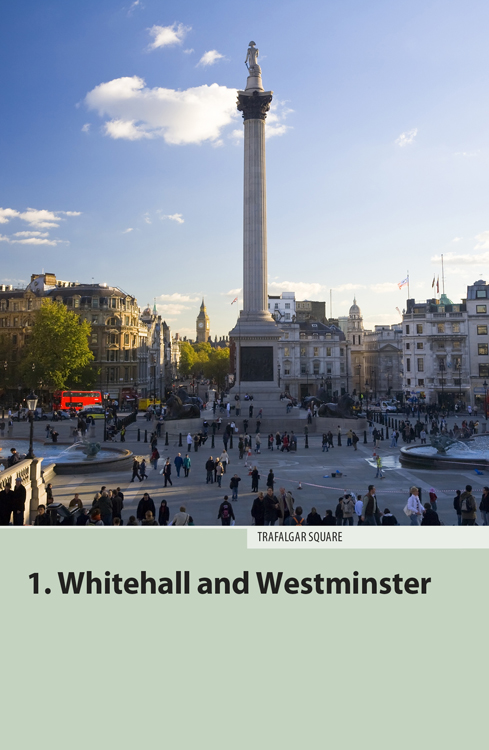

Whitehall and Westminster

The monuments and buildings in Westminster include some of London’s most famous landmarks – Nelson’s Column, Big Ben, the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey, plus two of the city’s top permanent art collections, the National Gallery and Tate Britain and its finest architectural set piece, Trafalgar Square. This is one of the easiest parts of London to walk round, with all the major sights within a mere half-mile of each other, and linked by one of London’s most triumphant – and atypical – avenues, Whitehall. However, despite the fact the area is a well-trodden tourist circuit, for the most part there are only a few shops or cafés and little commercial life (nearby Soho and Covent Garden are far better for this).

Political, religious and regal power has emanated from Whitehall and Westminster for almost a millennium. It was King Edward the Confessor (1042–66) who first established Westminster as a royal and ecclesiastical power base, some three miles west of the City of London. The embryonic English parliament used to meet in the abbey and eventually took over the old royal palace of Westminster when Henry VIII moved out to Whitehall. Henry’s sprawling Whitehall Palace burnt down in 1698 and was slowly replaced by government offices, so that by the nineteenth century Whitehall had become the “heart of the Empire”, its ministries ruling over a quarter of the world’s population. Even now, though the UK’s world status has diminished and its royalty and clergy no longer wield much real power or receive the same respect, the institutions that run the country inhabit roughly the same geographical area: Westminster for the politicians, Whitehall for the ministers and civil servants.

Trafalgar Square

![]() Charing Cross

Charing Cross

As one of the few large public squares in London, Trafalgar Square has been both a tourist attraction and the main focus for political demonstrations for over a century and a half. Nowadays, most folk come here to see Nelson’s Column, or to visit the National Gallery, though a huge range of events, commemorations and celebrations are staged here throughout the year, from St Patrick’s Day shenanigans to Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. Each December, the square is graced with a giant Christmas tree covered in fairy lights, donated by Norway in thanks for Britain’s support during World War II, and carol singers battle nightly with the traffic.

For centuries, Trafalgar Square was the site of the King’s Mews, established in the thirteenth century by Edward I, who kept the royal hawks and the falconers here (the term “mews” comes from falconry: the birds were caged or “mewed up” there whilst changing their plumage). Chaucer was Clerk of the Mews for a time, and by Tudor times there were stables here, too. During the Civil War they were turned into barracks and later used as a prison for Cavaliers. In the 1760s, George III began to move the mews to Buckingham Palace, and by the late 1820s, John Nash had designed the new square (though he didn’t live to see his plan executed). The Neoclassical National Gallery filled up the northern side in 1838, followed shortly afterwards by the central focal point, Nelson’s Column, though the famous bronze lions didn’t arrive until 1868. The development of the rest of the square was equally haphazard, though the overall effect is unified by the safe Neoclassical style of the buildings, and the square remains one of London’s grandest architectural highlights.

A HISTORY OF PROTEST

Installed in 1845 in an attempt to deter the gathering of urban mobs, the Trafalgar Square fountains have failed supremely to prevent the square from becoming a focus of political protest. The first major demo was held in 1848 when the Chartists assembled to demand universal suffrage before marching to Kennington Common. Protests were banned until the 1880s, when the emerging Labour movement began to gather here, culminating in Bloody Sunday, 1887, when hundreds of demonstrators were injured, and three killed, by the police. To allow the police to call quickly for reinforcements, a police phone box was built into one of the stone bollards in the southeast corner of the square, with a direct link to Scotland Yard.

Throughout the 1980s, there was a continuous anti-apartheid demonstration outside South Africa House, and in 1990, the square was the scene of the Poll Tax Riot, which precipitated the downfall of Margaret Thatcher. Smaller demos still take place here, but London’s largest demonstrations – like the ones against military intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan – simply pass through, en route to the more spacious environs of Hyde Park.

Nelson’s Column

Raised in 1843, and now one of London’s best-loved monuments, Nelson’s Column commemorates the one-armed, one-eyed admiral who defeated the French at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, but paid for it with his life. The sandstone statue which surmounts a 151-foot granite column is more than triple life-size but still manages to appear minuscule. The acanthus leaves of the capital are cast from British cannons, while bas-reliefs around the base – depicting three of Nelson’s earlier victories as well as his death aboard HMS Victory – are from captured French armaments. Edwin Landseer’s four gargantuan bronze lions guard the column and provide a climbing frame for kids (and demonstrators).

Keeping Nelson company at ground level, on either side of the column, are bronze statues of Napier and Havelock, Victorian major-generals who helped keep India British; against the north wall are busts of Beatty, Jellicoe and Cunningham, admirals from the last century. To the right of them are the imperial standards of length – inch, foot and yard – “accurate at 62 degrees Fahrenheit”, as the plaque says, and still used by millions of Brits despite the best efforts of the European Union. Above this is an equestrian statue of George IV (bareback, stirrup-less and in Roman garb), which he himself commissioned for the top of Marble Arch, but which was later erected here “temporarily”.

South Africa House and Canada House

There’s an unmistakable whiff of empire about Trafalgar Square, with South Africa House erected in 1935 on the east side, complete with keystones featuring African animals, and a gilded springbok. Canada House, constructed in warm Bath stone on the opposite side of the square, was built by Robert Smirke in the 1820s as a gentlemen’s club and home for the Royal College of Physicians. It retains much of its original Neoclassical interior, and is now in the hands of the Canadian High Commission.

St Martin-in-the-Fields

Trafalgar Square • Mon, Tues & Fri 8.30am–1pm & 2–6pm,

Wed 8.30am–1.15pm & 2–5pm, Thurs 8.30am–1.15pm & 2–6pm, Sat

9.30am–6pm, Sun 3.30–5pm • Free • ![]() 020 7766 1100,

020 7766 1100, ![]() stmartin-in-the-fields.org • _test777

stmartin-in-the-fields.org • _test777![]() Charing Cross

Charing Cross

At the northeastern corner of Trafalgar Square stands the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, fronted by a magnificent Corinthian portico and topped by an elaborate tower and steeple, designed in 1721 by James Gibbs – it was subsequently copied widely in the American colonies. The barrel-vaulted interior features ornate, sparkling white Italian plasterwork and is best appreciated while listening to one of the church’s free lunchtime concerts (Mon, Tues & Fri) or ticketed, candle-lit evening performances. As the official parish church for Buckingham Palace, St Martin’s maintains strong royal and naval connections – there’s a royal box on the left of the high altar, and one for the admiralty on the right. Down in the newly expanded crypt – accessible via an entrance north of the church – there’s a licensed café, shop, gallery and brass-rubbing centre.

THE FOURTH PLINTH

The fourth plinth, in the northwest corner

Trafalgar Square, was originally earmarked for an equestrian statue of

William IV. In the end, it remained empty until 1999, since when it has been

used to display works of modern sculpture, which are changed annually (![]() london.gov.uk/fourthplinth). Highlights have included: Rachel

Whiteread’s inverted plinth; Marc Quinn’s Alison Lapper

Pregnant, a nude statue of a woman without arms – a larger,

inflatable version of which appeared in the 2012 Paralympics opening

ceremony; Antony Gormley’s One & Other, where

several thousand individuals each had an hour to occupy the plinth; and

Yinka Shonibare’s Ship in a Bottle.

london.gov.uk/fourthplinth). Highlights have included: Rachel

Whiteread’s inverted plinth; Marc Quinn’s Alison Lapper

Pregnant, a nude statue of a woman without arms – a larger,

inflatable version of which appeared in the 2012 Paralympics opening

ceremony; Antony Gormley’s One & Other, where

several thousand individuals each had an hour to occupy the plinth; and

Yinka Shonibare’s Ship in a Bottle.

