HISTORY

The citizens of London are universally held up for admiration and renown for the elegance of their manners and dress, and the delights of their tables…The only plagues of London are the immoderate drinking of fools and the frequency of fires.

Conflagrations and drunkenness certainly feature strongly in London’s complex two-thousand-year history. What follows is a highly compressed account featuring riots and revolutions, plagues, fires, slum clearances, lashings of gin, Boris Johnson and the London people. For more detailed histories, see our book recommendations.

Roman Londinium

Although there is evidence of scattered Celtic settlements along the Thames, no firm proof exists to show that central London was permanently settled before the arrival of the Romans. Julius Caesar led two small cross-Channel incursions in 55 and 54 BC, but it wasn’t until nearly a century later, in 43 AD, that a full-scale invasion force of some forty thousand Roman troops landed in Kent. Britain’s rumoured mineral wealth was certainly one motive behind the Roman invasion, but the immediate spur was the need of Emperor Claudius, who owed his power to the army, for an easy military triumph. The Romans, under Aulus Plautius, defeated the main Celtic tribe of southern Britain, the Catuvellauni, on the Medway, southeast of London, crossed the Thames and then set up camp to await the triumphant arrival of Claudius, his elephants and the Praetorian Guard.

It’s now thought that the site of this first Roman camp was, in fact, in Westminster – the lowest fordable point on the Thames – and not in what is now the City. However, around 50 AD, when the Romans decided to establish the permanent military camp of Londinium here, they chose a point further downstream, building a bridge some 50yd east of today’s London Bridge. London became the hub of the Roman road system, but it was not the Romans’ principal colonial settlement, which remained at Camulodunum (modern Colchester) to the northeast.

In 60 AD, the East Anglian people, known as the Iceni, rose up against the invaders under their queen Boudicca (or Boadicea) and sacked Camulodunum, slaughtering most of the legion sent from Lindum (Lincoln) and making their way to the ill-defended town of Londinium. According to archeological evidence, Londinium was burnt to the ground and, according to the Roman historian Tacitus, whose father-in-law was in Britain at the time (and later served as its governor), the inhabitants were “massacred, hanged, burned and crucified”. The Iceni were eventually defeated, and Boudicca committed suicide (62 AD).

In the aftermath, Londinium emerged as the new commercial and administrative (though not military) capital of Britannia, and was endowed with a military fort for around a thousand troops, an imposing basilica and forum, a governor’s palace, temples, bathhouses and an amphitheatre. Archeological evidence suggests that Londinium was at its most prosperous and populous from around 80 AD to 120 AD, during which time it is thought to have evolved into the empire’s fifth largest city north of the Alps.

Between 150 AD and 400 AD, however, London appears to have sheltered less than half the former population, probably due to economic decline. Nevertheless, it remained strategically and politically important and, as an imperial outpost, actually appears to have benefited from the chaos that engulfed the rest of the empire during much of the third century. In those uncertain times, fortifications were built, three miles long, 20ft high and 9ft thick, whose Kentish ragstone walls can still be seen near today’s Museum of London, home to many of the city’s most significant Roman finds.

In 406 AD, the Roman army in Britain mutinied for the last time and invaded Gaul under the self-proclaimed Emperor Constantine III. The empire was on its last legs, and the Romans were never in a position to return, officially abandoning the city in 410 AD (when Rome was sacked by the Visigoths), and leaving the country and its chief city at the mercy of the marauding Saxon pirates, who had been making increasingly persistent raids on the coast since the middle of the previous century.

LEGENDS

Until Elizabethan times, most Londoners believed that London had been founded around 1000 BC as New Troy or Troia Nova (later corrupted to Trinovantum), capital of Albion (aka Britain), by the Trojan prince Brutus. At the time, according to medieval chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth, Britain was “uninhabited except for a few giants”, several of whom the Trojans subsequently killed. They even captured one called Goemagog (more commonly referred to as Gogmagog), who was believed to be the son of Poseidon, Greek god of the sea, and whom one of the Trojans, called Corineus, challenged to unarmed combat and defeated.

For some reason, by late medieval times, Gogmagog had become better known as two giants, Gog and Magog, whose statues can still be seen in the Guildhall and on the clock outside St Dunstan-in-the-West. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s elaborate genealogical tree, Brutus is related to Leir (of Shakespeare’s King Lear), Arthur (of the Round Table) and eventually to King Lud. Around 70 BC, Lud is credited with fortifying New Troy and renaming it Caer Ludd (Lud’s Town), which was later corrupted to Caerlundein and finally London.

Saxon Lundenwic and the Danes

Roman London appears to have been more or less abandoned from the first couple of decades of the fifth century until the ninth century. Instead, the Anglo-Saxon invaders, who controlled most of southern England by the sixth century, appear to have settled, initially at least, to the west of the Roman city. When Augustine was sent to reconvert Britain to Christianity, the Saxon city of Lundenwic was considered important enough to be granted a bishopric in 604, though it was Canterbury, not London, that was chosen as the seat of the Primate of England. Nevertheless, trade flourished once more during this period, as attested by the Venerable Bede, who wrote of London in 730 as “the mart of many nations resorting to it by land and sea”.

In 841 and 851 London suffered Danish Viking attacks, and it may have been in response to these raids that the Saxons decided to reoccupy the walled Roman city. By 871 the Danes were confident enough to attack and established London as their winter base, but in 886 Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, recaptured the city, rebuilt the walls and formally re-established London as a fortified town and a trading port. After a lull, the Vikings returned once more during the reign of Ethelred the Unready (978–1016), attacking in 994, 1009 and 1013. Finally the Danes, under Swein Forkbeard, captured London, and Swein was declared King of England. He reigned for just five weeks before he died, allowing Ethelred to reclaim the city in 1014, with help from King Olaf of Norway.

In 1016, following the death of Ethelred, and his son, Edmund Ironside, the Danish leader Cnut (or Canute), son of Swein, became King of All England, and made London the national capital (in preference to the Wessex base of Winchester), a position it has held ever since. Danish rule lasted only 26 years, however, and with the death of Cnut’s two sons, the English throne returned to the House of Wessex, and to Ethelred’s exiled son, Edward the Confessor (1042–66). Edward moved the court and church upstream to Thorney Island (or the Isle of Brambles), where he built a splendid new palace so that he could oversee construction of his “West Minster” (later to become Westminster Abbey). Edward was too weak to attend the official consecration and died just ten days later: he is buried in the great church he founded, where his shrine became a place of pilgrimage for centuries. Of greater political and social significance, however, was his geographical separation of power, with royal government based in the City of Westminster, while the City of London remained the commercial centre.

1066 and all that

On his deathbed, in the new year of 1066, the celibate Edward made Harold, Earl of Wessex, his appointed successor. Having crowned himself in the new abbey – establishing a tradition that continues to this day – Harold went on to defeat his brother Tostig (who was in cahoots with the Norwegians), but was himself defeated by William of Normandy (aka William the Conqueror) and his invading Norman army at the Battle of Hastings. On Christmas Day of 1066, William crowned himself king in Westminster Abbey. Elsewhere in England, the Normans ruthlessly suppressed all opposition, but in London, William granted the City a charter guaranteeing to preserve the privileges it had enjoyed under Edward. However, as an insurance policy, he also built three forts in the city, of which the sole remnant is the White Tower, now the nucleus of the Tower of London.

Over the next few centuries, the City waged a continuous struggle with the monarchy for a degree of self-government and independence. After all, when there was a fight over the throne, the support of London’s wealth and manpower could be decisive, as King Stephen (1135–54) discovered, when Londoners attacked his cousin and rival for the throne, Mathilda, daughter of Henry I, preventing her from being crowned at Westminster. Again, in 1191, when the future King John (1199–1216) was tussling with William Longchamp over the kingdom during the absence of Richard the Lionheart (1189–99), it was the Londoners who made sure Longchamp remained cooped up in the Tower. For this particular favour, London was granted the right to elect its own sheriff, or lord mayor, an office that was officially acknowledged in the Magna Carta of 1215.

Occasionally, of course, Londoners backed the wrong side, as they did when they turned up at Old St Paul’s to accept Prince Louis of France (the future Louis VIII) as ruler of England during the barons’ rebellion against King John in 1216, and again with Simon de Montfort, when he was engaged in civil war with Henry III (1216–72) during the 1260s. As a result, the City found itself temporarily stripped of its privileges. In any case, London was chiefly of importance to the medieval kings as a source of wealth, and traditionally it was to the Jewish community, which arrived in 1066 with William the Conqueror, that the sovereign turned for a loan. By the second half of the thirteenth century, however, the Jews had been squeezed dry, and in 1290, after a series of increasingly bloody attacks, London’s Jews were expelled by Edward I (1272–1307), who turned instead to the City’s Italian merchants for financial assistance.

From the Black Death to the Wars of the Roses

London backed the right side in the struggle between Edward II (1307–27) and his queen, Isabella, who, along with her lover Mortimer, succeeded in deposing the king. The couple’s son Edward III (1327–77) was duly crowned, and London enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity, thanks to the wealth generated by the wool trade. All this was cut short, however, by the arrival of the Europe-wide bubonic plague outbreak, known as the Black Death, in 1348. This disease, carried by black rats and transmitted to humans by flea bites, wiped out something like two-thirds of the capital’s 75,000 population in the space of two years. Other epidemics followed in 1361, 1369 and 1375, creating a volatile economic situation that was worsened by the financial strains imposed on the capital by having to bankroll the country’s involvement in the Hundred Years’ War with France.

Matters came to a head with the introduction of the poll tax, a head tax imposed in the 1370s on all men regardless of means. During the ensuing Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, London’s citizens opened the City gates to Wat Tyler’s Kentish rebels and joined in the lynching of the archbishop, plus countless rich merchants and clerics. Tyler was then lured to meet the boy-king Richard II at Smithfield, just outside the City, where he was murdered by Lord Mayor Walworth, who was subsequently knighted for his treachery. Tyler’s supporters were fobbed off with promises of political changes that never came, as Richard unleashed a wave of repression and retribution.

After the Peasants’ Revolt, the next serious disturbance was Jack Cade’s Revolt, which took place in 1450. An army of 25,000 Kentish rebels – including gentry, clergy and craftsmen – defeated King Henry VI’s forces at Sevenoaks, marched to Blackheath, withdrew temporarily and then eventually reached Southwark in early July. Having threatened to burn down London Bridge, the insurgents entered the City and spent three days wreaking vengeance on their enemies before being ejected. A subsequent attempt to enter the City via London Bridge was repulsed, and the army was dispersed with yet more false promises. The reprisals, which became known as the “harvest of heads”, were as harsh as before – Cade himself was captured, killed and brought to the capital for dismemberment.

A decade later, the country was plunged into more widespread conflict during the so-called Wars of the Roses, the name now given to the strife between the cousins within the rival noble houses of Lancaster and York. Londoners wisely tended to sit on the fence throughout the conflict, only committing themselves in 1461, when they opened the gates to the Yorkist king Edward IV (1461–70 and 1471–83), thus helping him to depose the mad Henry VI (1422–61 and 1470–71). In 1470, Henry, who had spent five years in the Tower, was proclaimed king once more, only to be deposed again a year later, following Lancastrian defeats at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury.

JOHN WYCLIFFE AND THE LOLLARDS

Parallel with the social unrest of the 1370s were the demands for clerical reforms made by the scholar and heretic John Wycliffe, whose ideas were keenly taken up by Londoners. A fierce critic of the papacy and the monastic orders, Wycliffe produced the first translation of the Bible into English in 1380. He was tried for heresy at Lambeth Palace, and his followers, known as Lollards, were harshly persecuted. In 1415, the Council of Constance, which burned the Czech heretic Jan Hus at the stake, also ordered Wycliffe’s body to be exhumed and burnt.

Tudor London

The Tudor family, which with the coronation of Henry VII (1485–1509) emerged triumphant from the mayhem of the Wars of the Roses, reinforced London’s pre-eminence during the sixteenth century, when the Tower of London and the royal palaces of Whitehall, St James’s, Richmond, Greenwich, Hampton Court and Windsor provided the backdrop for the most momentous events of the period. At the same time, the city’s population, which had remained constant at around fifty thousand since the Black Death, increased dramatically, trebling in size during the course of the century.

One of the crucial developments of the century was the English Reformation, the separation of the English Church from Rome, a split initially prompted not by doctrinal issues, but by the failure of Catherine of Aragon, first wife of Henry VIII (1509–47), to produce a male heir. In fact, prior to his desire to divorce Catherine, Henry, along with his lord chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey, had been zealously persecuting Protestants. However, when the Pope refused to annul Henry’s marriage, Henry knew he could rely on a large amount of popular support, as anti-clerical feelings were running high. By contrast, Henry’s new chancellor, Thomas More, wouldn’t countenance divorce, and resigned in 1532. Henry then broke with Rome, appointed himself head of the English Church and demanded both citizens and clergy swear allegiance to him. Very few refused, though More was among them, becoming the country’s first Catholic martyr with his execution in 1535.

Henry may have been the one who kickstarted the English Reformation, but he was a religious conservative, and in the last ten years of his reign he succeeded in executing as many Protestants as he did Catholics. Religious turmoil only intensified in the decade following Henry’s death. First, Henry’s sickly son, Edward VI (1547–53), pursued a staunchly anti-Catholic policy. By the end of his short reign, London’s churches had lost their altars, their paintings, their relics and virtually all their statuary. After an abortive attempt to secure the succession of Edward’s Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey, the religious pendulum swung the other way for the next five years with the accession of “Bloody Mary” (1553–58). This time, it was Protestants who were martyred with abandon at Tyburn and Smithfield.

Despite all the religious strife, the Tudor economy remained in good health for the most part, reaching its height in the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603), when the piratical exploits of seafarers Walter Raleigh, Francis Drake, Martin Frobisher and John Hawkins helped to map out the world for English commerce. London’s commercial success was epitomized by the millionaire merchant Thomas Gresham, who erected the Royal Exchange in 1571, establishing London as the premier world trade market.

The 45 years of Elizabeth’s reign also witnessed the efflorescence of a specifically English Renaissance, especially in the field of literature, which reached its apogee in the brilliant careers of Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare. The presses of Fleet Street, established a century earlier by William Caxton’s apprentice Wynkyn de Worde, ensured London’s position as a centre for the printed word. Beyond the jurisdiction of the City censors, in the entertainment district of Southwark, whorehouses, animal-baiting pits and theatres flourished. The carpenter-cum-actor James Burbage designed the first purpose-built playhouse in 1576, eventually rebuilding it south of the river as the Globe Theatre, where Shakespeare premiered many of his works. The theatre has since been reconstructed.

DISSOLUTION OF THE MONASTERIES

Henry’s VIII’s most far-reaching act was his Dissolution of the Monasteries; a programme to close down the country’s monasteries and appropriate their assets, commenced in 1536 in order to bump up the royal coffers. Medieval London boasted over a hundred places of worship and some twenty religious houses, with two-thirds of the land in the City belonging to the Church. The Dissolution changed the entire fabric of both the city and the country: London’s property market was suddenly flooded with confiscated estates, which were quickly snapped up and redeveloped by the Tudor nobility.

From Gunpowder Plot to Civil War

On Elizabeth’s death in 1603, James VI of Scotland became James I (1603–25) of England, thereby uniting the two crowns and marking the beginning of the Stuart dynasty. His intention of exercising religious tolerance after the anti-Catholicism of Elizabeth’s reign was thwarted by the public outrage that followed the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, when Guy Fawkes and a group of Catholic conspirators were discovered attempting to blow up the king at the state opening of Parliament. James, who clung to the medieval notion of the divine right of kings, inevitably clashed with the landed gentry who dominated Parliament, and tensions between Crown and Parliament were worsened by his persecution of the Puritans, an extreme but increasingly powerful Protestant group.

Under James’s successor, Charles I (1625–49), the animosity between Crown and Parliament came to a head. From 1629 to 1640 Charles ruled without the services of Parliament, but was forced to recall it when he ran into problems in Scotland, where he was attempting to subdue the Presbyterians. Faced with extremely antagonistic MPs, Charles attempted unsuccessfully to arrest several of their number at Westminster. Acting on a tip-off, the MPs fled by river to the City, which sided with Parliament. Charles withdrew to Nottingham, where he raised his standard, the opening military act of the Civil War. London was the key to victory, and as a Parliamentarian stronghold it came under attack almost immediately from Royalist forces. Having defeated the Parliamentary troops to the west of London at Brentford in November 1642, the way was open for Charles to take the capital. Londoners turned out in numbers to defend their city, some 24,000 assembling at Turnham Green. A stand-off ensued, Charles hesitated and in the end withdrew to Reading, thus missing his greatest chance of victory. A complex system of fortifications was thrown up around London, but was never put to the test. In the end, the capital remained intact throughout the war, which culminated in the execution of the king outside Whitehall’s Banqueting House in January 1649.

For the next eleven years England was a Commonwealth – at first a true republic, then, after 1653, a Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell, who was ultimately as impatient of Parliament and as arbitrary as Charles had been. London found itself in the grip of the Puritans’ zealous laws, which closed down all theatres, enforced observance of the Sabbath and banned the celebration of Christmas, which was considered a papist superstition.

Plague and fire

Just as London proved Charles I’s undoing, so the ecstatic reception given to Charles II (1660–85) helped ease the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The “Merry Monarch” immediately caught the mood of the public by opening up the theatres, and he encouraged the sciences by helping the establishment of the Royal Society for Improving Natural Knowledge, whose founder members included Christopher Wren, John Evelyn and Isaac Newton.

The good times that rolled in the early period of Charles’s reign came to an abrupt end with the onset of the Great Plague of 1665. Epidemics of bubonic plague were nothing new to London – there had been major outbreaks in 1593, 1603, 1625, 1636 and 1647 – but the combination of a warm summer and the chronic overcrowding of the city proved calamitous in this instance. Those with money left the city (the court moved to Oxford), while the poorer districts outside the City were the hardest hit. The extermination of the city’s dog and cat population – believed to be the source of the epidemic – only exacerbated the situation by allowing the flea-carrying rat population to explode. In September, the death toll peaked at twelve thousand a week, and in total an estimated hundred thousand lost their lives.

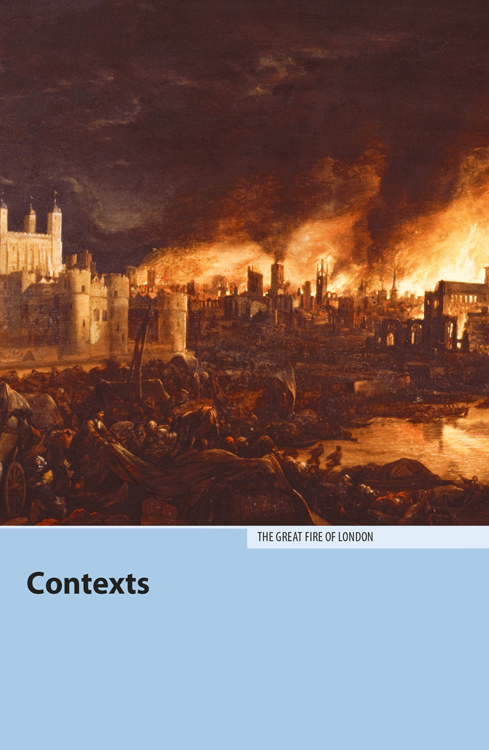

A cold snap in November extinguished the plague, but the following year London had to contend with yet another disaster, the Great Fire of 1666. As with the plague, outbreaks of fire were fairly commonplace in London, whose buildings were predominantly timber-framed, and whose streets were narrow, allowing fires to spread rapidly. However, this particular fire raged for five days and destroyed some four-fifths of the City of London.

Within five years, nine thousand houses had been rebuilt with bricks and mortar (timber was banned), and fifty years later Christopher Wren had almost single-handedly rebuilt all the City churches and completed the world’s first purpose-built Protestant cathedral, St Paul’s. Medieval London was no more, though the grandiose masterplans of Wren and other architects had to be rejected due to the legal intricacies of property rights within the City. The Great Rebuilding, as it was known, was one of London’s most remarkable achievements – and all achieved in spite of a chronic lack of funds, a series of very severe winters and continuing wars against the Dutch.

Religious differences once again came to the fore with the accession of Charles’s Catholic brother, James II (1685–88), who successfully put down the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, but failed to halt the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, which brought the Dutch king William of Orange to the throne, much to most people’s relief. William (1689–1702) and his wife Mary (1689–95), daughter of James II, were made joint sovereigns, having agreed to a Bill of Rights defining the limitations of the monarch’s power and the rights of his or her subjects. This, together with the Act of Settlement of 1701 – which among other things barred Catholics, or anyone married to one, from succession to the throne – made Britain the first country in the world to be governed by a constitutional monarchy, in which the roles of legislature and executive were separate and interdependent. A further development during the reign of Anne (1702–14), second daughter of James II, was the Act of Union of 1707, which united the English and Scottish parliaments.

THE GREAT FIRE

In the early hours of September 2, 1666, the Great Fire broke out at Farriner’s, the king’s bakery in Pudding Lane. The Lord Mayor refused to lose any sleep over it, dismissing it with the line “Pish! A woman might piss it out.” Pepys was also roused from his bed, but saw no cause for alarm. Four days and four nights later, the Lord Mayor was found crying “like a fainting woman”, and Pepys had fled, having famously buried his Parmesan cheese in the garden: the Fire had destroyed some four-fifths of the City of London, including 87 churches, 44 livery halls and 13,200 houses. The medieval city was no more.

Miraculously, there were only eight recorded fatalities, but one hundred thousand people were made homeless. “The hand of God upon us, a great wind and the season so very dry”, was the verdict of the parliamentary report on the Fire, but Londoners preferred to blame Catholics and foreigners. The poor baker eventually “confessed” to being an agent of the pope and was executed, after which the following words, “but Popish frenzy, which wrought such horrors, is not yet quenched”, were added to the Latin inscription on the Monument, and only erased in 1830.

Georgian London

When Queen Anne died childless in 1714 (despite having given birth seventeen times), the Stuart line ended, though pro-Stuart or Jacobite rebellions continued on and off until 1745. In accordance with the Act of Settlement, the succession passed to a non-English-speaking German, the Duke of Hanover, who became George I (1714–27) of England. As power leaked from the monarchy, the king ceased to attend cabinet meetings (which he couldn’t understand anyway), his place being taken by his chief minister. Most prominent among these chief ministers or “prime ministers”, as they became known, was Robert Walpole, the first politician to live at 10 Downing Street, and effective ruler of the country from 1721 to 1742.

Meanwhile, London’s expansion continued unabated. The shops of the newly developed West End stocked the most fashionable goods in the country, the volume of trade more than tripled and London’s growing population – it was by now the largest city in the world, with a population rapidly approaching one million – created a huge market for food and other produce, as well as fuelling a building boom. In the City, the Bank of England – founded in 1694 to raise funds to conduct war against France – was providing a sound foundation for the economy. It could not, however, prevent the mania for financial speculation that resulted in the fiasco of the South Sea Company, which in 1720 sold shares in its monopoly of trade in the Pacific and along the east coast of South America. The “bubble” burst when the shareholders took fright at the extent of their own investments, and the value of the shares dropped to nothing, reducing many to penury and almost wrecking the government, which was saved only by the astute intervention of Walpole.

Wealthy though London was, it was also experiencing the worst mortality rates since records began in the reign of Henry VIII. Disease was rife in the overcrowded immigrant quarter of the East End and other slum districts, but the real killer during this period was gin.

Policing the metropolis was an increasing preoccupation for the government. It was proving a task far beyond the city’s three thousand beadles, constables and nightwatchmen, who were, in any case, “old men chosen from the dregs of the people who have no other arms but a lantern and a pole”, according to one French visitor. As a result, crime continued unabated throughout the eighteenth century, so that, in the words of Horace Walpole, one was “forced to travel even at noon as if one was going into battle”. The government imposed draconian measures, introducing capital punishment for the most minor misdemeanours. The prison population swelled, transportations began and 1200 Londoners were hanged at Tyburn’s gallows.

Despite such measures, and the passing of the Riot Act in 1715, rioting remained a popular pastime among the poorer classes in London. Anti-Irish riots had taken place in 1736; in 1743 there were further riots in defence of cheap liquor; and in the 1760s there were more organized mobilizations by supporters of the great agitator John Wilkes, calling for political reform. The most serious insurrection of the lot, however, were the Gordon Riots of 1780, when up to fifty thousand Londoners went on a five-day rampage through the city. Although anti-Catholicism was the spark that lit the fire, the majority of the rioters’ targets were chosen not for their religion but for their wealth. The most dramatic incidents took place at Newgate Prison, where thousands of inmates were freed, and at the Bank of England, which was saved only by the intervention of the military – and John Wilkes, of all people. The death toll was in excess of three hundred, 25 rioters were subsequently hanged, and further calls were made in Parliament for the establishment of a proper police force.

THE GIN CRAZE

It’s difficult to exaggerate the effects of the gin-drinking orgy which took place among the poorer sections of London’s population between 1720 and 1751. At its height, ginconsumption was averaging two pints a week for every man, woman and child, and the burial rate exceeded the baptism rate by more than 2:1. The origins of this lay in the country’s enormous surplus of corn, which had to be sold in some form or another to keep the landowners happy. Deregulation of the distilling trade was Parliament’s answer, thereby flooding the urban market with cheap, intoxicating liquor, which resulted in an enormous increase in crime, prostitution, child mortality and general misery among the poor. Papers in the Old Bailey archives relate a typical story of the period: a mother who “fetched her child from the workhouse, where it had just been ‘new-clothed’, for the afternoon. She strangled it and left it in a ditch in Bethnal Green in order to sell its clothes. The money was spent on gin.” Eventually, in the face of huge vested interests, the government was forced to pass an Act in 1751 that restricted gin retailing and brought the epidemic to a halt.

Nineteenth-century London

The nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of London as the capital of an empire that stretched across the globe. The world’s largest enclosed dock system was built in the marshes to the east of the City, Tory reformer Robert Peel established the world’s first civilian policeforce and the world’s first public-transport network was created, with horse-buses, trains, trams and an underground railway.

The city’s population grew dramatically from just over one million in 1801 (the first official census) to nearly seven million by 1901. Industrialization brought pollution and overcrowding, especially in the slums of the East End. Smallpox, measles, whooping cough and scarlet fever killed thousands of working-class families, as did the cholera outbreaks of 1832 and 1848–49. The Poor Law of 1834 formalized workhouses for the destitute, but these failed to alleviate the problem, in the end becoming little more than prison hospitals for the penniless. It is this era of slum life and huge social divides that Dickens evoked in his novels.

Architecturally, London was changing rapidly. George IV (1820–30), who became Prince Regent in 1811 during the declining years of his father, George III, instigated several grandiose projects that survive to this day. With the architect John Nash, he laid out London’s first planned processional route, Regent Street, and a prototype garden city around Regent’s Park. The Regent’s Canal was driven through the northern fringe of the city, and Trafalgar Square began to take shape. The city already boasted the first secular public museum in the world, the British Museum, and in 1814 London’s first public art gallery opened in the suburb of Dulwich, followed shortly afterwards by the National Gallery, founded in 1824. London finally got its own university, too, in 1826.

The accession of Queen Victoria (1837–1901) coincided with a period in which the country’s international standing reached unprecedented heights, and as a result Victoria became as much a national icon as Elizabeth I had been. Though the intellectual achievements of Victoria’s reign were immense – typified by the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859 – the country saw itself above all as an imperial power founded on industrial and commercial prowess. Its spirit was perhaps best embodied by the great engineering feats of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and by the Great Exhibition of 1851, a display of manufacturing achievements from all over the world, which took place in the Crystal Palace, erected in Hyde Park.

Despite being more than twice the size of Paris, London did not experience the political upheavals of the French capital – the terrorists who planned to wipe out the cabinet in the 1820 Cato Street Conspiracy were the exception. Mass demonstrations and the occasional minor fracas preceded the passing of the 1832 Reform Act, which acknowledged the principle of popular representation (though few men and no women had the vote), but there was no real threat of revolution. London doubled its number of MPs in the new parliament, but its own administration remained dominated by the City oligarchy.

THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT IN LONDON

The Chartist movement, which campaigned for universal male suffrage (among other things), was much stronger in the industrialized north than in the capital, at least until the 1840s. Support for the movement reached its height in the revolutionary year of 1848. In March, some ten thousand Chartists occupied Trafalgar Square and held out against the police for two days. Then, on April 10, the Chartists organized a mass demonstration on Kennington Common. The government panicked and drafted in eighty thousand “special constables” to boost the capital’s four thousand police officers, and troops were garrisoned around all public buildings. In the end, London was a long way off experiencing a revolution: the demo took place, but the planned march on Parliament was called off.

The birth of local government

The first tentative steps towards a cohesive form of metropolitan government were taken in 1855 with the establishment of the MetropolitanBoard of Works (MBW). Its initial remit only covered sewerage, lighting and street maintenance, but it was soon extended to include gas, fire services, public parks and slum clearance. The achievements of the MBW – and in particular those of its chief engineer, Joseph Bazalgette – were immense, creating an underground sewer system (much of it still in use), improving transport routes and wiping out some of the city’s more notorious slums. However, vested interests and resistance to reform from the City hampered the efforts of the MBW, which was also found to be involved in widespread malpractice.

In 1888 the London County Council (LCC) was established. It was the first directly elected London-wide government, though as ever the City held on jealously to its independence (and in 1899, the municipal boroughs were set up deliberately to undermine the power of the LCC). The arrival of the LCC coincided with an increase in working-class militancy within the capital. In 1884, 120,000 gathered in Hyde Park to support the ultimately unsuccessful London Government Bill, while a demonstration held in 1886 in Trafalgar Square in protest against unemployment ended in a riot through St James’s. The following year the government banned any further demos, and the resultant protest brought even larger numbers to Trafalgar Square. The brutality of the police in breaking up this last demonstration led to its becoming known as “Bloody Sunday”.

In 1888 the Bryant & May matchgirls won their landmark strike action over working conditions, a victory followed up the next year by further successful strikes by the gasworkers and dockers. Charles Booth published his seventeen-volume Life and Labour of the People of London in 1890, providing the first clear picture of the social fabric of the city and shaming the council into action. In the face of powerful vested interests – landlords, factory owners and private utility companies – the LCC’s Liberal leadership attempted to tackle the enormous problems, partly by taking gas, water, electricity and transport into municipal ownership, a process that took several more decades to achieve. The LCC’s ambitious housing programme was beset with problems, too. Slum clearances only exacerbated overcrowding, and the new dwellings were too expensive for those in greatest need. Rehousing the poor in the suburbs also proved unpopular, since there was a policy of excluding pubs, traditionally the social centre of working-class communities, from these developments.

While half of London struggled to make ends meet, the other half enjoyed the fruits of the richest nation in the world. Luxury establishments such as The Ritz and Harrods belong to this period, which was personified by the dissolute and complacent Prince of Wales, later Edward VII (1901–10). For the masses, too, there were new entertainments to be enjoyed: music halls boomed, public houses prospered and the circulation of populist newspapers such as the Daily Mirror topped one million. The first “Test” cricket match between England and Australia took place in 1880 at the Kennington Oval in front of twenty thousand spectators, and during the following 25 years nearly all of London’s professional football clubs were founded.

From World War I to World War II

Public patriotism peaked at the outbreak of World War I (1914–18), with crowds cheering the troops off from Victoria and Waterloo stations, convinced the fighting would all be over by Christmas. In the course of the next four years London experienced its first aerial attacks, with Zeppelin raids leaving some 650 dead, but these were minor casualties in the context of a war that destroyed millions of lives and eradicated whatever remained of the majority’s respect for the ruling classes.

At the war’s end in 1918, the country’s social fabric was changed drastically as the voting franchise was extended to all men aged 21 and over and to women of 30 or over. Equal voting rights for women – hard fought for by the radical Suffragette movement led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters before the war – were only achieved in 1928, the year of Emmeline’s death.

Between the wars, London’s population increased dramatically, reaching close to nine million by 1939, and representing one-fifth of the country’s population. In contrast to the nineteenth century, however, there was a marked shift in population out into the suburbs. Some took advantage of the new “model dwellings” of LCC estates in places such as Dagenham in the east, though far more settled in “Metroland”, the sprawling new suburban districts that followed the extension of the Underground out into northwest London.

In 1924 the British Empire Exhibition was held, with the intention of emulating the success of the Great Exhibition. Some 27 million people visited the show, but its success couldn’t hide the tensions that had been simmering since the end of the war. In 1926, a wage dispute between the miners’ unions and their bosses developed into the General Strike. For nine days, more than half a million workers stayed away from work, until the government called in the army and thousands of volunteers to break the strike.

The economic situation deteriorated even further after the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929, with unemployment in Britain reaching over three million in 1931. The Jarrow Marchers, the most famous protesters of the Depression years, shocked London on their arrival in 1936. In the same year thousands of British fascists tried to march through the predominantly Jewish East End, only to be stopped in the so-called Battle of Cable Street. The end of the year brought a crisis within the Royal Family, too, when Edward VIII abdicated following his decision to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American. His brother, George VI (1936–52), took over.

There were few public displays of patriotism with the outbreak of World War II (1939–45), and even fewer preparations were made against the likelihood of aerial bombardment. The most significant step was the evacuation of six hundred thousand of London’s most vulnerable citizens (mostly children), but around half that number had drifted back to the capital by the Christmas of 1939, the midpoint of the “phoney war”. The Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign, known as the Blitz, lasted from September 1940 to May 1941. Further carnage was caused towards the end of the war by the pilotless V-1 “doodlebugs” and V-2 rockets, which caused another twenty thousand casualties.

THE BLITZ

The Luftwaffe bombing of London in World War II – commonly known as the Blitz – began on September 7, 1940, when in one night alone some 430 Londoners lost their lives, and over 1600 were seriously injured. It continued for 57 consecutive nights, then intermittently until the final and most devastating attack on the night of May 10, 1941, when 550 planes dropped over one hundred thousand incendiaries and hundreds of explosive bombs in a matter of hours. The death toll that night was over 1400, bringing the total killed during the Blitz to between twenty thousand and thirty thousand, with some 230,000 homes wrecked. Along with the East End, the City was particularly badly hit: in a single raid on December 29 (dubbed the “Second Fire of London”), 1400 fires broke out across the Square Mile. Some say the Luftwaffe left St Paul’s standing as a navigation aid, but it came close to destruction when a bomb landed near the southwest tower; luckily the bomb didn’t go off, and it was successfully removed to the Hackney marshes where the 100ft-wide crater left by its detonation is still visible.

The authorities were ready to build mass graves for potential victims, but were unable to provide adequate air-raid shelters to prevent widespread carnage. The corrugated steel Anderson shelters issued by the government were of use to only one in four London households – those with gardens in which to bury them. Around 180,000 made use of the tube, despite initial government reluctance, by simply buying a ticket and staying below ground. The cheery photos of singing and dancing in the Underground which the censors allowed to be published tell nothing of the stale air, rats and lice that folk had to contend with. And even the tube stations couldn’t withstand a direct hit, as occurred at Bank in January 1941, when over a hundred died. The vast majority of Londoners – some sixty percent – simply hid under the sheets and prayed.

Postwar London

The end of the war in 1945 was followed by a general election, which brought a landslide victory for the Labour Party under Clement Attlee. The Attlee government created the welfare state, and initiated a radical programme of nationalization, which brought the gas, electricity, coal, steel and iron industries under state control, along with the inland transport services. London itself was left with a severe accommodation crisis, with some eighty percent of the housing stock damaged to some degree. In response, prefabricated houses were erected all over the city, some of which were to remain occupied for well over forty years. The LCC also began building huge housing estates on many of the city’s numerous bombsites, an often misconceived strategy which ran in tandem with the equally disastrous New Towns policy of central government.

To lift the country out of its gloom, the Festival of Britain was staged in 1951 on derelict land on the south bank of the Thames, a site that was eventually transformed into the Southbank Arts Centre. Londoners turned up at this technological funfair in their thousands, but at the same time many were abandoning the city for good, starting a slow process of population decline that has continued ever since. The consequent labour shortage was made good by mass immigration from the former colonies, in particular the Indian subcontinent and the West Indies. The first large group to arrive was the 492 West Indians aboard the SS Empire Windrush, which docked at Tilbury in June 1948. The newcomers, a large percentage of whom settled in London, were given small welcome, and within ten years were subjected to race riots, which broke out in Notting Hill in 1958.

The riots are thought to have been carried out, for the most part, by “Teddy Boys”, working-class lads from London’s slum areas and new housing estates, who formed the city’s first postwar youth cult. Subsequent cults, and their accompanying music, helped turn London into the epicentre of the so-called Swinging Sixties, the Teddy Boys being usurped in the early 1960s by the “Mods”, whose sharp suits came from London’s Carnaby Street. Fashion hit the capital in a big way, and, thanks to the likes of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Twiggy, London was proclaimed hippest city on the planet on the front pages of Time magazine.

Life for most Londoners, however, was rather less groovy. In the middle of the decade London’s local government was reorganized, the LCC being supplanted by the Greater London Council (GLC), whose jurisdiction covered a much wider area, including many Tory-dominated suburbs. As a result, the Conservatives gained power in the capital for the first time since 1934, and one of their first acts was to support a huge urban motorway scheme that would have displaced as many people as did the railway boom of the Victorian period. Luckily for London, Labour won control of the GLC in 1973 and halted the plans. The Labour victory also ensured that the Covent Garden Market building was saved for posterity, but this ran against the grain. Elsewhere, whole areas of the city were pulled down and redeveloped, and many of London’s worst tower blocks were built.

Thatcherite London

In 1979 Margaret Thatcher won the general election for the Conservatives, and the country and the capital would never be quite the same again. Thatcher went on to win three general elections, steering Britain into a period of ever greater social polarization. While taxation policies and easy credit fuelled a consumer boom for the professional classes (the yuppies of the 1980s), the erosion of the manufacturing industry and weakening of the welfare state created a calamitous number of people trapped in long-term unemployment, which topped three million in the early 1980s. The Brixton riots of 1981 and 1985 and the Tottenham riot of 1985 were reminders of the price of such divisive policies, and of the long-standing resentment and feeling of social exclusion rife among the city’s black youth.

Nationally, the Labour Party went into sharp decline, but in London the party won a narrow victory in the GLC elections on a radical manifesto that was implemented by its youthful new leader Ken Livingstone, or “Red Ken” as the tabloids dubbed him. Under Livingstone, the GLC poured money into projects among London’s ethnic minorities, into the arts and, most famously, into a subsidized fares policy which saw thousands abandon their cars in favour of inexpensive public transport. Such schemes endeared Livingstone to the hearts of many Londoners, but his popular brand of socialism was too much for the Thatcher government, who, in 1986, abolished the GLC, leaving London as the only European capital without a directly elected body to represent it.

Abolition exacerbated tensions between the poorer and richer boroughs of the city. Rich Tory councils like Westminster proceeded to slash public services and sell off council houses to boost Tory support in marginal wards. Meanwhile in impoverished Labour-held Lambeth and Hackney, millions were being squandered by corrupt council employees. Homelessness returned to London in a big way for the first time since Victorian times, and the underside of Waterloo Bridge was transformed into a “Cardboard City”, sheltering up to two thousand vagrants on any one night. Great efforts were made by nongovernmental organizations to alleviate homelessness, not least the establishment of a weekly magazine, the Big Issue, which continues to be sold by the homeless right across London, earning them a small wage.

Thatcher’s greatest folly, however, was the introduction of the Poll Tax, a head tax levied regardless of means, which hit the poorest sections of the community hardest. The tax also highlighted the disparity between the city’s boroughs. In wealthy, Tory-controlled Wandsworth, Poll Tax bills were zero, while those in poorer, neighbouring, Labour-run Lambeth were the highest in the country. In 1990, the Poll Tax provoked the first full-blooded riot in central London for a long time, and played a significant role in Thatcher’s downfall later that year.

THE BIG BANG

In 1986, at the same time as homelessness and unemployment were on the increase, the so-called “Big Bang”, which abolished a whole range of restrictive practices on the Stock Exchange, took place. The immediate effect of this deregulation was that foreign banks began to take over brokers and form new, competitive conglomerates. The side effect, however, was to send stocks and shares into the stratosphere, shortly after which they inevitably crashed, ushering in a recession that dragged on for the best part of the next ten years. The one great physical legacy of the Thatcherite experiment in the capital is the Docklands development, a new business quarter in the derelict docks of the East End, which came about as a direct result of the Big Bang.

Twenty-first-century London

On the surface at least, twenty-first-century London has come a long way since the bleak Thatcher years. Funded by money from the National Lottery and the Millennium Commission, the face of the city has certainly changed for the better: the city’s national museums have been transformed into state-of-the-art visitor attractions, and all of them are free; there are new pedestrian bridges over the Thames; and Tate Modern towers like a beacon of optimism over the South Bank.

The creation of the Greater London Assembly (GLA), along with an American-style Mayor of London, both elected by popular mandate, ended fourteen years without a city council. The Labour government, which came to power on a wave of enthusiasm in 1997, did everything it could to prevent the election of the former GLC leader Ken Livingstone as the first mayor, but, despite being forced to leave the Labour Party and run as an independent, he won a resounding victory in the 2000 mayoral elections.

Livingstone was succeeded by Boris Johnson in 2008, but his lasting legacy has been in transport. As well as creating more bus routes and introducing more buses, he successfully introduced a congestion charge for every vehicle entering central London. As a result, traffic levels in central London have been reduced, and, although the congestion charge hasn’t solved all the city’s problems, at least it showed that, with a little vision and perseverance, something concrete can be achieved.

Livingstone was also instrumental in winning the 2012 Olympics for London, by emphasizing the Games’ regenerative potential for a deprived area of London’s East End. For a moment, London celebrated wildly – the euphoria was all too brief. A day after hearing the news about the Olympics, on July 7, 2005, London was hit by four suicide bombers who killed themselves and over fifty innocent commuters in four separate explosions: on tube trains at Aldgate, Edgware Road and King’s Cross and one on a bus in Tavistock Square. Two weeks later a similar attack was unsuccessful after the bombers’ detonators failed. Despite everyone’s worst fears, however, these two attacks proved to be isolated incidents and not the beginning of a concerted campaign.

The 2010 election produced no overall winner and resulted in a hung parliament for only the second time since World War II. The Conservatives formed a coalition with the Liberal Democrats and began the harshest series of spending cuts since 1945. In August 2011, against a background of deepening economic hardship, London suffered the worst riots since the 1980s, not just in areas such as Tottenham (where the riots began) and Brixton, but across the capital, from Bromley to Waltham Forest.

2012 proved a great year for London, with the celebrations of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee (sixty years on the throne), and a very successful and distinctive Olympic Games, further boosting London’s international status and the mood of the city. The capital’s economy, too, remains buoyant, despite the government’s austerity measures, but the biggest problem is housing. While wealthy foreigners are happy to invest in buildings like the Shard, and luxury flat developments, affordable housing is thin on the ground, and some imaginative thinking is going to be necessary if a full-blown accommodation crisis is to be avoided.

LONDON IN FILM THROUGH THE DECADES

As early as 1889 Wordsworth Donisthorpe made a primitive motion picture of Trafalgar Square, and since then London has been featured in countless films. Here is a snapshot selection of films culled from each decade since the 1920s.

Blackmail (Alfred Hitchcock, 1929). The first British talkie feature film, this thriller stars the Czech actress Anny Ondra and has its dramatic finale on the dome of the British Museum.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Alfred Werker, 1939). The Baker Street detective has made countless screen appearances, but Basil Rathbone remains the most convincing incarnation. Here Holmes and Watson (Nigel Bruce) are pitted against Moriarty (George Zucco), out to steal the Crown Jewels.

Passport to Pimlico (Henry Cornelius, 1948). The quintessential Ealing Comedy, in which the inhabitants of Pimlico, discovering that they are actually part of Burgundy, abolish rationing and closing time. Full of all the usual eccentrics, among them Margaret Rutherford in particularly fine form as an excitable history don.

The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955). Delightfully black comedy set somewhere at the back of King’s Cross (a favourite location for filmmakers). Katie Johnson plays the nice old lady getting the better of Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers and assorted other crooks.

Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966). Swinging London and some less obvious backgrounds (notably Maryon Wilson Park, Charlton) feature in this metaphysical mystery about a photographer (David Hemmings) who may unwittingly have recorded evidence of a murder.

Jubilee (Derek Jarman, 1978). Jarman’s angry punk collage, in which Elizabeth I finds herself transported to the urban decay of late twentieth-century Deptford.

My Beautiful Laundrette (Stephen Frears, 1985). A surreal comedy of Thatcher’s London, offering the unlikely combination of an entrepreneurial Asian (Gordon Warnecke), his ex-National Front boyfriend (Daniel Day-Lewis) and a laundrette called Powders.

Naked (Mike Leigh, 1993). David Thewlis is brilliant as the disaffected and garrulous misogynist who goes on a tour through the underside of what he calls “the big shitty” – life is anything but sweet in Leigh’s darkest but most substantial film.

Dirty Pretty Things (Stephen Frears, 2002). Entertaining romantic thriller set in London’s asylum-seeking, multicultural underbelly, shot through with plenty of humour and lots of pace.

The King’s Speech (Tom Hooper, 2011). Moving, funny account of King George VI’s battle to overcome his stammer, after finding himself catapulted onto the throne following the abdication of Edward VIII.

BOOKS

Given the enormous number of books on London, the list here is necessarily a selective one,

with books marked  being particularly recommended. London still has many

excellent independent bookshops. Most of

the books recommended are in paperback, but the more expensive books can often be

bought secondhand online.

being particularly recommended. London still has many

excellent independent bookshops. Most of

the books recommended are in paperback, but the more expensive books can often be

bought secondhand online.

TRAVEL, JOURNALS AND MEMOIRS

John Betjeman

Betjeman’s London. A selection of writings and poems by the then Poet Laureate, who spearheaded the campaign to save London’s architectural heritage in the 1960s.

James Boswell

James Boswell

London Journal. Boswell’s diary, written in 1792–93 when he was lodging in Downing Street, is remarkably candid about his frequent dealings with the city’s prostitutes, and is a fascinating insight into eighteenth-century life.

John Evelyn

The Diary of John Evelyn. In contrast to his contemporary, Pepys, Evelyn gives away very little of his personal life, but his diaries are full of inside stories of court life from Queen Anne to James II.

Ford Madox Ford

The Soul of London. Experimental, impressionist portrait of London published in 1905.

Doris Lessing

Walking in the Shade 1949–62. The second volume of Lessing’s autobiography, set in London in the 1950s, deals with the literary and theatre scenes and party politics, including her association with the Communist Party, with which she eventually became disenchanted.

George Orwell

Down and Out in Paris and London. Orwell’s tramp’s-eye view of the 1930s, written from first-hand experience. The London section is particularly harrowing.

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys

The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Pepys kept a voluminous diary while he was living in London from 1660 until 1669, recording the fall of the Commonwealth, the Restoration, the Great Plague and the Great Fire, as well as describing the daily life of the nation’s capital. Penguin’s The Diary of Samuel Pepys, although abridged from eleven volumes, is still massive; but contains a selection of all the best bits.

Christopher Ross

Tunnel Visions. Witty and perceptive musings of popular philosopher Ross as he spends a year working as a station assistant on the tube at Oxford Circus.

Iain Sinclair

Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire: a Confidential Report; Liquid City; and London Orbital. Sinclair is one of the most original (and virtually unreadable) London writers of his generation. Hackney is an absorbing biography of the author’s favourite borough. Liquid City contains beautiful photos and entertaining text about London’s hidden rivers and canals; and London Orbital is an account of his walk round the M25, delving into obscure parts of the city’s periphery.

HISTORY, SOCIETY AND POLITICS

Peter Ackroyd

Dickens; Blake; Sir Thomas More; Thames: Sacred River; London: The Biography and London Under. Few writers know quite as much about London as Ackroyd does, and London is central to all three of his biographical subjects – the result is scholarly, enthusiastic and eminently readable. London: The Biography is the massive culmination of a lifetime’s love affair with a living city and its intimate history.

Paul Begg

Paul Begg

Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History. This book, whose author has given talks to the FBI on the subject, sets the murders in their Victorian context and aims to debunk the myths.

Piers Dudgeon

Our East End: Memoirs of Life in Disappearing Britain. Packed with extracts from written accounts and diaries as well as literary sources, this is a patchwork of the East End with its legendary community spirit and a dash of realism.

Clive Emsley

The Newgate Calendar. Grim and gory account of the most famous London criminals of the day – Captain Kidd, Jack Sheppard, Dick Turpin – with potted biographies of each victim, ending with an account of his execution. Starting out as a collection of papers and booklets, The Newgate Calendar was first published in 1828 and was second in popularity only to the Bible at the time of publication, but is now difficult to get hold of.

Juliet Gardiner

The Blitz: the British Under Attack. A far-reaching account of the Blitz which dispels some of the myths, combining first-hand accounts with some surprising statistics.

Jonathan Glancey

Jonathan Glancey

London Bread and Circuses. In this small, illustrated book, the Guardian’s architecture critic extols the virtues of the old LCC and visionaries like Frank Pick, who transformed London’s transport in the 1930s, discusses the millennium projects (the “circuses” of the title) and bemoans the city’s creaking infrastructure.

Ed Glinert

Ed Glinert

The London Compendium. Glinert dissects every street, every park, every house and every tube station and produces juicy anecdotes every time. The same author’s East End Chronicles: 300 Years of Mystery and Mayhem is a readable revelation of all the nefarious doings of the East End, sorting myth from fact, and hoping the spirit will somehow survive in spite of Docklands.

Rahila Gupta

From Homebreakers to Jailbreakers: Southall Black Sisters. The story of a radical Asian women’s group which, against all the odds, was founded in London in 1979 and became internationally famous for campaigning for all disempowered black women.

Sarah Hartley

Mrs P’s Journey: The Remarkable Story of the Woman Who Created the A–Z Map. The tale of Phyllis Pearsall, the indomitable woman who survived a horrific childhood and went on to found London’s most famous mapmaking company – you won’t feel the same about the A–Z again.

Rachel Lichtenstein and Iain Sinclair

Rodinsky’s Room. A fascinating search into the Jewish past of the East End, centred on the nebulous figure of David Rodinsky.

Peter Linebaugh

The London Hanged. Superb, Marxist analysis of crime and punishment in the eighteenth century, drawing on the history of those hanged at Tyburn.

Jack London

The People of the Abyss. The author went undercover in 1902 to uncover the grim reality of East End poverty.

Henry Mayhew

London Labour and the London Poor. Mayhew’s pioneering study of Victorian London, based on research carried out in the 1840s and 1850s.

Roy Porter

London: A Social History. This immensely readable history is one of the best books on London published since the war, particularly strong on the saga of the capital’s local government.

Stephen Porter

The Great Plague of London. Drawing on various contemporary sources, Porter paints a vivid picture of what it was like to live with a horror which killed seventy thousand Londoners.

Maude Pember Reeves & Polly Toynbee

Round About a Pound a Week. From 1909 to 1913, the Fabian Women’s Group, part of the British Labour Party, recorded the daily budget of thirty families in Lambeth living in extreme poverty. This is the accompanying comment, which is both enlightening and enlightened.

John Stow

A Survey of London. Stow, a retired tailor, set himself the unenviable task of writing the first-ever account of the city in 1598, for which he is now rightly revered, though at the time the task forced him into penury.

Judith R. Walkowitz

City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London. Weighty feminist tract on issues such as child prostitution and the Ripper murders, giving a powerful overview of the image of women in the fiction and media of the day.

Ben Weinreb & Christopher Hibbert

Ben Weinreb & Christopher Hibbert

The London Encyclopaedia. More than a thousand pages of concisely presented information on London past and present, accompanied by the odd illustration. The most fascinating book on the capital.

Jerry White

London in the Eighteenth Century; London in the Nineteenth Century; London in the Twentieth Century. Comprehensive history of the most momentous centuries in the city’s history.

Sarah Wise

The Blackest Streets: The Life and Death of a Victorian Slum. A meticulously researched work which reveals the depths of poverty in the area north of Bethnal Green Road.

ART, ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHEOLOGY

T.M.M. Baker

London: Rebuilding the City after the Great Fire. In 1666 the heart of the City of London was destroyed; this book covers not only Wren churches but other less well-known public and private buildings and is beautifully illustrated.

Felix Barker & Peter Jackson

The History of London in Maps. A beautiful volume of maps, from the earliest surviving chart of 1558 to the new Docklands, with accompanying text explaining the history of the city and its cartography.

Bill Brandt

London in the Thirties. Brandt’s superb black-and-white photos bear witness to a London lost in the Blitz.

Reuel Golden

London: Portrait of a City. A treasure trove of photographs sourced from archives worldwide as well as from such famous names as Bailey, Beaton and Cartier Bresson, this book captures London from Victorian times through the Swinging Sixties, from the Festival of Britain to the 2012 Olympics.

Elaine Harwood & Andrew Saint

London. Part of the excellent Exploring England’s Heritage series, sponsored by English Heritage. It’s highly selective, though each building is discussed at some length and is well illustrated.

Leo Hollis

The Stones of London. An illuminating social history of London illustrated by studying twelve of the city’s buildings ranging from the iconic (Westminster Abbey) to the obscure (a tower block in the East End).

Derek Kendall

The City of London Churches. A beautifully illustrated book, comprised mostly of colour photos, covering the remarkable City churches, many of them designed by Wren after the Great Fire.

Andrew Richard Kershman

London’s Monuments. A stroll around some of the well-known and the more obscure monuments of the city.

Nikolaus Pevsner and others

The Buildings of England. Magisterial series, started by Pevsner, to which others have added, inserting newer buildings but generally respecting the founder’s personal tone. London comes in six volumes, plus a special volume on the City churches.

Arnold Schwartzman

London Art Deco: A Celebration of the Architectural Style of the Metropolis During the Twenties and Thirties. Generously illustrated, this book bears witness to the British version of Art Deco in the likes of the Savoy and the Hoover building.

Anthony Sutcliffe

Architectural History of London. A weighty tome, extensively illustrated, which traces the history of building in London from the Romans to the twenty-first century.

Richard Trench & Ellis Hillman

London under London. Fascinating book revealing the secrets of every aspect of the capital’s subterranean history, from the lost rivers of the underground to the gas and water systems.

David Whitehead & Henning Klattenhof

London – the Architectural Guide. A chronological study from the Romans to the present day with excellent colour photographs and information about architects and styles as well as buildings.

LONDON IN FICTION

Peter Ackroyd

English Music; Hawksmoor; The House of Doctor Dee; The Great Fire of London; and Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem. Ackroyd’s novels are all based on arcane aspects of London, wrapped into thriller-like narratives, and conjuring up kaleidoscopic visions of various ages of English culture. Hawskmoor, about the great church architect, is the most popular and enjoyable.

Monica Ali

Monica Ali

Brick Lane. Acute, involving, and slyly humorous, novel about a young Bengali woman who comes over with her husband to live in London’s East End.

Martin Amis

London Fields; Yellow Dog. Short sentences and cartoon characters, Amis’s novels tend to provoke extreme reactions in readers. Love ’em or hate ’em, these two are set in London.

J.G. Ballard

The Drowned World; Concrete Island; The Millennium People; High Rise. Wild stuff. The Drowned World, Ballard’s first novel, is set in a futuristic, flooded and tropical London. In Concrete Island, a car crashes on the Westway, leaving its driver stranded on the central reservation, unable to flag down passing cars. In The Millennium People the middle classes turn urban terrorist. In High Rise, the residents of a high-rise block of flats in East London go slowly mad.

Samuel Beckett

Murphy. Nihilistic, dark-humoured vision of the city, written in 1938, and told through the eyes of anti-hero Murphy.

Elizabeth Bowen

The Heat of the Day. Bowen worked for the Ministry of Information during World War II, and witnessed the Blitz first-hand from her Marylebone flat; this novel perfectly captures the dislocation and rootlessness of wartime London.

Anthony Burgess

A Dead Man in Deptford. Playwright Christopher Marlowe’s unexplained murder in a tavern in Deptford provides the background for this historical novel, which brims over with Elizabethan life and language.

Angela Carter

The Magic Toyshop; Wise Children. The Magic Toyshop was Carter’s celebrated 1967 novel, about a provincial woman moving to London, while Wise Children, published a year before her untimely death, is set in a carnivalesque London.

G.K. Chesterton

The Napoleon of Notting Hill. Written in 1904, but set eighty years in the future, in a London divided into squabbling independent boroughs – something prophetic there – and ruled by royalty selected on a rotational basis.

J.M. Coetzee

Youth. Claustrophobic, semi-autobiographical novel by South African Booker Prize-winner, centred on a self-obsessed colonial, struggling to find the meaning of life and become a writer in London in the 1960s.

Arthur Conan Doyle

Arthur Conan Doyle

The Complete Sherlock Holmes. Deerstalkered sleuth Sherlock Holmes and dependable sidekick Dr Watson penetrate all levels of Victorian London, from Limehouse opium dens to millionaires’ pads. A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four are based entirely in London.

Joseph Conrad

The Secret Agent. Conrad’s wonderful spy story is based on the botched anarchist bombing of Greenwich Observatory in 1894, and exposes the hypocrisies of both the police and the anarchists.

Daniel Defoe

Journal of the Plague Year. An account of the Great Plague seen through the eyes of an East End saddler, written some sixty years after the event.

Charles Dickens

Bleak House; A Christmas Tale; Little Dorrit; Oliver Twist. The descriptions in Dickens’ London-based novels have become the clichés of the Victorian city: the fog, the slums and the stinking river. LittleDorrit is set mostly in Borough and contains some of his most trenchant pieces of social analysis. Much of Bleak House is set around the Inns of Court that Dickens knew so well.

Maureen Duffy

Capital. First published in 1975, the novel is like a many-layered sandwich full of startling flavours, as the focus shifts from the central character, an unbalanced squatter with an obsession with London’s past and future, to vivid slices of history.

Nell Dunn

Up the Junction; Poor Cow. Perceptive and unsentimental account of the downside of south London life in the 1950s after the hype of the Festival of Britain.

George Gissing

New Grub Street; The Nether World. New Grub Street is a classic 1891 story of intrigue and jealousy among London’s Fleet Sthacks. The Nether World is set among the poor workers of Clerkenwell.

Graham Greene

The Human Factor; It’s a Battlefield; The Ministry of Fear; The End of the Affair. Greene’s London novels are all fairly bleak, ranging from The Human Factor, which probes the underworld of the city’s spies, to The Ministry of Fear, which is set during the Blitz.

Patrick Hamilton

Hangover Square; Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky. The first is a story of unrequited love and violence in Earl’s Court in the 1940s, while the latter is a trilogy of stories set in seedy 1930s London.

Neil Hanson

The Dreadful Judgement. A docu-fiction account in which modern scientific methods and historical knowledge are applied to the Fire of London so vividly you can almost feel the heat.

Aldous Huxley

Point Counter Point. Sharp satire of London’s high-society wastrels and dilettantes of the Roaring Twenties.

Henry James

The Awkward Age. Light, ironic portrayal of London high society at the turn of the twentieth century.

Hanif Kureishi

The Buddha of Suburbia; Love in a Blue Time; My Ear at His Heart. The Buddha of Suburbia is a raunchy account of life as an Anglo-Asian in late-1960s suburbia, and the art scene of the 1970s; Love in a Blue Time is a collection of short stories set in 1990s London; My Ear at His Heart is a biography of Kureishi’s father from his privileged childhood in Mumbai to a life in Bromley.

Andrea Levy

Small Island. A warm-hearted novel in which postwar London struggles to adapt to the influx of Jamaicans who in turn find that the land of their dreams is full of prejudice.

Colin MacInnes

Absolute Beginners; Omnibus. Absolute Beginners, a story of life in Soho and Notting Hill in the 1950s – much influenced by Selvon – is infinitely better than the film of the same name. Omnibus is set in 1957, in a Victoria Station packed with hopeful black immigrants; white welfare officer meets black man from Lagos with surprising results.

Somerset Maugham

Liza of Lambeth. Maugham considered himself a “second-rater”, but this early novel, written in 1897, about Cockney lowlife, is packed with vivid local colour.

Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan

Saturday. Set on the day of a protest march against the war in Iraq, this book captures the mood of London post-9/11, as the main character is forced to consider his attitude to this and many other issues.

Timothy Mo

Sour Sweet. Very funny and very sad story of a newly arrived Chinese family struggling to understand the English way of life in the 1970s, written with great insight by Mo, who is himself of mixed parentage.

Michael Moorcock

Mother London. A magnificent, rambling, kaleidoscopic portrait of London from the Blitz to Thatcher by a once-fashionable, but now very much underrated, writer.

Iris Murdoch

Under the Net; The Black Prince; An Accidental Man; Bruno’s Dream. Under the Net was Murdoch’s first, funniest and arguably her best novel, published in 1954, starring a hack writer living in London. Many of her subsequent works are set in various parts of middle-class London and span several decades of the second half of the twentieth century.

George Orwell

Keep the Aspidistra Flying. Orwell’s 1930s critique of Mammon is equally critical of its chief protagonist, whose attempt to rebel against the system only condemns him to poverty, working in a London bookshop and freezing his evenings away in a miserable rented room.

Jonathan Raban

Soft City. An early work from 1974 that’s both a portrait of, and paean to, metropolitan life.

Derek Raymond

Derek Raymond

Not till the Red Fog Rises. A book which “reeks with the pervasive stench of excrement” as Iain Sinclair put it, this is a lowlife spectacular set in the seediest sections of the capital.

Barnaby Rogerson

(ed) London: Poetry of Place. A delightful pocket-sized book complete with potted biographies of the poets.

Edward Rutherford

London. A big, big novel (perhaps too big) that stretches from Roman times to the present and deals with the most dramatic moments of London’s history. Masses of historical detail woven in with the story of several families.

Samuel Selvon

The Lonely Londoners. “Gives us the smell and feel of this rather horrifying life. Not for the squeamish”, ran the quote from the Evening Standard on the original cover. This is, in fact, a wry and witty account of the African-Caribbean experience in London in the 1950s.

Iain Sinclair

Iain Sinclair

White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings; Downriver; Radon Daughters. Sinclair’s idiosyncratic and richly textured novels are a strange mix of Hogarthian caricature, New Age mysticism and conspiracy-theory rant. Deeply offensive and highly recommended.

Stevie Smith

Novel on Yellow Paper. Poet Stevie Smith’s first novel takes place in the publishing world of the London of 1930s.

Zadie Smith

White Teeth; NW. White Teeth is her highly acclaimed and funny first novel about race, gender and class in the ethnic melting pot of north London. NW follows the fortunes of four Londoners from a council estate through the labyrinth of urban life in northwest London.

John Sommerfield

May Day. Set in the revolutionary fervour of the 1930s, this novel is “as if Mrs Dalloway was written by a Communist Party bus driver”, in the words of one reviewer.

Muriel Spark

The Bachelors; The Ballad of Peckham Rye. Two London-based novels written one after the other by the Scots-born author, best known for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

Edith Templeton

Gordon. A tale of sex and humiliation in postwar London, banned in the 1960s when it was published under a pseudonym (Louisa Walbrook).

Rose Tremain

The Road Home. The moving story of Lev, an Eastern European economic migrant, who heads for London and finds the streets are not paved with gold in the late twentieth century.

Sarah Waters

Affinity; Fingersmith; Tipping the Velvet; and The Night Watch. Racy modern novels set in Victorian London: Affinity is set in the spiritualist milieu, Fingersmith focuses on an orphan girl, while Tipping the Velvet is about lesbian love in the music hall. The Night Watch is a tale of London during World War II.

Evelyn Waugh

Vile Bodies. Waugh’s target, the “vile bodies” of the title, are the flippant rich kids of the Roaring Twenties, as in Huxley’s Point Counter Point.

Patrick White

The Living and the Dead. Australian Nobel Prize-winner’s second novel is a sombre portrait of family life in London at the time of the Spanish Civil War.

P.G. Wodehouse

Jeeves Omnibus. Bertie Wooster and his stalwart butler, Jeeves, were based in Mayfair, and many of their exploits take place with London showgirls and in the Drones gentlemen’s club.

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf