Orbital plates of frontal bone

Orbital plates of frontal boneThe skull and cervical vertebrae

Blood and lymphatic vessels of the head and neck

The structures of the central nervous system

Motor control and sensory functions

Visual system: central visual pathways

The bones of the skull form the cranium and facial skeleton (Figs 11.1–11.8).

The cranium contains the brain and immediate relations and is divided into:

• The upper vault—comprising four flat bones:

• The occipital bone posteriorly

• The lower base, characterized by stepped fossae:

• Anterior (containing the frontal lobes of the brain) formed from:

Orbital plates of frontal bone

Orbital plates of frontal bone

Cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone

Cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone

Lesser wing of the sphenoid bone

Lesser wing of the sphenoid bone

• Middle (containing the temporal lobes of the brain) formed from:

Greater wing and body of the sphenoid bone

Greater wing and body of the sphenoid bone

(Vertical) squamous and (horizontal) petrous parts of temporal bone

(Vertical) squamous and (horizontal) petrous parts of temporal bone

• Posterior (containing cerebellum, pons. medulla oblongata) formed from:

Squamous part of occipital bone

Squamous part of occipital bone

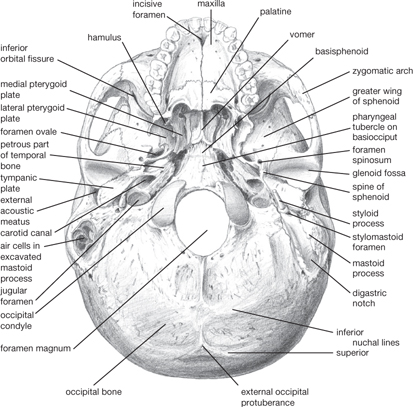

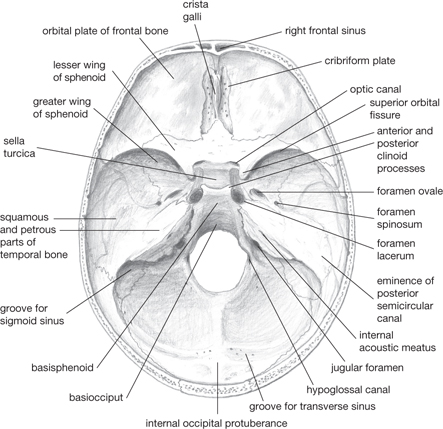

There are a number of important features in the base of the skull (Figs 11.3, 11.4, 11.6):

• In the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bones

Foramina convey the olfactory nervecranial nerve I

Foramina convey the olfactory nervecranial nerve I

Fig. 11.1 Posterior aspect of skull.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p46 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.2 Skeletal components of skull and anterior part of the neck. Cervical vertebrae (not shown) are formed from cervical sclerotomes.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p44 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p48 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.4 Basal aspect of skull. The hypoglossal canal is covered by the occipital condyles.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p47 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

• In the greater wing of the sphenoid bone

The foramen ovale conveys the mandibular division of trigeminal nerveVII and the lesser petrosal nerve

The foramen ovale conveys the mandibular division of trigeminal nerveVII and the lesser petrosal nerve

The foramen rotundum conveys the maxillary division of trigeminal nerveVIII

The foramen rotundum conveys the maxillary division of trigeminal nerveVIII

The foramen spinosum conveys middle meningeal artery and vein

The foramen spinosum conveys middle meningeal artery and vein

• At the medial edge of the petrous part of the temporal bone

The upper part of the foramen lacerum conveys the internal carotid artery (from the carotid canal)

The upper part of the foramen lacerum conveys the internal carotid artery (from the carotid canal)

• Between the body and lesser wing of the sphenoid bone

The optic canal conveys the optic nerveII and ophthalmic artery

The optic canal conveys the optic nerveII and ophthalmic artery

• Between the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid

The superior orbital fissure conveys the oculomotor nerveIII, trochlear nerveIV, ophthalmic branch of trigeminal nerveVI, and abducent nerveVI

The superior orbital fissure conveys the oculomotor nerveIII, trochlear nerveIV, ophthalmic branch of trigeminal nerveVI, and abducent nerveVI

The sella turcica is a depression in which sits the pituitary gland

The sella turcica is a depression in which sits the pituitary gland

The junction of the frontal, parietal, and temporal bones—the pterion—is the thinnest and weakest point of the lateral skull (Fig. 11.5)

The junction of the frontal, parietal, and temporal bones—the pterion—is the thinnest and weakest point of the lateral skull (Fig. 11.5)

The foramen magnum conveys the medulla oblongata, spinal part of accessory nerveXI, upper cervical nerves, vertebral arteries

The foramen magnum conveys the medulla oblongata, spinal part of accessory nerveXI, upper cervical nerves, vertebral arteries

Anterior to the foramen magnum the brainstem lies on the clivus (fused basiocciput and basisphenoid)

Anterior to the foramen magnum the brainstem lies on the clivus (fused basiocciput and basisphenoid)

The hypoglossal canal conveys the hypoglossal nerveXII

The hypoglossal canal conveys the hypoglossal nerveXII

• In the petrous temporal bone

The internal acoustic meatus conveys facial nerveVII, vestibulocochlear nervesVIII, labyrinthine artery

The internal acoustic meatus conveys facial nerveVII, vestibulocochlear nervesVIII, labyrinthine artery

• Between the petrous temporal bone and the occipital bone

The jugular foramen conveys the glossopharyngeal nerveIX, vagus nerveX, accessory nerveXI, and the sigmoid sinus.

The jugular foramen conveys the glossopharyngeal nerveIX, vagus nerveX, accessory nerveXI, and the sigmoid sinus.

The pyramidal pterygopalatine fossa is defined by the sphenoid, palatine, and maxilla bones: it contains the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve, maxillary artery, and accompanying veins and lymphatics.

The bones forming the facial skeleton (Fig. 11.5) are suspended below the anterior cranium and comprise:

• Two nasal bones, joined to form the ridge of the nose

• Two maxillary bones, which form the floor of orbit, lateral wall of the nose, floor of the nasal cavity, and carry upper teeth

• Two lacrimal bones, which form medial wall of orbit

• One ethmoid bone, which forms the roof of the nose

• The cribriform plate of the ethmoid, along with the vomer and septal cartilage, form the nasal septum

• Two zygomatic bones, which form lateral wall of the orbit, cheek bone

• A perpendicular plate, which contributes to lateral wall of orbit

• A horizontal plate, which, together with the palatine processes of the maxillary bones, forms the hard palate.

Fig. 11.5 Lateral aspect of skull, pterion circled.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p47 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.6 Interior of skull. The foramen rotundum is hidden by the anterior clinoid process.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p48 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

There are four paired paranasal air sinuses, contained within the frontal, maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones.

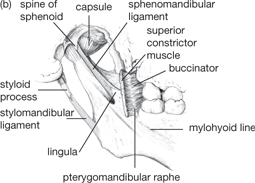

The mandible carries the lower teeth. It articulates with the cranium at the temporomandibular joint, which is:

• Between the head of the mandible and the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone

• A synovial joint containing a fibrocartilaginous disc

• Encapsulated, with reinforcement by temporomandibular, sphenomandibular, stylomandibular ligaments.

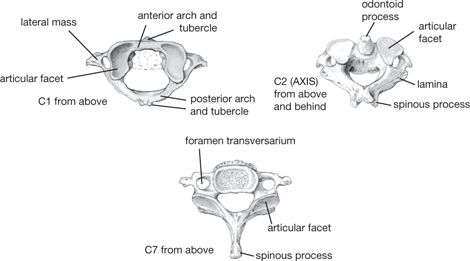

Seven cervical vertebrae form the skeleton of the neck. C1 (the atlas), C2 (the axis), and C7 are atypical (Fig. 11.9). The long spine of C7 is the vertebra prominens—the superior-most process which can be palpated.

