Each disruption is composed of three enabling building blocks: a technology, a business model, and a disruptive value network. While Chapter 1 deals with business models, this chapter focuses on the technological enablers that form the backbone of disruptive business models. These technological or methodological enablers allow the basic problems in an industry to be addressed on smaller scale, with lower costs, and with less human skill than historically was needed. These technologies sometimes come from years of work in corporate research and development (R&D) labs. Others are licensed or bought, and, on occasion, technology can be repurposed from an entirely different industry.

The health-care industry is awash with new technologies—but the inherent nature of most is to sustain the current way of practicing medicine. However, the technologies that enable precise diagnosis and, subsequently, predictably effective therapy are those that have the potential to transform health care through disruption. We begin this chapter with a general review of what makes a technology disruptive and how that technology converts complex intuition into rules-based tasks. We then introduce a three-stage framework for characterizing the state of technology in the treatment of various diseases. This framework asserts that the treatment of most diseases initially is in the realm of experimentation based on intuition. Care then transitions into the realm of probabilistic or empirical medicine; and ultimately it becomes rules-based precision medicine. After explaining this framework, we then review the history of infectious diseases to show how technological enablers based on precise diagnosis caused care to pass through these stages. Moving to the present, we show how similar transitions are now afoot in the care of diabetes, breast cancer, and AIDS. Next, we redefine the concept of personalized medicine and show how information technology is enabling facilitated networks to deliver true personalization. Finally, we sketch out a preliminary map of the state of knowledge of a range of diseases, allowing us to project what technological breakthroughs will enable the further disruption of today's health-care business models.1

There is a clear pattern in the long and arduous process by which an industry eventually transforms the body of knowledge upon which it is built from an art into a science. In the earliest stages of most industries, the extent of understanding is little more than an assortment of observations collected over many generations. With so many unknowns, the work to be done is complex and intuitive, and the outcomes are relatively unpredictable. Only skilled experts are able to cobble together adequate solutions, and their work proceeds through intuitive trial-and-error experimentation. This type of problem-solving process can be costly and time-consuming, but there is little alternative when the state of knowledge is still in its infancy.

Over time, however, patterns emerge from these intuitive experiments. Defining these patterns that correlate actions with the outcomes of interest makes it much easier to teach people how to solve the problems. There is as yet no cookbook that can guarantee success every time, but the scientists can often state the probability of an outcome, given the actions that have been taken. Ultimately these patterns of correlation are supplanted with an understanding of causality, which makes the result of given actions highly predictable. Work that was once intuitive and complex becomes routine, and specific rules are eventually developed to handle the steps in the process. Abilities that previously resided in the intuition of a select group of experts ultimately become so explicitly teachable that rules-based work can be performed by people with much less experience and training. Problem solving becomes focused on root cause mechanisms, replacing activities that were grounded in conjecture and correlation.

The term "technology" that we use here might refer to a new piece of machinery, a new production process, a mathematical equation, or a body of understanding about a molecular pathway. However, at the heart of this evolution of work is the conversion of complex, intuitive processes into simple, rules-based work, and the handoff of this work from expensive, highly trained experts to less costly technicians. The cases that follow illustrate how disruptive technologies enable this transformation and eventually lead to the emergence of successful business models that are able to capture the advantages of rules-based work.2

Founded in 1802 as a manufacturer of gunpowder, DuPont operated several industrial laboratories to expand its understanding and capabilities in materials science. Building on the discovery of synthetic rubber, DuPont's scientists conducted research on polymers at the company's Experimental Station through the 1930s. DuPont evaluated over 100 different polyamides before finding new fibers that were adequately stable for commercial development and production. This resulted in the invention of the world's first synthetic textile fiber, nylon, in 1935. The success of that discovery led to further polymer research that ultimately yielded DuPont's acrylic fiber in 1944 and Dacron polyester fiber in 1946. The work that led to these inventions was a classically intuitive, trial-and-error process of problem solving. During those decades, there were only a limited number of scientists in the world with sufficient expertise to push the work forward, and DuPont employed most of them. As a result, DuPont dominated the synthetic fibers industry.

As DuPont's scientists continued to practice their craft, however, and as the fields of quantum mechanics and molecular physics became better understood and applied, the cause-and-effect relationship between a polymer's molecular structure and the fiber's physical properties became more clearly understood. Scientists codified which arrangements of molecules and specific chemical bonds defined a polymer's strength, melting point, and stiffness. This understanding of polymer chemistry ultimately enabled scientists to reliably predict the physical properties of a fiber before it was created—enabling the design and production of application-specific fibers with less trial-and-error experimentation than ever before. The development of DuPont's Nomex, a heat-resistant fiber that could serve as a fire retardant, and Kevlar, a fiber five times stronger than steel, both resulted from this progress in polymer science.3

Today, engineers at DuPont and in many other companies rely on computer modeling to assist in the creation of novel compounds with the exact properties that are desired. To a growing extent, success requires at least as much, and perhaps more, familiarity with the software than the intuition or knowledge of physics and chemistry that those first scientists had drawn upon at DuPont's Experimental Station. In other words, the intuition and expertise of DuPont's engineers ultimately were captured in software that has diffused around the world, enabling many more engineers to discover new synthetic materials more rapidly and efficiently than could have been imagined 50 years before.

The impact of this progress on our well-being is simply extraordinary. In the 1950s, wood, metal, paper, rubber, stone, and ceramics (including glass and cement) were the primary materials available for building and covering things. Today, our lives are made incredibly efficient and comfortable by materials whose durability, flexibility, strength, appearance, and cost were inconceivable a generation ago. This enrichment did not come from replicating the costly expertise of DuPont's scientists, however. It came from scientific progress that commoditized their expertise, thereby enabling many more scientists and technicians to continue building on their initial work.

A second example of how scientific and technological progress can transform the fundamental nature of an industry's core technological problem is the process of designing automobiles. BMW triumphantly announced several years ago that its automobile models could now be designed so realistically on computers that its engineers could crash-test the cars virtually, on an engineering workstation.4 This enables BMW's engineers to optimize their designs for safety before a physical model is even made. That's the good news for BMW. It is much less expensive to design safe, attractive, high-performance cars on a computer than to build and crash physical prototypes. The bad news is that once the algorithms of design have been codified so completely that a computer can guide much of this work, such technology enables a lot of people—not just BMW engineers—to design comparable cars.

Made possible by advances in technology and science, the migration of problem solving from a small group of experts to a larger population of less-expensive providers who simply have to follow the rules is a widespread foundational phenomenon that underlies the transformation of industries ranging from animation to architecture to aviation; and from telecommunications to taxes.

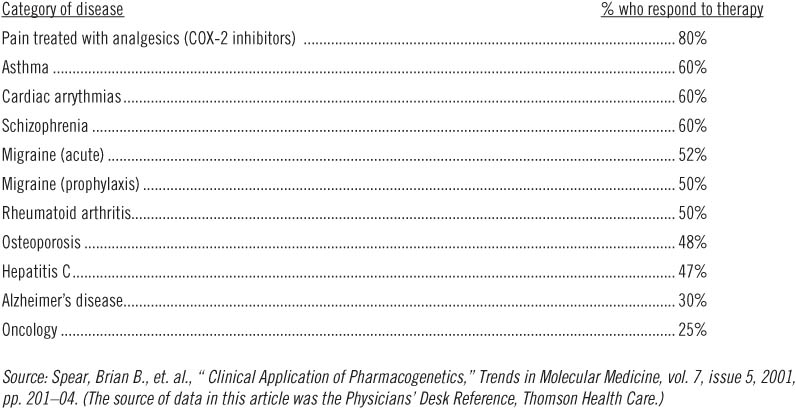

In spite of all of the money and effort devoted to biomedical research in today's academic medical institutions, pharmaceutical companies, and biotechnology firms, the outcomes of many commonly prescribed therapies are not very satisfying. For example, over 60 percent of all patients being treated for Type II diabetes have blood sugars that exceed the recommended level, putting them at significantly elevated risk of developing heart disease, kidney failure, blindness, and other long-term complications of uncontrolled diabetes.5 Despite the use of medications, the blood pressure in as many as 58 percent of patients being treated for hypertension (depending upon which study is consulted) does not conform to the recommended target of below 140/90.6 Even though billions of dollars are spent to purchase lipid-lowering drugs, only 17 percent of patients with heart disease—those most in need of good control—ever reach the goals for cholesterol management established by national guidelines.7 Among patients diagnosed with depression, only half report a 50 percent improvement in symptoms after using anti-depressant medications, and of those, 10 percent relapse within six months. What is more baffling is that 32 percent of patients who received a placebo also experienced a 50 percent improvement in symptoms.8 Table 2.1 chronicles the story more completely.

The statistics in Table 2.1 are not the results of poor patient compliance or variations in clinical care; all these patients were enrolled in clinical trials where medication use was closely monitored and where the physicians conducting the studies treated patients according to fixed protocols established by the clinical trial investigators.

Why, despite the billions being spent, does medical science still seem at best to be an art? A significant reason lies in our inability to precisely diagnose disorders such as those listed above based on their actual root causes, which may be genetic, infectious, or quite possibly to the result of something still unknown to medical science. But it is only when precise diagnosis is possible that consistently effective therapy is possible. Until this happens, many of those afflicted with disorders such as these can be treated only with the trial-and-error guesswork that pervades clinical decision making today.

Table 2.1

Patient response rates to a major drug in selected categories of therapy

It turns out that the human body has a very limited vocabulary from which it can draw when it needs to declare the presence of disease. And to a confusing degree, the body often inarticulately "slurs" its expressions that disease is afoot. Fever, for example, is one of the "words" through which the body declares that something inside isn't quite right. The fever isn't the disease, of course. It is a symptomatic manifestation of a variety of possible underlying diseases, which could range from ear infections to Hodgkin's lymphoma. Medications that ameliorate the fever don't cure the disease. And a therapy that addresses one of the diseases whose symptom is a fever (as ampicillin can cure an ear infection) may not adequately cure many of the other diseases that also happen to declare their presence with a fever.

As scientists work to decipher the body's limited vocabulary, they are teaching us that many of the things we thought were diseases actually are not. They're symptoms. For example, we have learned that hypertension is like a fever—it is a symptomatic expression of a number of distinctly different diseases. There are many more diseases than the number of physical symptoms that are available, so the diseases end up having to share symptoms. One reason why a therapy that effectively reduces the blood pressure of one patient is ineffective in another may be that they have different diseases that share the same symptom. Another reason, which we discuss toward the end of the chapter, may be that they are genetically different in their physiologic metabolism of the drug itself.9 When we cannot properly diagnose the underlying disease or fully understand the context in which the patient may or may not be able to respond to treatment, the sorts of rules-based processes that emerged for synthetic fibers and computers to this point have proved impossible in medicine. As a result, effective care generally could only be provided through the intuition and experience of highly trained (and expensive) caregivers—medicine's equivalent of the pioneering scientists and engineers at DuPont, BMW, and in IBM's mainframe computer business.

In this book, we define intuitive medicine as care for conditions that can be diagnosed only by their symptoms and only treated with therapies whose efficacy is uncertain. By its very nature, intuitive medicine depends upon the skill and judgment of capable but costly physicians. Not surprisingly, that skill and judgment is heavily influenced by where and when practitioners were trained, where they practice, the relative supply of human and physical capital, how caregivers are paid, and how updated they are with the latest medical advancements.10, 11

At the other end of the spectrum, we define precision medicine as the provision of care for diseases that can be precisely diagnosed, whose causes are understood, and which consequently can be treated with rules-based therapies that are predictably effective. The science of precisely diagnosing diseases by the pathophysiology through which they arise and propagate does not ensure that a predictably effective therapy can be developed, of course, but it sure helps. In other words, precise diagnosis is necessary but not sufficient for treatment of a disease to be at the precision end of the spectrum.

As we show below, progress along the spectrum between intuitive and precision medicine is the primary mechanism through which technological enablers can lead the disruption of existing health-care business models.12

Intuitive and precision medicine are not binary states, of course. There is a broad domain in the middle that we term empirical medicine. The practice of empirical medicine occurs when a field has progressed into an era of "pattern recognition"—when correlations between actions and outcomes are consistent enough that results can be predicted in probabilistic terms. When we read statements like, "Reduction to normal levels occurred in 73 percent of patients who took this medication," or, "98 percent of patients whose hernias were repaired with this procedure experienced no recurrence within five years, compared to 90 percent for the other method," we're in the realm of empirical medicine. Empirical medicine enables caregivers to follow the odds, but not to guarantee the outcome.13

Scientific progress takes us along the continuum from intuitive to empirical and ultimately to precision medicine.14 In most cases, precise diagnosis must precede predictably effective therapy.15 And in order to achieve that degree of precision, technology must progress interactively on three fronts. As the following case histories illustrate, the first front is an understanding of what causes the disease; the second is the ability to detect those causal factors; and the third is the ability to treat those root causes effectively.

Infectious diseases were the first to yield to precise diagnoses. The earliest diagnostic categorization schemes for infectious diseases were based on factors such as immorality and weakness of faith, unsanitary conditions in the city, exposure to affected individuals, or contact with certain insects and animals (anthrax pneumonia was once called "wool sorters' disease"). These diagnoses were reasonable given the state of knowledge—and therapy was sometimes successful.

However, progress was finally unleashed when, by using microscopes and various staining techniques, scientists realized that people were surrounded by a sea of microorganisms, both harmless and deadly. Some of these microbes caused diseases with overlapping symptoms, but identification of the particular organism involved offered clues to the aggressiveness and spread of the disease and the patient's general prognosis. Over time, this would translate to tailored antibiotic therapy based on the species of organism and, more recently, on the molecular subtype and resistance profile of the involved strain.

Precise diagnosis enabled consistently effective therapy. This took time, as Figure 2.1 shows—Leeuwenhoek saw his first microbes in his primitive microscope 250 years before Fleming discovered penicillin.

The potential for precision medicine as a technological enabler to dramatically reduce overall health-care costs is illustrated by what has happened to the cost of treating infectious diseases. In constant dollars, the cost of diagnosing and treating these diseases has declined by about 5 percent per year since 1940—step by step, disease by disease, as scientific progress has shifted these disorders from intuitive toward precision medicine.16 Diseases like tuberculosis, diphtheria, cholera, malaria, measles, scarlet fever, typhoid, syphilis, poliomyelitis, yellow fever, smallpox, and pertussis (whooping cough) once accounted for the lion's share of health-care costs. Now they amount to a blip in the U.S. health-care budget.

FIGURE 2.1 Significant events in the history of infectious diseases

Tuberculosis: From Consumption to Cure |

Until the early twentieth century, tuberculosis was known as "consumption," so named because the disease caused its victims to waste away. Given the limited understanding of the disease, however, what was called consumption also likely referred to cases of lung cancer, pneumonia, and bronchitis, all of which could present with overlapping symptoms. Still other diseases that were once categorized as kidney failure, bone disease, or a skin disease thought to be curable by the touch of royalty ended up being tuberculous nephritis, Pott's disease, and scrofula, respectively—all manifestations of unrecognized, untreated tuberculosis. |

Long feared as one of the great microbial killers of mankind, tuberculosis itself would soon begin to fall victim to our curiosity. By the second half of the nineteenth century, there was strong suspicion that tuberculosis was an infectious disease, often spreading through crowded cities. Measures were taken to prevent public spitting, and sanitariums were established to offer fresh air, exercise, and good nutrition to the afflicted. Though the level of understanding and treatment had progressed slightly, the inability to precisely diagnose and specifically treat meant that tuberculosis continued to kill without mercy. |

By the end of the nineteenth century, two discoveries dramatically altered the landscape. In 1882, Robert Koch identified the bacteriological cause of disease, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, moving the level of understanding to the organism.17 This was soon followed by Wilhelm Roentgen's discovery of the X-ray in 1895, which enabled clinicians to examine and diagnose lung disease in far more sophisticated ways. |

In 1906, the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine offered the first form of targeted prevention, although it was imperfectly targeted since it was prepared from a related bacteria strain that infected cows. However, after years of experimentation, an arsenal of antibiotics was discovered that could successfully treat tuberculosis: streptomycin in 1944, isoniazid in 1952, and rifampin in 1963. |

However, although these antibiotics were extremely successful in treating tuberculosis initially, they too were imperfect. A disease thought to be headed toward eradication soon began to put up a fight. Multidrug-resistant strains of tuberculosis were first noted in 1970, and increasing rates of infection in the 1980s were soon found to coincide with the rising number of immunosuppressed HIV patients. Clearly, though the number of victims is no longer overwhelming, the battle against tuberculosis is not yet over, and we should be prepared to move toward even more specific and targeted weapons as time goes on. |

The result of this prolonged attack on infectious disease through diagnostic and therapeutic innovation is the dramatic decline in mortality from infectious diseases shown in Figure 2.2 (although readers should note the tremendous increase in 1918, which is discussed in endnote 16). Diseases such as cervical cancer and stomach ulcers, whose causes used to be uncertain and whose treatments were unpredictable, have also been shown to be infectious diseases. The former is now preventable through vaccination, and the latter treatable through antibiotics. More recently, scientific progress was able to rapidly shift AIDS and SARS toward the precision end of the spectrum too.18, 19

Cancer has begun to yield to a similar revolution in the precision of diagnosis and efficacy of treatment. Just as the invention of the microscope and subsequent discovery of antibiotics drove infectious diseases toward the precision end of the spectrum, a deeper understanding of molecular biology and the human genome is enabling scientists and clinicians to begin diagnosing and treating cancers based upon their molecular characteristics rather than gross anatomical observations. For example, we used to think that leukemia was a disease diagnosed by visually observing an excessive number of white blood cells. Now we know this preponderance of abnormal white blood cells, like a fever, is a vague "word" that the human body utters when one of 38 different cancers of the blood occurs (and there are likely many more yet undiscovered). Each of these specific diseases can be characterized by the molecular pathways by which the cancer propagates, and each can be detected by a pattern in which certain genes express themselves.

FIGURE 2.2 Mortality rates from infectious disease in the United States, 1900–2000

As a result, now we know why in the past a course of therapy that would cure one leukemia patient could not save the life of another: they had different diseases, and we just didn't know it. These diseases were in the realm of intuitive medicine—standardized therapy was not only inadvisable, it was impossible. However, members of this set of diseases are yielding one by one to precision medicine, as molecular diagnostics paves the way for predictably effective therapy. Gleevec (imatinib) from Novartis is such a therapy—predictably effective for one type of leukemia called chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that depends on a particular molecular pathway that can be inhibited by imatinib.20 Figure 2.3 chronicles the important milestones in the ongoing process of transforming this collection of diseases from intuitive to precision medicine.

In a similar way, we now know that breast cancer, like leukemia, is not a single disease. Rather, it denotes a geographic location in which a range of microscopically unique tumors can arise. Medical historians have discovered recorded cases of breast cancer dating back to 490 B.C. Based on its destructive and unpredictable effects, breast cancer (or almost any cancer for that matter) was viewed as a death sentence. It remains one of the most feared diseases among women today.

In 1985, scientists discovered that a specific receptor on the surface of cells, called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), was produced in excess in about 20 to 25 percent of breast tumors—suggesting to them that these tumors might be a different disease, defined by a unique molecular pathway through which those tumors propagated. In 1998, Genentech received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to market trastuzumab under the brand name Herceptin. The drug is an antibody designed to specifically halt the growth of breast cancer cells by attaching to the HER2 receptors on the surfaces of those cancer cells. The result has been a dramatic improvement in the survival rate of the patients who have that specific form of breast cancer. Herceptin is better tolerated and safer than chemotherapy or surgery since it is better able to address the disease at the molecular level. For patients who are HER2-positive, determined by specific molecular testing for the receptor or its precursor gene, Herceptin has essentially become a rules-based treatment, and the result is a vastly improved probability of survival with fewer side effects.21 Eventually, given the right tools, the treatment for HER2-positive breast cancer will increasingly move out of the hands of oncologists and into the realm of generalists.22

Links to cigarette smoking, hormone replacement therapy, and specific genes like BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 indicate many possible causes of other forms of breast cancer. These explanations to date have been incomplete, overlapping, and often confusing. As a result, the primary defense against breast cancer has been to discover it early through mass screening efforts using mammography. The need to cast such a wide net is an indication that, though science has made significant progress, there is much diagnostic uncertainty yet to resolve.

Bernadine Healy, former head of America's National Institutes of Health, summarized this progress against cancer in a reflection upon her own battle with a brain tumor: "Sifting through the genetic and molecular profiles of individual cancers has exposed a big secret that misled many treatments of the past: What seem to be identical tumors under the microscope can be markedly different where it really matters, in the genes and proteins. This is a crucial discovery, explaining for the first time why a tumor melts away under a particular therapy while another of the same type is barely touched; and why one tumor returns in a few years and yet another disappears for a lifetime."

FIGURE 2.3 History of hematological cancers

It enables, Healy continued, "a re-thinking of the traditional treatment approach, in which any and all cells with rapidly replicating DNA—malignant or not—are attacked as if they were known enemies of the body. The new era instead relies upon an army of laser-like drugs, some old, some new, and some yet to be devised, that specifically target deranged genetic pathways and swoop in for the kill, leaving the innocent bystanders intact."23

Indeed, what we have learned in recent decades is that while the body had seemed quite inarticulate when we were only able to discern what it was saying by magnifying and measuring what we could see, feel and hear, the body is delightfully articulate at the level of genetic expression.24 Over time, as scientists use molecular biology and imaging diagnostics to push one disease after another from the intuitive toward the precision end of the spectrum, the mortality rate for other diseases will decline just as it did for infectious diseases a century earlier. In fact, this has already begun for cancer. From 1995 to 2004, the overall number of deaths from the 15 deadliest cancers decreased by an average annual rate of 1.2 percent.25

The reason why investments to gain this knowledge are so important, from the point of view of efficacy and economy, is that as diagnosis and treatment become simpler and more proven, care of these diseases can be shifted from the most expensive specialists to less expensive generalists, and ultimately to nurses and the patients themselves.26 Hence, as has already happened with many infectious diseases, precision medicine, when embedded within the sorts of business model innovations described in Chapter 1, will ultimately cause more costs in our health-care system to decline as well.

