Principles of molecular genetics

Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics

The term ‘gene’ is used to represent an inherited unit of information, as reported by Mendel1 in his experiments on the garden pea, and can be interpreted in two different ways.

• At a gross level, genes determine the phenotype, e.g. morphological characteristics such as eye or hair colour

• At a molecular level, genes are a stretch of nucleotides that code for a polypeptide, so determine the amino acid sequence and, therefore, the function of a protein

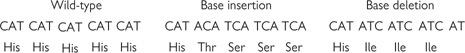

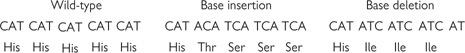

• Each amino acid is coded for by a three base pair sequence (known as a codon; Table 3.1)

• As there are 22 pairs of homologous chromosomes, plus the sex chromosomes, most genes are present twice. The copies are known as alleles.

There are different types of mutation in genes that will be of varying seriousness if they occur in the coding regions (the exons), depending on the nature of the change.

If this happens in the coding sequence, the result may be either:

• No change in the amino acid sequence of the polypeptide

• Due to the fact that there are four bases and the codons are triplets, there are 43 = 64 codons for 20 amino acids. Therefore a number of codons code for each individual amino acid, known as redundancy

• A change in the amino acid coded for by the changed triplet

• This may or may not affect the function of the protein, depending on the amino acid changed, what it is changed to, and its role in the protein function. For example, many of the amino acids in a protein can be regarded as scaffolding, simply holding the catalytic residues in the correct three-dimensional (3D) space

• The change in the base pair may result in the triplet coding for a stop codon (non-sense mutation)

• This will result in a truncated protein, which is unlikely to have the function of the wild-type.

This is likely to have a serious effect on the protein structure and function.

• Will cause a mis-sense or frame-shift mutation, where the amino acid coding will be disrupted by the inserted/deleted base. For example:

• Usually, will result in a stop codon being coded for, but even if not, it is virtually impossible that a mis-sense protein will be able to substitute for a wild-type one.

• Insertions or deletions of anything other than multiples of three bases will cause frame-shift mutations of molecular genetics

• Insertion/deletion of multiples of three will insert/delete amino acids

• As with point mutations, the severity of this will depend on the protein involved and which amino acids are affected

• The importance of even losing single amino acids is highlighted by the condition cystic fibrosis ( OHCM8 p.166), where the most common genotype is ΔF508—the loss of the Phe residue at position 508 out of 1480. This results in the trafficking failure of the CFTR protein to the epithelial membrane

OHCM8 p.166), where the most common genotype is ΔF508—the loss of the Phe residue at position 508 out of 1480. This results in the trafficking failure of the CFTR protein to the epithelial membrane

• Dynamic mutations are when nucleotide repeats expand generation by generation

When a certain threshold of repeats is reached, the disease phenotype will become apparent e.g. Huntingdon’s disease (

When a certain threshold of repeats is reached, the disease phenotype will become apparent e.g. Huntingdon’s disease ( OHCM8 p.716)

OHCM8 p.716)

This accounts for the phenomenon of anticipation, where a disease phenotype becomes progressively more severe from one generation to the next

This accounts for the phenomenon of anticipation, where a disease phenotype becomes progressively more severe from one generation to the next

• Most mutations are associated with a loss of function of the protein coded for by the mutated gene. Rarely, there can be a gain in function e.g. a mutation in a growth factor receptor (FGFR3) that is constitutively active.

These types of mutation can also occur in non-coding regions of genomic DNA (the introns).

• The role of the introns is not understood—they are often naively assumed to be mostly ‘junk’ DNA with no role

• If the mutation occurs in a regulatory element such as a repressor or promoter, this can cause inappropriate down- or up-regulation of gene expression, respectively

• Mutations in splice sites may prevent the correct splicing of exons together in the processing of RNA, leading to the inclusion or exclusion of exons

• There is a strong possibility this will also cause frame-shift problems and premature stop signals.

• Genes consist of nucleic acid (DNA), which itself is a long polymer of nucleotides

• Genes are made up of exons and introns

• Exons code for the protein that the gene encodes

Exon sequence is highly conserved between individuals

Exon sequence is highly conserved between individuals

• Introns will be spliced out during processing to the mRNA

The length of the introns usually far outweighs the exons for any particular gene

The length of the introns usually far outweighs the exons for any particular gene

The exact function of the introns is not clear. The intron sequence is not well conserved between individuals.

The exact function of the introns is not clear. The intron sequence is not well conserved between individuals.