National Gallery

Trafalgar Square • Daily 10am–6pm, Fri till 9pm • Free • ![]() 020 7747 2885,

020 7747 2885, ![]() nationalgallery.org.uk • _test777

nationalgallery.org.uk • _test777![]() Charing Cross

Charing Cross

Taking up the entire north side of Trafalgar Square, the sprawling Neoclassical hulk of the National Gallery houses one of the world’s greatest art collections. Unlike the Louvre or the Hermitage, the National Gallery is not based on a former royal collection, but was begun as late as 1824 when the government reluctantly agreed to purchase 38 paintings belonging to a Russian émigré banker, John Julius Angerstein. The collection was originally put on public display at Angerstein’s old residence, on Pall Mall, until today’s purpose-built edifice was completed in 1838. A hostile press dubbed the gallery’s diminutive dome and cupolas “pepperpots”, and poured abuse on the Greek Revival architect, William Wilkins, who retreated into early retirement and died a year later.

The gallery now boasts a collection of more than 2300 paintings, whose virtue is not so much its size as its range, depth and quality. Among the thousand paintings on permanent display are Italian masterpieces by the likes of Botticelli, Leonardo and Michelangelo, dazzling pieces by Velázquez and Goya and an array of Rembrandt paintings that features some of his most searching portraits. In addition, the gallery has a particularly strong showing of Impressionists, with paintings by Monet, Degas, Van Gogh and Cézanne, plus several early Picassos. There are also showpieces by Turner, Reynolds and Gainsborough, but for a wider range of British art, head for Tate Britain. Special exhibitions are held in the basement of the Sainsbury Wing and usually charge admission.

INFORMATION AND TOURS

Arrival There are four entrances to the National Gallery: Wilkins’ original Portico Entrance up the steps from Trafalgar Square, the Getty Entrance on the ground floor to the east, the Sainsbury Wing to the west and the back entrance on Orange St. The Getty Entrance and the Sainsbury Wing both have an information desk, where you can buy a floorplan, and disabled access, with lifts to all floors.

Tours Audioguides (£3.50) are available – much better, though, are the gallery’s free guided tours, which set off from the Sainsbury Wing foyer (daily 11.30am & 2.30pm, plus Fri 7pm; 1hr).

Eating By the Getty Entrance is the National Café

(Mon–Fri 8am–11pm, Sat 10am–11pm, Sun 10am–6pm), which has a

self-service area, and a large brasserie, with an entrance on St

Martin’s Place. More formal dining is available at the National Dining Rooms, serving excellent British cuisine,

in the Sainsbury Wing (![]() 020 7747 2525), with views over

Trafalgar Square.

020 7747 2525), with views over

Trafalgar Square.

The Sainsbury Wing

The original design for the gallery’s modern Sainsbury Wing was dubbed by Prince Charles “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”. So instead, the American husband-and-wife team of Venturi and Scott-Brown were commissioned to produce a softly-softly, postmodern adjunct, which playfully imitates elements of William Wilkins’ Neoclassicism and even Nelson’s Column and, most importantly, got the approval of Prince Charles, who laid the foundation stone in 1988.

Chronologically the gallery’s collection begins in this wing, which houses the National’s oldest paintings from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, mostly early Italian Renaissance masterpieces, with a smattering of early Dutch, Flemish and German works.

TEN PAINTINGS NOT TO MISS

Battle of San Romano Uccello. Room 54

Arnolfini Portrait Van Eyck. Room 56

Virgin of the Rocks Da Vinci. Room 57

Venus and Mars Botticelli. Room 58

The Ambassadors Holbein. Room 4

Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 Rembrandt van Rijn. Room 23

The Cornfield Constable. Room 34

Rain, Steam & Speed Turner. Room 34

Gare St Lazare Monet. Room 43

Van Gogh’s Chair Van Gogh. Room 45

Giotto to Van Eyck

The gallery’s earliest works by Giotto, “the father of modern painting”, and Duccio, a Sienese contemporary, are displayed in room 52. So too, in a “side chapel” is the “Leonardo Cartoon” – a preparatory drawing for a painting which, like so many of Leonardo’s projects, was never completed. The cartoon was known only to scholars until the gallery bought it for £800,000 in the mid-1960s. In 1987, it gained further notoriety when an ex-soldier blasted the work with a sawn-off shotgun in protest at the political status quo.

Next door, you can admire the extraordinarily vivid Wilton Diptych, one of the few medieval altarpieces to survive the Puritan iconoclasm of the Commonwealth. It was painted by an unknown fourteenth-century artist for King Richard II, who is depicted kneeling, presented by his three patron saints to the Virgin, Child and assorted angels.

Whatever you do, don’t miss Paolo Uccello’s brilliant, blood-free Battle of San Romano, which dominates room 54. The painting commemorates a recent Florentine victory over her bitter Sienese rivals and was commissioned as part of a three-panel frieze for a Florentine palazzo. Another Florentine commission – this time from the Medicis – is The Annunciation by Fra Filippo Lippi, a beautifully balanced painting in which the poses of Gabriel and Mary carefully mirror one another, while the hand of God releasing the dove of the Holy Spirit provides the vanishing point.

Room 56 explores the beginnings of oil painting, and one of its early masters, Jan van Eyck, whose intriguing Arnolfini Portrait is celebrated for its complex symbolism. No longer thought to depict a marriage ceremony, the “bride” is not pregnant but simply wearing a fashionable dress that showed off just how much excess cloth a rich Italian cloth merchant like Arnolfini could afford.

Botticelli to Piero della Francesca

You return to the Italians in room 57, which boasts Leonardo da Vinci’s melancholic Virgin of the Rocks (the more famous Da Vinci Code version hangs in the Louvre) and two contrasting Nativity paintings by Botticelli: the Mystic Nativity is unusual in that it features seven devils fleeing back into the Underworld, while in his Adoration of the Kings, Botticelli himself takes centre stage, as the best-dressed man at the gathering, resplendent in bright-red stockings and giving the audience a knowing look. In room 58 is his Venus and Mars, depicting a naked and replete Mars in deep postcoital sleep, watched over by a beautifully calm Venus, fully clothed and somewhat less overcome.

Further on, in room 62, hangs one of Mantegna’s best early works, The Agony in the Garden, which demonstrates a convincing use of perspective. Close by, the dazzling dawn sky in the painting on the same theme by his brother-in-law, Giovanni Bellini, shows the artist’s celebrated mastery of natural light. Also in this room is one of Bellini’s greatest portraits of the Venetian Doge Leonardo Loredan. Elsewhere, there are paintings from Netherlands and Germany, among them Dürer’s sympathetic portrait of his father (a goldsmith in Nuremberg), in room 65, which was presented to Charles I in 1636 by the artist’s home town.

Finally, at the far end of the wing, in room 66, your eye will probably be drawn to Piero della Francesca’s monumental Baptism of Christ, one of his earliest surviving pictures, dating from the 1450s and a brilliant example of his immaculate compositional technique. Blindness forced Piero to stop painting some twenty years before his death, and to concentrate instead on his equally innovative work as a mathematician.

The main building

The collection continues in the gallery’s main building with paintings from the sixteenth century to the early twentieth century. This account follows the collection more or less chronologically.

HIDDEN GEMS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Wilton Diptych Room 53

An Allegory with Venus and Cupid Bronzino. Room 8

Supper at Emmaus Caravaggio. Room 32

A Young Woman standing at a Virginal Vermeer. Room 25

The Avenue at Middleharnis Hobbema Room 21

Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat Elisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun. Room 33

Marriage à la Mode Hogarth. Room 35

Portrait of Hermine Gallia Klimt. Room 44

After the Bath Degas. Room 46

Veronese, Giorgione and Titian

The first room you come to from the Sainsbury Wing is the vast Wohl Room (room 9), containing mainly large-scale sixteenth-century Venetian works. The largest of the lot is Paolo Veronese’s lustrous Family of Darius before Alexander, its array of colourfully clad figures revealing the painter’s remarkable skill in juxtaposing virtually the entire colour spectrum in a single canvas. Less prominent in this room are two perplexing paintings attributed to the elusive Giorgione, a highly original Venetian painter, only twenty of whose paintings survive. Here, too, at opposite ends of the room, are all four of Veronese’s erotic Allegories of Love canvases, designed as ceiling paintings, perhaps for a bedchamber.

More Venetian works hang in room 10, including Titian’s consummate La Schiavona, a precisely executed portrait within a portrait. His colourful early masterpiece Bacchus and Ariadne, and his much gloomier Death of Actaeon, painted some fifty years later, amply demonstrate the painter’s artistic development and longevity. The Virgin and Child is another typical late Titian, with the paint jabbed on and rubbed in.

