QI FENG LIN AND JAMES W. FYLES

1. INTRODUCTION

Our goal in this chapter is to propose and explore two related changes in our current thinking on the relationship between humans and the environment, which we feel are crucial to this effort. The first is the idea of humans as being part of the ecosystem as opposed to the common assumption that humans are separate from it. The second is a reinterpretation of the concept of ecosystem health in view of this humans-in-ecosystem perspective.

We begin by discussing the work of Aldo Leopold (1887–1948), the American forester, conservationist, and author of A Sand County Almanac (1949). This chapter examines how Leopold’s land ethic was based on his sound understanding of the land, as well as how he used the concept of land health to refer to the intrinsic characteristic state of land that humans should strive to preserve. We also discuss the concept of the ecosystem, which gained prominence in the academic community toward the end of Leopold’s life and has since become a common scientific term. We then consider Tim Ingold’s description of the physical environment as a “domain of entanglement,” which we feel is a compelling way to help people redefine themselves as being part of the environment. We discuss how this new self-image in turn forces us to rethink concepts such as ecosystem health, which has been used by the scientific community to refer to the holistic, well-functioning state of ecosystems. We note (in reference to other chapters of this book) that the word “health” may lack a definitive and precise definition, but this is compensated for by its connotative quality, which provides an interpretative space for users. Finally, we discuss an essay by Leopold entitled “A Mighty Fortress,” which conveys the multiplicity and richness of the health concept as applied to land, before concluding with a brief remark on the importance of metaphor in constructing an ethics for the Anthropocene.

2. ALDO LEOPOLD’S LAND ETHIC AND LAND HEALTH

The writings of Aldo Leopold were a milestone in the discourse on the relationship between humans and the environment (Leopold 2013). Leopold’s work is particularly relevant to our present discourse in ecological economics because he was grappling with an earlier version of the same issue as we are now: a profound deterioration of the environment as a result of economic thinking that had yet to be informed by ecological principles. After decades of promoting conservation within the existent economic system, Leopold eventually turned his mind toward challenging the underlying assumptions of society on the role of human beings in the environment and began to develop the correlative concepts of land ethic and land health.

2.1. Personal History

Leopold’s views concerning humans and land evolved gradually over his long career in conservation, first as a forester in the U.S. Forest Service and then as professor of game and later wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin. He studied at the Yale Forest School, which was established in 1900 with funding from Gifford Pinchot’s family, and he was influenced by Pinchot’s utilitarian views of the human–forest relationship. Upon graduating in 1909, Leopold moved to the southwest territories of Arizona and New Mexico to begin his career with the Forest Service. His early responsibilities included forest management, grazing and recreation policy, and a nascent game and fish program. During this period, he advocated policies such as the extermination of large predators and the draining of wetlands, which went against the ecological wisdom he would develop later (Leopold [1915] 1991, [1945] 1991; Meine 2010).

Leopold rose quickly through the ranks of the Forest Service. In 1924, he moved to the Forest Products Laboratory of the Forest Service in Madison, Wisconsin to serve as assistant and later associate director. He grew increasingly uncomfortable there, in part because his maturing ideas, which were always concerned with the broader subject of human–land relations, could not be reconciled with “the industrial motif of this otherwise admirable institution” (Leopold [1947] 1987). He left the Forest Service in 1928.1

In 1933, Leopold joined the University of Wisconsin at Madison as professor of game management in the Department of Agricultural Economics.2 In 1935, he purchased a worn-out farm, nicknamed “the shack,” near Baraboo, Wisconsin, which became his family’s weekend retreat. This gave him an opportunity to spend time in a rural landscape where he could observe the ecological drama of wild plants and animals, try his hand at land stewardship, and reflect upon the role of humans on the land.

Leopold encountered an array of conservation issues during his career. These issues, set against a background of rapid social and economic transformation beginning in the 1910s, through the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, and finally the catastrophic Second World War and subsequent demobilization of the 1940s, prompted Leopold to reflect upon the nature of the relationship between humans and the environment.

2.2. The Land Ethic

Although Leopold had been concerned with conservation during his employment at the Forest Service, it was during his professorship at Wisconsin that he devoted more attention and energy toward the challenge of promoting conservation of “the land,” a term he used in his writings to refer to the collective whole of soil, water, plants, animals, and people (Leopold [1944] 1991). This led him to elucidate and propose solutions to the various impacts of society on the land, which are generated and mediated through government policy and private economic production and consumption (Leopold [1933] 1991, [1934] 1991b). However, the impediments to conservation, as Leopold saw them, were overwhelming: the economic growth imperative; the resulting competitive pressure, leading to relentless resource utilization and urban development; the general lack of an aesthetic sense in society; a tension between private and public interests; the rapid industrialization of the economy; and the resulting drift in social consciousness away from the biophysical processes that sustain human communities and toward a fascination with gadgetry.

Eventually, Leopold concluded that conservation of the land would need to be based on an ethic. In an essay entitled “The Land Ethic,” published in his collection of essays A Sand County Almanac (1949), he articulated his land ethic.3 Leopold felt that insights from ecology bear important implications for ethics. The field of ecology, then relatively new, revealed a web of connections among the different components of land. These interconnections complicate matters because one can no longer devote ethical or economic attention to only a subset of species or resources chosen for their utility to humankind; ecology requires that land be treated as an integral whole. To respect this ecological reality, Leopold proposed that the sphere of ethical concern be expanded to include the land. This is accompanied by a transformation of consciousness of human beings from the dominant mentality of “conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it” (Leopold 1949:204).

In the view of most readers, the substance of Leopold’s land ethic is stated in the following4:

Quit thinking about decent land-use as solely an economic problem. Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and aesthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

(Leopold 1949:224–225)

Leopold’s dictum spoke most directly to land-use decision makers: foresters, farmers, government bureaucrats, and the like. It also spoke to the layperson whose consumption patterns and mentality toward the land affect land-use decisions in myriad and sometimes imperceptible ways. Indeed, during Leopold’s lifetime, the percentage of the U.S. population living in rural areas gradually decreased from more than 64 percent in the 1880s and 1890s to approximately 44 percent in the 1930s and 1940s; it has continued to decrease to approximately 19 percent in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau 2012:13–14). Leopold’s land ethic, appropriate to its time, now needs to be accompanied by a more explicit “consumption ethic” for it to gain traction in our present highly urbanized and high-consumption society (MacCleery 2000).5

Leopold’s use of the concepts of integrity and stability in the biotic community reflected his understanding of the land mechanism. For Leopold, the integrity of the land referred to its functional integrity, “a state of vigorous self-renewal” synonymous with health, which needs to be preserved (Leopold [1944] 1991). By stability, Leopold was not implying a static state of the land. Instead, he was referring to a dynamic equilibrium in the land mechanism, in contrast to the “self-accelerating rather than self-compensating departures from normal functioning” brought about by exploitative human land use, which he observed in the American landscape during the 1920s and 1930s (Leopold [1935] 1991; Meine 2004). His ideas were informed by his observations on how the stability of various ecosystem processes depends on the species diversity of that ecosystem. The more the ecosystem is able to keep its original species diversity and population levels, Leopold argued, the more stable the various processes of the ecosystem would be (Leopold [1944] 1991).6 It follows that human modification of the land should be “as gentle and as little as possible” (Leopold [1944] 1991:315).

Leopold’s criterion of beauty was based on his thinking that human interaction with the land ought to include both utility and beauty, and that recognizing and preserving the beauty in the landscape could serve to counterbalance the hard-headed and callous character of economic thinking. In an essay to encourage conservation on farmlands, Leopold wrote that “the landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself” (Leopold [1939] 1991b).7 According to Callicott (2008), Leopold’s aesthetic appreciation of nature, which could be described as his “land aesthetic,” is based not only on the physical appearance of natural objects and places, but also on the knowledge of their evolutionary history and ecological relationships. The end result is an extension of the “traditional criteria of natural beauty to the point where they essentially merged with his sense of long-term utility based on land health” (Meine 2004:112). Indeed, Newton (2006:347) suggested that in Leopold’s view beauty was an attribute of lands that possessed stability and integrity. Leopold felt that the appreciation of nature should be accessible to the layperson and that improving the public sensitivity of landscapes and the underlying biophysical processes was crucial to maintaining the health of the land (Meine 2004:112).

Finally, if humans are part of the land, then Leopold’s call for integrity, stability, and beauty in the land also applies to the human subcommunity of the land—to our lives, both individually and as a society.

The three principles articulated by Peter Brown in chapter 2—membership, householding, and entropic thrift—are similar to the concepts in Leopold’s land ethic. The first, membership, is a reference to Leopold’s idea of human beings as plain members and citizens of the biotic community. The second principle, householding, echoes Leopold’s proposal of substituting ecology—the study of the household, from Greek oikos and logos—for engineering as the guiding principle of civilization (Leopold [1938] 1991). Finally, the concept of entropic thrift reminds one of Leopold’s call for maintaining the complexity and diversity of food chains so as to preserve or restore the network of energy flow in the land (Leopold 1949:214–218), as articulated in his “biotic view of land.”

2.3. “Land Health” as Rationale for and Result of the Land Ethic

Leopold’s land ethic, which is essentially a reimagining of the role of human beings in the land, was grounded in his ecological understanding of how the land works. He drew upon the latest contemporary research in ecology to articulate his biotic view of land (Leopold [1939] 1991a). He understood land as having a highly complex and organized structure, being a network of soil, water, plants, and animals through which energy flows. It is “a slowly augmented revolving fund of life” open to energy from the sun and storing some of that energy away in soils, peats, and long-lived forests (Leopold [1939] 1991a). Leopold’s comprehension of the structure and processes of the natural environment remains ecologically sound for the most part from today’s perspective.8 Although the field of landscape ecology had not emerged at the time, Leopold’s view of a landscape in which various land types (e.g., woodlands, fields, and wetlands) are tied together by the movements of animals, water, and nutrients is fully consistent with current thinking in landscape ecology (Turner 2005).9 Leopold also used the words “community” and “organism” to describe the land, which facilitated his use of the concept of land health.

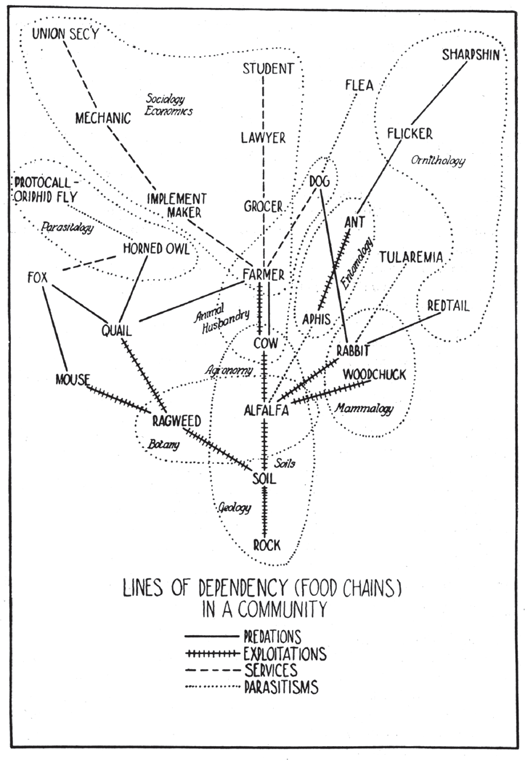

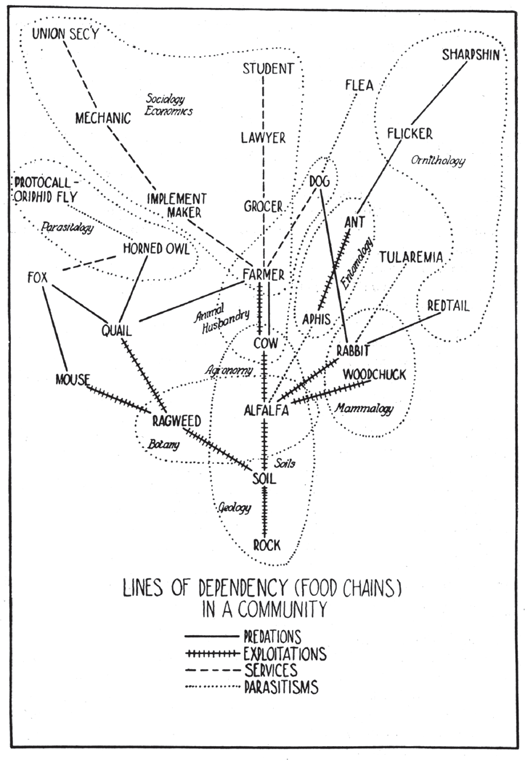

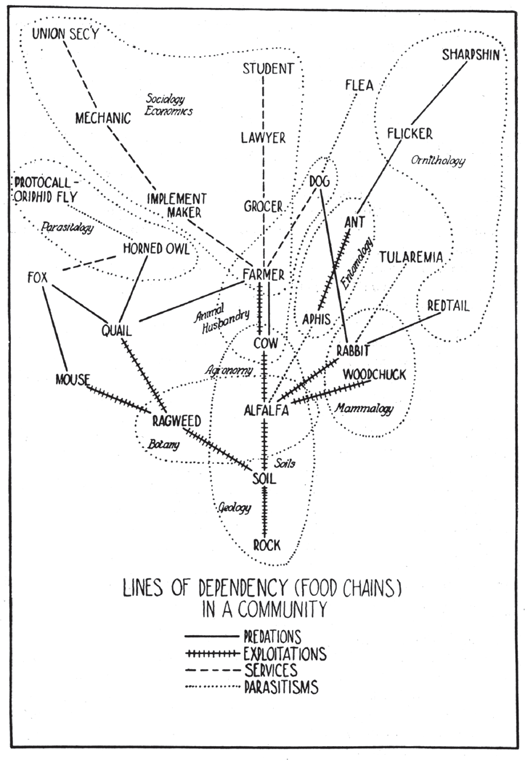

Two characteristics of Leopold’s ecological understanding of land, which informed his land ethic, are worth noting here. First, in Leopold’s thinking humans are not separated from the land, even when land is represented in a scientific form such as a land pyramid or a food web (see figure 7.1). He considered humans to be part of the pyramid, sharing “an intermediate layer with the bears, raccoons, and squirrels, which eat both meat and vegetables” (Leopold 1949:215). However, he understood that human modification of the land is of a different order compared to the other organisms: the use of scientific tools and technology was causing severe degradation of the land. Leopold concluded that “man-made changes are of a different order than evolutionary changes, and have effects more comprehensive than is intended or foreseen” (Leopold 1949:218).

Figure 7.1. The figure that accompanied Leopold’s “The Role of Wildlife in a Liberal Education” as it appeared in Transactions of the Seventh North American Wildlife Conference. It “traces some of the lines of dependency (or food chains, so called) in an ordinary community” (Leopold [1942] 1991). Source: The Aldo Leopold Foundation.

Second, Leopold recognized the limits of science in understanding how the land works: “The ordinary citizen today assumes that science knows what makes the [biotic] community clock tick; the scientist is equally sure that he does not. He knows that the biotic mechanism is so complex that its workings may never be fully understood” (Leopold 1949:205). The irreducible complexity and uncertainty in the workings of the land call for a certain measure of refrain and humility from humans when interacting with the land. Leopold thus imagined his land ethic as a guide for human behavior in complex ecological situations (Leopold 1949:203).

Leopold’s “land health,” which he had introduced in his published work but eventually explored in more depth in his unpublished manuscripts,10 plays an important role in his overall land ethic: “A land ethic … reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal” (Leopold 1949:221). Leopold was thus using land health, which is a normative concept, as a guide for human activity. Leopold used the term “unity” to describe this land-health attribute of the original native state of land, and called for “unified conservation” (instead of lopsided, single-track conservation that focuses only on a single resource) so that human activities are configured to promote and maintain land health instead of causing damage to it (Leopold [1944] 1991). The goal here is to discern and maintain the intrinsic characteristics of the land and to prevent or reverse the derangement of the land or “land-sickness,” which is caused by excessive or misguided human activity in industry and agriculture (Leopold [1941] 1991). Examples of symptoms of land-sickness that Leopold mentioned include loss of soil fertility, soil erosion, abnormal floods and shortages in water systems, and the sudden disappearance or irruption of plants and animal species (Leopold 1949:194, 221). Moreover, because Leopold viewed humans as part of land, his concept of land health encompassed the health of natural systems, humans included (Meine 2004:100).11 Interestingly enough, one of Leopold’s earliest uses of the phrase “land ethic” occurred in a pithy 1935 essay entitled “Land Pathology,” in which he discussed the problems of relying simply on the profit motive in conservation; the social, historical, and cultural reasons for the limited success of conservation so far; and the importance of ethics and aesthetics in tempering economic activity on the land (Leopold [1935] 1991).

Leopold’s ecological knowledge and land health concepts are therefore an integral component of his land ethic, providing a normative framework for understanding how the land works and helping him to establish a “mental image of land” in relation to which “we can be ethical” in the land ethic essay (Flader and Callicott 1991; Leopold 1949:214). He proposed two yardsticks of land health: soil fertility and diversity of fauna and flora (Leopold [c.1942] 1999). In a manuscript entitled “The Land-Health Concept and Conservation,” Leopold articulated four broad guidelines to achieve land health: (1) preserve native species; (2) avoid violence in land use, such as large-scale earth moving or application of chemical pesticides; (3) inculcate among landowners a relationship with the land that goes beyond economics; and (4) limit the size of human population (Leopold [1946] 1999).

3. ECOSYSTEMS AND ECOSYSTEM HEALTH

The early twentieth century saw rapid development in the field of ecology. Leopold himself was a significant contributor to the field of wildlife ecology, beginning with his pioneering textbook, Game Management (Leopold 1933), and his writings on how conservation needs to be implemented according to ecological principles.12 Although Leopold used the familiar word “land” to refer to soil, water, plants, and animals, other scholars in ecology were coining new phrases or words to refer to similar concepts.

One of the important concepts that was founded during this period was the “ecosystem,” a term that was coined by Arthur Roy Clapham (1904–1990) after he was asked by Arthur Tansley (1871–1955) for a suitable word to describe the “biological and physical components of an environment in relation to each other as a unit” (Willis 1994). Although Tansley subsequently introduced the term to the scientific community in a seminal paper (Tansley 1935), the term did not gain traction until Raymond Lindeman (1942) applied the term in his analysis of trophic dynamics of Cedar Bog Lake in Minnesota. This groundbreaking work helped establish the concept of ecosystem in ecology and marked the advent of ecosystem ecology (Cook 1977; McIntosh 1985:196–198; Worster 1994:306–311). The ecosystem concept was given a further boost when Eugene Odum organized his influential 1953 textbook Fundamentals of Ecology around ecosystems and their structure and function. Derivative concepts that had emerged include ecosystem management (Grumbine 1994, 1997), ecosystem health (Jørgensen, Xu, and Costanza 2010), and ecosystem services (Daily 1997; de Groot, Wilson, and Boumans 2002; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2003)—the last of which has become a key focus of ecological economics (Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2010).

In the next section, we follow Leopold’s lead by exploring how human beings could be viewed as being part of the ecosystem and by characterizing ecosystem health accordingly.13 We then highlight the complexity of ecosystems and the importance of judgment when assessing ecosystem health by discussing Leopold’s essay “A Mighty Fortress” in A Sand County Almanac, in which he describes how the presence of tree diseases contributed to a flourishing wildlife in the woodlot on his farm.

3.1. The Place of Humans in Ecosystems

An ecosystem is an assemblage of life-forms, geological features, and climate factors, drawn together by biogeochemical and physical processes. Perhaps because the term “ecosystem” was invented to refer to the biophysical environment as an object of scientific study, most people would not consider humans as part of the ecosystem, although some may be aware of the interactions between humans and the biophysical environment. This dualistic mindset of viewing humans as being alienated from the natural environment, which became dominant during the modern age, has enabled us to scientifically investigate the myriad biophysical characteristics of an ecosystem. Unfortunately, the same mindset has also facilitated human exploitation of the environment to the present day.

A possible way out of our environmental predicament is to consider ourselves as another life-form of the ecosystem, or, as Leopold put it, “plain member and citizen” of the “land-community” (Leopold 1949:204). This is admittedly easier for the terms Leopold used—“land” and the less well-known ecological concept of “biotic community”—than for ecosystems, which is a widely used scientific concept often interpreted as excluding humans. However, we need to be cognizant of the fact that humans are utterly dependent on the biophysical environment and that “the unit of survival is the organism and its environment” (Bateson 1972:457). Humans are fundamentally embedded in the ecosystem, not only physically but also through the myriad interrelationships that regulate our well-being. For example, humans may not be living in a lake or a rainforest, but their living conditions are coupled to these ecosystems. The physical landscape is modified according to human minds and hands, responding to feedback from the environment and the needs of human beings; the result is that conditions of the human mind and body are reflected in the landscape.

This view of seeing the relationship between humans and the rest of the biophysical environment as being mutually constitutive is supported by studies on the microbial communities residing on or within the human body, or “human-associated microbiota” (Robinson, Bohannan, and Young 2010). It is estimated that the microbiota associated with a human body consists of trillions of microorganisms but constitutes only 1–3 percent of body mass due to its smaller mass. This microbiota plays an important role in human body function. For example, the gut microbiota helps the body to absorb energy and nutrients from food and contributes to regular immune function. Its composition is influenced by age, diet, environment (nationality), and disease and medication (Lozupone et al. 2012). These findings suggest that the human body is a superorganism—a veritable ecosystem that is in constant interaction with other, larger ecosystems. This has profound implications for our sense of self and definition of health (Pollan 2013).14 Indeed, “human health can be thought of as a collective property of the human-associated microbiota” (Robinson, Bohannan, and Young 2010:468). These insights on how human existence is conditioned by the ecology of the external biophysical environment and our (mostly internal) microbiota undermine the individualistic and self-interested model of the human being on which modern economics is based.

What we need now are mental images and descriptions to help remind us of how inescapably embedded we humans are within our physical and social context. Terms such as “ecosystem” and “environment” do not explicitly reflect this embeddedness. Tim Ingold (2006) proposed thinking of an organism (e.g., a human) as a “relational constitution of being” where an organism would be imagined as an ever-ramifying web of lines of growth, with multiple lines branching out from a single source. Each organism is enmeshed within a “domain of entanglement” and the effect of its behavior ramifies through this entanglement to varying degrees.15 Indeed, we can see that everything on the planet is part of a global domain of entanglement and constituted by relationships.

This depiction takes on greater significance when applied to humans, who, “being organisms, likewise extend along the multiple pathways of their involvement in the world” (Ingold 2006:13). The lines of growth originating from different sources become entangled with one another, such that what we refer to as “the environment”—not referring merely to the biophysical, but also the social, intellectual, spiritual, etc.—would here be depicted as a domain of entanglement. We are constantly and inextricably entangled with other humans and nonhuman organisms—past, present, and future—and the geology and climate of our planet through our lifestyle and culture. Indeed, even the most remote places on the planet can be severely affected by human activity.

If we accept that humans are embedded within an ecosystem, the next step is to think holistically and reflect upon what the intrinsic character of an ecosystem that includes human presence ought to be. As mentioned earlier, our thinking on this matter evolves alongside our concept of the human self and our relationship to the environment. To restate this idea using the terms introduced previously, our understanding of the intrinsic character of an ecosystem, when considered as the domain of entanglement of our relational constitution of being, coevolves with our thinking on the desired nature of the entanglement and our understanding of the nature of our own being, both of which are influenced by culture.

This discussion on the normative state of human being is admittedly going beyond the domain of science and reminds one of Leopold’s idea of humans as “plain member and citizen” of the “land-community” (Leopold 1949:204) living on “the land” and his correlated concepts of land ethic and land health. One possible way of studying and reflecting upon the intrinsic character of an ecosystem, for guiding human beings, is through the concept of health.

3.2. Health of an Ecosystem that Includes Humans

Health is a complex concept, whether it is applied to humans or to ecosystems. It is difficult to grasp the concept solely from a scientific perspective: its meaning cannot be fully encapsulated by a definitive description; it cannot be assessed using only quantitative tools such as metrics or indices; and it does not refer merely to a state of absence of disease (Goldberg and Garver, chapter 4 this volume).

Perhaps it is more fruitful to interpret health as a connotative concept where assessment of the condition of an organism is based not only on certain key principles, but also by taking into account the information and relationships that are relevant to its particular context. This is not a revolutionary idea; it merely makes more salient the importance of human judgment and interpretation in assessing health. Indeed, assessment of health is not a strictly scientific endeavor: our assessment of our own health is based partly on our sense of feeling about how we are doing, and we could make similar assessments of others (e.g., the people and animals who are close to us) by observing their mien (although we submit that scientific investigation requires human judgment and skills as well, more than usually recognized). This expanded, connotative sense of health enables one to recognize the complex interrelationships of being in this world, as made explicit by the terms “relational constitution of being” and “domain of entanglement” mentioned previously.

Leopold’s understanding of land health—and the land ethic that emerged from it—were the product of a lifetime of observation and interpretation. Leopold was a keen observer of the relationships that played out on the land and of the participation of humanity in them. Much of his writing is an invitation to us to “see” more in the land. However, Leopold passed away in 1948, on the threshold of the exponential rise in the ability of science to quantify. Many methodologies that emerged after Leopold’s time sought to validate human observation; however, in doing so, they devalued the knowledgeable and experienced observer relative to the well-calibrated instrument. Leopold’s ability to “read the land” would not gain traction in today’s scientific grant and publishing establishment.

Decades of methodological innovation and careful measurement have allowed us to see deeply into the genome of individuals and into the diversity of any square meter of the land. Although informing us as never before of the land and its functions, one of the products of this expanding knowledge has been an incapacitating awareness of degree of complexity at different scales of the land. The emergence of large-scale data analytics or “big data” notwithstanding, our ability to provide an integrated assessment of an abused tract of land in Wisconsin or anywhere else, although potentially informed by better data, has not advanced much beyond what was apparent to the tuned senses of Leopold. This is particularly true when we recognize that our assessment on steps to be taken next on the land must extend beyond our scientific measurements to the ethical and dimensions in which the data reside. When faced with potentially overwhelming information, although not devaluing the data, we may be wise to seek out the modern-day Leopolds—the foresters, farmers, Aboriginal elders who have spent lives in observation—and ask them what they see in the land. As scientists, we should view our science with humility, recognizing the irreducible complexity in which we are entangled and the limitations it imposes in our application of scientific knowledge to a specific problem or place. We should be open to all sources of insight, whether they are molecular measurements of gene function, remote images from space, or the understanding of a knowledgeable and experienced observer of the land.

The concept of health, which is already rich in meaning and interpretation, becomes metaphorical when applied to an ecosystem. Indeed, as discussed previously, research on human-associated microbiota suggests that the human body could be considered as an ecosystem, although humans differ from ecosystems in that humans possess consciousness while ecosystems are commonly considered otherwise by modern Western thought. However, an ecosystem can display a dynamic equilibrium and possess the potential to develop in novel ways. In this context, ecosystem health refers to the “proper” characteristics of all that is involved in the ecosystem. The concept of ecosystem health is therefore a heuristic and metaphorical device to help us deal as best we can with the complex task of characterizing and understanding ecosystems and our place in them. This interpretation may locate ecosystem health some distance away from its scientific mooring. However, because health is a connotative concept that most people can understand, applying the metaphor of health to ecosystems can yield a fruitful, if ambiguous, interpretive space to work with, which is commensurate with and suggestive of the immense potential of an ecosystem for its own evolution and development. If we extend the concept of human health broadly enough to include ecosystems, then ecosystem health may be viewed as an extension of human health and not as a metaphor. However, this view is based solely on the consideration of human well-being and neglects the multiplicity of values and perspectives in an ecosystem, as we will see in the next subsection.

The thinking that humans are part of ecosystems forces us to rethink ecosystem health and raises the question of what a healthy landscape that is inhabited by plant and animal species, including homo sapiens, would look like. In other words, given our knowledge of the intrinsic character of the nonhuman aspects of an ecosystem and our needs as a species, our present goal is to establish and maintain a healthy joint condition of both humans and the rest of the ecosystem. This ultimately leads us to confront the profound question of the relationship between humans and the other life-forms and what our role in the landscape should be. If we participate in the ecosystem—our biophysical domain of entanglement—in a respectful and mindful way, we not only minimize our impact on its natural workings, but we also preserve the long-term life-supporting mechanism for all organisms (including ourselves). In our studies of ecosystem health, we should bear in mind that we are an integral component of the ecosystem we are studying; our membership is established through our physical presence in the environment and through our consciousness (i.e., mental presence) when perceiving it.

Although Leopold’s land health concept has been credited for contributing to the emergence of the concept of ecosystem health (Callicott 1992; Kolb, Wagner, and Covington 1994; Rapport 1995), the concepts are different in terms of the contexts in which they were used. Leopold’s land health was not a stand-alone concept, but it was derived as part of his broader effort to rethink the human-land relationship with an eye toward establishing a land ethic and promoting conservation of the land. Ecosystem health, on the other hand, was conceived as a scientific concept that emerged out of the development of the field of ecology and ecosystem in the decades after Leopold’s death.

3.3. A Mighty Fortress for Life

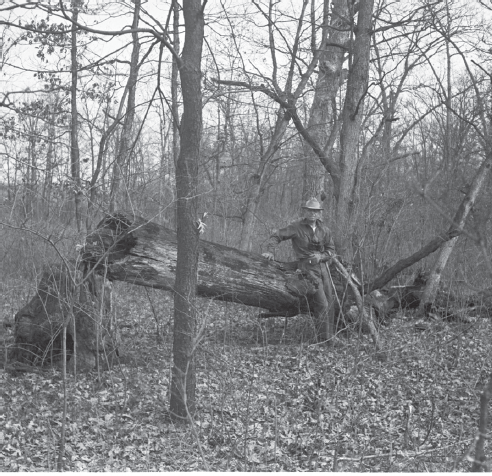

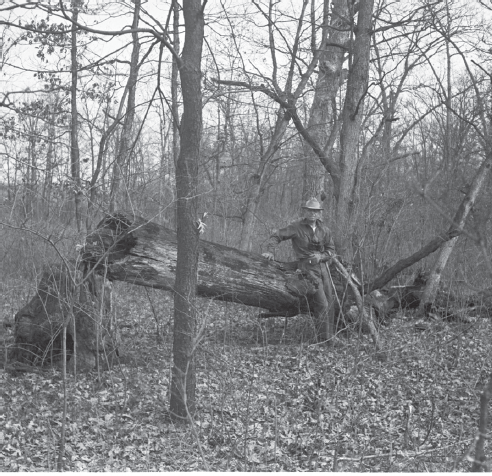

In one of his essays in A Sand County Almanac, “A Mighty Fortress,” Leopold (1949) suggested the notion of adopting a less anthropocentric position in relation to our domain of entanglement in order to allow the domain more space for its natural workings and its myriad ecological dramas to unfold. He described how disease-afflicted trees in the woodlot on his shack property enriched the woodlot with higher levels of wildlife activity. Trees that were infected by diseases and insect pests became protective habitats and rich sources of food for wildlife. Diseased and dying oak trees which became windfalls found “new life” as habitat for grouse and wild bees. Trees that were infested with termites became a rich mine of food for chickadees. The diseases in his woodlot taught Leopold that wildlife depends on diseased trees for habitat. Commenting on how a raccoon had taken refuge against a hunter in a half-uprooted maple that was weakened in the roots by a fungus disease, Leopold (1949) observed that the tree “offers an impregnable fortress for coondom [sic]”16 (see figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2. While Leopold espoused leaving diseased and dying trees in its place to promote habitat for wildlife, the opposite had occurred here. This former “raccoon tree” near the Leopold shack, with Leopold standing before it to serve as a scale, was apparently chopped down by (presumably ecologically uninformed) raccoon hunters long before this photo was taken in April 1937 (McCabe 1987:96). Source: The Aldo Leopold Foundation.

In this remarkable section, Leopold uses the metaphor from Martin Luther’s hymn, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” However, Leopold shifts its understanding dramatically, effectively substituting the word “evolution” for God. It is evolution that is a “bulwark never failing.”

These observations made on a Wisconsin farm in the early twentieth century have been explored, reiterated, and confirmed by generations of research ecologists concerned with conserving species and ecosystems. Disturbance agents such as insects, fire, and flooding are now viewed as integral components of the ecosystem (Hobbs and Huenneke 1992). Dead wood, once an anathema to the forester, is now regarded as a key resource to be valued and managed (Harmon et al. 2004). In embracing the complexity of the ecosystem and the entanglement of its entire species, we have been forced to change our perspective on what constitutes a valued component.

The implication of Leopold’s observation—that the health of an ecosystem entails the presence of what have been commonly considered as diseases—forces us to expand and reflect on our concept of health. Death and disease are part and parcel of nature and life. The health of the land is not reducible to the health of its individual constituent organisms. The labelling of species and conditions as “disease,” “pests,” or “weeds” reflects the inconvenience they cause to humans. This does not mean that we willfully tolerate infestations or plagues. Instead, we need to recognize, as Leopold pointed out, that “no species are inherently a pest”: whether a species is considered expedient for human activity depends on its population size and distribution and the interpretation of what is good by humans (Leopold [1943] 1991). This forces us to reexamine the meaning of freedom and liberty for human individuals, concepts that have come to characterize the modern age.17 Again, and going back to Leopold’s land ethic, we need to cease using our anthropocentric, economic criteria as primary measures when assessing the good of living organisms and habitats with which we are entangled.

Of course, Leopold could afford to let nature have a free hand in his woodlot because he was not hard-pressed to extract economic value from it. Indeed, from society’s point of view, the economic value of Leopold’s farm property, which was abandoned by its previous tax-delinquent owner, had already been depleted. However, this is not the current reality in most parts of the world, where the cultural narrative of progress and the economic growth imperative are causing humans to profoundly disrupt the developmental possibilities of ecosystems.

The question that confronts us humans is how our consciousness and actions will affect the long-term potential of the natural world. At the heart of this issue is whether we consider ourselves to be part of nature, and hence as agents of the forces of nature, or whether we consider ourselves to be separate from nature and hence constitute a force on this world that is distinct from that of nature. To use Leopold’s metaphors, we could adopt a conqueror’s mentality in the environment and use it as a habitat for humans only, ignoring the fact that this might undermine our own long-term viability. Or, we could view human society as inescapably embedded in the ecosystems of Earth, learning to live in a way that recognizes and supports the collective health of the ecosystems, including our own.

4. FINAL THOUGHTS

The history of civilization has been one of constant innovation, development, and evolution of human societies, as well as conflicts and wars. Our current work to reconcile the human economy with ecological principles, essentially a re-envisioning project, represents an opportunity to continue this process in a manner that is more conscious and mindful of the life-sustaining processes that our human society depends on than had been generally demonstrated in the past century or so.

Progress toward a holistic melding of ecological and economic principles would require a sound understanding of the intrinsic character of the ecosystem. Basing human action on untenable assumptions about the relationship between humans and ecosystems—from the smallest local plot of land to the scale of the entire planet—is manifest folly. Normative guides for human action with respect to the ecosystem—at the largest scale, the entire planet—must be based on a deep and critical knowledge of the ecosystem, coupled, as Leopold would hasten to add, with deep humility. This should be achieved through not only the scientific mode of thinking but also other forms of knowledge and perception, such as the humanities and the arts, which supply rich and essential metaphors for understanding human existence (Midgley 2001). We need to develop a scientifically realistic and enlightened conception of the nature of human being and our place in the ecosystem—indeed, in the universe—if we are to establish a healthy existence within it.

Recognizing the embeddedness of humans within the domain of entanglement would hopefully lead to a general respect and appreciation of the myriad life-forms and life-supporting biophysical processes of this planet. Leopold’s land ethic was the result of his understanding of the ecology of the land and his reflection of the place of humans in it. Moreover, he recognized that an ethic is constantly evolving with society (Leopold 1949:225). It is perhaps time for society—beginning with small groups, such as communities and towns—to reflect upon its place in the domain of entanglement and develop its own ethic toward it.

Such an ethic would also enable us to deal better with the complexity and uncertainty that is inherent in our domain of entanglement. Once we begin to recognize the extent of our entanglement with one another and the biophysical environment, the multiplicity of interactions would make it impossible for us to grasp every detail from an analytical perspective. The value of an ethic here is to provide an alternative way of guiding our conduct under such immensely complex situations. Leopold’s land ethic, which calls for the preservation of integrity, stability, and beauty of the biophysical environment, does not provide any specific prescriptions on human behavior. However, it provides a thought-provoking and solemn ethic against which we can evaluate our possible actions.

Human thought is inescapably anthropocentric in the sense that our thinking is biased toward ensuring human well-being in its various conceptions. Such thinking is necessary and perhaps unavoidable for our survival. However, in Western culture, this mentality has intensified in the past century or so to the point of privileging human material well-being over that of the rest of the environment, resulting in profound transformations of the planet that are detrimental to the long-term well-being of all life-forms. Our challenge, henceforth, is to consider humans and the biophysical environment as a unified whole and revise human actions according to this perspective. We need to ground human consciousness and activity in a foundation of being alive and open to a world that is always coming into being, just like ourselves. We need to learn how to cooperate with our biophysical environment instead of leading an existence that has largely been in contention with it. For this purpose, metaphors such as health can help us to cognitively and emotionally grasp what is at stake in the Anthropocene.

We are grateful to the editors, Peter Brown and Peter Timmerman, for their patience and helpful suggestions; to the other authors of the book for thought-provoking discussions; to Curt Meine and Peter Whitehouse for commenting on the manuscript; and to the Aldo Leopold Foundation for permission to use the figures in this chapter.

1. In 1924, William B. Greeley, then head of the Forest Service and Leopold’s instructor at the Yale Forest School, expressed his desire to have Leopold assume the position of assistant director at the Forest Products Laboratory with the thinking that he would succeed then-director Carlile P. Winslow; Winslow was expected to step down within a year. Leopold never fully explained his decision for the move (Meine 2010:225). However, his decision to leave in 1928 was wise in retrospect: Winslow did not step down as director until 1946 (Havlick 2009).

2. Between 1928 and 1933, Leopold conducted game surveys for Sporting Arms and Ammunitions Manufacturers’ Institute in eight north-central states (Newton 2006:107–114).

3. Following Leopold’s abrupt death in 1948 due to a heart attack, his son Luna headed a team comprising former students and friends to prepare the manuscript for publication. Perhaps the most important change was to shift “The Land Ethic” from its original first position in Part III to its present final position. See Ribbens (1987) and Meine (2010:523–524).

4. The term “biotic community” was one of the terms that was used in ecological discourse during Leopold’s time and was used in Charles Elton’s Animal Ecology (1927). Leopold was using its metaphorical aspect to describe how “the plants, animals, men, and soil are a community of interdependent parts” (Leopold [1934] 1991a:209).

5. See the chapter by Janice Harvey in this volume (chapter 11) for a discussion on culture, consumerism, and possible ways of implementing cultural change.

6. Leopold was assuming the idea that biological diversity enhances ecological stability, the “diversity-stability hypothesis,” which was challenged by studies conducted by Robert May and others. However, these studies, which were based on mathematical models, had shortcomings, including a focus on individual species population. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the hypothesis was rehabilitated by an experimentally driven research program and a shift in focus from population to ecosystem stability. See Mikkelson (2009).

7. Leopold was influenced by the work of the regional artist John Steuart Curry. From 1936 until his death in 1946, Curry was the initial appointee of the artist-in-residence program at the University of Wisconsin’s College of Agriculture, the first such program in the United States (Cronon and Jenkins 1994:783). Curry was appointed to the College’s Department of Agricultural Economics in 1943 (Glover 1952:338–339), which strongly suggests that he would have crossed path with Leopold. In the context of the sentence quoted here, Leopold cited Curry and the other two great artists of the regionalist movement in the Midwest: “What is the meaning of John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood, Thomas Benton? They are showing us drama in the red barn, the stark silo, the team heaving over the hill, the country store, black against the sunset. All I am saying is that there is also drama in every bush, if you can see it. … The landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself. Conservation implies self-expression in that landscape, rather than blind compliance with economic dogma” (Leopold [1939] 1991b: 263).

8. In Leopold’s model of the land pyramid, energy was thought to return to the soil through death and decay. This model of energy cycling through the food chain was proven wrong when Lindeman (1942) established from his study of trophic dynamics of a lake that energy flows through and out of an ecosystem (as degraded heat in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics). Thus, the energetic aspect of Leopold’s “land pyramid” was already outdated when in 1947 he incorporated it into “The Land Ethic” essay of A Sand County Almanac (Leopold 1949; Meine 2010: 501).

9. For discussion of Leopold’s thinking on ecology in light of present-day ecological findings, see, for example, Wolfe and von Berg (1988), Silbernagel (2003), Ripple and Beschta (2005), and Binkley et al. (2006).

10. These manuscripts have since been published: “Conservation: In Whole or in Part?” (Leopold [1944] 1991); “Biotic Land-Use” (Leopold [c.1942] 1999); and “The Land-Health Concept and Conservation” (Leopold [1946] 1999).

11. For a detailed discussion of Leopold’s concept of land health, see Newton (2006: 316–351).

12. At the time of his death in 1948, Leopold was thinking of revising Game Management (Meine 2010: 523).

13. For discussions on integrating humans into ecosystems, see, for example, Berkes, Colding, and Folke (2003) and Bechtold et al. (2013). The fact that the latter considered this concept as on the “frontier” of ecosystem science suggests that ecosystems are commonly perceived to be without humans.

14. Lozupone et al. (2012) used “macroecosystem” to refer to the physical ecosystem.

15. Ingold articulated these concepts as part of his critique of the conventional understanding of animism.

16. Leopold coined the word “coondom” to refer to “raccoon-dom,” the world of raccoons.

17. See the discussion on these concepts in relation to ecological economics by Bruce Jennings in chapter 10.

REFERENCES

Bateson, Gregory. 1972. “Form, Substance, and Difference.” In Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 454–471. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bechtold, Heather A., Jorge Durán, David L. Strayer, Kathleen C. Weathers, Angelica P. Alvarado, Neil D. Bettez, Michelle A. Hersh, Robert C. Johnson, Eric G. Keeling, Jennifer L. Morse, Andrea M. Previtali, and Alexandra Rodríguez. 2013. “Frontiers in Ecosystem Science.” In Fundamentals of Ecosystem Science, edited by Kathie Weathers, David L. Strayer, and Gene E. Likens, 279–296. Waltham, MA: Academic Press.

Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke, eds. 2003. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Binkley, Dan, Margaret Moore, William Romme, and Peter Brown. 2006. “Was Aldo Leopold Right About the Kaibab Deer Herd?” Ecosystems 9 (2): 227–241. doi: 10.1007/s10021-005-0100-z.

Callicott, J. Baird. 1992. “Aldo Leopold’s Metaphor.” In Ecosystem Health: New Goals for Environmental Management, edited by Robert Costanza, Bryan G. Norton and Benjamin D. Haskell, 42–56. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Callicott, J. Baird. 2008. “Leopold’s Land Aesthetic.” In Nature, Aesthetics, and Environmentalism: From Beauty to Duty, edited by Allen Carlson and Sheila Lintott, 105–118. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cook, Robert Edward. 1977. “Raymond Lindeman and the Trophic-Dynamic Concept in Ecology.” Science 198 (4312): 22–26.

Daily, Gretchen C., ed. 1997. Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

de Groot, Rudolf S., Matthew A. Wilson, and Roelof M. J. Boumans. 2002. “A Typology for the Classification, Description and Valuation of Ecosystem Functions, Goods and Services.” Ecological Economics 41 (3): 393–408. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7.

Elton, Charles. 1927. Animal Ecology. London: Sidgwick and Jackson.

Flader, Susan L., and J. Baird Callicott. 1991. “Introduction.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by S. L. Flader and J. B. Callicott, 3–31. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Glover, Wilbur H. 1952. Farm and College: The College of Agriculture of the University of Wisconsin; A History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Gómez-Baggethun, Erik, Rudolf de Groot, Pedro L. Lomas, and Carlos Montes. 2010. “The History of Ecosystem Services in Economic Theory and Practice: From Early Notions to Markets and Payment Schemes.” Ecological Economics 69 (6): 1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.007.

Grumbine, R. Edward. 1994. “What Is Ecosystem Management?” Conservation Biology 8: 27–38.

Grumbine, R. Edward. 1997. “Reflections on ‘What Is Ecosystem Management?’” Conservation Biology 11: 41–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.95479.x.

Harmon, M. E., J. F. Franklin, F. J. Swanson, P. Sollins, S. V. Gregory, J. D. Lattin, N. H. Anderson, S. P. Cline, N. G. Aumen, J. R. Sedell, G. W. Lienkaemper, K. Cromack, Jr., and K. W. Cummins. 2004. “Ecology of Coarse Woody Debris in Temperate Ecosystems.” In Advances in Ecological Research, edited by H. Caswell, 59–234. Waltham, MA: Academic Press.

Hobbs, Richard J., and Laura F. Huenneke. 1992. “Disturbance, Diversity, and Invasion: Implications for Conservation.” Conservation Biology 6 (3): 324–337. doi: 10.2307/2386033.

Ingold, Tim. 2006. “Rethinking the Animate, Re-Animating Thought.” Ethnos 71 (1): 9–20. doi: 10.1080/00141840600603111.

Jørgensen, Sven Erik, Fu-Liu Xu, and Robert Costanza, eds. 2010. Handbook of Ecological Indicators for Assessment of Ecosystem Health. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Kolb, T. E., M. R. Wagner, and W. W. Covington. 1994. “Concepts of Forest Health: Utilitarian and Ecosystem Perspectives.” Journal of Forestry 92 (7): 10–15.

Leopold, Aldo. (1915) 1991. “The Varmint Question.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 47–48. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. 1933. Game Management. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Leopold, Aldo. (1933) 1991. “The Conservation Ethic.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 181–192. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1934) 1991a. “The Arboretum and the University “ In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 209–211. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1934) 1991b. “Conservation Economics.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 193–202. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1935) 1991. “Land Pathology.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 212–217. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1938) 1991. “Engineering and Conservation.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 249–254. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1939) 1991a. “A Biotic View of Land.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 266–273. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1939) 1991b. “The Farmer as a Conservationist.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 255–265. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1941) 1991. “Wilderness as a Land Laboratory.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 287–289. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1942) 1991. “The Role of Wildlife in a Liberal Education.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 301–305. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1942) 1999. “Biotic Land-Use.” In For the Health of the Land: Previously Unpublished Essays and Other Writings, edited by J. Baird Callicott and Eric T. Freyfogle, 198–207. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1943) 1991. “What Is a Weed?” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 306–309. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1944) 1991. “Conservation: In Whole or in Part?” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 310–319. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1945) 1991. “Review of Young and Goldman, the Wolves of North America.” In The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 320–322. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1946) 1999. “The Land-Health Concept and Conservation.” In For the Health of the Land: Previously Unpublished Essays and Other Writings, edited by J. Baird Callicott and Eric T. Freyfogle, 218–226. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Leopold, Aldo. (1947) 1987. “Foreword.” In Companion to a Sand County Almanac: Interpretive & Critical Essays, edited by J. Baird Callicott, 281–288. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leopold, Aldo. 2013. A Sand County Almanac & Other Writings on Ecology and Conservation. Edited by Curt Meine. New York: Library of America.

Lindeman, Raymond L. 1942. “The Trophic-Dynamic Aspect of Ecology.” Ecology 23 (4): 399–417. doi: 10.2307/1930126.

Lozupone, Catherine A., Jesse I. Stombaugh, Jeffrey I. Gordon, Janet K. Jansson, and Rob Knight. 2012. “Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota.” Nature 489 (7415): 220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550.

MacCleery, Douglas W. 2000. “Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic: Is It Only Half a Loaf?” Journal of Forestry 98 (10): 5–7.

McCabe, Robert A. 1987. Aldo Leopold: The Professor. Madison, WI: Rusty Rock Press.

McIntosh, Robert P. 1985. The Background of Ecology: Concept and Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Meine, Curt. 2004. Correction Lines: Essays on Land, Leopold, and Conservation. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Meine, Curt. 2010. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Midgley, Mary. 2001. Science and Poetry. London: Routledge.

Mikkelson, Gregory M. 2009. “Diversity-Stability Hypothesis.” In Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy, edited by J. Baird Callicott and Robert Frodeman, 255–256. Detroit: Macmillan.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2003. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Framework for Assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Newton, Julianne Lutz. 2006. Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Odum, Eugene P. 1953. Fundamentals of Ecology. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Rapport, David J. 1995. “Ecosystem Health: More Than a Metaphor?” Environmental Values 4 (4): 287–309.

Ribbens, Dennis. 1987. “The Making of a Sand County Almanac.” In Companion to a Sand County Almanac, edited by J. Baird Callicott, 91–109. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ripple, W. J., and R. L. Beschta. 2005. “Linking Wolves and Plants: Aldo Leopold on Trophic Cascades.” Bioscience 55: 613–621. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0613:LWAPAL]2.0.C.

Robinson, Courtney J., Brendan J. M. Bohannan, and Vincent B. Young. 2010. “From Structure to Function: The Ecology of Host-Associated Microbial Communities.” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 74 (3): 453–476. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00014-10.

Silbernagel, Janet. 2003. “Spatial Theory in Early Conservation Design: Examples from Aldo Leopold’s Work.” Landscape Ecology 18 (7): 635–646. doi: 10.1023/B:LAND.0000004458.18101.4d.

Tansley, A. G. 1935. “The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms.” Ecology 16: 284–307.

Turner, Monica G. 2005. “Landscape Ecology: What Is the State of the Science?” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 36: 319–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102003.152614.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2012. 2010 Census of Population and Housing: Population and Housing Unit Counts. CPH-2–1, United States Summary. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Accessed January 20, 2015. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-1.pdf.

Willis, A. J. 1994. “Arthur Roy Clapham. 24 May 1904–18 December 1990.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 39: 72–90. doi: 10.1098/rsbm.1994.0005.

Wolfe, Michael L., and Friedrich-Christian von Berg. 1988. “Deer and Forestry in Germany: Half a Century after Aldo Leopold.” Journal of Forestry 86 (5): 25–31.

Worster, Donald. 1994. Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.