay of these disciplines, but FT-IR and NMR spectrometry are also commonly used.

• ‘Gold standard’ for protein structure

• X-rays are diffracted by atoms in the protein

• In a well-ordered crystal, the scattered waves reinforce each other at certain points to give spots

• This can be converted into a three-dimensional atomic structure by computer if one knows the amino acid sequence

• At highest resolution, can identify the position of every atom in a molecule, except hydrogen

• The main problem is getting good-quality crystals of pure protein

• Membrane proteins have proved especially difficult.

• Does not require large amounts of protein to be crystallized

• Useful for hard to crystallize proteins

• As protein is in solution, can visualize structure changes (e.g. on binding substrate)

• A small volume of solution is placed in strong magnetic field

• This causes nuclei with magnetic moment (spin) to line up with the magnetic field (e.g. protons)

• Pulses of radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation excite the nuclei and misalign them

• As they realign, they release radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation. This radiation release is affected by adjacent atoms

• By knowing the protein sequence, it is possible to compute a three-dimensional structure from these data.

• This is a specialist application of confocal microscopy ( p.914).

p.914).

• Proteins believed to be interacting are labelled with different colour fluorescent proteins (e.g. GFP (green) and CFP (cyan))

• The proteins are co-expressed in the same cell

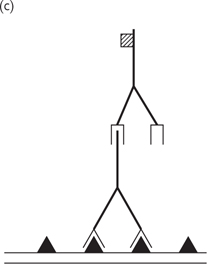

• Excitation of the CFP fluorochrome usually results in cyan light out; however, if the proteins are close enough (1–10nm), then the GFP will be excited by the CFP emission and green light will be seen instead (Fig. 15.5). This energy transfer is called FRET.

Fig. 15.5 Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). To determine whether (and when) two proteins interact inside the cell, the proteins are first produced as fusion proteins attached to different variants of GFP: (a) protein X is coupled to a blue fluorescent protein; (b) if protein X and Y do not interact, illuminating the sample with violet light yields fluorescence from the blue fluorescent protein only; (c) when protein X and Y interact, FRET can now occur.

Reproduced with permission from Alberts B et al. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th edn. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis LLC.

• The protein of interest is covalently bound to a column matrix

• Cell extract is run through this column and interacting protein(s) non-covalently stick to the immobilized protein

• Any proteins adhering to the protein of interest can be eluted and identified using mass spectrometry

• Co-immunoprecipitation is similar, except that an antibody to one of the proteins is used to precipitate out the protein complex

• This can then be probed with antibodies to candidate associating protein(s)

• Method requires proteins to be associated together tightly enough for the complexes to survive co-immunoprecipitation.

• ‘Bait’ protein DNA is fused to DNA-binding domain of a gene activator protein

• ‘Prey’ protein DNA is fused to transcriptional activation domain—usually make from a cDNA library

• If bait and prey associate, then the gene activator and transcription activation domains will interact with each other and turn on a reporter gene (Fig. 15.6)

• From this, the positive prey protein DNA can be selected and sequenced

• Reverse two-hybrid assay can also be used to look for mutations in DNA or chemicals that disrupt a proven association through the two-hybrid system.

Fig. 15.6 The yeast two-hybrid system for detecting protein–protein interactions (see text).

Reproduced with permission from Alberts B et al. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th edn. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis LLC.

• Involves either passing visible light through, or reflecting visible light off, a sample and collecting it with one or more lenses to give a magnified image

• The image can be seen by eye, or recorded photographically (conventionally or digitally)

• Light microscopy is limited to a resolution of about 0.2μM, and the sample needs to be dark or strongly refracting to get a good image

• Light from out of the focal plane also limits resolution

• Native cells and tissues often lack the contrast to be studied by light microscopy without staining ( see p.919)

see p.919)

• Staining is with dyes on fixed (i.e. dead) tissue

• The tissue processing and staining can produce artefacts

• At least some of these limitations can be overcome by more advanced optical techniques which non-invasively increase the contrast of the image, for example phase contrast microscopy.

• A variant on light microscopy involves using high energy light (often lasers) to illuminate the sample

• Fluorescent compounds absorb energy at one wavelength and emit it at another (lower) frequency

• Optical filters allow imaging of just the emitted fluorescent signal

• Fluorescence can come from within the native sample (autofluorescence) or more normally from:

• Labelling with a chromophore-conjugated antibody, e.g. with FTIC or fluorescein (green) and TRITC or rhodamine (red)

• Genetically fusing a fluorescent protein to the protein of interest

The best known of these proteins is GFP

The best known of these proteins is GFP

Small genetic variations in GFP had produced other colours, e.g. blue (BFP), cyan (CFP), yellow (YFP).

Small genetic variations in GFP had produced other colours, e.g. blue (BFP), cyan (CFP), yellow (YFP).

• An enhancement on fluorescent microscopy is confocal microscopy

• Traditional light and fluorescent microscopy resolution is limited by light from out of the focal plane

• Confocal microscopy allows the production of an optical section through a sample by using a pinhole to exclude light that is out of focus (Fig. 15.7)

• A two-dimensional picture can be built up by scanning the sample, producing an ‘optical section’

• A three-dimensional image can also be produced by focusing and scanning at different levels in the sample and using computerized image processing to ‘stack’ the optical sections.

Fig. 15.7 Two images of the same intact gastrula-stage Drosophila embryo, stained with a fluorescent probe for actin filaments: (a) conventional, unprocessed image is blurred by presence of fluorescent structures above and below the plane of focus; (b) this out-of-focus information is removed in confocal image.

Reproduced with permission from Alberts B et al. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th edn. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis LLC.

• Uses a beam of electrons rather than light to illuminate the specimen–the shorter wavelength allows higher resolution (at least 100-fold higher magnification than for light microscopes)

• Electrostatic and electromagnetic ‘lenses’ control and focus the electron beam to produce a focused image

• Images can be made on film or by specialized digital cameras

• As specimen is in a vacuum, can only use fixed tissue

• There are different kinds of electron microscopy, the most commonly used in biology are:

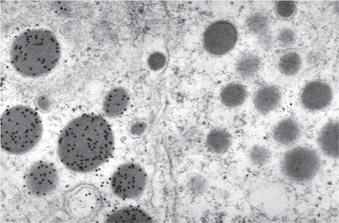

• Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)—electrons pass though ultra-thin sections of sample, and the more electron dense the structure the darker it appears in the image (Fig. 15.8)

• Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)—the sample is scanned by a focused electron beam and the reflected energy is measured, allowing large specimens to be imaged with such a large depth of field that the three-dimensional shape is well represented

• Samples need to be stained to increase electron absorbance (contrast)

Heavy metals are used, such as osmium, lead, palladium, tungsten, and uranium

Heavy metals are used, such as osmium, lead, palladium, tungsten, and uranium

For SEM, the sample is coated with stain, such as gold, palladium or tungsten

For SEM, the sample is coated with stain, such as gold, palladium or tungsten

• Can be combined with immunohistochemical techniques ( p.920) with antibodies conjugated to small (e.g. 10nm) gold particles (Fig. 15.8).

p.920) with antibodies conjugated to small (e.g. 10nm) gold particles (Fig. 15.8).

Fig. 15.8 Immunogold labelling for growth hormone in secretory granules in the anterior pituitary. The cell on the right does not contain growth hormone. (Scale bar = 400nm).

Image courtesy of Helen Christian.

The examination of isolated cells rather than cohesive tissue histology, ( p.918).

p.918).

• Exfoliative cytology—uses cells that are shed or scraped from body surfaces (e.g. bronchial epithelial cells that are coughed up in sputum, epithelial cells from the uterine cervix removed using a plastic brush)

• Aspiration cytology—uses cells which have been aspirated from a solid organ using a fine gauge needle and syringe (e.g. cells from a breast lump).

• Diagnosis of malignancy—e.g. detection of bronchial carcinoma by exfoliated cancer cells in sputum

• Screening for malignancy—e.g. detection of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) in cells scraped from the cervix in the UK national cervical screening programme

• Detection of microorganisms—e.g. Trichomonas vaginalis in cervical smears, Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii) in bronchoalveolar lavage from immunocompromised patients.

• Smearing of cells directly onto glass slides or cytocentrifuging from a transport medium

• Brief fixation of cells using an alcohol

• Staining of cells by a histochemical method such as Papanicolaou

• Interpretation by a cytopathologist or cervical screener

Literally, examination of tissue (from the Greek histos = tissue). However, in current usage, it refers to the examination of tissue by light microscopy after it has been processed into thin sections. Although the histological appearances of tissue are altered by many artefact-inducing processes, these artefacts are reproducible, and there is a huge body of knowledge about the histological appearances of disease, which has built up over the past 150 years.

• Tumour diagnosis—histology is the primary method of definitive tumour diagnosis in current medical practice. Although imaging (such as CT or MRI) may provide very clear views of definite masses which are presumed to be tumour (e.g. multiple masses in the liver which are most likely to be metastases), there are some non-neoplastic processes which can produce masses on imaging (e.g. abscesses), so a definite tissue diagnosis by histology is still required

• Tumour staging—the extent of tumour spread (e.g. metastasis to local lymph nodes) is an important determinant of an individual patient’s prognosis. Although modern imaging is, again, very valuable in this process, histology is still the main method of assessing tumour stage in surgically resected tumours (e.g. colorectal cancer)

• Non-neoplastic diagnosis—the histological appearances of many non-neoplastic diseases are reproducible and specific to a particular diagnosis. Inflammatory conditions of the skin are a good example of a spectrum of diseases which can be diagnosed by histology

• Assessment of the body’s response to disease—inflammatory and fibrotic processes are easily assessed by histology, and so histology may play an important role in determining the extent of a non-neoplastic disease. An excellent example is hepatitis C—histological examination of a liver biopsy can determine the amount of inflammatory activity (and, therefore, the predicted response to treatment such as interferon therapy) and also the amount of damage that has already been caused to the liver (by assessing the amount of fibrosis from none through to frank cirrhosis)

• Detection of microorganisms—although microbiological culture is generally more sensitive than histology, there are some circumstances where histology is an effective technique for detecting microorganisms (e.g. Helicobacter pylori in endoscopic gastric biopsies).

Histology is a relatively simple technology that has changed little over the decades. The most significant advance has been the use of specific antibody stains ( p.920). The basic steps are:

p.920). The basic steps are:

• Fixation of the fresh tissue by a chemical solution (usually formaldehyde) which cross-links proteins

• Selection of a sample of the tissue if it large; small biopsies are examined in their entirety

• Processing of the tissue from the formaldehyde solution through progressive dehydration by alcohol into 100% liquid alcohol

• Embedding of the tissue into paraffin wax

• Cutting of thin (5–10μm thick) sections from the wax block

• Mounting of the wax sections onto a glass slide

• Staining of the section on the glass slide, usually by haematoxylin and eosin dyes which stain nuclei, dark purple, and cytoplasm, pink

• Interpretation of the sections by a histopathologist (a medically qualified doctor with postgraduate training in histology)

• Issue of a written report of the histological findings.

Although relatively simple, the tissue processing and staining is labour intensive and takes 1–2 days to complete.

If an immediate histological diagnosis is required (e.g. an unexpected finding of disseminated tumour at an exploratory laparotomy), then a small tissue sample can be frozen in liquid nitrogen and sections cut and stained from this within a few minutes.

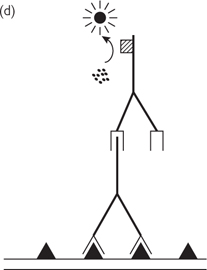

Immunohistochemistry allows the identification of proteins in cells and tissue samples (or thin sections of tissue), using specific antibodies (Figs 15.7–15.9). Once the tissue has been incubated with the primary antibody (i.e. the one raised to the protein of interest), the antibody binding pattern can be visualized in a number of ways, usually involving the use of a secondary antibody (2°Ab) that recognizes the primary one:

• The 2°Ab can be conjugated to an enzyme such as horseradish peroxidase, which catalyses a colorimetric reaction to stain the area(s) of the cell/tissue where the protein is present (Fig. 15.9). This is a relatively old-fashioned approach, largely replaced by fluorescent staining (Fig. 15.7, p.915), as described further on  p.914.

p.914.

• The staining is visualized by microscopy (either light or fluorescent/confocal)

• Alternatively, the 2°Ab can be conjugated to small (e.g. 10nm) particles of gold, which can be localized by electron microscopy (Fig. 15.8, p.916).

Fig. 15.9 (a) A specific protein (shown as triangle) is present on the surface of a cell; (b) a specific primary antibody binds to this protein; (c) a secondary antibody binds to the tail end (Fc portion) of the primary antibody; (d) the secondary antibody has an enzyme attached to it which catalyses a reaction from a colourless substrate to a colourless substrate to a coloured dye product which can be seen by light microscopy.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry uses a similar approach, except instead of being conjugated to an enzyme, the 2°Ab is conjugated to a fluorescent chromophore.

• Usual chromophores include FITC, fluorescein or Cy3 (green) and TRITC, rhodamine or Cy5 (red)

• Dual labelling of two proteins allows identification of areas of co-expression (red + green = yellow staining).

Much higher levels of detail can be imaged using an electron microscope (at least 100-fold higher resolution than with a light microscope).

• In this case, the 2°Ab can be conjugated to a small particle of gold, which is electron-dense and, therefore, will appear black

• Use of different size particles (e.g. 5nm and 10nm) allows more than one protein to be localized.

Although not strictly immunohistochemistry, one modern approach has been to genetically engineer proteins that are endogenously fluorescent. This can be done by adding the coding sequence for the ~30KDa protein, GFP, originally isolated from the jellyfish Aequoria Victoria.

• Experimental mutations in the gene for GFP has allowed the development of an enhanced GFP (EGFP) and other colours, e.g. cyan (CFP) and yellow (YFP)

• The use of these GFP-fusion proteins has allowed imaging of live samples.

Immunohistochemistry has a very wide application in diagnostic histo-pathology to determine the precise nature of a tumour. This, in turn, allows the optimal therapy to be planned for the patient. Increasingly, individualized tumour therapies are being developed which rely on a specific protein being present in a tumour—the therapy itself is often an antibody, so the tumour of an individual patient will require immunohistochemical staining to identify the presence or absence of this protein.