The lateral masses of the C1 vertebra articulates with condyles on the occipital bone at the atlanto-occipital joint, which is a loosely encapsulated synovial joint that permits flexion and extension (nodding movements).

Lateral masses of the atlas articulate with superior facets of the axis at atlanto-axial joints to permit rotation. In addition, the odontoid process or dens makes a midline articulation with an anterior facet.

The transverse part of the cruciate ligament (Fig. 11.10) of the atlas holds the dens in place, prevents the dens impinging on the spinal cord. Alar ligaments from the dens to the margin of the foramen magnum prevent excessive rotation. Longitudinal ligaments attach to the anterior and posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies.

Joints between the C2 and T1 vertebrae possess anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments. Supraspinous and infraspinous ligaments are replaced by the nuchal ligament between occipital bone and C7; these joints permit flexion and extension.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p120 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.8 Temporomandibular joint and its ligaments: (a) lateral aspect; (b) medial aspect.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p82 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.9 Atlas (C1), axis (C2), and C7 vertebrae.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p56 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.10 Ligaments of the occipito-atlanto-axial region: midline section.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p58 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

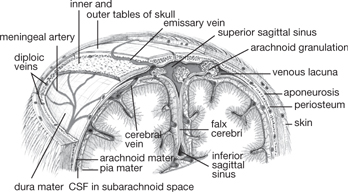

Three connective tissue layers surround the brain and spinal cord.

The inelastic dura mater comprises:

• Outer endosteal layer (the periosteum), which lines the bones of the cranium and at openings of the skull and is continuous with that on outer surface

• Inner meningeal layer, which is continuous with that of the spinal cord.

Meningitis is inflammation of the meninges caused by bacteria, viruses, or fungi ( OHCM8 p.832).

OHCM8 p.832).

At some points, the meningeal layer doubles-back on itself to form dural folds. These provide four septa:

• The midline falx cerebri, between the cerebral hemispheres, which meets

• The horizontal tentorium cerebelli, the roof of the posterior fossa, and separates the cerebrum from the cerebellum

• The falx cerebelli which descends from the tentorium and separates the cerebellar hemispheres

• The diaphragm sellae which provides the roof of the sella turcica.

The middle layer—the arachnoid mater—follows the folds of the meningeal layer of dura mater, to which it is loosely attached. Between the two is the subdural space; the innermost layer—the pia mater—closely envelopes the brain and spinal cord. It is separated from the arachnoid mater by the subarachnoid space, filled with CSF, which cushions the brain (Fig. 11.12).

• Bleeding can occur into the potential spaces created by the dura folds.

• Extradural haemorrhage can occur following head trauma, and results from laceration of middle meningeal artery and vein ( OHCM8 p.486)

OHCM8 p.486)

• Subdural bleeds can occur insidiously following minor trauma and result from damage to bridging veins between cortex and venous sinuses ( OHCM8 p.486)

OHCM8 p.486)

• Subarachnoid haemorrhages are spontaneous, most commonly due to rupture of an aneurism ( OHCM8 p.482).

OHCM8 p.482).

CSF is secreted by the choroid plexus (a vascularized epithelial structure) into each of the ventricles of the brain.

• CSF escapes from the fourth ventricle of the brain into the subarachnoid space

• It exchanges freely with the extracellular fluid surrounding neurones across the pia mater covering the surface of the brain and across the epithelial lining (ependyma) of the ventricles. Failure for this to happen is a cause of hydrocephalus ( OHCM8 pp.471, 482, 490)

OHCM8 pp.471, 482, 490)

• In the choroid plexus, the epithelial cell barrier dictates the composition of CSF and insulates it from the blood. Elsewhere, the tight capillary endothelium prevents free exchange between the blood and the brain extracellular fluid. In these ways, the blood–brain barrier is established.

Fig. 11.11 Dural venous sinuses.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p144 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.12 Circulation of cerebrospinal fluid.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p144 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.13 Coronal section through cranium to show scalp, meninges, and arachnoid granulations.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p145 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Blood is supplied to the brain by:

• The vertebral arteries (from subclavian artery)

• They unite in the midline on the clivus as the basilar artery, and together these supply the brainstem and cerebellum

• The basilar artery divides into left and right posterior cerebral arteries; these provide the posterior communicating arteries, which anastomose with the internal carotid artery

Fig. 11.14 (a) Arteries, (b) veins of the face.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p169 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.15 Vertebral artery and its main branches.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p155 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

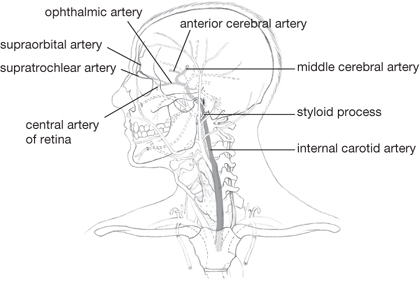

• The internal carotid artery (from the common carotid artery; Figs 11.16, 11.17)

• Passes into the middle fossa in the carotid canal, through the foramen lacerum, then in the medial wall of the cavernous sinus

• Gives rise to the ophthalmic artery, the central artery of the retina, and ciliary arteries

• Terminates as the anterior and middle cerebral arteries, which supply the medial and lateral cerebral hemispheres, respectively

• The anterior communicating artery unites the anterior cerebral arteries, completing the anastomosis between carotid and vertebral systems (the circle of Willis, which equalizes blood pressure)

Fig. 11.16 Common and internal carotid arteries and their main branches.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p156 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.17 Intracranial branches of the vertebral artery; circle of Willis.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p155 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

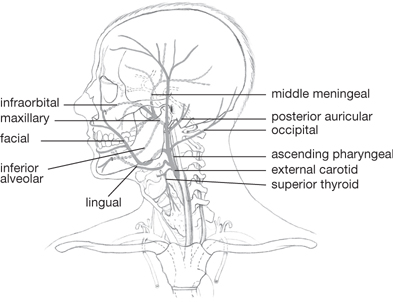

The second division of the common carotid artery is the external carotid artery (Fig. 11.18). This artery has many branches which supply the structures of the head and neck other than the brain: superior thyroid; ascending pharyngeal; superficial temporal; lingual; facial; occipital; posterior auricular; and superficial temporal.

It has two terminal branches which arise within the parotid gland:

• The (larger) maxillary artery, which gives off three groups of branches that supply the temporal fossa, infratemporal fossa, cranial dura, nasal cavity, oral cavity, and pharynx

• The superficial temporal artery.

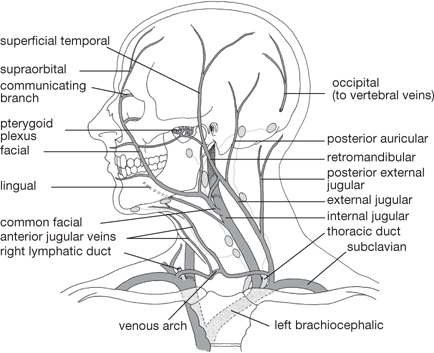

Between the two layers of the dura mater, intracranial venous sinuses lie in grooves on the overlying bone. These drain tributary veins from the brain, eye, and skull interior, diploic veins from the marrow of the cranial bones, and CSF from the subarachnoid space. The superior sagittal sinus runs in the attached margin of the falx cerebri, with lacunae along its length containing arachnoid granulations to reabsorb CSF. The sinus drains into:

• The transverse sinus which runs along the attached margin of the tentorium cerebelli, then turns inferiorly to become the sigmoid sinus

• The inferior sagittal sinus which runs in the free margin of the falx cerebri

• The straight sinus which forms from the unification of the inferior sagittal sinus and the great cerebral vein

• The intercommunicating cavernous sinuses are positioned either side of the sphenoid, pituitary gland and drain into the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses, which drain into the transverse and sigmoid sinuses, respectively

• The sigmoid sinus, which drains into the internal jugular vein.

Fig. 11.18 External carotid artery and its branches.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p158 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

There are also extracranial veins:

• The supratrochlear vein and supraorbital vein drain the forehead

• The facial vein, superficial temporal vein, and postero-auricular veins drain the face and scalp

• The superior temporal vein unites with the maxillary vein to form the retromandibular vein, which bifurcates to unite with:

• The facial vein (anteriorly) as it enters the internal jugular vein

• The posterior auricular vein to establish the external jugular vein.

In the neck:

• The external jugular vein receives the anterior jugular vein which has drained the superficial chin and neck, then itself drains into the subclavian vein

• The internal jugular vein receives tributaries from the neck, then unites with the subclavian vein to establish the brachiocephalic vein.

Superficial vessels accompanying superficial veins drain into a collar of nodes around the neck, the including submental, submandibular, parotid, mastoid, and occipital groups. The nodes in turn drain to deep cervical nodes, which drain deeper structures. These nodes drain through jugular trunks into the venous circulation at the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins.

The lingual and palatine tonsils, together with the retropharyngeal lymphatic tissue, form a ring of lymphatic tissue in the mucosa and submucosa of the nose, pharynx, and mouth.

Fig. 11.19 Venous drainage of head and neck (intracranial venous sinuses not shown); position of major groups of lymph nodes.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p160 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Nerve supply is indicated by superscript.

• TrapeziusXI elevates, retracts, and laterally rotates scapula

• PlatysmaVII depresses skin of lower face and mouth, depresses mandible

• SternomastoidXI flexes and rotates neck

• Scalene musclesC3–8 laterally flex, rotate neck

• Suprahyoid muscles elevate the hyoid: digastricVII; stylohyoidVII; mylohyoidVII; geniohyoidC1

• Infrahyoid (‘strap’) muscles

• Depress the hyoid: sternohyoidC1,3; thyrohyoidC1; omohyoidC1,2,3

• Depress the larynx: sternothyroidC1,2,3.

The muscles of the neck define two triangles:

• Subclavian artery and branches

• Spinal part of accessory nerve

• Pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, trachea

• Thyroid, parathyroid, submandibular, parotid glands

• Suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles

• Glossopharyngeal, vagus, hypoglossal nerves, and sympathetic chain

• Strap muscles and their nerve supply (ansa cervicalisC1,2,3)

• Carotid arteries and branches

• Internal and external jugular veins.

Fig. 11.20 Anatomical relations used to describe movements of the head and neck.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p4 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Within the anterior triangle, four smaller triangles—the superior carotid, inferior carotid, suprahyoid (submandibular), and submaxillary (submental)—are created by the digastric and omohyoid muscles.

Fig. 11.21 Muscles of the neck.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p60 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.22 Fascial planes of the neck.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p61 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

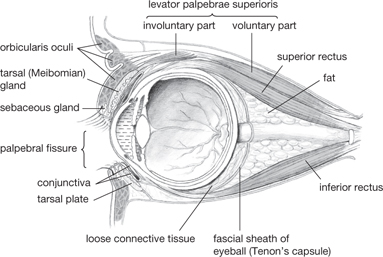

Sphincters and dilators, between bone and overlying skin:

• Sphincter: orbicularis oculi

Palpebral portion in the eyelids

Palpebral portion in the eyelids

Orbital portion around the orbital margin

Orbital portion around the orbital margin

• Dilator: occipitofrontalis, levator palpebrae scapularis (skeletalIII and smooth musclesympathetic nervous system)

• Compressor and dilator nares

Levator labii superioris, levator anguli oris, zygomaticus major and minor

Levator labii superioris, levator anguli oris, zygomaticus major and minor

Depressor labii inferioris, depressor anguli oris

Depressor labii inferioris, depressor anguli oris

• Buccinator defines the size of the cavity between cheek and teeth.

Platysma in the lateral neck pulls the mouth downwards.

Fig. 11.23 Muscles of facial expression.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p67 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

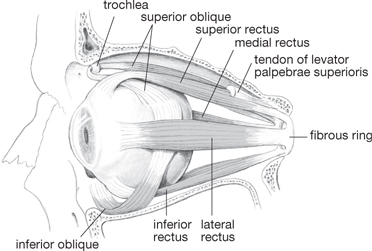

• Extrinsic muscles, made of striated (skeletal) muscle fibres. Actions on cornea:

• Superior rectusIII: up, medial

• Inferior rectusIII: down, medial

• Medial rectusIII: medial rotation

• Lateral rectusVI: lateral rotation

• Superior obliqueIV: down, lateral

• Inferior obliqueIII: up, lateral

• Intrinsic muscles, made of smooth muscle. Actions:

• Sphincter pupillae of irisIII: constriction of pupil

• Dilator pupillae of irissympathetic nervous system: dilation of pupil

• Ciliary muscleIII: fattens lens.

Fig. 11.24 Sagittal section through orbit.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p121 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.25 Extrinsic muscles of eyeball.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p123 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Acting on the mandible:

• Elevate the mandible, close the mouth

• TemporalisVIII (also retracts)

• Depress the mandible, open the mouth

In addition, digastric, stylohyoid, and mylohyoid depress and geniohyoid elevates the mandible.

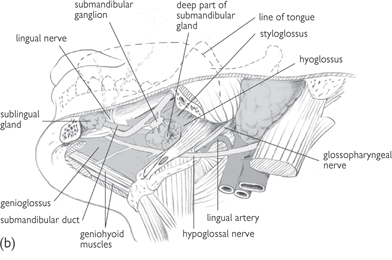

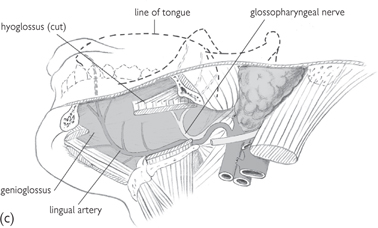

Extrinsic muscles:

• GenioglossusXII provides the bulk, draws forward, retracts tip

• StyloglossusXII elevates, retracts

• Palatoglossuspharyngeal plexus elevates.

Intrinsic muscles:

• Interlaced longitudinal, transverse, vertical fibresXII alter shape of tongue.

• Tensor palatiniVIII tenses soft palate

• Levator palatiniX, XI via pharyngeal plexus elevates soft palate

• Palatopharyngeuspharyngeal plexus depresses soft palate

• Palatoglossus depresses soft palate

• Uvular musclepharyngeal plexus elevates uvula.

There are three circular overlapping muscles—superior, middle, and inferior constrictor musclespharyngeal plexus—which contract sequentially during swallowing to propel the bolus of food downwards.

Inner, longitudinal muscles—palatopharyngeuspharyngeal plexus, salpingopharyngeuspharyngeal plexus, and stylopharyngeusIX—shorten the pharynx and elevate the larynx to close the laryngeal inlet against the base of the tongue during swallowing.

Intrinsic musclesX modify the shape of the airway through the larynx. They include:

These muscles have roles in regulating airway diameter during swallowing, coughing, and vocalization.

Fig. 11.26 Progressively deeper dissections (a), (b), and (c) of the side of the floor of the mouth; viewed from below and to the left.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p84 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

OHCM8 p.76)

OHCM8 p.76)There are 12 cranial nerves—see Table 11.1.

• Sensory functions are performed by I (smell); II (vision); VIII (balance and hearing)

• Motor functions are performed by IV (eye); VI (eye); XI (pharynx, larynx, shoulder, neck); XII (tongue)

• Mixed sensory, motor, and autonomic (parasympathetic: III—motor; VII and IX—secretomotor (see page 219)) functions are performed by the remaining five nerves.

Formed from anterior rami of C1–5 and located behind the carotid sheath. C1 emerges above the atlas, while C2–4 pass through the intervertebral foramina above the corresponding cervical vertebra.

Segmental branches supply the prevertebral muscles. In addition, the ansa cervicalis supplies the strap muscles though upper (C1) and lower limbs.

Sensory fibres carried in C2–4 are arranged as the lesser occipital nervenerve root of C2, the great auricular nerveC2,3, the transverse cutaneousnerveC2,3, and the supraclavicular nerveC3,4.

The phrenic nerve formed from C3–5 passes to the diaphragm to provide motor supply and sensory supply to the overlying pleura and peritoneum.

Posterior primary rami of cervical nerves segmentally supply the extensors of the neck.

Fig. 11.27 (a) Motor and (b) sensory nerves of the face.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p69 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.28 Origin of the cranial nerves from the brainstem.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p167 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.29 Cervical plexus. The ansa cervicalis has been deflected medially; it normally lies anterior to the plexus.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p189 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

A sphere, ~2.5cm in diameter, with the cornea bulging forwards. The anterior chamber is situated between the cornea and the iris. The iris defines the pupil, which leads to the posterior chamber between the muscular iris and lens.

The anterior and posterior chambers contain aqueous humour. The vitreous chamber behind the lens contains vitreous humour.

In coronal section, three layers can be discerned:

• The sclera, which anteriorly gives rise to the transparent cornea covered by stratified epithelium

• The pigmented choroid, lining the posterior eyeball, which becomes the iris and, in the posterior chamber, establishes a ciliary body from which ciliary processes secrete aqueous humour

• The retina (the innermost layer), comprises a pigmented epithelium under which lie receptor cells the rods and cones. Neuronal ganglion cells from the rods and cones converge on the optic disc to unite as the optic nerve.

The intrinsic muscles of the eye sphincter and dilator pupillae control pupil diameter. The lens is suspended from the ciliary body by the circular suspensory ligament; the tension of the ligament, and hence the curvature of the lens, is determined by the ciliary muscle.

The macula lies lateral to the optic disc; it is the site of sharpest vision (the fovea) and contains only cones.

Retinal arteries and veins, derived from the central artery of the retina and associated veins, pass with the optic nerve, and run on the vitreous aspect of the retina.

Two folds of skin constitute the eyelids, separated by the palpebral fissure. The inner surface of the eyelids is covered by a mucosal layer (the conjunctiva) which is continuous with the surface of the eyeball to form the conjunctival sac. The fibrous orbital septum acts as a framework for the eyelid and is thickened at the margins to form tarsal plates and medial and lateral palpebral ligaments.

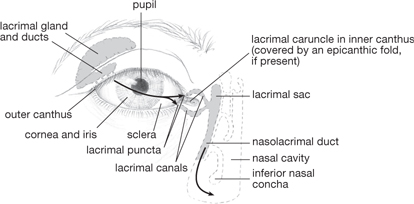

Lacrimal gland secretions (tears) enter the conjunctival sac at the lateral upper eyelid. Tears drain into the lacrimal puncta, through canals to the lacrimal sac, and then, via the nasolacrimal duct, to the nose (Fig. 11.32).

Fig. 11.30 Coronal section of the front eye.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p119 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.31 Internal features of the eye: horizontal section.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p118 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.32 Eye and lacrimal apparatus.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p122 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

The ear is divided into three structures—the outer ear, the middle ear, the inner ear.

Comprises the auricle—a fold of skin reinforced by cartilage from which the external auditory meatus, made of cartilage and then bone, extends to the tympanic membrane.

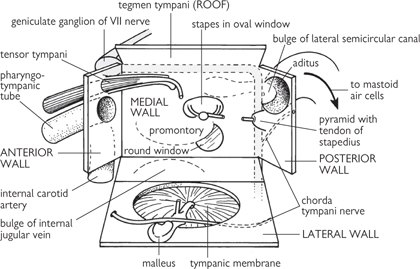

Lies within the petrous temporal bone, and comprises the vertical tympanic cavity which is fluted at its upper end as the epitympanic recess.

The oval and round windows (fenestra ovale and rotundum) provide connections with the inner ear. Three articulated bones (the ossicles) are present:

• The malleus (hammer), connected to the tympanic membrane articulates with

• The incus (anvil) which in turn articulates with

• The stapes (stirrup) which is attached to the oval window.

The chain of synovial joints transmits vibration from the tympanic membrane to the oval window. The tensor tympani muscle dampens vibrations of the tympanic membrane; stapedius limits vibration of the stapes.

The tympanic cavity is continuous with the nasal cavity through the bony and then cartilaginous auditory tube, which is lined by mucosa. This connection equalizes the pressure in the middle ear with the atmospheric pressure.

Within the petrous temporal bone, which comprises a bony labyrinth lined with endosteum and filled with perilymph (continuous with CSF through the perilymphatic duct—the aqueduct of the cochlea).

Within the bony labyrinth lies a membranous labyrinth, filled with endolymph, which resembles intracellular fluid. The bony labyrinth comprises:

• The cochlea, containing the organ of hearing

• The vestibule and semi-circular canals, for perception of orientation.

The cochlea makes 2.5 turns around the central modiolus in which the cochlear nerve travels. The vestibule is continuous with the cochlea and with the three semi-circular canals which lie perpendicular to each other. The aqueduct of the vestibule reaches the posterior cranial fossa at the internal auditory meatus.

The membranous labyrinth forms a series of ducts and sacs. The spiral cochlear duct (scala media) is wedge-shaped. It defines two channels—the vestibular and tympanic canals—which meet at the tip of the cochlea.

• The vestibular membrane separates the duct from the vestibular canal

• The basilar membrane separates the duct from the tympanic membrane.

Vibrations of the oval window initiate vibrations of the perilymph in the canals and then of the endolymph in the duct. The organ of Corti lies on the basilar membrane and detects these vibrations.

The three semi-circular canals contain semi-circular ducts; these are enlarged to form ampullae, where they join with a sac-like structure, an otolith organ (the utricle). The utricle is continuous with the other otolith organ, the saccule, which in turn is continuous with the cochlear duct.

Endolymph within this network is reabsorbed into the bloodstream from the endolymphatic duct within the aqueduct of the vestibule.

Fig. 11.33 Anterior view of right middle ear cavity showing ossicles.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p134 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.34 Walls of the middle ear in the form of an opened-out box. The incus is not shown.

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p134 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

Fig. 11.35 Inner ear with sectional views of a semicircular canal (left) and the cochlea (right).

Reproduced from Mackinnon, Pamela and Morris, John, Oxford Textbook of Functional Anatomy, vol 3, p136 (Oxford, 2005). With permission of OUP.

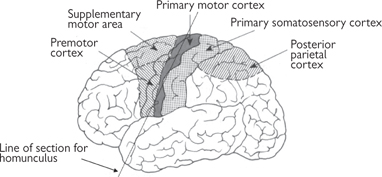

The structures of the CNS can be grouped as:

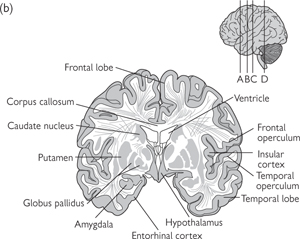

• The cerebrum comprises two lateral cerebral hemispheres, defining a horizontal fissure but connected by white matter, the corpus callosum. Each hemisphere extends from frontal to occipital bones. It lies above the anterior and middle cranial fossa and then above the tentorium cerebelli. The falx cerebri descends into the horizontal fissure

• The frontal lobe is the largest component and is separated from the parietal lobe by the central sulcus. The lateral sulcus separates the temporal lobe from the parietal and frontal lobes. The parietal lobe is separated from the most caudal cerebrum, the occipital lobe, by the parieto-occipital sulcus

• Grey matter (cell bodies and myelinated axons) on the surface of the cerebrum constitutes the cortex. A central mass of white matter (largely myelinated axons) lies within and contains a number of clusters of grey matter (basal ganglia or nuclei). These nuclei are:

• The corpus striatum, situated laterally to the thalamus and composed of the caudate and lentiform nuclei

• The amygdaloid nucleus, situated in the temporal lobe

• The claustrum, lateral to the lentiform nucleus

• Within the white matter, a fan of nerve fibres (the corona radiata) runs between the cortex and the brainstem. The lateral ventricles located within each hemisphere are continuous with the third ventricle within the thalamus via the interventricular foramina, which in turn communicates with the fourth ventricle anterior to the cerebellum via the cerebral aqueduct.

• The largely inaccessible diencephalon comprises the ovoid dorsal thalamus and ventral hypothalamus. The thalamus is formed of grey matter and is expanded at its posterior end as the pulvinar. The subthalamus contains cranial parts of the substantia nigra and red nucleus. The epithalamus contains the habenular nuclei and the pineal gland

• The hypothalamus is located between the optic chiasma and the caudal border of the mammillary bodies. It consists of a number of interposed clusters of cells (the hypothalamic nuclei) which include the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei.

Fig. 11.36 Median sagittal section of the brain to show the third ventricle, the cerebral aqueduct, and the fourth ventricle.

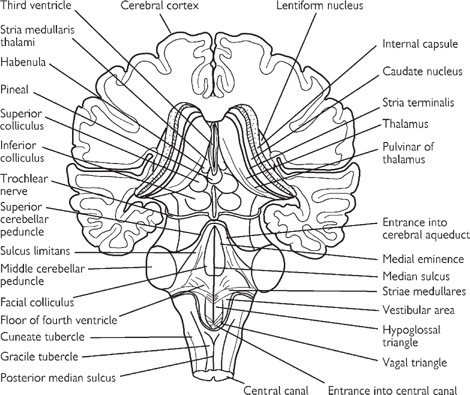

Fig. 11.37 Posterior view of the brainstem showing the two superior and the two inferior colliculi of the tectum of the midbrain.

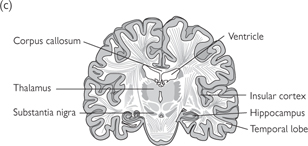

Fig. 11.38 Some structures of the cerebral hemispheres cannot be seen from the surface of the brain. For example, the basal ganglia (caudate nucleus and globus pallidus) and insular cortex can be seen only after the brain has been sectioned. Large cavities in the brain called ventricles are filled with CSF.

The midbrain, or mesencephalon, connects the forebrain to the hindbrain and contains the cerebral aqueduct.

• Posterior to the aqueduct lies the tectum, the surface of which demonstrates four raised structures—the superior and inferior colliculi

• The cerebral peduncles, comprising the anterior crus cerebri and the posterior tegmentum, lie anterior to the aqueduct

• The anterior and posterior components are separated by the substantia nigra

• At the level of the superior colliculus, the tegmentum contains the red nucleus.

• The hindbrain, or rhombencephalon, comprises:

• The medulla oblongata (or myelencephalon) connects the superior pons to the inferior spinal cord. The anterior surface has a median fissure, on either side of which is a pyramid. Posterior to the pyramids are the bulges of the olivary nuclei (the olives). The cerebellum is connected to the medulla by the inferior cerebellar peduncles, which lie posterior to the olives

• The posterior aspect of the medulla shows medial gracile tubercles of the gracile nucleus and the laterally placed cuneate tubercles of the cuneate nucleus

• The pons (or metencephalon) lies inferior to the midbrain, superior to the medulla, and on the anterior surface of the cerebellum. It contains transverse fibres connecting the two hemispheres of the cerebellum

Fig. 11.39 Several brain regions are shown in these sections of the human brain.

The sections are from rostral (a) to caudal (d) and the approximate location of these sections are shown on the lateral surface view of the brain shown above.

Reproduced with permission from Kandel ER et al. (2000). Principles of Neural Science, 4th edn. ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

• The cerebellum is situated posterior to the medulla and pons, within the posterior cranial fossa. Two hemispheres are united in the midline by the vermis. Superior and middle cerebral peduncles provide connections to the midbrain. The cerebellum displays a highly ridged cortex of grey matter within which lies white matter. Cerebellar nuclei of grey matter are situated within the white matter, comprising the dentate, emboliform, globose, and fastigial nuclei.

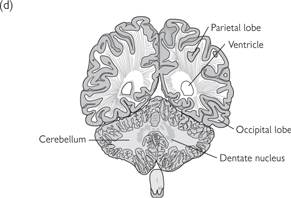

• The spinal cord arises from the medulla and runs from the foramen magnum to the lower border of the first lumbar vertebra. It is cylindrical and lies within the vertebral canal defined by the vertebral column. An outer coat of white matter (in anterior, lateral, and posterior columns) envelopes an inner core of grey matter. The grey matter defines a cross shape, with anterior and posterior horns

• Cervical (C7–8) and lumbosacral (L4–5) enlargements occur at the points at which the cervical plexus and lumbosacral plexus arise. At its termination, the spinal cord tapers into the conus medullaris. There is a deep anterior median fissure and a shallower posterior median sulcus along the longitudinal length of the cord. Thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves arise along the cord as anterior (motor) and posterior (sensory) roots. Posterior roots display a posterior root ganglion

Fig. 11.40 Main divisions of the central nervous system.

Fig. 11.41 Transverse section through lumbar part of spine: (a) oblique view; (b) face view, showing anterior and posterior roots of a spinal nerve.

There are approximately 1020 neurones in the human nervous system, of which 1011 are in the brain. The basic morphology of a neurone consists of a cell soma, from which arise a dendritic tree and an axon. Different types of neurone can be distinguished by morphology, especially in the number and configuration of the neurone’s processes.

• Comprises branch-like processes (dendrites) containing cytoskeletal elements radiating from the cell soma

• Accounts for up to 90% of the neurone’s surface area and is the main region for receiving synapses from other neurones

• Dendrites may be spiny (e.g. pyramidal cells) or non-spiny (e.g. most interneurones)

• Spines are the primary region for receiving excitatory input; each spine generally contains one asymmetrical synapse (under electron microscopy synapses are asymmetrical and excitatory, or symmetrical and inhibitory)

• Dendrites cannot propagate action potentials, but Ca2+ signalling may be involved in dendritic processing of incoming information.

• Contains most of the neurone’s organelles (nucleus, Golgi apparatus, rough ER, and mitochondria, plus neurofilaments and microtubules)

• Macromolecules required in the rest of the neurone are synthesized in the cell soma and transported by axoplasmic transport

• Receives very few synapses compared with dendrites

• Contains the axon hillock (where the axon arises from the soma) which is the point where action potentials are initiated for propagation along the axon (i.e. where integration of synaptic signals occurs).

• Carries the output of the neurone to other neurones or to effector organs (e.g. muscle and glands)

• Contains smooth ER and a prominent cytoskeleton

• Is of variable length and is generally unmyelinated when short, as in local circuit neurones (e.g. inhibitory interneurones), and myelinated in longer neurones

• Myelination increases the speed of action potential propagation

• All axons are sheathed by Schwann cells (PNS) or oligodendrocytes (CNS), whether myelinated or not

• Several branches arise at end of axon, the telodendria, each with one or more synaptic boutons containing synaptic vesicles for storing neurotransmitter

• The number and form of the branches of the telodendria depends on the type of neurone

• In local circuit neurones there can be many short axonal collaterals, while in neurones projecting to subcortical centres, such as motor neurones that extend axons to the ventral horn of the spinal cord, there is a single long axon to the distant site with a small number of recurrent collaterals

Most nervous system cells are multipolar (cell body gives rise to several processes—an axon and multiple dendrites) Cell bodies of bipolar neurones (e.g. retinal bipolar cells and dorsal root ganglion cells) give rise to two processes (one true axon and one which eventually branches forming dendrites).

Bipolar cells form no synapses on their cell body.

Unipolar cells have a single process from the soma, and are occasionally found in the ganglia of the autonomic system, but generally are only found in invertebrates.

• The main type of excitatory neurone in the brain

• All cortical output is carried in pyramidal cell axons

• Roughly pyramidal cell soma, the axis of which lies perpendicular to the cortical surface

• Dendrites are either short and arise from the base of the cell soma, or long and arise from the apex

• Form of the dendritic tree and axonal projections depends on the laminar location of the cell soma

• The pyramidal cells of cortical layer V and deep in layer III have extensive dendritic trees, and axons that project to distant cortical and (layer V only) subcortical sites (e.g. basal ganglia, brain stem and spinal cord)

• Pyramidal cells of cortical layers II and III have a small soma and dendritic tree, and their axon gives rise to many recurrent collaterals that extend into neighbouring areas of the cortex, thus providing a major intrinsic excitatory input to other cortical areas.

• Glutaminergic neurones, which are another main source of intrinsic excitatory input

• Found mostly in cortical layer IV of primary sensory areas

• High density of dendritic spines

• Influence extends only locally through small dendritic and axonal trees

• Suggested role in local cortical circuits between the neurones in layer IV that receive thalamic input, and neurones in layers III, V, and VI which carry the cortical output.

• Majority of other interneurones are GABAergic and inhibitory

• Regulate pyramidal cell function (GABA antagonists such as picrotoxin are potent convulsants)

• Many subtypes distinguishable by their morphology

• Basket cells, axonal endings of which form a ‘basket’ around the somas of pyramidal cells with which they synapse. They synapse with many pyramidal cells as their axons extend horizontally for up to 2mm across cortex; several basket cells may contribute to a single pyramidal cell’s ‘basket’

• Chandelier cells, which have characteristic axonal endings that consist of a string of synaptic boutons spread along the distal segment of the axon forming axo-axonal synapses with pyramidal cells and can inhibit pyramidal cell firing

• Double bouquet cells, which have strictly vertically oriented dendritic and axonal trees which thus extend little into neighbouring areas of cortex. Their axons form tight bundles that project across cortical layers II–V and their axonal terminals contain a wide range of neurotransmitters

• Chandelier and double bouquet cells vary morphologically depending on their connectivity and cortical location.

• Found only in the cerebellar cortex

• Characteristic dendritic tree—highly branched and in only two dimensions like the veins on a pressed leaf

• The dendritic trees of all Purkinje cells are aligned in parallel across the whole of cerebellar cortex.

Glia are a relatively poorly understood part of the CNS. From the Greek word for glue, since it was originally thought that their role was simply to glue the brain together, ‘glia’ is an umbrella term for all the non-neuronal cell types in the CNS. In fact, the different types of glial cell have widely differing morphologies and functional roles which extend far beyond simply providing neuronal scaffolding. There are two major classes of glia: macroglia and microglia.

• Derived embryologically from precursor cells that line the neural tube constituting the inner surface of the brain

• Comprise astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and ependymal cells.

• Irregular star-shaped cells, often with relatively long processes

• Make up between 20% and 50% of the CNS by volume

• Subdivided into fibrous astrocytes, which are found among bundles of myelinated fibres in CNS white matter, and protoplasmic astrocytes, which contain less fibrous material and are found around cell bodies, dendrites and synapses in the grey matter

• Embryonically, astrocytes develop from radial glial cells, which provide the framework for the migration of neurones and their subsequent organization, and thus play a critical role in defining the cytoarchitecture of the CNS. Once the CNS has matured, radial glial cells retract their processes and serve as progenitors of astrocytes. Some specialized astrocytes retain their radial morphology in the adult cerebellum (Bergmann glial cells) and the retina (Müller cells)

• Astrocytes have multiple roles in the CNS:

• Isolation of the brain parenchyma: the glia limitans is formed by long processes projecting to the pia mater and the ependyma, and astrocytes processes ensheath capillaries and the nodes of Ranvier. However, astrocytes do not themselves form the blood–brain barrier, but induce and maintain the tight junctions between the endothelial cells that create the barrier. Astrocytes are a major source of extracellular matrix proteins and adhesion molecules in the CNS that help to maintain connections between nerve cells

• CNS homeostasis: astrocytes are connected to each other by gap junctions, forming a syncytium that allows ions and small molecules to diffuse across the brain parenchyma. Astrocyte processes around synapses are thought to be important for removing transmitters from the synaptic cleft. They contain transport proteins for the reabsorption of many neurotransmitters, such as glutamate. Glutamate is converted into glutamine by astrocytes and then released into the extracellular space. Glutamine is taken up by neurones as a precursor for both glutamate and GABA

• Astrocyte processes come into close apposition with the axonal membrane at the nodes of Ranvier. Astrocyte membranes seem to act as perfect K+ electrodes, and their resting potential is determined purely by their high permeability to K+. They are thus able to buffer excess K+ released by neurones when their activity is high. There is a greater concentration of K+ channels at the end-feet of astrocyte processes, which contact blood vessels and the pial membrane, than at any other point on their surface membrane. So they can balance out high K+ uptake in one part of the cell, in an area of high neuronal activity, by extruding it through their end-feet. High K+ concentrations are also distributed further across the parenchyma via the syncytial gap junctions between neighbouring astrocytes. Furthermore, a raised K+ concentration in the extracellular space between the capillaries and the astrocyte end-feet causes local vasodilation, thus providing a mechanism for autoregulation of the blood flow to maintain appropriate oxygen and nutrient delivery

• Response to infection and injury: astrocytes have been shown to react with T lymphocytes, whose activity they can stimulate or suppress. Astrocytes therefore qualify as inducible, facultative antigen-presenting cells. In addition, they help microglia remove neuronal debris and seal off damaged brain tissue after injury

• Production of growth factors: astrocytes produce a great many growth factors, which act singly or in combination to regulate selectively the morphology, proliferation, differentiation, or survival, or all four, of distinct neuronal subpopulations. Most of the growth factors also act in a specific manner on the development and functions of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. The production of growth factors and cytokines by astrocytes and their responsiveness to these factors are a major mechanism underlying the developmental function and regenerative capacity of the CNS. The growth factors are also important for angiogenesis, again especially in development and repair of the CNS. This role is poorly understood.

• Form sheaths around nerve axons, like Schwann cells in the PNS. However, unlike Schwann cells, which sheathe single axons, the pressure for space in the CNS means that oligodendrocytes sheathe several axons. Around larger diameter fibres the sheath is myelinated to increase the speed of axonal transmission with nodes of Ranvier at regular intervals of 1mm in most nerve fibres. Around smaller diameter fibres oligodendrocytes do not produce myelin. How the CNS determines which fibres will be myelinated is not well understood. The signal between nerve axons and myelin-producing glia is thought to occur early in development. Schwann cells that do not produce myelin in their normal environment can if ‘transplanted’, so the neurones appear to provide the switch signal

• Mammalian CNS does not regenerate well. CNS neurones can regenerate in an environment provided by Schwann cells, however. During the regeneration of the PNS, Schwann cells act as a conduit for regenerating axons to grow along, and also attract neurones to grow towards them from a distance. Thus it appears to be an inhibitory influence from oligodendrocytes that prevents regeneration, although the role and mechanism is not understood.

• Line the inner surface of the brain in the ventricles

• No known physiological role.

• Develop from bone-marrow-derived monocytes that enter the brain parenchyma during early stages of brain development

• Numerous processes extending symmetrically from a small rod-shaped cell body

• Primary function is as immune response mediators in the CNS

• Most are derived from monocytes early during brain development—they retain the ability to divide and have the immunophenotypic properties of monocytes and macrophages

• Respond rapidly to immune activation or injury in the CNS, and play a role in the immune-mediated response itself and also in scavenging debris from dying cells

• Reactive microglia divide more rapidly than resting microglia, and differ both in their morphology and in the increased expression of monocyte-macrophage molecules

• Also thought to secrete cytokines and growth factors that are important in fibre-tract development, gliogenesis, and angiogenesis.

CNS neurones often form up to 10 000 synapses, rather than the single synapse that a motor neurone forms at the NMJ. However, activation of any single synapse is not sufficient to trigger a neurone to fire. Instead, excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (epsps and ipsps) from each of the many synapses over the neurone’s dendrites are summed together over time and space (known as temporal and spatial summation;  see pp.232–234). The point where the cell body meets the axon is called the axon hillock, and it is here that action potentials are triggered, if the sum total of the depolarization over the neurone’s dendritic tree is great enough.

see pp.232–234). The point where the cell body meets the axon is called the axon hillock, and it is here that action potentials are triggered, if the sum total of the depolarization over the neurone’s dendritic tree is great enough.

There are many more neurotransmitters in the CNS than in the PNS and they can be:

• Ionotropic channel (directly-gated):

• Glutamate (NMDA and quisqualate A AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid))

Metabotropic channel (indirectly gated via a G protein):

• Glutamate (quisqualate B AMPA)

• Adrenaline and noradrenaline

• Various neuropeptides such as substance P and opioids such as enkephalin ( see p.746).

see p.746).

• Glutamate is the most widespread excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS. Glutamate receptors have been typed as either AMPA or NMDA receptors, named after the agonists that were first used to distinguish them

• There are three subtypes of AMPA receptor:

• Kainate receptors are directly-gated Na+- and K+-permeable cation channels

• Quisqualate activates both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors, thus:

The quisqualate A receptor is a directly gated Na+ and K+ channel,

The quisqualate A receptor is a directly gated Na+ and K+ channel,

The quisqualate B receptor is G-protein coupled and opens a Na+ and K+ channel via a phosphoinositide-linked second-messenger system (IP3)

The quisqualate B receptor is G-protein coupled and opens a Na+ and K+ channel via a phosphoinositide-linked second-messenger system (IP3)

• The NMDA receptor is a cation channel that is permeable to Ca2+ ions in addition to Na+ and K+. The main effect of the NMDA receptor appears to be Ca2+-mediated, however, since they make little contribution to the EPSP when the neuronal membrane is at resting potential, when extracellular Mg2+ blocks the NMDA receptor channel. As the membrane becomes depolarized, the Mg2+ is removed and the channel can open, allowing Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions through. Thus, in effect, the NMDA receptor is both ligand- and voltage-gated

• NMDA receptors have been implicated in the excitotoxicity that occurs following stroke or ischaemia, and in persistent seizures in status epilepticus. Excessive influx of Ca2+ ions through NMDA receptors, caused by the continuously elevated glutamate levels that appear to occur in these conditions, allows intracellular Ca2+ to reach catatonic levels. Cell damage and death may result from the subsequent activation of Ca2+-dependent proteases and production of toxic free radicals

• NMDA receptors play a critical role in the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP), at least in the dentate gyrus and area CA1 of the hippocampus where LTP has been most studied, and also appear to be involved in the formation of the eye-blink conditioned reflex.

• GABA and glycine are the primary inhibitory neurotransmitters of the CNS

• GABA is predominant in the brain and its main function is in local circuit interneurones, although there are also long-axoned GABAergic projection neurones

• The functional morphology of GABAergic interneurones varies widely, with their effects extending over as small an area as a single cortical column, or to regions many columns wide

• GABA receptors can be divided into ionotropic and metabotropic subtypes

• The ionotropic GABAA receptor is the most common GABA receptor and opens a Cl– anion channel. The anion selectivity is produced by positively charged amino acids positioned near the ends of the ion channel

• The metabotropic GABAB receptor is G-protein coupled and can block Ca2+ channels or activate K+ channels

• GABAA receptors also bind benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, and barbiturates, such as phenobarbital and secobarbital. The effect of GABA is allosterically modulated by benzodiazepines, increasing the frequency of channel opening, and thus also GABA-induced Cl– current

• Barbiturates act by increasing the length of time that a Cl– channel remains open. This dampening, inhibitory effect on generalized CNS activity underlies the use of benzodiazepines and barbiturates as anti-convulsants and anxiolytics

• Picrotoxin and bicuculline inhibit GABA receptor function and produce widespread and sustained seizure activity due to a generalized dampening of inhibitory synapses throughout the CNS. Penicillin inhibits GABA receptors in a similar way and, at a high enough concentration, is also a potent convulsant

• Glycine is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord. It activates a Cl– anion channel that is functionally very similar to the GABAA receptor. It is blocked by strychnine

• Glutamate and GABA metabolism is similar, since the molecules are chemically closely related and both synthesized from the same precursor, α-ketoglutarate, which is a product of the Kreb’s cycle. α-ketoglutarate is transaminated to glutamate by GABA α-oxoglutarate transaminase (GABA-T). The conversion of glutamate to GABA is catalysed by glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). GABA-T is mitochondrial, while GAD is cytosolic, and it is not clear how transport is arranged in and out of the mitochondria for vesicular storage. Once glutamate or GABA have been released into the synaptic cleft, they are deactivated by reuptake into the surrounding glia or the presynaptic neurone. There is no enzymatic deactivation in the synaptic cleft. Glutamate receptors are more densely expressed in astrocytes than in neurones. Glia convert glutamate and GABA to glutamine, which is recycled back to the presynaptic neurone

• Up- or down-regulation of transmitter release from glutaminergic and GABAergic neurones is mediated by metabotropic autoreceptors.

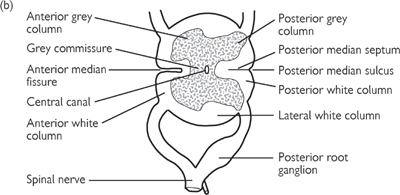

• ‘Conscious movement’ is a collective term that includes those movements that we actually think about before we carry them out, as well as those with which we are so familiar that we don't apparently think about, but that still originate from the brain (e.g. movements associated with walking— p.740). Instructions for these movements originate in the motor cortex, an area of the cerebral cortex, located just anterior to the somatosensory cortex (Fig. 11.42)

p.740). Instructions for these movements originate in the motor cortex, an area of the cerebral cortex, located just anterior to the somatosensory cortex (Fig. 11.42)

• Movement of a particular part of the body is controlled from a clearly defined area of the motor cortex—the more highly used is a particular muscle, the bigger is the area devoted to that muscle in the motor cortex

• The relative size of areas devoted to different regions of the body are often represented as a ‘map’ or motor homunculus (Fig. 11.43), distorting those areas of the body that have large areas of the cortex devoted to them so that they are considerably larger than those that are poorly represented in the motor cortex

• The motor homunculus for humans shows that most of the cortex is devoted to the hands, face, and tongue, indicative of the importance of these features to us. Different species have vastly different homunculi, which reflect those motor skills that are most important to each species.

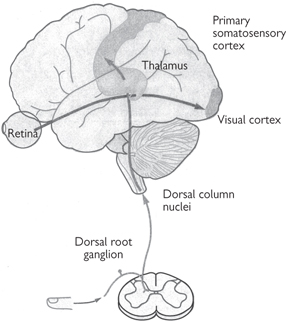

• Primary somatosensory cortex (area S1) is located on the postcentral gyrus. The representation of the body in area S1 is somatotopic, with the head represented laterally, and the feet medially. Area S1 is divisible into four distinct cytoarchitectonic areas—Brodmann’s areas 1, 2, 3a, and 3b. Although all four areas receive thalamic input, most thalamic fibres terminate in areas 3a and 3b. Areas 3a and 3b have been implicated by lesion studies in discrimination of texture, size, and shape. Cells in areas 3a and 3b then project to area 1, which is associated with texture discrimination, and area 2, which is associated with size and shape

• Each area has its own somatotopic map, in which the representations of fast and slowly adapting receptors are kept separate. Within these fast and slowly adapting regions, different receptor types are represented in separate cortical columns. Thermal and nociceptive sensitivity is usually not affected by lesions of area S1. Beyond area S1 is area S2, the secondary somatosensory cortex, which receives projections from all four areas of S1, and the posterior parietal cortex. Area S2 is involved with higher order aspects of touch, such as stereognosis, while in the posterior parietal cortex, somatosensory information is integrated with information from other sensory modalities such as vision and audition.

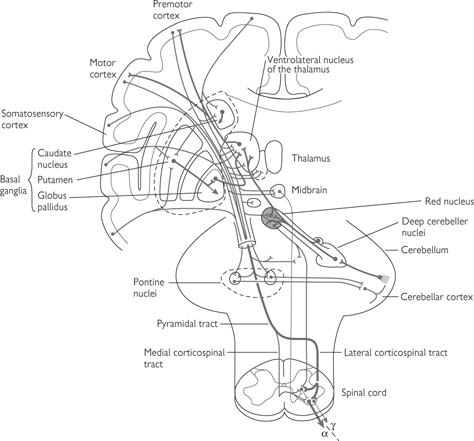

Signals originating in the motor cortex are transmitted by either the pyramidal (corticospinal) system or the extrapyramidal (extracorticospinal) system to α and γ motor neurones in the relevant segment of the spinal cord for a specific muscle.

Fig. 11.42 Location of motor cortex and associated areas of the brain.

Fig. 11.43 Motor homunculus (right hemisphere).

Reproduced with permission from Kandel E, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM (2000). Principles of Neural Science, 4th edn. © The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

• The pyramidal system (Fig. 11.44) employs a single neurone with an axon that passes all the way from the cerebral cortex to the relevant segment of the spinal cord without any intervening synapses. The nerves from the left motor cortex cross over to the right side of the spinal cord at the base of the brain, in the pyramidal decussation. Thus, the left hemisphere of the brain controls the movement of muscles on the right side and vice versa

• The extrapyramidal system (Fig. 11.45) is far more complex than the pyramidal system, largely because it includes a number of different pathways and involves a greater number of synapses. Although the extrapyramidal system is anatomically distinct from the pyramidal system, the two interact because the extrapyramidal system assimilates information from a wide range of sensory inputs, whereupon it modifies the motor signals in the pyramidal tract. For this reason, the extrapyramidal tract is seen to be central to producing smooth, controlled movements and maintaining posture. The extrapyramidal system includes nerves in the basal ganglia of the brain ( p.739), the reticular formation in the brainstem (which determines the level of consciousness—

p.739), the reticular formation in the brainstem (which determines the level of consciousness— p.771), and the brainstem nuclei.

p.771), and the brainstem nuclei.

• Lateral inhibition through inhibitory interneurones operates at all levels of the somatosensory pathways from the dorsal column nuclei upwards. Thus, secondary and tertiary afferent neurones have antagonistic centre-surround receptive fields. At each synaptic relay on the pathway, several pre-synaptic neurones converge on a single post-synaptic neurone, so that at each level, the size of the neurone’s receptive fields grows. Receptive field sizes depend on the area of the body in question, due to the density of somatic receptors. Thus, without lateral inhibition, two-point discrimination (the minimum distance between two points on the skin that can be discriminated apart) would be very poor. However, lateral inhibition at each synaptic level keeps the central, excitatory zone of the neurone’s receptive field small, so that two-point discrimination is not affected by neuronal convergence. Distal inhibition of afferent fibres by regions of cerebral cortex occurs in the thalamus, the dorsal column, and trigeminal nuclei and may contribute to selective attention.

Fig. 11.44 The pyramidal system for motor control.

Fig. 11.45 Main structures of the extrapyramidal system.

Reproduced with permission from Kandel E, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM (2000). Principles of Neural Science, 4th edn. © The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

• The thalamus (Fig. 11.46) is a bilateral structure located in the diencephalon, a brain structure found between the midbrain (the most rostral part of the brainstem) and the cerebral hemispheres

• Almost all of the sensory and motor information that reaches the cortex is processed by the thalamus. As such, it is composed of several sensory nuclei that receive input from distinct sensory stimuli such as vision, hearing, and somatic sensation. The main exception is olfaction, that has a direct pathway to the sensory cortex

• Projections from the thalamus to the sensory cortex initiate the processing of sensory information, while projections to the association cortex (a region associated with movement, perception, and motivation) initiate a behavioural response to sensory input

• Other thalamic nuclei relay information concerning motor activity to the motor cortex. For example, extrapyramidal motor information from the cerebellum and basal ganglia is relayed, via the thalamus, to the primary motor cortex

• A large fibre bundle (the internal capsule) carries thalamic projections to and from the cortex. As a consequence, the function of the thalamic nuclei is also modulated by feedback from the cortex through recurrent projections from the same cortical regions to which they project

• Nuclei within the thalamus function either as relay nuclei or diffuse projection nuclei:

• Relay nuclei generally process either sensory information resulting from a specific type of stimulus (e.g. vision, hearing, somatic sensation) or input from a particular part of the motor system. These relay nuclei send axonal projections to a region of the cerebral cortex that is also anatomically restricted and defined by the source of input it receives. For example, visual information from the retina is processed by the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and this projects to a spatially restricted region of the cortex, termed the visual cortex

• Diffuse projection nuclei are perceived to be involved in mechanisms that regulate the state of arousal of the brain. Their connections are more widespread than the relay nuclei and they include projections to other thalamic nuclei.

• Nuclei of the thalamus are anatomically divided into six groups, separated by a Y-shaped collection of fibres termed the internal medullary lamina

• Lateral, medial, and anterior nuclei are named by their location relative to this lamina, the remaining groups being the intra-laminar, reticular, and midline nuclei

• The lateral nuclei are subdivided into dorsal and ventral groups and each sub-division can be defined by its restricted connections with a specific region of the motor or sensory cortex. These relay nuclei therefore perform processing of specific sensory or motor input.

Fig. 11.46 The major subdivisions of the thalamus. The thalamus is the critical relay for the flow of sensory information to the neocortex. Somatosensory information from the dorsal root ganglia reaches the ventral posterior lateral nucleus, which relays it to the primary somatosensory cortex. Visual information from the retina reaches the lateral geniculate nucleus, which conveys it to the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobe. Each of the sensory systems, except olfaction, has a similar processing step within a distinct region of the thalamus.

Reproduced with permission from Kandel E, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM (2000). Principles of Neural Science, 4th edn. © The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

Motor signals are principally relayed by the ventral lateral and ventral anterior nuclei. The ventral lateral nucleus receives information from the cerebellum and sends axons to both the motor and premotor cortices, while the ventral anterior nucleus is innervated by the globus pallidus and projects primarily to the premotor cortex.

• Somatic sensation is processed in the ventral posterior nucleus. The lateral division of the ventral posterior nucleus receives input via the spinothalamic tract and dorsal column, whereas the medial division receives input from the sensory nuclei of the trigeminal nerve. Thus, the former is involved in processing of somatic sensation from the body, while the latter is involved in facial sensory information processing. Both nuclei project to appropriate regions in the somatosensory cortex (parietal lobe)

• The medial geniculate nucleus processes auditory information, receiving its major input from the inferior colliculus, and sends axons to the auditory cortex (temporal lobe)

• Visual processing is performed by the lateral geniculate nucleus. It receives a direct input from the retina via the optic nerve and projects to the visual cortex

• The lateral posterior and pulvinar nuclei play primary roles in the integration of sensory information by virtue of reciprocal connections between the parietal lobe and the temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes, respectively.

• The anterior group receives inputs from the hypothalamus and sends projections to the cingulate gyrus. This pathway constitutes part of the limbic system contributing to awareness and emotional aspects of sensory processing ( p.774)

p.774)

• The lateral dorsal nucleus is involved in emotional expression and receives signals from, and sends them to, the cingulate gyrus

• The medial dorsal nucleus is also involved in limbic processing, receiving input from the amygdala, hypothalamus, and olfactory system and sending axons to the prefrontal cortex.

• The thalamic midline and intra-laminar nuclei are diffuse projection nuclei receiving input from the reticular formation, hypothalamus, globus pallidus, and several cortical areas

• The reticular nucleus receives information from the cortex, other thalamic nuclei, and the brainstem. This information is largely distributed to other thalamic nuclei, where it is used in the modulation of thalamic activity.