• Originally it was thought that, as proteins were quite complex molecules, the genetic material must be of equal or greater complexity, i.e. other proteins

• Experiments with pneumococcus disproved this

• Two types of Diplococcus pneumoniae (now called Streptococcus pneumoniae) used

Wild-type (‘smooth’ after its appearance under a microscope), which is virulent and kills mice

Wild-type (‘smooth’ after its appearance under a microscope), which is virulent and kills mice

Avirulent (‘rough’) mutant, which is harmless as it lacks the appropriate surface polysaccharide needed to infect cells

Avirulent (‘rough’) mutant, which is harmless as it lacks the appropriate surface polysaccharide needed to infect cells

Wild-type can be rendered avirulent by heat treatment, which is then harmless but remains smooth (‘smooth avirulent’)

Wild-type can be rendered avirulent by heat treatment, which is then harmless but remains smooth (‘smooth avirulent’)

• The first key experiment was performed by Griffith in 1928:1 If a mouse was injected with smooth avirulent + rough bacteria → dead mouse

• Bacteria isolated from the dead mouse were smooth and virulent

• Therefore, something in the smooth avirulent bacteria had enabled the mutant rough bacteria to produce the polysaccharide and become virulent

• To answer whether this something was protein or DNA, Avery2 conducted the following experiment in 1944:

• DNA was extracted from wild-type bacteria

• Inject mouse with mutant (rough) bacteria + wild-type (smooth) DNA → dead mouse

• However, if the DNA extracted from the wild-type bacteria was treated with:

With the protease trypsin → dead mouse

With the protease trypsin → dead mouse

• Hershey–Chase’s experiment (1952)3 using phage (which infect bacteria) gave further support to the findings of Griffith and Avery

• When a similar type of experiment was done with 32P labelled phage (i.e. with labelled DNA), 30% of progeny phage were labelled

• When the phage were 35S labelled (i.e. protein labelled), <1% of progeny were labelled

• This confirms Avery’s finding that DNA is the genetic material, not protein.

Some genes are expressed ubiquitously in cells at constant levels (often known as housekeeping genes). However, others can vary their expression dynamically.

• Control can be exerted by internal genetic signals or external factors such as hormones

• Control of expression can be reversible or permanent.

Transcription factors are the protein products of genes that control the expression of other genes.

• These tend to be long-term effects, including permanent changes that occur in cell differentiation

• These gene regulatory factors are enhancer proteins which have a DNA binding motif and a transcription activation motif. The most common type of protein is the helix-turn-helix

• Consists of two α-helices connected by a short sequence of amino acids that form the turn

• These are said to act in a trans manner as they can affect genes far away in the genome

• They act by recruiting other regulatory proteins expressed by the cell

These complexes bind to the gene and are thought to act by increasing the accessibility of the initiation site to RNA polymerase and/or exposing other regulatory sites. In this way, enhancers perturb the chromatin structure of a gene that they regulate (

These complexes bind to the gene and are thought to act by increasing the accessibility of the initiation site to RNA polymerase and/or exposing other regulatory sites. In this way, enhancers perturb the chromatin structure of a gene that they regulate ( p.62).

p.62).

One of the best examples of an external factor affecting gene expression is the action of steroid hormones.

• These effects can be transient or longer term, but are generally reversed when the hormone signal is removed

• These lipid-soluble hormones diffuse from the extracellular fluid into cells where they bind to receptor proteins

• These hormone-receptor complexes in turn diffuse into the nucleus where they bind to receptor elements in the DNA and either up- or down-regulate gene expression

• Hormones can also act via 2nd messenger systems to affect gene expression, e.g. there are cAMP-sensitive response elements

• The binding of a transcription factor to promoter elements upstream from the transcription start affects the rate at which the gene is transcribed

• Transcription factors can either increase or inhibit the transcription of genes

• These factors are known as enhancers and silencers, respectively

• Enhancers bind to promoter regions: the GC box, the CAAT box, and the TATA box

These three elements are within 100bp of the transcription start site

These three elements are within 100bp of the transcription start site

They are said to be cis acting, as they act on the gene immediately following the promoter region

They are said to be cis acting, as they act on the gene immediately following the promoter region

Transcription factors binding to the GC and CAAT boxes enhance transcription by increasing the basal activity of the TATA box

Transcription factors binding to the GC and CAAT boxes enhance transcription by increasing the basal activity of the TATA box

• Silencers have a negative effect on gene transcription.

NB Control of gene expression can also occur at the level of mRNA processing, translation, and mRNA stability (i.e. changes in breakdown rates relative to formation).

Most of the information about regulation of gene expression has been obtained from studies of the lac operon (Fig. 3.1) in bacteria.

• An operon is a group of genes with related functions which are under the control of a single promoter

• They are only found in prokaryotes

• The mRNA produced contains the coding sequence for all the proteins (i.e. it is polycistronic, compared to eukaryote mRNAs which are always monocistronic)

• Expression of the lac operon allows bacteria to use lactose as an energy source

• In the absence of lactose, the lac repressor protein binds to the operator and blocks expression

• When an inducer molecule is present (in this case, the metabolite of the sugar lactose, allolactose), it binds to the repressor protein and allosterically changes its shape

• The repressor protein no longer binds to the operator and so RNA polymerase can transcribe the genes involved in bacterial lactose metabolism

• This has been shown experimentally using the artificial substrate, IPTG

• The lac repressor protein has been studied by crystallography and its structure supports the proposed mechanism of action.

In order for a eukaryotic cell to make a new protein, a number of RNAs need to be transcribed in addition to the one for the protein itself, the messenger RNA (mRNA).

• These are transcribed from their genes by different isoforms of RNA polymerase

• Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (polymerase I)

• Transfer RNA (tRNA) (polymerase III)

• Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) (polymerase II)

• These are not translated into proteins, but are catalytically active in the RNA form.