Common clinical uses of immunohistochemistry include:

• Oestrogen receptor assay in breast cancer: all breast cancers are immunohistochemically stained for the oestrogen receptor protein and if a tumour does contain oestrogen receptor (‘ER positive’), then the patient will be treated with the anti-oestrogen drug, tamoxifen, or one of its derivatives

• HER2 receptor assay in breast cancer

• If a breast cancer overexpresses the epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) protein, then it may respond to the drug trastuzumab (Herceptin), which is a monoclonal antibody directed against this receptor. Again, immunohistochemistry is required to determine the presence of this protein

• In the UK, at present, Herceptin is used in the palliative treatment of metastatic breast cancer

• Typing of lymphomas: lymphomas (malignant tumours of lymphoid cells) are a heterogeneous group of tumours with widely differing prognoses. Most lymphocytes have a relatively similar appearance by conventional light microscopy, so immunohistochemistry is widely used to detect specific cell surface proteins which allows classification of the tumour into a specific lymphoma type.

Microorganisms can be viewed in samples by microscopy after treatment with special stains.

• Gram stain. Allows detection of Gram-positive and negative bacteria, cocci, and rods. Also stains yeast. Some bacteria stain poorly

• Ziehl–Neelsen stain. Used to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis and related mycobacterial species that are acid-fast and stain poorly with the Gram stain. Can be modified to detect Nocardia sp. Other stains such as fluorochromes (e.g. auramine-rhodamine) are more sensitive for screening specimens for Mycobacteria sp.

• Potassium hydroxide (KOH). Used on wet mounts to detect fungi. Calcofluor white staining and fluorescence microscopy is more sensitive. In biopsy specimens, silver stains such as periodic acid–Schiff are used to detect fungi

• Direct fluorescent antibodies (DFA). A monoclonal antibody specific to a microorganism may be tagged with a fluorochrome and used to detect the microorganism in a specimen

• Giemsa stain. Used on blood films to detect parasites (malaria in particular) and, occasionally, other intra-cellular pathogens

• Electron microscopy. Detection of viruses in certain samples

• Direct microscopy on unstained samples. Used on unicellular parasites and the larger ectoparasites

• Histologic specimens. Special stains and pathological features (e.g. granulomata) aid diagnosis

Available for specific microorganisms and samples (e.g. CSF). Detect antigen by latex agglutination (aggregation of particles) or enzyme immunoassay (release of light). DFA and fluorescence microscopy is also a rapid means of antigen detection.

• Media. Cultured on solid or liquid media that can be enriched to optimize growth of specific bacteria, selective to allow only growth of certain bacteria or to contain an indicator so that bacteria with a certain characteristic (e.g. the ability to ferment a specific sugar) are detected

• Blood agar is an enriched all-purpose media

• MacConkey agar is selective for common Gram-negative bacteria and contains an indicator so that lactose fermenters appear red

• Broth cultures allow inoculation of greater volumes and are more sensitive

• Conditions. Automation allows early detection of bacterial growth by a characteristic such as microbial production of carbon dioxide. Growth conditions (temperature and atmospheric conditions) are adjusted depending on the requirements of specific microorganisms. Anaerobes require culture without oxygen

• Identification. Bacteria are speciated by colony morphology on solid media (including haemolysis pattern on blood agar), Gram stain, biochemical tests, serology, motility pattern, flagella, and spores. Multiple tests require computer-based programs for precise identification.

Grow on specific solid (e.g. Lowenstein–Jensen) and liquid media. Identification is by growth rate, colony morphology, biochemistry, and the use of molecular techniques.

Grow on specific agar and liquid media (e.g. brain-heart infusion). Identification includes detecting yeasts or hyphal elements, the pattern of sporing bodies, and biochemical tests. Culture of mycobacteria and fungi is slow (often requiring weeks) and dangerous (necessitating a biosafety level 3 laboratory).

Cultured in cell lines and identified by the pattern of cytopathic effect or reaction with specific fluorescent antibody.

Used for detection of viruses, parasites, fungi, and fastidious (difficult to culture) bacteria.

Requires identification of specific IgM or a four-fold increase in IgG antibody titre. Antibody is detected by using a secondary antibody with a tag that allows detection of bound antibody–antigen complexes. Detection may be by agglutination, precipitation, complement fixation, or radio-activity, but the majority of commercial assays now use indirect fluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 15.10 p.927). ELISA can be adapted to detect IgG or IgM antibody or antigen.

Western blotting allows microbial proteins to be separated by SDS-PAGE (p.897) and transferred (usually using an electrical current) to a nitrocellulose membrane. Reaction of patient sera with the proteins is detected by a specific pattern of bands when treated with a secondary antibody.

Fig. 15.10 Principles of ELISA. Specific antigen (Ag) is bound to the wells of the test plate and blocking protein (BP) is added to stop non-specific antibody binding to the wells. The patient sample is added and antibody binds to antigen. A secondary antibody, with an attached enzyme, is added. Addition of substrate results in cleavage of a chemical and release of light. The optical density is measured in a microplate reader.

