Are drugs, which comprise about 10 percent of overall health-care costs,1 part of the health-care cost problem? Or are they part of the solution? Critics of the pharmaceutical industry often point to the rise in spending on pharmaceuticals—which doubled between 1995 and 2002—as a major culprit in the unsustainable increase in health-care spending during these years.2 Others assert that while they are expensive on a per-ounce basis, pharmaceutical solutions are much cheaper than other alternatives for care.

Both views have merit. Some drugs have helped to transform historically fatal acute diseases into chronic ones, allowing us to live longer with reasonable qualities of life. While extending both the length and quality of our lives, these drugs have played a major role in driving up the world's health-care bill—not just through the cost of the drugs themselves, but through the cost of complications that arise as patients live with, rather than succumb to, these diseases.

Other drugs drive down the cost of care, however, because they're the technological enablers of disruption.3 Little by little and layer by layer, scientists and physicians are peeling away the shrouds that have masked true understanding of diseases, leading us toward greater precision. Many of those who lead this transformation of knowledge are academic scientists ensconced in or adjacent to our best medical schools, funded through grants from our National Institutes of Health. However, much of the applied science and nearly all of the commercialization technology in this transformation is being developed and implemented in pharmaceutical and medical device companies. Indeed, the most recent victories in the march toward precision medicine have emerged from firms like Novartis (Gleevec), AstraZeneca (Iressa),4 Genentech (Herceptin), and others. The pharmaceutical and medical device industries must play a pivotal role in the disruptive transformation of health care, because they supply the technological enablers that allow lower cost venues of care, and lower cost caregivers, to do more and more remarkable things. In this chapter we'll consider the role that pharmaceutical companies will need to play in transforming health care, and then turn toward devices in Chapter 9.

The disruptive transformations in health care will profoundly affect the structure of the pharmaceutical industry itself—posing extraordinary managerial challenges to the leaders of these companies. The disruption that threatens today's "big pharma" companies is of a different sort than was mounted by steel minimills, personal computer makers, Wal-Mart, and Toyota. Those disruptors started with simple, affordable products that were sold to the least-demanding customers. They then marched up-market, market tier by market tier. We call the disruptive threat to pharmaceutical companies a "supply chain disruption," and it is already under way in the industry. Its form: many of the vertically integrated pharmaceutical companies that have long dominated the business began actively outsourcing many of their functions to specialist companies, ranging from the discovery and development of new drugs, to the administration of clinical trials, to manufacturing. Those to whom this work is being outsourced are integrating to add more and more value to their offerings, even as the pharmaceutical companies are shedding activity after activity, seeking to do less and less.

The driver of this disruption is the same as the one that drives "market tier" disruption. The leaders improve their profitability by getting out of the least profitable of their activities, while focusing investments on the most profitable. The disruptive entrants, by inheriting the activities cast off by the incumbent leaders, improve their profitability by taking on more and more of the value-adding activities the leaders are "outsourcing."

Unless they reverse course, many of today's major pharmaceutical companies will find a decade from now that they have inadvertently leveled the playing field in their industry, so that entrants can overcome what historically had been high barriers to entry. They will find that they outsourced to suppliers those activities they will wish had become their core competencies. And the activities that the majors in the past have considered to be their core competences—especially sales and marketing—will in the future prove to have lost much of their competitive relevance. After this disruption occurs, the pharmaceutical industry will be much more efficient and effective in leading health care toward precision medicine. Whether today's major companies lead in this transition or become victims of it will depend on how adroitly their executives navigate their corporate ships through these disruptive shoals.

To illustrate how and why disruption up the supply chain occurs, we'll recount the interaction between a supplier—a small (initially, at least) Taiwanese electronics manufacturer called ASUSTeK, and its customer, Dell Computer. We have chosen this pair because the interaction we typify below is common to all companies that find themselves experiencing this phenomenon of supply chain disruption.

ASUSTeK started out making the simplest of the circuit boards within a Dell computer. Then ASUSTeK came to Dell with an interesting value proposition: "We've been doing a good job making these little boards. Why don't you let us make the motherboard for you? Circuit manufacturing isn't your core competence anyway, and we could do it for 20 percent lower cost."

Dell's analysts examined the proposal and realized, "Gosh, they could! And if we hand off the motherboard to them, we can also get all those circuit manufacturing assets off our balance sheet!" So they transferred the making of the motherboard to ASUSTeK. Dell's revenues were unaffected, but its profits improved significantly. ASUSTeK's revenues improved, and its profits improved—because it was utilizing its assets more efficiently. In other words, it felt good for Dell to get out of motherboards, and good for ASUSTeK to get into motherboards.

Then ASUSTeK came back. "You know, we've been doing a good job making these motherboards for you. Come to think of it, the motherboard is really the guts of the machine. You shouldn't have to bother to assemble the rest of the computer. Let us do it for you. Assembly isn't your core competence anyway, and we'll do it for 20 percent lower cost."

Dell's analysts examined the proposal and realized, "Gosh, they could! And if we hand off assembly to them, we can also get these manufacturing assets off our balance sheet!" So they transferred responsibility for computer assembly to ASUSTeK. Dell's revenues were unaffected, but its profits improved significantly. ASUSTeK's revenues improved, and its profits improved—because again it was utilizing its assets more efficiently. It felt good for Dell to get out of assembly, and good for ASUSTeK to get into assembly.

Then ASUSTeK came back. "You know, we've been doing a good job assembling your computers for you. Come to think of it, you shouldn't have to bother to manage your supply chain—dealing with all those component suppliers, working out all those logistics headaches, and shipping those computers to your customers. Logistics isn't your core competence anyway. Why don't you let us take on the management of your supply chain? We could do it for 20 percent lower cost."

Dell's analysts examined the proposal and realized, "Gosh, they could! And if we give the supply chain to them, we can not only reduce costs, but also get all the current assets off our balance sheet!" So they transferred responsibility for the supply chain to ASUSTeK. Dell's revenues were unaffected, and this time its profits improved even more than before—especially return on assets, because they had no assets. (As you may have noticed, Wall Street loves asset-light companies.) ASUSTeK's revenues improved again too, and its profits improved—because it was getting into value-added services. (As you may have noticed, Wall Street loves value-added services companies.) It felt good for Dell to get out of managing the supply chain, and good for ASUSTeK to begin managing the supply chain.

Then ASUSTeK came back. "You know, we've been doing a good job managing your supply chain. Come to think of it, you shouldn't have to bother to design those computers, because design is little more than component selection—and we have all those relationships. Why don't you let us design your computers for you? We could do it for 20 percent less."

Dell's analysts examined the proposal and realized, "Gosh, they could! And if we hand off design to them, we can fire our engineers and drive our costs even lower! Besides, it's our brand that's our core competence." So they transferred responsibility for computer design to ASUSTeK. Dell's revenues were unaffected, but its profits improved again. And ASUSTeK's revenues and profits improved. It felt good for Dell to get out of design, and good for ASUSTeK to get into it.

As we write this book, ASUSTeK is in the process of coming back one more time. But this time they aren't coming back to Dell, but to the giant electronics retailers like Best Buy. And they're saying, "You know, we design and manufacture some of the best computers in the world. Why should you have to bother stocking those Compaq, Hewlett-Packard, and Dell brands on your shelves? We'll give you your brand, our brand—any brand—at 20 percent lower cost."