We emphasize that this progress, in American football terms, is being ground out in a cloud of dust, yard by yard, play by play, and that negative yardage is common. As we are learning in our efforts to help patients with AIDS, precision diagnostics enable, but do not guarantee, the development of predictably effective therapies. Sometimes in our efforts to eradicate a disease, touchdown plays are called back as the bacteria, protozoan parasites, or viruses that cause a disease evolve to become resistant to previously effective treatments. Such is the case with malaria, which stubbornly resists precise interventions.

How soon will precision medicine affect the cost, quality, and accessibility of health care? The reality is that it is already here—the patterns of rules-based work and innovation described earlier have already profoundly shaped the diagnosis and treatment of diseases like diabetes mellitus—where the contrast between Type I and Type II diabetes care illustrates the impact rules-based work can have on the care for two seemingly similar diseases.27, 28

The early days of diabetic care involved significant uncertainty. The exact etiology of diabetes was unknown, and until the late 1800s, it was thought to be a kidney disease rather than a pancreatic hormone (insulin) deficiency. For centuries, diabetics could be diagnosed only by tasting a urine sample to assess its sweetness. Treatment was intuitive. Some physicians would experiment with dietary restrictions; others focused on personal hygiene. Others offered opium as a treatment. This trial-and-error problem solving led to extremely variable degrees of success in treatment and an inability to improve the overall standard of care. Worse yet, it fostered a high number of "quack" remedies which preyed on the hopes of desperate patients who had fallen victim to poorly understood diseases such as diabetes.29

Fortunately, as physicians came to understand more about diabetes and its treatment, their decision-making process began to change. One of the most important medical breakthroughs in history took place in 1922, when Canadian physician Sir Frederick Grant Banting and medical student Charles Best successfully treated a 14-year-old boy with insulin-containing pancreatic material extracted from dogs.30 Their work defined the patho-physiology of diabetes and linked it to a universal treatment. While physicians could once reasonably argue in favor of one therapy over another, even a layperson would soon be able to identify insulin as the only acceptable treatment for diabetes.

However, researchers soon began to understand that diabetes was a more complex disease than they had initially believed. The insulin seemed to restore vitality to once-cachectic children,31 yet there were other diabetics who seemed far less responsive to insulin. While they also had the same elevated blood glucose and physical symptoms, these patients were typically diagnosed with diabetes in adulthood and were often overweight. Physicians ultimately decided that there were two types of diabetes—childhood-onset and adult-onset, insulin dependent and non-insulin dependent; Type I and Type II.32

Despite ongoing research, there remains today a stark contrast in the level of understanding, and hence treatment, of these two diabetic populations. It is now known that a Type I diabetic has high glucose levels because the pancreas has lost the ability to produce insulin due to an autoimmune reaction. Although not strictly curative, insulin provides a method of treatment that can be entirely rules-based because it directly addresses the root cause of the disease.33

A critical reason why this diagnostic and therapeutic progress is important is that it makes it possible to deliver care through a different business model. Patients with diabetes can measure their own glucose levels at home with an electronic meter. Based on this reading, they can self-administer specific quantities of insulin which can be determined and prescribed by algorithm. Before long, the patients become expert in managing their own glucose levels (more so than the physician) and can recite a list of rules that govern their regimen. It is the Type I diabetic, not the physician, who knows exactly how much insulin she needs after consuming a bowl of cereal. In other words, responsibility for the care of the Type I diabetic has shifted from the physician to the patient.

In contrast, many challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of Type II diabetics remain in the realm of intuitive medicine, in the hands of professionals who use their medical expertise to solve complex problems. Some Type II diabetics are obese, while others are not. Some are diagnosed in adulthood, but an increasing number are now identified in childhood. Some require insulin, while others can be treated with oral medications or diet alone. In other words, the term "Type II" likely refers to a mélange of as many as 20 different disorders that may prove one day to have different molecular root causes and therefore require different treatments.34 Because the scientific understanding necessary to distinguish among these variants does not yet exist, precision treatment is impossible. For now, scientists will continue to refer to the disease as "multifactorial," and people who have this form of diabetes will need to rely on the intervention of experts to guide treatment.

When a mysterious illness began to appear in Ward 8635 of San Francisco's General Hospital in the early 1980s, the hospital's best experts were put to the test. In 1981, the disease was called GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) because scientists could base their diagnoses only on observable symptoms and demographic data. Without a clear root cause for the disease, physicians had to categorize at-risk individuals by these attributes. The common rule of thumb was to screen patients for the "four Hs": heroin user, hemophiliac, homosexual, and Haitian. These early victims of AIDS were extremely sick, and, despite the best efforts of dedicated physicians, most of them died.36

It is critical not to advocate rules-based treatment when the science relating to a disease is still intuitive. Yet in the past 25 years, just a blip in the overall history of infectious diseases, the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of AIDS have evolved dramatically. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was discovered as the root cause; molecular targets for pharmaceutical intervention were identified, and successful treatment protocols were developed. Though a cure or vaccine had yet to be discovered, the care surrounding HIV quickly became codified such that more and more generalists could manage the disease. Patients with HIV were living longer, and much of their treatment was shifted from intensive care and inpatient wards to outpatient clinics.

While HIV care has not yet reached the point where medicine can claim victory, the relatively quick progression toward greater precision care is also a likely indicator that past experience from dealing with other infectious diseases has shortened the period of intuitive medicine and experimentation necessary before rules-based care can develop. The world's quick mobilization in response to SARS (sudden acute respiratory syndrome) is another example of this increasingly rapid cycle time.

Another term, "personalized medicine," is often used for this phenomenon that we're calling "precision medicine." The reason we decided to coin a new term is that most precisely diagnosed diseases are in fact not uniquely personal. The same causal mechanism that predictably yields to the same therapy can be at work in many different people. As we soon discuss, the precise biological definition of a disease also does not incorporate "personalization" that takes into account how an individual patient might respond to a particular treatment.37 However, unlike precision medicine, personalization refers to both biological and nonbiological issues that can affect an individual's response to a treatment.38

For example, in the case of Type I diabetes that we just reviewed, the diagnosis of the disease is in precision medicine. There is no ambiguity: if the islet cells of your pancreas are unable to produce sufficient insulin, you have Type I diabetes.39 But the therapy still must be personalized for each patient. Patients in excellent physical condition typically need less insulin per calorie of carbohydrate ingested because their tissues are more sensitive to the presence of insulin, compared to patients who don't regularly exercise.

Personalization to some degree has always been a part of care delivery, of course, even though it may not feel like we always get the personal attention we desire. Physicians will avoid prescribing medications that could trigger a drug allergy, for example, or modify dosing based on the patient's age, weight, or kidney or liver function. However, just as diagnosis has progressed beyond observable symptoms, the assessment of an individual's specific response to treatment has begun to move to more sophisticated levels. This personalization of therapy can involve tailoring treatment either on the molecular level, or, as we will explain, based on socioeconomic and other nonbiologic factors that extend far beyond a clinician's normal realm of expertise—and therefore require new business models to deliver that care.

One of the most well-studied examples of tailoring therapy to the molecular mechanisms that affect response to therapy involves a drug called warfarin, a blood-thinner used by approximately 2 million new patients every year in the United States to prevent blood clotting, stroke, and heart attacks.40 However, the optimal dose of warfarin differs from patient to patient, and improper levels can cause serious problems—doses that are too high can cause deadly bleeding, while doses that are too low can lead to blood clotting diseases that the warfarin was meant to prevent. Studies have found that testing for variations in two genes (CYP2C9 and VKORC1) can help determine whether an individual will metabolize warfarin differently from others, and testing patients for these genetic variants prior to starting warfarin therapy would allow physicians to adjust their doses appropriately.41 A report from the American Enterprise Institute-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies estimated that integrating genetic testing into warfarin therapy would save $1.1 billion annually in the United States and prevent 85,000 cases of serious bleeding and 17,000 strokes each year.42 However, these specific improvements in care will come not from improving diagnosis, since the set of diseases being treated with warfarin remains the same, but rather from a greater understanding of how patients respond to some of our most commonly applied treatments.43

For most services in other industries, people think of personalization as an attempt by the company or its employees to acknowledge and respond to a customer's specific situation and circumstances. If a grocery store clerk offers to carry an elderly woman's shopping bags to her car, we would say that he has offered personalized service that was tailored to her needs. In the same sense, sometimes there is an entirely different, "non-medical" set of characteristics that can affect the course of a patient's treatment. Complex human behaviors such as compliance, motivation, and learning also influence outcomes. These in turn can be traced back to factors including family imprinting, the presence or absence of a social support system, financial resources, or previous experiences with the health-care system. In other words, there are a lot of things that can affect the outcome of a treatment, and many of them cannot be resolved through precision medicine. These are also the issues that very often frustrate health-care workers because they are so difficult to understand and control. Patients rightfully become frustrated as well when they discover that their sophisticated and expensive health-care system can't seem to understand the problem.

In health care the degree of personalization typically has stopped at the biologic level, despite the fact that so many non-physiological factors can affect outcomes and patient satisfaction. Social workers and other allied health professionals help to bridge this gap, but those systems are overwhelmed and can only help the outliers. Personalization is certainly not yet a matter of routine in health-care delivery. New business models are needed—particularly facilitated networks of professionals and patients enabled by information technology, as we discuss in Chapter 5.

Under the traditional health-care delivery model, there are only a few ways that a doctor and patient can fine-tune the treatment plan. Most often the plan is slowly adjusted over a series of appointments through a process of trial and error. This is expected of treatments for conditions that are only within or just beginning to move away from intuitive medicine, such as congestive heart failure and diabetes. However, even for more rules-based conditions like middle-ear and upper-respiratory-tract infections, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure, treatment plans often need to be adjusted for circumstances that go beyond the capabilities of precision medicine. The patient might only be able to afford generic drugs, or her busy schedule might prevent her from appearing at all of her physical therapy appointments, or she may have an intense distrust of hospitals because of a family member's past experience.

Doctors are accustomed to focusing on easily measurable markers such as vital signs and laboratory values, and the increasing significance of precision medicine means that ever more emphasis is being placed on such objective, straightforward criteria. And even though some doctors do try to account for some of the psychosocial factors that can influence outcomes, recognition often comes too late in the treatment process. Success is too heavily dependent on whether the physician is even aware of the impact of these "secondary" issues and how to counteract them. This is perhaps one of the main reasons why so many patients have taken such a great interest in participating in their own health care—not to challenge the physician's decision-making authority, but to complement it.

Professional and patient-centric network business models must play a greater role in the care of chronic diseases. Support groups in which patients can discuss the different circumstances that affect their treatment have long been a fertile ground for identifying effective solutions outside of the physician's office, often without expert guidance. Interestingly, this model has proven especially successful for addiction and psychiatric therapy—conditions which are perhaps more entrenched in intuitive medicine than any others. A key to the success of these networks is their ability to help patients find "someone like me," with whom they can identify and whose successful approach to the disease can serve as a role model for them to follow. Historically this option has only been viable when there has been a critical mass of patients locally with shared characteristics. However, the Internet is now bringing this level of personalized medicine to the rest of health care by extending the reach for "someone like me" across the globe.

Traditional media such as written publications, radio, and television are much like a typical visit to a doctor's office—the information tends to flow only in one direction. Early health-care Web sites were similar, acting primarily as information depositories meant for passive absorption by their users. However, social networking Web sites and newer "Web 2.0" services have taken the Internet far beyond its initial incarnation for most users as a one-way reference tool. In health services, this networking capability and collective intelligence are beginning to create the personalized health-care experience so many patients seek.

As mentioned earlier, online network facilitators are using their vast data processing capabilities to help users find "someone like me." Using self-reported personal health records and anonymous data from insurance billing claims, they can even provide metrics through which a patient can compare herself to her peers. Combining these data with predictive modeling tools, they can calculate the probability of disease and suggest the most beneficial ways of mitigating that risk with a more comprehensive view than any doctor could offer. It's not a far stretch to begin incorporating into these models less traditional health factors. As their databases become more sophisticated, the accuracy of matches and predictions will continue to improve.

Before the advent of such tools, a patient had to rely on a physician's expert opinion, which was built out of a largely random collection of book knowledge, clinical experience, heuristics, rules of thumb, and dumb luck.44 Whether a physician could prescribe the right treatment the first time often depended on whether he happened to have experienced a similar case in the past. But the odds of finding that similar case are now dramatically improved with tools that help patients identify each other through their common circumstances. Instead of waiting for the circumstances to declare themselves and become potentially life-threatening, patients and doctors can hopefully use these new resources to carry out the promise of truly personalized, precision medicine.

There are three prominent implications of the fact that scientific progress in imaging, molecular medicine, and biochemistry has long been shifting diseases along the spectrum from intuitive toward precision medicine. First, research that enables precision diagnosis should take highest priority for funding by entities such as the National Institutes of Health. This includes basic science research which naturally leads to future technologies that enable precision care, such as the investment made in the Human Genome Project, which led to the spinoff of many critically important developments in medicine. We also show, in Chapter 8, that whereas diagnostics historically has been a far less profitable business for the pharmaceutical industry than the therapeutics business, in the future that tendency will reverse. The reason is that in the past the industry's profit structure has been largely determined by autocratic reimbursement policies that do not reflect the value created by products and services. On average, reimbursement formulas accord greater profit to therapeutics than to diagnostics. Indeed, when health care was largely in the realm of intuitive medicine, diagnosis and treatment were interwoven. It was impossible to parse reimbursement between the two. But when solution shops are separated from value-adding process activities, as we describe in Chapter 3, it will be possible. And our theories of innovation suggest that diagnosis will become one of the most profitable parts of the value chain for pharmaceutical companies.45 This implies that pharmaceutical companies and academic researchers who focus their research and development energies will find that creating the precise diagnostics that fuel the growth of precision medicine will be most profitable in the future.

The second implication is that regulatory bodies such as the FDA in the United States need to change their posture about the role of clinical trials in research toward precision medicine. In the past, clinical trials were lined up in a serial mode, after research and development had been completed. If too small a percentage of patients responded to the drug, it was not approved—the result of trials has typically been a go-for-all/no-go-for-all decision. Instead, as we show in Chapter 8, trials need to be included as an integral part of the R&D process. If a trial shows that only 16 percent of patients responded to the therapy, in all probability the other 84 percent had a different disease from those who were helped. Such results from a trial ought to be celebrated as an opportunity to search for the biomarkers that would enable precise diagnosis.46

The third implication is that health-care executives need to aggressively couple the development of business model innovations with the progress that diseases are making along the spectrum from intuitive to empirical to precision medicine. We outline this mandate more completely in Chapters 3, 4, and 5.

To illustrate the latent potential that already exists for business model innovation, we've arrayed along two dimensions in Figure 2.4 a sampling of diseases. The current state of "diagnosability" of these diseases is mapped along the horizontal axis. At the left-most extreme are disorders that can be diagnosed only through the iterative testing of intuitive hypotheses. Diseases toward the right are those whose molecular etiology is relatively well understood and verifiable. The vertical axis of this chart plots the current efficacy of therapy. Diseases positioned at the bottom of the chart can be treated only experimentally: what works on one patient might not work on another; and sometimes there are no known effective therapies. Treatment for diseases in the middle is currently palliative (meaning that symptoms can reliably be alleviated); and treatment is curative for diseases we've plotted toward the top. The location of various diseases in the matrix is intended simply to be illustrative, rather than exact. It is the consensus of a set of professionals whose opinions we have sought. Figure 2.4 offers only a snapshot in time of this sampling of diseases. The chart is in fact quite dynamic, with diseases constantly migrating to new positions over time, as noted earlier.

Those diseases for which care is essentially rules-based—ranging from strep throat to Gaucher's disease—are clustered in the upper-right region. Much of the diagnosis and treatment of these diseases is rules-based and no longer requires significant expertise. Diseases still requiring complex problem solving remain in the lower-left corner where the intuition of skilled specialists is essential. These include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or more commonly known as Lou Gehrig's disease) and psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder. The etiology of some diseases—like infection by the Ebola virus—is understood and diagnosable, but currently cannot be treated with predictable efficacy. These are in the lower-right portion of the chart. And there are some diseases, in the upper left, where a dependable therapy works, and yet we're not quite sure why. By categorizing diseases in this manner, we hope to illustrate which diseases can be transferred to new business models of health-care delivery and which ones deserve more research dollars to push them toward precision care.

FIGURE 2.4 Current map of common medical conditions

Note that the diseases tend to lie along the diagonal from the lower left to the upper right—suggesting that the ability to diagnose precisely generally, though not always, enables the development of a predictably effective therapy.

As a general rule, imaging technologies give us a much more accurate characterization of how anatomy and symptoms are linked; but molecular medicine often will be the technology through which causality can be understood. Tumors and things like aortic aneurysms, for example, are symptoms of a deeper, causal mechanism. These disorders can be identified and characterized by imaging. But their cause is not yet well understood. This is why we state at the beginning of this chapter that the technological enabler for disruption in health care is the ability to diagnose precisely, which then opens the door for development of a predictably effective therapy. The three specific streams of technology that can enable this revolution are molecular medicine, imaging technologies, and ubiquitous connectivity.

If regulators, policy makers, and executives do not seek business model innovation for diseases that move toward the upper-right region in this chart, the potential returns, in terms of reduced cost and improved accessibility, for society's massive investments in science and technology, will be small. As each disease moves along the spectrum from intuitive to precision medicine, fewer people with highly specialized expertise are needed to solve the challenges that the particular disease presents. Individuals with less specific training become capable of delivering care which was once restricted to the experts. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants can do the work once performed by physicians. As was the case in organic fibers and computers, reduced cost and improved accessibility of quality health care will not come from replicating the expertise and costs of today's best physicians. These can only come, very frankly, from scientific progress that "commoditizes" their expertise, making it accessible at low cost to many more patients. Specialists working in the finest medical centers will always be needed to treat those diseases remaining in the realm of intuitive medicine, of course—and surely, new, poorly understood diseases will continue to emerge. But it makes no sense for regulation, reimbursement, habit, or culture to imprison care in the realm of intuition when it has moved a significant distance along the spectrum.

There are countless examples of such shifts in the locus of care. Angioplasty has enabled cardiologists to treat many patients who would otherwise have been under the care of a cardiothoracic surgeon or who were ineligible for surgery altogether. Effective HIV medications, genotyping, and routine viral load surveillance have enabled primary care physicians to manage as outpatients those who were once complex inpatient cases treated by infectious disease specialists.47 Physician assistants, rather than primary care physicians, can adjust blood pressure medications or perform a diabetic patient's routine examinations with less waiting time in the clinic. Nurses can perform tests for strep throat and prescribe pharmaceutical treatment at low-cost, conveniently located retail kiosks. Consumers can buy a pregnancy test kit from the drugstore and perform at home tests that previously had to be professionally administered in a hospital lab.

A map from the previous century would look quite different from the one we present in Figure 2.4. Diseases like the plague, smallpox, and polio are just three of many ailments, so feared long ago, which have become historical footnotes because of the success of the microbe hunters of modern medicine. These diseases represent only a microscopic share of the health-care system's expenditures today, and they are hard to find on charts categorizing diseases of modern time. There is every reason to believe that imaging and molecular diagnostics, as technological enablers of future disruptive innovations in health care, can have similar impact.

1. This touches on principles first outlined in The Innovator's Solution about the conservation of attractive profits and skating to where the money will be. As technologies commoditize expertise, those technologies themselves occupy the new value-delivering positions in the value network. As a result, profits would be expected to flow to those areas.

2. We thank our colleague Dr. Richard Bohmer for first articulating this three-staged pattern for us. It was originally published in Christensen, Clayton M., et al., "Will Disruptive Innovations Cure Health Care?" Harvard Business Review, vol. 78, no. 5, Sept.– Oct. 2000, 102–17.

3. With Kevlar, for example, DuPont was able to deliberately work toward the goal of developing a fiber with specific properties—in this case, one that was stiff yet heat resistant. The work was not entirely straightforward, however, still requiring tremendous intuition in determining which steps to take. The story of Kevlar's development can be found at Tanner, David, "The Kevlar Innovation," R&D Innovator, vol. 4, no. 11, Nov. 1995.

4. Thomke, Stefan, "The Crash in the Machine," Scientific American, March 1999.

5. Kahn, Steven E., et al., "Glycemic Durability of Rosiglitazone, Metformin, or Glyburide Monotherapy," New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 355, no. 23, Dec. 7, 2006, 2427–43. This study evaluated the long-term efficacy of oral monotherapy in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. After four years of treatment with escalating doses as deemed clinically appropriate, 40 percent of the 1,456 patients receiving rosiglitazone, 36 percent of the 1,454 patients receiving metformin, and 26 percent of the 1,441 patients receiving glyburide had a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7 percent.

6. Kearney, Patricia M., et al., "Worldwide Prevalence of Hypertension: A Systematic Review," Journal of Hypertension, vol. 22, no. 1, Jan. 2004, p.11–19. This study examined the worldwide awareness, prevalence, and treatment of hypertension. Control of hyper-tension (defined as <140/90 while on medication) was found to vary from 5.4 percent in Korea to 58 percent in Barbados.

7. Fletcher, Barbara, et al., "Managing Abnormal Blood Lipids: A Collaborative Approach," Circulation, vol. 112, no. 20, 2005, 3184–3209. The authors proposed a new approach to managing cholesterol after previous studies (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES III] and Lipid Treatment Assessment Project [L-TAP]) demonstrated only 16.6 to 18 percent of patients with heart disease were able to reach treatment targets established by the NCEP ATP III (National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III). In turn, the same studies found that 30.2 to 37 percent of high-risk patients and 68 to 72.8 percent of low-risk patients were able to reach their targets.

8. See Thase, Michael E. and John A. Rush, "Treatment-Resistant Depression," in Bloom, Floyd E. and David J. Kupfer, eds., Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress (New York: Raven Press, 1995); and Williams, John W. Jr., et al., "A Systematic Review of Newer Pharmacotherapies for Depression in Adults: Evidence Report Summary: Clinical Guideline, Part 2," Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 132, no. 9, 2000, 743–56. This study evaluated SSRIs and newer antidepressants: 51 to 54 percent of patients experienced a 50 percent improvement in symptoms; 10 percent of patients in active treatment relapsed within 24 weeks; 32 percent who received placebo experienced at least a 50 percent improvement in symptoms.

9. The differences in diseases and outcomes are also affected by nonbiological characteristics. We discuss these additional factors later in this chapter, and discuss how to manage them in Chapter 5 within the context of caring for chronic diseases.

10. A range of studies has shown that there often are profound regional differences in clinical practice in these intuitive fields of medicine that defy standardization. For example, the number of spinal surgeries performed within a community can range from 0.6 to nearly 5.0 per 1,000 Medicare patients. The fact that one is over 10 times more likely to have spinal fusion surgery in Idaho Falls, Idaho, than in Bangor, Maine, suggests that in the practice of intuitive medicine the focus of a doctor's training and the mechanisms for making money are part of the intuition used to decide which therapy will be most efficacious for the patient. For more information see Weinstein, James N., et al., "United States' Trends and Regional Variations in Lumbar Spine Surgery: 1992–2003," Spine, vol. 31, no. 23, 2006, 2707–14.

11. Appleby, Julie, "Back Pain Is Behind a Debate," USA Today, October 17, 2006.

12. Another term, "personalized medicine," is often used for this phenomenon that we're calling "precision medicine." The reason we decided to coin a new term is that most precisely diagnosed diseases are in fact not uniquely personal. The same causal mechanism that predictably yields to the same therapy can be at work in many different people. As we shall soon discuss, the precise biological definition of a disease also does not incorporate "personalization," that is, how an individual patient might respond to a particular treatment. Thus we concluded that the term "precision medicine" more accurately connotes the nature and enabling potential of scientific and technological progress in health care, while "personalized medicine" should refer to the additional aspect of incorporating biological and nonphysiological issues that deal with an individual's response to precise care.

13. Another reason we use "empirical medicine" rather than "evidence-based medicine" is that the degree to which the evidence is convincing varies by disease and over time. The situations in which the probabilities of the desired outcome are so high that every caregiver should play those odds by following those "best practice" procedures are a subset within a broader territory between intuitive and precision medicine, where correlations are clear enough so outcomes can be expressed probabilistically. Of course, intuition still must be exercised in the realm of empirical medicine.

The practice of empirical medicine was spawned by researchers at Canada's McMaster University, led by David Sackett and Gordon Guyatt in the early 1990s. They proposed that there was sufficient medical knowledge and experience that we could begin to apply statistical analysis to both diagnosis and treatment of specific conditions. They reasoned that using double-blind prospective studies—the gold standard of methods—was neither feasible nor moral. Instead, they looked retrospectively and brought together large numbers of articles from the clinical literature, performed meta-analyses on them, and began to publish the best demonstrated algorithms from these analyses. Their earliest syntheses of these studies were primitive, but they improved over time. Soon, other researchers began to develop methods, such as registries and cohort observational studies, that were well-suited for prospective short-term projects. From there they have evolved into a more formal discipline, evidence-based medicine. Guyatt coined the term, "evidence-based medicine" in Guyatt, Gordon H., et al. "Evidence-Based Medicine. A New Approach to Teaching the Practice of Medicine," JAMA, 268 (1992):2420-25.

14. Although the dominant current flows from intuitive to empirical and finally to precision medicine, occasionally a disease can flow the other way. For example, the evolution of new bacteria that are resistant to certain antibiotics can cause a regression back to empirical and even intuitive medicine, as physicians cannot accurately predict that a given treatment will cure any particular patient.

15. While it is possible to achieve rules-driven care without precision diagnosis, such care is at best empirically driven and reliant upon mechanisms and explanations for disease that could be gravely misunderstood.

16. Of course, the estimates used here can vary, depending on incubation period, virulence, vector organism, mode of transmission, and so on. Nevertheless, the typical cost trend for infectious diseases crosses three phases. Initially, the cost of care tends to be low, while the etiology and pathophysiology are still unknown. Next, these patients can be stabilized, often at high cost through hospitalization, but the primary cause is still unknown or untreatable. Finally, once the cause becomes known and treatable, costs typically decline significantly; if a preventive measure like vaccination becomes available, costs plummet even faster. For example, polio vaccines have saved the U.S. health-care system $810 billion in the past 50 years and will have saved an estimated $1 trillion by 2015. See Shankar, Vivek, "U.S. Saved 135,000 Lives, $810 Billion Using Polio Vaccines." Polio Survivors and Associates, January 23, 2007, accessed from http://www.rotarypoliosurvivors.com/PDF/US%20Saved%20135%20000%20Lives%20%20$810%20Billion%20-%20Polio%20Vaccines.pdf on August 30, 2008. The cost savings have been even more dramatic for HIV/AIDS patients. From early 1991 to late 1992 the cost of treating AIDS patients from the time of diagnosis until death fell by 32 percent, from $102,000 to $69,000. The average number of hospital days fell from 52 days to 35 days. See Hellinger, Fred J., "The Lifetime Cost of Treating a Person with HIV," Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 270, July 1993, 474–78. Finally, between 1954 and 1997 antimicrobials reduced new cases of active tuberculosis by 32 percent, mortalities by 81 percent, lost life-years by 87 percent, and cost of medical treatment by 76 percent. Total financial burden of illness, including the value of lost life-years, decreased (in 1997 dollars) from $894 billion to $128 billion. This equates to an average yearly decline of 4.4 percent in the cost of treatment and overall burden of disease. See Javitz, Harold S. and Marcia M. Ward, "Value of Antimicrobials in the Prevention and Treatment of Tuberculosis in the United States," International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, vol. 6, no. 4. April 2002, 275-88.

17. Koch, Robert, "Die Aetiologie der Tuberculose," Berlin klin. Wochschr, vol. 19, 1882, 221.

18. On the other hand, we must also not be so hubristic to believe that our current categorization scheme is absolutely correct. After all, each method of the past was at some point supported with some type of evidence and believed to be correct by seemingly reasonable people. The best we can hope to do is constantly push both our diagnostic and therapeutic understanding forward. If we fail to do so, the consequences can be grave. There remains a continuing threat of new infections that extend beyond the boundaries of our scientific understanding and ability to treat. For example, Influenza A subtype H5N1, also known as Avian flu, is currently beyond our treatment capability, even though we are able to precisely diagnose the pathogenesis. Without effective prevention or treatment, the prevailing fear is that it may one day create a terrifying spike in mortality, mirroring the one caused by the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 (as shown in Figure 2.2). Even diseases like tuberculosis, once thought to be close to defeat, are capable of mounting a resurgence if our treatments fail to precisely match the resistance profiles we have identified.

19. Central to the transformation of infectious disease medicine was the predictable and routine identification of the agent or organism responsible for a disease, usually through culture in a laboratory, followed by an assessment of which medications were most likely to be effective against that organism. Evidence thus accumulated over time in a given location became the source of data that determined the initial, empiric treatment of a patient with pneumonia, for example. An "antibiogram" from a hospital lab, based on such data, gave physicians a snapshot of which organisms were likely to be present and which drugs were most likely to be effective. While empirical treatment was typically the first step, treatment would then progress to a more precise pathway as the individual patient's culture results and specific drug sensitivity information became available from the laboratory. It is this adoption of molecular methods into microbiology laboratories today that will continue to narrow the window between an empiric treatment and a precision one. Identifying the molecular signature of a microbe within each patient sample will allow physicians to determine sooner what treatment will be best for the patient, whether that treatment happens to be a customized immunologic molecule or a long-known chemical agent like penicillin.

20. More specifically, Gleevec targets a subtype of CML patients who possess a certain genetic mutation known as the "Philadelphia Chromosome." However, 95 percent of CML patients share this mutation, making the drug quite effective for the overall CML population. For more information, see "How Gleevec Works," at http://www.gleevec.com/info/ag/index.jsp "The Philadelphia Chromosome and CML" at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408451_5.

21. Even when the unique pattern of genetic expression for each of these tumors that occur in the breast has been characterized, and when predictably effective Herceptinlike therapies have been developed, we may not be home free. This is because the tumor itself can be a symptom of a deeper causal mechanism. Many scientists theorize that a large number of cancers and other diseases will eventually be attributable to infectious diseases. Nevertheless, until the cause(s) of the tumor is understood, prevention is difficult and recurrence can still occur in affected patients.

22. Even Herceptin will eventually be viewed as insufficient treatment, since it only attacks a nonspecific receptor and not a genetic target unique to a breast cancer cell. See Jeffrey, Stephen, "Cancer Therapy: Take Aim," Economist(2007).

23. Healy, Bernadine, "Cancer and Me," U.S. News and World Report," April 9, 2007, 60-68. This source was excerpted from her book, Living Time: Faith and Facts to Transform Your Cancer Journey (New York: Bantam, 2007).

24. Historically, we have diagnosed and categorized diseases based only on phenomena observable to the five senses. For example, the sweet taste of a patient's urine and the smell of ketones in his or her breath were reliable indicators of diabetes. Even the roentenogram (now more commonly known as the X-ray), which was so lauded as a new way for doctors to diagnose disease, was merely an extension of how our eyes could detect abnormalities.

25. A significant portion of this progress has been achieved through prevention—discouraging cancer-causing behaviors such as smoking and prolonged exposure to the sun, and removing known carcinogens from the environment—based on a deeper understanding of risk factors for disease. In addition, a measurable reduction in the mortality rate of select cancers can now be attributed to improved, targeted drugs.

26. Furthermore, vaccinations given by nurses are an even greater disruption in terms of creating value, since prevention of disease obviates any need for intuitive diagnosis and treatment downstream.

27. Schaffer, Amanda, "In Diabetes, a Complex of Causes," New York Times, October 16, 2007.

28. Manning, Anita, "Islets Could Be a Key to Diabetes Cure," USA Today, November 13, 2007.

29. "American Medical Association Publishes 'Nostrums and Quackery' Warning the Public Against Humbugs," New York Times, January 14, 1912, SM7.

30. Banting, Frederick G., et al., "The Internal Secretion of the Pancreas," American Journal of Physiology, vol. 59, no. 479, 1922. For his revolutionary discovery, Sir Frederick G. Banting (as well as his laboratory sponsor John Macleod) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1923.

31. Cachectic means inability to be nourished.

32. Again, the attempt the categorize disease based solely on observable symptoms leads to labels that are overlapping and confusing, as we shall soon see.

33. It can also be argued that the true "root cause" has yet to be identified, since the etiology of the autoimmune reaction is unclear. For example, if a virus is eventually found to be the inciting cause, then a vaccine or antiviral medication would be a more appropriate treatment.

34. This estimate was given in personal conversations between 2000 and 2002 with Dr. Keith Dionne, who at the time worked as a senior scientist at Millennium Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

35. Some background information comes from the historical records of San Francisco General Hospital (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/collres/archives/ahp/sfgh.html). Ward 86 was the area of the hospital where some of the nation's first AIDS patients congregated.

36. In 1981, 91 percent (247 of 270 of AIDS patients) died within six months of diagnosis. In 1982, 87 percent (886 of 1,014); in 1983, 87 percent (2,459 of 2,822); in 1984, 81 percent (4,611 of 5,695). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 1987 edition, 5. Accessed from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/pdf/surveillance87.pdf. It should be noted that death counts from HIV/AIDS varied slightly across the earliest annual reports, as diagnosis was still difficult to make, and many cases could be added only retrospectively.

37. In other words, a population of patients can be divided into categories based on precise disease pathways, but they can also be independently divided into categories based on how they will respond to precision therapies. It is actually an overlapping subset of patients (with as few as one member) between these two categorization schemes who will benefit the most from a particular personalized treatment plan.

38. We acknowledge the fact that many researchers appear to combine the concepts of precise definition of disease pathways and the precise response of patients to therapy. Both elements of diagnosis and treatment have been drilled down increasingly to their molecular and genetic levels over the last decade, so it is understandable why they are often thought of as combined notions under the general heading of personalized medicine. However, we believe it is important to keep these concepts separate, as technological enablers can independently come from either side to further the progression to new, disruptive models of care.

39. Even this categorization of Type I diabetes has multiple etiologies, including auto-immune disease, infection, trauma, or toxins. Thus far, increasing the precision of diagnosis beyond "insulin deficiency" does not appear to affect insulin treatment, but there is obviously still some capacity for ever-precise categorization.

40. "FDA Approves Updated Warfarin (Coumadin) Prescribing Information," FDA press release, August 16, 2007. Accessed from http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01684.html.

41. Schwarz, Ute I., et al., "Genetic Determinants of Response to Warfarin during Initial Anticoagulation," New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 358, no. 10, 999-1088.

42. McWilliam, Andrew, et al., "Health Care Savings from Personalizing Medicine Using Genetic Testing: The Case of Warfarin," American Enterprise Institute-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies, Working Paper 06-23, Nov. 2006. Accessed from: http://www.aei-brookings.org/publications/abstract.php?pid=1127.

43. Taking a lesson from our previous discussion about precision medicine, there would be potentially even greater gains to be made if we could identify exactly which patients are truly at risk for stroke, heart attack, or recurrent blood clotting.

44. We refer readers interested in the nuances of physician decision making to Groopman, Jerome, How Doctors Think (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2007).

45. The theory in question is called the "Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits" and is summarized in Chapter 6 of Christensen, Clayton, and Michael Raynor, The Innovator's Solution (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003). Michael Porter articulated his "five forces" framework in the early 1980s, showing how those forces tend to concentrate the ability to earn attractive profits at particular points in an industry's value chain, stripping them away from companies at other points in the chain. This is a valuable model, but it is static, in that it describes how things are at present. The Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits comprises the dynamic dimension of Porter's model, showing how and why those forces shift to different places in the value chain over time. In particular, it describes the mechanism by which activities become commoditized. When that happens, the places in the value chain where the products and services are not yet good enough for what the next customer in the chain needs shifts to the adjacent layer in the chain. Hence, commoditization in one layer initiates a reciprocal process of decommoditization in the adjacent layers. We strongly recommend that executives in the pharmaceutical and hospital industries use this theory to understand how to focus their future investments in those activities in the chain that will become decommoditized—because the future will be different from the past.

46. In a speech at Harvard Business School (HBS Health Industry Alumni Association Fourth Annual Health Care Conference, Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School, November 7–8, 2003), Mark B. McClellan, former director of the Food and Drug Administration and former director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, asserted that the FDA already has begun making progress in this direction.

47. It is interesting to note, however, how many HIV patients continue to be managed primarily by HIV specialists. This is an indication that the system has not encouraged the development of new models of care for HIV, instead relying on traditional models even when the care is no longer as complex. As we discuss in Chapter 7, the reimbursement system has much to do with encouraging this. Contrast the situation with the developing world, where in many instances a nurse prescribes the drugs and manages the care. There, a disruptive model of care arose because the alternative was no care at all.