• PCR ( p.898). Allows detection of a variety of micro-organisms. Microbial DNA is amplified using primers (short sequences of DNA) that bind to a specific sequence of microbial DNA. Analysis can be qualitative or quantitative (qPCR,

p.898). Allows detection of a variety of micro-organisms. Microbial DNA is amplified using primers (short sequences of DNA) that bind to a specific sequence of microbial DNA. Analysis can be qualitative or quantitative (qPCR,  p.902). RNA can also be amplified using RT-PCR (

p.902). RNA can also be amplified using RT-PCR ( p.902)

p.902)

• Molecular probes. Chemiluminescent DNA probes target sequences of ribosomal RNA and aid speciation of Mycobacterial sp. in culture. In situ hybridization allows the detection of nucleic acid derived from microorganisms in biopsy specimens

• Restriction patterns. Microbial DNA is cleaved using endononucleases (cleave at specific sites). The pattern of fragments on a gel provides a molecular fingerprint, useful in epidemiological studies

• 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) sequencing. Useful when bacteria cannot be cultured or when identification is equivocal with phenotypic tests such as biochemical testing. Hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA allow speciation. Can be combined with PCR when bacteria not cultured as in culture-negative bacteria

• Proteomics. Identification of the entire proteome expressed by a microorganism can enable speciation.

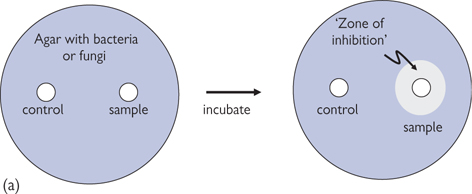

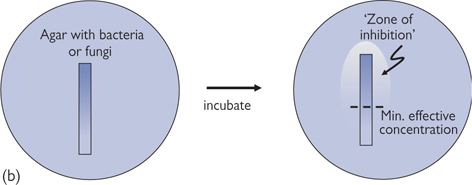

• Disc diffusion susceptibility testing. An antimicrobial agent diffuses from an impregnated disc onto an agar plate containing bacteria or fungi (Fig. 15.11a)

• MIC testing. Microorganisms are grown in a liquid media with a known concentration of antimicrobial agent. Can be adapted to mycobacteria, fungi, and viruses, to solid media, or to use with a strip impregnated with drug (E-test, Fig. 15.11b)

• Molecular techniques. Detection of genes associated with resistance (e.g. the mecA gene for meticillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus). Resistance mutations in mycobacteria or viruses are detected by PCR (genotypic assays) and are compared with MIC estimates (phenotypic assays).

Fig. 15.11 (a) Disc diffusion susceptibility test. An impregnated disc is placed on a agar plate containing bacteria or fungi. When there is antimicrobial (fungicide) agent impregnated in the disc (sample) it clears a ‘zone of inhibition’ in the bacteria (fungi), whereas the control does not. (b) E-test form of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing. An strip impregnated with a gradient of antimicrobial (fungicide) agent (highest concentration at top) clears a ‘zone of inhibition’ in the bacteria (fungi), with it possible to estimate the minimum effective concentration.

Flame photometry has long been used to detect metal ions (Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+). The principle underlying the technique is that the different metal ions burn with different coloured flames. Thus, a solution containing such ions can be sprayed through a flame, and the change in flame colour detected by a spectrophotometer. This technique used to be routinely used to establish Na+ and K+ levels in the blood, although nowadays, ion-selective electrodes are often used for this purpose.

The colour that a substance appears to our eye is determined by those wavelengths of white light that are reflected by it—all the other wavelengths are absorbed. A spectrophotometer is an instrument that determines the amount of light of different wavelengths—(usually between ultraviolet (~200nm) and infrared (~600nm)—that is absorbed by a dissolved compound of a given depth (usually 1cm—the pathlength). The amplitude of the peaks in the ‘absorption spectrum’ (measured in an arbitrary scale of absorption units from 0.0–3.0) is directly proportional to the concentration of the compound present (Beer–Lambert law). This is a simple means of measuring the concentration of highly coloured compounds that are found in high concentrations in biological samples (e.g. haemoglobin). Beer–Lambert Law:

Absorbance = εcl

where:

ε = molar extinction coefficient (M–1cm–1)

c = concentration (M)

l = pathlength (cm).

The range over which spectrophotometry is effective is very limited (e.g. for haemoglobin, concentrations of 0.5–5μM can easily be measured; higher concentrations require dilution to be measurable by this means; lower levels are undetectable). Unfortunately, the majority of substances that we want to measure are not coloured (although most absorb in the ultraviolet spectrum) or do not lend themselves to direct spectrophotometric analysis. However, a number of colorimetric, luminescence, and fluorescence assays have been developed for specific compounds. These assays rely on highly specific reactions of the substance of interest with an added reagent. The reaction gives rise to a highly coloured, luminescent, or fluorescent compound that can be detected in a spectrophotometer, luminometer, or fluorometer. Many of these assays are now available in kit form for use with 96 well plates that can be read in a plate-reader for very rapid throughput of large numbers of samples.

RIA is often the technique of choice for determining the concentration of specific peptides and proteins in blood or urine samples. Kits are now available for a huge range of peptides and proteins. The principle involves introducing the sample into a tube that is coated with a known amount of the specific antibody for the antigen of interest.

• An excess of radio-labelled antigen is then added to the tube, which will bind to any antibody that is still available

• The tube is then washed out, leaving the antibody bound to a mixture of unlabelled ligand from the sample and radio-labelled ligand

• The amount of the antigen in the sample is inversely proportional to the amount of radioisotope present, as determined by measuring the radioactivity in a γ-counter and comparing the reading to those of standards of known amount. It is important to note that the standard curve for RIAs is not linear—it is usually fitted with a cubic spline curve.

ELISA ( p.925, Fig. 15.10) is a popular means of detecting peptides and proteins that does not require the use of radioisotopes. ELISAs are generally purchased in kits consisting of pre-formed 96-well plates coated with an antibody specific to the antigen of interest.

p.925, Fig. 15.10) is a popular means of detecting peptides and proteins that does not require the use of radioisotopes. ELISAs are generally purchased in kits consisting of pre-formed 96-well plates coated with an antibody specific to the antigen of interest.

• After addition of sample to the wells, a secondary enzyme-linked antibody is added to the wells, which binds to the antibody–antigen complex

• Addition of the colourless substrate for the enzyme that is linked to the antibody results in the formation of a coloured product, the amount of which is measured spectrophotometrically in a plate-reader and is proportional to the amount of enzyme bound and, consequently, the amount of antigen present.

Chromatography works on the principle that substances can be separated according to their specific chemical characteristics (e.g. charge, molecular size, and/or partition in aqueous/organic solvents). In this way, we can separate and measure the concentrations of the components of very complex mixtures, including blood plasma, tissue, and cell extracts.

• Chromatography usually utilizes a ‘mobile phase’—a solvent in the case of liquid chromatography (high-performance liquid chromatography; HPLC) and an inert gas for gas chromatography (GC)—that passes through or over a ‘stationary phase’ in a column

• The greater the interaction of the substance of interest with the stationary phase, the longer it will take to pass through the column, giving it a longer ‘retention time’

• The effluent from the column is passed through a detector, which can work by either measuring the absorbance in the ultraviolet region of the spectrum or by electrochemical means. Compounds appear as ‘peaks’ on a chart—the higher the peak, the more of the compound is present. The precise amount present can be analysed by comparing the peak height or area to those of standards of known concentration. Sometimes, the specificity of HPLC can be improved by exposing the components of the mixture to a reagent that will fluoresce when it reacts with a particular target molecule. The amount of the fluorescent product can be detected downstream of the column using a fluorescence detector

• A recent refinement to chromatography techniques is their combination with mass spectrometers that can be used to determine the molecular mass of the substance after separation by gas chromatography (GC/MS) or HPLC (LC/MS). Identification of unknown substances requires tandem mass spectrometry, whereby the mass of the intact molecule of interest is detected in the first mass spectrometer prior to shattering of the molecule and identification of the daughter ions generated. Comparison of these features with online databases usually narrows the field to one or two possible candidates.

• Flow cytometry is a technique for analyzing and quantifying small particles, such as cells, which are suspended in a stream of liquid

• A laser is shone through the stream of liquid, and detectors measure the forward and side scattered light and fluorescence (if required)

• The forward scattered light signal allows determination of the cell volume

• The side scattered light allows interpretation of intracellular features (e.g. shape of the nucleus, amount of intracellular organelles)

• Cells with a fluorescent tag (e.g. labelled with a chromophore-conjugated antibody or expressing a GFP-tagged protein) can be counted (quantified)

• Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (often known as FACS™, an acronym trademarked by Becton, Dickinson, and Company, USA) is a specialization of flow cytometry

• The parameters of the liquid stream are adjusted so that the cells are relatively widely spaced within the stream

• A vibrating mechanism breaks the fluid stream into droplets that (statistically) contain only a single cell

• A fluorescent detector identifies fluorescent-positive cells just before the stream breaks into droplets, and these droplets are given an electrical charge

• Charged droplets are diverted by an electrostatic deflection system, thus separating fluorescent cells from non-fluorescent ones.

In order to examine a physiological or pathological process, or to determine the characteristics of drug action, it is necessary to work with live cell cultures or tissue samples. A range of different techniques is available to help elucidate biological processes.

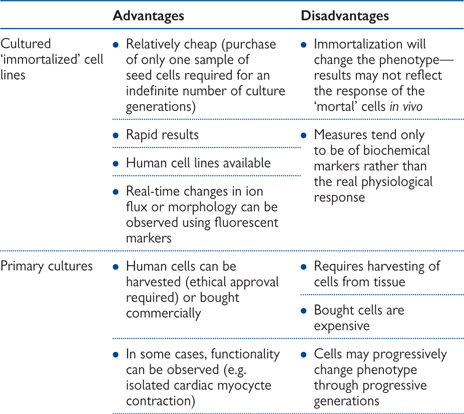

Literally, this term means ‘in glass’ and can equally apply to experiments with cell cultures, tissue homogenates, or functionally intact pieces of tissue. These are very useful techniques for providing clues as to the cellular mechanisms involved in physiological, pathological or pharmacological processes, without the complications of the highly complex physiology of a whole organism. This simplicity is, however, also the major limitation of in vitro investigation: extrapolation of in vitro results to the in vivo situation is inherently dangerous on the basis that the complex integrated systems and metabolic processes of the whole body are likely to have a bearing on the processes involved in vivo. Table 15.1 summarizes the benefits and drawbacks of in vitro experiments.

This term is often confused with in vitro. Ex vivo should only be applied to experiments that are conducted on cells or tissue that have been removed from an animal or human, after having been subjected to a drug treatment in vivo. Under these conditions, the therapeutic intervention is subject to all the metabolic processes that occur in a fully functional animal or human, but the end-point of the experiment is a specific test that is carried out on excised tissue.

In humans, these experiments are only possible when a realistic end-point can be achieved from easily obtainable tissue (e.g. skin biopsy, blood samples), but in animals, these experiments might be terminal (i.e. the animal is killed prior to tissue removal), allowing any tissue sample to be used to determine the drug effect (e.g. blood vessel, brain tissue, liver homogenate). The in vivo element of these experiments (human or animal) means that they require ethical permission from the respective authorities.

Clearly, where possible, the most accurate reflection of a drug effect on a physiological or pathological process will be obtained from experiments in vivo. However, this is a highly emotive issue because it usually involves vivisection in laboratory animals. In almost all cases of drug development, this is an essential step, prior to ethical approval for clinical studies, to highlight any unforeseen side-effects or problems.

As with any experiments, in vivo studies should be designed to test specific hypotheses, with clear, achievable end-points. Ethical review panels have to be assured that any animal suffering will be minimized, or preferably avoided altogether, before permission will be granted. Consideration must be given to the best species to use as a model for the human condition in question, and power calculations should be conducted to determine how many animals are likely to be needed in each group to ensure a reasonable chance of observing a statistically significant difference between placebo and treatment groups. Where possible, randomized, blinded, crossover studies should be considered, to improve the robustness of the results obtained.

• Mice are widely thought to be the best model organism for studying human disease due to their (patho)physiology being so similar to ours1

• Mouse genes can be mutated randomly (by exposure to radiation or chemicals, e.g. ENU)

This approach has been aided by advances in high throughput sequencing

This approach has been aided by advances in high throughput sequencing

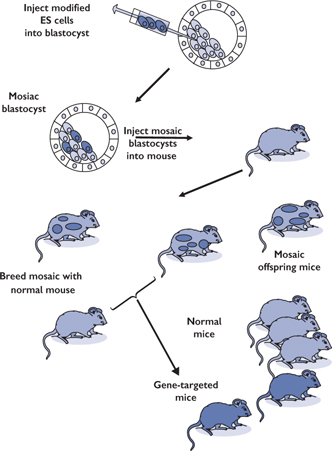

• More sophisticated genetic approaches can be used to target particular genes, for example gene trapping and gene targeting (Fig. 15.12)

Gene trapping is random whereas gene targeting is specific for a gene of interest

Gene trapping is random whereas gene targeting is specific for a gene of interest

This technology won its inventors the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 20072

This technology won its inventors the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 20072

• There are disease model mouse strains that have genetically engineered susceptibility to particular diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and Huntingdon’s disease

• One of the biggest challenges is to identify the phenotype of the mutant mice

As there are a number of worldwide consortia undertaking large-scale studies, there needs to be consistency in phenotyping.

As there are a number of worldwide consortia undertaking large-scale studies, there needs to be consistency in phenotyping.

Table 15.1 Advantages and disadvantages of various in vitro techniques

Fig. 15.12 Method of gene targeting in mice.

Stem cells have the potential to develop into many different cell types in the body during early life and growth. Stem cells generate a continuous supply of terminally differentiated cells.

Stem cells are not terminally differentiated and can divide without limit.

When a stem cell divides each daughter can either remain a stem cell or go on to become terminally differentiated with a specialized function, such as a muscle or red blood cell, via a series of precursor cell divisions.

Stem cells are defined by three important characteristics:

• They are non-differentiated (unspecialised) cells

• They have the ability to divide and renew themselves by cell division for long periods (long term self-renewal)

• Under certain physiological or experimental conditions they can be induced to become specialized cell types.

• In the 3–5-day-old embryo (the blastocyst), the inner cells are the stem cells that give rise to the entire body

• Non-embryonic ‘somatic’ or ‘adult’ stem cells

• Discrete populations of stem cells present in adult tissues such as the gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow generate replacements for cells lost through normal wear and tear. Typically adult stem cells generate the cell types of the tissue in which they reside but some experiments suggest adult stem cells can give rise to cell types of a different tissue

• Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

• These cells arise from adult specialized cells that have been reprogrammed genetically to become stem cell-like

• Using genetically manipulation (viral transfection) expression of just four genes is sufficient to convert adult skin fibroblasts into iPSCs (however at a low conversion rate).1

In some organs (such as gut, bone marrow) stem cells regularly divide to repair and replace damaged tissues. In other organs (such as pancreas, heart) stem cells only divide under special conditions.

Haematopoietic stem cells give rise to all the types of blood cells: red blood cells, B-lymphocytes, T-lymphocytes, natural killer cells, neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and macrophages

• Mesenchymal stem cells give rise to connective tissue cells such as bone cells (osteocytes), cartilage cells (chondrocytes), fat cells (adipocytes)

• Neural stem cells give rise to the three major types of cell in the brain: nerve cells (neurones), and two types of non-neuronal cells, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes

• Epithelial stem cells in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract are located in deep crypts and give rise to enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells and enteroendocrine cells.

• Skin stem cells occur in the basal layer of the epidermis and at the base of hair follicles. The epidermal stem cells give rise to keratinocytes and the follicular stem cells can give rise to both the hair follicle and to the epidermis.

Experiments have reported that certain adult stem cell types can differentiate into cell types seen in tissues or organs other than those expected from the cells predicted lineage. Also certain adult cell types can be reprogrammed into other cell types by genetic modification.

• For example insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells can be produced from pancreatic exocrine cells by introducing three key β-cell genes.2

The regenerative properties of stem cells allow the potential for stem cell treatment of diseases (‘cell-based therapies’) and this is an active area of current research. Examples of potential treatments include:

• Regenerating bone using cells derived from bone marrow stroma

• Developing insulin producing cells for type 1 diabetes

• Repairing damaged heart muscle following a heart attack with cardiac muscle cells

• Regeneration of neurones to treat Alzheimer’s diseases or spinal cord injury.

The generation of personalized ES cells for therapeutic cloning requires a supply of human egg cells from women donors and is a technique fraught with ethical problems. The use and manipulation of iPSCs therapeutically bypasses the ethical problems of ES cell generation from early embryos. However, despite the potential use of iPSCs in regenerative medicine, the safety of viral vectors in patients is not clear and developing methods for growing cells and tissues in the laboratory for cell-based therapies is an area of active research.

Ethical approval should be sought at the earliest opportunity—evidence of in vitro and in vivo studies in animals is usually required, together with toxicology data. Clinical trials proceed in a standardized fashion:

• Phase I: a small study (20–80 subjects) to help evaluate the correct dosing range, the safety of the drug, and any side-effects. First-in-man studies are often carried out in healthy volunteers before trying them in patients from the target group

• Phase II: a larger study group is involved (100–300 patients). A clear end-point is identified, which must be achieved for the drug to be taken further

• Phase III: a very large study (1000–3000 patients) to confirm the drug efficacy, perhaps in comparison to an existing therapy and usually also compared to a placebo group (‘dummy’ treatment with the same appearance as the study drug but without the active agent). Side-effects are closely monitored and information collected as to the safety of the drug prior to marketing

• Phase IV: post-marketing studies that help to determine the optimal use of the drug and to clarify the risks and benefits of the drug

• Expanded access protocols: clinical trials (phases I–IV) are necessarily conducted on a very restricted group of patients, minimizing any confounding factors that might compromise the findings of the studies. As a result, a large number of potential patients who might benefit from the drug on trial are excluded. In some cases, the pharmaceutical company might apply for ‘expanded access’ to allow patients who do not meet the strict criteria for the trials (e.g. with regard to age or gender, complex medical history) to gain access to the trial drug. This is usually only granted in cases where there is no credible alternative therapy, particularly if the disease is life-threatening. Furthermore, there should be no evidence from the trials that precede the application to suggest that there might be detrimental effects.

As with in vivo animal studies, great consideration must be given to minimize any potential pain or suffering of the subject of clinical trials, with the added caveat that the subject must be fully informed of the procedure and possible implications. Patients must sign a consent form to that effect. End-points must be clearly stated prior to the experiment and, unless the nature of the experiment dictates otherwise, the trial should be of a double-blind (both patient and researcher are unaware of whether the administered agent is placebo or test drug), randomized, crossover (some patients receive drug first, followed at a later date by placebo or vice versa) style. This is not always possible—for example, it is sometimes necessary to run parallel groups, one of which receives placebo while the other receives drug treatment. In these cases, it is essential that the groups be matched as closely as possible (e.g. medical history, age, gender).

In very large trials, an interim analysis is usually carried out: if the drug is found to be detrimental, or indeed highly beneficial, the trial may be stopped on the grounds that it is unethical to continue.