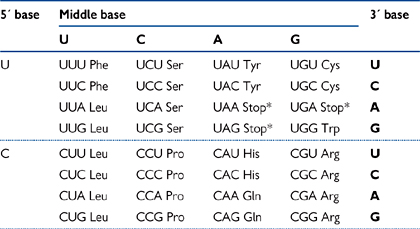

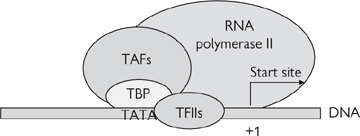

The first step in gene expression is the transcription of the gene of interest: this takes place in three stages—initiation (Fig. 3.2), elongation, and termination.

The first step is the binding of the TATA box-binding protein (TBP) and TBP-associated factors (TAFs, collectively known as TFIID) to the TATA box.

• This causes the sequential recruitment of other transcription factors for RNA polymerase II (TFIIs)—namely TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIIF

• This is followed by RNA polymerase II itself and, finally, TFIIE and TFIIH

• On completion of its assembly, the initiation complex (known as the basal transcription apparatus) unwinds a short stretch of the double helix to reveal the single-stranded DNA that it will transcribe and interacts with transcription factors which regulate the rate of transcription

• The rate of transcription initiation by the basal transcription apparatus is quite slow in the absence of enhancing transcription factors.

RNA polymerase II selects the correct ribonucleotide triphosphate and catalyses the formation of the phosphodiester bond.

• The RNA molecule does not require a primer and is synthesized in the 5′ → 3′ direction

Normal nucleotide base pairing rules apply, except uracil (U) is paired with adenine (A) when it occurs in the template

Normal nucleotide base pairing rules apply, except uracil (U) is paired with adenine (A) when it occurs in the template

• This process is repeated many times and the enzyme moves unidirectionally away from the promoter region along the DNA template

• The polymerase is completely processive, i.e. a single enzyme transcribes a complete RNA

• RNA polymerases do not have any proof-reading mechanism

• This lower level of fidelity is less important as RNA is not inherited (unlike DNA)

• Usually, many copies of RNA are made when a gene is expressed, so a few mistakes are unlikely to affect overall levels of protein synthesis.

As RNA polymerases are so processive, it is important that there are termination signals to indicate when the RNA transcription should stop.

• The simplest stop signal is a palindromic GC region immediately followed by a T-rich region

• The palindromic GC-rich region forms a hairpin structure in the RNA due to the base pairing

• The T-rich region causes an oligo(U) sequence immediately after the hairpin. This hairpin-oligo(U) complex is thought to destabilize the relatively weak association between the newly synthesized RNA and the DNA template

This leads to their dissociation, and that of the RNA polymerase II complex

This leads to their dissociation, and that of the RNA polymerase II complex

The DNA strands reform into a double helix

The DNA strands reform into a double helix

• There are also proteins that assist in terminating RNA transcription

• One such protein discovered in prokaryotes is the rho (Ρ) protein

• This binds to the newly made RNA at C-rich G-poor regions and scans along the RNA towards the RNA polymerase in an ATP-dependent manner

• When it catches up with the RNA polymerase, it breaks the DNA/RNA association and thus terminates transcription.

In both cases, the signal for termination lies in the newly formed RNA, not in the DNA template.

Fig. 3.2 Diagrammatic representation of the components of the basal initiation complex.

The RNA, as it is transcribed by RNA polymerase II, is known as the pre-mRNA and requires processing (Fig. 3.3).

• First, the pre-mRNA is capped

• This involves the addition of a G residue to the 5′ end of the pre-mRNA by a very unusual 5′-5′ triphosphate bond, which is then methylated on the N7 of the terminal G and possibly also on adjacent riboses

• The role of the cap is to protect the 5′ terminal of the mRNA against degradation and to improve ribosomal recognition for translation

• Second, a poly(A) tail is added (polyadenylation)

• The polyadenylation consensus sequence (AAUAAA) signals that the pre-mRNA should be cleaved 20 bases or so downstream by an endonuclease

• A poly(A) polymerase then adds the poly(A) tail, which can consist of hundreds of residues. Like the cap, the poly(A) tail is thought to enhance translation and improve mRNA stability

• Third, the pre-mRNA contains sequences for both the introns and the exons, whereas the mature mRNA only has those of the exons

• The introns are spliced out at specific recognition site at the ends of introns by spliceosomes. Spliceosomes consist of a number of snRNA molecules, associated protein called splicing factors, and the pre-mRNA being processed

The snRNA and protein complexes alone are known as small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs or ‘snurps’)

The snRNA and protein complexes alone are known as small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs or ‘snurps’)

• mRNA can also be edited, i.e. its base sequence changed

For example, the lipid and cholesterol transport protein apolipoprotein B exists in two forms—apo B-100 (formed in the liver) and apo-B 48 (small intestine)

For example, the lipid and cholesterol transport protein apolipoprotein B exists in two forms—apo B-100 (formed in the liver) and apo-B 48 (small intestine)

Apo B-48 is a truncated form of apo B-100, formed not by protein cleavage of the larger form, nor by alternative splicing, but by tissue-specific mRNA editing inserting a stop codon into the transcript.

Apo B-48 is a truncated form of apo B-100, formed not by protein cleavage of the larger form, nor by alternative splicing, but by tissue-specific mRNA editing inserting a stop codon into the transcript.

Fig. 3.3 Transcription, post-transcriptional processing, translation, and post-translational processing.

Once the pre-mRNA has been processed to form the mature mRNA, it leaves the nucleus through the pores in the nuclear membrane and moves to the cytoplasm where translation takes place (Fig. 3.4).

• Translation is carried out by ribosomes

• These are situated on the cytoplasmic face of rough ER (RER) for proteins that will be secreted, targeted to organelles, or inserted in the plasma membrane

• Proteins that will remain in the cytoplasm are synthesized on free cytoplasmic ribosomes

• Ribosomes consist of a 60S (large) and a 40S (small) subunit, giving the total 4200KDa 80S complex

• The subunits are ribonucleoproteins i.e. they are made up of a large number of proteins and one or more RNA molecules

The key reactive sites in ribosomes are made up almost entirely of RNA

The key reactive sites in ribosomes are made up almost entirely of RNA

The 60S subunit contains three RNAs: 5S, 5.8S, and 23S

The 60S subunit contains three RNAs: 5S, 5.8S, and 23S

• Protein synthesis begins at the amino terminus and runs through to the carboxyl terminus

• The mRNA is translated in a 5′ → 3′ direction

• The 40S subunit attaches to the cap at the 5′ end of the mRNA and scans along the mRNA looking for the start codon

Methionine (AUG) is always the first amino acid in eukaryotic proteins

Methionine (AUG) is always the first amino acid in eukaryotic proteins

As eukaryotic mRNA are monocistronic (i.e. only code for one protein), the most 5′ AUG in the mRNA is usually the protein start

As eukaryotic mRNA are monocistronic (i.e. only code for one protein), the most 5′ AUG in the mRNA is usually the protein start

Bound to the 40S subunit are initiation factor proteins (eIFs), GTP, and the Met-tRNAi (the specific tRNA for starting a new polypeptide chain)

Bound to the 40S subunit are initiation factor proteins (eIFs), GTP, and the Met-tRNAi (the specific tRNA for starting a new polypeptide chain)

When they find the initiation codon, the initiation factors dissociate and the 60S subunit is recruited

When they find the initiation codon, the initiation factors dissociate and the 60S subunit is recruited

• The 80S ribosome complex has three sites to which tRNAs can bind—the E, P, and A sites

The next tRNA, as specified by the mRNA, template binds to the A site

The next tRNA, as specified by the mRNA, template binds to the A site

A peptide bond is then formed between the two amino acids by peptidyl transferase

A peptide bond is then formed between the two amino acids by peptidyl transferase

The ribosome translocates along the RNA towards the 3′ end by one codon so that the amino acids formerly bound to the P and A sites are now bound to the E and P sites, respectively, driven by GTP and enzymes known as elongation factors

The ribosome translocates along the RNA towards the 3′ end by one codon so that the amino acids formerly bound to the P and A sites are now bound to the E and P sites, respectively, driven by GTP and enzymes known as elongation factors

The newly liberated A site can accept the next tRNA

The newly liberated A site can accept the next tRNA

This sequence is repeated many times until the stop codon is reached in the mRNA template. There are no tRNAs with anticodons complementary to the codons coding for the stop signal. Instead, the codons are recognized by the release factor (eRF1), which causes dissociation of the ribosome from the completed polypeptide chain

This sequence is repeated many times until the stop codon is reached in the mRNA template. There are no tRNAs with anticodons complementary to the codons coding for the stop signal. Instead, the codons are recognized by the release factor (eRF1), which causes dissociation of the ribosome from the completed polypeptide chain

• Prokaryotic ribosomes and translation processes are slightly different from eukaryotic ones. These differences have been exploited therapeutically by antibiotics ( OHCM8 p.378) that inhibit protein synthesis e.g. tetracycline, aminoglycoside (e.g. streptomycin) and macrolide (e.g. erythromycin) antibiotics (

OHCM8 p.378) that inhibit protein synthesis e.g. tetracycline, aminoglycoside (e.g. streptomycin) and macrolide (e.g. erythromycin) antibiotics ( OHPDT2 pp.398–402).

OHPDT2 pp.398–402).

Proteins synthesized by ribosomes of the rough ER will either be inserted into the RER membrane or enter the RER lumen.

• For the majority of secreted proteins, there is a signal sequence that allows the protein to enter the RER lumen as it is synthesized

• This signal sequence is usually cleaved during subsequent protein processing.

For membrane proteins, there is also thought to be some sort of signal sequence that allows the N terminal to cross the membrane in the case of type II membrane proteins or the first transmembrane region to enter the membrane in the case of type I proteins.

Fig. 3.4 Representation of the way in which genetic information is translated into protein.

The human genome contains approximately 3.2×109 base pairs.

