) and by small amounts of sulphur (S) in the amino acids methionine and cysteine, and in thioester bonds

) and by small amounts of sulphur (S) in the amino acids methionine and cysteine, and in thioester bondsAmino acids and the peptide bond

Principles of protein structure

Concepts of biochemical reactions and enzymes

Structure and function of enzymes

Membrane transporter proteins 24

Fatty acids and triacylglycerides 28

Cholesterol and its derivatives 32

Carbohydrates as metabolic precursors 38

Carbohydrates as conjugates 40

The organization of cell membranes

Pharmacological modulation of cell function

Concentration–response relationship 80

Absorption, distribution, and clearance of drugs 86

Desensitization, tachyphylaxis, tolerance, and drug resistance 92

There are four major chemical components to biological life—carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N).

• O, C, and H form the bulk of the dry mass—65%, 18%, and 9% respectively of the human body (e.g. carbohydrates, simple lipids, hydrocarbons)

• N represents 4% and is an essential part of life (nucleotides, amino acids, amino sugars, complex lipids)

• They are supplemented by phosphorus (P) in the form of phosphate ( ) and by small amounts of sulphur (S) in the amino acids methionine and cysteine, and in thioester bonds

) and by small amounts of sulphur (S) in the amino acids methionine and cysteine, and in thioester bonds

• There are also a number of essential trace elements (e.g. Mn, Zn, Co, Cu, I, Cr, Se, Mo) that are essential co-factors for enzymes.

Note that all biological molecules (biomolecules) must obey the basic rules of chemistry!

One important such example for C atoms is stereochemistry:

• Three-dimensional (3D) structures in biomolecules are often key to their function

• Carbon atoms can have four different groups attached to them (i.e. be tetrahedral)

• Under these conditions, the C atom is said to be chiral—it has two mirror-image forms (D- and L-) that cannot be superimposed (see Fig. 1.1)

• Nature has favoured certain stereoisomers:

• For example, naturally occurring mammalian amino acids are always in the L-form, whereas carbohydrates are always in the D-form

• The stereoisomers of therapeutic compounds may have very different effects

For example, one stereoisomer of the drug thalidomide (which is a racemic mix), used briefly in the late 1950s to relieve symptoms of morning sickness in pregnancy, caused developmental defects in approximately 12 000 babies.

For example, one stereoisomer of the drug thalidomide (which is a racemic mix), used briefly in the late 1950s to relieve symptoms of morning sickness in pregnancy, caused developmental defects in approximately 12 000 babies.

Roughly speaking, biomolecules can be divided up into two groups: small and large (macromolecules).

• Small: relative molecular mass (Mr) <1000 (mostly under 400)

• Intermediates of metabolic pathways (metabolites), and/or

• Components of larger molecules

• Macromolecules: Mr >1000, up to millions

• Usually comprise of small biomolecule building blocks, for example:

Proteins (made up of amino acids)

Proteins (made up of amino acids)

DNA, RNA (nucleotides, themselves sugars, bases, and phosphate)

DNA, RNA (nucleotides, themselves sugars, bases, and phosphate)

• Macromolecules can contain more than one type of building block; for example, glycoproteins (amino acids and sugars).

When smaller molecules are to be combined into larger ones, often the smaller molecules are activated in some way before the joining reaction takes place. This is because firstly, often the activation will allow an otherwise energetically unfavourable reaction to take place and, secondly, it may well influence the reaction that takes place to ensure that the correct product is formed.

There are four basic types of macromolecule in cells:

• 1 Proteins—probably have one of the broadest range of functions in the body of any of the macromolecules. For example:

• Enzymes (biological catalysts)

• Membrane transporters (channels, carriers, pumps)

• Signalling molecules, e.g. hormones

• 2 Lipids—lipid molecules do not polymerize, but can associate non-covalently in large numbers

• Major component of cell membranes (plasma and organelle)

• Signalling (intracellular, hormone)

• Insulation (electrical in nerves, thermal)

• Component of other macromolecules (e.g. lipoproteins, glycolipids)

• 3 Carbohydrates (polysaccharides)—also have a diverse range of functions in the body, including:

• Structural (connective tissue)

• Cell surface receptors (short chains linked to lipids and proteins)

• Source of building blocks for other molecules (e.g. conversion to fat, amino acids, nucleic acids)

• 4 Nucleic acids (DNA/RNA)—transfer of genetic information from generation to generation (DNA) and for determining the order of amino acids in proteins (RNA).

Proteins have a wide range of biological functions, determined ultimately by their 3D structures (in turn determined by primary sequence) and potentially by higher levels of organization (i.e. multi-subunit complexes).

Proteins fall into a number of functional types.

• Can be extracellular (‘fibrous’), e.g. in bone (collagen), skin, hair (keratin)

• May use disulphide bonds to stabilize structure → strength

• Intracellular structural proteins e.g. cytoskeletal proteins such as actin, fibrin (blood clots).

Describes most non-structural proteins.

• Generally compact due to folding of polypeptide chain

• Usually bind other molecules (ligands), e.g. haemoglobin and O2, antibody and epitope, ferritin and iron

• Binding is specific and involves a particular part of the protein (binding site)

Can be tight (high affinity) or loose (low affinity) or anywhere in between

Can be tight (high affinity) or loose (low affinity) or anywhere in between

• Ligand binding can alter the function of the protein.

Enzymes are a specific type of globular protein.

• Bind substrate(s) and convert into product(s) (reactants)

• Enzymes are catalysts, i.e. are chemically identical before and after the reaction they catalyse

• Enzymes do not change reaction equilibrium, but increase the rate at which equilibrium is reached

• This is achieved by lowering the reaction activation energy.

• Integral membrane proteins, e.g. transporters, receptors

• Generally, compact globular proteins

• Have hydrophobic domains in the membrane lipid and hydrophilic domains in the cytoplasm/extracellular fluid

• Attached by covalent bonds to membrane elements, e.g. phospholipid head group.

These are proteins which affect the activity of other proteins, for example:

• Protein kinases (PKs), which phosphorylate proteins and affect their function e.g. PKA, PKC, tyrosine kinase

• Calmodulin, a Ca2+ binding protein, can be part of multi-subunit enzyme complexes and regulate their activity.

Amino acids are the building blocks from which proteins are formed, by the joining of these simple subunits into polymers (Table 1.1).

All amino acids have the same basic structure (Fig. 1.2):

Fig. 1.2 Basic structure of amino acids; R is the side-chain.

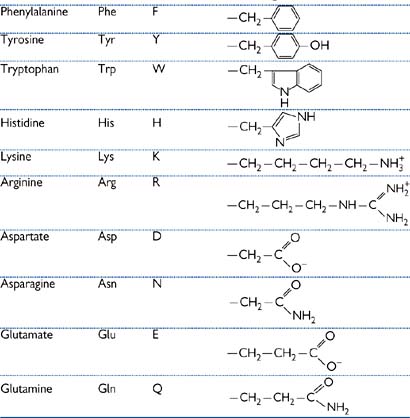

There are 20 common side-chains (R) in the amino acids that are found in mammalian proteins, and they fall into five categories:

1. Hydrophilic, e.g. glycine, alanine

2. Hydrophobic, e.g. phenylalanine

4. Acidic—aspartate, glutamate

• Cysteine and methionine contain sulphur

• The amino group of the side-chain of arginine and lysine has a pK of ~14, so is always positively charged under physiological conditions

• The carboxyl group of the side-chain of aspartate and glutamate has a pK of ~4, so is always negatively charged under physiological conditions

• Histidine side-chain has a pK of ~6 so can be either protonated (basic) or unprotonated (neutral) under physiological conditions

• Proline is known as a ‘structural’ amino acid as it puts a kink in polypeptide chains

• Glycine also allows flexibility in polypeptide chains due to the small size of its R group (i.e. a proton).