Bronzino, Michelangelo and Raphael

In room 8, Bronzino’s strangely disturbing Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time is a classic piece of Mannerist eroticism, once owned by François I, the decadent, womanizing, sixteenth-century French king. (Incidentally, Cupid’s foot features in the opening animated titles of Monty Python’s Flying Circus.) Here too is Michelangelo’s early, unfinished Entombment, which depicts Christ’s body being carried to the tomb, and the National’s major paintings by Raphael. These range from early works such as St Catherine of Alexandria, whose sensuous serpentine pose is accentuated by the folds of her clothes, and the richly coloured Mond Crucifixion, both painted when the artist was in his 20s, to later works like Pope Julius II – his (and Michelangelo’s) patron – a masterfully percipient portrait of old age.

Holbein, Cranach, Bosch and Bruegel

Room 4 contains several masterpieces by Hans Holbein, most notably his extraordinarily detailed double portrait from the Tudor court, The Ambassadors – note the anamorphic skull in the foreground. Among the other works by Holbein is his intriguing A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, and his striking portrait of the 16-year-old Christina of Denmark, part of a series commissioned by Henry VIII when he was looking for a potential fourth wife. Look out, too, for Holbein’s contemporary, Lucas Cranach the Elder, whose Cupid Complaining to Venus is a none-too-subtle message about dangerous romantic liaisons – Venus’s wonderfully fashionable headgear only emphasizes her nakedness.

Next door, in room 5, hangs the National’s one and only work by Hieronymus Bosch, Christ Mocked, in which four manic tormentors (one wearing an Islamic crescent moon and a Jewish star) bear down on Jesus. The painting that grabs most folks’ attention, however, is Massys’s caricatured portrait of an old woman looking like a pantomime dame. Nearby, in room 14, you’ll find the gallery’s only work by Jan Bruegel the Elder, the tiny Adoration of the Kings, with some very motley-looking folk crowding in on the infant; only Balthasar looks at all regal.

BORIS ANREP’S FLOOR MOSAICS

One of the most overlooked features of the National Gallery is the mind-boggling floor mosaics executed by Russian-born Boris Anrep between 1927 and 1952 on the landings of the main staircase leading to the Central Hall. The Awakening of the Muses, on the halfway landing, features a bizarre collection of famous figures from the 1930s – Virginia Woolf appears as Clio (Muse of History) and Greta Garbo plays Melpomene (Muse of Tragedy). The mosaic on the landing closest to the Central Hall is made up of fifteen small scenes illustrating the Modern Virtues: Anna Akhmatova is saved by an angel from the Leningrad Blockade in Compassion; T.S. Eliot contemplates the Loch Ness Monster and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in Leisure; Bertrand Russell gazes on a naked woman in Lucidity; Edith Sitwell, book in hand, glides across a monster-infested chasm on a twig in Sixth Sense; and in the largest composition, Defiance, Churchill appears in combat gear on the white cliffs of Dover, raising two fingers to a monster in the shape of a swastika.

Claude, Poussin and Dutch landscapes

The English painter J.M.W. Turner left specific instructions in his will for two of his Claude-influenced paintings to be hung alongside a couple of the French painter’s landscapes. All four now hang in the octagonal room 15, and were slashed by a homeless teenager in 1982 in an attempt to draw attention to his plight. Claude’s dreamy classical landscapes and seascapes, and the mythological (often erotic) scenes of Poussin, were favourites of aristocrats on the Grand Tour, and made both artists very famous in their time. Claude’s Enchanted Castle, in particular, caught the imagination of the Romantics, allegedly inspiring Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale. Nowadays, rooms 19 and 20, which are given over entirely to these two French artists, are among the quietest in the gallery.

Of the Dutch landscapes in rooms 21 and 22, those by Aelbert Cuyp stand out due to the warm Italianate light which suffuses his works, but the finest of all is, without a doubt, Hobbema’s tree-lined Avenue at Middelharnis. The market for such landscapes at the time was limited, however, and Hobbema quit painting at the age of just 30. Jacob van Ruisdael, Hobbema’s teacher, whose works are on display nearby, also went hungry for most of his life.

Rembrandt and Vermeer

Rooms 23 and 24 feature mostly works by Rembrandt, including the highly theatrical Belshazzar’s Feast, painted for a rich Jewish patron. Look out also for two of Rembrandt’s searching self-portraits, painted thirty years apart, with the melancholic Self Portrait Aged 63, from the last year of his life, making a strong contrast to the sprightly early work. Similarly, the joyful portrait of Saskia, Rembrandt’s wife, from the most successful period of his life, contrasts with his more contemplative depiction of his mistress, Hendrickje, who was hauled up in front of the city authorities for living “like a whore” with Rembrandt. The portraits of Jacob Trip and his wife, Margaretha de Geer, are among the most honestly realistic depictions of old age in the entire gallery.

Room 25 harbours de Hooch’s classic Courtyard of a House in Delft, and a (probable) self-portrait by Carel Fabritius, one of Rembrandt’s pupils. Fabritius died in the explosion of the Delft gunpowder store, the subject of another painting in the room. Also here is the seventeenth-century van Hoogstraten Peepshow, a box of tricks that reflects the Dutch obsession of the time with perspectival and optical devices. Two typically serene works by Vermeer hang here (or in a nearby room) and provide a counterpoint to one another: each features a “young woman at a virginal”, but where she stands in one, she sits in the other; she’s viewed from the right and then the left, in shadow and then in light and so on.

Rubens

Three adjoining rooms, known collectively as room 29, are dominated by the expansive, fleshy canvases of Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish painter whom Charles I summoned to the English court. The one woman with her clothes on is the artist’s future sister-in-law, Susanna Fourment, whose delightful portrait became known as Le Chapeau de Paille (The Straw Hat) – though the hat is actually made of black felt and decorated with white feathers. At the age of 54, Rubens married Susanna’s younger sister, Helena (she was just 16), the model for all three goddesses posing in the later 1630s version of The Judgement of Paris. Also displayed here are Rubens’ rather more subdued landscapes, one of which, the View of Het Steen, shows off the very fine prospect from the Flemish country mansion Rubens bought in 1635.

Velázquez, El Greco, Van Dyck and Caravaggio

The cream of the National Gallery’s Spanish works are displayed in room 30, among them Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, one of the gallery’s most famous pictures. Velázquez is thought to have painted just four nudes in his lifetime, of which only the Rokeby Venus survives, an ambiguously narcissistic image that was slashed in 1914 by suffragette Mary Richardson, in protest at the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst.

Another Flemish painter summoned by Charles I was Anthony van Dyck, whose Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, in room 31, is a fine example of the work that made him a favourite of the Stuart court, romanticizing the monarch as a dashing horseman. Nearby is the artist’s double portrait of Lord John and Lord Bernard Stuart, two dapper young cavaliers about to set out on their Grand Tour in 1639, and destined to die fighting for the royalist cause shortly afterwards in the Civil War.

Caravaggio’s art is represented in the vast room 32 by the typically salacious Boy Bitten by Lizard, and the melodramatic Supper at Emmaus. The latter was a highly influential painting: never before had biblical scenes been depicted with such naturalism – a beardless and haloless Christ surrounded by scruffy disciples. At the time it was deemed to be blasphemous, and, like many of Caravaggio’s religious commissions, was eventually rejected by the customers. One of the most striking paintings in this room is Giordano’s Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone, in which the hero is dramatically depicted in sapphire blue, with half the throng already petrified.

British art 1750–1850

When the Tate Gallery opened in 1897, the vast bulk of the National’s British art was transferred there, leaving just a few highly prized works behind. Among these are several superb late masterpieces by Turner, two of which herald the new age of steam: Rain, Steam and Speed and The Fighting Temeraire, in which a ghostly apparition of the veteran battleship from Trafalgar is pulled into harbour by a youthful, fire-snorting tug, a scene witnessed first-hand by the artist in Rotherhithe. Here, too, is Constable’s Hay Wain, painted in and around his father’s mill in Suffolk, as is the irrepressibly popular Cornfield. There are landscapes, as well as the portraits, by Thomas Gainsborough – his feathery, light technique is seen to superb effect in Morning Walk, a double portrait of a pair of newlyweds. Joshua Reynolds’ contribution is a portrait, Lady Cockburn and her Three Sons, in which the three boys clamber endearingly over their mother. And finally, the most striking portrait in the whole room is George Stubbs’ pin-sharp depiction of the racehorse Whistlejacket rearing up on its hindlegs.

More works by Gainsborough and Reynolds hang in room 35, including the only known self-portrait of the former with his family, painted in 1747 when he was just 20 years old. On the opposite wall are the six paintings from Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode, a witty, moral tale that allowed the artist to give vent to his pet hates: bourgeois hypocrisy, snobbery and bad (ie Continental) taste. In the ornate, domed Central Hall (room 36) hangs Reynolds’ dramatic portrait of the extraordinarily effeminate Colonel Tarleton.