• First draft of the complete sequence was released in early 2001

• Predicted to be around 30 000 genes (open reading frames (ORFs) coding for proteins)

• Exons make up only 1.5% of the total DNA

• The rest are regulatory elements and introns (non-coding regions)

• The average length of an exon is 145 base pairs, with 8.8 exons per gene.

DNA sequences can be present in the genome in different amounts.

• Single-copy DNA represent almost half of the human genome. Only a small fraction of this codes for proteins, the rest being unique intron and regulatory sequence

• Moderately repeated DNA is that which is repeated from a few to a thousand times

• The sequences vary from a hundred and many thousand base pairs

• Makes up about 15% of the human genome

• Highly repeated DNA is made up of short sequences (usually <20 nucleotides) repeated millions of times

• Inverted repeat DNA are a structural motif of DNA, with an average length of 200 base pairs. In humans, they form hairpin structures

• Inverted repeats can be up to 1000 base pairs

• These can be repeated 1000 or more times per cell.

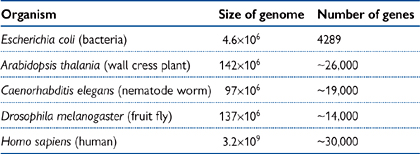

As can be seen from Table 3.2, the size of the genome does not necessarily correlate to the number of ORFs.

• For example, wall cress (Arabidopsis) has a genome of very similar size to the fruit fly Drosophila, but almost double the number of genes

• The human genome is almost 103-fold larger than that of E. coli, but has nearly one tenth the number of genes.

The relatively large size of the human genome is due to the large amount of non-coding regions (introns).

• The exact function of introns is not known

• They are often regarded as ‘junk’ DNA

• The converse argument is that they must have a function as there is a large metabolic penalty to maintain them

• Much of the non-coding sequence consists of highly repeated sequences (approximately 53% of the total genome)

• Prokaryotes do not have introns to the same extent, hence their smaller genomes.

Table 3.2 Comparison of genome size with number of genes for various organisms

The technique of gene cloning has allowed individual gene products to be studied in detail, both at a functional and structural level.

• DNA cloning involves the amplification of a particular DNA fragment

• If the sequence is known, it can be amplified using gene-specific primers by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) described on next page.

• If part of the sequence is known, a labelled DNA probe to this fragment can be used to identify the gene

• If there is an antibody to the protein, cells transfected with the gene can be identified by screening

• If the function of the gene is known, it can be identified by testing cells transfected with the gene for that particular response

• The usual starting material for these kind of studies is a cDNA library

• This is constructed by isolating all the mRNA from a particular cell that is known to express the protein of interest

• This is converted into cDNA using the enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT)

The primer for the RT reaction is often an 15–18mer of poly(T) that hybridizes to the poly(A) tail of the mRNA

The primer for the RT reaction is often an 15–18mer of poly(T) that hybridizes to the poly(A) tail of the mRNA

The cDNA is then cloned into a vector using restriction enzymes and amplified in E. coli

The cDNA is then cloned into a vector using restriction enzymes and amplified in E. coli

These clones can then be screened to identify which of them contains the gene of interest (by the methods above)

These clones can then be screened to identify which of them contains the gene of interest (by the methods above)

To represent all of the mRNA that was present in the cell, the cDNA library needs to have many thousands of clones.

To represent all of the mRNA that was present in the cell, the cDNA library needs to have many thousands of clones.

Restriction enzymes (REs) and vectors are essential tools for DNA cloning.

• Isolated from bacteria, REs cut DNA at specific sequence of four or more bases

• Can produce either 3′ or 5′ overhangs (‘sticky ends’) which can be joined by DNA ligase to a compatible DNA fragment that has a complementary overhang, or ‘blunt ends’ which have no overhang and can be ligated to any other blunt end

• The joining of two unrelated DNA fragments results in a recombinant DNA molecule

• Vectors (or replicons) are carrier DNA that can independently replicate in a host organism to produce multiple copies of itself

• Commonly used vectors are plasmids (replicate in E. coli). Plasmids need to have certain features: an origin of replication, gene coding for antibiotic resistance for selection of transformed cells, multiple cloning site (MCS: a number of unique RE sites close together that allow the insertion of the gene of interest), promoter(s) flanking the MCS to allow the cloned gene to be expressed

• Other types of vector include bacteriophages, cosmids, bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs), and yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs)

Cosmids, BACs, and YACs have the advantage of being able to take larger inserts than plasmids and bacteriophages

Cosmids, BACs, and YACs have the advantage of being able to take larger inserts than plasmids and bacteriophages

YACs have been useful in mapping eukaryotic genes which can be up to several million base pairs in length.

YACs have been useful in mapping eukaryotic genes which can be up to several million base pairs in length.

If the sequence of a gene is known, it can be amplified using PCR.

