Mayfair

Although shops, offices, embassies and hotels outnumber aristocratic pieds-à-terre nowadays, the social cachet of the luxury apartments and mews houses of Mayfair has remained much the same. This is, after all, where the fictional Bertie Wooster – the perfect upper-class Englishman – and his faithful valet Jeeves, of P.G. Wodehouse’s interwar novels, lived. Piccadilly may not be the fashionable promenade it once was, but a whiff of exclusivity still pervades Bond Street and its tributaries, where designer clothes emporia jostle for space with jewellers, bespoke tailors and fine art dealers. Most Londoners, however, stick to Regent and Oxford streets, home to the flagship branches of the country’s most popular chain stores and heart of the West End in terms of shopping.

Along with neighbouring St James’s and Marylebone, Mayfair emerged in the eighteenth century as one of London’s first real residential suburbs. Sheep and cattle were driven off the land by the area’s big landowners (the largest of whom were the Grosvenor family, whose head is the Duke of Westminster, Britain’s richest man) to make way for London’s first major planned development: a web of brick-and-stucco terraces and grid-plan streets feeding into a trio of grand, formal squares, with mews and stables round the back. The name comes from the infamous fifteen-day fair, which bit the dust in 1764 after the newly ensconced wealthy residents complained of the “drunkenness, fornication, gaming and lewdness”. Mayfair quickly began to attract aristocratic London away from hitherto fashionable Covent Garden and Soho, and set the westward trend for upper-middle-class migration.

Piccadilly Circus

Tacky and congested it may be, but for many visitors, Piccadilly Circus is up there with Trafalgar Square as a candidate for London’s city centre. A much-altered product of Nash’s grand 1812 Regent Street plan, and now a major bottleneck, with traffic from Piccadilly, Shaftesbury Avenue and Regent Street all converging, it’s by no means a picturesque place, and is probably best seen at night, when the spread of illuminated signs (a feature since the Edwardian era) gives it a touch of Times Square dazzle, and when the human traffic flow is at its most frenetic.

As well as being the gateway to the West End, this is also prime tourist territory, thanks mostly to the celebrated Shaftesbury Memorial, popularly known as Eros. The fountain’s aluminium archer is one of London’s top tourist attractions, a status that baffles all who live here – when it was first unveiled in 1893, it was so unpopular that the sculptor, Alfred Gilbert, lived in self-imposed exile for the next thirty years. The figure depicted is not Eros, but his lesser-known brother Anteros, who was the god of requited love, although in this case he commemorates the selfless philanthropic love of the Earl of Shaftesbury, a Bible-thumping social reformer who campaigned against child labour.

Behind Eros, it’s worth popping in to The Criterion restaurant, at no. 224 Piccadilly, just for a drink, so you can soak in probably the most spectacular Victorian interior in London, with its Byzantine-style gilded mosaic ceiling.

Trocadero

Piccadilly Circus • Daily 10am–midnight, Fri & Sat until

1am • ![]() 020 7439 1719,

020 7439 1719, ![]() londontrocadero.com • _test777

londontrocadero.com • _test777![]() Piccadilly Circus

Piccadilly Circus

Just east of the Circus, Trocadero was originally an opulent restaurant, from 1896 until its closure in 1965. Since then, millions have been poured into this glorified amusement arcade, casino and multiplex cinema, in an unsuccessful attempt to find a winning formula. Much of the building is currently being gutted and redeveloped to include London’s first Tokyo-style pod hotel, with over 580 windowless rooms.

Ripley’s Believe It or Not!

Piccadilly Circus • Daily 10am–10.30pm • £25 • ![]() 020 3238 0022,

020 3238 0022, ![]() ripleyslondon.com • _test777

ripleyslondon.com • _test777![]() Piccadilly Circus

Piccadilly Circus

Next door to Trocadero, in what was once the London Pavilion music hall, is the world’s largest branch of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, which bills itself as an odditorium. It’s half waxworks, half old-fashioned Victorian freak show, with a mirror maze and laser maze thrown in for good measure. Delights on display include shrunken heads and dinosaur eggs, a chewing gum sculpture of the Fab Four and Tower Bridge rendered in 264,345 matchsticks. Book online to save a few pounds off the stratospheric admission charge.

Regent Street

Regent Street was drawn up by John Nash in 1812 as both a luxury shopping street and a triumphal way between George IV’s (now demolished) Carlton House and Regent’s Park to the north. It was the city’s first stab at slum clearance, creating a tangible borderline to shore up fashionable Mayfair against the chaotic maze of neighbouring Soho. Today, it’s still possible to admire the stately intentions of Nash’s plan, even though the original arcading of the Quadrant, which curves westwards from Piccadilly Circus, is no longer there.