French art 1700–1860

The large room of British art (room 34) is bookended with two small rooms of French art. In room 33, among works by the likes of Fragonard, Boucher and Watteau, there’s a portrait of Louis XV’s mistress in the year of her death and a spirited self-portrait by the equally well-turned-out Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, one of only three women artists in the National Gallery.

In room 41, the most popular painting is Paul Delaroche’s slick and pretentious Execution of Lady Jane Grey, in which the blindfolded, white-robed, 17-year-old queen stoically awaits her fate. Look out, too, for Gustave Courbet’s languorous Young Ladies on the Bank of the Seine, innocent enough to the modern eye, scandalous when it was first shown in 1857 due to the ladies’ “state of undress”.

Impressionism and beyond

Among the gallery’s busiest section are the four magnificent rooms (43–46) of Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings, where rehangings are frequent. The National boasts several key works by Manet, including his famous Music in the Tuileries Gardens, and the unfinished Execution of Maximilian, one of three versions he painted. There are also canvases from every period of Monet’s long life: from early works like The Thames below Westminster and Gare St Lazare to the late, almost abstract paintings executed in his beloved garden at Giverny.

Other major Impressionist works include Renoir’s Umbrellas, Seurat’s classic pointillist canvas, Bathers at Asnières – one of the National’s most reproduced paintings – and Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre at Night. There are also several townscapes from Pissarro’s period of exile, when he lived in south London, during the Franco-Prussian War. There’s a comprehensive showing of Cézanne with works spanning the great artist’s long life. The Painter’s Father, one of his earliest extant works, was originally painted onto the walls of his father’s house outside Aix. The Bathers, by contrast, is a late work, whose angular geometry exercised an enormous influence on the Cubism of Picasso and Braque.

Van Gogh’s famous, dazzling Sunflowers hangs here, the beguiling Van Gogh’s Chair, dating from his stay in Arles with Gauguin, and Wheatfield with Cypresses, which typifies the intense work he produced shortly before his suicide. Finally, look out for Picasso’s sentimental Blue Period Child with a Dove; Rousseau’s imagined junglescape, Surprised!; Klimt’s Hermine Gallia, in which the sitter wears a dress designed by the artist; and a trio of superb Degas canvases: Miss La-La at the Cirque Fernando, the languorous pastel drawing After the Bath and the luxuriant La Coiffure.

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin’s Place • Daily 10am–6pm, Thurs & Fri till 9pm • Free • ![]() 020 7306 0055,

020 7306 0055, ![]() npg.org.uk • _test777

npg.org.uk • _test777![]() Charing Cross

Charing Cross

Around the east side of the National Gallery lurks the National Portrait Gallery founded in 1856 to house uplifting depictions of the good and the great. Though it undoubtedly has some fine works among its collection of over ten thousand portraits, many of the studies are of less interest than their subjects. Nevertheless, it’s interesting to trace who has been deemed worthy of admiration at any one time: aristocrats and artists in previous centuries, warmongers and imperialists in the early decades of the twentieth century, writers and poets in the 1930s and 1940s. The most popular part of the museum by far is the contemporary section, where the whole thing degenerates into a sort of thinking person’s Madame Tussauds, with photos and portraits of today’s celebrities. However, the special exhibitions (for which there is often a charge) are well worth seeing – the photography shows, in particular, are often excellent.

INFORMATION

Arrival There are two entrances to the NPG: disabled access is from Orange St, while the main entrance is on St Martin’s Place. Once inside, head straight for the Ondaatje Wing, where there’s an information desk – you can pick up an audioguide (£3.50) which gives useful biographical background on many of the pictures.

Eating There’s a little café in the basement, and the excellent but pricey

rooftop Portrait restaurant on Floor 3, with

incredible views over Trafalgar Square (![]() 020 7312

2490).

020 7312

2490).

The Tudors and Stuarts

To follow the collection chronologically, take the escalator to the trio of Tudor Galleries, on Floor 2. Here, you’ll find Tudor portraits of pre-Tudor kings as well as Tudor personalities: a stout Cardinal Wolsey looking like the butcher’s son he was and the future Bloody Mary looking positively benign in a portrait celebrating her reinstatement to the line of succession in 1544. Pride of place goes to Holbein’s larger-than-life cartoon of Henry VIII, showing the king as a macho buck against a modish Renaissance background, with his sickly son and heir, Edward VI, striking a deliberately similar pose close by. The most eye-catching canvas is the anamorphic portrait of Edward, an illusionistic painting that must be viewed from the side.

Also displayed here are several classic propaganda portraits of the formidable Elizabeth I and her dandyish favourites. Further on hangs the only known painting of Shakespeare from life, a subdued image in which the Bard sports a gold-hoop earring; appropriately enough, it was the first picture acquired by the gallery. To keep to the chronology, you must turn left here into room 5, where the quality of portraiture goes up a notch thanks to the appointment of Van Dyck as court painter. Among all the dressed-to-kill Royalists in room 5, Oliver Cromwell looks dishevelled but masterful, while an overdressed, haggard Charles II hangs in room 7 alongside his long-suffering Portuguese wife and several of his mistresses, including the orange-seller-turned-actress Nell Gwynne.

The eighteenth century

The eighteenth century begins in room 9, with members of the Kit-Kat Club, a group of Whig patriots, painted by one of its members, Godfrey Kneller, a naturalized German artist, whose self-portrait can be found in room 10. Next door, room 11 contains a hotchpotch of visionaries including a tartan-free Bonnie Prince Charlie and his saviour, the petite Flora MacDonald. In room 12 there are several fine self-portraits, including a dashing one of the Scot Allan Ramsay. Room 14 is dominated by The Death of Pitt the Elder, who collapsed in the House of Lords having risen from his sickbed to try and save the rebellious American colonies for Britain – despite the painting’s title, he didn’t die for another month.

In room 17, you’ll find a bold likeness of Lord Nelson, unusually out of uniform, along with an idealized portrait of Nelson’s mistress, Lady Emma Hamilton, painted by the smitten George Romney. Also here is a portrait of George IV and the twice-widowed Catholic woman, Maria Fitzherbert, whom he married without his father’s consent. His official wife, Queen Caroline, is depicted at the adultery trial at which she was acquitted, and again, with sleeves rolled up, ready for her sculpture lessons, in an audacious portrait by Thomas Lawrence, who was called to testify on his conduct with the queen during the painting of the portrait.

The Romantics dominate room 18, with the ailing John Keats painted posthumously by Joseph Severn, in whose arms he died in Rome. Elsewhere, there’s Lord Byron in Albanian garb, an open-collared Percy Bysshe Shelley, with his wife, Mary, nearby, and her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, opposite.

The Victorians

Down on the first floor, the Victorians feature rather too many stuffy royals, dour men of science and engineering, and stern statesmen such as those lining the corridor of room 22. Centre stage, in room 21, is a comical statue of Victoria and Albert in Anglo-Saxon garb. The best place to head for is room 24, which contains a deteriorated portrait of the Brontë sisters as seen by their disturbed brother Branwell; you can still see where he painted himself out, leaving a ghostly blur between Charlotte and Emily. Nearby are the poetic duo, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, looking totally Gothic in their grim Victorian dress.

In room 28, it’s impossible to miss the striking Edwardian portrait of Lady Colin Campbell, posing in a luxuriant black silk dress. Finally, in room 29, there are some excellent John Singer Sargent portraits, and several works by students of the Slade: Augustus John, looking very confident and dapper at the age of just 22, his sister, Gwen John, Walter Sickert (by Philip Wilson Steer) and Steer (by Sickert). Steer founded the New English Arts Club, at which the last two portraits were originally exhibited.

The twentieth century and beyond

The twentieth-century collection begins in room 30, with Sargent’s group portrait of the upper-crust generals responsible for the slaughter of World War I. The interwar years are then generously covered in room 31. The faces on display here are frequently rotated, but look out for Sickert’s excellent small, smouldering portrait of Churchill, Augustus John’s portrayal of a ruby-lipped Dylan Thomas, Ben Nicolson’s double portrait of himself and Barbara Hepworth and a whole host of works by, or depicting, the Bloomsbury Group.

Out on the Balcony Gallery, there’s a who’s who (or was who) of Britain 1960–90. Even here, amid the photos of the Swinging Sixties, there are quite a few genuine works of art by the likes of Leon Kossoff, R.B. Kitaj, Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon. The Contemporary Galleries occupy the ground floor, and are a constantly changing, unashamedly populist trot through the media personalities of the last decade or so. As well as a host of photo portraits, you can sample such delights as Michael Craig Martin’s LCD portrait of architect Zaha Hadid, or the cartoon-like quadruple portrait of pop band Blur by Julian Opie.

Whitehall

Whitehall, the unusually broad avenue connecting Trafalgar Square to Parliament Square, is synonymous with the faceless, pinstriped bureaucracy charged with the day-to-day running of the country. Yet during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was, in fact, the site of the chief royal residence in London. Whitehall Palace started out as the London seat of the Archbishop of York, but was confiscated and enlarged by Henry VIII after a fire at Westminster Palace forced the king to find alternative accommodation; it was here that he celebrated his marriage to Anne Boleyn in 1533, and here that he died fourteen years later. Described by one contemporary chronicler as nothing but “a heap of houses erected at diverse times and of different models, made continuous”, it boasted some two thousand rooms and stretched for half a mile along the Thames. Very little survived the fire of 1698 and, subsequently, the royal residence shifted to St James’s and Kensington.

Since then, all the key governmental ministries and offices have migrated here, rehousing themselves on an ever-increasing scale. The Foreign & Commonwealth Office, for example, occupies a palatial Italianate building, built by George Gilbert Scott in 1868, and well worth a visit on Open House weekend. The process reached its apogee with the grimly bland Ministry of Defence (MoD) building, completed in 1957, underneath which is Britain’s most expensive military bunker, the £125 million Pindar.

Banqueting House

Whitehall • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • £5 • ![]() 020 3166 6000,

020 3166 6000, ![]() hrp.org.uk • _test777

hrp.org.uk • _test777![]() Charing Cross

Charing Cross

The only sections of Whitehall Palace to survive the 1698 fire were Cardinal Wolsey’s wine cellars (now beneath the Ministry of Defence) and Inigo Jones’s Banqueting House, the first Palladian (or Neoclassical) building to be built in central London. Opened in 1622 with a performance of Ben Jonson’s Masque of Angers, the Banqueting House is still used for state occasions (and, therefore, may be closed at short notice). The one room open to the public – the main hall upstairs – is well worth seeing for the superlative ceiling paintings, commissioned by Charles I from Rubens and installed in 1635. A glorification of the divine right of kings, the panels depict the union of England and Scotland, the peaceful reign of Charles’s father, James I and, finally, his apotheosis.

Given the subject of the paintings, it’s ironic that it was through the Banqueting House that Charles I walked in 1649 before stepping onto the executioner’s scaffold from one of its windows. Oliver Cromwell moved into Whitehall Palace in 1654, having declared himself Lord Protector, and kept open table in the Banqueting House for the officers of his New Model Army; he died here in 1658. Two years later Charles II celebrated the Restoration here, and kept open house for his adoring public – Samuel Pepys recalls seeing the underwear of one of his mistresses, Lady Castlemaine, hanging out to dry in the palace’s Privy Garden. (Charles housed two mistresses and his wife here, with a back entrance onto the river for courtesans.) To appreciate the place fully, it’s worth getting hold of one of the free audioguides.

CHARLES I

Stranded on a traffic island to the south of Nelson’s Column, on the site of the medieval Charing Cross, an equestrian statue of Charles I gazes down Whitehall to the place of his execution in 1649, outside the Banqueting House. The king wore two shirts in case he shivered in the cold, which the crowd would take to be fear, and once his head was chopped off, it was then sewn back on again for burial in Windsor – a very British touch. The statue itself was sculpted in 1633 and was originally intended for a site in Roehampton, but was sold off during the Commonwealth to a local brazier, John Rivett, with strict instructions to melt it down. Rivett made a small fortune selling bronze mementoes, allegedly from the metal, while all the time concealing the statue in the vaults of St Paul’s, Covent Garden. After the Restoration, in 1675, the statue was erected on the very spot where eight of those implicated in the king’s death were disembowelled in 1660. Until 1859, “King Charles the Martyr” Holy Day (Jan 30) was a day of fasting, and his execution is still commemorated here on the last Sunday in January with a parade by the royalist wing of the Civil War Society.

Horse Guards: Household Cavalry Museum

Whitehall • Daily: April–Oct 10am–6pm; Nov–March

10am–5pm • £6 • ![]() 020 7930 3070,

020 7930 3070, ![]() householdcavalrymuseum.co.uk • _test777

householdcavalrymuseum.co.uk • _test777![]() Charing Cross or Westminster

Charing Cross or Westminster

During the day, two mounted sentries and two horseless colleagues are posted to protect Horse Guards, a modest building begun in 1745 by William Kent, and originally the formal gateway to St James’s Palace. The black dot over the number two on the building’s clock face denotes the hour at which Charles I was executed close by in 1649. Round the back of the building, you’ll find the Household Cavalry Museum where you can try on a trooper’s elaborate uniform, complete a horse quiz and learn about the regiments’ history. With the stables immediately adjacent, it’s a sweet-smelling place, and – horse-lovers will be pleased to know – you can see the beasts in their stalls through a glass screen. Don’t miss the pocket riot act on display, which ends with the wise warning: “must read correctly: variance fatal”.

CHANGING THE GUARD

Changing the Guard takes place at two London

locations: the Foot Guards hold theirs outside Buckingham Palace

(May–July daily 11.30am; Aug–April alternate days; no ceremony if it

rains; ![]() royal.gov.uk), but

the more impressive one is held on Horse Guards Parade, behind Horse

Guards, where a squad of mounted Household Cavalry arrives from Hyde

Park to relieve the guards at the Horse Guards building on Whitehall

(Mon–Sat 11am, Sun 10am) – alternatively, if you miss the whole thing,

turn up at 4pm for the daily inspection by the Officer of the Guard, who

checks the soldiers haven’t knocked off early. If you want to see

something grander, check out Trooping the

Colour, and the Beating Retreat, which both take place in June.

royal.gov.uk), but

the more impressive one is held on Horse Guards Parade, behind Horse

Guards, where a squad of mounted Household Cavalry arrives from Hyde

Park to relieve the guards at the Horse Guards building on Whitehall

(Mon–Sat 11am, Sun 10am) – alternatively, if you miss the whole thing,

turn up at 4pm for the daily inspection by the Officer of the Guard, who

checks the soldiers haven’t knocked off early. If you want to see

something grander, check out Trooping the

Colour, and the Beating Retreat, which both take place in June.

The Queen is colonel-in-chief of the seven Household Regiments: the Life Guards (who dress in red and white) and the Blues and Royals (who dress in blue and red) – princes William and Harry were both in the Blues and Royals – are the two Household Cavalry Regiments; while the Grenadier, Coldstream, Scots, Irish and Welsh guards make up the Foot Guards. The Foot Guards can only be told apart by the plumes (or lack of them) in their busbies (fur helmets), and by the arrangement of their tunic buttons. The three senior regiments (Grenadier, Coldstream and Scots) date back to the seventeenth century, as do the Life Guards and the Blues and Royals. All seven regiments still form part of the modern army as well as performing ceremonial functions such as Changing the Guard.

Downing Street

• ![]() number10.gov.uk • _test777

number10.gov.uk • _test777![]() Westminster

Westminster

London’s most famous address, 10 Downing Street, is the terraced house that was presented to the First Lord of the Treasury, Robert Walpole, Britain’s first prime minister or PM, by George II in the 1730s. It has been the PM’s official residence ever since, with no. 11 the official home of the Chancellor of the Exchequer (in charge of the country’s finances) since 1806, and no. 12 official headquarters of the government’s Chief Whip (in charge of party discipline). These three are the only remaining bit of the original seventeenth-century cul-de-sac, though all are now interconnected and house much larger complexes than might appear from the outside. The public have been kept at bay since 1990, when Margaret Thatcher ordered a pair of iron gates to be installed at the junction with Whitehall, an act more symbolic than effective – a year later the IRA lobbed a mortar into the street from Horse Guards Parade, coming within a whisker of wiping out the entire Tory cabinet.

Churchill War Rooms

King Charles St • Daily 9.30am–6pm • £17 • ![]() 020 7930 6961,

020 7930 6961, ![]() iwm.org.uk • _test777

iwm.org.uk • _test777![]() Westminster

Westminster

In 1938, in anticipation of Nazi air raids, the basement of the Treasury building on King Charles Street was converted into the Churchill War Rooms, protected by a three-foot-thick concrete slab, reinforced with steel rails and tramlines. It was here that Winston Churchill directed operations and held cabinet meetings for the duration of World War II. By the end of the war, the six-acre site included a hospital, canteen and shooting range, as well as sleeping quarters; tunnels fan out from the complex to outlying government ministries, and also, it is rumoured, to Buckingham Palace itself, allowing the Royal Family a quick getaway to exile in Canada (via Charing Cross station) in the event of a Nazi invasion.

The rooms remain much as they were when they were abandoned on VJ Day, August 15, 1945, and make for an atmospheric underground trot through wartime London. To bring the place to life, pick up an audioguide, which includes various eyewitness accounts by folks who worked here. The best rooms are Winnie’s very modest emergency bedroom (though he himself rarely stayed here, preferring to watch the air raids from the roof of the building, or rest his head at the Savoy Hotel), and the Map Room, left exactly as it was on VJ Day, with its rank of multicoloured telephones, copious ashtrays and floor-to-ceiling maps covering every theatre of war.

Churchill Museum

When you get to Churchill’s secret telephone hotline direct to the American president, signs direct you to the self-contained Churchill Museum, which begins with his finest moment, when he took over as PM and Britain stood alone against the Nazis. You can hear snippets of Churchill’s speeches and check out his trademark bowler, spotted bow tie and half-chewed Havana, not to mention his wonderful burgundy zip-up “romper suit”. Fortunately for the curators, Churchill had an extremely eventful life and was great for a soundbite, so there are plenty of interesting anecdotes to keep you engaged.

WHITEHALL STATUES AND THE CENOTAPH

The statues dotted along Whitehall recall the days of the empire. Kings and military leaders predominate, starting outside Horse Guards with the 2nd Duke of Cambridge (1819–1904), whose horse was shot from under him in the Crimean War. As commander-in-chief of the British Army, he was so resistant to military reform that he had to be forcibly retired. Next stands the 8th Duke of Devonshire (1833–1908), who failed to rescue General Gordon from the Siege of Khartoum in 1884–85. Appropriately enough, Lord Haig (1861–1928), who was responsible for sending thousands to their deaths in World War I, faces the Cenotaph, his horse famously poised ready for urination. Before you get to the Cenotaph, there’s a striking memorial to the Women of World War II, featuring seventeen uniforms hanging on a large bronze plinth.

At the end of Whitehall, in the middle of the road, stands Edwin Lutyens’ Cenotaph, built in 1919 in wood and plaster to commemorate the Armistice, and rebuilt in Portland stone the following year. The stark monument, which eschews Christian imagery, is inscribed simply with the words “The Glorious Dead” – the lost of World War I, who, it was once calculated, would take three and a half days to pass by the Cenotaph marching four abreast. The memorial remains the focus of the Remembrance Sunday ceremony held on the Sunday nearest November 11. Between the wars, however, a much more powerful, two-minute silence was observed throughout the entire British Empire every year on November 11 at 11am, the exact time of the armistice at the end of World War I.

Houses of Parliament

Parliament Square • ![]() 020 7219 4272,

020 7219 4272, ![]() parliament.uk • _test777

parliament.uk • _test777![]() Westminster

Westminster

The Palace of Westminster, better known as the Houses of Parliament, is among London’s best-known icons. The city’s finest Victorian edifice and a symbol of a nation once confident of its place at the centre of the world, it’s best viewed from the south side of the river, where the likes of Monet and Turner once set up their easels. The building’s most famous feature is its ornate, gilded clock tower popularly known as Big Ben, at its most impressive when lit up at night. Strictly speaking, it’s the Elizabeth Tower – “Big Ben” is just the nickname for the thirteen-ton bell that strikes the hour (and is broadcast across the world by the BBC), after either the former Commissioner of Works, Benjamin Hall, or a popular heavyweight boxer of the time, Benjamin Caunt.

The original Palace of Westminster was built by Edward the Confessor in the eleventh century to allow him to watch over the building of his abbey. Westminster then served as the seat of all the English monarchs until a fire forced Henry VIII out, and he eventually decamped to Whitehall. The Lords have always convened at the palace, but it was only following Henry’s death that the House of Commons moved from the abbey’s Chapter House into the palace’s St Stephen’s Chapel.

In 1834, a fire reduced the old palace to rubble. Today, save for Westminster Hall, and a few pieces of the old structure buried deep within the interior, everything you see today is the work of Charles Barry, who wanted to create something that expressed national greatness through the use of Gothic and Elizabethan styles. The resulting orgy of honey-coloured pinnacles, turrets and tracery is the greatest achievement of the Gothic Revival. Inside, the Victorian love of mock-Gothic detail is evident in the maze of over one thousand committee rooms and offices, the fittings of which were largely the responsibility of Barry’s assistant, Augustus Pugin.

INFORMATION AND TOURS

Sitting times To find out exact “sitting times” and dates of “recesses” (holiday

closures), phone ![]() 020 7219 4272, or visit

020 7219 4272, or visit ![]() parliament.uk. If Parliament

is in session a Union flag flies from the southernmost tower, the

Victoria Tower; at night there’s a light above the clock face on Big

Ben.

parliament.uk. If Parliament

is in session a Union flag flies from the southernmost tower, the

Victoria Tower; at night there’s a light above the clock face on Big

Ben.

Public galleries To watch proceedings in either the House of Commons – the livelier of the two – or the House of Lords, simply join the queue for the public galleries on Cromwell Green, near St Stephen’s Gate. The public are let in slowly from about 2.30pm on Mondays, 11.30am on Tuesdays, around 1pm Wednesdays, and 9.30am on Thursdays and Sitting Fridays. Security is tight and the whole procedure can take over an hour, so to avoid the queues, turn up an hour or so later or on a Sitting Friday.

Question Time UK citizens can attend Question Time – when the House of Commons is at

its liveliest – which takes place in the first hour (Mon–Thurs) and

Prime Minister’s Question Time (Wed only), but they must book in advance

with their local MP (![]() 020 7219 3000).

020 7219 3000).

Guided tours Throughout the year there are Saturday tours (9.15am–4.30pm; £16.50)

and occasional more specialist tours (£30); during the summer there are

more frequent tours (Tues–Sat 9.15am–4.30pm) – in all cases tours take

just over an hour and it’s a good idea to book in advance (![]() 0844

847 1672), though you can buy tickets on the day from the

ticket office by the Jewel Tower. All year round, UK residents are

entitled to a free guided tour of the palace, as well as a guided tour

up Big Ben (Mon–Fri 9.15am, 11.15am & 2.15pm; no under-11s); both

need to be organized well in advance through your local MP or a member

of the House of Lords. Visitors for Big Ben must enter via Portcullis

House, the modern building on Victoria Embankment.

0844

847 1672), though you can buy tickets on the day from the

ticket office by the Jewel Tower. All year round, UK residents are

entitled to a free guided tour of the palace, as well as a guided tour

up Big Ben (Mon–Fri 9.15am, 11.15am & 2.15pm; no under-11s); both

need to be organized well in advance through your local MP or a member

of the House of Lords. Visitors for Big Ben must enter via Portcullis

House, the modern building on Victoria Embankment.

Westminster Hall

Virtually the only relic of the medieval palace is the bare expanse of Westminster Hall, which you enter after passing through security. Built by William II in 1099, it was saved from the 1834 fire by the timely intervention of the PM, Lord Melbourne, who took charge of the firefighting himself. The sheer scale of the hall – 240ft by 60ft – and its huge oak hammerbeam roof, added by Richard II in the late fourteenth century, make it one of the most magnificent secular medieval halls in Europe. It has also witnessed some nine hundred years of English history and been used for the lying-in-state of members of the Royal Family and a select few non-royals. Until 1821 every royal coronation banquet was held here and during the ceremony, the Royal Champion would ride into the hall in full armour to challenge any who dared dispute the sovereign’s right to the throne.

Until the nineteenth century the hall was also used as the country’s highest court of law: William Wallace had to wear a laurel crown during his treason trial here; Thomas More was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered (though in the end was simply beheaded); Guy Fawkes, the Catholic caught trying to blow up Parliament on November 5, 1605, was also tried here and actually hanged, drawn and quartered in Old Palace Yard. The trial of Charles I took place here, but the king refused to take his hat off, since he did not accept the court’s legitimacy. Oliver Cromwell, whose statue now stands outside the hall, was sworn in here as Lord Protector in 1653, only to be disinterred after the Restoration and tried here (whilst dead). His head was displayed on a spike above the hall for several decades until a storm dislodged it. It’s now buried in a secret location at Cromwell’s old college in Cambridge University.

St Stephen’s Hall

From Westminster Hall, visitors pass through the tiny St Stephen’s Hall, designed by Barry as a replica of the palace’s Gothic chapel (built by Edward I), where the Commons met from 1550 until the 1834 fire. It was into that chapel that Charles I entered with an armed guard in 1642 in a vain attempt to arrest five MPs who had made a speedy escape down the river – “I see my birds have flown”, he is supposed to have said. Shortly afterwards, the Civil War began, and no monarch has entered the Commons since. It was on the steps of the hall, in 1812, that Spencer Perceval – the only British prime minister to be assassinated – was shot by a merchant whose business had been ruined by the Napoleonic Wars.

Central Lobby

Next you come to the bustling, octagonal Central Lobby, where constituents can “lobby” their MPs. In the tiling of the lobby Pugin inscribed the Biblical quote in Latin: “Except the Lord keep the house, they labour in vain that build it”. In view of what happened to the architects, the sentiment seems like an indictment of parliamentary morality – Pugin ended up in Bedlam mental hospital and Barry died from overwork within months of completing the job.

The House of Commons

If you’re going to listen to proceedings in the House of Commons, you’ll be asked to sign a form vowing not to cause a disturbance and then led up to the Public Gallery. Protests from the gallery used to be a fairly regular occurrence: suffragettes have poured flour, farmers have dumped dung, Irish Nationalists have lobbed tear gas and lesbians have abseiled down into the chamber, but a screen now protects the MPs. An incendiary bomb in May 1941 destroyed Barry’s original chamber, so what you see now is a rather lifeless postwar reconstruction. Barry’s design was modelled on the palace’s original St Stephen’s Hall, hence the choir-stall arrangement of the MPs’ benches. Members of the cabinet (and the opposition’s shadow cabinet) occupy the two “front benches”; the rest are “backbenchers”. The chamber is at its busiest during Question Time, though if more than 427 of the 650 MPs turn up, a large number have to remain standing. For much of the time, however, the chamber is almost empty, with just a handful of MPs present from each party.

The House of Lords

On the other side of the Central Lobby, a corridor leads to the House of Lords (or Upper House), a far dozier establishment peopled by unelected Lords and Ladies, plus a smattering of bishops. Their home boasts much grander decor than the Commons, full of regal gold and scarlet, and dominated by Pugin’s great canopied gilded throne where the Queen sits for the state opening of Parliament in May. Directly in front of the throne, the Lord Chancellor runs the proceedings from the scarlet Woolsack, an enormous cushion stuffed with wool, which harks back to the time when it was England’s principal export. Until 1999, there were one thousand plus hereditary Lords (over a quarter of whom had been to Eton) in the House. Most rarely bothered to turn up, but at critical votes, they could be (and were) called upon by the Conservatives, to ensure a right-wing victory. Today, just 92 hereditary peers sit in the House, along with 26 senior bishops, while the rest are made up of life peers, appointed by the Queen on the advice of the Prime Minister. However, for the most part, the Lords have very little real power, as they can only advise, amend and review parliamentary bills.

The royal apartments

To see any more of parliament’s pomp and glitter you’ll need to go on a guided tour. Beyond the House of Lords is the Princes’ Chamber, known as the Tudor Room after the portraits that line the walls, including Henry VIII and all six of his wives. Beyond here you enter the Royal Gallery, a cavernous writing room for the House of Lords, hung with portraits of royals past and present, and two 45-foot-long frescoes of Trafalgar and Waterloo. Next door is the Queen’s Robing Chamber, which boasts a superb coffered ceiling and lacklustre Arthurian frescoes. As the name suggests, this is the room where the monarch dons the crown jewels before entering the Lords. Lastly, you get to see the Norman Porch, every nook of which is stuffed with busts of eminent statesmen, and the Royal Staircase, which is lined with guards from the Household Cavalry when the Queen arrives for the annual state opening of Parliament in May.

Jewel Tower

Daily 10am–5pm • EH • £3.90 • ![]() 020 7222 2219 • _test777

020 7222 2219 • _test777![]() Westminster

Westminster

The Jewel Tower across the road from the Sovereign’s Entrance, is the only other major remnant of the medieval palace apart from Westminster Hall. Constructed in 1365 by Edward III as a giant strongbox for his most valuable possessions, the tower formed the southwestern corner of the original exterior fortifications (there’s a bit of moat left, too), and was called the King’s Privy Wardrobe. Later, it was used to store the records of the House of Lords, and then as a testing centre by the Board of Trade’s Standards Department. Nowadays, the tower houses a small exhibition on the history of the Palace of Westminster and on the tower itself.

Victoria Tower Gardens

To the south of Parliament’s Victoria Tower are the leafy Victoria Tower Gardens, which look out onto the Thames. Visitors are greeted by a statue of Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the suffragette movement, who died in 1928, the same year women finally got the vote on equal terms with men; medallions commemorating her daughter Christabel, and a WPSU Prisoners’ Badge, flank the statue. Round the corner, a replica of Rodin’s famous sculpture, The Burghers of Calais, makes a surprising appearance here, while at the far end of the gardens stands the Buxton Memorial, a neo-Gothic fountain, made from a real potpourri of exotic materials, erected in 1865 to commemorate the 1834 abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

Westminster Abbey

Parliament Square • Hours can vary: Mon–Fri 9.30am–4.30pm, Wed until

6pm, Sat 9.30am–2.30pm • £18 • ![]() 020 7654 4900,

020 7654 4900, ![]() westminster-abbey.org • _test777

westminster-abbey.org • _test777![]() Westminster

Westminster

The Houses of Parliament dwarf their much older neighbour, Westminster Abbey, which squats awkwardly on the western edge of Parliament Square. Yet this single building embodies much of the history of England: it has been the venue for every coronation since the time of William the Conqueror, and the site of just about every royal burial for some five hundred years between the reigns of Henry III and George II. Scores of the nation’s most famous citizens are honoured here, too – though many of the stones commemorate people buried elsewhere – and the interior is cluttered with literally hundreds of monuments, reliefs and statues.

With over 3300 people buried beneath its flagstones and countless others commemorated here, the abbey is, in essence, a giant mausoleum. It has long ceased to be simply a working church, and hefty admission charges are nothing new: Oliver Goldsmith complained about being charged three pence in 1765. A century or so later, so few people used the abbey as a church that, according to George Bernard Shaw, one foreign visitor kneeling in prayer was promptly arrested because the verger thought he was acting suspiciously. Despite protestations to the contrary, the abbey is now more mass tourist attraction than House of God.

INFORMATION AND TOURS

Information If you have any questions, ask the vergers in the black gowns, the marshals in red or the abbey volunteers in green. Note that you can visit the Chapter House, the Cloisters and the College Garden (free admission), without buying an abbey ticket, by entering via Dean’s Yard.

Tours There are guided tours by the vergers, which allow access to the Confessor’s Tomb (Mon–Sat, times vary; ring for details; 1hr 30min; £3). A free audioguide is available.

Services Admission to the daily services at the abbey (check website for details) is, of course, free. Evensong is at 5pm on weekdays.

WESTMINSTER ABBEY

Brief history

Legend has it that the first church on the site was consecrated by St Peter himself, who was rowed across the Thames by a fisherman named Edric, to whom he granted a giant salmon as a reward. More verifiable is that there was a small Benedictine monastery here by the tenth century, for which Edward the Confessor built an enormous church. Nothing much remains of Edward’s church, which was consecrated on December 28, 1065, just eight days before his death. The following January his successor, Harold, was crowned, and, on Christmas Day, William the Conqueror rode up the aisle on horseback, thus firmly establishing the tradition of royal coronation within the Confessor’s church.

It was in honour of Edward (who had by now been canonized) that Henry III began to rebuild the abbey in 1245, in the French Gothic style of the recently completed Rheims Cathedral. The monks were kicked out during the Reformation, but the church’s status as the nation’s royal mausoleum saved it from any physical damage. In the early eighteenth century, Nicholas Hawksmoor designed the quasi-Gothic west front, while the most recent additions can be seen above the west door: a series of statues representing twentieth-century martyrs, from Dietrich Bonhöffer to Martin Luther King.

Statesmen’s Aisle and the Sanctuary

The north transept, where you enter, is littered with overblown monuments to long-forgotten empire-builders and nineteenth-century politicians, and traditionally known as Statesmen’s Aisle. From here, you can go straight to the central Sanctuary, site of the royal coronations. The most precious work of art here is the thirteenth-century Italian floor mosaic known as the Cosmati pavement. It depicts the universe with interwoven circles and squares of Purbeck marble, glass, and red and green porphyry, though it’s sometimes covered by a carpet to protect it. The richly gilded high altar, like the ornately carved choir stalls, is, in fact, a neo-Gothic construction from the nineteenth century.

The side chapels

Some of the best funereal art is tucked away in St Michael’s Chapel, east of the Statesmen’s Aisle, where you can admire the remarkable monument to Francis Vere (1560–1609), one of the greatest soldiers of the Elizabethan period, made out of two slabs of black marble, between which lies Sir Francis; on the upper slab, supported by four knights, his armour is laid out, to show that he died away from the field of battle. The most striking grave, by Roubiliac, is that in which Elizabeth Nightingale, who died from a miscarriage, collapses in her husband’s arms while he tries to fight off the skeletal figure of Death, who is climbing out of the tomb.