• Primers (usually approximately 25 bases long) are made which flank the region of the gene to be amplified

• The template and the primers are heated to 95°C to denature them

• The temperature is reduced to one that allows the primers, which are in vast excess, to anneal to their complementary regions on the template. Usually the primers are designed for this temperature (known as the melting temperature) to be approximately 60°C

• Increasing the temperature to 72°C allows the DNA polymerase to extend the primer at a rate of approximately 1000bp/min

• This process is repeated usually around 30 times. As the target DNA is amplified exponentially, this gives 230 or over 1×109 copies

• The PCR product is visualized by electrophoresis on an agarose gel

• Agarose is a carbohydrate isolated from seaweed

• DNA migrates through the agarose gel when an electrical current is applied, moving towards the anode (as DNA is negatively charged due to the phosphates). The distance DNA moves is dependent on its size–the smaller the DNA, the faster it migrates

• DNA can be visualized by staining with ethidium bromide, which fluoresces under UV light

• Two developments made PCR a much more feasible and routine technique:

• The isolation and purification of thermostable DNA polymerase from bacteria that have evolved to live in hot springs and geothermal vents in the ocean. The DNA polymerase is able to withstand repeated periods of temperature of 95°C and has maximal processivity at 72°C

• The manufacture of thermal cyclers—programmable heating blocks which can rapidly change temperature

• PCR is often used in tandem with creating cDNA to look for gene expression in a particular tissue—a technique known as RT-PCR

• In combination with sequencing, RT-PCR can be used as a diagnostic tool for diseases involving known point mutations

• These molecular techniques are also highly valuable in a research environment.

There are a number of techniques that allow the recognition of either nucleic acid or protein from samples:

• Northern blotting uses a labelled antisense DNA probe to look for copies of mRNA which have been separated by size on a gel and blotted onto a filter. The probe will hybridize to its complementary message allowing determination of the size and quantity of the mRNA transcript in the sample

• Southern blotting is similar to northern blotting except that the template is restriction enzyme-treated DNA rather than mRNA

• Useful in genotyping, e.g. gene knock-out animals

• Western blotting involves running protein samples on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and transferring them onto a filter

• The filter is then probed using an antibody to the protein(s) of interest

• The antibody binding can be quantified using an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g. anti IgG-horseradish peroxidase) that can be assayed colorimetrically.

Two different techniques of DNA sequencing were developed in the late 1970s—the Maxim–Gilbert and the Sanger methods. The Sanger method is the one commonly used today, and has been automated for high through-put sequencing projects such as the Human Genome Project.

• Double-stranded DNA is cut into fragments and the end of one strand labelled with a 32P-dNTP using part of E. coli DNA polymerase I (the Klenow fragment)

• The DNA is chemically treated in separate reactions so as to induce it to break into fragments at each of one of the bases, using conditions that only cause a couple of breaks per molecule

• Statistically, therefore, one should get all the size fragments that end with such a base

• Running these on a polyacrylamide gel will separate these fragments and allow the sequence to be read from an autoradiograph (photograph on X-ray film).

• Based on the random interruption of the synthesis of a DNA strand in a reaction analogous to the PCR

• Four separate reactions are run, each with dNTPs and a single ddNTP species

• ddNTP is a dideoxynucleoside triphosphate, with an H on C3 of the sugar moiety (rather than the OH in a dNTP)

• These can be incorporated into DNA by a polymerase but not extended due to the lack of a 3′OH for the next nucleotide

• The dNTPs and ddNTP are at such concentrations that the dNTP is incorporated randomly at every position

• The ddNTP is labelled so that the differently sized fragments produced can be visualized

• Traditionally, 32P-ddNTPs were used, but now it is more common to use ddNTPs that are labelled with fluorescent molecules, a different colour for each base

• The reactions are run on polyacrylamide gels to separate the fragments. Either an autoradiograph is taken (for 32P-ddNTPs) of the gel (Fig. 3.5), or it is read with a laser in an automated sequencer for the more commonly used fluorescent ddNTP method (Fig. 3.6)

• Direct sequencing of PCR products from patient tissue has allowed the relatively easy diagnosis of genetic diseases

• One or more small regions of genomic DNA can be amplified by PCR

• These fragment(s) can be sequenced directly to determine if a mutation exists in the region(s) of the gene amplified

• Has the advantage of being quick, accurate, and relatively cheap

• Has been used for diagnosis of, e.g. haemophilia, cystic fibrosis.

Fig. 3.5 Photograph of an actual sequencing ladder.

Fig. 3.6 Example of DNA sequencing trace using fluorescent ddNTP technique. In original, the trace for each base was a different colour. (Image courtesy of David Meredith).

With the sequencing of the human genome, the concepts of molecular and medical genetics are coming closer together. The distinction is purely pragmatic—any molecular genetics which have been identified to cause human disease are then called medical genetics. The specialty of medical genetics serves to investigate patients with diseases which may have a genetic basis and then to counsel them on the implications of this for their own futures and that of any actual or potential offspring. At the moment, the prospect of treating genetic diseases by replacement of defective genes by gene therapy remains a dream, although there has been some encouraging results from attempts to treat inherited immuno-deficiencies by this route.