All the amino acids in mammalian proteins are the L stereoisomer.

• Bacteria make use of D-isomers

• Some antibiotics mimic D-amino acid and thus interfere with bacterial metabolism.

Amino acids are joined together in polypeptides by peptide bonds.

• Methionine is the starting amino acid of all proteins

• The peptide bond (–CO–NH–) is formed by a condensation reaction

• The peptide bond is planar and rigid (trans configuration), with no rotation around C–N bond

• Rotation around Cα–C and N–Cα bonds allows polypeptide chains to form 3D shape of proteins.

Protein function is determined from the primary amino acid sequence.

• The order of the amino acids will give the protein its shape

• The 3D shape of the protein is essential to its function, e.g. the shape of the substrate binding site of an enzyme

• this includes the position of the R groups, which is determined by the stereoisomer (L versus D).

Proteins have four levels of organization:

1. Primary—the order of the amino acids, e.g. Gly-Ala-Val

2. Secondary—the local interactions of the amino acids in the polypeptide chain. A number of forces are responsible for stabilizing the secondary structure of a protein, all non-covalent except for disulphide bonds

• The weakest interactions, also known as London forces

• Non-covalent; occurs between electronegative atoms (N or O) and an electropositive proton, e.g. =N…NH=, =N…HO–, C=O…HN=

• Interactions between groups of hydrophobic amino acids to reduce the amount of water associated with them and thus to increase thermodynamic stability of structure

• Strong driving force for globular protein formation

• Can also occur between hydrophilic amino acids in non-aqueous surroundings

• Between R groups of oppositely charged amino acids, e.g. arginine—glutamate, aspartate—lysine

• The only covalent bonding involved in protein structure

• Occur between the –SH groups of cysteines, to give –S–S– bonds These bonds can be broken by denaturing the protein, for example with heat or solvents. Denaturation can be reversible or irreversible.

These interactions allow the formation of regions of local structure within the protein, such as:

• α-helix (Fig. 1.3)

• Most stable of several possible helical structures which amino acids can adopt due to least strain on the inter-amino acid hydrogen bonding

• R groups point outwards from the helix. Usual form protein adopts when crossing lipid bilayers

• Stabilized by hydrogen bonds between every fourth peptide bond; the peptide bonds are adjacent in 3D space (periodicity of helix = 3.6 residues)

• β-sheet (Fig. 1.3)

• Polypeptide chain is in a fully extended conformation

• Can run parallel or anti-parallel

• Stabilized by hydrogen bonds between peptide bonds of adjacent polypeptide chains

• Loop/turn or β-turn (Fig. 1.3)

• Region where polypeptide chain makes a 180° change in direction, often at surface of globular proteins

• Stabilized by hydrogen bonds between residues 1 and 4 of this four-amino acid structure. Residues 2 and 3 are at the end of the loop and are often Pro or Gly, and do not contribute stabilizing bonds.

Fig. 1.3 Diagram of the structure of staphylococcal nuclease protein.

3. Tertiary—the overall structures formed by a polypeptide chain

• Also known as supersecondary structure

• Describes the overall arrangement of the regions of secondary protein structure

• Certain structural domains may be identified whose function is known, e.g. ATP binding domain

• Families of functionally related proteins may have similar tertiary structure. For example, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins have two domains, each of six membrane-spanning (α helical) regions and an ATP-binding site.

4. Quaternary—the interaction of a number of polypeptide chains to form a multimeric protein complex

• Many proteins are made up of more than one subunit, with the two or more polypeptide chains held together usually by the weak non-covalent interactions previously described

• The resulting oligomers can be either homo-oligomers (made up of a number of identical subunits) or hetero-oligomers (made up of different subunits).

Fig. 1.4 Computer-generated diagrams of (a) myoglobin and (b) haemoglobin.

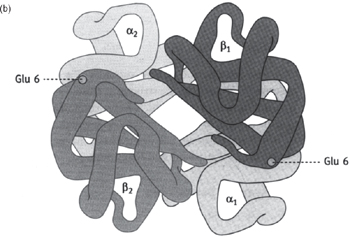

Two of the best studied and understood proteins are the monomeric myoglobin and the hetero-tetrameric haemoglobin (see Fig. 1.4)

• 3D structures solved by X-ray crystallography in the late 1950s/early 1960s1,2

• Myoglobin has a single polypeptide chain with a haem group non-covalently associated (an organic group attached to a protein is known as a prosthetic group)

• Binds O2 with a simple hyperbolic affinity curve

• Haemoglobin has four polypeptide chains (α2β2 in adults), each with a haem group and very similar to myoglobin

• O2 affinity curve is sigmoidal due to cooperation between the four O2 binding sites. Binding of the first O2 causes an allosteric change in the protein shape that makes the binding of the next O2 easier, and so on until all four sites are occupied. See Figs 6.17, 6.18, p.391.

Proteins can also be modified after synthesis.

• Post-translational modification

• Disulphide bonding—as described previously

• Cross-linking—formation of covalent cross-links between individual molecules

• Peptidolysis—enzymic removal of part of the protein after synthesis

• Attachment of non-peptidic moieties

• Glycosylation—addition of carbohydrate groups

• Phosphorylation—addition of a phosphate group to specific residue(s) of a protein, e.g. serine, tyrosine

• Adenylation—addition of an AMP group to a protein

• Farnesylation—proteins can be attached to an unsaturated C15 hydrocarbon group (known as a farnesyl anchor) which inserts into the plasma membrane.

These modifications can have effects on the functioning of the protein, affecting, for example:

• Phosphorylation is a common way by which protein function is modified, for example, turning of an enzyme on or off with PKA. This is an example of one protein (PKA) regulating the function of others

• Molecules conjugated to proteins can act as signals to the intra-cellular sorting and targeting machinery, e.g. phosphorylation can affect targeting

• Glycosylation levels can regulate the half-life of proteins in the circulation, for example, by affecting the rate at which they are taken up and degraded by liver cells

• Labelling of proteins with the 74-amino acid protein ubiquitin marks them for breakdown by proteosomes

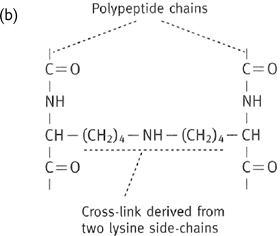

• For example, cross-linking of individual molecules in collagen greatly increases the strength of the fibril.

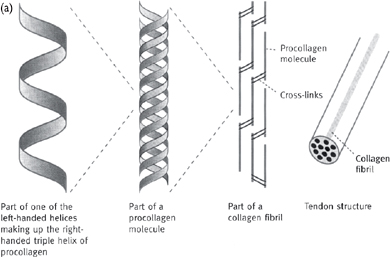

• Collagen is a structural fibrous protein of tendons and ligaments; also the protein component onto which minerals are deposited to form bone

• There are 13 types of collagen reported to date, with type I making up 90% of the collagen found in most mammals (and up to a third of the total protein in humans)

• Type I collagen is made up of three chains, two α1 and one α2 in a triple helix (Fig. 1.5)

• Each individual chain is a left-handed helix formed from a repeating amino acid sequence: —gly—pro—X— and —gly—X—OHpro— which occur >100 times each, accounting for ≈60% of the molecule

Only gly has a small enough R group to be at the centre of such a triple helical structure

Only gly has a small enough R group to be at the centre of such a triple helical structure

Collagen contains two unusual amino acids—hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine

Collagen contains two unusual amino acids—hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine

Formed by post-translational enzymatic modification

Formed by post-translational enzymatic modification

• These chains form a right-handed triple helix (tropocollagen molecule). The triple helix is stabilized by inter-chain hydrogen bonding between the peptidyl amino and carbonyl groups of the glycine and the hydroxyl groups of hydroxyproline

• Tropocollagen molecules form bundles of parallel fibres 50nm in diameter and several millimetres long

The tropocollagen molecules are staggered in their assembly

The tropocollagen molecules are staggered in their assembly

Tropocollagen molecules are cross-linked between lysine residues and hydroxylysine residues.

Tropocollagen molecules are cross-linked between lysine residues and hydroxylysine residues.

There are clinical disorders arising from errors in collagen synthesis.

1. Osteogenesis imperfecta—there are two possible causes:

• Abnormally short α1 chains: these associate with normal α2 chains but cannot form a stable triple helix and, therefore, nor fibres

• Substitution of the gly residue: replacement with either arg or cys also blocks formation of a stable triple helix

→ symptoms: brittle bones, repeated fractures, and bone deformities in children.

2. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome ( OHCS8, Fig 1 and 2, p.643)—structural weakness in connective tissue.

OHCS8, Fig 1 and 2, p.643)—structural weakness in connective tissue.

• Deficient cross-linking due to a defective enzyme resulting in lower numbers of hydroxylysine residues

• Can also be due to failure to process precursor precollagen into tropocollagen

→ symptoms: hyperextensible skin and recurrent joint dislocation.

3. Marfan’s syndrome ( OHCM8 p.720)—inherited disorder of weakened tissues.

OHCM8 p.720)—inherited disorder of weakened tissues.

• Extra amino acids near C-termini of α2 chains results in reduced cross-linking as residues no longer line up

• Also reduced levels of fibrillin (a small glycoprotein which is an important element of the extracellular matrix)

→ symptoms: weakening, especially of cardiovascular system, causing aortic rupture; skeletal and ocular muscle, lungs, and nervous systems also may be affected.

Fig. 1.5 (a) Arrangement of collagen fibrils in collagen fibres; (b) one type of cross-link formed between two adjacent lysine residues.

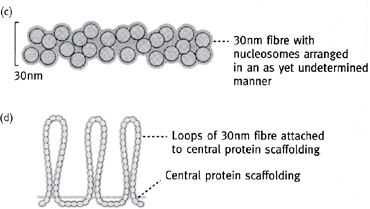

Histones are involved in the packaging of DNA (Fig. 1.6) in a space-efficient way (they increase the packing factor by ~7-fold).

• Histone proteins are globular with a cationic surface which neutralizes the phosphates of the DNA

• Octamer of two each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 proteins has DNA wound around it, and forms a nucleosome, which is often stabilized by the structural H1 protein

• Nucleosomes are further organized into helical arrays called solenoids which, in turn, are arranged around a central protein scaffold, allowing ~2m of DNA in the human nucleus to form the 46 chromosomes with a total length of just 200μm.

Fig. 1.6 Order of chromatin packing in eukaryotes.

Classes of common biochemical reactions:

• Hydrolysis: splitting with water, e.g. breaking of peptide bond

• Ligation: joining of two compounds, e.g. two pieces of DNA

• Condensation: forms water, e.g. synthesis of peptide bond

• Group transfer: movement of a biochemical group from one compound to another

• Redox: reaction of two compounds during which one is oxidized and the other reduced

• Isomerization: physical conversion from one stereoisomer to another.

Biochemical reactions rarely occur in the absence of an enzyme.

• An enzyme is defined as a biological catalyst

• Enzymes increase the rate at which a reaction occurs (usually by at least 106-fold)

• Like a chemical catalyst, the enzyme is unchanged by the reaction that it catalyses, nor does it alter the equilibrium of the reaction (i.e. the forward and reverse reactions are speeded up by the same factor)

• Enzymes are very specific for the reaction that they catalyse, and often enzyme activity is regulated

• Enzymes achieve their catalytic effect by reducing the size of the activation energy step for the reaction (Gibbs’ free energy of activation or ΔG‡, Fig. 1.7)

• ΔG‡ is the difference in the free energy between the free substrates and the transition state

• The substrates binding to the enzyme have a lower transition state energy (i.e. a lower ΔG‡) but can still react to form the same product as they could in free solution.

→ the speed of the reaction is increased.

Fig. 1.7 Enzymes decrease the activation energy.

As well as being effective catalysts, one of the most striking observations concerns enzyme specificity, both in terms of the reaction catalysed and their substrates.

• Usually, only a single reaction is catalysed (or a few very closely related reactions), with a very high, if not absolute, choice of substrate(s)

• The active site is essential for both the catalysis and specificity of enzymes. It is defined by the structure of the enzyme protein, both at the primary level (for essential residues for the reaction) and at higher levels of protein organization (to put these residues in the correct place in the 3D structure).

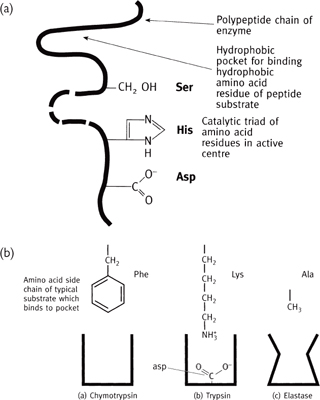

• So named because they have a serine residue which is rendered catalytically active by an aspartate and histidine residue closely adjacent in 3D space (the ‘catalytic triad’)

• These three residues form a charge relay network on the enzyme binding a substrate (Fig. 1.8)

• Family of enzymes includes chymotrypsin, trypsin, elastase, thrombin, and subtilisin.

• Contains a Zn molecule coordinated by two histidine residues, a glutamate, and a water molecule

• These destabilize the substrate and allow it to be attacked by another catalytic glutamate residue, resulting in bond cleavage.

• Cleaves glycosidic bonds between modified sugars of the polysaccharide chains that make up part of the bacterial cell wall

• The substrate is bound in the correct orientation by a number of hydrogen bonds

• This allows a specific aspartate residue to catalyse the cleavage reaction.

• Enzymes can be single proteins, or multimers

• Different tissues can have different forms of the same enzyme (isozymes); these can be used for diagnostic testing. For example, finding the heart muscle isozyme of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH;  p.176) in the blood is indicative of a heart attack (

p.176) in the blood is indicative of a heart attack ( OHCM8 pp.112, 702)

OHCM8 pp.112, 702)

• As well as multimeric enzymes, there are also protein complexes that contain multiple enzyme activities, e.g. pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH;  pp.133, 136).

pp.133, 136).