In the north ambulatory, two more chapels contain ostentatious Tudor and Stuart tombs that replaced the altarpieces that had graced them before the Reformation. One of the most extravagant tombs is that of Lord Hunsdon, Lord Chancellor to Elizabeth I, which dominates the Chapel of St John the Baptist, and, at 36ft in height, is the tallest in the entire abbey. More intriguing, though, are the sarcophagi in the neighbouring Chapel of St Paul: one depicts eight “weepers”, kneeling children along the base of the tomb – the two holding skulls predeceased their parents – while the red-robed Countess of Sussex has a beautiful turquoise and gold porcupine (the family emblem) as her prickly footrest.

Henry VII’s Chapel

From the Chapel of St Paul you can climb the stairs and enter the Lady Chapel, better known as Henry VII’s Chapel, the most dazzling architectural set piece in the abbey. Begun by Henry VII in 1503 and dedicated to the Virgin Mary, it represents the final gasp of the English Perpendicular style, with its beautiful, light, intricately carved vaulting, fan-shaped gilded pendants and statues of nearly one hundred saints, high above the choir stalls. The stalls themselves are decorated with the banners and emblems of the Knights of the Order of the Bath, established by George I. George II, the last king to be buried in the abbey, lies in the burial vault under your feet, along with Queen Caroline – their coffins were fitted with removable sides so that their remains could mingle.

Beneath the altar is the grave of Edward VI, the single, sickly son of Henry VIII, while behind lies the chapel’s centrepiece, the black marble sarcophagus of Henry VII and his spouse – their lifelike gilded effigies, modelled from death masks, are obscured by an ornate Renaissance grille by Pietro Torrigiano, who fled from Italy after breaking Michelangelo’s nose in a fight. James I is also interred within Henry’s tomb, while the first of the apse chapels, to the north, hosts a grand monument by Hubert le Sueur to James’s lover, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, the first non-royal to be buried in this part of the abbey, who was killed by one of his own disgruntled soldiers.

The side chapels

The easternmost RAF Chapel sports a stained-glass window depicting airmen and angels in the Battle of Britain and a small piece of bomb damage from World War II. In the floor, a plaque marks the spot where Oliver Cromwell rested, briefly, until the Restoration, whereupon his mummified body was disinterred, dragged through the streets, hanged at Tyburn and beheaded. And the last of the apse chapels contains another overblown Le Sueur monument, in which four caryatids, holding up a vast bronze canopy, weep for Ludovic Stuart, another of James I’s “favourites”.

North aisle: Elizabeth I and the Innocents

Before descending the steps back into the ambulatory, pop into the chapel’s north aisle, which is virtually cut off from the chancel. Here James I erected a huge ten-poster tomb to his predecessor, Elizabeth I. Unless you read the plaque on the floor, you’d never know that Elizabeth’s Catholic half-sister, “Bloody Mary”, is also buried here, in an unusual act of posthumous reconciliation. The far end of the north aisle, where James I’s two infant daughters lie, is known as Innocents’ Corner: Princess Sophia, who died aged three days, lies in an alabaster cradle, her face peeping over the covers, just about visible in the mirror on the wall; Princess Mary, who died the following year aged 2, is clearly visible, casually leaning on a cushion. Set into the wall between the two is the Wren-designed urn containing (what are thought to be) the bones of the Princes in the Tower, Edward V and his younger brother, Richard (see Bloody Tower).

South aisle: Mary Queen of Scots

The south aisle of Henry VII’s Chapel contains a trio of stellar tombs, including James I’s mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, whom Elizabeth I had beheaded. James had Mary’s remains brought from Peterborough Cathedral in 1612, and paid significantly more for her extravagant eight-postered tomb, bristling with Scottish thistles and complete with a terrifyingly aggressive Scottish lion, than he had done for Elizabeth’s; the 27 hangers-on (including the Cavalier Prince Rupert and the “Winter Queen”, Elizabeth of Bohemia) who are buried with her are listed on the nearby wooden screen. The last of the tombs here is that of Lady Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII’s mother, her face and hands depicted wrinkles and all by Torrigiano. Below the altar, commemorated by simple modern plaques, lie yet more royals: William and Mary, Queen Anne and Charles II.

The Coronation Chair

As you leave Henry VII’s Chapel, look out for Edward I’s Coronation Chair, a decrepit oak throne dating from around 1300. The graffiti-covered chair, used in every coronation since 1308, was custom-built to incorporate the Stone of Scone, a great slab of red sandstone which acted as the Scottish coronation stone for centuries before Edward pilfered it in 1296. The stone remained in the abbey for the next seven hundred years, apart from a brief interlude in 1950, when some Scottish nationalists managed to steal it back and hide it in Arbroath. In a futile attempt to curry favour with the Scots before the 1997 election, the Conservatives returned the stone to Edinburgh Castle, where it now resides until the next coronation.

The Shrine of Edward the Confessor

Behind the chair lies the tomb of Henry V, who died of dysentery in France in 1422 at the age of just 35, and was regarded as a saint in his day. Above him rises the highly decorative, H-shaped Chantry Chapel, where the body of Henry’s wife, Catherine of Valois, was openly displayed for several centuries – Pepys records kissing her corpse on his 36th-birthday visit to the abbey. The chapel acts as a sort of gatehouse for the Shrine of Edward the Confessor, the sacred heart of the building, and site of some of the abbey’s finest tombs, now only accessible on a guided tour. With some difficulty, you can just about make out the battered marble casket of the Confessor’s tomb and the niches in which pilgrims would kneel.

Poets’ Corner

In the south transept, you’ll find the increasingly popular Poets’ Corner. The first occupant, Geoffrey Chaucer, was buried here in 1400, not because he was a poet, but because he lived nearby, and his battered tomb, on the east wall, wasn’t built for another 150-odd years. When Edmund Spenser chose to be buried close to Chaucer in 1599, his fellow poets – Shakespeare among them (possibly) – threw their own works and quills into the grave. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until the eighteenth century that this zone became an artistic pantheon, since when the transept has been filled with tributes to all shades of talent.

Among those who are actually buried here, you’ll find – after much searching – grave slabs or memorials for everyone from John Dryden and Samuel Johnson to Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy (though his heart was buried in Dorset). Among the merely commemorated is William Shakespeare, whose dandyish statue is on the east wall. Even mavericks like Oscar Wilde, commemorated in the Hubbard window, are acknowledged here, though William Blake was honoured by a Jacob Epstein sculpture only in 1957, and Byron was refused burial for his “open profligacy”, and had to wait until 1969.

Among the non-poets buried here are the great eighteenth-century actor David Garrick, depicted parting the curtains for a final bow, and the German composer Georg Friedrich Handel, who spent most of his life at the English court, and wrote the coronation anthem Zadok the Priest, first performed at George II’s coronation, and performed at every subsequent one. There’s even one illiterate, Thomas Parr, a Shropshire man who arrived in London as a celebrity in 1635 at the alleged age of 152, but died shortly afterwards, and whose remains were brought here by Charles II.

South choir aisle

Before you enter the cloisters, it’s worth seeking out several wonderful memorials to undeserving types in the south choir aisle, though you may have to ask a verger to allow you to see them properly. The first is to Thomas Thynne, a Restoration rake, whose tomb incorporates a relief showing his assassination in his coach on Pall Mall by three thugs, hired to kill him by his Swedish rival in love. Further along lies Admiral Clowdisley Shovell, lounging in toga and wig. One of only two survivors of a shipwreck in 1707, he was washed up alive on a beach in the Scilly Isles, off southwest England, only to be killed by a fisherwoman for his emerald ring. Above Shovell is a memorial to the court portrait painter Godfrey Kneller, who declared, “By God, I will not be buried in Westminster – they do bury fools there”. In the event, he has the honour of being the only artist commemorated in the abbey (most are in St Paul’s); the tomb is to his own design, but the epitaph is by Pope, who admitted it was the worst thing he ever wrote – which is just as well, as it’s so high up you can’t read it.

The cloisters

Cloisters daily 10am–6pm; Chapter House daily 10.30am–4pm • Free via Dean’s Yard entrance

Doors in the south choir aisle lead to the Great Cloister, rebuilt after a fire in 1298 and paved with yet more funerary slabs, including, at the bottom of the ramp, that of the proto-feminist writer Aphra Behn, upon whose tomb “all women together ought to let flowers fall”, according to Virginia Woolf, “for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds”.

At the eastern end lies the octagonal Chapter House, built in the 1250s and used by Henry III’s Great Council, England’s putative parliament. The House of Commons continued to meet here until 1395, though the monks were none too happy about it, complaining that the shuffling and stamping wore out the expensive tiled floor. Despite their whingeing, the paving tiles have survived well, as have sections of the remarkable apocalyptic wall-paintings, which were executed in celebration of the eviction of the Commons. Be sure to check out the southern wall, where the Whore of Babylon rides the scarlet seven-headed beast from The Book of Revelation.

Pyx Chamber and Museum

Daily: Pyx Chamber 10.30am–3.30pm; museum 10.30am–4pm • Free