Most diseases represent a combination of genetic and environmental influences and the relative contribution of either varies. A genetic disease is usually taken to be one in which the disease is always manifest in ‘standard’ environmental conditions if the genetic abnormality is present. Some genetic diseases have complete expression whatever the environment (e.g. trisomy 21 producing Down’s syndrome  OHCS8 pp.152–153), whilst others may only be revealed in environments which are now ‘normal’ but would not have been in the recent evolutionary past, e.g. certain types of congenital hyperlipidaemia (

OHCS8 pp.152–153), whilst others may only be revealed in environments which are now ‘normal’ but would not have been in the recent evolutionary past, e.g. certain types of congenital hyperlipidaemia ( OHCM8 pp.704–5) which are now manifest as ischaemic heart disease in populations with a higher-calorie, higher-fat diet. Diseases with an overwhelming environmental factor and a minor genetic predisposition would not usually be regarded as genetic disease, e.g. development of lung cancer (

OHCM8 pp.704–5) which are now manifest as ischaemic heart disease in populations with a higher-calorie, higher-fat diet. Diseases with an overwhelming environmental factor and a minor genetic predisposition would not usually be regarded as genetic disease, e.g. development of lung cancer ( OHCM8 pp.170, 171) in cigarette smokers.

OHCM8 pp.170, 171) in cigarette smokers.

A number of different genetic mechanisms can influence the manifestation of genetic diseases and their modes of inheritance.

• The simplest example of this is a mutation in a gene which codes for a structural protein which leads to either no production of the protein or a protein with no function. A specific example of this is Duchenne muscular dystrophy ( OHCM8 p.514) (

OHCM8 p.514) ( p.350) where a deletion mutation in the dystrophin gene leads to absence of this protein which is essential for the maintenance of the myocyte membrane during muscle contraction

p.350) where a deletion mutation in the dystrophin gene leads to absence of this protein which is essential for the maintenance of the myocyte membrane during muscle contraction

• There is more pathogenic complexity when the abnormal gene codes for a protein which has a regulatory role e.g. the retinoblastoma gene and hereditary retinoblastoma

• Single gene abnormalities may be transmitted by autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked modes of inheritance

• Autosomal dominant—the abnormal gene has an effect, i.e. it is penetrant, even when a normal gene is present on the other allele of the homologous chromosome

• Autosomal recessive—the abnormal gene does not have an effect unless the allele on the homologous chromosome has the same abnormality or has been deleted or silenced by hypermethylation

• X-linked—the sex chromosomes present a special case because there is incomplete homology between X and Y chromosomes with the X chromosome having a substantial amount of additional genomic material. If an abnormal gene occurs in this region, then there is no corresponding normal allele on the Y chromosome to counteract it if the abnormal gene would otherwise have a recessive model of penetrance.

• Deletion of bases within a coding region of a gene leading to misreading of all the bases within that gene after that point causing either no production of the gene protein product or an abnormally functioning protein, e.g. dystrophin in Duchenne muscular dystrophy ( OHCM8 pp.514, 350)

OHCM8 pp.514, 350)

• Insertion of bases within a coding region of a gene leading to misreading of all the bases in that gene after that point causing an abnormal protein product e.g. the factor VIII gene in some types of haemophilia A ( OHCM8 p.338)

OHCM8 p.338)

• Point mutation of a base within a coding region of a gene, i.e. substitution of one base for a different base, leading to coding of an abnormal protein e.g. sickle cell anaemia ( OHCM8 p.334)

OHCM8 p.334)

• Fusion of two genes to produce an abnormal product, e.g. Lepore haemoglobins

• Deletion, insertion, or point mutation within a non-coding (i.e. promoter or enhancer) region of a gene, which can interfere with the binding of transcription factors to this region and cause loss or reduced transcription of the coding region of the gene, e.g. some hereditary haemolytic anaemias ( OHCM8 p.332).

OHCM8 p.332).

Genetic diseases may also be caused by chromosomal abnormalities and these usually have a more complex phenotype since a much larger amount of genetic material will be involved, e.g. in trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome), the phenotype includes learning difficulties, premature development of cataracts and dementia, susceptibility to certain bacterial infections, congenital heart defects, and a predisposition to leukaemia.

• Trisomy—occurs when a pair of homologous chromosomes fail to separate at meiosis, e.g. trisomy 18—Edward’s syndrome ( OHCS8 p.642)

OHCS8 p.642)

• Monosomy—occurs as the other daughter cell of a meiotic division which produced a trisomic cell, usually causes a non-viable fetus which spontaneously aborts during the first trimester

• Deletion—loss of a portion of a chromosome, the deleted portion will be lost at the next mitotic division, there may not be much phenotypic effect if the homologous chromosome is intact

• Ring chromosome—a special case of deletion where material is lost from each end of a chromosome and the new ends join together to form a ring, this causes many problems at mitosis

• Inversion—two breakages occur within a chromosome and the central segment rotates before rejoining

• Isochromosome—occurs when one arm of a chromosome is lost (e.g. the short arm) and the other arm duplicates to replace it (e.g. the long arm) producing genetic monosomy of the lost arm and trisomy of the duplicated arm

• Translocation—a breakage occurs and material is attached to a different chromosome. Sometimes material is exchanged between two non-homologous chromosomes, which may produce a normal phenotype in that individual but with major abnormalities in gametes if only one of the translocated chromosomes segregates into an individual cell.

These are a unique group of diseases that are characterized by amplification of a specific trinucleotide sequence in a gene. Strictly, they could be classified as insertions in coding or non-coding regions of the affected gene but they have special properties that merit separate discussion.

• A specific trinucleotide sequence, e.g. CGG in fragile X syndrome, ( OHCS8 p.648) which normally has several repeats in a gene is amplified to have many hundreds or thousands of repeats

OHCS8 p.648) which normally has several repeats in a gene is amplified to have many hundreds or thousands of repeats

• This amplification may occur either during spermatogenesis (e.g. Huntington’s chorea  OHCM8 p.716) or oocytogenesis (e.g. fragile X syndrome) depending on each specific disease

OHCM8 p.716) or oocytogenesis (e.g. fragile X syndrome) depending on each specific disease

• In non-coding regions, the amplified repeat sequence interferes with transcription and can induce methylation, and thus non-function, of the whole promoter region

• In coding regions, the amplified repeat sequence produces proteins with abnormal functions, e.g. a form of huntingtin in Huntington’s chorea that abnormally inactivates proteins that are normally associated with it. The diseases present earlier in life, and with a more severe phenotype, with successive generations, because of the amplification which occurs during gametogenesis. This is called anticipation.

Most human disease is not due to single gene or chromosomal abnormalities. Rather, there is a complex interaction between a large number of genes and the individual’s environment. The human genome has been subject to selections by evolutionary pressure over millions of years, but the environment in the past thousand years has been changing much more rapidly than any genetic changes. This has led to possible imbalances that may lead to the development of disease, an area which is investigated in evolutionary medicine. All these factors mean that the genetic investigation of most human diseases is directed towards finding a set of genes and environmental factors which combine to produce the disease. This requires a different set of techniques from those used in defining single gene or chromosomal abnormalities.

A genetic polymorphism is a variation between the genomes in individuals that does not appear to produce a specific deleterious phenotype, so it is not classified as a single gene inheritable disorder. This is a slightly slippery concept because, the majority of human disease will be a result of interaction of such genetic variability with the environment. Polymorphisms have been defined by whatever genetic analysis technique has been available to detect them:

• Restriction fragment length polymorphisms—the use of restriction enzymes that cleave DNA at specific sites to produce fragments the lengths of which vary between individuals.

• Short tandem repeat polymorphisms—the genome contains many stretches of di-, tri-, or of variable length and enzymes can be used to cleave these and the fragment length examined. This is the basis of genetic fingerprinting used in criminal investigations and paternity suits.

• Single nucleotide polymorphisms—restriction fragment length poly-morphisms are just surrogate measures of single nucleotide polymorphisms and the technology is now available, through high through-put sequencing or oligonucleotide microarrays, to detect these directly.

It seems that any two individuals will have around 2.5 million single nucleotide polymorphisms between them, 1 in 1300 nucleotides, so it is a large bioinformatics problem to be able to find the polymorphisms which are important in the pathogenesis of a specific disease.

Linkage is the statistical association between any genetic marker and a particular phenotype, which is usually a specific disease. If genetic markers, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms, are examined in a large population of individuals and it is known which individuals have or do not have the disease, then statistical analyses can be made to establish the strength of linkage between the marker and the disease. If the association is very strong, this suggests that the marker is very close to, or actually in, the region of DNA that codes for proteins involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. This task may be made easier by using populations with a relatively restricted gene pool and long-known pedigrees, which are found in geographically or socially insular communities such as the Amish in North America. The single genes involved in cystic fibrosis and Huntington’s chorea were discovered using genetic linkage studies. Defining polygenic diseases using linkage studies is much more difficult.

Medical genetics could potentially be well employed in improving the therapeutic benefits of administered drugs. Two inter-related terms are applied to describe studies in this area: pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics, although there is considerable confusion (even among scientists) as to the definition of both.

The term ‘pharmacogenetics’ was coined more than 50 years ago and relates to the study of how an individual gene might affect the body’s response to a drug. Historically, this term has been applied specifically to describe the study of polymorphisms that affect enzymes involved in drug metabolism, with a bearing on the potential toxicity of a given drug. Identifying patients with particular polymorphisms, prior to drug administration, could identify those at risk of toxic side-effects from a particular class of drug and would help physicians modify the treatment regimen accordingly. Much of the work to date has centred on polymorphisms among P450 enzymes, which are involved in the metabolism of many drugs in the liver.

Pharmacogenomics is a more recent term that relates to how the whole genome affects the body’s response to a drug. This is a far broader discipline, because it embraces not only the impact of the gene that, for example, encodes for a target protein (enzyme or receptor), but also the array of genes that might determine an individual’s ability to absorb a drug, the ultimate distribution of that drug, and its clearance through metabolism and excretion. Ultimately, it is hoped that knowledge of a patient’s genome will facilitate ‘individualized medicines’ that will be tailored to a particular patient’s genetic make-up. This could help doctors to choose the best drug at the optimal dose for any given patient while avoiding, for example, adverse reactions determined by genetic predisposition. Furthermore, pharmacogenomics will help in identifying new gene product targets for drug intervention. Ethics aside, the tools are now available to us, in the post-genomic era, to take this particular aspect of medical genetics forward.