Bingo. One company is gone, another has taken its place. How did it happen? There's no stupidity in the story. The managers in both companies did exactly what business school professors and the best management consultants would tell them to do—improve profitability by focusing on those activities that are most profitable, and by getting out of activities that are less profitable. Just like the types of disruption where an entrant company comes into the bottom tier of a market and then eats its way up-market, tier by tier, the causal mechanism of supply chain disruption is the pursuit of profitability. The pursuit of profits is what causes the customer to keep handing off the lowest of the value-adding activities that remain in the company. And it is the pursuit of profitability that causes the supplier to seek offering ever higher value-adding activities to its customers.

The reason why disruption is such a predictable phenomenon is that the pursuit of profit causes the industry's incumbent leaders essentially to flee from the entrant attackers—when the attackers enter into the least profitable tier of the market, or the lowest value portion of the supply chain. And it is the pursuit of profit that so predictably propels the attackers to try to capture the next tier of the market, or the next stage in the value chain. To the disruptee, these are the least profitable of their remaining activities; to the disruptor, these are the most profitable of their activities.

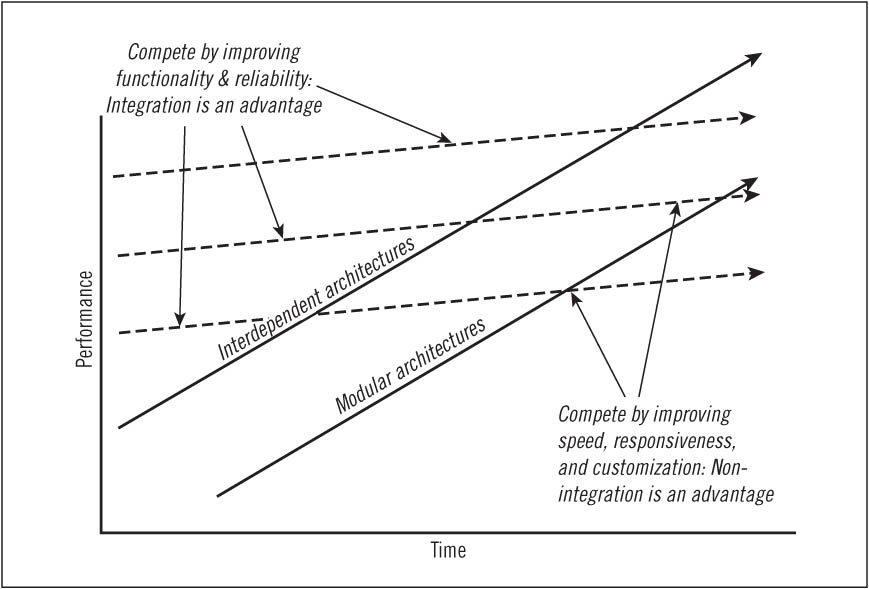

In our studies of strategy and innovation, one constant is that when there are unpredictable interdependencies among pieces of a product system, a company's span of integration must encompass those interdependencies in order to be successful—and the type of supply chain disruption described above is impossible. The period in an industry's history when these conditions seem most prevalent is depicted in Figure 8.1. It occurs in the early years of an industry, when the technology is immature and the best products don't perform well enough that companies need interdependent, optimized solutions to optimize performance. For example, in the early years of mainframe computing, a company could not have existed as a stand-alone provider of operating systems, logic circuitry, memory systems, or applications software. The design of each of these elements of the system depended at that time on the design of each of the other elements. Hence, a computer company had to do everything if it hoped to do anything, and a significant competitive advantage accrued to companies that were vertically integrated.

The advent of advanced digital radiology services was characterized by similar interdependence. There were no standards to define how CT scanners, computer image stations, storage systems, and transmission services could interface—so giant, integrated systems providers were the only entities that could play in this game.

If a company wished to assemble a computer or a digital imaging system in that era (the upper-left portion of the disruption diagram) from modular components, it would have had to specify how each piece of the system interfaced with each other piece of the system. However, even specifying those interfaces, let alone standardizing them, would have required far more technological understanding than existed in the early years of either of these industries. It also would have taken so many degrees of design freedom away from the engineers that they would have had to back off the frontier of what was technologically possible—and during the stage of an industry's history when product performance and reliability aren't yet sufficient, that would be competitive suicide. When products don't perform well enough or reliably enough, competitive advantage goes to those firms that compete with proprietary, optimized product or process architectures.

Interdependence—the requirement to create everything at once—raises the fixed cost of participating in an industry. This then creates steep economies of scale—conferring cost advantages on larger companies. Interdependence also creates many opportunities for competitive differentiation. The result of these factors is that vertically integrated giants grow to dominate nearly every industry in its early years. AT&T, U.S. Steel, Alcoa, Swift, General Motors, Ford, IBM, Digital Equipment, DuPont, Goldman Sachs, Citibank, United Aircraft,5 and Harvard Business School are just a few examples of institutions that came to industry leadership by taking advantage of vertical integration.6

Incidentally, this is why (as of this writing) Apple's iPod portable music player has so quickly grown to dominate its industry. Other companies' attempts to assemble systems from modular components resulted in difficult-to-use, unreliable products. But by optimizing end-to-end the integration of its iTunes music store with the formatting and technology for downloading music and the design of its iPod player, Apple created an elegantly simple system against which companies with nonoptimized, industry standard architectures cannot now compete.7

During this early era in an industry's history supply chain disruption generally cannot occur—because for the industry leaders, outsourcing is not technologically feasible or competitively desirable.

FIGURE 8.1 Circumstances in which integration or nonintegration is an advantage

When an industry's technology matures and its products begin performing well enough, however, the architecture of an industry's products or services can become modular—meaning that the standards by which the different components must interface can be specified with sufficient clarity and comprehensiveness so independent companies can supply individual components. And when the components are all "snapped" together, the product performs sufficiently well. Under these conditions, industries formerly dominated by vertically integrated behemoths come to be structured as a horizontally stratified collection of specialist companies.8

We've illustrated in Figure 8.2 how this happened in the computer industry, by listing on the left side the stages in the value chain of building and servicing a computer. During the industry's first two decades, it was dominated by vertically integrated companies such as IBM, Control Data, and Digital Equipment—because they had to be integrated, given the nature of the technology and the basis of competition at the time. But as part of its orchestration of the disruptive personal computer value network, IBM defined what the components of a personal computer would be, and established clear standards by which those components would interface in the product's architecture. As a result, the industry disintegrated, as shown on the right side of the diagram. It came to be comprised of a horizontally stratified group of focused, independent makers of each component—including Microsoft, Intel, Seagate, and so on.9

Merck, Pfizer, and most of the other major pharmaceutical companies can trace their beginnings to specialized chemical factories that manufactured and supplied compounds for the pharmacy industry. Over time, they integrated into adjacent activities, such as researching and developing new drugs, distributing products to pharmacies and hospitals, and marketing the drugs to various consumers and institutions. Just like IBM, General Motors, U.S. Steel, AT&T, and the other companies listed previously, vertical integration across the spectrum from researching new compounds to the sale and advertising of their products has been a competitive strength to the major pharmaceutical companies. The differentiation and steep scale economics stemming from this enabled the leading pharmaceutical companies to extract enormous profits for many years.

FIGURE 8.2 Eras of integration and specialization in the computer industry

Little by little, however, the pharmaceutical industry has been dis-integrating. Companies like Myriad Genetics are focusing primarily on diagnostics development. Many of the major companies are increasingly relying upon contract discovery companies like WuXi PharmaTech, or upon in-licensing drugs from smaller firms in order to offload the risk associated with drug discovery. These in-licensed products already represent 30 percent of "Big Pharma" sales today.10

Meanwhile, other portions of the drug development process are also being outsourced. As the process of running clinical trials became better defined—and more complex, due to FDA regulations—Quintiles, ICON, PAREXEL, PPD, Covance, and other contract research organizations have offered to take on the burden of managing trials for pharmaceutical firms. Clinical trials have become extraordinarily costly because of the number of patients needed, the number of geographic sites involved, the complex regulatory hurdles in place, and the potential need to engage multiple areas of medical expertise. Converting the fixed costs of managing these trials year-round into variable costs better suited for an unpredictable product pipeline has relieved some of the cost pressures on the leading pharmaceutical companies. Not surprisingly, however, some CROs have gradually integrated—as did ASUSTeK in computers—across the spectrum of activities in the value chain from discovery to formulation and product development, to contract manufacturing, marketing, and detailing. Some have even begun competing against their customers.11 For example, Covance announced in August 2008 that it would acquire an early drug development site from Eli Lilly. As part of its 10-year service agreement with Covance, Lilly was also expected to close the Lilly Center for Medical Science at Indiana University Medical Center, as Covance uses its own clinic in Evansville to conduct Phase I clinical trials.12

Likewise, specialized manufacturing and marketing organizations have also sprung up to help the major pharmaceutical companies transform fixed costs into variable ones. Codexis in the United States, Hovione in Portugal, Cadila Health Care in India, and Shanghai Pharmaceutical Group in China are a few of thousands of contract manufacturers worldwide that are expected to comprise a $145 billion market by 2009.13 Contract sales and marketing firms such as Ventiv Health and Professional Detailing, Inc. can assemble and train large sales forces that make in-house salespeople superfluous.

This progressive dis-integration has been a powerful leveler of the playing field in the pharmaceutical industry. Whereas the cost of integration posed a nearly insurmountable barrier to entry in the past, the business model of the "virtual" pharmaceutical company has become a viable option for new entrants—even while some of our largest and historically most powerful pharmaceutical companies have been outsourcing their way toward becoming little more than product portfolio managers.14 We'll see below that when this happens in an industry, the playing field doesn't stay level—it tilts away from the old leaders, in favor of a new set of companies.

An important driver of pharmaceutical industry dis-integration has been the mismatch of scale economics at different points in its value chain. In some elements of this chain the scale required to compete successfully has been huge. At other points small companies can compete very effectively against large ones because scale economies are essentially flat.

To illustrate how a mismatch in scale economics can drive industry dis-integration, we'll draw upon a case study that chronicles the emergence of the Big Idea Group.15 BIG began by holding "Big Idea Hunts" in which it searched for innovative ideas for toys in communities around the country. Through advertisements in hobbyist magazines, BIG's founder, Mike Collins, would invite people who had invented new toys or games to come to a hotel conference room to present their idea to Mike and a panel of his colleagues who had a demonstrated intuition for spotting successful new toy products. When they spotted one with high potential, they'd sign a licensing arrangement with the inventor, shape the idea into an appealing prototype and business plan, and then license it to any one of 70 toy makers or retailers whose business model and reach into the marketplace seemed to best fit the idea. Who brought their inventions to these Big Idea Hunts? An extraordinary collection of unlikely people—including retail clerks, homemakers, office managers, Ph.D. physicists, and lawyers.

When Collins decided not to license an inventor's idea, he was always careful to feed back to the inventor what it was about the idea that made it less appealing—in hopes that he could maintain a close relationship with each inventor and help them get better at inventing. Little by little BIG developed a network of thousands of inventors who just got better and better at inventing. Collins's database showed the types of inventions that each of these people had demonstrated an instinct for developing. Companies not in the toy industry soon began asking Collins if he could conduct Big Idea Hunts for them. These included makers of household utensils, office products, lawn and garden tools, and even medical devices. As he broadened his scope, Collins gradually found that instead of advertising broadly for inventors to bring their ideas to his hunts, he simply could parse his database of inventors who in the past had demonstrated an intuition for inventing the sort of new product BIG's client was searching for. He could then solicit entries in a more targeted and efficient way—with great success. It turned out that even multi-billion-dollar companies could not afford to assemble an R&D staff that could compete against Collins, who had at his fingertips access to a network of thousands of proven inventors.16

There is a clear pattern in the types of industries where the BIG model of outsourcing new product development can work, and where it cannot. There are certain industries—which include toys, office products, household utensils, gardening tools, and medical devices—where you don't have to be big at all in order to develop a new product. The minimum efficient scale is two people. You come up with an idea, and then as long as you have a mechanical engineer in the family or the neighborhood who can help fabricate a prototype, you're in business. When you sum up the innovative power of all these people, it just overwhelms the R&D capabilities of even the largest companies in these industries. Most of these inventors don't have a prayer of building a successful company around their inventions, however, because the scale required to take them to market through Staples, Toys 'R' Us, Wal-Mart, Home Depot, and hospital association buying groups is huge. The mismatch of scale intensiveness at the different stages in the value chain causes companies in these industries to dis-integrate at the interface between development and commercialization. Henry Chesbrough has labeled this "open innovation."17

There is a type of industry where this sort of open innovation is not possible, however. It is where the minimum efficient scale of product development is large, and where there are unpredictable interdependencies between what happens in the commercialization stages of the value chain and what needs to happen in the invention and development stages. Historically, the microprocessor business was one of these. The scale required to be competitive in the development, manufacturing, and marketing stages of the value chain was huge—and there were powerful interdependencies between the way you manufactured the product and the way it could and could not be designed; and so on.18

The mismatch in minimum efficient scale explains, at least partially, why the world of drug discovery and development has become so crowded with start-up biotechnology companies, and why the traditional pharmaceutical companies, try as they might, have not succeeded in dominating the science of biotechnology in the way they had come to dominate the small-molecule chemistry of traditional pharmaceuticals. The nature of understanding in molecular biology, and the scale of an enterprise required to push that understanding forward, are such that small companies can compete with big ones in the discovery and development of biotech products. Open innovation wasn't possible in the pharmaceutical industry of the past, but it is now.

There is a compounding factor favoring dis-integration, in addition to the newfound technological feasibility of open innovation. We might term this factor a "predictability mismatch" across the stages in the value chain. Since its inception, the essentially random process of discovering successful new products has been a constant and fundamental plague that pestered the pharmaceutical industry. Discovering new molecular entities, identifying their sites of action, investigating their potential efficacy against human diseases, and determining their safety profiles remain for the most part matters of costly trial and error. Recent advances such as combinatorial chemistry and high-throughput screening do not solve the underlying problem of inherent randomness, which stems from the fact that our understanding of how the body works is still frighteningly limited. Rather, these technologies primarily serve to automate this process of random discovery.19

When pharmaceutical companies like Lilly and Pfizer serendipitously find themselves with new drugs like Prozac and Viagra,20 they must build a commercial business to take that drug to a segment of patients and their caregivers. However, when those commercial organizations are in place and their managers are held accountable for growing their business, they find themselves asking their random discovery process to somehow predictably deliver next-generation drugs that even more effectively address the unmet needs of patients and doctors in the same field. The result is that, increasingly, the marketing mass of the pharmaceutical companies forces them to in-license drugs that fit with their marketing presence. This is another driver of disintegration in the industry.21

The fact that their industry is dis-integrating poses the hazard that at each stage in their value chain, the integrated companies increasingly face competition from focused firms. The pharmaceutical giants face war on all fronts, while the focused attackers face war on just one.

Possibly the more serious threat that the major players face, however, is that they will choose to win the wrong war. They are very likely to focus on winning at the stage in the value chain that was profitable in their past, and will flee from the fight for the territory in the value chain where attractive profits will be made in the future. Therapeutics is where most of the money was made in the past, and the majors will fight to win that battle. Yet diagnostics is where the most attractive profits will be made in the future.

We have termed this challenge as "skating to where the money will be," in honor of the great Canadian ice hockey player, Wayne Gretzky. When asked once why he had become such a dominant player, Gretzky is said to have responded, "I skate to where the puck is going to be, not to where it has been."22 At times of disruptive transition such as the one facing the pharmaceutical industry, we can expect most players in the industry to "skate" toward, or invest at, the points in the value chain where the money has been made in the past. If history is any guide, when they get there, it's likely they discover that the money has moved to another point in the chain.

The diagnostics industry in the United States is presently comprised of over 200 companies accounting for $28.6 billion in sales.23 To date, the numbers logged by diagnostics makers have been dwarfed by the $300 to $400 billion pharmaceutical market.24 Diagnostics products historically have been less valued than businesses in the pharmaceutical industry. Diagnostic tests have often been perceived as adding limited value to clinical decision making: tests are defensive, directional, or confirmatory in nature, and meant to guide and reinforce the intuition of the physician rather than supplant it. As a result, diagnostics have been assigned low value by the reimbursement schedule established by Medicare. Diagnostics comprise only 1.6 percent of Medicare payments—though the savings resulting from precise diagnosis, and the costs that stem from inaccurate diagnosis—dwarf this number.25

With this heritage as baggage, new precision diagnostics are often reimbursed at the same rate as their predecessors. This tendency is exacerbated when firms seek reimbursement for new diagnostics within existing CPT codes26 rather than attempting to establish a new code with the American Medical Association. This practice rewards diagnostic tests that lower testing costs, but not necessarily those that deliver more value per dollar by enabling lower-cost caregivers such as nurses to deliver predictably effective therapies. This impedes the development and use of genetic and molecular diagnostics that may be costlier, but offer savings in other parts of the health-care system—a key reason why the perspective that stems from integration is so crucial in implementing disruption in this industry. When the cost of diagnosis comes out of one organizational pocket, and the savings it enables are put into another, the system can't be expected to make decisions that are optimal for the system. We believe the pricing that reflects the true value of precise diagnoses will emerge from the contracting between diagnostics providers and integrated fixed-fee providers.27

The accurate diagnosis of a disease and its predictably effective treatment are akin to a lock and key, both of which are necessary to open the doors to new business models of health-care delivery that we have described. Just as the technological enablers of disruption in the computer industry—the microprocessor and the Windows operating system—captured a significant portion of the profits as the personal computer disrupted larger machines, the attractive money in the pharmaceutical industry will be made at the interface of diagnostics and therapeutics, because it will fuel the growth of care provided in lower-cost business models.

The "Five Forces" framework propounded by strategy scholar Michael Porter has explained for a generation of analysts why particular elements of an industry's value chain seem to have the ability to capture a disproportionate share of an industry's profits.28 Porter's is a static model, in that it explains why things occur as they do at a given point in time. The model of disruption adds a dynamic dimension to his model, showing how the impact of these Five Forces shifts in predictable ways to different portions of the value chain over time. It shows when, how, and why the stage in the value chain where the Five Forces have historically concentrated the ability to earn attractive profits are likely to become lackluster and commoditized, and allows one to predict when stages in the chain that historically had languished in marginal profits are likely to become very attractive.29

To illustrate why understanding the dynamic dimensions of the Five Forces is so critical for today's pharmaceutical industry executives, consider the massive strategic mistake that executives in IBM's personal computer business made when they were in an analogous situation to where pharmaceutical companies are today.

In the world of mainframe computers, performance was determined at the level of the system architecture. IBM computers were built from thousands of different components, none of which substantially determined how well the machine would perform. Rather, performance was determined at the level of the system, through the artistry employed by the system engineers who knitted these components together. By some reports, 95 percent of the industry's profits were earned by IBM. Its components suppliers, in contrast, lived a miserable, profit-free existence year after year—because no individual component impacted the performance of the computers in a significant way.

When IBM set up its separate personal computer business unit in Florida, it possessed better microprocessor technology than Intel, and better operating system technology than Microsoft. But it chose to outsource those components, so it could focus on the design and assembly of computers. What happened, of course, was that IBM put into business the two companies that subsequently made the lion's share of the industry's profits, while it stayed at the stage in the value chain—in system design and assembly—where no company subsequently was able to make attractive profits.

Why did IBM do this? Because in its past, components weren't the place where attractive profits were made. But in the disruptive personal computer system, as well as in almost all disruptions, it is the technological enablers inside the product that determine the product's performance—and that is where the money is made in the new disruptive industry. As a general rule, money is made at the stage(s) in the value chain where the performance of the overall system is determined. In the early stages, performance tends to be determined through the proprietary design of the product itself. As disruption proceeds and the architecture of the product becomes more standardized and modular, however, more of the product's performance is determined by the performance of the components inside the product. Hence, in the prior example, the ability to make money shifted to certain components because it was Microsoft and Intel inside that drove the computer's performance. There was little proprietary artistry through which engineers knit those components together.

Major automobile manufacturers have done the same thing as IBM's executives: they walked away from the right war, in order to win the wrong one. Because historically components businesses weren't as profitable as the business of designing and assembling cars, through the 1990s consultants, financial engineers, and investment bankers prodded the major auto companies to divest their auto parts businesses and begin procuring major subsystems from "Tier One" suppliers. Those executives were reacting to the auto manufacturers' past, not their future—because as the architecture of the car became more standardized, the subsystems inside the car would become most profitable and increasingly proprietary, since they determine the performance of the automobile. Though we warned of this more than a decade ago,30 the outsourcing of tomorrow's critical competencies has proceeded apace in the auto industry. The leading Tier One suppliers are now significantly more profitable, and their stock market earnings multiples significantly higher, than the auto assemblers.31

In pharmaceuticals, in general, the key technological enabler limiting therapeutic efficacy is diagnostics.32 Yet (and not surprisingly), a parallel pattern of the divestiture of tomorrow's attractive businesses has begun in the pharmaceutical industry. For example, Bayer recently sold its diagnostic unit for $5.3 billion. In 2007, Abbott Laboratories negotiated to sell much of its diagnostics business for $8.13 billion.33 These companies, following the tradition established by IBM and General Motors, are reacting to the past rather than preparing for the future. A warning to all who contemplate these deals is that the investment bankers who urge them on have been prone to peer into the future through a rearview mirror.

At the same time, molecular diagnostics firms like Celera Genomics and Applied Biosystems,34 sensing the strong technological interdependence between diagnostics and therapeutics in the future, have already begun to acquire pharmaceutical companies. Other players, like Millennium Pharmaceuticals, have worked in diagnostics and pharmaceuticals from the start, while Roche has a long history of impact in both industries. As the systemic value created by precision diagnostics and predictably effective therapeutics becomes more apparent, we expect that the Five Forces determining attractive profitability will shift to this point in the industry's value chain.

Indeed, as the biomarkers that render a more precise signal of a specific disease are identified for more and more drugs, the threats of malpractice litigation will increasingly center on those who prescribed inappropriate drugs or dosages because they did not utilize available diagnostic tools.35 The recent push to incorporate genetic testing into the protocol for administering the blood thinner warfarin (also known as a nomogram), an example we discussed in Chapter 2, indicates a willingness and desire of the system to improve clinical care by combining testing and treatment.36

The value created by precision diagnosis can be significant. One study, for example, measured that the breast cancer therapeutic Herceptin cost $79,181 per patient cured if the diagnostic test to identify the overexpression of the HER2 protein was not done first. When the diagnostic test was performed at the outset, the cost per patient cured was $54,738. The reason? Without the precise diagnosis, the drug was given to some patients who could not benefit from it. The test, by the way, costs $366 to perform, and yielded nearly $24,000 in savings per patient.37

In recent years the stages in the pharmaceutical value chain have become "modular" enough that focused companies have emerged, as noted above, to perform each of these steps in relative independence from the other specialists up- and downstream in the chain. As a result and in particular, pharmaceutical companies have begun to outsource more of their clinical trials to focused contract research organizations such as Quintiles. The CROs are developing superior competencies in designing and managing these trials.

To capitalize on the promise that precise diagnosis brings for precision medicine, however, the steps in the industry's value chain will need to become more interdependent in the future—and much of the interdependence will center around the clinical trials process. This means today's industry leaders that have begun outsourcing the management of these trials are also outsourcing tomorrow's core competence. And it means that tomorrow's pharmaceutical giants will be operationally integrated differently than are those of today.

The process that drug companies historically have followed to win approval to manufacture and market a drug has been comprised of four steps. First, the safety and efficacy of the drug must be "modeled" in animals that can mimic the human disease of interest as closely as possible. The next step, called Phase I, tests the drug's safety on human volunteers, some of whom might not even have the disease in question. When safety is established, a preliminary sense of efficacy in humans is then explored in Phase II trials by administering the drug to a relatively small group of volunteers who have been diagnosed with the disease in question. If the drug is found to be effective in a sufficient portion of those patients, it is then tested in a Phase III trial, using a much larger group of diagnosed patients for a much longer period of time. In most cases the trials are conducted on a "double blind" basis: neither the patients nor the researchers are aware of whether the new drug or a placebo (occasionally a control drug) has been administered until the study has concluded.

The result of most Phase III trials is that only a portion of those who received the drug respond favorably to it. In most cases a fraction of patients report undesirable side effects as well. If the group of physicians advising the FDA feels that the treatment success rate is sufficient (typically greater than 30 percent), and if the side effects aren't severe or can somehow be mitigated, the advisory panel typically recommends approval.38 The company then prepares a carefully worded "insert" placed in each drug package that details how, by whom, and to whom the drug should be administered; what fraction of diagnosed patients receiving the drug can be expected to respond to the therapy; and what portion can be expected to experience side effects.

The four-stage clinical trials process inherently assumes that all patients with the same symptoms have the disease in question—an assumption that molecular biology has shown is often false, as we discussed in Chapter 2. When the designers of a clinical trial assume that the diagnosis has been made accurately and that everyone in the trial has the same disease, the trial is essentially framed as a test to see whether the drug helps patients or not. The fact that some portion of the patients do not respond is treated as probabilistic noise from which statistically significant signals of efficacy must be isolated. As a result, little is learned from the trial beyond the probabilistic profile of side effects and the proportion of patients for whom the therapy is effective. In other words, most clinical trials, by design, keep therapy safely within the realm of intuitive medicine.

To accelerate the movement of more diseases toward precision medicine and its intrinsic improvements in affordability and quality, the pharmaceutical industry and its regulators need to begin framing clinical trials as an interwoven part of the research process, rather than simply as "tests" that occur at the end of the process. When a portion of patients respond to a therapy while others with the same symptom do not, it is evidence that there's more going on than meets the eye. Either there are multiple diseases sharing that symptom—and the drug being tested happened to be effective in treating at least one of those underlying diseases—or there are genetically based differences in the way patients with the same disease respond to the therapy—or both. This should trigger molecular- and genetic-level studies to explore what is different about those who respond, versus those who don't. Drugmakers can then develop biomarkers to identify the factors critical to disease-patient interaction and help guide therapeutic decision making.39

Reframing clinical trials as "research trials" in this way could greatly assist those who are working to precisely diagnose specific diseases that today only fall under broad umbrellas of commonly shared symptoms. These trials must become part and parcel of the process of drug discovery and development. The development of diagnostics and therapeutics must be skillfully interwoven with these research trials in new ways. The appendix to this chapter provides some preliminary guesses about how this process might work.

Companies that outsource these activities will simply be unable to play in this league. In contrast, we expect that companies whose core competence is first to extract precision diagnostic biomarkers out of research trials, and then to couple them with therapeutics that will be predictably effective, will prosper. They will continue to build their businesses forward from that core, disruptively taking on more and more value-added services from their customers, who are the major pharmaceutical companies—just as ASUSTeK has with Dell. Ultimately they will take on the marketing of their products because—as we'll show at the end of this chapter—the very definition of the market for many drugs will have completely changed as well.

Armies of tort lawyers in America circulate among patients receiving approved drugs, hoping to find one who experiences a side effect that was not presaged in the insert. They then file a barrage of costly lawsuits against the drugmaker. These potential costs have pressured the drugmakers and their regulators to expand the scope and prolong the duration of Phase III trials, in order to surface as many potential problems as possible so that dangerous drugs can be kept from the market and protective language can be included on the insert. The scale of these clinical trials is driving drug development costs toward $1 billion and beyond.40 This in turn has driven many of yesterday's pharmaceutical companies to merge, creating mammoth organizations with the resources to finance these trials.

Initially, transforming clinical trials into research trials won't save money because precise diagnosis won't be possible for most classes of disease—meaning that for some time, people with different diseases will continue to be enrolled in most trials.41 Indeed, there may actually be a period of increased costs as diagnostics and pharmacogenomics come on board. This is due in part to the advent of new genetic targets. In the past, by the time pharmaceutical companies started developing a drug against a particular target, there were several dozen publications about that target—how it worked, what it did, etc. After diagnostics and drugs for those well-studied targets had been developed, however, by the early 2000s the average number of publications per genomic target had dropped to eight. To the extent that there is a higher failure rate of more novel targets, it could cause genomic-based drugs initially to become more expensive to develop, rather than less. This lends impetus to projects that develop "me too" products out of existing, well-understood targets, as they are much less risky.42

As pharmacogenomics leads us further toward precision medicine, however, the scope, duration, and cost of many clinical trials will drop significantly. When we can precisely diagnose a disease, every patient enrolled in a trial will have the same disease. With diagnostic ambiguity removed, most drugs will be shown more conclusively to work or not work, in less time, and in smaller trials.43 This will mean that the scale advantages huge pharmaceutical companies enjoy today in financing clinical trials will be rendered less relevant in the future—the playing field will be more level for large and small companies alike. We emphasize again that this will happen not in one fell swoop, but disease by disease, research trial by research trial.

For example, instead of including patients diagnosed as having "breast cancer" in its trial for the drug Herceptin, Genentech used the HER2/neu test to include in its trial only those whose tumors could be characterized by an overexpression of the HER2 protein. Genentech enrolled only 470 patients in the trial, compared to an estimated 2,200 that would have been required in a typical cancer trial. It was able to reduce the duration of the trial from the usual five to 10 years to two. It pulled in an additional $2.5 billion in accelerated income by getting to market earlier. And 120,000 patients were able to get access to this therapy who otherwise would have been denied it while a typically structured clinical trial dragged on and on.44 It is hard to conclude that the costs of clinical trials will continue to increase monotonically. Despite the winding and bumpy road, costs ultimately will trend downward.

So how should today's leading pharmaceutical companies deal with these changes? One option, of course, is to argue that dis-integration and a shift in where attractive money can be made won't happen. But the reason we predict that they will indeed happen is because the causal mechanism is the rational pursuit of profit. This pattern already has played itself out in dozens of industries, and in fact already is under way in earnest in pharmaceuticals. The other option—if we were managing one of the leading drug companies—is to own the best company that is operating at the core of future diagnostics technologies, but manage it separately so it can provide these services for many of the industry leaders, not just our own company.

The challenges facing the pharmaceutical industry that we've described to this point are indeed formidable. But we haven't finished chronicling the changes in store for pharmaceutical companies. As we'll see next, their markets will fragment. Opportunities for developing blockbuster drugs that find a huge market by targeting symptomatically defined diseases will diminish under the attack of precision medicine. New types of blockbuster drugs will emerge, but the market for these products will cut across medical specialties—fundamentally changing the value of the sales prowess of today's companies.

The pursuit of profit is creating another disruptive headache for major pharmaceutical companies, beyond those described above. Big companies need big markets in order to grow. It is hard for them to allocate resources toward products that target small markets, because not one of them brings the promise of sufficient revenues to keep the top line of a global giant growing. Yet the market for pharmaceutical products will fragment in the future.

Despite a combined R&D budget nearly double that of the National Institutes of Health, the pharmaceutical industry faces troubling data about its recent innovation track record (summarized in Table 8.1). Pharmaceutical companies far outspend all other industries in R&D. Spending has soared from $2 billion in 1980 and $8.4 billion in 1990, to $55.2 billion in 2006; yet the industry has been introducing fewer successful drugs into the market. With spending going up and results going down, the cost per new drug is skyrocketing. And to make matters worse, of those drugs approved for sale over this period, 75 percent could be classed as "me too" products: only a quarter of them offered real improvement over existing products.45 Why is this happening?

Table 8.1 Trends in R&D Costs46

Year | Number of New Molecular Entities approved by FDA1 | Number of NME's Given Priority Review2 | R&D Spending by PhRMA Members ($ billions) | Cost per successful drug ($ millions in Year 2000 Dollars) |

2006 | 18 | 6 | 43.4 | $1500* |

2005 | 18 | 13 | 39.9 | $1300* |

2004 | 31 | 17 | 37.0 | $1200* |

2000 | 27 | 9 | 26.0 | $800 |

1990 | 23 | 12 | 8.4 | $300 |

1980 | 12 | 2.0 | $150 |

*Denotes authors' projections; **priority review process did not exist

1Does not include Biologic License Application approvals.

2"Priority Review" by the FDA is reserved for new molecular entities that offer significant improvement over existing products in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of a disease. Standard Review is offered to drugs which possess therapeutic qualities similar to those of one or more existing drugs.

The lack of innovative success in the face of such increased spending is not due to the exhaustion of science and technology that typically characterizes the end stage of a technology curve.47 With modern technology and equipment, scientists have never been as capable of developing new molecules as they are today. More likely, the problem resides in the resource allocation process, in the expectations derived from a long history of success and industry growth.48 Recently, pharmaceutical companies have primarily grown via mergers—with at least 20 involving targets valued at $2 billion and higher between 1994 and 2004.49 The common rationale for these mergers was typically to build up the product pipeline by absorbing existing products, amass the scale required to increase the discovery of new compounds, and fund the cost of their clinical trials. While these firms indeed beefed up their scale and scope, they also raised the threshold for the market size a particular drug needs to create in order to be "interesting" enough to merit aggressive funding in the resource allocation process.

Here's a way to visualize how this is happening: A company's share price represents in some way the discounted present value of a future stream of cash flows that investors foresee. If something causes investors to expect that a company's cash flow will grow more slowly than they previously thought, the mathematics of discounting will cause its share price to fall to the point where the new price represents the discounted present value of the newly foreseen flow of cash. As a result, good managers feel compelled to grow—and more specifically, to grow at a constant or increasing rate—in order to maintain or grow their company's share price. If investors expect a company with $1 billion in revenues to grow 10 percent annually, its managers need to find $100 million in new product revenues the next year. The rub is, if that company achieves $50 billion in revenues and still hopes to grow by 10 percent, it must now somehow produce $5 billion in new product revenues the next year. The bittersweet reward of success is that the larger and more successful a company becomes, it actually loses its ability to prioritize new products whose markets might be small at the outset. A market that at one point represented an exciting growth opportunity might not be big enough later on to attract the resources required for development.

It wasn't too many years ago that most pharmaceutical companies considered a $100 million-a-year drug an exciting growth opportunity. As they grew, however, $100 million opportunities lost their luster—and $1 billion-a-year drugs defined "block-buster" status. Today, the leading companies are so large that even billion-dollar drugs don't solve their growth problem. Huge product markets are like heroin to executives of these companies. In the end, products with small markets or inadequate reimbursement get ignored, while "me too" products that can be developed at lower cost for broader markets hold the most appeal. It is for this reason that we have six statins available, but only two manufacturers willing to supply the entire nation's flu vaccines.50

The danger with the drugmakers' addiction to large markets is that most of today's blockbuster product markets are comprised of drugs targeting broad, symptomatically defined diseases. For example, Lilly's Prozac and Zyprexa achieved blockbuster status by targeting depression and schizophrenia, respectively. We suspect we'll learn in the coming years, however, that both of these major diseases are in fact families of many different disorders that share common signs and symptoms. And we might learn as well that Prozac and Zyprexa are predictably effective in treating just one (or a few) of these diseases.

The same can be said for lipid-lowering blockbusters such as Lipitor. We'll likely discover that elevated levels of blood cholesterol is a "symptom"51 shared by several different diseases—and that Lipitor is effective only in treating one or a few of these diseases. We'll learn that many of the patients taking these medications had a disease for which these drugs are not particularly effective. The advent of precision medicine will fragment most of these markets—there will be many more diseases, many more products, and significantly lower revenues per product. These markets will be very visible and very exciting to smaller drug companies. But to the mega-merged pharmaceutical giants, these markets simply won't solve their pressing needs for huge chunks of instant revenue growth. Their business models just aren't made for developing and selling products to smaller markets.

How, you ask, can companies afford even to roll the dice in a game where the cost of developing a single new drug approaches $1 billion? The answer is that while today's drug companies are spending this amount per drug developed, it doesn't cost $1 billion to launch a successful product. It is trial and error that are expensive. A significant portion of that cost is spent sifting through drugs whose markets are too small, in order to find those that are large. A lot of innovation gets tossed aside in that filtering process. Another portion is spent on testing the drugs in clinical trials that ultimately prove to be ineffective for a large majority of patients with the symptomatically defined disease. As we move toward the realm of precision medicine, we will find that development of successful new products will cost substantially less than it does today.

In the face of this fragmentation of pharmaceutical markets, new blockbusters will arise because of diagnostic precision, rather than its absence. We've previously mentioned one example of this—the case of Elan Pharmaceutical's Tysabri (natalizumab). Elan's scientists discovered that multiple sclerosis is but one of several symptomatic expressions that result from a common underlying disease pathway. In the case of multiple sclerosis, this molecular pathway promotes excessive entry of white blood cells into the central nervous system, leading to inflammation and nerve cell damage. Interestingly, the same molecular pathway was found in other patients, but the disease manifested in them as an inflammatory bowel disorder called Crohn's disease. It's quite possible that the same underlying disease might be manifesting itself with symptoms now identified as ulcerative colitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Another example of this new type of blockbuster is the Novartis drug Gleevec, which is used in treating not just a particular type of leukemia called chronic myeloid leukemia, but gastrointestinal stromal tumors as well. Both of these tumors propagate through similar molecular pathways.

Because it alleviates the underlying molecular disease, Tysabri is a potential blockbuster—a treatment for all these various symptomatic expressions of the underlying disease. Frustratingly, of course, the FDA still defines the diseases by symptom, requiring Elan to conduct separate clinical trials for each. However, as scientific research continues to push toward precision medicine, it is still quite possible to find blockbusters of this new genre.

Such new blockbusters already appear to be emerging in cancer treatment. In a provocative presentation at an Innosight Institute conference in 2008, Dr. Mara Aspinall asserted that if you are diagnosed with cancer, you should never seek treatment at a hospital that is structured according to body organs—with departmental specialties in breast cancer, bone cancer, brain cancer, and so on. The reason is that, by definition, the institution will have diagnosed your disease incorrectly. Whether you respond to the therapy they offer will truly be a matter of chance. The cancer institute you can trust, she asserted, will be structured around the different molecular pathways by which tumors have been found to propagate. While there will no longer be blockbuster drugs to fight leukemia (which has been shown to comprise 51 different types of cancers), there will be blockbusters (or "niche busters") that fight diseases defined by molecular pathway rather than geographic location.

We have replicated Dr. Aspinall's illustration of this contrast in Figure 8.3. As suggested in the diagram of the hospital on the left, in the past, when we classified patients and their diseases by location, we were applying the same therapy across multiple diseases. In the future, as suggested by the hospital on the right that classifies patients by the type of tumor growing within them, we will be able to treat specific diseases that arise in multiple locations in the body with a predictably effective therapy for each of them.

What does this mean for major drug companies like Pfizer and GSK? In all probability, they are too large for today's competitive conditions, and much too large for the fragmented product markets they will confront in 10 years. Aside from divesting themselves of the companies they acquired to become so large, another possibility is for them to structure themselves internally as Johnson & Johnson has. J&J's $61 billion in revenues comes from over 250 operating companies, each of which has its own management board.52 Some of these, like Ortho-McNeil, Janssen, and Centocor, have themselves become massive multi-billion-dollar enterprises, while others are much smaller. The guiding principle that today's huge pharmaceutical companies need to follow is that the growth markets of tomorrow will primarily be small ones. Corporations that are comprised of many small companies will see these opportunities with much greater acuity than a large monolithic company ever could.

Fortunately, there are a few early indications that at least some of the major pharmaceutical companies—particularly Novartis—are seeing this future quite clearly. They have chosen to segment their R&D into divisions based on molecular pathways, rather than by anatomically defined organ system or symptomatically defined disease. One benefit to matching drug development to properly defined diseases is the likely reduction in the number of patients susceptible to being harmed by treatment. This not only reduces potential liability from patient lawsuits, but can also lead to the rescue of dozens of drugs that were denied FDA approval because they proved effective on too small a portion of the population, or had been pulled from the market due to previously unpredictable side effects. The clinical trials involving Iressa (gefitinib) and Herceptin (trastuzumab) have already demonstrated the value of molecular testing in identifying the value of drugs that would otherwise have failed to garner FDA approval because they were effective in only a minority of patients.

FIGURE 8.3 The definition of disease drives the structure of the organizations that treat the disease

Historically, "detailing" was the primary sales mechanism for drugs. Pharmaceutical company salespeople called on physicians to give them the detail they needed about new drugs they could prescribe for their patients. As shown in Figure 8.4, drug detailing historically accounted for more than 70 percent of drug companies' total selling and marketing expenses. It constituted a major expense investment not just for the pharmaceutical companies, but also entailed a major opportunity cost for the physicians. Both sides, however, found it in their interest to spend this time together, explaining and learning about drugs that were available to prescribe for patients' problems. Strong relationships of mutual trust often developed between physicians and those that detailed drugs to them. This, in turn, created yet another barrier against the entry of new companies into the pharmaceutical business. Creating a sales force with the requisite reach represented a huge investment that few companies had the resources to muster.

The heavy fixed cost of a detailing sales force also steepened the scale economics in the industry by creating a strong drive for volume—driving the thirst for blockbuster drugs and for acquisitions that brought the ability to push more volume through the sales force. Detailing doesn't work well anymore, however—and that's a big problem, because in many respects companies' profit models and competitive advantages are structured around the reach and relationships their direct sales forces have had with doctors. Doctors today are under such pressure to see more patients that they simply don't have the time to spend with drug company salespeople. And doctors are much less dependent upon detailers to learn about drugs: there are alternatives. The Internet enables physicians to search for the right drug, and to refresh their knowledge of its side effect profile and possible interactions with other drugs, even while the patient is in the office.

In reaction to the obsolescence of their sales model, the pharmaceutical firms have increasingly aimed their marketing efforts at patients, helping them to "self-diagnose" and then "pull" the drugs through their physicians. Since the FDA began allowing in August 1997, brand-specific direct-to-consumer (DTC) television advertising has been an increasingly important segment of the marketing budget. As we've shown in Figure 8.4, DTC had grown to account for over one-third of drug companies' total marketing and sales budgets by 2005.53 DTC spending was $4.2 billion in 2005, compared to about $1 billion in 1996, outpacing the growth in total promotional spending.54

Almost every disruption involves a story like this. When products are complicated and expensive, they typically must be sold by expert, company-employed salespeople who sell to expert users on the customer side. Hence, for example, mainframe and minicomputers were sold directly to users. The reach and reputation of IBM's sales organization was a forceful presence no competitor could beat. But the personal computer couldn't be sold that way. They had to be marketed direct to end users, who then pulled the products through the distribution channels. The marketing methods for photocopiers, mutual funds, customer relationship management software, cameras, and many others followed a similar pattern. Instead of relying upon company salespeople to push their products into the market, the economics of disruption changed the marketing model to one of mass marketing to customers, who then pulled the products through the distribution and retail channels.

In the first stages of disruption of the sales model, there still are fairly steep scale economies in sales and distribution. Direct-to-consumer television advertising and getting space on retailers' shelves requires scale, scope, and capital. In many of these instances, however, the Internet has flattened those scale barriers so that small companies can advertise with broad reach, and customers can find products without needing to go to brick-and-mortar retailers.

For patient safety advocates and for those who worry about unwarranted consumption of health-care products and services, DTC advertising of drugs is one of the most worrisome dimensions of the disruption of health care. Here's our sense as to why this change is worrisome. Recall the effect that capitation had when it was imposed in the system of independent practitioners and providers. When responsibility for constraining spending was placed upon the shoulders of primary care physicians as gate-keepers, it imposed upon them the role of saying no to patients' requests for access to specialists and for second opinions when those were not warranted. Doctors complained that saying no strained their relationship with patients. Direct-to-consumer advertising again imposes upon physicians the responsibility of saying no in those occasions when patients haven't self-diagnosed correctly—and again puts doctors in an uncomfortable and unaccustomed role. It is unpopular because life was much simpler when patients' abilities to know what to ask for were so limited that they simply accepted what doctors offered.

FIGURE 8.4 Changes in the mix of sales and marketing spending by pharmaceutical companies55

In making these assertions, we are not being critical of physicians and the negative reaction many of them have to DTC advertising. Every parent has experienced the same feelings. When money is not a constraint, it is infinitely easier (in the short term) to accede to our children's requests than to deny them. Similarly, when money is not a constraint (as is the case under fee-for-service), life is a lot easier for physicians when they do not have to say no.

A better way to address the change of marketing direct to consumers is simply to accept that this transition in marketing is here to stay in health care—and in the end it will be a good thing. When an industry is in the realm of intuition—whether it is intuitive computing, construction, printing, or investing—experts tend to sell to experts. But as things evolve toward the realms of pattern-recognition and then rules-based decision making, we transition toward selling to the end user. Direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs may have jumped the gun in circumstances where the disease in question hasn't moved toward pattern-recognition or rules-based diagnosis and therapy. But our approach to dealing with this problem should be to give consumers ever more accurate tools for self-diagnosis, and transition toward payments systems such as health savings accounts, which create incentives not to consume what is not needed. And the doctors who need to write these prescriptions will, unfortunately, need to get comfortable with saying no on occasion.

At present, the disruption of the selling system for pharmaceuticals is still in its first phase, in that it is expensive and scale-intensive to advertise on national television and in national print media. This creates barriers for smaller entrants. But the use of online diagnostic tools will become more prevalent as primary care physicians (PCPs) disrupt specialists, as nurse practitioners disrupt PCPs, and as self-diagnosis disrupts professional care. We expect those sites to become the locus for DTC advertising of drugs in the future, again flattening the barriers against entry that have historically been in place.

The generic drug sector has been depicted as both savior and wrongdoer when it comes to the pharmaceutical industry's uncertain future. By simply waiting for drugs to go off patent before reverse-engineering their own bioequivalent molecules, generic manufacturers don't incur the significant clinical trial costs that inflate the expensive drug development figures in Table 8.1. They can often piggyback onto the extensive, decade-long marketing efforts of the branded pharmaceutical companies.56 Throw in allegations of bribing and unethical conduct,57 and it's not surprising that the generic manufacturers are often likened to vultures, who exist only as long as they are able to feed on the unwanted remains of once viable products.

On the other hand, competition among generic manufacturers is particularly intense, as the loss of patent protection essentially turns the drug molecule into a commodity that any drugmaker in the world can try to produce. This competition, particularly from overseas companies like Teva, Dr. Reddy's, and Ranbaxy (recently acquired by Daiichi Sankyo), drives prices down significantly. And when patients, insurers, and payers alike see four dollar prescriptions available from Wal-Mart,58 it's not hard to understand why they expect generic drugs to help bring down some of the costs of a much maligned pharmaceutical industry.

In cooperation with health plans and employers, many hospitals have developed "tiered formularies," which list not just the drugs within each category that physicians can prescribe, but rank order them by tier. The generic equivalent, if available, always is the first tier therapy. If it isn't appropriate or isn't available, then the formulary shows the next allowable choice, and so on.

We would agree that generic manufacturers can begin to disrupt the larger, branded manufacturers—but not for any of the reasons listed above. If generic manufacturers were to begin competing directly against branded manufacturers by initiating their own R&D for new molecules, the technological enabler—the drug molecule—would basically be the same for both. The question therefore becomes whether generic manufacturers have built or are capable of building a disruptive business model with which to carry out the necessary R&D and postdevelopment marketing to compete effectively.

However, until recently there hasn't been a pressing need to do this. The health-care reimbursement system in the United States has effectively ensconced a cost-plus system of pricing that guarantees a sufficient amount of revenue to cover the R&D and marketing costs of branded pharmaceutical companies. It is a practice reminiscent of some of the most egregious U.S. Department of Defense contracts: when prices can be negotiated so costs are always recouped, why would anyone care what things should cost? This pricing system even balances the lost revenues from foreign markets, where branded drugs are often sold at far lower prices than in the United States. Prices are so much lower elsewhere that many intrepid entrepreneurs and lawmakers are trying to reimport branded drugs. But this price differential exists not because other countries and single-payer systems are so much better at negotiating prices; it exists because cost-plus reimbursement has inadvertently made the United States the primary financier for the world's pharmaceutical R&D.

So what's the true cost of drug development? Generic manufacturers, which did not arise in an environment of cost-plus contracts but rather from the ashes of vigorous competition and low pricing, would likely have developed business models that come much closer to reflecting real, rational costs. But comparing the business models of generic and branded manufacturers has been difficult in the past. Generic manufacturers had rarely forayed into developing new molecules, and therefore were offering a very different value proposition. They were quite content to continue earning acceptable profits based on their more modest R&D and marketing expenses, without having to place the risky bets of their larger brethren.

For years the administered pricing scheme created a détente, with branded and generic manufacturers standing on either side of a battle line defined by a patent expiration date. But frustrated with the slow pipeline of drugs from branded manufacturers upon which they are dependent, a few generic manufacturers like Teva began to venture into drug development for themselves. Already, 20 percent of Teva's revenues are derived from patented products. R&D and marketing costs of new molecules developed by generic manufacturers in India and Israel seem to be 30 to 40 percent below the average drug development costs of branded manufacturers in the United States and Europe.59 This will fit quite nicely into a disruptive value network of cost-conscious patients, providers, insurers, and payers looking for more four dollar drugs. Ultimately, much like the situation with IBM and Digital Equipment in the era of microprocessors, both generic and branded manufacturers will have access to the same technological enablers. But disruption prevails when the technological enabler is implanted into a business model that can make money at lower margins, while still delivering the quality its customers demand.

We foresee significant redirections in the seas ahead through which the pharmaceutical industry's chief navigators will need to steer their companies. For reasons of technological and commercial interdependence, vertical integration typically plays a key role in the early growth of most industries, and in the rise to dominance by their leading companies. The processes of disruption then reverse the factors that had necessitated integration, causing industries to dis-integrate—to become populated by a horizontally stratified value network of specialist companies. The pharmaceutical industry, long led by large, powerfully integrated companies, is now moving inexorably toward dis-integration.

The driver of dis-integration is outsourcing, which results in "supply chain disruption." The industry's leading integrated competitors, in the pursuit of greater profitability, begin by outsourcing their most peripheral, lowest value-adding activities to lower-cost suppliers. With this done, the next step toward enhancing profitability is to outsource the lowest value-adding activity of those that remain; and so on. The companies that receive these outsourcing contracts have the opposite motivations. In the pursuit of greater profitability, they are eager to take on the progressively higher value-adding activities their customers are eager to shed. Little by little the industry-leading companies do less and less, and their suppliers do more and more—until the leaders have liquidated their business models. This process is well under way in pharmaceuticals. Companies that initially specialized as recipients of outsourcing contracts for drug discovery and development, contract manufacturing, and managing clinical trials, have expanded their scope to encompass most of the industry's value chain.

Once dis-integration has occurred, the stage in the value chain where attractive profits can be earned shifts. The ability to make attractive profits typically centers at the stage in an industry's value chain whose technology determines overall system performance. As disruption occurs, this stage typically is the enabling technology inside the product.

In pharmaceuticals, this suggests that in the future, activities that link precise diagnostics with predictably effective therapeutics will become the center of industry profitability. At the core of this will be the management of clinical trials—which need to be framed as research trials, rather than end-of-the-process tests of whether drugs work. The development of diagnostics and therapeutics will be intertwined through these research trials. For reasons that seem (to them) to be perfectly rational and profit-maximizing, most leading pharmaceutical companies are walking away from these activities, which will coalesce as the critical core competencies of tomorrow. The leaders would be wise to reverse course.

The market for drugs will fragment. Instead of being dominated by multi-billion-dollar blockbuster products, pharmaceutical companies' revenue streams will generally come from a much wider variety of products, with much lower revenues per product. The cost structure and investment models of today's mega-merged global pharmaceutical companies, which have become addicted to blockbuster drugs, will therefore need to be unwound and rewritten.

New types of blockbuster drugs will emerge, but these will require a significant restructuring of these companies' sales and marketing capabilities. As we learn what these diseases are, we'll realize that most companies' sales forces are organized incorrectly, because medical specialties themselves have been defined incorrectly.