St James’s

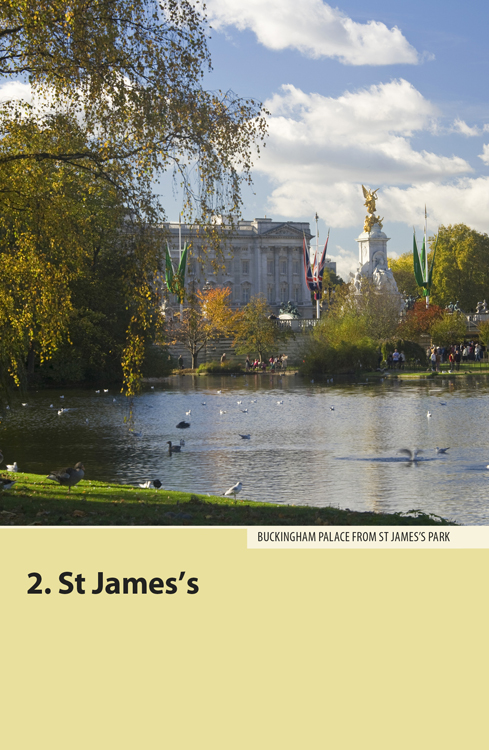

An exclusive little enclave sandwiched between St James’s Park and Piccadilly, St James’s was laid out in the 1670s close to the royal seat of St James’s Palace. Even today, regal and aristocratic residences overlook nearby Green Park and the stately avenue of The Mall; gentlemen’s clubs cluster along Pall Mall and St James’s Street; and jacket-and-tie restaurants and expense-account shops line St James’s and Jermyn Street. Hardly surprising, then, that most Londoners rarely stray into this area, though plenty of folk frequent St James’s Park, with large numbers heading for the Queen’s chief residence, Buckingham Palace. If you’re not in St James’s for the shops, the best time to visit is on a Sunday, when it’s quieter, the nearby Mall is closed to traffic, and the royal chapels, plus Spencer House, the one accessible Palladian mansion, are open to the public.

St James’s Park

St James’s Park is the oldest of London’s royal parks, having been drained and turned into a deer park by Henry VIII. It was redesigned and opened to the public by Charles II, who used to stroll through the grounds with his mistresses and courtiers, feed the ducks and even take a dip in the canal. By the eighteenth century, when some 6500 people had access to night keys for the gates, the park had become something of a byword for robbery and prostitution: diarist James Boswell was among those who went there specifically to be accosted “by several ladies of the town”. The park’s current landscaping was devised by Nash in the 1820s in an elegant style that established a blueprint for later Victorian city parks.

Today, the banks of the tree-lined lake are a favourite picnic spot for the civil servants of Whitehall and an inner-city reserve for wildfowl. James I’s two crocodiles have left no descendants, alas, but the pelicans (which have resided here ever since a pair was presented to Charles II by the Russian ambassador) can still be seen at the eastern end of the lake, and there are exotic ducks, swans and geese aplenty. From the bridge across the lake there’s a fine view over to Westminster and the jumble of domes and pinnacles along Whitehall – even the dull east facade of Buckingham Palace looks majestic from here.

The Mall

![]() St James’s Park, Charing Cross or

Westminster

St James’s Park, Charing Cross or

Westminster

The tree-lined sweep of The Mall – London’s nearest equivalent to a Parisian boulevard (minus the cafés) – is at its best on Sundays, when it’s closed to traffic. It was laid out in the first decade of the twentieth century as a memorial to Queen Victoria, and runs along the northern edge of St James’s Park. The bombastic Admiralty Arch (currently being converted into a hotel) was erected to mark the entrance at the Trafalgar Square end of The Mall, while at the other end stands the ludicrous Victoria Memorial, Edward VII’s overblown 2300-ton marble tribute to his mother: Motherhood and Justice keep Victoria company around the plinth, which is topped by a gilded statue of Victory, while the six outlying allegorical groups in bronze confidently proclaim the great achievements of her reign.

The Mall’s most distinctive building is John Nash’s Carlton House Terrace, whose graceful, cream-coloured Regency

facade lines the north side of The Mall from Admiralty Arch. Among other

things, it serves as the unlikely home of the Institute of Contemporary Arts or ICA (Wed noon–11pm, Thurs–Sat noon–1am, Sun noon–9pm; free;

![]() 020 7930 3647,

020 7930 3647, ![]() ica.org.uk), London’s official headquarters of the avant-garde,

so to speak, which moved here in 1968 and has put on a programme of

regularly provocative exhibitions, films, talks and performances ever since.

A little further down the terrace, there are statues of George VI, erected

in 1955, and his wife, the Queen Mum, erected in 2009 but depicted at the

age she would have been when her husband died – on either side bronze

reliefs depict the couple visiting the East End during the Blitz and having

a day out at the races.

ica.org.uk), London’s official headquarters of the avant-garde,

so to speak, which moved here in 1968 and has put on a programme of

regularly provocative exhibitions, films, talks and performances ever since.

A little further down the terrace, there are statues of George VI, erected

in 1955, and his wife, the Queen Mum, erected in 2009 but depicted at the

age she would have been when her husband died – on either side bronze

reliefs depict the couple visiting the East End during the Blitz and having

a day out at the races.

Wellington Barracks, Guards’ Chapel and Museum

Birdcage Walk • Museum Daily 10am–4pm • £5 • ![]() 020 7414 3271,

020 7414 3271, ![]() theguardsmuseum.com • _test777

theguardsmuseum.com • _test777![]() St James’s Park

St James’s Park

Named after James I’s aviary, which once stood here, Birdcage Walk runs along the south side of St James’s Park, with the Neoclassical facade of the Wellington Barracks, built in 1833 and fronted by a parade ground, occupying more than half its length. Of the various buildings here it’s the modernist lines of the Guards’ Chapel that come as the biggest surprise. Hit by a V1 rocket bomb on the morning of Sunday, June 18, 1944 – killing 121 worshippers – the chapel was rebuilt in the 1960s. Inside, it’s festooned with faded military flags, and retains the ornate Victorian apse, with Byzantine-style gilded mosaics, from the old chapel.

In a bunker opposite is the Guards’ Museum, which displays the glorious scarlet-and-blue uniforms of the Queen’s Foot Guards. The museum also explains the Guards’ complicated history, and gives a potted military history of the country since the Civil War. Among the exhibits are a lock of Wellington’s hair and a whole load of war booty, from Dervish prayer mats plundered from Sudan in 1898 to items taken from an Iraqi POW during the first Gulf War. The museum also displays (and sells) an impressive array of toy soldiers.

Buckingham Palace

The Mall • Late July to Aug daily 9.30am–7pm, Sept

9.30am–6.30pm • State Rooms £19; State Rooms & Garden

Highlights £27.75; booking fee & postage £2.45 per ticket • ![]() 020 7766 7300,

020 7766 7300, ![]() royalcollection.org.uk • _test777

royalcollection.org.uk • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

The graceless colossus of Buckingham Palace, popularly known as “Buck House”, has served as the monarch’s permanent London residence only since Queen Victoria’s reign. It began its days in 1702 as the Duke of Buckingham’s city residence, built on the site of a notorious brothel, and was sold by the duke’s son to George III in 1762. The building was overhauled by Nash in the late 1820s for the Prince Regent, and again by Aston Webb in 1913 for George V, producing a palace that’s about as bland as it’s possible to be.

For ten months of the year there’s little to do here, with the Queen in residence and the palace closed to visitors – not that this deters the crowds who mill around the railings all day, and gather in some force to watch the Changing of the Guard, in which a detachment of the Queen’s Foot Guards marches to appropriate martial music from St James’s Palace (unless it rains, that is). If the Queen is at home, the Royal Standard flies from the roof of the palace and four guards patrol; if not, the Union flag flutters aloft and just two guards stand out front.

Traditionally, unless you were one of the select thirty thousand society debutantes attending a “coming out” party, you had little chance of ever seeing inside Buckingham Palace. The debutantes were given the boot in 1958 and more democratic garden parties were established. Since 1993, however, the hallowed portals have been grudgingly opened for two months of the year. Timed tickets can be purchased online or from the box office on the south side of the palace; queues vary enormously, but you may have some time to wait before your allocated slot.

FROM TOP BUCKINGHAM PALACE; ST JAMES’S PALACE

The interior

Of the palace’s 775 rooms you get to see around twenty of the grandest ones, but with the Queen and her family in Scotland, there’s usually very little sign of life. The visitors’ entrance is via the Ambassadors’ Court on Buckingham Palace Road, which lets you into the enormous Quadrangle, from where you can see the Nash portico, built in warm Bath stone, that used to overlook St James’s Park.

Through the courtyard, you hit the Grand Hall, decorated like some gloomy hotel lobby, from where Nash’s rather splendid winding, curlicued Grand Staircase, with its floral gilt-bronze balustrade and white plaster friezes, leads past a range of very fine royal portraits, all beautifully lit by Nash’s glass dome. Beyond, the small Guard Room leads into the Green Drawing Room, a blaze of unusually bright green silk walls, framed by lattice-patterned pilasters, and a heavily gilded coved ceiling. It was here that the Raphael Cartoons used to hang, until they were permanently loaned to the V&A.

The scarlet and gold Throne Room features a Neoclassical plaster frieze in the style of the Elgin Marbles, depicting the Wars of the Roses. The thrones themselves are disappointingly un-regal – just two pink his ’n’ hers chairs initialled ER and P – whereas George IV’s outrageous sphinx-style chariot seats, nearby, look more the part.

From the Picture Gallery to the Ballroom

Nash originally designed a spectacular hammerbeam ceiling for the Picture Gallery, which stretches right down the centre of the palace. Unfortunately, it leaked and was eventually replaced in 1914 by a rather dull glazed ceiling. Still, the paintings on show here are excellent and include several Van Dycks, two Rembrandts, two Canalettos, a Poussin, a de Hooch and a wonderful Vermeer. Further on, in the East Gallery, check the cherub-fest in the grisaille frieze, before heading into the palace’s rather overwrought Ballroom. It’s here that the Queen holds her State Banquets, where the annual Diplomatic Reception takes place, and where folk receive their honours and knighthoods.

The west facade rooms

Having passed through several smaller rooms, you eventually reach the State Dining Room, whose heavily gilded ceiling, with its three saucer domes, is typical of the suite of rooms that overlooks the palace garden. Next door lies Nash’s not very blue, but incredibly gold, Blue Drawing Room, lined with flock wallpaper interspersed with thirty fake onyx columns. The room contains one of George IV’s most prized possessions, the “Table of the Grand Commanders”, originally made for Napoleon, whose trompe-l’oeil Sèvres porcelain top features cameo-like portraits of military commanders of antiquity.

Beyond the domed Music Room with its enormous semicircular bow window and impressive parquet floor, the White Drawing Room features yet another frothy gold and white Nash ceiling and a superb portrait of Queen Alexandra, wife of Edward VII. This room is also the incongruous setting for an annual royal prank: when hosting the reception for the diplomatic corps, the Queen and family emerge from a secret door behind a mirror to greet the ambassadors. Before you leave the palace, be sure to check out the Canova sculptures: Mars and Venus at the bottom of the Ministers’ Staircase, and the pornographic Fountain Nymph with Putto in the Marble Hall.

If you’ve booked for the Garden Highlights Tour, you’ll now get shown round the Queen’s splendiferous herbaceous border, rose garden and veg patch, plus the wisteria-strewn summer house and the tennis court where George VI and Fred Perry used to knock up in the 1930s. There’s a café overlooking the gardens if you want to linger longer before being ejected onto busy Grosvenor Place, a long walk from the Mall.

Queen’s Gallery

Daily 10am–5.30pm • £9 • ![]() 020 7766 7301 • _test777

020 7766 7301 • _test777![]() Victoria

Victoria

A modern Doric portico on the south side of the palace forms the entrance to the Queen’s Gallery, which puts on temporary exhibitions drawn from the Royal Collection, a superlative array of art that includes works by Michelangelo, Raphael, Holbein, Reynolds, Gainsborough, Vermeer, Van Dyck, Rubens, Rembrandt and Canaletto, as well as the world’s largest collection of Leonardo drawings, the odd Fabergé egg and heaps of Sèvres china. The Queen holds the Royal Collection, which is three times larger than the National Gallery, “in trust for her successors and the nation” – note the word order. However, with over seven thousand works spread over the numerous royal palaces, the Queen’s Gallery and other museums and galleries around the country, you’d have to pay a king’s ransom to see the lot.

Royal Mews

Feb, March & Nov Mon–Sat 10am–4pm;

April–Oct daily 10am–5pm • £8.50 • ![]() 020 7766 7302 • _test777

020 7766 7302 • _test777![]() Victoria

Victoria

On the south side of the palace, along Buckingham Palace Road, you’ll find the Royal Mews, built by Nash in the 1820s. The horses – or at least their backsides – can be viewed in their luxury stables, along with an exhibition of equine accoutrements, but it’s the royal carriages, lined up under a glass canopy in the courtyard, that are the main attraction. The most ornate is the Gold State Coach, made for George III in 1762, smothered in 22-carat gilding and panel paintings by Cipriani, and weighing four tons, its axles supporting four life-size Tritons blowing conches. Eight horses are needed to pull it and the whole experience apparently made Queen Victoria feel quite sick; since then it has only been used for coronations and jubilees. The mews also house the Royal Family’s fleet of five Rolls Royce Phantoms and three Daimlers, none of which is obliged to carry numberplates.

THE ROYAL FAMILY

The popularity of the royal family to foreign tourists never seems to flag, but at home it has always waxed and waned. The Queen herself, in one of her few memorable Christmas Day speeches, accurately described 1992 as her annus horibilis (or “One’s Bum Year” as the Sun put it). That was the year that saw the marriage break-ups of Prince Charles and Prince Andrew, the divorce of Princess Anne, and ended with the fire at Windsor Castle. The royals decided to raise some of the money by opening Buckingham Palace to the public for the first time (and by cranking up the admission charges on all the royal residences).

To try and deflect some of the bad publicity from that year, the Queen agreed to reduce the number of royals paid out of the state coffers, and, for the first time in her life, pay taxes on her personal fortune. The death of Princess Diana in 1997 was a low point for the royals, but their ratings have improved steadily since the new millennium, partly because the family have got much better at PR. Efficiencies and cost-cutting have also taken place, though public subsidy is still considerable, with around £30 million handed over each year in the Sovereign Grant and millions more spent on luxuries such as the Royal Squadron (for air travel) and the Royal Train.

Boosted by the hysteria around the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton (not to mention the arrival of a new heir to the throne), and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee (which coincided with the 2012 Olympics), the Windsors are currently riding high on a wave of good publicity at home. Modernizing continues apace, with female heirs to the throne no longer passed over in preference of younger males, and marriage to a Roman Catholic no longer an issue, although the sovereign still has to be a full-blooded Protestant. However, with none of the mainstream political parties advocating scrapping the monarchy, the royal soap opera looks safe to run for many years to come.

Pall Mall

Running west from Trafalgar Square to St James’s Palace, the wide thoroughfare of Pall Mall is renowned for its gentlemen’s clubs, whose discreet Italianate and Neoclassical facades, fronted by cast-iron torches, still punctuate the street. It gets its bizarre name from the game of pallo a maglio (ball to mallet) – something like modern croquet – popularized by Charles II and played here and on The Mall. Crowds gathered here in 1807 when it became London’s first gas-lit street – the original lampposts (erected to reduce the opportunities for crime and prostitution) are still standing.

Lower Regent Street

Lower Regent Street, a quarter of the way down Pall Mall, was the first stage in John Nash’s ambitious plan to link the Prince Regent’s magnificent Carlton House with Regent’s Park. Like so many of Nash’s grandiose schemes, it never quite came to fruition, as George IV, soon after ascending the throne, decided that Carlton House – the most expensive palace ever to have been built in London – wasn’t quite luxurious enough, and had it pulled down. Its Corinthian columns now support the main portico of the National Gallery.

Waterloo Place

Lower Regent Street opens into Waterloo Place, which Nash extended beyond Pall Mall once Carlton House had been demolished. At the centre of the square stands the Crimean War Memorial, fashioned from captured Russian cannons in 1861, and commemorating the 2152 Foot Guards who died during the Crimean War. The horrors of that conflict were witnessed by Florence Nightingale, whose statue – along with that of Sidney Herbert (Secretary at War at the time) – was added in 1914.

South of Pall Mall, Waterloo Place is flanked by St James’s two grandest gentlemen’s clubs: the former United Services Club (now the Institute of Directors), to the east, and the Athenaeum, to the west. Their almost identical Neoclassical designs are by Nash’s protégé Decimus Burton: the better-looking is the Athenaeum, its portico sporting a garish gilded statue of the goddess Athena and, above, a Wedgwood-type frieze inspired by the Elgin Marbles, which had just arrived in London. The Duke of Wellington was a regular at the United Services Club, and the horse blocks – confusingly positioned outside the Athenaeum – were designed so the duke could mount his steed more easily.

Appropriately enough, an equestrian statue of that eminently clubbable man Edward VII stands between the two clubs. More statues line the railings of nearby Waterloo Gardens: Captain Scott was sculpted by the widow he left behind after failing to complete the return journey from the South Pole; New Zealander Keith Park, the World War I flying ace and RAF commander who organized the fighter defence of London and southeast England during the Battle of Britain, was erected in 2010.

THE GENTLEMEN’S CLUBS

The gentlemen’s clubs of Pall Mall and St James’s Street remain the final bastions of the male chauvinism and public-school snobbery for which England is famous. Their origins lie in the coffee- and chocolate-houses of the eighteenth century, though the majority were founded in the post-Napoleonic peace of the early nineteenth century by those who yearned for the life of the officers’ mess; drinking, whoring and gambling were the major features of early club life. White’s – the oldest of the lot, and with a list of members that still includes numerous royals (Prince Charles held his [first] stag party here), prime ministers and admirals – used to be the unofficial Tory party headquarters, renowned for its high gambling stakes, while, opposite, was the Whigs’ favourite club, Brooks’s. Bets were wagered over the most trivial of things to relieve the boredom – “a thousand meadows and cornfields were staked at every throw” – and in 1755 one MP, Sir John Bland, shot himself after losing £32,000 in one night.

In their day, the clubs were also the battleground of sartorial elegance, particularly Boodle’s, in whose bay window the dandy-in-chief Beau Brummell set the fashion trends for the London upper class and provided endless fuel for gossip. It was said that Brummell’s greatest achievement in life was his starched neckcloth, and that the Prince Regent himself wept openly when Brummell criticized the line of his cravat. More serious political disputes were played out in clubland, too. The Reform Club on Pall Mall, from which Phileas Fogg set off in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, was the gathering place of the liberals behind the 1832 Reform Act, and remains one of the more “progressive” – it was one of the first to admit women as members in 1981. The Tories, led by Wellington, countered by starting up the Carlton Club for those opposed to the Act – bombed by the IRA in 1990, it’s still the leading Conservative club, and only admitted women as full members in 2008 (Mrs Thatcher was made an honorary member).

Duke of York’s Column

To the south of Waterloo Place, overlooking St James’s Park, is the Duke of York’s Column, erected in 1833, ten years before Nelson’s more famous one. The “Grand Old Duke of York”, second son of George III, is indeed the one who marched ten thousand men “up to the top of the hill and…marched them down again” in the famous nursery rhyme. The 123ft column was paid for by stopping one day’s wages of every soldier in the British Army, and it was said at the time that the column was so high because the duke was trying to escape his creditors, since he died £2 million in debt.

Carlton House Terrace

Having pulled his old palace down, George IV had Nash build Carlton House Terrace, whose monumental facade now looks out onto St James’s Park. No. 4, by the exquisitely tranquil Carlton Gardens, was handed to de Gaulle for the headquarters of the Free French during World War II; nos. 7–9, by the Duke of York steps, served as the German embassy until World War II. Albert Speer designed the interior under the Nazis, while outside a tiny grave for ein treuer Begleiter (a true friend) lurks behind the railings near the column – it holds the remains of Giro, the Nazi ambassador’s pet Alsatian, accidentally electrocuted in February 1934.

St James’s Square

Around the time of George III’s birth at no. 31 in 1738, St James’s Square boasted no fewer than six dukes and seven earls, and over the decades it has maintained its exclusive air: no. 10 was occupied in turn by prime ministers Pitt the Elder, Lord Derby and Gladstone; at no. 16 you’ll find the silliest-sounding gentlemen’s club, the East India, Devonshire, Sports and Public Schools’ Club; no. 4 was home to Nancy Astor, the first woman MP to take her seat in parliament, in 1919; while no. 31 was where Eisenhower formed the first Allied HQ during World War II. The narrowest house on the square (no. 14) is the London Library, a private library founded in 1841 by Thomas Carlyle, who got sick of waiting up to two hours for books to be retrieved from the British Library shelves only to find he couldn’t borrow them (he used to steal them instead).

The square is no longer residential and, architecturally, it’s not quite the period piece it once was, but its proportions remain intact, as do the central gardens, which feature an equestrian statue of William III, depicted tripping over on the molehill that killed him at Hampton Court. In the northeastern corner, there’s a memorial marking the spot where police officer Yvonne Fletcher was shot dead in 1984, during a demonstration by Libyan dissidents outside what was then the Libyan embassy, at no. 5. Following the shooting, the embassy was besieged by armed police for eleven days, but in the end the diplomats were simply expelled and no one has ever been charged.

Schomberg House

80–82 Pall Mall

The unusual seventeenth-century mansion of Schomberg House is one of the few to stand out on Pall Mall, thanks to its Dutch-style red brickwork and elongated caryatids. In 1769, the house was divided into three, and the artist, Thomas Gainsborough, who was at the height of his fame, lived in no. 80, the western portion, until his death in 1788. Next door, at no. 81, a Scottish quack doctor, James Graham, ran his Temple of Health and Hymen, where couples having trouble conceiving could try their luck in the “grand celestial bed” for £50 a night (a fortune in those days).

79 Pall Mall

Charles II housed Nell Gwynne at 79 Pall Mall, and even gave her the freehold, so that the two of them could chat over the garden wall, which once backed onto the grounds of St James’s Palace. It was from one of the windows overlooking the garden that Nell is alleged to have dangled her 6-year-old, threatening to drop him if Charles didn’t acknowledge paternity and give the boy a title, at which Charles yelled out “Save the Earl of Burford!”; another, more tabloid-style version of the story alleges that Charles was persuaded only after overhearing Nell saying “Come here, you little bastard”, then excusing herself on the grounds that she had no other name by which to call him.

Marlborough House

Pall Mall • Visits by guided tour only, of groups of

15 or more • ![]() 020 7747 6500,

020 7747 6500, ![]() thecommonwealth.org • _test777

thecommonwealth.org • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

Marlborough House itself is hidden from Marlborough Road by a high, brick wall, and only partly visible from The Mall. Queen Anne sacrificed half her garden in granting this land to her lover, Sarah Jennings, Duchess of Marlborough, in 1709. The duchess, in turn, told Wren to design her a “strong, plain and convenient” palace, only to sack him later and finish the plans off herself. The highlight of the interior is the Blenheim Saloon, with its frescoes depicting the first duke’s eponymous victory, along with ceiling paintings by Gentileschi transferred from the Queen’s House in Greenwich. The royals took over the building in 1817, though the last one to live here was Queen Mary, wife of George V. Since 1965, the palace has been the headquarters of the Commonwealth Secretariat, and can only be visited on a guided tour.

St James’s Palace

St James’s Palace was built on the site of a lepers’ hospital which Henry VIII bought in 1532. Bloody Mary died here in 1558 (her heart and bowels were buried in the Chapel Royal), and it was here that Charles I chose to sleep the night before his execution, so as not to have to listen to his scaffold being erected. When Whitehall Palace burnt down in 1698, St James’s became the principal royal residence and even today it remains the official residence, with every ambassador to the UK accredited to the “Court of St James’s”, even though the monarchy moved over to Buckingham Palace in 1837. The main red-brick gate-tower, which looks out on to St James’s Street, is a survivor from Tudor times; the rest of the modest, rambling, crenellated complex was restored and remodelled by Nash, and now provides a home for Princess Anne and Princess Alexandra and for the staff of princes William and Harry.

Chapel Royal

Open for services only: Oct to Easter Sun

8.30am & 11.15am • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

St James’s Palace is off-limits to the public, with the exception of the Chapel Royal, which is accessed from Cleveland Row. Charles I took Holy Communion in the chapel on the morning of his execution, and here, too, the marriages of William and Mary, George III and Queen Charlotte, Victoria and Albert and George V and Queen Mary took place. One of the few remaining sections of Henry VIII’s palace, it was redecorated in the 1830s, though the gilded strap-work ceiling matches the Tudor original erected to commemorate the brief marriage of Henry and Anne of Cleves (and thought to have been the work of Hans Holbein). The chapel’s musical pedigree is impressive, with Tallis, Byrd, Gibbons and Purcell all having worked here as organists. Purcell even had rooms in the palace, which the poet Dryden used to use in order to hide from his creditors.

Queen’s Chapel

Open for services only: Easter to July Sun

8.30am & 11.15am • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

Despite being on the other side of Marlborough Road, the Queen’s Chapel is officially part of St James’s Palace. A perfectly proportioned classical church, it was designed by Inigo Jones (with Gibbons and Wren helping with the decoration) for the Infanta of Spain, intended child bride of Charles I, and later completed for his French wife, Henrietta Maria, who was also a practising Catholic. A little further down Marlborough Road is the glorious Art Nouveau memorial to Queen Alexandra (wife of Edward VII), the last work of Alfred Gilbert (of Eros fame), comprising a bronze fountain crammed with allegorical figures and flanked by robust lampposts.

Clarence House

Aug Mon–Fri 10am–4pm, Sat & Sun

10am–5.30pm • £9 • ![]() 020 7766 7303,

020 7766 7303, ![]() royalcollection.org.uk • _test777

royalcollection.org.uk • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

John Nash was also responsible for Clarence

House, which is attached to the southwest wing of St James’s

Palace. Built in the 1820s for William IV and used as his principal

residence, it was occupied by various royals until the death of George VI,

after which it became the home of the Queen Mother, George’s widow for

nearly sixty years. It’s currently the official London home of Charles and

Camilla (![]() princeofwales.gov.uk), but a handful of rooms can be visited over

the summer when the royals are in Scotland. Visits (by guided tour) must be

booked in advance, as they are extremely popular. The rooms are pretty

unremarkable, so apart from a peek behind the scenes in a working royal

palace, or a few mementoes of the Queen Mum, the main draw is the

twentieth-century British paintings on display by the likes of Walter

Sickert and Augustus John.

princeofwales.gov.uk), but a handful of rooms can be visited over

the summer when the royals are in Scotland. Visits (by guided tour) must be

booked in advance, as they are extremely popular. The rooms are pretty

unremarkable, so apart from a peek behind the scenes in a working royal

palace, or a few mementoes of the Queen Mum, the main draw is the

twentieth-century British paintings on display by the likes of Walter

Sickert and Augustus John.

St James’s Street and Jermyn Street

St James’s Street and Jermyn Street (pronounced “German Street”), have been, along with Savile Row in Mayfair, the spiritual home of English gentlemen’s fashion since the advent of the clubs. The window displays and wooden-panelled interiors (see Hidden gems: Shops and signage) still evoke an age when mass consumerism was unthinkable, and when it was considered that gentlemen “should either be a work of art or wear a work of art”, as Oscar Wilde put it.

HIDDEN GEMS: SHOPS AND SIGNAGE

As you stroll along St James’s and Jermyn streets keep an eye out for some of the unique shops and signs – antiquated epithets are part of Jermyn Street’s quaint appeal – including:

Berry Brothers 3 St James’s St. The oldest wine merchants in the world, with acres of cellars, and a sloping wooden floor of great antiquity.

James Lock & Co 6 St James’s St. The first hatters to sell a bowler hat, they have the Duke of Wellington’s hat on display, alongside a replica of the cocked hat they made for Nelson.

Fox of St James 19 St James’s St. Fox supplied Winston Churchill with his cigars and Oscar Wilde with Sobranie cigarettes – there’s a small museum inside and a smoking room for sampling the wares.

Turnbull & Asser 71–72 Jermyn St. Describe themselves as “Hosiers & Glovers”.

Bates the hatters, housed within the shirtmakers Hadditch & Key, 73 Jermyn St. Bates still displays Binks, the stray cat which entered the shop in 1921 and never left, having been stuffed, sporting a cigar and top hat, and in a glass cabinet.

Taylor 74 Jermyn St. These barbers are dubbed “Gentlemen’s Court Hairdresser”.

Foster & So 85 Jermyn St. A shoe shop that styles themselves as “Bootmakers since 1840”.

Floris 89 Jermyn St. Renowned for covering up the Royal Family’s body odour with its ever-so-English fragrances.

Paxton & Whitfield 93 Jermyn St. Boasts an unrivalled selection of cheeses.

Green Park

Green Park was established by Henry VIII on the burial ground of the old lepers’ hospital that became St James’s Palace. It was left more or less flowerless – hence its name (officially “The Green Park”) – and, apart from the springtime swathes of daffodils and crocuses, it remains mostly meadow, shaded by graceful London plane trees. In its time, however, it was a popular place for duels (banned from neighbouring St James’s Park), ballooning and fireworks displays. One such display was immortalized by Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks, performed here on April 27, 1749, to celebrate the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the War of the Austrian Succession – over ten thousand fireworks were let off, setting fire to the custom-built Temple of Peace and causing three fatalities. The music was a great success, however.

Along the east side of the park runs the wide, pedestrian-only Queen’s Walk, laid out for Queen Caroline, wife of George II, who had a little pavilion built nearby. At its southern end, there’s a good view of Lancaster House (closed to the public), a grand Neoclassical palace built in rich Bath stone in the 1820s by Benjamin Wyatt, and used for government receptions and conferences since 1913.

Spencer House

St James’s Place • Feb–July & Sept–Dec Sun

10.30am–5.45pm • £12, no under-10s • ![]() 020 7499 8620,

020 7499 8620, ![]() spencerhouse.co.uk • _test777

spencerhouse.co.uk • _test777![]() Green Park

Green Park

A sign in the garden backing onto Queen’s Walk announces Princess Diana’s ancestral home, Spencer House, one of London’s finest Palladian mansions. Erected in the 1750s, its best-looking facade looks out over Queen’s Walk to Green Park, though access is from St James’s Place. Inside, tour guides take you through nine of the state rooms, returned to something like their original condition by current owners, the Rothschilds. The Great Room features a stunning coved and coffered ceiling in green, white and gold, while the adjacent Painted Room is a feast of Neoclassicism, decorated with murals in the “Pompeian manner”. The most outrageous decor, though, is in Lord Spencer’s Room, with its astonishing gilded palm-tree columns.