Regent Street enjoyed eighty years as Bond Street’s nearest rival, before the rise of the city’s middle classes ushered in heavyweight stores catering for the masses. Two of the oldest established stores can be found close to one another on the east side of the street: Hamleys, which claims to be the world’s largest toy shop, and Liberty, the department store that popularized Arts and Crafts designs. Liberty’s famous mock-Tudor entrance, added in the 1920s, is round the corner on Great Marlborough Street – inside there’s a central roof-lit well, surrounded by wooden galleries carved from the timbers of two old naval battleships.

MONOPOLY

Although Monopoly was patented during the Depression by an American, Charles Darrow, it was the British who really took to the game, and the UK version was the one used in the rest of the world outside of the US. In 1935, to choose appropriate streets and stations for the game, the company director of Waddington’s in Leeds sent his son, Norman Watson, and his secretary, Marjorie Phillips, on a day-trip to London. They came up with an odd assortment, ranging from the bottom-ranking Old Kent Road (still as tatty as ever) to an obscure dead-end street in the West End (Vine Street), and chose only northern train stations. All the properties have gone up in value since the board’s inception (six zeros need to be added to most), but Mayfair and Park Lane (its western border), the most expensive properties, are still aspirational addresses.

Piccadilly

Piccadilly apparently got its name from a local resident who manufactured the ruffs or “pickadills” worn by the dandies of the late seventeenth century. Despite its fashionable pedigree, it’s no place for promenading in its current state, with traffic careering down it nose to tail most of the day and night. Infinitely more pleasant places to window-shop are the nineteenth-century arcades, built to protect shoppers from the mud and horse dung on the streets, but now equally useful for escaping exhaust fumes.

Waterstones and Hatchard’s

One of the most striking shops on Piccadilly, at nos. 203–206, is the sleek modernist 1930s facade of Simpsons department store, now the multistorey flagship bookstore of Waterstones. While Piccadilly may not be the shopping heaven it once was, it still harbours several old firms that proudly display their royal warrants. London’s oldest bookshop, Hatchard’s, at no. 187, was founded in 1797, as a cross between a gentlemen’s club and a library, with benches outside for servants and daily papers inside for the gentlemen to peruse. Today, it’s a sister branch of Waterstones, elegant still, but with its old traditions marked most overtly by an unrivalled section on international royalty.

St James’s Church

197 Piccadilly • ![]() 020 7734 4511,

020 7734 4511, ![]() sjp.org.uk • _test777

sjp.org.uk • _test777![]() Piccadilly Circus

Piccadilly Circus

Halfway along the south side of Piccadilly stands St James’s Church, Wren’s favourite parish church (he built it himself). The church has rich furnishings, with the limewood reredos, organ-casing and marble font all by the master sculptor Grinling Gibbons. St James’s is a radical campaigning church, which runs a daily craft market (Tues–Sat) and a café at the west end of the church; it also puts on top-class, free lunchtime concerts and regularly displays contemporary outdoor sculptures in the churchyard.

Fortnum & Mason

181 Piccadilly • Mon–Sat 10am–8pm, Sun noon–6pm • ![]() 020 7734 8040,

020 7734 8040, ![]() fortnumandmason.com • _test777

fortnumandmason.com • _test777![]() Green Park or Piccadilly Circus

Green Park or Piccadilly Circus

One of Piccadilly’s oldest institutions is Fortnum & Mason, the food emporium established in 1707 by Hugh Mason (who used to run a stall at St James’s market) and William Fortnum (one of Queen Anne’s footmen). Over the main entrance, the figures of its founders bow to each other on the hour as the clock clanks out the Eton school anthem – a kitsch addition from 1964. The store is most famous for its opulent food hall and its picnic hampers, first introduced as “concentrated lunches” for hunting and shooting parties, and now de rigueur for Ascot, Glyndebourne, Henley and other society events. Fortnum’s is credited with the invention of the Scotch egg in 1851, and was also the first store in the world to sell Heinz baked beans in 1886.

Albany

One palatial Piccadilly residence that has avoided redevelopment is Albany, a plain, H-shaped Georgian mansion, designed by William Chambers, neatly recessed behind its own iron railings and courtyard, next door to the Royal Academy. Built in the 1770s for Lord Melbourne, it was divided in 1802 into a series of self-contained bachelor “sets” for members of the nearby gentlemen’s clubs too drunk to make it home. Only those who had no connections with trade, and did not keep a musical instrument or a wife, were permitted to live here, and over the years they have been occupied by such literary figures as Byron, Gladstone, J.B. Priestley, Aldous Huxley, Patrick Hamilton and Graham Greene.

Royal Academy of the Arts

Burlington House, Piccadilly • Daily 10am–6pm, Fri until 10pm • £10–15 • John Madejski Fine Rooms guided tours Tues

1pm, Wed–Fri 1 & 3pm, Sat 11.30am; free • ![]() 020 7300 8000,

020 7300 8000, ![]() royalacademy.org.uk • _test777

royalacademy.org.uk • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

The Royal Academy of Arts occupies Burlington House, one of the few survivors from the ranks of aristocratic mansions that once lined the north side of Piccadilly. Rebuilding in the nineteenth century destroyed the original curved colonnades beyond the main gateway, but the complex has kept the feel of a Palladian palazzo. The academy itself was the country’s first formal art school, founded in 1768 by a group of painters including Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds went on to become the academy’s first president, and his statue now stands in the courtyard, palette in hand ready to paint the cars hurtling down Piccadilly.

The academy’s alumni range from Turner and Constable to Hockney and Tracey Emin, though the college has always had a conservative reputation for both its teaching and its shows. As well as hosting exhibitions, the RA has a small selection of works from its permanent collection in the white and gold John Madejski Fine Rooms. Highlights include a Rembrandtesque self-portrait by Reynolds, plus works by the likes of Constable, Hockney and Stanley Spencer. To see the gallery’s most valuable asset, Michelangelo’s marble relief, the Taddei Tondo, head for the narrow glass atrium of Norman Foster’s Sackler Galleries, at the back of the building.

THE SUMMER EXHIBITION

The most famous event in the Royal Academy’s calendar is the Summer Exhibition, which has been held annually since 1769, and runs from June to mid-August. It’s an odd event: anyone can enter paintings in any style. Around ten thousand entries are surveyed (at considerable speed) by the RA’s Hanging Committee (great name) and around one thousand lucky winners get hung, in extremely close proximity, and sold. In addition, the eighty “Academicians” are allowed to display up to six of their own works – no matter how awful. The result is a bewildering display, which gets annually panned by the critics. However, with thirty percent of the purchase price going to the RA, it generates at least £2 million in income.

The Wolseley and the Ritz

On the south side of Piccadilly, on the corner of Arlington Street, The Wolseley is a superb Art Deco building, originally built as a Wolseley car showroom in the 1920s, now a café. The most striking original features are the zigzag inlaid marble flooring, the chinoiserie woodwork and the giant red Japanese lacquer columns. Across St James’s Street, with its best rooms overlooking Green Park, stands the Ritz Hotel, famous for its afternoon teas and a byword for decadence since it first wowed Edwardian society in 1906. The hotel’s design, with its two-storey French-style mansard roof and long arcade, was based on the rue de Rivoli in Paris.

Burlington Arcade

Mon–Wed & Fri 8am–6.30pm, Thurs 8am–7pm,

Sat 9am–6.30pm, Sun 11am–5pm • Free • ![]() burlington-arcade.co.uk • _test777

burlington-arcade.co.uk • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

Along the side of the Royal Academy runs the Burlington Arcade, London’s first shopping arcade, built in 1819 for Lord Cavendish, then owner of Burlington House, to prevent commoners throwing rubbish into his garden. Today, it’s London’s longest and most expensive nineteenth-century arcade, lined with mahogany-fronted luxury shops, including Linley, run by the Queen’s nephew. Upholding Regency decorum, it’s still illegal to whistle, sing, hum, hurry or carry large packages or open umbrellas on this small stretch, and the arcade’s beadles (known as Burlington Berties), in their Edwardian frock coats and gold-braided top hats, take the prevention of such criminality very seriously.

Piccadilly and Princes arcades

• ![]() piccadillyarcade.com,

piccadillyarcade.com, ![]() princesarcade.com • _test777

princesarcade.com • _test777![]() Green Park or Piccadilly Circus

Green Park or Piccadilly Circus

Neither of Piccadilly’s other two arcades can hold a torch to the Burlington, though they are still worth exploring if only to marvel at the strange mixture of shops. The finer of the two is the Piccadilly Arcade, an Edwardian extension to the Burlington on the south side of Piccadilly, whose squeaky-clean bow windows display, among other items, Russian icons, model soldiers and buttons and cufflinks supplied to Prince Charles. The Princes Arcade, to the east, exudes a more discreet Neoclassical elegance and contains Prestat, purveyors of handmade, hand-packed chocolates and truffles to the Queen.

Bond Street

Bond Street runs more or less parallel to Regent Street, extending north from Piccadilly all the way to Oxford Street. It is, in fact, two streets rolled into one: the southern half, laid out in the 1680s, is known as Old Bond Street; its northern extension, which followed less than fifty years later, is known as New Bond Street. In contrast to their international rivals, rue de Rivoli and Fifth Avenue, both Bond streets are pretty unassuming architecturally – a mixture of modest Georgian and Victorian townhouses – but the shops that line them are among the flashiest in London.

Bond Street shops

Unlike its overtly masculine counterpart, Jermyn Street, Bond Street caters for both sexes, and although it has its fair share of old-established names, it’s also home to flagship branches of multinational designer clothes outlets like Prada, D&G, Versace, Chanel and so on. This designer madness also spills over into Conduit Street, home to Issey Miyake, Vivienne Westwood and Moschino, not to mention Rigby & Peller, corsetieres to the Queen, as well as into neighbouring Dover Street, where Comme des Garçons have a vast indoor fashion bazaar at nos. 17–18.

Bond Street also has its fair share of perfumeries and jewellers, many of them long-established outlets that have survived the vicissitudes of fashion, and some, like De Beers, relatively recent arrivals. One of the most famous is Asprey, founded in 1781 by a family of Huguenot craftsmen, and now jewellers to the royals. The facade of the store, at no. 167, features a wonderful parade of arched windows, flanked by slender Corinthian wrought-iron columns. Close by is Allies, a popular double statue of Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt, enjoying a chat on a bench – you can squeeze between the two of them, in the space where Stalin should be, for a photo opportunity.

Auction houses and art galleries

In addition to fashion, Bond Street is renowned for its auction houses and art galleries, although the latter are actually outnumbered by those on neighbouring Cork Street. The main difference between the two is that the Bond Street dealers are basically heirloom offloaders, where you might catch an Old Master or an Impressionist masterpiece, whereas Cork Street galleries and others dotted throughout Mayfair – such as the Mason’s Yard outpost of White Cube – show largely contemporary art.

AUCTION HOUSES

A very Mayfair-style entertainment lies in visiting the area’s trio of

auction houses. Sotheby’s, 34–35 New

Bond St (![]() 020 7293 5000,

020 7293 5000, ![]() sothebys.com), was founded in

1744 and is the oldest of the three (and the fourth oldest in the

world), though its pre-eminence only really dates from the last war.

Above the doorway of Sotheby’s is London’s oldest outdoor sculpture, an

Egyptian statue dating from 1600 BC. Bonhams, founded in 1793 (and now merged with Phillips),

is at 101 New Bond St (

sothebys.com), was founded in

1744 and is the oldest of the three (and the fourth oldest in the

world), though its pre-eminence only really dates from the last war.

Above the doorway of Sotheby’s is London’s oldest outdoor sculpture, an

Egyptian statue dating from 1600 BC. Bonhams, founded in 1793 (and now merged with Phillips),

is at 101 New Bond St (![]() 020 7447 7447,

020 7447 7447, ![]() bonhams.com); and Christie’s, founded in 1766, and now the

world’s largest auction house, is actually over in St James’s at 8 King

St (

bonhams.com); and Christie’s, founded in 1766, and now the

world’s largest auction house, is actually over in St James’s at 8 King

St (![]() 020 7839 9060,

020 7839 9060, ![]() christies.com).

christies.com).

Viewing takes place from Monday to Friday, and also occasionally at the weekend, and entry to the galleries is free of charge, though if you don’t buy a catalogue, the only information you’ll glean is the lot number. Thousands of the works that pass through the rooms are of museum quality, and, if you’re lucky, you might catch a glimpse of a masterpiece in transit between private collections. Anyone can attend the auctions themselves, though remember to keep your hands firmly out of view unless you’re bidding.

Sotheby’s is probably the least intimidating: there’s an excellent café, and staff offer free valuations, if you have an heirloom of your own to check out. There’s always a line of people unwrapping items under the polite gaze of valuation staff, who call in the experts if they see something that sniffs of real money. Only Bonhams remains British-owned; Christie’s and Sotheby’s, once quintessentially English institutions, are now under French and US control.

Smythson

40 New Bond St • Mon–Wed & Fri 9.30am–6pm, Thurs 10am–7pm,

Sat 10am–6pm • ![]() smythson.com • _test777

smythson.com • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

One Bond Street institution you can feel free to walk into is Smythson, the bespoke stationers, founded in 1887, who made their name printing Big Game books for colonialists to record what they’d bagged out in Africa and India. At the back of the shop is a small octagonal museum encrusted with shells and mirrors, and a few artefacts: photos and replicas of the book of condolence Smythson created for JFK’s funeral, and the cherry calf-and-vellum diary given to Princess Grace of Monaco as a wedding gift.

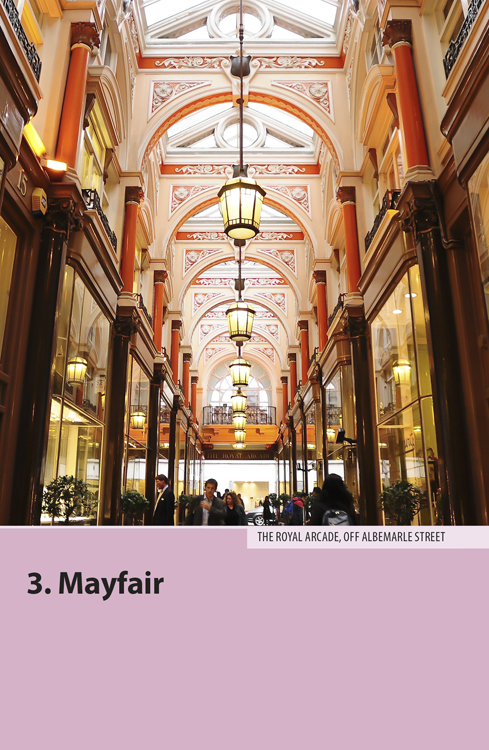

Albemarle Street

Running parallel to Bond Street to the west, is Albemarle Street, connected by the Royal Arcade, a short High Victorian shopping mall with tall arched bays and an elegant glass roof, with garish orange-and-white plasterwork entrances at either end. It was designed so that the wealthy guests of nearby Brown’s hotel could have a sheltered and suitably elegant approach to the shops on Bond Street. Apart from being a posh hotel opened in the 1830s by James Brown, Byron’s former valet, Brown’s is famous as the place where the country’s first telephone call was placed by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, though initially he got a crossed line with a private telegraph wire. Also in Albemarle Street, at no. 50, are the offices of John Murray, the publishers of Byron and of the oldest British travel guides. It was here in 1824 that Byron’s memoirs were burnt to cinders, after Murray persuaded Tom Moore, to whom they had been bequeathed, that they were too scurrilous to publish.

Royal Institution

21 Albermarle St • Mon–Fri 9am–6pm • Free • ![]() 020 7409 2992,

020 7409 2992, ![]() rigb.org • _test777

rigb.org • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

The weighty Neoclassical facade at 21 Albermarle Street heralds the Royal Institution, a scientific body founded in 1799 “for teaching by courses of philosophical lectures and experiments the application of science to the common purposes of life”. The RI is best known for its six Christmas Lectures, begun by Michael Faraday and designed to popularize science among schoolchildren, but it also houses an enjoyable interactive museum aimed at both kids and adults. In the basement, you can learn about the ten chemical elements that have been discovered at the RI, and about the famous experiments that have taken place here: Tyndall’s blue-sky tube, Humphry Davy’s early lamps and Faraday’s explorations into electromagnetism – there’s even a reconstruction of Faraday’s lab from the 1850s. The ground floor has displays on the fourteen Nobel Prize winners who have worked at the RI, while on the first floor, you can visit the semicircular hall where the Christmas Lectures take place and see some of the apparatus used in lectures over the decades. There’s also a great café-bar-restaurant on the ground floor.

Savile Row

Running parallel with New Bond Street, to the east, Savile Row has been the place to go for bespoke tailors since the early nineteenth century. Gieves & Hawkes, at no. 1, were the first to establish themselves here back in 1785, with Nelson and Wellington among their first customers – they made the military uniform worn by Prince William at his wedding. More modern in outlook, Kilgour, at no. 8, famously made Fred Astaire’s morning coat for Top Hat, helping to popularize Savile Row tailoring in the US. Henry Poole & Co, who moved to no. 15 in 1846 and has cut suits for the likes of Napoleon III, Dickens, Churchill and de Gaulle, invented the short smoking jacket (originally designed for the future Edward VII), later popularized as the “tuxedo”.

Savile Row also has connections with the pop world. The Beatles used to buy their suits from Tommy Nutter’s House of Nutter established in 1968 at no. 35, and in the same year set up the offices and recording studio of their record label Apple at no. 3, until the building’s near physical collapse in 1972. On January 30, 1969, The Beatles gave an impromptu gig (their last live performance) on the roof here, stopping traffic and eventually attracting the attentions of the local police – as captured on film in Let It Be. More recently feathers have been ruffled in the street by the arrival of the American label, Abercrombie & Fitch, at the southern end of Savile Row, with its trademark semi-nude shop assistants.

Mayfair’s squares

Mayfair has three showpiece Georgian squares: Hanover, the most modest of the three, Berkeley, and Grosvenor, the most grandiose, named after the district’s two big private landowners. Planned as purely residential, all have suffered over the years, and have nothing like the homogeneity of the Bloomsbury squares. Nevertheless, they are still impressive urban spaces, and their social lustre remains more or less untarnished. Each one is worth visiting, and travelling between them gives you a chance to experience Mayfair’s backstreets and, en route, visit one or two hidden sights.

St George’s Church, Hanover Square

1–2 Hanover Square • Mon–Fri 8am–4pm, Wed till–6pm, Sun

8am–noon • Free • ![]() stgeorgeshanoversquare.org • _test777

stgeorgeshanoversquare.org • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

At the very southern tip of Hanover Square stands the Corinthian portico of St George’s Church, the first of its kind in London when it was built in the 1720s. Nicknamed “London’s Temple of Hymen”, it has long been Mayfair’s most fashionable church for weddings. Among those who tied the knot here are the Shelleys, Benjamin Disraeli, Teddy Roosevelt and George Eliot. The composer, Handel, a confirmed bachelor, was a warden here for many years and even had his own pew. North of the church, the funnel-shaped St George Street splays into the square itself, which used to boast the old Hanover Square Rooms venue, where Bach, Liszt, Haydn and Paganini all performed before the building’s demolition in 1900.

Handel House Museum

25 Brook St • Tues–Sat 10am–6pm, Thurs till 8pm, Sun

noon–6pm • £6 • ![]() 020 7495 1685,

020 7495 1685, ![]() handelhouse.org • _test777

handelhouse.org • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

The Handel House Museum, one block west of Hanover Square, is where the composer Handel lived for 36 years from 1723 until his death. He used the ground floor as a shop where subscribers could buy scores, while on the first floor, there was a rehearsal and performance room, plus a composition room at the back. The museum has few original artefacts, but the house has been redecorated to how it would have looked in Handel’s day. Further atmosphere is provided by the harpsichord students who often practise in the rehearsal room; to find out about the regular recitals, visit the website. Access to the house is via the chic, cobbled yard at the back of the house.

HANDEL AND HENDRIX

Born Georg Friedrich Händel (1685–1759) in Halle, Saxony, Handel first visited London in 1710, composing Rinaldo in fifteen days flat. The furore it produced – not least when Handel released a flock of sparrows for one aria – made him a household name. The following year he was commissioned to write several works for Queen Anne, eventually becoming court composer to George I, his one-time patron in Hanover.

London quickly became Handel’s permanent home: he anglicized his name

and nationality and lived out the rest of his life here, producing all

the work for which he is now best known, including the Water Music, the Fireworks Music

and his Messiah, which failed to enthral its

first audiences, but which is now one of the great set pieces of

Protestant musical culture. George II was so moved by the Hallelujah Chorus that he leapt to his feet and

remained standing for the entire performance. Handel himself fainted

during a performance in 1759, and died shortly afterwards in his home,

now a museum; he is buried in Westminster Abbey. Today,

Handel’s birthday is celebrated with a concert at the Foundling Museum, and an annual Handel Festival (![]() london-handel-festival.com) takes place annually at St George’s Church, Hanover

Square.

london-handel-festival.com) takes place annually at St George’s Church, Hanover

Square.

Two centuries later, Jimi Hendrix (1942–70) moved into the top-floor flat of 23 Brook St, next door to Handel’s old address, and lived there for eighteen months or so. Born in Seattle in 1942, Hendrix was persuaded to fly over to London in 1966 by The Animals. Shortly after arriving, he teamed up with two British musicians, Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, and formed The Jimi Hendrix Experience. It was at the beginning of 1969 that Hendrix moved into Brook Street with his girlfriend, Kathy Etchingham; apparently he was much taken with the fact that it was once Handel’s residence, ordering Kathy to go and buy some Handel albums for him. It was also in London that Hendrix met his untimely death, on September 18, 1970. At the Samarkand Hotel in Notting Hill, after a gig at Ronnie Scott’s in Soho, Hendrix, with alcohol still in his system, swallowed a handful of sleeping pills, later vomiting in his sleep and slipping into unconsciousness. He was pronounced dead on arrival at St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, and is buried in Seattle.

Berkeley Square

Berkeley Square is where, according to the music-hall song, nightingales sing (though it’s probable they were, in fact, blackcaps). Laid out in the 1730s, only the west side of the square has any surviving Georgian houses to boast of, including Maggs, at no. 50, the oldest antiquarian booksellers in the world – they also sell signatures and famously bought Napoleon’s penis in 1916. A few doors up, in the basement of the Georgian mansion at no. 44, is Annabel’s, the nightclub where Princess Diana and Sarah Ferguson turned up, dressed as a police officer and a traffic warden, and were refused entry on the grounds that no uniforms were allowed inside. What saves the square aesthetically, however, is its wonderful parade of two hundred-year-old London plane trees. With their dappled, exfoliating trunks, giant lobed leaves and globular spiky fruits, these pollution-resistant trees are a ubiquitous feature of the city, and Berkeley Square’s specimens are among the finest. The square has further royal connections, as the Queen was born just off it, at 17 Bruton St, and then lived at 145 Piccadilly until 1936.

Bourdon House: Alfred Dunhill

2 Davies St • Mon–Sat 10am–7pm • ![]() 020 7853 4440,

020 7853 4440, ![]() dunhill.com • _test777

dunhill.com • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

Just north of Berkeley Square, it’s possible to see inside Bourdon House, a lovely Georgian mansion on the corner of Davies and Bourdon streets. Former private residence of the Duke of Westminster, the house is now the flagship store of Alfred Dunhill. As well as a shop, Dunhill’s has a bar, a barber’s and a screening room where they show classy masculine documentaries. On the first floor, they display a few items from the days of Dunhill Motorities, gadget suppliers to Rolls Royce, whose slogan was “everything but the motor”. This wonderful range made hip flasks disguised as books, “Bobby Finders” for detecting police cars, in-car hookahs and even a motorist’s pipe with a windshield for open-top toking.

Grosvenor Square

Grosvenor Square is the largest of Mayfair’s squares. Its American connections go back to 1785, when John Adams (future US President) established the first American embassy in a house in the northeast corner. During World War II, it was known as “Little America” – General Eisenhower, whose statue stands in the square, ran the D-Day campaign from no. 20. As well as Eisenhower, there are statues of Roosevelt and Reagan, and a memorial garden dedicated to the 67 British victims of 9/11. The entire west side of the square is occupied by the monstrous, heavily guarded US Embassy, built in 1960. The embassy is watched over by a giant gilded aluminium eagle and has been the victim of numerous attacks over the decades. The first major incident occurred in 1967 when Spanish anarchists machine-gunned the embassy in protest against US collaboration with Franco. The most famous (and violent) protest took place in 1968, when a demonstration against US involvement in Vietnam turned into a riot. Mick Jagger, so the story goes, was innocently signing autographs in his Bentley at the time, and later wrote Street Fighting Man, inspired by what he witnessed. Most weeks, there’s some group or other camped out objecting to US foreign policy – in fact, American security concerns are such that in 2016, the embassy will move to a purpose-built $1 billion complex near Vauxhall.

THE CATO STREET CONSPIRACY

Modern British history is notably short on political assassinations: one prime minister, no kings or queens and only a handful of MPs. One of the most dismal failures was the 1820 Cato Street Conspiracy, drawn up by sixteen revolutionaries in an attic off the Edgware Road in Marylebone. Their plan was to decapitate the entire Cabinet as they dined with Lord Harrowby at 44 Grosvenor Square. Having beheaded the Home Secretary and another of the ministers, they then planned to sack Coutts Bank, capture the cannon on the Artillery Ground, take Gray’s Inn, Mansion House, the Bank of England and the Tower, torching the barracks in the process, and proclaiming a provisional government.

As it turned out, one of the conspirators was an agent provocateur, and the entire mob was arrested in the Cato Street attic on the night of the planned coup, February 23, 1820. In the melee, one Bow Street Runner was killed but eventually eleven of the conspirators were arrested and charged with high treason. Five of the ringleaders were hanged at Newgate, and another five were transported to Australia. Public sympathy for the uprising was widespread, so the condemned were spared being drawn and quartered, though they did have their heads cut off afterwards. (The hangman was later attacked in the streets and almost castrated.)

Claridge’s

49 Brook St • ![]() 020 7629 8860,

020 7629 8860, ![]() claridges.co.uk • _test777

claridges.co.uk • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

Claridge’s started out in 1812 as Mivart’s Hotel in a small terraced house, but has grown considerably larger since those days. The current building dates from 1898, has over two hundred rooms, a Gordon Ramsay restaurant, and still attracts Hollywood and pop glitterati from Brad Pitt to U2. Its royal connections are also second to none. Most famously, King Peter II of Yugoslavia spent most of World War II in exile at the hotel – suite 212 was ceded to Yugoslavia for a day on June 17, 1945 so that his son and heir, Crown Prince Alexander, could be born on Yugoslav soil. A room in the hotel, painted “whorehouse pink”, served as General Eisenhower’s initial wartime pied-à-terre, and it was also the wartime hangout of the OSS, forerunner of the CIA. It was here in 1943 that Szmul Zygielbojm, from the Polish government-in-exile, was told that Roosevelt had refused his request to bomb the rail lines leading to Auschwitz; the following day he committed suicide.

Grosvenor Chapel

24 South Audley St • Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri 9am–1pm • Free • ![]() 020 7499 1684,

020 7499 1684, ![]() grosvenorchapel.org.uk • _test777

grosvenorchapel.org.uk • _test777![]() Bond Street or Green Park

Bond Street or Green Park

American troops stationed in Britain used to worship at the Grosvenor Chapel, two blocks south of Claridge’s on South Audley Street, a simple classical building that formed the model for early settlers’ churches in New England and is still popular with the American community. The church’s most illustrious corpse is radical MP John Wilkes (“Wilkes and Liberty” was the battle cry of many a mid-eighteenth-century riot). The interior comes as something of a surprise, however, as it was redesigned in Anglo-Catholic style by Ninian Comper in 1912, and features an elaborate tableau of gilded statuary: Christ crucified is flanked by Mary and one of the disciples, with two angels kneeling below with chalices ready to catch the sacred blood.

Mount Street Gardens: Church of the Immaculate Conception

Farm St • Daily 8am–7pm • Free • ![]() 020 7493 7811,

020 7493 7811, ![]() farmstreet.org.uk • _test777

farmstreet.org.uk • _test777![]() Bond Street or Green Park

Bond Street or Green Park

Built in ostentatious neo-Gothic style in the 1840s, the Church of the Immaculate Conception Farm Street is the London stronghold of the Jesuits, and as such is a fascinating and unusual church. Every surface is covered in decoration, but the reredos of gilded stone by Pugin (of Houses of Parliament fame) is particularly impressive. Behind the chapel are the beautifully secluded Mount Street Gardens, dotted with two hundred-year-old plane trees and enclosed by nineteenth-century red-brick mansions.

Oxford Street

As wealthy Londoners began to move out of the City during the eighteenth century, in favour of the newly developed West End, so Oxford Street – the old Roman road to Oxford – gradually replaced Cheapside as London’s main shopping street. Today, despite successive recessions and sky-high rents, this hotchpotch of shops, over a mile long, is still one of the world’s busiest streets, its Christmas lights switched on by the briefly famous, and its traffic controllers equipped with loud-hailers to prevent the hordes of Christmas shoppers from losing their lives at the busy road junctions. The stretch west of Oxford Circus is slightly more upmarket; east of Oxford Circus, the street forms a scruffy border between Soho and Fitzrovia.

Selfridges

400 Oxford St • Mon 9.30am–7pm, Tues 11am–9pm, Wed–Sat

9.30am–9pm, Sun 11.30am–6.15pm • ![]() selfridges.com • _test777

selfridges.com • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

The one long-standing landmark on Oxford Street is Selfridges, a huge Edwardian department store fronted by giant Ionic columns, with the Queen of Time riding the ship of commerce and supporting an Art Deco clock above the main entrance. Opened in 1909 by Chicago millionaire Harry Gordon Selfridge, Selfridges is the second largest shop in London (after Harrods), and is credited with selling the world’s first television set, as well as introducing the concept of the “bargain basement”, “the customer is always right”, the irritating “only ten more shopping days to Christmas” countdown and the nauseous bouquet of perfumes from the cosmetics counters, strategically placed at the entrance to all department stores. Selfridge himself was a big spender and eventually died in Putney in poverty in 1947 at the age of 90. Today, while Harrods may have the snob value and the longer pedigree, it’s a conservative institution compared to Selfridges, which keeps reinventing itself and successfully remains ahead of the field, particularly in fashion – the window displays alone are worth the journey here.