• Allosteric effectors bind to the enzyme at a site distinct from the active site and modify the rate at which the reaction proceeds

• These changes are brought about by a change in the shape of the enzyme

• Can result either in either increased or decreased rates, e.g. PDH

• Covalent modification, usually by addition of a phosphate group to specific residue(s)

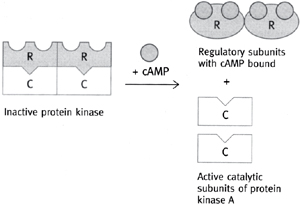

• Subunit dissociation, e.g. cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA, Fig. 1.9)

• Consists of two catalytic (C) subunits and two regulatory (R) subunits

• The R subunit has a pseudosubstrate site for the catalytic unit, and so in the absence of cAMP binds to and inactivates the C subunit

• cAMP binds to the R subunit, allosterically abolishing the pseudosubstrate site so that the R subunit dissociates and leaves the C subunit free to act

Fig. 1.8 Serine proteases: schematic representations of (a) the catalytic triad; (b) the binding site and how substrate specificity is achieved.

Fig. 1.9 Activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) by cAMP (R regulatory subunit of PKA and C catalytic subunit of PKA).

In addition to their protein subunit(s), many enzymes also have essential non-protein components known as co-factors or co-enzymes.

• These co-factors play a vital role in the reaction catalysed by the enzyme

• They are usually either trace elements or derivatives of vitamins.

• Small but essential amounts of minerals are absorbed from the diet and used as co-factors

• Zinc in lysozyme (e.g. superoxide dismutase (SOD))

• Manganese, e.g. isocitrate dehydrogenase in tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle

• Cobalt (constituent of vitamin B12) essential for methionine biosynthesis

• Selenium (glutathione peroxidase)

• Molybdenum oxidation/reduction reactions

• Copper-cytochrome oxidase, SOD.

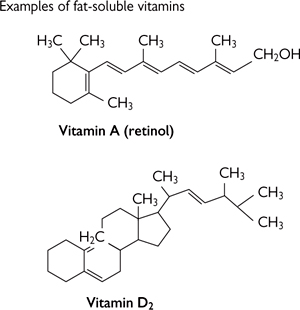

• Vitamins (‘vital amines’) are small organic molecules (Fig. 1.10) that cannot be made by the body and so must be obtained from the diet

• In most cases, vitamins will need to be chemically modified to form the co-enzyme. Modifications range from minor (e.g. phosphorylation) to substantial (e.g. incorporation into much large molecules)

• Lack of vitamins results in metabolic disorders and diseases associated with deficiency, e.g. vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and scurvy ( OHCM8 p.278)

OHCM8 p.278)

Most vitamins are only required in very small amounts in the diet

Most vitamins are only required in very small amounts in the diet

Water-soluble vitamins are usually co-enzyme precursors.

Water-soluble vitamins are usually co-enzyme precursors.

• Biotin → covalently bonded to phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK): gluconeogenesis

• Pyridoxal (vitamin B6) → pyridoxal phosphate: transamination

• Pantothenic acid → co-enzyme A: acyl transfer across the internal mitochondrial membrane (IMM)

• Riboflavin (vitamin B2) → FAD: oxidation reduction, e.g. TCA cycle and electron transport chain (ETC)

• Niacin → NAD: oxidation reduction e.g. TCA cycle and ETC

• Thiamine (vitamin B1) → thiamine phosphate: PDH and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in glycolysis

• Folic acid → tetrahydrofolate derivatives: biosynthetic reactions.

Fig. 1.10 Some vitamin structures.

A number of factors can affect the rate at which enzyme-catalysed reactions proceed (Figs 1.11–1.13), including:

• Temperature: generally, reactions proceed faster with increased temperature until a point is reached at which the crucial higher orders of protein structure are destroyed (‘denaturation’)

• In may, most (but not all) enzymes are most efficient at ~37°C

• pH: the level of protonation of amino acid side-chains in proteins is dependent on the environmental pH

• Most cytosolic enzymes have maximal activity at pH 7.4 whereas, for example, those in the acid environment of the stomach have a much lower pH optimum

• Amount of enzyme: the more enzyme, the more active sites and, therefore, the more reactions can be catalysed. Enzyme activity is often expressed as either the total activity (units of activity per volume of enzyme solution) or the specific activity (units per amount of protein)

• Concentration of substrates and products: enzymes are catalysts and, as such, only increase the speed at which reactions achieve equilibrium, and do not change the equilibrium itself.

Enzyme activity can be measured by looking at the rate at which a product appears (or a substrate disappears) under defined reaction conditions.

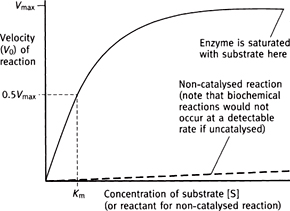

The interaction between enzyme rate (V) and substrate concentration ([S]) can be described for most enzymes by the Michaelis–Menten equation:

This can also be drawn as a Lineweaver–Burke (1/[V] vs 1/[S]) or Eadie–Hoftee (V vs V/[S]) plot.

Useful constants that can be determined from enzyme assay studies include:

• Km: the affinity of the enzyme binding site for its substrate

• Vmax: the maximum rate at which the enzyme can operate (given unlimited substrate)

• Turnover number: the number of reactions that the enzyme can perform per unit time.

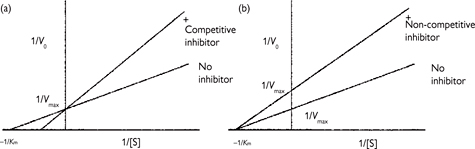

Kinetic analysis allows inhibitors of enzymes to be defined into different classes:

• Irreversible: the inhibitor covalently modifies the enzyme and so permanently inhibits it

• Reversible: these inhibitors do not permanently affect the enzyme. These can be usefully analysed kinetically to determine whether they are competitive or non-competitive

• Competitive: the inhibitor and the substrate compete for the same binding site

• Non-competitive: the inhibitor binds at a site distinct to the substrate binding site.

Fig. 1.11 Effect of pH and temperature on enzyme activity. In (a), (1) represents the majority of enzymes, and (2) gastric enzymes.

Fig. 1.12 Effect of substrate concentration on the reaction velocity catalysed by a classical Michaelis–Menten type of enzyme.

Fig. 1.13 Double reciprocal plots of enzyme reactions in the presence of (a) competitive and (b) non-competitive inhibitors. (Lineweaver–Burke plot.)

Membrane transporter proteins can be split into:

1. Channels: aqueous-filled pores that form a pathway for small hydrophilic substrates (usually ions) to cross lipid bilayers. The passage of substrates is nearly always gated in some way, with the channel being opened by, for example, a compound binding (ligand-gated), a change in membrane potential (voltage-gated), stretching the membrane (stretch-activated). Any of the activators result in a conformational change in the channel that allows the passage of substrate

• Examples: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR, neuromuscular junction), voltage-gated Na+ channels (nerve), stretch-activated Ca2+ channels (smooth muscle)

• Primary active—use ATP hydrolysis to energize movement of substrates

• Examples: Na+/K+-ATPase (aka the sodium pump), Ca2+-ATPase

• Secondary active—use the energy from an (electro)chemical gradient set up by a primary active transporter

• Examples: Na+-glucose co-transporter (SGLT), Na+-Ca2+ exchange

• Facilitated diffusion—speeds up the equilibration of substrates across cell membranes but, unlike the two classes above, cannot concentrate substrates above equilibrium

• Examples: facilitated glucose transporter (GLUT).

Despite the wide range of functions of membrane transporter proteins, they have remarkable similarities regarding their molecular structures, although it should be noted that only a few membrane transporter proteins have been structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography and, thus, much is based on prediction.

• Both channels and transporters have multiple membrane spanning domains (transmembrane domains (TMs)), usually α-helixes, connected by intra- and extracellular loop regions. As the TMs pass through the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer, they tend to be made up of largely hydrophobic amino acids.

• The aqueous pore in the channel is formed from a number of TMs, which have a polar amino acid residue once every turn of the α-helix, giving a polar side to the TM. A number of such TMs then come together, forming a pore lined with hydrophilic residues which thus allows water to enter and substrates to pass through

• The specificity of an ion channel is often determined by the charges on residues at the ‘mouth’ of the channel. For example, the nAChR is a channel for cations and has a ring of negatively charged residues at the mouth of the channel to attract cations and repel anions

• Experimentally reversing these charges with site-directed mutagenesis can turn it into an anion-selective channel.

• Many are predicted to have 12TMs (although estimates can vary between 10 and 14)

• Although the amino acid sequences of the many families of transporters have little in common, there are a few motifs/features

• Proteins with the motif for ATP hydrolysis are known as ABC transporters

• Some transporters appear to have two similar halves, suggesting they evolved from gene duplication

• Function by binding substrate then undergoing a conformational change, resulting in the substrate-binding site being re-orientated to face the opposite side of the membrane

• Binding site is usually very specific for a small number of very closely related substrates

• Binding of substrate to transporter is basis behind transporter kinetics ( p.46).

p.46).

1. ‘Flippases’: ATP-driven transporter proteins which ‘flip’ membrane lipids from one side of the lipid bilayer to the other. Roles in creating/maintaining asymmetric distribution of lipids in membranes, cellular signalling.

• Widely expressed ATP-driven transporter with a wide substrate range of small lipophilic compounds

• Known substrates include a large number of drug molecules, which are exported from cells and out of the body

• This can reduce absorption rates (intestine), increase excretion rates (liver, kidney), and affect tissue distribution (e.g. blood–brain barrier)

• Genetic variations between individuals in pGlycoprotein expression will affect drug efficacy between patients. Gene profiling of patients may allow tailoring of drug prescribing in future (ethically contentious).

3. Cystic fibrosis ( OHCM8 p.166) transmembrane-conductance regulator (CFTR)

OHCM8 p.166) transmembrane-conductance regulator (CFTR)

• CFTR is the channel involved in Cl– exit across the apical membrane in secretion (e.g. sweat glands, pancreatic ducts)

• The majority of CF cases are caused by a mutation leading to the deletion of a single Phe amino acid (ΔF508). The ΔF508 mutant protein misfolds and fails to traffic to the apical membrane.

Lipids play a wide range of roles in the body—from energy storage to hormone signalling, plasma membrane structure to heat insulation. They are a structurally diverse class of macromolecules that have the common feature of being poorly soluble in water (hydrophobic).

• Stored triacylglycerides (‘fat’) makes up about 20% of the body mass of an average person

• Efficient way to store energy:

• Higher specific energy (kJ g–1) than glycogen ( p.114) or protein

p.114) or protein

• Much lower hydration level than glycogen due to lipid’s inherent hydrophobicity

• To store as much energy in glycogen would require approximately a doubling of body mass!

• As discussed elsewhere, lipids (phospholipids, sphingolipids, cholesterol) are the main structural components of the lipid bilayer membranes

• The phospholipids arrange themselves into a bilayer with the polar headgroups facing outwards towards the aqueous environment and the hydrophobic ‘tails’ pointing inwards

• The hydrophobic interior of the bilayer acts as a diffusion barrier to prevent ions or water soluble (hydrophilic) molecules from crossing to enter or leave, for example, the cell (plasma membrane) or organelles

• To be able to cross the membrane, such compounds require a specific pathway (e.g. a channel or transporter,  p.24)

p.24)

• Lipids also stabilize fat–water interfaces

• Bile salts in the intestine: act as detergent-like compounds to emulsify dietary lipid and allow it to be absorbed as chylomicrons

• Phospholipid in membrane: as mentioned above, the polar headgroups allow the formation of the bilayer

• Cholesterol in membrane: as a lipid-soluble molecule, cholesterol inserts into the hydrophobic portion of the membrane. In doing so, it makes the membrane less fluid by sterically inhibiting the movement of the fatty acyl chains

• Pulmonary surfactant: this complex mixture of phospholipids and proteins reduces the surface tension at the interface of the alveolar lining fluid and the air in the lung, preventing alveolar collapse. Premature babies (born before surfactant production begins) are unable to inflate their lungs (infant respiratory distress syndrome). Artificial surfactant can assist in these cases.

• Extracellular—a number of classes of hormones are synthesized from cholesterol

• Eicosanoids (prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes)—derived from arachidonic acid, an abundant component of plasma membrane phospholipids (e.g. as a fatty acid tail of phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidyletholamine). Released by phospholipases A2 in response to hormone signals

• Intracellular—second messengers can be derived from the breakdown of the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). Phospholipase C cleaves the headgroup to leave two components with signalling roles:

• Inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) enters cytoplasm where it causes release of calcium from intracellular stores

• Diacylglycerol (DAG) remains in the membrane

Activates PKC, which has become membrane-associated due to the rise in intracellular calcium

Activates PKC, which has become membrane-associated due to the rise in intracellular calcium

PKC phosphorylates target proteins, affecting their activity.

PKC phosphorylates target proteins, affecting their activity.

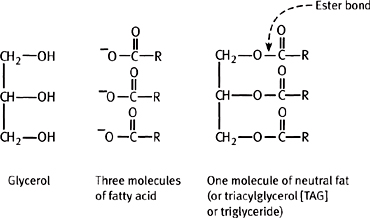

Fatty acids have the general structure of a long hydrocarbon chain (usually 14–24) with a terminal carboxyl group (Fig. 1.14).

• Most animal fatty acids have an even number of carbon atoms ( p.116)

p.116)

• Fatty acids can display different levels of saturation, depending on the number of C=C bonds in the chain.

What is generally thought of as ‘fat’ (i.e. the form that lipids are stored as in the body) are triacylglycerides (triglycerides), consisting of three fatty acids esterified to a glycerol molecule (Fig. 1.15).

• Triacylglycerides are good for energy storage due to their high energy per gram and low hydration level

• Major site of storage: adipocyte cells of adipose tissue.

Fatty acids can be either obtained from the diet or made in the body de novo.

• Triacylglycerides from the diet are absorbed across the intestinal epithelium and transported in the blood by chylomicrons to the liver and adipose tissue, where they are hydrolysed to free fatty acids by lipoprotein lipase and cross into the cell by diffusion

• Triacylglycerides synthesized de novo in the body (mainly in the liver) are carried by very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) to other tissues.

The body does not have the metabolic pathways to make all fatty acids and, therefore, some must be obtained from the diet (essential fatty acids). Mammals cannot introduce C=C bonds past C9 of the hydrocarbon chain.

• Linoleic (C=C at C9 and C12) and linolenic acids (C=C at C9, C12, and C15) are the essential fatty acids. Good dietary source: sunflower seed oil.

Fig. 1.14 (a) Structure of stearic acid (C18); (b) simple representation of fatty acids.

Fig. 1.15 A triacylglycerol and its component parts.

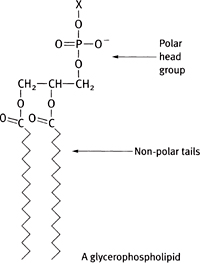

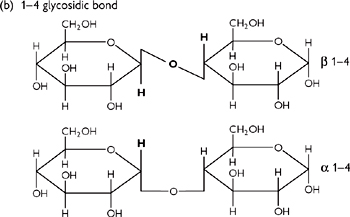

Phospholipids are diacylglycerol molecules with a headgroup attached to the 3-position via a phosphodiester bond (Figs 1.16, 1.17).

• Phospholipids are the major constituent of the plasma membrane lipid bilayer ( p.26)

p.26)

• Phospholipid is the active component of pulmonary surfactant, essential for maintenance of lung structure.

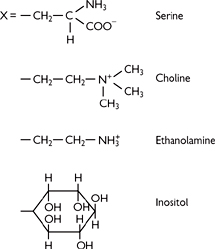

There are several different classes of phospholipids.

• Phosphatidyl compounds: common headgroups include:

• No headgroup except for the glycerol → phosphatidylglycerol. The phosphatidylglycerol can be further modified to cardiolipin

• Ethanolamine → phosphatidylethanolamine

• Choline → phosphatidylcholine (lecithin)

• Inositol → phosphatidylinositol (can be phosphorylated and plays a role in intracellular signalling— p.27)

p.27)

• Sphingolipids have a backbone derived from sphingosine rather than glycerol

• Sphingosine is an amino alcohol with a long (12C) unsaturated hydrocarbon chain

• Sphingomyelin is the only non-phosphatidyl membrane lipid: has a choline headgroup and a fatty acid linked to the sphingosine backbone by an amide bond (Fig. 1.18)

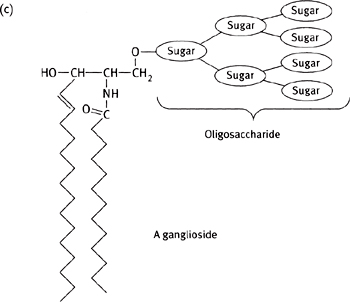

• Many membranes also contain glycolipids, which have a sugar unit for the headgroup

• In animals, glycolipids are also derived from sphingosine

Cerebrosides are the simplest, having the same basic structure as sphingomyelin except with either a glucose or a galactose ester linked in place of the choline group (Fig. 1.18)

Cerebrosides are the simplest, having the same basic structure as sphingomyelin except with either a glucose or a galactose ester linked in place of the choline group (Fig. 1.18)

Gangliosides have more complex sugars as the headgroup, with a branched chain of up to seven sugar residues (Fig. 1.18).

Gangliosides have more complex sugars as the headgroup, with a branched chain of up to seven sugar residues (Fig. 1.18).

Fig. 1.16 The structure of a molecule of phosphatidic acid.

Fig. 1.17 Sample headgroup structures.

Fig. 1.18 Diagram of a molecule of (a) sphingomyelin; (b) a cerebroside; and (c) a ganglioside.

Cholesterol (Fig. 1.19) is a four-ring, 27C compound, synthesized from acetyl-CoA (mainly in liver). Cholesterol is an important lipid in animals, with a variety of roles:

• Component of plasma membranes

• Structural role: affects the fluidity of the membrane

• Precursor of steroid hormones

• All steroid hormones are synthesized by a common pathway starting with cholesterol

Sex hormones (female: progesterone, estrogens; male: testosterone)

Sex hormones (female: progesterone, estrogens; male: testosterone)

Aldosterone (regulates sodium balance)

Aldosterone (regulates sodium balance)

• Conjugated with glycine (glycocholate) or taurine (taurocholate)

• Secreted from liver into intestine to emulsify dietary lipid

• Key role in calcium regulation

• Component of plasma lipoproteins (chylomicrons, VLDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL))

• Involved in transport of cholesterol between tissues

• LDL cholesterol ( OHCM8 p.704) is known as ‘bad cholesterol’ as it is associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis

OHCM8 p.704) is known as ‘bad cholesterol’ as it is associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis

Leads to deposition of cholesterol in plaques which can ultimately block blood vessels. Such blockage of coronary arteries is the cause of coronary artery disease

Leads to deposition of cholesterol in plaques which can ultimately block blood vessels. Such blockage of coronary arteries is the cause of coronary artery disease

Treated with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (‘statins’, (

Treated with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (‘statins’, ( OHPDT2 p.22).

OHPDT2 p.22).

Fig. 1.19 (a) Conventionally drawn structure of cholesterol; (b) structure drawn to indicate actual conformation of cholesterol.

Carbohydrates are the most abundant form of organic matter on earth.

• Contain the elements C, H, and O

• Produced by the fundamental pathway of photosynthesis combining CO2 and H2O

• All animals are ultimately reliant on this source of new organic material.

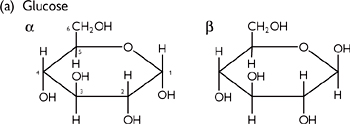

Monosaccharides (sugars) have the general formula (CH2O)n. Most common form are the hexoses (n = 6), e.g. glucose, galactose, fructose.

• Sugars have chiral carbon atoms, so exist as stereoisomers

• D-glucose is the naturally occurring form, sometimes known clinically as dextrose

• As well as stereoisomers, as sugars are cyclisized, a second asymmetrical centre is created, giving two forms:

• The α form is when the hydroxyl group is below the ring

• The β form is when it is above the ring

• α and β forms can interconvert in solution (mutorotation): equilibrium 66% β, 33% α, 1% open chain.

Although sugars may be found as monosaccharides, can also be:

• Disaccharides, e.g. sucrose (glucose-α,1–2-fructose), lactose (galactose-β,1-4-fructose), maltose (glucose-α,1–4-glucose)

• Small multimers (oligosaccharides), e.g. on sphingolipids, glycoproteins

• Mainly found as large multimers (polysaccharides).

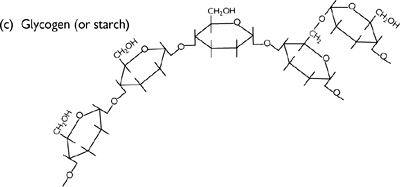

The monosaccharide building blocks are joined by glycosidic (C–O–C–) bonds (Fig. 1.20) which are formed by dehydration reactions.

• They are named from the numbers of the C atoms in the sugars, e.g. a 1,4 bond is a joining of C1 in the first sugar to C4 in the second

• The type of glycosidic bond can have major effects on the final structure (and thus function) of the molecule formed

• This can be seen in the following examples of commonly occurring polysaccharides (Fig. 1.20), all made up of glucose building blocks:

• Glycogen (animal energy storage)

Very large polymer of thousands of glucose monomers

Very large polymer of thousands of glucose monomers

Predominantly joined by α,1–4 glycosidic bonds, with branches via α,1–6 linkages every 8–12 residues, forming a branched tree-like structure

Predominantly joined by α,1–4 glycosidic bonds, with branches via α,1–6 linkages every 8–12 residues, forming a branched tree-like structure

• Starch (plant energy storage)

Mixture of two glucose polymers: amylose is a linear α,1–4 glucose polymer (forms a helix); amylopectin is structurally very similar to glycogen, although the branching is less frequent (every 24–30)

Mixture of two glucose polymers: amylose is a linear α,1–4 glucose polymer (forms a helix); amylopectin is structurally very similar to glycogen, although the branching is less frequent (every 24–30)

• Cellulose (plant structural molecule)

Unlike glycogen and starch, has β,1–4 glycosidic bonds between the glucose monomers to form long straight chains. Chains line up in parallel, stabilized by hydrogen bonding to form fibrils and then fibres. These fibres have the high tensile strength required for their structural role in plant tissue

Unlike glycogen and starch, has β,1–4 glycosidic bonds between the glucose monomers to form long straight chains. Chains line up in parallel, stabilized by hydrogen bonding to form fibrils and then fibres. These fibres have the high tensile strength required for their structural role in plant tissue

Mammals lack the enzyme to digest cellulose (cellulase) and thus it passes undigested through the intestine (known as dietary fibre). Ruminants (e.g. cows) have cellulase-producing bacteria in their digestive tracts.

Mammals lack the enzyme to digest cellulose (cellulase) and thus it passes undigested through the intestine (known as dietary fibre). Ruminants (e.g. cows) have cellulase-producing bacteria in their digestive tracts.

Fig. 1.20 Diagrams of (a) glucose structure; (b) 1–4-glycosidic bond; (c) glycogen (or starch); and (d) cellulose.

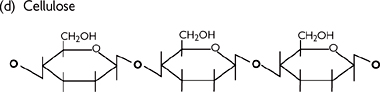

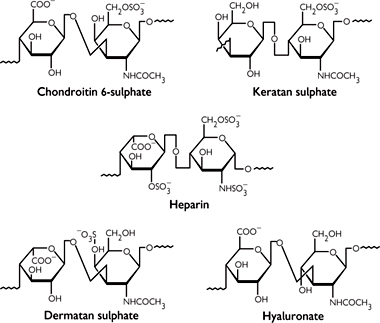

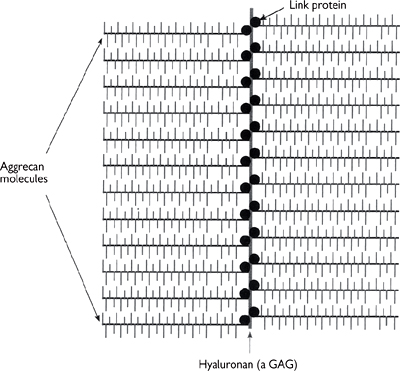

As well as using polysaccharides for energy storage in the form of glycogen, animals also employ structural carbohydrates in the extracellular matrix. Polysaccharide units constitute 95% of proteoglycan, with the remainder being a protein backbone.

• The polysaccharide chains are known as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs; Fig. 1.21). The chains are made up of repeating disaccharide subunits containing either glucosamine or galactosamine (amino sugars)

• At least one of the sugars in the disaccharide has a negatively charged group (either carboxylate or sulphate).

Examples include:

• Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronate, Fig. 1.21)

• Keratan sulphate (Fig. 1.22)

• Found in cartilage extracellular matrix

• Large (around 105kDa), highly hydrated molecule, which acts as a cushion in joints (Fig. 1.23)

• Heparin: present on blood vessel walls where it plays a role in preventing inappropriate blood clotting (see Chapter 6, Haemostasis).

Fig. 1.21 Structural formulae for five repeating units of important glycosaminoglycans.

Fig. 1.22 In cartilage many molecules of aggrecan are attached non-covalently to a third GAG (hyaluronan) via link protein molecules to form a huge complex.

Fig. 1.23 Large, highly hydrated complex GAG molecules form the cushion in cartilage in joints.

While polysaccharides play roles as energy sources and structural components, monosaccharides are also important as precursors in bio-synthetic pathways.

• May be made from glycolysis, pentose phosphate, or TCA cycle intermediates

• Simplest reactions are transaminations ( p.152) to make alanine and aspartate (from pyruvate and oxaloacetate respectively, with glutamate as the nitrogen donor and pyridoxal phosphate as the co-factor)

p.152) to make alanine and aspartate (from pyruvate and oxaloacetate respectively, with glutamate as the nitrogen donor and pyridoxal phosphate as the co-factor)

• Aspartate is a precursor for other amino acids (→ asparagine, methionine, threonine (→ isoleucine, lysine))

• α-ketoglutarate → glutamate (→ glutamine, proline, arginine)

• 3-phosphoglycerate → serine (→ cysteine, glycine)

• Pyruvate → alanine, valine, leucine

• Phosphoenolpyruvate + erythrose-4-phosphate → phenylalanine (→ tyrosine), tyrosine, tryptophan

• Ribose-5-phosphate → histidine.

• Fat is a major energy storage form

• Excess carbohydrate enters the TCA cycle as normal, but as cell does not need to make ATP, the level of citrate builds up

• Citrate leaves the mitochondrial matrix and enters the fatty acid synthetic pathway ( p.120).

p.120).

• Nucleotides consist of a sugar moiety and a nitrogenous base

• The sugar ribose-5-phosphate is the starting place for the synthetic pathway of the purine bases

• In contrast, the pyrimidine base is made first, and then linked to ribose-5-phosphate

• Deoxyribonucleotides are made by reduction

• The ribose 5-phosphate is synthesized from glucose 6-phosphate by the pentose phosphate pathway ( p.138).

p.138).

Many proteins and lipids have carbohydrate moieties attached: the majority of secreted proteins (e.g. antibodies), many integral membrane proteins, and membrane lipids.

There are two ways in which carbohydrates can be attached to proteins:

• O-glycosidic link (O-linked) to the hydroxyl group of a serine or threonine

• N-glycosidic link (N-linked) to the amine group of asparagines

• Consensus sequence Asn-X-Ser or Asp-X-Thr

Motif necessary but not always used due to protein 3D structure constraints

Motif necessary but not always used due to protein 3D structure constraints

• First two sugars added always N-acetylglucosamines, followed by three mannose residues that form a ‘core’. Addition of further monosaccharides gives rise to a huge diversity of oligosaccharide structures of two major forms:

High mannose—additional mannose residues added to the core described

High mannose—additional mannose residues added to the core described

Complex—variety of (less common) monosaccharide units added to core.

Complex—variety of (less common) monosaccharide units added to core.

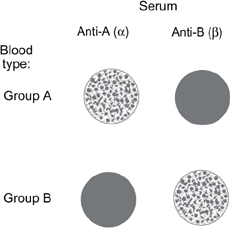

The wide diversity of protein-linked oligosaccharide suggests a variety of functionally important roles, although these are not well understood at present. One important role is as recognition signals, of which blood groups are a good example:

• There are four major blood groups in humans: A, B, AB, and O ( p.410)

p.410)

• These correspond to the presence of certain oligosaccharide residues on the erythrocyte integral membrane proteins (e.g. glycophorin A)

• There is a basic core oligosaccharide, which can have a different terminal sugar or none at all (Figs 1.24, 1.25)

• Some individuals do not have the enzymes (glycosyl transferases) to add the terminal sugar (type O), whereas others can make type A, some type B, and some both (type AB).

The main glycolipids are based on the sphingolipids, with one or more sugars replacing the sphingosine headgroup of the phospholipids ( p.30). There are two groups:

p.30). There are two groups:

• Cerebrosides: simple glucose or galactose residue. Important in brain cell membranes

• Gangliosides: more complex branched chain of several monosaccharide groups. Distinguish the blood group types in erythrocytes.

Fig. 1.24 The molecular basis of ABO blood groups: (a) type A; (b) type B; and (c) type O.

Fig. 1.25 The agglutination reaction of incompatible blood types. If the blood sample is compatible, the mixed blood sample appears uniform. If the blood is incompatible with the serum, it aggregates and precipitates as shown. Reproduced with permission from Pocock G, Richards CD (2004). Human Physiology: The Basis of Medicine, 4th edn. London: Oxford University Press.

DNA and RNA are nucleic acids.

• Consist of a long polymer of nucleotides (also known as bases)

• Nucleotides are made up from a nitrogenous base, a sugar (deoxyribose in DNA, ribose in RNA), and a phosphate group

• There are two types of nitrogenous base:

• The purines: guanine (G) and adenine (A)

• The pyrimidines: cytosine (C) and thymine (T, only in DNA) or uracil (U, only in RNA)

• DNA has a polarity, in that it is always read 5′→3′

• The terms 5′ and 3′ refer to the free carbon atom from the sugar which is free at the end of the chain in question

The 5′ end has a phosphate on the C5 of the (deoxy)ribose

The 5′ end has a phosphate on the C5 of the (deoxy)ribose

The 3′ end finishes with a hydroxyl group on the C3

The 3′ end finishes with a hydroxyl group on the C3

• DNA strands associate into pairs and run in opposite directions (anti-parallel) (Fig. 1.26)

• Base pairing rules are always followed

• C pairs with G with three hydrogen bonds

• A pairs with T (or U in RNA) with two hydrogen bonds

• The two strands of anti-parallel DNA form a double helix (Fig. 1.27)

• Elucidated from X-ray diffraction images of crystallized DNA

• Structure solved by Watson and Crick (1953).1

DNA replication is semi-conservative ( p.64)

p.64)

The sequence of the nucleotides codes for amino acids in proteins.

• Codons are triplets of bases that code for an amino acid

• 43 = 64 potential triplets, so some of the 20 amino acids in proteins are coded for by more than one triplet (Table 3.1,  p.185)

p.185)

• ATG is the start codon for almost all proteins

• TAG, TGA, and TAA are all stop codons.

Fig. 1.26 Two anti-parallel strands of DNA (B = base).

Fig. 1.27 Outline of the backbone arrangements in the DNA double helix, showing the base pairs in the centre of the helix.

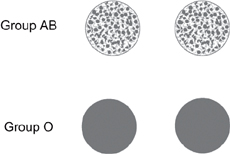

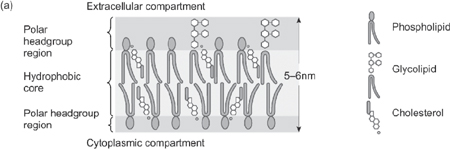

Plasma membranes establish discrete environments (Fig. 1.28). The cell membrane bounds the cell contents; other membranes establish cell inclusions—the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic (sarcoplasmic) reticulum, Golgi vesicles, lysosomes, endosomes.

• Membranes are fluid mosaics: there is a lipid bilayer, in which proteins are embedded

• The fluidity derives from free movement of both lipids and proteins within the membrane

• Membranes can be 25% protein:75% lipid (myelinated nerves) or 75% protein:25% lipid (mitochondrial membrane)

• Membrane proteins and lipids are often also glycosylated and contribute to the glycocalyx

• There are three lipid classes:

• phospholipids; sphingolipids; cholesterol

• Bipolar phospholipids are most abundant

• They comprise a charged headgroup and two uncharged hydrophobic tails

• The tails face inwards, thereby forming the bilayer

• Polar headgroups face the extra and intracellular environments

• Lipid tails can have kinks due to double bonds

• For most phospholipids, there are four chemical components:

• fatty acids, glycerol, phosphate, and one other species

• Principal lipids are: phosphatidylcholine (lecithin), phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine

• Sphingolipids have a similar structure and can be glycosylated

• Cholesterol, an unsaturated alcohol (sterol) inserts between phospholipids and influences membrane fluidity. This allows lateral diffusion of membrane proteins, important for hormone-receptor coupling.

Membrane composition is asymmetrical: the inner half of the bilayer contains more phospholipids with negatively charged headgroups (e.g. phosphatidylserine). A ‘flippase’ enzyme (a member of a family of proteins such as MDR or P-glycoprotein) uses ATP as an energy source, sweeping the membrane to preserve asymmetry. Asymmetry maintains cell shape (although proteins and the cytoskeleton also play a major role) and ensures correct association of particular proteins with certain lipid species.

Membrane proteins can be integral or extrinsic (or peripheral).

Integral proteins:

• Receptors: transmembrane proteins which bind ligands, undergo conformational changes to:

Initiate enzyme activity on an intracellular domain

Initiate enzyme activity on an intracellular domain

Open a pore through the protein

Open a pore through the protein

Activate intracellular signalling cascades

Activate intracellular signalling cascades

• Transporters: channels or carriers

• Adhesion molecules: integrins for extracellular matrix, cadherins for cells

• Can span the membrane once or may have multiple, closely packed transmembrane segments (e.g. 10 spans in the Na+-K+ ATPase). Transmembrane spans are typically 25 amino acid α-helices—hydrophobic residues face the lipid environment of the membrane

• In some cases only partially cross the membrane or sit at the extra or intracellular faces and link to phospholipids by oligosaccharides (GPI-linked proteins)

• Can be multimers made of non-covalent bound subunits. Multimers may comprise multiple copies of a single protein or two or more different ones

• Can combine in non-mobile clusters or act as anchors for non-covalent binding of extrinsic cytoskeletal proteins.

Extrinsic proteins:

• Form non-covalent bonds with integral proteins

• May be components of the cytoskeleton (e.g. spectrin, ankyrin), that bind transmembrane channels, carriers, adhesion molecules. They define cell shape, strength, and polarity.

Fig. 1.28 The structure of the plasma membrane: (a) the basic arrangement of the lipid layer; (b) a simplified model showing the arrangement of some of the membrane proteins.

Membranes form selective barriers to maintain the composition of different compartments. Without proteins, only small non-polar solutes would permeate the lipid bilayer. Even when lipid permeability exists, movement can be augmented by protein pathways.

• The simplest pathway is solubility diffusion through lipid.

• Gases such as oxygen can dissolve in the lipid and then diffuse passively through Brownian motion along concentration gradients according to Fick’s Law: J = –D × A × ΔC/Δ×

where J = diffusion flux

D = diffusion coefficient of solute

A = surface area of membrane

ΔC = concentration gradient

Δx = membrane thickness

• Diffusion is a passive process: there is no direct energy expenditure involved

• Water also diffuses across membranes by osmosis, from regions of high water concentration (hypo-osmotic) to regions of low water concentration (hyperosmotic)

• Although water can dissolve in and diffuse through lipids, cell membranes contain selective aquaporin proteins that convey a high permeability to water, and mean that osmotic gradients cannot be sustained. Water movements cease when intracellular and extracellular solutions become isotonic.

Other solutes, including ions and some organic osmolytes such as taurine also move across the membrane by passive diffusion through channels which are water-filled protein pores.

• Channels can be constitutively open (leak channels) or gated—that is, opened by:

• Change in membrane potential

• The extracellular binding of a ligand to the channel itself or to a G-protein-linked receptor associated with the channel

• The intracellular binding of a second messenger (such as cGMP)

• Channels can be selective for the ions that can permeate. There are families of channels specific for ions including Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Cl–.

• Gap junctions are channels connecting cytoplasm of two cells. Each membrane contains connexons, comprising six connexins which form a pore. The two pores are aligned to make a patent, non-selective channel for electrical and chemical cell–cell communication.

Other transport processes are mediated by carrier proteins (Fig. 1.29).

• Carriers undergo a conformation change to present the solute at the opposing face. The binding and conformation change processes mean that the process is: